ABSTRACT

National population growth has increased the domestic demand for horticulture commodities. Geographically, Indonesia has great potential in leading the fruit and vegetable production in Southeast Asia. However, many factors lead to the lack of domestic production, including lack of quality control, fluctuating market price, overproduction, old-school farming technology, and weak regulation. This study aims to present the development and characteristics of horticultural crop agriculture, especially fruit and vegetables. In particular, it includes the government policies and regulations implemented within the framework of national agricultural development. The main section is to describe sociologically the current status of fruit and vegetable production and marketing in Indonesia. It also examines the latest production status, consumption trends, and market patterns for fruits and vegetables. There will be a general assessment of the agricultural industrialization status for fruits and vegetables in the final section. Horticulture industrialization itself has a strong correlation with the market chain and production status.

Keywords: fruit, vegetable, industrialization, policy, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

As an agricultural country, Indonesia has various landscapes and fertile soils that produce various agricultural products, including horticulture, particularly fruits and vegetables commodities. There are 60 types of fruits and 82 types of vegetables which are developed by the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture as presented in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 (MoA, 2019a). Among those commodities, there are some strategic fruit and vegetable categories, as presented in Figure 1.

The term of strategic fruits and vegetables is based on contribution substance. The contribution of these commodities can be categorized as greater than those of other commodities within the horticulture sub-sector in Indonesia. It is particularly related to the characteristics of the planted area, production, consumption, market, and other typical categories.

Objectives

Generally, this article discusses the agricultural industrialization[1]. The case of fruits and vegetables focuses on strategic commodities in Indonesia. Specifically, the objectives of this article are: (1) To describe Indonesia’s strategic fruits and vegetables status; (2) To deliberate the strategic fruit and vegetable industrialization in Indonesia; and (3) To identify and brief policy support to strategic fruit and vegetable production and market in Indonesia.

INDONESIAN FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

Planted area

In Indonesia, the unit of the production area of strategic fruit commodities differs from those of vegetable commodities. Fruit commodities are based on the harvested plant (tree or clump unit) since those are planted in scattered areas within irregular planting space and intercropping with other crops. Meanwhile, the production of vegetable commodities with a common monoculture system is in the form of harvested area (hectare unit).

Planted area of strategic fruit commodity

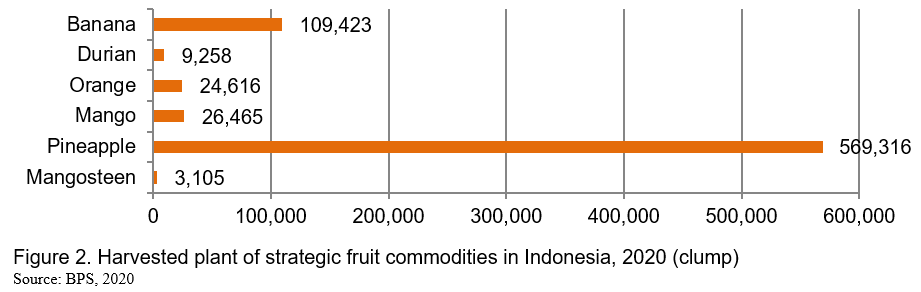

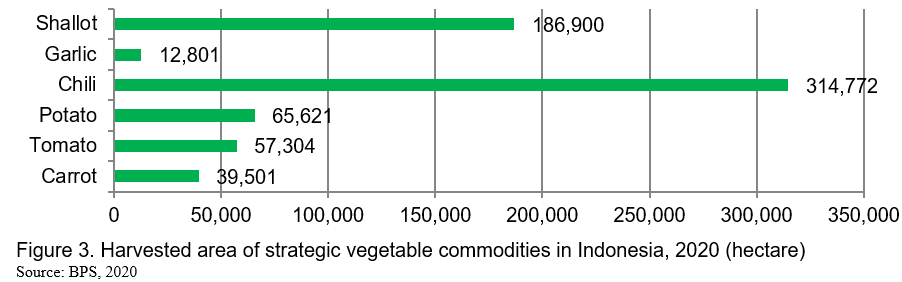

The harvested plant of strategic fruit commodities can be seen in Figure 2. Pineapple was recorded as the largest harvested plant among other strategic fruit commodities. It was followed by banana commodity. The smallest harvested plant was mangosteen.

During the last five years (2016-2020), besides pineapple, the harvested plant of bananas was quite large. It was noted that the harvested plant of durian increased significantly since 2018, namely about 30% (Table 1).

Planted area of strategic vegetable commodity

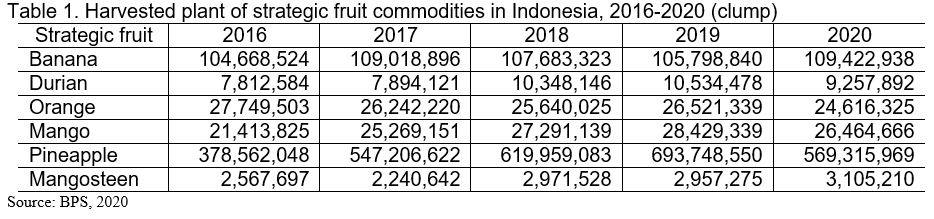

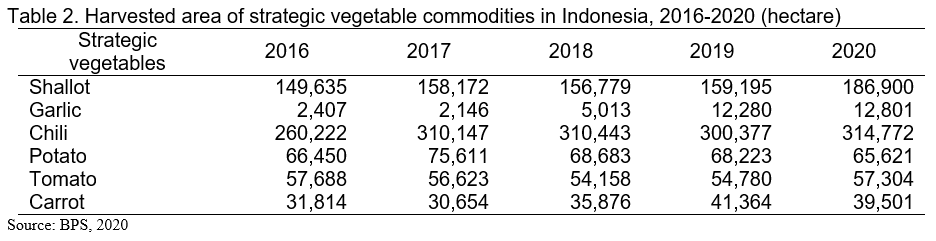

The largest harvested area of strategic vegetable commodities was chilli, followed by shallot. Meanwhile, the smallest harvested area was garlic (Figure 3).

Chilli still dominated among the harvested area of vegetable commodities from 2016 to 2020 (Table 2). The harvested area of garlic has significantly increased since 2018.

Production

Production of strategic fruit commodities

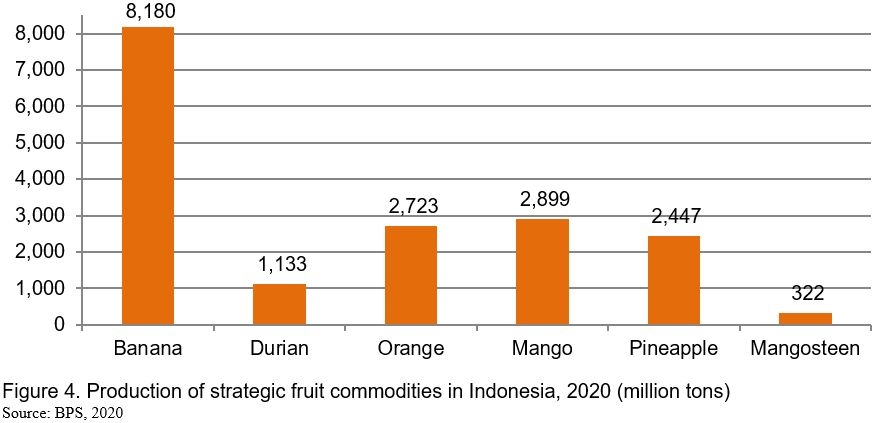

The production of strategic fruit commodities is shown in Figure 4. It reveals that the banana was the most productive commodity as compared to other strategic commodities. The lowest one was mangosteen.

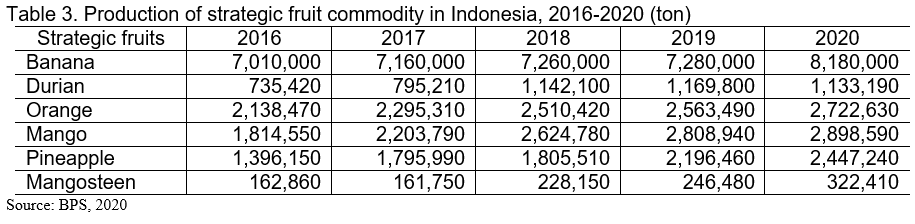

In the last five-years (2016-2020), banana was the highest productive strategic fruit commodity. In addition, the production of mangosteen increased substantially by about 20% per annum (Table 3).

Production of strategic vegetable commodities

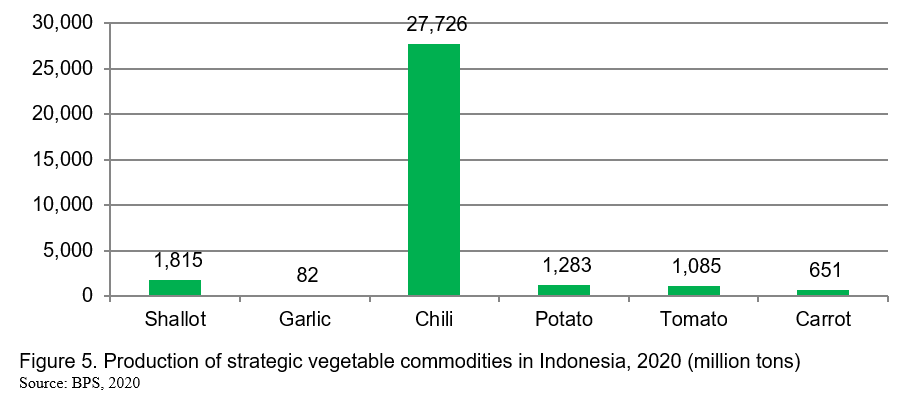

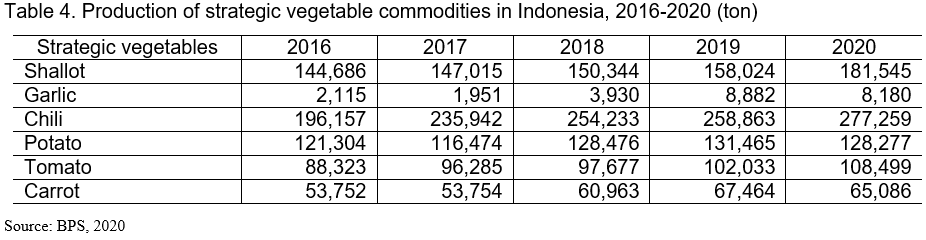

The production of strategic vegetable commodities was dominated by chilli (Figure 5). This commodity was superior compared with other strategic commodities. It was noted that garlic was quite minor in terms of production.

Among strategic vegetable commodities, garlic production was quite promising from 2016 to 2020 (Table 4). The production of this commodity started to increase in 2018.

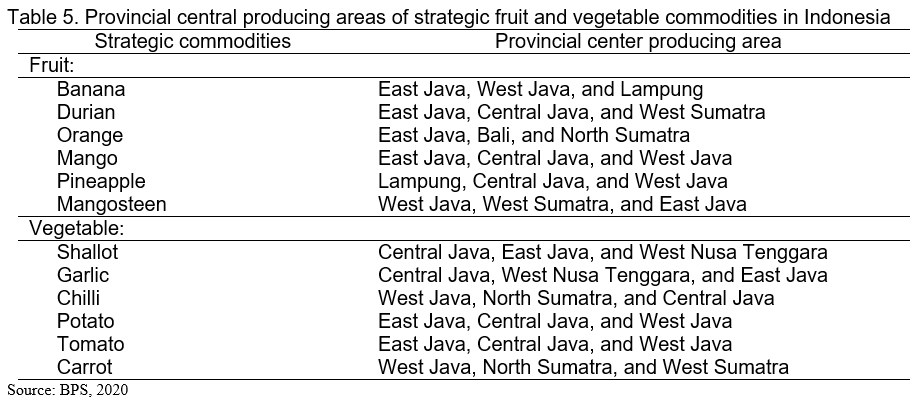

Central producing area

The central producing areas of strategic fruit and vegetable commodities in Indonesia can be seen in Table 5. Most of the commodities are planted in Java Island, particularly in East Java, Central Java, and West Java.

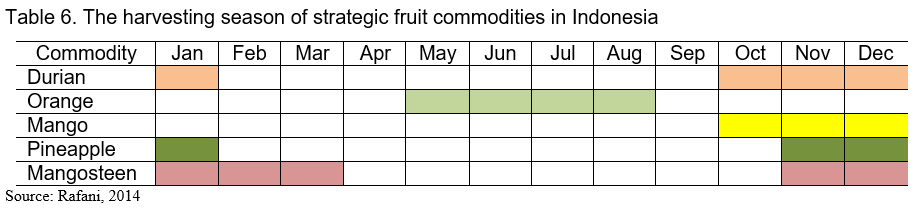

Unlike vegetable crops which can be harvested at any time along the year, they can particularly harvest certain fruit crops for a certain season. Specifically, they include durian, orange, mango, pineapple, and mangosteen (Table 6).

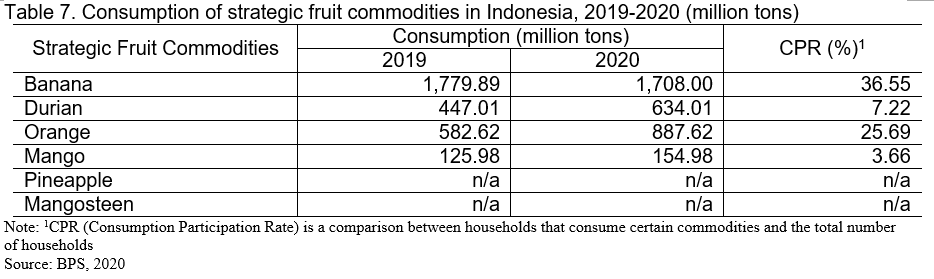

Consumption

The extent of consumption of strategic fruit commodities in Indonesia can be seen in Table 7. It reveals that banana was the most consumed by Indonesians, followed by orange with a participation rate (CPR) of about 35.65% and 25.69%, respectively. The consumption growth of bananas tended to be a slight bit decrease. Meanwhile, the growth of orange, durian, and mango was increased positively, greater than 20%, from 2019 to 2020.

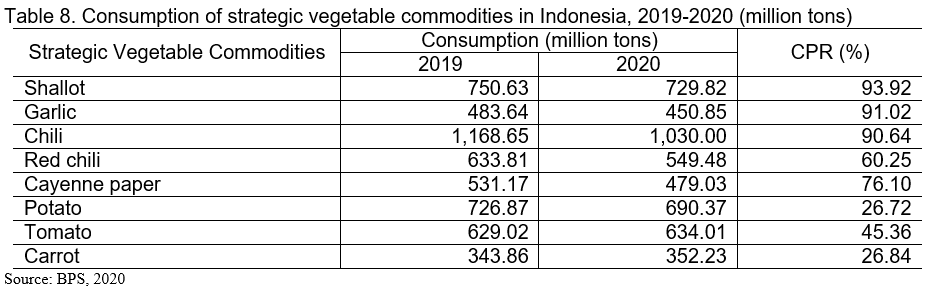

The CPR of strategic vegetable commodities was much higher than strategic fruit commodities, particularly shallot, garlic, and chilli (Table 8). These strategic vegetable commodities were used as the main ingredient in cooking food in Indonesia all the time.

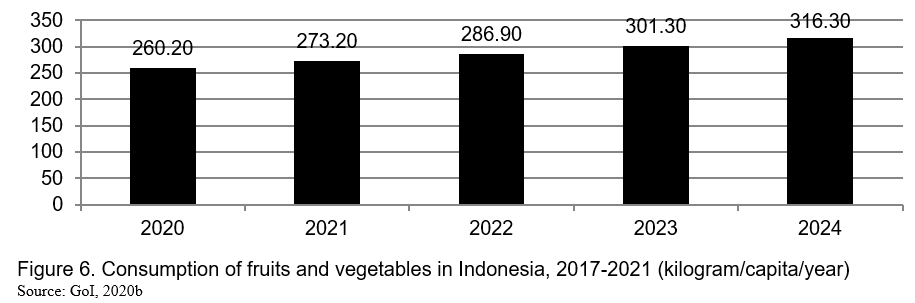

Indonesia has a target to increase fruits and vegetables consumption from 260.2 kilograms per capita in 2020 to 316.3 kilograms per capita in 2024. In other words, the extent of fruits and vegetables consumption for the country population is targeted to be increased by about 5% annually (Figure 6).

Market

There are two general forms of the market characteristic of strategic fruits and vegetables commodities in Indonesia. First, farmers traditionally conduct it through certain places such as wet markets, stalls, and street traders. Second, it is carried out in modern systems by commercial entities (national and multinational companies) through the mini markets, supermarkets, retailers, and exports.

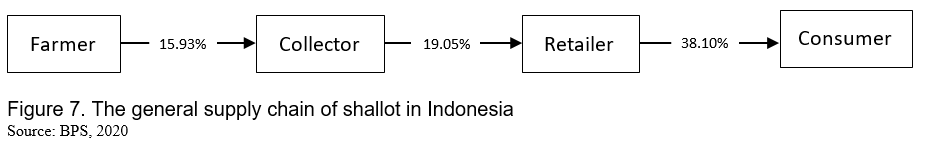

As an illustration, the following discusses the case of the shallot and chilli marketing system in Indonesia. These commodities are essential, which are the main ingredient of Indonesia’s cookeries and quite sensitive in terms of their distribution. As characterized as perishable commodities, shallot and chilli must be distributed promptly. Due to transportation problems and the harmful intervention of certain irresponsible traders, these commodities are sometimes volatile with price fluctuation. The next consequence is that it can lead to economic inflation in the country.

Figure 7 presents the trade distribution pattern of shallot involving farmer as producer – collector – trader – the consumer. Trade and Transportation Margin (TTM)[2] of shallot in 2019 reached 38.01% as a cumulative value chain. The respective TTM of retailer and collector was 19.05% and 15.93%. It was found that the province with the highest TTM was Papua Barat (134.78%), while the lowest one was Jambi (16.34%).

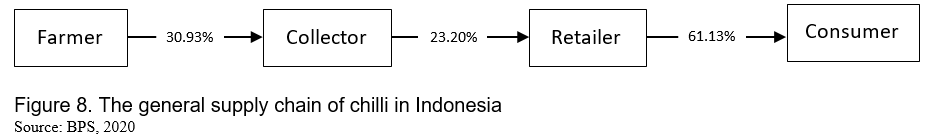

In the same period, the TTM of chilli was much higher than that of shallot (Figure 8), the cumulative value is 61.13% comprising the TTM of retailer (23.20%) and collector (30.93%). The province with the highest TTM was Kalimantan Tengah (98.69%), while the lowest was Bali (11.01%).

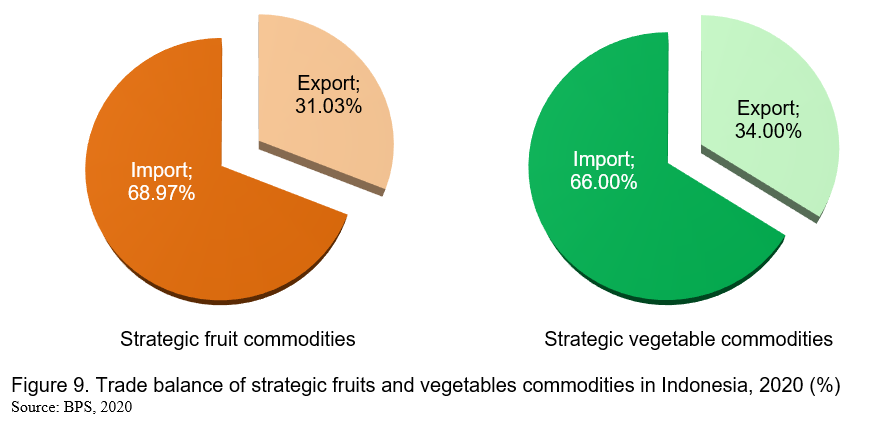

Export and import

Apart from domestic production, Indonesia still quite depends on imported fruits and vegetables commodities. In other words, the country has a trade imbalance in terms of export and import of these commodities. Indonesia imports strategic fruit and vegetable commodities of about 69% and 66%, respectively (Figure 9).

Strategic fruits commodity export

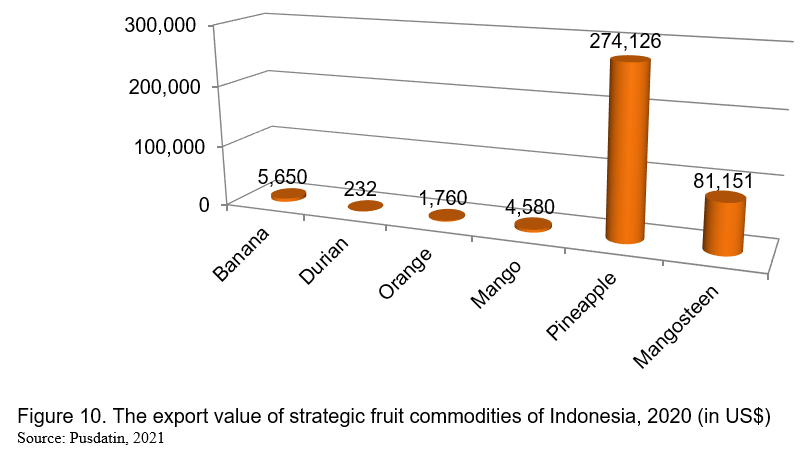

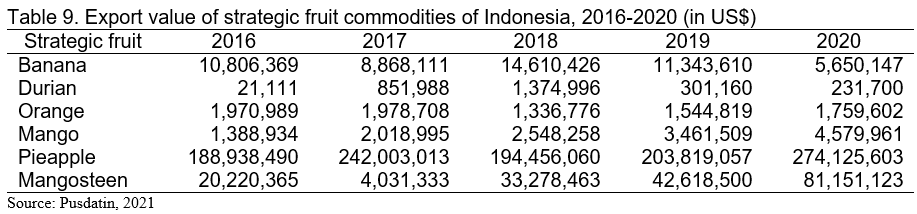

The highest export value of strategic fruit commodities was pineapple, followed by mangosteen. The extent of export value of these commodities was much greater than those of other strategic fruit commodities, namely banana, mango, orange, and durian (Figure 10).

During the last five years (2016-2020), the export values of durian, banana, mangosteen, orange, and mango were quite insignificant compared with pineapple. Meanwhile, the export values of bananas and orange tended to decrease during the periods (Table 9).

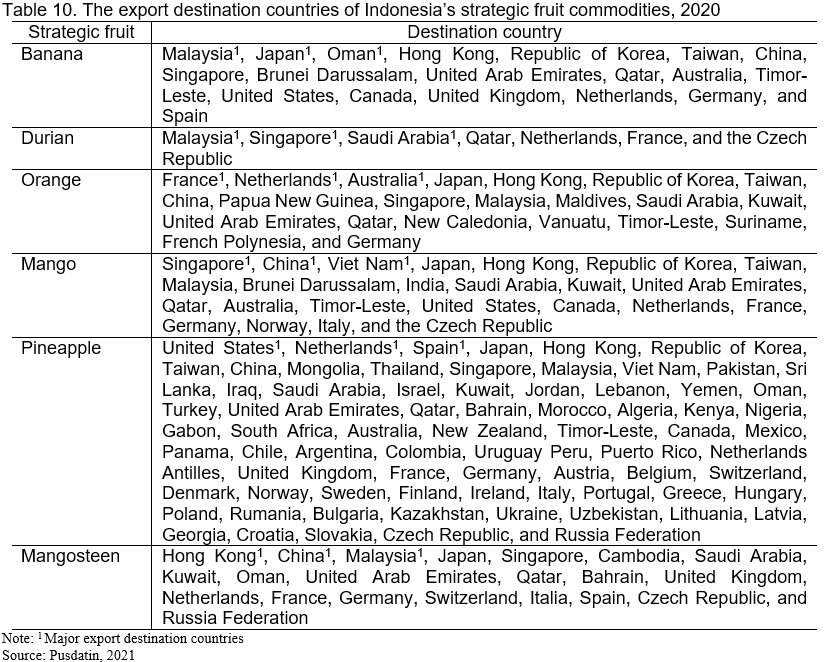

The export destination countries of Indonesia’s strategic fruit commodities are presented in Table 10. It comprises the major followed by the rest export destination countries.

Strategic vegetables commodity export

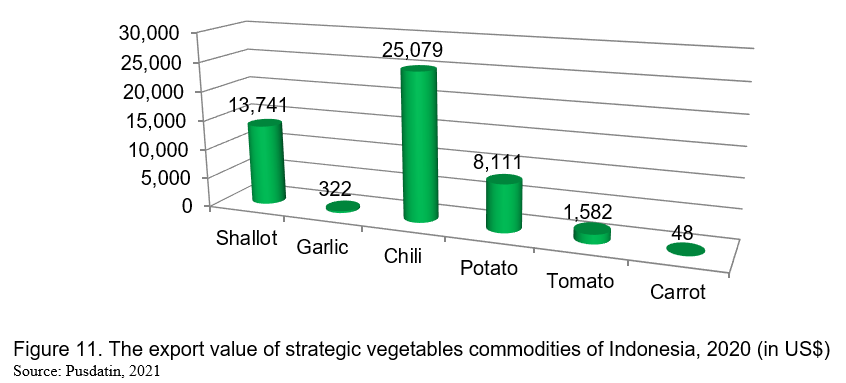

Chilli and shallot were the dominant export value of strategic vegetable commodities compared to potato, tomato, garlic, and carrot. Figure 11 shows that the extent of chilli and shallot export values was almost five times higher than the export values of potato, tomato, garlic, and carrot.

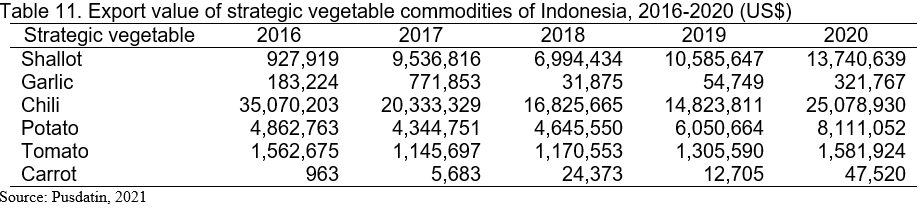

From 2016 to 2020, the extent of value export of shallot, chilli, potato, and carrot was considerably great. This was particularly because of the highest export value of these commodities in 2020 (Table 11).

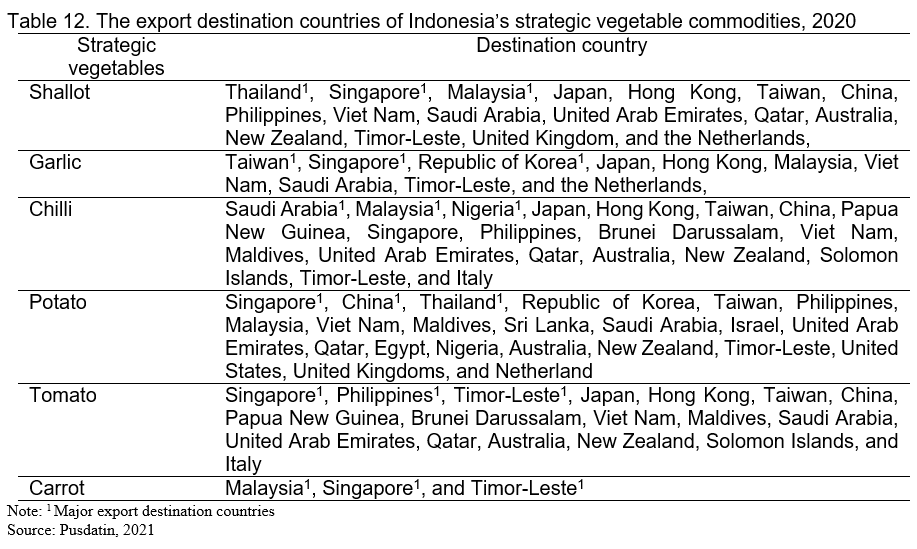

The export destination of Indonesia’s strategic vegetable commodities was Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines. It also includes certain countries in other regions (Table 12).

Strategic fruits commodity import

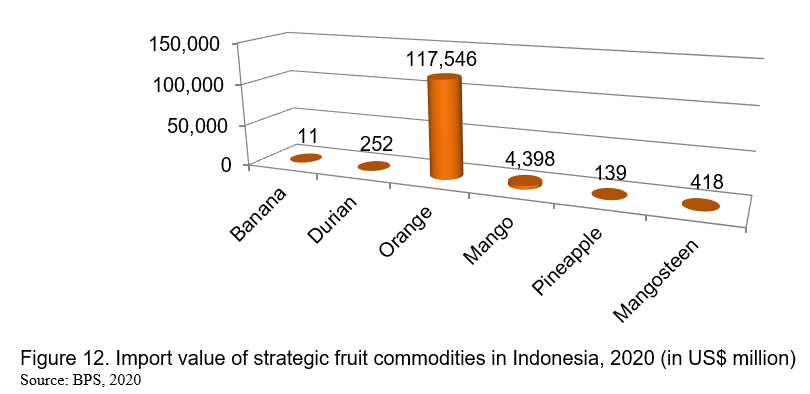

The highest value of strategic fruit commodities of Indonesia was orange (Figure 12). The value import of this commodity was extremely higher than those of particular fruit commodities such as mangosteen, durian, pineapple, and banana.

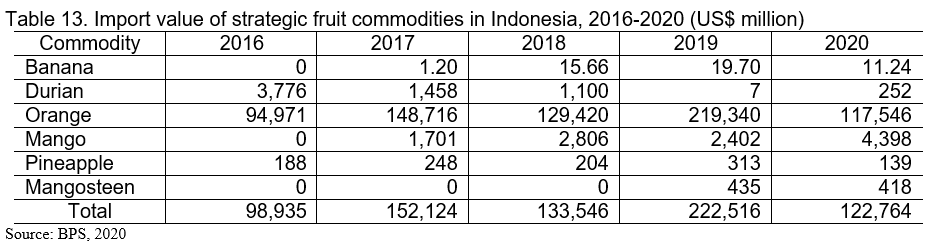

From 2016 to 2020, Indonesia's import value of strategic fruit commodities tended to increase, except for bananas and oranges. The extent of durian's import value was much greater compared to the import value of mangosteen, mango, and pineapple (Table 13).

The major countries origin of Indonesia’s import of strategic fruit commodities was China, especially for orange and banana. Other countries' origins can be seen in Table 14.

Strategic vegetables commodity import

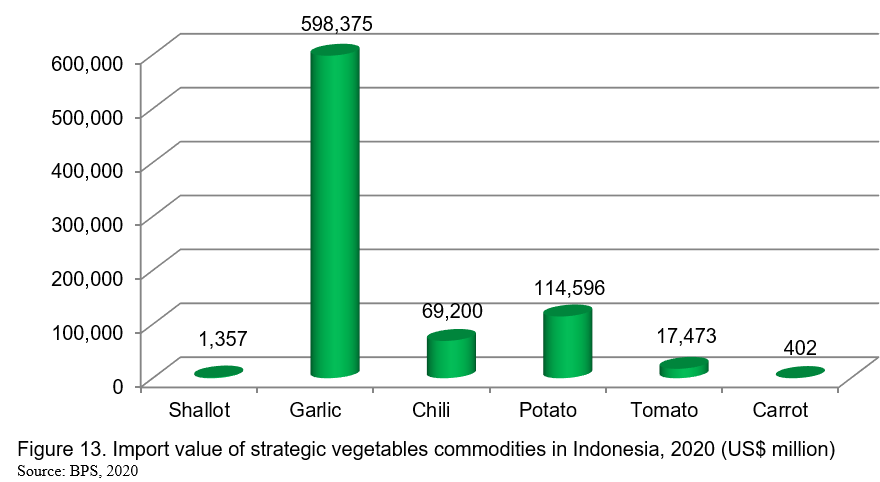

Indonesia imported garlic with a value of about US$583,375 million in 2020 (Figure 13), which was much higher than import values of other vegetable commodities such as potato, chilli, tomato, shallot, and carrot.

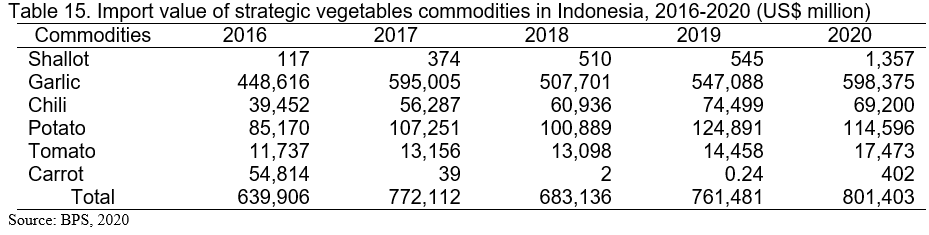

The growth of import value of strategic vegetable commodities of Indonesia tended to increase from 2016 to 2020, except for chilli. The highest growth of import value was shallot, followed by garlic, tomato, carrot, and potato (Table 15).

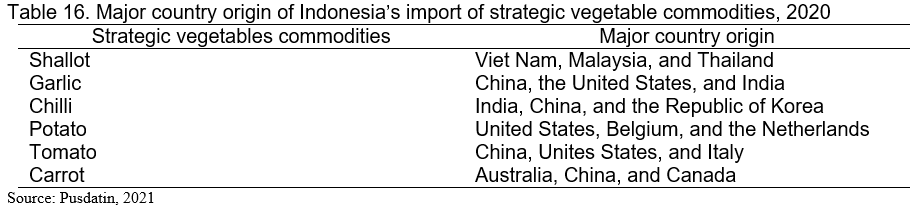

China was recorded as the major county origin of Indonesia's import of vegetable commodities, mainly garlic and tomato. Other countries’ origin of imported vegetable commodities was presented in Table 16.

FRUITS AND VEGETABLES INDUSTRIALIZATION

Conceptually, industrialization is not only in terms of technology and production practices but also in line with the size of business, resource control, operation, and a business model and linkages with buyers and suppliers. Those are to facilitate more effective and efficient vertical coordination in the production/distribution value chain (Gray and Boehlje, 2007).

In the case of Indonesia, the majority of strategic fruit and vegetable commodities were under the traditional business system. Many fruit and vegetable farmers are smallholders with dispersed and fragmented lands. The involvement of these farmers in the export market and the domestic supermarket was less than 2% and 15%, respectively. Consequently, Indonesia still imports and it tends to increase annually (Perdana, 2014).

Indonesia's smallholders have an opportunity to engage in structured markets such as export, modern retail, and food services. This can be developed by supply chain management toward bridging farmers and markets by finding solutions for misaligning and understanding producers and market requirements. It is strategically implemented in line with the complexities and dynamics of agribusinesses. There are four reasons why it is important to apply supply chain management to horticultural products (Saptana, et al., 2020), namely: (1) Horticulture products are classified as agricultural commodities with a high economic value that are easily damaged and must be handled quickly and appropriately; (2) Consumers are the most decisive of the desired product attributes based on their preferences; (3) Vertically integrated or coordinated supply chain management can increase added value and competitiveness; and (4) support supply and price stability through the integration of production processes and supply chain actors by implementing health protocols from upstream to downstream.

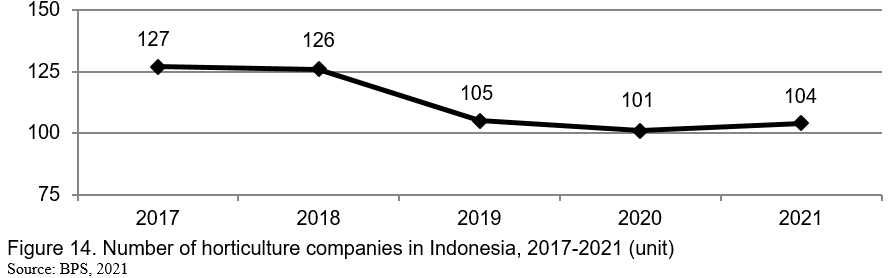

The implementation of industrialization was only carried out in limited scope within several numbers of horticulture companies. Figure 14 reveals that the total number of horticulture companies in Indonesia was only 103 units. Aggregately, the number of those companies decreased about 4.67% from 2017 to 2021. It noted that about 70% of the horticulture companies were located in Java, mostly in East Java, West Java, and Central Java. Detail number of horticulture companies by the province in Indonesia can be seen in Appendix 3.

Currently, two prominent large-scale horticulture companies are operating in Indonesia, such as PT. Great Giant Pineapple (GGP) exported the processed pineapple to 60 countries globally (GGP, 2021) and PT. Nusantara Tropical Farm (NTF) produces bananas with the brand export name of “Sunpride" (NTF, 2021). Both companies are located in Lampung province. Besides these companies, several existing horticulture companies, particularly the small and medium scales, also operate in fruit and vegetable businesses. Some of them, however, have not yet operated sustainably.

The above discussion shows an opportunity to develop the horticulture sub-sector, particularly fruit and vegetable commodities in Indonesia, through investments from national and international sources. Within industrialization, people in the horticulture sector can consistently develop the decisions and actions of producers based on market demand. It is noted that farmers and business entities can implement the industrialization of fruit and vegetable commodities through a partnership scheme (Syukur, et al., 2020).

POLICY SUPPORT TO FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

The basis policy framework for horticultural development in Indonesia is Law Number 13/2010 concerning Horticulture (GoI, 2010). This Law is specifically aimed at: (1) Utilizing and managing the horticultural resources optimally, accountably, and sustainably; (2) Fulfilling the needs, desires, tastes, aesthetics, and cultures of horticultural products and services; (3) Increasing the production, productivity, quality, value-added, competitiveness, and market share of horticultural products; (4) Enhancing the consumption of horticultural products and the utilization of services; (5) Providing employment and business opportunities; (6) Setting up the protection to horticultural farmers, businesses, and consumers nationally; (7) Expanding the sources of foreign exchange; and (8) Improving the health, welfare, and prosperity of people.

Based on Law Number 26/2020 concerning the implementation of Job Creation Law in the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2020), horticulture has the enormous economic potential to move the wheels of the economy, creating job and business opportunities upstream downstream linkages with other sectors in Indonesia. Therefore, it is necessary to particularly regulate seed business, including breeding, seed production, certification, and distribution and product grade system of seeds based on quality and price standards. Breeding, in particular, is carried out to maintain and improve the purity of existing types of variety or to produce new variety types. New varieties resulting from breeding to be launched must be registered before they are distributed. Breeding can be produced by domestic or introduction, which is carried out in seeds or parent materials that have not yet existed in Indonesia.

Apart from the above regulations, the Government of Indonesia (GoI) supports horticulture development, including fruit and vegetable commodities. They are:

- Import Recommendation for Horticulture Products (RIPH) for consumptions and raw material industries, including requirements, procedures, obligations, and sanctions. This regulation is a legal basis for RIPH issuance services, with the aim of (1) Increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of horticulture product import management; (2) Providing certainty in RIPH issuance services; and (3) Encouraging horticulture production through empowering farmers, and involving the role of business entities in the development of horticulture in Indonesia. The scope of this regulation includes the requirements, procedures, obligations, and sanctions for the issuance of RIPH. To obtain the RIPH, business entities, social institutions, and representative foreign/international institutions must meet administrative and technical requirements. The RIPH will issue through the Indonesian National Single Window portal under the Center for Plant Variety Protection and Agricultural Licensing (MoA, 2013, MoA, 2017, and MoA, 2019b);

- Technical guidelines for the implementation of garlic development as mandated in the regulation of the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture concerning RIPH. This guideline issues the mandatory provisions to importers, except the State-owned Enterprises (BUMN/SOEs), to plant garlic towards stabilizing its supply and price. The business entities must provide and submit a statement of ability to grow garlic domestically with a production of at least 5% of the volume of RIPH application per year, either alone or in partnership with farmers. The planting area size is determined by converting the targeted productivity of six-ton per hectare on average (DGH, 2017 and DGH, 2018); and

- Horticulture Market Information System (Sipashorti) website has launched facing industrial revolution 4.0 including information about farm activities, prices, supplies, and markets timely benefited for increasing the bargaining power of farmers, determining the basis for marketing policies for horticulture commodities, enhancing trade, as well as opening access to inter-island and local marketing to exports. This information is also useful as a basis for effective and efficient farming planning. This website can be accessed at http://hortikultura.pertanian.go.id, covering the price lists of horticulture commodities per province to the district at the farmer level to retail and the prices in the main market to the auction market daily. Apart from prices, this application also contains: (1) Supply data comprising monthly production sold at each collecting market price data; (2) Farming cost data including costs incurred in carrying out farming activities related to revenue and profit; (3) Marketing cost data consisting of supply chains of certain commodities along with price margins at each level of the supply chain from producers to consumers; and (4) Supplier data covering the commodity type and location based on biodata of suppliers (DGH, 2019);

Above all, the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture issues Regulation Number 40/2019 as one of the initiative reforms concerning the licensing procedures in the agricultural sector of the country (GoI, 2019c). It is implemented through simplifying and streamlining the procedures of agricultural business licenses toward promoting higher investment opportunities. The regulation comprises business and commercial/operational licenses in line with requirement and commitment based-online on a single submission system. The type and scope of the licenses comprise registration, recommendation, and certification for plantation, food crops, horticulture, and livestock sub-sectors. The implementation of this regulation can be viewed as a spirit to attract investors to develop the agricultural sector in Indonesia.

In terms of the horticulture sub-sector, the business license includes cultivation and seed provision applied by medium-large scale companies and individual or business entities, respectively. Commitments for horticulture cultivation activities comprise: (1) Feasibility study and work plan of businesses; (2) Environmental impact analysis and environmental management/monitoring assessment-based statutory regulation; and (3) Letter of cultivation rights.

The implementation of this regulation can be viewed as a spirit to attract investors to develop the agricultural sector in the country. It is strategically implemented by simplifying and streamlining the licensing procedures based on the commitment platform (Rafani and Sudaryanto, 2020).

CONCLUSION

Indonesia has great potential for horticulture, particularly fruit and vegetable production. These crops can be grown all over the country supported by existing natural resources. Unfortunately, Indonesia's fruit and vegetable commodities still face production issues toward fulfilling domestic consumption. Due to limited technology utilization and the low extent of industrialization, Indonesia still heavily relies on imports of fruits and vegetables. The Indonesian central government has successfully implemented certain policies supporting the development of fruit and vegetable commodities domestically. Therefore, there are huge opportunities that could involve domestic and foreign investments from the private sectors by implementing fruit and vegetable industrialization.

REFERENCES

BPS. 2020. Statistik Hortikultura 2020 (Statistics of Horticulture 2020). Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Statistik Perusahaan Hortikultura dan Usaha Hortikultura Lainnya (Statistics of Horticulture Establishment and Other Horticulture Business). Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

Davis and Langham. 1995. Agricultural Industrialization and Sustainable Development: A Global Perspective. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Vol. 27 (1), July 1995: 21-34. Cambridge University Press. Boston, Massachusetts.

DGH. 2017. Keputusan Drektur Jenderal Hortikultura Nomor 221 Tahun 2017 tentang Petunjuk Teknis Pelaksanaan Pengembangan Bawang Putih oleh Pelaku Usaha Impor Produk Hortikultura (Decree of the Director General of Horticulture Number 221/2017 on Technical Guidelines for the Implementation of Garlic Development by Horticultural Product Import Businesses).Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGH. 2018. Keputusan Drektur Jenderal Hortikultura Nomor 912 Tahun 2018 tentang Petunjuk Teknis Pengembangan Bawang Putih di Dalam Negeri (Decree of the Director General of Horticulture Number 221/2017 on Technical Guidelines for Domestic Garlic Development). Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGH. 2019. Pelayanan Informasi Pasar (PIP) online ujung tombak informasi agribisinis hortikultura (Market Information Service online as a spearhead of horticultural agribusiness information). Retrieved from: http://hortikultura.pertanian.go.id/?p=3257 (17 October 2021). Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GGP. 2021. PT Great Giant Pineapple. Retrieved from: https://www.greatgiantfoods.com/id/ (24 September 2021)

GoI. 2010. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 13 Tahun 2010 tentang Hortikultura (Law Number 13/2010 concerning Horticulture). Jakarta.

GoI. 2020. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2020 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional Tahun 2020-2024 (Presidential Regulation of Republic Indonesia Number 18/2020 on National Medium-Term Development Plan 2020-2024). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020. Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2020 tentang Cipta Kerja (Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation. Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

Gray and Boehlje. 2007. The Industrialization of Agriculture: Implications for Future Policy. Working Paper #07-10, October 2007. Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University. Indiana.

MoA. 2017. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 19 Tahun 2017 tentang Rekomendasi Impor Produk Hortikultura (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 39/2019 on Recommendations for the Import of Horticultural Products). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019a. Keputusan Meteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 141/2019 tentang Jenis Komoditas Tanaman Binaan Lingkup Kementerian Pertanian (Decree of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia Number 141/2019 concerning Types of Plant Commodities Assisted in the Scope of the Ministry of Agriculture). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019b. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 39 Tahun 2019 tentang Rekomendasi Impor Produk Hortikultura (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 39/2019 on Recommendations for the Import of Horticultural Products). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019c. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 40 Tahun 2019 tentang Tata Cara Perizinan Berusaha Sektor Pertanian (Regulation of the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture on Procedures for Business Licensing in Agricultural Sector). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta, Indonesia.

NTF. 2021. PT Nusantara Tropical Farm. Retrieved from: https://www.profilusaha.com/nusantara-tropical-fruit-pt (2 October 2021)

Perdana, T. 2014. Manajemen Rantai Pasok (Supply Chain Management). Retrieved from: https://www.unpad.ac.id/ (26 September 2021). Padjadjaran University. Bandung.

Pusdatin. 2021. Ekspor Komoditas Hortikultura Olahan Segar Berdasarkan Negara Tujuan, 2020 (Export of Processed Fresh Horticultural Commodities by Destination Country, 2020). Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Pertanian (Center for Agricultural Data and Information System). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

Rafani, I. and Sudaryanto, T. 2020. Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 40/2019 on Business Licensing Procedures in Agriculture Sector: Simplifying, Streamlining, and Promoting Investments. FFTC Journal of Agricultural Policy. Special issue: Plans and Experiences to Improve Agricultural Trade in the Asia Pacific Region, 31 December 2020. Retrieved from: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/e-journal/issue/2681

Rafani, M. I. 2014. Overview of Fruit Production, Marketing, and Research and Development System in Indonesia. Country Report submitted to Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region. Taiwan.

Saptana, Sumaryanto, and M. Suryadi.2020. Manajemen Rantai Pasok Produk Hortikultura dan Unggas pada Era New Normal (Supply Chain Management of Horticultural and Poultry Products in the New Normal Era). Artikel dalam Dampak Pandemi COVID-19: Perspektif Adaptasi dan Resiliensi Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian (Article in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adaptation Perspectives and Agricultural Socioeconomic Resilience). Editors: Suryana, A., I. W. Rusastra, T. Sudaryanto, and S. M. Pasaribu: 321-336. IAARD PRESS. Jakarta.

Syukur, M., V. Darwis1, C. R. Adawiyah. 2020. Pola Kemitraan Agribisnis Hortikultura Menyiasati Pandemi COVID-19 (Horticultural Agribusiness Partnership Patterns to deal with the COVID-19 PandemicImpact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Indonesia). Artikel dalam Dampak Pandemi Covid-19: Perspektif Adaptasi dan Resiliensi Sosial Ekonomi Pertanin (Article in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adaptation Perspectives and Agricultural Socioeconomic Resilience). Editors: Suryana, A., I. W. Rusastra, T. Sudaryanto, and S. M. Pasaribu. IAARD PRESS. Jakarta.

[1] According to Council on Food, Agriculture, and Resource Economics (1994), as cited in Davis and Langham (1995), agricultural industrialization refers to “the increasing consolidation of farms and to vertical coordination (contracting and integration) among the stages of its system”.

[2] Trade and Transportation Margin (TTM) is trader compensation as a good supplier, which is the difference between sale and purchase values (BPS, 2020)

Study of Production and Market Value for Horticulture Commodities in Indonesia

ABSTRACT

National population growth has increased the domestic demand for horticulture commodities. Geographically, Indonesia has great potential in leading the fruit and vegetable production in Southeast Asia. However, many factors lead to the lack of domestic production, including lack of quality control, fluctuating market price, overproduction, old-school farming technology, and weak regulation. This study aims to present the development and characteristics of horticultural crop agriculture, especially fruit and vegetables. In particular, it includes the government policies and regulations implemented within the framework of national agricultural development. The main section is to describe sociologically the current status of fruit and vegetable production and marketing in Indonesia. It also examines the latest production status, consumption trends, and market patterns for fruits and vegetables. There will be a general assessment of the agricultural industrialization status for fruits and vegetables in the final section. Horticulture industrialization itself has a strong correlation with the market chain and production status.

Keywords: fruit, vegetable, industrialization, policy, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

As an agricultural country, Indonesia has various landscapes and fertile soils that produce various agricultural products, including horticulture, particularly fruits and vegetables commodities. There are 60 types of fruits and 82 types of vegetables which are developed by the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture as presented in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 (MoA, 2019a). Among those commodities, there are some strategic fruit and vegetable categories, as presented in Figure 1.

The term of strategic fruits and vegetables is based on contribution substance. The contribution of these commodities can be categorized as greater than those of other commodities within the horticulture sub-sector in Indonesia. It is particularly related to the characteristics of the planted area, production, consumption, market, and other typical categories.

Objectives

Generally, this article discusses the agricultural industrialization[1]. The case of fruits and vegetables focuses on strategic commodities in Indonesia. Specifically, the objectives of this article are: (1) To describe Indonesia’s strategic fruits and vegetables status; (2) To deliberate the strategic fruit and vegetable industrialization in Indonesia; and (3) To identify and brief policy support to strategic fruit and vegetable production and market in Indonesia.

INDONESIAN FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

Planted area

In Indonesia, the unit of the production area of strategic fruit commodities differs from those of vegetable commodities. Fruit commodities are based on the harvested plant (tree or clump unit) since those are planted in scattered areas within irregular planting space and intercropping with other crops. Meanwhile, the production of vegetable commodities with a common monoculture system is in the form of harvested area (hectare unit).

Planted area of strategic fruit commodity

The harvested plant of strategic fruit commodities can be seen in Figure 2. Pineapple was recorded as the largest harvested plant among other strategic fruit commodities. It was followed by banana commodity. The smallest harvested plant was mangosteen.

During the last five years (2016-2020), besides pineapple, the harvested plant of bananas was quite large. It was noted that the harvested plant of durian increased significantly since 2018, namely about 30% (Table 1).

Planted area of strategic vegetable commodity

The largest harvested area of strategic vegetable commodities was chilli, followed by shallot. Meanwhile, the smallest harvested area was garlic (Figure 3).

Chilli still dominated among the harvested area of vegetable commodities from 2016 to 2020 (Table 2). The harvested area of garlic has significantly increased since 2018.

Production

Production of strategic fruit commodities

The production of strategic fruit commodities is shown in Figure 4. It reveals that the banana was the most productive commodity as compared to other strategic commodities. The lowest one was mangosteen.

In the last five-years (2016-2020), banana was the highest productive strategic fruit commodity. In addition, the production of mangosteen increased substantially by about 20% per annum (Table 3).

Production of strategic vegetable commodities

The production of strategic vegetable commodities was dominated by chilli (Figure 5). This commodity was superior compared with other strategic commodities. It was noted that garlic was quite minor in terms of production.

Among strategic vegetable commodities, garlic production was quite promising from 2016 to 2020 (Table 4). The production of this commodity started to increase in 2018.

Central producing area

The central producing areas of strategic fruit and vegetable commodities in Indonesia can be seen in Table 5. Most of the commodities are planted in Java Island, particularly in East Java, Central Java, and West Java.

Unlike vegetable crops which can be harvested at any time along the year, they can particularly harvest certain fruit crops for a certain season. Specifically, they include durian, orange, mango, pineapple, and mangosteen (Table 6).

Consumption

The extent of consumption of strategic fruit commodities in Indonesia can be seen in Table 7. It reveals that banana was the most consumed by Indonesians, followed by orange with a participation rate (CPR) of about 35.65% and 25.69%, respectively. The consumption growth of bananas tended to be a slight bit decrease. Meanwhile, the growth of orange, durian, and mango was increased positively, greater than 20%, from 2019 to 2020.

The CPR of strategic vegetable commodities was much higher than strategic fruit commodities, particularly shallot, garlic, and chilli (Table 8). These strategic vegetable commodities were used as the main ingredient in cooking food in Indonesia all the time.

Indonesia has a target to increase fruits and vegetables consumption from 260.2 kilograms per capita in 2020 to 316.3 kilograms per capita in 2024. In other words, the extent of fruits and vegetables consumption for the country population is targeted to be increased by about 5% annually (Figure 6).

Market

There are two general forms of the market characteristic of strategic fruits and vegetables commodities in Indonesia. First, farmers traditionally conduct it through certain places such as wet markets, stalls, and street traders. Second, it is carried out in modern systems by commercial entities (national and multinational companies) through the mini markets, supermarkets, retailers, and exports.

As an illustration, the following discusses the case of the shallot and chilli marketing system in Indonesia. These commodities are essential, which are the main ingredient of Indonesia’s cookeries and quite sensitive in terms of their distribution. As characterized as perishable commodities, shallot and chilli must be distributed promptly. Due to transportation problems and the harmful intervention of certain irresponsible traders, these commodities are sometimes volatile with price fluctuation. The next consequence is that it can lead to economic inflation in the country.

Figure 7 presents the trade distribution pattern of shallot involving farmer as producer – collector – trader – the consumer. Trade and Transportation Margin (TTM)[2] of shallot in 2019 reached 38.01% as a cumulative value chain. The respective TTM of retailer and collector was 19.05% and 15.93%. It was found that the province with the highest TTM was Papua Barat (134.78%), while the lowest one was Jambi (16.34%).

In the same period, the TTM of chilli was much higher than that of shallot (Figure 8), the cumulative value is 61.13% comprising the TTM of retailer (23.20%) and collector (30.93%). The province with the highest TTM was Kalimantan Tengah (98.69%), while the lowest was Bali (11.01%).

Export and import

Apart from domestic production, Indonesia still quite depends on imported fruits and vegetables commodities. In other words, the country has a trade imbalance in terms of export and import of these commodities. Indonesia imports strategic fruit and vegetable commodities of about 69% and 66%, respectively (Figure 9).

Strategic fruits commodity export

The highest export value of strategic fruit commodities was pineapple, followed by mangosteen. The extent of export value of these commodities was much greater than those of other strategic fruit commodities, namely banana, mango, orange, and durian (Figure 10).

During the last five years (2016-2020), the export values of durian, banana, mangosteen, orange, and mango were quite insignificant compared with pineapple. Meanwhile, the export values of bananas and orange tended to decrease during the periods (Table 9).

The export destination countries of Indonesia’s strategic fruit commodities are presented in Table 10. It comprises the major followed by the rest export destination countries.

Strategic vegetables commodity export

Chilli and shallot were the dominant export value of strategic vegetable commodities compared to potato, tomato, garlic, and carrot. Figure 11 shows that the extent of chilli and shallot export values was almost five times higher than the export values of potato, tomato, garlic, and carrot.

From 2016 to 2020, the extent of value export of shallot, chilli, potato, and carrot was considerably great. This was particularly because of the highest export value of these commodities in 2020 (Table 11).

The export destination of Indonesia’s strategic vegetable commodities was Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines. It also includes certain countries in other regions (Table 12).

Strategic fruits commodity import

The highest value of strategic fruit commodities of Indonesia was orange (Figure 12). The value import of this commodity was extremely higher than those of particular fruit commodities such as mangosteen, durian, pineapple, and banana.

From 2016 to 2020, Indonesia's import value of strategic fruit commodities tended to increase, except for bananas and oranges. The extent of durian's import value was much greater compared to the import value of mangosteen, mango, and pineapple (Table 13).

The major countries origin of Indonesia’s import of strategic fruit commodities was China, especially for orange and banana. Other countries' origins can be seen in Table 14.

Strategic vegetables commodity import

Indonesia imported garlic with a value of about US$583,375 million in 2020 (Figure 13), which was much higher than import values of other vegetable commodities such as potato, chilli, tomato, shallot, and carrot.

The growth of import value of strategic vegetable commodities of Indonesia tended to increase from 2016 to 2020, except for chilli. The highest growth of import value was shallot, followed by garlic, tomato, carrot, and potato (Table 15).

China was recorded as the major county origin of Indonesia's import of vegetable commodities, mainly garlic and tomato. Other countries’ origin of imported vegetable commodities was presented in Table 16.

FRUITS AND VEGETABLES INDUSTRIALIZATION

Conceptually, industrialization is not only in terms of technology and production practices but also in line with the size of business, resource control, operation, and a business model and linkages with buyers and suppliers. Those are to facilitate more effective and efficient vertical coordination in the production/distribution value chain (Gray and Boehlje, 2007).

In the case of Indonesia, the majority of strategic fruit and vegetable commodities were under the traditional business system. Many fruit and vegetable farmers are smallholders with dispersed and fragmented lands. The involvement of these farmers in the export market and the domestic supermarket was less than 2% and 15%, respectively. Consequently, Indonesia still imports and it tends to increase annually (Perdana, 2014).

Indonesia's smallholders have an opportunity to engage in structured markets such as export, modern retail, and food services. This can be developed by supply chain management toward bridging farmers and markets by finding solutions for misaligning and understanding producers and market requirements. It is strategically implemented in line with the complexities and dynamics of agribusinesses. There are four reasons why it is important to apply supply chain management to horticultural products (Saptana, et al., 2020), namely: (1) Horticulture products are classified as agricultural commodities with a high economic value that are easily damaged and must be handled quickly and appropriately; (2) Consumers are the most decisive of the desired product attributes based on their preferences; (3) Vertically integrated or coordinated supply chain management can increase added value and competitiveness; and (4) support supply and price stability through the integration of production processes and supply chain actors by implementing health protocols from upstream to downstream.

The implementation of industrialization was only carried out in limited scope within several numbers of horticulture companies. Figure 14 reveals that the total number of horticulture companies in Indonesia was only 103 units. Aggregately, the number of those companies decreased about 4.67% from 2017 to 2021. It noted that about 70% of the horticulture companies were located in Java, mostly in East Java, West Java, and Central Java. Detail number of horticulture companies by the province in Indonesia can be seen in Appendix 3.

Currently, two prominent large-scale horticulture companies are operating in Indonesia, such as PT. Great Giant Pineapple (GGP) exported the processed pineapple to 60 countries globally (GGP, 2021) and PT. Nusantara Tropical Farm (NTF) produces bananas with the brand export name of “Sunpride" (NTF, 2021). Both companies are located in Lampung province. Besides these companies, several existing horticulture companies, particularly the small and medium scales, also operate in fruit and vegetable businesses. Some of them, however, have not yet operated sustainably.

The above discussion shows an opportunity to develop the horticulture sub-sector, particularly fruit and vegetable commodities in Indonesia, through investments from national and international sources. Within industrialization, people in the horticulture sector can consistently develop the decisions and actions of producers based on market demand. It is noted that farmers and business entities can implement the industrialization of fruit and vegetable commodities through a partnership scheme (Syukur, et al., 2020).

POLICY SUPPORT TO FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

The basis policy framework for horticultural development in Indonesia is Law Number 13/2010 concerning Horticulture (GoI, 2010). This Law is specifically aimed at: (1) Utilizing and managing the horticultural resources optimally, accountably, and sustainably; (2) Fulfilling the needs, desires, tastes, aesthetics, and cultures of horticultural products and services; (3) Increasing the production, productivity, quality, value-added, competitiveness, and market share of horticultural products; (4) Enhancing the consumption of horticultural products and the utilization of services; (5) Providing employment and business opportunities; (6) Setting up the protection to horticultural farmers, businesses, and consumers nationally; (7) Expanding the sources of foreign exchange; and (8) Improving the health, welfare, and prosperity of people.

Based on Law Number 26/2020 concerning the implementation of Job Creation Law in the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2020), horticulture has the enormous economic potential to move the wheels of the economy, creating job and business opportunities upstream downstream linkages with other sectors in Indonesia. Therefore, it is necessary to particularly regulate seed business, including breeding, seed production, certification, and distribution and product grade system of seeds based on quality and price standards. Breeding, in particular, is carried out to maintain and improve the purity of existing types of variety or to produce new variety types. New varieties resulting from breeding to be launched must be registered before they are distributed. Breeding can be produced by domestic or introduction, which is carried out in seeds or parent materials that have not yet existed in Indonesia.

Apart from the above regulations, the Government of Indonesia (GoI) supports horticulture development, including fruit and vegetable commodities. They are:

Above all, the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture issues Regulation Number 40/2019 as one of the initiative reforms concerning the licensing procedures in the agricultural sector of the country (GoI, 2019c). It is implemented through simplifying and streamlining the procedures of agricultural business licenses toward promoting higher investment opportunities. The regulation comprises business and commercial/operational licenses in line with requirement and commitment based-online on a single submission system. The type and scope of the licenses comprise registration, recommendation, and certification for plantation, food crops, horticulture, and livestock sub-sectors. The implementation of this regulation can be viewed as a spirit to attract investors to develop the agricultural sector in Indonesia.

In terms of the horticulture sub-sector, the business license includes cultivation and seed provision applied by medium-large scale companies and individual or business entities, respectively. Commitments for horticulture cultivation activities comprise: (1) Feasibility study and work plan of businesses; (2) Environmental impact analysis and environmental management/monitoring assessment-based statutory regulation; and (3) Letter of cultivation rights.

The implementation of this regulation can be viewed as a spirit to attract investors to develop the agricultural sector in the country. It is strategically implemented by simplifying and streamlining the licensing procedures based on the commitment platform (Rafani and Sudaryanto, 2020).

CONCLUSION

Indonesia has great potential for horticulture, particularly fruit and vegetable production. These crops can be grown all over the country supported by existing natural resources. Unfortunately, Indonesia's fruit and vegetable commodities still face production issues toward fulfilling domestic consumption. Due to limited technology utilization and the low extent of industrialization, Indonesia still heavily relies on imports of fruits and vegetables. The Indonesian central government has successfully implemented certain policies supporting the development of fruit and vegetable commodities domestically. Therefore, there are huge opportunities that could involve domestic and foreign investments from the private sectors by implementing fruit and vegetable industrialization.

REFERENCES

BPS. 2020. Statistik Hortikultura 2020 (Statistics of Horticulture 2020). Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Statistik Perusahaan Hortikultura dan Usaha Hortikultura Lainnya (Statistics of Horticulture Establishment and Other Horticulture Business). Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

Davis and Langham. 1995. Agricultural Industrialization and Sustainable Development: A Global Perspective. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Vol. 27 (1), July 1995: 21-34. Cambridge University Press. Boston, Massachusetts.

DGH. 2017. Keputusan Drektur Jenderal Hortikultura Nomor 221 Tahun 2017 tentang Petunjuk Teknis Pelaksanaan Pengembangan Bawang Putih oleh Pelaku Usaha Impor Produk Hortikultura (Decree of the Director General of Horticulture Number 221/2017 on Technical Guidelines for the Implementation of Garlic Development by Horticultural Product Import Businesses).Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGH. 2018. Keputusan Drektur Jenderal Hortikultura Nomor 912 Tahun 2018 tentang Petunjuk Teknis Pengembangan Bawang Putih di Dalam Negeri (Decree of the Director General of Horticulture Number 221/2017 on Technical Guidelines for Domestic Garlic Development). Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGH. 2019. Pelayanan Informasi Pasar (PIP) online ujung tombak informasi agribisinis hortikultura (Market Information Service online as a spearhead of horticultural agribusiness information). Retrieved from: http://hortikultura.pertanian.go.id/?p=3257 (17 October 2021). Directorate General of Horticulture. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GGP. 2021. PT Great Giant Pineapple. Retrieved from: https://www.greatgiantfoods.com/id/ (24 September 2021)

GoI. 2010. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 13 Tahun 2010 tentang Hortikultura (Law Number 13/2010 concerning Horticulture). Jakarta.

GoI. 2020. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2020 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional Tahun 2020-2024 (Presidential Regulation of Republic Indonesia Number 18/2020 on National Medium-Term Development Plan 2020-2024). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020. Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2020 tentang Cipta Kerja (Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation. Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

Gray and Boehlje. 2007. The Industrialization of Agriculture: Implications for Future Policy. Working Paper #07-10, October 2007. Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University. Indiana.

MoA. 2017. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 19 Tahun 2017 tentang Rekomendasi Impor Produk Hortikultura (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 39/2019 on Recommendations for the Import of Horticultural Products). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019a. Keputusan Meteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 141/2019 tentang Jenis Komoditas Tanaman Binaan Lingkup Kementerian Pertanian (Decree of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia Number 141/2019 concerning Types of Plant Commodities Assisted in the Scope of the Ministry of Agriculture). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019b. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 39 Tahun 2019 tentang Rekomendasi Impor Produk Hortikultura (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 39/2019 on Recommendations for the Import of Horticultural Products). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2019c. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 40 Tahun 2019 tentang Tata Cara Perizinan Berusaha Sektor Pertanian (Regulation of the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture on Procedures for Business Licensing in Agricultural Sector). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta, Indonesia.

NTF. 2021. PT Nusantara Tropical Farm. Retrieved from: https://www.profilusaha.com/nusantara-tropical-fruit-pt (2 October 2021)

Perdana, T. 2014. Manajemen Rantai Pasok (Supply Chain Management). Retrieved from: https://www.unpad.ac.id/ (26 September 2021). Padjadjaran University. Bandung.

Pusdatin. 2021. Ekspor Komoditas Hortikultura Olahan Segar Berdasarkan Negara Tujuan, 2020 (Export of Processed Fresh Horticultural Commodities by Destination Country, 2020). Pusat Data dan Sistem Informasi Pertanian (Center for Agricultural Data and Information System). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

Rafani, I. and Sudaryanto, T. 2020. Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 40/2019 on Business Licensing Procedures in Agriculture Sector: Simplifying, Streamlining, and Promoting Investments. FFTC Journal of Agricultural Policy. Special issue: Plans and Experiences to Improve Agricultural Trade in the Asia Pacific Region, 31 December 2020. Retrieved from: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/e-journal/issue/2681

Rafani, M. I. 2014. Overview of Fruit Production, Marketing, and Research and Development System in Indonesia. Country Report submitted to Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region. Taiwan.

Saptana, Sumaryanto, and M. Suryadi.2020. Manajemen Rantai Pasok Produk Hortikultura dan Unggas pada Era New Normal (Supply Chain Management of Horticultural and Poultry Products in the New Normal Era). Artikel dalam Dampak Pandemi COVID-19: Perspektif Adaptasi dan Resiliensi Sosial Ekonomi Pertanian (Article in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adaptation Perspectives and Agricultural Socioeconomic Resilience). Editors: Suryana, A., I. W. Rusastra, T. Sudaryanto, and S. M. Pasaribu: 321-336. IAARD PRESS. Jakarta.

Syukur, M., V. Darwis1, C. R. Adawiyah. 2020. Pola Kemitraan Agribisnis Hortikultura Menyiasati Pandemi COVID-19 (Horticultural Agribusiness Partnership Patterns to deal with the COVID-19 PandemicImpact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Indonesia). Artikel dalam Dampak Pandemi Covid-19: Perspektif Adaptasi dan Resiliensi Sosial Ekonomi Pertanin (Article in the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adaptation Perspectives and Agricultural Socioeconomic Resilience). Editors: Suryana, A., I. W. Rusastra, T. Sudaryanto, and S. M. Pasaribu. IAARD PRESS. Jakarta.

[1] According to Council on Food, Agriculture, and Resource Economics (1994), as cited in Davis and Langham (1995), agricultural industrialization refers to “the increasing consolidation of farms and to vertical coordination (contracting and integration) among the stages of its system”.

[2] Trade and Transportation Margin (TTM) is trader compensation as a good supplier, which is the difference between sale and purchase values (BPS, 2020)