ABSTRACT

Coffee plays an important role in the economic activities of Indonesia. Even though the country is ranked as the fourth largest coffee exporter in the world after Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia, the productivity of Indonesian coffee is lower than its potential productivity. Therefore, there is a need to accelerate the Indonesian coffee productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness developments. It can be implemented by employing certification farms, encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, and expanding the geographical indications. The following actions are recommended. First, establish a clear legal framework with written codes of conduct and other necessary consensus provisions that benefit both smallholders and global coffee corporations. Second, facilitate networking opportunities for young farmers to connect with experienced coffee growers, industry experts, and other stakeholders through encouraging mentorship programs where experienced farmers mentor and guide young farmers. Third, set up careful planning, collaboration, and a commitment to preserving the unique qualities and cultural heritage of each coffee-producing region toward increasing the recognition and value of Indonesian coffee in both domestic and international markets.

Keywords: coffee, productivity, farm, farmer, agribusiness, development, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

The plantation is the first sub-sector that contributes around 3.94% to the agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) of Indonesia. This sub-sector provides raw materials for industry, absorbs labor, and earns foreign exchange for the country (BPS, 2021). As one of the plantation commodities, coffee plays an important role in the economic activities of Indonesia. This commodity has a total export value of US$822 million, after palm oil (US$19,712 million), rubber (US$3,247 million), cocoa (US$1,244 million), and coconut (US$1,172 million). Indonesia is also listed as the fourth largest coffee exporter in the world with a share of around 4.80%, after Brazil (25.81%), Vietnam (19.33%), and Colombia (9.41%).

The productivity of Indonesian coffee has only reached 0.81 tons per hectare; which is still lower than its potential productivity i.e. three tons per hectare (ICCRI, 2019). There is an imbalance between the growth of national coffee consumption and the level of coffee production. Many issues and challenges affect coffee productivity; the key issues are the poor quality of human resources and ineffective government policy strategy (Effendi et al., 2019). Therefore, the acceleration of coffee productivity is essential. It is expected to be able to improve the welfare of the community by employing people in the central coffee-producing areas through improving capacity to compete in the international coffee market. Hence, this paper discusses the acceleration of productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness development based on the overview of coffee in Indonesia.

INDONESIAN COFFEE OVERVIEW

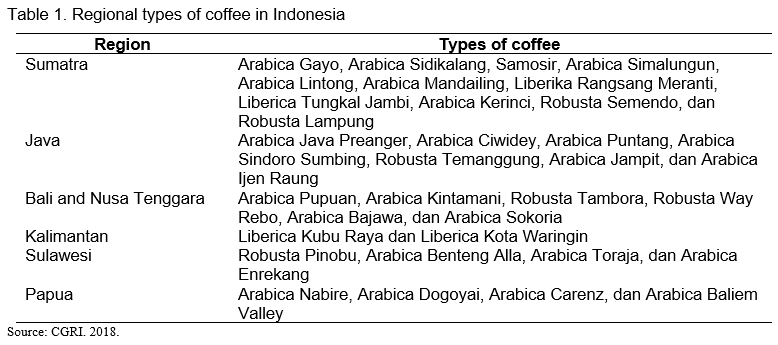

Coffee plants were first cultivated in Indonesia around 3-4 centuries ago. In general, Indonesian coffee consists of four types, namely Arabica (Coffea arabica), Robusta (Coffea canephora), Liberika (Coffea liberica), and Ekselsa (Coffea exelsa). However, the types that are most widely cultivated are Robusta and Arabica with a proportion of around 77.18% and 22.82%, respectively (ICADIS, 2022). Coffee is cultivated throughout the country in certain central region producing areas with their specific types. The geographical location of the origin of each coffee gives uniqueness and differences in the sensory characteristics produced. Table 1 shows the regional types of coffees in Indonesia. Most of the coffee plantations are managed by smallholder plantations (98.14%), the rest by large state plantations (1.11%) and large private plantations (0.75%).

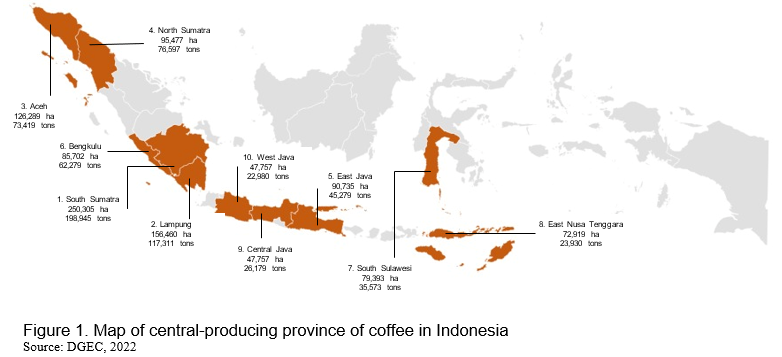

Coffee can be grown in all areas of Indonesia. However, coffee plantations are predominantly found in the Sumatra region i.e., Aceh, North Sumatra, Bengkulu, South Sumatra, and Lampung provinces. This region contributes about 73% to the total area and production of central coffee-producing areas of the country. Figure 1 shows the map of the top ten central coffee-producing provinces in Indonesia. It contributes about 77% to the total area and production of coffee in Indonesia. The highest is South Sumatra province with a total area of 250,305 hectares and production of 198,945 tons, while the lowest is West Java province with a total area of 47,757 hectares and production of 22,980 tons.

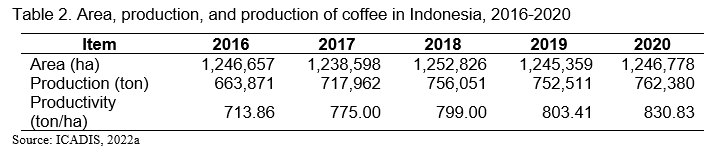

The coffee plantation area in Indonesia is recorded at 1,250,452 hectares with a total of 1,634,914 household farmers (DGEC 2022). The performance of Indonesian coffee over the last five years (2016-2020) has shown quite positive. The area has slightly grown by 0.01% per year, production at 3.57% per year, and productivity at 3.91% per year (Table 2). Indonesia is the second largest coffee area in the world after Brazil (1,837,302 hectares). However, the national coffee production (773,409 tons) is still below the world’s main major producing countries such as Brazil (3,194,736 tons), Vietnam (1,613,949 tons), and Colombia (833,400 tons).

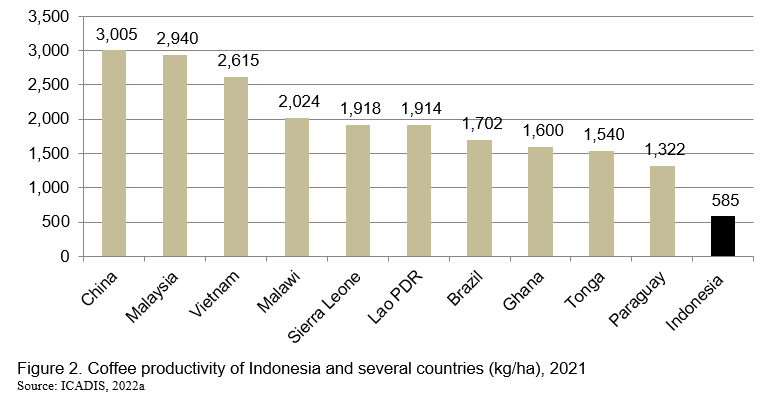

The average productivity of Indonesian coffee is around 585 kg/ha. Indonesia is ranked 37th in the world or far below China with productivity reaching 30,055 kg/ha or lower than other ASEAN countries such as Malaysia 29,399 kg/ha and Vietnam 26,147 kg/ha (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the average Indonesian coffee consumption is recorded at around 0.88 kg/ha/year (WPR, 2023) or far below consumption in several European countries (8.60 kg/capita/year). Other data sources (ICO, 2022) show that Indonesia ranks 5th in the world with a total coffee consumption of 300 tons per year, below the European Union (2,415 tons/year), the United States (1,619 tons/year), Brazil (1,344 tons/year), and Japan (443 tons/year).

It is noted that accelerating coffee productivity is also expected to fulfill the domestic consumption trend of coffee in Indonesia. Currently, coffee is available everywhere created by baristas which are spread across several coffee shops. However, it needs to be emphasized that the raw materials must come from domestic sources, without relying on imports. It is just a precaution so that coffee consumers’ tastes do not choose imported coffee towards appreciating domestic products (love of the homeland) because Indonesian coffee production is still abundant (annual production and consumption are 793,193 tons and 379,655 tons, respectively). The country only imports coffee by about 4.42% (ICADIS, 2022a).

ACCELERATION OF COFFEE PRODUCTIVITY

Farms

Currently, some coffee plants are classified as unproductive because they are already in the old and damaged category, which is around 10.45% of the total plantation area in Indonesia. Even though there has been a decrease in the proportion of old and damaged plants by around 4.51% per year over the last five years (2016-2020), the existence of productive plants is relatively not optimal in replacing the presence of these old and damaged plants. The contribution of productive plants is around 75.06% with quite low growth i.e., 0.28% per year. Meanwhile, the existence of immature plants which are expected to support the existence of mature plants and replace old and damaged plants, the contribution is quite good, namely around 14.48% with a growth of 2.58% per year. However, the maintenance of these immature plantations and those that are already considered productive needs to be carried out seriously and sustainably.

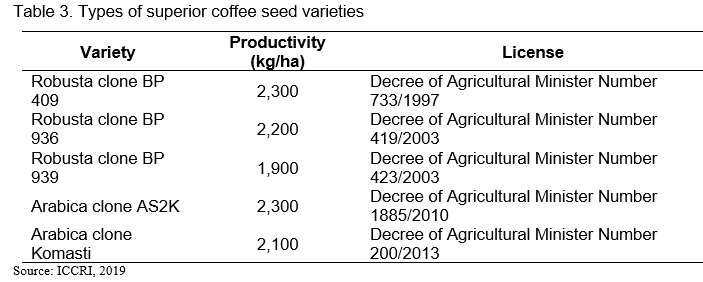

Accelerating coffee productivity can be carried out in a planned manner so as not to disrupt its supply and interests of farmers’ livelihoods. One of the strategic options is the implementation of replanting coffee for smallholders by replacing non-productive plants with the introduction of superior seed varieties. Several superior seed varieties are available as presented in Table 3.

It is challenging to encourage smallholders to be involved in the replanting through the introduction of superior coffee seeds, especially for those who much depend their livelihood on coffee farms. This should be followed by implementing certification program.

Indonesia has implemented certain coffee certifications including Utz-Kapeh, Organic such as Japan Agricultural Standard (JAS), European Union (EU), and United States Department of Agriculture/National Organic Program (USDA/NOP), Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C), Indonesian Sustainable Coffee (ISCo) Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP), Rainforest Alliance, and Fair Trade. These certification programs require the fulfillment of defined indicators covering social, environmental, and economic sustainability, and product traceability. Nevertheless, coffee producers give various responses including the confusion at the farmer level and certification fees issue. Direct contact between buyer and producer by ignoring middlemen also provides a case sensitive in implementing the certification programs (Wahyudi and Jati, 2012).

Another noticeable certification is the eco-certification scheme. This certification scheme in the coffee sector emerged during the early 1990s in conjunction with rising concerns about the environment and developed rapidly in this century. The scheme is aimed at promoting environmentally friendly and sustainable coffee production practices. It is typically designed to ensure that coffee is grown and processed in a way that minimizes harm to the environment, protects the rights and well-being of coffee farmers and workers, and produces high-quality coffee beans. Three studies related to the implementation of eco-certification schemes are discussed below.

- The study of Ibnu (2017) emphasizes two points. First, farmers’ knowledge about the certification schemes is low since they generally only cover the recommended activities and unacceptable practices that should be prevented within their scheme. Farmers are simply not aware of differences between the certification schemes and can therefore not think of attribute levels that go beyond their scheme. Second, the incorporation of different certification attributes related to tangible economic aspects, but also aspects related to farmer’s preferences regarding organizational capacity or skills (e.g. what is their need regarding skill development) may offer interesting, additional insights.

- The study of Arifin (2022) concludes two things. First, even though eco-certified coffee has claimed an increasingly large share of global sales, this trend has not had much impact on farmgate prices for Indonesian beans, mostly because the price transmission elasticity of the global price of coffee is very small. It does have the potential to strengthen social capital and improve community cooperative governance in coffee-producing regions, as the partnerships generally require the establishment of farmers’ organizations and the adherence to certain codes of conduct. Second, improving the welfare of smallholders is a complex challenge by itself, as their economies of scale are quite limited. Policy reforms could be undertaken to upgrade the quantity and quality of Indonesian coffee, to ensure the viability of empowerment mechanisms, and to enhance social capital and other institutional arrangements.

- The case study of Arifin et. al. (2022) in one of the central-producing areas of coffee in Lampung province related to partnership for the sustainable coffee certification shows three notifications. First, there is some selection or self-selection of partnership farmers for sustainability certifications based on the following important factors i.e., the age and education of the household head, land holding size of the coffee farm, and the proximity or the distance from house to rural cooperatives. Second, partnership farmers earn higher farm income than their neighbors who do not join a partnership, particularly due to the high number of productive family members aged 15-65. Third, implementing sustainability certification schemes has somehow positively affected the trust level between smallholders and corporations.

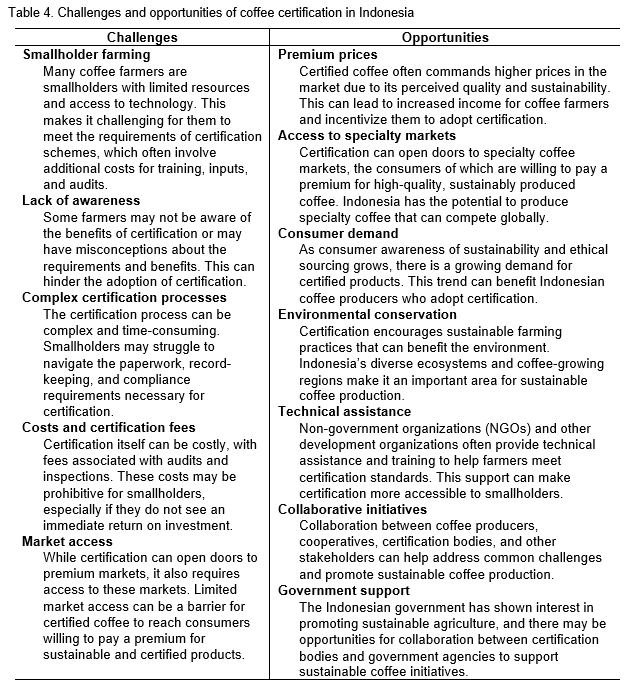

Based on the aforementioned discussions, we underline that the implementation of coffee certification in Indonesia has a range of challenges and opportunities (Table 4). It is believed that the coffee industry is dynamic, and conditions may have evolved since then.

Farmers

The performance of coffee farmers is linearly related to their characteristics. In other words, the rise and fall of coffee farming is largely determined by the existence management of the human resources (farmers). Currently there are 38.70 million Indonesian farmers, of which around 67.20% are classified as productive farmers (BPS, 2022).

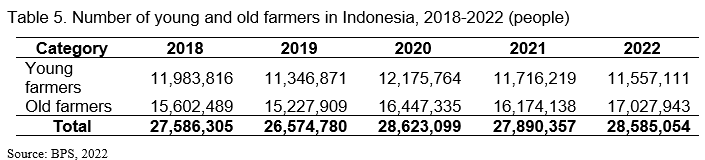

In general, Indonesian farmers can be divided into two productive groups based on age, namely: (1) Young farmers (age 19-39 years); and (2) Old farmers (age 40-60 years). Currently, coffee farming is mostly carried out by older farmers. Table 5 indicates that the composition of old farmers is higher than that of young farmers i.e., 59.57% vs. 40.43%). During the last five years (2018-2022), the number of young farmers has decreased by around 0.79% per year and conversely the number of old farmers has increased by approximately 2.31% per year (Table 5).

The discrepancy in the composition of the number of young and old farmers should be a concerned. There are at least two characteristics that are embedded in old farmers. First, old farmers have less optimal outpouring of energy due to a decrease in work productivity. Second, old farmers have low quality of farming practices due to stuttering about technology. In addition, the educational level of Indonesian farmers is classified as low educated, namely around 30-40% have only completed elementary school (SD) and 39% have not attended school/have not completed elementary school (ICADIS, 2022b).

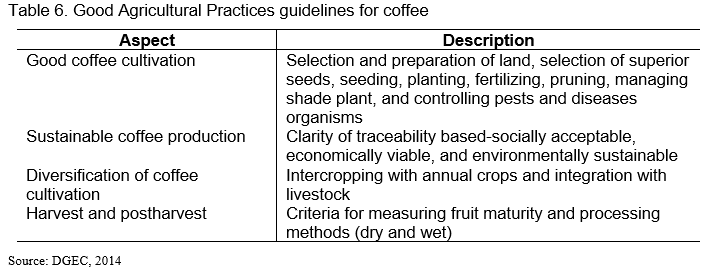

All of the factors above can become obstacles in efforts to accelerate the increase in farming productivity (including coffee) which in fact requires productive farmers’ requirements related to the application of technology. One of them is the application of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) for coffee farming (Table 6).

The above guidelines (Table 6) are basic. In other words, the content is dynamic according to technological developments and needs. But implicitly its application requires progressive farmers from relatively young ages. This has recently become a phenomenon since many young farmers are reluctant to get involved in agriculture.

It can be said that the regeneration of farmers has been slow in Indonesia due to the reluctance of the younger generation and some parents’ objections to their children working in agriculture. This relates to subjective perceptions (stereotypes) towards the existence of agricultural employment. The younger generation often views agriculture as an unpopular career path and has many drawbacks (low financial returns), synonymous with poverty, low prestige, and no chance of success in the future. Meanwhile, they prefer job choices with high mobility and more promising prospects.

The perceptions of the younger generation which tend to lead to doubt (skepticism) and could form negative perceptions of agriculture which are not easy to overcome. Especially if it is combined with the assumption that farming is synonymous with poverty, low education, and dirty work that relies more on physical ability rather than intelligence. This should be addressed wisely while motivating the younger generation to build a positive perception of the agricultural sector so that they can overcome stereotypes that encourage identity gaps.

With such a large population, Indonesia has the opportunity to be more advanced regarding the availability of production labor resources and consumption markets. One opportunity that can be explored is increasing the nation’s productivity, especially from human resources of productive age (demographic dividend) which is currently in sight[1]. However, it needs to be emphasized that the demographic dividend can be an advantage (window of opportunity) and conversely, it can also bring losses (window of disaster). It depends on how it is managed because the demographic dividend must not only be filled with human resources in terms of quantity but also being prepared with human resources in terms of quality. Good management of the demographic dividend will produce quality human resources, or in other words, increase the Human Development Index (HDI). Therefore, optimizing the management of the demographic dividend to increase the HDI is an absolute necessity that must be implemented in a planned, measurable, and sustainable manner.

The involvement of the younger generation is essential in accelerating Indonesian coffee productivity, especially in the context of welcoming Golden Indonesia 2045 which really hopes for the participation of the younger generation to fill it[2]. Do not let the bird in your hands fly away without knowing the jungle. So, it must be tied adaptively and flexibly.

Agribusiness

Agribusiness has a much wider scope of understanding than just the notion of farming or primary agriculture (Krisnamurthi, 2020). It comprises a series of systems that cover several upstream, on-farms, downstream, and support services sub-systems. In this case, the paper focuses on the agribusiness subsystem of supporting services, mainly more specifically related to aspects of coffee geographical indications.

The geographical indications indicate the area of origin of goods and products according to geographical and environmental factors (including natural factors, human factors, or a combination of both) which give reputation, quality, and certain characteristics to the goods and products produced. This is an exclusive right that is granted to holders of registered geographical indications, that is, as long as the reputation, quality, and characteristics that serve as the basis for the protection of geographical indications still exist (MoLHR, 2019).

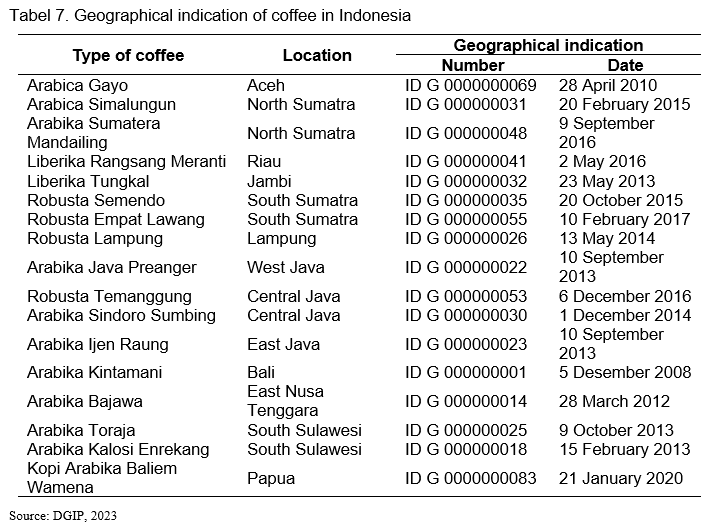

Several types of coffee have been listed in geographical indications (Table 7). There is an opportunity to register several other specific types of coffee in Indonesia, where agribusiness engineering related to this geographical indication is important in accelerating Indonesian coffee productivity. However, it should be noted that its implementation cannot be separated from the introduction of superior varieties that comply with geographical indication requirements, application of agricultural precision, consumption campaigns, provision of incentives for the domestic market, and increased export promotion. This must be in line with development policies including protecting national production, securing the domestic market, increasing quality requirements, formulating prices, and strengthening farmer institutions to achieve an efficient and effective coffee development program both domestically and internationally.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Accelerating coffee productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness development is strategically implemented in Indonesia. It can be implemented by employing certification farms, encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, and expanding the geographical indications.

Indonesia is a huge country with different geographical landscapes and human resource characteristics. Therefore, it is important to recognize that while coffee certification can bring numerous benefits, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Different certification programs have varying requirements and focus areas, and their success depends on factors such as the commitment of farmers, access to resources, and the effectiveness of support systems in place. It is recommended to establish a clear legal framework with written codes of conduct and other necessary consensus provisions that benefit both smallholders and global coffee corporations. It should be noted that the complexity of partnership rules, contracts, and regulations might be quite specific by crop, geographic characteristics, and value systems among smallholders and global corporations. Hence, it may be interesting to further investigate farmer’s ideas and preferences for price premium alternatives.

Encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, in coffee farms is essential for the sustainability and growth of the coffee industry in Indonesia. It requires a multi-faceted approach involving government, industry stakeholders, and the community. By addressing education, finance, market access, and sustainability, it can create an environment where young people are motivated to pursue a career in coffee farming and contribute to the industry's growth and development. It is recommended to facilitate networking opportunities for young farmers to connect with experienced coffee growers, industry experts, and other stakeholders. At the same time, encourage mentorship programs where experienced farmers mentor and guide young farmers.

Expanding the geographical indications of Indonesian coffee farms can help protect and promote the unique qualities and origins of coffee produced in different regions of the country. There is a need to identify suitable regions, accomplish public awareness and promotion, employ traceability and labeling, develop quality standards, and improve the effectiveness of geographical indications continuously. It is recommended to set up careful planning, collaboration, and a commitment to preserving the unique qualities and cultural heritage of each coffee-producing region toward increasing the recognition and value of Indonesian coffee in both domestic and international markets.

REFERENCES

ANA. 2023. Government prepares strategic measures to welcome demographic dividend. Antara News Agency. Jakarta.

Andoko, E., Zmudczynska, E., and Wan Yu Liu, W. Y. 2020. A Strategy Review of the Coffee Policies and Development by the Indonesian Government. Retrieved from: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1874 (5 September 2023). Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region (FFTC-AP). Taipei.

Arifin, B. 2022. Coffee Eco-Certification New Challenges for Farmers’ Welfare. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net › publication › 362685267. (11 September 2023). Research Gate.

Arifin, B. M. Reed, N. Rosanti, H. Ismono, and S. Budiyuwono. 2022. Partnership for Sustainable Coffee Certification: Linking Up Smallholder Farmers to Global Coffee Market. Sustainability Science and Resources. Peer-reviewed Journal, Vol. 2:3, 2022, pp. 24-44. Indonesian Forestry Certification Cooperation (IFCC) in collaboration with Millennium Resource Alternatives (MRA) LLC and Sustainable Development Indonesia (SDI). Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Statistik Kopi Indonesia 2021(Indonesia Coffee Statistics 2021). Biro Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta

BPS. 2022. Survei Angkatan Kerja Nasiona (National Labor Force Survey). Biro Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

CGRI. 2018. Kopi Indonesia. (Indonesian Coffee). Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia in the United States. Chicago.

Comunicaffe.com. 2016. Brazilian Coffee: A History of Success and Innovation. Retrieved from: https://www.comunicaffe.com/brazilian-coffee-a-history-of-success-and-in... (29 August 2023). Brazil.

DGEC. 2022. Statistik Perkebunan Unggulan Nasional 2020-2022 (National Leading Plantation Statistics 2020-2022).. Directorate General of Estate Crops. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGIP. 2023. Listing E-Indikasi Geografis (E-Listing of Geographical Indications). Directorate General of Intellectual Property. Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta.

Hayes, A. and D. Setyonaluri. 2015. Taking Advantage of the Demographic Dividend in Indonesia: A Brief Introduction to Theory and Practice. Policy Memo April 2015. The United Nations Population Fund-Indonesia. Jakarta.

Ibnu, M. 2017. Gatekeepers of sustainability: on coffee smallholders, standards and certifications in Indonesia. Retrieved from: https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/16087033/c5768.pdf (11 September 2023). Doctoral Thesis. Maastricht University. The Netherlands.

ICADIS. 2022a. Outlook Komoditas Perkebunan Kopi (Coffee Plantation Commodity Outlook). Indonesian Center for Agricultural Data and Information System. Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

ICADIS. 2022b. Analisis Kesejahteraan Petani Tahun 2022 (Analysis of Farmer Welfare in 2022). Indonesian Center for Agricultural Data and Information System. Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

ICCRI. 2019. Puslit Koka. 2019. Katalog Produk dan Jasa Unggulan (Featured Products and Services Catalog). Indonesian Coffee and Cocoa Research t Coffee per Person. World Population Review. California

ICO. 2022. World Coffee Consumption. International Coffee Organization. London.

IMoLHR. 2019. Peraturan Menteri Hukum dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 tahun 2019 tentang Indikasi Geografis (Regulation of the Minister of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia Number 12/2019 concerning Geographical Indications). Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta

Jakarta Post. 2021. Building the Golden Generation: How Yayasan Anak Bangsa Bisa Empowers Indonesian Talent. Retrieved from: https://www.thejakartapost.com/adv-longform/2021/10/08/building-the-gold... (10 October 2023). Jakarta Post Newspaper. 8 October 2021. Jakarta.

Kamwilu, E., Minang, P. A., Tanui J., Hoan D. T. 2021. Vietnam’s Coffee Story: Lessons for African Countries. World Agroforestry (ICRAF). Nairobi.

Krisnamurthi, B. 2020. Pengertian Agribusnis (Seri Memahami Agribisnis). Understanding Agribusiness (Understanding Agribusiness Series). Agribusiness Department. Faculty of Economics and Management. Bogor Agricultural University. Bogor.

Wahyudi, T. and M. Jati. 2012. Challenges of Sustainable Coffee Certification in Indonesia. Paper presented at Seminar on the Economic, Social and Environmental Impact of Certification on the Coffee Supply Chain, 109th Session, 25th September 2012. International Coffee Council. London.

WPR. 2023. Top 10 Countries that Drink the Most Coffee per Person. World Population Review. California.

[1] The demographic dividend refers to the accelerated economic growth that begins with changes in the age structure of a country’s population as it transitions from high to low birth and death rates. Indonesia will get a demographic dividend, namely the age of the workforce (15-64 years) reaches around 70%, while 30% of the population is unproductive (below 14 and over 65 years old). There is a need to improve the quality of national human resources to welcome the peak of Indonesia’s demographic dividend, wherein residents of the productive age group constitute the majority of the population, projected from 2030 to 2035 (Hayes and Setyonaluri, 2015; and ANA, 2023).

[2] Indonesia aims to become a developed country and the 5th largest economy by the time the celebrations come at the 100th year of independence in 2045 so called “Golden Indonesia”. By that time, the country’s population is expected to be more than 300 million, while its per capita income is expected to reach US$ 23,000 (Jakarta Post, 2021).

Accelerating Coffee Productivity through Farm, Farmers, and Agribusiness Developments in Indonesia

ABSTRACT

Coffee plays an important role in the economic activities of Indonesia. Even though the country is ranked as the fourth largest coffee exporter in the world after Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia, the productivity of Indonesian coffee is lower than its potential productivity. Therefore, there is a need to accelerate the Indonesian coffee productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness developments. It can be implemented by employing certification farms, encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, and expanding the geographical indications. The following actions are recommended. First, establish a clear legal framework with written codes of conduct and other necessary consensus provisions that benefit both smallholders and global coffee corporations. Second, facilitate networking opportunities for young farmers to connect with experienced coffee growers, industry experts, and other stakeholders through encouraging mentorship programs where experienced farmers mentor and guide young farmers. Third, set up careful planning, collaboration, and a commitment to preserving the unique qualities and cultural heritage of each coffee-producing region toward increasing the recognition and value of Indonesian coffee in both domestic and international markets.

Keywords: coffee, productivity, farm, farmer, agribusiness, development, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

The plantation is the first sub-sector that contributes around 3.94% to the agricultural gross domestic product (GDP) of Indonesia. This sub-sector provides raw materials for industry, absorbs labor, and earns foreign exchange for the country (BPS, 2021). As one of the plantation commodities, coffee plays an important role in the economic activities of Indonesia. This commodity has a total export value of US$822 million, after palm oil (US$19,712 million), rubber (US$3,247 million), cocoa (US$1,244 million), and coconut (US$1,172 million). Indonesia is also listed as the fourth largest coffee exporter in the world with a share of around 4.80%, after Brazil (25.81%), Vietnam (19.33%), and Colombia (9.41%).

The productivity of Indonesian coffee has only reached 0.81 tons per hectare; which is still lower than its potential productivity i.e. three tons per hectare (ICCRI, 2019). There is an imbalance between the growth of national coffee consumption and the level of coffee production. Many issues and challenges affect coffee productivity; the key issues are the poor quality of human resources and ineffective government policy strategy (Effendi et al., 2019). Therefore, the acceleration of coffee productivity is essential. It is expected to be able to improve the welfare of the community by employing people in the central coffee-producing areas through improving capacity to compete in the international coffee market. Hence, this paper discusses the acceleration of productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness development based on the overview of coffee in Indonesia.

INDONESIAN COFFEE OVERVIEW

Coffee plants were first cultivated in Indonesia around 3-4 centuries ago. In general, Indonesian coffee consists of four types, namely Arabica (Coffea arabica), Robusta (Coffea canephora), Liberika (Coffea liberica), and Ekselsa (Coffea exelsa). However, the types that are most widely cultivated are Robusta and Arabica with a proportion of around 77.18% and 22.82%, respectively (ICADIS, 2022). Coffee is cultivated throughout the country in certain central region producing areas with their specific types. The geographical location of the origin of each coffee gives uniqueness and differences in the sensory characteristics produced. Table 1 shows the regional types of coffees in Indonesia. Most of the coffee plantations are managed by smallholder plantations (98.14%), the rest by large state plantations (1.11%) and large private plantations (0.75%).

Coffee can be grown in all areas of Indonesia. However, coffee plantations are predominantly found in the Sumatra region i.e., Aceh, North Sumatra, Bengkulu, South Sumatra, and Lampung provinces. This region contributes about 73% to the total area and production of central coffee-producing areas of the country. Figure 1 shows the map of the top ten central coffee-producing provinces in Indonesia. It contributes about 77% to the total area and production of coffee in Indonesia. The highest is South Sumatra province with a total area of 250,305 hectares and production of 198,945 tons, while the lowest is West Java province with a total area of 47,757 hectares and production of 22,980 tons.

The coffee plantation area in Indonesia is recorded at 1,250,452 hectares with a total of 1,634,914 household farmers (DGEC 2022). The performance of Indonesian coffee over the last five years (2016-2020) has shown quite positive. The area has slightly grown by 0.01% per year, production at 3.57% per year, and productivity at 3.91% per year (Table 2). Indonesia is the second largest coffee area in the world after Brazil (1,837,302 hectares). However, the national coffee production (773,409 tons) is still below the world’s main major producing countries such as Brazil (3,194,736 tons), Vietnam (1,613,949 tons), and Colombia (833,400 tons).

The average productivity of Indonesian coffee is around 585 kg/ha. Indonesia is ranked 37th in the world or far below China with productivity reaching 30,055 kg/ha or lower than other ASEAN countries such as Malaysia 29,399 kg/ha and Vietnam 26,147 kg/ha (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the average Indonesian coffee consumption is recorded at around 0.88 kg/ha/year (WPR, 2023) or far below consumption in several European countries (8.60 kg/capita/year). Other data sources (ICO, 2022) show that Indonesia ranks 5th in the world with a total coffee consumption of 300 tons per year, below the European Union (2,415 tons/year), the United States (1,619 tons/year), Brazil (1,344 tons/year), and Japan (443 tons/year).

It is noted that accelerating coffee productivity is also expected to fulfill the domestic consumption trend of coffee in Indonesia. Currently, coffee is available everywhere created by baristas which are spread across several coffee shops. However, it needs to be emphasized that the raw materials must come from domestic sources, without relying on imports. It is just a precaution so that coffee consumers’ tastes do not choose imported coffee towards appreciating domestic products (love of the homeland) because Indonesian coffee production is still abundant (annual production and consumption are 793,193 tons and 379,655 tons, respectively). The country only imports coffee by about 4.42% (ICADIS, 2022a).

ACCELERATION OF COFFEE PRODUCTIVITY

Farms

Currently, some coffee plants are classified as unproductive because they are already in the old and damaged category, which is around 10.45% of the total plantation area in Indonesia. Even though there has been a decrease in the proportion of old and damaged plants by around 4.51% per year over the last five years (2016-2020), the existence of productive plants is relatively not optimal in replacing the presence of these old and damaged plants. The contribution of productive plants is around 75.06% with quite low growth i.e., 0.28% per year. Meanwhile, the existence of immature plants which are expected to support the existence of mature plants and replace old and damaged plants, the contribution is quite good, namely around 14.48% with a growth of 2.58% per year. However, the maintenance of these immature plantations and those that are already considered productive needs to be carried out seriously and sustainably.

Accelerating coffee productivity can be carried out in a planned manner so as not to disrupt its supply and interests of farmers’ livelihoods. One of the strategic options is the implementation of replanting coffee for smallholders by replacing non-productive plants with the introduction of superior seed varieties. Several superior seed varieties are available as presented in Table 3.

It is challenging to encourage smallholders to be involved in the replanting through the introduction of superior coffee seeds, especially for those who much depend their livelihood on coffee farms. This should be followed by implementing certification program.

Indonesia has implemented certain coffee certifications including Utz-Kapeh, Organic such as Japan Agricultural Standard (JAS), European Union (EU), and United States Department of Agriculture/National Organic Program (USDA/NOP), Common Code for the Coffee Community (4C), Indonesian Sustainable Coffee (ISCo) Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP), Rainforest Alliance, and Fair Trade. These certification programs require the fulfillment of defined indicators covering social, environmental, and economic sustainability, and product traceability. Nevertheless, coffee producers give various responses including the confusion at the farmer level and certification fees issue. Direct contact between buyer and producer by ignoring middlemen also provides a case sensitive in implementing the certification programs (Wahyudi and Jati, 2012).

Another noticeable certification is the eco-certification scheme. This certification scheme in the coffee sector emerged during the early 1990s in conjunction with rising concerns about the environment and developed rapidly in this century. The scheme is aimed at promoting environmentally friendly and sustainable coffee production practices. It is typically designed to ensure that coffee is grown and processed in a way that minimizes harm to the environment, protects the rights and well-being of coffee farmers and workers, and produces high-quality coffee beans. Three studies related to the implementation of eco-certification schemes are discussed below.

Based on the aforementioned discussions, we underline that the implementation of coffee certification in Indonesia has a range of challenges and opportunities (Table 4). It is believed that the coffee industry is dynamic, and conditions may have evolved since then.

Farmers

The performance of coffee farmers is linearly related to their characteristics. In other words, the rise and fall of coffee farming is largely determined by the existence management of the human resources (farmers). Currently there are 38.70 million Indonesian farmers, of which around 67.20% are classified as productive farmers (BPS, 2022).

In general, Indonesian farmers can be divided into two productive groups based on age, namely: (1) Young farmers (age 19-39 years); and (2) Old farmers (age 40-60 years). Currently, coffee farming is mostly carried out by older farmers. Table 5 indicates that the composition of old farmers is higher than that of young farmers i.e., 59.57% vs. 40.43%). During the last five years (2018-2022), the number of young farmers has decreased by around 0.79% per year and conversely the number of old farmers has increased by approximately 2.31% per year (Table 5).

The discrepancy in the composition of the number of young and old farmers should be a concerned. There are at least two characteristics that are embedded in old farmers. First, old farmers have less optimal outpouring of energy due to a decrease in work productivity. Second, old farmers have low quality of farming practices due to stuttering about technology. In addition, the educational level of Indonesian farmers is classified as low educated, namely around 30-40% have only completed elementary school (SD) and 39% have not attended school/have not completed elementary school (ICADIS, 2022b).

All of the factors above can become obstacles in efforts to accelerate the increase in farming productivity (including coffee) which in fact requires productive farmers’ requirements related to the application of technology. One of them is the application of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) for coffee farming (Table 6).

The above guidelines (Table 6) are basic. In other words, the content is dynamic according to technological developments and needs. But implicitly its application requires progressive farmers from relatively young ages. This has recently become a phenomenon since many young farmers are reluctant to get involved in agriculture.

It can be said that the regeneration of farmers has been slow in Indonesia due to the reluctance of the younger generation and some parents’ objections to their children working in agriculture. This relates to subjective perceptions (stereotypes) towards the existence of agricultural employment. The younger generation often views agriculture as an unpopular career path and has many drawbacks (low financial returns), synonymous with poverty, low prestige, and no chance of success in the future. Meanwhile, they prefer job choices with high mobility and more promising prospects.

The perceptions of the younger generation which tend to lead to doubt (skepticism) and could form negative perceptions of agriculture which are not easy to overcome. Especially if it is combined with the assumption that farming is synonymous with poverty, low education, and dirty work that relies more on physical ability rather than intelligence. This should be addressed wisely while motivating the younger generation to build a positive perception of the agricultural sector so that they can overcome stereotypes that encourage identity gaps.

With such a large population, Indonesia has the opportunity to be more advanced regarding the availability of production labor resources and consumption markets. One opportunity that can be explored is increasing the nation’s productivity, especially from human resources of productive age (demographic dividend) which is currently in sight[1]. However, it needs to be emphasized that the demographic dividend can be an advantage (window of opportunity) and conversely, it can also bring losses (window of disaster). It depends on how it is managed because the demographic dividend must not only be filled with human resources in terms of quantity but also being prepared with human resources in terms of quality. Good management of the demographic dividend will produce quality human resources, or in other words, increase the Human Development Index (HDI). Therefore, optimizing the management of the demographic dividend to increase the HDI is an absolute necessity that must be implemented in a planned, measurable, and sustainable manner.

The involvement of the younger generation is essential in accelerating Indonesian coffee productivity, especially in the context of welcoming Golden Indonesia 2045 which really hopes for the participation of the younger generation to fill it[2]. Do not let the bird in your hands fly away without knowing the jungle. So, it must be tied adaptively and flexibly.

Agribusiness

Agribusiness has a much wider scope of understanding than just the notion of farming or primary agriculture (Krisnamurthi, 2020). It comprises a series of systems that cover several upstream, on-farms, downstream, and support services sub-systems. In this case, the paper focuses on the agribusiness subsystem of supporting services, mainly more specifically related to aspects of coffee geographical indications.

The geographical indications indicate the area of origin of goods and products according to geographical and environmental factors (including natural factors, human factors, or a combination of both) which give reputation, quality, and certain characteristics to the goods and products produced. This is an exclusive right that is granted to holders of registered geographical indications, that is, as long as the reputation, quality, and characteristics that serve as the basis for the protection of geographical indications still exist (MoLHR, 2019).

Several types of coffee have been listed in geographical indications (Table 7). There is an opportunity to register several other specific types of coffee in Indonesia, where agribusiness engineering related to this geographical indication is important in accelerating Indonesian coffee productivity. However, it should be noted that its implementation cannot be separated from the introduction of superior varieties that comply with geographical indication requirements, application of agricultural precision, consumption campaigns, provision of incentives for the domestic market, and increased export promotion. This must be in line with development policies including protecting national production, securing the domestic market, increasing quality requirements, formulating prices, and strengthening farmer institutions to achieve an efficient and effective coffee development program both domestically and internationally.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Accelerating coffee productivity through farm, farmer, and agribusiness development is strategically implemented in Indonesia. It can be implemented by employing certification farms, encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, and expanding the geographical indications.

Indonesia is a huge country with different geographical landscapes and human resource characteristics. Therefore, it is important to recognize that while coffee certification can bring numerous benefits, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Different certification programs have varying requirements and focus areas, and their success depends on factors such as the commitment of farmers, access to resources, and the effectiveness of support systems in place. It is recommended to establish a clear legal framework with written codes of conduct and other necessary consensus provisions that benefit both smallholders and global coffee corporations. It should be noted that the complexity of partnership rules, contracts, and regulations might be quite specific by crop, geographic characteristics, and value systems among smallholders and global corporations. Hence, it may be interesting to further investigate farmer’s ideas and preferences for price premium alternatives.

Encouraging human resources, especially young farmers, in coffee farms is essential for the sustainability and growth of the coffee industry in Indonesia. It requires a multi-faceted approach involving government, industry stakeholders, and the community. By addressing education, finance, market access, and sustainability, it can create an environment where young people are motivated to pursue a career in coffee farming and contribute to the industry's growth and development. It is recommended to facilitate networking opportunities for young farmers to connect with experienced coffee growers, industry experts, and other stakeholders. At the same time, encourage mentorship programs where experienced farmers mentor and guide young farmers.

Expanding the geographical indications of Indonesian coffee farms can help protect and promote the unique qualities and origins of coffee produced in different regions of the country. There is a need to identify suitable regions, accomplish public awareness and promotion, employ traceability and labeling, develop quality standards, and improve the effectiveness of geographical indications continuously. It is recommended to set up careful planning, collaboration, and a commitment to preserving the unique qualities and cultural heritage of each coffee-producing region toward increasing the recognition and value of Indonesian coffee in both domestic and international markets.

REFERENCES

ANA. 2023. Government prepares strategic measures to welcome demographic dividend. Antara News Agency. Jakarta.

Andoko, E., Zmudczynska, E., and Wan Yu Liu, W. Y. 2020. A Strategy Review of the Coffee Policies and Development by the Indonesian Government. Retrieved from: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1874 (5 September 2023). Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region (FFTC-AP). Taipei.

Arifin, B. 2022. Coffee Eco-Certification New Challenges for Farmers’ Welfare. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net › publication › 362685267. (11 September 2023). Research Gate.

Arifin, B. M. Reed, N. Rosanti, H. Ismono, and S. Budiyuwono. 2022. Partnership for Sustainable Coffee Certification: Linking Up Smallholder Farmers to Global Coffee Market. Sustainability Science and Resources. Peer-reviewed Journal, Vol. 2:3, 2022, pp. 24-44. Indonesian Forestry Certification Cooperation (IFCC) in collaboration with Millennium Resource Alternatives (MRA) LLC and Sustainable Development Indonesia (SDI). Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Statistik Kopi Indonesia 2021(Indonesia Coffee Statistics 2021). Biro Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta

BPS. 2022. Survei Angkatan Kerja Nasiona (National Labor Force Survey). Biro Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

CGRI. 2018. Kopi Indonesia. (Indonesian Coffee). Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia in the United States. Chicago.

Comunicaffe.com. 2016. Brazilian Coffee: A History of Success and Innovation. Retrieved from: https://www.comunicaffe.com/brazilian-coffee-a-history-of-success-and-in... (29 August 2023). Brazil.

DGEC. 2022. Statistik Perkebunan Unggulan Nasional 2020-2022 (National Leading Plantation Statistics 2020-2022).. Directorate General of Estate Crops. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

DGIP. 2023. Listing E-Indikasi Geografis (E-Listing of Geographical Indications). Directorate General of Intellectual Property. Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta.

Hayes, A. and D. Setyonaluri. 2015. Taking Advantage of the Demographic Dividend in Indonesia: A Brief Introduction to Theory and Practice. Policy Memo April 2015. The United Nations Population Fund-Indonesia. Jakarta.

Ibnu, M. 2017. Gatekeepers of sustainability: on coffee smallholders, standards and certifications in Indonesia. Retrieved from: https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/16087033/c5768.pdf (11 September 2023). Doctoral Thesis. Maastricht University. The Netherlands.

ICADIS. 2022a. Outlook Komoditas Perkebunan Kopi (Coffee Plantation Commodity Outlook). Indonesian Center for Agricultural Data and Information System. Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

ICADIS. 2022b. Analisis Kesejahteraan Petani Tahun 2022 (Analysis of Farmer Welfare in 2022). Indonesian Center for Agricultural Data and Information System. Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

ICCRI. 2019. Puslit Koka. 2019. Katalog Produk dan Jasa Unggulan (Featured Products and Services Catalog). Indonesian Coffee and Cocoa Research t Coffee per Person. World Population Review. California

ICO. 2022. World Coffee Consumption. International Coffee Organization. London.

IMoLHR. 2019. Peraturan Menteri Hukum dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 tahun 2019 tentang Indikasi Geografis (Regulation of the Minister of Law and Human Rights of the Republic of Indonesia Number 12/2019 concerning Geographical Indications). Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta

Jakarta Post. 2021. Building the Golden Generation: How Yayasan Anak Bangsa Bisa Empowers Indonesian Talent. Retrieved from: https://www.thejakartapost.com/adv-longform/2021/10/08/building-the-gold... (10 October 2023). Jakarta Post Newspaper. 8 October 2021. Jakarta.

Kamwilu, E., Minang, P. A., Tanui J., Hoan D. T. 2021. Vietnam’s Coffee Story: Lessons for African Countries. World Agroforestry (ICRAF). Nairobi.

Krisnamurthi, B. 2020. Pengertian Agribusnis (Seri Memahami Agribisnis). Understanding Agribusiness (Understanding Agribusiness Series). Agribusiness Department. Faculty of Economics and Management. Bogor Agricultural University. Bogor.

Wahyudi, T. and M. Jati. 2012. Challenges of Sustainable Coffee Certification in Indonesia. Paper presented at Seminar on the Economic, Social and Environmental Impact of Certification on the Coffee Supply Chain, 109th Session, 25th September 2012. International Coffee Council. London.

WPR. 2023. Top 10 Countries that Drink the Most Coffee per Person. World Population Review. California.

[1] The demographic dividend refers to the accelerated economic growth that begins with changes in the age structure of a country’s population as it transitions from high to low birth and death rates. Indonesia will get a demographic dividend, namely the age of the workforce (15-64 years) reaches around 70%, while 30% of the population is unproductive (below 14 and over 65 years old). There is a need to improve the quality of national human resources to welcome the peak of Indonesia’s demographic dividend, wherein residents of the productive age group constitute the majority of the population, projected from 2030 to 2035 (Hayes and Setyonaluri, 2015; and ANA, 2023).

[2] Indonesia aims to become a developed country and the 5th largest economy by the time the celebrations come at the 100th year of independence in 2045 so called “Golden Indonesia”. By that time, the country’s population is expected to be more than 300 million, while its per capita income is expected to reach US$ 23,000 (Jakarta Post, 2021).