ABSTRACT

In Myanmar, vegetable production is a major component of food safety strategy. Cabbage is such a vegetable vastly attacked by various kinds of pests. Wide and unsystematic use of pesticides and thus their residues are the main challenge for food safety. Inadequate food safety knowledge of consumers leads to not just negative impact on food safety practice but also causes health problems and shorter life expectancy among them. This study explored the relationship among the selected socio-economic factors, food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of cabbage consumers in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, Myanmar. A well-structured questionnaire with closed ended format questions was used to collect the data from respondents (n=80) about socio economic factors and food safety KAP attributes step by- step starting from food handling situation till up to their practicing behavior. Their responses were analyzed using Chi-Square test and Pearson correlation analysis. The results revealed that the highest proportion of respondents was medium-knowledge-level consumers and there was a highly significant correlation among the food safety KAP. All in all, social and mass media contact was the most influencing factor on food safety knowledge (FSK) at p < 0.01. Education and different annual income levels were correlated with FSK at p < 0.05. And age and family size also had a relationship with FSK at P < 0.1.

Key Words: Food safety, agrochemical residue, knowledge, attitude, practice.

INTRODUCTION

Food safety emerges as an important issue in human society, with increased media attention (Frewer, Shepherd & Sparks, 1994), consumer studies (Miles et al. 2004), and the establishment of new regulatory bodies. Nowadays, food safety is one of the most important agenda for public health, and it will also affect the economy and development of a country. The chain of food safety starts from farm to factory to fork and covers a wide range of processes from producing, handling and storing to food preparation and consumption. Foodborne illnesses, injuries and allergic reactions are the main causes of food safety hazards (Huziej, 2021). Factors influencing food hazards are contamination of soil and water, unsafe working conditions, pesticide misuse and pesticide residues.

There are three types of food hazards – biological, chemical, and physical. Biological hazards are caused by bacteria, parasites, fungi and viruses. These organisms around us, in air, soil, water, animals and humans can easily contaminate our food throughout the whole food chain and can cause foodborne illnesses apart from some beneficial ones such as bacteria and yeast used as probiotics, and in dairy, bread, and alcohol production (Huziej, 2021). Moreover, rodents, flies and other insects in agriculture can also cause biological hazards as vectors. The consequence of biological hazards is foodborne illnesses commonly known as food poisoning. These serious problems are caused by eating microorganism-contaminated foods through poor hygiene, improper handling, storing, and cooking. General symptoms are diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, high temperature and stomach cramps, which can vary from person to person and it generally occurs in hours or weeks after eating unsafe food. In some cases, it can be life-threatening.

Chemical hazards are inclusion of harmful substances such as pesticides, machine oils, fungicides, plant growth regulators, preservatives and other agrochemical substances which are usually applied in agriculture and food production. The results of improper use of these are ecosystem degradations and residual problems in food. Chemical residues are harmful to human if the amount exceeds maximum residue level (MRL). Thus, the most developed countries have set various MRLs in international trade for agricultural products.

Physical hazards are objects which contaminate our foods, such as pieces of glass or metal, toothpicks, jewelry or hair (Food safety hazards and culprits, n.d.). This contamination can also occur due to poor food handling practices and can choke and injure the consumers (Physical hazards in food, n.d.). Therefore, implementation of Good Hygiene Practices (GHP) and Hazard Analysis of Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan is essential along food processing in order to control this type of hazards. Every year, approximately 2.2 million people, the majority of whom are children living in developing countries, die as a result of food and water contamination (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008). According to the estimation of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the U.S.A. , 48 million people get sick from a foodborne illness, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die yearly (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016). The mortality rate had declined during the last 12 years and the reason may be implementation of food safety programs in most of the country.

In developing countries, nearly 75% of the 200,000 deaths were associated with pesticide poisoning even though they used only 15% of global pesticide supply (- Koul et al., 2004 2008 2011). In Myanmar as well as in some developing countries, food is a strategic product that helps increase the growth of economy and politics (Food safety hygiene, n.d.). Myanmar has a poor track record of preventing foodborne illnesses, plagued by low public awareness and weak adoption of food safety practices among producers, processors, distributors and consumers (Aung, 2019).

According to the global food security index of 2021, Myanmar ranked 72 in the area of food safety among 113 countries (Food security index, 2021). This position is very low compared to other Southeast Asian neighboring countries like Thailand (51) and Malaysia (39) and so on. Particularly, as food is one of the main media of virus dispersion, consumers in Myanmar are continuously faced with challenges of food safety.

Vegetables are the second most important food for daily consumption of Myanmar citizens after rice. To produce vegetables successfully, it requires proper use of all available resources especially in developing countries (Singh, Barman & Varshney, 2016). Normally vegetables are consumed as raw or semi processed forms, hence may hold on elevated amount of pesticide residues as compared to other foods including cereals and The problem of contamination of food sources, especially vegetables with pesticide residues constitutes to be one of the most serious challenges to public health.

Among vegetables, c (Brassica oleracea) is one of the most consumed vegetables in Myanmar. Myanmar people are using cabbage in various eating styles including fried cabbage or use it as an ingredient in some dishes and mostly they consume fresh cabbage in various salads like pickled tea salad. As insects and fungi are the main barriers in cabbage production, insecticides and fungicides have become the main chemical pesticides which are intensively used to suppress these problems like diamondback moth (DBM) and others. Furthermore, the effect of pesticide residues can be toxic to humans along the food chain and dispersed into the environment for the longest time. In Myanmar, 37 food poisoning cases occurred, which affected 1,320 people causing one death. And 17 diarrheal cases affected 567 people, leading to 11 , between 2017 and 2018, several studies have indicated the inadequate food safety standards. A research team of the Department of Medical Research tested 84 BBQ fish vendors in Yangon Region and found 27% of the fish contained the Vibrio bacteria. Another study by the regional government in Yangon showed that 93.5% of bean curds sold in the markets were laced with formalin. Another case displayed the poor safety concerns at factories, where one child died of lead poisoning and 15 other children were hospitalized in Hmawbi Township in Yangon. And a small-scale research executed in the Inle Lake region at the beginning of 2018 discovered that 75% of the vegetable samples from both villages and markets had pesticide residues exceeding the maximum residue limits. Food safety has not only serious impacts on the well-being of Myanmar citizens but also influences tourism, economy and the development of the objectives of this study are as follows:

- To assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food safety of cabbage consumers; and

- To analyze the relationship among the food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of cabbage consumers and their socio-economic factors.

RESEARCH METHODS

Study design and sampling

This study was carried out between April and May, 2022 in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, the new administrative capital city of Myanmar, and its estimated total population is 1,160,242. Zayar Thiri and Pobba Thiri Townships were purposively selected as study areas under the reason of very limited food safety research there. The majority of the respondents were female. All of them were cabbage consumers and the main persons who managed and prepared food for their families.

Data collection and questionnaire design

Concerning with primary data collection, the households were visited to explain the purpose of the study, and requested to participate voluntarily. The research was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire and all the questions were in Myanmar language for the convenience of respondents and it took about 15 minutes to answer the questionnaire. After getting agreement from participants to be involved in the study, the questionnaires were left with them and were collected after a couple of days. There were three main parts in the questionnaire. In the first part, the socio-economic information of the respondents such as age, gender, family size, education level, occupation, annual income, social and mass media exposure were asked. The second part had been designed to acquire the information about food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices on food handling, preparing, and storing in general. In the last part, general information consisted of consumer behavior for cabbage purchasing concerning with food safety. So as to transform the qualitative data into quantitative, all the questions with dichotomous and multichotomous format were coded into score of either ‘0’ or ‘1’. Five points Likert scale method was used and the answers were coded into Strongly Agree=5, Agree=4, Undecided=3, Disagree=2, Strongly Disagree=1 for positive statement questions but for negative statements the scores were the reverse ( Savitha, 1999).

Statistical analysis

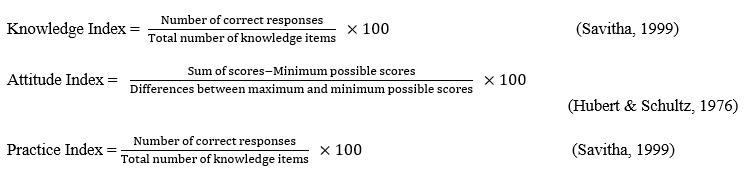

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS statistical package (version 23). Descriptive statistics were used and three levels of categorization methods – low (Mean-SD and below), medium (Mean + SD) and high (Mean + SD and above) – were provided for all data (Savitha, 1999). The scores of raw food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice of each individual respondent were converted into index values by using the following formulas:

To evaluate the association and correlations among socio-economic factors, food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) traits, Chi-Square test and Pearson correlation test were used in this study. As for P- value, < 0.1 (statistical significance), < 0.05 (statistical significance), and < 0.01 (statistical highly significance) were considered respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of food safety for cabbage consumers

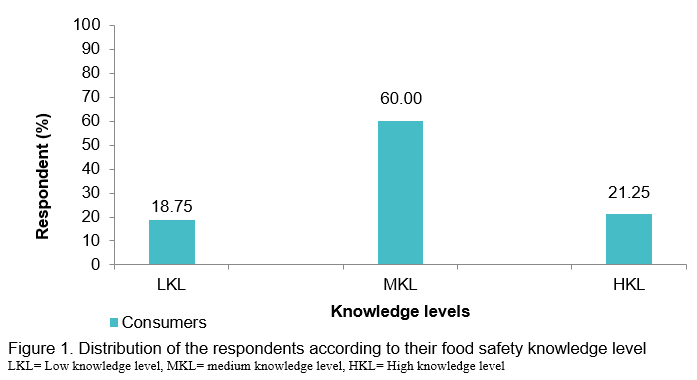

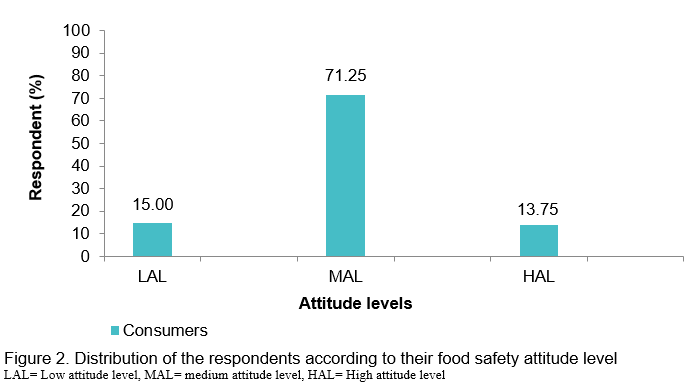

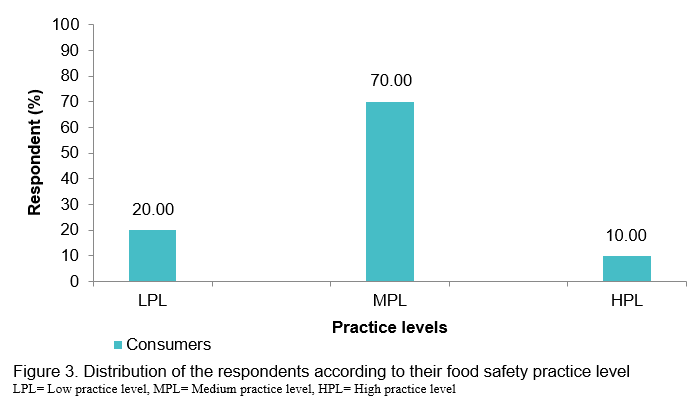

As for consumers’ food safety (KAP) attributes, only 21.25% of the respondents fell in food safety high knowledge level group, whilst over 13% of the respondents were in high attitude level group, but in high practice level group, there were just 10% of the respondents. Among food safety KAP attributes, the trend was downward and the result revealed that they did not follow food safety rules and regulations, though their food safety knowledge was high. Detailed data were indicated in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

There were some indications of low knowledge level such as big-sized cabbages were free from insect boreholes and should be selected. Such cabbages might come out as the result of heavy agrochemical application. And they thought the same chopping board could be used to cut meat as well as vegetable without cleaning it with soap and consuming the fresh cabbage did not affect the health of consumers. They did not have the knowledge of correct hand washing and about systematical storage of prepared food. The reasons for low attitude level were they did not agree that prepared food should be kept at a safe temperature but agreed hole-free cabbage should be selected for their safety. The reasons for low practice level were that they were not interested in GAP crops, not familiar with using hand gloves and apron when they prepared food, always purchased hole-free cabbage, used to eating the fresh cabbage without giving some treatment, and never kept prepared food at safe temperature.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS AND FOOD SAFETY KNOWLEDGE LEVEL OF CABBAGE CONSUMERS

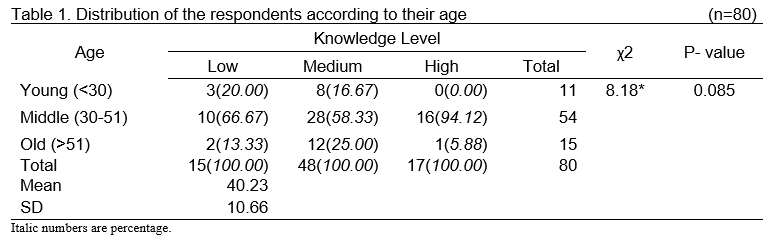

Association of age and FSK

Age is an important factor as aging may bring positive cognitive changes. The association between food safety knowledge and age of respondents was shown in Table 1. In the low knowledge group, the majority of the respondents (66.67%) were in middle age. The rest of the respondents were young and old, with 20.00% and 13.33%, respectively. In the medium knowledge level group, the percentage of middle age respondents (58.33%) was considerably higher than the other two groups as described in Table 1. In the high knowledge level group, there was no young respondent at all but the overwhelming majority of middle age respondents were amounting to 94.12%. A modest proportion of old respondents (5.88%) also were involved. According to the Chi-Square test, different age levels of respondents were significantly associated with the knowledge groups at p < 0.1.

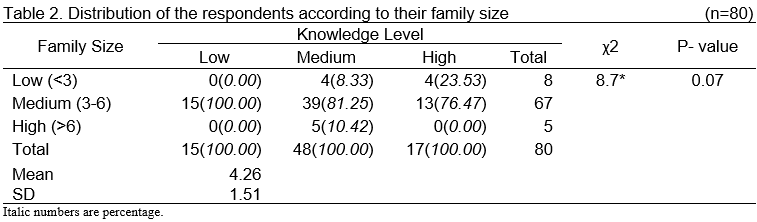

Association of family size and FSK

Family size determines knowledge level based on family members’ experiences and knowledge sharing behavior. The association between food safety knowledge and family size was depicted in Table 2. In low knowledge level group, all of the respondents (100%) possessed medium family size. Likewise, in medium knowledge level group, a massive 81.25% of respondents occupied medium family size, followed by high family size with (10.42%), and low family size (8.33%) of respondents. In high knowledge level group, most respondents (76.47%) had medium family size but the rest of the respondents (23.53%) had low family size. The result of Chi-Square test analysis indicated that respondents’ family size level had a statistically significant association with various knowledge level groups at p < 0.1. This may be reasonable because idea innovation, sharing news and information in issues like food safety among family members will lead to the knowledge development of the family. So, there is no doubt that family size may be a catalytic agent to acquire update knowledge.

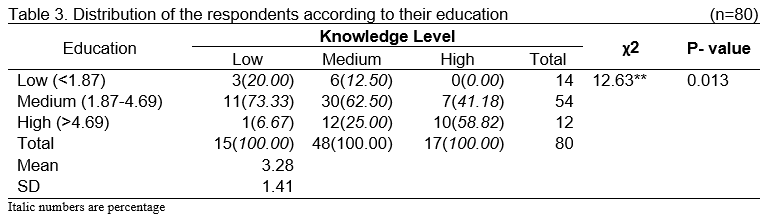

Association of education and FSK

Education level is a key determinant of knowledge, as well as attitude and practices (Fredi Alexander Diaz-Quijano et al., 2018). In low knowledge level group, the highest percentage of respondents had medium education level, contributing to 73.33%. This was followed by the respondents in low education level (20.00%) and the respondents in high education level (6.67%). In medium knowledge level group, the number of respondents in medium education level was higher than the other two education level groups (low and high), with 62.50% as opposed to 12.50% and 25.00%. In high knowledge level group, no one was low in education level and nearly half of the respondents (41.18%) had medium education level, and the other respondents (58.82%) had high education level. Additionally, there was a significant relationship between education levels and knowledge levels in Chi-Square analysis at p < 0.05, as highlighted in Table 3. As education focuses on developing critical thinking and problem solving skills of individuals, the illiterate person cannot be compared with the one who has high education level in acquisition of knowledge due to so many barriers.

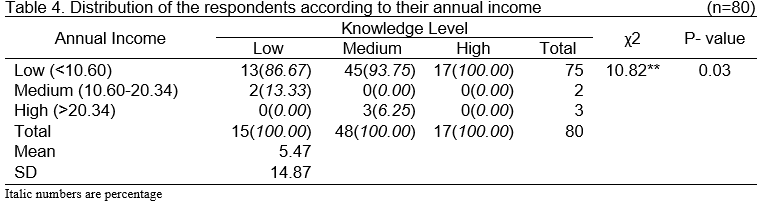

Association of annual income and FSK

Annual income is a powerful factor to acquire food safety knowledge from different sources. In low knowledge level group, most of the respondents came from low income groups as compared to the medium income level group, 86.67% as opposed to 13.33%. In medium knowledge level group, the greatest percentage of respondents (93.75%) was in low annual income group, whereas a mere 6.25% of respondents were in high income group. In high knowledge group, approximately 100.00% of respondents were in low income level group. Chi-Square test result pointed out that there was a statistically significant relationship among these two variables at p < 0.05, as shown in Table 4. For instance, low income households cannot be interested in other matters except for their basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. For high income households, they have many choices for life, willingness to pay for quality products, and they will learn everything in specific to get better life.

Association of social and mass media contact and FSK

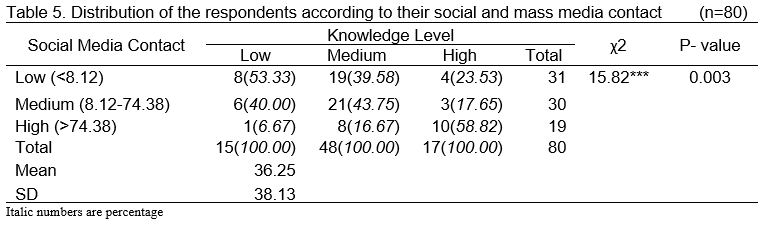

The role of social and mass media is important in upgrading and development of knowledge. Concerning the association among the social and mass media contact and food safety knowledge levels, in low knowledge level group, just over half of the respondents (53.33%) were low in social and mass media exposure and only 6.67% of respondents had high level exposure with social and mass media. Another 40.00% respondents were in medium exposure group to those. In medium knowledge level, low exposure level of respondents with social and mass media was twice as many as high level, with 39.58% in contrast to 16.67%. In high knowledge level group, just over half of the respondents (58.82%) had high social and mass media exposure, after which 23.53% of the respondents had low level in those and 17.65% of respondents had medium exposure, as highlighted in Table 5. Chi-Square test analysis indicated that the relationship among the different two variables was found to be statistically highly significant at p < 0.01. The possible reason may be being more exposed to social and mass media can be knowledgeable about something like COVID-19 crisis, political and health affairs, and food safety issues.

Correlation analysis among food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of cabbage consumers

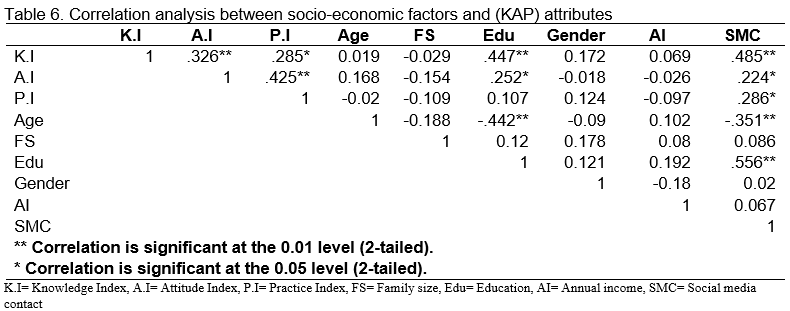

The KAP scores were continuous and normally distributed, thus, Pearson correlation test was conducted so as to analyze the nature of relationship between the selected socio-economic factors and food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The correlation coefficients (r) values were presented in Table 6.

The results of correlation test described that age had non-significant relationship with food safety KAP attributes, which meant being younger or older did not influence food safety KAP attributes. In the finding of Ahmed, Akbar & Sadiq, 2021, KAP attributes of food handlers in Pakistan were assessed that age had no significant association with food safety knowledge and attitude but age had a significant association with practice.

There was no relationship between family size and food safety KAP attributes. Similarly, gender did not have any relationship with those. This current finding was in line with a study in Canada, which showed no association between FSK attribute of food handlers and gender (McIntyre et al., 2013).

The relationship between education and food safety knowledge and attitude had a statistically significant relationship at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 respectively, but it had no relationship with practice. This finding was in agreement with the former studies that pointed out education level was significantly associated with food safety knowledge (Rahman et al., 2014 2016 2020). But in some different countries, some studies evaluated that there was no relationship between education level and food safety KAP attributes (Choudhury et al., 2011). Thus, to be clearer in that situation, further studies dealing with food safety should be carried out according to the specific areas of the country.

Social and mass media contact was found a positive and significant relationship with food safety KAP attributes, at p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05 respectively. Keeping in touch with social and mass media might support knowledge improvement because most knowledge came from daily exposure with our environment and modernized applications.

The relationship among food safety KAP attributes had highly significant correlation. That means these attributes had been influenced by each other.

CONCLUSION

Taking everything into consideration, this current study found that just over one in five of the cabbage consumers had high food safety knowledge level, over 13% had high food safety attitude level, and there were only 10% who followed food safety standards in reality. These data were evidence of how much they care about food safety. As cancer cases have gradually increased due to unsafe foods, higher medical cost has become an additional problem for poor and middle income households. Therefore, some solutions should be taken. In the consumers’ perspective, they also had responsibility for their own food safety by following safety standards such as purchasing commodities with the minimum chemical residue like GAP crop, and avoiding food products with preservatives (food dyes, formalin, etc.). No product can stand long in the market without consumers’ demand. Furthermore, proper food preparing practices should be followed including use of hand gloves and apron, proper storage, and proper treatment should be taken for vegetables and other food products. In the authorities’ concerns, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must restrict food sellers in market with some effective food safety rules and regulations, particularly in COVID-19 pandemic. Regular inspection for pesticide residues on food products and products’ quality in market should be taken in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation (MOALI). And more regional food safety education programs should be conducted. Activation of food safety law, regulation, GDP and living standard of a country are the determinants of food safety status of a country.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, M. H., Akbar, A., & Sadiq, M. B. (2021). Cross sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers in Lahore district, Pakistan. Heliyon, 7(11), e08420.

Armah, F. A. (2011). Assessment of pesticide residues in vegetables at the farm gate: Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) cultivation in Cape Coast, Ghana. Research Journal of Environmental Toxicology, 5(3), 180-202.

Aung, S. Y. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.irrawaddy.com/in-person/getting-serious-food-safety-myanmar....

Cenral Epidermiology Unit, Myanmar. Annual Health Report. Department of Public Health. 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Foodborne germs and illnesses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www. cdc. gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs. html.

Chan, A. (2018). Food Safety as a Challenge for Myanmar. Retrieved from https://www. myanmarinsider.com.

Choudhury, M., Mahanta, L., Goswami, J., Mazumder, M., & Pegoo, B. (2011). Socio-economic profile and food safety knowledge and practice of street food vendors in the city of Guwahati, Assam, India. Food Control, 22(2), 196-203.

Claeys, W. L., Schmit, J. F., Bragard, C., Maghuin-Rogister, G., Pussemier, L., & Schiffers, B. (2011). Exposure of several Belgian consumer groups to pesticide residues through fresh fruit and vegetable consumption. Food control, 22(3-4), 508-516.

Darko, G., & Akoto, O. (2008). Dietary intake of organophosphorus pesticide residues through vegetables from Kumasi, Ghana. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 46(12), 3703-3706.

Diaz-Quijano, F. A., Martínez-Vega, R. A., Rodriguez-Morales, A. J., Rojas-Calero, R. A., Luna-González, M. L., & Díaz-Quijano, R. G. (2018). Association between the level of education and knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue in the Caribbean region of Colombia. BMC public health, 18(1), 1-10.

Frewer, L. J., Shepherd, R., & Sparks, P. (1994). The interrelationship between perceived knowledge, control and risk associated with a range of food‐related hazards targeted at the individual, other people and society. Journal of food safety, 14(1), 19-40.

Htway, T. A. S., & Kallawicha, K. (2020). Factors associated with food safety knowledge and practice among street food vendors in Taunggyi Township, Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine, 20(3), 180-188.

Hubert, L., & Schultz, J. (1976). Quadratic assignment as a general data analysis strategy. British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology, 29(2), 190-241.

Huziej, M. (2021). What are the hazards in the food industry?

Koul, O., Dhaliwal, G. S., & Cuperus, G. W. (2004). Integrated pest management potential, constraints and challenges. CABI.

Liu, Z., Zhang, G., & Zhang, X. (2014). Urban street foods in Shijiazhuang city, China: Current status, safety practices and risk mitigating strategies. Food Control, 41, 212-218.

McIntyre, L., Vallaster, L., Wilcott, L., Henderson, S. B., & Kosatsky, T. (2013). Evaluation of food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported hand washing practices in FOODSAFE trained and untrained food handlers in British Columbia, Canada. Food Control, 30(1), 150-156.

Miles, S., Brennan, M., Kuznesof, S., Ness, M., Ritson, C., & Frewer, L. J. (2004). Public worry about specific food safety issues. British Food Journal, 106(1), 9–22.

Physical hazards in food. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.statefoodsafety.com/Resources/ Resources/naturally-occurring-physical-hazards-in-food

Quijano, F. A. D et al., 2018. Association between the level of education and knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue in the Caribbean region of Colombia. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 143.

Rahman, M. M., Arif, M. T., Bakar, K., & bt Talib, Z. (2016). Food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practices among the street food vendors in Northern Kuching City, Sarawak. Borneo Science.

Samapundo, S., Thanh, T. C., Xhaferi, R., & Devlieghere, F. (2016). Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. Food Control, 70, 79-89.

Savitha, C. M. (1999). Impact of Training on Knowledge, Attitude and Symbolic Adoption of Value Added Products of Ragi by Farm Woman (Doctoral dissertation, University of Agricultural Sciences, GKVK).

Singh, P. K., Barman, K. K., & Varshney, J. G. (2016). Adoption behaviour of vegetable growers towards improved technologies. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 11(21), 62-65.

World Health Organization. (2014). WHO initiative to estimate the global burden of foodborne diseases: fourth formal meeting of the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG): sharing new results, making future plans, and preparing ground for the countries

Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) among Cabbage Consumers in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, Myanmar

ABSTRACT

In Myanmar, vegetable production is a major component of food safety strategy. Cabbage is such a vegetable vastly attacked by various kinds of pests. Wide and unsystematic use of pesticides and thus their residues are the main challenge for food safety. Inadequate food safety knowledge of consumers leads to not just negative impact on food safety practice but also causes health problems and shorter life expectancy among them. This study explored the relationship among the selected socio-economic factors, food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of cabbage consumers in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, Myanmar. A well-structured questionnaire with closed ended format questions was used to collect the data from respondents (n=80) about socio economic factors and food safety KAP attributes step by- step starting from food handling situation till up to their practicing behavior. Their responses were analyzed using Chi-Square test and Pearson correlation analysis. The results revealed that the highest proportion of respondents was medium-knowledge-level consumers and there was a highly significant correlation among the food safety KAP. All in all, social and mass media contact was the most influencing factor on food safety knowledge (FSK) at p < 0.01. Education and different annual income levels were correlated with FSK at p < 0.05. And age and family size also had a relationship with FSK at P < 0.1.

Key Words: Food safety, agrochemical residue, knowledge, attitude, practice.

INTRODUCTION

Food safety emerges as an important issue in human society, with increased media attention (Frewer, Shepherd & Sparks, 1994), consumer studies (Miles et al. 2004), and the establishment of new regulatory bodies. Nowadays, food safety is one of the most important agenda for public health, and it will also affect the economy and development of a country. The chain of food safety starts from farm to factory to fork and covers a wide range of processes from producing, handling and storing to food preparation and consumption. Foodborne illnesses, injuries and allergic reactions are the main causes of food safety hazards (Huziej, 2021). Factors influencing food hazards are contamination of soil and water, unsafe working conditions, pesticide misuse and pesticide residues.

There are three types of food hazards – biological, chemical, and physical. Biological hazards are caused by bacteria, parasites, fungi and viruses. These organisms around us, in air, soil, water, animals and humans can easily contaminate our food throughout the whole food chain and can cause foodborne illnesses apart from some beneficial ones such as bacteria and yeast used as probiotics, and in dairy, bread, and alcohol production (Huziej, 2021). Moreover, rodents, flies and other insects in agriculture can also cause biological hazards as vectors. The consequence of biological hazards is foodborne illnesses commonly known as food poisoning. These serious problems are caused by eating microorganism-contaminated foods through poor hygiene, improper handling, storing, and cooking. General symptoms are diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, high temperature and stomach cramps, which can vary from person to person and it generally occurs in hours or weeks after eating unsafe food. In some cases, it can be life-threatening.

Chemical hazards are inclusion of harmful substances such as pesticides, machine oils, fungicides, plant growth regulators, preservatives and other agrochemical substances which are usually applied in agriculture and food production. The results of improper use of these are ecosystem degradations and residual problems in food. Chemical residues are harmful to human if the amount exceeds maximum residue level (MRL). Thus, the most developed countries have set various MRLs in international trade for agricultural products.

Physical hazards are objects which contaminate our foods, such as pieces of glass or metal, toothpicks, jewelry or hair (Food safety hazards and culprits, n.d.). This contamination can also occur due to poor food handling practices and can choke and injure the consumers (Physical hazards in food, n.d.). Therefore, implementation of Good Hygiene Practices (GHP) and Hazard Analysis of Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan is essential along food processing in order to control this type of hazards. Every year, approximately 2.2 million people, the majority of whom are children living in developing countries, die as a result of food and water contamination (World Health Organization [WHO], 2008). According to the estimation of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the U.S.A. , 48 million people get sick from a foodborne illness, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die yearly (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016). The mortality rate had declined during the last 12 years and the reason may be implementation of food safety programs in most of the country.

In developing countries, nearly 75% of the 200,000 deaths were associated with pesticide poisoning even though they used only 15% of global pesticide supply (- Koul et al., 2004 2008 2011). In Myanmar as well as in some developing countries, food is a strategic product that helps increase the growth of economy and politics (Food safety hygiene, n.d.). Myanmar has a poor track record of preventing foodborne illnesses, plagued by low public awareness and weak adoption of food safety practices among producers, processors, distributors and consumers (Aung, 2019).

According to the global food security index of 2021, Myanmar ranked 72 in the area of food safety among 113 countries (Food security index, 2021). This position is very low compared to other Southeast Asian neighboring countries like Thailand (51) and Malaysia (39) and so on. Particularly, as food is one of the main media of virus dispersion, consumers in Myanmar are continuously faced with challenges of food safety.

Vegetables are the second most important food for daily consumption of Myanmar citizens after rice. To produce vegetables successfully, it requires proper use of all available resources especially in developing countries (Singh, Barman & Varshney, 2016). Normally vegetables are consumed as raw or semi processed forms, hence may hold on elevated amount of pesticide residues as compared to other foods including cereals and The problem of contamination of food sources, especially vegetables with pesticide residues constitutes to be one of the most serious challenges to public health.

Among vegetables, c (Brassica oleracea) is one of the most consumed vegetables in Myanmar. Myanmar people are using cabbage in various eating styles including fried cabbage or use it as an ingredient in some dishes and mostly they consume fresh cabbage in various salads like pickled tea salad. As insects and fungi are the main barriers in cabbage production, insecticides and fungicides have become the main chemical pesticides which are intensively used to suppress these problems like diamondback moth (DBM) and others. Furthermore, the effect of pesticide residues can be toxic to humans along the food chain and dispersed into the environment for the longest time. In Myanmar, 37 food poisoning cases occurred, which affected 1,320 people causing one death. And 17 diarrheal cases affected 567 people, leading to 11 , between 2017 and 2018, several studies have indicated the inadequate food safety standards. A research team of the Department of Medical Research tested 84 BBQ fish vendors in Yangon Region and found 27% of the fish contained the Vibrio bacteria. Another study by the regional government in Yangon showed that 93.5% of bean curds sold in the markets were laced with formalin. Another case displayed the poor safety concerns at factories, where one child died of lead poisoning and 15 other children were hospitalized in Hmawbi Township in Yangon. And a small-scale research executed in the Inle Lake region at the beginning of 2018 discovered that 75% of the vegetable samples from both villages and markets had pesticide residues exceeding the maximum residue limits. Food safety has not only serious impacts on the well-being of Myanmar citizens but also influences tourism, economy and the development of the objectives of this study are as follows:

RESEARCH METHODS

Study design and sampling

This study was carried out between April and May, 2022 in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, the new administrative capital city of Myanmar, and its estimated total population is 1,160,242. Zayar Thiri and Pobba Thiri Townships were purposively selected as study areas under the reason of very limited food safety research there. The majority of the respondents were female. All of them were cabbage consumers and the main persons who managed and prepared food for their families.

Data collection and questionnaire design

Concerning with primary data collection, the households were visited to explain the purpose of the study, and requested to participate voluntarily. The research was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire and all the questions were in Myanmar language for the convenience of respondents and it took about 15 minutes to answer the questionnaire. After getting agreement from participants to be involved in the study, the questionnaires were left with them and were collected after a couple of days. There were three main parts in the questionnaire. In the first part, the socio-economic information of the respondents such as age, gender, family size, education level, occupation, annual income, social and mass media exposure were asked. The second part had been designed to acquire the information about food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices on food handling, preparing, and storing in general. In the last part, general information consisted of consumer behavior for cabbage purchasing concerning with food safety. So as to transform the qualitative data into quantitative, all the questions with dichotomous and multichotomous format were coded into score of either ‘0’ or ‘1’. Five points Likert scale method was used and the answers were coded into Strongly Agree=5, Agree=4, Undecided=3, Disagree=2, Strongly Disagree=1 for positive statement questions but for negative statements the scores were the reverse ( Savitha, 1999).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS statistical package (version 23). Descriptive statistics were used and three levels of categorization methods – low (Mean-SD and below), medium (Mean + SD) and high (Mean + SD and above) – were provided for all data (Savitha, 1999). The scores of raw food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice of each individual respondent were converted into index values by using the following formulas:

To evaluate the association and correlations among socio-economic factors, food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) traits, Chi-Square test and Pearson correlation test were used in this study. As for P- value, < 0.1 (statistical significance), < 0.05 (statistical significance), and < 0.01 (statistical highly significance) were considered respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of food safety for cabbage consumers

As for consumers’ food safety (KAP) attributes, only 21.25% of the respondents fell in food safety high knowledge level group, whilst over 13% of the respondents were in high attitude level group, but in high practice level group, there were just 10% of the respondents. Among food safety KAP attributes, the trend was downward and the result revealed that they did not follow food safety rules and regulations, though their food safety knowledge was high. Detailed data were indicated in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

There were some indications of low knowledge level such as big-sized cabbages were free from insect boreholes and should be selected. Such cabbages might come out as the result of heavy agrochemical application. And they thought the same chopping board could be used to cut meat as well as vegetable without cleaning it with soap and consuming the fresh cabbage did not affect the health of consumers. They did not have the knowledge of correct hand washing and about systematical storage of prepared food. The reasons for low attitude level were they did not agree that prepared food should be kept at a safe temperature but agreed hole-free cabbage should be selected for their safety. The reasons for low practice level were that they were not interested in GAP crops, not familiar with using hand gloves and apron when they prepared food, always purchased hole-free cabbage, used to eating the fresh cabbage without giving some treatment, and never kept prepared food at safe temperature.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS AND FOOD SAFETY KNOWLEDGE LEVEL OF CABBAGE CONSUMERS

Association of age and FSK

Age is an important factor as aging may bring positive cognitive changes. The association between food safety knowledge and age of respondents was shown in Table 1. In the low knowledge group, the majority of the respondents (66.67%) were in middle age. The rest of the respondents were young and old, with 20.00% and 13.33%, respectively. In the medium knowledge level group, the percentage of middle age respondents (58.33%) was considerably higher than the other two groups as described in Table 1. In the high knowledge level group, there was no young respondent at all but the overwhelming majority of middle age respondents were amounting to 94.12%. A modest proportion of old respondents (5.88%) also were involved. According to the Chi-Square test, different age levels of respondents were significantly associated with the knowledge groups at p < 0.1.

Association of family size and FSK

Family size determines knowledge level based on family members’ experiences and knowledge sharing behavior. The association between food safety knowledge and family size was depicted in Table 2. In low knowledge level group, all of the respondents (100%) possessed medium family size. Likewise, in medium knowledge level group, a massive 81.25% of respondents occupied medium family size, followed by high family size with (10.42%), and low family size (8.33%) of respondents. In high knowledge level group, most respondents (76.47%) had medium family size but the rest of the respondents (23.53%) had low family size. The result of Chi-Square test analysis indicated that respondents’ family size level had a statistically significant association with various knowledge level groups at p < 0.1. This may be reasonable because idea innovation, sharing news and information in issues like food safety among family members will lead to the knowledge development of the family. So, there is no doubt that family size may be a catalytic agent to acquire update knowledge.

Association of education and FSK

Education level is a key determinant of knowledge, as well as attitude and practices (Fredi Alexander Diaz-Quijano et al., 2018). In low knowledge level group, the highest percentage of respondents had medium education level, contributing to 73.33%. This was followed by the respondents in low education level (20.00%) and the respondents in high education level (6.67%). In medium knowledge level group, the number of respondents in medium education level was higher than the other two education level groups (low and high), with 62.50% as opposed to 12.50% and 25.00%. In high knowledge level group, no one was low in education level and nearly half of the respondents (41.18%) had medium education level, and the other respondents (58.82%) had high education level. Additionally, there was a significant relationship between education levels and knowledge levels in Chi-Square analysis at p < 0.05, as highlighted in Table 3. As education focuses on developing critical thinking and problem solving skills of individuals, the illiterate person cannot be compared with the one who has high education level in acquisition of knowledge due to so many barriers.

Association of annual income and FSK

Annual income is a powerful factor to acquire food safety knowledge from different sources. In low knowledge level group, most of the respondents came from low income groups as compared to the medium income level group, 86.67% as opposed to 13.33%. In medium knowledge level group, the greatest percentage of respondents (93.75%) was in low annual income group, whereas a mere 6.25% of respondents were in high income group. In high knowledge group, approximately 100.00% of respondents were in low income level group. Chi-Square test result pointed out that there was a statistically significant relationship among these two variables at p < 0.05, as shown in Table 4. For instance, low income households cannot be interested in other matters except for their basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. For high income households, they have many choices for life, willingness to pay for quality products, and they will learn everything in specific to get better life.

Association of social and mass media contact and FSK

The role of social and mass media is important in upgrading and development of knowledge. Concerning the association among the social and mass media contact and food safety knowledge levels, in low knowledge level group, just over half of the respondents (53.33%) were low in social and mass media exposure and only 6.67% of respondents had high level exposure with social and mass media. Another 40.00% respondents were in medium exposure group to those. In medium knowledge level, low exposure level of respondents with social and mass media was twice as many as high level, with 39.58% in contrast to 16.67%. In high knowledge level group, just over half of the respondents (58.82%) had high social and mass media exposure, after which 23.53% of the respondents had low level in those and 17.65% of respondents had medium exposure, as highlighted in Table 5. Chi-Square test analysis indicated that the relationship among the different two variables was found to be statistically highly significant at p < 0.01. The possible reason may be being more exposed to social and mass media can be knowledgeable about something like COVID-19 crisis, political and health affairs, and food safety issues.

Correlation analysis among food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of cabbage consumers

The KAP scores were continuous and normally distributed, thus, Pearson correlation test was conducted so as to analyze the nature of relationship between the selected socio-economic factors and food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices. The correlation coefficients (r) values were presented in Table 6.

The results of correlation test described that age had non-significant relationship with food safety KAP attributes, which meant being younger or older did not influence food safety KAP attributes. In the finding of Ahmed, Akbar & Sadiq, 2021, KAP attributes of food handlers in Pakistan were assessed that age had no significant association with food safety knowledge and attitude but age had a significant association with practice.

There was no relationship between family size and food safety KAP attributes. Similarly, gender did not have any relationship with those. This current finding was in line with a study in Canada, which showed no association between FSK attribute of food handlers and gender (McIntyre et al., 2013).

The relationship between education and food safety knowledge and attitude had a statistically significant relationship at p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 respectively, but it had no relationship with practice. This finding was in agreement with the former studies that pointed out education level was significantly associated with food safety knowledge (Rahman et al., 2014 2016 2020). But in some different countries, some studies evaluated that there was no relationship between education level and food safety KAP attributes (Choudhury et al., 2011). Thus, to be clearer in that situation, further studies dealing with food safety should be carried out according to the specific areas of the country.

Social and mass media contact was found a positive and significant relationship with food safety KAP attributes, at p < 0.01, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05 respectively. Keeping in touch with social and mass media might support knowledge improvement because most knowledge came from daily exposure with our environment and modernized applications.

The relationship among food safety KAP attributes had highly significant correlation. That means these attributes had been influenced by each other.

CONCLUSION

Taking everything into consideration, this current study found that just over one in five of the cabbage consumers had high food safety knowledge level, over 13% had high food safety attitude level, and there were only 10% who followed food safety standards in reality. These data were evidence of how much they care about food safety. As cancer cases have gradually increased due to unsafe foods, higher medical cost has become an additional problem for poor and middle income households. Therefore, some solutions should be taken. In the consumers’ perspective, they also had responsibility for their own food safety by following safety standards such as purchasing commodities with the minimum chemical residue like GAP crop, and avoiding food products with preservatives (food dyes, formalin, etc.). No product can stand long in the market without consumers’ demand. Furthermore, proper food preparing practices should be followed including use of hand gloves and apron, proper storage, and proper treatment should be taken for vegetables and other food products. In the authorities’ concerns, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must restrict food sellers in market with some effective food safety rules and regulations, particularly in COVID-19 pandemic. Regular inspection for pesticide residues on food products and products’ quality in market should be taken in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Irrigation (MOALI). And more regional food safety education programs should be conducted. Activation of food safety law, regulation, GDP and living standard of a country are the determinants of food safety status of a country.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, M. H., Akbar, A., & Sadiq, M. B. (2021). Cross sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers in Lahore district, Pakistan. Heliyon, 7(11), e08420.

Armah, F. A. (2011). Assessment of pesticide residues in vegetables at the farm gate: Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) cultivation in Cape Coast, Ghana. Research Journal of Environmental Toxicology, 5(3), 180-202.

Aung, S. Y. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.irrawaddy.com/in-person/getting-serious-food-safety-myanmar....

Cenral Epidermiology Unit, Myanmar. Annual Health Report. Department of Public Health. 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Foodborne germs and illnesses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www. cdc. gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs. html.

Chan, A. (2018). Food Safety as a Challenge for Myanmar. Retrieved from https://www. myanmarinsider.com.

Choudhury, M., Mahanta, L., Goswami, J., Mazumder, M., & Pegoo, B. (2011). Socio-economic profile and food safety knowledge and practice of street food vendors in the city of Guwahati, Assam, India. Food Control, 22(2), 196-203.

Claeys, W. L., Schmit, J. F., Bragard, C., Maghuin-Rogister, G., Pussemier, L., & Schiffers, B. (2011). Exposure of several Belgian consumer groups to pesticide residues through fresh fruit and vegetable consumption. Food control, 22(3-4), 508-516.

Darko, G., & Akoto, O. (2008). Dietary intake of organophosphorus pesticide residues through vegetables from Kumasi, Ghana. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 46(12), 3703-3706.

Diaz-Quijano, F. A., Martínez-Vega, R. A., Rodriguez-Morales, A. J., Rojas-Calero, R. A., Luna-González, M. L., & Díaz-Quijano, R. G. (2018). Association between the level of education and knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue in the Caribbean region of Colombia. BMC public health, 18(1), 1-10.

Food safety hazards and culprits. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.unileverfoodsolutions.ie/chef-inspiration/from-chefs-for-che...

Food safety hygiene. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.gomyanmartours.com/food-safety-hygiene-in-myanmar/

Food security index. (2021). Retrieved from https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/ food-security-index/Index

Frewer, L. J., Shepherd, R., & Sparks, P. (1994). The interrelationship between perceived knowledge, control and risk associated with a range of food‐related hazards targeted at the individual, other people and society. Journal of food safety, 14(1), 19-40.

Htway, T. A. S., & Kallawicha, K. (2020). Factors associated with food safety knowledge and practice among street food vendors in Taunggyi Township, Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine, 20(3), 180-188.

Hubert, L., & Schultz, J. (1976). Quadratic assignment as a general data analysis strategy. British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology, 29(2), 190-241.

Huziej, M. (2021). What are the hazards in the food industry?

Koul, O., Dhaliwal, G. S., & Cuperus, G. W. (2004). Integrated pest management potential, constraints and challenges. CABI.

Liu, Z., Zhang, G., & Zhang, X. (2014). Urban street foods in Shijiazhuang city, China: Current status, safety practices and risk mitigating strategies. Food Control, 41, 212-218.

McIntyre, L., Vallaster, L., Wilcott, L., Henderson, S. B., & Kosatsky, T. (2013). Evaluation of food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported hand washing practices in FOODSAFE trained and untrained food handlers in British Columbia, Canada. Food Control, 30(1), 150-156.

Miles, S., Brennan, M., Kuznesof, S., Ness, M., Ritson, C., & Frewer, L. J. (2004). Public worry about specific food safety issues. British Food Journal, 106(1), 9–22.

Physical hazards in food. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.statefoodsafety.com/Resources/ Resources/naturally-occurring-physical-hazards-in-food

Quijano, F. A. D et al., 2018. Association between the level of education and knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue in the Caribbean region of Colombia. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 143.

Rahman, M. M., Arif, M. T., Bakar, K., & bt Talib, Z. (2016). Food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practices among the street food vendors in Northern Kuching City, Sarawak. Borneo Science.

Samapundo, S., Thanh, T. C., Xhaferi, R., & Devlieghere, F. (2016). Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. Food Control, 70, 79-89.

Savitha, C. M. (1999). Impact of Training on Knowledge, Attitude and Symbolic Adoption of Value Added Products of Ragi by Farm Woman (Doctoral dissertation, University of Agricultural Sciences, GKVK).

Singh, P. K., Barman, K. K., & Varshney, J. G. (2016). Adoption behaviour of vegetable growers towards improved technologies. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 11(21), 62-65.

World Health Organization. (2014). WHO initiative to estimate the global burden of foodborne diseases: fourth formal meeting of the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG): sharing new results, making future plans, and preparing ground for the countries