ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 virus met Germany, like the rest of Europe relatively unprepared. With the rising number of infections, the government implemented a first round of lock-down starting from mid-March up to mid-May. Just shops selling food stuff could stay open, while all shops providing “non-essential” goods and services had to be closed. Schools and kindergartens had to be closed as well and most people were advised to work from home. The government adopted a large number of financial support measures to keep companies going. Overall, the economy witnessed a steep decline, particularly during the second quarter, but it is gradually recovering since then. Compared to most neighboring countries in Europe, Germany did relatively well, so far. There had been a few incidences of COVID-19 outbreaks on farms, but these were restricted to fruit and vegetables farms which are highly dependent on seasonal labor. These farmers were burdened by higher labor costs due to the implementation of the required hygienic measures and by lower harvests. In general, farmers were affected by COVID-19 almost not at all. Actually, they registered an improvement of their image among the general public. Consumers had to change their way of life. Most of them faced empty shelves in supermarkets for the first time in their lives. The most necessary items for daily life were sold out over a certain period. Home cooking and home baking became more popular. Over time, it became evident that the demand for organic products, regional products, vegetarian and vegan products, and premium segments of the various products increased. While the restaurants and canteens were the main losers of COVID-19, the food retail industry can be identified as the big winner. These companies increased their annual turn-over significantly. Their growth rates were more than five times higher than during the years before. Within the group of retailers the full assortment suppliers gained additional market shares. Online shopping got a big boost, but it is still a niche market channel. Since November a second round of lock-down has to be observed. Therefore, it is difficult to predict how the economy, agricultural production and the food retail industry will be affected. However, for the time being, a slightly optimistic mood prevails.

Keywords: COVID-19, agricultural production, food processing, food retail systems, consumer attitudes, role of farmers

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic took German society and economy like the rest of Europe by surprise. Actually, the stocks of respiratory masks and other necessary equipment had been partly dismantled over time since there was the assumption that in case of need the international division of labor and the respective supply channels would be working satisfactorily. However, as it is turned out during the following weeks and months, the rules of the game had changed and everybody (in general: each country) was looking for its own “survival” first. In this contribution we will discuss the effects of COVID-19 on German agriculture and food consumption. In the next chapter we will briefly review the spreading of COVID-19 in Germany and the reaction of the German government in order to fight the virus. As it stands by the time of writing (November 2020) a second wave of COVID-19 spreading can be observed in the country as well as in the rest of Europe. In the following chapter we will discuss the repercussions of the pandemic on German agriculture which is followed by outlining the major impacts on food consumption as well as on the food retail industry. In this contribution we will exclude the meat (pork) sector which is the topic of a separate contribution. In a final chapter major (preliminary) conclusions will be drawn.

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF COVID-19 SPREADING IN GERMANY[1]

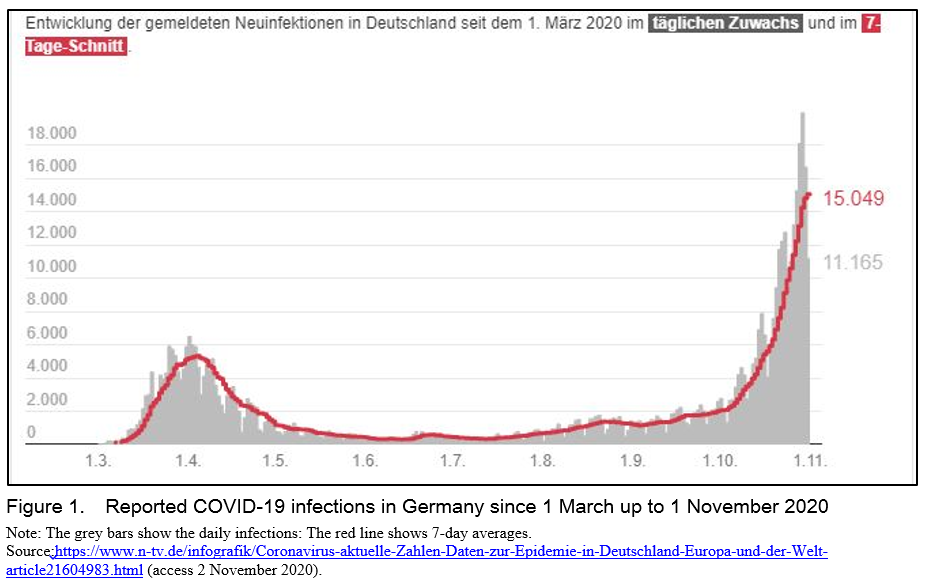

The COVID-19 virus was confirmed for the first time in Germany on 27 January 2020 near Munich, Bavaria. This case was followed by several cases during February in various parts of Southern Germany. The first major hotspot linked to a carnival event was detected in Heinsberg, a small town close to Cologne, at the end of February. Since then, more and more clusters were observed all over Germany. Up to 1 November 2020 there had been 532,930 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases and 10,481 deaths associated with this virus.[2] So far, two waves of COVID-19 infections can be distinguished. The first one started in late February up to early May. The number of new infections at a daily rate came up to about 6,000. In the following months a quieter period could be observed as due to summer, the virus was not spreading that much. Starting early September, the number of daily infections increased again culminating up to 20,000 new infections per day by early November 2020. In addition, the number of deaths associated with COVID-19 came up to 10,481 during this period. The basic situation with respect to the new infections is shown in Figure 1 below.

The government had to react to the quick spread of this unknown virus. During the first two weeks, people were ascertained that the national government and the local health offices which are actually responsible for monitoring and fighting all type of diseases at local levels including COVID-19 had everything under control. First countermeasures were implemented at the district and city levels, but soon more harmonized measures had to be coordinated at the federal state level. After a few days the national government together with the 16 federal state governments[3] implemented harsh measures to contain the virus. Starting 13 March 2020, the federal states mandated the closure of all schools and kindergartens and all academic semesters at universities were postponed. In addition, all visits by relatives and friends to nursing homes were prohibited in order to protect the elderly. Similarly, cultural life was curtailed. First all events with more 1,000 participants had been banned. Soon, all theaters and cinemas had to be closed. In some federal states, like Bavaria, all sports and leisure facilities were ordered to be closed. Other states quickly followed suit. In the same week all “non-essential” shops had to be closed as well; “non-essential” meaning all things which were not highly necessary for daily life. In principle, it followed that groceries and supermarkets could stay open while e.g. department stores like all other shops selling non-essential goods had to be closed. Finally, all people belonging to a “risk-group”, i.e. people older than 60 years and those with known medical and health histories, should stay at home. Actually, if ever possible, people should work from their homes in order to contain the spreading of the virus (“home office”).

All people had to observe the rule of restricting social contacts and keep physical distances between them and other persons at a minimum distance of 1.5 meters. In principle, people were asked to restrict physical contacts with members of just one other household. While at the beginning the number of masks had been in short supply, the government soon advised each citizen to observe the following three basic rules: (1) wear a head mask to cover your mouth and nose; (2) wash your hands as often as possible for at least 20 seconds each time; and (3) keep a physical distance of at least 1.5 meters from all persons which do not belong to your household. In the following months, these three basic rules had been extended by two new ones: (4) install and use the Corona warn app on your mobile, and (5) to air your rooms (offices) as often as possible (i.e. every 20-25 minutes).

Since the number of infections increased in the following days, the (federal state) governments implemented even harsher rules. Service providers which were regarded as “non-essential”, like hairdressers, fitness centers and/or bookshops had to be closed. Starting from 22 March all restaurants, pubs and bars had to be closed as well. In addition, the government prohibited all travel in coaches, the attention of religious meetings (services), the visit of playgrounds by children and adults alike and the engagement in tourism. That meant that hotels could accept no tourists anymore, just business people if any. International travel was restricted as most European and non-European states were declared as “unsafe”. With the adoption of the “German Protection against Infection Act” the government had the power to prohibit border crossings (meaning in fact a suspension of the right of free movement of German/EU nationals within the Schengen area[4]), track the contacts of infected persons and enlist doctors, medicine students and other health care workers in the efforts against this infectious disease. On the other side, supermarkets, chemist’s shops, banks, pet shops and all businesses that sell essential basic goods were allowed extending opening times, including on Sundays. But all these shops had to observe special “corona-rules”, i.e. ensuring that a physical distance could be ensured in the shops and offices (i.e. marking the distances on the floor or restricting the admission of customers to ensure that about 10 m² are available for each customer).

On 15 April 2020, the government stated that a “fragile intermediate success” had been achieved in slowing the spread of the virus. Shops with a retail space of up to 800 m², as well as bookshops, bike stores or car dealers, would be allowed to reopen on 20 April, if they followed specified conditions of distancing and hygiene. Similarly, hair dressers could start opening in early May. Cultural events were still banned. By mid-May it was decided that other major restrictions would be lifted by early June. All shops were allowed to open, schools and kindergartens may open in phases, people in care homes are allowed visits from one permanent contact person, outdoor sports without physical contacts could resume and sport leagues, like the German soccer league, could resume behind closed doors, i.e. without spectators. The decision to reopen restaurants was left to the individual federal states, but in general reopened again by mid-May. However, local governments were authorized to re-impose restrictions if the number of infections were exceeding 50 cases per 100,000 inhabitants within 7 days in their respective district/city.

On 3 June, the German government agreed to open borders for international travel starting 15 June 2020. But this was mainly restricted to the other 26 EU member states, the UK and some other European countries. Most of the rest of the world was banned or, at least, people going there should undergo a strict quarantine period of 14 days.

Early September infection figures started rising again. At the beginning, the government was more relaxed claiming that infection hotspots could be relatively easily marked (e.g. wedding parties, church services, returning visitors particularly from the Balkan States) and the routes of transmission could be identified. This attitude changed in October when the government had to admit that the virus was spreading all over the population. Local health offices could no more trace the transmission routes correctly, even if supported by the army. Now COVID-19 was spreading all over the country. But these rising numbers led to some “curious” events within Germany as free travel within the country became restricted. While over summer people were advised to avoid foreign countries for holidays and stay in Germany, many Federal States prohibited to accommodate tourists from regions with high infection rates (i.e. showing more than 50 infections per 100,000 inhabitants over the last 7 days) outside that respective federal state. In most cases the hotel associations went to court and, in general, these bans were lifted.

More and more, the government warned that this situation of exponentially rising infections would get out of hand and the health care system would be in no position anymore to handle all the newly infected persons properly. In the last week of October, the government decided in line with the 16 federal state governments that a second look-down was indispensable[5]. In fact, starting 2 November 2020 a “mild lock-down” lasting for four weeks had been implemented. Actually, it was a repetition of the first round, but some major components were exempted. The major objective is to cut all social and physical contacts to a minimum in order to give the virus no options of spreading anymore. Therefore, restaurants, bars, discos, theaters, cinemas, fitness clubs, etc. had to be closed again. Public and private companies were advised to look for every option to get their staff into home office. However, different to the first round of lock down, it was seen to keep the education system running, i.e. all kindergartens and schools were supposed to stay open. Similarly, the option of visiting relatives and friends in care homes was given. It had been the experience of the first round of lock-down that social contacts had been cut too rigorously and many children would fall out of the education system if not given the option of attending classes, physically. In addition, more shops could stay open, like book shops as well as hair dressers. Likewise, borders were left open in order to keep the economy going.

While social and economic life had to be downsized, the government acted swiftly to balance the economic losses. The most important measures can be summarized as follows: (1) unlimited credit to all companies of all sizes; (2) financial support (subsidies) to small and medium enterprises, artists, private cultural institutions and event companies; (3) expansion of the short-time workers compensation scheme up to 24 months[6]; (4) the suspension of bankruptcy (insolvency) regulations up to the end of the year, (5) a bonus for families with children amounting to €300 per child; and (6) a temporary reduction in VAT from 7% to 5% (basic necessities like food, newspapers, books, et.) and 19% to 16% (all other items, like the purchase of cars, furniture, etc.), respectively for the second half of 2020. The Parliament suspended the constitutionally enshrined debt brake (i.e. public institutions can make new debts up to 3% of the GDP per annum, only) and approved the supplementary government budgets. In total, the government is supposed to spend about €900 billion (i.e. a €750 billion financial aid package at 23 March 2020 and another stimulus package of €130 billion at 29 June 2020) for fighting the economic effects of the virus. So far, many companies have not applied for all that money, yet. Nevertheless, the government is determined to spend more funds if necessary.

In total, compared to neighboring countries Germany is doing relatively well economically. While during the quarter of 2020 GDP declined by 2.2%, there had been a massive fall to about minus 10% during the second quarter. Historically, this was the highest decline in the history of the (West) Germany. The decline was attributed to the collapse in exports as well as the shutdown of whole industries due to health protection measures (almost no business travel, no conferences and fairs, etc.). However, GDP increased during third quarter by 8.2%, again. The major forces for this growth are rising expenditures by private individuals and sharp increases in exports. In addition, companies are investing again, particularly in machines and equipment. So far, the unemployment rate did not rise much due to the payments of the short time workers compensation scheme. In April, about 6 million workers benefited from the scheme. In August 2020 their number stood at about 2.6 million. The official unemployment rate which stood at 4.8% in October 2019 went up to 5.8% in April 2020 and reached its peak in August with 6.4%. In October 2020, the unemployment rate came down to 6.0%.

There is uncertainty about the development in the fourth quarter due to effects of the second (mild) lock-down. In principle, the economic recovery slowed down particularly in those branches which are closely connected with personal and social contacts like (joint) eating-out in restaurants, meetings in bars and discotheques, visiting cultural events (cinemas, theatres, annual fairs and festivals, etc.), tourism (within Germany and abroad) and air travels. These branches will only develop again, once vaccinations will be available on a broader level. With respect to the whole year it is estimated that the GDP will decline by 5.5% which the highest decline since the economic crisis in 2008/9.[7]

IMPACT ON THE FOOD PRODUCTION SECTOR[8]

Farm production[9], particularly crop production is highly nature dependent. It is mainly based on rain fed farming and usually the production cycle lasts from early March up to late October. Therefore, typical labor peaks can be observed. Hence, the support of seasonal workers is highly important to get certain necessary tasks done in time. While the cultivation of major crops is highly mechanized, vegetable and fruit farming, and to some extent viticulture, depend on manual labor particularly during harvesting seasons. Without seasonal workers many of these farms could not survive. On average, about 100,000 foreign workers work on German farms annually, usually for a period of up to 70 days per individual assignment. In general, the majority of the workers come from Romania, Poland and Bulgaria. Usually, they are recruited by special employment companies, get information via Facebook groups, or in most cases, they get informed through mouth to mouth information (“neighbors recruit neighbors”). In many cases, seasonal workers are connected to the same farms over years. The farmers are, in general, providing lodging.

Therefore, the farmers had been heavily affected by the closure of German borders for foreigners, including foreign workers at 24 March 2020. The “normal” working processes could not be followed anymore and, hence, necessary work could not be done at all, or rather not in time. The Farmers’ Union lobbied with the government and it was agreed that during the months of April and May each, 40,000 foreign workers would be accepted or in total 80,000 for the full period. In addition, it was agreed on an extension of the maximum working period per individual worker from 70 to 115 days in order to reduce regular travelling by the workers from their home countries to the working places.

From now on, each farmer who wanted to recruit seasonal workers had to draft a farm concept about how to minimize contacts among workers as well as to the general public in order to avoid the spreading of COVID-19. While in the past housing conditions were not always optimal, farmers had to show that more space per worker had been available in order to ensure the necessary physical distance and to meet all hygienic requirements. In addition, workers could not travel by car or bus as it was the tradition, but had to come by plane. The seasonal workers had to undergo a health check at the airport of arrival and follow a 14-day quarantine period. Hence, farmers had to meet higher travelling and accommodation costs than in the past. On average, it was estimated that costs per individual worker would rise by about €500. Farmers complained that these rising costs were not covered by higher farm prices. However, the government acknowledged this fact to some extent and provided a subsidy of €150 per individual worker.

While in total 80,000 seasonal workers could have come to Germany, just about 39,000 actually did so by early June. The major reasons seem to be that infection rates in the respective home countries were quite high as well, so that willing persons themselves or members of their families were infected and they could not come. In addition, some farmers had problems in ensuring COVID-19-efficient working schedules, i.e. strict distance and hygienic measures. Nevertheless, the immigration of seasonal workers was relaxed once borders within the EU were reopened starting 15 June. Now, they could enter Germany by land, again. However, interested workers from non-EU countries, e.g. from the Balkan States, still had problems in applying for work.

Since the work on the farm is outdoors and the number of seasonal workers on a farm is mostly in the tens and not in the hundreds like in meat industry, only a few outbreaks of COVID-19 could be witnessed on farms. In addition, the fluctuation of the workers is not that high. The living and working conditions of the seasonal workers have a high impact on the spreading of the virus. There had been cases where workers were packed in mini-buses, living areas were too crowded and sanitary facilities were not in a good order. Therefore, farms were not safe from the virus. For example, 174 workers were infected on a vegetable farm in Lower Bavaria by late July as a hygienic and quarantine concept had not been properly implemented. But, in general, the health authorities could act swiftly and put the whole farm and its workers under quarantine. The major reason is the fact that farmers themselves provided accommodation to their workers, so that these places were company-owned flats which legally are part of the farm enterprise[10].

But farmers were not only affected by rising labor costs and a smaller supply of seasonal workers from abroad, due to COVID-19, many farms specialized in vegetable and fruit production faced lower incomes. Due to the shortage of labor, care activities and harvesting could not be managed as smoothly as in the past. Quite a number of these farms reported lower harvests. For example, with respect to asparagus which is usually harvested during the period starting by the end of March up to the end of June (actually overlapping with the total first lock-down period), the total harvest came up to about 100,000 tons which is just about three quarters of the average of the last years. In addition, the marketing channels had to be adjusted. The major part of the harvest had been sold via direct sale to the general public. That channel used to be relevant in the past as well, but this year, the other important channel, i.e. sales to restaurants, was only partly possible due to the lock-down (as shown above). At the beginning of the season, prices were about 10% higher than last year, but then they came down to the same level as last year.

With respect to the production and marketing of berries, the impact of COVID-19 was mixed. While farmers complained about labor shortages and rising labor cost and lower harvest, they were “blessed” by a sharp increase in berry prices. The major reason was not the impact of COVID-19, but a small harvest in the main exporting countries of Central and Eastern Europe. On the other side, a rising demand for fresh berries (soft fruits) could be observed. Hence, the fruit juice industry had to face higher costs. But, in general, the volumes of fruits and vegetables harvested were lower than during previous years, which according to the Farmers’ Union was mainly caused by the effects of COVID-19.

In total, a sharp increase of consumer prices with respect to fruits and vegetables could be observed due to COVID-19. Prices for fruits and vegetables went up by 11.0% and 6.5%, respectively, during the period from April 2019 to April 2020. The overall inflation was just 0.9% during that period. Hence, prices for these products (like food in general, as will be shown below) are accelerating overall inflation rates. It is assumed that those products which rely on a higher amount of manual labor will be more expensive. On the other side, some products, like e.g. potatoes were in oversupply. Due to the closure of restaurants and canteens, public events and a decline in exports, several hundred thousands of tons could not be sold and had to be stocked. The Farmers’ Union was calling for financial support to store all those products which could not find a market due to COVID-19, i.e. for support measures for private storage which is in line- under certain conditions - with EU regulations.

When looking at the impact of COVID-19 on the farm sector in general, the (preliminary) conclusion is that farmers were affected not that much. Just some specialized sub-groups, which make up a small share of all farmers, had to meet losses. Actually, farmers could benefit from the overall COVID-19 fiscal stimulus programs which were provided to small and medium enterprises (SME) in general. Farmers could get some tax reliefs and apply for investment and liquidity support. The overall VAT rate for food items was temporarily lowered from 7% to 5% for the second half of 2020. In order to promote investments in machines and other moveable assets, the depreciation rate was increased to 25% annually for 2020 and 2021, respectively, instead of the “normal” 10%, annually. When looking at the investments done by farmers during the first half of 2020 compared to the first half of 2019, they actually declined by almost 10%. As the Agricultural Bank reports, there is a slight increase in investments in machines, but a sharp decline in investments in buildings (stables) and agricultural land. It seems that COVID-19 did not have a major impact in decision-making, but other political issues were of more relevance (e.g. the new CAP rules for the period 2021-2027, the implementation of animal welfare rules, the new fertilizer regulations, etc.). This impression is reflected by reports of the farm machine industry. They were doing relatively well during 2020. The same impression is given by the reports of some major supply and marketing cooperatives. They are reporting a stable business performance during the first half of 2020 compared to the last years. One cooperative union (Agrarvis Raiffeisen AG) states that this year is running extremely well. COVID-19 seems to be just one challenge next to the impact of climatic change and the political discussion about important framework conditions under which farming will be done in the future which is accepted by society. This discussion is still ongoing and any guidelines for farm production in the future are still not specified, yet. Nevertheless, the Farmers’ Union also called for the postponement and more flexibility in the adoption and implementation of all types of legal requirements in crop production and animal husbandry which seems to be understandable from their side.

The major impact of COVID-19 on farmers and their profession seems to be an immaterial one. Following various food scandals over the last decades their reputation in society declined drastically. However, empty shelves have shown to the general public (see next chapter) that there is no “natural law” that they are fully stocked every day. The crisis has proven the importance of a reliable national food production of high quality. Farmers as individuals and the whole profession have noticed a higher level of acknowledgement of their work by the population. There seems to be a rising awareness among the population and politicians of the systemic relevance of farm production and the food sector as providers of enough food. In March 2020, 46% of the farmers felt that they were positively acknowledged by society. People realized that farmers have an important role in society. The concepts of national and regional food supply channels gained a new boost. Whether this positive image will last for long has to be seen. Already in September 2020 just 25% of farmers felt that they were acknowledged by the society.

IMPACT ON FOOD CONSUMPTION CHANNELS[11]

The impact of COVID-19 on food consumption has been very profound. In this chapter, we will discuss the impact on consumers themselves, provide an overview on gastronomy and the retail sector and especially look at the impact on e-grocery.

Consumers’ attitudes

The spreading of the virus and the following government measures met consumers at several “fronts”. Many of them were asked to stay at home and do home office. In addition, schools and kindergartens were closed so that kids had to stay at home requiring many parents to do “home schooling” and keep the younger kids happy which was not made easier as the children playgrounds were closed as well. Similarly, social life was restricted as people were allowed to meet other people from one household only. Similarly, visits to hospitals and nursing homes were no more allowed. Cultural, leisure and sport activities were banned. Restaurants and canteens were closed as well (see below). Hence, just food stores, supermarkets, etc. selling food stuffs were still open. Hence, for many people food shopping was the only reason to leave their homes. In short, people had to adjust their daily lives completely.

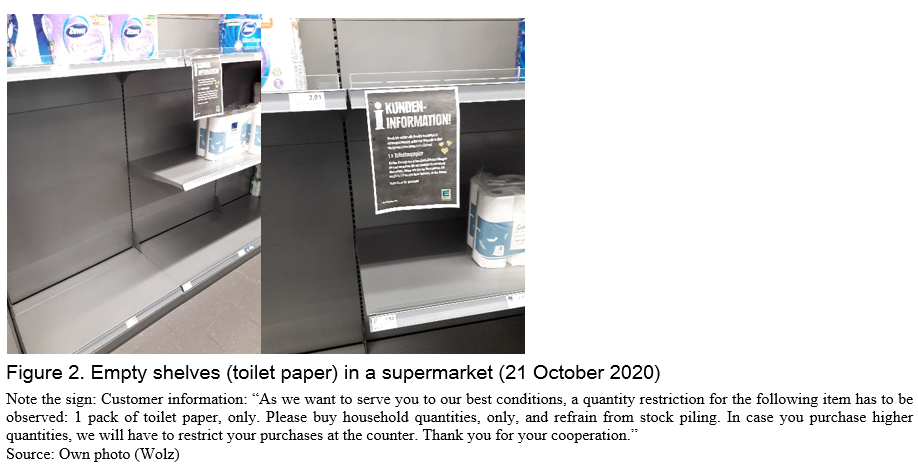

German consumers reacted in shock upon the arrival of COVID-19. Already, by the end of February 2020, people rushed to the supermarkets. There was panic buying and hoarding of basic consumer goods. The major discounters were reporting a sharp increase in demand, particularly for tinned food, noodles, flour, toilet paper, soap and disinfectants. Since, even the well-developed German retail sector could not refill the shelves in time, German consumers were confronted with empty shelves over a couple of weeks with respect to some products. This was a completely new experience to most of them, since only the elder ones might remember the situation before the introduction of the West-German D-Mark at 20 June 1948. East Germans have experienced empty shelves from time to time, but the provision of basic necessities was always ensured. Most Germans were surprised that they did not find basic food and other items of daily life in the shelves, or got items in a fixed ration (see Figure 2).

During the weeks from late February to early March sales of canned food, noodles and toilet paper rose by 700% according to the reports of some discounters. An overview of the major trends during the first months of 2020 is shown in Figure 3.

The increases of purchases had been significant when COVID-19 became a political issue by late February. At the beginning paper products and home and body care items were in high demand. Once the panic buying was over and shelves re-stocked people had to use their stocks first before buying new items. Hence, the demand for these specific products declined rapidly. With respect to the products under the category “home and body care” it is assumed that people did not see the need to use them that often anymore, since many of them were in home office and social contacts had to be down-scaled. The purchases of food and drinks increased sharply when canteens and restaurants had to be closed. It is assumed that the people, if they cannot spend their money in restaurants they were buying “good food” and delicacies for home cooking. While the purchases of noodles, flour and rice declined since there were full stocks at homes, people were switching to high value food. People were changing their eating habits. Indeed, home cooking and home baking became more and more popular during the second quarter of 2020. Once, restaurants and canteen could re-open again by mid-May, the purchases for food and drinks stayed at a high level and gradually went down. But they remained on a relatively high level since many people did not spend their holidays abroad as they used to, but stayed in Germany; often in holiday flats where they often preferred self-catering.

By the end of September, the first signs of shopping behavior like in late February/early March at the beginning of the first wave of COVID-19 were observed. With the rising infection rates starting early September, people seem to fall back to panic buying. According to the Federal Statistical Office a high increase in demand during the week up to 18 October compared to the average weeks from August 2019 up to January 2020 was observed. The sales with respect e.g. to flour increased by 28.4%, to yeast by 34.8% and to rice by 53.3%, respectively. On the other side, the demand of sugar just increased by 2.5%. However, similar to the first wave, there had been very high increases in the demand of toilet paper by 90%, of disinfectants by 72.5% and of soap by 63.3%. It seems that a second wave of panic buying and hording had arrived.

At this stage, it is still open whether COVID-19 implemented a change in eating habits in the future. It has to be seen whether people eat less out-of-home and spend more time in preparing meals at home (self-cooking at home) which might also mean spending more time with family members and, may be, friends at home. In addition, it is open whether German consumers, who have a reputation of being very price-conscious instead of looking for quality, will spend more money on high-valued food, including delicacies, in the future.

Impact on gastronomy and retail sector

When the government declared the look-down by 22 March 2020, in addition to all “non-essential” shops, all restaurants, canteen, bars, clubs, etc. had to be closed. For information, out-of-home eating is a big market in Germany. In 2019, the turn-over came up to about €75 billion. About 1.8 million people are employed by this sector compared to about 1.1 million in the mechanical engineering sector. But it is characterized by small-scale enterprises. From the total number of 186,000 units about three-quarters employ less than 10 persons. Operators had only one option to stay in business, when they offered food and dishes “to go”. Needless to say that this option only made sense to some of them. In addition, it is known that the gastronomy in Germany is not earning much money with food, but the major share of income is made up by the sales of drinks in conjunction with it. Restaurant operators were protesting against the enforced closure arguing that the probability of getting infected in restaurants would be small and they were facing insolvency quickly so that many jobs would be lost forever. They were quite imaginative in their protests as shown in Figure 4 when they pointed out the empty chairs at their restaurants.

By mid-May the gastronomy (in addition to hotels) could return back to business. However, operators had to follow strict hygienic measures, i.e. they had to ensure a certain minimum area for each customer. Similarly, they had to record the names of their guests to facilitate traceability in case an infection might be encountered. In general, the number of tables per restaurant had to be lowered and less people could be seated at one table. All this meant that, even, if all available seats were served, the turnover was lower than during the pre-COVID-19 times. On the other side, local authorities were more relaxed in granting restaurants larger out-door areas, e.g. in quickly converting parking space for additional tables. In addition, the weather during summer had been excellent so that many operators could benefit from this measure. But, in general, it could be observed that customers did not visit restaurants that often, anymore, as during the pre-COVID-19 period. E.g., a survey executed by the University of Göttingen showed that just one-third of the respondents had been to a restaurant again by mid-June. In addition, most meals with respect to business meetings were cancelled.

Therefore, the sector witnessed a sharp decline in turnover. According to the Federal Statistical Office, the turnover of gastronomy declined by 40.5% during the six-month period starting from March to August 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. The financial losses had been particularly high during April with about 68.3%. In the following months the losses decreased gradually, but still in August they came up to 22.3%. Specifically, those enterprises had been affected which relied on the sales of drinks, e.g. pubs, bars and discotheques. Their turn-over declined by 45.5%. Restaurants, taverns and small snack-bars could compensate part of their customers’ decline by offering take-away food. Their economic losses came up to 29.3%, “only”.

While the gastronomy, in total, witnessed a sharp decline in their turnover, the providers of “food to go” services were the winners in this segment. Some restaurants had already built up their delivery services in the past and many restaurants established “food to go” services (either pick-up yourself or delivery to homes) in order to ensure at least a decent cash flow. In general, these delivery services are coordinated in Germany by online platforms which are also organizing the delivery of the dishes. Since 2019, the company “Lieferando” is the market leader and starting from 2020 it has an almost monopolistic position. Its turnover more than doubled during the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, i.e. from €80 million to €161 million. In general, the company gets a share of 30% of the end price which is paid by the customer (during the lockdown period 25%)[12]. Assuming these figures, the total turnover of delivered food made up about half a billion € in 2019 which amounts to less than one percent of the total turnover in gastronomy. In 2020, its share will increase to almost 2%, since the overall turnover has declined. But still, for the time being food delivery is just a niche market.

Restaurant operators were eligible for the various government support measures. In addition, they could rely on the suspension of the bankruptcy obligations. So far, the number of insolvencies remained more or less stable in comparison to the same period in 2019. Between March and July 2020 just 753 enterprises entered insolvency (bankruptcy) procedures which are actually 126 cases less than during the same period in 2019. But it is assumed that many restaurant operators will apply for insolvency once the suspension period will be expired. In addition, it is assumed that many operators will not survive economically during the second lock down period.

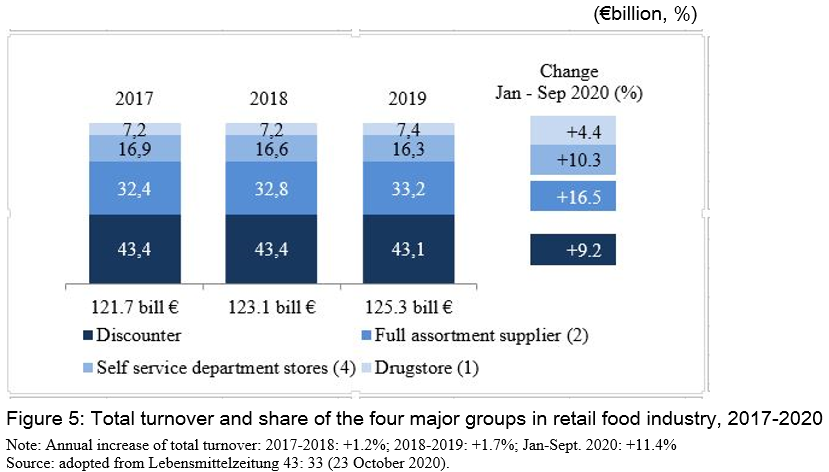

With respect to the food retail sector the picture is completely different. They can be seen as the big “winners” of the COVID-19. When restaurants and canteens had to be closed, people had to work from home, all educational institutions had to be closed and people had to observe “social distancing” measures, people rushed to the shops buying food. The overall development is summarized in Figure 5.

The German food retail sector is highly competitive. The annual turnover of the whole sector gradually increased from about €120 billion to about €125 billion during the last years. Overall, the turnover of the whole sector is increasing moderately, e.g. from 2017 to 2018 by 1.2% and from 2018 to 2019 by 1.7%, respectively. Therefore, the increase of 11.4% from January – September 2020 compared to the same period a year before signifies a significant “leap forward.” When looking at the four major groups of the retail food industry, they all could report higher increases compared to the years before. However, when looking at the four groups separately, the companies coming under “full assortment suppliers,” like Rewe, Edeka, Globus, etc. show the highest growth rates with respect to turnover amounting to 16.5%. The major reason seems to be that consumers had to stay home and, if they went on holidays at all, they stayed within Germany, very often in holiday apartments and were doing home cooking. Therefore, according to food experts, consumers were not in a festive mood, but they wanted to feel good and bought more of the higher priced food items and drinks. The discounters, like Aldi, Lidl, Norma, Penny, etc. serve more the price-conscious consumers who also bought higher quantities but not many products of the high-price segments. The self-service department stores, like Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof, also serve high-income consumers, but faced huge structural problems in finalizing insolvency procedures which were running since early 2019. The drug stores, like DM, Müller, Rossman, etc. were the main winners at the beginning of COVID-19 period, when people rushed to buy paper products, soaps, disinfectants, etc. But then their turnover increased only marginally.

When looking at the major changes of consumers’ purchasing patterns the COVID-19 crisis had enforced food trends which could already be observed during the past. The major trends are an increase in the demand for (1) organic products, (2) products from the same locality (regional products), (3) vegetarian and vegan products (meat-like products), and (4) premium segments of the various products. Whether we will see a change of German food shopping behavior will have to be seen. While Germans were described as completely price-conscious, food experts come now to the conclusion that many consumers are equating “cheap food with the pandemic”.

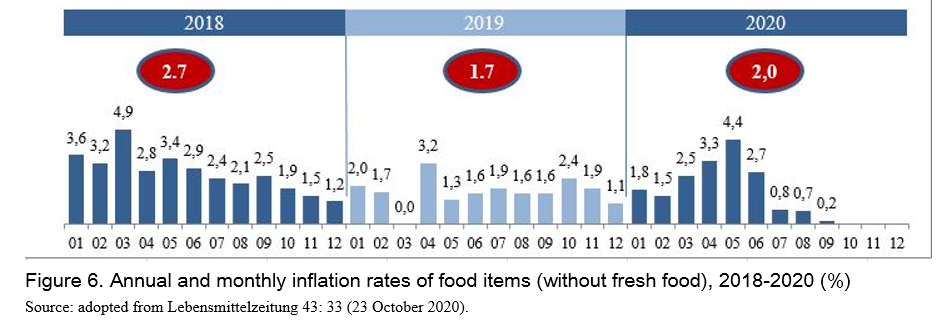

Due to the highly competitive nature in the food retail industry the increase in annual turnover is mainly made up by selling large quantities and higher prices segments of the various products. This is reflected in Figure 6 above which shows the average inflation rates of food items.

This figure does not fully represent the annual inflation rate of all food items, but it comes pretty close to it. Just fresh food products sold on weekly markets or by specialized delicacy food shops are not included. It shows that at the beginning of the crisis food prices went up rapidly. But starting with summer, they declined significantly. Hence, there had been no shortages at all, anymore. Just for comparison, the overall inflation rate came up to about 1.5% during spring and was minus 0.2% in September. Hence, the increases of food prices used to be a bit above the overall inflation rate during the last years.

The COVID-19 had a large impact on various food industries. At this stage, we just want to discuss the confectionary, beer and wine markets. The confectionary (sweets) industry reported a sharp decline in their turnover. While sales through the shops of the food retail industry increased, all other major outlets of sale were almost wiped out. During the period of first lock-down specialized sweet shops had to be closed for several weeks. Almost all public festivals (like e.g. the October Fest), fairs and Christmas markets were called off, actually for the whole year. Other major marketing channels like shopping malls, train stations, airports, leisure facilities and cinemas were not fully operational, or even not at all. Exports have declined as well. On the other hand, there have been significant cost increases. There had been higher amounts of absenteeism, as workers belonging to high-risk groups and parents who had to look after their children during the period of closure of schools and kindergartens had to stay home. Similarly, the production processes were challenged due to the need to ensure minimum distances in the production process at production facilities and to observe higher hygienic rules. In addition, it became more difficult to get access to raw materials from abroad and the payment behavior of clients had declined. In a survey by the Association of German Sweets Industry among its members in August 2020, more than half of the respondents reported a decline in turnover during the first six months.

With respect to the beer market, a similar picture emerges. The rise in home consumption could not balance the losses of the other sales channels. The sales through the shops of the food retail industry increased sharply (“beer in bottles”), but the supply channel via bars, clubs and discotheques had been cut (“beer in barrels”). In addition, breweries were severely affected by the fact that almost all annual fairs and festivals had to be cancelled. In addition, soccer matches had to be postponed for almost two months. When they were taken up again by late May, they could only take place without spectators. When some spectators were allowed again with the start of the new season in September, sales of alcoholic drinks were banned. Overall, there has been a decline in beer consumption by 6.6% or about 300 million liters during the first half of 2020. During the months of April and May the decline had been even more than 10%, respectively compared to the months one year ago. In total, the German breweries call this year as one of the worst years in recent times.[13] Again, with respect to wine, a similar type of development could be observed. As a result of survey among wine consumers in 8 different European countries[14] during the first round of lock-down, it was found out that the frequency of personal wine consumption has increased sharply. However, when drinking at home, people were buying cheaper varieties compared to visits in a restaurant. On a personal level, people seemed to drink more due to personal reasons, like e.g. they liked the taste or that wine relaxes them than for social ones, e.g. like sharing and being together with friends. The latter option was not feasible during the time of the lock-down. In general, this survey underlines the reports of the wine industry that the sales via supermarkets, etc. increased, but the share of premium wines, including sparkling wines, declined.

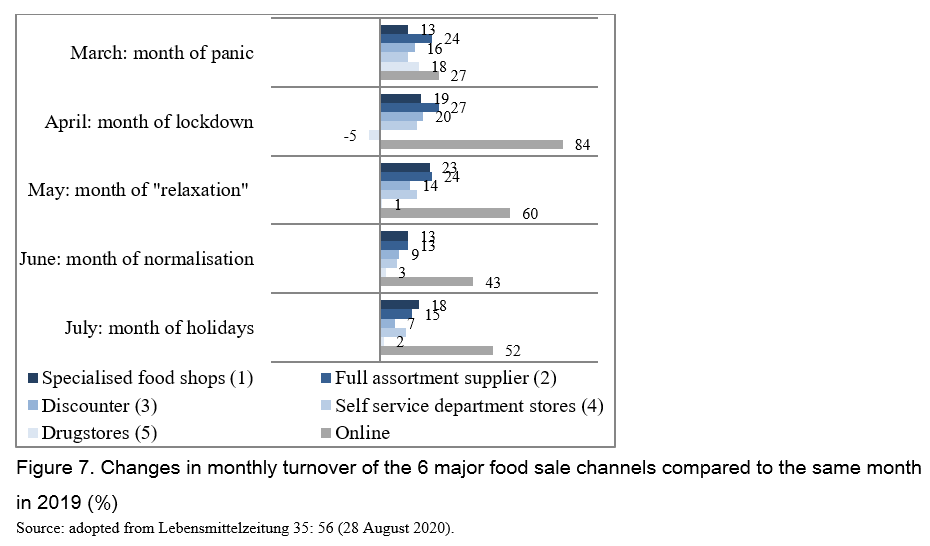

Finally, we want to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on the sales of various food distribution channels over a 5-month period starting in March up to July 2020. While first conclusions were discussed above (as shown in Figure 5) a broader picture is presented in Figure 7, which includes specialist food shops and online sales as well.

As discussed above, food retailers in Germany are very well organized and in most areas consumers have a selection of different companies and, hence, very good choices. The specialized food shops, in general, cover the demand for premium food and benefitted from the rising demand for these products. But compared to the four major outlets of the food retail industry the turnover stands at the hundreds of millions while the “big four” report billions and tens of billions euros. An interesting phenomenon is the development of online shopping of food (e-grocery). It has shown very high growth rates in monthly turnovers particularly since the arrival of COVID-19. Actually, 26 February 2020 has not only been the start of panic buying, but also a “shoot in the arm” of e-grocery. It opened a window of opportunity for this young type of business. But it has to be admitted that e-grocery started in Germany from a very low level. During the second quarter the overall turn-over came up to €772 million which is almost double the turn-over of the respective period in 2019. Starting from that date, more and more people got scared and started shopping online instead of going to a supermarket. Therefore, the e-grocery service providers could expand their customer base, significantly.

However, the companies specializing in e-grocery were overburdened by success. They were not prepared for this boost following the spread of the virus. Since they are relatively small, they just cover small areas, usually urban areas. Similarly, they have only a limited number of products in their stores. Therefore, potential customers had to be put on waiting lists. In addition, the delivery times were sometimes not very attractive. During the period of the first lock-down, it could be observed that customers had to wait for deliveries up to two weeks. Therefore, companies have to and will invest in their infrastructure and improvement of services. It is expected that the e-grocery market will grow during the second lock down period starting from November. [15]

But even this boost due to COVID-19 does not indicate a fundamental long-term shift from stationary to online food retail. The companies, like AmazonFresh and the German market leader HelloFresh gained a bit. Even though new start-ups appeared, the online food retail remained essentially unchanged in terms of the dominant business models and distribution mechanisms. With respect to the medium-term future its growth potential is limited. German stationary retail provides the densest net of food stores in Europe, which limits the necessity for online retail. Actually, before Corona, there was no need for e-commerce (Dannenberg et al., 2020). Nevertheless, investors are confident that e-grocery will have a future, particularly in urban areas. For example, the stock market price of HelloFresh which is traded at the Frankfurt Stock Exchange stood at round €8 in April 2019. In March 2020, it came up to about €19 and its price increased even further to more €41 in May 2020. Since then, it price increased a bit further, coming up to almost €50 by early November.

CONCLUSIONS

When COVID-19 hit Germany, the society and economy were not well prepared. But the government reacted swiftly, keeping in mind the development in China, Spain and, particularly in Italy. With the rising number of infections, the government implemented a first round of lock-down starting from mid-March up to mid-May. Schools, kindergartens, restaurants and all “non-essential” shops and businesses had to be closed. In addition, visits to nursing homes, church services, sport events, annual fairs, etc. had to be called off. People were encouraged to work from home (“home office”). To balance the financial burden of companies and free-lancers, the government adopted a large number of financial support measures, e.g. credit and subsidies, a suspension of the bankruptcy regulations, expansion of the short-time workers compensation scheme or the temporary reduction of the VAT rates. Overall, the economy witnessed a steep decline, particularly during the second quarter, but the government is optimistic that it will recover starting with the third quarter. Compared to most neighboring countries in Europe, Germany did relatively well, so far.

The agricultural sector, in particular crop farming, was just partly hit by the pandemic. Seasonal workers could not come and go as they used to do in the past. It was realized that their working and living conditions had a strong influence on the spreading of the virus. Hence, farmers specialized in fruit and vegetables had to meet higher labor costs and to face lower harvests. This relatively small share of farmers was negatively affected by COVID-19 but farmers in general were not affected at all. They are facing other problems, like the impact of climate change, the criteria of agricultural policies for the future CAP-period 2021-2027, which led to lower investments in land and buildings. However, farmers benefited indirectly in a “better image” as the general public realized that a steady provision of good food is not always self-evident.

Consumers had to change their way of life due to COVID-19. Most of them faced empty shelves at supermarkets for the first time in their life. Schools and kindergartens had to be closed, most shops which were providing “non-essential” goods or services had to be closed as well. Many of them, in active working age, were required to do “home office”. Consumers undertook more “home cooking” and “home baking.” They spent more time within the family. Whether this new development will be a win or loss in the future, is still open at this stage. With respect to food, trends of the last years were accelerated, especially demand for (1) organic products, (2) local (regional) products, (3) vegetarian and vegan products (meat-like products), and (4) premium products from various segments increased. Whether German consumers can change their image from nitty-gritty price pickers to one of acknowledging high-value food and willing to pay for it, has to be seen.

The big losers of the pandemic are restaurants and canteens and their respective suppliers of the food industries. They lost their total turnover during the lock down period. After re-opening they had to implement hygienic concepts which required more space per customer and as a consequence to less customers and less turnover. Hence, even after re-opening, their turnover declined compared to 2019. In addition, many people avoided to go to restaurants, again, due to infection risks and almost all business lunches and dinners were cancelled as well. Food delivery services are the big winners, but still they operate in a niche market.

Food retailers are the big winners of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany regarding the development of turnover. Food shops and supermarkets remained open and people rushed to buy food and other essential products for daily life. While during the past years, overall annual turnover of food retailers increased by 1-2%, only, they reported an increase of more than 10% in 2020, so far. Within the group of retailers, the full assortment suppliers, like the companies of Rewe and Edeka, gained market shares. This group seems to meet the changing consumer demands best. Online shopping got a big boost, but it started from a very low basis as the supermarkets in Germany provide the densest network within Europe. Hence, it is still a niche market channel. But, besides the increase in turnover, food retailers had to face considerable costs resulting from the hygienic concepts that they had to implement.

So far, Germany is doing relatively well. However, a second lock-down period has been proclaimed for the whole month of November 2020. Hence, it is very difficult to predict how the economy in general, and the agricultural sector and food retail industry in specific will perform in the coming months. So far, a slightly optimistic mood dominates.

REFERENCE

Agra-Europe (2020). Various weekly editions. Bonn, Agra-Europe GmbH.

Dannenberg, P., Fuchs, M.,Riedler, T. and C. Wiedemann (2020). Digital Transition by COVID-19 Pandemic? The German Food Online Food Retail. Tjidschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111 (3), 543-560.

Deutscher Bauernverband (DBV) (2020). Geschäftsbericht des Deutschen Bauernverbandes 2019/2020. Berlin, DBV (https://www.bauernverband.de/der-verband/geschaeftsbericht) (access: 12 October 2020).

Lebensmittelzeitung (2020). Various weekly editions. Frankfurt/Main, Deutscher Fachverlag GmbH.

[3] Germany is made up by 16 federal states. These states have a lot of leeway in implementing policy measures with respect to educational issues, e.g. close-down of kindergartens, schools and universities, internal security and public health. Therefore, measures have not necessarily been introduced at the same date with respect to the individual states. Particularly, with respect to health issues, these regulations have to be put into practice and supervised by the health offices at district and city level. These offices have a certain degree of freedom how things are implemented in their respective area of responsibility.

[4] Actually, most neighboring countries had closed their borders to Germany, already

[5] In all neighboring states the situation became even more alarming.

[6] Under this scheme employers and companies get a subsidy for the wage payments (salaries) if they keep their employees and workers employed instead of sending them into unemployment.

[8] This part draws heavily on the information given by the German weekly “Agra-Europe”.

[9] The impact on animal husbandry will be discussed in a separate paper.

[10] In case the employer is renting flats for the seasonal workforce on the market, these flats are independent units. In that case, the inviolacy and privacy of the flat are ensured as enshrined in the German Basic Law (Constitution).

[11] This chapter is mainly based on the German weeklies “Agra-Europe” and “Lebensmittelzeitung”.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Production and Consumption in Germany - A Preliminary Assessment

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 virus met Germany, like the rest of Europe relatively unprepared. With the rising number of infections, the government implemented a first round of lock-down starting from mid-March up to mid-May. Just shops selling food stuff could stay open, while all shops providing “non-essential” goods and services had to be closed. Schools and kindergartens had to be closed as well and most people were advised to work from home. The government adopted a large number of financial support measures to keep companies going. Overall, the economy witnessed a steep decline, particularly during the second quarter, but it is gradually recovering since then. Compared to most neighboring countries in Europe, Germany did relatively well, so far. There had been a few incidences of COVID-19 outbreaks on farms, but these were restricted to fruit and vegetables farms which are highly dependent on seasonal labor. These farmers were burdened by higher labor costs due to the implementation of the required hygienic measures and by lower harvests. In general, farmers were affected by COVID-19 almost not at all. Actually, they registered an improvement of their image among the general public. Consumers had to change their way of life. Most of them faced empty shelves in supermarkets for the first time in their lives. The most necessary items for daily life were sold out over a certain period. Home cooking and home baking became more popular. Over time, it became evident that the demand for organic products, regional products, vegetarian and vegan products, and premium segments of the various products increased. While the restaurants and canteens were the main losers of COVID-19, the food retail industry can be identified as the big winner. These companies increased their annual turn-over significantly. Their growth rates were more than five times higher than during the years before. Within the group of retailers the full assortment suppliers gained additional market shares. Online shopping got a big boost, but it is still a niche market channel. Since November a second round of lock-down has to be observed. Therefore, it is difficult to predict how the economy, agricultural production and the food retail industry will be affected. However, for the time being, a slightly optimistic mood prevails.

Keywords: COVID-19, agricultural production, food processing, food retail systems, consumer attitudes, role of farmers

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic took German society and economy like the rest of Europe by surprise. Actually, the stocks of respiratory masks and other necessary equipment had been partly dismantled over time since there was the assumption that in case of need the international division of labor and the respective supply channels would be working satisfactorily. However, as it is turned out during the following weeks and months, the rules of the game had changed and everybody (in general: each country) was looking for its own “survival” first. In this contribution we will discuss the effects of COVID-19 on German agriculture and food consumption. In the next chapter we will briefly review the spreading of COVID-19 in Germany and the reaction of the German government in order to fight the virus. As it stands by the time of writing (November 2020) a second wave of COVID-19 spreading can be observed in the country as well as in the rest of Europe. In the following chapter we will discuss the repercussions of the pandemic on German agriculture which is followed by outlining the major impacts on food consumption as well as on the food retail industry. In this contribution we will exclude the meat (pork) sector which is the topic of a separate contribution. In a final chapter major (preliminary) conclusions will be drawn.

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF COVID-19 SPREADING IN GERMANY[1]

The COVID-19 virus was confirmed for the first time in Germany on 27 January 2020 near Munich, Bavaria. This case was followed by several cases during February in various parts of Southern Germany. The first major hotspot linked to a carnival event was detected in Heinsberg, a small town close to Cologne, at the end of February. Since then, more and more clusters were observed all over Germany. Up to 1 November 2020 there had been 532,930 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases and 10,481 deaths associated with this virus.[2] So far, two waves of COVID-19 infections can be distinguished. The first one started in late February up to early May. The number of new infections at a daily rate came up to about 6,000. In the following months a quieter period could be observed as due to summer, the virus was not spreading that much. Starting early September, the number of daily infections increased again culminating up to 20,000 new infections per day by early November 2020. In addition, the number of deaths associated with COVID-19 came up to 10,481 during this period. The basic situation with respect to the new infections is shown in Figure 1 below.

The government had to react to the quick spread of this unknown virus. During the first two weeks, people were ascertained that the national government and the local health offices which are actually responsible for monitoring and fighting all type of diseases at local levels including COVID-19 had everything under control. First countermeasures were implemented at the district and city levels, but soon more harmonized measures had to be coordinated at the federal state level. After a few days the national government together with the 16 federal state governments[3] implemented harsh measures to contain the virus. Starting 13 March 2020, the federal states mandated the closure of all schools and kindergartens and all academic semesters at universities were postponed. In addition, all visits by relatives and friends to nursing homes were prohibited in order to protect the elderly. Similarly, cultural life was curtailed. First all events with more 1,000 participants had been banned. Soon, all theaters and cinemas had to be closed. In some federal states, like Bavaria, all sports and leisure facilities were ordered to be closed. Other states quickly followed suit. In the same week all “non-essential” shops had to be closed as well; “non-essential” meaning all things which were not highly necessary for daily life. In principle, it followed that groceries and supermarkets could stay open while e.g. department stores like all other shops selling non-essential goods had to be closed. Finally, all people belonging to a “risk-group”, i.e. people older than 60 years and those with known medical and health histories, should stay at home. Actually, if ever possible, people should work from their homes in order to contain the spreading of the virus (“home office”).

All people had to observe the rule of restricting social contacts and keep physical distances between them and other persons at a minimum distance of 1.5 meters. In principle, people were asked to restrict physical contacts with members of just one other household. While at the beginning the number of masks had been in short supply, the government soon advised each citizen to observe the following three basic rules: (1) wear a head mask to cover your mouth and nose; (2) wash your hands as often as possible for at least 20 seconds each time; and (3) keep a physical distance of at least 1.5 meters from all persons which do not belong to your household. In the following months, these three basic rules had been extended by two new ones: (4) install and use the Corona warn app on your mobile, and (5) to air your rooms (offices) as often as possible (i.e. every 20-25 minutes).

Since the number of infections increased in the following days, the (federal state) governments implemented even harsher rules. Service providers which were regarded as “non-essential”, like hairdressers, fitness centers and/or bookshops had to be closed. Starting from 22 March all restaurants, pubs and bars had to be closed as well. In addition, the government prohibited all travel in coaches, the attention of religious meetings (services), the visit of playgrounds by children and adults alike and the engagement in tourism. That meant that hotels could accept no tourists anymore, just business people if any. International travel was restricted as most European and non-European states were declared as “unsafe”. With the adoption of the “German Protection against Infection Act” the government had the power to prohibit border crossings (meaning in fact a suspension of the right of free movement of German/EU nationals within the Schengen area[4]), track the contacts of infected persons and enlist doctors, medicine students and other health care workers in the efforts against this infectious disease. On the other side, supermarkets, chemist’s shops, banks, pet shops and all businesses that sell essential basic goods were allowed extending opening times, including on Sundays. But all these shops had to observe special “corona-rules”, i.e. ensuring that a physical distance could be ensured in the shops and offices (i.e. marking the distances on the floor or restricting the admission of customers to ensure that about 10 m² are available for each customer).

On 15 April 2020, the government stated that a “fragile intermediate success” had been achieved in slowing the spread of the virus. Shops with a retail space of up to 800 m², as well as bookshops, bike stores or car dealers, would be allowed to reopen on 20 April, if they followed specified conditions of distancing and hygiene. Similarly, hair dressers could start opening in early May. Cultural events were still banned. By mid-May it was decided that other major restrictions would be lifted by early June. All shops were allowed to open, schools and kindergartens may open in phases, people in care homes are allowed visits from one permanent contact person, outdoor sports without physical contacts could resume and sport leagues, like the German soccer league, could resume behind closed doors, i.e. without spectators. The decision to reopen restaurants was left to the individual federal states, but in general reopened again by mid-May. However, local governments were authorized to re-impose restrictions if the number of infections were exceeding 50 cases per 100,000 inhabitants within 7 days in their respective district/city.

On 3 June, the German government agreed to open borders for international travel starting 15 June 2020. But this was mainly restricted to the other 26 EU member states, the UK and some other European countries. Most of the rest of the world was banned or, at least, people going there should undergo a strict quarantine period of 14 days.

Early September infection figures started rising again. At the beginning, the government was more relaxed claiming that infection hotspots could be relatively easily marked (e.g. wedding parties, church services, returning visitors particularly from the Balkan States) and the routes of transmission could be identified. This attitude changed in October when the government had to admit that the virus was spreading all over the population. Local health offices could no more trace the transmission routes correctly, even if supported by the army. Now COVID-19 was spreading all over the country. But these rising numbers led to some “curious” events within Germany as free travel within the country became restricted. While over summer people were advised to avoid foreign countries for holidays and stay in Germany, many Federal States prohibited to accommodate tourists from regions with high infection rates (i.e. showing more than 50 infections per 100,000 inhabitants over the last 7 days) outside that respective federal state. In most cases the hotel associations went to court and, in general, these bans were lifted.

More and more, the government warned that this situation of exponentially rising infections would get out of hand and the health care system would be in no position anymore to handle all the newly infected persons properly. In the last week of October, the government decided in line with the 16 federal state governments that a second look-down was indispensable[5]. In fact, starting 2 November 2020 a “mild lock-down” lasting for four weeks had been implemented. Actually, it was a repetition of the first round, but some major components were exempted. The major objective is to cut all social and physical contacts to a minimum in order to give the virus no options of spreading anymore. Therefore, restaurants, bars, discos, theaters, cinemas, fitness clubs, etc. had to be closed again. Public and private companies were advised to look for every option to get their staff into home office. However, different to the first round of lock down, it was seen to keep the education system running, i.e. all kindergartens and schools were supposed to stay open. Similarly, the option of visiting relatives and friends in care homes was given. It had been the experience of the first round of lock-down that social contacts had been cut too rigorously and many children would fall out of the education system if not given the option of attending classes, physically. In addition, more shops could stay open, like book shops as well as hair dressers. Likewise, borders were left open in order to keep the economy going.

While social and economic life had to be downsized, the government acted swiftly to balance the economic losses. The most important measures can be summarized as follows: (1) unlimited credit to all companies of all sizes; (2) financial support (subsidies) to small and medium enterprises, artists, private cultural institutions and event companies; (3) expansion of the short-time workers compensation scheme up to 24 months[6]; (4) the suspension of bankruptcy (insolvency) regulations up to the end of the year, (5) a bonus for families with children amounting to €300 per child; and (6) a temporary reduction in VAT from 7% to 5% (basic necessities like food, newspapers, books, et.) and 19% to 16% (all other items, like the purchase of cars, furniture, etc.), respectively for the second half of 2020. The Parliament suspended the constitutionally enshrined debt brake (i.e. public institutions can make new debts up to 3% of the GDP per annum, only) and approved the supplementary government budgets. In total, the government is supposed to spend about €900 billion (i.e. a €750 billion financial aid package at 23 March 2020 and another stimulus package of €130 billion at 29 June 2020) for fighting the economic effects of the virus. So far, many companies have not applied for all that money, yet. Nevertheless, the government is determined to spend more funds if necessary.

In total, compared to neighboring countries Germany is doing relatively well economically. While during the quarter of 2020 GDP declined by 2.2%, there had been a massive fall to about minus 10% during the second quarter. Historically, this was the highest decline in the history of the (West) Germany. The decline was attributed to the collapse in exports as well as the shutdown of whole industries due to health protection measures (almost no business travel, no conferences and fairs, etc.). However, GDP increased during third quarter by 8.2%, again. The major forces for this growth are rising expenditures by private individuals and sharp increases in exports. In addition, companies are investing again, particularly in machines and equipment. So far, the unemployment rate did not rise much due to the payments of the short time workers compensation scheme. In April, about 6 million workers benefited from the scheme. In August 2020 their number stood at about 2.6 million. The official unemployment rate which stood at 4.8% in October 2019 went up to 5.8% in April 2020 and reached its peak in August with 6.4%. In October 2020, the unemployment rate came down to 6.0%.

There is uncertainty about the development in the fourth quarter due to effects of the second (mild) lock-down. In principle, the economic recovery slowed down particularly in those branches which are closely connected with personal and social contacts like (joint) eating-out in restaurants, meetings in bars and discotheques, visiting cultural events (cinemas, theatres, annual fairs and festivals, etc.), tourism (within Germany and abroad) and air travels. These branches will only develop again, once vaccinations will be available on a broader level. With respect to the whole year it is estimated that the GDP will decline by 5.5% which the highest decline since the economic crisis in 2008/9.[7]

IMPACT ON THE FOOD PRODUCTION SECTOR[8]

Farm production[9], particularly crop production is highly nature dependent. It is mainly based on rain fed farming and usually the production cycle lasts from early March up to late October. Therefore, typical labor peaks can be observed. Hence, the support of seasonal workers is highly important to get certain necessary tasks done in time. While the cultivation of major crops is highly mechanized, vegetable and fruit farming, and to some extent viticulture, depend on manual labor particularly during harvesting seasons. Without seasonal workers many of these farms could not survive. On average, about 100,000 foreign workers work on German farms annually, usually for a period of up to 70 days per individual assignment. In general, the majority of the workers come from Romania, Poland and Bulgaria. Usually, they are recruited by special employment companies, get information via Facebook groups, or in most cases, they get informed through mouth to mouth information (“neighbors recruit neighbors”). In many cases, seasonal workers are connected to the same farms over years. The farmers are, in general, providing lodging.

Therefore, the farmers had been heavily affected by the closure of German borders for foreigners, including foreign workers at 24 March 2020. The “normal” working processes could not be followed anymore and, hence, necessary work could not be done at all, or rather not in time. The Farmers’ Union lobbied with the government and it was agreed that during the months of April and May each, 40,000 foreign workers would be accepted or in total 80,000 for the full period. In addition, it was agreed on an extension of the maximum working period per individual worker from 70 to 115 days in order to reduce regular travelling by the workers from their home countries to the working places.

From now on, each farmer who wanted to recruit seasonal workers had to draft a farm concept about how to minimize contacts among workers as well as to the general public in order to avoid the spreading of COVID-19. While in the past housing conditions were not always optimal, farmers had to show that more space per worker had been available in order to ensure the necessary physical distance and to meet all hygienic requirements. In addition, workers could not travel by car or bus as it was the tradition, but had to come by plane. The seasonal workers had to undergo a health check at the airport of arrival and follow a 14-day quarantine period. Hence, farmers had to meet higher travelling and accommodation costs than in the past. On average, it was estimated that costs per individual worker would rise by about €500. Farmers complained that these rising costs were not covered by higher farm prices. However, the government acknowledged this fact to some extent and provided a subsidy of €150 per individual worker.

While in total 80,000 seasonal workers could have come to Germany, just about 39,000 actually did so by early June. The major reasons seem to be that infection rates in the respective home countries were quite high as well, so that willing persons themselves or members of their families were infected and they could not come. In addition, some farmers had problems in ensuring COVID-19-efficient working schedules, i.e. strict distance and hygienic measures. Nevertheless, the immigration of seasonal workers was relaxed once borders within the EU were reopened starting 15 June. Now, they could enter Germany by land, again. However, interested workers from non-EU countries, e.g. from the Balkan States, still had problems in applying for work.

Since the work on the farm is outdoors and the number of seasonal workers on a farm is mostly in the tens and not in the hundreds like in meat industry, only a few outbreaks of COVID-19 could be witnessed on farms. In addition, the fluctuation of the workers is not that high. The living and working conditions of the seasonal workers have a high impact on the spreading of the virus. There had been cases where workers were packed in mini-buses, living areas were too crowded and sanitary facilities were not in a good order. Therefore, farms were not safe from the virus. For example, 174 workers were infected on a vegetable farm in Lower Bavaria by late July as a hygienic and quarantine concept had not been properly implemented. But, in general, the health authorities could act swiftly and put the whole farm and its workers under quarantine. The major reason is the fact that farmers themselves provided accommodation to their workers, so that these places were company-owned flats which legally are part of the farm enterprise[10].

But farmers were not only affected by rising labor costs and a smaller supply of seasonal workers from abroad, due to COVID-19, many farms specialized in vegetable and fruit production faced lower incomes. Due to the shortage of labor, care activities and harvesting could not be managed as smoothly as in the past. Quite a number of these farms reported lower harvests. For example, with respect to asparagus which is usually harvested during the period starting by the end of March up to the end of June (actually overlapping with the total first lock-down period), the total harvest came up to about 100,000 tons which is just about three quarters of the average of the last years. In addition, the marketing channels had to be adjusted. The major part of the harvest had been sold via direct sale to the general public. That channel used to be relevant in the past as well, but this year, the other important channel, i.e. sales to restaurants, was only partly possible due to the lock-down (as shown above). At the beginning of the season, prices were about 10% higher than last year, but then they came down to the same level as last year.

With respect to the production and marketing of berries, the impact of COVID-19 was mixed. While farmers complained about labor shortages and rising labor cost and lower harvest, they were “blessed” by a sharp increase in berry prices. The major reason was not the impact of COVID-19, but a small harvest in the main exporting countries of Central and Eastern Europe. On the other side, a rising demand for fresh berries (soft fruits) could be observed. Hence, the fruit juice industry had to face higher costs. But, in general, the volumes of fruits and vegetables harvested were lower than during previous years, which according to the Farmers’ Union was mainly caused by the effects of COVID-19.