ABSTRACT

Rice, a staple food for Malaysians, necessitates sustainable production to ensure national food security. High-quality, certified rice seeds are crucial for improving yields, adapting to climate change, and addressing pest and disease threats. This narrative delves into Malaysia's rice seed policies, focusing on regulation, distribution, and government initiatives to ensure equitable access to certified seeds. Key players in the seed industry, including DOA, MARDI, IADA, KADA, and MADA, are involved in the seed production chain, from research and development to the production of certified seed. Institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM, and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency contribute to research and development, while the DOA oversees certification. The impact of these policies on farmers, the industry and national food security is significant. Certified seeds offer benefits such as increased yields, improved quality, and reduced vulnerability to pests and diseases. However, challenges such as limited access to certified seeds due to delayed distribution, market dominance by a few players and equitable distribution of improved seed technologies persist. To ensure a sustainable and resilient rice industry, Malaysia must continue to strengthen seed policies, improve distribution channels and promote sustainable agricultural practices. By addressing these challenges and capitalizing on opportunities, Malaysia can secure its food security and economic growth. A robust and sustainable rice sector is essential for the nation's future.

Keywords: Rice seed policies, Rice production, Certified seeds, Food security, Malaysia

INTRODUCTION

For centuries, rice farming has been a fundamental part of Malaysia's culture, economy and food security. The vast green rice fields, spread across the country's different landscapes, have provided food for generations of Malaysians while also shaping their identity and way of life. Rice depends greatly on domestic production. To ensure a stable and secure food supply, Malaysia must address the challenges affecting rice cultivation. Despite these challenges, Malaysia's strong performance in the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2022 is commendable. Ranked 42nd among 113 countries with an overall score of 69.9% (as shown in Table 1), Malaysia particularly excels in affordability, quality, and safety (Economist Impact, 2022a, 2022b). However, maintaining a sustainable rice supply remains a key challenge. While Malaysia has made considerable progress toward achieving food security, ongoing efforts are essential to safeguard the future of rice production.

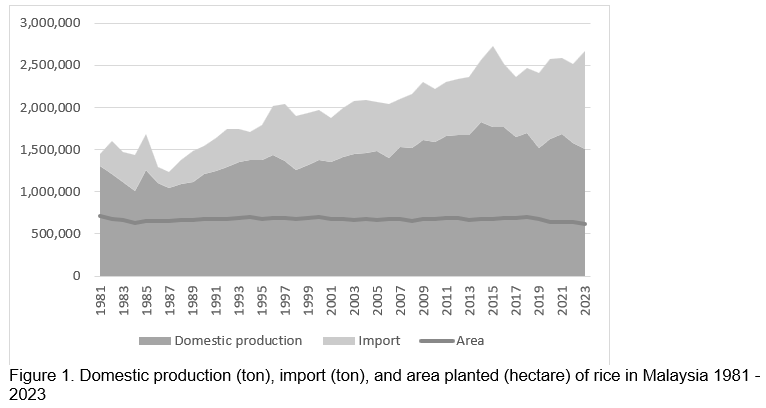

Figure 1 illustrates the long-term trends in domestic production, imports, and cultivated area from 1981 to 2023. Overall, domestic production shows a gradual upward trend, with some fluctuations but without sharp increases. Imports, on the other hand, have expanded significantly over the decades, reflecting growing demand that exceeds domestic supply capacity. Notably, there are visible spikes in imports around the mid-1990s and mid-2010s, coinciding with periods of rising consumption. In contrast, the cultivated area has remained relatively stable throughout the period, with only minor fluctuations, suggesting that land-use expansion has not been the main driver of output growth. Over the years, Malaysia’s rice production has experienced notable fluctuations, as shown in Figure 1 below. Recent data indicate a decline in rice production from 2.44 million metric tons in 2021 to 2.28 million metric tons in 2022, highlighting the urgent need for effective interventions to sustain production levels (MAFS, 2022a). This indicates that while productivity has modestly improved, Malaysia’s increasing reliance on imports highlights structural constraints in domestic production capacity and the inability of land area expansion alone to meet demand. The pattern underscores the importance of technological, policy, and efficiency improvements to reduce import dependency and strengthen food security. The rice sector is pivotal to Malaysia’s agricultural landscape, supporting the livelihoods of thousands of farmers while ensuring the availability of a staple food for the nation. However, the industry faces mounting challenges, including climate change, market instability, soil degradation, and an aging farming population (N. Hashim et al., 2024; Ma and Rahut, 2024; Noor Azmi et al., 2024; Tapsir et al., 2019). Among these, the issue of rice seed quality and accessibility has emerged as a critical bottleneck in enhancing productivity and resilience. High-quality, certified seeds are fundamental to improving yield, adapting to climate variability and mitigating pest and disease pressures. Yet, the seed supply system in Malaysia remains constrained by inefficiencies in distribution, limited farmer access and the dominance of a few key players, which may hinder competition and innovation. This narrative article explores Malaysia's rice policies, with a particular focus on the regulation and distribution of rice seeds. It explores the government’s role in ensuring access to certified seeds. Strengthening the seed supply chain is crucial to revitalizing Malaysia’s rice sector and making it more competitive, resilient, and sustainable amid evolving agricultural challenges.

Table 1: Ranking and score of GFSI (Economist Impact, 2022a, 2022b).

|

INDICATOR

|

Ranking

|

Score (%)

|

|

Affordability

|

30th

|

87.0

|

|

Availability

|

56th

|

59.5

|

|

Quality and safety

|

38th

|

74.7

|

|

Sustainability and adaptation

|

59th

|

53.7

|

|

Overall GFSI

|

42nd

|

69.9

|

VARIETIES OF RICE SEEDS

The predominant variety of rice seeds cultivated worldwide is Oryza Sativa L. also known as Asian rice, a species that underpins much of the global rice industry (Mohidem et al., 2022; Rathna Priya et al., 2019). High-quality rice seeds are crucial for ensuring reliable and high-yielding rice production. To maintain quality standards and prevent the spread of diseases, the Malaysian government prohibits the importation of rice seeds. The presence of diseases in rice seeds can have a severe impact on rice production, threatening both yield and quality. Seed-borne diseases, such as bacterial leaf blight, rice blast and sheath blight, can spread rapidly across rice fields, reducing plant health and productivity. These diseases often lead to stunted growth, lower grain quality and in severe cases, total crop failure (An et al., 2023; Sabri et al., 2023). In recognition of these risks, Malaysia’s government strictly regulates rice seed distribution to ensure that only disease-free, certified seeds are used (Mohamad Noor et al., 2020). This policy of restricting rice seed imports emphasizes Malaysia’s commitment to preserving the integrity of its rice production. By focusing on local seed development, the government ensures that only certified, high-quality varieties adapted to the Malaysian climate and soil conditions are used by farmers. Through government and agricultural agencies, Malaysia has implemented rigorous seed certification programs that promote high standards and verify the quality of domestically produced seeds.

In Malaysia, rice cultivation is divided into two types: field rice, known as wet rice, and hill rice, known as huma rice (MYAgro, 2020). Wet rice is grown in irrigated rice fields primarily located in the fertile plains of Peninsular Malaysia. This type of rice depends on a managed water supply, and the fields are often terraced to retain water efficiently. Meanwhile, huma rice is cultivated on sloping hillsides mainly in Sabah and Sarawak. This traditional method often involves sustainable practices or, in some cases, slash-and-burn techniques, especially among rural farmers in remote areas (Maikol et al., 2023). It relies heavily on rainfall for irrigation, though some areas might use simple irrigation systems to supplement rainfall (Nik Omar et al., 2019). Malaysia boasts a diverse range of locally bred rice seed varieties, including MR219, MR220, MR253, MR263, MR284, MR315 and many more. These varieties have been specifically developed to suit local conditions and taste (Sunian et al., 2019), are carefully monitored by government agencies to identify the most suitable options for high rice yields (Adedoyin et al., 2016), aligning with Malaysia's goal of achieving self-sufficiency in rice production. Based on Table 2, over the past decade, the top three rice seed varieties most commonly chosen by farmers for rice production are MR 220 CL2, MR 219, and MR 297 (MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023). This preference suggests that these varieties deliver benefits such as robust yields, adaptability to various growing conditions, enhanced pest and disease resistance.

A study conducted in Kedah found that the MR297 variety, consistently being favored in each planting season for its strong agronomic traits like high yield, weather tolerance, resilience, and disease resistance, brings tangible benefits, boosting income, reducing input costs, and enhancing well-being (Mohd Zainol et al., 2023). Similarly, the MR219 variety, with its ideal plant height and a high yield potential of 6.0–8.0 ton/ha, has also been a preferred choice among local farmers and has remained popular for over 20 years (Dorairaj and Govender, 2023). Additionally, the MR220-CL2 variety, with its short maturity period and high yield, has also proven valuable, further supporting farmers’ productivity and income (Mohd Zainol et al., 2023). On the other hand, the least commonly used varieties are MR 220 and MR 284 (MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023), due to limitations such as lower yield potential, limited resistance, or specific environmental conditions that don’t align well with farmers' operational conditions. However, farmers still prefer to use locally developed seeds. By prioritizing these seeds, Malaysia can more effectively safeguard its rice crops against pests, diseases, and environmental challenges, while boosting the resilience and sustainability of the rice sector. This strategic approach not only ensures food security but also positions Malaysia as a key player in global food production.

Even though local varieties such as MR219, MR220-CL2, and MR297 possess high yield potential, the national average rice yield in Malaysia remains low due to several interrelated factors. Various studies in Malaysia have identified the causes of this yield gap. For example, a study in the IADA Barat Laut Selangor revealed that while the best farms achieved yields exceeding 7.7 ton/ha, the national average is only about 4.0 ton/ha. This variation is attributed to differences in input use, training, and knowledge exchange among farmers (Terano et al., 2023). Agronomic factors also play a crucial role such as inconsistent water management, suboptimal fertilizer regimes, ineffective pest and disease control and declining soil fertility (Papademetriou, 2000). At the Southeast Asia regional level, yield-gap mapping studies show that on average, the yield gap accounts for about 48 % of the estimated yield potential across rice systems, indicating considerable room for improvement if agricultural practices are enhanced (Yuan et al., 2022). In addition, climate change further negatively impacts rice yields. A study indicates that rising temperatures may significantly suppress rice production in the long run, especially under suboptimal management conditions (Tan et al., 2021). Overall, the gap between varietal potential and realized yield in farmers’ fields demands a holistic approach that is not only focused on varietal breeding but also on strengthening on-farm management, extension services, technical support, adaptation to local agroecological conditions, and climate change strategies.

Table 2. Popular rice seed varieties 2013-2023

|

Year

|

Varieties

|

yield potential (ton / hectare)

|

|

2013

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 220

|

9.6

|

|

2014

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

MR 263

|

7.4

|

|

2015

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 263

|

7.4

|

|

MR 10

|

5.8

|

|

2016

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 263

|

7.4

|

|

MR 269

|

9.9

|

|

2017

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 284

|

9.2

|

|

MR 263

|

7.4

|

|

2018

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

2019

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

2020

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

2021

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

2022

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 219

|

10.5

|

|

2023

|

MR 297

|

8.9

|

|

MR 220 CL2

|

7.7

|

|

MR 269

|

9.9

|

Source: Che Hashim et al., 2022; MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023; Sunain et al., 2022

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES IN RICE SEEDS REGULATION AND CONTROL

In Malaysia, multiple government agencies collaborate closely to regulate and control paddy seeds, enhancing the quality, availability and sustainability of rice production. These agencies forge a structured support system that empowers farmers to access high-quality seeds and maintain competitive yields, even in the face of environmental and market challenges. This robust framework bolsters Malaysia’s rice sector, ensuring a stable rice supply, improving farmers’ livelihoods and promoting Malaysia’s position in the global rice market. The primary government agencies that play crucial roles in regulating and supporting the rice seed industry in Malaysia are the following:

Department of Agriculture (DOA)

DOA is responsible for establishing the Rice Seed Certification Scheme, which certifies the quality of certified rice production in accordance with established conditions and standards (DOA, 2022). The primary objective of this scheme is to guarantee a consistent supply of high-quality seeds derived from pre-approved registered varieties, thus benefiting farmers (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019). The certification process includes rigorous testing, inspection, and quality assurance at various stages to maintain high standards.

Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI)

MARDI plays a pivotal role in developing rice varieties tailored to meet the specific needs of Malaysian farmers and the country’s agricultural goals. The agency’s primary focus in this area is on creating high-yielding, disease-resistant rice strains that are well-suited to local growing conditions and that also improve farmers' livelihoods and resilience (Hussain et al., 2012). Through extensive research and breeding programs, MARDI has successfully developed numerous rice varieties that are widely cultivated and valued for their performance. Examples of these include MR 219, MR 220-CL2, MR 297 and MR 315, which are recognized for their ability to deliver higher yields, improved resistance to pests and diseases and adaptability to varying environmental conditions (Hussain et al., 2012; MARDI, 2024). Beyond variety development, MARDI is also responsible for producing foundation seeds, which are the original, high-quality seeds used in the multiplication process to produce certified seeds for farmers (Wan Mahmood, 2006). By maintaining rigorous standards in the production and distribution of these foundation seeds, MARDI ensures that the certified seeds available in the market consistently exhibit superior quality, high productivity and genetic purity. This process is critical for sustaining the performance of rice crops across the country, as it allows farmers to rely on seeds that meet stringent agricultural standards and deliver optimal results. Recently, MARDI has introduced three new rice varieties in 2024, namely MR326 (Kesidang), MRQ107 and MRQ 111, followed by another three varieties in 2025, namely MRCL3, MRCL4 and MR333. The release of new varieties must ensure superior yield performance or, at the very least, be comparable to the currently preferred varieties cultivated by farmers, while also exhibiting strong resistance to major pests and diseases. MARDI adopts a highly stringent and meticulous selection process prior to the release of any new variety, emphasizing scientific validation over quantity. This cautious approach is intended to safeguard national rice productivity and prevent the unintended consequences of releasing varieties that may not be adopted by farmers or, worse, negatively impact overall rice production.

Regional agencies

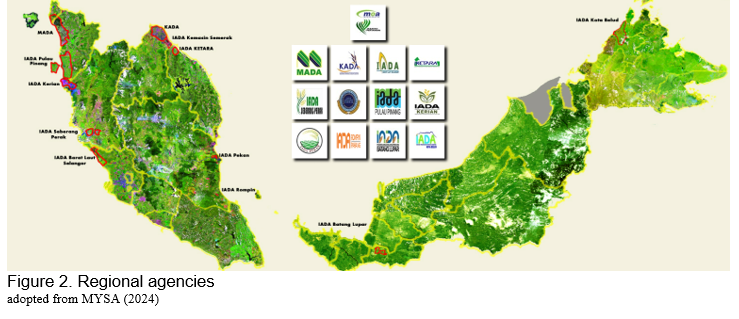

In Malaysia, there are twelve regional agencies operating under the purview of their respective state authorities, including the Integrated Agricultural Development Areas (IADA) such as IADA Barat Laut Selangor, IADA Kerian, IADA Pekan, IADA Pulau Pinang, IADA Rompin, IADA Seberang Perak, IADA Batang Lupar and IADA Kota Belud. Additionally, there are specialized development boards like the Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Kemubu (KADA), KETARA, Kemasin Semerak and the Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Muda (MADA) as illustrated in Figure 2 (MYSA, 2024). These agencies are integral to ensuring the efficient distribution of certified seeds to farmers, especially in regions recognized for high rice production, while also addressing the unique agricultural challenges of their respective localities. Beyond the critical task of seed distribution, these agencies provide a wide array of technical support services to enhance the overall productivity and sustainability of rice cultivation (Rahmat et al., 2019). Their support encompasses crop management strategies, seed selection advice and planting techniques designed to optimize resource utilization and minimize potential losses. These services are particularly essential as farmers contend with changing environmental conditions, such as shifting rainfall patterns, soil degradation, and pest infestations. As localized extensions of national agricultural governance, these regional agencies play a dual role, which is facilitating the implementation of broader government policies on seed regulation and rice development while simultaneously catering to the specific needs of farmers within their regions (IADA Barat Laut Selangor, 2024; KADA, 2020; MADA, 2024). By addressing both macro-level goals and micro-level challenges, they act as a vital link between federal agricultural initiatives and grassroots farming practices. The collective efforts of the regional agencies are pivotal in ensuring the resilience and growth of Malaysia's rice industry. By strengthening the efficiency of seed supply chains, fostering the adoption of best practices, and promoting sustainable farming innovations, these agencies contribute significantly to enhancing the livelihoods of farmers, bolstering food security, and driving the long-term sustainability of the rice sector in Malaysia.

CURRENT POLICIES ON RICE SEEDS DISTRIBUTION AND CONTROL

Certified rice seed production in Malaysia began in 1979, coordinated solely by the DOA through six production plants with a capacity of 24,000 metric tons (ton) annually (MAFS, 2024). However, this production accounted for only 33% of the national demand, estimated at 72,000 ton per year. To address the shortfall, private producers supplemented the seed supply. In 2007, MAFS designated four private seed producers under a “payung” concept to meet quotas for certified seed. With Malaysia’s growing population and increased demand for local rice, certified seed production targets rose to 85,000 ton per year in 2009, with government mandates requiring all farmers to use certified seeds from DOA approved producers. A 2010 reassessment revised the national need to 72,000 ton. Consequently, in 2010, MAFS appointed private companies to manage certified seed production for all farmers fully. Seed production follows several stages according to DOA’s Quality Assurance Procedures before being distributed to farmers. Since 1964, MARDI has led research on new rice varieties, producing 56 varieties, including inbred, hybrid, fragrant, coloured and glutinous types. In 2017, other research institutions, including Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency, also began participating in rice seed research.

Beyond MARDI’s role as the national lead agency for rice varietal development, several research institutions including UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency contribute significantly to Malaysia’s rice seed R&D landscape, each playing distinct and complementary roles. While MARDI leads the national breeding pipeline and oversees the development, testing and release of new rice varieties, the involvement of other research institutions has further strengthened Malaysia’s overall breeding capacity (Dorairaj & Govender, 2023). UPM contributes through its work in molecular genetics and marker-assisted breeding, particularly in improving disease resistance, stress tolerance and productivity traits. UKM enhances Malaysia’s rice genetic diversity by incorporating traits from wild rice species and developing lines with improved yield stability and resilience (Dorairaj & Govender, 2023). Complementing these efforts, the Malaysian Nuclear Agency applies mutation breeding techniques to generate novel genetic variations that can be integrated into national breeding programmes (Hussein et al., 2020). These institutions broaden Malaysia’s scientific capability, diversify breeding approaches and support the development of rice varieties better suited to the country’s diverse agroecological conditions.

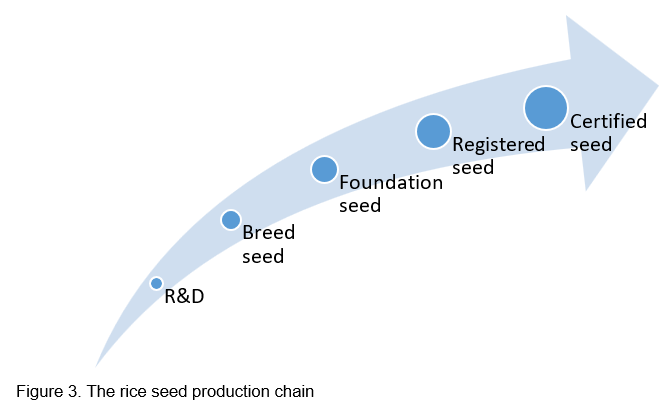

There are three primary types of seed. Foundation seed is the initial generation of seed, produced from breeder seed under strict supervision by research institutions. It is cultivated in controlled conditions to maintain genetic purity and meet specific standards (MAFS, 2022b). Foundation seed serves as the source material for registered seed production. Registered seed is produced using foundation seed. It is cultivated under controlled conditions to ensure genetic purity and meet specified standards (MAFS, 2022b). Registered seed maintains the genetic purity and superior characteristics of foundation seed but is produced on a larger scale to meet the demand for certified seed production. Registered seed is distributed to approved seed growers for further multiplication into certified seed. Certified seed is the final stage, produced using registered seed and intended for direct distribution to farmers. It undergoes rigorous quality control checks to ensure compliance with standards for purity, germination rate and vigor (MAFS, 2022b). Certified seed is marked with an official label to confirm its quality and authenticity, providing farmers with a reliable input for high-yielding and disease-resistant crops.

Figure 3 illustrates the rice seed production chain under the DOA's seed certification scheme. The process begins with research and development by institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency. Breeder seeds are initially produced, followed by foundation seeds, which are then used to generate registered seeds. Private seed producers are responsible for producing registered seeds, which are further multiplied into certified seeds. The DOA closely monitors each stage to ensure adherence to quality standards. Ultimately, certified seeds are distributed to farmers for planting, completing the annual production cycle.

Building upon this foundation, the production of certified rice seed in Malaysia is regulated by the Rice Seed Certification Scheme administered by the Department of Agriculture (DOA), which outlines stringent procedures to ensure varietal integrity, purity, and seed quality (DOA, 2022). Under this system, all seed producers are registered and inspected at multiple stages from pre-planting to post-harvest processing, in accordance with the Prosedur Skim Pengesahan Benih Padi Edisi Ke-5 (DOA, 2022). Each production plot undergoes field inspections at the tillering, booting, flowering, and pre-harvest stages to verify varietal purity and freedom from pest and disease infections. Only lots that meet the prescribed germination rate, moisture content and physical purity standards are certified for sale. Any batches that fail to comply, such as those with low germination rates or pest and disease infestation, are rejected and cannot be marketed as certified seed. The number of registered rice seed producers and their respective production quotas are determined annually by DOA based on national demand and past performance. These quotas are not fixed; they may increase or decrease depending on whether a producer meets quality targets and production volumes. For instance, producers who fail to achieve the assigned quota or whose seed lots are rejected due to quality issues may face a reduction in subsequent allocations, while those maintaining consistent performance may receive an increased quota. This performance-based approach is designed to ensure that only reliable producers contribute to the national certified seed supply (DOA, 2022; MAFS, 2022c).

Meanwhile, the seed producers are involved in both the registered and certified seed production stages. To begin the production cycle, producers must obtain foundation seed from recognized research institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency. Using this foundation seed, producers cultivate registered seed under controlled field conditions that comply with DOA’s quality assurance standards. The registered seed that passes inspection and testing is then multiplied into certified seed, which represents the final stage of the production chain and is distributed to farmers for planting. Through this structured system, DOA ensures that each generation of seed maintains genetic purity, high germination potential and resistance to pests and diseases, essential attributes for sustaining national rice productivity and food security.

PROTECTION MEASURES FOR THE RICE INDUSTRY

While current policies on rice seed distribution and control help ensure that quality seeds reach farmers, other initiatives also play a crucial role within a broader framework designed to support the entire industry. Comprehensive protection strategies, including financial subsidies, price controls, import restrictions, and market support, are essential to maintaining the economic viability of rice farming.

Legislations of the rice industry

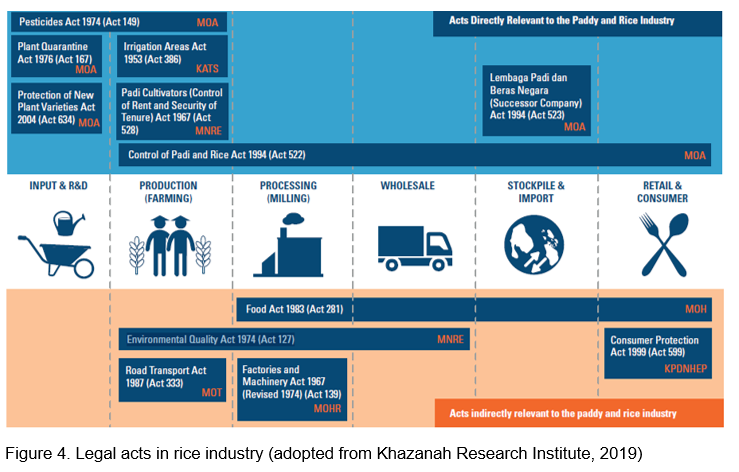

The Malaysian government has implemented several legal frameworks to safeguard the rice industry. The legislation includes the Pesticides Act 1974 (Act 149), the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522), the Lembaga Padi dan Beras Negara (Successor Company) Act 1994 (Act 523) and the Environmental Quality Act 1974 (Act 127). Figure 4, based on the research by the Khazanah Research Institute (2019), provides a visual representation of these government-enacted legal acts. Among these, the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522) is critical, as it governs various aspects of the rice production chain, from farming to processing, wholesaling, stockpiling, importing and retailing. This Act was enacted to ensure regulated production, distribution and sale of paddy and rice, thereby stabilizing this crucial food sector (Law of Malaysia, 2006). Under Act 522, the government has the authority to implement rules that support local farmers, promote fair trade practices and stabilize rice prices. This framework regulates activities such as planting, purchasing, and importing rice, safeguarding local rice production and Malaysia’s food security. A key aspect of this legislation is its role in controlling rice imports, preventing the domestic market from being flooded with foreign rice that could undercut local farmers. By closely monitoring and regulating these processes, the government promotes local production and secures the livelihoods of rice farmers who rely on rice as their primary source of income. To oversee the regulatory functions of the paddy and rice industry, the Control of Paddy and Rice Section, known as Kawalselia, was established under Act 522 (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019).

Currently, the government is revising Act 522 to strengthen the industry and increase the self-sufficiency rate, thereby enhancing national food security resilience. Previously, the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522) did not explicitly classify the act of mixing local rice with imported rice as an offence. This legal gap limited the government’s ability to take enforcement action against such malpractice, which can mislead consumers and distort the local rice market. Consequently, the current amendment seeks to empower authorities to prosecute offenders involved in rice adulteration. The revision is also crucial to strengthen control over fraudulent practices, enhance transparency in the rice supply chain and ensure the quality and authenticity of rice sold in the domestic market.

CHALLENGES OF RICE SEEDS POLICIES ON FARMERS, THE INDUSTRY AND THE NATION’S FOOD SECURITY

Rice seed policies, which emphasize the regulation, distribution, and quality assurance of rice seeds, serve as a cornerstone for improving productivity, enhancing sustainability, and ensuring a stable rice supply to meet national demands. For farmers, access to high-quality, certified seeds is paramount. These seeds, often bred for enhanced resistance to pests, diseases, and adverse weather conditions, enable farmers to mitigate risks and achieve more consistent yields. Government support in seed distribution, particularly for smallholder farmers, alleviates financial burdens and promotes equitable access to improved seed technologies. Consequently, these policies contribute to increased farm-level profitability and improved livelihoods for farming communities. At the industry level, rice seed policies foster innovation and efficiency. The emphasis on certified seeds encourages the adoption of advanced agronomic practices and stimulates the development of new, high-yielding varieties. By ensuring a steady supply of high-quality seeds, these policies minimize production variability, benefiting rice millers and processors. Moreover, the focus on quality standards safeguards the integrity of the rice supply chain, protecting consumers from inferior products. Ultimately, rice seed policies contribute to national food security by ensuring a consistent and adequate rice supply. High-quality seeds directly translate to increased productivity, enabling Malaysia to enhance its rice self-sufficiency level (SSL) and reduce reliance on imports. This reduces vulnerability to global market fluctuations and potential supply disruptions. Additionally, the stability in rice production supported by seed policies allows Malaysia to maintain strategic food stock reserves, providing a crucial buffer against emergencies.

While rice seed policies have undoubtedly contributed to positive outcomes for the Malaysian rice industry, it's important to acknowledge potential negative impacts. One primary concern is farmers’ accessibility to certified seeds, particularly the issue of delayed distribution prior to the commencement of the planting season. In some cases, accessibility challenges arise not due to geographical remoteness, but rather because of limited supply networks, inefficiencies within the supply chain or weak linkages between farmers and licensed seed producers. This challenge is not unique to Malaysia; for example, a study in Sri Lanka found that despite government efforts to supply seeds through formal channels, farmers often relied on seeds from informal sources because certified seeds were unavailable within their communities (Ilangathilaka et al., 2021). Meanwhile, a study in Bangladesh found that farmers, despite limited accessibility, strongly preferred using seeds from formal seed sources. Farmers using formal seed sources yielded 0.03 to 0.15 ton/ha more than those using informal seed sources, highlighting a preference for formal seed sources (Sarkar et al., 2024).

However, the limited variety options available from licensed seed producers further exacerbate this issue. Due to production quotas and prior booking orders by farmers, seed producers often focus on only certain varieties that are in consistent demand. This situation restricts farmers’ ability to switch to alternative varieties when facing new pest and disease outbreaks, thereby increasing vulnerability to crop losses and reducing genetic diversity in cultivation. The dominance of a few key players in the seed market compounds this problem, stifling competition, limiting farmer choices and potentially compromising seed quality. Ensuring equitable access to improved seed technologies, particularly for smallholder farmers, therefore, remains a persistent challenge. Moreover, the intensification of agriculture driven by the focus on high-yielding varieties can lead to increased use of chemical inputs and water resource depletion, contributing to environmental degradation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, rice seed policies in Malaysia are instrumental in enhancing the productivity and sustainability of the rice industry, thereby contributing significantly to national food security. These policies have facilitated the dissemination of high-quality, certified seeds, supported the livelihoods of farmers and stabilized rice production. Strong collaboration between the government and key agencies, such as the Department of Agriculture (DOA), the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI), BERNAS and academic institutions, is crucial for a holistic approach to guide policy implementation, improve seed quality and ensure a resilient and sustainable rice sector for Malaysia's future. Despite these efforts, challenges persist, particularly regarding the accessibility of certified seeds for farmers distant from licensed producers or distributors, the dominance of a few key players in the seed market and equitable access to improved seed technologies. Moreover, the intensification of agriculture, driven by high-yielding varieties, may raise environmental concerns, including increased chemical inputs and water depletion. To address these challenges, comprehensive policy adjustments are necessary, focusing on enhancing seed distribution channels, promoting market competition, and ensuring equitable access to seed technologies for smallholder farmers. Strengthening agricultural extension services and encouraging sustainable farming practices are essential to mitigate the negative environmental impacts of agricultural intensification. By addressing these issues, Malaysia can maximize the benefits of rice seed policies, ensuring a resilient and self-sufficient rice industry that contributes to the nation's long-term food security and agricultural sustainability.

REFERENCES

Adedoyin, A. O., Shamsudin, M. N., Radam, A. and AbdLatif, I. (2016). Effect of Improved High Yielding Rice Variety on Farmers Productivity in Mada, Malaysia. International Journal of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicin, 4(1), 38–52.

An, Y. N., Murugesan, C., Choi, H., Kim, K. D. and Chun, S. C. (2023). Current Studies on Bakanae Disease in Rice: Host Range, Molecular Identification and Disease Management. Mycobiology, 51(4), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/12298093.2023.2241247

DOA. (2022). Prosedur Skim Pengesahan Benih Padi. https://www.doa.gov.my/doa/resources/perkhidmatan/skim_pensijilan/SPBP/prosedur_skim_pengesahan_benih_padi_edisi5_v2.pdf

Dorairaj, D. and Govender, N. T. (2023). Rice And Paddy Industry In Malaysia : Governance And Policies , Research Trends , Technology Adoption And Resilience. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, June, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1093605

Economist Impact. (2022a). Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2022. In The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Economist Impact. (2022b). Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2022: Explore Countries. The Economist Intelligence Unit. https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/explore-countries

Che Hashim, M. F., Haidar, A. N., Nurulhuda, K., Muharam, F. M., Berahim, Z., Zulkafli, Z., Mohd Zad, S. N. and Ismail, M. R. (2022). Physiological and Yield Responses of Five Rice Varieties to Nitrogen Fertilizer Under Farmer’s Field in IADA Ketara, Terengganu, Malaysia. Sains Malaysiana, 51(2), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2022-5102-03

Hashim, N., Ali, M. M., Mahadi, M. R., Abdullah, A. F., Wayayok, A., Mohd Kassim, M. S. and Jamaluddin, A. (2024). Smart Farming For Sustainable Rice Production: An Insight Into Application, Challenge and Future Prospect. Rice Science, 31(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsci.2023.08.004

Hussain, Z. P. M. D., Mokhtar, A., Amzah, B., Hashim, M. and Abd. Ghafar, Mohd. B. (2012). Enam Varieti Padi Popular MARDI. Buletin Teknologi MARDI, 1(10), 1–10.

Hussein, S., Harun, A. R., Simoli, J. M., Abdul Wahab, M. R., Salleh, S., Ahmad, F., Phua, C. K. H., Abdul Rahman, S. A., Ahmad Nazrul, A. W., Nordin, L., Tanaka, A., Ling, A. P. K., Koh, R. Y., Yusop, M. R., Iiyani, A., Kogeethavani, K. R., Yoshihro, H., Aki, K., Noorman, A. M., … Md Hashim, N. (2020). Mutation Breeding of Rice for Sustainable Agriculture in Malaysia. Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia, 30–58. https://www.fnca.mext.go.jp/english/mb/ricesa/pdf/Malaysia.pdf

IADA Barat Laut Selangor. (2024). Fungsi. Portal Rasmi IADA Barat Laut Selangor. https://iadabls.kpkm.gov.my/fungsi

Ilangathilaka, K. A. G., Rupasena, L. P. and Fernando, S. (2021). Factors Affecting Rice Farmers’ Choice of Formal Seed. Applied Economics & Business, 5(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.4038/aeb.v5i1.28

KADA. (2020). Tugas, Fungsi & Objektif. Portal Rasmi Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Kemubu. http://www.kada.gov.my/tugas-fungsi-objektif/

Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). The Status of the Paddy and Rice Industry in Malaysia. In Khazanah Research Institute.

Law of Malaysia. (2006). Act 522: Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Issue January).

Ma, W. and Rahut, D. B. (2024). Climate-Smart Agriculture: Adoption, Impacts and Implications For Sustainable Development. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 29(5), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-024-10139-z

MADA. (2024). Latar Belakang. Portal Rasmi Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Muda. https://www.mada.gov.my/?q=2D00

MAFS. (2018). Perangkaan Agromakanan 2018 (Agrofood Statistics 2018). In Policy and Strategic Planning Division.

MAFS. (2019). Perangkaan Agromakanan (Agrofood Statistics) 2019. In Policy and Strategic Planning Division.

MAFS. (2022a). Malaysia Agrofood in Figures 2022.

MAFS. (2022b). Rice Check Padi. In Department of Agriculture Malaysia (Vol. 1).

MAFS. (2022c). Rice Check Padi. In Department of Agriculture Malaysia (Vol. 1). https://www.doa.gov.my/doa/resources/aktiviti_sumber/sumber_awam/penerbitan/pakej_teknologi/padi/rice_check_padi_2022.pdf

MAFS. (2023). Perangkaan Agromakanan Malaysia (Malaysia Agrofood In Figures) 2023. In Policy and Strategic Planning Division.

MAFS. (2024). KPKM-2024-0002 Laporan Tahunan Jabatan Pertanian 1997.

Maikol, N., Kamarudin, S., Sentian, J., Mohamad Saad, M. Z., Ramlan, N. H., Wan Teng, L. and Ramaiya, S. D. (2023). Hill Rice (Oryza sativa L.): Exploring the Malaysian Knowledge, Perception and Intention to Purchase. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(11), 2444–2452. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v13-i11/19655

MARDI. (2024). Penyelidikan Padi & Beras. Portal MARDI. https://portal.mardi.gov.my/penyelidikan/padi-beras.html

Mohamad Noor, N. H., Ng, B. K. and Abdul Hamid, M. J. (2020). Forging Researchers-Farmers Partnership In Public Social Innovation: A Case Study Of Malaysia’s Agro-Based Public Research Institution. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 23(4), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2019.0119

Mohd Zainol, R., Ashri, N. A., Mohd Rosmi, M. N. and Ibrahim, M. S. N. (2023). The Effect Of Using Quality Rice Seed Varieties On Rice Cultivation Activities. Journal of Food Technology Research, 10(3), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.18488/jftr.v10i3.3486

Mohidem, N. A., Hashim, N., Shamsudin, R. and Man, H. C. (2022). Rice For Food Security: Revisiting Its Production, Diversity, Rice Milling Process and Nutrient Content. Agriculture, 12(741), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060741

MYAgro. (2020). Padi. Bahagian Dasar Dan Perancangan Strategik (DPS). http://portal.myagro.moa.gov.my/ms/doa/paddy/Pages/default.aspx#:~:text=... (bahasa Latin%3A Oryza sativa,tergolong di dalam keluarga Gramineae.

MYSA. (2024). Sistem Maklumat Geospatial Tanaman Padi. MakGeoPadi. https://makgeopadi.mysa.gov.my/index.php

Nik Omar, N. R., Zainol Abidin, A. Z. and Ahmad, B. (2019). Penilaian Ekonomi Sistem Penanaman Titisan Padi Terpilih Secara Aerob Bersama Tanaman Giliran Sorghum. In Economic and Technology Management Review.

Noor Azmi, N. S., Ng, Y. M., Masud, M. M. and Cheng, A. (2024). Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions Of Farmers Towards Urban Agroecology In Malaysia. Heliyon, 10(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33365

Papademetriou, M. K. (2000). Rice Production in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues and Perspectives. In M. K. Papademetriou, F. J. Dent and E. M. Herath (Eds.), Bridging the Rice Yield Gap in the Asia-Pacific Region (pp. 4–25). Food And Agriculture Organization Of The United Nations Regional Office For Asia And The Pacific. http://coin.fao.org/coin-static/cms/media/9/13171760277090/2000_16_high.pdf

Rahmat, S. R., Firdaus, R. B. R., Mohamad Shaharudin, S. and Yee Ling, L. (2019). Leading Key Players And Support System In Malaysian Paddy Production Chain. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 5(1708682). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1708682

Rathna Priya, T. S., Eliazer Nelson, A. R. L., Ravichandran, K. and Antony, U. (2019). Nutritional And Functional Properties Of Coloured Rice Varieties Of South India: A Review. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0017-3

Sabri, S., Ab Wahab, M. Z., Sapak, Z. and Mohd Anuar, I. S. (2023). A Review Of Bacterial Diseases Of Rice And Its Management In Malaysia. Food Research, 7(Suppl. 2), 120–133. https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.7(S2)

Sarkar, M. A. R., Habib, M. A., Sarker, M. R., Rahman, M. M., Alam, S., Manik, M. N. I., Nayak, S. and Bhandari, H. (2024). Rice Farmers’ Preferences For Seed Quality, Packaging and Source: A Study From Northern Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 19(6), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0306059

Sunain, E., Ramli, A., Jamal, M. S., Saidon, S. A. and Kamaruzaman, R. (2022). Pembangunan Varieti Padi Berhasil Tinggi Untuk Kelestarian Pengeluaran Makanan. Buletin Teknologi MARDI, 30, 83–97. http://ebuletin.mardi.gov.my/buletin/30/9-Elixon.pdf

Sunian, E., Jamal, M. S., Saidon, S. A., Abdul Ghaffar, M. B., Mokhtar, A., Kamarruzzaman, R., Ramli, A., Ramachandran, K., Masilamany, D., Misman, S. N., Masarudin, M. F., Mohd Saad, M., Abd Rani, M. N. F., Mohd Yusob, S., Shaari, E. S., Mohd Khari, N. A. and Said, W. (2019). MARDI Sempadan 303 – Varieti Padi Baharu MARDI. Buletin Teknologi MARDI, 17, 155–166. https://doi.org/10.52825/cordi.v1i.397

Tan, B. T., Fam, P. S., Firdaus, R. B. R., Tan, M. L. and Gunaratne, M. S. (2021). Impact of Climate Change on Rice Yield in Malaysia: A Panel Data Analysis. Agricultural, 11(569), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11060569

Tapsir, S., Engku Elini, E. A., Roslina, A., Noorlidawati, A. H., Mohd Hafizudin, Z., Hairazi, R. and Rosnani, H. (2019). Food Security And Sustainability: Malaysia Agenda. Malays. Appl. Biol, 48(3), 1–9.

Terano, R., Ramil, N. N. R., Sharifuddin, J. and Ali, F. (2023). Determinants of Rice Yield Gap in IADA Barat Laut Selangor, Malaysia. ISSAAS International Scientific Congress and General Meeting, 125. https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122430/records/66d56f89028a912... the government has established,extended to other granary areas.

Wan Mahmood, W. J. (2006). Developing Malaysian Seed Industry: Prospects and Challenges. Economic and Technology Management Review, 1(1), 51–59.

Yuan, S., Stuart, A. M., Laborte, A. G., Rattalino Edreira, J. I., Dobermann, A., Kien, L. V. N., Thúy, L. T., Paothong, K., Traesang, P., Tint, K. M., San, S. S., Villafuerte, M. Q., Quicho, E. D., Pame, A. R. P., Then, R., Flor, R. J., Thon, N., Agus, F., Agustiani, N., … Grassini, P. (2022). Southeast Asia Must Narrow Down the Yield Gap to Continue to be a Major Rice Bowl. Nature Food, 3(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00477-z

Malaysia's Rice Landscape: Sustainable Rice Production and Food Security through Rice Seed Policies

ABSTRACT

Rice, a staple food for Malaysians, necessitates sustainable production to ensure national food security. High-quality, certified rice seeds are crucial for improving yields, adapting to climate change, and addressing pest and disease threats. This narrative delves into Malaysia's rice seed policies, focusing on regulation, distribution, and government initiatives to ensure equitable access to certified seeds. Key players in the seed industry, including DOA, MARDI, IADA, KADA, and MADA, are involved in the seed production chain, from research and development to the production of certified seed. Institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM, and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency contribute to research and development, while the DOA oversees certification. The impact of these policies on farmers, the industry and national food security is significant. Certified seeds offer benefits such as increased yields, improved quality, and reduced vulnerability to pests and diseases. However, challenges such as limited access to certified seeds due to delayed distribution, market dominance by a few players and equitable distribution of improved seed technologies persist. To ensure a sustainable and resilient rice industry, Malaysia must continue to strengthen seed policies, improve distribution channels and promote sustainable agricultural practices. By addressing these challenges and capitalizing on opportunities, Malaysia can secure its food security and economic growth. A robust and sustainable rice sector is essential for the nation's future.

Keywords: Rice seed policies, Rice production, Certified seeds, Food security, Malaysia

INTRODUCTION

For centuries, rice farming has been a fundamental part of Malaysia's culture, economy and food security. The vast green rice fields, spread across the country's different landscapes, have provided food for generations of Malaysians while also shaping their identity and way of life. Rice depends greatly on domestic production. To ensure a stable and secure food supply, Malaysia must address the challenges affecting rice cultivation. Despite these challenges, Malaysia's strong performance in the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2022 is commendable. Ranked 42nd among 113 countries with an overall score of 69.9% (as shown in Table 1), Malaysia particularly excels in affordability, quality, and safety (Economist Impact, 2022a, 2022b). However, maintaining a sustainable rice supply remains a key challenge. While Malaysia has made considerable progress toward achieving food security, ongoing efforts are essential to safeguard the future of rice production.

Figure 1 illustrates the long-term trends in domestic production, imports, and cultivated area from 1981 to 2023. Overall, domestic production shows a gradual upward trend, with some fluctuations but without sharp increases. Imports, on the other hand, have expanded significantly over the decades, reflecting growing demand that exceeds domestic supply capacity. Notably, there are visible spikes in imports around the mid-1990s and mid-2010s, coinciding with periods of rising consumption. In contrast, the cultivated area has remained relatively stable throughout the period, with only minor fluctuations, suggesting that land-use expansion has not been the main driver of output growth. Over the years, Malaysia’s rice production has experienced notable fluctuations, as shown in Figure 1 below. Recent data indicate a decline in rice production from 2.44 million metric tons in 2021 to 2.28 million metric tons in 2022, highlighting the urgent need for effective interventions to sustain production levels (MAFS, 2022a). This indicates that while productivity has modestly improved, Malaysia’s increasing reliance on imports highlights structural constraints in domestic production capacity and the inability of land area expansion alone to meet demand. The pattern underscores the importance of technological, policy, and efficiency improvements to reduce import dependency and strengthen food security. The rice sector is pivotal to Malaysia’s agricultural landscape, supporting the livelihoods of thousands of farmers while ensuring the availability of a staple food for the nation. However, the industry faces mounting challenges, including climate change, market instability, soil degradation, and an aging farming population (N. Hashim et al., 2024; Ma and Rahut, 2024; Noor Azmi et al., 2024; Tapsir et al., 2019). Among these, the issue of rice seed quality and accessibility has emerged as a critical bottleneck in enhancing productivity and resilience. High-quality, certified seeds are fundamental to improving yield, adapting to climate variability and mitigating pest and disease pressures. Yet, the seed supply system in Malaysia remains constrained by inefficiencies in distribution, limited farmer access and the dominance of a few key players, which may hinder competition and innovation. This narrative article explores Malaysia's rice policies, with a particular focus on the regulation and distribution of rice seeds. It explores the government’s role in ensuring access to certified seeds. Strengthening the seed supply chain is crucial to revitalizing Malaysia’s rice sector and making it more competitive, resilient, and sustainable amid evolving agricultural challenges.

Table 1: Ranking and score of GFSI (Economist Impact, 2022a, 2022b).

INDICATOR

Ranking

Score (%)

Affordability

30th

87.0

Availability

56th

59.5

Quality and safety

38th

74.7

Sustainability and adaptation

59th

53.7

Overall GFSI

42nd

69.9

VARIETIES OF RICE SEEDS

The predominant variety of rice seeds cultivated worldwide is Oryza Sativa L. also known as Asian rice, a species that underpins much of the global rice industry (Mohidem et al., 2022; Rathna Priya et al., 2019). High-quality rice seeds are crucial for ensuring reliable and high-yielding rice production. To maintain quality standards and prevent the spread of diseases, the Malaysian government prohibits the importation of rice seeds. The presence of diseases in rice seeds can have a severe impact on rice production, threatening both yield and quality. Seed-borne diseases, such as bacterial leaf blight, rice blast and sheath blight, can spread rapidly across rice fields, reducing plant health and productivity. These diseases often lead to stunted growth, lower grain quality and in severe cases, total crop failure (An et al., 2023; Sabri et al., 2023). In recognition of these risks, Malaysia’s government strictly regulates rice seed distribution to ensure that only disease-free, certified seeds are used (Mohamad Noor et al., 2020). This policy of restricting rice seed imports emphasizes Malaysia’s commitment to preserving the integrity of its rice production. By focusing on local seed development, the government ensures that only certified, high-quality varieties adapted to the Malaysian climate and soil conditions are used by farmers. Through government and agricultural agencies, Malaysia has implemented rigorous seed certification programs that promote high standards and verify the quality of domestically produced seeds.

In Malaysia, rice cultivation is divided into two types: field rice, known as wet rice, and hill rice, known as huma rice (MYAgro, 2020). Wet rice is grown in irrigated rice fields primarily located in the fertile plains of Peninsular Malaysia. This type of rice depends on a managed water supply, and the fields are often terraced to retain water efficiently. Meanwhile, huma rice is cultivated on sloping hillsides mainly in Sabah and Sarawak. This traditional method often involves sustainable practices or, in some cases, slash-and-burn techniques, especially among rural farmers in remote areas (Maikol et al., 2023). It relies heavily on rainfall for irrigation, though some areas might use simple irrigation systems to supplement rainfall (Nik Omar et al., 2019). Malaysia boasts a diverse range of locally bred rice seed varieties, including MR219, MR220, MR253, MR263, MR284, MR315 and many more. These varieties have been specifically developed to suit local conditions and taste (Sunian et al., 2019), are carefully monitored by government agencies to identify the most suitable options for high rice yields (Adedoyin et al., 2016), aligning with Malaysia's goal of achieving self-sufficiency in rice production. Based on Table 2, over the past decade, the top three rice seed varieties most commonly chosen by farmers for rice production are MR 220 CL2, MR 219, and MR 297 (MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023). This preference suggests that these varieties deliver benefits such as robust yields, adaptability to various growing conditions, enhanced pest and disease resistance.

A study conducted in Kedah found that the MR297 variety, consistently being favored in each planting season for its strong agronomic traits like high yield, weather tolerance, resilience, and disease resistance, brings tangible benefits, boosting income, reducing input costs, and enhancing well-being (Mohd Zainol et al., 2023). Similarly, the MR219 variety, with its ideal plant height and a high yield potential of 6.0–8.0 ton/ha, has also been a preferred choice among local farmers and has remained popular for over 20 years (Dorairaj and Govender, 2023). Additionally, the MR220-CL2 variety, with its short maturity period and high yield, has also proven valuable, further supporting farmers’ productivity and income (Mohd Zainol et al., 2023). On the other hand, the least commonly used varieties are MR 220 and MR 284 (MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023), due to limitations such as lower yield potential, limited resistance, or specific environmental conditions that don’t align well with farmers' operational conditions. However, farmers still prefer to use locally developed seeds. By prioritizing these seeds, Malaysia can more effectively safeguard its rice crops against pests, diseases, and environmental challenges, while boosting the resilience and sustainability of the rice sector. This strategic approach not only ensures food security but also positions Malaysia as a key player in global food production.

Even though local varieties such as MR219, MR220-CL2, and MR297 possess high yield potential, the national average rice yield in Malaysia remains low due to several interrelated factors. Various studies in Malaysia have identified the causes of this yield gap. For example, a study in the IADA Barat Laut Selangor revealed that while the best farms achieved yields exceeding 7.7 ton/ha, the national average is only about 4.0 ton/ha. This variation is attributed to differences in input use, training, and knowledge exchange among farmers (Terano et al., 2023). Agronomic factors also play a crucial role such as inconsistent water management, suboptimal fertilizer regimes, ineffective pest and disease control and declining soil fertility (Papademetriou, 2000). At the Southeast Asia regional level, yield-gap mapping studies show that on average, the yield gap accounts for about 48 % of the estimated yield potential across rice systems, indicating considerable room for improvement if agricultural practices are enhanced (Yuan et al., 2022). In addition, climate change further negatively impacts rice yields. A study indicates that rising temperatures may significantly suppress rice production in the long run, especially under suboptimal management conditions (Tan et al., 2021). Overall, the gap between varietal potential and realized yield in farmers’ fields demands a holistic approach that is not only focused on varietal breeding but also on strengthening on-farm management, extension services, technical support, adaptation to local agroecological conditions, and climate change strategies.

Table 2. Popular rice seed varieties 2013-2023

Year

Varieties

yield potential (ton / hectare)

2013

MR 219

10.5

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 220

9.6

2014

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 219

10.5

MR 263

7.4

2015

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 263

7.4

MR 10

5.8

2016

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 263

7.4

MR 269

9.9

2017

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 284

9.2

MR 263

7.4

2018

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 297

8.9

MR 219

10.5

2019

MR 297

8.9

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 219

10.5

2020

MR 297

8.9

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 219

10.5

2021

MR 297

8.9

MR 219

10.5

MR 220 CL2

7.7

2022

MR 297

8.9

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 219

10.5

2023

MR 297

8.9

MR 220 CL2

7.7

MR 269

9.9

Source: Che Hashim et al., 2022; MAFS, 2018, 2019, 2023; Sunain et al., 2022

GOVERNMENT AGENCIES IN RICE SEEDS REGULATION AND CONTROL

In Malaysia, multiple government agencies collaborate closely to regulate and control paddy seeds, enhancing the quality, availability and sustainability of rice production. These agencies forge a structured support system that empowers farmers to access high-quality seeds and maintain competitive yields, even in the face of environmental and market challenges. This robust framework bolsters Malaysia’s rice sector, ensuring a stable rice supply, improving farmers’ livelihoods and promoting Malaysia’s position in the global rice market. The primary government agencies that play crucial roles in regulating and supporting the rice seed industry in Malaysia are the following:

Department of Agriculture (DOA)

DOA is responsible for establishing the Rice Seed Certification Scheme, which certifies the quality of certified rice production in accordance with established conditions and standards (DOA, 2022). The primary objective of this scheme is to guarantee a consistent supply of high-quality seeds derived from pre-approved registered varieties, thus benefiting farmers (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019). The certification process includes rigorous testing, inspection, and quality assurance at various stages to maintain high standards.

Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI)

MARDI plays a pivotal role in developing rice varieties tailored to meet the specific needs of Malaysian farmers and the country’s agricultural goals. The agency’s primary focus in this area is on creating high-yielding, disease-resistant rice strains that are well-suited to local growing conditions and that also improve farmers' livelihoods and resilience (Hussain et al., 2012). Through extensive research and breeding programs, MARDI has successfully developed numerous rice varieties that are widely cultivated and valued for their performance. Examples of these include MR 219, MR 220-CL2, MR 297 and MR 315, which are recognized for their ability to deliver higher yields, improved resistance to pests and diseases and adaptability to varying environmental conditions (Hussain et al., 2012; MARDI, 2024). Beyond variety development, MARDI is also responsible for producing foundation seeds, which are the original, high-quality seeds used in the multiplication process to produce certified seeds for farmers (Wan Mahmood, 2006). By maintaining rigorous standards in the production and distribution of these foundation seeds, MARDI ensures that the certified seeds available in the market consistently exhibit superior quality, high productivity and genetic purity. This process is critical for sustaining the performance of rice crops across the country, as it allows farmers to rely on seeds that meet stringent agricultural standards and deliver optimal results. Recently, MARDI has introduced three new rice varieties in 2024, namely MR326 (Kesidang), MRQ107 and MRQ 111, followed by another three varieties in 2025, namely MRCL3, MRCL4 and MR333. The release of new varieties must ensure superior yield performance or, at the very least, be comparable to the currently preferred varieties cultivated by farmers, while also exhibiting strong resistance to major pests and diseases. MARDI adopts a highly stringent and meticulous selection process prior to the release of any new variety, emphasizing scientific validation over quantity. This cautious approach is intended to safeguard national rice productivity and prevent the unintended consequences of releasing varieties that may not be adopted by farmers or, worse, negatively impact overall rice production.

Regional agencies

In Malaysia, there are twelve regional agencies operating under the purview of their respective state authorities, including the Integrated Agricultural Development Areas (IADA) such as IADA Barat Laut Selangor, IADA Kerian, IADA Pekan, IADA Pulau Pinang, IADA Rompin, IADA Seberang Perak, IADA Batang Lupar and IADA Kota Belud. Additionally, there are specialized development boards like the Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Kemubu (KADA), KETARA, Kemasin Semerak and the Lembaga Kemajuan Pertanian Muda (MADA) as illustrated in Figure 2 (MYSA, 2024). These agencies are integral to ensuring the efficient distribution of certified seeds to farmers, especially in regions recognized for high rice production, while also addressing the unique agricultural challenges of their respective localities. Beyond the critical task of seed distribution, these agencies provide a wide array of technical support services to enhance the overall productivity and sustainability of rice cultivation (Rahmat et al., 2019). Their support encompasses crop management strategies, seed selection advice and planting techniques designed to optimize resource utilization and minimize potential losses. These services are particularly essential as farmers contend with changing environmental conditions, such as shifting rainfall patterns, soil degradation, and pest infestations. As localized extensions of national agricultural governance, these regional agencies play a dual role, which is facilitating the implementation of broader government policies on seed regulation and rice development while simultaneously catering to the specific needs of farmers within their regions (IADA Barat Laut Selangor, 2024; KADA, 2020; MADA, 2024). By addressing both macro-level goals and micro-level challenges, they act as a vital link between federal agricultural initiatives and grassroots farming practices. The collective efforts of the regional agencies are pivotal in ensuring the resilience and growth of Malaysia's rice industry. By strengthening the efficiency of seed supply chains, fostering the adoption of best practices, and promoting sustainable farming innovations, these agencies contribute significantly to enhancing the livelihoods of farmers, bolstering food security, and driving the long-term sustainability of the rice sector in Malaysia.

CURRENT POLICIES ON RICE SEEDS DISTRIBUTION AND CONTROL

Certified rice seed production in Malaysia began in 1979, coordinated solely by the DOA through six production plants with a capacity of 24,000 metric tons (ton) annually (MAFS, 2024). However, this production accounted for only 33% of the national demand, estimated at 72,000 ton per year. To address the shortfall, private producers supplemented the seed supply. In 2007, MAFS designated four private seed producers under a “payung” concept to meet quotas for certified seed. With Malaysia’s growing population and increased demand for local rice, certified seed production targets rose to 85,000 ton per year in 2009, with government mandates requiring all farmers to use certified seeds from DOA approved producers. A 2010 reassessment revised the national need to 72,000 ton. Consequently, in 2010, MAFS appointed private companies to manage certified seed production for all farmers fully. Seed production follows several stages according to DOA’s Quality Assurance Procedures before being distributed to farmers. Since 1964, MARDI has led research on new rice varieties, producing 56 varieties, including inbred, hybrid, fragrant, coloured and glutinous types. In 2017, other research institutions, including Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency, also began participating in rice seed research.

Beyond MARDI’s role as the national lead agency for rice varietal development, several research institutions including UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency contribute significantly to Malaysia’s rice seed R&D landscape, each playing distinct and complementary roles. While MARDI leads the national breeding pipeline and oversees the development, testing and release of new rice varieties, the involvement of other research institutions has further strengthened Malaysia’s overall breeding capacity (Dorairaj & Govender, 2023). UPM contributes through its work in molecular genetics and marker-assisted breeding, particularly in improving disease resistance, stress tolerance and productivity traits. UKM enhances Malaysia’s rice genetic diversity by incorporating traits from wild rice species and developing lines with improved yield stability and resilience (Dorairaj & Govender, 2023). Complementing these efforts, the Malaysian Nuclear Agency applies mutation breeding techniques to generate novel genetic variations that can be integrated into national breeding programmes (Hussein et al., 2020). These institutions broaden Malaysia’s scientific capability, diversify breeding approaches and support the development of rice varieties better suited to the country’s diverse agroecological conditions.

There are three primary types of seed. Foundation seed is the initial generation of seed, produced from breeder seed under strict supervision by research institutions. It is cultivated in controlled conditions to maintain genetic purity and meet specific standards (MAFS, 2022b). Foundation seed serves as the source material for registered seed production. Registered seed is produced using foundation seed. It is cultivated under controlled conditions to ensure genetic purity and meet specified standards (MAFS, 2022b). Registered seed maintains the genetic purity and superior characteristics of foundation seed but is produced on a larger scale to meet the demand for certified seed production. Registered seed is distributed to approved seed growers for further multiplication into certified seed. Certified seed is the final stage, produced using registered seed and intended for direct distribution to farmers. It undergoes rigorous quality control checks to ensure compliance with standards for purity, germination rate and vigor (MAFS, 2022b). Certified seed is marked with an official label to confirm its quality and authenticity, providing farmers with a reliable input for high-yielding and disease-resistant crops.

Figure 3 illustrates the rice seed production chain under the DOA's seed certification scheme. The process begins with research and development by institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency. Breeder seeds are initially produced, followed by foundation seeds, which are then used to generate registered seeds. Private seed producers are responsible for producing registered seeds, which are further multiplied into certified seeds. The DOA closely monitors each stage to ensure adherence to quality standards. Ultimately, certified seeds are distributed to farmers for planting, completing the annual production cycle.

Building upon this foundation, the production of certified rice seed in Malaysia is regulated by the Rice Seed Certification Scheme administered by the Department of Agriculture (DOA), which outlines stringent procedures to ensure varietal integrity, purity, and seed quality (DOA, 2022). Under this system, all seed producers are registered and inspected at multiple stages from pre-planting to post-harvest processing, in accordance with the Prosedur Skim Pengesahan Benih Padi Edisi Ke-5 (DOA, 2022). Each production plot undergoes field inspections at the tillering, booting, flowering, and pre-harvest stages to verify varietal purity and freedom from pest and disease infections. Only lots that meet the prescribed germination rate, moisture content and physical purity standards are certified for sale. Any batches that fail to comply, such as those with low germination rates or pest and disease infestation, are rejected and cannot be marketed as certified seed. The number of registered rice seed producers and their respective production quotas are determined annually by DOA based on national demand and past performance. These quotas are not fixed; they may increase or decrease depending on whether a producer meets quality targets and production volumes. For instance, producers who fail to achieve the assigned quota or whose seed lots are rejected due to quality issues may face a reduction in subsequent allocations, while those maintaining consistent performance may receive an increased quota. This performance-based approach is designed to ensure that only reliable producers contribute to the national certified seed supply (DOA, 2022; MAFS, 2022c).

Meanwhile, the seed producers are involved in both the registered and certified seed production stages. To begin the production cycle, producers must obtain foundation seed from recognized research institutions such as MARDI, UPM, UKM and the Malaysian Nuclear Agency. Using this foundation seed, producers cultivate registered seed under controlled field conditions that comply with DOA’s quality assurance standards. The registered seed that passes inspection and testing is then multiplied into certified seed, which represents the final stage of the production chain and is distributed to farmers for planting. Through this structured system, DOA ensures that each generation of seed maintains genetic purity, high germination potential and resistance to pests and diseases, essential attributes for sustaining national rice productivity and food security.

PROTECTION MEASURES FOR THE RICE INDUSTRY

While current policies on rice seed distribution and control help ensure that quality seeds reach farmers, other initiatives also play a crucial role within a broader framework designed to support the entire industry. Comprehensive protection strategies, including financial subsidies, price controls, import restrictions, and market support, are essential to maintaining the economic viability of rice farming.

Legislations of the rice industry

The Malaysian government has implemented several legal frameworks to safeguard the rice industry. The legislation includes the Pesticides Act 1974 (Act 149), the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522), the Lembaga Padi dan Beras Negara (Successor Company) Act 1994 (Act 523) and the Environmental Quality Act 1974 (Act 127). Figure 4, based on the research by the Khazanah Research Institute (2019), provides a visual representation of these government-enacted legal acts. Among these, the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522) is critical, as it governs various aspects of the rice production chain, from farming to processing, wholesaling, stockpiling, importing and retailing. This Act was enacted to ensure regulated production, distribution and sale of paddy and rice, thereby stabilizing this crucial food sector (Law of Malaysia, 2006). Under Act 522, the government has the authority to implement rules that support local farmers, promote fair trade practices and stabilize rice prices. This framework regulates activities such as planting, purchasing, and importing rice, safeguarding local rice production and Malaysia’s food security. A key aspect of this legislation is its role in controlling rice imports, preventing the domestic market from being flooded with foreign rice that could undercut local farmers. By closely monitoring and regulating these processes, the government promotes local production and secures the livelihoods of rice farmers who rely on rice as their primary source of income. To oversee the regulatory functions of the paddy and rice industry, the Control of Paddy and Rice Section, known as Kawalselia, was established under Act 522 (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019).

Currently, the government is revising Act 522 to strengthen the industry and increase the self-sufficiency rate, thereby enhancing national food security resilience. Previously, the Control of Padi and Rice Act 1994 (Act 522) did not explicitly classify the act of mixing local rice with imported rice as an offence. This legal gap limited the government’s ability to take enforcement action against such malpractice, which can mislead consumers and distort the local rice market. Consequently, the current amendment seeks to empower authorities to prosecute offenders involved in rice adulteration. The revision is also crucial to strengthen control over fraudulent practices, enhance transparency in the rice supply chain and ensure the quality and authenticity of rice sold in the domestic market.

CHALLENGES OF RICE SEEDS POLICIES ON FARMERS, THE INDUSTRY AND THE NATION’S FOOD SECURITY

Rice seed policies, which emphasize the regulation, distribution, and quality assurance of rice seeds, serve as a cornerstone for improving productivity, enhancing sustainability, and ensuring a stable rice supply to meet national demands. For farmers, access to high-quality, certified seeds is paramount. These seeds, often bred for enhanced resistance to pests, diseases, and adverse weather conditions, enable farmers to mitigate risks and achieve more consistent yields. Government support in seed distribution, particularly for smallholder farmers, alleviates financial burdens and promotes equitable access to improved seed technologies. Consequently, these policies contribute to increased farm-level profitability and improved livelihoods for farming communities. At the industry level, rice seed policies foster innovation and efficiency. The emphasis on certified seeds encourages the adoption of advanced agronomic practices and stimulates the development of new, high-yielding varieties. By ensuring a steady supply of high-quality seeds, these policies minimize production variability, benefiting rice millers and processors. Moreover, the focus on quality standards safeguards the integrity of the rice supply chain, protecting consumers from inferior products. Ultimately, rice seed policies contribute to national food security by ensuring a consistent and adequate rice supply. High-quality seeds directly translate to increased productivity, enabling Malaysia to enhance its rice self-sufficiency level (SSL) and reduce reliance on imports. This reduces vulnerability to global market fluctuations and potential supply disruptions. Additionally, the stability in rice production supported by seed policies allows Malaysia to maintain strategic food stock reserves, providing a crucial buffer against emergencies.

While rice seed policies have undoubtedly contributed to positive outcomes for the Malaysian rice industry, it's important to acknowledge potential negative impacts. One primary concern is farmers’ accessibility to certified seeds, particularly the issue of delayed distribution prior to the commencement of the planting season. In some cases, accessibility challenges arise not due to geographical remoteness, but rather because of limited supply networks, inefficiencies within the supply chain or weak linkages between farmers and licensed seed producers. This challenge is not unique to Malaysia; for example, a study in Sri Lanka found that despite government efforts to supply seeds through formal channels, farmers often relied on seeds from informal sources because certified seeds were unavailable within their communities (Ilangathilaka et al., 2021). Meanwhile, a study in Bangladesh found that farmers, despite limited accessibility, strongly preferred using seeds from formal seed sources. Farmers using formal seed sources yielded 0.03 to 0.15 ton/ha more than those using informal seed sources, highlighting a preference for formal seed sources (Sarkar et al., 2024).

However, the limited variety options available from licensed seed producers further exacerbate this issue. Due to production quotas and prior booking orders by farmers, seed producers often focus on only certain varieties that are in consistent demand. This situation restricts farmers’ ability to switch to alternative varieties when facing new pest and disease outbreaks, thereby increasing vulnerability to crop losses and reducing genetic diversity in cultivation. The dominance of a few key players in the seed market compounds this problem, stifling competition, limiting farmer choices and potentially compromising seed quality. Ensuring equitable access to improved seed technologies, particularly for smallholder farmers, therefore, remains a persistent challenge. Moreover, the intensification of agriculture driven by the focus on high-yielding varieties can lead to increased use of chemical inputs and water resource depletion, contributing to environmental degradation.

CONCLUSION