ABSTRACT

The transformation of Indonesia’s food system requires the strategic integration of policy coherence, innovation, and entrepreneurship to create a future that is inclusive, competitive, and sustainable. This article develops an analytical framework based on Schumpeterian innovation, endogenous growth theory, institutional economics, and food systems thinking to examine Indonesia’s trajectory of agricultural transformation. Insights from the Golden Indonesia Vision 2045 and the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2025–2029 highlight food sovereignty, digitalization, green innovation, and cooperative-based entrepreneurship as national priorities. Systemic transformation arises from the interplay of coherent regulation, adaptive innovation, and inclusive entrepreneurship—including cooperative-led models such as the Red-White Cooperative, which demonstrates the importance of transparent governance and collective action in empowering smallholders and strengthening value chain integration. Despite persistent challenges such as fragmented governance and uneven digital capacity, recent post-2024 reforms reflect Indonesia’s decisive reorientation toward sustainability-oriented, innovation-driven, and institutionally coherent food system transformation. This study concludes that cooperative-led entrepreneurship represents a viable pathway for emerging economies seeking to balance modernization with social justice.

Keywords: Food system transformation, Agricultural innovation, Entrepreneurship ecosystems, Cooperative-based development, Institutional economics, and Koperasi Merah Putih

INTRODUCTION

Transforming food systems has become a central concern in both academic discourse and policy debates, reflecting their role in ensuring food security, sustaining rural livelihoods, and responding to climate and market shocks (FAO, 2021; HLPE, 2020). Food systems are increasingly understood not only as agricultural production activities but as integrated socio-economic and ecological systems that determine the availability, accessibility, affordability, and sustainability of food.

For Indonesia, a country of more than 280 million people, the urgency of food system transformation is particularly pronounced. Agriculture continues to play a critical role in the national economy, contributing 12.4% of gross domestic product and employing approximately 29% of the labor force (Badan Pusat Statistik [BPS], 2023). Yet the sector faces persistent structural constraints: declining land productivity, reliance on smallholder farming, fragmented supply chains, and vulnerability to global trade fluctuations. These challenges are exacerbated by climate change, urbanization, and demographic shifts.

Historically, Indonesia’s agricultural policy has prioritized productivity and self-sufficiency, with rice and other staple foods at the center of national strategies. While this approach secured short-term food availability, it has also generated long-term vulnerabilities, including environmental degradation, inefficiencies in smallholder production, and weak integration of farmers into higher-value markets (Hidayat, 2022). Recognizing these limitations, the government has reoriented its development trajectory. The Golden Indonesia Vision 2045 positions agriculture and food security as pillars of inclusive and sustainable growth, while the Indonesia National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) of 2025–2029 emphasizes food sovereignty, downstream agro-industrial development, green innovation, and entrepreneurship-led rural transformation (Bappenas, 2024).

In this context, three interdependent dimensions—policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship—are critical to driving systemic change. Policy provides the institutional framework that defines incentives and governance structures; innovation introduces new technologies, practices, and organizational models that improve efficiency and resilience; and entrepreneurship operationalizes these innovations, translating them into economic and social value. Together, these elements form the foundation for transforming Indonesia’s food system in alignment with national strategies and global sustainability agendas.

The purpose of this article is threefold. First, it develops an integrative theoretical framework that combines Schumpeterian innovation, endogenous growth, institutional economics, food systems thinking, and contemporary entrepreneurship theories. Second, it critically reviews Indonesia’s policy and regulatory frameworks related to food and agriculture. Third, it examines practical illustrations of innovation and entrepreneurship in Indonesia’s agriculture, drawing comparative insights from Japan’s cooperative systems and South Korea’s smart farm policies. By doing so, the article contributes to both academic debate and policy practice, offering a multidimensional analysis of how policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship interact to shape Indonesia’s food system transformation.

At the global level, Indonesia’s food system transformation also aligns with international commitments such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). The country’s emphasis on food sovereignty, sustainability, and rural entrepreneurship resonates with the priorities articulated during the UN Food Systems Summit (2021), which called for integrated approaches to ensure equitable access to healthy diets, strengthen climate resilience, and empower small-scale producers. Positioning Indonesia’s strategy within this global discourse highlights not only its domestic significance but also its contribution to advancing collective international goals for sustainable and inclusive food systems.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The transformation of national food systems requires a multidimensional theoretical foundation that recognizes innovation, entrepreneurship, and institutions as interconnected drivers of change. This study adopts an integrative framework that combines classical economic theories with contemporary entrepreneurship perspectives to analyze Indonesia’s agricultural transformation.

Innovation, creative destruction, and agricultural change

Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction explains how economic development occurs through cycles of innovation that disrupt existing structures while creating new opportunities (Schumpeter, 1934/2008). In agriculture, these innovations include mechanization, digital farming, biotechnology, and renewable energy from agricultural waste. Such changes not only enhance productivity but also reshape labor markets, trade flows, and value chains. In Indonesia, the adoption of mechanized rice farming has reduced demand for manual labor while increasing yields, producing both efficiency gains and social adjustment challenges. Policymakers must therefore complement technological innovation with social protection, labor reskilling, and inclusive business models (Dosi & Nelson, 2010).

Endogenous growth, human capital, and entrepreneurship

In Indonesian agriculture, entrepreneurship manifests in youth-led start-ups, digital agribusiness platforms, and agro-tourism enterprises that expand value chains and diversify rural incomes. Empirical studies further show that entrepreneurial orientation and personality traits strongly influence the performance of farmers and agribusiness ventures in Indonesia (Pambudy, 2016; Haliq, Pambudy, Burhanuddin, & Alfikri, 2018). Government instruments such as Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR, People’s Business Credit) exemplify policy mechanisms that stimulate entrepreneurial activity, thereby reinforcing growth trajectories (Audretsch & Thurik, 2001).

Institutional economics and policy coherence

Institutional economics underscores the role of formal rules, informal norms, and enforcement mechanisms in shaping economic behavior (North, 1990). In agriculture, coherent institutions are needed to address market failures such as credit constraints, environmental externalities, and information asymmetries. Indonesia’s governance landscape, however, is often marked by fragmented authority, with overlapping mandates across ministries and local governments. This can result in inconsistent land use policies, subsidy allocations, and trade regulations. Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) theory of collective action highlights the importance of local institutions in managing shared resources such as irrigation systems, while Rodrik (2004) stresses the role of coordinated industrial policy. These insights reinforce the need for institutional coherence to enable innovation and entrepreneurship to flourish in Indonesia’s food system.

Food systems approach: Beyond productivity

Recent scholarship calls for a food systems approach that extends beyond narrow productivity gains to address nutrition, equity, and sustainability (FAO, 2021; HLPE, 2020). This approach situates agriculture within broader socio-economic and ecological contexts, linking production, distribution, consumption, and environmental stewardship. For Indonesia, applying a food systems perspective means aligning national strategies such as the RPJMN 2025–2029 and Visi Indonesia Emas 2045 (Golden Indonesia Vision 2045) with climate-smart agriculture, circular economy practices, and rural–urban integration.

Contemporary entrepreneurship theories: Effectuation, ecosystems, and sustainability

Contemporary theories of entrepreneurship provide further insights into transformation in practice. Effectuation theory emphasizes how entrepreneurs act under uncertainty by leveraging available resources and partnerships rather than relying solely on predictive strategies (Sarasvathy, 2001). This resonates with smallholders in Indonesia who often adapt innovatively within resource-constrained environments.

The entrepreneurial ecosystems perspective highlights how entrepreneurial success depends not only on individual initiative but also on the quality of surrounding institutions, infrastructure, networks, and culture (Stam, 2015). In Indonesia, uneven access to finance, limited rural infrastructure, and fragmented extension services reveal the challenges of building a supportive ecosystem for agripreneurs.

Sustainable entrepreneurship theory integrates ecological and social goals into entrepreneurial practice, recognizing that new ventures can simultaneously create economic value and address sustainability challenges (Dean & McMullen, 2007). In Indonesia, initiatives such as livestock waste-to-energy projects, organic certification schemes, and agroforestry-based enterprises illustrate how sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship contributes to climate resilience and resource efficiency.

Integrative conceptual lens

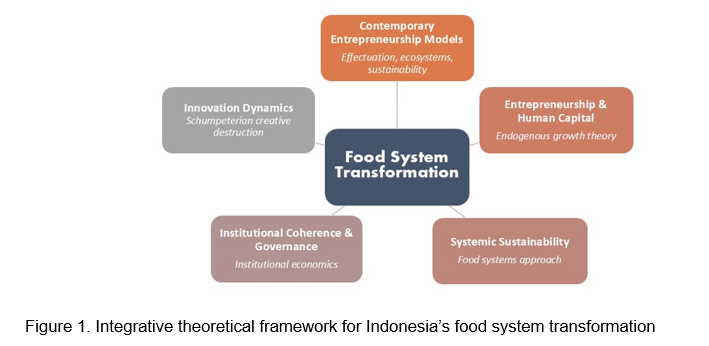

Bringing these perspectives together, this study views food system transformation as a process shaped by five conceptual pillars:

- Innovation dynamics (Schumpeterian creative destruction);

- Entrepreneurship and human capital (endogenous growth theory);

- Institutional coherence and governance (institutional economics);

- Systemic sustainability imperatives (food systems approach); and

- Adaptive entrepreneurship models (effectuation, entrepreneurial ecosystems, sustainable entrepreneurship).

Figure 1 illustrates how these pillars interact to drive Indonesia’s food system transformation. Each contributes directly to transformation outcomes, while the central focus highlights food system transformation as the overarching goal. The framework synthesizes insights from Schumpeter (1934/2008), Lucas (1988), Romer (1990), North (1990), Ostrom (1990), FAO (2021), HLPE (2020), Sarasvathy (2001), Stam (2015), and Dean & McMullen (2007).

By explicitly integrating these theoretical perspectives, the framework not only provides an analytical foundation for assessing Indonesia’s policy and entrepreneurial practices but also situates the country within broader regional and global debates on sustainable food system transformation.

POLICY REVIEW: INDONESIA’S AGENDAS AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS

Indonesia’s food system transformation agenda is increasingly defined by the country’s long-term vision documents and a suite of newly enacted regulatory frameworks that collectively establish the direction of reform. Law No. 59/2024 on the National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN 2025–2045) sets out the strategic framework for achieving the Visi Indonesia Emas 2045 (Golden Indonesia Vision 2045). Agriculture and food sovereignty are explicitly positioned as key pillars of inclusive growth, while sustainability, innovation, and entrepreneurship are embedded as cross-cutting priorities that must be operationalized across all development sectors. Building upon this macro-level foundation, Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN 2025–2029) translates these long-term aspirations into actionable five-year strategies. The RPJMN emphasizes food sovereignty, green innovation, bioeconomy development, and entrepreneurship-led rural transformation, thereby marking a decisive shift away from input-driven productivity policies toward systemic approaches to food system transformation.

Recent regulations illustrate the government’s attempt to balance innovation, governance, and sustainability imperatives in a rapidly changing global context. Government Regulation (PP) No. 19/2024 on the Supervision of Genetically Engineered Food revises oversight mechanisms for genetically modified products, reflecting Schumpeter’s (1934/2008) notion of creative destruction: biotechnology generates opportunities for productivity and resilience, but it also introduces governance and safety risks that require robust institutional safeguards (North, 1990). Complementing this, Presidential Decree No. 81/2024 on Food Diversification and Biofortification mandates the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) to spearhead research on biofortified crops and diversification of staple foods, underscoring the role of knowledge, research capacity, and human capital in advancing food security, consistent with the insights of endogenous growth theory (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1990).

Sustainability and circular economy principles have also been institutionalized through the Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan (2024), which is embedded within the RPJMN 2025–2029. This framework integrates resource efficiency, waste valorization, and climate-smart practices into agricultural and industrial development strategies. Within this policy context, the bioeconomy perspective is increasingly emphasized, where agriculture is viewed not only as a source of food but also as a provider of renewable biological resources such as biomass, organic fertilizers, and bio-based materials. Recent discussions highlight that Indonesia’s circular economy agenda is inseparable from the development of a bioeconomy that links agriculture, industry, and sustainability transitions (Goutama, 2025).

Its design reflects the food systems approach advocated by FAO (2021) and HLPE (2020), which emphasizes the interconnections between production, distribution, consumption, and environmental stewardship, while also resonating with sustainable entrepreneurship theory (Dean & McMullen, 2007). By embedding circular economy and bioeconomy principles into national planning, Indonesia addresses long-term ecological constraints, reduces systemic risks associated with resource depletion, and simultaneously creates new entrepreneurial opportunities in agri-food processing and waste-to-value ventures.

Despite these policy advances, significant challenges remain. Policy fragmentation persists, with overlapping mandates across ministries, agencies, and local governments, often resulting in inconsistent land-use policies, subsidy allocations, and trade regulations. The integration of sustainability objectives with entrepreneurship promotion is still in its formative stage, while rural disparities in infrastructure, access to finance, and digital literacy risk limiting the effective implementation of these regulatory frameworks. Nevertheless, the post-2024 policy landscape demonstrates a clear strategic commitment by the Indonesian government to move toward systemic food system transformation, one that balances governance, innovation, and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship within a coherent institutional framework.

The regulatory landscape for Indonesia’s food and agriculture sectors has thus undergone substantial reform since 2024, reflecting the government’s strategic shift toward food system transformation. As outlined in Law No. 59/2024 on the RPJPN 2025–2045 and Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the RPJMN 2025–2029, food sovereignty, innovation, sustainability, and entrepreneurship are identified as key pillars of national development. These overarching frameworks are complemented by a diverse set of sectoral regulations issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs, the Ministry of Trade, and the National Food Agency (NFA), each targeting specific aspects of production, distribution, safety, and market governance. Together, these instruments provide not only a legal foundation but also an enabling environment for innovation and entrepreneurship within Indonesia’s food system.

Table 1 summarizes the key post-2024 regulations, outlining their core content, their relevance to entrepreneurship and innovation, and their contribution to food system transformation (FST). The table also highlights the degree to which each regulatory instrument supports FST objectives. For example, NFA Regulation No. 2/2024 on Fresh Food Standards reinforces consumer trust through higher quality and safety requirements; the Ministry of Agriculture Regulation No. 3/2024 on Agricultural Area Development advances cluster-based entrepreneurship; and the Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan institutionalizes resource efficiency and climate-smart practices. By systematically mapping these regulations against the dimensions of entrepreneurship, innovation, and systemic transformation, the analysis underscores how Indonesia’s post-2024 regulatory reforms are converging toward a holistic and future-oriented food system agenda.

Table 1. Post-2024 policy and regulatory frameworks for food system transformation in Indonesia

|

Regulation / Framework

|

Content / Focus

|

Relevance to entrepreneurship

|

Relevance to innovation

|

Contribution to food system transformation

|

|

Law No. 59/2024 on the National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN 2025–2045)

|

Establishes Golden Indonesia Vision 2045; emphasizes food sovereignty, green economy, and innovation.

|

Promotes rural entrepreneurship, SMEs, and cooperatives as drivers of inclusive growth (RPJPN, Ch. IV – Economic Transformation).

|

Frames innovation in green technology and digitalization as strategic enablers (RPJPN, Ch. III – Science, Technology, and Innovation).

|

Provides the macro framework for shifting food systems beyond productivity toward sustainability and inclusivity.

|

|

Regulation No. 19/2024 on the Supervision of Genetically Engineered Food (BPOM)

|

Updates oversight of GMO food for governance and safety.

|

Opens potential for enterprises in seeds and biotech food products.

|

Sets biosafety requirements and innovation standards (Reg. 19/2024, Ch. II – Requirements for GE Food).

|

Ensures the safe integration of biotech into the food system under national regulatory frameworks.

|

|

Presidential Decree No. 81/2024 on Food Diversification and Biofortification

|

Assigns BRIN to lead research on biofortified crops and the diversification of staple foods.

|

Encourages agri-preneurship in local food diversification.

|

Advances R&D in biofortified crops and nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

|

Enhances diversification and nutrition within food systems.

|

|

Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan (integrated into RPJMN 2025–2029)

|

Institutionalizes resource efficiency, waste valorization, and climate-smart practices.

|

Generates opportunities in bioenergy, organic fertilizer, and green agribusiness (Roadmap, Priority 3 – Agriculture & Food Systems).

|

Promotes innovation in renewable energy and eco-efficient farming.

|

Embeds circular practices and climate-smart sustainability into food systems.

|

|

Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN 2025–2029)

|

Operationalizes medium-term strategies: food sovereignty, rural entrepreneurship, innovation, and green transformation.

|

Expands entrepreneurship ecosystems through finance, incubation, and rural enterprises (RPJMN 2025–2029, Ch. V – Economic Development).

|

Integrates digitalization, smart farming, and green innovation (RPJMN 2025–2029, Ch. III – Innovation & Sustainability).

|

Blueprint for implementing food system transformation across sectors.

|

|

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 3/2024 on Agricultural Area Development

|

Defines criteria and management of agricultural zones, integration of commodities, farmer groups, and marketing.

|

Strengthens agripreneurship through cluster-based farming and collective marketing.

|

Facilitates adoption of modern technology and integrated value chains.

|

Supports efficiency and inclusivity by organizing agriculture spatially as part of FST.

|

|

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 13/2024 on Fresh Fruit Bunch (FFB) Trade for Palm Oil

|

Regulates fair trade between smallholders (plasma/independent) and palm oil mills.

|

Enhances bargaining power and market access for smallholders.

|

Introduces transparent pricing and digital record-keeping.

|

Builds more equitable and accountable supply chains within FST.

|

|

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 1/2024 and Ministerial Decree No. 249/2024 on Fertilizer Subsidies & e-RDKK

|

Expands subsidized fertilizer allocation; enforces digital farmer registration (e-RDKK).

|

Strengthens farmer organizations and cooperative entrepreneurship.

|

Promotes innovation in digital targeting of input distribution.

|

Increases smallholder productivity and transparency in input use.

|

|

Minister of Cooperatives & SMEs Regulation No. 2/2024 on Cooperative Accounting Standards

|

Standardizes cooperative financial reporting, audit, and transparency.

|

Strengthens cooperative-based entrepreneurship through better governance.

|

Encourages innovation in cooperative financial management systems.

|

Enhances cooperatives’ role as inclusive actors in food system distribution and processing.

|

|

Minister of Trade Regulation No. 8/2024 (Amendment to Import Regulation)

|

Revises rules on import of goods to support supply chain flexibility.

|

Expands opportunities for businesses to access imported inputs.

|

Enables diffusion of foreign technologies and agricultural machinery.

|

Stabilizes food and input availability, supporting resilience in FST.

|

|

Minister of Trade Regulation No. 18/2024 on Palm Cooking Oil (MinyakKita)

|

Regulates palm cooking oil packaging, branding, and supply chain under “MinyakKita.”

|

Expands entrepreneurship opportunities in local packaging and distribution.

|

Supports innovation in branding, marketing, and traceability.

|

Ensures the affordability and availability of a staple product in food systems.

|

|

National Food Agency (NFA) Regulation No. 2/2024 on Fresh Food Standards

|

Governs the safety, quality, nutrition, labeling, and advertising of fresh food.

|

Encourages agribusinesses and SMEs to meet higher market standards.

|

Stimulates product innovation in fresh and functional foods.

|

Reinforces food safety and consumer trust, a cornerstone of FST.

|

INNOVATION AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN INDONESIA’S AGRICULTURE

Innovation and entrepreneurship in Indonesia’s agricultural sector manifest in diverse and evolving forms, spanning digital start-ups, cooperative-led ventures, financial innovations, and integrated agribusiness models. Digital aquaculture platforms such as eFishery exemplify how IoT-based solutions can reduce production costs, optimize feed efficiency, and simultaneously connect farmers with financing institutions and buyers. Similarly, fresh produce e-commerce initiatives such as Sayurbox demonstrate how shortening supply chains can increase farmers' margins, reduce transaction costs, and enhance consumer access to affordable, traceable, and high-quality products. Agri-fintech mechanisms like Crowde further expand financial inclusion by mobilizing capital for smallholders who are often excluded from formal credit systems, thereby addressing one of the most persistent barriers to small-scale agricultural investment. Downstream branding initiatives in coffee, represented by Kopi Kenangan, illustrate the importance of value-added processing and innovative marketing strategies in repositioning local commodities within highly competitive domestic and global markets.

Beyond individual cases, broader systemic approaches to agrifood entrepreneurship are also emerging. Fisheries export platforms such as Aruna directly connect small-scale fishers with global buyers, bypassing traditional intermediaries and integrating producers more effectively into international value chains. Circular economy ventures such as Rekosistem illustrate how agricultural and food waste can be valorized into renewable energy, organic fertilizers, and other marketable by-products, embedding sustainability principles directly into the production cycle. Integrated agribusinesses such as Greenfields in the dairy sector demonstrate that Indonesian firms can compete with multinational corporations while simultaneously strengthening domestic supply chains, generating value addition, and enhancing rural employment. These systemic models show how innovation is not limited to technological solutions but also involves institutional, organizational, and market-based arrangements that reshape the structure of agrifood systems.

Importantly, cooperative-led models highlight the role of institutional innovation in distributing entrepreneurial benefits more equitably. Koperasi Merah Putih (Red-White Cooperative) represents a significant example of how collective action, transparent governance, and coordinated production can stabilize incomes, strengthen farmer bargaining power, and integrate smallholders into more formalized and structured markets. By contrast with start-ups or corporate agribusinesses that often concentrate risks and benefits in narrow segments of the chain, cooperative-based entrepreneurship spreads both risks and returns across members, making participation more inclusive and resilient. The cooperative model, therefore, complements technology-driven innovations by ensuring that systemic transformation is embedded in social solidarity and collective organization, which are particularly relevant in Indonesia’s rural economy.

Taken together, these illustrative cases confirm that agricultural entrepreneurship in Indonesia extends far beyond the establishment of individual firms. It encompasses a broad spectrum of mechanisms, including financial instruments, organizational models, cooperative institutions, and sustainability-oriented practices. Empirical research on smallholder farmers in West Java reinforces this point, showing how entrepreneurial orientation and individual traits directly shape business performance in livestock and poultry farming (Pambudy, 2016; Haliq et al., 2018).

These developments collectively reinforce Schumpeter’s (1934/2008) notion of creative destruction, whereby new organizational and technological forms displace outdated and inefficient structures. They also align with contemporary theories of entrepreneurship: effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001), which explains adaptive decision-making under uncertainty; entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam, 2015), which highlight the importance of institutional, infrastructural, and cultural environments; sustainable entrepreneurship (Dean & McMullen, 2007), which integrates ecological and social concerns into business practice; and institutional entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006), which emphasizes the transformation of rules and norms through entrepreneurial agency.

More broadly, the Indonesian experience demonstrates that agricultural innovation is heterogeneous, dynamic, and deeply embedded within social and institutional contexts. It contributes not only to improvements in productivity and competitiveness but also to the broader agenda of building inclusive, resilient, and sustainability-oriented food systems. By linking digital technology, financial innovation, cooperative organization, and circular economy principles, Indonesia provides an instructive case for other emerging economies seeking to balance modernization with equity and long-term sustainability in their agricultural transformations.

Red-White Cooperatives: Integrating policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship for food system transformation

Indonesia’s agricultural transformation illustrates that policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship are mutually reinforcing rather than isolated drivers of systemic change. Policy establishes the institutional environment by defining rules, incentives, and priorities; innovation provides the technological, organizational, and managerial mechanisms required for productivity, resilience, and sustainability; and entrepreneurship operationalizes these innovations, translating them into market-oriented practices that deliver tangible economic and social benefits. This tripartite interplay reflects Indonesia’s broader vision for food system transformation, in which policy sets the stage, innovation supplies the tools, and entrepreneurship generates outcomes at the grassroots level.

The RPJPN 2025–2045 and RPJMN 2025–2029 outline overarching goals—food sovereignty, economic inclusivity, and environmental sustainability—that guide sectoral strategies and policy instruments. Within this framework, the Koperasi Merah Putih (Red-White Cooperative) serves as a prominent example of how entrepreneurial initiatives can align with national development priorities. The cooperative is an official program of President Prabowo Subianto’s administration, based on Presidential Instruction No. 9/2025, and was formally inaugurated in July 2025. By consolidating farmer production, enforcing transparent financial governance, and formalizing partnerships with downstream buyers, the Red-White Cooperative has raised farmers' incomes, stabilized local food supplies, and generated new rural economic opportunities. Its trajectory illustrates the principle of institutional entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006), demonstrating that innovation arises not only from the deployment of advanced technologies but also from collective organization, transparent management, and supportive governance structures.

The legal foundation of the Red-White Cooperative is firmly anchored in Indonesia’s broader regulatory framework. The Cooperative Law (Law No. 25/1992) defines cooperatives as business entities based on mutual cooperation and democratic economic principles, granting them legitimacy to organize production, distribution, and finance collectively. In the agricultural domain, the Food Law (Law No. 18/2012) affirms food sovereignty, security, and safety as state priorities and underscores the role of farmer institutions in achieving them. The Village Law (Law No. 6/2014) further strengthens rural-based institutions by enabling cooperatives to access state funds and integrate their activities into local development initiatives. Complementing these statutory foundations, the National Medium-Term Development Plan (Presidential Regulation No. 18/2020 and its successor, RPJMN 2025–2029) explicitly promotes cooperative-based agribusiness and digital agriculture as instruments of inclusive growth. Taken together, these legal instruments embody the constitutional mandate of Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution, which requires that the national economy be organized as a common endeavor founded on the principle of kinship.

Against this backdrop, the Red-White Cooperative exemplifies how inclusive entrepreneurship can embody regulatory priorities while addressing systemic challenges in the food system. Unlike start-ups or corporate agribusinesses, which often concentrate both risks and benefits in narrow segments of the value chain, the cooperative redistributes risks and benefits more equitably among its members. This institutional design strengthens bargaining power, ensures smallholder participation in value chains, and enhances the resilience of rural economies. By linking policy support with grassroots innovation, the cooperative builds a bridge between national visions and local realities, translating long-term development strategies into concrete improvements in livelihoods.

The Red-White Cooperative thus represents a uniquely Indonesian pathway to food system transformation, one that merges entrepreneurial dynamism with collective solidarity to advance productivity, resilience, and inclusivity simultaneously. Indonesia’s experience demonstrates that coherent policy frameworks, applied innovation, and inclusive entrepreneurship—when embedded in cooperative institutions—can jointly drive systemic transformation in the food sector. The case of the Red-White Cooperative underscores the transformative potential of legally grounded cooperative models within Indonesia’s institutional frameworks as a national strategy that combines technological dynamism, collective action, and social justice. In this sense, the cooperative serves not only as an instrument of agricultural modernization but also as a vehicle for fulfilling constitutional and developmental mandates of equity, sustainability, and national resilience.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Strengthening cooperative-based entrepreneurship is essential, as cooperatives offer a scalable institutional model for organizing smallholders and integrating them into modern value chains. The Red-White Cooperative demonstrates how transparent governance and coordinated production can translate national policy priorities into improved farmer livelihoods. Accordingly, national strategies such as the RPJPN 2025–2045 and RPJMN 2025–2029 should continue positioning cooperatives as key vehicles for inclusive and innovation-driven agricultural modernization.

At the same time, Indonesia’s trajectory highlights broader implications for policy design and implementation. Food system transformation cannot be understood as a purely technical endeavor focused on increasing yields or improving efficiency. Instead, it is fundamentally an institutional and governance process that requires policy coherence, cross-sectoral coordination, and alignment between state planning and entrepreneurial practice. Fragmented or overlapping regulations risk hindering innovation diffusion, discouraging private investment, and limiting the success of entrepreneurial ventures. Conversely, coordinated policies that link financial instruments, digital platforms, and cooperative structures can create the conditions for systemic change by lowering transaction costs, broadening participation, and enhancing the resilience of agri-food systems.

Indonesia’s reforms also carry lessons for other emerging economies that face similar challenges of balancing modernization with equity. The Indonesian experience demonstrates how grassroots institutions—when effectively supported by national development planning—can function as powerful agents of systemic transformation. Anchoring agricultural modernization in cooperative solidarity, rather than relying exclusively on corporate agribusinesses or high-growth start-ups, offers an alternative pathway that prioritizes inclusivity without sacrificing competitiveness. By embedding entrepreneurship in collective arrangements and aligning these arrangements with long-term policy goals, Indonesia demonstrates how agricultural transformation can advance simultaneously along economic, social, and ecological dimensions.

Finally, these insights imply that future policy recommendations must prioritize three interrelated areas. First, governance coherence: ensuring that mandates across ministries and local governments are harmonized to avoid fragmentation and regulatory contradictions. Second, entrepreneurship ecosystems: providing targeted support for digital infrastructure, financial inclusion, and innovation hubs in rural areas to foster bottom-up entrepreneurial activity. Third, sustainability integration: embedding circular-economy practices, climate-smart agriculture, and social safeguards across all major food and agricultural policies. Taken together, these priorities would not only strengthen Indonesia’s capacity to achieve its national development targets but also position the country as a regional leader in advancing sustainable and inclusive food system transformation.

CONCLUSION

Indonesia’s food system transformation reflects a multidimensional process in which policy coherence, innovation, and entrepreneurship reinforce each other to generate structural change. National strategies, notably the RPJPN 2025–2045 and RPJMN 2025–2029, have placed food sovereignty, sustainability, and rural entrepreneurship at the center of economic transformation, providing a solid institutional foundation for long-term development. These frameworks mark a shift away from productivity-centric approaches toward a more systemic understanding of food systems that integrates governance reform, human capital development, and sustainability-oriented innovation.

Within this evolving policy landscape, cooperative-based models such as the Red-White Cooperative demonstrate how institutional innovation can translate national priorities into practical outcomes for smallholders. By organizing production, improving transparency, and strengthening collective bargaining power, cooperatives illustrate how entrepreneurial mechanisms can be embedded in socially inclusive structures. This reinforces the principle that transformation is not driven by technology alone but by the institutional arrangements that enable farmers to participate meaningfully in modern value chains.

At the same time, Indonesia’s experience reveals persistent constraints that must be addressed to sustain long-term progress. Governance fragmentation, asymmetric digital literacy, uneven access to finance, and rural–urban disparities continue to limit the diffusion of innovation and the scaling of entrepreneurship-based solutions. These challenges underscore the need for continuous policy refinement, inter-ministerial coordination, and strengthened local institutional capacity to ensure that transformation benefits are distributed equitably across regions and communities.

Taken together, the findings of this study suggest that Indonesia’s emerging model of food system transformation offers a hybrid pathway that merges technological dynamism with social justice. It demonstrates that modernization in agriculture can be compatible with inclusivity when innovation is embedded within coherent institutions and collective entrepreneurship. As Indonesia continues implementing post-2024 reforms, the alignment of national development planning with grassroots institutional innovation will be critical to enhancing resilience, strengthening food sovereignty, and positioning Indonesia as a leader in sustainable and equitable food system transformation in the region.

REFERENCES

Audretsch, D. B., & Thurik, A. R. (2001). What’s new about the new economy? Sources of growth in the managed and entrepreneurial economies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(1), 267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/10.1.267

Dean, T. J., & McMullen, J. S. (2007). Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(1), 50–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.09.003

Dosi, G., & Nelson, R. R. (2010). Technical change and industrial dynamics as evolutionary processes. In B. H. Hall & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of innovation (Vol. 1, pp. 51–127). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

FAO. (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021: Transforming food systems for food security, improved nutrition and affordable healthy diets for all. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4474en

Goutama, M. W. (2025). Green arms race: Indonesia’s critical minerals and its sprint for renewable energy sovereignty [Working paper]. ResearchGate.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Government Regulation No. 19 of 2024 on the supervision of genetically engineered food. Jakarta: State Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Presidential Decree No. 81 of 2024 on food diversification and biofortification. Jakarta: State Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 3 of 2024 on agricultural area development. Jakarta: Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 13 of 2024 on fresh fruit bunch (FFB) trade for palm oil. Jakarta: Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 1 of 2024 and Ministerial Decree No. 249 of 2024 on fertilizer subsidies and e-RDKK. Jakarta: Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs Regulation No. 2 of 2024 on cooperative accounting standards. Jakarta: Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Trade Regulation No. 8 of 2024 on import regulation (amendment). Jakarta: Ministry of Trade of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). Minister of Trade Regulation No. 18 of 2024 on palm cooking oil (MinyakKita). Jakarta: Ministry of Trade of the Republic of Indonesia.

Government of Indonesia. (2024). National Food Agency (NFA) Regulation No. 2 of 2024 on fresh food standards. Jakarta: National Food Agency of the Republic of Indonesia.

Haliq, I., Pambudy, R., Burhanuddin, & Alfikri, S. (2018). Influence of entrepreneurship orientation on business performance of broiler husbandry in the partnership and the independent scheme in Bogor. International Journal of Agriculture System, 6(1), 25–64.

Hidayat, A. (2022). Agricultural policy and food security in Indonesia. Journal of Agricultural Policy Studies, 15(2), 87–104.

HLPE. (2020). Food security and nutrition: Building a global narrative towards 2030 (HLPE Report 15). Rome: High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition, Committee on World Food Security.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pambudy, R. (2016). The influence of personality traits on the entrepreneurship of sheep farmers in Garut Regency. American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences, 26(3), 42–64.

Rodrik, D. (2004). Industrial policy for the twenty-first century. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4767. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/259121

Schumpeter, J. A. (2008). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle (U. Backhaus, Ed.; reprint of 1934 ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

Policy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Agriculture: Driving Indonesia’s Food System Transformation

ABSTRACT

The transformation of Indonesia’s food system requires the strategic integration of policy coherence, innovation, and entrepreneurship to create a future that is inclusive, competitive, and sustainable. This article develops an analytical framework based on Schumpeterian innovation, endogenous growth theory, institutional economics, and food systems thinking to examine Indonesia’s trajectory of agricultural transformation. Insights from the Golden Indonesia Vision 2045 and the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2025–2029 highlight food sovereignty, digitalization, green innovation, and cooperative-based entrepreneurship as national priorities. Systemic transformation arises from the interplay of coherent regulation, adaptive innovation, and inclusive entrepreneurship—including cooperative-led models such as the Red-White Cooperative, which demonstrates the importance of transparent governance and collective action in empowering smallholders and strengthening value chain integration. Despite persistent challenges such as fragmented governance and uneven digital capacity, recent post-2024 reforms reflect Indonesia’s decisive reorientation toward sustainability-oriented, innovation-driven, and institutionally coherent food system transformation. This study concludes that cooperative-led entrepreneurship represents a viable pathway for emerging economies seeking to balance modernization with social justice.

Keywords: Food system transformation, Agricultural innovation, Entrepreneurship ecosystems, Cooperative-based development, Institutional economics, and Koperasi Merah Putih

INTRODUCTION

Transforming food systems has become a central concern in both academic discourse and policy debates, reflecting their role in ensuring food security, sustaining rural livelihoods, and responding to climate and market shocks (FAO, 2021; HLPE, 2020). Food systems are increasingly understood not only as agricultural production activities but as integrated socio-economic and ecological systems that determine the availability, accessibility, affordability, and sustainability of food.

For Indonesia, a country of more than 280 million people, the urgency of food system transformation is particularly pronounced. Agriculture continues to play a critical role in the national economy, contributing 12.4% of gross domestic product and employing approximately 29% of the labor force (Badan Pusat Statistik [BPS], 2023). Yet the sector faces persistent structural constraints: declining land productivity, reliance on smallholder farming, fragmented supply chains, and vulnerability to global trade fluctuations. These challenges are exacerbated by climate change, urbanization, and demographic shifts.

Historically, Indonesia’s agricultural policy has prioritized productivity and self-sufficiency, with rice and other staple foods at the center of national strategies. While this approach secured short-term food availability, it has also generated long-term vulnerabilities, including environmental degradation, inefficiencies in smallholder production, and weak integration of farmers into higher-value markets (Hidayat, 2022). Recognizing these limitations, the government has reoriented its development trajectory. The Golden Indonesia Vision 2045 positions agriculture and food security as pillars of inclusive and sustainable growth, while the Indonesia National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) of 2025–2029 emphasizes food sovereignty, downstream agro-industrial development, green innovation, and entrepreneurship-led rural transformation (Bappenas, 2024).

In this context, three interdependent dimensions—policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship—are critical to driving systemic change. Policy provides the institutional framework that defines incentives and governance structures; innovation introduces new technologies, practices, and organizational models that improve efficiency and resilience; and entrepreneurship operationalizes these innovations, translating them into economic and social value. Together, these elements form the foundation for transforming Indonesia’s food system in alignment with national strategies and global sustainability agendas.

The purpose of this article is threefold. First, it develops an integrative theoretical framework that combines Schumpeterian innovation, endogenous growth, institutional economics, food systems thinking, and contemporary entrepreneurship theories. Second, it critically reviews Indonesia’s policy and regulatory frameworks related to food and agriculture. Third, it examines practical illustrations of innovation and entrepreneurship in Indonesia’s agriculture, drawing comparative insights from Japan’s cooperative systems and South Korea’s smart farm policies. By doing so, the article contributes to both academic debate and policy practice, offering a multidimensional analysis of how policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship interact to shape Indonesia’s food system transformation.

At the global level, Indonesia’s food system transformation also aligns with international commitments such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). The country’s emphasis on food sovereignty, sustainability, and rural entrepreneurship resonates with the priorities articulated during the UN Food Systems Summit (2021), which called for integrated approaches to ensure equitable access to healthy diets, strengthen climate resilience, and empower small-scale producers. Positioning Indonesia’s strategy within this global discourse highlights not only its domestic significance but also its contribution to advancing collective international goals for sustainable and inclusive food systems.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The transformation of national food systems requires a multidimensional theoretical foundation that recognizes innovation, entrepreneurship, and institutions as interconnected drivers of change. This study adopts an integrative framework that combines classical economic theories with contemporary entrepreneurship perspectives to analyze Indonesia’s agricultural transformation.

Innovation, creative destruction, and agricultural change

Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction explains how economic development occurs through cycles of innovation that disrupt existing structures while creating new opportunities (Schumpeter, 1934/2008). In agriculture, these innovations include mechanization, digital farming, biotechnology, and renewable energy from agricultural waste. Such changes not only enhance productivity but also reshape labor markets, trade flows, and value chains. In Indonesia, the adoption of mechanized rice farming has reduced demand for manual labor while increasing yields, producing both efficiency gains and social adjustment challenges. Policymakers must therefore complement technological innovation with social protection, labor reskilling, and inclusive business models (Dosi & Nelson, 2010).

Endogenous growth, human capital, and entrepreneurship

In Indonesian agriculture, entrepreneurship manifests in youth-led start-ups, digital agribusiness platforms, and agro-tourism enterprises that expand value chains and diversify rural incomes. Empirical studies further show that entrepreneurial orientation and personality traits strongly influence the performance of farmers and agribusiness ventures in Indonesia (Pambudy, 2016; Haliq, Pambudy, Burhanuddin, & Alfikri, 2018). Government instruments such as Kredit Usaha Rakyat (KUR, People’s Business Credit) exemplify policy mechanisms that stimulate entrepreneurial activity, thereby reinforcing growth trajectories (Audretsch & Thurik, 2001).

Institutional economics and policy coherence

Institutional economics underscores the role of formal rules, informal norms, and enforcement mechanisms in shaping economic behavior (North, 1990). In agriculture, coherent institutions are needed to address market failures such as credit constraints, environmental externalities, and information asymmetries. Indonesia’s governance landscape, however, is often marked by fragmented authority, with overlapping mandates across ministries and local governments. This can result in inconsistent land use policies, subsidy allocations, and trade regulations. Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) theory of collective action highlights the importance of local institutions in managing shared resources such as irrigation systems, while Rodrik (2004) stresses the role of coordinated industrial policy. These insights reinforce the need for institutional coherence to enable innovation and entrepreneurship to flourish in Indonesia’s food system.

Food systems approach: Beyond productivity

Recent scholarship calls for a food systems approach that extends beyond narrow productivity gains to address nutrition, equity, and sustainability (FAO, 2021; HLPE, 2020). This approach situates agriculture within broader socio-economic and ecological contexts, linking production, distribution, consumption, and environmental stewardship. For Indonesia, applying a food systems perspective means aligning national strategies such as the RPJMN 2025–2029 and Visi Indonesia Emas 2045 (Golden Indonesia Vision 2045) with climate-smart agriculture, circular economy practices, and rural–urban integration.

Contemporary entrepreneurship theories: Effectuation, ecosystems, and sustainability

Contemporary theories of entrepreneurship provide further insights into transformation in practice. Effectuation theory emphasizes how entrepreneurs act under uncertainty by leveraging available resources and partnerships rather than relying solely on predictive strategies (Sarasvathy, 2001). This resonates with smallholders in Indonesia who often adapt innovatively within resource-constrained environments.

The entrepreneurial ecosystems perspective highlights how entrepreneurial success depends not only on individual initiative but also on the quality of surrounding institutions, infrastructure, networks, and culture (Stam, 2015). In Indonesia, uneven access to finance, limited rural infrastructure, and fragmented extension services reveal the challenges of building a supportive ecosystem for agripreneurs.

Sustainable entrepreneurship theory integrates ecological and social goals into entrepreneurial practice, recognizing that new ventures can simultaneously create economic value and address sustainability challenges (Dean & McMullen, 2007). In Indonesia, initiatives such as livestock waste-to-energy projects, organic certification schemes, and agroforestry-based enterprises illustrate how sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship contributes to climate resilience and resource efficiency.

Integrative conceptual lens

Bringing these perspectives together, this study views food system transformation as a process shaped by five conceptual pillars:

Figure 1 illustrates how these pillars interact to drive Indonesia’s food system transformation. Each contributes directly to transformation outcomes, while the central focus highlights food system transformation as the overarching goal. The framework synthesizes insights from Schumpeter (1934/2008), Lucas (1988), Romer (1990), North (1990), Ostrom (1990), FAO (2021), HLPE (2020), Sarasvathy (2001), Stam (2015), and Dean & McMullen (2007).

By explicitly integrating these theoretical perspectives, the framework not only provides an analytical foundation for assessing Indonesia’s policy and entrepreneurial practices but also situates the country within broader regional and global debates on sustainable food system transformation.

POLICY REVIEW: INDONESIA’S AGENDAS AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS

Indonesia’s food system transformation agenda is increasingly defined by the country’s long-term vision documents and a suite of newly enacted regulatory frameworks that collectively establish the direction of reform. Law No. 59/2024 on the National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN 2025–2045) sets out the strategic framework for achieving the Visi Indonesia Emas 2045 (Golden Indonesia Vision 2045). Agriculture and food sovereignty are explicitly positioned as key pillars of inclusive growth, while sustainability, innovation, and entrepreneurship are embedded as cross-cutting priorities that must be operationalized across all development sectors. Building upon this macro-level foundation, Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN 2025–2029) translates these long-term aspirations into actionable five-year strategies. The RPJMN emphasizes food sovereignty, green innovation, bioeconomy development, and entrepreneurship-led rural transformation, thereby marking a decisive shift away from input-driven productivity policies toward systemic approaches to food system transformation.

Recent regulations illustrate the government’s attempt to balance innovation, governance, and sustainability imperatives in a rapidly changing global context. Government Regulation (PP) No. 19/2024 on the Supervision of Genetically Engineered Food revises oversight mechanisms for genetically modified products, reflecting Schumpeter’s (1934/2008) notion of creative destruction: biotechnology generates opportunities for productivity and resilience, but it also introduces governance and safety risks that require robust institutional safeguards (North, 1990). Complementing this, Presidential Decree No. 81/2024 on Food Diversification and Biofortification mandates the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) to spearhead research on biofortified crops and diversification of staple foods, underscoring the role of knowledge, research capacity, and human capital in advancing food security, consistent with the insights of endogenous growth theory (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1990).

Sustainability and circular economy principles have also been institutionalized through the Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan (2024), which is embedded within the RPJMN 2025–2029. This framework integrates resource efficiency, waste valorization, and climate-smart practices into agricultural and industrial development strategies. Within this policy context, the bioeconomy perspective is increasingly emphasized, where agriculture is viewed not only as a source of food but also as a provider of renewable biological resources such as biomass, organic fertilizers, and bio-based materials. Recent discussions highlight that Indonesia’s circular economy agenda is inseparable from the development of a bioeconomy that links agriculture, industry, and sustainability transitions (Goutama, 2025).

Its design reflects the food systems approach advocated by FAO (2021) and HLPE (2020), which emphasizes the interconnections between production, distribution, consumption, and environmental stewardship, while also resonating with sustainable entrepreneurship theory (Dean & McMullen, 2007). By embedding circular economy and bioeconomy principles into national planning, Indonesia addresses long-term ecological constraints, reduces systemic risks associated with resource depletion, and simultaneously creates new entrepreneurial opportunities in agri-food processing and waste-to-value ventures.

Despite these policy advances, significant challenges remain. Policy fragmentation persists, with overlapping mandates across ministries, agencies, and local governments, often resulting in inconsistent land-use policies, subsidy allocations, and trade regulations. The integration of sustainability objectives with entrepreneurship promotion is still in its formative stage, while rural disparities in infrastructure, access to finance, and digital literacy risk limiting the effective implementation of these regulatory frameworks. Nevertheless, the post-2024 policy landscape demonstrates a clear strategic commitment by the Indonesian government to move toward systemic food system transformation, one that balances governance, innovation, and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship within a coherent institutional framework.

The regulatory landscape for Indonesia’s food and agriculture sectors has thus undergone substantial reform since 2024, reflecting the government’s strategic shift toward food system transformation. As outlined in Law No. 59/2024 on the RPJPN 2025–2045 and Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the RPJMN 2025–2029, food sovereignty, innovation, sustainability, and entrepreneurship are identified as key pillars of national development. These overarching frameworks are complemented by a diverse set of sectoral regulations issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Cooperatives and SMEs, the Ministry of Trade, and the National Food Agency (NFA), each targeting specific aspects of production, distribution, safety, and market governance. Together, these instruments provide not only a legal foundation but also an enabling environment for innovation and entrepreneurship within Indonesia’s food system.

Table 1 summarizes the key post-2024 regulations, outlining their core content, their relevance to entrepreneurship and innovation, and their contribution to food system transformation (FST). The table also highlights the degree to which each regulatory instrument supports FST objectives. For example, NFA Regulation No. 2/2024 on Fresh Food Standards reinforces consumer trust through higher quality and safety requirements; the Ministry of Agriculture Regulation No. 3/2024 on Agricultural Area Development advances cluster-based entrepreneurship; and the Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan institutionalizes resource efficiency and climate-smart practices. By systematically mapping these regulations against the dimensions of entrepreneurship, innovation, and systemic transformation, the analysis underscores how Indonesia’s post-2024 regulatory reforms are converging toward a holistic and future-oriented food system agenda.

Table 1. Post-2024 policy and regulatory frameworks for food system transformation in Indonesia

Regulation / Framework

Content / Focus

Relevance to entrepreneurship

Relevance to innovation

Contribution to food system transformation

Law No. 59/2024 on the National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN 2025–2045)

Establishes Golden Indonesia Vision 2045; emphasizes food sovereignty, green economy, and innovation.

Promotes rural entrepreneurship, SMEs, and cooperatives as drivers of inclusive growth (RPJPN, Ch. IV – Economic Transformation).

Frames innovation in green technology and digitalization as strategic enablers (RPJPN, Ch. III – Science, Technology, and Innovation).

Provides the macro framework for shifting food systems beyond productivity toward sustainability and inclusivity.

Regulation No. 19/2024 on the Supervision of Genetically Engineered Food (BPOM)

Updates oversight of GMO food for governance and safety.

Opens potential for enterprises in seeds and biotech food products.

Sets biosafety requirements and innovation standards (Reg. 19/2024, Ch. II – Requirements for GE Food).

Ensures the safe integration of biotech into the food system under national regulatory frameworks.

Presidential Decree No. 81/2024 on Food Diversification and Biofortification

Assigns BRIN to lead research on biofortified crops and the diversification of staple foods.

Encourages agri-preneurship in local food diversification.

Advances R&D in biofortified crops and nutrition-sensitive agriculture.

Enhances diversification and nutrition within food systems.

Circular Economy Roadmap and Action Plan (integrated into RPJMN 2025–2029)

Institutionalizes resource efficiency, waste valorization, and climate-smart practices.

Generates opportunities in bioenergy, organic fertilizer, and green agribusiness (Roadmap, Priority 3 – Agriculture & Food Systems).

Promotes innovation in renewable energy and eco-efficient farming.

Embeds circular practices and climate-smart sustainability into food systems.

Presidential Regulation No. 12/2025 on the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN 2025–2029)

Operationalizes medium-term strategies: food sovereignty, rural entrepreneurship, innovation, and green transformation.

Expands entrepreneurship ecosystems through finance, incubation, and rural enterprises (RPJMN 2025–2029, Ch. V – Economic Development).

Integrates digitalization, smart farming, and green innovation (RPJMN 2025–2029, Ch. III – Innovation & Sustainability).

Blueprint for implementing food system transformation across sectors.

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 3/2024 on Agricultural Area Development

Defines criteria and management of agricultural zones, integration of commodities, farmer groups, and marketing.

Strengthens agripreneurship through cluster-based farming and collective marketing.

Facilitates adoption of modern technology and integrated value chains.

Supports efficiency and inclusivity by organizing agriculture spatially as part of FST.

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 13/2024 on Fresh Fruit Bunch (FFB) Trade for Palm Oil

Regulates fair trade between smallholders (plasma/independent) and palm oil mills.

Enhances bargaining power and market access for smallholders.

Introduces transparent pricing and digital record-keeping.

Builds more equitable and accountable supply chains within FST.

Minister of Agriculture Regulation No. 1/2024 and Ministerial Decree No. 249/2024 on Fertilizer Subsidies & e-RDKK

Expands subsidized fertilizer allocation; enforces digital farmer registration (e-RDKK).

Strengthens farmer organizations and cooperative entrepreneurship.

Promotes innovation in digital targeting of input distribution.

Increases smallholder productivity and transparency in input use.

Minister of Cooperatives & SMEs Regulation No. 2/2024 on Cooperative Accounting Standards

Standardizes cooperative financial reporting, audit, and transparency.

Strengthens cooperative-based entrepreneurship through better governance.

Encourages innovation in cooperative financial management systems.

Enhances cooperatives’ role as inclusive actors in food system distribution and processing.

Minister of Trade Regulation No. 8/2024 (Amendment to Import Regulation)

Revises rules on import of goods to support supply chain flexibility.

Expands opportunities for businesses to access imported inputs.

Enables diffusion of foreign technologies and agricultural machinery.

Stabilizes food and input availability, supporting resilience in FST.

Minister of Trade Regulation No. 18/2024 on Palm Cooking Oil (MinyakKita)

Regulates palm cooking oil packaging, branding, and supply chain under “MinyakKita.”

Expands entrepreneurship opportunities in local packaging and distribution.

Supports innovation in branding, marketing, and traceability.

Ensures the affordability and availability of a staple product in food systems.

National Food Agency (NFA) Regulation No. 2/2024 on Fresh Food Standards

Governs the safety, quality, nutrition, labeling, and advertising of fresh food.

Encourages agribusinesses and SMEs to meet higher market standards.

Stimulates product innovation in fresh and functional foods.

Reinforces food safety and consumer trust, a cornerstone of FST.

INNOVATION AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN INDONESIA’S AGRICULTURE

Innovation and entrepreneurship in Indonesia’s agricultural sector manifest in diverse and evolving forms, spanning digital start-ups, cooperative-led ventures, financial innovations, and integrated agribusiness models. Digital aquaculture platforms such as eFishery exemplify how IoT-based solutions can reduce production costs, optimize feed efficiency, and simultaneously connect farmers with financing institutions and buyers. Similarly, fresh produce e-commerce initiatives such as Sayurbox demonstrate how shortening supply chains can increase farmers' margins, reduce transaction costs, and enhance consumer access to affordable, traceable, and high-quality products. Agri-fintech mechanisms like Crowde further expand financial inclusion by mobilizing capital for smallholders who are often excluded from formal credit systems, thereby addressing one of the most persistent barriers to small-scale agricultural investment. Downstream branding initiatives in coffee, represented by Kopi Kenangan, illustrate the importance of value-added processing and innovative marketing strategies in repositioning local commodities within highly competitive domestic and global markets.

Beyond individual cases, broader systemic approaches to agrifood entrepreneurship are also emerging. Fisheries export platforms such as Aruna directly connect small-scale fishers with global buyers, bypassing traditional intermediaries and integrating producers more effectively into international value chains. Circular economy ventures such as Rekosistem illustrate how agricultural and food waste can be valorized into renewable energy, organic fertilizers, and other marketable by-products, embedding sustainability principles directly into the production cycle. Integrated agribusinesses such as Greenfields in the dairy sector demonstrate that Indonesian firms can compete with multinational corporations while simultaneously strengthening domestic supply chains, generating value addition, and enhancing rural employment. These systemic models show how innovation is not limited to technological solutions but also involves institutional, organizational, and market-based arrangements that reshape the structure of agrifood systems.

Importantly, cooperative-led models highlight the role of institutional innovation in distributing entrepreneurial benefits more equitably. Koperasi Merah Putih (Red-White Cooperative) represents a significant example of how collective action, transparent governance, and coordinated production can stabilize incomes, strengthen farmer bargaining power, and integrate smallholders into more formalized and structured markets. By contrast with start-ups or corporate agribusinesses that often concentrate risks and benefits in narrow segments of the chain, cooperative-based entrepreneurship spreads both risks and returns across members, making participation more inclusive and resilient. The cooperative model, therefore, complements technology-driven innovations by ensuring that systemic transformation is embedded in social solidarity and collective organization, which are particularly relevant in Indonesia’s rural economy.

Taken together, these illustrative cases confirm that agricultural entrepreneurship in Indonesia extends far beyond the establishment of individual firms. It encompasses a broad spectrum of mechanisms, including financial instruments, organizational models, cooperative institutions, and sustainability-oriented practices. Empirical research on smallholder farmers in West Java reinforces this point, showing how entrepreneurial orientation and individual traits directly shape business performance in livestock and poultry farming (Pambudy, 2016; Haliq et al., 2018).

These developments collectively reinforce Schumpeter’s (1934/2008) notion of creative destruction, whereby new organizational and technological forms displace outdated and inefficient structures. They also align with contemporary theories of entrepreneurship: effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001), which explains adaptive decision-making under uncertainty; entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam, 2015), which highlight the importance of institutional, infrastructural, and cultural environments; sustainable entrepreneurship (Dean & McMullen, 2007), which integrates ecological and social concerns into business practice; and institutional entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006), which emphasizes the transformation of rules and norms through entrepreneurial agency.

More broadly, the Indonesian experience demonstrates that agricultural innovation is heterogeneous, dynamic, and deeply embedded within social and institutional contexts. It contributes not only to improvements in productivity and competitiveness but also to the broader agenda of building inclusive, resilient, and sustainability-oriented food systems. By linking digital technology, financial innovation, cooperative organization, and circular economy principles, Indonesia provides an instructive case for other emerging economies seeking to balance modernization with equity and long-term sustainability in their agricultural transformations.

Red-White Cooperatives: Integrating policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship for food system transformation

Indonesia’s agricultural transformation illustrates that policy, innovation, and entrepreneurship are mutually reinforcing rather than isolated drivers of systemic change. Policy establishes the institutional environment by defining rules, incentives, and priorities; innovation provides the technological, organizational, and managerial mechanisms required for productivity, resilience, and sustainability; and entrepreneurship operationalizes these innovations, translating them into market-oriented practices that deliver tangible economic and social benefits. This tripartite interplay reflects Indonesia’s broader vision for food system transformation, in which policy sets the stage, innovation supplies the tools, and entrepreneurship generates outcomes at the grassroots level.

The RPJPN 2025–2045 and RPJMN 2025–2029 outline overarching goals—food sovereignty, economic inclusivity, and environmental sustainability—that guide sectoral strategies and policy instruments. Within this framework, the Koperasi Merah Putih (Red-White Cooperative) serves as a prominent example of how entrepreneurial initiatives can align with national development priorities. The cooperative is an official program of President Prabowo Subianto’s administration, based on Presidential Instruction No. 9/2025, and was formally inaugurated in July 2025. By consolidating farmer production, enforcing transparent financial governance, and formalizing partnerships with downstream buyers, the Red-White Cooperative has raised farmers' incomes, stabilized local food supplies, and generated new rural economic opportunities. Its trajectory illustrates the principle of institutional entrepreneurship (Mair & Marti, 2006), demonstrating that innovation arises not only from the deployment of advanced technologies but also from collective organization, transparent management, and supportive governance structures.

The legal foundation of the Red-White Cooperative is firmly anchored in Indonesia’s broader regulatory framework. The Cooperative Law (Law No. 25/1992) defines cooperatives as business entities based on mutual cooperation and democratic economic principles, granting them legitimacy to organize production, distribution, and finance collectively. In the agricultural domain, the Food Law (Law No. 18/2012) affirms food sovereignty, security, and safety as state priorities and underscores the role of farmer institutions in achieving them. The Village Law (Law No. 6/2014) further strengthens rural-based institutions by enabling cooperatives to access state funds and integrate their activities into local development initiatives. Complementing these statutory foundations, the National Medium-Term Development Plan (Presidential Regulation No. 18/2020 and its successor, RPJMN 2025–2029) explicitly promotes cooperative-based agribusiness and digital agriculture as instruments of inclusive growth. Taken together, these legal instruments embody the constitutional mandate of Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution, which requires that the national economy be organized as a common endeavor founded on the principle of kinship.

Against this backdrop, the Red-White Cooperative exemplifies how inclusive entrepreneurship can embody regulatory priorities while addressing systemic challenges in the food system. Unlike start-ups or corporate agribusinesses, which often concentrate both risks and benefits in narrow segments of the value chain, the cooperative redistributes risks and benefits more equitably among its members. This institutional design strengthens bargaining power, ensures smallholder participation in value chains, and enhances the resilience of rural economies. By linking policy support with grassroots innovation, the cooperative builds a bridge between national visions and local realities, translating long-term development strategies into concrete improvements in livelihoods.

The Red-White Cooperative thus represents a uniquely Indonesian pathway to food system transformation, one that merges entrepreneurial dynamism with collective solidarity to advance productivity, resilience, and inclusivity simultaneously. Indonesia’s experience demonstrates that coherent policy frameworks, applied innovation, and inclusive entrepreneurship—when embedded in cooperative institutions—can jointly drive systemic transformation in the food sector. The case of the Red-White Cooperative underscores the transformative potential of legally grounded cooperative models within Indonesia’s institutional frameworks as a national strategy that combines technological dynamism, collective action, and social justice. In this sense, the cooperative serves not only as an instrument of agricultural modernization but also as a vehicle for fulfilling constitutional and developmental mandates of equity, sustainability, and national resilience.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS