ABSTRACT

Vietnam is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war and the country’s reunification. Way back, on April 30, 1975, the government embarked upon a new challenging journey toward reconstruction and socio-economic development. As the backbone of Vietnam’s economy, its agricultural sector had to feed a population that doubled over five decades, reaching 100 million in 2023. An accomplishment that can provide inspiration and lessons learnt for other nations that face similar challenges. This article aims to review some experiences related to agricultural reform and development in Vietnam during the period 1975-2025.

Keywords: Agricultural policy, development, Vietnam

INTRODUCTION

Global and historical context

The transition of Vietnam from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy was much less smooth than hoped. The country lacked almost everything after the war and experienced severe food shortages. Vietnam’s predominantly agricultural economy had been devastated by 30 consecutive years of armed conflict. The country’s recovery was further complicated by global geopolitics, including the 1975-1994 US-imposed embargo, the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, and the associated dissolution of the Socialist Bloc, which had been Vietnam’s lifeline for decades.

To advance its post-war development, Vietnam adopted a centrally planned economy. Despite the great effort, agricultural development stagnated and domestic food output proved insufficient to meet national demand. To feed the nation, the country initially had to import 1-2 million tons of food per year. Farmers’ earnings were meager, and most of Vietnam’s rural population lived in poverty. To grow sufficient food, farmers further encroached upon Vietnam’s forestland, which was already scarred. As a result, national forest cover had shrunk to 27% in 1990.

The key points of 50 years of Vietnam's agricultural development

Doi Moi – a market-oriented reform

In 1986, the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam initiated a comprehensive economic reform, called "Doi Moi", which began with the agricultural sector. Under "Doi Moi", Vietnam’s agriculture was transformed from a centrally planned, state-controlled system to a more liberal, market-oriented industry.

This was achieved through eight mutually enforcing levers:

1) Land reform, in which farmland was redistributed to millions of farmers, land taxes were waived for smallholders, and land tenure security certificates were granted;

2) Market liberalization and international integration, in which free inter-country movement of agri-food produce was encouraged, and the nation became progressively integrated into the world market. Vietnam became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2007. In the meantime, seventeen Free Trade Agreements were signed with other countries;

3) Far-reaching reform of state enterprises and cooperatives, aimed at promoting private sector engagement and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI);

4) Farmer-oriented public extension backed by robust food crop breeding, phytosanitary or veterinary services and strengthened agricultural research apparatus;

5) An extensive credit system enabling investments by agri-businesses and individual farmers alike;

6) An upgraded rural infrastructure, involving near-total coverage of (rice) irrigation, electrification and paved roadways, and targeted stimuli for supply chains and processing industries;

7) Enhanced market connections, with agri-food producers steadily moving from self-sufficiency to market-oriented production of high-value crops; and

8) A bundle of enabling policies and targeted investments through government budgets, international development banks, bilateral donors and FDI.

The Vietnam land law in 1993 allows the land use right for farmers with duration of 20 years. So farmer can have long-term land security to invest in the agricultural activities. In the subsequent decades, nutrient-dense food became readily available and affordable for all. Farmer incomes also rose steadily, poverty declined by 1-2% per annum and life expectancy rose by 10 years over 1990-2023. By generating employment opportunities on- and off-farm, Vietnam lifted 30 million people out of poverty. This is the result of National poverty reduction program that government has realized over the period. Added attention was given to forest protection and afforestation. By 2023, forest coverage had rebounded to 42%. As such, Vietnam’s agriculture sector became an engine for the country’s economic development, social stability and incipient environmental protection.

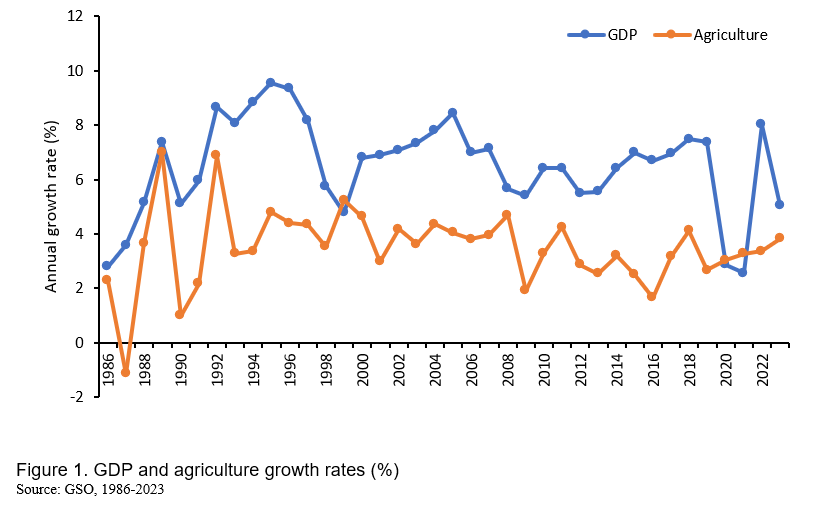

The “Doi Moi” reform created huge incentives for farmers and agri-businesses to raise food outputs continually. As a result, Vietnam’s agricultural sector grew at an average of 3.5% per year between 1986-2023 (Figure 1). Between 1990 and 2023, farm-level outputs of coffee, rubber or cashew grew substantially, whereas poultry, pig or fishery production increased two to ten-fold.

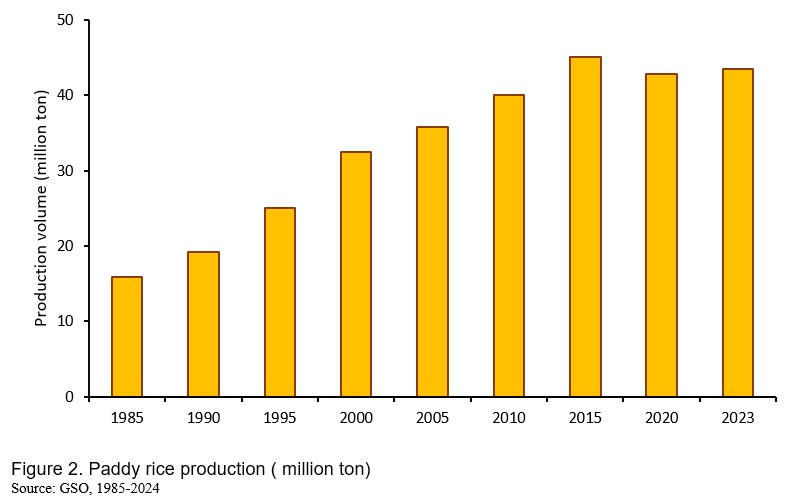

Vietnam turned from a net food importer to the world’s third-largest rice exporter. In 2023, on just less than 4 million ha of land, Vietnam produced yearly more rice than all of Africa (Figure 2). In 2024, the country exported US$62.5 billion in agricultural, forestry, or fisheries products. Vietnam further aims to become one of the world’s top 10 agri-food processing hubs in 2030.

Role of science and technology

Though policy reform created strong incentives for the transformation of Vietnam’s agriculture sector, science and technology provided the necessary know-how. Presently, more than 90% of Vietnam’s farm premises are planted with improved varieties of rice, maize, cassava, sugarcane, coffee or rubber, many of which are drought-tolerant or resistant to debilitating pests and pathogens. Similarly, new breeds of pigs, chickens, shrimps, and catfish are widely adopted. Technical aspects of crop and livestock production also continuously improved. More than 90% of Vietnam’s rice crop is now mechanically harvested, high-tech greenhouses are increasingly set up for horticultural production, and livestock is increasingly produced in (automated) modern farms.

These improvements were mirrored in superior yield and quality of harvested produce. Vietnam’s yields of rice, coffee, and rubber are now respectively 29%, 316% and 61% higher than the global average, whereas some of its rice varieties have twice been recognized as the world’s best. Specifically for rice productivity, in 2022, Vietnam rice productivity reach 6.06 ton/ha, while the global average rice productivity is only 4.7 ton/ha. Fast-paced improvements in post-harvest processing over the past decades have further reduced agricultural losses while adding product value.

Over the past five decades, Vietnam has benefited from technical and/or financial support, both bilaterally and through international organizations such as the FAO of the United Nations and institutions within the CGIAR (the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research). This has allowed the country to establish the necessary policy and techno-scientific capabilities to transform its agriculture sector. For example, in the period 1980-2008, three-quarters of Vietnam’s rice varieties could be directly traced to the pedigree of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) under the CGIAR. Vietnam’s aquaculture sector advanced with large strides, partly thanks to know-how brought by different international partners. Regionally coordinated releases of beneficial insects tackled debilitating invasive pest problems in cassava or coconut, yielding social-environmental benefits across Vietnam’s countryside. Meanwhile, institutions such as the World Bank, ADB and IFAD have financed these developments, thereby encouraging FDI and generating rural employment.

Main challenges

Despite its notable achievements, Vietnam's agriculture is facing four prominent challenges:

1. Not all sub-sectors have benefited equally from the techno-scientific advances post-1986. As local maize, beans or cotton cropping and cattle raising are typified by low production efficiency, Vietnam’s agriculture in those subsectors is notably lagging behind;

2. Vietnam’s farmers income remains low. With monthly per-capita incomes as low as US$170 (2023), the rural-urban income gap progressively widens. In 2024, The average income of workers in urban areas was US$360 per month and in rural areas it was US$260 per month. As a result, many farmers shift to non-farm activities while youngsters tend to leave the countryside;

3. Vietnam’s agriculture has become overly reliant upon costly petroleum-derived inputs including chemical pesticides and fertilizers, fuel and antibiotics. Vietnam’s vegetable growers, for instance, overspend US$300-400/ha per cropping season on pesticides. Those input dependencies depress incomes, generate greenhouse gas emissions, jeopardize food safety and healthy diets, and harm biodiversity; and

4. Unsustainable intensification practices further undermine the long-term sustainability of Vietnam’s agriculture. Extractive production methods aimed at short-term yield maximization can lead to a progressive degradation of farmland ecosystems, triggering erosion and soil fertility decline.

Toward agroecology

To cope with the above challenges while pursuing the sustainable development goals, Vietnam opted to put its agriculture on a ‘green growth’ track and chose decisively for agroecology as general approach for food system transformation. In 2022, Vietnam’s Government launched a strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development for 2025-2030 with a vision toward 2050. Through this strategy, the country aims to use agroecology as a means to revitalize its agriculture sector, modernize its countryside and benefit societal wellbeing at large. A bold, comprehensive action plan on food system transformation to 2030 aiming to connect better sustainable production and consumption has been devised to put this transformation in action. This involves eight key aspects:

1. Restructure agriculture based on comparative advantages and market demands;

2. Ensure efficiency and sustainability by adjusting critical components of agri-food value chains, closing nutrient loops and alleviating input dependency;

3. Promote cooperation of actors along the value chains within food systems;

4. Develop rural off-farm activities;

5. Modernize the countryside in conjunction with urbanization, protecting folk culture, food heritage and traditional landscapes;

6. Pursue inclusive, equitable development;

7. Promote community development e.g., by shifting the emphasis from yield gain to long-term revenue and societal wellbeing, including nutrition security; and

8. Intensify agricultural and food production in a responsible manner, protecting the environment and strengthening resilience against recurrent floods or droughts.

Sound intensification of Vietnam’s agriculture is within reach. FAO-coordinated training programs during the 1980s-90s already reduced pesticide use by up to 92% in locally grown cabbage, tea or rice crops, simultaneously enhancing farm profits, food safety and biodiversity. Given the major advances in biotechnology, genetics, digital tools and artificial intelligence (AI) since the late 1900s, one can surely place the bar even higher. To achieve those goals, market-oriented policy reform will continue while science, technology, and innovation can be harnessed to turn Vietnam into a 21st-century agricultural powerhouse. This approach, while actively preserving the interconnected health of people, animals, and the environment, is a concept known as One Health.

In a world grappling with food insecurity and environmental degradation, enhancing total factor productivity (TFP) - the efficiency with which inputs like labor, land, water, and fertilizers are converted into agricultural produce - offers a path forward. Agroecology, a science and practice rooted in ecological principles, is emerging as a transformative approach to sustain (or even raise) crop yields in the face of climatic upheaval while conserving biodiversity, soil health and environmental integrity. By integrating scientific and farmer knowledge, bridging social and natural sciences, and infusing place-based solutions with AI, genetics or digital tools, agroecology could redefine sustainable farming for the 21st century.

CONCLUSION

Over the past four decades, Vietnam has successfully transformed its agriculture. Market-oriented reform, paired with sound policies and strong techno-scientific development, was a core determinant of this success. From 1986 onward, Vietnam’s agriculture has been the motor engine of its impressive economic growth and social stability, generating stable food supplies, securing foreign valuta, and lifting millions out of poverty. Yet, business as usual is no longer adequate or desirable. Whereas unsustainable farming methods lifted short-term yields, they can negatively affect farm profits, food safety, environmental integrity, and resilience. Vietnam’s Government decision to put agriculture on a ‘greener’ growth trajectory can remediate these issues. There are different policies that have been integrated under national action plan of food system transformation by 2030. The priorities are (1) Do specific planning for sustainable agriculture and rural development; (2) Digital transformation to facilitate agroecology and circular economy in agriculture, (3) Adaptation towards climate changes, drought, and landslide, (4) Higher farmer’s livelihood, modernizing agriculture with technological development; (5) Promoting agricultural export and aquaculture farming and fisheries. It will ensure that intensification does not come at the expense of people, the climate, or the planet. Intensifying Vietnam’s agriculture according to new principles offers a powerful lever, while science, innovation and technological development can play a decisive role. This initiative needs to be funded by the shoulders of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the Development Partners, along with South-South/Triangular Cooperation (SSTC). Under experienced management and leadership taking bold initiatives, a bright future for agriculture in Vietnam undoubtedly lies ahead.

REFERENCES

General Statistical Office, 2006. General census of agriculture and rural development 2005.

General Statistical Office, 2021. General census of agriculture and rural development 2020.

Government decision No 07/2021/ND-CP, enacted 27 January 202, On multidimensional poverty standards for the period 2022-2025.

Nguyen Sinh Cuc, Nguyen An Tiem. Half of a century of agriculture and rural development in Vietnam (1945-1995). Publishing house Agriculture, 1996.

Premier Minister Decision 150/QD- TTg, 28 January 2022. Approval of strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development in the period 2021- 2030, vision toward 2050.

Priority and removing difficulties in providing credit to agricultural and rural sectors. Banking Review. March 2023.

Resolution No 19 NQ/TW, 16 June 2022, of the XIIIth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside by 2030, with the perspective to 2045

Resolution No 26 NQ/TW, 5 August 2008, of the Xth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside

The World Bank, 2016. Transforming Vietnamese agriculture: Gaining more for less., 2016.

The World Bank, 2022. Vietnam climate and development report.

Uma Lele, 2021. Food for All., p 642, 649

Van den Berg, H. and Jiggins, J., 2007. Investing in farmers—the impacts of farmer field schools in relation to integrated pest management. World development, 35(4), 663-686.

Vietnam’s food security in times of environmental uncertainty, population growth & technological advances looking back to plan ahead, Hanoi, 25 October 2017.

Vietnam's Agricultural Development Review: A 50-Year Journey (1975-2025)

ABSTRACT

Vietnam is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the end of the war and the country’s reunification. Way back, on April 30, 1975, the government embarked upon a new challenging journey toward reconstruction and socio-economic development. As the backbone of Vietnam’s economy, its agricultural sector had to feed a population that doubled over five decades, reaching 100 million in 2023. An accomplishment that can provide inspiration and lessons learnt for other nations that face similar challenges. This article aims to review some experiences related to agricultural reform and development in Vietnam during the period 1975-2025.

Keywords: Agricultural policy, development, Vietnam

INTRODUCTION

Global and historical context

The transition of Vietnam from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy was much less smooth than hoped. The country lacked almost everything after the war and experienced severe food shortages. Vietnam’s predominantly agricultural economy had been devastated by 30 consecutive years of armed conflict. The country’s recovery was further complicated by global geopolitics, including the 1975-1994 US-imposed embargo, the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, and the associated dissolution of the Socialist Bloc, which had been Vietnam’s lifeline for decades.

To advance its post-war development, Vietnam adopted a centrally planned economy. Despite the great effort, agricultural development stagnated and domestic food output proved insufficient to meet national demand. To feed the nation, the country initially had to import 1-2 million tons of food per year. Farmers’ earnings were meager, and most of Vietnam’s rural population lived in poverty. To grow sufficient food, farmers further encroached upon Vietnam’s forestland, which was already scarred. As a result, national forest cover had shrunk to 27% in 1990.

The key points of 50 years of Vietnam's agricultural development

Doi Moi – a market-oriented reform

In 1986, the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam initiated a comprehensive economic reform, called "Doi Moi", which began with the agricultural sector. Under "Doi Moi", Vietnam’s agriculture was transformed from a centrally planned, state-controlled system to a more liberal, market-oriented industry.

This was achieved through eight mutually enforcing levers:

1) Land reform, in which farmland was redistributed to millions of farmers, land taxes were waived for smallholders, and land tenure security certificates were granted;

2) Market liberalization and international integration, in which free inter-country movement of agri-food produce was encouraged, and the nation became progressively integrated into the world market. Vietnam became a member of the World Trade Organization in 2007. In the meantime, seventeen Free Trade Agreements were signed with other countries;

3) Far-reaching reform of state enterprises and cooperatives, aimed at promoting private sector engagement and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI);

4) Farmer-oriented public extension backed by robust food crop breeding, phytosanitary or veterinary services and strengthened agricultural research apparatus;

5) An extensive credit system enabling investments by agri-businesses and individual farmers alike;

6) An upgraded rural infrastructure, involving near-total coverage of (rice) irrigation, electrification and paved roadways, and targeted stimuli for supply chains and processing industries;

7) Enhanced market connections, with agri-food producers steadily moving from self-sufficiency to market-oriented production of high-value crops; and

8) A bundle of enabling policies and targeted investments through government budgets, international development banks, bilateral donors and FDI.

The Vietnam land law in 1993 allows the land use right for farmers with duration of 20 years. So farmer can have long-term land security to invest in the agricultural activities. In the subsequent decades, nutrient-dense food became readily available and affordable for all. Farmer incomes also rose steadily, poverty declined by 1-2% per annum and life expectancy rose by 10 years over 1990-2023. By generating employment opportunities on- and off-farm, Vietnam lifted 30 million people out of poverty. This is the result of National poverty reduction program that government has realized over the period. Added attention was given to forest protection and afforestation. By 2023, forest coverage had rebounded to 42%. As such, Vietnam’s agriculture sector became an engine for the country’s economic development, social stability and incipient environmental protection.

The “Doi Moi” reform created huge incentives for farmers and agri-businesses to raise food outputs continually. As a result, Vietnam’s agricultural sector grew at an average of 3.5% per year between 1986-2023 (Figure 1). Between 1990 and 2023, farm-level outputs of coffee, rubber or cashew grew substantially, whereas poultry, pig or fishery production increased two to ten-fold.

Vietnam turned from a net food importer to the world’s third-largest rice exporter. In 2023, on just less than 4 million ha of land, Vietnam produced yearly more rice than all of Africa (Figure 2). In 2024, the country exported US$62.5 billion in agricultural, forestry, or fisheries products. Vietnam further aims to become one of the world’s top 10 agri-food processing hubs in 2030.

Role of science and technology

Though policy reform created strong incentives for the transformation of Vietnam’s agriculture sector, science and technology provided the necessary know-how. Presently, more than 90% of Vietnam’s farm premises are planted with improved varieties of rice, maize, cassava, sugarcane, coffee or rubber, many of which are drought-tolerant or resistant to debilitating pests and pathogens. Similarly, new breeds of pigs, chickens, shrimps, and catfish are widely adopted. Technical aspects of crop and livestock production also continuously improved. More than 90% of Vietnam’s rice crop is now mechanically harvested, high-tech greenhouses are increasingly set up for horticultural production, and livestock is increasingly produced in (automated) modern farms.

These improvements were mirrored in superior yield and quality of harvested produce. Vietnam’s yields of rice, coffee, and rubber are now respectively 29%, 316% and 61% higher than the global average, whereas some of its rice varieties have twice been recognized as the world’s best. Specifically for rice productivity, in 2022, Vietnam rice productivity reach 6.06 ton/ha, while the global average rice productivity is only 4.7 ton/ha. Fast-paced improvements in post-harvest processing over the past decades have further reduced agricultural losses while adding product value.

Over the past five decades, Vietnam has benefited from technical and/or financial support, both bilaterally and through international organizations such as the FAO of the United Nations and institutions within the CGIAR (the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research). This has allowed the country to establish the necessary policy and techno-scientific capabilities to transform its agriculture sector. For example, in the period 1980-2008, three-quarters of Vietnam’s rice varieties could be directly traced to the pedigree of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) under the CGIAR. Vietnam’s aquaculture sector advanced with large strides, partly thanks to know-how brought by different international partners. Regionally coordinated releases of beneficial insects tackled debilitating invasive pest problems in cassava or coconut, yielding social-environmental benefits across Vietnam’s countryside. Meanwhile, institutions such as the World Bank, ADB and IFAD have financed these developments, thereby encouraging FDI and generating rural employment.

Main challenges

Despite its notable achievements, Vietnam's agriculture is facing four prominent challenges:

1. Not all sub-sectors have benefited equally from the techno-scientific advances post-1986. As local maize, beans or cotton cropping and cattle raising are typified by low production efficiency, Vietnam’s agriculture in those subsectors is notably lagging behind;

2. Vietnam’s farmers income remains low. With monthly per-capita incomes as low as US$170 (2023), the rural-urban income gap progressively widens. In 2024, The average income of workers in urban areas was US$360 per month and in rural areas it was US$260 per month. As a result, many farmers shift to non-farm activities while youngsters tend to leave the countryside;

3. Vietnam’s agriculture has become overly reliant upon costly petroleum-derived inputs including chemical pesticides and fertilizers, fuel and antibiotics. Vietnam’s vegetable growers, for instance, overspend US$300-400/ha per cropping season on pesticides. Those input dependencies depress incomes, generate greenhouse gas emissions, jeopardize food safety and healthy diets, and harm biodiversity; and

4. Unsustainable intensification practices further undermine the long-term sustainability of Vietnam’s agriculture. Extractive production methods aimed at short-term yield maximization can lead to a progressive degradation of farmland ecosystems, triggering erosion and soil fertility decline.

Toward agroecology

To cope with the above challenges while pursuing the sustainable development goals, Vietnam opted to put its agriculture on a ‘green growth’ track and chose decisively for agroecology as general approach for food system transformation. In 2022, Vietnam’s Government launched a strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development for 2025-2030 with a vision toward 2050. Through this strategy, the country aims to use agroecology as a means to revitalize its agriculture sector, modernize its countryside and benefit societal wellbeing at large. A bold, comprehensive action plan on food system transformation to 2030 aiming to connect better sustainable production and consumption has been devised to put this transformation in action. This involves eight key aspects:

1. Restructure agriculture based on comparative advantages and market demands;

2. Ensure efficiency and sustainability by adjusting critical components of agri-food value chains, closing nutrient loops and alleviating input dependency;

3. Promote cooperation of actors along the value chains within food systems;

4. Develop rural off-farm activities;

5. Modernize the countryside in conjunction with urbanization, protecting folk culture, food heritage and traditional landscapes;

6. Pursue inclusive, equitable development;

7. Promote community development e.g., by shifting the emphasis from yield gain to long-term revenue and societal wellbeing, including nutrition security; and

8. Intensify agricultural and food production in a responsible manner, protecting the environment and strengthening resilience against recurrent floods or droughts.

Sound intensification of Vietnam’s agriculture is within reach. FAO-coordinated training programs during the 1980s-90s already reduced pesticide use by up to 92% in locally grown cabbage, tea or rice crops, simultaneously enhancing farm profits, food safety and biodiversity. Given the major advances in biotechnology, genetics, digital tools and artificial intelligence (AI) since the late 1900s, one can surely place the bar even higher. To achieve those goals, market-oriented policy reform will continue while science, technology, and innovation can be harnessed to turn Vietnam into a 21st-century agricultural powerhouse. This approach, while actively preserving the interconnected health of people, animals, and the environment, is a concept known as One Health.

In a world grappling with food insecurity and environmental degradation, enhancing total factor productivity (TFP) - the efficiency with which inputs like labor, land, water, and fertilizers are converted into agricultural produce - offers a path forward. Agroecology, a science and practice rooted in ecological principles, is emerging as a transformative approach to sustain (or even raise) crop yields in the face of climatic upheaval while conserving biodiversity, soil health and environmental integrity. By integrating scientific and farmer knowledge, bridging social and natural sciences, and infusing place-based solutions with AI, genetics or digital tools, agroecology could redefine sustainable farming for the 21st century.

CONCLUSION

Over the past four decades, Vietnam has successfully transformed its agriculture. Market-oriented reform, paired with sound policies and strong techno-scientific development, was a core determinant of this success. From 1986 onward, Vietnam’s agriculture has been the motor engine of its impressive economic growth and social stability, generating stable food supplies, securing foreign valuta, and lifting millions out of poverty. Yet, business as usual is no longer adequate or desirable. Whereas unsustainable farming methods lifted short-term yields, they can negatively affect farm profits, food safety, environmental integrity, and resilience. Vietnam’s Government decision to put agriculture on a ‘greener’ growth trajectory can remediate these issues. There are different policies that have been integrated under national action plan of food system transformation by 2030. The priorities are (1) Do specific planning for sustainable agriculture and rural development; (2) Digital transformation to facilitate agroecology and circular economy in agriculture, (3) Adaptation towards climate changes, drought, and landslide, (4) Higher farmer’s livelihood, modernizing agriculture with technological development; (5) Promoting agricultural export and aquaculture farming and fisheries. It will ensure that intensification does not come at the expense of people, the climate, or the planet. Intensifying Vietnam’s agriculture according to new principles offers a powerful lever, while science, innovation and technological development can play a decisive role. This initiative needs to be funded by the shoulders of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the Development Partners, along with South-South/Triangular Cooperation (SSTC). Under experienced management and leadership taking bold initiatives, a bright future for agriculture in Vietnam undoubtedly lies ahead.

REFERENCES

General Statistical Office, 2006. General census of agriculture and rural development 2005.

General Statistical Office, 2021. General census of agriculture and rural development 2020.

Government decision No 07/2021/ND-CP, enacted 27 January 202, On multidimensional poverty standards for the period 2022-2025.

Nguyen Sinh Cuc, Nguyen An Tiem. Half of a century of agriculture and rural development in Vietnam (1945-1995). Publishing house Agriculture, 1996.

Premier Minister Decision 150/QD- TTg, 28 January 2022. Approval of strategy of sustainable agriculture and rural development in the period 2021- 2030, vision toward 2050.

Priority and removing difficulties in providing credit to agricultural and rural sectors. Banking Review. March 2023.

Resolution No 19 NQ/TW, 16 June 2022, of the XIIIth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside by 2030, with the perspective to 2045

Resolution No 26 NQ/TW, 5 August 2008, of the Xth Central Committee about Agriculture, Farmers and Countryside

The World Bank, 2016. Transforming Vietnamese agriculture: Gaining more for less., 2016.

The World Bank, 2022. Vietnam climate and development report.

Uma Lele, 2021. Food for All., p 642, 649

Van den Berg, H. and Jiggins, J., 2007. Investing in farmers—the impacts of farmer field schools in relation to integrated pest management. World development, 35(4), 663-686.

Vietnam’s food security in times of environmental uncertainty, population growth & technological advances looking back to plan ahead, Hanoi, 25 October 2017.