ABSTRACT

In recent years, the food waste issue has received growing interest within the government, businesses, and the general public because it could cause food insecurity and environmental pollution. Various factors contribute to food waste during the stages of food production, processing, retailing, and consumption. Moreover, households and consumers both directly and indirectly cause a significant quantity of food waste. This study is a preliminary study to describe the household behaviors regarding the management of food waste and to analyze the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and attitudes toward food waste disposal at the household level. Using structured questionnaires, the data were collected from 90 purposive randomly selected households in the Nay Pyi Taw area. The findings indicated that most of the sample respondents who cook the main meals at home were women, and the households were using about two-thirds of the total expenditure for food costs. Among the surveyed households, two-thirds of the respondents made a shopping list, but they did not buy only the foods on the list. Moreover, they purchased an excess amount of food when they obtained the promotional offers. Almost half of the sample respondents were aware of their households’ food waste amounts, and the most wasted food was cooked meals. The most common reason for throwing away cooked meals was household members did not eat the prepared foods. The results indicated that the age of the respondents was positively associated with the respondents’ awareness level of food waste amount while the education level of the respondents was negatively correlated with their shopping times per week. The sample respondents said that food waste management awareness campaigns needed to be implemented for food waste reduction. In addition, it needs to adopt new policies to reduce food waste for the public towards food security and growing attention on green, clean and healthy environment in the circular economy. Further studies to cover food waste management at the household, municipal and community levels in different regions should be carried out in Myanmar.

Keywords: Food waste management, consumer behavior, socio-demographic characteristics, awareness

INTRODUCTION

Every year, almost one-third of all the food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost (Gustavsson et al., 2011). At the international level, the importance of the theme of food loss and waste has led to a significant increase in scientific production (Di Talia, Simeone, & Scarpato, 2019). Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 12.3 asks for halving global per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels by 2030, and eliminating food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses. The UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 emphasized the importance of food loss and waste reduction to create a sustainable food system and meet all 17 SDGs (UN Food Systems Summit, 2021).

Food waste means uneaten food that refers to unused or discarded food. Food waste occurs from various causes, including the loss of potentially valuable food products during the food production, processing, retailing, and consumption stages (Food Waste, 2021). The perishable home-used products, such as bakery and dairy products, fruits and vegetables, and meat and fish, are the most wasted (Morgan, 2009). Food losses have negative economic and environmental consequences, affecting valuable resources such as land, water, and energy, as well as incurred expenditures that are never recovered.

Both directly and indirectly, households and consumers are responsible for a large amount of food waste. Food loss at the consumption stage is a direct result of consumer purchasing habits (Di Talia, Simeone, & Scarpato, 2019). The main reason for food waste at the consumption stage is people do not store, prepare or cook the foods correctly. Furthermore, people are throwing edible food away because they thought it was spoilt; or because it had actually spoilt, but the consumer never got around to using it in time.

Numerous studies have sought to investigate how consumers think about and behave when it comes to food waste because households and consumers are the main producers of food waste (Visschers, Wickli, & Siegrist, 2016). Moreover, understanding the contextual factors influencing consumers' food waste management behavior could help develop strategies and policies for food waste reduction in the country. However, there is very few research on consumer food waste management behaviors in Myanmar. Therefore, this study aims to identify the respondents’ attitudes and behaviors regarding food waste management in randomly chosen households in the Nay Pyi Taw region, Myanmar.

Objectives of the study

- To investigate personal attitudes and behaviors in regard to managing food waste of selected households in the study area

- To analyze the relationship between demographic characteristics and attitudes towards food waste disposal management

METHODOLOGY

Study sites and sample selection for data collection

Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships are eight administrative townships in the Nay Pyi Taw region, as per data from the Department of Population (2015). These townships were chosen as the preliminary study locations. The study areas have a variety of household clusters, including government staff, private company staff, and farmers. In this study, the members of the household who spend more time in the kitchen and are more conscious of the financial waste associated with throwing food out were selected as the prospective sample respondents.

Data collection and data analysis

A field survey for primary data collecting was undertaken in November 2021 to gather the respondents' views and behaviors around food waste in Nay Pyi Taw. For the data collection, the enumerators went door-to-door to the households, explained the purpose of the study, and requested their voluntary participation in the survey. The face-to-face interview was conducted utilizing the structured questionnaire if the respondent agreed to participate in the study. Using the purposive random sampling method, 90 respondents for the study were selected.

The questionnaire's initial section asked about the socio-demographic details of the sample respondents, and it was followed by a series of inquiries into the attitudes and practices of the respondents regarding food waste. The collected information was converted to digital form, then compiled and delivered into a pre-defined format to evaluate outcomes. Results were obtained after the data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS statistical software. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample respondents in the study were calculated using descriptive statistics. Pearson's Correlation test was utilized to measure the statistical relationship between the respondents' socio-demographic traits and their attitudes toward food waste disposal.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic information of sample respondents

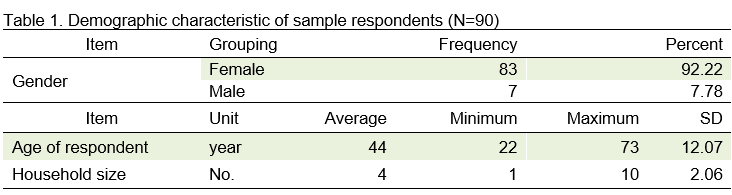

The demographic characteristics of 90 sample respondents from the study area are described in Table 1. Among the sample respondents, the majority of the respondents (92%) were female who mostly handle the home’s food management, and the remaining respondents (8%) were male. It is indicated that women are taking the responsibility of cooking for a household in the selected areas. The respondents' ages ranged from 22 to 73, with a 44-year average. The average household size was 4, with sizes ranging from 1 to 10.

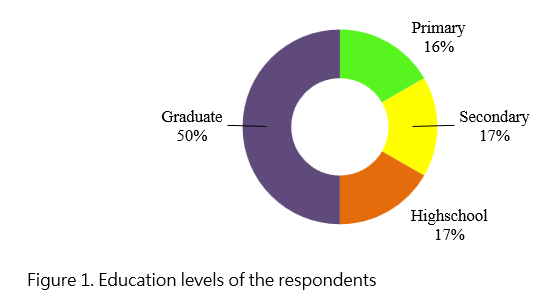

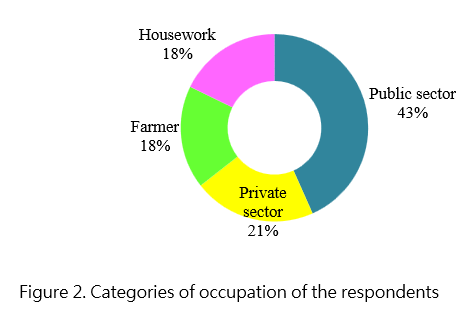

According to the survey’s findings, 16% of the total respondents had primary education, 34% had secondary and high school levels of education, and 50% of respondents had a graduate level of education. The education level of most of the sample respondents was graduates (Figure 1). Based on the categories of occupation, 18% of sample respondents were doing housework, 18% were farmers, and 21% of the respondents were employed in the private sector, while the rest (43%) of the total respondents worked in the public sector (Figure 2).

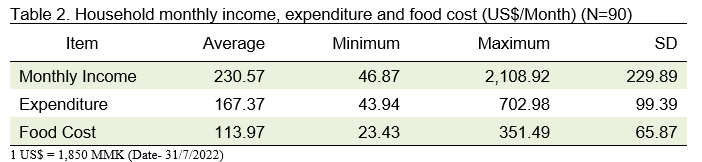

Table 2 shows the monthly income, expenses, and food costs for the sample households in the research area. The average monthly income of the sample households was US$230.57 which ranges from US$2,108.92 to US$46.87. The average monthly expense for sample households was US$167.37. The respondents’ average monthly food expenditure was US$113.97, with the highest and lowest amounts being US$351.49 and US$23.43, respectively. According to the surveyed data, the average ratio of households’ monthly food cost and their total expenditure was 0.68, and it is noted that the food cost of the household’s accounts for around two-third of the overall household expenditure. It tends to produce more food waste if households spend more money on food costs.

Shopping routines of the respondents

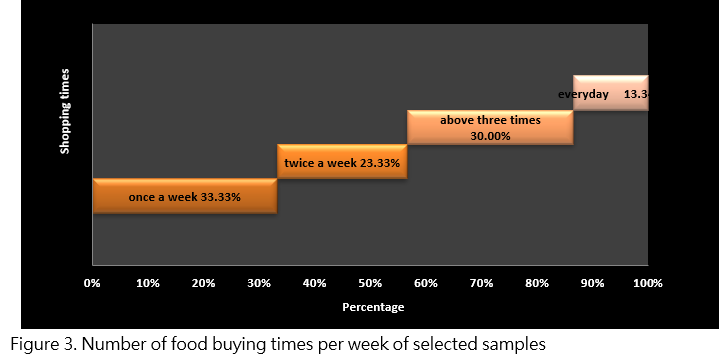

The respondents were also categorized according to their frequency of shopping, and the frequency of shopping t were divided into four (Figure 3). These include going shopping once a week, going shopping twice a week, going shopping thrice a week, and going shopping for food every day. Some respondents purchased foods in supermarkets, and most of the respondents purchased the foods in the local markets. According to the figure, 13% of the total respondents make buying of food every day while 33% of these respondents go to the markets once a week.

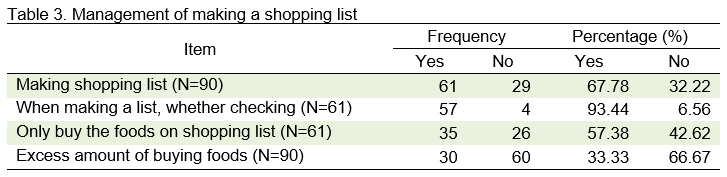

The proportion of sample households who are making a shopping list before buying foods was 68%, while the remaining proportion of households (32%) did not make the shopping list. Among the households who are doing a shopping list, most of the households (93%) looked into the fridge or cupboard before making the list. It can help the respondents not to buy more of the food they already have at home. Although the respondents are making a shopping list, almost half of the sample respondents did not only buy the foods according to the lists. Moreover, when consumers got the promotional offers, 33% of the total respondents purchased more foods than needed and thus promote the wasting of food (Table 3).

Conditions of food waste in the respondents’ house

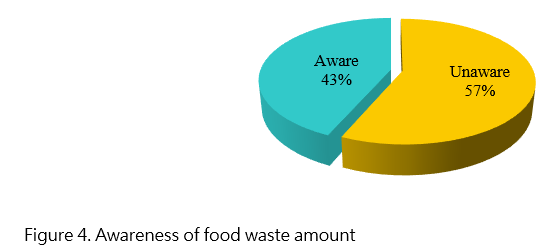

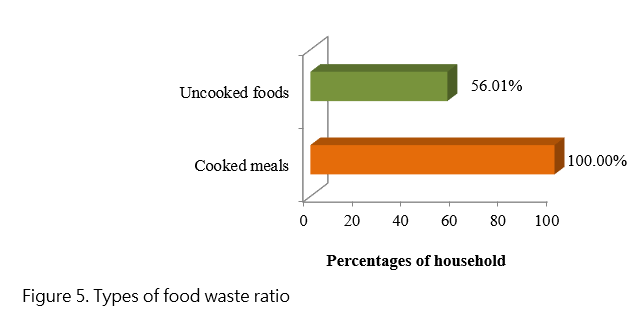

The respondents’ awareness level of the amount of food waste is shown in Figure 4. The awareness level was measured on whether the respondents knew they were fully aware of their food waste amount and types of food waste at home. Among the respondents, 43% of the respondents said they were fully aware of the quantity of food waste in their homes. However, 57% of the sample households were not aware of food waste amount. According to the types of food wastes (Figure 5), cooked meals were thrown away more than uncooked foods. All the households (100%) wasted cooked meals because household members did not eat the cooked meals for various reasons. But, only half of the sample households threw the uncooked foods away because they could not store those foods well. By looking at this, it was found that the housewives cooked food for the household members, but the household members did not eat the food cooked at home for various reasons.

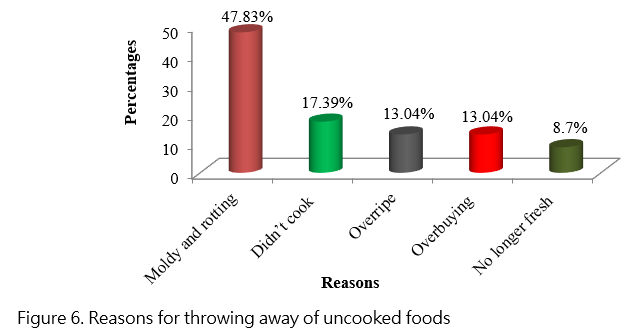

Figure 6 presents the explanations for why the sample households threw away uncooked foods (fruits and vegetables). Nearly 48% of all households responded that they had thrown away the raw foods because the foods were rotten and moldy. In addition, some respondents (13% and 17%) threw away the uncooked foods because they bought too much food and consequently could not cook the foods in time, respectively. In addition, 13% and 9% of all respondents said they tossed out uncooked food because it was too ripe and no longer fresh.

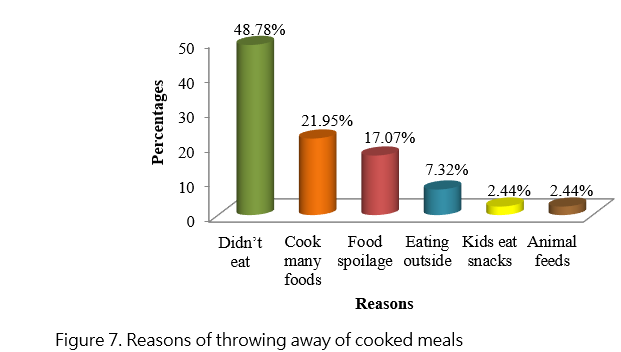

There are also numerous reasons why the sample respondents in the study area discarded cook meals (rice and curry). Almost half of all the households said that cooked meals were thrown away because household members did not eat the cooking foods, and 22% of the households said they disposed of the meals because of cooking too many foods. Moreover, 17% of total respondents mentioned that the cooked foods were discarded because of food spoilage. The sample respondents (7%) said that the cooking foods were disposed of because the family members were not eating their cooked meals, and they were eating outside a lot. The amount of food wasted also depends on how it is disposed of. Even though some amount of food waste was given to pets, just 2% of the respondents consider the food that is fed to animals, not food waste (Figure 7).

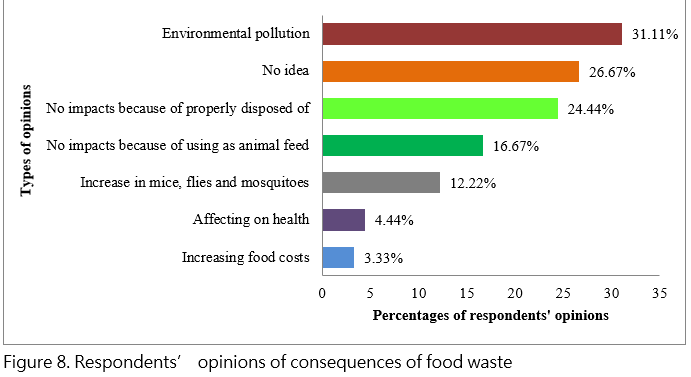

The following section presents the respondents’ opinions on the consequences of food waste. As shown in Figure 8, 31% of the respondents mentioned that large amounts of food waste have severe environmental pollution, while 27% of the respondents did not know the consequences of food waste. Moreover, over 40% of the sample households assumed that there were no negative effects from food waste because they were properly disposed of food waste and this waste was fed to pets. However, some respondents believed that it could increase the population of mice, flies, and mosquitoes around their environment because of food waste, and it can affect human health. In addition, 3% of the respondents answered that food waste could increase the rate of food costs.

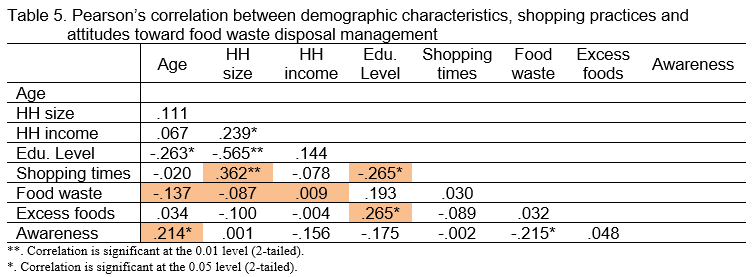

Relations between socio-demographic characteristics, shopping practices and attitudes towards food waste disposal management

A Pearson's Correlation analysis addressed the second goal of the investigation. According to Table 5, neither the respondents' family size nor their age significantly influenced their food waste behavior. However, these results are at odds with those of Stancu et al., (2015), who found a substantial correlation between food waste behavior and household size and age. The statistics collected from the survey show that there is no significant relationship between income level and food waste management. This outcome supports the findings of Wenlock et al., (1980) that there is no relationship between income level and food waste (Table 5).

Those with higher education were government employees or busy educated people. They only go to the market once a week as a result, and when they do, they are known to buy a lot regardless of actual requirement. It might make food waste more likely because of such actions. However, the household size of the respondents was positively related to their shopping times. Thus, the larger the respondents’ household size affects the greater the number of buying times for food. Studies have shown that older people are more aware of the amount of food waste in their homes (Table 5).

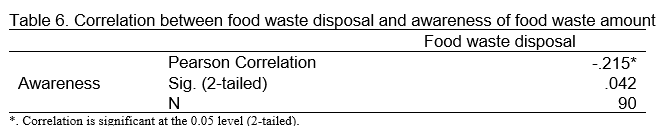

The relationship between sample households’ food waste disposal management and awareness of food waste amount is shown in Table 6. According to the data, there was a statistically significant negative relation between sample households’ food waste disposal and awareness of food waste amount (p<0.05). It means that high awareness of food waste amount could lead to reduction of food waste disposal in their household.

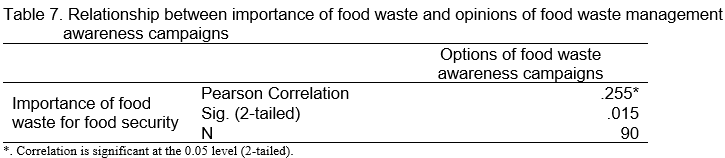

The result in Table 7 describes a correlation between respondents' thoughts on the importance of the food waste sector for food security and their opinions of programs to raise public awareness of food waste. A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the importance of the food waste sector for food security and opinions of food waste awareness management campaigns of the respondents (p<0.05). As a consequence, the sample respondents who believed that the food waste sector is crucial for ensuring food security stated that it is necessary to conduct food waste awareness management campaigns for food waste reduction.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the preliminary study in the Nay Pyi Taw region, women oversaw being the primary cooks for their families in around 92% of the sample households, and the average size of the household was 4. Among the surveyed households, the average ratio of food cost to total expenditure was 0.68, and it is indicated that the households are using about two-thirds of the total expenditure for food costs. Developing countries with a low standard of living and low income would have a high Engel coefficient because households are spending a large proportion of their income on food. Although 68% of the total respondents made the shopping list, almost 50% of those respondents did not purchase only the foods according to the lists.

Among the respondents, only 43% of the respondents were aware of their households’ food waste amounts. It is known that the most wasted food was cooked meals, and almost 50% of the respondents reported throwing away cooked meals because no one in the home ate the prepared foods. About one-third of the respondents responded that food waste could cause environmental pollution. According to the data, the respondents’ household size, age, and income were not significantly related to their households’ food waste disposal. But, the respondents’ age was positively correlated with the awareness levels of food waste amount. It is observed that the education levels of the respondents were significantly negative correlation with their shopping times. It is because those who are busy and highly educated bought many foods even once a week. The sample respondents answered that food waste awareness campaigns needed to be conducted for food waste reduction.

Food may be more likely to be disposed of on the soil due to the lack of proper waste management systems in developing countries. Food dumped in landfills could cause global warming because those foods decompose and release harmful methane gas into the atmosphere (Seberini, 2020). Food waste has become an increasingly important issue for government, businesses, and the public because it could damage the environment. Since most food waste occurs at the consumption stage, food waste reduction activities should systematically implement at that stage. Therefore, interventions should concentrate on improving the household perceptions of behavioral control over food waste to reduce household food waste. In doing so, educational activities should be carried out to teach the households how to plan for food shopping and how to preserve food appropriately after it has been purchased. Moreover, informational programs aimed at the households with the goal of improving people knowledge about food waste could also help prevent many of the causes of food waste. Additionally, it is necessary and has to consider about new evidence-based policies to reduce food waste toward food security, green, clean, healthy environment of circular economy improvement in Myanmar. Furthermore, nationwide researches to cover food waste management at household, municipal and community levels in different regions should be carried out in Myanmar.

REFERENCES

Di Talia, E., Simeone, M., & Scarpato, D. (2019). Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 166-172.

Food Waste: The Complete 2021 Guide. (2021). Retrieved March 28, 2022, from Cheaperwaste.co.uk: https://www.cheaperwaste.co.uk/blog/food-waste-the-complete-2020-guide/

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., Van Otterdijk, R., Meybeck, A. (2011). Global food losses and food waste. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rom.

Morgan, E. (2009). Fruit and vegetable consumption and waste in Australia. State Government of Victoria, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Victoria, Australia, 1–58.

Schanes, K., Dobernig, K., & Gözet, B. (2018). Food waste matters - A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 978-991.

Seberini, A. (2020). Economic, social and environmental world impacts of food waste on society and zero waste as a global approach to their elimination. SHS Web of Conferences, 74.

Stancu, V., Haugaard, P., & Lähteenmä, L. (2015). Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: two routes to food waste. Appetite.

UN Food Systems Summit (Secretary-General’s Chair Summary and Statement of Action). (2021). Retrieved March 29, 2022, from Food Systems Summit 2021 (United Nations): https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit/news/making-food-systems-work-people-planet-and-prosperity

Visschers, V. H., Wickli, N., & Siegrist, M. (2016). Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 66-78.

Wenlock, R., Buss, D., Derry, B., Dixon, E. (1980). Household food wastage in Britain. British Journal of Nutrition, 43, 53-70.

Household Food Waste Management in Nay Pyi Taw: Towards Green, Clean and Healthy Environment

ABSTRACT

In recent years, the food waste issue has received growing interest within the government, businesses, and the general public because it could cause food insecurity and environmental pollution. Various factors contribute to food waste during the stages of food production, processing, retailing, and consumption. Moreover, households and consumers both directly and indirectly cause a significant quantity of food waste. This study is a preliminary study to describe the household behaviors regarding the management of food waste and to analyze the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and attitudes toward food waste disposal at the household level. Using structured questionnaires, the data were collected from 90 purposive randomly selected households in the Nay Pyi Taw area. The findings indicated that most of the sample respondents who cook the main meals at home were women, and the households were using about two-thirds of the total expenditure for food costs. Among the surveyed households, two-thirds of the respondents made a shopping list, but they did not buy only the foods on the list. Moreover, they purchased an excess amount of food when they obtained the promotional offers. Almost half of the sample respondents were aware of their households’ food waste amounts, and the most wasted food was cooked meals. The most common reason for throwing away cooked meals was household members did not eat the prepared foods. The results indicated that the age of the respondents was positively associated with the respondents’ awareness level of food waste amount while the education level of the respondents was negatively correlated with their shopping times per week. The sample respondents said that food waste management awareness campaigns needed to be implemented for food waste reduction. In addition, it needs to adopt new policies to reduce food waste for the public towards food security and growing attention on green, clean and healthy environment in the circular economy. Further studies to cover food waste management at the household, municipal and community levels in different regions should be carried out in Myanmar.

Keywords: Food waste management, consumer behavior, socio-demographic characteristics, awareness

INTRODUCTION

Every year, almost one-third of all the food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost (Gustavsson et al., 2011). At the international level, the importance of the theme of food loss and waste has led to a significant increase in scientific production (Di Talia, Simeone, & Scarpato, 2019). Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) target 12.3 asks for halving global per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels by 2030, and eliminating food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses. The UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 emphasized the importance of food loss and waste reduction to create a sustainable food system and meet all 17 SDGs (UN Food Systems Summit, 2021).

Food waste means uneaten food that refers to unused or discarded food. Food waste occurs from various causes, including the loss of potentially valuable food products during the food production, processing, retailing, and consumption stages (Food Waste, 2021). The perishable home-used products, such as bakery and dairy products, fruits and vegetables, and meat and fish, are the most wasted (Morgan, 2009). Food losses have negative economic and environmental consequences, affecting valuable resources such as land, water, and energy, as well as incurred expenditures that are never recovered.

Both directly and indirectly, households and consumers are responsible for a large amount of food waste. Food loss at the consumption stage is a direct result of consumer purchasing habits (Di Talia, Simeone, & Scarpato, 2019). The main reason for food waste at the consumption stage is people do not store, prepare or cook the foods correctly. Furthermore, people are throwing edible food away because they thought it was spoilt; or because it had actually spoilt, but the consumer never got around to using it in time.

Numerous studies have sought to investigate how consumers think about and behave when it comes to food waste because households and consumers are the main producers of food waste (Visschers, Wickli, & Siegrist, 2016). Moreover, understanding the contextual factors influencing consumers' food waste management behavior could help develop strategies and policies for food waste reduction in the country. However, there is very few research on consumer food waste management behaviors in Myanmar. Therefore, this study aims to identify the respondents’ attitudes and behaviors regarding food waste management in randomly chosen households in the Nay Pyi Taw region, Myanmar.

Objectives of the study

METHODOLOGY

Study sites and sample selection for data collection

Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships are eight administrative townships in the Nay Pyi Taw region, as per data from the Department of Population (2015). These townships were chosen as the preliminary study locations. The study areas have a variety of household clusters, including government staff, private company staff, and farmers. In this study, the members of the household who spend more time in the kitchen and are more conscious of the financial waste associated with throwing food out were selected as the prospective sample respondents.

Data collection and data analysis

A field survey for primary data collecting was undertaken in November 2021 to gather the respondents' views and behaviors around food waste in Nay Pyi Taw. For the data collection, the enumerators went door-to-door to the households, explained the purpose of the study, and requested their voluntary participation in the survey. The face-to-face interview was conducted utilizing the structured questionnaire if the respondent agreed to participate in the study. Using the purposive random sampling method, 90 respondents for the study were selected.

The questionnaire's initial section asked about the socio-demographic details of the sample respondents, and it was followed by a series of inquiries into the attitudes and practices of the respondents regarding food waste. The collected information was converted to digital form, then compiled and delivered into a pre-defined format to evaluate outcomes. Results were obtained after the data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS statistical software. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample respondents in the study were calculated using descriptive statistics. Pearson's Correlation test was utilized to measure the statistical relationship between the respondents' socio-demographic traits and their attitudes toward food waste disposal.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic information of sample respondents

The demographic characteristics of 90 sample respondents from the study area are described in Table 1. Among the sample respondents, the majority of the respondents (92%) were female who mostly handle the home’s food management, and the remaining respondents (8%) were male. It is indicated that women are taking the responsibility of cooking for a household in the selected areas. The respondents' ages ranged from 22 to 73, with a 44-year average. The average household size was 4, with sizes ranging from 1 to 10.

According to the survey’s findings, 16% of the total respondents had primary education, 34% had secondary and high school levels of education, and 50% of respondents had a graduate level of education. The education level of most of the sample respondents was graduates (Figure 1). Based on the categories of occupation, 18% of sample respondents were doing housework, 18% were farmers, and 21% of the respondents were employed in the private sector, while the rest (43%) of the total respondents worked in the public sector (Figure 2).

Table 2 shows the monthly income, expenses, and food costs for the sample households in the research area. The average monthly income of the sample households was US$230.57 which ranges from US$2,108.92 to US$46.87. The average monthly expense for sample households was US$167.37. The respondents’ average monthly food expenditure was US$113.97, with the highest and lowest amounts being US$351.49 and US$23.43, respectively. According to the surveyed data, the average ratio of households’ monthly food cost and their total expenditure was 0.68, and it is noted that the food cost of the household’s accounts for around two-third of the overall household expenditure. It tends to produce more food waste if households spend more money on food costs.

Shopping routines of the respondents

The respondents were also categorized according to their frequency of shopping, and the frequency of shopping t were divided into four (Figure 3). These include going shopping once a week, going shopping twice a week, going shopping thrice a week, and going shopping for food every day. Some respondents purchased foods in supermarkets, and most of the respondents purchased the foods in the local markets. According to the figure, 13% of the total respondents make buying of food every day while 33% of these respondents go to the markets once a week.

The proportion of sample households who are making a shopping list before buying foods was 68%, while the remaining proportion of households (32%) did not make the shopping list. Among the households who are doing a shopping list, most of the households (93%) looked into the fridge or cupboard before making the list. It can help the respondents not to buy more of the food they already have at home. Although the respondents are making a shopping list, almost half of the sample respondents did not only buy the foods according to the lists. Moreover, when consumers got the promotional offers, 33% of the total respondents purchased more foods than needed and thus promote the wasting of food (Table 3).

Conditions of food waste in the respondents’ house

The respondents’ awareness level of the amount of food waste is shown in Figure 4. The awareness level was measured on whether the respondents knew they were fully aware of their food waste amount and types of food waste at home. Among the respondents, 43% of the respondents said they were fully aware of the quantity of food waste in their homes. However, 57% of the sample households were not aware of food waste amount. According to the types of food wastes (Figure 5), cooked meals were thrown away more than uncooked foods. All the households (100%) wasted cooked meals because household members did not eat the cooked meals for various reasons. But, only half of the sample households threw the uncooked foods away because they could not store those foods well. By looking at this, it was found that the housewives cooked food for the household members, but the household members did not eat the food cooked at home for various reasons.

Figure 6 presents the explanations for why the sample households threw away uncooked foods (fruits and vegetables). Nearly 48% of all households responded that they had thrown away the raw foods because the foods were rotten and moldy. In addition, some respondents (13% and 17%) threw away the uncooked foods because they bought too much food and consequently could not cook the foods in time, respectively. In addition, 13% and 9% of all respondents said they tossed out uncooked food because it was too ripe and no longer fresh.

There are also numerous reasons why the sample respondents in the study area discarded cook meals (rice and curry). Almost half of all the households said that cooked meals were thrown away because household members did not eat the cooking foods, and 22% of the households said they disposed of the meals because of cooking too many foods. Moreover, 17% of total respondents mentioned that the cooked foods were discarded because of food spoilage. The sample respondents (7%) said that the cooking foods were disposed of because the family members were not eating their cooked meals, and they were eating outside a lot. The amount of food wasted also depends on how it is disposed of. Even though some amount of food waste was given to pets, just 2% of the respondents consider the food that is fed to animals, not food waste (Figure 7).

The following section presents the respondents’ opinions on the consequences of food waste. As shown in Figure 8, 31% of the respondents mentioned that large amounts of food waste have severe environmental pollution, while 27% of the respondents did not know the consequences of food waste. Moreover, over 40% of the sample households assumed that there were no negative effects from food waste because they were properly disposed of food waste and this waste was fed to pets. However, some respondents believed that it could increase the population of mice, flies, and mosquitoes around their environment because of food waste, and it can affect human health. In addition, 3% of the respondents answered that food waste could increase the rate of food costs.

Relations between socio-demographic characteristics, shopping practices and attitudes towards food waste disposal management

A Pearson's Correlation analysis addressed the second goal of the investigation. According to Table 5, neither the respondents' family size nor their age significantly influenced their food waste behavior. However, these results are at odds with those of Stancu et al., (2015), who found a substantial correlation between food waste behavior and household size and age. The statistics collected from the survey show that there is no significant relationship between income level and food waste management. This outcome supports the findings of Wenlock et al., (1980) that there is no relationship between income level and food waste (Table 5).

Those with higher education were government employees or busy educated people. They only go to the market once a week as a result, and when they do, they are known to buy a lot regardless of actual requirement. It might make food waste more likely because of such actions. However, the household size of the respondents was positively related to their shopping times. Thus, the larger the respondents’ household size affects the greater the number of buying times for food. Studies have shown that older people are more aware of the amount of food waste in their homes (Table 5).

The relationship between sample households’ food waste disposal management and awareness of food waste amount is shown in Table 6. According to the data, there was a statistically significant negative relation between sample households’ food waste disposal and awareness of food waste amount (p<0.05). It means that high awareness of food waste amount could lead to reduction of food waste disposal in their household.

The result in Table 7 describes a correlation between respondents' thoughts on the importance of the food waste sector for food security and their opinions of programs to raise public awareness of food waste. A statistically significant positive correlation was found between the importance of the food waste sector for food security and opinions of food waste awareness management campaigns of the respondents (p<0.05). As a consequence, the sample respondents who believed that the food waste sector is crucial for ensuring food security stated that it is necessary to conduct food waste awareness management campaigns for food waste reduction.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the preliminary study in the Nay Pyi Taw region, women oversaw being the primary cooks for their families in around 92% of the sample households, and the average size of the household was 4. Among the surveyed households, the average ratio of food cost to total expenditure was 0.68, and it is indicated that the households are using about two-thirds of the total expenditure for food costs. Developing countries with a low standard of living and low income would have a high Engel coefficient because households are spending a large proportion of their income on food. Although 68% of the total respondents made the shopping list, almost 50% of those respondents did not purchase only the foods according to the lists.

Among the respondents, only 43% of the respondents were aware of their households’ food waste amounts. It is known that the most wasted food was cooked meals, and almost 50% of the respondents reported throwing away cooked meals because no one in the home ate the prepared foods. About one-third of the respondents responded that food waste could cause environmental pollution. According to the data, the respondents’ household size, age, and income were not significantly related to their households’ food waste disposal. But, the respondents’ age was positively correlated with the awareness levels of food waste amount. It is observed that the education levels of the respondents were significantly negative correlation with their shopping times. It is because those who are busy and highly educated bought many foods even once a week. The sample respondents answered that food waste awareness campaigns needed to be conducted for food waste reduction.

Food may be more likely to be disposed of on the soil due to the lack of proper waste management systems in developing countries. Food dumped in landfills could cause global warming because those foods decompose and release harmful methane gas into the atmosphere (Seberini, 2020). Food waste has become an increasingly important issue for government, businesses, and the public because it could damage the environment. Since most food waste occurs at the consumption stage, food waste reduction activities should systematically implement at that stage. Therefore, interventions should concentrate on improving the household perceptions of behavioral control over food waste to reduce household food waste. In doing so, educational activities should be carried out to teach the households how to plan for food shopping and how to preserve food appropriately after it has been purchased. Moreover, informational programs aimed at the households with the goal of improving people knowledge about food waste could also help prevent many of the causes of food waste. Additionally, it is necessary and has to consider about new evidence-based policies to reduce food waste toward food security, green, clean, healthy environment of circular economy improvement in Myanmar. Furthermore, nationwide researches to cover food waste management at household, municipal and community levels in different regions should be carried out in Myanmar.

REFERENCES

Di Talia, E., Simeone, M., & Scarpato, D. (2019). Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 214, 166-172.

Food Waste: The Complete 2021 Guide. (2021). Retrieved March 28, 2022, from Cheaperwaste.co.uk: https://www.cheaperwaste.co.uk/blog/food-waste-the-complete-2020-guide/

Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C., Sonesson, U., Van Otterdijk, R., Meybeck, A. (2011). Global food losses and food waste. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rom.

Morgan, E. (2009). Fruit and vegetable consumption and waste in Australia. State Government of Victoria, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Victoria, Australia, 1–58.

Schanes, K., Dobernig, K., & Gözet, B. (2018). Food waste matters - A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 978-991.

Seberini, A. (2020). Economic, social and environmental world impacts of food waste on society and zero waste as a global approach to their elimination. SHS Web of Conferences, 74.

Stancu, V., Haugaard, P., & Lähteenmä, L. (2015). Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: two routes to food waste. Appetite.

UN Food Systems Summit (Secretary-General’s Chair Summary and Statement of Action). (2021). Retrieved March 29, 2022, from Food Systems Summit 2021 (United Nations): https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit/news/making-food-systems-work-people-planet-and-prosperity

Visschers, V. H., Wickli, N., & Siegrist, M. (2016). Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 66-78.

Wenlock, R., Buss, D., Derry, B., Dixon, E. (1980). Household food wastage in Britain. British Journal of Nutrition, 43, 53-70.