ABSTRACT

After the income compensation program for rice was changed to basic direct payment, Rice farmers were very concerned that rice price volatility would increase. The Korean government amended the existing Grain Management Act to dispel the concerns of rice farmers and to successfully reform the public-purpose payment program. In the amended law, the government sets out in more detail the conditions when rice can be purchased and sold by the government. This can bring about the effect of lowering the volatility of the rice price, but at the same time it can also lead to the side effect of maintaining the structural oversupply of rice.

Keywords: Rice Policy, Grain Management Act, Public-purpose direct payment program

INTRODUCTION

Policy background

The Korean government implemented the rice policy reform in 2005 with the goal of improving the rice industry's competitiveness and bolstering food security. The reform's central objective was to eliminate the government purchase program and replace it with a public reserve program to prepare for disasters and emergencies, with the supply and demand of rice handled by the market mechanism. The "Direct Payment Program for Preserving Rice Revenue," which integrated and strengthened the current rice-related direct payment system, was developed to help rice farmers maintain their income during the implementation phase.

The Direct Payment Program for Rice Income Preservation is a hybrid of the rice income preservation program in the form of fixed direct payments, which began in 2001, and the rice income preservation program in the form of variable direct payments tied to the target price, which began in 2003. The unit price of a fixed direct payment per area has increased by more than twofold. In addition, when compared to the target price, the variable direct payment preservation rate increased from 80% to 85% of the target price. However, according to Ahn (2015), there is a production incentive impact due to the element of paying direct payment on the premise of producing rice, as well as the effect of preserving income compared to other crops.

Then again, Korean individual’s consumption of rice is continuously diminishing because of the impact of expanding pay and seeking after different food societies. The current per capita consumption of rice is 57.7kg in 2019, which is not exactly 50% of that in the mid-1980s. Therefore, there were slight changes each year relying on the yield conditions, yet the oversupply pattern of rice, which is more stock than request, is proceeding.

Also, Park (2016) summed up the fundamental issues raised over the Direct Payment Program for Preserving Rice Income as follows. In the first place, there is an absence of value between agrarian items because of the help zeroed in on rice. Second, there is a disparity issue as far as pay rearrangement where huge farmers get an excess of help contrasted with little farmers, since the installment is determined in direct extent to the farm size.

The Public-purpose direct payment program was implemented in 2020 to address the lack of parity amongst agricultural goods caused by the rice-focused direct payment system and the concentration of support on large farms with a unit pricing system proportional to the area. The program adheres to environmental and ecological protection regulations, such as maintaining the shape and function of farmlands and adhering to pesticide and chemical fertilizer standards. Direct payments were paid regardless of whether a specific item was cultivated or not. The rice support policy, which had been identified as a problem in the current direct payment system, was corrected because of this, and the new program was not designed to stimulate rice production.

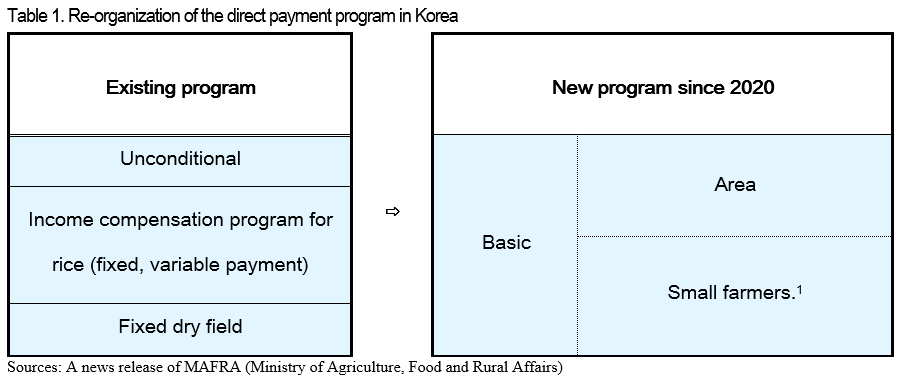

In short, the Korean government reorganized the existing direct payment system to the public-purpose payment program in 2020. The public-purpose direct payment program is composed of basic and optional direct payments. Basic direct payment is a combination of three existing direct payment systems (income compensation program for rice, fixed dry field, and unconditional direct payment). The income compensation program for rice set a target price, for the difference between the target price and the market price, 85% of the amount was paid as a subsidy. As a result, with the introduction of the public-purpose direct payment program, the income compensation program for rice was changed to basic direct payment. It does not compensate for falling rice prices so that rice farmers expressed strong concerns that the price preservation function would be weakened. In the context of such concerns, the Korean government amended the Grain Management Act to materialize policy measures for stabilizing the supply and demand of rice and price of rice in order to relieve the anxiety of rice farmers.

Contents of amendment

The amended provisions are related to the supply and demand management of rice for price stabilization as Article 16. In the former law, if the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs deems it necessary for controlling the release of grains and the price thereof, he/she may allow agricultural cooperatives and other persons designated by Presidential Decree to purchase and sell rice. In such cases, he/she may provide the funds required for the purchase thereof within budgetary limits. In short, prior to the amendment of the law, it was determined that the government could purchase and sell rice through the Agricultural Cooperatives and Presidential Decree to control the supply and demand of rice and control the rice price. However, it did not set specific conditions.

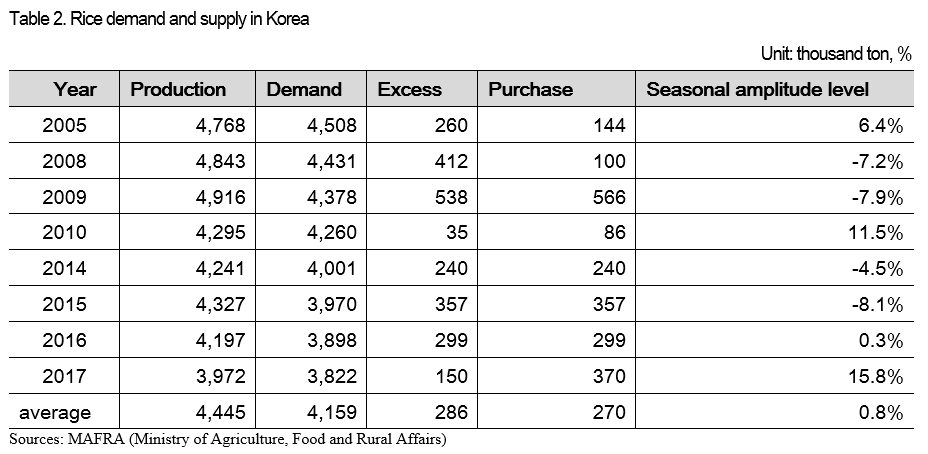

Since 2005, when rice policy reform was implemented, the government has purchased a total of eight times to stabilize rice prices. The average amount of excess production was 286,000 tons, which accounted for 6.3% of the production volume, and the purchase volume was 270,000 tons, which was less than the excess production volume. There was a total of two years of purchasing less than excess production in 2005 and 2008, and the same purchases were made three times in 2014, 2015, and 2016, and the year in which more than excess production was purchased for a total of three times in 2009, 2010, and 2017.

The average price of rice during the harvest season in the year when the government purchased rice was on average 7.0% lower than that of the normal year. In all years except for 2008 and 2014, prices fell significantly compared to the normal year. The price of 2008 was higher than that of the average year, but the amount of excess production was 412,000 tons, and the government purchased in 2014 due to concerns about price drop due to tariffication on rice.[2] After the launch of the WTO, Korea was permitted to delay tariffication on rice until 2014. However, the Korean government decided to open its rice market by imposing tariff in 2014. Rice farmers were concerned that if rice imports were liberalized, the price of domestic rice would fall sharply due to an increase in rice imports. However, in reality, imports of rice hardly increased, and the effect on domestic rice prices was very limited.

Comparing the seasonal amplitude levels according to the size of the government purchases to the excess production, the reverse seasonal amplitude of 2.6% occurred when the purchase was less than or equal to the excess production, and 6.5% of the seasonal amplitude was obtained when the excess production was purchased. The effect of price increase was greater when purchasing a large quantity compared to excess production. In the case of 2014, 2015, and 2016 productions, despite purchasing the same amount as the excess production, private inventory accumulation due to reduced consumption and psychological unrest due to the continued occurrence of reverse seasonal amplitudes acted as factors for the price drop.[3]

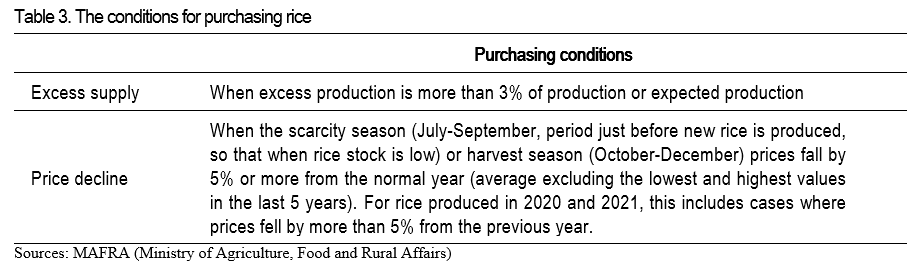

On the other hand, in the amended law, the government sets out in more detail the circumstances when rice can be purchased and sold. There are two main conditions under which the government can purchase rice. The first case is when production exceeds demand for the year by more than a certain level. The second case is when the price of rice fluctuates or is expected to change rapidly. The reason for setting the price standards in parallel is that there is a limit to the accuracy of rice statistics, and if there is a series of surpluses to the level that the government does not implement purchasing, a price drop may occur.

At this time, matters related to the method of estimating the production and demand of rice in that year, degree of price fluctuation to purchase rice, the calculation of the purchase quantity, the timing and procedure of purchase, conditions for selling government stock rice etc. were to be decided by the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs in consultation with the representatives of farmers' organizations and the consumer organization.

Another characteristic of the amended provisions of the law is that it imposes an obligation to establish and implement a rice supply and demand stabilization policy within a specified time every year.[4] The reason for specifying the establishment period of the supply-demand stabilization measures is to prevent market fluctuations by announcing the measures at the beginning of the harvest season.

The Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs set up the conditions for purchasing rice, which are listed in the table below. However, the government does not automatically purchase rice even if the conditions set out below are met. Whether or not to purchase rice is a comprehensive decision made by the government on the premise that the purchase conditions are met. When the government purchases rice, the price is based on the market average price.

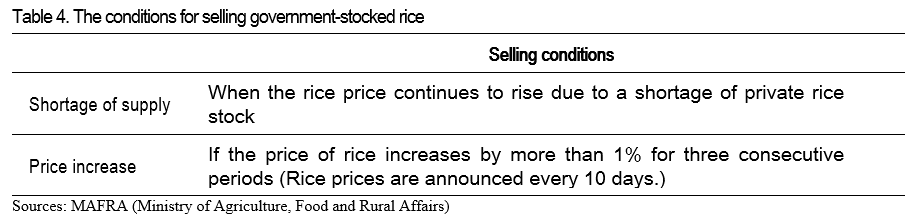

The Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs can make a decision to sell government-owned rice if the rice price continues to rise due to a shortage of private rice stock. By the way, if the price rises by more than 1% for three consecutive periods, the government stocked rice must be sold unless there is a special reason.[4] The sales volume is determined by the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, taking into consideration the production volume, demand volume, and price trend. When the government sells rice, there are no special regulations regarding the price of rice, but it is common to sell rice at a lower price than the market average price because the price of rice is generally high because there is not enough rice in stock in the market.

In addition, it stipulates matters related to adjustments of rice cultivation area following the implementation of purchasing excess rice. In other words, after the government purchases rice, the government can instruct rice farmers to reduce the rice cultivation area. If the government does not implement these measures to producers after the purchase of rice, there is a high risk that the rice cultivation area will not be sufficiently reduced due to the high stability of rice prices.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Even before the Grain Management Act was amended, most of the years when there was an oversupply of rice, the Korean government purchased rice. For example, from 2005 to 2019, there were 12 oversupply occurrences, of which the government purchased rice 8 times. However, it took a lot of time to make policy decisions, such as in some years when rice was purchased long after the harvest season. Therefore, through the amendment of the Grain Management Act, it is expected that the decrease in rice prices will be minimized by the government deciding whether to purchase rice at the beginning of the harvest season in the year of rice oversupply.

On the other hand, the revision of the Grain Management Act may result as contrary to the policy purpose intended by the reorganization of the public-purpose direct payment program. Because the amendment to the Grain Management Act may have the effect of minimizing the decline in rice prices, so the price risk is smaller than other non-rice crops. Because of that reason, rice farmers may still want to continue to cultivate rice. Even though the government aimed to alleviate the structural oversupply of rice by revising policies that were favorable to rice through the reorganization of the direct payment system.

Therefore, in order to avoid such side effects, it is necessary to share the responsibility with producers after the government purchases rice due to oversupply or price drop, which is stipulated in the amended Grain Management Act. Rice farmers also need to understand the purpose of this system and make efforts on their own to resolve the structural oversupply of rice.

REFERENCES

B. I. Ahn, Analysis of the Influences of Direct Payment Policy on the Rice Acreage, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy, 42(3), 2015, 467-486

J. K. Park, N. W. Oh, C. H. Ryu, J. I. Kim, J. Y. Park, Analysis of the operation status and development plan of the agricultural direct payment program, Korea Rural Economics Institute, 2016.

Grain Management Act, Act No. 17761, January 29, 2020

MAFRA (Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs)

[1]The direct payment for small farmers denotes that 1.2 million won (Assuming that one US dollar is 1,000 won, it is equivalent to about 1,200 US dollars.) is paid to farmers who meet the requirements among farms with 0.5 ha or less. However, even if the farm is less than 0.5 ha, if the payment requirements (There are 8 mandatory conditions including area conditions.) are not met, direct payment in proportion to the area is paid.

[2] The rice harvest season is from October to December. The normal year means the average value excluding the year with the highest number and the year with the lowest number among the past five years.

[3] Seasonal amplitude levels mean the price gap difference between harvest and short season. The rice harvest season is from October to December and the short season is from July to September.

[4] October 15, the beginning of the rice harvest season, was set as the deadline. However, if it is difficult to predict the production volume for the year due to sudden changes in weather conditions, the deadline may be extended.

[5] Because the price of rice is announced every 10 days, it corresponds to one month.

The Contents and Meaning of Amendments of Korea’s Grain Management Act

ABSTRACT

After the income compensation program for rice was changed to basic direct payment, Rice farmers were very concerned that rice price volatility would increase. The Korean government amended the existing Grain Management Act to dispel the concerns of rice farmers and to successfully reform the public-purpose payment program. In the amended law, the government sets out in more detail the conditions when rice can be purchased and sold by the government. This can bring about the effect of lowering the volatility of the rice price, but at the same time it can also lead to the side effect of maintaining the structural oversupply of rice.

Keywords: Rice Policy, Grain Management Act, Public-purpose direct payment program

INTRODUCTION

Policy background

The Korean government implemented the rice policy reform in 2005 with the goal of improving the rice industry's competitiveness and bolstering food security. The reform's central objective was to eliminate the government purchase program and replace it with a public reserve program to prepare for disasters and emergencies, with the supply and demand of rice handled by the market mechanism. The "Direct Payment Program for Preserving Rice Revenue," which integrated and strengthened the current rice-related direct payment system, was developed to help rice farmers maintain their income during the implementation phase.

The Direct Payment Program for Rice Income Preservation is a hybrid of the rice income preservation program in the form of fixed direct payments, which began in 2001, and the rice income preservation program in the form of variable direct payments tied to the target price, which began in 2003. The unit price of a fixed direct payment per area has increased by more than twofold. In addition, when compared to the target price, the variable direct payment preservation rate increased from 80% to 85% of the target price. However, according to Ahn (2015), there is a production incentive impact due to the element of paying direct payment on the premise of producing rice, as well as the effect of preserving income compared to other crops.

Then again, Korean individual’s consumption of rice is continuously diminishing because of the impact of expanding pay and seeking after different food societies. The current per capita consumption of rice is 57.7kg in 2019, which is not exactly 50% of that in the mid-1980s. Therefore, there were slight changes each year relying on the yield conditions, yet the oversupply pattern of rice, which is more stock than request, is proceeding.

Also, Park (2016) summed up the fundamental issues raised over the Direct Payment Program for Preserving Rice Income as follows. In the first place, there is an absence of value between agrarian items because of the help zeroed in on rice. Second, there is a disparity issue as far as pay rearrangement where huge farmers get an excess of help contrasted with little farmers, since the installment is determined in direct extent to the farm size.

The Public-purpose direct payment program was implemented in 2020 to address the lack of parity amongst agricultural goods caused by the rice-focused direct payment system and the concentration of support on large farms with a unit pricing system proportional to the area. The program adheres to environmental and ecological protection regulations, such as maintaining the shape and function of farmlands and adhering to pesticide and chemical fertilizer standards. Direct payments were paid regardless of whether a specific item was cultivated or not. The rice support policy, which had been identified as a problem in the current direct payment system, was corrected because of this, and the new program was not designed to stimulate rice production.

In short, the Korean government reorganized the existing direct payment system to the public-purpose payment program in 2020. The public-purpose direct payment program is composed of basic and optional direct payments. Basic direct payment is a combination of three existing direct payment systems (income compensation program for rice, fixed dry field, and unconditional direct payment). The income compensation program for rice set a target price, for the difference between the target price and the market price, 85% of the amount was paid as a subsidy. As a result, with the introduction of the public-purpose direct payment program, the income compensation program for rice was changed to basic direct payment. It does not compensate for falling rice prices so that rice farmers expressed strong concerns that the price preservation function would be weakened. In the context of such concerns, the Korean government amended the Grain Management Act to materialize policy measures for stabilizing the supply and demand of rice and price of rice in order to relieve the anxiety of rice farmers.

Contents of amendment

The amended provisions are related to the supply and demand management of rice for price stabilization as Article 16. In the former law, if the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs deems it necessary for controlling the release of grains and the price thereof, he/she may allow agricultural cooperatives and other persons designated by Presidential Decree to purchase and sell rice. In such cases, he/she may provide the funds required for the purchase thereof within budgetary limits. In short, prior to the amendment of the law, it was determined that the government could purchase and sell rice through the Agricultural Cooperatives and Presidential Decree to control the supply and demand of rice and control the rice price. However, it did not set specific conditions.

Since 2005, when rice policy reform was implemented, the government has purchased a total of eight times to stabilize rice prices. The average amount of excess production was 286,000 tons, which accounted for 6.3% of the production volume, and the purchase volume was 270,000 tons, which was less than the excess production volume. There was a total of two years of purchasing less than excess production in 2005 and 2008, and the same purchases were made three times in 2014, 2015, and 2016, and the year in which more than excess production was purchased for a total of three times in 2009, 2010, and 2017.

The average price of rice during the harvest season in the year when the government purchased rice was on average 7.0% lower than that of the normal year. In all years except for 2008 and 2014, prices fell significantly compared to the normal year. The price of 2008 was higher than that of the average year, but the amount of excess production was 412,000 tons, and the government purchased in 2014 due to concerns about price drop due to tariffication on rice.[2] After the launch of the WTO, Korea was permitted to delay tariffication on rice until 2014. However, the Korean government decided to open its rice market by imposing tariff in 2014. Rice farmers were concerned that if rice imports were liberalized, the price of domestic rice would fall sharply due to an increase in rice imports. However, in reality, imports of rice hardly increased, and the effect on domestic rice prices was very limited.

Comparing the seasonal amplitude levels according to the size of the government purchases to the excess production, the reverse seasonal amplitude of 2.6% occurred when the purchase was less than or equal to the excess production, and 6.5% of the seasonal amplitude was obtained when the excess production was purchased. The effect of price increase was greater when purchasing a large quantity compared to excess production. In the case of 2014, 2015, and 2016 productions, despite purchasing the same amount as the excess production, private inventory accumulation due to reduced consumption and psychological unrest due to the continued occurrence of reverse seasonal amplitudes acted as factors for the price drop.[3]

On the other hand, in the amended law, the government sets out in more detail the circumstances when rice can be purchased and sold. There are two main conditions under which the government can purchase rice. The first case is when production exceeds demand for the year by more than a certain level. The second case is when the price of rice fluctuates or is expected to change rapidly. The reason for setting the price standards in parallel is that there is a limit to the accuracy of rice statistics, and if there is a series of surpluses to the level that the government does not implement purchasing, a price drop may occur.

At this time, matters related to the method of estimating the production and demand of rice in that year, degree of price fluctuation to purchase rice, the calculation of the purchase quantity, the timing and procedure of purchase, conditions for selling government stock rice etc. were to be decided by the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs in consultation with the representatives of farmers' organizations and the consumer organization.

Another characteristic of the amended provisions of the law is that it imposes an obligation to establish and implement a rice supply and demand stabilization policy within a specified time every year.[4] The reason for specifying the establishment period of the supply-demand stabilization measures is to prevent market fluctuations by announcing the measures at the beginning of the harvest season.

The Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs set up the conditions for purchasing rice, which are listed in the table below. However, the government does not automatically purchase rice even if the conditions set out below are met. Whether or not to purchase rice is a comprehensive decision made by the government on the premise that the purchase conditions are met. When the government purchases rice, the price is based on the market average price.

The Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs can make a decision to sell government-owned rice if the rice price continues to rise due to a shortage of private rice stock. By the way, if the price rises by more than 1% for three consecutive periods, the government stocked rice must be sold unless there is a special reason.[4] The sales volume is determined by the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, taking into consideration the production volume, demand volume, and price trend. When the government sells rice, there are no special regulations regarding the price of rice, but it is common to sell rice at a lower price than the market average price because the price of rice is generally high because there is not enough rice in stock in the market.

In addition, it stipulates matters related to adjustments of rice cultivation area following the implementation of purchasing excess rice. In other words, after the government purchases rice, the government can instruct rice farmers to reduce the rice cultivation area. If the government does not implement these measures to producers after the purchase of rice, there is a high risk that the rice cultivation area will not be sufficiently reduced due to the high stability of rice prices.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Even before the Grain Management Act was amended, most of the years when there was an oversupply of rice, the Korean government purchased rice. For example, from 2005 to 2019, there were 12 oversupply occurrences, of which the government purchased rice 8 times. However, it took a lot of time to make policy decisions, such as in some years when rice was purchased long after the harvest season. Therefore, through the amendment of the Grain Management Act, it is expected that the decrease in rice prices will be minimized by the government deciding whether to purchase rice at the beginning of the harvest season in the year of rice oversupply.

On the other hand, the revision of the Grain Management Act may result as contrary to the policy purpose intended by the reorganization of the public-purpose direct payment program. Because the amendment to the Grain Management Act may have the effect of minimizing the decline in rice prices, so the price risk is smaller than other non-rice crops. Because of that reason, rice farmers may still want to continue to cultivate rice. Even though the government aimed to alleviate the structural oversupply of rice by revising policies that were favorable to rice through the reorganization of the direct payment system.

Therefore, in order to avoid such side effects, it is necessary to share the responsibility with producers after the government purchases rice due to oversupply or price drop, which is stipulated in the amended Grain Management Act. Rice farmers also need to understand the purpose of this system and make efforts on their own to resolve the structural oversupply of rice.

REFERENCES

B. I. Ahn, Analysis of the Influences of Direct Payment Policy on the Rice Acreage, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy, 42(3), 2015, 467-486

J. K. Park, N. W. Oh, C. H. Ryu, J. I. Kim, J. Y. Park, Analysis of the operation status and development plan of the agricultural direct payment program, Korea Rural Economics Institute, 2016.

Grain Management Act, Act No. 17761, January 29, 2020

MAFRA (Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs)

[1]The direct payment for small farmers denotes that 1.2 million won (Assuming that one US dollar is 1,000 won, it is equivalent to about 1,200 US dollars.) is paid to farmers who meet the requirements among farms with 0.5 ha or less. However, even if the farm is less than 0.5 ha, if the payment requirements (There are 8 mandatory conditions including area conditions.) are not met, direct payment in proportion to the area is paid.

[2] The rice harvest season is from October to December. The normal year means the average value excluding the year with the highest number and the year with the lowest number among the past five years.

[3] Seasonal amplitude levels mean the price gap difference between harvest and short season. The rice harvest season is from October to December and the short season is from July to September.

[4] October 15, the beginning of the rice harvest season, was set as the deadline. However, if it is difficult to predict the production volume for the year due to sudden changes in weather conditions, the deadline may be extended.

[5] Because the price of rice is announced every 10 days, it corresponds to one month.