ABSTRACT

Knowing the changes in the food industry caused by COVID-19 can help plan mid- to long-term measures in the future. In this regard, this paper examined the changes in the food market in Korea due to COVID-19 in detail and attempted to derive policy implications from them. Due to the spread of COVID-19, consumers avoided to eat out but preferred to eat at home. And the tendency to purchase food via online instead of offline has increased. In addition, the number of households with poor access to food has increased due to the economic instability and the disturbance in food supply chain. In order to respond to such rapid changes in the market, not only industries but also the governments are required to respond. As specific countermeasures, the government needs to establish relevant regulations and policies for the online food industry, prepare measures to ensure food security for the vulnerable, and provide support for maintaining the foundation of the food service industry and its front and rear industries.

Keywords: Food consumption, COVID-19, Consumer behavior

INTRODUCTION

Since January 20, 2020, after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Korea, there has been a significant change in the lifestyles of Koreans. People not only always have worn a mask in their daily lives, but also refrained from engaging in outdoor or face-to-face activities. The change in lifestyle also had a huge impact on the economy, particularly in the restaurant business, where sales were damaged severely.

To overcome this economic crisis, the Korean government has been implementing various assistance policies. In August 2020, the government promoted the ‘Restaurant Consumption Revitalization’ campaign to galvanize the food service industry and offered emergency relief funds to all or partial households in Korea expecting a positive impact on the food service industry. The local government also has been operating various projects such as issuing local currency and designating a ‘germ-free restaurant’. However, some criticizes these government measures as rather short-sighted measures that cannot cope with the mid- to long-term changes in the food industry (Jang, 2021) (Ju, 2020).

Knowing the changes in the food industry caused by COVID-19 can help plan mid- to long-term measures in the future. This paper examined the changes in the food market in Korea due to COVID-19 in detail and attempted to derive policy implications from them. As the global spread of COVID-19 is causing major changes in food markets in many countries around the world, I hope that this data can be used as a reference for researchers who want to look into this in the future as a case in Korea.

STATUS OF FOOD INDUSTRY IN KOREA

Food and beverage manufacturing industry

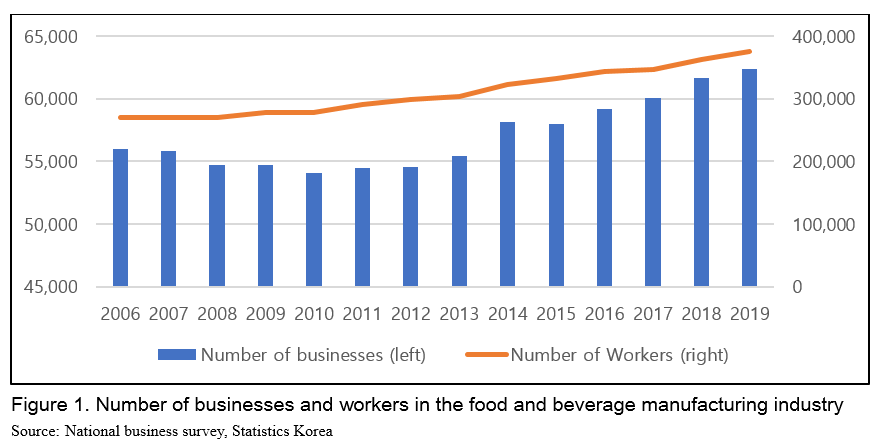

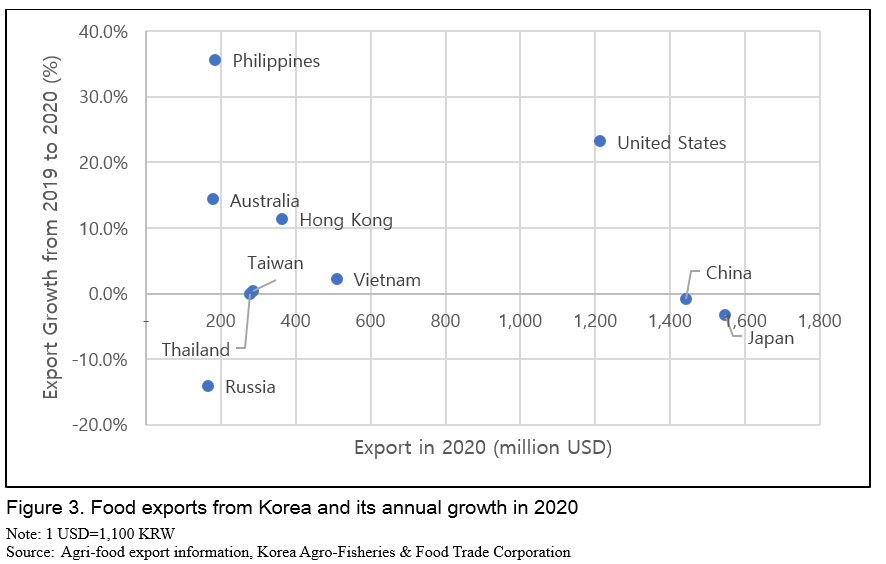

Korea's food and beverage manufacturing industry has continued to grow. In 2019, the number of food and beverage manufacturing businesses in Korea was about 62,000 and the number of employees was about 375,000, showing an upward trend since 2010 (Figure 1). Sales in 2019 increased about 3.5% compared to the previous year amounting to US$115.0 billion, in contrast to a 1.2% decrease in overall manufacturing sales in the same period. Meanwhile, the proportion of food and beverage manufacturing sales in total manufacturing sales increased by 0.3% from 6.4% in 2016 to 6.7% in 2019, and the share of the number of food manufacturing workers in the total manufacturing industry increased by 0.7% from 8.4% in 2016 to 9.1% in 2019 (Table 1).

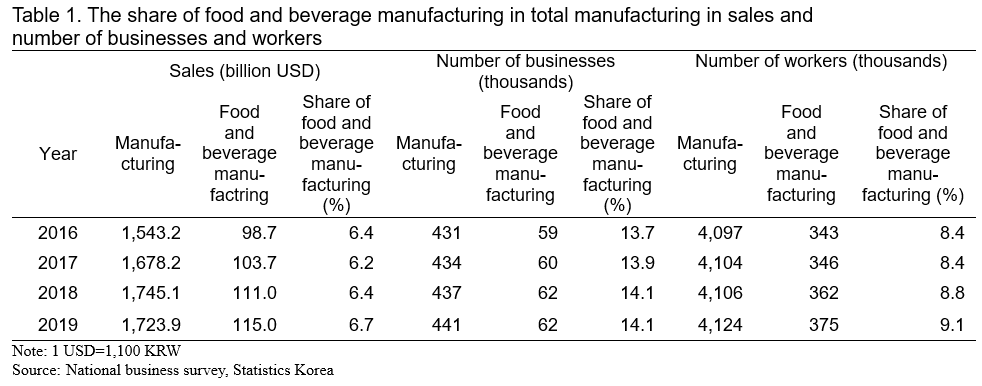

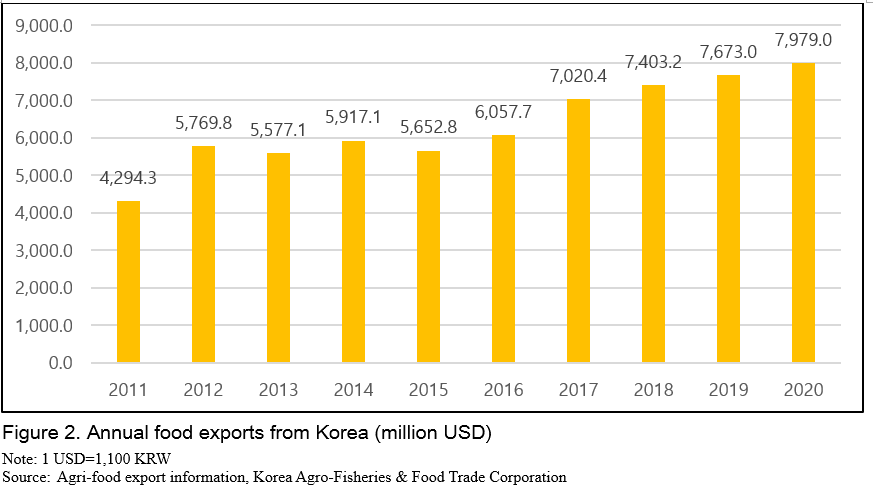

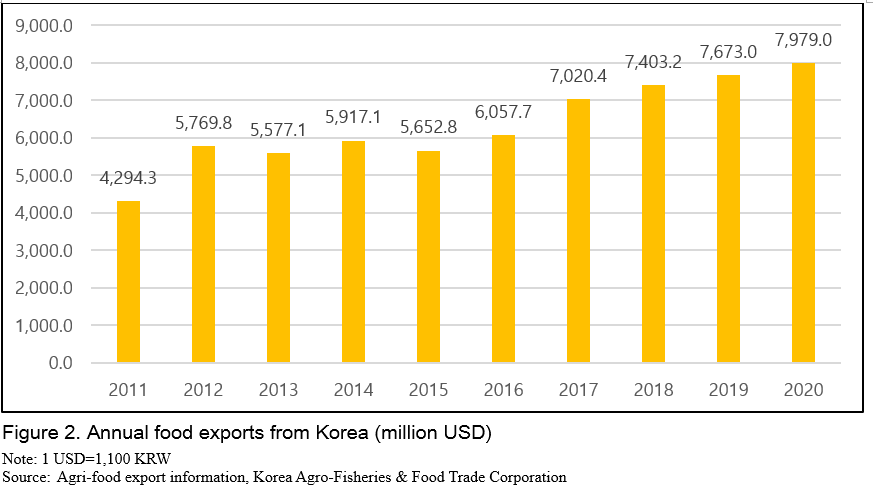

Korea's overall food exports increased significantly in 2020. The exports increased by about 86% from US$4,294.3 million in 2011 to US$7,979.0 million in 2020, attributed to the U.S.-China trade dispute and the Korean Wave represented by K-pop and movies (Figure 2). By country, the Philippines, the United States and Australia are the countries which showed the highest growth in export in 2020 among the top-ten countries to which Korea exports its food in the largest amount (Figure 3).

Food service industry

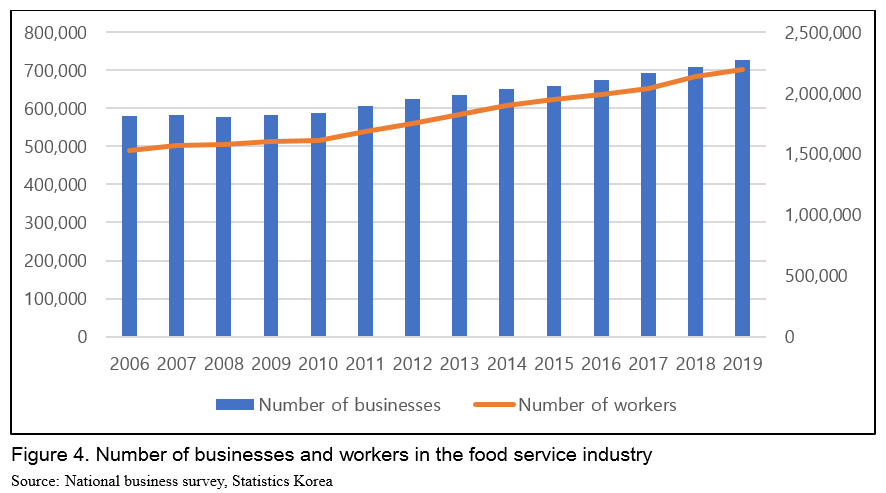

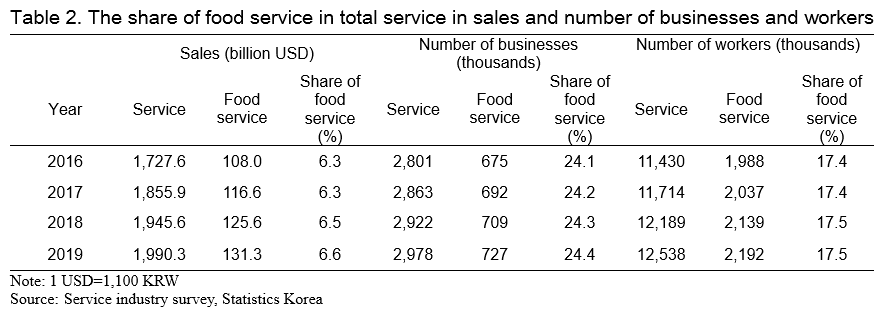

In 2019, the number of food service businesses and the number of its employees increased by 2.6% and 2.5%, respectively, compared to the previous year, showing an overall trend of increase in the food and beverage manufacturing industry (Figure 4). Sales were approximately $119,363 million: an increased amount of about 4.5% compared to the previous year, which is about twice the growth rate of total service sales. As a result of the high sales growth rate, the share of the sales of food service industry in the sales in whole service industry was 6.3% in 2016, and 6.6% in 2019, showing a continuous increase (Table 2).

The Korean food industry has grown outwardly, with sales and the overall number of employees on the rise, and exports in the food manufacturing industry has also been significantly increasing. However, the situation facing the Korean food industry in 2020 does not seem easy; the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea is expected to drive the industry to change how it works. In the next chapter, we will look at the changes in the food consumption behavior in Korea due to COVID-19.

CHANGES IN FOOD CONSUMPTION BEHAVIOR DUE TO THE SPREAD OF COVID-19

Deepening preference for eating-at-home

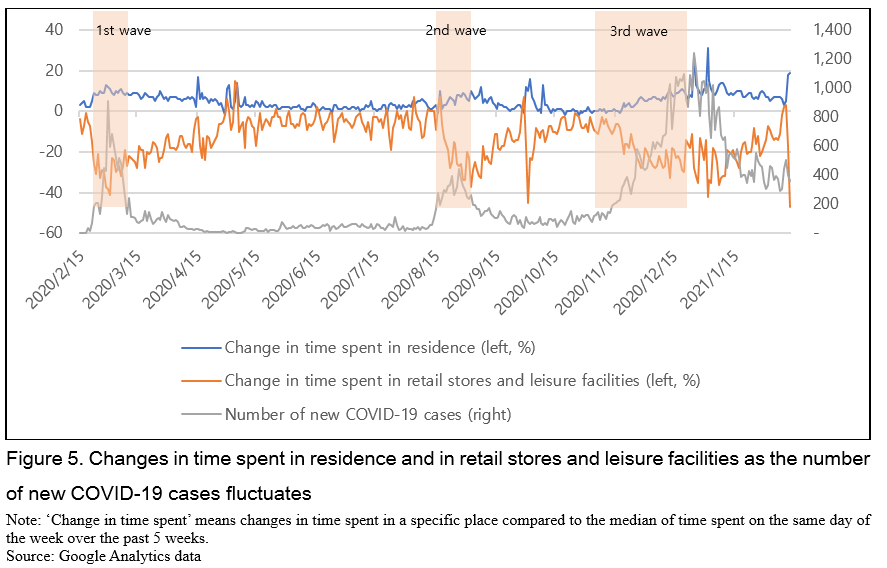

The increase in the share of food expenditure and the decrease in the share of restaurant expenditure can be explained by the change in consumers’ food consumption behavior. First of all, consumers’ outdoor activities were restricted due to concerns about infections. According to data from Google Analytics, the correlation between the change in the time spent in residence and the number of new COVID-19 cases is about 0.58, and the correlation between the change in time spent in retail stores and leisure facilities and the number of the new cases was about -0.58; which means consumers tend to stay at home as the number of new COVID-19 cases increases. The time spent in residential areas increased from February 2020, when the number of new confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Korea surged, while the time spent visiting retail stores and leisure facilities such as restaurants/cafes and shopping centers decreased sharply. The phenomenon was also observed in the second wave period, from late August to early September, and in the third wave, from mid-November to late December (Figure 5).

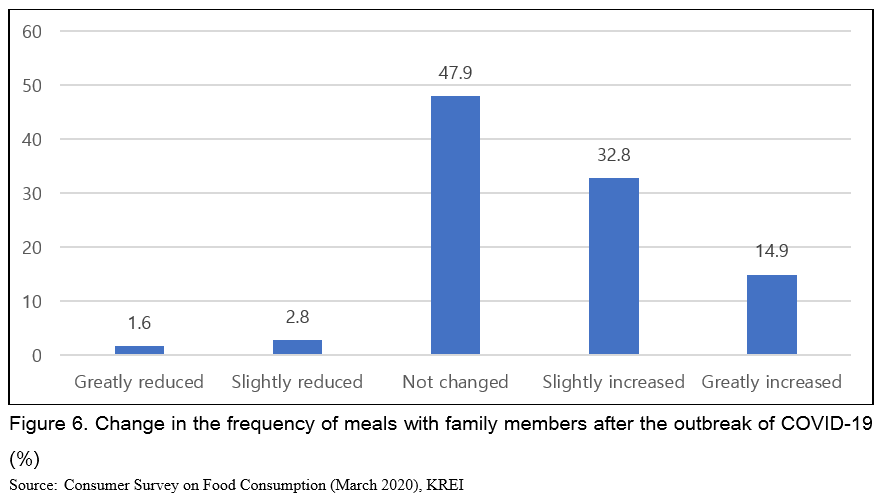

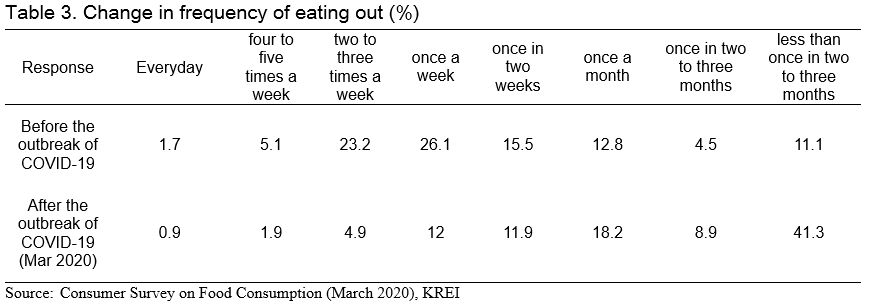

The decrease in outside activities led to a decrease in eating-out consumption. In a survey conducted by Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI) on consumers every year, the proportion of households with an increased number of meals with their family due to COVID-19 was 47.7%, which is an overwhelmingly higher proportion compared to 4.4% of the households that decreased the number of meals with their families (Figure 6). In addition, the proportion of responses of those who eat less than once a month in restaurants increased significantly; from 28.4% before the outbreak of COVID-19 to 68.4% after the outbreak (Table 3).

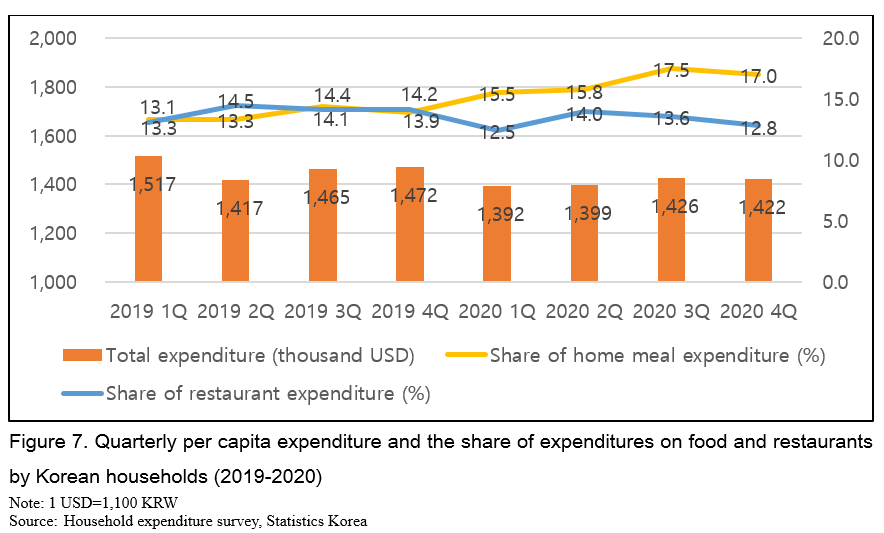

As the time spent in residences increases and the number of meals with family members increases, the proportion of food ingredients for cooking in the total food expenditure increased, while the proportion of expenditure on eating-out decreased significantly. Looking at the monthly food expenditure per capita in 2020, the total expenditure decreased compared to the same period of the previous year in all quarters except in the second quarter. On the other hand, food expenditure showed a slight increase compared to the previous year, so the share of home meal expenditure increased significantly in 2020 compared to the previous year. Share of restaurnat expenditure, however, decreased compared to the previous year; it means that the restaurant expenditure decreased significantly compared to the previous year (Figure 7).

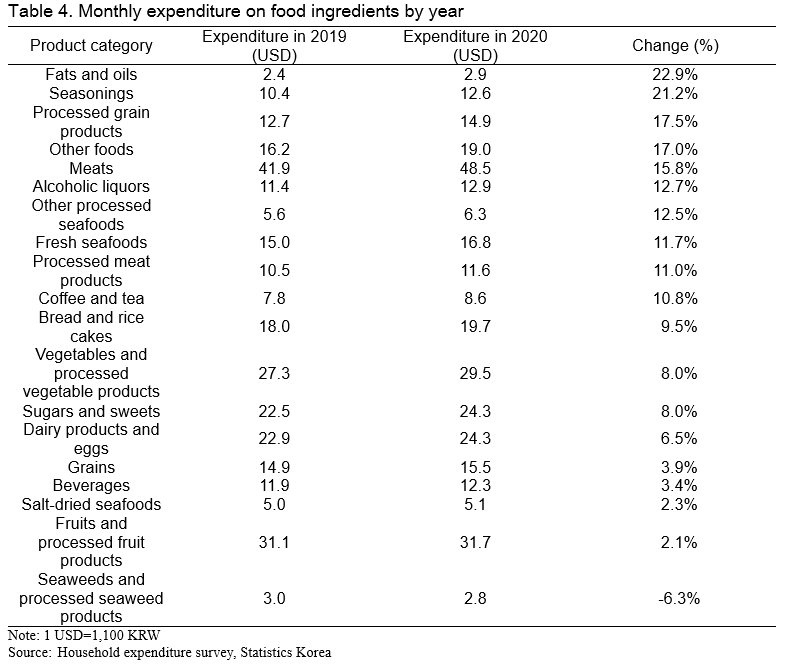

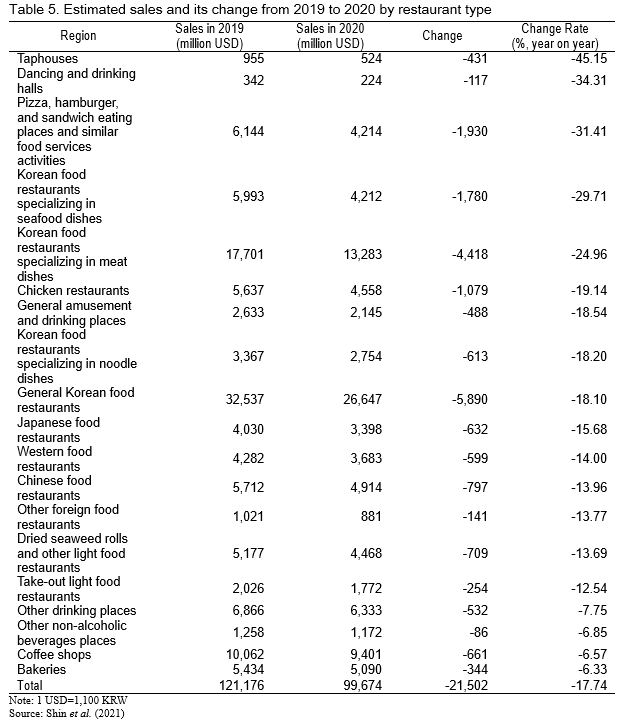

In the case of food ingredients, expenditures for all product groups except seaweed and processed seaweed products increased compared to the previous year. In particular, expenditure on products which are frequently used in cooking, such as oils and seasonings, increased significantly (Table 4). On the other hand, in the case of the food service business, sales are estimated to have decreased by 17.74% in 2020 compared to the previous year. By restaurant type, taphouses are expected to suffer from the largest decline in sales (Table 5) (Shin et al., 2021).

Preference for online-consumption over offline-consumption

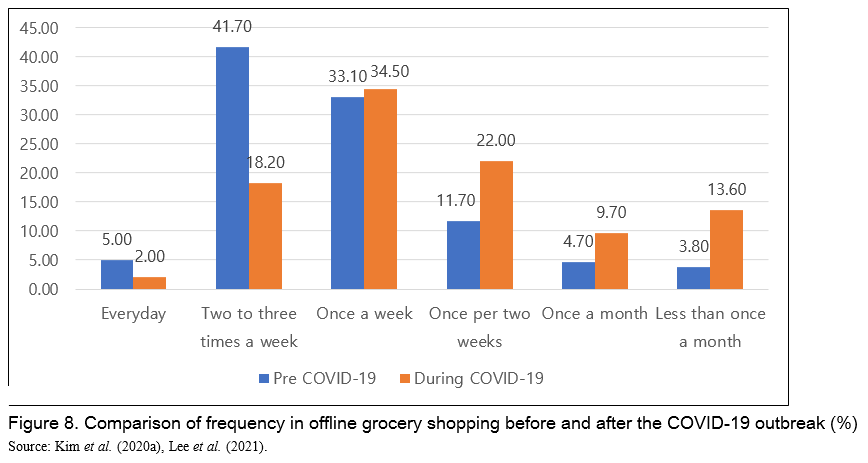

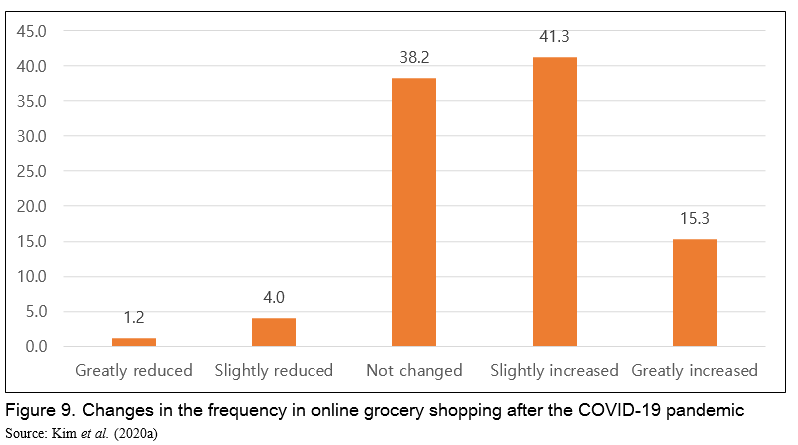

As concerns about infections increased and outside activities were restricted, consumers prefered to consume groceries online rather than offline. According to the results of a survey conducted in March 2020 by KREI, the frequency of purchasing groceries online has increased in both surveys, while the frequency of purchasing groceries offline has decreased (Figure 8, 9) (Kim et al., 2020a)

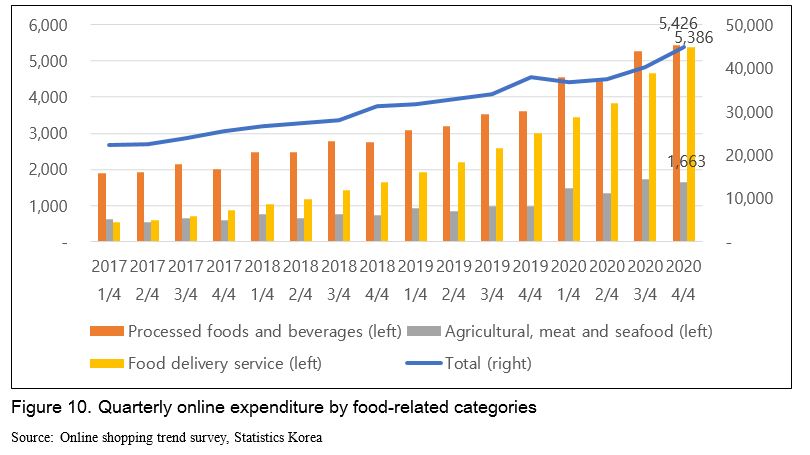

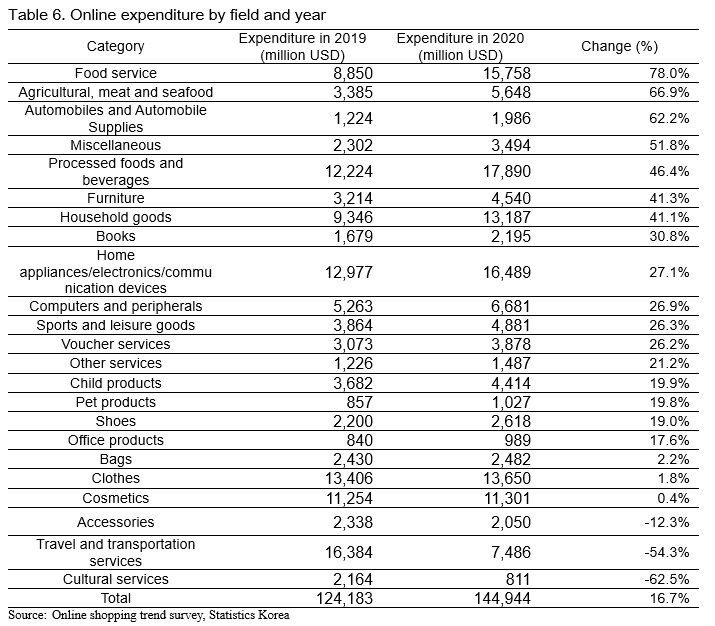

The amount of food purchased online increased sharply in 2020, when the spread of COVID-19 accelerated. In particular, food delivery service and agricultural, meat and seafood categories had significantly higher sales growth rates in the online sector compared to other industries, which proves that the preference for online consumption has increased in the food sector (Figure 10, Table 6).

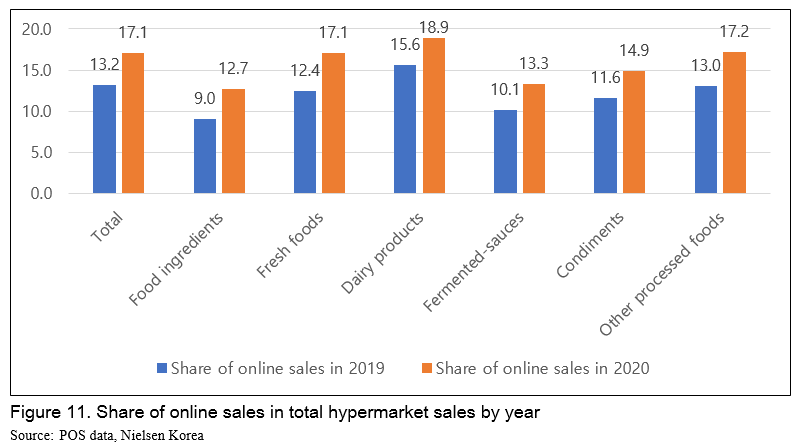

The proportion of online sales in total food sales increased from 13.2% in 2019 to 17.1% in 2020. By food category, fresh-food group showed the highest increase in proportion; from 12.4% in 2019 to 17.1 % in 2020. It is interesting to note that the proportion of online orders for fresh foods, where freshness is particularly important, has increased (Figure 11). If it had not been for the recent development of delivery technology represented by 'cold chain', a different result could have appeared.

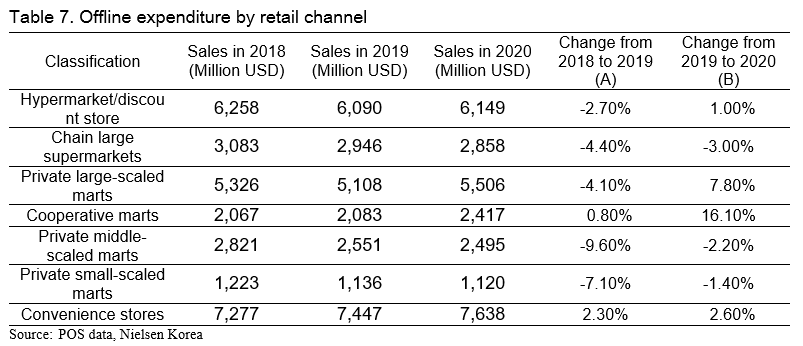

In the case of offline-channels, overall food and beverage sales increased compared to the previous year, excluding some channels. In particular, it is interesting that the sales in private marts located in residential and commercial districts increased sharply; consumers seem to have increased their purchases of groceries at nearby retail stores that have good access to food and provide delivery services. Private large-scaled marts and cooperative marts, which increased their sales significantly this year, have been actively introducing their own delivery services as their sales had decreased due to the expansion of online-delivery platform services in Korea (Table 7).

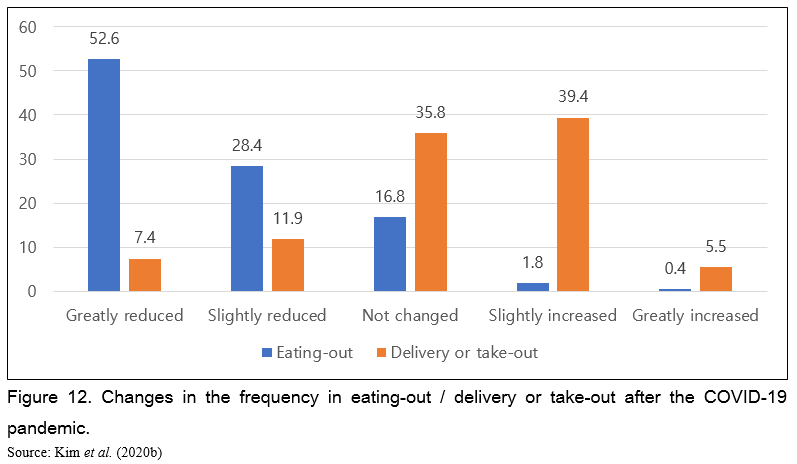

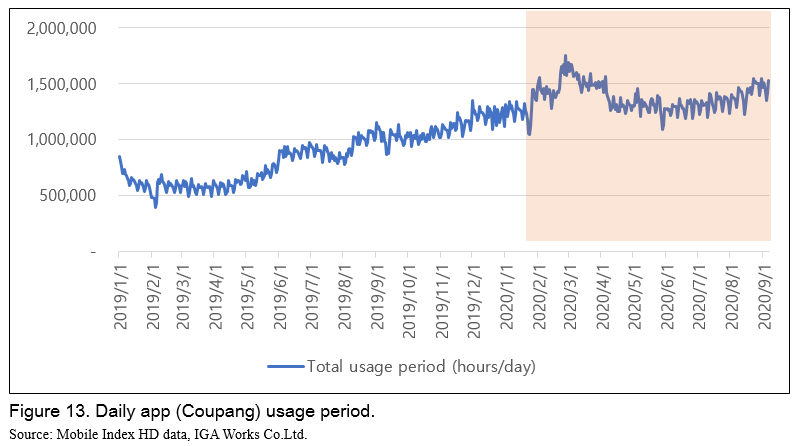

Meanwhile, in the case of the restaurant business, the demand for delivery is expected to increase significantly while eating out is restrained. According to the results of a survey conducted by KREI on consumers, 81.0% of the respondents said that the frequency of eating-out decreased compared to before the spread of COVID-19, whereas 44.9% of respondents said that the frequency of delivery or takeout increased constrasting to the response of the same question on eating-out (Figure 12) (Kim et al., 2020b). In addition, the daily usage time for the delivery app increased significantly from February 2020, after the outbreak of COVID-19 (Figure 13). As consumers prefered food delivery to eating-out, the severity of damage varies depending on the restaurant type. In Table 5 above, the restaurants whose sales are highly dependent on delivery and take-outs, such as Chinese food restaurants, take-out light food restaurants, and bakeries, have suffered relatively little damage.

Polarization in food consumption

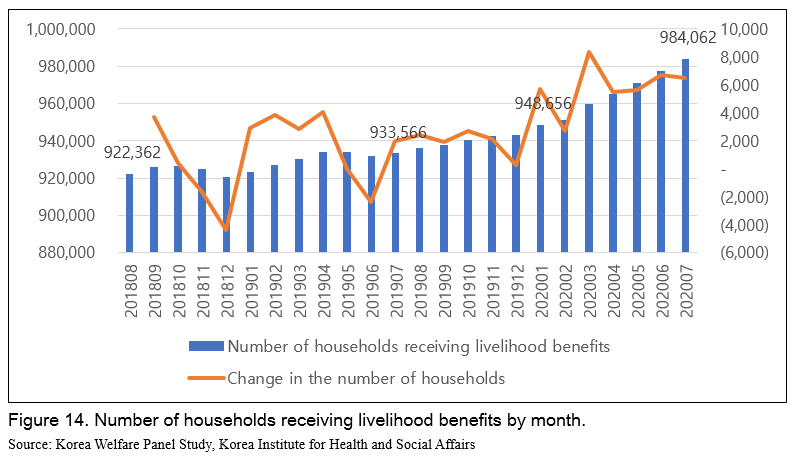

The spread of COVID-19 is expected to deepen the polarization of food consumption. This can be inferred from the increase in the number of vulnerable groups in Korea and the rise in domestic agricultural and food prices. The number of households receiving livelihood benefits has been increasing at a faster rate since the beginning of 2020, when COVID-19 began to spread. From August 2018 to January 2020, before the spread of COVID-19 in Korea, the average number of increases in households receiving livelihood benefit was about 1,500 per month, but after February 2020, when the domestic spread of COVID-19 began, the average number of increases soared to 6,000 per month.

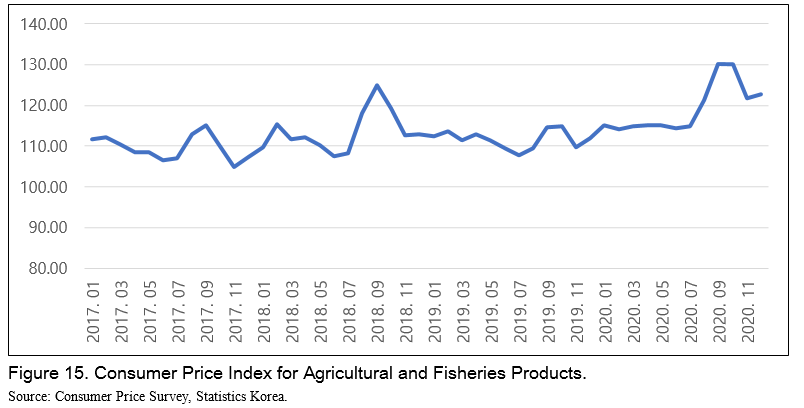

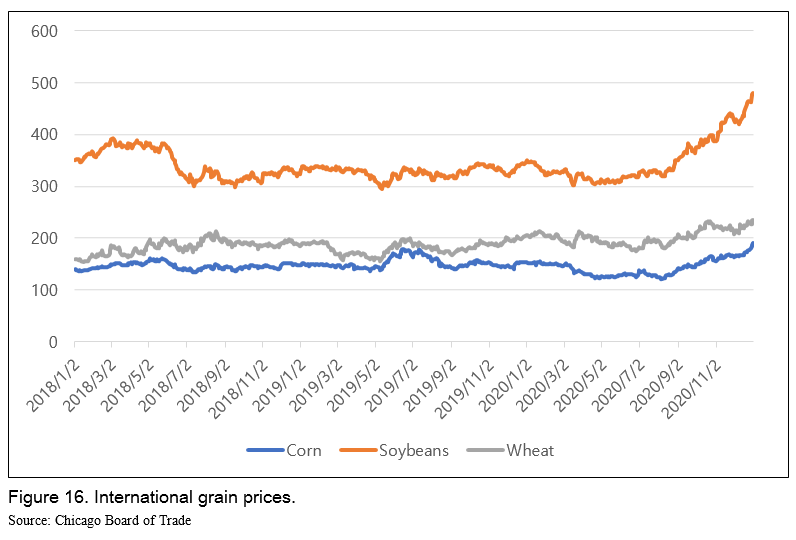

While the number of vulnerable groups has increased, domestic agri-food consumer prices are rising. The consumer price index for agricultural and fishery products has been on the rise since the third quarter of 2020 (Figure 15). Domestic agricultural and food consumer prices are mostly due to abnormal climates in Korea in 2020 such as floods, but the impact of COVID-19 cannot be ignored; as foreign workers who are essential for the production of agri-food in Korea were unable to enter the country due to the recent COVID-19 crisis so farmers in Korea could not acquire enough labor during the havest season; and also, the food supply chain disrupted due to radical changes in demand in the food distribution channel during the crisis, resulting in a huge amount of wastage in perishable foods. In addition, international grain prices, which accounted for a large proportion of food production costs, are also on an upward trend due to a demand-side impact of the crisis and export restrictions by food exporting countries, suggesting that food prices will continue to be high for a while (Figure 16). The rise in consumer prices for food is a burden on households. In particular, for the vulnerable households, where food expenditure accounts for a high proportion of total consumption expenditure, the burden from the rise in food prices is expected to be greater in the midst of a pandemic compared to the other households (Cavallo, 2020).

IMPLICATIONS

So far, we have looked at the current status of the Korean food industry and changes in food consumption behavior due to COVID-19. From this, the following implications can be drawn.

First, policies and systems for the online-food industry need to be established; the amount of food consumption through online has been continuously growing, but its growth rate is accelerating through the pandemic. Accordingly, it is necessary to establish regulations in various fields such as food safety in the online to offline industry and protection of consumers and small businesses in the online field.

Second, it is necessary to supplement policies to ensure food security for the vulnerable households; the recent COVID-19 outbreak not only raised food prices, but also caused economic instability, increasing the number of vulnerable households. In cases where food security is not properly ensured, there is a risk of social unrest (The World Bank, 2019). The government will be able to improve food security and control social unrest factors by establishing an agri-food support program for these groups (Kim and Lee, 2020).

Finally, support is needed to maintain the foundation of the food service industry; the industry accounts for 24.4% of the total number of businesses and 17.5% of the total number of employees in the service industry in Korea. Considering that the sales of the industry decreased by 17.7% compared to the previous year due to COVID-19, if support for workers in these industries is not provided properly, it may lead to mass unemployment, which further increases the number of the vulnerable. In addition, it is expected that damage to related industries has also occurred. In particular, as the damage to farmers and food manufacturers who supplied food to restaurants is expected to be great, the government will need to prevent mass unemployment through support for these industries.

CONCLUSION

This study introduces the current status of the Korean food industry, changes in food consumption behavior due to COVID-19, and its impact on the food industry. Korea's food manufacturing and catering industries account for a large proportion of the total industry, and have a large contribution to job creation.

However, the spread of COVID-19 in 2020 has brought great challenges to the food industry. Social concerns about infections have intensified the avoidance of eating out and preference for home-cooked meals, and the tendency to purchase food via online instead of offline has increased. In addition, the number of households with poor access to food has increased due to the economic instability and the disturbance in the food supply chain.

In order to respond to such rapid changes in the market, not only are industries but also governments are required to respond. As specific countermeasures, the government needs to establish relevant regulations and policies for the online food industry, prepare measures to ensure food security for the vulnerable, and provide support to maintain the foundation of the food service industry and its front and rear industries.

REFERENCES

Cavallo, A. (2020). Inflation with covid consumption baskets (No. w27352). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jang. W. C. (Mar. 24, 2021). “Hygiene and safety should be prioritized over financial support for the restaurant business”. Shin-A Ilbo.

Ju. J. O. (Nov. 1, 2020). “Will the number of restaurant customers increase if the dining out coupons are released?”. Gyeongnam Newspaper.

Kim, S. H., Lee, K. I., Koo, J. C., Hong, Y. N., Moon, D. H., Heo, S. Y., Ji, J. H., Shin, S.Y., Yu, K. H., Kim. M. S., Lee, W. J., An, B. I., Kim. H. J., Seo. D. H., Kim. S. M. (2020a). 2020 Agricultural Food Consumption Information Analysis Report. Korea Rural Economic Institute

Kim, S. H., & Lee, W. J. (2020b). Basic research on establishment of agri-food support program for the nutritionally vulnerable. Korea Rural Economic Institute

Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. (2020). Korea Welfare Panel Study [Data set]. https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/data/data/list.do

Lee, K. I., Kim, S. H., Heo, S. Y., Shin, S. Y., Park, I. H. (2021). Consumer Behavior Survey for Foods [Data set]. Korea Rural Economic Institute. https://www.krei.re.kr/foodSurvey/selectBbsNttList.do?bbsNo=451&key=1774

The World Bank. Food riots: From definition to operationalization. <webpage: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/food-price-crisis-observatory#4>

Post-COVID-19 Era, Changes and Outlook in Korea’s Agrifood Industry

ABSTRACT

Knowing the changes in the food industry caused by COVID-19 can help plan mid- to long-term measures in the future. In this regard, this paper examined the changes in the food market in Korea due to COVID-19 in detail and attempted to derive policy implications from them. Due to the spread of COVID-19, consumers avoided to eat out but preferred to eat at home. And the tendency to purchase food via online instead of offline has increased. In addition, the number of households with poor access to food has increased due to the economic instability and the disturbance in food supply chain. In order to respond to such rapid changes in the market, not only industries but also the governments are required to respond. As specific countermeasures, the government needs to establish relevant regulations and policies for the online food industry, prepare measures to ensure food security for the vulnerable, and provide support for maintaining the foundation of the food service industry and its front and rear industries.

Keywords: Food consumption, COVID-19, Consumer behavior

INTRODUCTION

Since January 20, 2020, after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Korea, there has been a significant change in the lifestyles of Koreans. People not only always have worn a mask in their daily lives, but also refrained from engaging in outdoor or face-to-face activities. The change in lifestyle also had a huge impact on the economy, particularly in the restaurant business, where sales were damaged severely.

To overcome this economic crisis, the Korean government has been implementing various assistance policies. In August 2020, the government promoted the ‘Restaurant Consumption Revitalization’ campaign to galvanize the food service industry and offered emergency relief funds to all or partial households in Korea expecting a positive impact on the food service industry. The local government also has been operating various projects such as issuing local currency and designating a ‘germ-free restaurant’. However, some criticizes these government measures as rather short-sighted measures that cannot cope with the mid- to long-term changes in the food industry (Jang, 2021) (Ju, 2020).

Knowing the changes in the food industry caused by COVID-19 can help plan mid- to long-term measures in the future. This paper examined the changes in the food market in Korea due to COVID-19 in detail and attempted to derive policy implications from them. As the global spread of COVID-19 is causing major changes in food markets in many countries around the world, I hope that this data can be used as a reference for researchers who want to look into this in the future as a case in Korea.

STATUS OF FOOD INDUSTRY IN KOREA

Food and beverage manufacturing industry

Korea's food and beverage manufacturing industry has continued to grow. In 2019, the number of food and beverage manufacturing businesses in Korea was about 62,000 and the number of employees was about 375,000, showing an upward trend since 2010 (Figure 1). Sales in 2019 increased about 3.5% compared to the previous year amounting to US$115.0 billion, in contrast to a 1.2% decrease in overall manufacturing sales in the same period. Meanwhile, the proportion of food and beverage manufacturing sales in total manufacturing sales increased by 0.3% from 6.4% in 2016 to 6.7% in 2019, and the share of the number of food manufacturing workers in the total manufacturing industry increased by 0.7% from 8.4% in 2016 to 9.1% in 2019 (Table 1).

Korea's overall food exports increased significantly in 2020. The exports increased by about 86% from US$4,294.3 million in 2011 to US$7,979.0 million in 2020, attributed to the U.S.-China trade dispute and the Korean Wave represented by K-pop and movies (Figure 2). By country, the Philippines, the United States and Australia are the countries which showed the highest growth in export in 2020 among the top-ten countries to which Korea exports its food in the largest amount (Figure 3).

Food service industry

In 2019, the number of food service businesses and the number of its employees increased by 2.6% and 2.5%, respectively, compared to the previous year, showing an overall trend of increase in the food and beverage manufacturing industry (Figure 4). Sales were approximately $119,363 million: an increased amount of about 4.5% compared to the previous year, which is about twice the growth rate of total service sales. As a result of the high sales growth rate, the share of the sales of food service industry in the sales in whole service industry was 6.3% in 2016, and 6.6% in 2019, showing a continuous increase (Table 2).

The Korean food industry has grown outwardly, with sales and the overall number of employees on the rise, and exports in the food manufacturing industry has also been significantly increasing. However, the situation facing the Korean food industry in 2020 does not seem easy; the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea is expected to drive the industry to change how it works. In the next chapter, we will look at the changes in the food consumption behavior in Korea due to COVID-19.

CHANGES IN FOOD CONSUMPTION BEHAVIOR DUE TO THE SPREAD OF COVID-19

Deepening preference for eating-at-home

The increase in the share of food expenditure and the decrease in the share of restaurant expenditure can be explained by the change in consumers’ food consumption behavior. First of all, consumers’ outdoor activities were restricted due to concerns about infections. According to data from Google Analytics, the correlation between the change in the time spent in residence and the number of new COVID-19 cases is about 0.58, and the correlation between the change in time spent in retail stores and leisure facilities and the number of the new cases was about -0.58; which means consumers tend to stay at home as the number of new COVID-19 cases increases. The time spent in residential areas increased from February 2020, when the number of new confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Korea surged, while the time spent visiting retail stores and leisure facilities such as restaurants/cafes and shopping centers decreased sharply. The phenomenon was also observed in the second wave period, from late August to early September, and in the third wave, from mid-November to late December (Figure 5).

The decrease in outside activities led to a decrease in eating-out consumption. In a survey conducted by Korea Rural Economic Institute (KREI) on consumers every year, the proportion of households with an increased number of meals with their family due to COVID-19 was 47.7%, which is an overwhelmingly higher proportion compared to 4.4% of the households that decreased the number of meals with their families (Figure 6). In addition, the proportion of responses of those who eat less than once a month in restaurants increased significantly; from 28.4% before the outbreak of COVID-19 to 68.4% after the outbreak (Table 3).

As the time spent in residences increases and the number of meals with family members increases, the proportion of food ingredients for cooking in the total food expenditure increased, while the proportion of expenditure on eating-out decreased significantly. Looking at the monthly food expenditure per capita in 2020, the total expenditure decreased compared to the same period of the previous year in all quarters except in the second quarter. On the other hand, food expenditure showed a slight increase compared to the previous year, so the share of home meal expenditure increased significantly in 2020 compared to the previous year. Share of restaurnat expenditure, however, decreased compared to the previous year; it means that the restaurant expenditure decreased significantly compared to the previous year (Figure 7).

In the case of food ingredients, expenditures for all product groups except seaweed and processed seaweed products increased compared to the previous year. In particular, expenditure on products which are frequently used in cooking, such as oils and seasonings, increased significantly (Table 4). On the other hand, in the case of the food service business, sales are estimated to have decreased by 17.74% in 2020 compared to the previous year. By restaurant type, taphouses are expected to suffer from the largest decline in sales (Table 5) (Shin et al., 2021).

Preference for online-consumption over offline-consumption

As concerns about infections increased and outside activities were restricted, consumers prefered to consume groceries online rather than offline. According to the results of a survey conducted in March 2020 by KREI, the frequency of purchasing groceries online has increased in both surveys, while the frequency of purchasing groceries offline has decreased (Figure 8, 9) (Kim et al., 2020a)

The amount of food purchased online increased sharply in 2020, when the spread of COVID-19 accelerated. In particular, food delivery service and agricultural, meat and seafood categories had significantly higher sales growth rates in the online sector compared to other industries, which proves that the preference for online consumption has increased in the food sector (Figure 10, Table 6).

The proportion of online sales in total food sales increased from 13.2% in 2019 to 17.1% in 2020. By food category, fresh-food group showed the highest increase in proportion; from 12.4% in 2019 to 17.1 % in 2020. It is interesting to note that the proportion of online orders for fresh foods, where freshness is particularly important, has increased (Figure 11). If it had not been for the recent development of delivery technology represented by 'cold chain', a different result could have appeared.

In the case of offline-channels, overall food and beverage sales increased compared to the previous year, excluding some channels. In particular, it is interesting that the sales in private marts located in residential and commercial districts increased sharply; consumers seem to have increased their purchases of groceries at nearby retail stores that have good access to food and provide delivery services. Private large-scaled marts and cooperative marts, which increased their sales significantly this year, have been actively introducing their own delivery services as their sales had decreased due to the expansion of online-delivery platform services in Korea (Table 7).

Meanwhile, in the case of the restaurant business, the demand for delivery is expected to increase significantly while eating out is restrained. According to the results of a survey conducted by KREI on consumers, 81.0% of the respondents said that the frequency of eating-out decreased compared to before the spread of COVID-19, whereas 44.9% of respondents said that the frequency of delivery or takeout increased constrasting to the response of the same question on eating-out (Figure 12) (Kim et al., 2020b). In addition, the daily usage time for the delivery app increased significantly from February 2020, after the outbreak of COVID-19 (Figure 13). As consumers prefered food delivery to eating-out, the severity of damage varies depending on the restaurant type. In Table 5 above, the restaurants whose sales are highly dependent on delivery and take-outs, such as Chinese food restaurants, take-out light food restaurants, and bakeries, have suffered relatively little damage.

Polarization in food consumption

The spread of COVID-19 is expected to deepen the polarization of food consumption. This can be inferred from the increase in the number of vulnerable groups in Korea and the rise in domestic agricultural and food prices. The number of households receiving livelihood benefits has been increasing at a faster rate since the beginning of 2020, when COVID-19 began to spread. From August 2018 to January 2020, before the spread of COVID-19 in Korea, the average number of increases in households receiving livelihood benefit was about 1,500 per month, but after February 2020, when the domestic spread of COVID-19 began, the average number of increases soared to 6,000 per month.

While the number of vulnerable groups has increased, domestic agri-food consumer prices are rising. The consumer price index for agricultural and fishery products has been on the rise since the third quarter of 2020 (Figure 15). Domestic agricultural and food consumer prices are mostly due to abnormal climates in Korea in 2020 such as floods, but the impact of COVID-19 cannot be ignored; as foreign workers who are essential for the production of agri-food in Korea were unable to enter the country due to the recent COVID-19 crisis so farmers in Korea could not acquire enough labor during the havest season; and also, the food supply chain disrupted due to radical changes in demand in the food distribution channel during the crisis, resulting in a huge amount of wastage in perishable foods. In addition, international grain prices, which accounted for a large proportion of food production costs, are also on an upward trend due to a demand-side impact of the crisis and export restrictions by food exporting countries, suggesting that food prices will continue to be high for a while (Figure 16). The rise in consumer prices for food is a burden on households. In particular, for the vulnerable households, where food expenditure accounts for a high proportion of total consumption expenditure, the burden from the rise in food prices is expected to be greater in the midst of a pandemic compared to the other households (Cavallo, 2020).

IMPLICATIONS

So far, we have looked at the current status of the Korean food industry and changes in food consumption behavior due to COVID-19. From this, the following implications can be drawn.

First, policies and systems for the online-food industry need to be established; the amount of food consumption through online has been continuously growing, but its growth rate is accelerating through the pandemic. Accordingly, it is necessary to establish regulations in various fields such as food safety in the online to offline industry and protection of consumers and small businesses in the online field.

Second, it is necessary to supplement policies to ensure food security for the vulnerable households; the recent COVID-19 outbreak not only raised food prices, but also caused economic instability, increasing the number of vulnerable households. In cases where food security is not properly ensured, there is a risk of social unrest (The World Bank, 2019). The government will be able to improve food security and control social unrest factors by establishing an agri-food support program for these groups (Kim and Lee, 2020).

Finally, support is needed to maintain the foundation of the food service industry; the industry accounts for 24.4% of the total number of businesses and 17.5% of the total number of employees in the service industry in Korea. Considering that the sales of the industry decreased by 17.7% compared to the previous year due to COVID-19, if support for workers in these industries is not provided properly, it may lead to mass unemployment, which further increases the number of the vulnerable. In addition, it is expected that damage to related industries has also occurred. In particular, as the damage to farmers and food manufacturers who supplied food to restaurants is expected to be great, the government will need to prevent mass unemployment through support for these industries.

CONCLUSION

This study introduces the current status of the Korean food industry, changes in food consumption behavior due to COVID-19, and its impact on the food industry. Korea's food manufacturing and catering industries account for a large proportion of the total industry, and have a large contribution to job creation.

However, the spread of COVID-19 in 2020 has brought great challenges to the food industry. Social concerns about infections have intensified the avoidance of eating out and preference for home-cooked meals, and the tendency to purchase food via online instead of offline has increased. In addition, the number of households with poor access to food has increased due to the economic instability and the disturbance in the food supply chain.

In order to respond to such rapid changes in the market, not only are industries but also governments are required to respond. As specific countermeasures, the government needs to establish relevant regulations and policies for the online food industry, prepare measures to ensure food security for the vulnerable, and provide support to maintain the foundation of the food service industry and its front and rear industries.

REFERENCES

Cavallo, A. (2020). Inflation with covid consumption baskets (No. w27352). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jang. W. C. (Mar. 24, 2021). “Hygiene and safety should be prioritized over financial support for the restaurant business”. Shin-A Ilbo.

Ju. J. O. (Nov. 1, 2020). “Will the number of restaurant customers increase if the dining out coupons are released?”. Gyeongnam Newspaper.

Kim, S. H., Lee, K. I., Koo, J. C., Hong, Y. N., Moon, D. H., Heo, S. Y., Ji, J. H., Shin, S.Y., Yu, K. H., Kim. M. S., Lee, W. J., An, B. I., Kim. H. J., Seo. D. H., Kim. S. M. (2020a). 2020 Agricultural Food Consumption Information Analysis Report. Korea Rural Economic Institute

Kim, S. H., & Lee, W. J. (2020b). Basic research on establishment of agri-food support program for the nutritionally vulnerable. Korea Rural Economic Institute

Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. (2020). Korea Welfare Panel Study [Data set]. https://www.koweps.re.kr:442/data/data/list.do

Lee, K. I., Kim, S. H., Heo, S. Y., Shin, S. Y., Park, I. H. (2021). Consumer Behavior Survey for Foods [Data set]. Korea Rural Economic Institute. https://www.krei.re.kr/foodSurvey/selectBbsNttList.do?bbsNo=451&key=1774

The World Bank. Food riots: From definition to operationalization. <webpage: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/food-price-crisis-observatory#4>