ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 novel coronavirus spread around the world since December 2019. The first official case in Myanmar was reported on March 23rd 2020 where the first set of containment measures was introduced. In Myanmar, COVID-19 infection rate was low at the 1st wave but recently at the 2nd wave, confirmed cases increased in the months of August, September and October 2020. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing an unprecedented challenge to the Government of Myanmar and populations across country. The spread of the COVID-19 is placing huge pressure on health systems but it is also having social and economic impacts on across all sectors including food and agriculture. The Government of Myanmar released the COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) on April 28, 2020 to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic which includes monetary reform, increased government spending and strengthening of the health sector. It has 7 goals, 10 strategies, and 36 action plans and 78 actions. Among the action plans in CERP, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) had to take responsibilities of implementing the support for farmers, seed producers, agri-processors and owners of agri-businesses. In the crop production sector, the likely disruption of input supplies for the planting season may lead to seasonal and long-term food shortages and income losses, compromising purchasing power and access to healthy diets. Wage decreases and livelihood loss could deepen poverty, push households to resort to negative coping strategies, and compromise their resilience to any further shocks such as floods and droughts. Given the importance of nutrition security, a sustainable food systems approach is also advocated especially with a focus on climate resilient sustainable agriculture practices that ensure food security of the small farmers. Measures like crop diversification and efficient nutrition management are some of the interventions in this respect. There is a need for building resilience of supply chains by increasing food production capacity, strengthening food reserves in the country, as well as improving national food logistics systems. There is also a need to emphasize sound policies and programmes that focus on resilient food systems and nutrition-sensitive food diversification. Promoting sustainable and resilient food systems approaches will deliver food security and nutrition while building resilience to shocks and maintaining the economic, social and environmental basis to generate food security and nutrition which is important for rural and urban poor in the country.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, food security, nutrition, poverty, livelihood, agriculture

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 novel coronavirus spread around the world since December 2019. The first official case in Myanmar was reported on March 23rd, 2020 where the first set of containment measures was introduced. In Myanmar, COVID-19 infection rate was low at the 1st wave but recently at the 2nd wave, confirmed cases increased in the months of August, September and October 2020. The number of affected persons of COVID-19 is growing rapidly. As of November 3rd,2020, there were 54,607 confirmed cases, 1,282 deaths and 37,954 persons who recovered. To control and reduce the rate of spreading the virus, Myanmar has taken necessary actions such as physical distancing, lockdowns, travel and trade restrictions. Such kinds of actions had seriously reduced and mitigated the negative impacts on activities across the food system. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic had caused and is still causing severe challenges to the well-being, livelihood and safety of peoples and its adverse impact on the socio-economic development of Myanmar. This will have an impact on the economic recovery. Due to the pandemic, Myanmar’s GDP growth forecast for FY2019/20 has been revised downward from 6.4% to just 0.5% as all sectors experience adverse effects of varying intensity (World Bank, June 2020). The impacts of this pandemic are transmitted to all the sectors, especially the tourism-related services and transportation activities which are highly exposed, while the agriculture and information and communications technology (ICT) sectors have proven relatively resilient.

Government policy measures and actions for COVID-19

The government of Myanmar was highly aware of and responsive to the threat of COVID-19, both in terms of its health dimensions and its potential economic impacts. Due to its limited health services, the government relied on stringent public health restrictions, and the closure of all international borders, with the exception of returning international migrants. After a period of implementing only selective lockdowns in townships where COVID-19 cases emerged, a full lockdown was re-imposed on all townships in the Yangon metropolitan area in response to a surge in positive cases in the city. The lockdown was extended to Ayeyarwady, Bago and Mandalay regions and to Mon state on September 27, 2020. The Government of Myanmar released the COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) on April 28, 2020 to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic which includes monetary reforms, increased government spending and strengthening of the health sector. It has 7 goals, 10 strategies, and 36 action plans and 78 actions. The action plans are being implemented by the relevant ministries in accordance with the nature of activities.

Among the action plans in CERP, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) had to take responsibilities for implementing the support for farmers, seed producers, agri-processors and owners of agri-businesses. There were four sub action plans under action plan 2.1.7 (MOAL concern), such as (a) Support COVID-19 communication campaigns; (b) Cash for lending support to smallholder farmers who have lost sales revenue or remittance income to support purchases in time for monsoon planting; (c) Complement support with activities on productivity enhancement and market connectivity; and (d) Establishment of rural cash for work programme and other related activities following the lifting of movement restriction. For the implementation of those action plans, the government has approved 92.61 billion MMK (US$71.87 million fund for Agriculture Sector for immediate response plan against COVID- 19.

Activities identified included loan support to farmers, market connectivity and improvements in productivity through extension services. All these are expected to build resilience in the agriculture sector thereby ensuring food security. Meanwhile, in the production front, there was limited impact in the early months, agriculture trade and exports have been affected significantly due to the lockdown measures, closure of borders and movement of goods. Border trade in agriculture commodities appears to have been affected significantly over the past four months, although there is a turnaround in the most recent period.

Status of agriculture, food security and nutrition during COVID- 19 pandemic

Agriculture covers farming, fishing, and forestry which contributed to 25.6% of GDP annually in 2019. The development of agriculture sector means the development of the national economy since the agriculture sector is providing food, raw materials for agro based industries, non-food industries and so on. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing an unprecedented challenge to the Government of Myanmar and populations across the country. The spread of the COVID-19 is placing huge pressure on health systems but it is also having social and economic impacts on all sectors of society including food and agriculture.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Myanmar’s food and nutrition security are complex in nature because the actors that govern food production and food supply chains include farmers, owners of agricultural inputs, processing plants, logistics services, traders and retailers, all of whom are under threat. Moreover, agricultural services such as storage, transportation and logistics, finance, marketing, research, and extension services have also been affected by the lockdown measures.

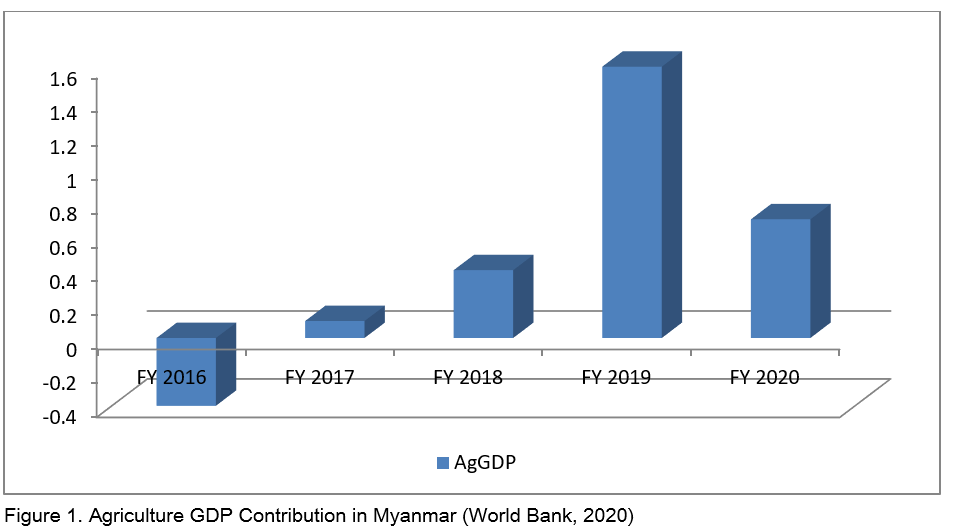

World Bank (Economic Monitor, 2020) estimated that the agricultural sector is expected to grow by an estimated 0.7% in Fiscal Year 2019-20, down from 1.6% in 2018-19, driven by strong crop production (Figure 1). In 2019-20, agriculture crop export has grown by 20% compared with last year. Favorable weather and increased demand for staple foods are expected to support crop production, but livestock and fisheries output is declining. Crop production, which accounts for 54% of agriculture output, has thus far proven resilient to the economic effects of the pandemic. Crop output is estimated to grow by an estimated 1.2% in 2019-20, supported by paddy rice and beans and pulses. Although beans and pulses represent a modest share of agricultural production, increased demand from India is driving the growth of the subsector. During 2019-20, India raised its import quota for mungbeans from 150,000 to 400,000 metric tons. However, perishable commodities, including fresh fruits and vegetables, which represent 8% of total crop production, have been hit hard by trade restrictions imposed by Myanmar’s major trading partners due to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. The evidence suggested that export loss in watermelons alone was estimated at around K 90 billion (US$65 million).

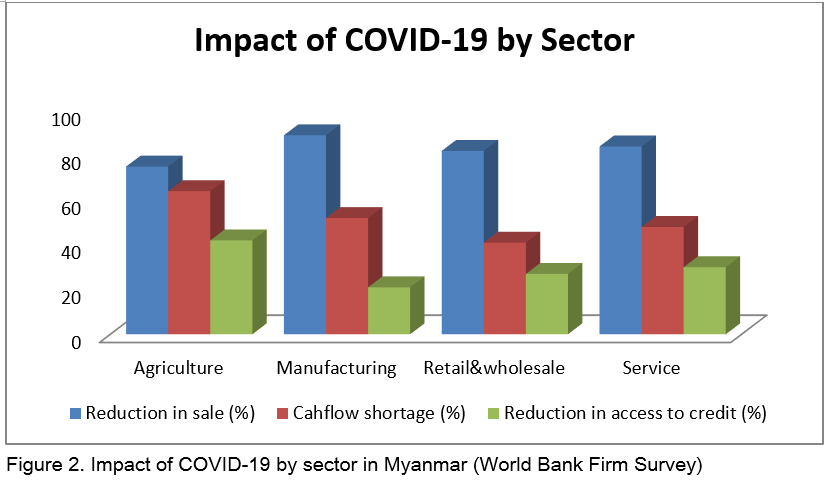

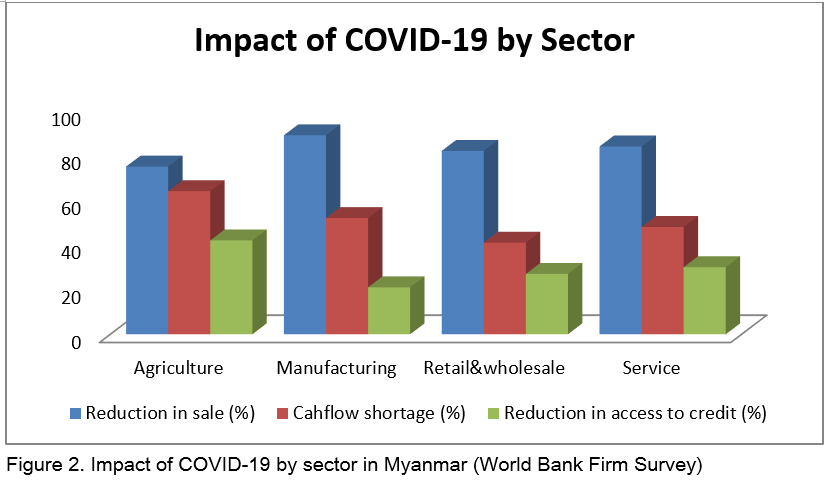

World Bank reported that across sectors, the three most commonly reported impacts of COVID-19 were lower sales, cash flow shortages, and reduced credit access. The share of firms reporting lower sales due to COVID-19 ranged from 90% in the manufacturing sector to 75% in the agricultural sector (Figure 2). Just over half of all firms reported cash flow shortages, and agricultural firms were the most likely to report both cash flow shortages and reduced access to credit. A full 64% of agricultural firms experienced cash flow shortages, well above the average of 51% for all firms, and about 42% of agricultural firms experienced reduced access to credit, versus 29% of all firms. COVID-19 caused a large share of firms to delay payments to suppliers, and agricultural firms were most likely to report delaying payments to financial institutions. In the crop production sector, the likely disruption of input supplies for the planting season may lead to seasonal and long-term food shortages and income losses, compromising purchasing power and access to healthy diets. Wage decreases and livelihood losses could deepen poverty, push households to resort to negative coping strategies, and compromise their resilience to any further shocks such as floods and droughts.

According to the FAO partner project (SLM-GEF), a rapid assessment on impact of COVID-19 has been conducted in the month of May 2020, in the townships of Mandalay, Chin and Ayerawaddy that agricultural credit is critical for many farmers in order to resume their farming operations. Indebtedness is already high for the vast majority of farmers even before COVID-19, and the pandemic had exacerbated the need for additional cash for farming and household consumption as the repayment burden prevents them from accessing loans or increases the cost of borrowing. Uneven presence of micro finance institutions and banks also makes it difficult for farmers to take institutional credit and their reliance on informal finance means incurring high costs of borrowing with interest rates ranging from 28% to 120% per annum. All these reflect the vulnerability that farmers face in terms of agricultural operations in the aftermath of the pandemic.

A rapid assessment study showed that more than 80% of household in study villages subjectively anticipated that the community may need relief food, cash assistance, livestock, and emergency agriculture assistance in one to three month’s time if COVID-19 situation continues. Job losses due to restrictions of movement, absence of markets are also found to be factors affecting the income sources of farmers and agriculture labor households.

Fishadapt has identified among fisher communities of Ayerawaddy, Rakhine and Yangon that 23% of households surveyed reported food shortages during the months of April-May 2020. About 64% reported a decline in the market prices of fish. Unemployment among fisher communities was reported to the extent of 70%. In Ayeyarwaddy 50% of the communities reported difficulties with transporting fish catches (17%) and gaining access to markets (33%), in Yangon region 40% of communities reported difficulties with transportation and 10% with market access and a further 10% reported they were unable to fish regularly. The study pointed out that strengthening agriculture and fisheries investments in production and marketing supply chains is one of the ways to address food insecurity at the local level. The livelihoods of rural households were highly vulnerable due to weather shocks, conflicts, or trade restrictions.

Given the importance of nutrition security, a sustainable food systems approach is also advocated especially with a focus on climate resilient sustainable agricultural practices that ensure food security of the small farmers. Measures like crop diversification and efficient nutrition management are some of the interventions in this respect.

Since the coronavirus pandemic, border restrictions and high demand-side risk due to the fiscal dependence on exports has exacerbated susceptibility to undernutrition and deficiencies. The World Food Programme’s (WFP) hunger map reports that 15.2 million people have insufficient food and 29.4% of children under 5 are reporting chronic malnutrition at the time of writing. Yangon has 25% of its population with insufficient food consumption, compared to Chin state with 64% and Shan state with over 40%. This highlights broader the inter-state poverty trends stated in a World Bank report on the country’s poverty. Therefore, the multi-dimensional effects of poverty such as malnutrition manifest through existing inter-state inequalities, widening socioeconomic gaps in the country.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, there are several negative impacts and challenges, among others (i) delaying commodity flows, (ii) restrictions on movement of farm machineries (iii) loss of markets for the produce, (iv) suspension of the export sector, (v) the disruption of supply chain, (vi) restriction on trade policy of neighboring countries, (vii) insufficient quality control, (viii) a decline of remittance from migrant workers, (iX) a decline of investments in agriculture and output volume have been faced by all stakeholders along the value chain of agricultural commodities. In addition, due to travel restrictions, revenue of agriculture and related sectors has dropped.

Disruptions to supply chains and constraints in border trade

Although WHO warned the public to take preventive measures and precautions and stockpiles food and necessities, Myanmar, as a large agricultural country, has showed no concern about the scarcity of food despite the fears over the coronavirus. As per Myanmar Rice Federation, it is said to be making efforts to keep the local rice market stable and maintain local rice sufficiency, in cooperation with traders, rice millers and concerned organizations in regions and states, by monitoring the daily situation in the world and reviewing the possible impacts on the local rice market.

In order for the public to be at ease, the government and some organizations said they have stocked piled rice reserves, and the traders have been selling them at a reasonable and affordable price. Myanmar suspended the issuance of new export licenses from 18 March to 30 April 2020. Furthermore, as the closures or disruptions of food supply chains in a country are having devastating impacts in other countries. The Myanmar Rice Federation has also ensured that there are surpluses of rice stocks to ensure food sufficiency in the country. For the current state of the coronavirus crisis, there is no shortage of food products. Most of the food consumed is produced in the country.

Despite Myanmar showing any worries regarding food security, the country could take lessons on how other countries like Singapore have been taking measures on the food supply chain. With years of contingency planning and recent moves to maintain the key flow of goods from the neighboring countries-Malaysia, Singapore helped itself in keeping supplies arriving through pandemic-related disruptions, even though the waves of panic buying has emptied some supermarket shelves of food.

One of the examples is that fruit businesses are experiencing the brunt of global value chain disruptions, suffering from significant revenue losses due to China-Myanmar border restrictions. China only allows 300 trucks to cross the border, resulting in massive pile-ups, and has closed 11 checkpoints for several months (other than for trade). So, the Myanmar drivers hand their trucks over to their Chinese counterparts at the border, which in itself is a logistical nightmare. Companies are reporting that they are unable to even cover transport costs, losing 3-4 million kyat (US$2,000-3,000). Truck operators are carrying goods one-way on demand but mostly with no round-trip services, which has resulted in increased prices for the movement of goods.

The COVID-19 crisis not only disrupted trade, but also severed the flows of remittance earnings from domestic and overseas migrants upon which many households in the country rely. These income shocks depressed consumers and farmers’ purchasing power, with faltering demand generating significant adverse second-round effects for businesses. The impact of restrictions put in place to control the virus on the employment and incomes of urban households have also been severe. Policymakers in Myanmar were operating in an extreme state of uncertainty in March 2020 when the global crisis quickly transformed into a national health and economic crisis. The government faced multiple challenges, including striking the right balance between controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, maintaining agri-food system operations, ensuring access to credit without amplifying levels of indebtedness and financial insecurity, and providing short term financial relief to those households most severely impacted at an unprecedented scale in the absence of strong social protection infrastructure. Additionally, evidence to guide decisions about these trade-offs was very limited. The research presented in this working paper is intended to address this evidence gap in regard to the agri-food system of Myanmar.

According to the National Enlightenment Institute (NEI) and SEED for Myanmar, fishery exports significantly rely on the Chinese market, employing more than 20,000 direct workers. With the closure of the Chinese market, fish and prawns are now on-hold in cold storages in Yangon. China is not guaranteeing it will buy the stored seafood during the crisis and these products are perishable. This creates an economic risk for the sector bearing unanticipated storage costs. Seafood products are destined to be sold and even if the Chinese market opens in the near future, the fishery sector will be impacted by the severe drop in market prices, excess supply, imposed transportation challenges, and the length of time left in the regulated fishing season.

Poor quality rubber produced is exported to China. Although rubber sheets can be safely stored for many months, buyers in China are not ordering the product. In addition, there are logistical and transport challenges to moving the products due to lockdown, curfews, and other restrictive mobility measures.

Although there are high-quality rubber producers, they are small in number, representing less than 30% of the sector. With a high degree of uncertainty, traders are reluctant to use their capital to buy rubber. Restrictive capital investments and cash flow, along with the high percentage of low-grade rubber produced have essentially shut down the rubber market.

Digital platform in the COVID- 19 Crisis

The current crisis reveals the importance of the digital economy and the development of productive capacities. There has been a large continuous shift to digital trading in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. At this stage, there is a clear need to strengthen the legal framework around e-commerce, improve the quality and affordability of digital infrastructure and enhance digital inclusion. For Myanmar, productive capacities are fundamental for diversifying economies and helping to achieve the goal of structural transformation.

Policy implication

There is need for building resilience of supply chains by increasing food production capacity, strengthening food reserves in the country, as well as improving national food logistics systems. There is also a need to emphasize on sound policies and programmes that focus on resilient food systems and nutrition-sensitive food diversification. Promoting sustainable and resilient food systems approaches will deliver food security and nutrition while building resilience to shocks and maintaining the economic, social and environmental basis to generate food security and nutrition which are important for rural and urban poor in the country.

As a medium and long-term plan, the Government of Myanmar is preparing the Myanmar Economic Recovery and Reform Plan (as of today, drafting stage) for the whole economy as well as for agriculture and food security as an opportunity to reform, where it includes development of inclusive and participatory policies for sustainable agriculture, fisheries and food systems.

REFERENCES

FAO. 2019. Sustainable cropland and forest management in priority agro-ecosystems of Myanmar.

FAO. 2017-21. FishAdapt: Strengthening the Adaptive Capacity and Resilience of Fisheries and Aquaculture-dependent Livelihoods in Myanmar. FAO ID: 628454

World Bank. 2020. Myanmar-Economic-Monitor. Myanmar in the Time COVID 19. The World Bank, IBRD, June 2020.

COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Socio-Economic Status, Agriculture, Livelihood, Food Security and Nutrition: Case of Myanmar

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 novel coronavirus spread around the world since December 2019. The first official case in Myanmar was reported on March 23rd 2020 where the first set of containment measures was introduced. In Myanmar, COVID-19 infection rate was low at the 1st wave but recently at the 2nd wave, confirmed cases increased in the months of August, September and October 2020. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing an unprecedented challenge to the Government of Myanmar and populations across country. The spread of the COVID-19 is placing huge pressure on health systems but it is also having social and economic impacts on across all sectors including food and agriculture. The Government of Myanmar released the COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) on April 28, 2020 to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic which includes monetary reform, increased government spending and strengthening of the health sector. It has 7 goals, 10 strategies, and 36 action plans and 78 actions. Among the action plans in CERP, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) had to take responsibilities of implementing the support for farmers, seed producers, agri-processors and owners of agri-businesses. In the crop production sector, the likely disruption of input supplies for the planting season may lead to seasonal and long-term food shortages and income losses, compromising purchasing power and access to healthy diets. Wage decreases and livelihood loss could deepen poverty, push households to resort to negative coping strategies, and compromise their resilience to any further shocks such as floods and droughts. Given the importance of nutrition security, a sustainable food systems approach is also advocated especially with a focus on climate resilient sustainable agriculture practices that ensure food security of the small farmers. Measures like crop diversification and efficient nutrition management are some of the interventions in this respect. There is a need for building resilience of supply chains by increasing food production capacity, strengthening food reserves in the country, as well as improving national food logistics systems. There is also a need to emphasize sound policies and programmes that focus on resilient food systems and nutrition-sensitive food diversification. Promoting sustainable and resilient food systems approaches will deliver food security and nutrition while building resilience to shocks and maintaining the economic, social and environmental basis to generate food security and nutrition which is important for rural and urban poor in the country.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, food security, nutrition, poverty, livelihood, agriculture

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 novel coronavirus spread around the world since December 2019. The first official case in Myanmar was reported on March 23rd, 2020 where the first set of containment measures was introduced. In Myanmar, COVID-19 infection rate was low at the 1st wave but recently at the 2nd wave, confirmed cases increased in the months of August, September and October 2020. The number of affected persons of COVID-19 is growing rapidly. As of November 3rd,2020, there were 54,607 confirmed cases, 1,282 deaths and 37,954 persons who recovered. To control and reduce the rate of spreading the virus, Myanmar has taken necessary actions such as physical distancing, lockdowns, travel and trade restrictions. Such kinds of actions had seriously reduced and mitigated the negative impacts on activities across the food system. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic had caused and is still causing severe challenges to the well-being, livelihood and safety of peoples and its adverse impact on the socio-economic development of Myanmar. This will have an impact on the economic recovery. Due to the pandemic, Myanmar’s GDP growth forecast for FY2019/20 has been revised downward from 6.4% to just 0.5% as all sectors experience adverse effects of varying intensity (World Bank, June 2020). The impacts of this pandemic are transmitted to all the sectors, especially the tourism-related services and transportation activities which are highly exposed, while the agriculture and information and communications technology (ICT) sectors have proven relatively resilient.

Government policy measures and actions for COVID-19

The government of Myanmar was highly aware of and responsive to the threat of COVID-19, both in terms of its health dimensions and its potential economic impacts. Due to its limited health services, the government relied on stringent public health restrictions, and the closure of all international borders, with the exception of returning international migrants. After a period of implementing only selective lockdowns in townships where COVID-19 cases emerged, a full lockdown was re-imposed on all townships in the Yangon metropolitan area in response to a surge in positive cases in the city. The lockdown was extended to Ayeyarwady, Bago and Mandalay regions and to Mon state on September 27, 2020. The Government of Myanmar released the COVID-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) on April 28, 2020 to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic which includes monetary reforms, increased government spending and strengthening of the health sector. It has 7 goals, 10 strategies, and 36 action plans and 78 actions. The action plans are being implemented by the relevant ministries in accordance with the nature of activities.

Among the action plans in CERP, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI) had to take responsibilities for implementing the support for farmers, seed producers, agri-processors and owners of agri-businesses. There were four sub action plans under action plan 2.1.7 (MOAL concern), such as (a) Support COVID-19 communication campaigns; (b) Cash for lending support to smallholder farmers who have lost sales revenue or remittance income to support purchases in time for monsoon planting; (c) Complement support with activities on productivity enhancement and market connectivity; and (d) Establishment of rural cash for work programme and other related activities following the lifting of movement restriction. For the implementation of those action plans, the government has approved 92.61 billion MMK (US$71.87 million fund for Agriculture Sector for immediate response plan against COVID- 19.

Activities identified included loan support to farmers, market connectivity and improvements in productivity through extension services. All these are expected to build resilience in the agriculture sector thereby ensuring food security. Meanwhile, in the production front, there was limited impact in the early months, agriculture trade and exports have been affected significantly due to the lockdown measures, closure of borders and movement of goods. Border trade in agriculture commodities appears to have been affected significantly over the past four months, although there is a turnaround in the most recent period.

Status of agriculture, food security and nutrition during COVID- 19 pandemic

Agriculture covers farming, fishing, and forestry which contributed to 25.6% of GDP annually in 2019. The development of agriculture sector means the development of the national economy since the agriculture sector is providing food, raw materials for agro based industries, non-food industries and so on. Nowadays, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing an unprecedented challenge to the Government of Myanmar and populations across the country. The spread of the COVID-19 is placing huge pressure on health systems but it is also having social and economic impacts on all sectors of society including food and agriculture.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on Myanmar’s food and nutrition security are complex in nature because the actors that govern food production and food supply chains include farmers, owners of agricultural inputs, processing plants, logistics services, traders and retailers, all of whom are under threat. Moreover, agricultural services such as storage, transportation and logistics, finance, marketing, research, and extension services have also been affected by the lockdown measures.

World Bank (Economic Monitor, 2020) estimated that the agricultural sector is expected to grow by an estimated 0.7% in Fiscal Year 2019-20, down from 1.6% in 2018-19, driven by strong crop production (Figure 1). In 2019-20, agriculture crop export has grown by 20% compared with last year. Favorable weather and increased demand for staple foods are expected to support crop production, but livestock and fisheries output is declining. Crop production, which accounts for 54% of agriculture output, has thus far proven resilient to the economic effects of the pandemic. Crop output is estimated to grow by an estimated 1.2% in 2019-20, supported by paddy rice and beans and pulses. Although beans and pulses represent a modest share of agricultural production, increased demand from India is driving the growth of the subsector. During 2019-20, India raised its import quota for mungbeans from 150,000 to 400,000 metric tons. However, perishable commodities, including fresh fruits and vegetables, which represent 8% of total crop production, have been hit hard by trade restrictions imposed by Myanmar’s major trading partners due to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. The evidence suggested that export loss in watermelons alone was estimated at around K 90 billion (US$65 million).

World Bank reported that across sectors, the three most commonly reported impacts of COVID-19 were lower sales, cash flow shortages, and reduced credit access. The share of firms reporting lower sales due to COVID-19 ranged from 90% in the manufacturing sector to 75% in the agricultural sector (Figure 2). Just over half of all firms reported cash flow shortages, and agricultural firms were the most likely to report both cash flow shortages and reduced access to credit. A full 64% of agricultural firms experienced cash flow shortages, well above the average of 51% for all firms, and about 42% of agricultural firms experienced reduced access to credit, versus 29% of all firms. COVID-19 caused a large share of firms to delay payments to suppliers, and agricultural firms were most likely to report delaying payments to financial institutions. In the crop production sector, the likely disruption of input supplies for the planting season may lead to seasonal and long-term food shortages and income losses, compromising purchasing power and access to healthy diets. Wage decreases and livelihood losses could deepen poverty, push households to resort to negative coping strategies, and compromise their resilience to any further shocks such as floods and droughts.

According to the FAO partner project (SLM-GEF), a rapid assessment on impact of COVID-19 has been conducted in the month of May 2020, in the townships of Mandalay, Chin and Ayerawaddy that agricultural credit is critical for many farmers in order to resume their farming operations. Indebtedness is already high for the vast majority of farmers even before COVID-19, and the pandemic had exacerbated the need for additional cash for farming and household consumption as the repayment burden prevents them from accessing loans or increases the cost of borrowing. Uneven presence of micro finance institutions and banks also makes it difficult for farmers to take institutional credit and their reliance on informal finance means incurring high costs of borrowing with interest rates ranging from 28% to 120% per annum. All these reflect the vulnerability that farmers face in terms of agricultural operations in the aftermath of the pandemic.

A rapid assessment study showed that more than 80% of household in study villages subjectively anticipated that the community may need relief food, cash assistance, livestock, and emergency agriculture assistance in one to three month’s time if COVID-19 situation continues. Job losses due to restrictions of movement, absence of markets are also found to be factors affecting the income sources of farmers and agriculture labor households.

Fishadapt has identified among fisher communities of Ayerawaddy, Rakhine and Yangon that 23% of households surveyed reported food shortages during the months of April-May 2020. About 64% reported a decline in the market prices of fish. Unemployment among fisher communities was reported to the extent of 70%. In Ayeyarwaddy 50% of the communities reported difficulties with transporting fish catches (17%) and gaining access to markets (33%), in Yangon region 40% of communities reported difficulties with transportation and 10% with market access and a further 10% reported they were unable to fish regularly. The study pointed out that strengthening agriculture and fisheries investments in production and marketing supply chains is one of the ways to address food insecurity at the local level. The livelihoods of rural households were highly vulnerable due to weather shocks, conflicts, or trade restrictions.

Given the importance of nutrition security, a sustainable food systems approach is also advocated especially with a focus on climate resilient sustainable agricultural practices that ensure food security of the small farmers. Measures like crop diversification and efficient nutrition management are some of the interventions in this respect.

Since the coronavirus pandemic, border restrictions and high demand-side risk due to the fiscal dependence on exports has exacerbated susceptibility to undernutrition and deficiencies. The World Food Programme’s (WFP) hunger map reports that 15.2 million people have insufficient food and 29.4% of children under 5 are reporting chronic malnutrition at the time of writing. Yangon has 25% of its population with insufficient food consumption, compared to Chin state with 64% and Shan state with over 40%. This highlights broader the inter-state poverty trends stated in a World Bank report on the country’s poverty. Therefore, the multi-dimensional effects of poverty such as malnutrition manifest through existing inter-state inequalities, widening socioeconomic gaps in the country.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, there are several negative impacts and challenges, among others (i) delaying commodity flows, (ii) restrictions on movement of farm machineries (iii) loss of markets for the produce, (iv) suspension of the export sector, (v) the disruption of supply chain, (vi) restriction on trade policy of neighboring countries, (vii) insufficient quality control, (viii) a decline of remittance from migrant workers, (iX) a decline of investments in agriculture and output volume have been faced by all stakeholders along the value chain of agricultural commodities. In addition, due to travel restrictions, revenue of agriculture and related sectors has dropped.

Disruptions to supply chains and constraints in border trade

Although WHO warned the public to take preventive measures and precautions and stockpiles food and necessities, Myanmar, as a large agricultural country, has showed no concern about the scarcity of food despite the fears over the coronavirus. As per Myanmar Rice Federation, it is said to be making efforts to keep the local rice market stable and maintain local rice sufficiency, in cooperation with traders, rice millers and concerned organizations in regions and states, by monitoring the daily situation in the world and reviewing the possible impacts on the local rice market.

In order for the public to be at ease, the government and some organizations said they have stocked piled rice reserves, and the traders have been selling them at a reasonable and affordable price. Myanmar suspended the issuance of new export licenses from 18 March to 30 April 2020. Furthermore, as the closures or disruptions of food supply chains in a country are having devastating impacts in other countries. The Myanmar Rice Federation has also ensured that there are surpluses of rice stocks to ensure food sufficiency in the country. For the current state of the coronavirus crisis, there is no shortage of food products. Most of the food consumed is produced in the country.

Despite Myanmar showing any worries regarding food security, the country could take lessons on how other countries like Singapore have been taking measures on the food supply chain. With years of contingency planning and recent moves to maintain the key flow of goods from the neighboring countries-Malaysia, Singapore helped itself in keeping supplies arriving through pandemic-related disruptions, even though the waves of panic buying has emptied some supermarket shelves of food.

One of the examples is that fruit businesses are experiencing the brunt of global value chain disruptions, suffering from significant revenue losses due to China-Myanmar border restrictions. China only allows 300 trucks to cross the border, resulting in massive pile-ups, and has closed 11 checkpoints for several months (other than for trade). So, the Myanmar drivers hand their trucks over to their Chinese counterparts at the border, which in itself is a logistical nightmare. Companies are reporting that they are unable to even cover transport costs, losing 3-4 million kyat (US$2,000-3,000). Truck operators are carrying goods one-way on demand but mostly with no round-trip services, which has resulted in increased prices for the movement of goods.

The COVID-19 crisis not only disrupted trade, but also severed the flows of remittance earnings from domestic and overseas migrants upon which many households in the country rely. These income shocks depressed consumers and farmers’ purchasing power, with faltering demand generating significant adverse second-round effects for businesses. The impact of restrictions put in place to control the virus on the employment and incomes of urban households have also been severe. Policymakers in Myanmar were operating in an extreme state of uncertainty in March 2020 when the global crisis quickly transformed into a national health and economic crisis. The government faced multiple challenges, including striking the right balance between controlling the COVID-19 pandemic, maintaining agri-food system operations, ensuring access to credit without amplifying levels of indebtedness and financial insecurity, and providing short term financial relief to those households most severely impacted at an unprecedented scale in the absence of strong social protection infrastructure. Additionally, evidence to guide decisions about these trade-offs was very limited. The research presented in this working paper is intended to address this evidence gap in regard to the agri-food system of Myanmar.

According to the National Enlightenment Institute (NEI) and SEED for Myanmar, fishery exports significantly rely on the Chinese market, employing more than 20,000 direct workers. With the closure of the Chinese market, fish and prawns are now on-hold in cold storages in Yangon. China is not guaranteeing it will buy the stored seafood during the crisis and these products are perishable. This creates an economic risk for the sector bearing unanticipated storage costs. Seafood products are destined to be sold and even if the Chinese market opens in the near future, the fishery sector will be impacted by the severe drop in market prices, excess supply, imposed transportation challenges, and the length of time left in the regulated fishing season.

Poor quality rubber produced is exported to China. Although rubber sheets can be safely stored for many months, buyers in China are not ordering the product. In addition, there are logistical and transport challenges to moving the products due to lockdown, curfews, and other restrictive mobility measures.

Although there are high-quality rubber producers, they are small in number, representing less than 30% of the sector. With a high degree of uncertainty, traders are reluctant to use their capital to buy rubber. Restrictive capital investments and cash flow, along with the high percentage of low-grade rubber produced have essentially shut down the rubber market.

Digital platform in the COVID- 19 Crisis

The current crisis reveals the importance of the digital economy and the development of productive capacities. There has been a large continuous shift to digital trading in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. At this stage, there is a clear need to strengthen the legal framework around e-commerce, improve the quality and affordability of digital infrastructure and enhance digital inclusion. For Myanmar, productive capacities are fundamental for diversifying economies and helping to achieve the goal of structural transformation.

Policy implication

There is need for building resilience of supply chains by increasing food production capacity, strengthening food reserves in the country, as well as improving national food logistics systems. There is also a need to emphasize on sound policies and programmes that focus on resilient food systems and nutrition-sensitive food diversification. Promoting sustainable and resilient food systems approaches will deliver food security and nutrition while building resilience to shocks and maintaining the economic, social and environmental basis to generate food security and nutrition which are important for rural and urban poor in the country.

As a medium and long-term plan, the Government of Myanmar is preparing the Myanmar Economic Recovery and Reform Plan (as of today, drafting stage) for the whole economy as well as for agriculture and food security as an opportunity to reform, where it includes development of inclusive and participatory policies for sustainable agriculture, fisheries and food systems.

REFERENCES

FAO. 2019. Sustainable cropland and forest management in priority agro-ecosystems of Myanmar.

FAO. 2017-21. FishAdapt: Strengthening the Adaptive Capacity and Resilience of Fisheries and Aquaculture-dependent Livelihoods in Myanmar. FAO ID: 628454

World Bank. 2020. Myanmar-Economic-Monitor. Myanmar in the Time COVID 19. The World Bank, IBRD, June 2020.