ABSTRACT

Sesame (Sesamum indicum), one of the major oilseed crops in Myanmar, is economically important not only for producing edible oil but also for export crops. Sesame cultivates everywhere in Myanmar and mainly in Magway, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions. The study was done to observe the sesame production and marketing by using the strength, weakness, opportunity and threat (SWOT) analysis in Ottarathiri, and Dekkhinathiri Township in Nay Pyi Taw. Field survey to 20 sesame farmers and 3 market stakeholders was done in December 2017. Workshop for SWOT Analysis and Policy Dialogue were done together with all stakeholders at Yezin Agricultural University (YAU) on December 28, 2017. The sample farmers had an average of 29 years of experience in sesame production. Most of the farmers had middle education level. Sahmon Nat (Black sesame) variety was sown by 90% of sample farmers because of market demand. Farmers sold sesame directly to primary collector and to local wholesaler by connection with the buyers before selling the product. All sample farmers sold sesame immediately after harvesting with cash down payment system. The weighting system used in selling sesame is Viss (1 Viss= 1.63 Kg). The cost for packaging was shared by farmers and broker. Cleanliness, moisture content and purity of sesame are the most important factors in standardizing and grading of sesame. Mode of transportation was mainly by motorcycle. The highest proportion of farmers directly sold raw sesame to primary collectors who distributed to oil millers, local wholesalers from Yangon, Mandalay and other areas. Strength factors of sesame production are favorable place, domestic market demand, good transportation, and machinery availability. Weaknesses are extension, high cost of production and low yield. Opportunity factors are: crops diversification and potential demand. The threat factors were climate change, marketing and price risks, perishability, high cost of transportation, lack of quality seed and poor agricultural policy. The critical intervention areas for improving sesame farmer livelihoods are SMEs for value added production, direct marketing, quality seeds, systematic cultural practices, alternate cropping patterns for disease outbreak, contract farming, micro finance and extension facilities.

Keywords: sesame, field survey, marketing, production, SWOT

INTRODUCTION

Sesame production in Myanmar

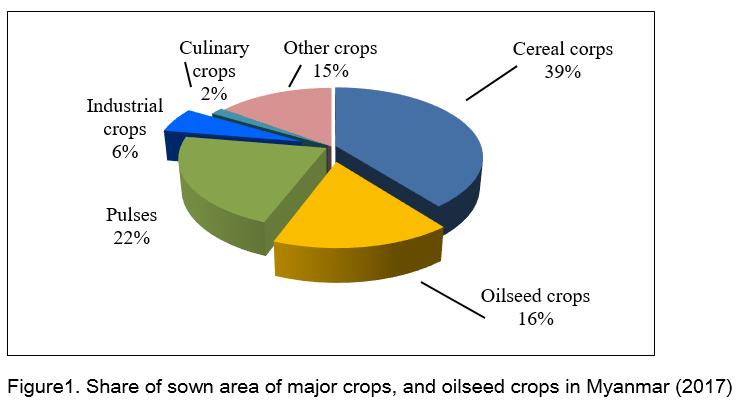

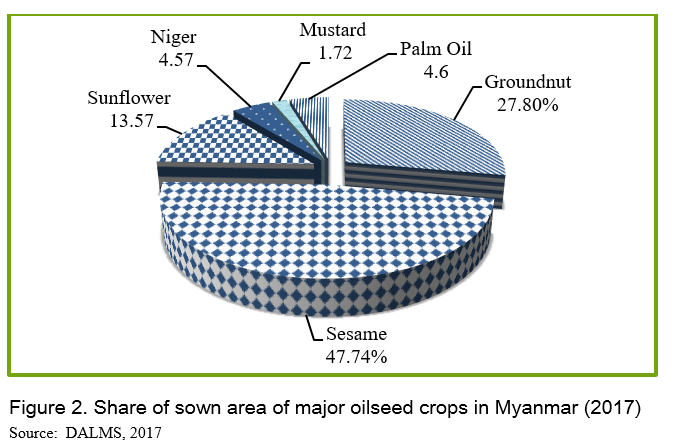

Sesame (Sesamum indicum), one of the major oilseed crops in Myanmar, is economically important not only for producing edible oil but also for export crops. Sesame cultivates everywhere in Myanmar and mainly in Magway, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions. In the report of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation in 2016-2017, the sown and harvested areas of sesame were about 1,553 and 1,495 thousand hectares respectively. Average yield per hectare was 553 kg. Major oil seed crops are grown about 16% of total crop sown area and sesame is grown about 47.7% of major oil seed crops area in 2016-2017 (Figure 1 and 2)

Objectives of the study

- Mapping the current sesame production and market conditions of the farmers in Nay Pyi Taw

- Finding the strength, weakness, opportunity and threat (SWOT) of sesame production in Nay Pyi Taw

- Practicing the key stakeholders participatory policy formulation by arranging policy dialogue and analysis workshops

METHODOLOGY

Study sites selection for data collection

Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory consists of eight administrative townships: Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri and Zeyarthiri townships (Department of Population 2015). The study area selected was Ottarathiri and Dekkhinathiri townships in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Selection of the study area was focused on the ongoing Fostering Agricultural Revitalization in Myanmar (IFAD-FARM) project in order to develop the sustainable and scalable smallholders.

Data collection and analysis

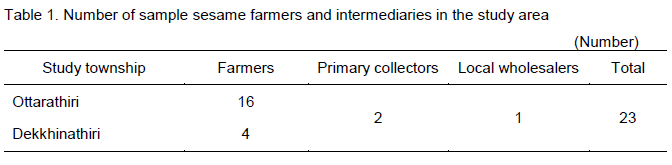

To access the current marketing performance of sesame in Nay Pyi Taw, a field survey for primary data collection was undertaken in December 2017. For primary survey, total sample size was 20 sesame farmers, and 3 market intermediaries along the production and marketing channels. First survey was done with 20 sesame growers and second survey was done with 3 intermediaries of sesame (Table 1).

Data were collected for the investigation of demographic and socio-economic conditions and marketing activities, marketing cost, marketing margin of various stakeholders, marketing channels and constraints and challenges and possible solutions. The market related questionnaire was used to collect farm level detailed measures of prices and quantity, purchased and sold system, marketing costs of various stakeholders’, storage facilities, transport facilities, and access to market information.

The collected data were digitized collated and the outputs were transmitted. The quantitative data were entered into a pre-defined format to assess outcomes. For the quantitative analysis, the data were analyzed through SPSS statistical software to obtain results.

Workshop for SWOT analysis and policy dialogue to formulate policy implication

To establish a regional and national network for Value Chain and Market System Development with strong national partners (India, Bangladesh, China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos, and Myanmar), IFAD supported to build capacities of implementing agencies for value chain programs started from 2016-2020. Under this network, on December 28, 2017, a workshop was organized that brought together stakeholders to discuss the emerging issues in value chain, agriculture policy and the implementation. The objectives of this stakeholder’s workshop were: to discuss the findings of the value chain study and formulation of policy implication for solving the bottlenecks with the participation of related stakeholders.

The workshop was held at the YAU, Myanmar on December 28, 2017. In the workshop, a total of 28 participants including 4 Knowledge center staff from the FARM project, each of 10 farmers for the sesame and 3 of market intermediaries, 11 of agricultural economics master students and teachers. A workshop was arranged for discussion and formulation regarding the value chain upgrading process, intervention areas to overcome the weaknesses and threats of selected crops by group participation. Based on the opinions for improvement of current situation alone, the value chains of sesame, the opinions were analyzed by SWOT analysis and conclusion was done for critical intervention areas.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sesame farmers in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area

‐Demographic characteristics of sample sesame farmers

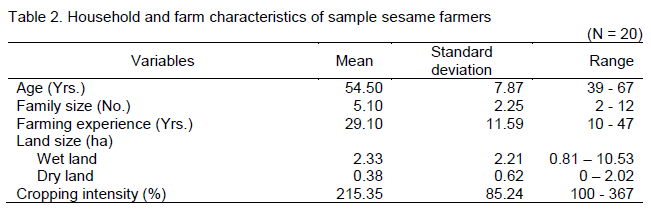

Average age of sample farmers was 54.50 years with a standard deviation of 7.87. The interviewed households had family size ranging from 2 to 12 and the average was 5.10 persons. The sample farmers had an average of 29.01 years of experience in sesame production, ranging from 10 to 47 years. The sample farmers owned an average 2.33 ha of wet land and 0.38 ha of dry land. The land size ranged from 0.81 to 10.53 ha in wet land and 0 to 2.02 ha in dry land. The average cropping intensity was 215.35% with a standard deviation of 85.24 (Table 2).

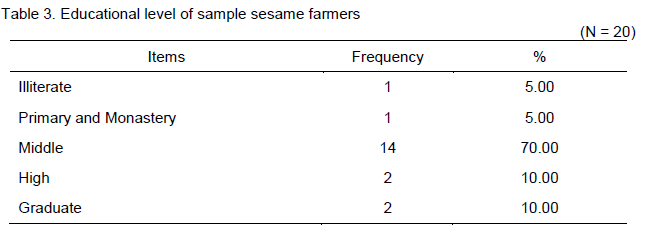

Education level of the sample farmers were categorized into five groups. “Illiterate education level” means the farmers cannot read and write. “Monastery education level” defines informal schooling and the farmers can read and write, primary formal schooling up to 5 years, so monastery and primary education level are assumed as one group. Middle education level is described for formal schooling up to 9 years and high education level; formal schooling up to 11 years. The last graduate education level refers to those who had educational degree from a university. The education level of farmers was assumed to determine the decision making of their farming system. Majority (70%) of sample farmers had middle education level and minority (5%) had illiterate as well as primary and monastery education level (Table 3).

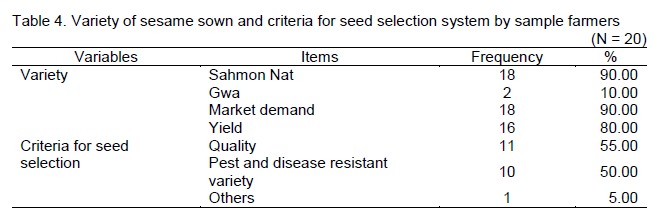

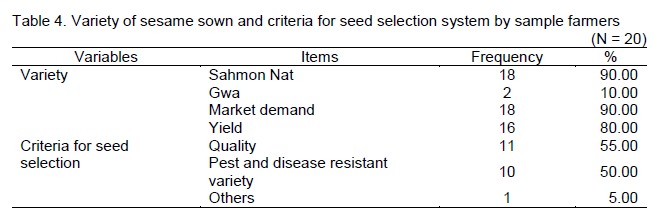

Variety of sesame sown and criteria for seed selection system is indicated in Table 4. About 90% of sample sesame farmers cultivated Sahmon Nat variety of sesame. Gwa variety was sown by 10% of farmers. About 90% of farmers chose the variety based on marketed variety, (80%) based on yield, 55% based on quality, 50% based on pest and disease resistant variety and only 5% on others.

‐Marketing activities of sample sesame farmers

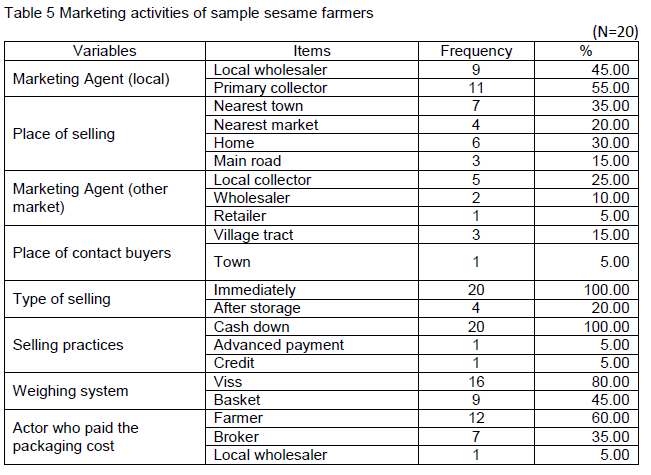

Local wholesalers (45%) and primary collector (55%) were discovered as market intermediaries. Most of the farmers stayed in the village situated near the town, so they have opportunity of direct marketing to local wholesalers. As a result of selling place, about 35% of farmers sold their product in the nearest town, 20% in the nearest market, 30% in their homes and 15% in the main roads. Marketing agents from other locations are connected by about 40% of farmers. As shown in Table 5, the sample farmers contacted the average number of 4.28 buyers before selling their product. In Table 5, the places of contact buyers were in village tract (15%) and in town (5%) respectively. All farmers sold their sesame product immediately to market intermediaries and only 20% of sample farmers also stored as seeds and sold their crop immediately after harvesting. Cash down selling system was practiced by all sample farmers (100%). Only 5% each of farmers practiced the advanced payment system and credit system respectively. Regarding the selling system of respondents, 5% of respondent farmers used both cash down system and advanced payment system or credit system.

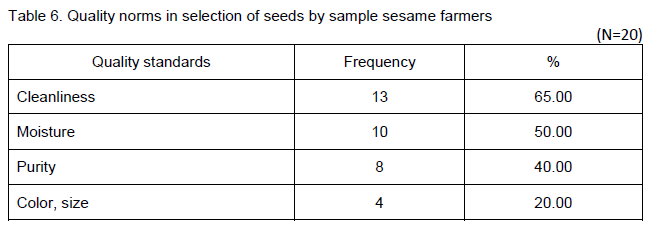

In selling unit for sesame, viss (traditional Myanmar units of measurement – 1.63 kg) measurement system was used by 80% and basket measurement system was used by 45% of sample farmers. Majority (60%) of farmers answered that the packaging cost was paid by themselves and minority (5%) by local wholesalers (Table 5). Local norms in selection of seeds by sample sesame farmers are presented in Table 6. Cleanliness is the most important local norm for sesame and it was answered by 65% of farmers. Only 25% of sample farmers responded that color and size are the major local norm for sesame.

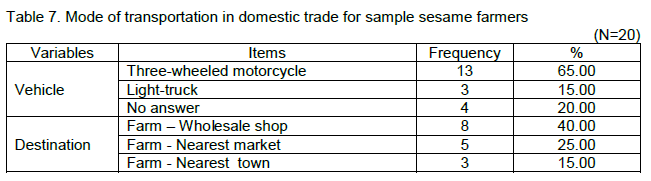

‐Mode of transportation by sample farmers

Table 7 describes the mode of transportation in sesame domestic trade for sample sesame farmers. The percentage of sample sesame farmers who utilized three-wheeled motorcycles for transporting sesame was 65% and it was the highest proportion among the use of transportation vehicles. About 20% of farmers did not answer the question regarding the mode of transport because of buying directly by the wholesalers. One farmer transported the sesame to the market destination by both three-wheeled motorcycles and light-trucks. Among the farmers who utilized vehicles for transportation, about 40% of sample farmers transported from farm to wholesale shops, followed by nearest markets (25%) and nearest towns (15%) respectively.

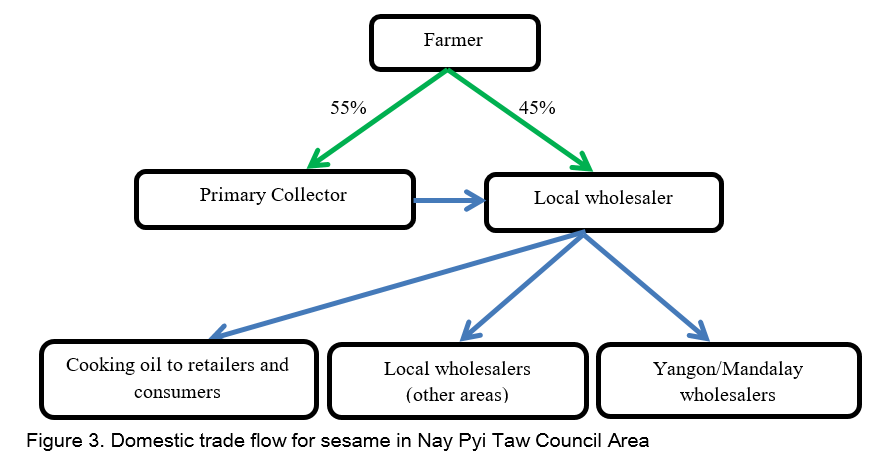

DOMESTIC TRADE FLOW OF SESAME IN NAY PYI TAW

Figure 3 shows sesame domestic trade flow in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. In the study area, the sample farmers connected with two types of market intermediaries in selling practices. The major proportion of farmers sold raw sesame to primary collectors (55%) but the rest proportion (45%) directly sold to local wholesalers. The local wholesalers sold the sesame to Yangon/Mandalay wholesalers and local wholesalers from other areas. The local wholesalers were also millers who produce sesame oil. They sold the cooking sesame oil to retailers and consumers.

SWOT Analysis for sesame production

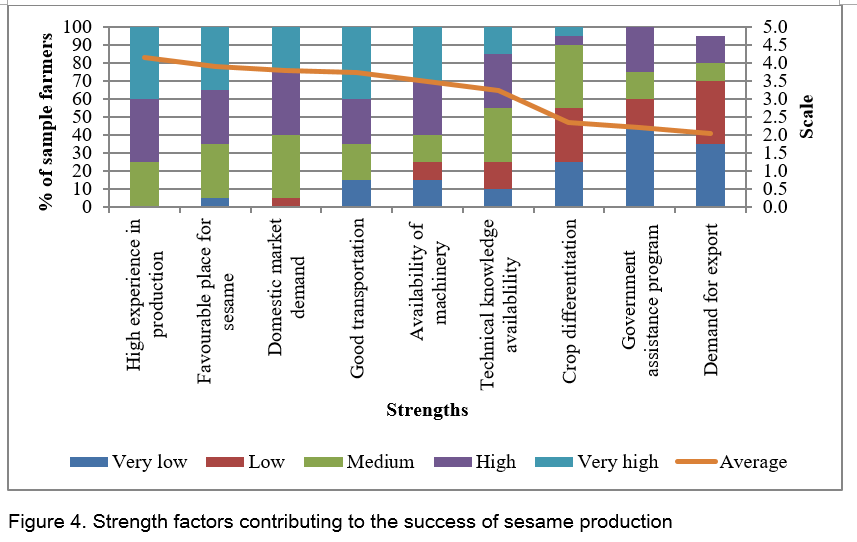

‐Percentage contribution of sample farmers for SWOT analysis

Figure 4 represents the strength factors contributing to the success of sesame production. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. As sesame is an unpredictable crop, high experience in sesame production was the major strength (4.15) of sample sesame farmers. Other strength factors that contributed between high and medium categories were favorable place for sesame (3.90), domestic market demand (3.80), and good transportation (3.75), availability of machinery (3.50) and technical knowledge availability (3.25). The strength factors that ranked between medium and low were crop differentiation (2.35), government assistance program (2.20) and demand for export (2.05). There was no strength factors scaled between 1 and 2.

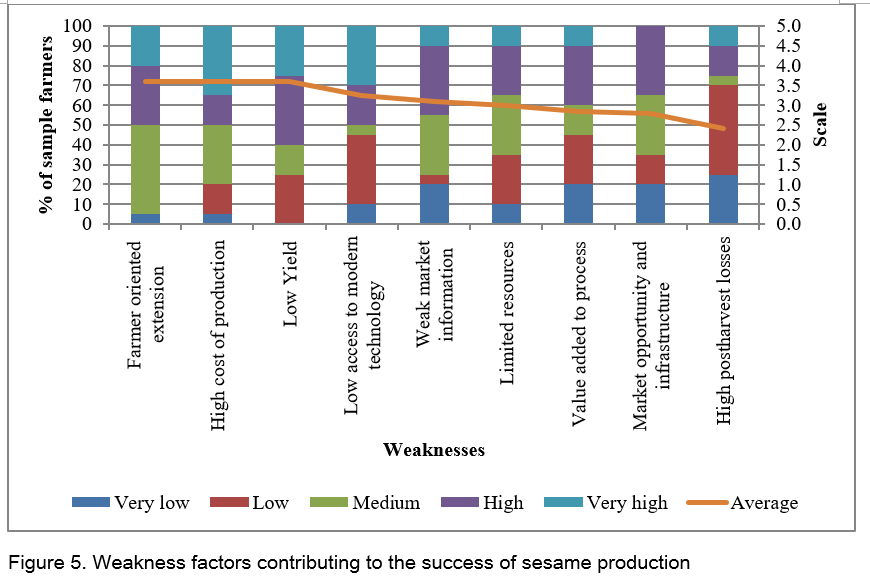

Weakness factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 3. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. The average number of high and very high weaknesses for sample sesame farmers was not found. The maximum average scale was 3.60 found in the weakness factors of farmer oriented extension, high cost of production and low yield; therefore it was ranged between high and medium weaknesses. The value of scale ranged between high and medium was found in the weakness factors of low access to modern technology (3.25) and weak market information (3.10). The medium weakness was limited resources (3.00). The other weakness factors that contributed between medium and low were value added to process (2.85), market opportunity and infrastructure (2.80) and high postharvest losses (2.40).

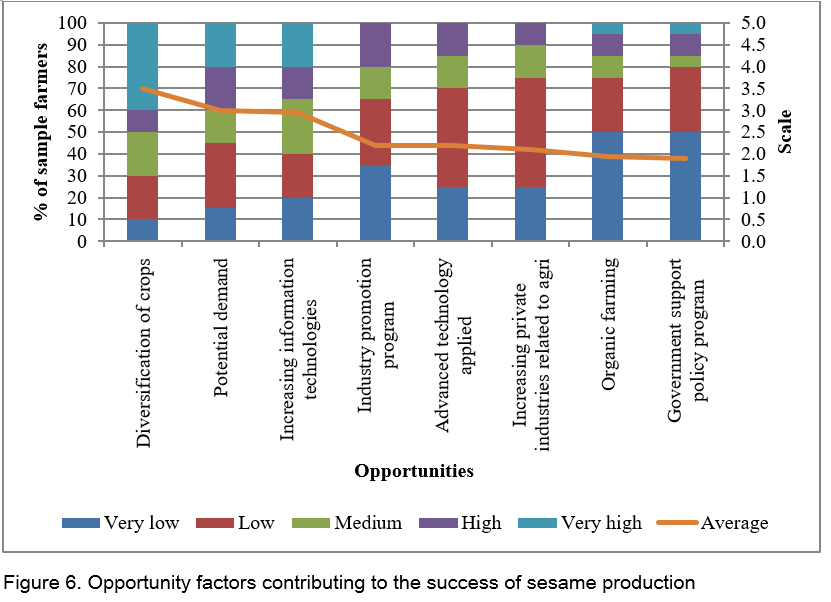

Opportunity factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 6. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. There was no ranking among the eight opportunity factors ranging between very high and high. Opportunities considered between high and medium categories were: diversification of crops (3.50) and potential demand (3.00). Factors in the medium and low categories included: increasing information technologies (2.95), industry promotion program (2.20), advanced technology applied (2.20) and increasing private industries related to agriculture (2.10). The opportunities ranged between low and very low mean were organic farming (1.95) and government support policy (1.90).

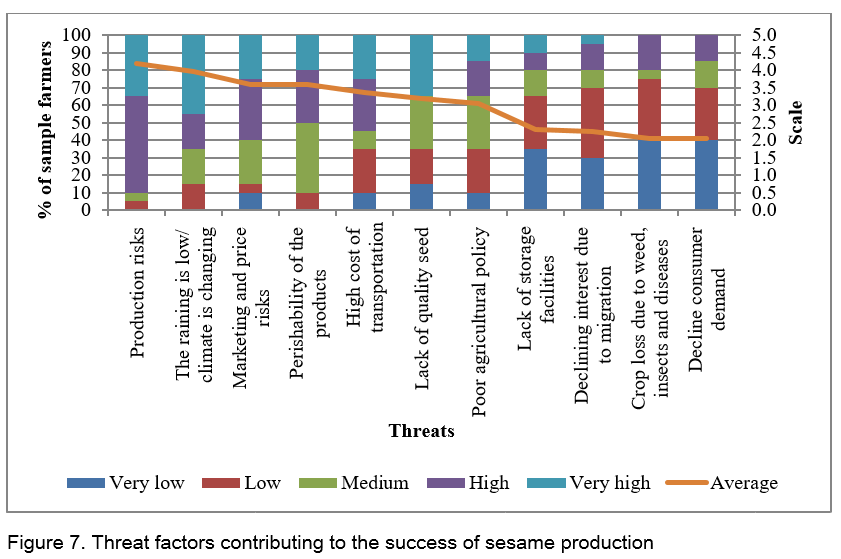

Threat factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 7. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. The maximum average scale was 4.20 and it was found in production risks: it means that production risks are the major threat that ranged between very high and high. The threats that contributed between high and medium were climate change (3.95), marketing and price risks (3.60), perishability of the products (3.60), high cost of transportation (3.35), lack of quality seed (3.20) and poor agricultural policy (3.05), lack of storage facilities (2.30), declining interest due to migration (2.25), and crop loss due to weed, insects and diseases (2.05) as well as decline consumer demand (2.05) were the threats that ranked between medium and low.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the case of sesame production, the important intervention areas for development better than current situations are as follows:

- Value-added products of sesame such as sesame oil and snacks enterprises should be developed in order to increase the sesame demand (Opportunity creating small and medium enterprise of value added products of sesame)

- Traders such as brokers and wholesalers practice

s direct buying from producers (For selling sesame, direct buying by brokers to village is more convenient and important issued for farmers)

- There should be good support for marketable quality of sesame seeds (improved varieties)

- Systematic cultural practices and precise information (by demonstrating technologies and prevention methods at the farm level) should go hand in hand with each other.

- There should be provision of systematic prevention methods for pests and diseases of sesame.

- Consider developing the contract farming scheme in sesame production (Example from Myanmar Agri. Food (MAF) Company which is doing the contract type of farming in some vegetables to the farmers by supporting storage facilities and value added products. This company exported quality vegetables to Japan.

- Micro financing with low interest rate in sesame production is essential.

- Training to the extension staff who can give systematic information and technologies of sesame production is very important.

REFERENCES

DALMS (Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics). (2017). Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

Sesame Value Chain and SWOT Analysis in Nay Pyi Taw of Myanmar: Key Stakeholder Participatory Policy Formulation Practice

ABSTRACT

Sesame (Sesamum indicum), one of the major oilseed crops in Myanmar, is economically important not only for producing edible oil but also for export crops. Sesame cultivates everywhere in Myanmar and mainly in Magway, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions. The study was done to observe the sesame production and marketing by using the strength, weakness, opportunity and threat (SWOT) analysis in Ottarathiri, and Dekkhinathiri Township in Nay Pyi Taw. Field survey to 20 sesame farmers and 3 market stakeholders was done in December 2017. Workshop for SWOT Analysis and Policy Dialogue were done together with all stakeholders at Yezin Agricultural University (YAU) on December 28, 2017. The sample farmers had an average of 29 years of experience in sesame production. Most of the farmers had middle education level. Sahmon Nat (Black sesame) variety was sown by 90% of sample farmers because of market demand. Farmers sold sesame directly to primary collector and to local wholesaler by connection with the buyers before selling the product. All sample farmers sold sesame immediately after harvesting with cash down payment system. The weighting system used in selling sesame is Viss (1 Viss= 1.63 Kg). The cost for packaging was shared by farmers and broker. Cleanliness, moisture content and purity of sesame are the most important factors in standardizing and grading of sesame. Mode of transportation was mainly by motorcycle. The highest proportion of farmers directly sold raw sesame to primary collectors who distributed to oil millers, local wholesalers from Yangon, Mandalay and other areas. Strength factors of sesame production are favorable place, domestic market demand, good transportation, and machinery availability. Weaknesses are extension, high cost of production and low yield. Opportunity factors are: crops diversification and potential demand. The threat factors were climate change, marketing and price risks, perishability, high cost of transportation, lack of quality seed and poor agricultural policy. The critical intervention areas for improving sesame farmer livelihoods are SMEs for value added production, direct marketing, quality seeds, systematic cultural practices, alternate cropping patterns for disease outbreak, contract farming, micro finance and extension facilities.

Keywords: sesame, field survey, marketing, production, SWOT

INTRODUCTION

Sesame production in Myanmar

Sesame (Sesamum indicum), one of the major oilseed crops in Myanmar, is economically important not only for producing edible oil but also for export crops. Sesame cultivates everywhere in Myanmar and mainly in Magway, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions. In the report of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation in 2016-2017, the sown and harvested areas of sesame were about 1,553 and 1,495 thousand hectares respectively. Average yield per hectare was 553 kg. Major oil seed crops are grown about 16% of total crop sown area and sesame is grown about 47.7% of major oil seed crops area in 2016-2017 (Figure 1 and 2)

Objectives of the study

METHODOLOGY

Study sites selection for data collection

Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory consists of eight administrative townships: Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri and Zeyarthiri townships (Department of Population 2015). The study area selected was Ottarathiri and Dekkhinathiri townships in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Selection of the study area was focused on the ongoing Fostering Agricultural Revitalization in Myanmar (IFAD-FARM) project in order to develop the sustainable and scalable smallholders.

Data collection and analysis

To access the current marketing performance of sesame in Nay Pyi Taw, a field survey for primary data collection was undertaken in December 2017. For primary survey, total sample size was 20 sesame farmers, and 3 market intermediaries along the production and marketing channels. First survey was done with 20 sesame growers and second survey was done with 3 intermediaries of sesame (Table 1).

Data were collected for the investigation of demographic and socio-economic conditions and marketing activities, marketing cost, marketing margin of various stakeholders, marketing channels and constraints and challenges and possible solutions. The market related questionnaire was used to collect farm level detailed measures of prices and quantity, purchased and sold system, marketing costs of various stakeholders’, storage facilities, transport facilities, and access to market information.

The collected data were digitized collated and the outputs were transmitted. The quantitative data were entered into a pre-defined format to assess outcomes. For the quantitative analysis, the data were analyzed through SPSS statistical software to obtain results.

Workshop for SWOT analysis and policy dialogue to formulate policy implication

To establish a regional and national network for Value Chain and Market System Development with strong national partners (India, Bangladesh, China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos, and Myanmar), IFAD supported to build capacities of implementing agencies for value chain programs started from 2016-2020. Under this network, on December 28, 2017, a workshop was organized that brought together stakeholders to discuss the emerging issues in value chain, agriculture policy and the implementation. The objectives of this stakeholder’s workshop were: to discuss the findings of the value chain study and formulation of policy implication for solving the bottlenecks with the participation of related stakeholders.

The workshop was held at the YAU, Myanmar on December 28, 2017. In the workshop, a total of 28 participants including 4 Knowledge center staff from the FARM project, each of 10 farmers for the sesame and 3 of market intermediaries, 11 of agricultural economics master students and teachers. A workshop was arranged for discussion and formulation regarding the value chain upgrading process, intervention areas to overcome the weaknesses and threats of selected crops by group participation. Based on the opinions for improvement of current situation alone, the value chains of sesame, the opinions were analyzed by SWOT analysis and conclusion was done for critical intervention areas.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sesame farmers in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area

‐Demographic characteristics of sample sesame farmers

Average age of sample farmers was 54.50 years with a standard deviation of 7.87. The interviewed households had family size ranging from 2 to 12 and the average was 5.10 persons. The sample farmers had an average of 29.01 years of experience in sesame production, ranging from 10 to 47 years. The sample farmers owned an average 2.33 ha of wet land and 0.38 ha of dry land. The land size ranged from 0.81 to 10.53 ha in wet land and 0 to 2.02 ha in dry land. The average cropping intensity was 215.35% with a standard deviation of 85.24 (Table 2).

Education level of the sample farmers were categorized into five groups. “Illiterate education level” means the farmers cannot read and write. “Monastery education level” defines informal schooling and the farmers can read and write, primary formal schooling up to 5 years, so monastery and primary education level are assumed as one group. Middle education level is described for formal schooling up to 9 years and high education level; formal schooling up to 11 years. The last graduate education level refers to those who had educational degree from a university. The education level of farmers was assumed to determine the decision making of their farming system. Majority (70%) of sample farmers had middle education level and minority (5%) had illiterate as well as primary and monastery education level (Table 3).

Variety of sesame sown and criteria for seed selection system is indicated in Table 4. About 90% of sample sesame farmers cultivated Sahmon Nat variety of sesame. Gwa variety was sown by 10% of farmers. About 90% of farmers chose the variety based on marketed variety, (80%) based on yield, 55% based on quality, 50% based on pest and disease resistant variety and only 5% on others.

‐Marketing activities of sample sesame farmers

Local wholesalers (45%) and primary collector (55%) were discovered as market intermediaries. Most of the farmers stayed in the village situated near the town, so they have opportunity of direct marketing to local wholesalers. As a result of selling place, about 35% of farmers sold their product in the nearest town, 20% in the nearest market, 30% in their homes and 15% in the main roads. Marketing agents from other locations are connected by about 40% of farmers. As shown in Table 5, the sample farmers contacted the average number of 4.28 buyers before selling their product. In Table 5, the places of contact buyers were in village tract (15%) and in town (5%) respectively. All farmers sold their sesame product immediately to market intermediaries and only 20% of sample farmers also stored as seeds and sold their crop immediately after harvesting. Cash down selling system was practiced by all sample farmers (100%). Only 5% each of farmers practiced the advanced payment system and credit system respectively. Regarding the selling system of respondents, 5% of respondent farmers used both cash down system and advanced payment system or credit system.

In selling unit for sesame, viss (traditional Myanmar units of measurement – 1.63 kg) measurement system was used by 80% and basket measurement system was used by 45% of sample farmers. Majority (60%) of farmers answered that the packaging cost was paid by themselves and minority (5%) by local wholesalers (Table 5). Local norms in selection of seeds by sample sesame farmers are presented in Table 6. Cleanliness is the most important local norm for sesame and it was answered by 65% of farmers. Only 25% of sample farmers responded that color and size are the major local norm for sesame.

‐Mode of transportation by sample farmers

Table 7 describes the mode of transportation in sesame domestic trade for sample sesame farmers. The percentage of sample sesame farmers who utilized three-wheeled motorcycles for transporting sesame was 65% and it was the highest proportion among the use of transportation vehicles. About 20% of farmers did not answer the question regarding the mode of transport because of buying directly by the wholesalers. One farmer transported the sesame to the market destination by both three-wheeled motorcycles and light-trucks. Among the farmers who utilized vehicles for transportation, about 40% of sample farmers transported from farm to wholesale shops, followed by nearest markets (25%) and nearest towns (15%) respectively.

DOMESTIC TRADE FLOW OF SESAME IN NAY PYI TAW

Figure 3 shows sesame domestic trade flow in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. In the study area, the sample farmers connected with two types of market intermediaries in selling practices. The major proportion of farmers sold raw sesame to primary collectors (55%) but the rest proportion (45%) directly sold to local wholesalers. The local wholesalers sold the sesame to Yangon/Mandalay wholesalers and local wholesalers from other areas. The local wholesalers were also millers who produce sesame oil. They sold the cooking sesame oil to retailers and consumers.

SWOT Analysis for sesame production

‐Percentage contribution of sample farmers for SWOT analysis

Figure 4 represents the strength factors contributing to the success of sesame production. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. As sesame is an unpredictable crop, high experience in sesame production was the major strength (4.15) of sample sesame farmers. Other strength factors that contributed between high and medium categories were favorable place for sesame (3.90), domestic market demand (3.80), and good transportation (3.75), availability of machinery (3.50) and technical knowledge availability (3.25). The strength factors that ranked between medium and low were crop differentiation (2.35), government assistance program (2.20) and demand for export (2.05). There was no strength factors scaled between 1 and 2.

Weakness factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 3. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. The average number of high and very high weaknesses for sample sesame farmers was not found. The maximum average scale was 3.60 found in the weakness factors of farmer oriented extension, high cost of production and low yield; therefore it was ranged between high and medium weaknesses. The value of scale ranged between high and medium was found in the weakness factors of low access to modern technology (3.25) and weak market information (3.10). The medium weakness was limited resources (3.00). The other weakness factors that contributed between medium and low were value added to process (2.85), market opportunity and infrastructure (2.80) and high postharvest losses (2.40).

Opportunity factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 6. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. There was no ranking among the eight opportunity factors ranging between very high and high. Opportunities considered between high and medium categories were: diversification of crops (3.50) and potential demand (3.00). Factors in the medium and low categories included: increasing information technologies (2.95), industry promotion program (2.20), advanced technology applied (2.20) and increasing private industries related to agriculture (2.10). The opportunities ranged between low and very low mean were organic farming (1.95) and government support policy (1.90).

Threat factors contributing to the success of sesame production are presented in Figure 7. The factors are scaled from 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. The maximum average scale was 4.20 and it was found in production risks: it means that production risks are the major threat that ranged between very high and high. The threats that contributed between high and medium were climate change (3.95), marketing and price risks (3.60), perishability of the products (3.60), high cost of transportation (3.35), lack of quality seed (3.20) and poor agricultural policy (3.05), lack of storage facilities (2.30), declining interest due to migration (2.25), and crop loss due to weed, insects and diseases (2.05) as well as decline consumer demand (2.05) were the threats that ranked between medium and low.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the case of sesame production, the important intervention areas for development better than current situations are as follows:

sdirect buying from producers (For selling sesame, direct buying by brokers to village is more convenient and important issued for farmers)REFERENCES

DALMS (Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics). (2017). Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.