ABSTRACT

Sesame is mainly grown in the central dry zone of Myanmar, in which, Magway Region occupied the largest sesame sown area for many years. Informal contract agreement among sesame farmers and buyers are practiced in Aunglan Township, Magway Region. This study aimed to understand the production and marketing performances of sesame farmers under contract and non-contract systems in the study area. By using purposive random sampling procedure, a total of 102 sesame farmers in Aunglan Township were interviewed by using structured questionnaires during November and December, 2017. These findings indicated that contract farmers were younger and had less farming experiences as compared to non-contract farmers. Contract farmers received credit and market information from more diverse sources and more participated in training, meeting and field demonstration which were mostly related to sesame production practices in comparison with non-contract farmers. Production cost of sesame by contract farmers was higher as compared to non-contract farmers due to their higher usage of FYM, compound fertilizers, gypsum and fungicide. However, it did not affect their returns because contract farmers received better sesame yield in comparison with non-contract farmers. Climate change, labor scarcity, unstable price and high input cost were major constraints for rain-fed dependent sesame farmers. There was still lack of advanced technology in quality checking, grading, thus, technology investment is crucially needed for producing good quality seeds. Sesame farmers should pay attention not only to quality improvement but also to overcoming current constraints along the supply chain in order to maintain global export share of Myanmar sesame.

Keywords: Sesame, supply chain, contract, Magway region, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Oilseeds, being the third most important crop group after cereal and pulses in Myanmar agriculture, covered nearly 8.2 million acres of the total crop sown area. There are many kinds of oilseed crops such as groundnut, sesame, sunflower, mustard and niger. The most extensive and traditional oilseed crop is sesame and it occupies the largest sown area (approximately 48.83% of total oilseed crop areas), followed by the groundnut 31.79% of total oilseed crop areas in 2017-2018 as shown in Figure 1 (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018).

Myanmar produced the second highest sesame production (764,320 MT) in the world after Tanzania, with a sesame yield of 0.52 MT/ha in 2017 as shown in Table 1. It can be observed that high yield group (Tanzania, Nigeria, and China) achieved sesame yield above 1 MT/ha while low yield group (Myanmar, India, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Burkina Fuso) obtained round about 0.5 MT/ha only on average. Myanmar occupied 13.81% of the total world production and 34.81% of Asia. In the world’s sesame export, Myanmar occupied 1.29% of the total world’s export and 1.86% of the total world’s sesame export earnings in 2016 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics [FAOSTAT], 2018).

.PNG)

Figure 1. Shares of sown area for oilseed crops in Myanmar during 2017-2018

Source: MOALI, 2018

Table1. Harvested area, yield, production and export status of sesame by top eight global sesame producing countries in 2017

|

Countries

|

Harvested area

('000 ha)

|

Average yield (MT/ha)

|

Production ('000 MT)

|

Export *

|

|

Volume

('000 MT)

|

Value

(Million US$)

|

|

World

|

9,983.17

|

0.55

|

5,531.95

|

1,895.58

|

2,069.27

|

|

Asia

|

3,952.06

|

0.56

|

2,195.09

|

460.94

|

610.41

|

|

Tanzania

|

750.00

|

1.07

|

805.69

|

133.75

|

129.57

|

|

Myanmar

|

1,478.16

|

0.52

|

764.32

|

24.51

|

38.41

|

|

India

|

1,800.00

|

0.42

|

751.32

|

325.91

|

415.20

|

|

Sudan

|

2,141.34

|

0.26

|

550.00

|

258.54

|

259.14

|

|

Nigeria

|

500.00

|

1.10

|

550.00

|

172.84

|

209.68

|

|

China

|

260.67

|

1.40

|

366.00

|

26.27

|

49.21

|

|

Ethiopia

|

293.65

|

0.79

|

231.19

|

382.05

|

383.59

|

|

Burkina Fuso

|

291.17

|

0.56

|

163.79

|

159.84

|

113.36

|

Note: Export data* are available for 2016

Source: FAOSTAT, 2018

.PNG)

Figure2. Major sesame cultivated regions in Myanmar

Source: DOA, 2018

Nearly 90% of the sesame were grown in the central dry zone of Myanmar: Magway, Mandalay and Sagaing Regions in 2017-2018 (Figure 2). Magway Region stood as the largest sesame sown area in Myanmar which was contributed about 520,190 ha (34%) of the national total area of sesame cultivation (Department of Agriculture [DOA], 2018). As shown in Table 2, the sown area of sesame in Myanmar was gradually increased from 1,338,000 ha in 2005-2006 to 1,590,000 ha in 2017-2018. Sown area, 1,640,000 ha and total production of sesame, 943,000 MT in 2015-2016 were the highest across a decade. Yield/ha of sesame was also increased from 0.40 MT/ha in 2005-2006 to 0.54 MT/ha in 2017-2018. Consequently, total production also increased because of expansion of area and improved yield. The clear trend of increasing sown area and total sesame production can be seen in 2015-2016 across a decade. The export volume was high in 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 then it gradually went down less than 100,000 MT during 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. Then, export of Myanmar sesame was increasing again and reached 120,990 MT in 2017-2018. Myanmar is still one of the largest sesame producers in the world, but after local consumptions, have been exported yearly. As being local diet, above 80% of the total production is consumed domestically as a garnish, snack, flavoring, and most importantly, as cooking oil (Aleksandar Jovanovic, 2018). Therefore, it can export less than 15% of the total production due to many constraints along sesame supply chain (MOALI, 2018). Generally, the main reasons for low productivity are heavy rain in planting time and harvest time that will reduce yield. During July 2017, heavy rain occurred 2 to 3 weeks before harvesting stage of monsoon sesame at the period of growing season, which will cause great yield losses in that year.

Table 2. Sown area, harvested area, yield, production and export status of sesame in Myanmar

|

Year

|

Sown area

(‘000 ha)

|

Harvested area

(‘000 ha)

|

Yield

(MT/ha)

|

Production

(‘000 MT)

|

Export *

|

|

Volume

(‘000 MT)

|

Value

(million US$)

|

|

2005-06

|

1,338

|

1,262

|

0.40

|

504

|

44.72

|

34.04

|

|

2010-11

|

1,585

|

1,584

|

0.54

|

862

|

79.70

|

114.35

|

|

2011-12

|

1,595

|

1,594

|

0.57

|

901

|

95.66

|

135.85

|

|

2012-13

|

1,553

|

1,552

|

0.56

|

863

|

135.95

|

235.73

|

|

2013-14

|

1,622

|

1,606

|

0.57

|

909

|

192.33

|

355.00

|

|

2014-15

|

1,581

|

1,572

|

0.59

|

930

|

91.07

|

180.89

|

|

2015-16

|

1,640

|

1,611

|

0.59

|

943

|

96.62

|

130.91

|

|

2016-17

|

1,636

|

1,610

|

0.58

|

927

|

108.72

|

146.78

|

|

2017-18

|

1,590

|

1,539

|

0.54

|

829

|

120.99

|

147.00

|

Note: Export data* are taken from MOC

Source: MOALI, 2018

China was the major sesame importing country from Myanmar and imported about 99,611.48 MT followed by Japan and Singapore which imported about 9,722.66 MT and 4,732.44 MT respectively. Taiwan and Thailand imported Myanmar sesame about 3,067.30 MT and 2,037.28 MT respectively. Myanmar also exported sesame to Denmark, Malaysia, Hong Kong, India, Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam and Australia. China and Japan accounted for 80% to 90% of the export destination of Myanmar sesame (Table 3).

Table 3. Trading partners of Myanmar sesame (2017-2018)

|

Countries

|

Export volume (MT)

|

Export value (Million US$)

|

|

China

|

99,611.48

|

117.29

|

|

Japan

|

9,722.66

|

15.26

|

|

Singapore

|

4,732.44

|

5.43

|

|

Taiwan

|

3,067.30

|

3.67

|

|

Thailand

|

2,037.28

|

2.56

|

|

Denmark

|

1,244.00

|

2.12

|

|

Malaysia

|

222.99

|

0.28

|

|

Hong Kong, China

|

203.70

|

0.27

|

|

India

|

114.00

|

0.07

|

|

Republic of Korea

|

18.00

|

0.03

|

|

Indonesia

|

18.00

|

0.02

|

|

Vietnam

|

5.00

|

0.00

|

|

Australia

|

2.52

|

0.00

|

|

Total

|

120,999.37

|

147.00

|

Source: MOC, 2018

Traditional production practices and weak linkages among stakeholders are major barriers to expand Myanmar’s export share in world market. In order to eliminate the production and marketing constraints the food safety criteria have also played an important role along Myanmar sesame supply chain. Pyitharyar contract farming scheme was launched in Aunglan Township, Magway Region since 2003. The contract company provided sesame seeds, capital, efficient pesticide spraying method and SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) demonstration to contract farmers and also purchased black sesame seeds which were exported to Toyota Tsusho Food Corporation and Kanematsu Corporation in Tokyo, Japan (Theingi Myint, Ei Mon Thida Kyaw, Ye Mon Aung & Aye Moe San, 2017). Currently, in Aunglan Township, Magway Region, informal contract farming system, which is basically composed of verbal agreements between local wholesalers and individual sesame farmers in providing seeds, credit, market information and purchase sesame seed by wholesalers is being practiced. This study was conducted to investigate cost and return of sesame farmers and to evaluate production and marketing activities including constraints under informal contract system and traditional one in Aunglan Township.

Research Methodology

Aunglan Township, Magway Region was selected as study area because of its wide sown areas of top export sesame variety named Sahmon Nat. Aside from this is the fact that the study area has been practicing the informal contract system. Purposive random sampling procedure was applied to gather primary data such as farm and household characteristics, socio-economic condition, production, marketing activities and constraints faced by sampled households. Within Aunglan Township, one village from five village tracts respectively were randomly chosen and total number of respondents were 102 farmers composed of 60 contract farmers and 42 independent farmers. Sampled respondents were individually interviewed with structured questionnaires during November and December 2017. Descriptive statistics, cost and return analysis were applied with STATA 14 statistical software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Socio-economic characteristics of sampled farm household heads

Demographic characteristics of sampled household heads producing sesame in the study area is shown in Table.4. The average age of contract farm household heads were 47.63 years and that of non-contract farm household heads were 49.24 years. The average experiences in farming for contract farmers were 25.25 years while that of non-contract farmers were 26.19 years. There was no significant difference in age and farming experience between contract and non-contract farm household heads in the study area. Both groups occupied secondary education levels, however, non-contract household heads had significant high schooling years which were 6.71 years in comparison with contract household heads which were 5.25 years.

Table 4. Demographic characteristics of sampled farm household heads in Aunglan Township

|

Items

(Year)

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

t-test

|

|

Avg. age

|

47.63 (29 - 72)

|

49.24 (32 - 74)

|

0.78ns

|

|

Avg. farming experience

|

25.25 (5 - 58)

|

26.19 (2 - 55)

|

0.38ns

|

|

Avg. schooling year

|

5.25 (2 - 14)

|

6.71 (2 - 14)

|

2.22**

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent range. *, ** and ***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Family size, agricultural labor, farm size, cultivated area and yield of sesame by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

The average family size of sampled farm households was composed of about 4 family members ranging from the smallest 2 to the highest 10 persons, in which, 2.28 and 2.36 family members of contract and non-contract households involved in agricultural activities. Average farm size was 7.23 ha for contract and 7.47 ha of non-contract farmers respectively. Average sown area of sesame was 3.49 ha for contract households ranging from 0.61 ha to 12.15 ha, while non-contract households owned 2.95 ha in average within the range of 0.20 ha to 16.19 ha. The average sesame yield was 266.26 kg/ha and 247 kg/ha respectively for contract and non-contract households. There were no significant differences in family size, agri-labors, farm size, sesame cultivated area and yield between contract and non-contract farmers as presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Family size, agricultural labors, farm size, cultivated area and yield of sesame by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

.PNG)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent range. *, ** and ***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Comparison of sampled households in the ownership of farm and livestock assets

Farm and livestock assets owned by sampled farm households in the study area are shown in Table 6. Sampled farm households owned more manual farm assets in comparison with farm machineries. All sampled contract and non-contract farm households possessed ploughs, harrows and bullock carts while less than 15% of sampled households had farm machineries such as tractors, power tillers and pulse splitting machine. In the context of livestock possession by sampled farm households, livestock rearing looked like a relatively small scale in the study area. However, nearly 100% of sampled farm households are owned cattle for farming activities. A few proportions of sampled farm households are composed of raised pig and poultry.

Table 6. Farm and livestock assets owned by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township (Unit = Frequency)

|

Items

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

|

Plough

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Harrow

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Bullock cart

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Sprayer

|

58 (96.67)

|

39 (92.86)

|

|

Generator

|

14 (23.33)

|

13 (30.95)

|

|

Thresher

|

8 (13.33)

|

9 (21.43)

|

|

Fodder cutting machine

|

6 (10.00)

|

6 (14.29)

|

|

Tractor

|

5 (8.33)

|

6 (14.29)

|

|

Power tiller

|

2 (3.33)

|

1 (2.38)

|

|

Pulse splitting machine

|

1 (1.67)

|

2 (4.76)

|

|

Htaw lar gyi (small truck)

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Inter-cultivator

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Cattle

|

59 (98.33)

|

41 (97.62)

|

|

Pig

|

7 (11.67)

|

2 (4.76)

|

|

Poultry

|

2 (3.33)

|

2 (4.76)

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage

Source of credit by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

As in Table 7, some sampled households received credit from only one source while other took from two credit sources and other had three sources. As one credit source, majorities of sampled contract households (38.33%) took seasonal agricultural credit from Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank (MADB) only, followed by township wholesalers, which was taken by 13.33% of sampled contract households. Meanwhile, about 45.24% of sampled non-contract households acquired credit from MADB only which was followed by credit taken from township wholesalers (2.38%). Less than 2% each of contract households took credit from agro-input dealers alone, cooperatives alone and money lender alone. Regarding with two sources of credit about 11.67% of contract households received credit from MADB and township wholesaler, while about 21.43% non-contract households took credit from MADB and cooperative.

Table 7. Source of credit by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

(Unit = Frequency)

|

Sources of credit

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

|

Access from one source

|

|

|

|

MADB

|

23 (38.33)

|

19 (45.24)

|

|

Township wholesaler

|

8 (13.33)

|

1 (2.38)

|

|

Agro-input dealer

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Cooperative

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Money lender

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Access from two sources

|

|

|

|

MADB and Cooperative

|

6 (10.00)

|

9 (21.43)

|

|

MADB and Township wholesaler

|

7 (11.67)

|

0.00

|

|

MADB and Money lender

|

0.00

|

3 (7.14)

|

|

MADB and Agro-input dealer

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Township wholesaler and Cooperative

|

2 (3.33)

|

0.00

|

|

Access from three sources

|

|

|

|

MADB, Agro-input dealer and Cooperative

|

3 (5.00)

|

7 (16.67)

|

|

MADB, Cooperative and

|

2 (3.33)

|

2 (4.76)

|

|

Money lender

|

|

|

|

MADB, Township wholesaler and Cooperative

|

3 (5.00)

|

0.00

|

|

Nil

|

2 (3.33)

|

1 (2.38)

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Access to production practices by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

Sampled farm households in the study area received information related to sesame production practices from different sources like Department of Agriculture (DOA) and agro-input (fertilizers, pesticides, foliar, plant growth hormone, etc.) dealers. Majority of both contract and non-contract households which were more than 50% of each group respectively got information about production practices in association with not only DOA but also agro-input dealers, as shown in Table 8. It can be assumed that non-contract households relied more on agro-input dealers for this information. Sampled farm households received information about production practices in different ways such as through the meeting, training or field demonstration. Contract households had more involvement in training, meeting and field demonstration as compared to non-contract households. About 81.67% and 78.57% of contract and non-contract households obtained sesame production practices by attending meeting. More than 50% of contract households and about 38% of non-contract households participated in training to get production practices while only 1.67% of contract households got production practices by exploring demonstration field.

Table 8. Access to production practices by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

|

Source of production practices

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract farmers (N=42)

|

|

Access from one source

|

|

|

|

DOA

|

18 (30.00)

|

4 (9.52)

|

|

Agro-input dealer

|

5 (8.33)

|

8 (19.05)

|

|

Access from two sources

|

|

|

|

DOA and Agro-input dealer

|

33 (55.00)

|

28(66.67)

|

|

Nil

|

4 (6.67)

|

2 (4.76)

|

|

Type of service received

|

|

|

|

Meeting

|

49 (81.67)

|

33 (78.57)

|

|

Training

|

35 (58.33)

|

16 (38.10)

|

|

Field demonstration

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Access to market information by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

In the study area, sampled farm households had different sources to get access to market information as shown in Table 9. Majority of contract households (55%) accepted market information mainly from township wholesalers while majority, almost (41%) of non-contract households jointly received market information from township wholesalers and neighboring farmers. It is evident that township wholesalers and their neighboring farmers were found to be the most reliable and accessible information sources for sesame farmers.

Table 9. Access to market information by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township (Unit = Frequency)

|

Sources

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

|

Access from one source

|

|

|

|

Township wholesaler

|

33 (55.00)

|

12 (28.57)

|

|

Neighboring farmer

|

5 (8.33)

|

12 (28.57)

|

|

Social media

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Access from two sources

|

|

|

|

Township wholesaler and

|

18 (30.00)

|

17 (40.48)

|

|

Neighboring farmer

|

|

|

|

Township wholesaler and

|

2 (3.33)

|

0.00

|

|

Social media

|

|

|

|

Neighboring farmer and

|

0.00

|

1 (2.38)

|

|

Social media

|

|

|

|

Access from three sources

|

|

|

|

Township wholesaler,

|

1 (1.67)

|

0.00

|

|

Neighboring farmer and

|

|

|

|

Social media

|

|

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Composition of annual household income by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

Different income sources which contributed to household income for sampled farm households were presented in Table 10. Annual household income was derived from crop income, non-farm income, livestock income and remittance income. Contract households obtained higher income than non-contract households (2,343,988 > 1,466,528 MMK per household per year). There were 18.33% and 26.19% of contract and non-contract households earned from livestock. About 16.67% and 35.71% of contract and non-contract households got income from non-farm. In addition, only 5% of contract and 4.76% of non-contract households who earned incomes from remittance. There was significantly different in crop incomes at 5% level and other incomes were not significantly different in both groups of farmers.

Table 10. Composition of annual household income by sampled farm households

|

Type of income

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract farmers (N=42)

|

t-test

|

|

No.

|

Avg. income

|

No.

|

Avg. income

|

|

Crop income

|

60 (100.00)

|

2,343,988

|

42 (100.00)

|

1,466,528

|

1.97**

|

|

Livestock income

|

11 (18.33)

|

115,500

|

11 (26.19)

|

345,000

|

1.90ns

|

|

Non-farm income

|

10 (16.67)

|

442,833

|

15 (35.71)

|

844,524

|

1.48ns

|

|

Remittance income

|

3 (5.00)

|

146,667

|

2 (4.76)

|

157,143

|

0.07ns

|

|

Total HH income

|

60 (100.00)

|

3,048,988

|

42 (100.00)

|

2,813,195

|

0.39 ns

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage, *, ** and***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Utilization of seeds, FYM and agrochemicals in monsoon sesame production by sampled farm households

Different amount of inputs used for sesame by sampled farm households in the study area as shown in Table 11. Sampled contract households used 6.09 kg/ha of seeds on average which was less than 6.48 kg/ha of non-contract farm households. Contract households applied FYM over 2 ton/ha while non-contract households applied less than 2 ton/ha. Contract households used compound fertilizer almost 50 kg/ha but non-contract farmers used less than 40 kg/ha for compound. The average rate of urea fertilizer used by contract and non-contract households were 21.98 kg/ha and 29.29 kg/ha respectively. The average rate of 19.90 kg/ha and 16.47 kg/ha of gypsum was applied by contract and non-contract households respectively. Average amount of fungicide was 0.09 kg/ha for contract and 0.02 kg/ha for non-contract households respectively. As overall, contract farmers utilized high dose of farm yard manure (FYM), compound fertilizer, gypsum and fungicide in comparison with non-contract farmers. The usages of urea fertilizer, foliar fertilizer and insecticide of non-contract farmers were a slightly higher than that of contract farmers in the study area.

Table 11. Amount of input used by sampled farm households in monsoon sesame production

|

Items

|

Units

|

Contract

farmers (N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

t-test

|

|

No.

|

Amount

|

No.

|

Amount

|

|

Seed

|

kg/ha

|

60

|

6.09

|

42

|

6.48

|

1.25ns

|

|

|

|

(100.00)

|

(3.78 - 11.34)

|

(100.00)

|

(3.78 - 7.56)

|

|

|

FYM

|

ton/ha

|

36

|

2.27

|

25

|

1.90

|

0.96ns

|

| |

|

(60.00)

|

(0 - 9.90)

|

(59.52)

|

(0 - 6.20)

|

|

|

Urea

|

kg/ha

|

31

|

21.98

|

25

|

29.29

|

1.20 ns

|

| |

|

(51.67)

|

(0 - 74.10)

|

(59.52)

|

(0 - 123.50)

|

|

|

Compound

|

kg/ha

|

51

|

48.93

|

29

|

36.17

|

0.89ns

|

| |

|

(85.00)

|

(0 - 123.50)

|

(69.05)

|

(0 - 123.50)

|

|

|

Gypsum

|

kg/ha

|

34

|

19.90

|

18

|

16.47

|

0.59ns

|

| |

|

(56.67)

|

(0 - 118.56)

|

(42.86)

|

(0 - 74.10)

|

|

|

Insecticide

|

liter/ha

|

48

|

0.38

|

33

|

0.47

|

1.83ns

|

| |

|

(80.00)

|

(0 - 1.24)

|

(78.57)

|

(0 - 1.24)

|

|

|

Fungicide

|

kg/ha

|

25

|

0.09

|

8

|

0.02

|

1.49*

|

| |

|

(41.67)

|

(0 - 0.62)

|

(19.05)

|

(0 - 0.49)

|

|

|

Herbicide

|

liter/ha

|

15

|

0.18

|

11

|

0.17

|

0.74ns

|

| |

|

(25.00)

|

(0 - 1.61)

|

(26.19)

|

(0 - 1.24)

|

|

|

Foliar

|

liter/ha

|

40

|

0.44

|

32

|

0.60

|

1.83ns

|

| |

|

(66.67)

|

(0 - 1.48)

|

(76.19)

|

(0 - 1.24)

|

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage and range. *, ** and***denote significant levels at 10%, 5%, 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Cost and return analysis of monsoon sesame production by sampled farm households

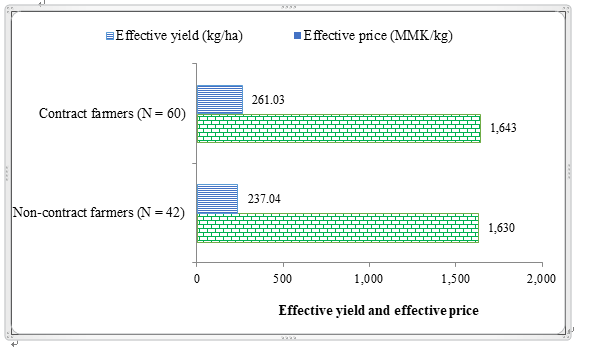

Cost and return analysis of monsoon sesame production was determined by enterprise budgeting. During 2017 monsoon season, effective yield of sesame (261.03 kg/ha and 237.04 kg/ha) and effective price (1,643 MMK/ha and 1,630 MMK/ha) were received by sampled contract and non-contract farm households respectively (Figure 3).

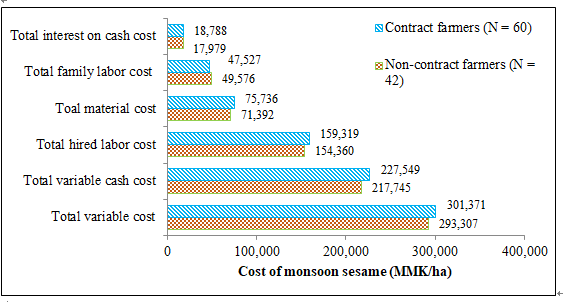

Contract farm households used high dose of agro-inputs such as FYM, compound fertilizer, gypsum and fungicide, thus, total material cost was slightly higher for contract farm households which was 75,736 MMK/ha as compared to that of non-contract farm households which was 71,392 MMK/ha. Total family labor cost for non-contract farm households was 49,576 MMK/ha while contract farm households spent 47,527 MMK/ha for family labor as opportunity cost. The hired labor cost for contract and non-contract farm households were 159,319 MMK/ha and 154,360 MMK/ha, respectively. Total variable cost per hectare of monsoon sesame was 301,371 MMK/ha for contract farm households and 293,307 MMK/ha for non-contract farm households respectively. Thus, total variable cost was higher in contract as compared to non-contract farm households. It was due to higher cost on some inputs and hired labor spent by contract farm households. Total interest on cash cost for contract and non-contract households were 18,788 MMK/ha and 17,979 MMK/ha, respectively. Total variable cash cost per hectare of monsoon sesame was 227,549 MMK/ha for contract households and 217,745 MMK/ha for non-contract households in the study area (Figure 4).

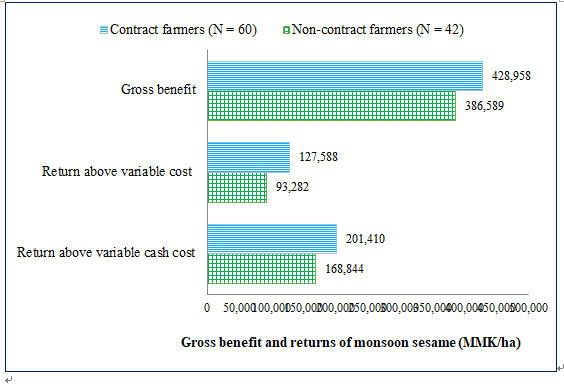

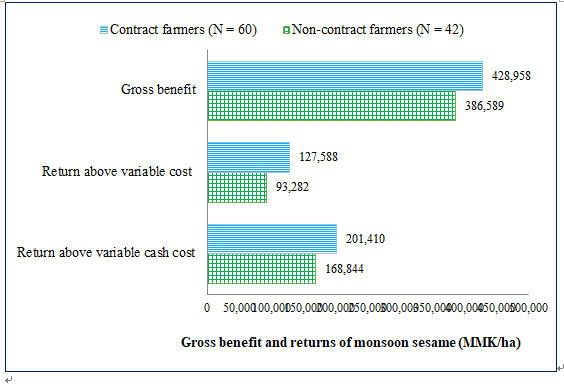

Total gross benefit was calculated by multiplying effective yields and prices received by both contract and non-contract farm households respectively. Total gross benefit was about 428,958 MMK/ha for contract farmers while that for non-contract households was 386,589 MMK/ha. Return above variable costs (RAVC) for contract and non-contract households were 127,588 MMK/ha and 93,282 MMK/ha respectively. In addition, return above variable cash costs (RAVCC) were 201,410 MMK/ha for contract households and 168,844 MMK/ha for non-contract households. Due to higher effective yield and price received by contract households as compared to non-contract households, contract households achieved higher gross benefit, returns above variable cost and variable cash costs, although they paid higher production cost (Figure 5).

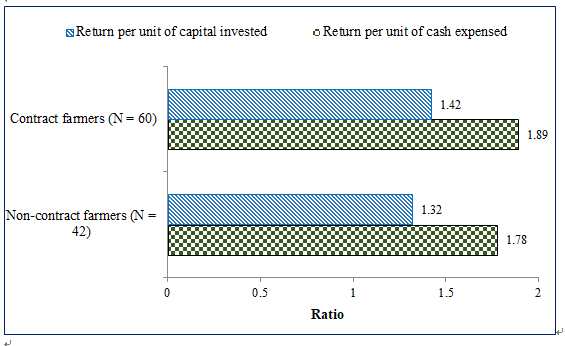

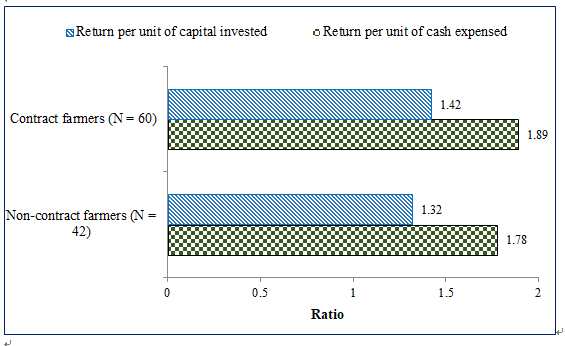

Return per unit of cash expenses was 1.89 for contract households while that of for non-contract households was 1.78. Return per unit of invested capital or benefit cost ratio were 1.42

and 1.32 for contract and non-contract households respectively (Figure 6).

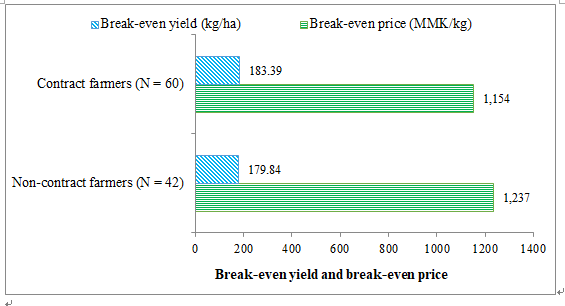

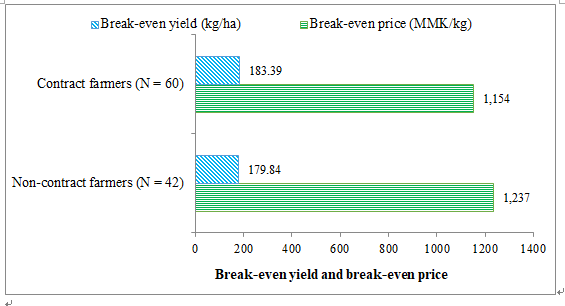

The break-even yield of contract and non-contract farm households were 183.39 kg/ha and 179.84 kg/ha respectively. Similarly, contract and non-contract farm households can get benefit over their total production costs when they started to get sesame price 1,154 MMK/kg and 1,237 MMK/kg at the current yield, respectively (Figure 7). The results revealed that break-even yield of contract farm households was slightly higher than non-contract farm households in order to cover their production cost for monsoon sesame per hectare in the study area.

Figure 3. Effective yield and price of monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Figure 4. Cost of monsoon sesame production per hectare of sampled farm households

Figure 5. Returns of monsoon sesame production per hectare by sampled farm households

Figure 6. Returns per unit of cash and capital invested in monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Figure 7. Break-even yield and price of monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Marketing activities of sampled farm households

Marketing activities of sampled farm households included purchasing, selling, grading, weighing, and transportation activities. About 98% of sampled contract households directly sold raw sesame (in kind) to connected wholesaler while the remaining contract households sold raw sesame to open market and repaid in cash to connect wholesalers. All non-contract households sold to normal (unconnected) wholesalers in open market. Majority of sampled farm households (98.04%) sold raw sesame seed immediately after harvest and only less than 2% of sampled farm households sold out their commodity within one month by using cash down system. In the study area, none of sampled households used grading system before selling and their weighing measurement in selling was one basket equals 15 viss. (Table 12). There is no well-sound grading system to classifying and categorizing raw sesame seed, only depends on the colors of the sesame and among the cultivated strains of Black, White, Red and Brown sesame.

The modes of transportation used by sampled farm households were shown in Table 13. There were two kinds of transportation and most of farmers used light truck when selling the product. About 80% of sampled contract households and 54.76% of sampled non-contract households used light truck in the study area. In addition, 20% of contract farm households and 45.24% of non-contract farm households also used tricycle. About 95% of contract farm households and 92.86% of non-contract farm households sold to wholesalers in Aunglan and only 5% of contract farm households and 7.14% of non-contract farm households sold to wholesalers in Pyalo as presented in Table14.

General constraints for production and marketing of sampled farm households

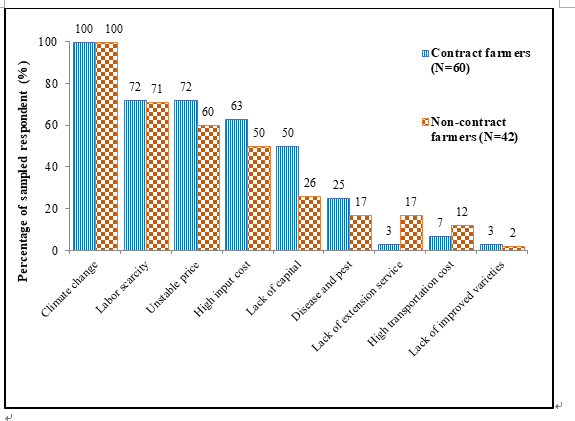

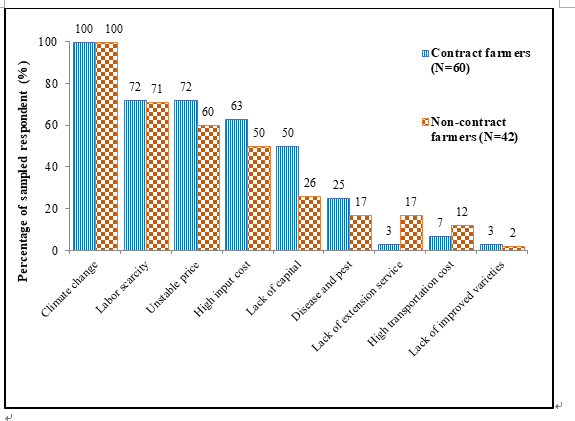

All sampled farm households answered that they suffered climate change as a major constraint in the study area because erratic rainfall and unfavorable temperature during monsoon season reduced sesame yield. Moreover, the common constraints faced by sampled farm households in the study area were labor scarcity, unstable price, high input cost, lack of capital, incidence of disease and pest, lack of extension service, high transportation cost and lack of improved varieties. These major constraints limited to farmers by reducing yield and earning less income (Figure 8).

Table 12. Selling information of sampled farm households (Unit= Number)

|

Main buyers of sesame

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

|

|

Sold to

|

|

|

|

Connected wholesaler

|

59 (98.33)

|

-

|

|

Normal wholesaler in open market

|

1 (1.67)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Product selling time

|

|

|

|

Immediately after harvest

|

59 (98.33)

|

41 (97.62)

|

|

Within one month

|

1 (1.67)

|

1 (2.38)

|

|

Product selling form

|

|

|

|

Raw

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Type of selling

|

|

|

|

Cash down

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Use of grading method in selling

|

|

|

|

No

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

|

Weighing measurement in selling

|

|

|

|

1 Basket = 15 viss

|

60 (100.00)

|

42 (100.00)

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Table 13. Mode of transportation to the market by sampled farm households

|

Mode of

transportation

|

Unit

|

Contract

farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract

farmers

(N=42)

|

Total

(N=102)

|

|

By light truck

|

No.

|

48 (80.00)

|

23 (54.76)

|

71 (69.61)

|

|

By tricycle

|

No.

|

12 (20.00)

|

19 (45.24)

|

30 (30.39)

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Table 14. Market destinations of sampled farm households

|

Market

|

Contract farmers

(N=60)

|

Non-contract farmers

(N=42)

|

Total

(N=102)

|

|

Aunglan

|

57 (95.00)

|

39 (92.86)

|

96 (94.12)

|

|

Pyalo

|

3 (5.00)

|

3 (7.14)

|

6 (5.88)

|

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Figure 8. Constraints in sesame production and marketing by sampled farm households in the study area

CONCLUSION

Contract farming can ensure year-round supply of sesame raw material at the required quantity and quality while ensuring sustainable market for farmers at a better price. Production cost of sesame by contract households was relatively higher than non-contract households due to their higher usage of material inputs (agro-inputs) and hired labor cost especially in harvesting stages and fertilization and pesticide application. Performance of contract households was better than that of non-contract households in the study area although contract scheme was not well structured and systematically comprehensive arranged between stakeholders in current situation. Limited access to credit by stakeholders led inadequacy of capital investment in sesame supply chain. Therefore, financial aid and credit access should be explored for enabling long term and short-term assistance from collaborating government and institutional lending agencies in order to eliminate the problem of inadequate capital among the sesame farmers. Provision of market information is very important for sesame market development to generate better income for stakeholders.

RECOMMENDATION

Farmers should pay attention to improve quality of sesame in order to get market share in not only domestic but also international market by overcoming current constraints. A deliberate policy on sesame market and development should be formulated to remove market distortions and promote market efficiency in terms of quality control, stable supply of product and reduced-price fluctuation in the system. Although there were many difficulties in contract farming, technical advice and other services should be provided to farmers by governmental institutions and private companies or NGOs jointly. Finally, in order to fulfill the requirement of domestic consumption and to achieve the export earnings, intensification of sesame production should be raised improved technology as well as improving contract farming along the supply chain.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture. (2018). Annual Report of Department of Agriculture (DOA), Nay Pyi Taw, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Aleksandar Jovanovic. (2018). Myanmar Product Profile: Sesame seeds, Myanmar – EU Trade Helpdesk. Retrieved from https://www.myantrade.org/files/2018/9/5b95304a6ba2c 3.37436639.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/faostat/

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. (2018). Myanmar Agriculture Sector in Brief, Department of Planning, Nay Pyi Taw. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Ministry of Commerce. (2018). Nay Pyi Taw, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Theingi Myint, Ei Mon Thida Kyaw, Ye Mon Aung and Aye Moe San. (2017). Assessment of Sesame Supply Chain Management in Magway Region, Myanmar. JICA-TCP project report, Yezin Agricultural University.

Date submitted: October 30, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: December 2, 2019 |

Production and Marketing Activities of Sesame Farmers under Informal Contract System in Aunglan Township, Magway Region

ABSTRACT

Sesame is mainly grown in the central dry zone of Myanmar, in which, Magway Region occupied the largest sesame sown area for many years. Informal contract agreement among sesame farmers and buyers are practiced in Aunglan Township, Magway Region. This study aimed to understand the production and marketing performances of sesame farmers under contract and non-contract systems in the study area. By using purposive random sampling procedure, a total of 102 sesame farmers in Aunglan Township were interviewed by using structured questionnaires during November and December, 2017. These findings indicated that contract farmers were younger and had less farming experiences as compared to non-contract farmers. Contract farmers received credit and market information from more diverse sources and more participated in training, meeting and field demonstration which were mostly related to sesame production practices in comparison with non-contract farmers. Production cost of sesame by contract farmers was higher as compared to non-contract farmers due to their higher usage of FYM, compound fertilizers, gypsum and fungicide. However, it did not affect their returns because contract farmers received better sesame yield in comparison with non-contract farmers. Climate change, labor scarcity, unstable price and high input cost were major constraints for rain-fed dependent sesame farmers. There was still lack of advanced technology in quality checking, grading, thus, technology investment is crucially needed for producing good quality seeds. Sesame farmers should pay attention not only to quality improvement but also to overcoming current constraints along the supply chain in order to maintain global export share of Myanmar sesame.

Keywords: Sesame, supply chain, contract, Magway region, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Oilseeds, being the third most important crop group after cereal and pulses in Myanmar agriculture, covered nearly 8.2 million acres of the total crop sown area. There are many kinds of oilseed crops such as groundnut, sesame, sunflower, mustard and niger. The most extensive and traditional oilseed crop is sesame and it occupies the largest sown area (approximately 48.83% of total oilseed crop areas), followed by the groundnut 31.79% of total oilseed crop areas in 2017-2018 as shown in Figure 1 (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018).

Myanmar produced the second highest sesame production (764,320 MT) in the world after Tanzania, with a sesame yield of 0.52 MT/ha in 2017 as shown in Table 1. It can be observed that high yield group (Tanzania, Nigeria, and China) achieved sesame yield above 1 MT/ha while low yield group (Myanmar, India, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Burkina Fuso) obtained round about 0.5 MT/ha only on average. Myanmar occupied 13.81% of the total world production and 34.81% of Asia. In the world’s sesame export, Myanmar occupied 1.29% of the total world’s export and 1.86% of the total world’s sesame export earnings in 2016 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistics [FAOSTAT], 2018).

Figure 1. Shares of sown area for oilseed crops in Myanmar during 2017-2018

Source: MOALI, 2018

Table1. Harvested area, yield, production and export status of sesame by top eight global sesame producing countries in 2017

Countries

Harvested area

('000 ha)

Average yield (MT/ha)

Production ('000 MT)

Export *

Volume

('000 MT)

Value

(Million US$)

World

9,983.17

0.55

5,531.95

1,895.58

2,069.27

Asia

3,952.06

0.56

2,195.09

460.94

610.41

Tanzania

750.00

1.07

805.69

133.75

129.57

Myanmar

1,478.16

0.52

764.32

24.51

38.41

India

1,800.00

0.42

751.32

325.91

415.20

Sudan

2,141.34

0.26

550.00

258.54

259.14

Nigeria

500.00

1.10

550.00

172.84

209.68

China

260.67

1.40

366.00

26.27

49.21

Ethiopia

293.65

0.79

231.19

382.05

383.59

Burkina Fuso

291.17

0.56

163.79

159.84

113.36

Note: Export data* are available for 2016

Source: FAOSTAT, 2018

Figure2. Major sesame cultivated regions in Myanmar

Source: DOA, 2018

Nearly 90% of the sesame were grown in the central dry zone of Myanmar: Magway, Mandalay and Sagaing Regions in 2017-2018 (Figure 2). Magway Region stood as the largest sesame sown area in Myanmar which was contributed about 520,190 ha (34%) of the national total area of sesame cultivation (Department of Agriculture [DOA], 2018). As shown in Table 2, the sown area of sesame in Myanmar was gradually increased from 1,338,000 ha in 2005-2006 to 1,590,000 ha in 2017-2018. Sown area, 1,640,000 ha and total production of sesame, 943,000 MT in 2015-2016 were the highest across a decade. Yield/ha of sesame was also increased from 0.40 MT/ha in 2005-2006 to 0.54 MT/ha in 2017-2018. Consequently, total production also increased because of expansion of area and improved yield. The clear trend of increasing sown area and total sesame production can be seen in 2015-2016 across a decade. The export volume was high in 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 then it gradually went down less than 100,000 MT during 2014-2015 and 2015-2016. Then, export of Myanmar sesame was increasing again and reached 120,990 MT in 2017-2018. Myanmar is still one of the largest sesame producers in the world, but after local consumptions, have been exported yearly. As being local diet, above 80% of the total production is consumed domestically as a garnish, snack, flavoring, and most importantly, as cooking oil (Aleksandar Jovanovic, 2018). Therefore, it can export less than 15% of the total production due to many constraints along sesame supply chain (MOALI, 2018). Generally, the main reasons for low productivity are heavy rain in planting time and harvest time that will reduce yield. During July 2017, heavy rain occurred 2 to 3 weeks before harvesting stage of monsoon sesame at the period of growing season, which will cause great yield losses in that year.

Table 2. Sown area, harvested area, yield, production and export status of sesame in Myanmar

Year

Sown area

(‘000 ha)

Harvested area

(‘000 ha)

Yield

(MT/ha)

Production

(‘000 MT)

Export *

Volume

(‘000 MT)

Value

(million US$)

2005-06

1,338

1,262

0.40

504

44.72

34.04

2010-11

1,585

1,584

0.54

862

79.70

114.35

2011-12

1,595

1,594

0.57

901

95.66

135.85

2012-13

1,553

1,552

0.56

863

135.95

235.73

2013-14

1,622

1,606

0.57

909

192.33

355.00

2014-15

1,581

1,572

0.59

930

91.07

180.89

2015-16

1,640

1,611

0.59

943

96.62

130.91

2016-17

1,636

1,610

0.58

927

108.72

146.78

2017-18

1,590

1,539

0.54

829

120.99

147.00

Note: Export data* are taken from MOC

Source: MOALI, 2018

China was the major sesame importing country from Myanmar and imported about 99,611.48 MT followed by Japan and Singapore which imported about 9,722.66 MT and 4,732.44 MT respectively. Taiwan and Thailand imported Myanmar sesame about 3,067.30 MT and 2,037.28 MT respectively. Myanmar also exported sesame to Denmark, Malaysia, Hong Kong, India, Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam and Australia. China and Japan accounted for 80% to 90% of the export destination of Myanmar sesame (Table 3).

Table 3. Trading partners of Myanmar sesame (2017-2018)

Countries

Export volume (MT)

Export value (Million US$)

China

99,611.48

117.29

Japan

9,722.66

15.26

Singapore

4,732.44

5.43

Taiwan

3,067.30

3.67

Thailand

2,037.28

2.56

Denmark

1,244.00

2.12

Malaysia

222.99

0.28

Hong Kong, China

203.70

0.27

India

114.00

0.07

Republic of Korea

18.00

0.03

Indonesia

18.00

0.02

Vietnam

5.00

0.00

Australia

2.52

0.00

Total

120,999.37

147.00

Source: MOC, 2018

Traditional production practices and weak linkages among stakeholders are major barriers to expand Myanmar’s export share in world market. In order to eliminate the production and marketing constraints the food safety criteria have also played an important role along Myanmar sesame supply chain. Pyitharyar contract farming scheme was launched in Aunglan Township, Magway Region since 2003. The contract company provided sesame seeds, capital, efficient pesticide spraying method and SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) demonstration to contract farmers and also purchased black sesame seeds which were exported to Toyota Tsusho Food Corporation and Kanematsu Corporation in Tokyo, Japan (Theingi Myint, Ei Mon Thida Kyaw, Ye Mon Aung & Aye Moe San, 2017). Currently, in Aunglan Township, Magway Region, informal contract farming system, which is basically composed of verbal agreements between local wholesalers and individual sesame farmers in providing seeds, credit, market information and purchase sesame seed by wholesalers is being practiced. This study was conducted to investigate cost and return of sesame farmers and to evaluate production and marketing activities including constraints under informal contract system and traditional one in Aunglan Township.

Research Methodology

Aunglan Township, Magway Region was selected as study area because of its wide sown areas of top export sesame variety named Sahmon Nat. Aside from this is the fact that the study area has been practicing the informal contract system. Purposive random sampling procedure was applied to gather primary data such as farm and household characteristics, socio-economic condition, production, marketing activities and constraints faced by sampled households. Within Aunglan Township, one village from five village tracts respectively were randomly chosen and total number of respondents were 102 farmers composed of 60 contract farmers and 42 independent farmers. Sampled respondents were individually interviewed with structured questionnaires during November and December 2017. Descriptive statistics, cost and return analysis were applied with STATA 14 statistical software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Socio-economic characteristics of sampled farm household heads

Demographic characteristics of sampled household heads producing sesame in the study area is shown in Table.4. The average age of contract farm household heads were 47.63 years and that of non-contract farm household heads were 49.24 years. The average experiences in farming for contract farmers were 25.25 years while that of non-contract farmers were 26.19 years. There was no significant difference in age and farming experience between contract and non-contract farm household heads in the study area. Both groups occupied secondary education levels, however, non-contract household heads had significant high schooling years which were 6.71 years in comparison with contract household heads which were 5.25 years.

Table 4. Demographic characteristics of sampled farm household heads in Aunglan Township

Items

(Year)

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

t-test

Avg. age

47.63 (29 - 72)

49.24 (32 - 74)

0.78ns

Avg. farming experience

25.25 (5 - 58)

26.19 (2 - 55)

0.38ns

Avg. schooling year

5.25 (2 - 14)

6.71 (2 - 14)

2.22**

Note: The values in the parentheses represent range. *, ** and ***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Family size, agricultural labor, farm size, cultivated area and yield of sesame by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

The average family size of sampled farm households was composed of about 4 family members ranging from the smallest 2 to the highest 10 persons, in which, 2.28 and 2.36 family members of contract and non-contract households involved in agricultural activities. Average farm size was 7.23 ha for contract and 7.47 ha of non-contract farmers respectively. Average sown area of sesame was 3.49 ha for contract households ranging from 0.61 ha to 12.15 ha, while non-contract households owned 2.95 ha in average within the range of 0.20 ha to 16.19 ha. The average sesame yield was 266.26 kg/ha and 247 kg/ha respectively for contract and non-contract households. There were no significant differences in family size, agri-labors, farm size, sesame cultivated area and yield between contract and non-contract farmers as presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Family size, agricultural labors, farm size, cultivated area and yield of sesame by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

.PNG)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent range. *, ** and ***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Comparison of sampled households in the ownership of farm and livestock assets

Farm and livestock assets owned by sampled farm households in the study area are shown in Table 6. Sampled farm households owned more manual farm assets in comparison with farm machineries. All sampled contract and non-contract farm households possessed ploughs, harrows and bullock carts while less than 15% of sampled households had farm machineries such as tractors, power tillers and pulse splitting machine. In the context of livestock possession by sampled farm households, livestock rearing looked like a relatively small scale in the study area. However, nearly 100% of sampled farm households are owned cattle for farming activities. A few proportions of sampled farm households are composed of raised pig and poultry.

Table 6. Farm and livestock assets owned by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township (Unit = Frequency)

Items

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

Plough

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Harrow

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Bullock cart

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Sprayer

58 (96.67)

39 (92.86)

Generator

14 (23.33)

13 (30.95)

Thresher

8 (13.33)

9 (21.43)

Fodder cutting machine

6 (10.00)

6 (14.29)

Tractor

5 (8.33)

6 (14.29)

Power tiller

2 (3.33)

1 (2.38)

Pulse splitting machine

1 (1.67)

2 (4.76)

Htaw lar gyi (small truck)

1 (1.67)

0.00

Inter-cultivator

1 (1.67)

0.00

Cattle

59 (98.33)

41 (97.62)

Pig

7 (11.67)

2 (4.76)

Poultry

2 (3.33)

2 (4.76)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage

Source of credit by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

As in Table 7, some sampled households received credit from only one source while other took from two credit sources and other had three sources. As one credit source, majorities of sampled contract households (38.33%) took seasonal agricultural credit from Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank (MADB) only, followed by township wholesalers, which was taken by 13.33% of sampled contract households. Meanwhile, about 45.24% of sampled non-contract households acquired credit from MADB only which was followed by credit taken from township wholesalers (2.38%). Less than 2% each of contract households took credit from agro-input dealers alone, cooperatives alone and money lender alone. Regarding with two sources of credit about 11.67% of contract households received credit from MADB and township wholesaler, while about 21.43% non-contract households took credit from MADB and cooperative.

Table 7. Source of credit by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

(Unit = Frequency)

Sources of credit

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

Access from one source

MADB

23 (38.33)

19 (45.24)

Township wholesaler

8 (13.33)

1 (2.38)

Agro-input dealer

1 (1.67)

0.00

Cooperative

1 (1.67)

0.00

Money lender

1 (1.67)

0.00

Access from two sources

MADB and Cooperative

6 (10.00)

9 (21.43)

MADB and Township wholesaler

7 (11.67)

0.00

MADB and Money lender

0.00

3 (7.14)

MADB and Agro-input dealer

1 (1.67)

0.00

Township wholesaler and Cooperative

2 (3.33)

0.00

Access from three sources

MADB, Agro-input dealer and Cooperative

3 (5.00)

7 (16.67)

MADB, Cooperative and

2 (3.33)

2 (4.76)

Money lender

MADB, Township wholesaler and Cooperative

3 (5.00)

0.00

Nil

2 (3.33)

1 (2.38)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Access to production practices by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

Sampled farm households in the study area received information related to sesame production practices from different sources like Department of Agriculture (DOA) and agro-input (fertilizers, pesticides, foliar, plant growth hormone, etc.) dealers. Majority of both contract and non-contract households which were more than 50% of each group respectively got information about production practices in association with not only DOA but also agro-input dealers, as shown in Table 8. It can be assumed that non-contract households relied more on agro-input dealers for this information. Sampled farm households received information about production practices in different ways such as through the meeting, training or field demonstration. Contract households had more involvement in training, meeting and field demonstration as compared to non-contract households. About 81.67% and 78.57% of contract and non-contract households obtained sesame production practices by attending meeting. More than 50% of contract households and about 38% of non-contract households participated in training to get production practices while only 1.67% of contract households got production practices by exploring demonstration field.

Table 8. Access to production practices by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

Source of production practices

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract farmers (N=42)

Access from one source

DOA

18 (30.00)

4 (9.52)

Agro-input dealer

5 (8.33)

8 (19.05)

Access from two sources

DOA and Agro-input dealer

33 (55.00)

28(66.67)

Nil

4 (6.67)

2 (4.76)

Type of service received

Meeting

49 (81.67)

33 (78.57)

Training

35 (58.33)

16 (38.10)

Field demonstration

1 (1.67)

0.00

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Access to market information by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

In the study area, sampled farm households had different sources to get access to market information as shown in Table 9. Majority of contract households (55%) accepted market information mainly from township wholesalers while majority, almost (41%) of non-contract households jointly received market information from township wholesalers and neighboring farmers. It is evident that township wholesalers and their neighboring farmers were found to be the most reliable and accessible information sources for sesame farmers.

Table 9. Access to market information by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township (Unit = Frequency)

Sources

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

Access from one source

Township wholesaler

33 (55.00)

12 (28.57)

Neighboring farmer

5 (8.33)

12 (28.57)

Social media

1 (1.67)

0.00

Access from two sources

Township wholesaler and

18 (30.00)

17 (40.48)

Neighboring farmer

Township wholesaler and

2 (3.33)

0.00

Social media

Neighboring farmer and

0.00

1 (2.38)

Social media

Access from three sources

Township wholesaler,

1 (1.67)

0.00

Neighboring farmer and

Social media

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Composition of annual household income by sampled farm households in Aunglan Township

Different income sources which contributed to household income for sampled farm households were presented in Table 10. Annual household income was derived from crop income, non-farm income, livestock income and remittance income. Contract households obtained higher income than non-contract households (2,343,988 > 1,466,528 MMK per household per year). There were 18.33% and 26.19% of contract and non-contract households earned from livestock. About 16.67% and 35.71% of contract and non-contract households got income from non-farm. In addition, only 5% of contract and 4.76% of non-contract households who earned incomes from remittance. There was significantly different in crop incomes at 5% level and other incomes were not significantly different in both groups of farmers.

Table 10. Composition of annual household income by sampled farm households

Type of income

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract farmers (N=42)

t-test

No.

Avg. income

No.

Avg. income

Crop income

60 (100.00)

2,343,988

42 (100.00)

1,466,528

1.97**

Livestock income

11 (18.33)

115,500

11 (26.19)

345,000

1.90ns

Non-farm income

10 (16.67)

442,833

15 (35.71)

844,524

1.48ns

Remittance income

3 (5.00)

146,667

2 (4.76)

157,143

0.07ns

Total HH income

60 (100.00)

3,048,988

42 (100.00)

2,813,195

0.39 ns

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage, *, ** and***are significant at 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Utilization of seeds, FYM and agrochemicals in monsoon sesame production by sampled farm households

Different amount of inputs used for sesame by sampled farm households in the study area as shown in Table 11. Sampled contract households used 6.09 kg/ha of seeds on average which was less than 6.48 kg/ha of non-contract farm households. Contract households applied FYM over 2 ton/ha while non-contract households applied less than 2 ton/ha. Contract households used compound fertilizer almost 50 kg/ha but non-contract farmers used less than 40 kg/ha for compound. The average rate of urea fertilizer used by contract and non-contract households were 21.98 kg/ha and 29.29 kg/ha respectively. The average rate of 19.90 kg/ha and 16.47 kg/ha of gypsum was applied by contract and non-contract households respectively. Average amount of fungicide was 0.09 kg/ha for contract and 0.02 kg/ha for non-contract households respectively. As overall, contract farmers utilized high dose of farm yard manure (FYM), compound fertilizer, gypsum and fungicide in comparison with non-contract farmers. The usages of urea fertilizer, foliar fertilizer and insecticide of non-contract farmers were a slightly higher than that of contract farmers in the study area.

Table 11. Amount of input used by sampled farm households in monsoon sesame production

Items

Units

Contract

farmers (N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

t-test

No.

Amount

No.

Amount

Seed

kg/ha

60

6.09

42

6.48

1.25ns

(100.00)

(3.78 - 11.34)

(100.00)

(3.78 - 7.56)

FYM

ton/ha

36

2.27

25

1.90

0.96ns

(60.00)

(0 - 9.90)

(59.52)

(0 - 6.20)

Urea

kg/ha

31

21.98

25

29.29

1.20 ns

(51.67)

(0 - 74.10)

(59.52)

(0 - 123.50)

Compound

kg/ha

51

48.93

29

36.17

0.89ns

(85.00)

(0 - 123.50)

(69.05)

(0 - 123.50)

Gypsum

kg/ha

34

19.90

18

16.47

0.59ns

(56.67)

(0 - 118.56)

(42.86)

(0 - 74.10)

Insecticide

liter/ha

48

0.38

33

0.47

1.83ns

(80.00)

(0 - 1.24)

(78.57)

(0 - 1.24)

Fungicide

kg/ha

25

0.09

8

0.02

1.49*

(41.67)

(0 - 0.62)

(19.05)

(0 - 0.49)

Herbicide

liter/ha

15

0.18

11

0.17

0.74ns

(25.00)

(0 - 1.61)

(26.19)

(0 - 1.24)

Foliar

liter/ha

40

0.44

32

0.60

1.83ns

(66.67)

(0 - 1.48)

(76.19)

(0 - 1.24)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage and range. *, ** and***denote significant levels at 10%, 5%, 1% level respectively, ns is not significant differences.

Cost and return analysis of monsoon sesame production by sampled farm households

Cost and return analysis of monsoon sesame production was determined by enterprise budgeting. During 2017 monsoon season, effective yield of sesame (261.03 kg/ha and 237.04 kg/ha) and effective price (1,643 MMK/ha and 1,630 MMK/ha) were received by sampled contract and non-contract farm households respectively (Figure 3).

Contract farm households used high dose of agro-inputs such as FYM, compound fertilizer, gypsum and fungicide, thus, total material cost was slightly higher for contract farm households which was 75,736 MMK/ha as compared to that of non-contract farm households which was 71,392 MMK/ha. Total family labor cost for non-contract farm households was 49,576 MMK/ha while contract farm households spent 47,527 MMK/ha for family labor as opportunity cost. The hired labor cost for contract and non-contract farm households were 159,319 MMK/ha and 154,360 MMK/ha, respectively. Total variable cost per hectare of monsoon sesame was 301,371 MMK/ha for contract farm households and 293,307 MMK/ha for non-contract farm households respectively. Thus, total variable cost was higher in contract as compared to non-contract farm households. It was due to higher cost on some inputs and hired labor spent by contract farm households. Total interest on cash cost for contract and non-contract households were 18,788 MMK/ha and 17,979 MMK/ha, respectively. Total variable cash cost per hectare of monsoon sesame was 227,549 MMK/ha for contract households and 217,745 MMK/ha for non-contract households in the study area (Figure 4).

Total gross benefit was calculated by multiplying effective yields and prices received by both contract and non-contract farm households respectively. Total gross benefit was about 428,958 MMK/ha for contract farmers while that for non-contract households was 386,589 MMK/ha. Return above variable costs (RAVC) for contract and non-contract households were 127,588 MMK/ha and 93,282 MMK/ha respectively. In addition, return above variable cash costs (RAVCC) were 201,410 MMK/ha for contract households and 168,844 MMK/ha for non-contract households. Due to higher effective yield and price received by contract households as compared to non-contract households, contract households achieved higher gross benefit, returns above variable cost and variable cash costs, although they paid higher production cost (Figure 5).

Return per unit of cash expenses was 1.89 for contract households while that of for non-contract households was 1.78. Return per unit of invested capital or benefit cost ratio were 1.42

and 1.32 for contract and non-contract households respectively (Figure 6).

The break-even yield of contract and non-contract farm households were 183.39 kg/ha and 179.84 kg/ha respectively. Similarly, contract and non-contract farm households can get benefit over their total production costs when they started to get sesame price 1,154 MMK/kg and 1,237 MMK/kg at the current yield, respectively (Figure 7). The results revealed that break-even yield of contract farm households was slightly higher than non-contract farm households in order to cover their production cost for monsoon sesame per hectare in the study area.

Figure 3. Effective yield and price of monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Figure 4. Cost of monsoon sesame production per hectare of sampled farm households

Figure 5. Returns of monsoon sesame production per hectare by sampled farm households

Figure 6. Returns per unit of cash and capital invested in monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Figure 7. Break-even yield and price of monsoon sesame production of sampled farm households

Marketing activities of sampled farm households

Marketing activities of sampled farm households included purchasing, selling, grading, weighing, and transportation activities. About 98% of sampled contract households directly sold raw sesame (in kind) to connected wholesaler while the remaining contract households sold raw sesame to open market and repaid in cash to connect wholesalers. All non-contract households sold to normal (unconnected) wholesalers in open market. Majority of sampled farm households (98.04%) sold raw sesame seed immediately after harvest and only less than 2% of sampled farm households sold out their commodity within one month by using cash down system. In the study area, none of sampled households used grading system before selling and their weighing measurement in selling was one basket equals 15 viss. (Table 12). There is no well-sound grading system to classifying and categorizing raw sesame seed, only depends on the colors of the sesame and among the cultivated strains of Black, White, Red and Brown sesame.

The modes of transportation used by sampled farm households were shown in Table 13. There were two kinds of transportation and most of farmers used light truck when selling the product. About 80% of sampled contract households and 54.76% of sampled non-contract households used light truck in the study area. In addition, 20% of contract farm households and 45.24% of non-contract farm households also used tricycle. About 95% of contract farm households and 92.86% of non-contract farm households sold to wholesalers in Aunglan and only 5% of contract farm households and 7.14% of non-contract farm households sold to wholesalers in Pyalo as presented in Table14.

General constraints for production and marketing of sampled farm households

All sampled farm households answered that they suffered climate change as a major constraint in the study area because erratic rainfall and unfavorable temperature during monsoon season reduced sesame yield. Moreover, the common constraints faced by sampled farm households in the study area were labor scarcity, unstable price, high input cost, lack of capital, incidence of disease and pest, lack of extension service, high transportation cost and lack of improved varieties. These major constraints limited to farmers by reducing yield and earning less income (Figure 8).

Table 12. Selling information of sampled farm households (Unit= Number)

Main buyers of sesame

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers (N=42)

Sold to

Connected wholesaler

59 (98.33)

-

Normal wholesaler in open market

1 (1.67)

42 (100.00)

Product selling time

Immediately after harvest

59 (98.33)

41 (97.62)

Within one month

1 (1.67)

1 (2.38)

Product selling form

Raw

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Type of selling

Cash down

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Use of grading method in selling

No

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Weighing measurement in selling

1 Basket = 15 viss

60 (100.00)

42 (100.00)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Table 13. Mode of transportation to the market by sampled farm households

Mode of

transportation

Unit

Contract

farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract

farmers

(N=42)

Total

(N=102)

By light truck

No.

48 (80.00)

23 (54.76)

71 (69.61)

By tricycle

No.

12 (20.00)

19 (45.24)

30 (30.39)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Table 14. Market destinations of sampled farm households

Market

Contract farmers

(N=60)

Non-contract farmers

(N=42)

Total

(N=102)

Aunglan

57 (95.00)

39 (92.86)

96 (94.12)

Pyalo

3 (5.00)

3 (7.14)

6 (5.88)

Note: The values in the parentheses represent percentage.

Figure 8. Constraints in sesame production and marketing by sampled farm households in the study area

CONCLUSION

Contract farming can ensure year-round supply of sesame raw material at the required quantity and quality while ensuring sustainable market for farmers at a better price. Production cost of sesame by contract households was relatively higher than non-contract households due to their higher usage of material inputs (agro-inputs) and hired labor cost especially in harvesting stages and fertilization and pesticide application. Performance of contract households was better than that of non-contract households in the study area although contract scheme was not well structured and systematically comprehensive arranged between stakeholders in current situation. Limited access to credit by stakeholders led inadequacy of capital investment in sesame supply chain. Therefore, financial aid and credit access should be explored for enabling long term and short-term assistance from collaborating government and institutional lending agencies in order to eliminate the problem of inadequate capital among the sesame farmers. Provision of market information is very important for sesame market development to generate better income for stakeholders.

RECOMMENDATION