ABSTRACT

The outbreak and spreading of COVID-19 have worsened food and nutritional inequality in most countries. Korea is not an exception from the case. The food expenditure difference between the low-income group and the non-low-income group is also increasing, as well as the food insecurity rate. To mitigate the negative effects of food and nutritional inequality, the Korean government provides various food support programs, like rice discount coupons, pregnant women’s food bundle support, and children’s fruit support. Recently, the Korean government introduced new food and nutrition support pilot program, the food voucher program. The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program, which provides food budget to recipients. The food voucher can only be used to buy food, similar to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States. However, unlike the SNAP, the food voucher program is designed to use only specific domestic agricultural products to ensure the improvement of healthy dietary and domestic economic impacts. This study shows how the food voucher program has increased healthy food intakes, as well as the healthy eating index. In addition, this study shows the positive domestic economic impacts. At the moment of an increasing trend of food and nutritional inequality, the food voucher program can be the solution with positive economic impacts. Currently, the food voucher program is implemented as a pilot program. This study shows the necessity of the expansion of the food voucher program at the national level.

Keywords: Food assistance policy, Food voucher program, Food and nutritional inequality, Hybrid cash support program

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak and spreading of COVID-19 raise important issues related to food and nutrition. Social distancing and lockdowns have disrupted food systems globally, with consequences of inflation in food prices and food inequality. In addition, the loss of livelihoods due to economic distress has worsened food and nutritional inequality. For example, Mahler et al., (2022) estimated that 71 million people become part of those groups who are living in extremely poverty because of COVID-19.

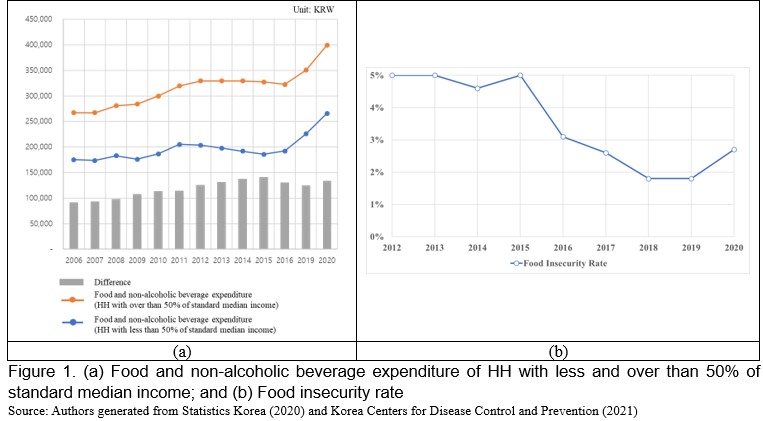

South Korea is no exception to the recent growth of food and nutritional inequality. The difference in food and non-alcoholic beverage expenditure between low-income group and non-low-income groups is rising again[1]. As well as food expenditure, the food insecurity rate is also rising (Figure 1).

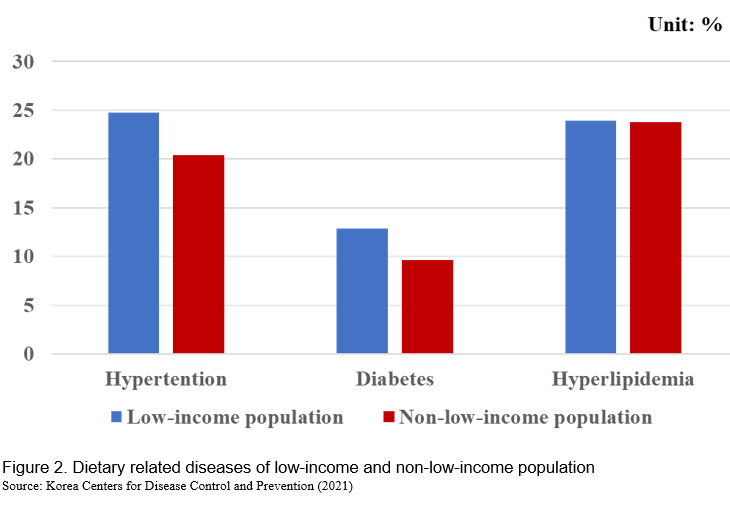

Food and nutritional inequality cause not only relative deprivation but also health-related costs. Food and nutritional inequality affect dietary-related diseases. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) shows 24.8% of the population with less than 50% of standard median income have hypertension, while the population with over 50% of standard median income have only 20.4%. Diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome also show similar trends (Figure 2). This is showing the current food inequality is also worsening the health status of low-income groups. Therefore, policies to reduce food and nutritional inequality are necessary to mitigate its socio-economic impacts on low-income groups.

This study introduces food and nutrition support programs in Korea. Especially, this study focuses on the food voucher program, which is recently introduced as a pilot program. The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program, which provides a food budget to recipients. Although it follows a traditional hybrid cash support program, it is designed to use only specific domestic agricultural products. This study analyzes the impacts of the food voucher program in terms of healthiness and the economy.

This study contributes to the policy design in two ways. First, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study proves that the novel policy design, limitation to specific agricultural products, can improve a healthy diet. Second, this study shows that among the domestic agricultural products, only food vouchers can improve domestic economic impacts.

The rest of this study will be as follows. Food and nutrition support programs in Korea are briefly described. Then, the food voucher program is introduced with its detailed designs. After the introduction of the food voucher, the effects analysis methods and results will be presented.

FOOD AND NUTRITION SUPPORT PROGRAMS IN KOREA

Cash-based support programs

National basic livelihood security (NBLS) is designed to secure minimum standards of living by monetary support, thus maintaining the difference between minimum costs for basic livelihood and household income. Although NBLS is a cumulative livelihood support program, it includes costs for food and nutritional support. Thus, NBLS can be partially considered as a cash-based food-support program.

NBLS has advantages in terms of utility maximization. Cash distributed from NBLS can be used without constraints; as such, recipients can determine NBLS use to maximize their utility. However, this can be a disadvantage, e.g., it can be used for non-food expenditures and to purchase unhealthy foods. Therefore, NBLS can maximize utility, but its effectiveness in food support is low.

In-kind based support programs

Korea has many in-kind support programs, e.g., rice discount coupons, pregnant women’s food bundle support, and children’s fruit support. Among those programs, subjects of pregnant women’s food bundle support and children’s fruit support programs are for pregnant women and children, regardless of household income. Thus, the rice discount coupon can be considered the main food and nutrition support program for the general low-income group.

The rice discount coupon program distributes discount coupons that can buy up to 10 kg of rice per person each month.[2] The coupon is distributed to households with less than 50% of the standard median income, i.e., the subjects of national basic livelihood security. In 2020, 117,000 tons of rice were sold with discount coupons; 975,000 people used rice discount coupons.

The rice discount coupon has advantages in term of effectiveness. It can be used only to buy rice, thus, effectively increasing rice intake. However, since it can be used only to buy rice, it has disadvantages in terms of utility.

FOOD VOUCHER PROGRAM

Introduction of food voucher program

Cash and in-kind-based food supports have obvious advantages and disadvantages. Cash support has advantages in utility but disadvantages in its effectiveness. On the other hand, in-kind support has advantages in effectiveness but also have disadvantages in terms of utility. A hybrid cash support program has been introduced to complement these two programs. Hybrid cash support provides a voucher that can be used for specific food types. Since they can choose what to buy, the utility can be increased. In addition, the effectiveness can be improved since subjects are specific agricultural products, usually healthy foods.

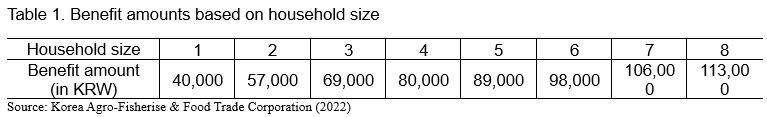

The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program for low-income individuals and families, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States. The food voucher program provides a benefits card that can be used to purchase food for the household. The amount of food voucher benefits is KRW40,000 (about US$31) for single-person households each month; it is adjusted for household size using the square root of household size (Table 1). Currently, the food voucher program is implemented as a pilot program for 15 counties in 2022 and is expected to start at the national level in 2025.

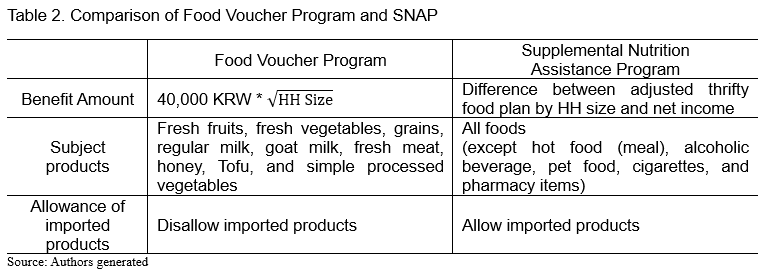

The food voucher program is similar to SNAP but was designed with several different points. First, the SNAP benefits can be used for specific agricultural products, even for frozen or canned foods. This causes many controversies about its health impacts (Shenkin and Jacobson, 2010; Hernandez, 2012). The subject of the food voucher are specific agricultural products, fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, grains, regular milk, goat milk, fresh meat, honey, tofu, and simple processed vegetables. Thus, the food voucher program is designed to encourage healthy eating.

Second, the food voucher is designed to be used only for domestic agricultural products. SNAP allows buying foods, regardless of country of origin, which may reduce domestic economic impacts of the program (Table 2). Unlike SNAP, the food voucher program requires grocery stores to use Point-of-Sales (POS) system, which is used for monitoring food voucher uses. Thus, the food voucher allows only domestic agricultural products and tries to maximize economic impacts.

Impacts of food voucher program

The main objectives of the food voucher program are the improvement of diet quality and the stimulus of domestic agricultural products consumption. This section examines whether the food voucher program has achieved its objectives.

Diet quality improvement

Since the food voucher program increases food expenditure, it may increase the diet quality of the low-income group with a high probability. However, its degree of improvement is dependent on various circumstances, such as marginal propensity to consume food and food accessibility. For example, if the marginal propensity to consume food is low, then diet quality may worsen. Therefore, this study investigates diet quality improvement by the food voucher program.

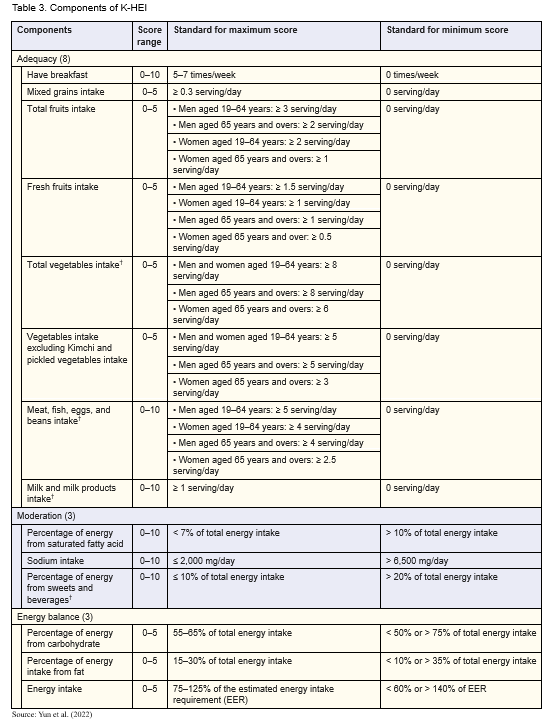

This study used the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), which is an index that shows overall diet quality, to evaluate diet improvement (Table 3). The index consists of three main components, i.e., adequacy, moderation, and energy balance. Adequacy is a component related to adequacy of food and nutritional intake and has eight subcomponents with a total of 55 scores. Moderation is a component related to the moderation of food and nutritional intake and has three subcomponents with a total of 30 scores. Energy balance is a component related to the balance of energy from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. The energy balance component has three subcomponents with a total of 15 scores. Thus, HEI has 100 as a maximum point and 0 as a minimum point.

This study used food voucher point-of-sales data and a household food purchase survey to analyze the effects of the food voucher program on K-HEI. First, food voucher point-of-sales data provide purchase details, including product name, quantity, category, price, and so on. With the purchase details, food voucher point-of-sales data includes non-food voucher products, which were purchased when the user used the food voucher. Therefore, food voucher point-of-sales data can be used to analyze food purchase patterns, including non-food voucher products.

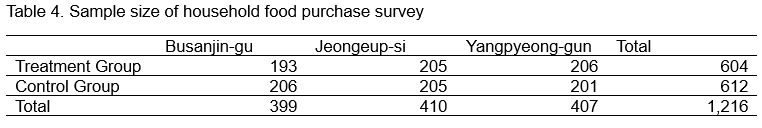

Second, this study used a household food purchase survey, which was a part of the 2022 food voucher pilot program. The household food purchase survey was collected from a total of 1,200 households in three participant areas, Busanjin-gu, Jeongeup-si, and Yangpyeong-gun. To utilize a difference-in-differences framework, the household food purchase survey consists of the pre-intervention period (March) and post-intervention period (April and May) with control and treatment groups.

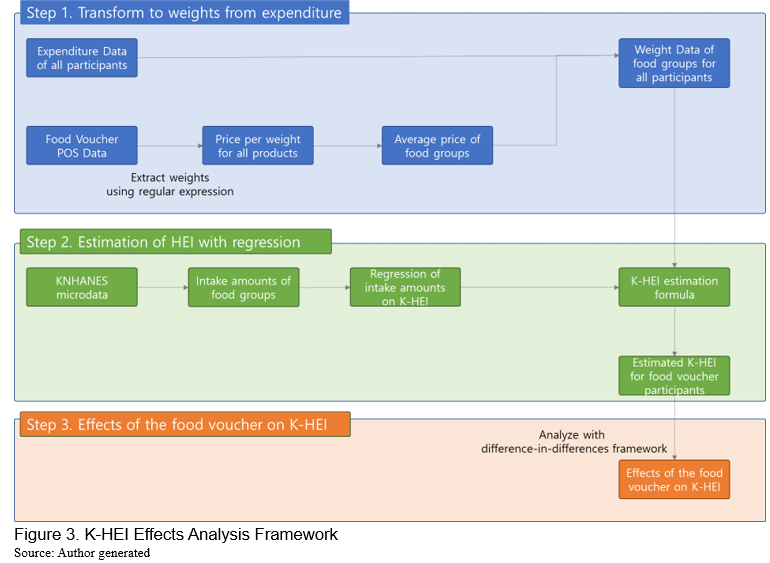

The effects of the food voucher program on K-HEI are analyzed in three steps: (1) estimation of the weight of food intake; (2) estimation of the relationship between food intake and K-HEI; and (3) estimation of K-HEI improvement by the food voucher using results from (1) and (2) (Figure 3) [3].

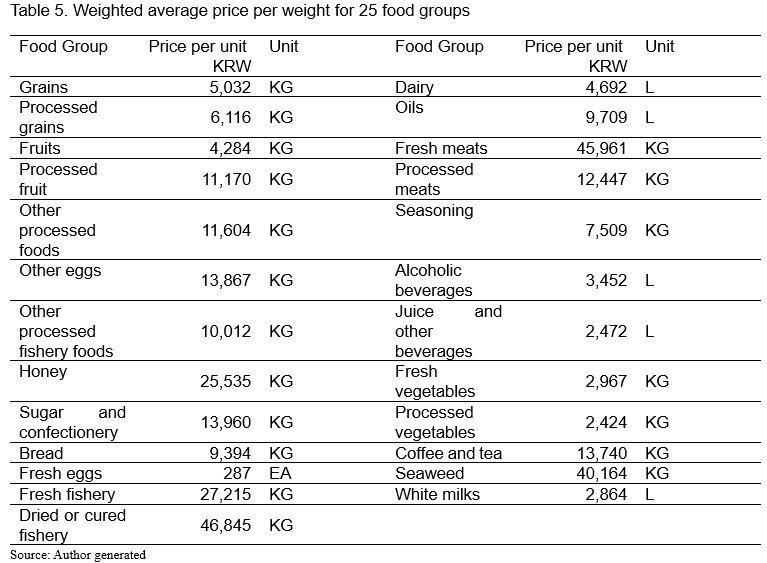

In the first step, this study estimated the weight of food intake from household food purchase survey and food voucher point-of-sales data. The household food purchase survey includes detailed information on food purchase patterns. However, it includes only expenditure, thus price per weight data is necessary to estimate food intake weights. This study extracted weight data from product names on food voucher point-of-sales data by using regular expressions. Then, the average price per weight was used to establish the aggregate weighted average price per weight for 25 food groups (Table 5). Finally, the weight of food intake can be estimated by using food expenditures and aggregate weighted average price per weight.

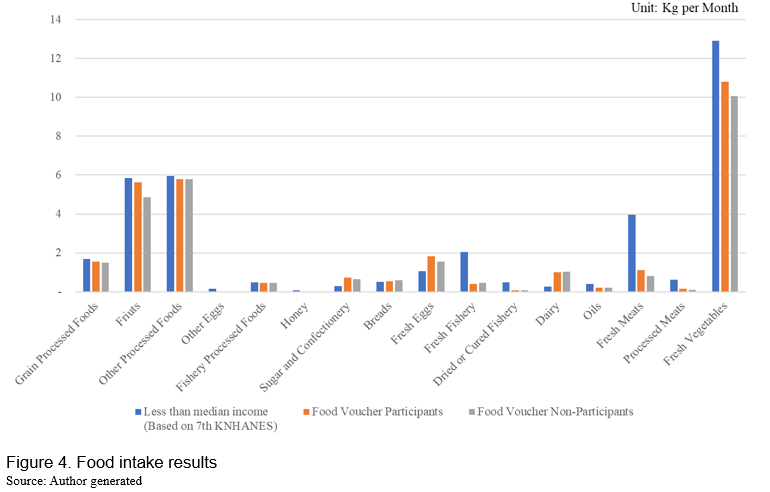

The results of food intake estimation suggest that the food voucher program has increased food intakes (Figure 4). After food voucher intervention, intake of fruits, vegetables, and fresh meats have increased by 0.8, 0.8, and 0.3 kg per month, respectively.

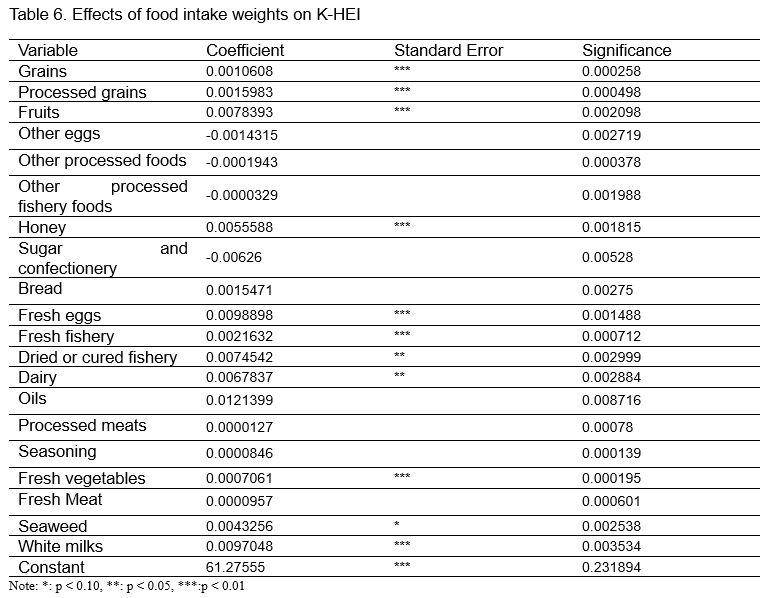

In the second step, the relationship between food intake and K-HEI was estimated by using Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. Korea national health and nutrition examination survey includes food intake weights and K-HEI at the individual level. Thus, regression on K-HEI with food intake weights can identify the relationship, and it is used to estimate K-HEI from food intake weights (Table 6).

In the third step, this study estimated the K-HEI change by the food voucher program. The effects of food voucher on K-HEI is analyzed by using the difference-in-differences framework, and it shows 0.37 points of K-HEI improvement by the food voucher program. The K-HEI of under and over 25% income groups are 60.1 and 63.2, respectively. Thus, the food voucher program filled about 10% of the K-HEI gap.

One of the main purposes of the food voucher program is food and nutrition support for low-income groups. The food voucher program has increased the amount and quality of food intake of the low-income group. In addition, surveys show that food intake has increased from 28.8% to 35.9%. Therefore, the food voucher program has achieved its main purpose, i.e., food and nutrition support for low-income groups.

Economic impacts

Rural areas in Korea suffer from the rapid speed of aging. According to Statistics Korea, the proportion of the farm population aged over 65 was 46.5% in 2021; it was 33.7% and 38.4% in 2011 and 2015, respectively. There are many reasons for this rapid aging trend but mainly because of the young farm population’s urban relocation. Therefore, generating new economic growth points is necessary to reduce urban relocation.

The food voucher program can result in new economic growth points for agricultural sectors. Since the food voucher program increases expenditures on agricultural products, it will drive an increase in demand for those products.[4] In addition, the increased agricultural demand will have ripple effects on other industries. This study analyzes the economic impacts of the food voucher program with an input–output model.

Input–output analysis is typically used to estimate the impacts of economic shocks and analyze ripple effects through an input–output table, which describes interdependency between different industries. The input–output table features a series of rows and columns of data that show the supply chain for all sectors in an economy. The input–output table is thus able to analyze the effects of economic shock in some industries on the whole economy.[5]

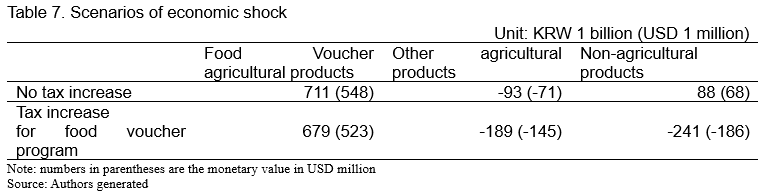

We assumed that in total KRW1,237 billion (US$950 million) is distributed as the food voucher based on population and household size of low-income groups. In addition, we assumed that the food voucher value is distributed to industries by the marginal propensity to consume, which was analyzed by Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected). The economic shock scenario is described in Table 7.

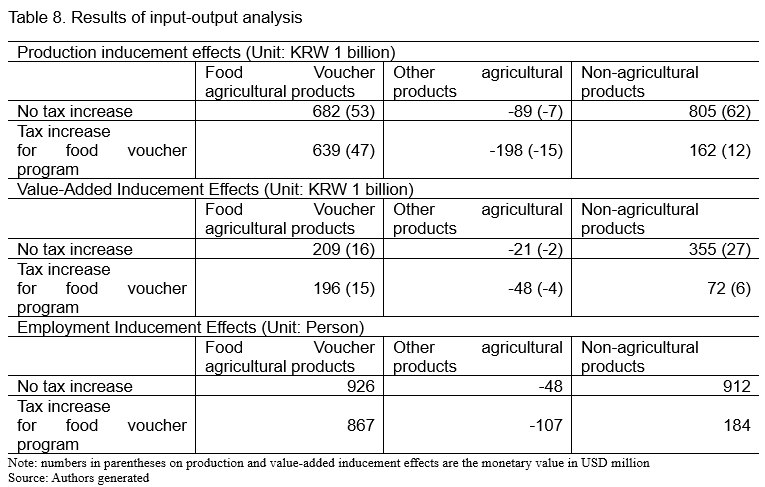

The results of input–output analysis showed that the food voucher program has positive effects on the economy (Table 8). When we do not consider tax increases, the food voucher program has total KRW1.3 trillion inducement in production, KRW0.54 trillion inducement in value added, and 17,903 inducement in employment. When we consider tax increase, the food voucher program has a total of KRW0.6 trillion inducement in production, KRW0.22 trillion inducement in value added, and 9,439 inducement in employment. Therefore, the food voucher program may have a positive effect on the agricultural sector.

CONCLUSION

Many efforts are tied to reduce food and nutritional inequality. However, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, food and nutritional inequality have intensified. Over the recent three years, low-income groups have suffered from the outbreak of COVID-19. Korea is not an exception to these recent food and nutritional inequality trends. To mitigate inequality, the Korean government is trying to introduce a hybrid cash support, food voucher program.

The objectives of the food voucher program are to improve healthy eating dietary and to maximize domestic economic impacts. The food voucher program differs from SNAP in two points to achieve the objectives. First, the food voucher can be used for specific agricultural products. The food voucher has increased fresh meat, fruit, and vegetable intake. In addition, increased intake has improved the healthy eating index. Second, imported agricultural products are excluded from the subjects of the food voucher program. Excluding imported goods from these programs helps to increase positive domestic economic impacts.

Although this study showed that the food voucher program has achieved its own objectives, future research is needed to increase the program’s effectiveness. For example, the effects of food education and food accessibility need to be analyzed to build a more contextualized food voucher program.

REFERENCES

Hernandez, D. (2012). Soda Consumption Among Food Insecure Households with Children: A Call to Restructure Food Assistance Policy. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 3(1). https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol3/iss1/16

Korea Agro-Fisherise & Food Trade Corporation. (2022). Food Voucher Program. Retrieved December 28, 2022, from https://www.at.or.kr/fooddream

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Korea Rural Economic Institute. (2020). The consumer behavior survey for food.

Mahler, D. G., Yonzan, N., & Lakner, C. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on global inequality and poverty.

Shenkin, J. D., & Jacobson, M. F. (2010). Using the Food Stamp Program and Other Methods to Promote Healthy Diets for Low-Income Consumers. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1562–1564. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.198549

Statistics Korea. (2020). Household Expenditure Survey.

Statistics Korea. (2022). Census of agriculture, forestry and fisheries. Statistics Korea. Daejeon, Republic of Korea: National Statistics Service. Available at: Kostat. Go. Kr.

Yun, S., Park, S., Yook, S.-M., Kim, K., Shim, J. E., Hwang, J.-Y., & Oh, K. (2022). Development of the Korean Healthy Eating Index for adults, based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrition Research and Practice, 16(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2022.16.2.233

[1] The low-income group is defined as households with less than 50% of the standard median income based on the National Basic Livelihood Security Act.

[2] The discount rate is 60% for households with 40 to 50% of standard median income, and 90% for households with under 40% of standard median income.

[3] The method detail is available on Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected)

[4] Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected) used a partial equilibrium model and showed the agricultural income increase by the food voucher program.

[5] The method detail is available on Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected).

Food and Nutrition Assistance Policies in Korea: Focus on Food Voucher Program

ABSTRACT

The outbreak and spreading of COVID-19 have worsened food and nutritional inequality in most countries. Korea is not an exception from the case. The food expenditure difference between the low-income group and the non-low-income group is also increasing, as well as the food insecurity rate. To mitigate the negative effects of food and nutritional inequality, the Korean government provides various food support programs, like rice discount coupons, pregnant women’s food bundle support, and children’s fruit support. Recently, the Korean government introduced new food and nutrition support pilot program, the food voucher program. The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program, which provides food budget to recipients. The food voucher can only be used to buy food, similar to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States. However, unlike the SNAP, the food voucher program is designed to use only specific domestic agricultural products to ensure the improvement of healthy dietary and domestic economic impacts. This study shows how the food voucher program has increased healthy food intakes, as well as the healthy eating index. In addition, this study shows the positive domestic economic impacts. At the moment of an increasing trend of food and nutritional inequality, the food voucher program can be the solution with positive economic impacts. Currently, the food voucher program is implemented as a pilot program. This study shows the necessity of the expansion of the food voucher program at the national level.

Keywords: Food assistance policy, Food voucher program, Food and nutritional inequality, Hybrid cash support program

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak and spreading of COVID-19 raise important issues related to food and nutrition. Social distancing and lockdowns have disrupted food systems globally, with consequences of inflation in food prices and food inequality. In addition, the loss of livelihoods due to economic distress has worsened food and nutritional inequality. For example, Mahler et al., (2022) estimated that 71 million people become part of those groups who are living in extremely poverty because of COVID-19.

South Korea is no exception to the recent growth of food and nutritional inequality. The difference in food and non-alcoholic beverage expenditure between low-income group and non-low-income groups is rising again[1]. As well as food expenditure, the food insecurity rate is also rising (Figure 1).

Food and nutritional inequality cause not only relative deprivation but also health-related costs. Food and nutritional inequality affect dietary-related diseases. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) shows 24.8% of the population with less than 50% of standard median income have hypertension, while the population with over 50% of standard median income have only 20.4%. Diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome also show similar trends (Figure 2). This is showing the current food inequality is also worsening the health status of low-income groups. Therefore, policies to reduce food and nutritional inequality are necessary to mitigate its socio-economic impacts on low-income groups.

This study introduces food and nutrition support programs in Korea. Especially, this study focuses on the food voucher program, which is recently introduced as a pilot program. The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program, which provides a food budget to recipients. Although it follows a traditional hybrid cash support program, it is designed to use only specific domestic agricultural products. This study analyzes the impacts of the food voucher program in terms of healthiness and the economy.

This study contributes to the policy design in two ways. First, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study proves that the novel policy design, limitation to specific agricultural products, can improve a healthy diet. Second, this study shows that among the domestic agricultural products, only food vouchers can improve domestic economic impacts.

The rest of this study will be as follows. Food and nutrition support programs in Korea are briefly described. Then, the food voucher program is introduced with its detailed designs. After the introduction of the food voucher, the effects analysis methods and results will be presented.

FOOD AND NUTRITION SUPPORT PROGRAMS IN KOREA

Cash-based support programs

National basic livelihood security (NBLS) is designed to secure minimum standards of living by monetary support, thus maintaining the difference between minimum costs for basic livelihood and household income. Although NBLS is a cumulative livelihood support program, it includes costs for food and nutritional support. Thus, NBLS can be partially considered as a cash-based food-support program.

NBLS has advantages in terms of utility maximization. Cash distributed from NBLS can be used without constraints; as such, recipients can determine NBLS use to maximize their utility. However, this can be a disadvantage, e.g., it can be used for non-food expenditures and to purchase unhealthy foods. Therefore, NBLS can maximize utility, but its effectiveness in food support is low.

In-kind based support programs

Korea has many in-kind support programs, e.g., rice discount coupons, pregnant women’s food bundle support, and children’s fruit support. Among those programs, subjects of pregnant women’s food bundle support and children’s fruit support programs are for pregnant women and children, regardless of household income. Thus, the rice discount coupon can be considered the main food and nutrition support program for the general low-income group.

The rice discount coupon program distributes discount coupons that can buy up to 10 kg of rice per person each month.[2] The coupon is distributed to households with less than 50% of the standard median income, i.e., the subjects of national basic livelihood security. In 2020, 117,000 tons of rice were sold with discount coupons; 975,000 people used rice discount coupons.

The rice discount coupon has advantages in term of effectiveness. It can be used only to buy rice, thus, effectively increasing rice intake. However, since it can be used only to buy rice, it has disadvantages in terms of utility.

FOOD VOUCHER PROGRAM

Introduction of food voucher program

Cash and in-kind-based food supports have obvious advantages and disadvantages. Cash support has advantages in utility but disadvantages in its effectiveness. On the other hand, in-kind support has advantages in effectiveness but also have disadvantages in terms of utility. A hybrid cash support program has been introduced to complement these two programs. Hybrid cash support provides a voucher that can be used for specific food types. Since they can choose what to buy, the utility can be increased. In addition, the effectiveness can be improved since subjects are specific agricultural products, usually healthy foods.

The food voucher program is a hybrid cash support program for low-income individuals and families, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States. The food voucher program provides a benefits card that can be used to purchase food for the household. The amount of food voucher benefits is KRW40,000 (about US$31) for single-person households each month; it is adjusted for household size using the square root of household size (Table 1). Currently, the food voucher program is implemented as a pilot program for 15 counties in 2022 and is expected to start at the national level in 2025.

The food voucher program is similar to SNAP but was designed with several different points. First, the SNAP benefits can be used for specific agricultural products, even for frozen or canned foods. This causes many controversies about its health impacts (Shenkin and Jacobson, 2010; Hernandez, 2012). The subject of the food voucher are specific agricultural products, fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, grains, regular milk, goat milk, fresh meat, honey, tofu, and simple processed vegetables. Thus, the food voucher program is designed to encourage healthy eating.

Second, the food voucher is designed to be used only for domestic agricultural products. SNAP allows buying foods, regardless of country of origin, which may reduce domestic economic impacts of the program (Table 2). Unlike SNAP, the food voucher program requires grocery stores to use Point-of-Sales (POS) system, which is used for monitoring food voucher uses. Thus, the food voucher allows only domestic agricultural products and tries to maximize economic impacts.

Impacts of food voucher program

The main objectives of the food voucher program are the improvement of diet quality and the stimulus of domestic agricultural products consumption. This section examines whether the food voucher program has achieved its objectives.

Diet quality improvement

Since the food voucher program increases food expenditure, it may increase the diet quality of the low-income group with a high probability. However, its degree of improvement is dependent on various circumstances, such as marginal propensity to consume food and food accessibility. For example, if the marginal propensity to consume food is low, then diet quality may worsen. Therefore, this study investigates diet quality improvement by the food voucher program.

This study used the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), which is an index that shows overall diet quality, to evaluate diet improvement (Table 3). The index consists of three main components, i.e., adequacy, moderation, and energy balance. Adequacy is a component related to adequacy of food and nutritional intake and has eight subcomponents with a total of 55 scores. Moderation is a component related to the moderation of food and nutritional intake and has three subcomponents with a total of 30 scores. Energy balance is a component related to the balance of energy from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. The energy balance component has three subcomponents with a total of 15 scores. Thus, HEI has 100 as a maximum point and 0 as a minimum point.

This study used food voucher point-of-sales data and a household food purchase survey to analyze the effects of the food voucher program on K-HEI. First, food voucher point-of-sales data provide purchase details, including product name, quantity, category, price, and so on. With the purchase details, food voucher point-of-sales data includes non-food voucher products, which were purchased when the user used the food voucher. Therefore, food voucher point-of-sales data can be used to analyze food purchase patterns, including non-food voucher products.

Second, this study used a household food purchase survey, which was a part of the 2022 food voucher pilot program. The household food purchase survey was collected from a total of 1,200 households in three participant areas, Busanjin-gu, Jeongeup-si, and Yangpyeong-gun. To utilize a difference-in-differences framework, the household food purchase survey consists of the pre-intervention period (March) and post-intervention period (April and May) with control and treatment groups.

The effects of the food voucher program on K-HEI are analyzed in three steps: (1) estimation of the weight of food intake; (2) estimation of the relationship between food intake and K-HEI; and (3) estimation of K-HEI improvement by the food voucher using results from (1) and (2) (Figure 3) [3].

In the first step, this study estimated the weight of food intake from household food purchase survey and food voucher point-of-sales data. The household food purchase survey includes detailed information on food purchase patterns. However, it includes only expenditure, thus price per weight data is necessary to estimate food intake weights. This study extracted weight data from product names on food voucher point-of-sales data by using regular expressions. Then, the average price per weight was used to establish the aggregate weighted average price per weight for 25 food groups (Table 5). Finally, the weight of food intake can be estimated by using food expenditures and aggregate weighted average price per weight.

The results of food intake estimation suggest that the food voucher program has increased food intakes (Figure 4). After food voucher intervention, intake of fruits, vegetables, and fresh meats have increased by 0.8, 0.8, and 0.3 kg per month, respectively.

In the second step, the relationship between food intake and K-HEI was estimated by using Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. Korea national health and nutrition examination survey includes food intake weights and K-HEI at the individual level. Thus, regression on K-HEI with food intake weights can identify the relationship, and it is used to estimate K-HEI from food intake weights (Table 6).

In the third step, this study estimated the K-HEI change by the food voucher program. The effects of food voucher on K-HEI is analyzed by using the difference-in-differences framework, and it shows 0.37 points of K-HEI improvement by the food voucher program. The K-HEI of under and over 25% income groups are 60.1 and 63.2, respectively. Thus, the food voucher program filled about 10% of the K-HEI gap.

One of the main purposes of the food voucher program is food and nutrition support for low-income groups. The food voucher program has increased the amount and quality of food intake of the low-income group. In addition, surveys show that food intake has increased from 28.8% to 35.9%. Therefore, the food voucher program has achieved its main purpose, i.e., food and nutrition support for low-income groups.

Economic impacts

Rural areas in Korea suffer from the rapid speed of aging. According to Statistics Korea, the proportion of the farm population aged over 65 was 46.5% in 2021; it was 33.7% and 38.4% in 2011 and 2015, respectively. There are many reasons for this rapid aging trend but mainly because of the young farm population’s urban relocation. Therefore, generating new economic growth points is necessary to reduce urban relocation.

The food voucher program can result in new economic growth points for agricultural sectors. Since the food voucher program increases expenditures on agricultural products, it will drive an increase in demand for those products.[4] In addition, the increased agricultural demand will have ripple effects on other industries. This study analyzes the economic impacts of the food voucher program with an input–output model.

Input–output analysis is typically used to estimate the impacts of economic shocks and analyze ripple effects through an input–output table, which describes interdependency between different industries. The input–output table features a series of rows and columns of data that show the supply chain for all sectors in an economy. The input–output table is thus able to analyze the effects of economic shock in some industries on the whole economy.[5]

We assumed that in total KRW1,237 billion (US$950 million) is distributed as the food voucher based on population and household size of low-income groups. In addition, we assumed that the food voucher value is distributed to industries by the marginal propensity to consume, which was analyzed by Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected). The economic shock scenario is described in Table 7.

The results of input–output analysis showed that the food voucher program has positive effects on the economy (Table 8). When we do not consider tax increases, the food voucher program has total KRW1.3 trillion inducement in production, KRW0.54 trillion inducement in value added, and 17,903 inducement in employment. When we consider tax increase, the food voucher program has a total of KRW0.6 trillion inducement in production, KRW0.22 trillion inducement in value added, and 9,439 inducement in employment. Therefore, the food voucher program may have a positive effect on the agricultural sector.

CONCLUSION

Many efforts are tied to reduce food and nutritional inequality. However, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, food and nutritional inequality have intensified. Over the recent three years, low-income groups have suffered from the outbreak of COVID-19. Korea is not an exception to these recent food and nutritional inequality trends. To mitigate inequality, the Korean government is trying to introduce a hybrid cash support, food voucher program.

The objectives of the food voucher program are to improve healthy eating dietary and to maximize domestic economic impacts. The food voucher program differs from SNAP in two points to achieve the objectives. First, the food voucher can be used for specific agricultural products. The food voucher has increased fresh meat, fruit, and vegetable intake. In addition, increased intake has improved the healthy eating index. Second, imported agricultural products are excluded from the subjects of the food voucher program. Excluding imported goods from these programs helps to increase positive domestic economic impacts.

Although this study showed that the food voucher program has achieved its own objectives, future research is needed to increase the program’s effectiveness. For example, the effects of food education and food accessibility need to be analyzed to build a more contextualized food voucher program.

REFERENCES

Hernandez, D. (2012). Soda Consumption Among Food Insecure Households with Children: A Call to Restructure Food Assistance Policy. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 3(1). https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol3/iss1/16

Korea Agro-Fisherise & Food Trade Corporation. (2022). Food Voucher Program. Retrieved December 28, 2022, from https://www.at.or.kr/fooddream

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Korea Rural Economic Institute. (2020). The consumer behavior survey for food.

Mahler, D. G., Yonzan, N., & Lakner, C. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on global inequality and poverty.

Shenkin, J. D., & Jacobson, M. F. (2010). Using the Food Stamp Program and Other Methods to Promote Healthy Diets for Low-Income Consumers. American Journal of Public Health, 100(9), 1562–1564. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.198549

Statistics Korea. (2020). Household Expenditure Survey.

Statistics Korea. (2022). Census of agriculture, forestry and fisheries. Statistics Korea. Daejeon, Republic of Korea: National Statistics Service. Available at: Kostat. Go. Kr.

Yun, S., Park, S., Yook, S.-M., Kim, K., Shim, J. E., Hwang, J.-Y., & Oh, K. (2022). Development of the Korean Healthy Eating Index for adults, based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrition Research and Practice, 16(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2022.16.2.233

[1] The low-income group is defined as households with less than 50% of the standard median income based on the National Basic Livelihood Security Act.

[2] The discount rate is 60% for households with 40 to 50% of standard median income, and 90% for households with under 40% of standard median income.

[3] The method detail is available on Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected)

[4] Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected) used a partial equilibrium model and showed the agricultural income increase by the food voucher program.

[5] The method detail is available on Korea Rural Economic Institute (2023 expected).