ABSTRACT

In Myanmar, Shan State is the major sweet corn production area, and Nay Pyi Taw Council Area is one of the sweet corn growing places. Sweet corn is a potential crop to produce value-added products as a result of its increasing popularity as a preferred crop choice. Therefore, the purposes of the study are to investigate the sweet corn production trend and farmers’ willingness to grow sweet corn in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. The Department of Agriculture (DOA), MOALI, Nay Pyi Taw provided pertinent secondary statistics on sweet corn production. In May 2018, structured questionnaires were used to conduct a field study to 50 farmers from Nweyit village and 51 farmers from other villages by using random sampling. Based on the research findings, sweet corn production was greatest in Lewe Township and second highest in Pobbathiri Township over a six-year period, according to data on overall sweet corn production in the eight townships of the Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Year after year, the amount of sweet corn grown area, harvested area, and the total production in Nay Pyi Taw had increased to some extent. According to the research findings, nearly half of the sample farmers in other villages had completed secondary school, whereas only one-third of the sample respondents in Nweyit village had completed primary education. The predominant occupation of the total respondents in both study regions - Nweyit and other villages - was farmer, with almost half of total farmers in Nweyit village mostly growing sweet corn, compared to one-third of total farmers in other villages. In Nweyit village, three-quarters of total farmers considered that sweet corn production was economically favorable and desired to produce it all year, whereas in other villages, half of the farmers thought sweet corn production was economically attractive. In the study areas, most of the farmers sold their products to the brokers directly. In addition, when farmers sell their products, sweet corn production is less profitable than other comparative crops. As a result, some farmers have switched to producing other crops instead of sweet corn and have reduced sweet corn acreage. Therefore, if the government wants to encourage farmers to plant more sweet corn production, it needs to provide a good market for stable sweet corn prices, and food processing technologies to produce sweet corn processing foods. Contract farming practices, attractive investments for processing factory and logistic facility are the critical factors for sweet corn development for all stake holders in Myanmar.

Keywords: Comparative crops, economic feasibility, farmers, sweet corn, willingness to grow

INTRODUCTION

Sweet corn production in Myanmar

Corn is grown all around the world, though yields vary significantly, and it is the second most abundant cereal crop grown for human consumption. Corn is a highly adaptable crop, and everything on a corn plant can be used. Many populations, particularly in Africa, still eat corn as a primary food. The way corn is processed and consumed differs substantially from one country to the next. There is no waste from the part of the corn plant. Tamales are traditionally made with the husk of corn (Sailer, 2012). The kernels are used to make food, and the stalks are fed to animals, as well as the silks are used to make medicinal teas. In 2019, the world's corn production totaled 1,148 million tons. Moreover, the United States of America is the world's leading producer of corn. The United States of America produced 360,252 thousand tons of corn in 2020, accounting for 34.28% of global corn production. China, Brazil, Argentina, and Ukraine make up the top five countries, accounting for 74.86% of the total corn production (WMPQ, 2020).

In Myanmar, corn is also the second most significant cereal in Myanmar after rice, and it is farmed throughout the country (DOA, 2020). According to the secondary data from the Department of Agriculture in 2019-2020, the total sweet corn sown area in Myanmar was 309,192 hectares, and the total harvested area was 308,306 hectares. Moreover, the average total sweet corn yielded 7.2 tons per ha (1 ear = 0.00018 tons (VCC, 2016)), and the national sweet corn production was 2,316 thousand tons. The main sweet corn-producing areas in Myanmar are primarily found in the country's dry zones and hilly regions, with smaller production occurring in the delta and coastal areas. The main sweet corn crop is cultivated during the rainy season from May to June and harvested in August-September, particularly in the central dry zone and hilly regions.

About 90% of Myanmar's corn crop is grown in rain-fed areas. The majority (60-65%) of Myanmar’s corn production is exported to China. Furthermore, animal feed for domestic farms accounts for around 30-35% of Myanmar's maize supply, while seeds, food processing, and alcohol manufacture account for the remaining 5-6% (Demaree, 2016). Corn export supplies are often transported to Mandalay, Central Myanmar's largest wholesale market, and then carried to northeastern border towns including Muse, Chin Shwe Haw, Lwejel, and Kan Paiktee for export (Swe & Swe, 2015).

Nay Pyi Taw Region, located in the central dry zone areas, is one of the corn-growing zones, with a total area of 10,460 hectares planted in the rainy and winter seasons. Corn growers are divided into two categories: those who grow corn for animal feed and those who grow corn for human consumption. Corn seed growers for animal feed cover 7,439 hectares in the Nay Pyi Taw Region, while sweet corn growers for human use cover 3,020 hectares (DOA, 2016).

Sweet corn requires a high level of input, irrigation, and intensive pest management techniques. Improving the value-added production system of sweet corn due to the high cultivation costs is an important step towards increasing crop adoption. Sweet corn kernels can be used to make a variety of products, and they can be eaten fresh or cooked, frozen, canned, or juiced. Therefore, nowadays, sweet corn is one of the potential crops to produce value-added products because of its growing popularity by their good taste. Moreover, investment in the sweet corn canning industry is being interested in the feasibility and willingness of growth farmers in Nay Pyi Taw. Therefore, in the study, sweet corn was chosen as the main target crop to produce value-added products and the development of SME in the region.

Objectives of the study

- To study the long-term sweet corn production trend in Nay Pyi Taw Region

- To determine the farmers’ attitudes for willingness to grow sweet corn in the study area

- To investigate the marketing activities of sweet corn farmers

METHODOLOGY

Study sites selection for data collection

There are eight administrative townships in Nay Pyi Taw Region. They are Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships. These all townships were chosen to observe the sweet corn production trend in Nay Pyi Taw Region. To study the second purpose of the research, Pobbathiri, Zeyarthiri, Lewe, and Tatkon Townships were randomly selected as the study sites because of the large amount of sweet corn grown in the area (DOA, 2017).

Data collection and analysis

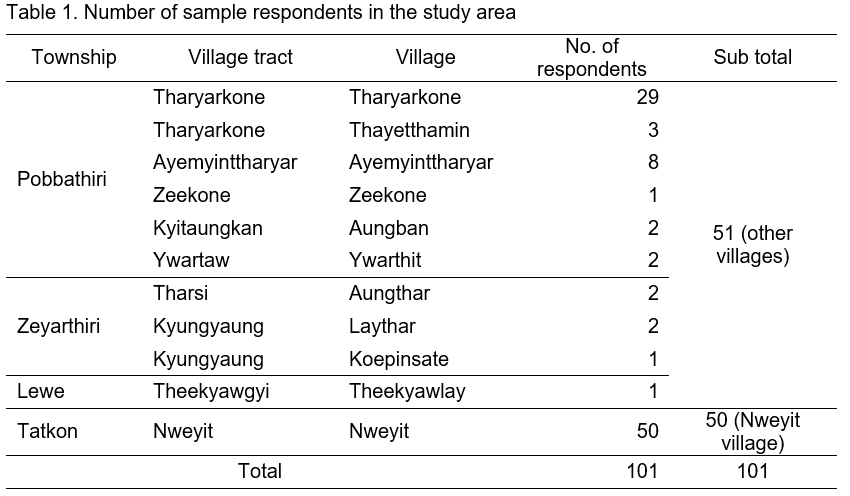

In this study, both primary and secondary data were collected. The secondary data included yield, sown area, harvested area, total production of sweet corn in both monsoon and winter seasons. The relevant secondary data was accumulated from the Department of Agriculture (DOA), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation-MOALI, Nay Pyi Taw. The field survey was conducted in May 2018 to get the primary data. In the study areas, 9 village tracts and 11 sample villages were randomly selected, and 50 farmers from Nweyit village tract and 51 farmers from other village tracts were interviewed (Table 1).

Data were accumulated for the investigation of demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers, major crops grown by sample farmers, and perception of farmers on sweet corn production. The collected quantitative and qualitative data were first integrated into the Microsoft Excel program. Descriptive statistics methods such as mean, average, frequency, percentage were used to obtain results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sweet corn production trend in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory

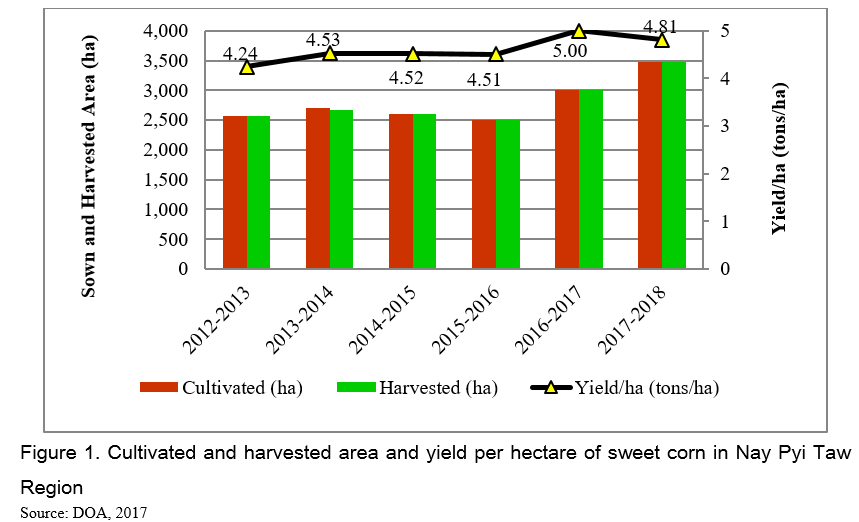

In Nay Pyi Taw Region, the status of sweet corn production was the highest in 2017-2018 because of farmers' interest to produce value-added sweet corn products. The cultivated area and the harvested area of sweet corn in the region slightly increased from 2,575 ha in 2012-2013 to 3,481 ha in 2017-2018. Figure 1 shows the cultivated and harvested area and yield/ha of sweet corn for 6 years in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. In 2012-2013, the yield of sweet corn in the whole region was low, and it was 4.24 tons per hectare. Despite that, the yield/ha of sweet corn significantly improved in 2016-2017, and the yield was 5.00 tons/ha, but it was faintly decreased to 4.81 tons per hectare in 2017-2018.

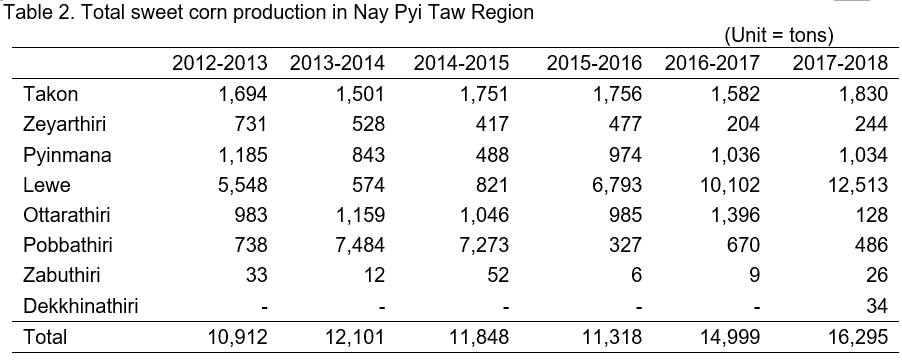

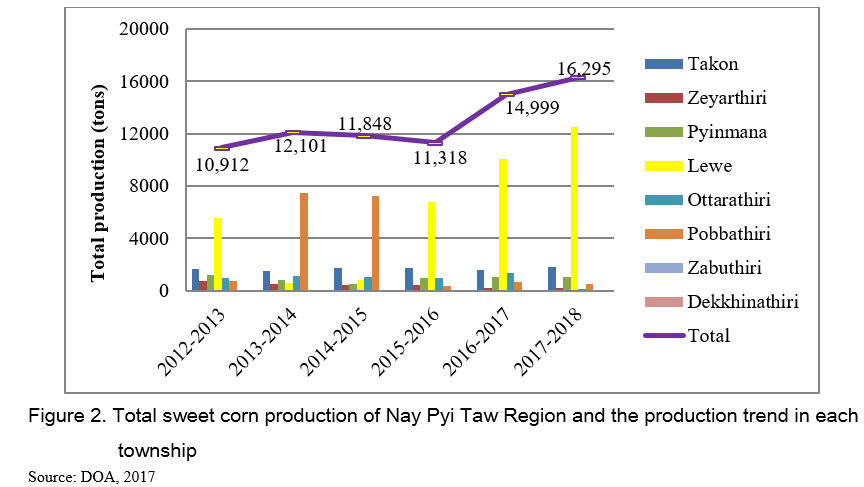

During the crop season of 2012-2018, Lewe Township was the largest sweet corn producer out of eight townships in Nay Pyi Taw Region, and the sweet corn production in the township rose from about 5,548 tons in 2012-2013 to about 12,513 tons in 2017-2018. Moreover, Pobbathiri Township was the second-highest sweet corn production, and the corn production in the township peaked in 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. During the 2012-2016 planting season, there was no sweet corn production in Dekkhinathiri Township, but in 2017-2018 there was little corn production in that township. The total sweet corn production of the whole region significantly increased, and it was about 10,912 and 16,295 tons in 2012-2013 and 2017-2018 respectively. The conditions of total sweet corn production in Nay Pyi Taw Region and the corn production trend in each township are described in Table 2 and Figure 2.

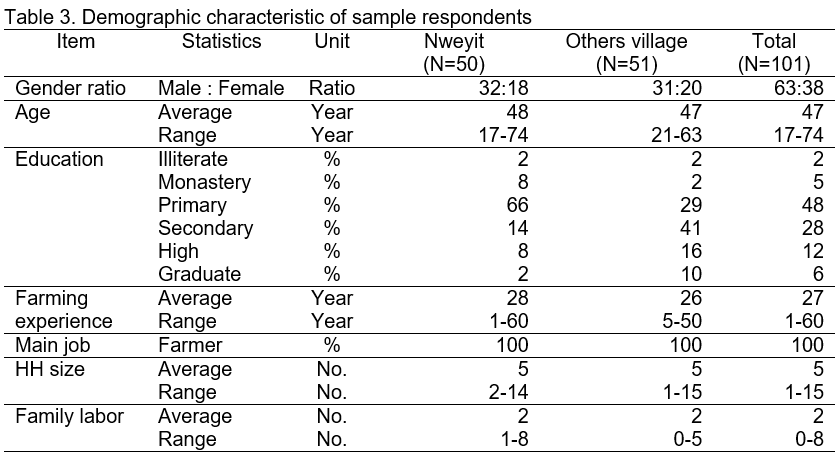

Demographic characteristics of sample respondents

In this study, demographic characteristics of sample sweet corn farmers were gathered by using structured questionnaires. That information is presented in Table 3. In total, the gender ratio of the sample farmers in the study area was 63 male: 38 female, and the average value of sample respondents’ age was 47 years with a range of a minimum of 17 years to a maximum of 74 years.

The educational percentages of the sample farmers in Nweyit village were 2% (illiterate), 8% (monastery), 66% (primary), 14% (secondary), 8% (high school) and 2% (university). In other villages, the percentages of educational levels of sample respondents were 1.96%, 1.96%, 29.41%, 41.18%, 15.69%, and 9.8% for illiterate, monastery, primary school, middle school, high school, and university in turn. Based on the results, it was found that almost half of the sample farmers in other villages received secondary education, and one-third of the sample respondents in Nweyit village had primary education.

Depending on the results of the survey, the average farming experience of the total sample respondents in the study was 27 years, ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 60 years. In both study areas, the main occupations of all respondents from Nweyit village and other villages were farmers. The average total numbers of household sizes in the study area were 5, and the maximum and minimum household sizes were 15 and 1, respectively. In addition, the average family worker involved in crop production of all total respondents was 2, with a range of a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 8.

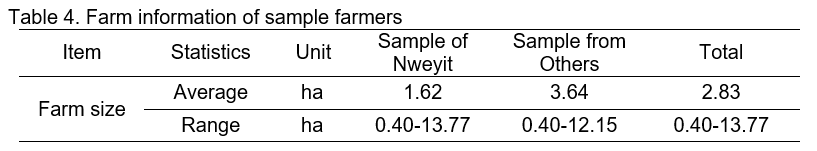

Farm information and major crops of sample farmers

In Table 4, the average farm size of total farmers in the study area was 2.83 hectares with a range of a minimum of 0.40 ha to a maximum of 13.77 ha. In detail, the average farm size of the respondents in Nweyit village was 1.62 ha, and the average farm size of the respondents in other villages was 3.64 ha.

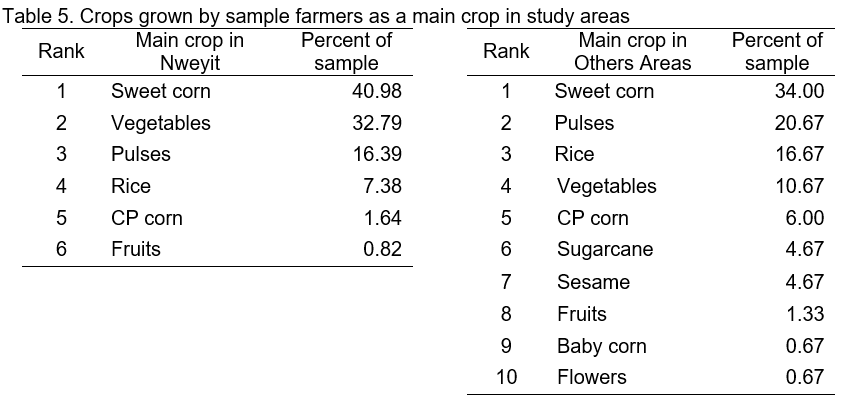

According to the surveyed data, the main crops grown by sample farmers in Nweyit village were sweet corn, vegetables, pulses, rice, CP corn, and fruits. Among these crops, sweet corn (40.98%) was the priority crop, followed by vegetables (32.79%) and pulses (16.39%). In the other villages, the farmers planted sweet corn as the main crop. The sample respondents from other villages planted 10 different crops. Of these, sweet corn (34%), pulses (20.67%), and rice (16.67%) were cultivated (Table 5).

Farmers’ willingness to grow sweet corn production

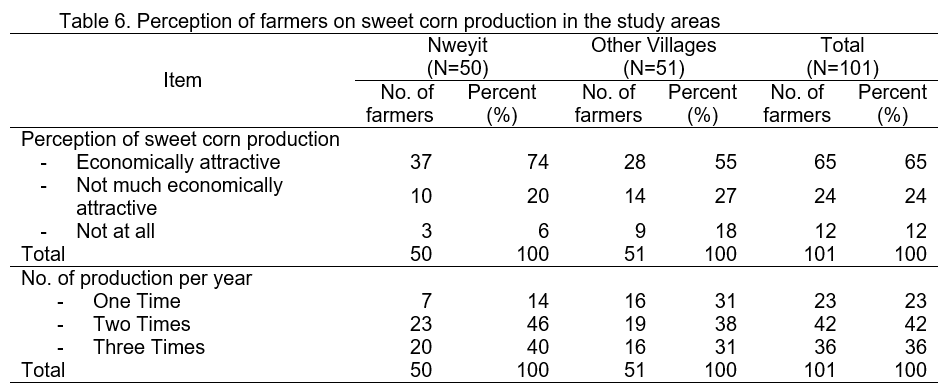

The perspectives of farmers on sweet corn production were described in Table 6. The total farmers (64.36%) in the study areas thought sweet corn was an economically attractive crop compared to other cash crops, and most farmers in Nweyit village (74%) and other villages (55%) had the willingness to grow in their farms. But, 23.76% of the farmers answered that they do not want to plant sweet corn all year round because its production was not economically attractive. Moreover, only a few farmers (11.88%) perceived the sweet corn was a non-profit crop, and they do not have any desire to produce it in their fields. Regarding the perception of the number of sweet corn production per year, farmers in Nweyit village and other villages would like to produce sweet corn at least once and up to three times a year, but most of them preferred to grow sweet corn twice a year. The farmers (41.58%) in the surveyed areas could produce sweet corn twice a year. In addition, the farmers were possible to grow sweet corn only once a year (22.77%) and three times a year (35.64%).

Marketing Activities of Sweet Corn Farmers

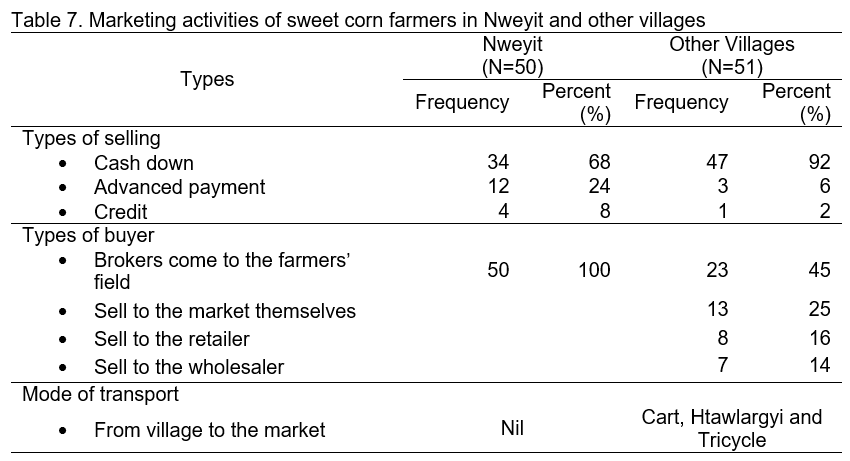

Table 7 depicts the sweet corn farmers' marketing activities, such as the types of sales, buyers, and modes of transportation. In Nweyit village, 68% of total farmers sold sweet corn with a cash down payment system, while 24% sold with advanced payment, and 8% with credit. In other villages, the majority of farmers (92%) sold sweet corn with a cash down payment system. A few farmers sold the crop with advanced payment (6%), and credit (2%) in turn.

According to the types of buyers, all of the farmers in Nweyit village sold their crops to brokers who came directly to their fields. All of the buyers came to the farmers' fields and purchased the entire farm output of the farmers in Nweyit village. The yields are then harvested by those brokers according to their agreement during harvesting time. According to the responses, those brokers transported their crops to the Yangon market during the rainy season.

However, there were various buyers who purchased sweet corn in other villages. Almost half of farmers (45%) sold their entire farm production to brokers who came to them directly. Some farmers (25%) sold their products directly to the market. The remaining 16% and 14% of farmers sold their sweet corn to local retailers and wholesalers, respectively. The farmers in Nweyit village did not have to transport their products to the market. However, some farmers in other villages use the bullock cart, htawlargyi, and tricycle to transport their products to local retailers and wholesalers or directly to the market.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the data on overall sweet corn production in the eight townships of Nay Pyi Taw Council Area over six years, sweet corn production was the highest in Lewe township and second highest in Pobbathiri Township. The amount of sweet corn cultivated area, harvested area, and total sweet corn production slightly enhanced year by year in Nay Pyi Taw. According to the surveyed data of farmers’ perception on sweet corn cultivation, 74% and 55% of total respondent farmers in Nweyit village and other villages respectively wanted to produce the sweet corn all year because they can get more profits from the production than other crops.

According to findings of the marketing activities, farmers sold the crop with cash down payment system in other villages were higher than that system used in Nweyit village. On the other hand, the farmers sold with advanced payment (contract farming) in Nweyit village were higher than that system used in other villages. The study villages are main sweet corn producing areas where irrigation water is available by tube well and farmers are interesting to grow diversified crops for their income earning. Because sweet corn is the popular snack for the young customers and getting high profit therefore growing areas are increasing trend in Nay Pyi Taw. However, the sweet corn is just streamed and sold by mostly street vendors around the schools. There is no canning industry and value added enterprise for sweet corn in Nay Pyi Taw. Therefore, sweet corn market in the study area has high risk of price fluctuations.

Some farmers in the research area thought sweet corn is not considered as a profitable crop because the price of sweet corn is lower than that of other crops when schools are off in the summer season. Because of rising sweet corn demand as well as the expanding industrial corn uses and needs, there is a need to expand the existing sweet corn production sector. In order to do so, the government should provide sweet corn farmers with not only credit, adequate irrigation water, high-quality seeds, and inputs, but also post-harvest loss minimization technologies. Moreover, the government should also help small-scale business owners and farmers to be trained in food processing skills to produce sweet corn value-added foods.

Sweet corn market would be promoted via value added SME to be more attractive for the farmers as their existing willingness of sweet corn production. Additionally, sweet corn value-added product manufacturers will enhance sweet corn farmers' profits through the development of value-added enterprises. Moreover, contract farm practices, attractive investments for processing industry and logistic facilities are the critical factors for sweet corn sector development for all stake holders in Myanmar.

REFERENCES

Demaree, H. 2016. Myanmar corn production forecast to increase. Retrieved September 9, 2021, from World-Grain.com: https://www.world-grain.com/articles/7473-myanmar-corn-production-foreca...

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2016. Annual Report 2016, Division of Agricultural Extension, Department of Agriculture, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2020. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

Sailer, L. (2012, June 26). The Importance of Corn. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from Latham Hi-Tech Seeds: https://www.lathamseeds.com/2012/06/the-importance-of-corn/

Swe, K. L., & Swe, A. K. 2015. Promotion of Climate Resilience in Rice and Maize, Myanmar National Study, ASEAN-German Programme on Response to Climate Change.

VCC (Vegetable Conversion Chart). 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from Food Bank of Central New York: https://www.foodbankcny.org/assets/Documents/Vegetable-conversion-chart.pdf

WMPQ (World-Maize Production Quantity). 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from Knoema: https://knoema.com/atlas/topics/Agriculture/Crops-Production-Quantity-to...

Farmer’s Willingness to Grow Sweet Corn Production in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

ABSTRACT

In Myanmar, Shan State is the major sweet corn production area, and Nay Pyi Taw Council Area is one of the sweet corn growing places. Sweet corn is a potential crop to produce value-added products as a result of its increasing popularity as a preferred crop choice. Therefore, the purposes of the study are to investigate the sweet corn production trend and farmers’ willingness to grow sweet corn in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. The Department of Agriculture (DOA), MOALI, Nay Pyi Taw provided pertinent secondary statistics on sweet corn production. In May 2018, structured questionnaires were used to conduct a field study to 50 farmers from Nweyit village and 51 farmers from other villages by using random sampling. Based on the research findings, sweet corn production was greatest in Lewe Township and second highest in Pobbathiri Township over a six-year period, according to data on overall sweet corn production in the eight townships of the Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Year after year, the amount of sweet corn grown area, harvested area, and the total production in Nay Pyi Taw had increased to some extent. According to the research findings, nearly half of the sample farmers in other villages had completed secondary school, whereas only one-third of the sample respondents in Nweyit village had completed primary education. The predominant occupation of the total respondents in both study regions - Nweyit and other villages - was farmer, with almost half of total farmers in Nweyit village mostly growing sweet corn, compared to one-third of total farmers in other villages. In Nweyit village, three-quarters of total farmers considered that sweet corn production was economically favorable and desired to produce it all year, whereas in other villages, half of the farmers thought sweet corn production was economically attractive. In the study areas, most of the farmers sold their products to the brokers directly. In addition, when farmers sell their products, sweet corn production is less profitable than other comparative crops. As a result, some farmers have switched to producing other crops instead of sweet corn and have reduced sweet corn acreage. Therefore, if the government wants to encourage farmers to plant more sweet corn production, it needs to provide a good market for stable sweet corn prices, and food processing technologies to produce sweet corn processing foods. Contract farming practices, attractive investments for processing factory and logistic facility are the critical factors for sweet corn development for all stake holders in Myanmar.

Keywords: Comparative crops, economic feasibility, farmers, sweet corn, willingness to grow

INTRODUCTION

Sweet corn production in Myanmar

Corn is grown all around the world, though yields vary significantly, and it is the second most abundant cereal crop grown for human consumption. Corn is a highly adaptable crop, and everything on a corn plant can be used. Many populations, particularly in Africa, still eat corn as a primary food. The way corn is processed and consumed differs substantially from one country to the next. There is no waste from the part of the corn plant. Tamales are traditionally made with the husk of corn (Sailer, 2012). The kernels are used to make food, and the stalks are fed to animals, as well as the silks are used to make medicinal teas. In 2019, the world's corn production totaled 1,148 million tons. Moreover, the United States of America is the world's leading producer of corn. The United States of America produced 360,252 thousand tons of corn in 2020, accounting for 34.28% of global corn production. China, Brazil, Argentina, and Ukraine make up the top five countries, accounting for 74.86% of the total corn production (WMPQ, 2020).

In Myanmar, corn is also the second most significant cereal in Myanmar after rice, and it is farmed throughout the country (DOA, 2020). According to the secondary data from the Department of Agriculture in 2019-2020, the total sweet corn sown area in Myanmar was 309,192 hectares, and the total harvested area was 308,306 hectares. Moreover, the average total sweet corn yielded 7.2 tons per ha (1 ear = 0.00018 tons (VCC, 2016)), and the national sweet corn production was 2,316 thousand tons. The main sweet corn-producing areas in Myanmar are primarily found in the country's dry zones and hilly regions, with smaller production occurring in the delta and coastal areas. The main sweet corn crop is cultivated during the rainy season from May to June and harvested in August-September, particularly in the central dry zone and hilly regions.

About 90% of Myanmar's corn crop is grown in rain-fed areas. The majority (60-65%) of Myanmar’s corn production is exported to China. Furthermore, animal feed for domestic farms accounts for around 30-35% of Myanmar's maize supply, while seeds, food processing, and alcohol manufacture account for the remaining 5-6% (Demaree, 2016). Corn export supplies are often transported to Mandalay, Central Myanmar's largest wholesale market, and then carried to northeastern border towns including Muse, Chin Shwe Haw, Lwejel, and Kan Paiktee for export (Swe & Swe, 2015).

Nay Pyi Taw Region, located in the central dry zone areas, is one of the corn-growing zones, with a total area of 10,460 hectares planted in the rainy and winter seasons. Corn growers are divided into two categories: those who grow corn for animal feed and those who grow corn for human consumption. Corn seed growers for animal feed cover 7,439 hectares in the Nay Pyi Taw Region, while sweet corn growers for human use cover 3,020 hectares (DOA, 2016).

Sweet corn requires a high level of input, irrigation, and intensive pest management techniques. Improving the value-added production system of sweet corn due to the high cultivation costs is an important step towards increasing crop adoption. Sweet corn kernels can be used to make a variety of products, and they can be eaten fresh or cooked, frozen, canned, or juiced. Therefore, nowadays, sweet corn is one of the potential crops to produce value-added products because of its growing popularity by their good taste. Moreover, investment in the sweet corn canning industry is being interested in the feasibility and willingness of growth farmers in Nay Pyi Taw. Therefore, in the study, sweet corn was chosen as the main target crop to produce value-added products and the development of SME in the region.

Objectives of the study

METHODOLOGY

Study sites selection for data collection

There are eight administrative townships in Nay Pyi Taw Region. They are Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships. These all townships were chosen to observe the sweet corn production trend in Nay Pyi Taw Region. To study the second purpose of the research, Pobbathiri, Zeyarthiri, Lewe, and Tatkon Townships were randomly selected as the study sites because of the large amount of sweet corn grown in the area (DOA, 2017).

Data collection and analysis

In this study, both primary and secondary data were collected. The secondary data included yield, sown area, harvested area, total production of sweet corn in both monsoon and winter seasons. The relevant secondary data was accumulated from the Department of Agriculture (DOA), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation-MOALI, Nay Pyi Taw. The field survey was conducted in May 2018 to get the primary data. In the study areas, 9 village tracts and 11 sample villages were randomly selected, and 50 farmers from Nweyit village tract and 51 farmers from other village tracts were interviewed (Table 1).

Data were accumulated for the investigation of demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers, major crops grown by sample farmers, and perception of farmers on sweet corn production. The collected quantitative and qualitative data were first integrated into the Microsoft Excel program. Descriptive statistics methods such as mean, average, frequency, percentage were used to obtain results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sweet corn production trend in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory

In Nay Pyi Taw Region, the status of sweet corn production was the highest in 2017-2018 because of farmers' interest to produce value-added sweet corn products. The cultivated area and the harvested area of sweet corn in the region slightly increased from 2,575 ha in 2012-2013 to 3,481 ha in 2017-2018. Figure 1 shows the cultivated and harvested area and yield/ha of sweet corn for 6 years in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. In 2012-2013, the yield of sweet corn in the whole region was low, and it was 4.24 tons per hectare. Despite that, the yield/ha of sweet corn significantly improved in 2016-2017, and the yield was 5.00 tons/ha, but it was faintly decreased to 4.81 tons per hectare in 2017-2018.

During the crop season of 2012-2018, Lewe Township was the largest sweet corn producer out of eight townships in Nay Pyi Taw Region, and the sweet corn production in the township rose from about 5,548 tons in 2012-2013 to about 12,513 tons in 2017-2018. Moreover, Pobbathiri Township was the second-highest sweet corn production, and the corn production in the township peaked in 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. During the 2012-2016 planting season, there was no sweet corn production in Dekkhinathiri Township, but in 2017-2018 there was little corn production in that township. The total sweet corn production of the whole region significantly increased, and it was about 10,912 and 16,295 tons in 2012-2013 and 2017-2018 respectively. The conditions of total sweet corn production in Nay Pyi Taw Region and the corn production trend in each township are described in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Demographic characteristics of sample respondents

In this study, demographic characteristics of sample sweet corn farmers were gathered by using structured questionnaires. That information is presented in Table 3. In total, the gender ratio of the sample farmers in the study area was 63 male: 38 female, and the average value of sample respondents’ age was 47 years with a range of a minimum of 17 years to a maximum of 74 years.

The educational percentages of the sample farmers in Nweyit village were 2% (illiterate), 8% (monastery), 66% (primary), 14% (secondary), 8% (high school) and 2% (university). In other villages, the percentages of educational levels of sample respondents were 1.96%, 1.96%, 29.41%, 41.18%, 15.69%, and 9.8% for illiterate, monastery, primary school, middle school, high school, and university in turn. Based on the results, it was found that almost half of the sample farmers in other villages received secondary education, and one-third of the sample respondents in Nweyit village had primary education.

Depending on the results of the survey, the average farming experience of the total sample respondents in the study was 27 years, ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 60 years. In both study areas, the main occupations of all respondents from Nweyit village and other villages were farmers. The average total numbers of household sizes in the study area were 5, and the maximum and minimum household sizes were 15 and 1, respectively. In addition, the average family worker involved in crop production of all total respondents was 2, with a range of a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 8.

Farm information and major crops of sample farmers

In Table 4, the average farm size of total farmers in the study area was 2.83 hectares with a range of a minimum of 0.40 ha to a maximum of 13.77 ha. In detail, the average farm size of the respondents in Nweyit village was 1.62 ha, and the average farm size of the respondents in other villages was 3.64 ha.

According to the surveyed data, the main crops grown by sample farmers in Nweyit village were sweet corn, vegetables, pulses, rice, CP corn, and fruits. Among these crops, sweet corn (40.98%) was the priority crop, followed by vegetables (32.79%) and pulses (16.39%). In the other villages, the farmers planted sweet corn as the main crop. The sample respondents from other villages planted 10 different crops. Of these, sweet corn (34%), pulses (20.67%), and rice (16.67%) were cultivated (Table 5).

Farmers’ willingness to grow sweet corn production

The perspectives of farmers on sweet corn production were described in Table 6. The total farmers (64.36%) in the study areas thought sweet corn was an economically attractive crop compared to other cash crops, and most farmers in Nweyit village (74%) and other villages (55%) had the willingness to grow in their farms. But, 23.76% of the farmers answered that they do not want to plant sweet corn all year round because its production was not economically attractive. Moreover, only a few farmers (11.88%) perceived the sweet corn was a non-profit crop, and they do not have any desire to produce it in their fields. Regarding the perception of the number of sweet corn production per year, farmers in Nweyit village and other villages would like to produce sweet corn at least once and up to three times a year, but most of them preferred to grow sweet corn twice a year. The farmers (41.58%) in the surveyed areas could produce sweet corn twice a year. In addition, the farmers were possible to grow sweet corn only once a year (22.77%) and three times a year (35.64%).

Marketing Activities of Sweet Corn Farmers

Table 7 depicts the sweet corn farmers' marketing activities, such as the types of sales, buyers, and modes of transportation. In Nweyit village, 68% of total farmers sold sweet corn with a cash down payment system, while 24% sold with advanced payment, and 8% with credit. In other villages, the majority of farmers (92%) sold sweet corn with a cash down payment system. A few farmers sold the crop with advanced payment (6%), and credit (2%) in turn.

According to the types of buyers, all of the farmers in Nweyit village sold their crops to brokers who came directly to their fields. All of the buyers came to the farmers' fields and purchased the entire farm output of the farmers in Nweyit village. The yields are then harvested by those brokers according to their agreement during harvesting time. According to the responses, those brokers transported their crops to the Yangon market during the rainy season.

However, there were various buyers who purchased sweet corn in other villages. Almost half of farmers (45%) sold their entire farm production to brokers who came to them directly. Some farmers (25%) sold their products directly to the market. The remaining 16% and 14% of farmers sold their sweet corn to local retailers and wholesalers, respectively. The farmers in Nweyit village did not have to transport their products to the market. However, some farmers in other villages use the bullock cart, htawlargyi, and tricycle to transport their products to local retailers and wholesalers or directly to the market.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the data on overall sweet corn production in the eight townships of Nay Pyi Taw Council Area over six years, sweet corn production was the highest in Lewe township and second highest in Pobbathiri Township. The amount of sweet corn cultivated area, harvested area, and total sweet corn production slightly enhanced year by year in Nay Pyi Taw. According to the surveyed data of farmers’ perception on sweet corn cultivation, 74% and 55% of total respondent farmers in Nweyit village and other villages respectively wanted to produce the sweet corn all year because they can get more profits from the production than other crops.

According to findings of the marketing activities, farmers sold the crop with cash down payment system in other villages were higher than that system used in Nweyit village. On the other hand, the farmers sold with advanced payment (contract farming) in Nweyit village were higher than that system used in other villages. The study villages are main sweet corn producing areas where irrigation water is available by tube well and farmers are interesting to grow diversified crops for their income earning. Because sweet corn is the popular snack for the young customers and getting high profit therefore growing areas are increasing trend in Nay Pyi Taw. However, the sweet corn is just streamed and sold by mostly street vendors around the schools. There is no canning industry and value added enterprise for sweet corn in Nay Pyi Taw. Therefore, sweet corn market in the study area has high risk of price fluctuations.

Some farmers in the research area thought sweet corn is not considered as a profitable crop because the price of sweet corn is lower than that of other crops when schools are off in the summer season. Because of rising sweet corn demand as well as the expanding industrial corn uses and needs, there is a need to expand the existing sweet corn production sector. In order to do so, the government should provide sweet corn farmers with not only credit, adequate irrigation water, high-quality seeds, and inputs, but also post-harvest loss minimization technologies. Moreover, the government should also help small-scale business owners and farmers to be trained in food processing skills to produce sweet corn value-added foods.

Sweet corn market would be promoted via value added SME to be more attractive for the farmers as their existing willingness of sweet corn production. Additionally, sweet corn value-added product manufacturers will enhance sweet corn farmers' profits through the development of value-added enterprises. Moreover, contract farm practices, attractive investments for processing industry and logistic facilities are the critical factors for sweet corn sector development for all stake holders in Myanmar.

REFERENCES

Demaree, H. 2016. Myanmar corn production forecast to increase. Retrieved September 9, 2021, from World-Grain.com: https://www.world-grain.com/articles/7473-myanmar-corn-production-foreca...

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2016. Annual Report 2016, Division of Agricultural Extension, Department of Agriculture, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2020. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

Sailer, L. (2012, June 26). The Importance of Corn. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from Latham Hi-Tech Seeds: https://www.lathamseeds.com/2012/06/the-importance-of-corn/

Swe, K. L., & Swe, A. K. 2015. Promotion of Climate Resilience in Rice and Maize, Myanmar National Study, ASEAN-German Programme on Response to Climate Change.

VCC (Vegetable Conversion Chart). 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from Food Bank of Central New York: https://www.foodbankcny.org/assets/Documents/Vegetable-conversion-chart.pdf

WMPQ (World-Maize Production Quantity). 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from Knoema: https://knoema.com/atlas/topics/Agriculture/Crops-Production-Quantity-to...