ABSTRACT

Myanmar's second most significant cereal crop after rice is corn, and it is farmed all around the country. Corn is used for both export and country consumption (animal feed and food processing). However, there is a scarcity of study on the cost and profitability of sweet corn production in Myanmar. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to look into the profitability of sweet corn production and the benefits and drawbacks of growing sweet corn in the Nay Pyi Taw Region. In May 2018, 50 farmers from Nweyit village and 51 farmers from other villages were randomly sampled for a field survey utilizing structured questionnaires. Based on the findings of the study, the majority of the total respondents learned primary school. Farmers were the most common occupation among total respondents in both study locations - Nweyit and other villages - while secondary jobs such as broker, merchant, and agricultural labor were plentiful. Sweet corn is grown by 40.98% of total farmers in Nweyit, compared to 34% of total farmers in other villages. According to the cost and return calculations for sweet corn production, sweet corn farmers in Nweyit had a benefit-cost ratio of 2.02, which was greater than farmers in other villages who had 1.79. As a result, it can be stated that by planting sweet corn in the research regions, farmers in Nweyit made more profit than farmers in other villages. In Nweyit village, there were no harvesting costs because all farmers sold their whole field yield to brokers who came directly to the field. But, farmers in other villages have had to pay for harvesting costs since they did not have access to a broker who came directly to their farms. Regarding the opportunity and constraint of sweet corn production, the majority of the farmers in both villages said they could grow the crop every season and they obtained poor output prices and demand while selling sweet corn. Therefore, the government should link sweet corn production and marketing channels to get the good prices for sweet corn farmers and to maintain the good quality of sweet corn for consumers. Moreover, the government should educate sweet corn growers about alternative cropping patterns and the crops that can be cultivated with sweet corn. As a result, farmers will be able to get their extra income and transition to sustainable agriculture without depleting the soil's nutrients.

Keywords: Sweet Corn, cost and benefit, sustainable agriculture, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Sweet corn production in Myanmar

Corn (Zea mays L.), the most adaptable cereal crop, is the world's second most extensively farmed crop and cultivated in the tropics, subtropics, and temperate climates. It comes in a variety of varieties such as field corn, sweet corn, and baby corn (WMS, 2020). Corn is vital for billions of people as food, feed, and industrial raw resource. In 2019, over 170 nations produced roughly 1,148 million metric tons (MT) of corn on an area of 197 million ha, with average productivity of 5.82 MT/ha (FAOSTAT, 2020).

Corn is utilized as animal feed in Myanmar, both for domestic and export purposes. About half of Myanmar's corn production is shipped to China via Muse, while the remaining 40% is consumed domestically (Htwe, 2020). Around 30-35% of Myanmar's corn output goes to animal feed, with the remaining 5-6 % going to seeds, food processing, and alcohol production. Corn is Myanmar's second most important cereal crop after rice, and it is grown throughout the nation, with the Sagaing Region producing the majority of the country's sweet corn (DOA, 2020).

In 2019-2020, Myanmar's sweet corn sown and harvested areas were 309,192 hectares and 308,306 hectares, in turn, with an average total sweet corn yield of 7.6 tons per ha (1 ear = 0.00018 ton, (VCC, 2016)). Moreover, the national production of sweet corn was 2,316 thousand tons in 2019 (DOA, 2020). Sweet corn was grown on 3,557 hectares and harvested at the same hectares in the Nay Pyi Taw. Furthermore, the Nay Pyi Taw's sweet corn yield and production amounts were 5.02 tons per ha and 17 thousand tons, in turn (DOA, 2020).

In the monsoon and winter seasons, the Nay Pyi Taw is one of the sweet corn most growing zones, with a total area of 3,557 ha planted (DOA, 2020). Investment in sweet corn canning factory and contract farming for sweet corn is being interested by enterprising company to implement in Nay Pyi Taw Region. Therefore, Nay Pyi Taw Region was chosen as the reference site for cost and benefit analysis of sweet corn production in the study. The costs and profits of sweet corn production will be different in various places and will be changed depending on several factors, for instance, land preparation cost, hired labor cost, harvesting cost, and so on. However, there are limited research works on sweet corn production cost and profitability. Therefore, it is needed to implement those kinds of research to find out that if this crop is profitable and whether it should continue to be grown in the coming years. Furthermore, the limitations and advantages of sweet corn production should also be investigated.

Objectives of the study

- To estimate the benefits and costs of sweet corn production in Nay Pyi Taw

- To know the opportunities and limitations of sweet corn production of selected farmers in the study area

METHODOLOGY

Study site selection for data collection

Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships are eight administrative townships in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Pobbathiri, Zeyarthiri, Lewe, and Tatkon Townships in Nay Pyi Taw were chosen as the study sites because there are many sweet corn cultivation acres in the study areas (DOA, 2017). Nine village tracts and 11 sample villages were randomly selected from the study areas.

Data collection and analysis

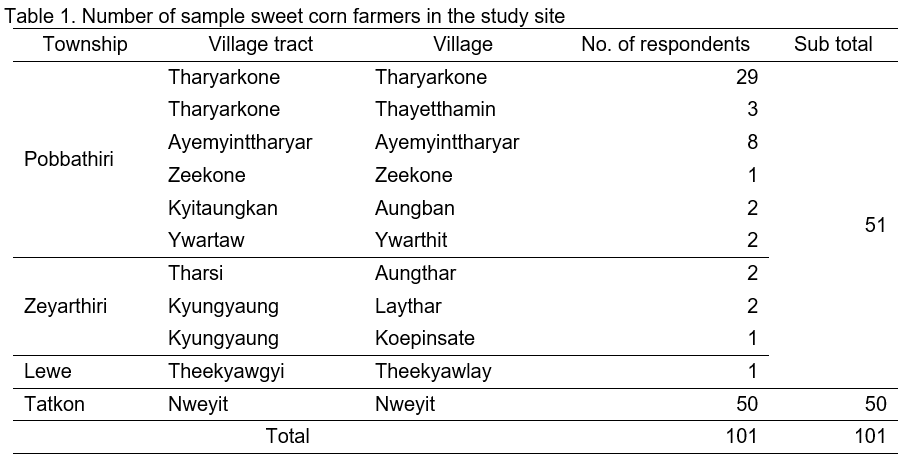

Primary data were collected for analysis, and in the survey, 51 respondents from other village tracts and 50 respondents from Nweyit village were interviewed in May 2018. Therefore, the total sample size in the research was 101 farmers, and the numbers of sample farmers in the study sites are described in Table 1. Data were collected for the examination of demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers, constraints and opportunities of sweet corn production, and benefits and costs of sweet corn cultivation.

The accumulated data were digitally aggregated into a defined format, and the data were analyzed via Microsoft Excel and Stata Software to get the results. In this study, descriptive statistics and benefit-cost analysis were utilized to determine the socio-economic profile of farmers and the profitability of sweet corn farmers in the study areas in turn. A benefit-cost analysis (B/C Ratio) was performed after determining the entire variable cost and gross return from sweet corn production. The total cost of production was calculated by adding all of the production's variable cost items. Income from product sales was taken into account while computing gross return. As a result, the benefit-cost analysis was carried out using the following formula:

B/C Ratio = Gross return / total variable cost (Upadhyaya et al., 2020) where,

Gross return = Total quantity of sweet corn sold (Corn) × Price per unit of corn (Kyat)

Total variable costs = Summation of all variable cost items

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers

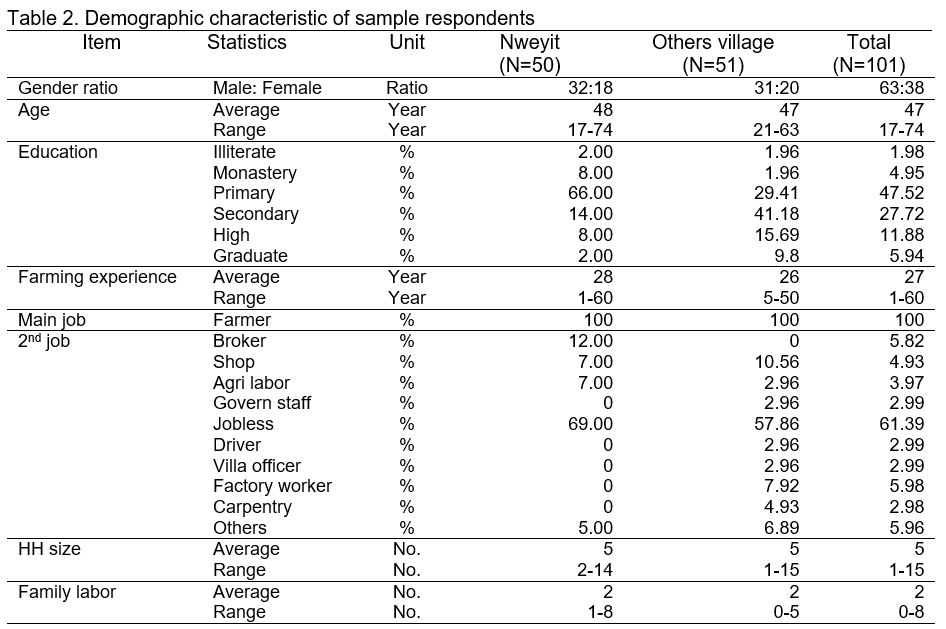

Table 2 showed the demographic characteristics of sample farmers obtained in the research area using structured questionnaires. The gender proportion of the total sample respondents was 63 males: 38 females in the research area. The average age of the responders was 47 years, with a range of 17 to 74 years in total. According to the survey's findings, 1.98% of the total respondents were illiterate, 4.95% were monastery education, 47.52% were in primary school, 27.72% were in secondary school, 11.88% were in high school, and 5.94% were in university. The majority of the total respondents learned primary education. According to the data, the total respondents' average agricultural experience was 27 years, with a range of 1 to 60 years.

Farmers were the primary occupation of the total respondents in both study villages - Nweyit and others. On the other hand, secondary jobs were plentiful. Brokers accounted for 12% of minor jobs in Nweyit village, while shopkeepers 7%, agricultural labor 7%, jobless 69%, and other minor occupations 5%. Shopkeeper (10.56%), agricultural labor (2.96%), government staff (2.96%), jobless (57.86%), driver (2.96%), village officer (2.96%), factory worker (7.92%), carpentry (4.93%) and other minor occupations (6.89%) were the minor occupations in other villages. The respondents in Nweyit village had an average household size of 5, ranging from 2 to 14, and the average number of family members working in agricultural cultivation was 2, with a range of 1 to 8. According to the collected data, the respondents' average household size was 5, ranging from 1 to 15 in other villages. In other villages, family labor was used in crop farming, and the average number of the family labor was also 2, with a range of 0 to 5.

Farm and major crops information of sample farmers

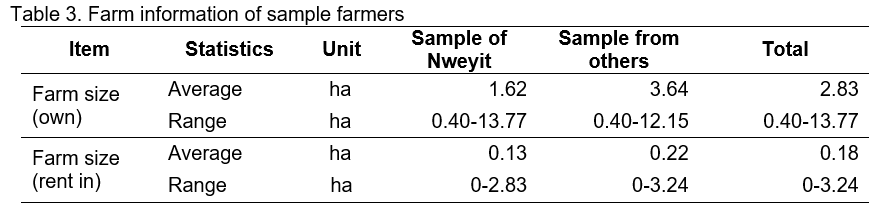

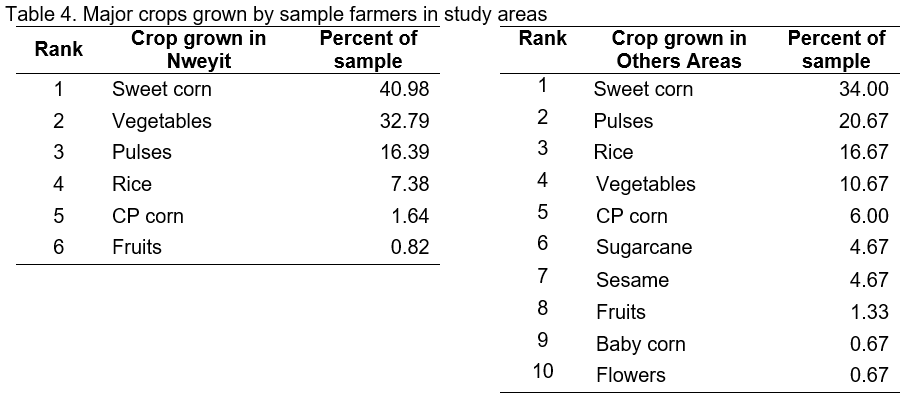

Table 3 showed that the respondents' average farm size (own) was 1.62 ha, with a range of 0.40 ha to 13.77 ha in Nweyit village. Moreover, the average farm size (rent-in) in the village was 0.13 ha which ranges from 0 to 2.83 ha. While the average farm size (own) in other villages was 3.64 ha, ranging from 0.40 ha to 12.15 ha, the average farm size (rent-in) was 0.22 ha, with a range of a minimum of 0 ha to a maximum of 3.24 ha. In Table 4, it was found that sweet corn (40.98%), vegetables (32.79%), and pulses (16.39%) were the main crops planted by sample farmers in Nweyit village, according to the data. Farmers in the other villages also grew sweet corn (34%) as their major crop, followed by lentils (20.67%) and rice (16.67%).

Benefit-cost analysis for sweet corn production

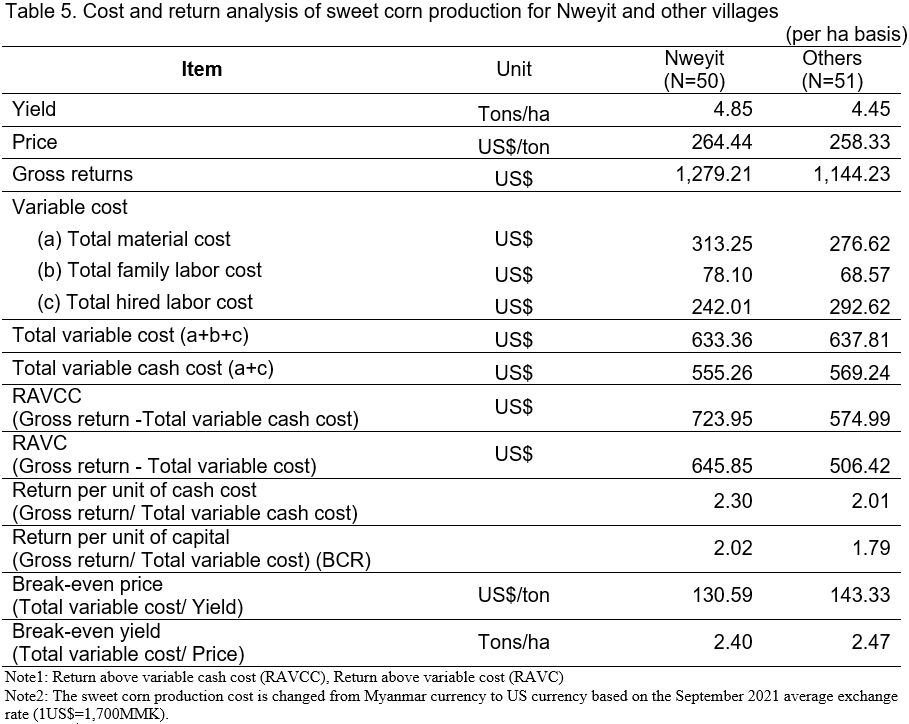

Table 5 showed the enterprise budget for sweet corn cultivation among the Nweyit and other villages. Nweyit village’s total variable cost of sweet corn production (US$633.36/ha) was lower than that of other villages (US$637.81/ha). Farmers in Nweyit village and other villages harvested 4.85 tons and 4.45 tons of corns per ha, respectively. Furthermore, the price of sweet corn (US$264.44/ton) in Nweyit was higher than in other villages (US$258.33/ton).

Sweet corn growers in Nweyit had higher total material costs and total family labor costs than farmers in other villages. However, the cost of hired labor in other villages was higher than in Nweyit village. Sweet corn cultivation had a Return above Variable Cash Cost-RAVCC of US$723.95/ha in Nweyit and US$574.99/ha in other villages. Nweyit's Return above Variable Cost - RAVC was US$645.85/ha, whereas other villages' RAVC was US$506.42/ha. The benefit-cost ratio of 2.02 acquired by sweet corn farmers in Nweyit village was higher than that of 1.79 obtained by farmers in other villages.

As a result, it can be stated that by planting sweet corn in the research areas, farmers in Nweyit obtained more profit than farmers in other villages. Farmers in Nweyit received a higher yield than farmers in other villages, which resulted in a better profit. Although the corn selling prices of Nweyit and other villages were similar, the total variable costs of other villages were greater than those of Nweyit village. Therefore, the sweet corn farmers from Nweyit and other villages obtained varied profits. It's worth noting that there were no harvesting costs in Nweyit village because all farmers sold their entire field yield to brokers who came straight to the field. The brokers then use their arrangement to harvest the sweet corn crop.

A crop's break-even price is the amount a farmer should get for his commodity in order to offset variable cash costs. According to the data in Table 5, the break-even price of sweet corn in Nweyit and other villages were US$130.59/ton and US$143.33/ton, respectively. At the same time, the average market price of sweet corn in Nweyit and other villages was approximately US$260/ton. Therefore, it can be concluded that the sweet corn farmers in the study area obtained net profits from their farms. Break-even yield is the amount of yield that a farmer should make in order to cover his or her production costs. To cover up the cost of production, the break-even yield of sweet corn in Nweyit was 2.40 tons/ha and that in other villages was 2.47 tons/ha. At that moment, the actual sweet corn yield in Nweyit and other villages were twice as high as the break-even yield of sweet corn. Thus, it can say that the yield of sweet corn farmers can cover their production costs.

Constraints and opportunities of sweet corn production

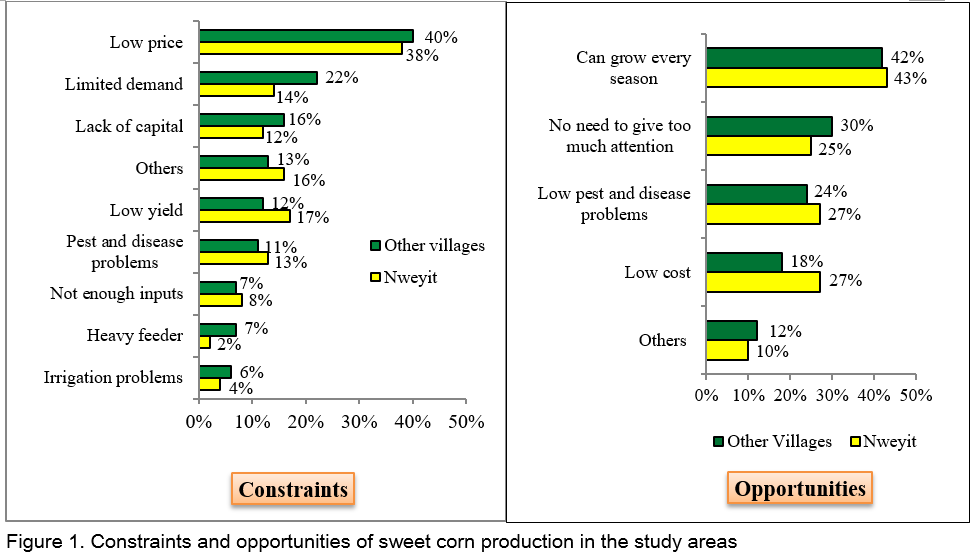

Farmers’ constraints and opportunities for sweet corn production are presented in Figure 1. Around 40% of all farmers in both study sites answered low output price while selling their sweet corn. The problem of limited demand was experienced by 14% of all farmers in Nweyit village, compared to 22% of total farmers in other villages. In other villages, some farmers faced challenges such as a shortage of capital (16%), low yield (12%), insect and disease problems (11%), not enough inputs (7%), heavy feeder (7%), and irrigation issues (6%). In Newyit village, 12%, 17%, 13%, 8%, 2%, and 4% of the sample respondents had suffered the constraints of sweet corn production as lack of capital, low yield, insect and disease problems, insufficient inputs, heavy feeder, and irrigation problems, respectively.

When asked about the benefits of cultivating sweet corn, over 40% of farmers in all study areas said that sweet corn can be grown at any time of year. Moreover, about 25% and 30% of total farmers in Nweyit and other villages mentioned that sweet corn growing did not require special care. Farmers in Nweyit village saw low pest and disease incidence problems (27%) and low production cost (27%) as opportunities, compared to low pest and disease incidence problems (24%) and low cost (18%) in other villages. In Nweyit and other villages, over 10% of total farmers said that there were other sweet corn-growing pros and cons.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the benefit-cost analysis for sweet corn production, sweet corn farmers in Nweyit village had a ratio of 2.02, which was greater than farmers in other villages who had 1.79. As a result, it can be concluded that by planting sweet corn in the research areas, farmers in Nweyit made more profit than farmers in other villages. According to the surveyed data, most of the farmers in the study area answered sweet corn can be grown at any time of year. However, it was found that the sweet corn farmers in other villages are more suffering from the constraints of production than those in Nweyit village. Furthermore, the majority of the farmers in both villages obtained low price and demand in selling sweet corn because of market uncertainty.

Therefore, the government should link production and marketing channel because sweet corn needs to be manufactured immediately to maintain product's quality. Only then will farmers be able to get good prices for their products and get good quality products for consumers without wastage in between. But, it is important to note that sweet corn is one of the heavy feeder plants and it should not be continuously grown in the same field. Therefore, the government should educate sweet corn growers about the crops that can be grown with sweet corn and its alternative cropping patterns. As a result, farmers will be able to earn extra income and move on to sustainable agriculture without running out of nutrients from the soil.

REFERENCES

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2020. Official Report: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

FAOSTAT (Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division). 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from FAOSTAT: Production of maize in 2018: Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity.

Htwe, K. K. (2020). Maize market paper-final, Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339900261_Maize_market_paper-final

Upadhyaya, S., Adhikari, R. K., Karki, L., & Singh, O. 2020. Production and Marketing of Ginger: A Case Study in Salyan District, Nepal. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 5(4).

VCC (Vegetable Conversion Chart). 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from Food Bank of Central New York: https://www.foodbankcny.org/assets/Documents/Vegetable-conversion-chart.pdf

WMS (World Maze Scenario). 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from ICAR-Indian Institute of Maize Research: https://iimr.icar.gov.in/world-maze-scenario

Cost and Benefit Analysis of Sweet Corn Production in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

ABSTRACT

Myanmar's second most significant cereal crop after rice is corn, and it is farmed all around the country. Corn is used for both export and country consumption (animal feed and food processing). However, there is a scarcity of study on the cost and profitability of sweet corn production in Myanmar. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to look into the profitability of sweet corn production and the benefits and drawbacks of growing sweet corn in the Nay Pyi Taw Region. In May 2018, 50 farmers from Nweyit village and 51 farmers from other villages were randomly sampled for a field survey utilizing structured questionnaires. Based on the findings of the study, the majority of the total respondents learned primary school. Farmers were the most common occupation among total respondents in both study locations - Nweyit and other villages - while secondary jobs such as broker, merchant, and agricultural labor were plentiful. Sweet corn is grown by 40.98% of total farmers in Nweyit, compared to 34% of total farmers in other villages. According to the cost and return calculations for sweet corn production, sweet corn farmers in Nweyit had a benefit-cost ratio of 2.02, which was greater than farmers in other villages who had 1.79. As a result, it can be stated that by planting sweet corn in the research regions, farmers in Nweyit made more profit than farmers in other villages. In Nweyit village, there were no harvesting costs because all farmers sold their whole field yield to brokers who came directly to the field. But, farmers in other villages have had to pay for harvesting costs since they did not have access to a broker who came directly to their farms. Regarding the opportunity and constraint of sweet corn production, the majority of the farmers in both villages said they could grow the crop every season and they obtained poor output prices and demand while selling sweet corn. Therefore, the government should link sweet corn production and marketing channels to get the good prices for sweet corn farmers and to maintain the good quality of sweet corn for consumers. Moreover, the government should educate sweet corn growers about alternative cropping patterns and the crops that can be cultivated with sweet corn. As a result, farmers will be able to get their extra income and transition to sustainable agriculture without depleting the soil's nutrients.

Keywords: Sweet Corn, cost and benefit, sustainable agriculture, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Sweet corn production in Myanmar

Corn (Zea mays L.), the most adaptable cereal crop, is the world's second most extensively farmed crop and cultivated in the tropics, subtropics, and temperate climates. It comes in a variety of varieties such as field corn, sweet corn, and baby corn (WMS, 2020). Corn is vital for billions of people as food, feed, and industrial raw resource. In 2019, over 170 nations produced roughly 1,148 million metric tons (MT) of corn on an area of 197 million ha, with average productivity of 5.82 MT/ha (FAOSTAT, 2020).

Corn is utilized as animal feed in Myanmar, both for domestic and export purposes. About half of Myanmar's corn production is shipped to China via Muse, while the remaining 40% is consumed domestically (Htwe, 2020). Around 30-35% of Myanmar's corn output goes to animal feed, with the remaining 5-6 % going to seeds, food processing, and alcohol production. Corn is Myanmar's second most important cereal crop after rice, and it is grown throughout the nation, with the Sagaing Region producing the majority of the country's sweet corn (DOA, 2020).

In 2019-2020, Myanmar's sweet corn sown and harvested areas were 309,192 hectares and 308,306 hectares, in turn, with an average total sweet corn yield of 7.6 tons per ha (1 ear = 0.00018 ton, (VCC, 2016)). Moreover, the national production of sweet corn was 2,316 thousand tons in 2019 (DOA, 2020). Sweet corn was grown on 3,557 hectares and harvested at the same hectares in the Nay Pyi Taw. Furthermore, the Nay Pyi Taw's sweet corn yield and production amounts were 5.02 tons per ha and 17 thousand tons, in turn (DOA, 2020).

In the monsoon and winter seasons, the Nay Pyi Taw is one of the sweet corn most growing zones, with a total area of 3,557 ha planted (DOA, 2020). Investment in sweet corn canning factory and contract farming for sweet corn is being interested by enterprising company to implement in Nay Pyi Taw Region. Therefore, Nay Pyi Taw Region was chosen as the reference site for cost and benefit analysis of sweet corn production in the study. The costs and profits of sweet corn production will be different in various places and will be changed depending on several factors, for instance, land preparation cost, hired labor cost, harvesting cost, and so on. However, there are limited research works on sweet corn production cost and profitability. Therefore, it is needed to implement those kinds of research to find out that if this crop is profitable and whether it should continue to be grown in the coming years. Furthermore, the limitations and advantages of sweet corn production should also be investigated.

Objectives of the study

METHODOLOGY

Study site selection for data collection

Pyinmana, Lewe, Tatkon, Ottarathiri, Dekkhinathiri, Pobbathiri, Zabuthiri, and Zeyarthiri Townships are eight administrative townships in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area. Pobbathiri, Zeyarthiri, Lewe, and Tatkon Townships in Nay Pyi Taw were chosen as the study sites because there are many sweet corn cultivation acres in the study areas (DOA, 2017). Nine village tracts and 11 sample villages were randomly selected from the study areas.

Data collection and analysis

Primary data were collected for analysis, and in the survey, 51 respondents from other village tracts and 50 respondents from Nweyit village were interviewed in May 2018. Therefore, the total sample size in the research was 101 farmers, and the numbers of sample farmers in the study sites are described in Table 1. Data were collected for the examination of demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers, constraints and opportunities of sweet corn production, and benefits and costs of sweet corn cultivation.

The accumulated data were digitally aggregated into a defined format, and the data were analyzed via Microsoft Excel and Stata Software to get the results. In this study, descriptive statistics and benefit-cost analysis were utilized to determine the socio-economic profile of farmers and the profitability of sweet corn farmers in the study areas in turn. A benefit-cost analysis (B/C Ratio) was performed after determining the entire variable cost and gross return from sweet corn production. The total cost of production was calculated by adding all of the production's variable cost items. Income from product sales was taken into account while computing gross return. As a result, the benefit-cost analysis was carried out using the following formula:

B/C Ratio = Gross return / total variable cost (Upadhyaya et al., 2020) where,

Gross return = Total quantity of sweet corn sold (Corn) × Price per unit of corn (Kyat)

Total variable costs = Summation of all variable cost items

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic and farm characteristics of sample farmers

Table 2 showed the demographic characteristics of sample farmers obtained in the research area using structured questionnaires. The gender proportion of the total sample respondents was 63 males: 38 females in the research area. The average age of the responders was 47 years, with a range of 17 to 74 years in total. According to the survey's findings, 1.98% of the total respondents were illiterate, 4.95% were monastery education, 47.52% were in primary school, 27.72% were in secondary school, 11.88% were in high school, and 5.94% were in university. The majority of the total respondents learned primary education. According to the data, the total respondents' average agricultural experience was 27 years, with a range of 1 to 60 years.

Farmers were the primary occupation of the total respondents in both study villages - Nweyit and others. On the other hand, secondary jobs were plentiful. Brokers accounted for 12% of minor jobs in Nweyit village, while shopkeepers 7%, agricultural labor 7%, jobless 69%, and other minor occupations 5%. Shopkeeper (10.56%), agricultural labor (2.96%), government staff (2.96%), jobless (57.86%), driver (2.96%), village officer (2.96%), factory worker (7.92%), carpentry (4.93%) and other minor occupations (6.89%) were the minor occupations in other villages. The respondents in Nweyit village had an average household size of 5, ranging from 2 to 14, and the average number of family members working in agricultural cultivation was 2, with a range of 1 to 8. According to the collected data, the respondents' average household size was 5, ranging from 1 to 15 in other villages. In other villages, family labor was used in crop farming, and the average number of the family labor was also 2, with a range of 0 to 5.

Farm and major crops information of sample farmers

Table 3 showed that the respondents' average farm size (own) was 1.62 ha, with a range of 0.40 ha to 13.77 ha in Nweyit village. Moreover, the average farm size (rent-in) in the village was 0.13 ha which ranges from 0 to 2.83 ha. While the average farm size (own) in other villages was 3.64 ha, ranging from 0.40 ha to 12.15 ha, the average farm size (rent-in) was 0.22 ha, with a range of a minimum of 0 ha to a maximum of 3.24 ha. In Table 4, it was found that sweet corn (40.98%), vegetables (32.79%), and pulses (16.39%) were the main crops planted by sample farmers in Nweyit village, according to the data. Farmers in the other villages also grew sweet corn (34%) as their major crop, followed by lentils (20.67%) and rice (16.67%).

Benefit-cost analysis for sweet corn production

Table 5 showed the enterprise budget for sweet corn cultivation among the Nweyit and other villages. Nweyit village’s total variable cost of sweet corn production (US$633.36/ha) was lower than that of other villages (US$637.81/ha). Farmers in Nweyit village and other villages harvested 4.85 tons and 4.45 tons of corns per ha, respectively. Furthermore, the price of sweet corn (US$264.44/ton) in Nweyit was higher than in other villages (US$258.33/ton).

Sweet corn growers in Nweyit had higher total material costs and total family labor costs than farmers in other villages. However, the cost of hired labor in other villages was higher than in Nweyit village. Sweet corn cultivation had a Return above Variable Cash Cost-RAVCC of US$723.95/ha in Nweyit and US$574.99/ha in other villages. Nweyit's Return above Variable Cost - RAVC was US$645.85/ha, whereas other villages' RAVC was US$506.42/ha. The benefit-cost ratio of 2.02 acquired by sweet corn farmers in Nweyit village was higher than that of 1.79 obtained by farmers in other villages.

As a result, it can be stated that by planting sweet corn in the research areas, farmers in Nweyit obtained more profit than farmers in other villages. Farmers in Nweyit received a higher yield than farmers in other villages, which resulted in a better profit. Although the corn selling prices of Nweyit and other villages were similar, the total variable costs of other villages were greater than those of Nweyit village. Therefore, the sweet corn farmers from Nweyit and other villages obtained varied profits. It's worth noting that there were no harvesting costs in Nweyit village because all farmers sold their entire field yield to brokers who came straight to the field. The brokers then use their arrangement to harvest the sweet corn crop.

A crop's break-even price is the amount a farmer should get for his commodity in order to offset variable cash costs. According to the data in Table 5, the break-even price of sweet corn in Nweyit and other villages were US$130.59/ton and US$143.33/ton, respectively. At the same time, the average market price of sweet corn in Nweyit and other villages was approximately US$260/ton. Therefore, it can be concluded that the sweet corn farmers in the study area obtained net profits from their farms. Break-even yield is the amount of yield that a farmer should make in order to cover his or her production costs. To cover up the cost of production, the break-even yield of sweet corn in Nweyit was 2.40 tons/ha and that in other villages was 2.47 tons/ha. At that moment, the actual sweet corn yield in Nweyit and other villages were twice as high as the break-even yield of sweet corn. Thus, it can say that the yield of sweet corn farmers can cover their production costs.

Constraints and opportunities of sweet corn production

Farmers’ constraints and opportunities for sweet corn production are presented in Figure 1. Around 40% of all farmers in both study sites answered low output price while selling their sweet corn. The problem of limited demand was experienced by 14% of all farmers in Nweyit village, compared to 22% of total farmers in other villages. In other villages, some farmers faced challenges such as a shortage of capital (16%), low yield (12%), insect and disease problems (11%), not enough inputs (7%), heavy feeder (7%), and irrigation issues (6%). In Newyit village, 12%, 17%, 13%, 8%, 2%, and 4% of the sample respondents had suffered the constraints of sweet corn production as lack of capital, low yield, insect and disease problems, insufficient inputs, heavy feeder, and irrigation problems, respectively.

When asked about the benefits of cultivating sweet corn, over 40% of farmers in all study areas said that sweet corn can be grown at any time of year. Moreover, about 25% and 30% of total farmers in Nweyit and other villages mentioned that sweet corn growing did not require special care. Farmers in Nweyit village saw low pest and disease incidence problems (27%) and low production cost (27%) as opportunities, compared to low pest and disease incidence problems (24%) and low cost (18%) in other villages. In Nweyit and other villages, over 10% of total farmers said that there were other sweet corn-growing pros and cons.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

According to the benefit-cost analysis for sweet corn production, sweet corn farmers in Nweyit village had a ratio of 2.02, which was greater than farmers in other villages who had 1.79. As a result, it can be concluded that by planting sweet corn in the research areas, farmers in Nweyit made more profit than farmers in other villages. According to the surveyed data, most of the farmers in the study area answered sweet corn can be grown at any time of year. However, it was found that the sweet corn farmers in other villages are more suffering from the constraints of production than those in Nweyit village. Furthermore, the majority of the farmers in both villages obtained low price and demand in selling sweet corn because of market uncertainty.

Therefore, the government should link production and marketing channel because sweet corn needs to be manufactured immediately to maintain product's quality. Only then will farmers be able to get good prices for their products and get good quality products for consumers without wastage in between. But, it is important to note that sweet corn is one of the heavy feeder plants and it should not be continuously grown in the same field. Therefore, the government should educate sweet corn growers about the crops that can be grown with sweet corn and its alternative cropping patterns. As a result, farmers will be able to earn extra income and move on to sustainable agriculture without running out of nutrients from the soil.

REFERENCES

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

DOA (Department of Agriculture). 2020. Official Report: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

FAOSTAT (Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division). 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from FAOSTAT: Production of maize in 2018: Crops/World Regions/Production Quantity.

Htwe, K. K. (2020). Maize market paper-final, Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339900261_Maize_market_paper-final

Upadhyaya, S., Adhikari, R. K., Karki, L., & Singh, O. 2020. Production and Marketing of Ginger: A Case Study in Salyan District, Nepal. International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, 5(4).

VCC (Vegetable Conversion Chart). 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2021, from Food Bank of Central New York: https://www.foodbankcny.org/assets/Documents/Vegetable-conversion-chart.pdf

WMS (World Maze Scenario). 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from ICAR-Indian Institute of Maize Research: https://iimr.icar.gov.in/world-maze-scenario