ABSTRACT

Taiwan’s rich biodiversity stems from its unique geographic location, harboring a high proportion of endemic and relict species, making it a vital component of the global ecosystem. However, economic development and land use have caused habitat loss and post significant threats to biodiversity. In response to growing environmental awareness, Taiwan has implemented strict conservation policies, designating almost 20% of its land and marine territories as protected zones. Despite these efforts, approximately 60% of conservation species inhabit regions overlap with areas of human activity. Over the past 20 years, the Taiwan Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (FANCA) has embraced towards a community-based conservation model, fostering harmony between people and nature. This trend aligns with the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which emphasizes the establishment of "Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures" (OECM).

Keywords: biodiversity conservation, community-based conservation, OECM

INTRODUCTION

Taiwan, located at the intersection of the Eurasian continent and the Pacific tectonic plate, is a long, narrow island formed by tectonic pressures. The island of Taiwan, along with the surrounding islands like Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, Lanyu, and Green Island, covers a total area of about 36,000 square kilometers.

Taiwan's central region is dominated by towering mountains, with Yushan being the highest peak at 3,952 meters. The terrain drops sharply to sea level within less than 100 kilometers in width, creating a diverse topography that includes mountains, hills, valleys, volcanoes, basins, terraces, and coasts.

In terms of climate, Taiwan's surrounding seas merge warm and cold currents, and it sits at the junction of tropical and subtropical climates, characterized by high annual temperatures and abundant rainfall. This interaction of terrain and climate creates a wide variety of ecosystems on this relatively small island. Taiwan's terrestrial ecosystems range from alpine tundra, grasslands, coniferous and broadleaf forests to tropical monsoon and coastal forests. Aquatic ecosystems include streams, lakes, and marshes, while coastal areas feature beaches, coral reefs, and mangroves. The ocean harbors deep-sea vents, seagrass beds, and coral reefs (Li et al, 2021).

Archaeological evidence shows that humans have lived in Taiwan since the Paleolithic era. Over time, human activities evolved from gathering and hunting to farming, iron smelting, and trading, with settlements scattered across the island. Starting in the 16th century, Dutch settlers and Han Chinese began cultivating the western plains of Taiwan, gradually transforming the landscape into farmlands. By the late 19th century, when Taiwan was ceded to Japan, much of the western and northeastern plains, hills, and parts of the eastern valleys had been developed, laying the foundation for modern urban development (Liu, 2019).

Currently, Taiwan's population is around 23 million, concentrated mainly in the western plains in cities such as Taipei, New Taipei, Taoyuan, Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung. The population density is as high as 647 people per square kilometer, second only to Bangladesh among countries with populations over 10 million (Executive Yuan, 2024). Taiwan's economy is primarily driven by industry and commerce, creating significant demand for environmental resources, often leading to conflicts between human development and ecological conservation.

CURRENT STATUS OF TAIWAN’S BIODIVERSITY

Based on the statistic of TaiCOL until November, 2024, Taiwan is currently known to host over 64,000 native and exotic species. These diverse organisms encompass animals, plants, fungi, algae, bacteria and viruses, etc. Due to the geographic isolation caused by tectonic activity, Taiwan has a high percentage of endemic species, particularly insects, mammals, and reptiles, with endemic rates of 30.5%, 20.1%, and 17.3% respectively (Li, 2021). Some relict species, such as the Formosan salamander, cherry salmon, Taiwan cycad, and Taiwan beech, also exist.

Many species in Taiwan face serious threats due to development pressures, invasive species, and climate change. According to the 2016-2017 Red List published by Taiwan’s Biodiversity Research Institute, 105 wild animal species and 989 vascular plant species are classified as threatened. Amphibians are the most affected group, with 11 out of the 37 evaluated species (29.7%) listed as threatened. Freshwater fish follow, with 26.3% of 95 species facing threats. For mammals, 15% of the 80 evaluated species are threatened, and the Formosan clouded leopard is now considered extinct. Additionally, 22.3% of Taiwan’s 4,442 vascular plant species are listed as threatened, with 27 taxa already extinct (The Red List of Vascular Plants of Taiwan, 2017). The most well-known example is Rhododendron kanehirae (Wulai Azalea). Its original habitat was flooded due to the construction of the Feitsui Reservoir in 1984. Since then, it has been extinct in the wild but preserved in other suitable habitats (Taipei Feitsui Reservoir Administration, 2013).

Taiwan has also identified 230 invasive species, including 41 bird species, 10 reptile species, 5 amphibians, 27 fish species, and 55 plant species (Taiwan Invasive Species Database, 2024). Some of the most harmful invasive species, such as Mikania micrantha (mile-a-minute weed), golden apple snail, water hyacinth, and pinewood nematode, have severely impacted native ecosystems and industries. While efforts are being made to control these invasive species, results remain limited.

SHIFTING ENVIRONMENTAL PARADIGMS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF PROTECTED AREAS

Starting in the 1960s, Taiwan faced various environmental problems due to industrial development, including pollution from wastewater, wastes, and emissions, which also threatened human health. Natural disasters like floods and landslides from typhoons highlighted the environmental damage caused by excessive development. By the 1980s, the environmental movement in Taiwan was gaining momentum, with many non-governmental environmental groups being established. This shift in public consciousness moved away from the human-centered "anthropocentric" view, which prioritized development, towards a life-centered or "biocentric" view and even further to an "ecocentric" view that values the intrinsic worth of ecosystems (Zhang, 2007).

We also observe a shift in the governance tools used to address environmental issues. Taiwan's earliest conservation-related regulations date back to the 1930s with the Forestry Act, which initially focused on developing and utilizing forest resources. However, since 1985, the law’s objectives have shifted to conserving forest resources, emphasizing both their ecological and economic value. Similarly, the Act on Wildlife Conservation, first enacted in 1989, was amended in 1994 to include biodiversity conservation as part of its legislative goals.

In 1972, Taiwan enacted the National Park Law, setting standards for establishing and managing national parks. Since the first national park, Kenting National Park, was designated, Taiwan has established nine national parks. After the 2010 amendment, the law also allowed for the designation of smaller "National Nature Parks." In total, Taiwan has 98 terrestrial protected areas covering 694,000 hectares, accounting for about 19.18% of the land area. The marine protected area system includes seven categories across 70 locations, covering 540,000 hectares, or 8.38% of Taiwan’s waters. These protected areas provide various degrees of protection through different legal frameworks (see Table 1 and Table 2). Combined with nearly 60% of Taiwan’s public forest land territory, the Central Mountain Range conservation corridor provides significant protection for wildlife.

Table 1. Taiwan’s terrestrial protected area system

|

Category

|

Amount

|

Legal Basis

|

Control Measures

|

|

Nature Reserves

|

22

|

Cultural Heritage Preservation Act

|

Prohibits altering or damaging the original natural state.

|

|

Wildlife Refuges

|

21

|

Act on Wildlife Conservation

|

Prohibits harassment, abuse, hunting, or killing of wildlife, cutting plants, and polluting or destroying habitats.

|

|

Major Wildlife Habitats

|

39

|

Act on Wildlife Conservation

|

Construction or land use must minimize impact on wildlife habitats. Environmental Impact Assessments may be required.

|

|

National Parks

|

9

|

National Park Law

|

Prohibits burning vegetation, hunting, fishing, polluting water or air, picking flowers, and littering.

|

|

National Nature Parks

|

1

|

National Park Law

|

Same as national parks; activities must minimize impact on wildlife and require environmental impact assessments.

|

|

Forest Reserves

|

6

|

Forestry Act

|

Entry requires application and approval.

|

|

Total

|

98

|

|

|

Source: FANCA (2023), Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date).

Table 2. Taiwan’s marine protected area system

|

Category

|

Amount

|

Legal Basis

|

Control Measures

|

|

Aquatic Organisms Propagation and Conservation Zone

|

30

|

Fisheries Act

|

Local authorities establish management regulations.

|

|

Marine Ecological protection areas in National Parks

|

4

|

National Park Law

|

Prohibits human activities except for permitted ecological or scientific research.

|

|

Wildlife Refuges

|

5

|

Act on Wildlife Conservation

|

Prohibits harassment, abuse, hunting, or killing of wildlife, and pollution or destruction of the environment.

|

|

Natural Landscapes and Natural Monuments

|

6

|

Cultural Heritage Preservation Act

|

Nature reserves prohibit altering the natural state; natural monuments prohibit damage through picking, cutting, or excavation.

|

|

Marine Resource Conservation Zones

(Designated scenic spots)

|

2

|

Act for the Development of Tourism, Urban Planning Act

|

Any facility projects must gain approval from relevant authorities.

|

|

Wetlands of Importance

|

22

|

Wetland Conservation Act

|

Prohibits unauthorized water extraction, land alteration, pollution, hunting, and cutting or harvesting activities.

|

|

Major Wildlife Habitats

|

1

|

Act on Wildlife Conservation

|

Construction or land use must minimize impact on wildlife habitats. Environmental Impact Assessments may be required.

|

|

Total

|

70

|

|

|

Source: Ocean Affairs Council (no date), Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date).

MOVING TOWARDS PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN CONSERVATION POLICIES

Despite many protected areas, nearly 60% of Taiwan’s conservation species live in regions like foothills, streams, wetlands, and densely populated coastlines that face more significant development pressure. These areas, with fragmented habitats, require not only government protection through laws but also support from the public. Conservation in these regions must consider the livelihoods of residents. Since much of this land is privately owned, a community-based conservation model, rather than the Yellowstone model of strictly protected areas, is more appropriate (Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation, 2020).

Since 2002, Taiwan has promoted the Community Forestry Program, which shifted the relationship between local communities and the Forestry Bureau (now the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency, FANCA). In the past, there was tension between the Forestry Bureau, which managed forestry and conservation, and local communities (Chen, 2009). Through education and training, residents learned about forest management and conservation, becoming local partners who help with tasks like resource monitoring, ecosystem restoration, and removing invasive species. This collaboration has also spurred new industries such as ecotourism, environmental education, and eco-friendly agriculture (Tsai & Wu, 2024).

Following Japan's hosting of the 10th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010, the Satoyama Initiative was introduced. This initiative focuses on the conservation and sustainable use of "socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes" (SEPLs) to promote harmony between humans and nature, aligning with the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Taiwan adopted the Satoyama Initiative that same year, starting with the restoration of traditional rice terraces and forming the Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (TPSI). This network connects communities, scholars, and government bodies to explore local action plans. Until 2023, TPSI has gained up to 23 members nationwide (FANCA & Dong Hwa University, 2023).

Based on these experiences, in 2018, the FANCA launched the Taiwan Ecological Network (TEN) project. This integrated initiative focuses on lowland areas, rivers, wetlands, and coastlines to connect Taiwan’s green corridors and river systems. The goal is to create a biological safety corridor linking forests, rivers, villages, and seas, enhancing ecosystem functionality and biodiversity. This project also aligns with the Satoyama Initiative's principles of conserving and sustainably using SEPLs to strengthen community resilience.

The TEN projects began by identifying biodiversity hotspots and engaging experts to map 8 TEN Zones and 44 Priority Biodiversity Areas. Within these regions, 45 Conservation Corridors were established to connect critical habitats, ensuring ecosystem connectivity from mountains to the seas through green or blue corridors.

Table 3. Levels of the National Ecological Green Network

|

Level of Network

|

Amount

|

Region/Category

|

|

TEN Zones

|

8

|

North, Northwest, West, Southwest, South, East, Northeast

|

|

Priority Biodiversity Areas

|

44

|

Subdivided by each TEN Zones

|

|

Conservation Corridors

|

45

|

12 hill-type, 14 stream-type, 8 plain-type, 6 coast-type, 5 island-type

|

Source: FANCA (2020).

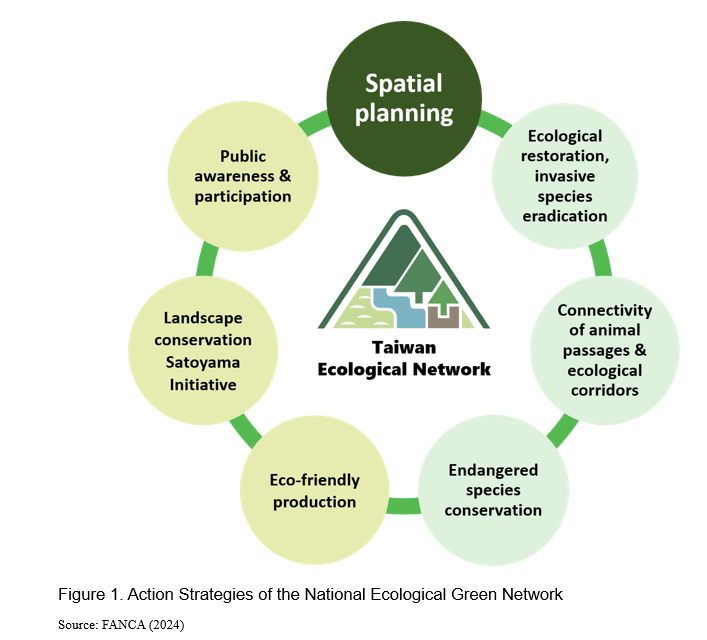

Seven key action strategies were used to promote conservation work. These strategies incorporated expert knowledge and technical support while involving local communities in eco-friendly agriculture, the Satoyama Initiative, and integrating conservation into daily life.

- Spatial planning:

After identifying focus species and habitats, the project gathered and visualized data through GIS systems, enabling collaboration across government departments and private sectors.

- Ecological restoration, invasive species eradication

This involves planting native trees along riverbanks and agricultural areas, restoring rare plant species, and removing invasive species in priority areas.

- Connectivity of animal passages & ecological corridors

In high-risk and low-resilience areas, strategies focused on constructing animal corridors and applying eco-friendly engineering solutions.

- Endangered species conservation

Conservation action plans for 22 endangered species were applied in high-risk regions, with efforts to restore population numbers and build wild animal rescue and plant rehabilitation sites.

- Eco-friendly production

The principle of conserving SEPLs was applied to promote eco-friendly farming and sustainable fisheries, reducing the impact of agriculture on ecosystems.

- Landscape conservation & Satoyama Initiative

This included initiatives to encourage local community and farmer involvement in species conservation, promoting local action plans.

- Public awareness & participation

Public-private collaboration in environmental building and developing education programs combined local cultural and ecological resources to support conservation.

Since the project requires both cross-sectoral and cross-level government involvement, platforms were created to facilitate collaboration. At the operational level, regional forest management offices take the lead in establishing regional inter-agency platforms to discuss conservation goals, strategies, tools, and partnerships. As to broader networking, the "Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative" (TPSI) functions to invite communities, tribes, NGOs, NPOs, and academic institutions to discuss key issues and create reciprocal bonds. For policy-related matters, the FANCA convenes relevant agencies to jointly discuss overall plans, assess resources, prioritize issues, and formulate implementation strategies (Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation, 2020).

CONCLUSION

The 2022 Convention on Biological Diversity held at the 15th Conference of the Parties introduced the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which replaces the Aichi Targets and established new biodiversity conservation goals for 2030. The framework aims to protect 30% of the world's land and marine areas by 2030. Notably, it expands beyond officially designated Protected Areas to include Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs), emphasizing the critical role of Indigenous peoples and local communities and the use of traditional knowledge in achieving these goals.

According to MacKinnon (no date), the definition of OECM is “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and, where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socioeconomic, and other locally relevant values”

Since the Community Forestry Program launch in 2002, the Satoyama Initiative in 2010, and the TEN project in 2018, Taiwan has accumulated positive outcomes in terms of conservation through numerous community and indigenous participation efforts. Platforms like TPSI and TEN have established mechanisms for cross-sector dialogue and cooperation, enhancing the continuous collaborations of local actors. These developments show that Taiwan's policy has a high potential to be aligned with international trends, and there is optimism for continued progress in biodiversity conservation. The growing emphasis on corporate social responsibility is expected to raise societal awareness of biodiversity conservation through various systems and communication methods and rally more public and private partners to participate in these initiatives.

REFERENCES

Biodiversity Research Institute, Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2016& 2017). The Red List. Retrieved from https://www.tbri.gov.tw/A6_2 (September 27, 2024).

Chen, Mei-Hui (2008). Implementation Results of the Community Forestry Program. Agriculture Policy & Review, 209. Retrieved from https://www.moa.gov.tw/ws.php?id=20484 (2024, September 27).

Executive Yuan (2024). Population. Retrieved from https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/99B2E89521FC31E1/835a4dc2-2c2d-4ee0-9a36-a0629a5de9f0 (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2023). Summary of Protected Areas. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/total (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2023). Taiwan Ecological Network. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/TEN (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (no date). Satoyama Initiative. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/0002040 (September 28, 2024).

Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date). Retrieved from https://lis.ly.gov.tw/lglawc/lglawkm (September 30, 2024).

Li, Lingling et al. (2021). 2020 National Biodiversity Report. Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency.

Liu, Cui-Rong (2019). Taiwan Environmental History (1st edition). NTU Press.

MacKinnon, K. (no date). Other Effective Area-based Conserv Measures (OECMs). Retrieved from https://www.cbd.int/protected/partnership/vilm/presentations/15_oecm_mackinnon.pdf (September 30, 2024).

Ocean Affairs Council (no date). Marine Protected Areas of Taiwan. Retrieved from https://mpa.oca.gov.tw/ (2024, September 26).

Taipei Feitsui Reservoir Administration (2013) The Restoration of the Wulai Azalea. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20131215060015/http://www.feitsui.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=117358&CtNode=31452&mp=122011 (November 19, 2024)

Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation (2020). Blueprint and Development Report for the Taiwan Ecological Network. Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency.

Tsai, Zi-Yi, Wu, Mei-Yi (2024). Practicing the Satoyama Initiative: Strengthening the Forest, River, Village, and Sea. Agriculture Policy & Review, 387.

Zhang, Zi-Chao (2007, December 1). An Era of Rapid Environmental Paradigm Shifts. Environmental Information Center. Retrieved from https://e-info.org.tw/node/212925 (2024, September 26).

Current Status and Trends in Taiwan's Biodiversity and Conservation Policies

ABSTRACT

Taiwan’s rich biodiversity stems from its unique geographic location, harboring a high proportion of endemic and relict species, making it a vital component of the global ecosystem. However, economic development and land use have caused habitat loss and post significant threats to biodiversity. In response to growing environmental awareness, Taiwan has implemented strict conservation policies, designating almost 20% of its land and marine territories as protected zones. Despite these efforts, approximately 60% of conservation species inhabit regions overlap with areas of human activity. Over the past 20 years, the Taiwan Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (FANCA) has embraced towards a community-based conservation model, fostering harmony between people and nature. This trend aligns with the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which emphasizes the establishment of "Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures" (OECM).

Keywords: biodiversity conservation, community-based conservation, OECM

INTRODUCTION

Taiwan, located at the intersection of the Eurasian continent and the Pacific tectonic plate, is a long, narrow island formed by tectonic pressures. The island of Taiwan, along with the surrounding islands like Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, Lanyu, and Green Island, covers a total area of about 36,000 square kilometers.

Taiwan's central region is dominated by towering mountains, with Yushan being the highest peak at 3,952 meters. The terrain drops sharply to sea level within less than 100 kilometers in width, creating a diverse topography that includes mountains, hills, valleys, volcanoes, basins, terraces, and coasts.

In terms of climate, Taiwan's surrounding seas merge warm and cold currents, and it sits at the junction of tropical and subtropical climates, characterized by high annual temperatures and abundant rainfall. This interaction of terrain and climate creates a wide variety of ecosystems on this relatively small island. Taiwan's terrestrial ecosystems range from alpine tundra, grasslands, coniferous and broadleaf forests to tropical monsoon and coastal forests. Aquatic ecosystems include streams, lakes, and marshes, while coastal areas feature beaches, coral reefs, and mangroves. The ocean harbors deep-sea vents, seagrass beds, and coral reefs (Li et al, 2021).

Archaeological evidence shows that humans have lived in Taiwan since the Paleolithic era. Over time, human activities evolved from gathering and hunting to farming, iron smelting, and trading, with settlements scattered across the island. Starting in the 16th century, Dutch settlers and Han Chinese began cultivating the western plains of Taiwan, gradually transforming the landscape into farmlands. By the late 19th century, when Taiwan was ceded to Japan, much of the western and northeastern plains, hills, and parts of the eastern valleys had been developed, laying the foundation for modern urban development (Liu, 2019).

Currently, Taiwan's population is around 23 million, concentrated mainly in the western plains in cities such as Taipei, New Taipei, Taoyuan, Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung. The population density is as high as 647 people per square kilometer, second only to Bangladesh among countries with populations over 10 million (Executive Yuan, 2024). Taiwan's economy is primarily driven by industry and commerce, creating significant demand for environmental resources, often leading to conflicts between human development and ecological conservation.

CURRENT STATUS OF TAIWAN’S BIODIVERSITY

Based on the statistic of TaiCOL until November, 2024, Taiwan is currently known to host over 64,000 native and exotic species. These diverse organisms encompass animals, plants, fungi, algae, bacteria and viruses, etc. Due to the geographic isolation caused by tectonic activity, Taiwan has a high percentage of endemic species, particularly insects, mammals, and reptiles, with endemic rates of 30.5%, 20.1%, and 17.3% respectively (Li, 2021). Some relict species, such as the Formosan salamander, cherry salmon, Taiwan cycad, and Taiwan beech, also exist.

Many species in Taiwan face serious threats due to development pressures, invasive species, and climate change. According to the 2016-2017 Red List published by Taiwan’s Biodiversity Research Institute, 105 wild animal species and 989 vascular plant species are classified as threatened. Amphibians are the most affected group, with 11 out of the 37 evaluated species (29.7%) listed as threatened. Freshwater fish follow, with 26.3% of 95 species facing threats. For mammals, 15% of the 80 evaluated species are threatened, and the Formosan clouded leopard is now considered extinct. Additionally, 22.3% of Taiwan’s 4,442 vascular plant species are listed as threatened, with 27 taxa already extinct (The Red List of Vascular Plants of Taiwan, 2017). The most well-known example is Rhododendron kanehirae (Wulai Azalea). Its original habitat was flooded due to the construction of the Feitsui Reservoir in 1984. Since then, it has been extinct in the wild but preserved in other suitable habitats (Taipei Feitsui Reservoir Administration, 2013).

Taiwan has also identified 230 invasive species, including 41 bird species, 10 reptile species, 5 amphibians, 27 fish species, and 55 plant species (Taiwan Invasive Species Database, 2024). Some of the most harmful invasive species, such as Mikania micrantha (mile-a-minute weed), golden apple snail, water hyacinth, and pinewood nematode, have severely impacted native ecosystems and industries. While efforts are being made to control these invasive species, results remain limited.

SHIFTING ENVIRONMENTAL PARADIGMS AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF PROTECTED AREAS

Starting in the 1960s, Taiwan faced various environmental problems due to industrial development, including pollution from wastewater, wastes, and emissions, which also threatened human health. Natural disasters like floods and landslides from typhoons highlighted the environmental damage caused by excessive development. By the 1980s, the environmental movement in Taiwan was gaining momentum, with many non-governmental environmental groups being established. This shift in public consciousness moved away from the human-centered "anthropocentric" view, which prioritized development, towards a life-centered or "biocentric" view and even further to an "ecocentric" view that values the intrinsic worth of ecosystems (Zhang, 2007).

We also observe a shift in the governance tools used to address environmental issues. Taiwan's earliest conservation-related regulations date back to the 1930s with the Forestry Act, which initially focused on developing and utilizing forest resources. However, since 1985, the law’s objectives have shifted to conserving forest resources, emphasizing both their ecological and economic value. Similarly, the Act on Wildlife Conservation, first enacted in 1989, was amended in 1994 to include biodiversity conservation as part of its legislative goals.

In 1972, Taiwan enacted the National Park Law, setting standards for establishing and managing national parks. Since the first national park, Kenting National Park, was designated, Taiwan has established nine national parks. After the 2010 amendment, the law also allowed for the designation of smaller "National Nature Parks." In total, Taiwan has 98 terrestrial protected areas covering 694,000 hectares, accounting for about 19.18% of the land area. The marine protected area system includes seven categories across 70 locations, covering 540,000 hectares, or 8.38% of Taiwan’s waters. These protected areas provide various degrees of protection through different legal frameworks (see Table 1 and Table 2). Combined with nearly 60% of Taiwan’s public forest land territory, the Central Mountain Range conservation corridor provides significant protection for wildlife.

Table 1. Taiwan’s terrestrial protected area system

Category

Amount

Legal Basis

Control Measures

Nature Reserves

22

Cultural Heritage Preservation Act

Prohibits altering or damaging the original natural state.

Wildlife Refuges

21

Act on Wildlife Conservation

Prohibits harassment, abuse, hunting, or killing of wildlife, cutting plants, and polluting or destroying habitats.

Major Wildlife Habitats

39

Act on Wildlife Conservation

Construction or land use must minimize impact on wildlife habitats. Environmental Impact Assessments may be required.

National Parks

9

National Park Law

Prohibits burning vegetation, hunting, fishing, polluting water or air, picking flowers, and littering.

National Nature Parks

1

National Park Law

Same as national parks; activities must minimize impact on wildlife and require environmental impact assessments.

Forest Reserves

6

Forestry Act

Entry requires application and approval.

Total

98

Source: FANCA (2023), Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date).

Table 2. Taiwan’s marine protected area system

Category

Amount

Legal Basis

Control Measures

Aquatic Organisms Propagation and Conservation Zone

30

Fisheries Act

Local authorities establish management regulations.

Marine Ecological protection areas in National Parks

4

National Park Law

Prohibits human activities except for permitted ecological or scientific research.

Wildlife Refuges

5

Act on Wildlife Conservation

Prohibits harassment, abuse, hunting, or killing of wildlife, and pollution or destruction of the environment.

Natural Landscapes and Natural Monuments

6

Cultural Heritage Preservation Act

Nature reserves prohibit altering the natural state; natural monuments prohibit damage through picking, cutting, or excavation.

Marine Resource Conservation Zones

(Designated scenic spots)

2

Act for the Development of Tourism, Urban Planning Act

Any facility projects must gain approval from relevant authorities.

Wetlands of Importance

22

Wetland Conservation Act

Prohibits unauthorized water extraction, land alteration, pollution, hunting, and cutting or harvesting activities.

Major Wildlife Habitats

1

Act on Wildlife Conservation

Construction or land use must minimize impact on wildlife habitats. Environmental Impact Assessments may be required.

Total

70

Source: Ocean Affairs Council (no date), Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date).

MOVING TOWARDS PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN CONSERVATION POLICIES

Despite many protected areas, nearly 60% of Taiwan’s conservation species live in regions like foothills, streams, wetlands, and densely populated coastlines that face more significant development pressure. These areas, with fragmented habitats, require not only government protection through laws but also support from the public. Conservation in these regions must consider the livelihoods of residents. Since much of this land is privately owned, a community-based conservation model, rather than the Yellowstone model of strictly protected areas, is more appropriate (Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation, 2020).

Since 2002, Taiwan has promoted the Community Forestry Program, which shifted the relationship between local communities and the Forestry Bureau (now the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency, FANCA). In the past, there was tension between the Forestry Bureau, which managed forestry and conservation, and local communities (Chen, 2009). Through education and training, residents learned about forest management and conservation, becoming local partners who help with tasks like resource monitoring, ecosystem restoration, and removing invasive species. This collaboration has also spurred new industries such as ecotourism, environmental education, and eco-friendly agriculture (Tsai & Wu, 2024).

Following Japan's hosting of the 10th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010, the Satoyama Initiative was introduced. This initiative focuses on the conservation and sustainable use of "socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes" (SEPLs) to promote harmony between humans and nature, aligning with the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Taiwan adopted the Satoyama Initiative that same year, starting with the restoration of traditional rice terraces and forming the Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (TPSI). This network connects communities, scholars, and government bodies to explore local action plans. Until 2023, TPSI has gained up to 23 members nationwide (FANCA & Dong Hwa University, 2023).

Based on these experiences, in 2018, the FANCA launched the Taiwan Ecological Network (TEN) project. This integrated initiative focuses on lowland areas, rivers, wetlands, and coastlines to connect Taiwan’s green corridors and river systems. The goal is to create a biological safety corridor linking forests, rivers, villages, and seas, enhancing ecosystem functionality and biodiversity. This project also aligns with the Satoyama Initiative's principles of conserving and sustainably using SEPLs to strengthen community resilience.

The TEN projects began by identifying biodiversity hotspots and engaging experts to map 8 TEN Zones and 44 Priority Biodiversity Areas. Within these regions, 45 Conservation Corridors were established to connect critical habitats, ensuring ecosystem connectivity from mountains to the seas through green or blue corridors.

Table 3. Levels of the National Ecological Green Network

Level of Network

Amount

Region/Category

TEN Zones

8

North, Northwest, West, Southwest, South, East, Northeast

Priority Biodiversity Areas

44

Subdivided by each TEN Zones

Conservation Corridors

45

12 hill-type, 14 stream-type, 8 plain-type, 6 coast-type, 5 island-type

Source: FANCA (2020).

Seven key action strategies were used to promote conservation work. These strategies incorporated expert knowledge and technical support while involving local communities in eco-friendly agriculture, the Satoyama Initiative, and integrating conservation into daily life.

After identifying focus species and habitats, the project gathered and visualized data through GIS systems, enabling collaboration across government departments and private sectors.

This involves planting native trees along riverbanks and agricultural areas, restoring rare plant species, and removing invasive species in priority areas.

In high-risk and low-resilience areas, strategies focused on constructing animal corridors and applying eco-friendly engineering solutions.

Conservation action plans for 22 endangered species were applied in high-risk regions, with efforts to restore population numbers and build wild animal rescue and plant rehabilitation sites.

The principle of conserving SEPLs was applied to promote eco-friendly farming and sustainable fisheries, reducing the impact of agriculture on ecosystems.

This included initiatives to encourage local community and farmer involvement in species conservation, promoting local action plans.

Public-private collaboration in environmental building and developing education programs combined local cultural and ecological resources to support conservation.

Since the project requires both cross-sectoral and cross-level government involvement, platforms were created to facilitate collaboration. At the operational level, regional forest management offices take the lead in establishing regional inter-agency platforms to discuss conservation goals, strategies, tools, and partnerships. As to broader networking, the "Taiwan Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative" (TPSI) functions to invite communities, tribes, NGOs, NPOs, and academic institutions to discuss key issues and create reciprocal bonds. For policy-related matters, the FANCA convenes relevant agencies to jointly discuss overall plans, assess resources, prioritize issues, and formulate implementation strategies (Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation, 2020).

CONCLUSION

The 2022 Convention on Biological Diversity held at the 15th Conference of the Parties introduced the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which replaces the Aichi Targets and established new biodiversity conservation goals for 2030. The framework aims to protect 30% of the world's land and marine areas by 2030. Notably, it expands beyond officially designated Protected Areas to include Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs), emphasizing the critical role of Indigenous peoples and local communities and the use of traditional knowledge in achieving these goals.

According to MacKinnon (no date), the definition of OECM is “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and, where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socioeconomic, and other locally relevant values”

Since the Community Forestry Program launch in 2002, the Satoyama Initiative in 2010, and the TEN project in 2018, Taiwan has accumulated positive outcomes in terms of conservation through numerous community and indigenous participation efforts. Platforms like TPSI and TEN have established mechanisms for cross-sector dialogue and cooperation, enhancing the continuous collaborations of local actors. These developments show that Taiwan's policy has a high potential to be aligned with international trends, and there is optimism for continued progress in biodiversity conservation. The growing emphasis on corporate social responsibility is expected to raise societal awareness of biodiversity conservation through various systems and communication methods and rally more public and private partners to participate in these initiatives.

REFERENCES

Biodiversity Research Institute, Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2016& 2017). The Red List. Retrieved from https://www.tbri.gov.tw/A6_2 (September 27, 2024).

Chen, Mei-Hui (2008). Implementation Results of the Community Forestry Program. Agriculture Policy & Review, 209. Retrieved from https://www.moa.gov.tw/ws.php?id=20484 (2024, September 27).

Executive Yuan (2024). Population. Retrieved from https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/99B2E89521FC31E1/835a4dc2-2c2d-4ee0-9a36-a0629a5de9f0 (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2023). Summary of Protected Areas. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/total (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (2023). Taiwan Ecological Network. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/TEN (2024, September 27).

Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency (no date). Satoyama Initiative. Nature Conservation. Retrieved from https://conservation.forest.gov.tw/0002040 (September 28, 2024).

Legislative Yuan Legal System (no date). Retrieved from https://lis.ly.gov.tw/lglawc/lglawkm (September 30, 2024).

Li, Lingling et al. (2021). 2020 National Biodiversity Report. Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency.

Liu, Cui-Rong (2019). Taiwan Environmental History (1st edition). NTU Press.

MacKinnon, K. (no date). Other Effective Area-based Conserv Measures (OECMs). Retrieved from https://www.cbd.int/protected/partnership/vilm/presentations/15_oecm_mackinnon.pdf (September 30, 2024).

Ocean Affairs Council (no date). Marine Protected Areas of Taiwan. Retrieved from https://mpa.oca.gov.tw/ (2024, September 26).

Taipei Feitsui Reservoir Administration (2013) The Restoration of the Wulai Azalea. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20131215060015/http://www.feitsui.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=117358&CtNode=31452&mp=122011 (November 19, 2024)

Taiwan Ecological Engineering Development Foundation (2020). Blueprint and Development Report for the Taiwan Ecological Network. Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency.

Tsai, Zi-Yi, Wu, Mei-Yi (2024). Practicing the Satoyama Initiative: Strengthening the Forest, River, Village, and Sea. Agriculture Policy & Review, 387.

Zhang, Zi-Chao (2007, December 1). An Era of Rapid Environmental Paradigm Shifts. Environmental Information Center. Retrieved from https://e-info.org.tw/node/212925 (2024, September 26).