ABSTRACT

In Nagaland, located within the Indo-Burma and Himalaya biodiversity hotspots in India, customary rights are protected by the Indian Constitution, and the majority of natural habitats (88.3%) are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village councils, district councils and other traditional institutions. These natural habitats or socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs) also termed as Satoyama landscapes, comprise of a mosaic of different vegetation types and can be broadly categorized as primary forests, secondary forests, agricultural land (comprising mostly of shifting cultivation and to a small extent of terrace cultivation) and plantations. However, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activities in the villages are based upon utilization of natural resources. This has led to deforestation, degradation of forest resources, change in land-use patterns, hunting and an illegal trade of wild flora and fauna that pose as major challenges for the local fragile ecosystems. In response to this, a Satoyama Initiative was implemented on a pilot scale in three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland by rejuvenating traditional conservation practices in form of Community Conservation Areas (CCAs). The project focused on creating and linking CCAs across the pilot landscape, sensitizing communities and garnering their support for conservation through livelihood creation. As a result of the Satoyama Initiative, the three pilot villages are now protecting their landscapes jointly by declaring 939 hectares as CCA and banning hunting and destructive fishing across the remaining landscape of forests and rivers (total area being 3751 hectares). It has helped the communities in strengthening the age-old practice of conserving community forests through mobilization and building synergies. The project also responded to the critical needs of the pilot area by documenting the traditional knowledge and raising awareness of impacts of anthropogenic activities on the biodiversity and ecosystem services, and its ripple effect on the socio-economic and cultural lifestyle of the communities. Again, the project, through its effort to generate alternative livelihoods, has built the capacity of communities on ecotourism and is contributing to biodiversity conservation. This model of sustainable use of biological resources by adopting long-term sustainability and enhanced governance by the communities is being mainstreamed within the existing law framework and governance mechanism and upscaled through a multi-pronged approach including financial support, legal recognition and long-term monitoring.

Keywords: Community Conservation Areas (CCAs), Zunheboto, Nagaland

INTRODUCTION

The State of Nagaland in India harbors a forest cover of 12868 km² that accounts for 77.62% of the state’s total geographical area (FSI 2017). Falling in the Indo-Malayan region, it is located in one of the 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world. It also supports remarkable floral and faunal diversity with high levels of endemism. In Nagaland, community ownership and management of land is the norm amongst most tribes and forest lands are communally owned. Of the recorded forest areas as much as 7,621 sq. km falls under ‘Unclassed Forests’ or 88.3% of the recorded area (FSI, 2017) which are owned and managed by communities and community institutions. Thus the customary rights are protected under Article 371 A of the Constitution of India and the majority of natural habitats are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village and district councils and other traditional institutions. Hence customary land ownership and management practices characterize forest management in the North-East including Nagaland. However, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activity in the villages is largely agriculture and forest-centered leading to over-exploitation of natural resources.

In Nagaland, traditional conservation practices have helped protect biodiversity, and there are records of Community Conservation Areas (CCAs) being declared in the early 1800s especially in response to forest degradation and loss of wildlife (Pathak, 2009). In 1842, the tropical evergreen forests of Yingnyu shang were declared a Community Conservation Area by the Yongphang village in Longleng district. In 1983 in a Chakhasang tribal settlement called Luzophuhu, the local student’s union (LSU), resolved to conserve a 500 ha (5 sq. km) patch of forest land above the village. The motivation was to protect key sources of water. In 1990, the LSU declared another patch of forest below the main village, between the settlement and paddy fields, as a wildlife reserve with a total ban on hunting and other resource use. In 1998, the Khonoma village council declared its intention to protect about 2,000 ha (20 sq. km) of forest as the Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary (KNCTS). Khonoma in the 1900s was probably the only known example in Nagaland where hunting was banned in the entire village through the year (Kalpavriksh, 2006).

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) are defined as, ‘natural and/or modified ecosystems containing significant biodiversity values, ecological services and cultural values, voluntarily conserved by indigenous, mobile and local communities through customary laws and other effective means’ (IUCN 2009). A state-wide documentation in Nagaland revealed that one-third of Nagaland’s villages (407 villages out of 1428 in 11 districts) have constituted CCAs (TERI, 2015) and as many as 82% of these 407 CCAs have completely or partially banned tree felling and/or hunting within the CCAs, and enforce various regulations for conservation. These CCAs comprise of forests, freshwater resources, grasslands as well as agricultural-forest complexes and seek to address threats to natural ecosystems and cultural values from changing socio-cultural, economic and developmental imperatives, as well as unsustainable resource extraction practices-e.g. hunting and poaching or shifting cultivation practices on a reduced fallow cycle. In Nagaland, these CCAs which cover more than 1700 sq. km, by setting aside forests for conservation account to 18.5% of the total recorded forest area and contribute to carbon storage (an estimated 120.77 tons per ha). One of the major characteristic of the CCAs in Nagaland is that the communities are the decision makers, and have the capability to enforce regulations. The motivations for declaring the CCA appear to be multiple; foremost being the concern of forest degradation followed by declining numbers of key wildlife species due to hunting and water scarcity (TERI 2015).

However, the CCAs face numerous challenges- in their creation, effectiveness and sustainability and require sustained efforts for their conservation. Though most of the villages in Nagaland have some arrangement either to conserve a patch of forest or to protect a particular wild animal or plant traditionally, this type of conservation adopted by the village is based on an informal understanding and the villagers may or may not comply with it. On the contrary, villages who want to manage their CCAs well have been observed to pass resolution with well-laid rules and set goals issued by the village councils, tribal hohos[1] or Gaon burrahs[2] of respective CCAs. Out of the 407 documented CCAs, a total of 311 CCAs (77%) were declared by resolutions passed in the village councils and tribal hohos while 91 CCAs (22%) had an informal understanding (TERI 2015). Moreover, these CCAs comprise of isolated forest fragments (average size is 500 ha) and only a handful form part of a larger network of community forests. Through this paper, we would like to highlight the success story of implementing Satoyama Initiative by mainstreaming Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) for conservation, enhanced productivity through ecosystem services and livelihood generation in the State of Nagaland in India.

METHODOLOGY

Study site

Three villages- Sukhai, Ghukhuyi and Kivikhu lying in the southern region of Satakha block of the Zunheboto district in the state of Nagaland were selected as a pilot site under the work initiated by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) with support from Conservation International (CI) Japan via a Global Environment Facility (GEF)-Satoyama grant. The pilot site lies in the heart of Nagaland at an altitude of 1900 m and has sub-tropical wet hill forest primarily overlapping with the sub-tropical pine forest. The flora consists of large trees including Gmelina arborea, Melia composite, Terminalia myriocarpa, Artocarpus chaplasa, Chukrasia tabularis, Duabanga sonneratoides, Anthocephalus cadamba, Michelia champaca, Pinus petula, Pinus kesiya and Albizia procera while the dominant orchid species are Dendrobium, Bulbophyllum, Calanthe, Coelegyne, Liparis, Eria, Cymbidium, Oberonia, Pholidota, Goodyera, Habenaria and Peristylus. The pilot site acts as an important green corridor between the biodiversity-rich forests of Satoi range and Ghosu bird sanctuary and harbours endangered and threatened species like the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) and Chinese Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla). The river Tizu which flows through to these villages harbors a number of IUCN Red List fish species.

The pilot villages are dominated by the Sema tribe and the economy is largely agriculture and forest-centered. Though farming is mainly for subsistence, high dependence prevails on the other abundant resources of jhum (shifting cultivation) lands which include timber, medicinal plants and non-timber forests products. Wildlife is an important resource for the communities and is exploited for various reasons, including food, additional income, and cultural practices and as a sport. The overall Satoyama landscape comprises of a mosaic of different vegetation types and can be broadly categorized as primary forests, secondary forests, jhum land, terrace fields and plantations.

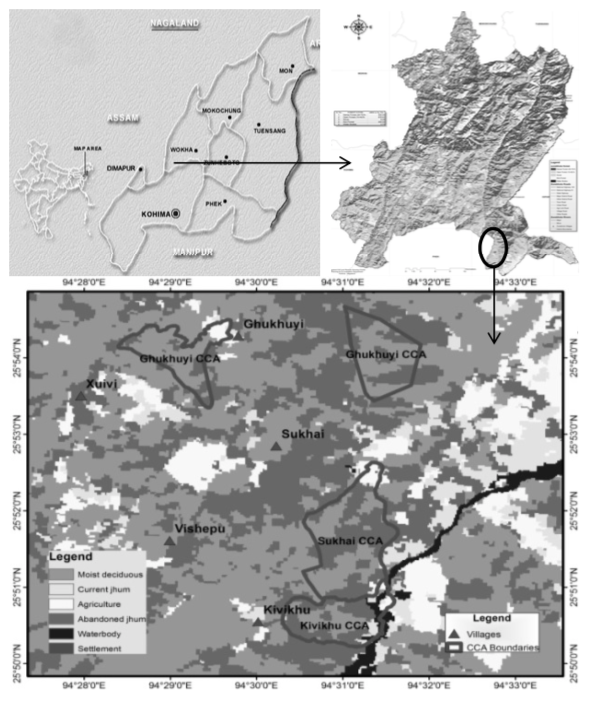

Figure 1. Project landscape and habitat features including forests, jhum fields and rice terraces

Figure 2. Map of the indicating location reference of the pilot site

Importance of Satoyama landscape and associated challenges

The Satoyama landscape of Zunheboto provides the local people with almost all of their daily subsistence and survival needs, apart from contributing to their rich cultural heritage, folklore and traditions. The landscapes of this area consist of diverse elements- Subtropical forests interspersed with jhum (shifting cultivation) fields and differentially aged, regenerating jhum fallows. Consequently, the people farm in the forest and the two are perceived to be inextricably linked by the local communities. The forests provide enormous provisioning benefits to the local communities in terms of ecosystem services such as timber, fuelwood and forest products. Food production through provisional ecosystem services is enhanced owing to their location with the forests (for example through enhanced pollination, water flows, nutrient enrichment, natural fertilizers). The jhum fields sustain a diversity of local varieties of crops including Maize, millets and Job’s tears (Coix spp.) that feed the people and their livestock. The forests also provide shade and moisture to horticultural crops like cardamom that are gaining popularity owing to their quick and sure returns. Several trees are planted on the private land adjacent to the forests that are economically important to the communities and are sold for timber or fuelwood. The Tizu River flowing through their lands irrigates their fields and forests and provides them with fish. The silt it brings assists in enhancing nutrients of the agricultural lands. In the valley areas adjoining the rivers, people also grow paddy in a pani-kheti system (terrace farming). Local land races are preferred and grown including Miyeghu which is a local paddy variety, Naga Mircha (Capsicum chinense) and the Nagaland Tree Tomato or Tamarillo (Cyphomandra betacca) that have recently acquired the Geographical Indication (GI) tag as directed by the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. The communities also maintain home gardens which comprises of vegetable and fruit plants and trees. These home gardens are not only a source of important food groups in the diet of the local people, but also help in carbon sequestration.

Traditionally, the Naga tribes had an intimate relationship with nature based on a foundation of the interconnectedness of God, people and nature. This is reflected in their rich folklore on the plants and animals of their forests. Some of these stories underline the ecological role that animals play in the ecosystem and their contribution to ‘ecosystem services’ for human beings. For example, the role of the earthworm in enhancing soil fertility is transmitted through a folktale (TERI, 2017). The value of their SEPLs was culturally realized and codified through wise use-for example the killing of pregnant animals and birds was a taboo that would bring misfortune to the hunter and his family. Fishing and the use of certain poisonous roots and leaves that kill fishes in the rivers or springs during the spawning season were also restricted (Lkr & Martemjen, 2014). The Naga people in general consider all land to be sacred. Jhuming or shifting cultivation involves clearing the land and burning the jungle, so people propitiate the spirit with rice, crabs and rice beer to beg for forgiveness for the many animals, plants, birds and reptiles that might be inadvertently harmed. The entire lives of the Sema people revolve around their forest-farm landscape. All the cultural festivals of the local people are linked to their agricultural calendar and the Sema people’s agricultural calendar in turn is attuned to nature, guided by the movement of the stars or of birds-their migration patterns, breeding seasons and songs. For example, the sowing of paddy is initiated only when the constellation of Orion (Phogwosiilesipfemi) is at its zenith or after the Kashopapu, a species of cuckoo is heard calling (Hutton 1921a). The two main festivals of the Sema tribe are Tuluni and Ahuna. Tuluni held on July 8 each year is marked with feasts as the occasion occurs in the bountiful season of the year while Ahuna held on November 14, is a traditional post-harvest festival signifying completion of successful agricultural work and sowing of next crop.

For the local Sema communities, a vibrant well-functioning Satoyama landscape implies that abundant wild fauna is present in their forests, and easily sighted for bushmeat when they jhum their fields, and that fish catches are abundant, large-sized and diverse (consisting of many species). Forests are protected at the top of hills so that their watershed services are enhanced. Traditionally, lengthening of the jhum cycle provides improved scope for natural biodiversity to regenerate. This is an extremely positive sign as jhuming is an excellent way to protect forests and associated biodiversity and yet produce crops, provided that long fallow periods allow for the forest to regrow. Amongst Sema tribals, fifteen to twenty years of jhum cycle was considered to be ideal, though seven to nine years is considered to be the shortest time in which the land is fit for cultivation. In particular land near the village tends to be left for the shortest time, since it is the easiest to cultivate (Hutton 1921a).

Figure 3. Forests, Tizu river, Terrace farming & Jhum cultivation representing Satoyama landscape

The current issues and challenges for the communities in managing the landscape mainly comprise of decreasing jhum cycles. Earlier when a forest patch was cleared, each patch was cultivated for only one to two years and then left to regenerate for upwards of 15 years. However the decreasing jhum cycles at present (less than seven years and often only for three to five years) prevent effective regeneration and leads to much soil erosion. In the State of Nagaland, out of total geographical area of 16,579 sq. km, approximately 937 sq. km is cleared annually for jhum cultivation in the state. Normally, the land is cropped for two years and thereafter allowed to lapse back into fallow. Paddy (rice) is the main crop in shifting cultivation. Shifting cultivation being carried out in approx. 5,229 ha (i.e. 31.5% of total wasteland) leads to burning of vegetation, soil erosion, wetland siltation, and clearing of natural vegetation (Nagaland SAPCC, 2012). However, with the increasing trend of urban migration, increasing education levels, and availability of alternative livelihoods, anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of farmers involved in Jhum have been decreasing during the past decade. An internal study carried out by NEPED in 2011 indicates that jhum cultivation area has decreased from 1.87 million ha in 2003 to 1.2 million hectares in 2005–06. If this trend continues, shifting cultivation may become viable but the practice itself may face extinction, which may not be a desirable outcome.

The local communities are dependent on forests for food, shelter, water, fuel, fodder, and medicines. Forests are abundant and provide for timber and fuel wood for the villagers. They also collect varieties of non-timber forest produce (NTFP) from forests that are available almost all round the year and meet a major part of a villager’s food. It is also a source of cash for the rural households (Nagaland SAPCC, 2012). Given the dependence of the local community on forest cover for a variety of provisioning and regulating ecosystem services, loss of forest cover has affected agriculture and the availability of water for domestic and agricultural use. The current firewood consumption in Nagaland is about 8.7 million cubic meters assuring the tree stand volume to approximately equivalent to that of jhum which is 188m³ trees from 46090 ha of wood. The demand of fire wood for fuel has increased three fold as compared to the early 1970’s in Nagaland. As per the latest report, the state has shown a decreasing trend accounting to a total loss of forest cover of 450 sq km (ISFR 2017). . Inspite of heavy pressures, the forest cover of Nagaland is 77.62% which is much higher than the minimum of 66% as envisaged in national forest policy of 1988.

With growing human population, increased accessibility to remote forests and adoption of modern traps and guns, hunting has become a severe global problem, particularly in Nagaland. While Indian wildlife laws prohibit hunting of virtually all large wild animals, in several parts of North-Eastern parts of India including Nagaland that are dominated by indigenous tribal communities, these laws have largely been ineffective due to cultural traditions of hunting for meat, perceived medicinal and ritual value, and the community ownership of the forests. Since most of the animals are considered edible, hunting and poaching for meat is a serious threat to the survival of wildlife especially the endangered ones. Decrease of habitat and improvement of fire-arms have worsened the situation. Local communities living in the vicinity of forests depend on wildlife for livelihood and income generation. Aggressive fishing using poisons (such as bleach and lime powder), dynamite and electrocution using battery packs has also led to reduction in fish populations of the Tizu River flowing adjacent to the pilot villages. The fear of losing all the fish and the natural ecosystem is one of the reasons that led to local communities declaring a reserve in their landscape. As a wise-use practice, they believe that fish and other animal species breed in the reserved areas and their populations are revitalized and replenished over time.

Figure 4. Jhum cultivation, excessive logging in forests and skulls of hunted wild animals on display

Genesis of developing Joint Community Conserved Area in Zunheboto district, Nagaland

In 2002, the village of Sukhai in Zunheboto district, realizing that it had undergone considerable transformation in the landscape, in its land use and cropping patterns, its use of fishing methods and in its approach to conservation, passed a notification that puts a complete ban on hunting and fishing, felling of trees and protects the area’s biodiversity. “Azhoqha and Yayi” area (located in the far south of the village) earlier covered under jhum cultivation, were protected so as to safeguard the natural resources including living and non-living resources and maintain it for present and future generations. However, due to an informal understanding and absence of a well-delineated program to safeguard ecosystems and conserve biodiversity led to an unsuccessful attempt to execute the ban. This movement was once again revived in 2015 when our organization-TERI was conducting a study document the CCAs in Nagaland and was approached by the Sukhai village council to assist them in conserving their landscape. Since Sukhai village is the parent village of other villages including Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi that migrated away from it in the past and settled on the sides it was imperative to garner their support as the natural resources like forests, rivers and biodiversity is shared beyond village boundaries. Hence, to ensure conservation of large contiguous forest areas, it was decided to mobilise support to link the community conservation areas, revive traditional conservation practices, carry out ecological assessments of these CCAs, develop community-based ecotourism initiatives and formalise and mainstream a network of CCAs along with the Nagaland Government and the State Forest Department.

DESCRIPTION OF ACTIVITIES

Formation & formalization of joint Community Conservation Areas & joint CCA management committee

The three pilot villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi had kept aside parcels of land as reserve forests since time immemorial; however this type of conservation adopted by the village was based on an informal understanding and the communities were passively hunting and fishing in the reserve due to lack of compliance and effective implementation. Hence several deliberations were held with the communities of the three pilot villages in order to increase awareness of threats and integrated approaches at the community and stakeholder level. This was achieved through participatory planning, knowledge sharing, and capacity building. The communities through engagement were convinced that there was a strong need to manage the resources collectively and efficiently. Later, each of the individual three CCAs were delineated and mapped and the boundaries were well-defined through demarcation, digitization and participatory mapping. This resulted in larger contiguous patches of forests areas along with the unique endemic biodiversity they support to be managed through formation of a ‘Joint CCA Management Committee’. The communities were quick to form Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network (TVBCLN) – a formal local CCA Management Committee that declared and enforced a blanket ban on hunting wild animals and birds, ban on fishing by use of explosives, chemicals and generators, strict prohibition of cutting of fire-wood/ felling of trees as well as collection of canes and other non-timber forest products for domestic and/ or commercial purposes in the CCAs.

Role of Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network (TVBCLN) in conservation education and sensitization

Around 35 sensitization campaigns were organized within the three pilot villages, with the neighboring villages and on other community platforms like the local festivals thus reaching out to a total of around 1500 individuals directly along with a positive impact on more than 15000 individuals indirectly living in the vicinity of the project site. The various forms of conservation education and sensitization programs included setting up informative stalls at local Ahuna festival, organizing awareness programs with key stakeholders like church groups, schools & education centres, carrying out plantations of local varieties, celebrating key day’s like the World Biodiversity day, World Environment Day etc. and organizing dedicated conservation themed events like the ‘Chengu[3] festival’. Also scientific publications, popular articles as well as websites (http://nagalandcca.org/ and http://gef-satoyama.net/) have helped to gain the attention of various stakeholders and boosted the engagement. In addition, exposure visits were undertaken for the community members to the neighboring states to showcase similar case studies, success stories and best practices with respect to community conservation.

Training of youth in biodiversity assessments & documentation of indigenous traditional knowledge

Biodiversity surveys by local communities have strengthened interest in conservation. The youth have been trained in documentation of flora and fauna by experts and currently they share pictures of wildlife taken by them on a “what’s app group.” Sightings are recorded in field registers and this has created a community of conservationists amongst the youth. These sightings are also important for research and are uploaded on websites such as birds and butterflies of India. Regular assessments can provide information on seasonal variations, range extensions and changes in population abundance. The local people can use this knowledge to develop their own resource monitoring methods. Moreover, camera traps can indicate whether RET (rare, endangered & threatened) species such as the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), are still sighted in the area. These surveys, by documenting unique, rare or special fauna have also acted as a catalyst to attract more outsiders to the area as ecotourists.

In Nagaland due to socio-political changes and development, traditional ecological knowledge is getting rapidly lost. Hence, it was imperative to document and preserve this rich ecological knowledge which can contribute to sustainable natural resource management in Nagaland. Keeping this in mind, efforts were made to document its people’s cultural connections with biodiversity in form of a People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR) for the three pilot villages. These registers, ‘contain comprehensive information on availability and knowledge of local biological resources, their medicinal or other use, or any other traditional knowledge associated with them’(Gadgil et al., 2005). Thus the PBRs prepared for the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi document the folklore, traditional knowledge, ecology, biodiversity and cultural practices of the local communities and help codify the oral knowledge of the local communities.

Alternative livelihood opportunities

The youth of the three pilot villages along with the hunters from each village dependent on hunting for subsistence were targeted and trained as nature guides with other trainings in association with Air BnB and Titli Trust on hygiene & environment care in homestays, safety and security, housekeeping service and food and beverage service, maximizing sales and managing money, and low cost marketing. Two biodiversity meets have been organized in the landscape since the formation of Joint CCA and it has resulted in enhanced livelihood opportunities with the steady flow of tourists.

Figure 5. Training of communities on use of GPS to demarcate CCA boundaries & Preparation of village resource maps

Figure 6. Stalls setup during local festivals for awareness generation & public meetings conducted

Figure 7. Training of youth on biodiversity assessments, Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii) & documentation of traditional biodiversity & associated knowledge

RESULTS

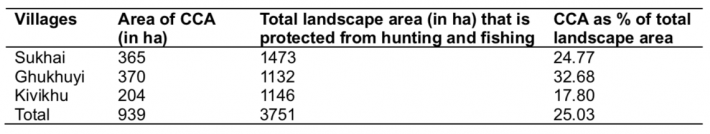

Over a short span of three years, the communities of the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland have formally declared around 939 hectares of biodiversity rich forest as community conservation area which is now being jointly managed by them (Table 1). However, apart from these CCAs, they have also banned hunting and destructive fishing across the entire landscape of their villages covering 3751 ha of forests and rivers. In general, each CCA on average is about 25% of the total landscape area owned by the village, which is quite large and has helped in acting as green corridors and safe haven for wildlife.

Table 1. Area of CCA and associated landscape

The blanket ban on hunting and destructive fishing has also resulted in conserving wildlife and revival of wild populations. Regular biodiversity surveys in the designated CCAs found an increase in the diversity of birds, reptiles, butterflies and moths with the current checklist listing 222 species of birds, 31 reptiles, 11 amphibians, 200 species of butterflies and more than 200 species of moths. This diversity is very high in comparison to the nearby patches of forest that do not receive protection. This rich biodiversity along with the associated traditional knowledge has been documented in form of People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs). It highlights the history of the Sema Nagas, the tribe inhabiting pilot villages, and their association with nature. The PBR also captures the links of the culture and the economy of the Sema people with their local biodiversity. By doing so, local communities’ knowledge about their biological heritage is now registered and a commitment among them to conserve their rich traditions has been fostered.

The awareness programs and sensitization conducted by TVBLCN has led to many more villages urging a replication of these methods to manage their Satoyama landscapes, the latest being Chipoketa village, adjoining Kivikhu village, which is dominated by the Chakesang community. Taking cognizance of the efforts made by TVBLCN, the state government, local agencies and various village councils are now inviting the community members of the three pilot villages as resource persons in order to motivate, guide and lead the way for others. TVBLCN with help from TERI and Titli Trust has also managed to put up signboards and create informative material with a focus on local biodiversity.

With a focus on alternative livelihood options and enhancing income of the hunters & forest dependent families, two biodiversity meets have been organized to learn about and document the biodiversity of Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network comprising the villages of Sukhai, Ghukhuyi and Kivikhu in Zunheboto District, Nagaland and to initiate butterfly and bird tourism in these pilot villages. The visitors participated in the biodiversity surveys, stayed in local homestays, tasted sumptuous local cuisine, watched the traditional Sema dances and engaged with the local community to understand their activities to conserve their natural resources. Not only the presence of the visitors has boosted nature-based ecotourism, but the biodiversity assessments have also further added to the knowledge of the biodiversity of Nagaland.

Figure 8. Distinct CCA on right side of Tizu river and Jhum cultivation on left

Figure 9. (Left to Right) Eco-tourists in CCA, GIS map of CCAs & PBR of village Sukhai

CONCLUSION

The dominant paradigm of wildlife conservation, both globally, and in India is the creation of protected areas, where access to forest resources is restricted or highly regulated and local communities have little say in their management or in decision making. Such approaches, while helping to prevent conversion of land to alternative land uses, frequently conflicts with the livelihood concerns of local communities and puts their needs in direct competition with the conservation needs of wildlife. Hence these communities have no incentive to invest in conservation and conflict situations arise particularly where people not only are unable to realize their subsistence needs but additionally are subject to the depredations of wildlife. This situation has eroded support for the exclusionary or ‘fortress’ approach to conservation and buttressed support for more people-friendly and inclusive regimes for conservation including community conservation. The status and sustainability of CCAs is critically dependent on the ability of local communities to make decisions about land and resource uses, hold secure tenure and exclude outsiders from appropriating resources. Some of the most important factors contributing to the effectiveness of CCAs in the region today are the statutory mechanisms for a) collective and equitable decision-making and representation at the community level and b) communal ownership of land. While conservation policy and legislation is important, it is this overall local governance, the land tenure, and the institutional environment that is most critical to the success of CCAs (Blomley et.al. 2007).

Nagaland (along with other states of the North-East of India) has an advantage as constitutional provisions allow customary management of resources. Moreover, much of forest ownership lies in the hands of individuals, clans, councils and communities. The communities of Nagaland, therefore, have the flexibility of defining the boundaries, the interventions and the management patterns of these CCAs, thereby possessing all the necessary conditions for effective governance. While these CCAs offer much potential, the reality is that there are no panaceas for sustainable governance of natural resources a (e.g. Ostrom, 2007) and the issues and problems depend on the local attributes of resource systems, resources units, governance and actors (Ostrom, 2009). Nevertheless, this plurality of social-ecological systems in Nagaland is itself strength as communities can tailor their conservation practices to the availability of land (forests, agriculture), the needs of local populations, the state of wildlife populations and the resource base, and their own needs and traditions. Consequently, adaptability can be the hallmark of CCAs in Nagaland, as these areas are managed for a combination of cultural, utilitarian and aesthetic purposes.

One important lesson through this project is that if communities are well informed and empowered, they can take steps to protect their natural resources and use them judiciously. The project directly helped the communities in rejuvenating as well as strengthening the age-old practice of conserving community forests through mobilization and building synergies. The project also responded to the critical needs of the pilot area by documenting the traditional knowledge and raising awareness of impacts of anthropogenic activities on the biodiversity and ecosystem services of the community conserved areas, and its ripple effect on the socio-economic and cultural lifestyle of the Sema community. Again, the project through its effort to generate alternative livelihoods built the capacity of communities on ecotourism and is contributing to biodiversity conservation. The positive impacts of the project activities were evident at the end of the project where the communities reported increases in the protection of natural resources after the formation of a joint CCA and improvement in management of common resources. The elders were satisfied with the documentation of their traditional and cultural indigenous knowledge in the People's Biodiversity Registers (PBRs) while the youth, women groups and the marginalized members of the community reported increases in their household income due to ecotourism. The protection of a stretch of Tizu River passing along the boundary of CCA also resulted in increase of fish-catch downstream.

This project is just the start of what we hope will be a movement for conservation in the State of Nagaland. Long term sustainability, enhanced governance and effective conservation outcomes for wild fauna and flora, however, require sustained effort, motivation, awareness and capacity building. To ensure the future of Nagaland’s CCAs and thereby its biodiversity, a multi-pronged approach including financial support, legal recognition and long-term monitoring is required. Furthermore, local communities must be trained to monitor their resources, and to develop nature based tourism which will help generate support for conservation. The network of CCAs in Nagaland provides a wonderful example of a fledgling people’s movement for conservation that deserves to be strengthened and supported.

We are indebted to the local communities of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi who have shown the way for managing landscapes and ensuring sustainability of the initiatives post project period. The local communities now patrol their forests and prevent both outsiders and people from their own villages from hunting and fishing. They also share pictures of those disobeying their rules on a what’s app group for quick action, and educate and motivate the people of other villages to eschew hunting. The Tizu Valley Network further supports education and sensitization and livelihood activities. Moreover, the government has taken notice of this initiative and has come forward to support it by developing the area into a community reserve under the Indian (Wildlife) Protection Act, for which limited funding is available. This will help in upscaling of activities initiated by the communities by formalization and mainstreaming of a network of CCAs in the State which are at par with India’s Protected Area (PA) network in conjunction with the Nagaland Government and Forest Department.

REFERENCES

Blomley, R., Nelson, F., Martin, A. and Ngobo, M. 2007. Community Conserved Areas: A review of status and needs in selected countries of central and eastern Africa. Report for Cenesta and IUCN/TILCEPA.

Forest Survey of India (2017), State of Forest Report. Forest Survey of India, Dehradun.

Hutton, J.H. 1921. The Sumi Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Lkr, L.and Martemjen. 2014. Biodiversity conservation ethos in Naga folklore and folksongs. International Journal of Advanced Research 2: 1008-1013.

Nagaland State Acton Plan on Climate Change. 2012. Government of Nagaland and GIZ (Deutsche Gesellscha for Internatonale Zusarnmenarbeit GmbH - German Internatonal Cooperaton, India). pp: 187.

Ostrom, E. 2007. A Diagnostic Approach for Going Beyond Panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(39):15181–15187.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 325:419–422.

Pathak, N and N. Hazarika. 2012. India: Community conservation at a crossroads In: Dudley, N and S. Stolton (eds.); Protected Landscapes and Wild Biodiversity, Volume 3 in the Values of Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Series, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 104pp.

Pathak, N (ed.).2009. Community-Conserved Areas in India –A Directory, Kalpavriksh, Pune.

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) 2009, Indigenous and community conserved areas: a bold new frontier for conservation. IUCN, Geneva, Switzerland, viewed 15 February 2019, https://www.iucn.org/content/indigenous-and-community-conserved-areas-bold-new-frontier-conservation.

TERI. 2015. Documentation of community conserved areas of Nagaland, The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi.

TERI. 2017. A People’s Biodiversity Register of Kivikhu Village, Zunheboto, Nagaland. The Energy and Resources Institute, New Delhi.

|

Date submitted: September 17, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: October 7, 2019

|

[1] Tribal hohos = Tribal association at district level

[2] Gaon burrahs = Village elders

[3] Chengu = Great Barbet (Psilopogon virens)

Implementing Satoyama Initiative through Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) – A Success Story from Nagaland, India

ABSTRACT

In Nagaland, located within the Indo-Burma and Himalaya biodiversity hotspots in India, customary rights are protected by the Indian Constitution, and the majority of natural habitats (88.3%) are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village councils, district councils and other traditional institutions. These natural habitats or socio-ecological production landscapes (SEPLs) also termed as Satoyama landscapes, comprise of a mosaic of different vegetation types and can be broadly categorized as primary forests, secondary forests, agricultural land (comprising mostly of shifting cultivation and to a small extent of terrace cultivation) and plantations. However, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activities in the villages are based upon utilization of natural resources. This has led to deforestation, degradation of forest resources, change in land-use patterns, hunting and an illegal trade of wild flora and fauna that pose as major challenges for the local fragile ecosystems. In response to this, a Satoyama Initiative was implemented on a pilot scale in three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland by rejuvenating traditional conservation practices in form of Community Conservation Areas (CCAs). The project focused on creating and linking CCAs across the pilot landscape, sensitizing communities and garnering their support for conservation through livelihood creation. As a result of the Satoyama Initiative, the three pilot villages are now protecting their landscapes jointly by declaring 939 hectares as CCA and banning hunting and destructive fishing across the remaining landscape of forests and rivers (total area being 3751 hectares). It has helped the communities in strengthening the age-old practice of conserving community forests through mobilization and building synergies. The project also responded to the critical needs of the pilot area by documenting the traditional knowledge and raising awareness of impacts of anthropogenic activities on the biodiversity and ecosystem services, and its ripple effect on the socio-economic and cultural lifestyle of the communities. Again, the project, through its effort to generate alternative livelihoods, has built the capacity of communities on ecotourism and is contributing to biodiversity conservation. This model of sustainable use of biological resources by adopting long-term sustainability and enhanced governance by the communities is being mainstreamed within the existing law framework and governance mechanism and upscaled through a multi-pronged approach including financial support, legal recognition and long-term monitoring.

Keywords: Community Conservation Areas (CCAs), Zunheboto, Nagaland

INTRODUCTION

The State of Nagaland in India harbors a forest cover of 12868 km² that accounts for 77.62% of the state’s total geographical area (FSI 2017). Falling in the Indo-Malayan region, it is located in one of the 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world. It also supports remarkable floral and faunal diversity with high levels of endemism. In Nagaland, community ownership and management of land is the norm amongst most tribes and forest lands are communally owned. Of the recorded forest areas as much as 7,621 sq. km falls under ‘Unclassed Forests’ or 88.3% of the recorded area (FSI, 2017) which are owned and managed by communities and community institutions. Thus the customary rights are protected under Article 371 A of the Constitution of India and the majority of natural habitats are owned and managed by individuals and clans overseen by village and district councils and other traditional institutions. Hence customary land ownership and management practices characterize forest management in the North-East including Nagaland. However, in the absence of alternative livelihood options, most of the economic activity in the villages is largely agriculture and forest-centered leading to over-exploitation of natural resources.

In Nagaland, traditional conservation practices have helped protect biodiversity, and there are records of Community Conservation Areas (CCAs) being declared in the early 1800s especially in response to forest degradation and loss of wildlife (Pathak, 2009). In 1842, the tropical evergreen forests of Yingnyu shang were declared a Community Conservation Area by the Yongphang village in Longleng district. In 1983 in a Chakhasang tribal settlement called Luzophuhu, the local student’s union (LSU), resolved to conserve a 500 ha (5 sq. km) patch of forest land above the village. The motivation was to protect key sources of water. In 1990, the LSU declared another patch of forest below the main village, between the settlement and paddy fields, as a wildlife reserve with a total ban on hunting and other resource use. In 1998, the Khonoma village council declared its intention to protect about 2,000 ha (20 sq. km) of forest as the Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary (KNCTS). Khonoma in the 1900s was probably the only known example in Nagaland where hunting was banned in the entire village through the year (Kalpavriksh, 2006).

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) are defined as, ‘natural and/or modified ecosystems containing significant biodiversity values, ecological services and cultural values, voluntarily conserved by indigenous, mobile and local communities through customary laws and other effective means’ (IUCN 2009). A state-wide documentation in Nagaland revealed that one-third of Nagaland’s villages (407 villages out of 1428 in 11 districts) have constituted CCAs (TERI, 2015) and as many as 82% of these 407 CCAs have completely or partially banned tree felling and/or hunting within the CCAs, and enforce various regulations for conservation. These CCAs comprise of forests, freshwater resources, grasslands as well as agricultural-forest complexes and seek to address threats to natural ecosystems and cultural values from changing socio-cultural, economic and developmental imperatives, as well as unsustainable resource extraction practices-e.g. hunting and poaching or shifting cultivation practices on a reduced fallow cycle. In Nagaland, these CCAs which cover more than 1700 sq. km, by setting aside forests for conservation account to 18.5% of the total recorded forest area and contribute to carbon storage (an estimated 120.77 tons per ha). One of the major characteristic of the CCAs in Nagaland is that the communities are the decision makers, and have the capability to enforce regulations. The motivations for declaring the CCA appear to be multiple; foremost being the concern of forest degradation followed by declining numbers of key wildlife species due to hunting and water scarcity (TERI 2015).

However, the CCAs face numerous challenges- in their creation, effectiveness and sustainability and require sustained efforts for their conservation. Though most of the villages in Nagaland have some arrangement either to conserve a patch of forest or to protect a particular wild animal or plant traditionally, this type of conservation adopted by the village is based on an informal understanding and the villagers may or may not comply with it. On the contrary, villages who want to manage their CCAs well have been observed to pass resolution with well-laid rules and set goals issued by the village councils, tribal hohos[1] or Gaon burrahs[2] of respective CCAs. Out of the 407 documented CCAs, a total of 311 CCAs (77%) were declared by resolutions passed in the village councils and tribal hohos while 91 CCAs (22%) had an informal understanding (TERI 2015). Moreover, these CCAs comprise of isolated forest fragments (average size is 500 ha) and only a handful form part of a larger network of community forests. Through this paper, we would like to highlight the success story of implementing Satoyama Initiative by mainstreaming Community-Conserved Areas (CCAs) for conservation, enhanced productivity through ecosystem services and livelihood generation in the State of Nagaland in India.

METHODOLOGY

Study site

Three villages- Sukhai, Ghukhuyi and Kivikhu lying in the southern region of Satakha block of the Zunheboto district in the state of Nagaland were selected as a pilot site under the work initiated by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) with support from Conservation International (CI) Japan via a Global Environment Facility (GEF)-Satoyama grant. The pilot site lies in the heart of Nagaland at an altitude of 1900 m and has sub-tropical wet hill forest primarily overlapping with the sub-tropical pine forest. The flora consists of large trees including Gmelina arborea, Melia composite, Terminalia myriocarpa, Artocarpus chaplasa, Chukrasia tabularis, Duabanga sonneratoides, Anthocephalus cadamba, Michelia champaca, Pinus petula, Pinus kesiya and Albizia procera while the dominant orchid species are Dendrobium, Bulbophyllum, Calanthe, Coelegyne, Liparis, Eria, Cymbidium, Oberonia, Pholidota, Goodyera, Habenaria and Peristylus. The pilot site acts as an important green corridor between the biodiversity-rich forests of Satoi range and Ghosu bird sanctuary and harbours endangered and threatened species like the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) and Chinese Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla). The river Tizu which flows through to these villages harbors a number of IUCN Red List fish species.

The pilot villages are dominated by the Sema tribe and the economy is largely agriculture and forest-centered. Though farming is mainly for subsistence, high dependence prevails on the other abundant resources of jhum (shifting cultivation) lands which include timber, medicinal plants and non-timber forests products. Wildlife is an important resource for the communities and is exploited for various reasons, including food, additional income, and cultural practices and as a sport. The overall Satoyama landscape comprises of a mosaic of different vegetation types and can be broadly categorized as primary forests, secondary forests, jhum land, terrace fields and plantations.

Figure 1. Project landscape and habitat features including forests, jhum fields and rice terraces

Figure 2. Map of the indicating location reference of the pilot site

Importance of Satoyama landscape and associated challenges

The Satoyama landscape of Zunheboto provides the local people with almost all of their daily subsistence and survival needs, apart from contributing to their rich cultural heritage, folklore and traditions. The landscapes of this area consist of diverse elements- Subtropical forests interspersed with jhum (shifting cultivation) fields and differentially aged, regenerating jhum fallows. Consequently, the people farm in the forest and the two are perceived to be inextricably linked by the local communities. The forests provide enormous provisioning benefits to the local communities in terms of ecosystem services such as timber, fuelwood and forest products. Food production through provisional ecosystem services is enhanced owing to their location with the forests (for example through enhanced pollination, water flows, nutrient enrichment, natural fertilizers). The jhum fields sustain a diversity of local varieties of crops including Maize, millets and Job’s tears (Coix spp.) that feed the people and their livestock. The forests also provide shade and moisture to horticultural crops like cardamom that are gaining popularity owing to their quick and sure returns. Several trees are planted on the private land adjacent to the forests that are economically important to the communities and are sold for timber or fuelwood. The Tizu River flowing through their lands irrigates their fields and forests and provides them with fish. The silt it brings assists in enhancing nutrients of the agricultural lands. In the valley areas adjoining the rivers, people also grow paddy in a pani-kheti system (terrace farming). Local land races are preferred and grown including Miyeghu which is a local paddy variety, Naga Mircha (Capsicum chinense) and the Nagaland Tree Tomato or Tamarillo (Cyphomandra betacca) that have recently acquired the Geographical Indication (GI) tag as directed by the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. The communities also maintain home gardens which comprises of vegetable and fruit plants and trees. These home gardens are not only a source of important food groups in the diet of the local people, but also help in carbon sequestration.

Traditionally, the Naga tribes had an intimate relationship with nature based on a foundation of the interconnectedness of God, people and nature. This is reflected in their rich folklore on the plants and animals of their forests. Some of these stories underline the ecological role that animals play in the ecosystem and their contribution to ‘ecosystem services’ for human beings. For example, the role of the earthworm in enhancing soil fertility is transmitted through a folktale (TERI, 2017). The value of their SEPLs was culturally realized and codified through wise use-for example the killing of pregnant animals and birds was a taboo that would bring misfortune to the hunter and his family. Fishing and the use of certain poisonous roots and leaves that kill fishes in the rivers or springs during the spawning season were also restricted (Lkr & Martemjen, 2014). The Naga people in general consider all land to be sacred. Jhuming or shifting cultivation involves clearing the land and burning the jungle, so people propitiate the spirit with rice, crabs and rice beer to beg for forgiveness for the many animals, plants, birds and reptiles that might be inadvertently harmed. The entire lives of the Sema people revolve around their forest-farm landscape. All the cultural festivals of the local people are linked to their agricultural calendar and the Sema people’s agricultural calendar in turn is attuned to nature, guided by the movement of the stars or of birds-their migration patterns, breeding seasons and songs. For example, the sowing of paddy is initiated only when the constellation of Orion (Phogwosiilesipfemi) is at its zenith or after the Kashopapu, a species of cuckoo is heard calling (Hutton 1921a). The two main festivals of the Sema tribe are Tuluni and Ahuna. Tuluni held on July 8 each year is marked with feasts as the occasion occurs in the bountiful season of the year while Ahuna held on November 14, is a traditional post-harvest festival signifying completion of successful agricultural work and sowing of next crop.

For the local Sema communities, a vibrant well-functioning Satoyama landscape implies that abundant wild fauna is present in their forests, and easily sighted for bushmeat when they jhum their fields, and that fish catches are abundant, large-sized and diverse (consisting of many species). Forests are protected at the top of hills so that their watershed services are enhanced. Traditionally, lengthening of the jhum cycle provides improved scope for natural biodiversity to regenerate. This is an extremely positive sign as jhuming is an excellent way to protect forests and associated biodiversity and yet produce crops, provided that long fallow periods allow for the forest to regrow. Amongst Sema tribals, fifteen to twenty years of jhum cycle was considered to be ideal, though seven to nine years is considered to be the shortest time in which the land is fit for cultivation. In particular land near the village tends to be left for the shortest time, since it is the easiest to cultivate (Hutton 1921a).

Figure 3. Forests, Tizu river, Terrace farming & Jhum cultivation representing Satoyama landscape

The current issues and challenges for the communities in managing the landscape mainly comprise of decreasing jhum cycles. Earlier when a forest patch was cleared, each patch was cultivated for only one to two years and then left to regenerate for upwards of 15 years. However the decreasing jhum cycles at present (less than seven years and often only for three to five years) prevent effective regeneration and leads to much soil erosion. In the State of Nagaland, out of total geographical area of 16,579 sq. km, approximately 937 sq. km is cleared annually for jhum cultivation in the state. Normally, the land is cropped for two years and thereafter allowed to lapse back into fallow. Paddy (rice) is the main crop in shifting cultivation. Shifting cultivation being carried out in approx. 5,229 ha (i.e. 31.5% of total wasteland) leads to burning of vegetation, soil erosion, wetland siltation, and clearing of natural vegetation (Nagaland SAPCC, 2012). However, with the increasing trend of urban migration, increasing education levels, and availability of alternative livelihoods, anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of farmers involved in Jhum have been decreasing during the past decade. An internal study carried out by NEPED in 2011 indicates that jhum cultivation area has decreased from 1.87 million ha in 2003 to 1.2 million hectares in 2005–06. If this trend continues, shifting cultivation may become viable but the practice itself may face extinction, which may not be a desirable outcome.

The local communities are dependent on forests for food, shelter, water, fuel, fodder, and medicines. Forests are abundant and provide for timber and fuel wood for the villagers. They also collect varieties of non-timber forest produce (NTFP) from forests that are available almost all round the year and meet a major part of a villager’s food. It is also a source of cash for the rural households (Nagaland SAPCC, 2012). Given the dependence of the local community on forest cover for a variety of provisioning and regulating ecosystem services, loss of forest cover has affected agriculture and the availability of water for domestic and agricultural use. The current firewood consumption in Nagaland is about 8.7 million cubic meters assuring the tree stand volume to approximately equivalent to that of jhum which is 188m³ trees from 46090 ha of wood. The demand of fire wood for fuel has increased three fold as compared to the early 1970’s in Nagaland. As per the latest report, the state has shown a decreasing trend accounting to a total loss of forest cover of 450 sq km (ISFR 2017). . Inspite of heavy pressures, the forest cover of Nagaland is 77.62% which is much higher than the minimum of 66% as envisaged in national forest policy of 1988.

With growing human population, increased accessibility to remote forests and adoption of modern traps and guns, hunting has become a severe global problem, particularly in Nagaland. While Indian wildlife laws prohibit hunting of virtually all large wild animals, in several parts of North-Eastern parts of India including Nagaland that are dominated by indigenous tribal communities, these laws have largely been ineffective due to cultural traditions of hunting for meat, perceived medicinal and ritual value, and the community ownership of the forests. Since most of the animals are considered edible, hunting and poaching for meat is a serious threat to the survival of wildlife especially the endangered ones. Decrease of habitat and improvement of fire-arms have worsened the situation. Local communities living in the vicinity of forests depend on wildlife for livelihood and income generation. Aggressive fishing using poisons (such as bleach and lime powder), dynamite and electrocution using battery packs has also led to reduction in fish populations of the Tizu River flowing adjacent to the pilot villages. The fear of losing all the fish and the natural ecosystem is one of the reasons that led to local communities declaring a reserve in their landscape. As a wise-use practice, they believe that fish and other animal species breed in the reserved areas and their populations are revitalized and replenished over time.

Figure 4. Jhum cultivation, excessive logging in forests and skulls of hunted wild animals on display

Genesis of developing Joint Community Conserved Area in Zunheboto district, Nagaland

In 2002, the village of Sukhai in Zunheboto district, realizing that it had undergone considerable transformation in the landscape, in its land use and cropping patterns, its use of fishing methods and in its approach to conservation, passed a notification that puts a complete ban on hunting and fishing, felling of trees and protects the area’s biodiversity. “Azhoqha and Yayi” area (located in the far south of the village) earlier covered under jhum cultivation, were protected so as to safeguard the natural resources including living and non-living resources and maintain it for present and future generations. However, due to an informal understanding and absence of a well-delineated program to safeguard ecosystems and conserve biodiversity led to an unsuccessful attempt to execute the ban. This movement was once again revived in 2015 when our organization-TERI was conducting a study document the CCAs in Nagaland and was approached by the Sukhai village council to assist them in conserving their landscape. Since Sukhai village is the parent village of other villages including Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi that migrated away from it in the past and settled on the sides it was imperative to garner their support as the natural resources like forests, rivers and biodiversity is shared beyond village boundaries. Hence, to ensure conservation of large contiguous forest areas, it was decided to mobilise support to link the community conservation areas, revive traditional conservation practices, carry out ecological assessments of these CCAs, develop community-based ecotourism initiatives and formalise and mainstream a network of CCAs along with the Nagaland Government and the State Forest Department.

DESCRIPTION OF ACTIVITIES

Formation & formalization of joint Community Conservation Areas & joint CCA management committee

The three pilot villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi had kept aside parcels of land as reserve forests since time immemorial; however this type of conservation adopted by the village was based on an informal understanding and the communities were passively hunting and fishing in the reserve due to lack of compliance and effective implementation. Hence several deliberations were held with the communities of the three pilot villages in order to increase awareness of threats and integrated approaches at the community and stakeholder level. This was achieved through participatory planning, knowledge sharing, and capacity building. The communities through engagement were convinced that there was a strong need to manage the resources collectively and efficiently. Later, each of the individual three CCAs were delineated and mapped and the boundaries were well-defined through demarcation, digitization and participatory mapping. This resulted in larger contiguous patches of forests areas along with the unique endemic biodiversity they support to be managed through formation of a ‘Joint CCA Management Committee’. The communities were quick to form Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network (TVBCLN) – a formal local CCA Management Committee that declared and enforced a blanket ban on hunting wild animals and birds, ban on fishing by use of explosives, chemicals and generators, strict prohibition of cutting of fire-wood/ felling of trees as well as collection of canes and other non-timber forest products for domestic and/ or commercial purposes in the CCAs.

Role of Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network (TVBCLN) in conservation education and sensitization

Around 35 sensitization campaigns were organized within the three pilot villages, with the neighboring villages and on other community platforms like the local festivals thus reaching out to a total of around 1500 individuals directly along with a positive impact on more than 15000 individuals indirectly living in the vicinity of the project site. The various forms of conservation education and sensitization programs included setting up informative stalls at local Ahuna festival, organizing awareness programs with key stakeholders like church groups, schools & education centres, carrying out plantations of local varieties, celebrating key day’s like the World Biodiversity day, World Environment Day etc. and organizing dedicated conservation themed events like the ‘Chengu[3] festival’. Also scientific publications, popular articles as well as websites (http://nagalandcca.org/ and http://gef-satoyama.net/) have helped to gain the attention of various stakeholders and boosted the engagement. In addition, exposure visits were undertaken for the community members to the neighboring states to showcase similar case studies, success stories and best practices with respect to community conservation.

Training of youth in biodiversity assessments & documentation of indigenous traditional knowledge

Biodiversity surveys by local communities have strengthened interest in conservation. The youth have been trained in documentation of flora and fauna by experts and currently they share pictures of wildlife taken by them on a “what’s app group.” Sightings are recorded in field registers and this has created a community of conservationists amongst the youth. These sightings are also important for research and are uploaded on websites such as birds and butterflies of India. Regular assessments can provide information on seasonal variations, range extensions and changes in population abundance. The local people can use this knowledge to develop their own resource monitoring methods. Moreover, camera traps can indicate whether RET (rare, endangered & threatened) species such as the Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii), are still sighted in the area. These surveys, by documenting unique, rare or special fauna have also acted as a catalyst to attract more outsiders to the area as ecotourists.

In Nagaland due to socio-political changes and development, traditional ecological knowledge is getting rapidly lost. Hence, it was imperative to document and preserve this rich ecological knowledge which can contribute to sustainable natural resource management in Nagaland. Keeping this in mind, efforts were made to document its people’s cultural connections with biodiversity in form of a People’s Biodiversity Register (PBR) for the three pilot villages. These registers, ‘contain comprehensive information on availability and knowledge of local biological resources, their medicinal or other use, or any other traditional knowledge associated with them’(Gadgil et al., 2005). Thus the PBRs prepared for the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi document the folklore, traditional knowledge, ecology, biodiversity and cultural practices of the local communities and help codify the oral knowledge of the local communities.

Alternative livelihood opportunities

The youth of the three pilot villages along with the hunters from each village dependent on hunting for subsistence were targeted and trained as nature guides with other trainings in association with Air BnB and Titli Trust on hygiene & environment care in homestays, safety and security, housekeeping service and food and beverage service, maximizing sales and managing money, and low cost marketing. Two biodiversity meets have been organized in the landscape since the formation of Joint CCA and it has resulted in enhanced livelihood opportunities with the steady flow of tourists.

Figure 5. Training of communities on use of GPS to demarcate CCA boundaries & Preparation of village resource maps

Figure 6. Stalls setup during local festivals for awareness generation & public meetings conducted

Figure 7. Training of youth on biodiversity assessments, Blyth’s Tragopan (Tragopan blythii) & documentation of traditional biodiversity & associated knowledge

RESULTS

Over a short span of three years, the communities of the three villages of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi in Zunheboto district of Nagaland have formally declared around 939 hectares of biodiversity rich forest as community conservation area which is now being jointly managed by them (Table 1). However, apart from these CCAs, they have also banned hunting and destructive fishing across the entire landscape of their villages covering 3751 ha of forests and rivers. In general, each CCA on average is about 25% of the total landscape area owned by the village, which is quite large and has helped in acting as green corridors and safe haven for wildlife.

Table 1. Area of CCA and associated landscape

The blanket ban on hunting and destructive fishing has also resulted in conserving wildlife and revival of wild populations. Regular biodiversity surveys in the designated CCAs found an increase in the diversity of birds, reptiles, butterflies and moths with the current checklist listing 222 species of birds, 31 reptiles, 11 amphibians, 200 species of butterflies and more than 200 species of moths. This diversity is very high in comparison to the nearby patches of forest that do not receive protection. This rich biodiversity along with the associated traditional knowledge has been documented in form of People’s Biodiversity Registers (PBRs). It highlights the history of the Sema Nagas, the tribe inhabiting pilot villages, and their association with nature. The PBR also captures the links of the culture and the economy of the Sema people with their local biodiversity. By doing so, local communities’ knowledge about their biological heritage is now registered and a commitment among them to conserve their rich traditions has been fostered.

The awareness programs and sensitization conducted by TVBLCN has led to many more villages urging a replication of these methods to manage their Satoyama landscapes, the latest being Chipoketa village, adjoining Kivikhu village, which is dominated by the Chakesang community. Taking cognizance of the efforts made by TVBLCN, the state government, local agencies and various village councils are now inviting the community members of the three pilot villages as resource persons in order to motivate, guide and lead the way for others. TVBLCN with help from TERI and Titli Trust has also managed to put up signboards and create informative material with a focus on local biodiversity.

With a focus on alternative livelihood options and enhancing income of the hunters & forest dependent families, two biodiversity meets have been organized to learn about and document the biodiversity of Tizu Valley Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Network comprising the villages of Sukhai, Ghukhuyi and Kivikhu in Zunheboto District, Nagaland and to initiate butterfly and bird tourism in these pilot villages. The visitors participated in the biodiversity surveys, stayed in local homestays, tasted sumptuous local cuisine, watched the traditional Sema dances and engaged with the local community to understand their activities to conserve their natural resources. Not only the presence of the visitors has boosted nature-based ecotourism, but the biodiversity assessments have also further added to the knowledge of the biodiversity of Nagaland.

Figure 8. Distinct CCA on right side of Tizu river and Jhum cultivation on left

Figure 9. (Left to Right) Eco-tourists in CCA, GIS map of CCAs & PBR of village Sukhai

CONCLUSION

The dominant paradigm of wildlife conservation, both globally, and in India is the creation of protected areas, where access to forest resources is restricted or highly regulated and local communities have little say in their management or in decision making. Such approaches, while helping to prevent conversion of land to alternative land uses, frequently conflicts with the livelihood concerns of local communities and puts their needs in direct competition with the conservation needs of wildlife. Hence these communities have no incentive to invest in conservation and conflict situations arise particularly where people not only are unable to realize their subsistence needs but additionally are subject to the depredations of wildlife. This situation has eroded support for the exclusionary or ‘fortress’ approach to conservation and buttressed support for more people-friendly and inclusive regimes for conservation including community conservation. The status and sustainability of CCAs is critically dependent on the ability of local communities to make decisions about land and resource uses, hold secure tenure and exclude outsiders from appropriating resources. Some of the most important factors contributing to the effectiveness of CCAs in the region today are the statutory mechanisms for a) collective and equitable decision-making and representation at the community level and b) communal ownership of land. While conservation policy and legislation is important, it is this overall local governance, the land tenure, and the institutional environment that is most critical to the success of CCAs (Blomley et.al. 2007).

Nagaland (along with other states of the North-East of India) has an advantage as constitutional provisions allow customary management of resources. Moreover, much of forest ownership lies in the hands of individuals, clans, councils and communities. The communities of Nagaland, therefore, have the flexibility of defining the boundaries, the interventions and the management patterns of these CCAs, thereby possessing all the necessary conditions for effective governance. While these CCAs offer much potential, the reality is that there are no panaceas for sustainable governance of natural resources a (e.g. Ostrom, 2007) and the issues and problems depend on the local attributes of resource systems, resources units, governance and actors (Ostrom, 2009). Nevertheless, this plurality of social-ecological systems in Nagaland is itself strength as communities can tailor their conservation practices to the availability of land (forests, agriculture), the needs of local populations, the state of wildlife populations and the resource base, and their own needs and traditions. Consequently, adaptability can be the hallmark of CCAs in Nagaland, as these areas are managed for a combination of cultural, utilitarian and aesthetic purposes.

One important lesson through this project is that if communities are well informed and empowered, they can take steps to protect their natural resources and use them judiciously. The project directly helped the communities in rejuvenating as well as strengthening the age-old practice of conserving community forests through mobilization and building synergies. The project also responded to the critical needs of the pilot area by documenting the traditional knowledge and raising awareness of impacts of anthropogenic activities on the biodiversity and ecosystem services of the community conserved areas, and its ripple effect on the socio-economic and cultural lifestyle of the Sema community. Again, the project through its effort to generate alternative livelihoods built the capacity of communities on ecotourism and is contributing to biodiversity conservation. The positive impacts of the project activities were evident at the end of the project where the communities reported increases in the protection of natural resources after the formation of a joint CCA and improvement in management of common resources. The elders were satisfied with the documentation of their traditional and cultural indigenous knowledge in the People's Biodiversity Registers (PBRs) while the youth, women groups and the marginalized members of the community reported increases in their household income due to ecotourism. The protection of a stretch of Tizu River passing along the boundary of CCA also resulted in increase of fish-catch downstream.

This project is just the start of what we hope will be a movement for conservation in the State of Nagaland. Long term sustainability, enhanced governance and effective conservation outcomes for wild fauna and flora, however, require sustained effort, motivation, awareness and capacity building. To ensure the future of Nagaland’s CCAs and thereby its biodiversity, a multi-pronged approach including financial support, legal recognition and long-term monitoring is required. Furthermore, local communities must be trained to monitor their resources, and to develop nature based tourism which will help generate support for conservation. The network of CCAs in Nagaland provides a wonderful example of a fledgling people’s movement for conservation that deserves to be strengthened and supported.

We are indebted to the local communities of Sukhai, Kivikhu and Ghukhuyi who have shown the way for managing landscapes and ensuring sustainability of the initiatives post project period. The local communities now patrol their forests and prevent both outsiders and people from their own villages from hunting and fishing. They also share pictures of those disobeying their rules on a what’s app group for quick action, and educate and motivate the people of other villages to eschew hunting. The Tizu Valley Network further supports education and sensitization and livelihood activities. Moreover, the government has taken notice of this initiative and has come forward to support it by developing the area into a community reserve under the Indian (Wildlife) Protection Act, for which limited funding is available. This will help in upscaling of activities initiated by the communities by formalization and mainstreaming of a network of CCAs in the State which are at par with India’s Protected Area (PA) network in conjunction with the Nagaland Government and Forest Department.

REFERENCES

Blomley, R., Nelson, F., Martin, A. and Ngobo, M. 2007. Community Conserved Areas: A review of status and needs in selected countries of central and eastern Africa. Report for Cenesta and IUCN/TILCEPA.

Forest Survey of India (2017), State of Forest Report. Forest Survey of India, Dehradun.

Hutton, J.H. 1921. The Sumi Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Lkr, L.and Martemjen. 2014. Biodiversity conservation ethos in Naga folklore and folksongs. International Journal of Advanced Research 2: 1008-1013.

Nagaland State Acton Plan on Climate Change. 2012. Government of Nagaland and GIZ (Deutsche Gesellscha for Internatonale Zusarnmenarbeit GmbH - German Internatonal Cooperaton, India). pp: 187.

Ostrom, E. 2007. A Diagnostic Approach for Going Beyond Panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(39):15181–15187.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 325:419–422.

Pathak, N and N. Hazarika. 2012. India: Community conservation at a crossroads In: Dudley, N and S. Stolton (eds.); Protected Landscapes and Wild Biodiversity, Volume 3 in the Values of Protected Landscapes and Seascapes Series, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 104pp.

Pathak, N (ed.).2009. Community-Conserved Areas in India –A Directory, Kalpavriksh, Pune.