ABSTRACT

The Malaysian tea industry, historically vibrant since its inception in 1929, has faced a significant transformation over the years, adapting to local and global market demands. This paper explores the shifts in tea production, trade, and consumption patterns within Malaysia and in the context of global trends. Even though the increase in global tea production is led predominantly by China, Malaysia’s tea production has declined due to labor shortages and environmental challenges in its traditional highland areas. Concurrently, Malaysia’s role in the international tea market has evolved, with substantial exports to Asian neighbors and increased imports, particularly from Indonesia and China. The study highlights the dynamic interplay between production constraints and emerging market opportunities, including the rising local demand for premium teas. This report underscores the strategic adaptations necessary for Malaysia to sustain and grow its tea industry amidst changing global and domestic landscapes.

Keywords: Tea industry, tea production, agricultural trade, global challenges, market demand

INTRODUCTION

Tea plants have been growing in Malaysia since 1929. Since then, tea cultivation has grown with the involvement of many companies that cultivate tea not only on high ground but also in lowland areas in Malaysia. Two clones of tea are grown all over the world: Camellia assamica and Camellia sinensis. The Camellia assamica clone is the most popular and suitable clone grown in Malaysia as well as in most tropical tea-producing countries. The leaves of this clone are more aromatic than the clones of Camellia sinensis and have larger and wider leaves. Camellia sinensis clones are often planted in mountainous areas because they are resistant to cold weather and low temperatures.

After more than 90 years of tea growing in Malaysia, the tea industry is seen as unchanged despite rising demand. Among the factors contributing to the slow growth in this industry are labor-intensive planting activities and the declining involvement of industry players. Therefore, we aim to assess the development of the tea industry in Malaysia from the point of view of production, trade and demand. The article begins with a scenario of the tea production and cultivation area in the world, followed by the production, cultivation area, import and export of Malaysian tea. Next, the description of world tea demand, as well as Malaysia’s demand, is described, followed by per capita consumption.

BACKGROUND

World tea production

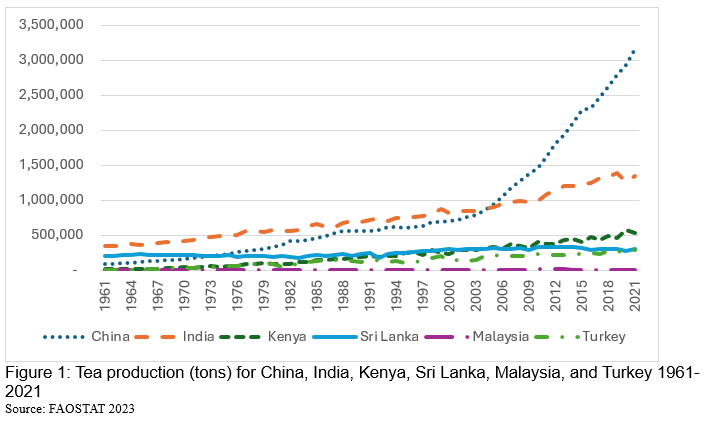

World tea production was 9.97 million tons in 2021, more than eight times higher than in 1961 (Figure 1). The increase in world tea production is strongly influenced by the production of tea from China, especially after 2004. In the early 1960s, world tea production was dominated by India, China and Sri Lanka. However, in 1975, China was seen to be starting to overtake Sri Lanka and then ahead of India as the largest producer in 2006. The drastic increase in production since 2004 has made China capable of producing 3.16 million tons of tea a year by 2021. This is far ahead of other countries like India, which only produces 1.35 million tons a year.

Kenya became one of the third largest exporters in 2007, with a total production of 458,000 tons in 2018. The increase in tea production in Kenya was driven by the involvement of Unilever company, which opened a tea plantation area under contract to supply tea leaves to the company. Another country that showed a high increase in tea production is the country of Turkey. Tea production in Turkey has grown slowly but is closer to Sri Lanka’s total tea production in 2018, with a total Turkish tea production of 290,000 tons compared to 299,000 tons from Sri Lanka. Malaysia became the 23rd largest tea producer in the world, with a total production of 10,800 tons in 2018.

The extent of the world’s tea planting

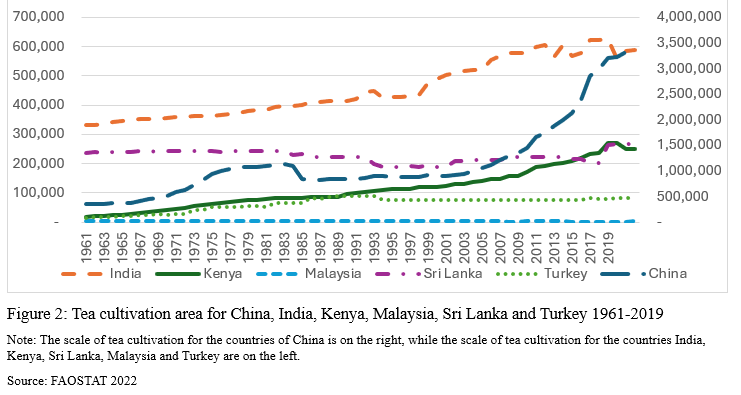

The total area of tea plantations in the world is 8.6 million hectares. The extent of tea planting is strongly influenced by the extent of the tea planting area in China. The up and down of the world’s tea areas is almost the same as the growth of China (Figure 2). The high production of tea in China is due to the increase in planting area since 1968. The country has recorded the largest increase in tea plantation area, from 354,979 hectares in 1961 to 3.4 million in 2022. There was a decrease in tea cultivation in China from 1.1 million hectares in 1984 to 834,313 in 1985 due to a reduction in exports to European countries that year. The drastic increase in tea plantations started in 2007, going from 1.29 million hectares to 3.4 million in 2021. The situation has resulted in the total area in China being five times larger than the area of tea cultivation in India in 2019. The extent of tea cultivation in other major producing countries has not changed significantly except in India and Kenya. However, the increase in extent in India and Kenya is low compared to the very high increment in China. The tea plantation area in Malaysia was ranked 29th in 2018, with an area of 2,083 hectares.

PRODUCTION, EXPORT, AND IMPORT

Domestic production of tea in Malaysia

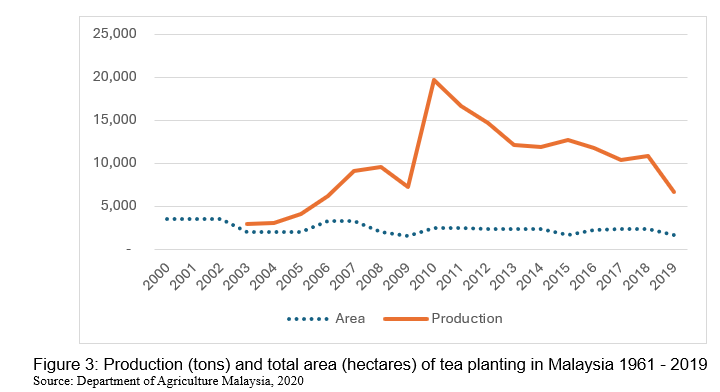

Tea cultivation in Malaysia has been started since 1929, but data are obtained only from 1961. The tea plantation area in Malaysia gradually decreased from 3,521 hectares in 1961 to 1,440 hectares in 2019 (Figure 3). The decline in planting areas is due to the closure of companies that operate tea farms in Pahang, Selangor, Johor, and Sarawak, which is driven by the difficulty of obtaining labor. Most of the workers are foreigners, mainly engaged in farm-related work like picking tea leaves and taking them to the collection centre. The tea plantation area was initially concentrated in Pahang, Selangor, Perak, Johor, Kedah, Sabah and Sarawak. For now, tea is only grown in Pahang, Selangor, and Sabah, with the reduction of tea planting areas having begun in 2003. The main tea-growing area in Malaysia has also experienced a decline in area. Tea planting involves only few companies, but there are also small farmers involved in tea plants in Sarawak.

Although the area of tea planting has decreased, tea production has increased from 2,635 tons in 1961 to 10,800 tons in 2018 before falling to 6,600 tons in 2019. The decline in tea production between 1999 and 2005 was because of El Nino, which disrupted rainfall and affected the growth of tea tree leaves. Among the factors of the decline in tea production after 2012 are the attacks of disease and soil infertility (Mansur, 2019).

The export of tea

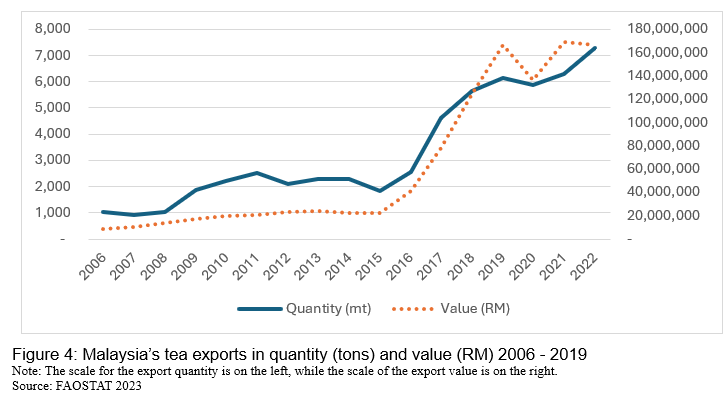

Malaysia is among the world’s tea exporter, mainly to Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Brunei as well as other 83 countries. Export growth was at a moderate rate from 2006 to 2015, from 1,035 tons in 2006 to 2,199 tons in 2010 (Figure 4). Exports reached 2,503 tons in 2011 but subsequently declined in 2015. Exports increased extremely from 2016 to 6,134 tons in 2019, then increased again up to 7,291 in 2022. The increase in the amount of tea exported has affected the tea export value of RM166 million (US$37.9 million) in 2019 compared to just RM22 million (US$5.03 million) in 2015. The increase in export value was also influenced by the average price per ton, which increased from RM10,441/ton (US$2,385.73/ton) in 2013 to RM16,936/ton (US$3,869.82/ton) in 2017 and continued to rise to RM27,081/ton (US$6,187.77/ton) in 2019.

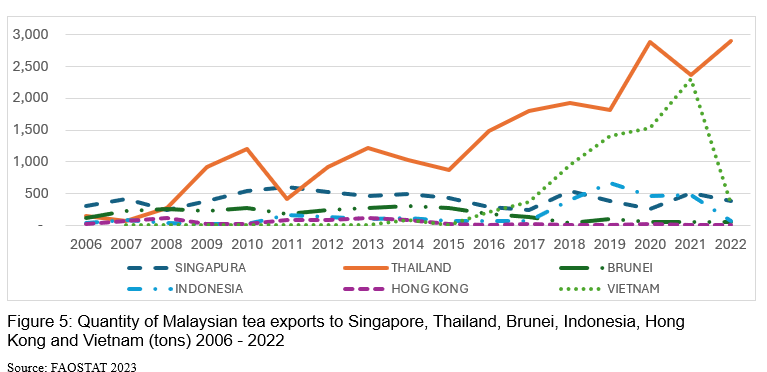

Malaysia’s largest exports are to neighboring Thailand, which had a volume of 2,897 tons in 2022 (Figure 5). Exports to Thailand have been consistent and increasing since 2006, except in 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2021. The second largest importer until 2015 is Singapore, which had a total of 432 tons. However, starting from 2018, the value of exports to Vietnam exceeded Singapore by a total of 942 tons. Exports to Indonesia and Hong Kong have also seen a constant rise since 2016, when the volume of exports to Indonesia increased from 70 tons in 2016 to 661 tons in 2019, while exports to Hong Kong increased from 10 tons in 2016 to 297 tons in 2019.

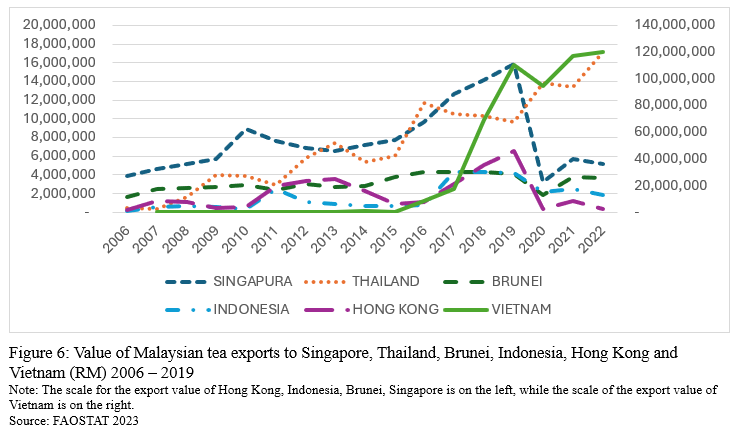

Although the quantity of exports to Thailand is the highest, the value of exports to Vietnam was higher than Thailand starting from 2018 (Figure 6). The value of exports to Vietnam was highest in 2021 and 2022, with a value of RM117.2 million (US$26.8 million) and RM120.1 million (US$27.5 million), respectively. Singapore’s export value reached RM15.9 million (US$3.6 million) due to increased export volume in 2019. The value of exports to Thailand was the highest in 2016 at RM11.7 million (US$2.7 million) but subsequently dropped to RM9.6 million (US$2.2 million) in 2019, then boost up to RM17.1 million (US$3.9 million) in 2022.

The import of tea

Malaysia imports more tea than its exports, although Malaysia produce itself. The import trend for tea is set to grow steadily, with a total of 14,829 tons in 2006, up to 32,457 tons in 2022 (Figure 7). The volume of tea imports increased suddenly in 2014 to 25,467 tons and then dropped to 21,288 tons the following year. The value of tea imports reached RM450.8 million (US$103.04 million) in 2019 compared to just RM74.5 million (US$17.02 million) in 2006. The import value trend also increased progressively from 2006 to 2015 but declined in 2008 and 2011. The growth in the value of tea imports was higher from 2016 to 2019 than from 2006 to 2015.

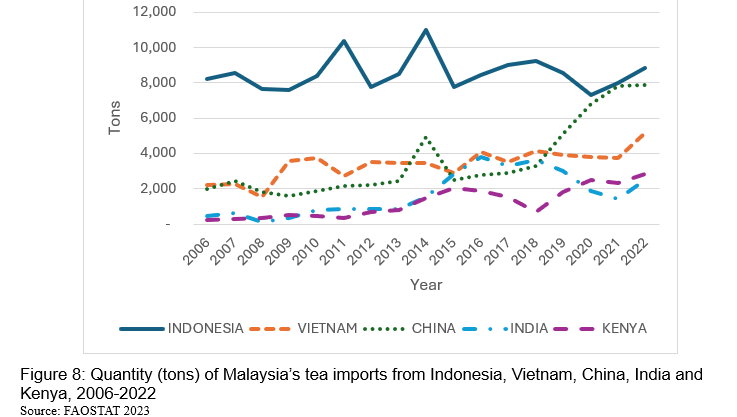

The largest quantity imported by Malaysia is from Indonesia, with a total of approximately 8,000 to 10,000 tons per year as of 2006. The quantity of imports from Indonesia is stable except for an increase in 2012 and 2014 to 10,980 tons. The second largest tea imports are from China, which increased from 1,986 tons in 2006 to 5,202 tons in 2019, then reached nearly 8,000 tons in 2021 and 2022, higher than that from Vietnam. Imports from Vietnam slightly exceeded China in 2006 (2.234 tons) and surpassed China between 2009 and 2013 and from 2015 to 2018 (Figure 8).

Imports from India were around 300 to 800 tons from 2006 to 2013, but subsequently increased from 1,520 tons in 2014 to 3,772 tons in 2016 and decreased to 3,067 tons in 2019. Imports from Kenya also had a trend almost identical to that of India from 2006 to 2014. The quantity of imports from Kenya was around 200 to 800 tons from 2006 to 2013, which subsequently increased to as much as 2,042 tons in 2015, dropped to 742 tons in 2018, and increased again up to 2,840 tons in 2022 (Figure 8).

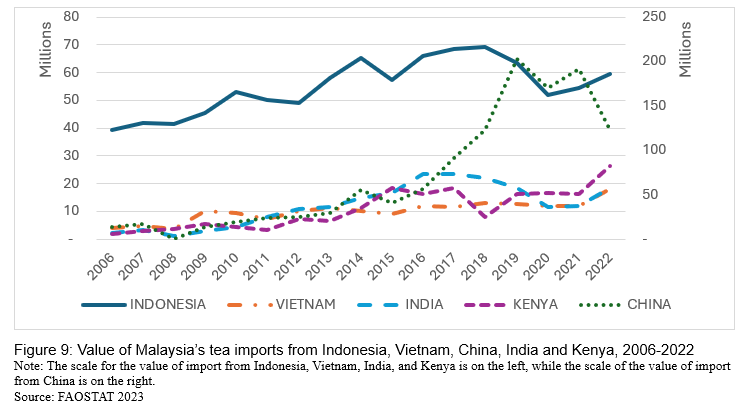

Figure 9 shows Malaysia’s tea import value from China surpassed that from Indonesia since 2017, with a value of RM90.6 million (US$20.7M) to reach RM202.3 million (US$46.2M) in 2019, although the import quantity is the largest from Indonesia. The value of imports from Indonesia was stable from 2006 to 2018, before it dropped to lower than that of China in 2020 and 2021. The value of import from India and Kenya increased from 2006 to 2016 and then remained stable until 2019 for Kenya, but gradually dropped from India, while the value of imports from Vietnam has been stable since 2006.

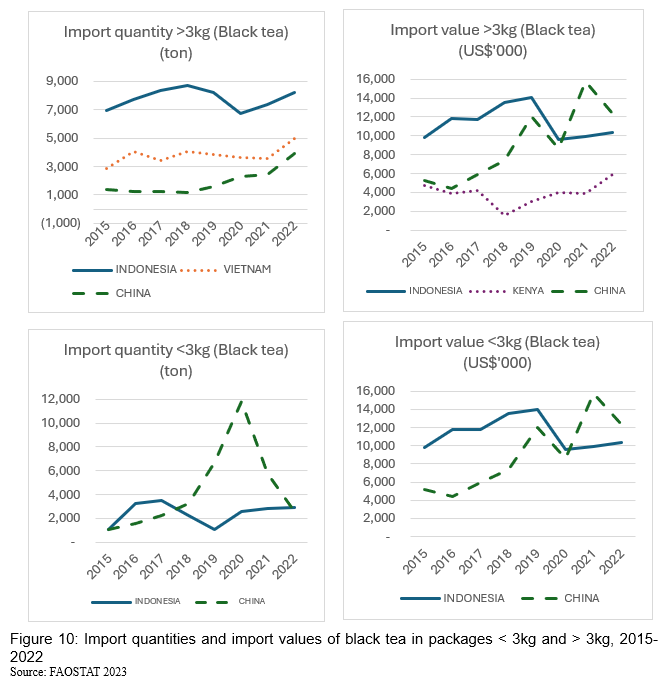

Malaysia imports two main types of tea: black tea and green tea, based on domestic demand. Both types of tea (black and green tea) are imported in packages of less than 3 kg and packages of over 3 kg. Most of the black tea imported in packages exceeding 3 kg is from Indonesia, with the number of imports increasing from 6,913 tons in 2015 to 8,205 tons in 2022. Vietnam is the second largest exporter to Malaysia, followed by India, China and Kenya. The quantity of imported black tea in a package of less than 3 kg is dominated by Indonesia and China. Nevertheless, the volume of imports from Indonesia has declined since 2018 and China surpassed the amount of import from Indonesia in 2021. Imports from Taiwan increased in 2019 to 232 tons, while imports from Sri Lanka fell slightly in 2016 and remained stable until 2019.

The import value of black tea for packages exceeding 3 kg is the highest from Indonesia due to the high quantity of imports. However, the value of imported black tea in packages of exceeding 3kg from China has risen compared to the quantity of imports starting from 2017. The value of tea imports from Vietnam and India is stable, while the value of tea imports from Kenya is declining. The value of imports from China for black tea in packages of less than 3 kg has risen to US$15.7 million in 2021. The decline in black tea imports in packages of less than 3 kg from Indonesia is consistent with the decrease in the value of imports from the country. The increase in the value of black tea imported in packages of less than 3kg from Taiwan is also in line with the increase in import quantities. The value of black tea imports in packages of less than 3 kg from India is not much less than the decrease in the quantity of imports from the country.

Demand for green tea in Malaysia is seen to rise through increased quantities of imports. China dominates green tea imports to Malaysia by exporting more than 1,000 tons of green tea in packages exceeding 3 kg and more than 2,000 tons for green tea packages less than 3 kg in 2020 and 2021. Increasing imports of green tea from China for both green tea products resulted in high and rising import values for these products.

The demand for tea

Per capita consumption of tea was the highest in Turkey, with 3.1 kg per capita, followed by Ireland (2.2kg), the United Kingdom (1.9kg), Iran (1.5kg), Russia (1.4kg), Maghribi (1.2kg) and New Zealand (1.2kg). Tea is used as a substitute for coffee, with a world consumption of 0.85kg per capita. The world’s demand for tea has shifted to premium tea, such as aromatic tea (such as strawberries and lemons), especially in developed countries. The consumers in developing countries are still focused on the black tea.

Tea consumption in Malaysia has increased from 18 million kilograms in 2007 to 29 million in 2017, an increase of 61%. Increment of tea consumption contributed to an increase in per capita consumption in Malaysia from 667g in 2007 to 910g in 2017, an increase of 36%. Factors of increased tea consumption in Malaysia are the increase in population, the existence of premium specialty tea stores such as Tealive and Chatime, and the opening out of the Mamak stall, which mostly sells “Teh Tarik”. Most Malaysians drink black tea, commonly consumed as milk tea, which represents 80% of tea consumption in Malaysia. Ready-to-drink innovation in the form of bottles and boxes with a variety of flavours is also become consumer choices. Large companies like Unilever, Yeo’s and Fraser & Neave (F&N) are producing tea drinks to increase the demand for tea among consumers of all ages. Other manufacturers produce green tea, white tea, and flavored teas like strawberry tea. In conjunction with that, starting from 2008, the tea imports duties have been lifted in parallel with the AFTA trade agreements that have been signed by ASEAN countries, including Malaysia. Tea import duties from China were also lifted in January 2010 to boost trade between the two countries.

SUMMARY

Based on the statistics assessed in this report, there is a transformation in the structure of the global and national tea industry. The structure of the world’s tea production, trade, and demand, including Malaysia’s, is increasing year by year. The world’s tea production and exports are dominated by China, which also showed an increment. Tea production from other countries has also increased, such as in India, Sri Lanka, and Kenya, but the growth in these countries is much lower than in China.

Tea production in Malaysia has been declining since 2012 since the closure of tea farms due to labor shortage. The labor-intensive harvesting activities, with the environmental challenges of mountainous planting areas, as well as the labor-demand competition from the vegetable industry in the high ground, affects the sustainability of Malaysia’s tea industry. Thus, tea production in Malaysia is concentrated in only few companies. Furthermore, disease problem and unproductive ageing trees are also causing the decline in production yield in Malaysia. Also, to meet domestic demand, Malaysia has imported tea mainly from Indonesia at a lower value than China. In addition, Malaysia primarily exports tea to Thailand, with export volumes increasing year over year. Although the quantity of tea exported to Vietnam has decreased since 2021, the export value remains high. These trends are influenced by changes in global demand and currency exchange rates.

The tea consumption in Malaysia is predominantly black tea, thus tea cultivation in lowland areas can be expanded to reduce imports. The expansion of tea plants in lowland areas is expected to encourage the involvement of small farmers. In addition, tea replanting needs to be performed to ensure the sustainability of the domestic tea supply. Exports of premium tea should be increased to developed countries since there is a changing demand for premium tea over black tea.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture Malaysia. (2020). Production and area of tea cultivation in Malaysia.

FAOSTAT. (2023). Cutivation area, production, exports, import by countries and by categories.

Mansur, K. (2019). Tea production in Malaysia: Culture versus challenges and prospect to Malaysian Economics. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Sciences, 3(4), 324-328.

Transformation of The Tea Industry in Malaysia

ABSTRACT

The Malaysian tea industry, historically vibrant since its inception in 1929, has faced a significant transformation over the years, adapting to local and global market demands. This paper explores the shifts in tea production, trade, and consumption patterns within Malaysia and in the context of global trends. Even though the increase in global tea production is led predominantly by China, Malaysia’s tea production has declined due to labor shortages and environmental challenges in its traditional highland areas. Concurrently, Malaysia’s role in the international tea market has evolved, with substantial exports to Asian neighbors and increased imports, particularly from Indonesia and China. The study highlights the dynamic interplay between production constraints and emerging market opportunities, including the rising local demand for premium teas. This report underscores the strategic adaptations necessary for Malaysia to sustain and grow its tea industry amidst changing global and domestic landscapes.

Keywords: Tea industry, tea production, agricultural trade, global challenges, market demand

INTRODUCTION

Tea plants have been growing in Malaysia since 1929. Since then, tea cultivation has grown with the involvement of many companies that cultivate tea not only on high ground but also in lowland areas in Malaysia. Two clones of tea are grown all over the world: Camellia assamica and Camellia sinensis. The Camellia assamica clone is the most popular and suitable clone grown in Malaysia as well as in most tropical tea-producing countries. The leaves of this clone are more aromatic than the clones of Camellia sinensis and have larger and wider leaves. Camellia sinensis clones are often planted in mountainous areas because they are resistant to cold weather and low temperatures.

After more than 90 years of tea growing in Malaysia, the tea industry is seen as unchanged despite rising demand. Among the factors contributing to the slow growth in this industry are labor-intensive planting activities and the declining involvement of industry players. Therefore, we aim to assess the development of the tea industry in Malaysia from the point of view of production, trade and demand. The article begins with a scenario of the tea production and cultivation area in the world, followed by the production, cultivation area, import and export of Malaysian tea. Next, the description of world tea demand, as well as Malaysia’s demand, is described, followed by per capita consumption.

BACKGROUND

World tea production

World tea production was 9.97 million tons in 2021, more than eight times higher than in 1961 (Figure 1). The increase in world tea production is strongly influenced by the production of tea from China, especially after 2004. In the early 1960s, world tea production was dominated by India, China and Sri Lanka. However, in 1975, China was seen to be starting to overtake Sri Lanka and then ahead of India as the largest producer in 2006. The drastic increase in production since 2004 has made China capable of producing 3.16 million tons of tea a year by 2021. This is far ahead of other countries like India, which only produces 1.35 million tons a year.

Kenya became one of the third largest exporters in 2007, with a total production of 458,000 tons in 2018. The increase in tea production in Kenya was driven by the involvement of Unilever company, which opened a tea plantation area under contract to supply tea leaves to the company. Another country that showed a high increase in tea production is the country of Turkey. Tea production in Turkey has grown slowly but is closer to Sri Lanka’s total tea production in 2018, with a total Turkish tea production of 290,000 tons compared to 299,000 tons from Sri Lanka. Malaysia became the 23rd largest tea producer in the world, with a total production of 10,800 tons in 2018.

The extent of the world’s tea planting

The total area of tea plantations in the world is 8.6 million hectares. The extent of tea planting is strongly influenced by the extent of the tea planting area in China. The up and down of the world’s tea areas is almost the same as the growth of China (Figure 2). The high production of tea in China is due to the increase in planting area since 1968. The country has recorded the largest increase in tea plantation area, from 354,979 hectares in 1961 to 3.4 million in 2022. There was a decrease in tea cultivation in China from 1.1 million hectares in 1984 to 834,313 in 1985 due to a reduction in exports to European countries that year. The drastic increase in tea plantations started in 2007, going from 1.29 million hectares to 3.4 million in 2021. The situation has resulted in the total area in China being five times larger than the area of tea cultivation in India in 2019. The extent of tea cultivation in other major producing countries has not changed significantly except in India and Kenya. However, the increase in extent in India and Kenya is low compared to the very high increment in China. The tea plantation area in Malaysia was ranked 29th in 2018, with an area of 2,083 hectares.

PRODUCTION, EXPORT, AND IMPORT

Domestic production of tea in Malaysia

Tea cultivation in Malaysia has been started since 1929, but data are obtained only from 1961. The tea plantation area in Malaysia gradually decreased from 3,521 hectares in 1961 to 1,440 hectares in 2019 (Figure 3). The decline in planting areas is due to the closure of companies that operate tea farms in Pahang, Selangor, Johor, and Sarawak, which is driven by the difficulty of obtaining labor. Most of the workers are foreigners, mainly engaged in farm-related work like picking tea leaves and taking them to the collection centre. The tea plantation area was initially concentrated in Pahang, Selangor, Perak, Johor, Kedah, Sabah and Sarawak. For now, tea is only grown in Pahang, Selangor, and Sabah, with the reduction of tea planting areas having begun in 2003. The main tea-growing area in Malaysia has also experienced a decline in area. Tea planting involves only few companies, but there are also small farmers involved in tea plants in Sarawak.

Although the area of tea planting has decreased, tea production has increased from 2,635 tons in 1961 to 10,800 tons in 2018 before falling to 6,600 tons in 2019. The decline in tea production between 1999 and 2005 was because of El Nino, which disrupted rainfall and affected the growth of tea tree leaves. Among the factors of the decline in tea production after 2012 are the attacks of disease and soil infertility (Mansur, 2019).

The export of tea

Malaysia is among the world’s tea exporter, mainly to Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Brunei as well as other 83 countries. Export growth was at a moderate rate from 2006 to 2015, from 1,035 tons in 2006 to 2,199 tons in 2010 (Figure 4). Exports reached 2,503 tons in 2011 but subsequently declined in 2015. Exports increased extremely from 2016 to 6,134 tons in 2019, then increased again up to 7,291 in 2022. The increase in the amount of tea exported has affected the tea export value of RM166 million (US$37.9 million) in 2019 compared to just RM22 million (US$5.03 million) in 2015. The increase in export value was also influenced by the average price per ton, which increased from RM10,441/ton (US$2,385.73/ton) in 2013 to RM16,936/ton (US$3,869.82/ton) in 2017 and continued to rise to RM27,081/ton (US$6,187.77/ton) in 2019.

Malaysia’s largest exports are to neighboring Thailand, which had a volume of 2,897 tons in 2022 (Figure 5). Exports to Thailand have been consistent and increasing since 2006, except in 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2021. The second largest importer until 2015 is Singapore, which had a total of 432 tons. However, starting from 2018, the value of exports to Vietnam exceeded Singapore by a total of 942 tons. Exports to Indonesia and Hong Kong have also seen a constant rise since 2016, when the volume of exports to Indonesia increased from 70 tons in 2016 to 661 tons in 2019, while exports to Hong Kong increased from 10 tons in 2016 to 297 tons in 2019.

Although the quantity of exports to Thailand is the highest, the value of exports to Vietnam was higher than Thailand starting from 2018 (Figure 6). The value of exports to Vietnam was highest in 2021 and 2022, with a value of RM117.2 million (US$26.8 million) and RM120.1 million (US$27.5 million), respectively. Singapore’s export value reached RM15.9 million (US$3.6 million) due to increased export volume in 2019. The value of exports to Thailand was the highest in 2016 at RM11.7 million (US$2.7 million) but subsequently dropped to RM9.6 million (US$2.2 million) in 2019, then boost up to RM17.1 million (US$3.9 million) in 2022.

The import of tea

Malaysia imports more tea than its exports, although Malaysia produce itself. The import trend for tea is set to grow steadily, with a total of 14,829 tons in 2006, up to 32,457 tons in 2022 (Figure 7). The volume of tea imports increased suddenly in 2014 to 25,467 tons and then dropped to 21,288 tons the following year. The value of tea imports reached RM450.8 million (US$103.04 million) in 2019 compared to just RM74.5 million (US$17.02 million) in 2006. The import value trend also increased progressively from 2006 to 2015 but declined in 2008 and 2011. The growth in the value of tea imports was higher from 2016 to 2019 than from 2006 to 2015.

The largest quantity imported by Malaysia is from Indonesia, with a total of approximately 8,000 to 10,000 tons per year as of 2006. The quantity of imports from Indonesia is stable except for an increase in 2012 and 2014 to 10,980 tons. The second largest tea imports are from China, which increased from 1,986 tons in 2006 to 5,202 tons in 2019, then reached nearly 8,000 tons in 2021 and 2022, higher than that from Vietnam. Imports from Vietnam slightly exceeded China in 2006 (2.234 tons) and surpassed China between 2009 and 2013 and from 2015 to 2018 (Figure 8).

Imports from India were around 300 to 800 tons from 2006 to 2013, but subsequently increased from 1,520 tons in 2014 to 3,772 tons in 2016 and decreased to 3,067 tons in 2019. Imports from Kenya also had a trend almost identical to that of India from 2006 to 2014. The quantity of imports from Kenya was around 200 to 800 tons from 2006 to 2013, which subsequently increased to as much as 2,042 tons in 2015, dropped to 742 tons in 2018, and increased again up to 2,840 tons in 2022 (Figure 8).

Figure 9 shows Malaysia’s tea import value from China surpassed that from Indonesia since 2017, with a value of RM90.6 million (US$20.7M) to reach RM202.3 million (US$46.2M) in 2019, although the import quantity is the largest from Indonesia. The value of imports from Indonesia was stable from 2006 to 2018, before it dropped to lower than that of China in 2020 and 2021. The value of import from India and Kenya increased from 2006 to 2016 and then remained stable until 2019 for Kenya, but gradually dropped from India, while the value of imports from Vietnam has been stable since 2006.

Malaysia imports two main types of tea: black tea and green tea, based on domestic demand. Both types of tea (black and green tea) are imported in packages of less than 3 kg and packages of over 3 kg. Most of the black tea imported in packages exceeding 3 kg is from Indonesia, with the number of imports increasing from 6,913 tons in 2015 to 8,205 tons in 2022. Vietnam is the second largest exporter to Malaysia, followed by India, China and Kenya. The quantity of imported black tea in a package of less than 3 kg is dominated by Indonesia and China. Nevertheless, the volume of imports from Indonesia has declined since 2018 and China surpassed the amount of import from Indonesia in 2021. Imports from Taiwan increased in 2019 to 232 tons, while imports from Sri Lanka fell slightly in 2016 and remained stable until 2019.

The import value of black tea for packages exceeding 3 kg is the highest from Indonesia due to the high quantity of imports. However, the value of imported black tea in packages of exceeding 3kg from China has risen compared to the quantity of imports starting from 2017. The value of tea imports from Vietnam and India is stable, while the value of tea imports from Kenya is declining. The value of imports from China for black tea in packages of less than 3 kg has risen to US$15.7 million in 2021. The decline in black tea imports in packages of less than 3 kg from Indonesia is consistent with the decrease in the value of imports from the country. The increase in the value of black tea imported in packages of less than 3kg from Taiwan is also in line with the increase in import quantities. The value of black tea imports in packages of less than 3 kg from India is not much less than the decrease in the quantity of imports from the country.

Demand for green tea in Malaysia is seen to rise through increased quantities of imports. China dominates green tea imports to Malaysia by exporting more than 1,000 tons of green tea in packages exceeding 3 kg and more than 2,000 tons for green tea packages less than 3 kg in 2020 and 2021. Increasing imports of green tea from China for both green tea products resulted in high and rising import values for these products.

The demand for tea

Per capita consumption of tea was the highest in Turkey, with 3.1 kg per capita, followed by Ireland (2.2kg), the United Kingdom (1.9kg), Iran (1.5kg), Russia (1.4kg), Maghribi (1.2kg) and New Zealand (1.2kg). Tea is used as a substitute for coffee, with a world consumption of 0.85kg per capita. The world’s demand for tea has shifted to premium tea, such as aromatic tea (such as strawberries and lemons), especially in developed countries. The consumers in developing countries are still focused on the black tea.

Tea consumption in Malaysia has increased from 18 million kilograms in 2007 to 29 million in 2017, an increase of 61%. Increment of tea consumption contributed to an increase in per capita consumption in Malaysia from 667g in 2007 to 910g in 2017, an increase of 36%. Factors of increased tea consumption in Malaysia are the increase in population, the existence of premium specialty tea stores such as Tealive and Chatime, and the opening out of the Mamak stall, which mostly sells “Teh Tarik”. Most Malaysians drink black tea, commonly consumed as milk tea, which represents 80% of tea consumption in Malaysia. Ready-to-drink innovation in the form of bottles and boxes with a variety of flavours is also become consumer choices. Large companies like Unilever, Yeo’s and Fraser & Neave (F&N) are producing tea drinks to increase the demand for tea among consumers of all ages. Other manufacturers produce green tea, white tea, and flavored teas like strawberry tea. In conjunction with that, starting from 2008, the tea imports duties have been lifted in parallel with the AFTA trade agreements that have been signed by ASEAN countries, including Malaysia. Tea import duties from China were also lifted in January 2010 to boost trade between the two countries.

SUMMARY

Based on the statistics assessed in this report, there is a transformation in the structure of the global and national tea industry. The structure of the world’s tea production, trade, and demand, including Malaysia’s, is increasing year by year. The world’s tea production and exports are dominated by China, which also showed an increment. Tea production from other countries has also increased, such as in India, Sri Lanka, and Kenya, but the growth in these countries is much lower than in China.

Tea production in Malaysia has been declining since 2012 since the closure of tea farms due to labor shortage. The labor-intensive harvesting activities, with the environmental challenges of mountainous planting areas, as well as the labor-demand competition from the vegetable industry in the high ground, affects the sustainability of Malaysia’s tea industry. Thus, tea production in Malaysia is concentrated in only few companies. Furthermore, disease problem and unproductive ageing trees are also causing the decline in production yield in Malaysia. Also, to meet domestic demand, Malaysia has imported tea mainly from Indonesia at a lower value than China. In addition, Malaysia primarily exports tea to Thailand, with export volumes increasing year over year. Although the quantity of tea exported to Vietnam has decreased since 2021, the export value remains high. These trends are influenced by changes in global demand and currency exchange rates.

The tea consumption in Malaysia is predominantly black tea, thus tea cultivation in lowland areas can be expanded to reduce imports. The expansion of tea plants in lowland areas is expected to encourage the involvement of small farmers. In addition, tea replanting needs to be performed to ensure the sustainability of the domestic tea supply. Exports of premium tea should be increased to developed countries since there is a changing demand for premium tea over black tea.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture Malaysia. (2020). Production and area of tea cultivation in Malaysia.

FAOSTAT. (2023). Cutivation area, production, exports, import by countries and by categories.

Mansur, K. (2019). Tea production in Malaysia: Culture versus challenges and prospect to Malaysian Economics. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Sciences, 3(4), 324-328.