ABSTRACT

Malaysia has always been a trading nation. Strategically located along the Straits of Malacca, it sits on a major shipping channel that connects the Indian Ocean to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east. Malaysia recognizes the importance of international trade and relations to the nation’s growth and development. Given Malaysia’s reliance on international trade, Malaysia has adopted liberal trade policies and highly emphasizes regional and bilateral trade agreements. According to the World Trade Organization, Malaysia is the world’s top 25th trading and exporting nation and 26th importing nation. Trade liberalization with the ASEAN regions helps Malaysia outsource its food supply, as the local production is insufficient to meet the local demand. In 2022, Malaysia imported more than 1.8 million tons or around 35% of its rice for its people. Malaysia also imported more than 680,000 tons of fruits, of which 22.8% comes from ASEAN countries. In the same year, Malaysia imported more than 1.8 million tons of vegetables, and out of this, 12.25% is from this region. The trade liberalization has reduced the cost of importing food products from ASEAN member countries, and consumers are getting more varieties of products. The bottom-line is trade liberalization within the ASEAN region complements Malaysian government’s effort to be a food-secured nation.

Keywords: Trade liberalization, ASEAN, import, export, food security

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia is part of the countries that join and support trade liberalization initiatives, including the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA). The establishment of AFTA is a form of regional cooperation to create balanced and fair free trade and increase economic competitiveness among ASEAN countries. A free trade area allows member countries to enjoy a larger market with broader resources. In theory, additional business will be created among member countries due to having market access and free trade privileges through signed trade agreements. Competitive advantage is expected to occur in the regional economy, leading to increase in trade, income, and better living standards. After more than 20 years of its establishment, AFTA has impacted Malaysia's agricultural production and trade patterns. The production, export, and import trends of selected agricultural products have changed and impacted the supply chain of these products in Malaysia.

The establishment of ASEAN and the implementation of AFTA have contributed to trade in agricultural products among ASEAN member countries. Tariff reduction significantly impacts trade by reducing the cost of exporting products. However, free trade can affect the production of agricultural products in less competitive countries. Tariff reduction allows low-cost producing countries to export their products to other countries and compete with local products. It also enables users to choose whether to buy local products or products from foreign countries.

In terms of intra-ASEAN trade, Malaysia faces competition from products of other countries that are relatively cheaper. Although intra-ASEAN trade from Malaysia shows an increase, the quantum of growth is still small.

This article discusses the implementation of free trade between ASEAN member countries and its impact on food security in Malaysia. It highlights some challenges, impacts and the government aspiration to be a food secured nation.

ASEAN AND TRADE LIBERALIZATION

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) comprises of ten Southeast Asian member states. The members of the ASEAN are Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia. The ASEAN was formed to improve member nations' economic, political, and social cooperation. ASEAN member countries have adopted the following fundamental principles in their relations with one another, as contained in the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC):

- Mutual respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity, and national identity of all nations;

- The right of every State to lead its national existence free from external interference, subversion, or coercion;

- Non-interference in the internal affairs of one another;

- Settlement of differences or disputes in a peaceful manner;

- Renunciation of the threat or use of force; and

- Effective cooperation among themselves.

Today, ASEAN has a combined GDP of US$3.1 trillion, making it the 7th largest economy, growing steadily. It is home to a population of 650 million people, making it the third-largest labor force in the world, behind China and India. ASEAN represents the cooperation of people with different cultures, lifestyles, economic development, and religions. However, the member state in this region has the same aspiration: to progress together in all aspects of the socio economy.

The ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, or AFTA, is an initiative and trade agreement between all member states to build on and further develop the ASEAN economy. The AFTA aims to improve the economic outlook by implementing regulatory best practices, smooth trade, and increasing chances of foreign investments through agreements that would facilitate lower tariffs and ease of business. The AFTA benefits both consumers and producers in the ASEAN region. A lower trade tariff would mean consumers have more spending power and can enjoy a more significant market offering as the market becomes more competitive. The ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) eliminates more than 99.65% of import tariff for intra-ASEAN trade. Moreover, reducing barriers to intra-regional business gives ASEAN consumers a wider choice of better-quality consumer products.

In the agricultural sector, the agreements that require liberalization are the Agreement of Agriculture (AoA) under the WTO and the Protocol on the Special Arrangement for Sensitive and Highly Sensitive Products under the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT-AFTA) Scheme. The CEPT scheme under AFTA is the primary mechanism used by ASEAN to realize free trade aspirations. This means that ASEAN member countries that participate in AFTA have tariff uniformity. AFTA, through the CEPT scheme, is also a step taken to prepare the region to face global liberalization challenges. It also aims to eliminate tariffs on intra-ASEAN trade through progressive tariff reduction. In its early creation stages, unprocessed agricultural products were not included in the CEPT scheme. It was only included in 1996.

On 26 February 2009, the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) was signed by the ASEAN Heads of State in Thailand and entered into force on 17 May 2010. ATIGA replaces the CEPT Scheme and provides a more comprehensive legal framework to realize free trade in the region. The ATIGA Agreement abolishes non-tariff barriers and emphasizes procedures, documentation, and sanitary and phytosanitary requirements.

TRADING BETWEEN MALAYSIA AND ASEAN COUNTRIES

International trade is important to economic development because Malaysia is a trading country. Malaysia places high and significant importance on a strong, open, and viable international trading system. In 2022, Malaysia was ranked the world’s top 25th trading and exporting nation, and 26th importing nation, by the World Trade Organization (WTO). AFTA provides a platform to strengthen the trading system among regional countries. Malaysia's biggest export market is ASEAN. In 2021, exports from Malaysia to ASEAN countries amounted to around RM343.00 (US$76.22) billion. Singapore was the leading export market for Malaysia in ASEAN, with an export value of US$38.50 (RM173.40) billion in that year. Thailand was the second highest exporting partner, with US$11.64 (RM52.40) billion, followed by Vietnam (US$11.40 billion) and Indonesia (US$8.70 billion).

Malaysia generally conducts trade with all countries in ASEAN and produces a positive trade balance. The main products imported from Singapore are animal feeds, grain preparations, and beverages. Rice and sugar are the main commodities imported from Thailand. Coffee and tea are among the items imported from Indonesia. Meanwhile, grains, including rice and grain preparations, are imported from Vietnam. Singapore continues to be Malaysia's agricultural products export partner, followed by Thailand and Indonesia. The agricultural products exported to Singapore include cereals, vegetables and vegetable planting materials, livestock, life broilers, meat, edible meat, oil palm, fruits, nuts, coffee, tea, and spices. Vietnam and the Philippines also hold a relatively large percentage of export destinations for agricultural products from Malaysia. This shows Malaysia's export market among AFTA countries is good, without relying entirely on countries outside ASEAN. Malaysia also exports agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, medicines for veterinary needs, and fungicides to Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

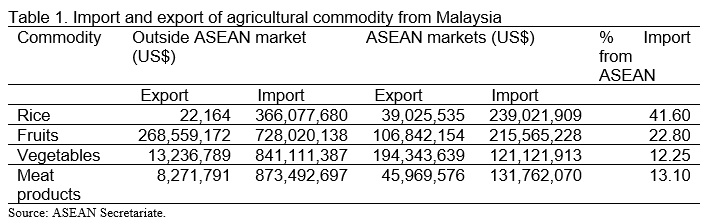

Malaysian dependents on agricultural products from ASEAN regions are between 13.1% and 41.6%. Malaysia purchases around 740,000 tons, or approximately 41.6% of rice, from ASEAN member countries, while the balance is outsourced from other countries, such as India, Pakistan, Japan, and others. The exports and imports of selected agricultural commodities from Malaysia are presented in Table 1.

THE IMPACT OF TRADE LIBERALIZATION TO MALAYSIA’S FOOD SECURITY

Food security refers to the availability of food supplies and the ability to obtain them. In general, each country has a different definition related to food security. At the international level, food security means the responsibility of all nations to ensure stable food markets and prices. At the national level, food security means ensuring a regular food supply in the domestic market. At the individual level, it means the sufficiency of the food supply that meets the needs of oneself and the family.

Food security is when everyone, always, has physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life. Food security also refers to nutritious, safe, and halal food. Food security can be seen in availability, accessibility, consumption, and stability. The Global Food Security Index (GFSI) is the benchmark model that measures food security worldwide in terms of four dimensions: Food availability, affordability, Quality and safety, and natural resources and resilience. What is the status of food security in Malaysia? According to the Global Food Security Index (GFSI), a country can be considered a Food Secured Nation when it can fulfill the four criteria as follows:

- Affordability: The ability of consumers to purchase food, their vulnerability to price shocks, and the presence of programs and policies to support consumers when shocks occur;

- Availability: The ability of agricultural production to supply local needs and the national capacity to distribute food to the people and the R&D programs that could expand agriculture output;

- Quality and safety: To ensure the variety of food supply are nutritional for an average diet, as well as safe for consumption; and

- Sustainability and adaptation: The capability of the country to manage the impact of climate change, its susceptibility to natural resource risks, and how it adapts to these risks.

Physical availability means that food must be readily available, while physical accessibility means that not only must food be available, but it must also be accessible. Food utilization describes how food is used (either efficiently or inefficiently), and stability means a consistent supply of food. At the same time, food perishability is also a significant factor in stability.

The source of food supply in Malaysia comes from local production and import from other countries, especially the ASEAN region. The intra-ASEAN trading helps Malaysia to outsource its food supply at affordable prices. This is because the cost of importing the commodity has reduced due to the no-tax regime and the short distance from those countries to Malaysia. The commodities from Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Vietnam are supplied by land transportation, while products from Indonesia are transported by ships.

Agriculture production

The agricultural sector in Malaysia is divided into two categories: industrial agriculture, which includes palm oil, rubber, and cocoa crops. In contrast, food agriculture includes rice crops, fruits and vegetables, livestock, and fisheries. Policies and programs for developing the agricultural sector in Malaysia aim to increase farmers' income to reduce the poverty rate and increase the national income through exporting agricultural products to the international market. Policies related to industrial agriculture are export-oriented, while food agriculture is to ensure food security. The government encourages the development of industrial agriculture for export while protecting food agriculture to protect the domestic industry and save foreign exchange.

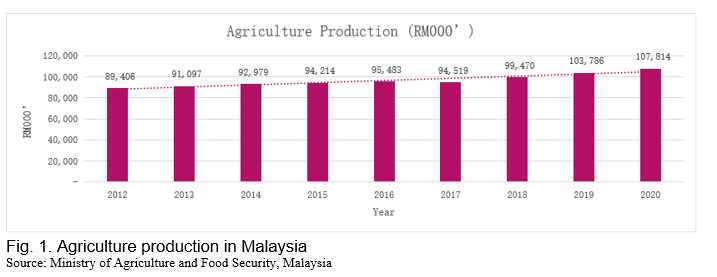

The agricultural sector is the third largest economy in the country, after the service and manufacturing sectors. In 2021, this sector contributed more than RM107.00 (US$23.77) billion or 7.5% to GDP, provided employment to more than 1.5 million people, and was the country's main food supplier. The contribution of the agriculture sector is presented in Figure 1.

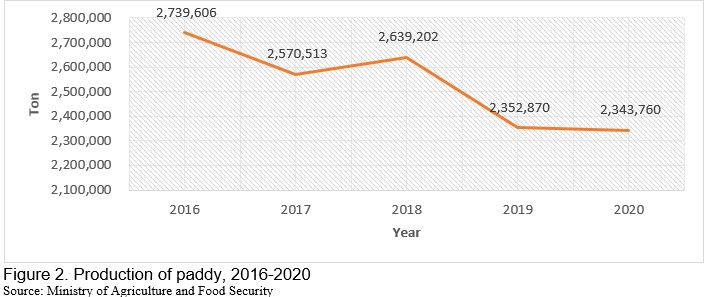

Agriculture production increased from RM89.40 (US$19.87) billion in 2012 to more than RM107.81 (US$23.96) billion in 2020. However, the output of agri-food commodities in Malaysia is dropping yearly. Paddy production declined from 2.74 million tons in 2016 to 2.34 million tons in 2020. Malaysia is only able to supply around 70% for local consumption. As a result, Malaysia imports more than 1.8 million tons of rice from Vietnam, Thailand, India, Pakistan, and other countries. The production of rice in Malaysia is presented in Figure 2. Since Malaysia is a net rice importer, almost all rice is used there.

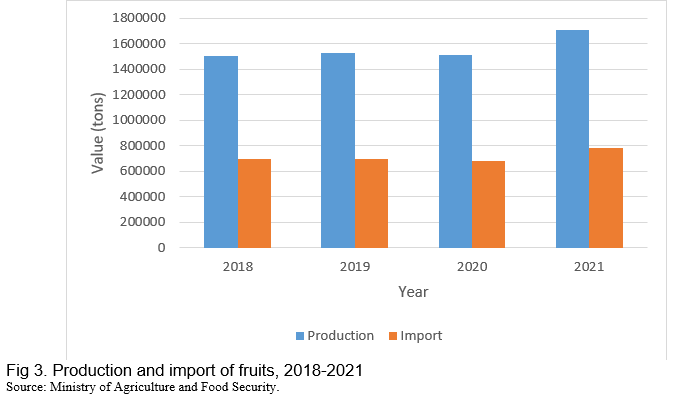

Malaysia is one of the global producers of tropical fruits. Every year Malaysia produces more than 1.5 million tons of fruits, and exports these to several countries, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and China. Malaysia produced more than 1.509 million tons of fruits, valued at more than RM10.02 (US$2.26) billion in 2020. In the same year, Malaysia exported tropical fruits valued more than RM1.40 (US$0.31) billion. The export of fruits is increasing every year.

Despite exporting its fruits to global markets, Malaysia also imports fruits from other countries, especially temperate fruits such as apples, mandarin orange, pear, and others. Malaysia also imports tropical fruits from ASEAN countries, such as mango from Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia, durian and rambutan from Thailand, and avocado from Indonesia. The different fruiting seasons between Malaysia and other countries are the main factor that enables the trading of tropical fruits from the ASEAN member countries. The production and import of fruits from Malaysia are presented in Figure 3.

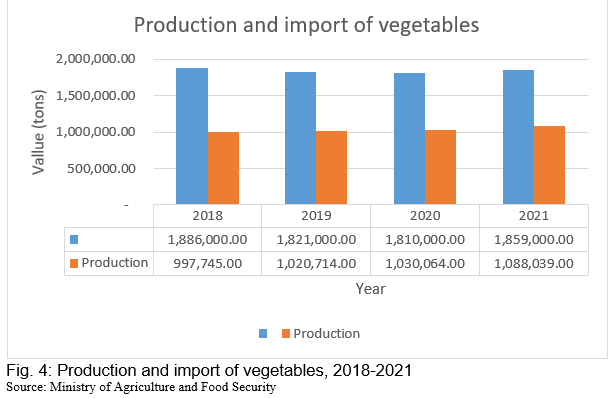

Malaysia produces more than 1.0 million tons of vegetables valued at more than RM2.40 (US$0.53) billion. The production of vegetables has increased from 0.998 million tons in 2018 to more than 1.08 million tons in 2021. More than local production is required for local consumers, especially temperate vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, and celery. The land area for producing temperate vegetables is limited, thus Malaysia cannot expand the production area. The self-sufficiency level for vegetables is only 51.5%. As a result, Malaysia imports more than 1.80 million tons of vegetables valued at more than RM5.11 (US$1.13) billion from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and other countries. The production and import of vegetables are presented in Figure 4.

Despite insufficient production for local consumption, Malaysia also exports its vegetables to its traditional market, Singapore and other countries. In 2020, Malaysia exported vegetables valued at more than RM1.014 (US$0.225) billion to global markets.

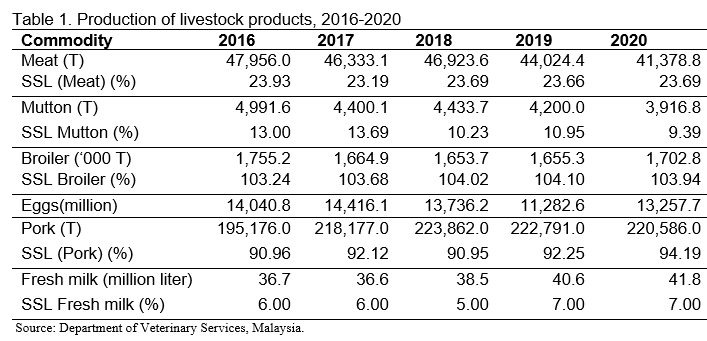

The production of livestock commodities also showed declining trends since 2016. The number of cattle, for example, has reduced from 737,727 heads in 2016 to 659,317 in 2020. The number of buffaloes has declined from more than 119,133 to 100,242 heads in the same period. As a result, beef production has dropped from 47,956 tons in 2016 to 41,378.8 tons in 2020, and mutton from 4,991.6 tons to 3,916.8 tons. Only broilers and pork have shown an increased production within the same period. Malaysia imports many meat products from Australia, New Zealand, and India and live cattle from Thailand. Malaysia imported more than 159,186 tons of beef valued at more than RM2.01 (US$0.46) billion in 2020.

Despite the low local production of food products, Malaysia is generally a food-secured nation. In 2022, Malaysia was ranked 41st, out of 120 countries in the world, showing a moderate performance with a score of 69.9 compared to the previous year. Malaysia's overall score also experienced a decrease of 1.6 compared to 2021. Positioned according to the affordability category, Malaysia obtained a score of 87 in the 30th position, while for the availability category, it obtained a score of 59.5 in the 56th position. Overall, the food security score is moderate. All major foods are available sufficiently to meet the demand.

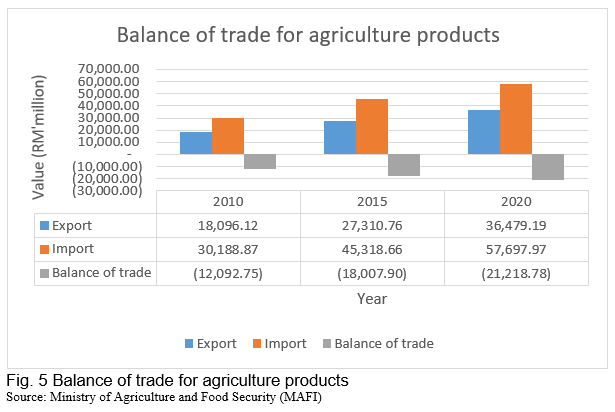

Malaysia imports a lot of its food supply from other countries to complement the short supply from local production. The import of food products increased from RM30.20 (US$7.19) billion in 2015 to RM57.70 (US$12.82) billion in 2020, increasing the negative trade balance of RM21.20 (US$2.71) billion.

In nearly 70 years since independence, Malaysia's economy has changed from an agriculture-based economy to an industrial-driven economy. Participation in international trade also follows this change. Most of the country's agricultural production results from industrial crops such as palm oil, rubber, and cocoa. Much focus is given to increasing the production of industrial crops compared to the food crops, such as rice, fruits, and vegetables. A negative production growth rate was recorded to produce rice, fruits, vegetables, cattle, and poultry, all the country's main food commodities. Therefore, the country's food supply adequacy status has not been guaranteed. From the establishment of AFTA until now, ASEAN has consistently been Malaysia's source of food.

Malaysia generally benefits from AFTA in terms of intra-ASEAN trade, which is seen to continue to increase year by year. In addition to creating free trade areas in regional areas, AFTA also opens trade routes with other countries that previously had no trade relations with Malaysia, further expanding regional markets and investment activities. One of the main challenges facing Malaysia in international trade is managing agricultural commodity production in a state of declining competitiveness. Malaysia must compete with countries with low production costs and produce better quality products. At the same time, Malaysia needs to protect the welfare of farmers and local industries from being collapse if products from foreign countries continue to flood the local market.

AFTA has the potential to produce a lot of benefits, but at the same time creates many challenges for Malaysia. It aimed to benefit Malaysian consumers and local companies by introducing a low rate of tax imposed on the raw material of the products to encourage the free flow of products and make them cheaper. Still, due to the enforcement of taxes on consumers, product prices are indirectly increasing. Prices are supposed to be decreased as predicted, but consumer products are still expensive. There is also an increase in intra-ASEAN competition from lower-cost producers. Free flows of human resources also harm the labor of wealthy countries like Malaysia.

Import of agro-food to complement local production

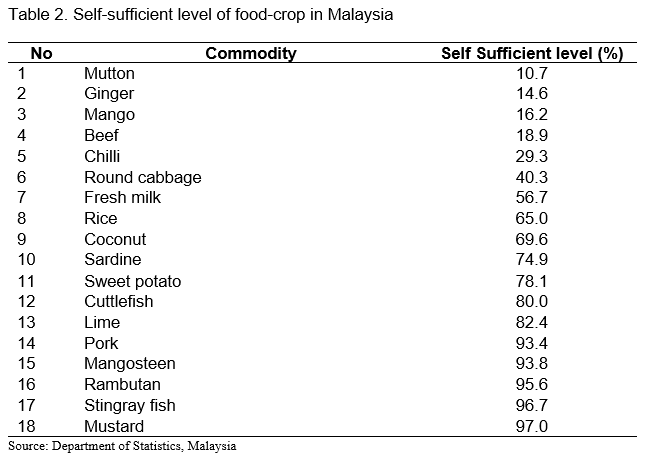

In general, the local production of most agro-food products is insufficient for local consumption. Malaysia depends heavily on other countries to supply its food. For example, Malaysia can only produce around 65% of its rice and needs to import more than 35%, amounting to more than 1.8 million tons every year. The country can only produce 18.9% of beef and must import more than 170,000 tons of meat. Malaysia also needs to import fruits, vegetables, and fisheries products, and the ASEAN region is one of the best sources of supply. The self-sufficient level for selected commodities that indicate the availability of agri-food in Malaysia is presented in Table 2.

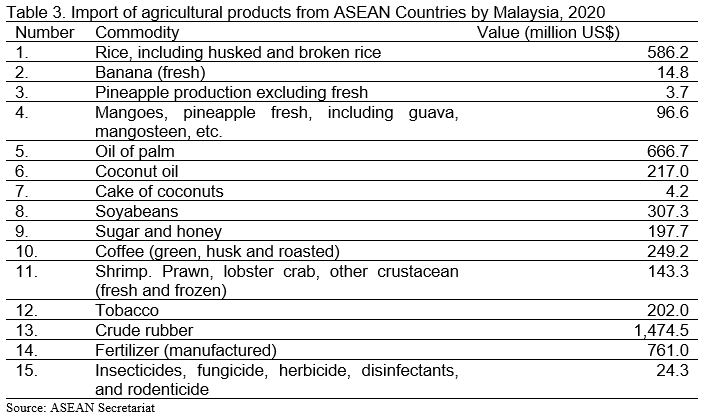

Malaysia imports many agricultural products from the ASEAN region to complement the short supply of local production. The agricultural products imported from the ASEAN member countries are presented in Table 3.

Rice is the most imported agricultural product from ASEAN member countries. For example, in 2021, Malaysia imported rice from Vietnam valued at more than US$133.10 million, Thailand (US$66.79), Myanmar (US$7.72 million), Indonesia (US$0.26 million), and Cambodia (US$31.09 million). Malaysia also imported agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and chemicals from ASEAN member countries for agrifood production. Some agricultural products are imported as raw materials before reprocessing or manufacturing and then exported to global markets. These products include crude rubber and oil palm.

WAY FORWARD

Food security is the main agenda of all governments, including Malaysia. The Malaysian government has carried out various strategies to ensure that food security is the main agenda to safeguard the welfare of the people and ensure the country's resilience in the face of different global challenges. The food security programs aim to ensure that food is always available for the people and that people can afford to buy the food. The food security program has been the core aspiration in Malaysia's National Agrifood Policy, 2021-2030.

The Food Security Policy Action Plan 2021-2025 has been developed to strengthen the country's food security by considering issues and challenges along the food supply chain, from agricultural inputs to food waste. The National Food Security Policy Action Plan (DSMN Action Plan) 2021-2025, is expected to be able to always ensure the continuity of the country’s food supply, especially in the face of unexpected situations. The four objectives of the food security policy action plan are as follows:

- Increasing internal resources and diversifying import sources;

- Increase the involvement of the private sector and the population in the food system;

- Ensuring the availability of safe food at reasonable prices and a healthy eating style; and

- Ensuring the country's preparedness in a food security crisis.

The Food Security Action Plan 2021-205 is implemented based on five cores, 15 strategies, and 96 initiatives. To ensure sufficient food supply, one of the action plans is to ensure import capacity availability and facilitate procedures to explore alternative food import sources. Many challenges are still faced, and a more comprehensive strategy is needed to ensure that the food supply in Malaysia is always guaranteed.

REFERENCES

ASEAN Secreteriate, 2022. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook. 2022. Available at International Merchandise Trade Statistics (IMTS) - Annually ASEANStatsDataPortal

Ministry of Agriculture and Food Secuity, 2020. Dasar Agro-Makanan Negara, 2021-2030 (National Agro-food Policy, 2021-2030) MAFI, Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE). Trade Statistics Available at -ttps://www.matrade.gov.my/en/choose-malaysia/industry-capabilities/trade-statis...

MARDI, 2015. Kajian Perjanjian Kawasan Perdagangan Bebas ASEAN (AFTA), dan kesannya kepada pengeluaran, perdagangan dan pelaburan sektor pertanian di Malaysia. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi, 2015. Pusat Penyelidikan Ekonomi, dan Sains Sosial, MARDI.

Trade Liberalization in ASEAN and its Impacts on Malaysia’s Food Security

ABSTRACT

Malaysia has always been a trading nation. Strategically located along the Straits of Malacca, it sits on a major shipping channel that connects the Indian Ocean to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east. Malaysia recognizes the importance of international trade and relations to the nation’s growth and development. Given Malaysia’s reliance on international trade, Malaysia has adopted liberal trade policies and highly emphasizes regional and bilateral trade agreements. According to the World Trade Organization, Malaysia is the world’s top 25th trading and exporting nation and 26th importing nation. Trade liberalization with the ASEAN regions helps Malaysia outsource its food supply, as the local production is insufficient to meet the local demand. In 2022, Malaysia imported more than 1.8 million tons or around 35% of its rice for its people. Malaysia also imported more than 680,000 tons of fruits, of which 22.8% comes from ASEAN countries. In the same year, Malaysia imported more than 1.8 million tons of vegetables, and out of this, 12.25% is from this region. The trade liberalization has reduced the cost of importing food products from ASEAN member countries, and consumers are getting more varieties of products. The bottom-line is trade liberalization within the ASEAN region complements Malaysian government’s effort to be a food-secured nation.

Keywords: Trade liberalization, ASEAN, import, export, food security

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia is part of the countries that join and support trade liberalization initiatives, including the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA). The establishment of AFTA is a form of regional cooperation to create balanced and fair free trade and increase economic competitiveness among ASEAN countries. A free trade area allows member countries to enjoy a larger market with broader resources. In theory, additional business will be created among member countries due to having market access and free trade privileges through signed trade agreements. Competitive advantage is expected to occur in the regional economy, leading to increase in trade, income, and better living standards. After more than 20 years of its establishment, AFTA has impacted Malaysia's agricultural production and trade patterns. The production, export, and import trends of selected agricultural products have changed and impacted the supply chain of these products in Malaysia.

The establishment of ASEAN and the implementation of AFTA have contributed to trade in agricultural products among ASEAN member countries. Tariff reduction significantly impacts trade by reducing the cost of exporting products. However, free trade can affect the production of agricultural products in less competitive countries. Tariff reduction allows low-cost producing countries to export their products to other countries and compete with local products. It also enables users to choose whether to buy local products or products from foreign countries.

In terms of intra-ASEAN trade, Malaysia faces competition from products of other countries that are relatively cheaper. Although intra-ASEAN trade from Malaysia shows an increase, the quantum of growth is still small.

This article discusses the implementation of free trade between ASEAN member countries and its impact on food security in Malaysia. It highlights some challenges, impacts and the government aspiration to be a food secured nation.

ASEAN AND TRADE LIBERALIZATION

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) comprises of ten Southeast Asian member states. The members of the ASEAN are Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia. The ASEAN was formed to improve member nations' economic, political, and social cooperation. ASEAN member countries have adopted the following fundamental principles in their relations with one another, as contained in the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC):

Today, ASEAN has a combined GDP of US$3.1 trillion, making it the 7th largest economy, growing steadily. It is home to a population of 650 million people, making it the third-largest labor force in the world, behind China and India. ASEAN represents the cooperation of people with different cultures, lifestyles, economic development, and religions. However, the member state in this region has the same aspiration: to progress together in all aspects of the socio economy.

The ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, or AFTA, is an initiative and trade agreement between all member states to build on and further develop the ASEAN economy. The AFTA aims to improve the economic outlook by implementing regulatory best practices, smooth trade, and increasing chances of foreign investments through agreements that would facilitate lower tariffs and ease of business. The AFTA benefits both consumers and producers in the ASEAN region. A lower trade tariff would mean consumers have more spending power and can enjoy a more significant market offering as the market becomes more competitive. The ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) eliminates more than 99.65% of import tariff for intra-ASEAN trade. Moreover, reducing barriers to intra-regional business gives ASEAN consumers a wider choice of better-quality consumer products.

In the agricultural sector, the agreements that require liberalization are the Agreement of Agriculture (AoA) under the WTO and the Protocol on the Special Arrangement for Sensitive and Highly Sensitive Products under the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT-AFTA) Scheme. The CEPT scheme under AFTA is the primary mechanism used by ASEAN to realize free trade aspirations. This means that ASEAN member countries that participate in AFTA have tariff uniformity. AFTA, through the CEPT scheme, is also a step taken to prepare the region to face global liberalization challenges. It also aims to eliminate tariffs on intra-ASEAN trade through progressive tariff reduction. In its early creation stages, unprocessed agricultural products were not included in the CEPT scheme. It was only included in 1996.

On 26 February 2009, the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) was signed by the ASEAN Heads of State in Thailand and entered into force on 17 May 2010. ATIGA replaces the CEPT Scheme and provides a more comprehensive legal framework to realize free trade in the region. The ATIGA Agreement abolishes non-tariff barriers and emphasizes procedures, documentation, and sanitary and phytosanitary requirements.

TRADING BETWEEN MALAYSIA AND ASEAN COUNTRIES

International trade is important to economic development because Malaysia is a trading country. Malaysia places high and significant importance on a strong, open, and viable international trading system. In 2022, Malaysia was ranked the world’s top 25th trading and exporting nation, and 26th importing nation, by the World Trade Organization (WTO). AFTA provides a platform to strengthen the trading system among regional countries. Malaysia's biggest export market is ASEAN. In 2021, exports from Malaysia to ASEAN countries amounted to around RM343.00 (US$76.22) billion. Singapore was the leading export market for Malaysia in ASEAN, with an export value of US$38.50 (RM173.40) billion in that year. Thailand was the second highest exporting partner, with US$11.64 (RM52.40) billion, followed by Vietnam (US$11.40 billion) and Indonesia (US$8.70 billion).

Malaysia generally conducts trade with all countries in ASEAN and produces a positive trade balance. The main products imported from Singapore are animal feeds, grain preparations, and beverages. Rice and sugar are the main commodities imported from Thailand. Coffee and tea are among the items imported from Indonesia. Meanwhile, grains, including rice and grain preparations, are imported from Vietnam. Singapore continues to be Malaysia's agricultural products export partner, followed by Thailand and Indonesia. The agricultural products exported to Singapore include cereals, vegetables and vegetable planting materials, livestock, life broilers, meat, edible meat, oil palm, fruits, nuts, coffee, tea, and spices. Vietnam and the Philippines also hold a relatively large percentage of export destinations for agricultural products from Malaysia. This shows Malaysia's export market among AFTA countries is good, without relying entirely on countries outside ASEAN. Malaysia also exports agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, medicines for veterinary needs, and fungicides to Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

Malaysian dependents on agricultural products from ASEAN regions are between 13.1% and 41.6%. Malaysia purchases around 740,000 tons, or approximately 41.6% of rice, from ASEAN member countries, while the balance is outsourced from other countries, such as India, Pakistan, Japan, and others. The exports and imports of selected agricultural commodities from Malaysia are presented in Table 1.

THE IMPACT OF TRADE LIBERALIZATION TO MALAYSIA’S FOOD SECURITY

Food security refers to the availability of food supplies and the ability to obtain them. In general, each country has a different definition related to food security. At the international level, food security means the responsibility of all nations to ensure stable food markets and prices. At the national level, food security means ensuring a regular food supply in the domestic market. At the individual level, it means the sufficiency of the food supply that meets the needs of oneself and the family.

Food security is when everyone, always, has physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life. Food security also refers to nutritious, safe, and halal food. Food security can be seen in availability, accessibility, consumption, and stability. The Global Food Security Index (GFSI) is the benchmark model that measures food security worldwide in terms of four dimensions: Food availability, affordability, Quality and safety, and natural resources and resilience. What is the status of food security in Malaysia? According to the Global Food Security Index (GFSI), a country can be considered a Food Secured Nation when it can fulfill the four criteria as follows:

Physical availability means that food must be readily available, while physical accessibility means that not only must food be available, but it must also be accessible. Food utilization describes how food is used (either efficiently or inefficiently), and stability means a consistent supply of food. At the same time, food perishability is also a significant factor in stability.

The source of food supply in Malaysia comes from local production and import from other countries, especially the ASEAN region. The intra-ASEAN trading helps Malaysia to outsource its food supply at affordable prices. This is because the cost of importing the commodity has reduced due to the no-tax regime and the short distance from those countries to Malaysia. The commodities from Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Vietnam are supplied by land transportation, while products from Indonesia are transported by ships.

Agriculture production

The agricultural sector in Malaysia is divided into two categories: industrial agriculture, which includes palm oil, rubber, and cocoa crops. In contrast, food agriculture includes rice crops, fruits and vegetables, livestock, and fisheries. Policies and programs for developing the agricultural sector in Malaysia aim to increase farmers' income to reduce the poverty rate and increase the national income through exporting agricultural products to the international market. Policies related to industrial agriculture are export-oriented, while food agriculture is to ensure food security. The government encourages the development of industrial agriculture for export while protecting food agriculture to protect the domestic industry and save foreign exchange.

The agricultural sector is the third largest economy in the country, after the service and manufacturing sectors. In 2021, this sector contributed more than RM107.00 (US$23.77) billion or 7.5% to GDP, provided employment to more than 1.5 million people, and was the country's main food supplier. The contribution of the agriculture sector is presented in Figure 1.

Agriculture production increased from RM89.40 (US$19.87) billion in 2012 to more than RM107.81 (US$23.96) billion in 2020. However, the output of agri-food commodities in Malaysia is dropping yearly. Paddy production declined from 2.74 million tons in 2016 to 2.34 million tons in 2020. Malaysia is only able to supply around 70% for local consumption. As a result, Malaysia imports more than 1.8 million tons of rice from Vietnam, Thailand, India, Pakistan, and other countries. The production of rice in Malaysia is presented in Figure 2. Since Malaysia is a net rice importer, almost all rice is used there.

Malaysia is one of the global producers of tropical fruits. Every year Malaysia produces more than 1.5 million tons of fruits, and exports these to several countries, such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and China. Malaysia produced more than 1.509 million tons of fruits, valued at more than RM10.02 (US$2.26) billion in 2020. In the same year, Malaysia exported tropical fruits valued more than RM1.40 (US$0.31) billion. The export of fruits is increasing every year.

Despite exporting its fruits to global markets, Malaysia also imports fruits from other countries, especially temperate fruits such as apples, mandarin orange, pear, and others. Malaysia also imports tropical fruits from ASEAN countries, such as mango from Thailand, Myanmar, and Cambodia, durian and rambutan from Thailand, and avocado from Indonesia. The different fruiting seasons between Malaysia and other countries are the main factor that enables the trading of tropical fruits from the ASEAN member countries. The production and import of fruits from Malaysia are presented in Figure 3.

Malaysia produces more than 1.0 million tons of vegetables valued at more than RM2.40 (US$0.53) billion. The production of vegetables has increased from 0.998 million tons in 2018 to more than 1.08 million tons in 2021. More than local production is required for local consumers, especially temperate vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, and celery. The land area for producing temperate vegetables is limited, thus Malaysia cannot expand the production area. The self-sufficiency level for vegetables is only 51.5%. As a result, Malaysia imports more than 1.80 million tons of vegetables valued at more than RM5.11 (US$1.13) billion from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and other countries. The production and import of vegetables are presented in Figure 4.

Despite insufficient production for local consumption, Malaysia also exports its vegetables to its traditional market, Singapore and other countries. In 2020, Malaysia exported vegetables valued at more than RM1.014 (US$0.225) billion to global markets.

The production of livestock commodities also showed declining trends since 2016. The number of cattle, for example, has reduced from 737,727 heads in 2016 to 659,317 in 2020. The number of buffaloes has declined from more than 119,133 to 100,242 heads in the same period. As a result, beef production has dropped from 47,956 tons in 2016 to 41,378.8 tons in 2020, and mutton from 4,991.6 tons to 3,916.8 tons. Only broilers and pork have shown an increased production within the same period. Malaysia imports many meat products from Australia, New Zealand, and India and live cattle from Thailand. Malaysia imported more than 159,186 tons of beef valued at more than RM2.01 (US$0.46) billion in 2020.

Despite the low local production of food products, Malaysia is generally a food-secured nation. In 2022, Malaysia was ranked 41st, out of 120 countries in the world, showing a moderate performance with a score of 69.9 compared to the previous year. Malaysia's overall score also experienced a decrease of 1.6 compared to 2021. Positioned according to the affordability category, Malaysia obtained a score of 87 in the 30th position, while for the availability category, it obtained a score of 59.5 in the 56th position. Overall, the food security score is moderate. All major foods are available sufficiently to meet the demand.

Malaysia imports a lot of its food supply from other countries to complement the short supply from local production. The import of food products increased from RM30.20 (US$7.19) billion in 2015 to RM57.70 (US$12.82) billion in 2020, increasing the negative trade balance of RM21.20 (US$2.71) billion.

In nearly 70 years since independence, Malaysia's economy has changed from an agriculture-based economy to an industrial-driven economy. Participation in international trade also follows this change. Most of the country's agricultural production results from industrial crops such as palm oil, rubber, and cocoa. Much focus is given to increasing the production of industrial crops compared to the food crops, such as rice, fruits, and vegetables. A negative production growth rate was recorded to produce rice, fruits, vegetables, cattle, and poultry, all the country's main food commodities. Therefore, the country's food supply adequacy status has not been guaranteed. From the establishment of AFTA until now, ASEAN has consistently been Malaysia's source of food.

Malaysia generally benefits from AFTA in terms of intra-ASEAN trade, which is seen to continue to increase year by year. In addition to creating free trade areas in regional areas, AFTA also opens trade routes with other countries that previously had no trade relations with Malaysia, further expanding regional markets and investment activities. One of the main challenges facing Malaysia in international trade is managing agricultural commodity production in a state of declining competitiveness. Malaysia must compete with countries with low production costs and produce better quality products. At the same time, Malaysia needs to protect the welfare of farmers and local industries from being collapse if products from foreign countries continue to flood the local market.

AFTA has the potential to produce a lot of benefits, but at the same time creates many challenges for Malaysia. It aimed to benefit Malaysian consumers and local companies by introducing a low rate of tax imposed on the raw material of the products to encourage the free flow of products and make them cheaper. Still, due to the enforcement of taxes on consumers, product prices are indirectly increasing. Prices are supposed to be decreased as predicted, but consumer products are still expensive. There is also an increase in intra-ASEAN competition from lower-cost producers. Free flows of human resources also harm the labor of wealthy countries like Malaysia.

Import of agro-food to complement local production

In general, the local production of most agro-food products is insufficient for local consumption. Malaysia depends heavily on other countries to supply its food. For example, Malaysia can only produce around 65% of its rice and needs to import more than 35%, amounting to more than 1.8 million tons every year. The country can only produce 18.9% of beef and must import more than 170,000 tons of meat. Malaysia also needs to import fruits, vegetables, and fisheries products, and the ASEAN region is one of the best sources of supply. The self-sufficient level for selected commodities that indicate the availability of agri-food in Malaysia is presented in Table 2.

Malaysia imports many agricultural products from the ASEAN region to complement the short supply of local production. The agricultural products imported from the ASEAN member countries are presented in Table 3.

Rice is the most imported agricultural product from ASEAN member countries. For example, in 2021, Malaysia imported rice from Vietnam valued at more than US$133.10 million, Thailand (US$66.79), Myanmar (US$7.72 million), Indonesia (US$0.26 million), and Cambodia (US$31.09 million). Malaysia also imported agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and chemicals from ASEAN member countries for agrifood production. Some agricultural products are imported as raw materials before reprocessing or manufacturing and then exported to global markets. These products include crude rubber and oil palm.

WAY FORWARD

Food security is the main agenda of all governments, including Malaysia. The Malaysian government has carried out various strategies to ensure that food security is the main agenda to safeguard the welfare of the people and ensure the country's resilience in the face of different global challenges. The food security programs aim to ensure that food is always available for the people and that people can afford to buy the food. The food security program has been the core aspiration in Malaysia's National Agrifood Policy, 2021-2030.

The Food Security Policy Action Plan 2021-2025 has been developed to strengthen the country's food security by considering issues and challenges along the food supply chain, from agricultural inputs to food waste. The National Food Security Policy Action Plan (DSMN Action Plan) 2021-2025, is expected to be able to always ensure the continuity of the country’s food supply, especially in the face of unexpected situations. The four objectives of the food security policy action plan are as follows:

The Food Security Action Plan 2021-205 is implemented based on five cores, 15 strategies, and 96 initiatives. To ensure sufficient food supply, one of the action plans is to ensure import capacity availability and facilitate procedures to explore alternative food import sources. Many challenges are still faced, and a more comprehensive strategy is needed to ensure that the food supply in Malaysia is always guaranteed.

REFERENCES

ASEAN Secreteriate, 2022. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook. 2022. Available at International Merchandise Trade Statistics (IMTS) - Annually ASEANStatsDataPortal

Ministry of Agriculture and Food Secuity, 2020. Dasar Agro-Makanan Negara, 2021-2030 (National Agro-food Policy, 2021-2030) MAFI, Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE). Trade Statistics Available at -ttps://www.matrade.gov.my/en/choose-malaysia/industry-capabilities/trade-statis...

MARDI, 2015. Kajian Perjanjian Kawasan Perdagangan Bebas ASEAN (AFTA), dan kesannya kepada pengeluaran, perdagangan dan pelaburan sektor pertanian di Malaysia. Laporan Kajian Sosioekonomi, 2015. Pusat Penyelidikan Ekonomi, dan Sains Sosial, MARDI.