ABSTRACT

As one of the biodiversity sources, there is a need to develop spice commodities in Indonesia. This article aims to discuss the development of these commodities based on historical value and its future perspective. Spices can be grown in all areas of the country; however, the performance of these crops depends upon technical and non-technical necessities. One of the efforts that can be conducted to increase competitiveness and promote the export of Indonesia's selected priority spice commodities is developing the Geographical Indications (GIs). The development of Indonesia’s spice commodities requires government intervention and the participation of other stakeholders, particularly the private sector, NGOs, development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer communities. It is not only to increase the productivity but also to expand the export in the global market toward enhancing the foreign earning and improving farmers’ income. Apart from government intervention, it is recommended that the investment of both national and international entities are based on natural and human resources toward improving the spice commodities in the country.

Keywords: spice commodities, development, history, perspective, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is listed as one of the 17 global mega diversity countries (Kristina et al., 2017). Located in the equator, which only has two seasons, namely the rainy and dry seasons, Indonesia's crops continuously exist throughout the year. One of them is the spice plants which have historically been an attraction for other nations to come to this country.

Indonesia has experienced a long history that is both proud and heartbreaking related to spices. For centuries Indonesia was the main supplier of spices to the rest of the world. The main commodities were traded along the route connecting Southeast Asia and Europe, which became known as the Maritime Silk Road. Nevertheless, the high value of the spices brought power and wealth to the supplier kingdoms and lured European merchants and their mercenaries to Indonesian shores back in the 16th century. Their arrival started the colonization of the archipelago, especially by the Dutch, for over 350 years (Jakarta Post, 2015 and Sulaiman et al., 2018).

The most well-known spice commodities are nutmeg, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger in the Indonesian context. Nutmeg and clove can be categorized as native commodities of Indonesia, while pepper, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger were adopted from other countries (Sulaiman et al., 2018). Based on the historical value, the development of spices in Indonesia is imperative. The future perspective of these commodities is potential in line with the existing country’s economic growth, particularly in the Asian region. Therefore, this article discusses the development of the country’s spice commodities based-historical value and its future perspective. Initially, it discusses the introduction, followed by the feature of spice commodities, historical value, development perspective, and policy support. Finally, the article addresses some conclusions and recommendations.

SPICE COMMODITIES

Technically, UNIDO and FAO (2005) define that spices are used for flavor, color, aroma, and preservation of food or beverages. Many parts of plant-made spices including barks, buds, flowers, fruits, leaves, rhizomes, roots, seeds, stigmas, and styles or the entire plant tops. The most important spices traditionally traded throughout the world are products of tropical environments.

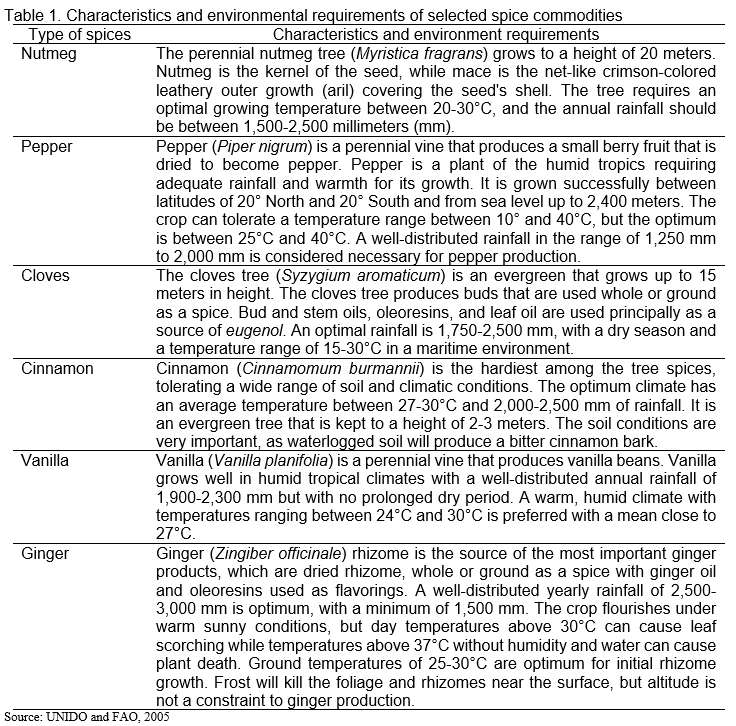

In terms of world trade value, the most important spice crops from the tropical regions are pepper, capsicums, nutmeg/mace, cardamom, pimento, vanilla, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, and turmeric. The characteristics and environmental descriptions of the well-known spice commodities in Indonesia, namely nutmeg, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger, can be seen in Table 1.

The spice-derived products can be classified into three groups, namely: (1) Seasoning or imparting aroma in foods that are fitting for consumption (food grade); (2) Herbs related to medicine or fragrance; and (3) Essential oils produced through a distillation process (UNIDO and FAO, 2005). The ingredients used for spices, herbs, and essential oils can be derived from: (1) Seeds and fruits (e.g. nutmeg, vanilla); (2) Flowers and buds (e.g. cloves, perfume tree); (3) Leaves and stems (e.g. pattern, screw pine); (3) Roots and rhizomes or tubers (e.g. turmeric, ginger); and (4) Leather, wood, and resins or gums (e.g. cinnamon, frankincense). For essential oils, the extent of use is wider than spices and herbs, in which it applied for: (1) Aromatic industry (e.g. culinary, cigarettes); (2) Cosmetic industry (e.g. perfume, soap); (3) Pharmaceutical industry (e.g. antiviral, antimicrobial, antifungal); and (4) Other industries (e.g. paper, cleaners, lubricants, plastics). Hence, spices have multiple functions (Iqbal, 2018), starting from the need for: (1) Food (flavors, preservatives, antioxidants, dyes, instant drinks, and functional foods or foods that can provide more benefits in addition to their basic nutritional functions); (2) Pharmacology (related to drugs); (3) Cosmetics (e.g. shampoo, toothpaste, lotion/moisturizer); (4) Agriculture (e.g. insecticides, pesticides); (5) Chemicals (e.g. varnish, turpentine); to (6) Others (e.g. mixed kretek cigarettes).

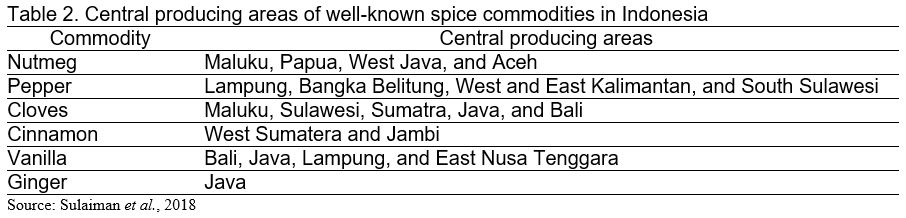

Spices can grow all over areas of Indonesia; however, the good performance of these plants depends upon land suitability, environmental circumstance, and cultivation practices. The country's central producing areas of well-known spice commodities are presented in Table 2 and Appendix Figure 1 to 6.

HISTORICAL VALUE

Semantically, the word "spice" comes from the Latin species, which means an item of special value compared to ordinary articles of trade. The important spices had ritual and medical values and could only grow in the tropical east and be transported to the west, known as Maritime Silk Road (UNESCO, 2021).

Historically, the first people to come to Indonesia to find spice commodities were from Arabia and China, namely during the Sriwijaya Kingdom (around the 7th to 10th century). Then in the subsequent period came the Europeans (Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Dutch), which further made Indonesia a colony (colonialism) for centuries, especially by the Dutch (Iqbal, 2018). The philosophy brought by Europeans to Indonesia at that time was known as Gold (looking for precious spices like gold), Gospel (performing sacred duties), and Glory (getting success).

The success story of spice commodities was in the 1600s to 1800s within a trading partnership or company of the Netherlands, namely “Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC)." Through monopolizing spices in the East Indies, the VOC became the richest multinational giant in history and was listed as the first company to issue shares in the world with an asset value of around 78 million guilders (US$ 7.9 trillion). It is roughly equal to the joint assets of 20 top companies in the modern era, namely Apple, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, ExxonMobil, Google, Microsoft, Tencent, Wells Fargo, and others, or comparable to the combined Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Japan and Germany and greater than the foreign exchange reserves of the current largest country in the world, namely China with a value of around US$ 3.23 trillion (NRC, 2018).

After two centuries of its glories, the role of spices commodities in the mid-1900s tended to decrease along with technological invention, particularly artificial refrigeration. However, spice commodities have become popular due to the alteration of the world’s population lifestyle in line with medical treatments, culinary services, cosmetic requirements, and others.

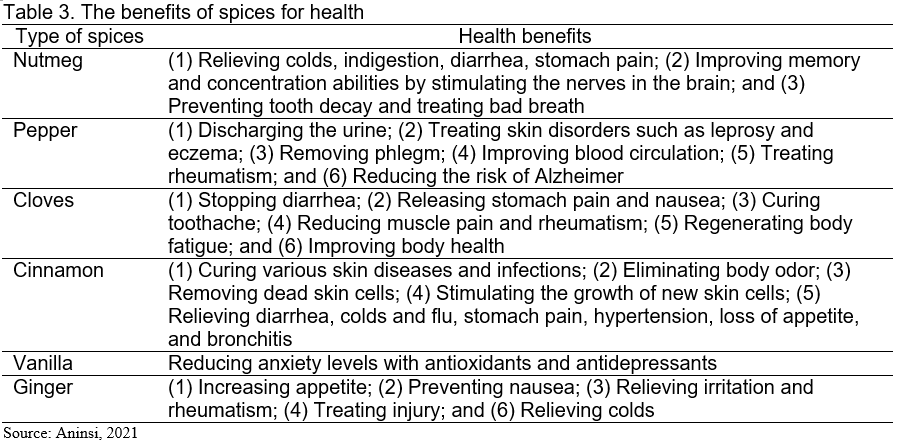

Table 3 summarizes the benefit of spices for health. Even spices are also used to strengthen immunity related to the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, herb medicine such as eucalyptus from Indonesia and ginseng from Korea. Thus, anchored in its historical value and contemporary needs, the development of spice commodities is imperious, particularly in Indonesia. Reestablishing the past glory of spice commodities will depend upon the ability and readiness of the country and foreign investment opportunities.

DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE

Based on the above discussion, increasing the production quantity of spice commodities in Indonesia is a challenge. It also has an opportunity to improve further the product quality of these commodities in the country.

Challenge

Globally, millions of smallholders are involved in producing spices, which are an important cash crop. Poor agricultural practices, lack of adequate processing facilities, and growers switching to high-value crops or jobs have caused an increase in the number of concerns around spices production, especially over long-term supply and food safety and traceability. In addition, these commodities also deal with sustainability issues such as uncontrolled pesticide use, poor wastewater management, and unacceptable labor conditions. While the need for sustainable spice commodities is clear, the demand in the market will start to grow (SSI-I, 2021).

It is estimated that Indonesia now has around 7,000 types of spice plants. Nevertheless, most of them have not been cultivated (growing wild), and merely a small part (4%) has been developed (NRC, 2018). The development of spices in Indonesia is a bit left as compared to other commodities such as food and estate crops, particularly rice and oil palm.

Opportunity

According to the Grand Review Research (GRV, 2021), the global spices market size was valued at US$5.86 billion in 2019 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 6.5% from 2020 to 2027. It also stated that increasing demand for authentic caterings globally is one of the foremost factors driving the consumption of spices. The growing fondness towards enjoying various flavors in foods and snacks is likely to prompt manufacturers to produce high-quality, appealing, and reliable products that can keep up consistent standards globally. Spices can alter the taste of specific cookeries and correlate with the flavors of various regions. For instance, the Middle East and Southeast Asia are likely to provide fusions, which are expected to gain presence in the market over the forecast period.

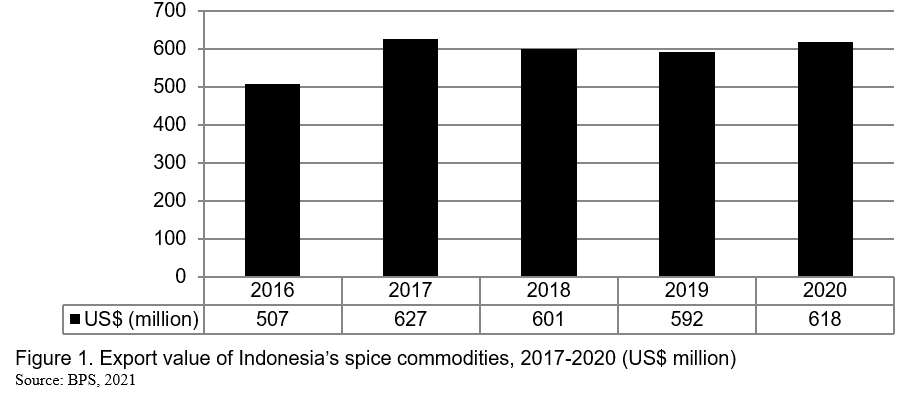

In the case of Indonesia, the average export value of spices in the last five years (2016-2020) was US$ 589 million per year or increased by about 5.63% annually (Figure 1). Market share of export value of Indonesia’s spices was only 10.10% to the global spices market. Nowadays, Indonesia ranks fourth as the world’s exporting country of spices after India, Viet Nam, and China.

Apart from fulfilling the domestic demand, Indonesia has an opportunity to expand spices export through formulating development strategies and efforts to open market access by prioritizing strategic commodities based on the growth of the existing world’s export-import. This can be carried out by selecting the export destination countries: (1) The top 20 major importers of the world’s spices; and (2) The greater extent of spices import trend than that of Indonesia's export. Based on this, Indonesia has identified the strategic spice commodities to be exported to the prospective destination countries (Table 4).

One of the efforts that can be conducted to increase competitiveness and promote the export of selected priority spice commodities of Indonesia is through developing the Geographical Indications (GIs)[1]. As a part of Intellectual Property Rights, GIs are expected to become a means of branding and promoting spices development towards increasing farmers’ income. However, the right to GIs only applies in one jurisdiction because it adheres to the “territorial principle” domestically. Therefore, there is a need to continuously pursue the GIs globally, particularly in the main export destination countries.

POLICY SUPPORT

Indonesia has set a strategic development policy for spice commodities which focuses on improving the efficiency of cultivation and production through implementing the Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) and Good Handling Practices (GHPs) to fulfill domestic and global demands. It includes postharvest handling of these commodities (MoA, 2020 and DGEC, 2020). The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) was also targeted the improvement of budget allocation by about 12.53%, namely from Rp255,276 million (US$17.60 M) in 2020 to Rp287,150 (US$19.80M) in 2024. Above all, according to NRC (2018), the extent of budget allocation for spices development was still relatively low as compared to the total budget allocation of the MoA. Consequently, budget allocation for spices development should be improved based-potential commodities sustainably.

The Directorate General of Estate Crops (DGEC, 2016) has prepared the Technical Guidelines for the Development of Spice Plants as a reference for managing activities and budgets for implementers at the central, provincial, and especially districts as beneficiaries of the activity. The objectives of this technical guideline include: (1) Increasing production and productivity of spice plants through the application of cultivation technology and area expansion; (2) Improving the income of spice plant farmers at the location of the activity; (3) Supporting spice cultivation development areas; and (4) Campaigning and facilitating certification process for Geographical Indications (GIs). It was targeted through rehabilitating and intensifying programs as well as revitalizing the spices lane.

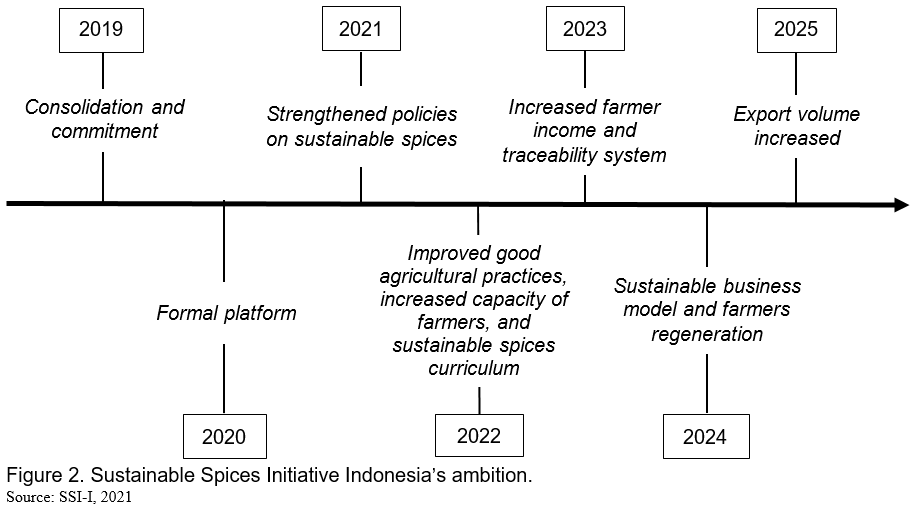

Apart from public programs-based-government intervention, the development of spice commodities in Indonesia also involved the private sector. The country has recently launched the Sustainable Spices Initiative-Indonesia (SSI-I) platform to sustainably transform the mainstream spices sector, securing future sourcing and stimulating economic growth.

The government’s commitment to realizing sustainable spices in Indonesia is manifested through the signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Ministry of Agriculture and SSI-I on the “Sustainable Development of Spice and Medicinal Plant Commodities in Supporting Exports," which was carried out on 23 March 2021. The SSI-I platform aims to develop spices in Indonesia based on consolidation and commitment toward a sustainable business model and farmers' regeneration within a five-year roadmap (Figure 2). This platform requires support from relevant stakeholders, particularly government, private sector, Non-government Organizations (NGOs), development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer organizations or communities. Hence, collaboration is the key to starting the journey towards a sustainable spices sector in Indonesia.

In the 2019-2024 the Minister of Agriculture has set a target of increasing exports of spices and herbal plants within five years to contribute positively to the national economy and the welfare of spice farmers in the next five years. The Sub-Directorate of Quality Standardization and Business Development aims to strengthen spice farmers and implement the spice trade by strengthening regulations. The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture formulate regulations relating to the production, distribution, and application of Indonesian spices, following: (1) Regulation of the Minister of Agriculture Number 53/2012 concerning guidelines for postharvest handling of nutmeg (MoA, 2012a); (2) Regulation Number 55/2012 concerning guidelines for postharvest handling of pepper (MoA, 2012b); (3) Regulation Number 10/2013 concerning Technical Guidelines for the Development of Mother Garden of Pepper (MoA, 2013); (4) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 315/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Clove Seeds (Moa, 2015a); (5) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 316/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Pepper Plants (Moa, 2015b); (6) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 320/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Nutmeg Plants (MoA, 2015c); (7) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 324/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sugar Palm Plants (MoA, 2015c); (8) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Patchouli Plant (MoA, 2015d); and (9) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sunan Candlenut Plants (MoA, 2015e). The direct application of domestic herbs and spices is regulated in Decree of the Minister of Health Number 121/2008 concerning herbal medical service standards (MoH, 2008) and Regulation of The Minister of Health Indonesia Number 6/2016 concerning Indonesian original herbal medicine formulation (MoH, 2016).

Indonesia has a problem in line with spices sector development encompassing: (1) Lack of facilities and tools for better farming; (2) Presence of pests and diseases; (3) Impact of climate change; (4) Absence of knowledge of farmers about good agricultural practices; and (4) Limited access to the global market demands. Therefore, the SSI-I has set five priority issues, namely: (1) Increasing farmers' income; (2) Improving good agricultural practices; (3) Creating a fair and profitable trade model for farmers; (4) Ensuring the implementation of sustainable agricultural policies with support from the private sector and other stakeholders; and (5) Expanding the laboratory services (SSI-I, 2021). Those are related to the economic perspective and associated with a sustainable impact on social life, environment, and governance aspects as implicitly mandated in the sustainable development goals of the United Nations agenda.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

As one of the Indonesian agricultural landmarks, it is necessary to develop spice commodities in the country. It is reasonable since these commodities have been well-known for centuries. In other words, the development of spices can be reviving the historical value of these commodities in Indonesia.

As a recommendation for the Government of Indonesia to maintain and increase the potential for global competitiveness for spices through (a) improving good cultivation techniques, (b) developing downstream industries, (c) utilizing commodity exchanges for price stabilizer, (d) improving trade and distribution facilitation, and (e) export market concentration. An effective export improvement strategy for Indonesia is to strengthen commodity competitiveness by promoting, penetrating and developing foreign export market commodities to compete in importing countries.

Apart from government intervention, it is recommended that the involvement of relevant stakeholders such as the private sector, NGOs, development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer communities to develop spice commodities sustainably. Above all, it is recommended that the investments of both national and international entities are based on natural and human resources and policy support toward improving the spice commodities in Indonesia.

REFERENCES

Aninsi, N. 2021. 25 Macam Rempah dan Manfaatnya bagi Kesehatan (25 Kinds of Spices and Its Health Benefits).Retrieved from: https://katadata.co.id/safrezifitra/berita/6140d527ec5ca/25-macam-rempah... (11 October 2021).

BPPP. 2017. Potensi Ekspor Rempah-rempah Indonesia (Potential Export of Indonesian Spices). Trade Assessment and Development Agency). Badan Pengkajian dan Pengembangan Perdagangan (Trade Assessment and Development Agency). Indonesia Ministry of Trade. Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Ekspor Tanaman Obat, Aromatik, dan Rempah-Rempah menurut Negara Tujuan Utama (Exports of Medicinal Plants, Aromatics, and Spices by Main Destination Countries), 2012-2020. Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta

DGEC. 2016. Pedoman Teknis Pengembangan Tanaman Rempah (Technical Guidelines for Spice Plant Development). Directorate General of Estate Crops, Indonesian Ministry of Agrciulture. Jakarta.

DGEC. 2020. Rencana Strategis Direktorat Jenderal Perkebunan 2020-2024 (Strategic Plan of Directorate General of Estate Crops 2020-2024). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GRV. 2021. Market Analysis Report: Spices Market Size, Share, and Trends Analysis by Product, by Form, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2020-2027. Grand Published in October 2020. Grand Review Research, Inc. Retrieved from: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/spices-market# (6 October 2021). San Francisco.

Iqbal, M. 2018. Menguak Sejarah Kejayaan dan Merajut Peluang Pengembangan Komoditas Rempah-rempah (Revealing the History of Success and Sewing Opportunities for the Development of Spice Commodities). Catra Magazine, Vol. XXIII, Mei 2018: 9-13. Secretariat General of National Resilience Council of Indonesia. Jakarta.

MoA. 2012a. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 53 Tahun 2012 tentang Pedoman Penanganan Pascapanen Pala/Myristica fragrans (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 53/2012 concerning Guidelines for Postharvest Handling of Nutmeg/Myristica fragrans). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2012b. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 55 Tahun 2012 tentang Pedoman Penanganan Pascapanen Lada/Piper nigrum (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 55/2012 concerning Technical Guidelines for Postharvest Handling of Pepper/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2013. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 10 Tahun 2013 tentang Pedoman Teknis Pembangunan Kebun Induk Lada/Piper nigrum (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 10/2013 concerning Technical Guidelines for the Development of Mother Garden of Pepper/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015a. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 315 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Cengkih/Eugenia aromatica (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 315/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Clove Seeds/Eugenia aromatica). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015b. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 316 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Lada/Piper nigrum (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 316/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Pepper Plants/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015c. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 320 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Pala/Myristica fragrans (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 320/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Nutmeg Plants/Myristica fragrans). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015d. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 324 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Aren/Arenga pinnata (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 324/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sugar Palm Plants Arenga pinnata). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015e. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 325 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Nilam/Pogostemon cablin Benth (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Patchauli Plants/Pogostemon cablin Benth). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015f. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 330 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Kemiri Sunan/Reutealis trisperma (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sunan Candlenut Plants/Reutealis trisperma). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2020. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 259/2020 tentang Rencana Strategis Kementerian Pertanian Tahun 2020-2024 (Decree of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia Number 259/2020 concerning the Strategic Plan of the Ministry of Agriculture 2020-2024) Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoH. 2008. Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 121 Tahun 2008 tentang Standar Pelayanan Medik Herbal (Decree of the Minister of Health Number 121/2008 concerning Herbal Medical Service Standards). Indonesian Ministry of Health. Jakarta.

MoH. 2016. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 6 Tahun 2016 tentang Formularium Obat Herbal Asli Indonesia (Regulation of The Minister of Health Indonesia Number 6/2016 concerning Indonesian Original Herbal Medicine Formulation). Indonesian Ministry of Health. Jakarta.

MoLHR. 2019. Peraturan Menteri Hukum dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 tahun 2019 tentang Indikasi Geografis (Regulation of the Minister of Law and Human Rights Number 12/2019 concerning Geographical Indications). Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta.

NRC. 2018. Optimalisasi Pengembangan Komoditas Rempah-rempah guna Meningkatkan Taraf Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat dalam rangka Mendukung Ketahanan Nasional (Optimizing the Development of Spice Commodities to Improve the Community Socioeconomic Supporting of the National Resilience). Unpublished policy brief of Sekretariat Jenderal Dewan Ketahanan Nasional Indonesia (Secretariat General of National Resilience Council of Indonesia). Jakarta.

SSI-I. 2021. The Sustainable Spices Initiative-Indonesia. Retrieved from: https://sustainablespices.id/ (5 October 2021)

Sulaiman, A. A., K. Subagyono, A. Pakpahan, D. Soetopo, N. Bermawie, Hoerudin, B. Prastowo, and N. Syafaat. 2018. Membangkitkan Kejayaan Rempah Nusantara (Awakening the Glory of Indonesian Spices). First Edition (Eds. Sudaryanto, T. and Yulianto). IAARD Press. Jakarta.

UNESCO. 2021. What are the Spice Routes? Retrieved from: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/what-are-spice-routes (6 October 2021)

UNIDO and FAO. 2005. Herbs, spices, and essential oils: Post-harvest operations in developing countries. United Nations Industrial Development and Food and Agriculture of the United Nations, Rome.

von Rintelen, K., E. Arida, and C. Häuse. 2017. A Review of Biodiversity-related Issues and Challenges in Mega Diverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian Countries. Retrieved from: at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319628690 (6 October 2021).

[1] Geographical Indications (GIs) is a sign indicating the area of origin of an item and product which due to geographical, environmental factors, including natural factors, human factors, or a combination of these two factors provides a certain reputation, quality, and characteristics to the goods and products produced. It is an exclusive right granted to the holders of registered GI, as long as the reputation, quality, and characteristics that are the basis for protecting the GI still exist (MoLHR, 2019).

Development of Indonesia’s Spice Commodities: Historical Value and Future Perspective

ABSTRACT

As one of the biodiversity sources, there is a need to develop spice commodities in Indonesia. This article aims to discuss the development of these commodities based on historical value and its future perspective. Spices can be grown in all areas of the country; however, the performance of these crops depends upon technical and non-technical necessities. One of the efforts that can be conducted to increase competitiveness and promote the export of Indonesia's selected priority spice commodities is developing the Geographical Indications (GIs). The development of Indonesia’s spice commodities requires government intervention and the participation of other stakeholders, particularly the private sector, NGOs, development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer communities. It is not only to increase the productivity but also to expand the export in the global market toward enhancing the foreign earning and improving farmers’ income. Apart from government intervention, it is recommended that the investment of both national and international entities are based on natural and human resources toward improving the spice commodities in the country.

Keywords: spice commodities, development, history, perspective, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is listed as one of the 17 global mega diversity countries (Kristina et al., 2017). Located in the equator, which only has two seasons, namely the rainy and dry seasons, Indonesia's crops continuously exist throughout the year. One of them is the spice plants which have historically been an attraction for other nations to come to this country.

Indonesia has experienced a long history that is both proud and heartbreaking related to spices. For centuries Indonesia was the main supplier of spices to the rest of the world. The main commodities were traded along the route connecting Southeast Asia and Europe, which became known as the Maritime Silk Road. Nevertheless, the high value of the spices brought power and wealth to the supplier kingdoms and lured European merchants and their mercenaries to Indonesian shores back in the 16th century. Their arrival started the colonization of the archipelago, especially by the Dutch, for over 350 years (Jakarta Post, 2015 and Sulaiman et al., 2018).

The most well-known spice commodities are nutmeg, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger in the Indonesian context. Nutmeg and clove can be categorized as native commodities of Indonesia, while pepper, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger were adopted from other countries (Sulaiman et al., 2018). Based on the historical value, the development of spices in Indonesia is imperative. The future perspective of these commodities is potential in line with the existing country’s economic growth, particularly in the Asian region. Therefore, this article discusses the development of the country’s spice commodities based-historical value and its future perspective. Initially, it discusses the introduction, followed by the feature of spice commodities, historical value, development perspective, and policy support. Finally, the article addresses some conclusions and recommendations.

SPICE COMMODITIES

Technically, UNIDO and FAO (2005) define that spices are used for flavor, color, aroma, and preservation of food or beverages. Many parts of plant-made spices including barks, buds, flowers, fruits, leaves, rhizomes, roots, seeds, stigmas, and styles or the entire plant tops. The most important spices traditionally traded throughout the world are products of tropical environments.

In terms of world trade value, the most important spice crops from the tropical regions are pepper, capsicums, nutmeg/mace, cardamom, pimento, vanilla, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, and turmeric. The characteristics and environmental descriptions of the well-known spice commodities in Indonesia, namely nutmeg, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, vanilla, and ginger, can be seen in Table 1.

The spice-derived products can be classified into three groups, namely: (1) Seasoning or imparting aroma in foods that are fitting for consumption (food grade); (2) Herbs related to medicine or fragrance; and (3) Essential oils produced through a distillation process (UNIDO and FAO, 2005). The ingredients used for spices, herbs, and essential oils can be derived from: (1) Seeds and fruits (e.g. nutmeg, vanilla); (2) Flowers and buds (e.g. cloves, perfume tree); (3) Leaves and stems (e.g. pattern, screw pine); (3) Roots and rhizomes or tubers (e.g. turmeric, ginger); and (4) Leather, wood, and resins or gums (e.g. cinnamon, frankincense). For essential oils, the extent of use is wider than spices and herbs, in which it applied for: (1) Aromatic industry (e.g. culinary, cigarettes); (2) Cosmetic industry (e.g. perfume, soap); (3) Pharmaceutical industry (e.g. antiviral, antimicrobial, antifungal); and (4) Other industries (e.g. paper, cleaners, lubricants, plastics). Hence, spices have multiple functions (Iqbal, 2018), starting from the need for: (1) Food (flavors, preservatives, antioxidants, dyes, instant drinks, and functional foods or foods that can provide more benefits in addition to their basic nutritional functions); (2) Pharmacology (related to drugs); (3) Cosmetics (e.g. shampoo, toothpaste, lotion/moisturizer); (4) Agriculture (e.g. insecticides, pesticides); (5) Chemicals (e.g. varnish, turpentine); to (6) Others (e.g. mixed kretek cigarettes).

Spices can grow all over areas of Indonesia; however, the good performance of these plants depends upon land suitability, environmental circumstance, and cultivation practices. The country's central producing areas of well-known spice commodities are presented in Table 2 and Appendix Figure 1 to 6.

HISTORICAL VALUE

Semantically, the word "spice" comes from the Latin species, which means an item of special value compared to ordinary articles of trade. The important spices had ritual and medical values and could only grow in the tropical east and be transported to the west, known as Maritime Silk Road (UNESCO, 2021).

Historically, the first people to come to Indonesia to find spice commodities were from Arabia and China, namely during the Sriwijaya Kingdom (around the 7th to 10th century). Then in the subsequent period came the Europeans (Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Dutch), which further made Indonesia a colony (colonialism) for centuries, especially by the Dutch (Iqbal, 2018). The philosophy brought by Europeans to Indonesia at that time was known as Gold (looking for precious spices like gold), Gospel (performing sacred duties), and Glory (getting success).

The success story of spice commodities was in the 1600s to 1800s within a trading partnership or company of the Netherlands, namely “Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC)." Through monopolizing spices in the East Indies, the VOC became the richest multinational giant in history and was listed as the first company to issue shares in the world with an asset value of around 78 million guilders (US$ 7.9 trillion). It is roughly equal to the joint assets of 20 top companies in the modern era, namely Apple, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, ExxonMobil, Google, Microsoft, Tencent, Wells Fargo, and others, or comparable to the combined Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Japan and Germany and greater than the foreign exchange reserves of the current largest country in the world, namely China with a value of around US$ 3.23 trillion (NRC, 2018).

After two centuries of its glories, the role of spices commodities in the mid-1900s tended to decrease along with technological invention, particularly artificial refrigeration. However, spice commodities have become popular due to the alteration of the world’s population lifestyle in line with medical treatments, culinary services, cosmetic requirements, and others.

Table 3 summarizes the benefit of spices for health. Even spices are also used to strengthen immunity related to the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, herb medicine such as eucalyptus from Indonesia and ginseng from Korea. Thus, anchored in its historical value and contemporary needs, the development of spice commodities is imperious, particularly in Indonesia. Reestablishing the past glory of spice commodities will depend upon the ability and readiness of the country and foreign investment opportunities.

DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE

Based on the above discussion, increasing the production quantity of spice commodities in Indonesia is a challenge. It also has an opportunity to improve further the product quality of these commodities in the country.

Challenge

Globally, millions of smallholders are involved in producing spices, which are an important cash crop. Poor agricultural practices, lack of adequate processing facilities, and growers switching to high-value crops or jobs have caused an increase in the number of concerns around spices production, especially over long-term supply and food safety and traceability. In addition, these commodities also deal with sustainability issues such as uncontrolled pesticide use, poor wastewater management, and unacceptable labor conditions. While the need for sustainable spice commodities is clear, the demand in the market will start to grow (SSI-I, 2021).

It is estimated that Indonesia now has around 7,000 types of spice plants. Nevertheless, most of them have not been cultivated (growing wild), and merely a small part (4%) has been developed (NRC, 2018). The development of spices in Indonesia is a bit left as compared to other commodities such as food and estate crops, particularly rice and oil palm.

Opportunity

According to the Grand Review Research (GRV, 2021), the global spices market size was valued at US$5.86 billion in 2019 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 6.5% from 2020 to 2027. It also stated that increasing demand for authentic caterings globally is one of the foremost factors driving the consumption of spices. The growing fondness towards enjoying various flavors in foods and snacks is likely to prompt manufacturers to produce high-quality, appealing, and reliable products that can keep up consistent standards globally. Spices can alter the taste of specific cookeries and correlate with the flavors of various regions. For instance, the Middle East and Southeast Asia are likely to provide fusions, which are expected to gain presence in the market over the forecast period.

In the case of Indonesia, the average export value of spices in the last five years (2016-2020) was US$ 589 million per year or increased by about 5.63% annually (Figure 1). Market share of export value of Indonesia’s spices was only 10.10% to the global spices market. Nowadays, Indonesia ranks fourth as the world’s exporting country of spices after India, Viet Nam, and China.

Apart from fulfilling the domestic demand, Indonesia has an opportunity to expand spices export through formulating development strategies and efforts to open market access by prioritizing strategic commodities based on the growth of the existing world’s export-import. This can be carried out by selecting the export destination countries: (1) The top 20 major importers of the world’s spices; and (2) The greater extent of spices import trend than that of Indonesia's export. Based on this, Indonesia has identified the strategic spice commodities to be exported to the prospective destination countries (Table 4).

One of the efforts that can be conducted to increase competitiveness and promote the export of selected priority spice commodities of Indonesia is through developing the Geographical Indications (GIs)[1]. As a part of Intellectual Property Rights, GIs are expected to become a means of branding and promoting spices development towards increasing farmers’ income. However, the right to GIs only applies in one jurisdiction because it adheres to the “territorial principle” domestically. Therefore, there is a need to continuously pursue the GIs globally, particularly in the main export destination countries.

POLICY SUPPORT

Indonesia has set a strategic development policy for spice commodities which focuses on improving the efficiency of cultivation and production through implementing the Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) and Good Handling Practices (GHPs) to fulfill domestic and global demands. It includes postharvest handling of these commodities (MoA, 2020 and DGEC, 2020). The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) was also targeted the improvement of budget allocation by about 12.53%, namely from Rp255,276 million (US$17.60 M) in 2020 to Rp287,150 (US$19.80M) in 2024. Above all, according to NRC (2018), the extent of budget allocation for spices development was still relatively low as compared to the total budget allocation of the MoA. Consequently, budget allocation for spices development should be improved based-potential commodities sustainably.

The Directorate General of Estate Crops (DGEC, 2016) has prepared the Technical Guidelines for the Development of Spice Plants as a reference for managing activities and budgets for implementers at the central, provincial, and especially districts as beneficiaries of the activity. The objectives of this technical guideline include: (1) Increasing production and productivity of spice plants through the application of cultivation technology and area expansion; (2) Improving the income of spice plant farmers at the location of the activity; (3) Supporting spice cultivation development areas; and (4) Campaigning and facilitating certification process for Geographical Indications (GIs). It was targeted through rehabilitating and intensifying programs as well as revitalizing the spices lane.

Apart from public programs-based-government intervention, the development of spice commodities in Indonesia also involved the private sector. The country has recently launched the Sustainable Spices Initiative-Indonesia (SSI-I) platform to sustainably transform the mainstream spices sector, securing future sourcing and stimulating economic growth.

The government’s commitment to realizing sustainable spices in Indonesia is manifested through the signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Ministry of Agriculture and SSI-I on the “Sustainable Development of Spice and Medicinal Plant Commodities in Supporting Exports," which was carried out on 23 March 2021. The SSI-I platform aims to develop spices in Indonesia based on consolidation and commitment toward a sustainable business model and farmers' regeneration within a five-year roadmap (Figure 2). This platform requires support from relevant stakeholders, particularly government, private sector, Non-government Organizations (NGOs), development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer organizations or communities. Hence, collaboration is the key to starting the journey towards a sustainable spices sector in Indonesia.

In the 2019-2024 the Minister of Agriculture has set a target of increasing exports of spices and herbal plants within five years to contribute positively to the national economy and the welfare of spice farmers in the next five years. The Sub-Directorate of Quality Standardization and Business Development aims to strengthen spice farmers and implement the spice trade by strengthening regulations. The Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture formulate regulations relating to the production, distribution, and application of Indonesian spices, following: (1) Regulation of the Minister of Agriculture Number 53/2012 concerning guidelines for postharvest handling of nutmeg (MoA, 2012a); (2) Regulation Number 55/2012 concerning guidelines for postharvest handling of pepper (MoA, 2012b); (3) Regulation Number 10/2013 concerning Technical Guidelines for the Development of Mother Garden of Pepper (MoA, 2013); (4) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 315/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Clove Seeds (Moa, 2015a); (5) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 316/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Pepper Plants (Moa, 2015b); (6) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 320/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Nutmeg Plants (MoA, 2015c); (7) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 324/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sugar Palm Plants (MoA, 2015c); (8) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Patchouli Plant (MoA, 2015d); and (9) Decree of the Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sunan Candlenut Plants (MoA, 2015e). The direct application of domestic herbs and spices is regulated in Decree of the Minister of Health Number 121/2008 concerning herbal medical service standards (MoH, 2008) and Regulation of The Minister of Health Indonesia Number 6/2016 concerning Indonesian original herbal medicine formulation (MoH, 2016).

Indonesia has a problem in line with spices sector development encompassing: (1) Lack of facilities and tools for better farming; (2) Presence of pests and diseases; (3) Impact of climate change; (4) Absence of knowledge of farmers about good agricultural practices; and (4) Limited access to the global market demands. Therefore, the SSI-I has set five priority issues, namely: (1) Increasing farmers' income; (2) Improving good agricultural practices; (3) Creating a fair and profitable trade model for farmers; (4) Ensuring the implementation of sustainable agricultural policies with support from the private sector and other stakeholders; and (5) Expanding the laboratory services (SSI-I, 2021). Those are related to the economic perspective and associated with a sustainable impact on social life, environment, and governance aspects as implicitly mandated in the sustainable development goals of the United Nations agenda.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

As one of the Indonesian agricultural landmarks, it is necessary to develop spice commodities in the country. It is reasonable since these commodities have been well-known for centuries. In other words, the development of spices can be reviving the historical value of these commodities in Indonesia.

As a recommendation for the Government of Indonesia to maintain and increase the potential for global competitiveness for spices through (a) improving good cultivation techniques, (b) developing downstream industries, (c) utilizing commodity exchanges for price stabilizer, (d) improving trade and distribution facilitation, and (e) export market concentration. An effective export improvement strategy for Indonesia is to strengthen commodity competitiveness by promoting, penetrating and developing foreign export market commodities to compete in importing countries.

Apart from government intervention, it is recommended that the involvement of relevant stakeholders such as the private sector, NGOs, development partners, academicians, research institutions, and farmer communities to develop spice commodities sustainably. Above all, it is recommended that the investments of both national and international entities are based on natural and human resources and policy support toward improving the spice commodities in Indonesia.

REFERENCES

Aninsi, N. 2021. 25 Macam Rempah dan Manfaatnya bagi Kesehatan (25 Kinds of Spices and Its Health Benefits).Retrieved from: https://katadata.co.id/safrezifitra/berita/6140d527ec5ca/25-macam-rempah... (11 October 2021).

BPPP. 2017. Potensi Ekspor Rempah-rempah Indonesia (Potential Export of Indonesian Spices). Trade Assessment and Development Agency). Badan Pengkajian dan Pengembangan Perdagangan (Trade Assessment and Development Agency). Indonesia Ministry of Trade. Jakarta.

BPS. 2021. Ekspor Tanaman Obat, Aromatik, dan Rempah-Rempah menurut Negara Tujuan Utama (Exports of Medicinal Plants, Aromatics, and Spices by Main Destination Countries), 2012-2020. Badan Pusat Statistik Indonesia (Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta

DGEC. 2016. Pedoman Teknis Pengembangan Tanaman Rempah (Technical Guidelines for Spice Plant Development). Directorate General of Estate Crops, Indonesian Ministry of Agrciulture. Jakarta.

DGEC. 2020. Rencana Strategis Direktorat Jenderal Perkebunan 2020-2024 (Strategic Plan of Directorate General of Estate Crops 2020-2024). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GRV. 2021. Market Analysis Report: Spices Market Size, Share, and Trends Analysis by Product, by Form, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2020-2027. Grand Published in October 2020. Grand Review Research, Inc. Retrieved from: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/spices-market# (6 October 2021). San Francisco.

Iqbal, M. 2018. Menguak Sejarah Kejayaan dan Merajut Peluang Pengembangan Komoditas Rempah-rempah (Revealing the History of Success and Sewing Opportunities for the Development of Spice Commodities). Catra Magazine, Vol. XXIII, Mei 2018: 9-13. Secretariat General of National Resilience Council of Indonesia. Jakarta.

MoA. 2012a. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 53 Tahun 2012 tentang Pedoman Penanganan Pascapanen Pala/Myristica fragrans (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 53/2012 concerning Guidelines for Postharvest Handling of Nutmeg/Myristica fragrans). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2012b. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 55 Tahun 2012 tentang Pedoman Penanganan Pascapanen Lada/Piper nigrum (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 55/2012 concerning Technical Guidelines for Postharvest Handling of Pepper/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2013. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 10 Tahun 2013 tentang Pedoman Teknis Pembangunan Kebun Induk Lada/Piper nigrum (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 10/2013 concerning Technical Guidelines for the Development of Mother Garden of Pepper/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015a. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 315 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Cengkih/Eugenia aromatica (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 315/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Clove Seeds/Eugenia aromatica). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015b. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 316 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Lada/Piper nigrum (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 316/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Pepper Plants/Piper nigrum). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015c. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 320 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Pala/Myristica fragrans (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 320/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Nutmeg Plants/Myristica fragrans). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015d. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 324 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Aren/Arenga pinnata (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 324/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sugar Palm Plants Arenga pinnata). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015e. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 325 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Nilam/Pogostemon cablin Benth (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 325/2015 concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Patchauli Plants/Pogostemon cablin Benth). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2015f. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 330 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Produksi, Sertifikasi, Peredaran, dan Pengawasan Benih Tanaman Kemiri Sunan/Reutealis trisperma (Decree of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number concerning Guidelines for Production, Certification, Distribution, and Supervision of Sunan Candlenut Plants/Reutealis trisperma). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2020. Keputusan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 259/2020 tentang Rencana Strategis Kementerian Pertanian Tahun 2020-2024 (Decree of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia Number 259/2020 concerning the Strategic Plan of the Ministry of Agriculture 2020-2024) Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoH. 2008. Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 121 Tahun 2008 tentang Standar Pelayanan Medik Herbal (Decree of the Minister of Health Number 121/2008 concerning Herbal Medical Service Standards). Indonesian Ministry of Health. Jakarta.

MoH. 2016. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor 6 Tahun 2016 tentang Formularium Obat Herbal Asli Indonesia (Regulation of The Minister of Health Indonesia Number 6/2016 concerning Indonesian Original Herbal Medicine Formulation). Indonesian Ministry of Health. Jakarta.

MoLHR. 2019. Peraturan Menteri Hukum dan Hak Asasi Manusia Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 tahun 2019 tentang Indikasi Geografis (Regulation of the Minister of Law and Human Rights Number 12/2019 concerning Geographical Indications). Indonesian Ministry of Law and Human Rights. Jakarta.

NRC. 2018. Optimalisasi Pengembangan Komoditas Rempah-rempah guna Meningkatkan Taraf Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat dalam rangka Mendukung Ketahanan Nasional (Optimizing the Development of Spice Commodities to Improve the Community Socioeconomic Supporting of the National Resilience). Unpublished policy brief of Sekretariat Jenderal Dewan Ketahanan Nasional Indonesia (Secretariat General of National Resilience Council of Indonesia). Jakarta.

SSI-I. 2021. The Sustainable Spices Initiative-Indonesia. Retrieved from: https://sustainablespices.id/ (5 October 2021)

Sulaiman, A. A., K. Subagyono, A. Pakpahan, D. Soetopo, N. Bermawie, Hoerudin, B. Prastowo, and N. Syafaat. 2018. Membangkitkan Kejayaan Rempah Nusantara (Awakening the Glory of Indonesian Spices). First Edition (Eds. Sudaryanto, T. and Yulianto). IAARD Press. Jakarta.

UNESCO. 2021. What are the Spice Routes? Retrieved from: https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/what-are-spice-routes (6 October 2021)

UNIDO and FAO. 2005. Herbs, spices, and essential oils: Post-harvest operations in developing countries. United Nations Industrial Development and Food and Agriculture of the United Nations, Rome.

von Rintelen, K., E. Arida, and C. Häuse. 2017. A Review of Biodiversity-related Issues and Challenges in Mega Diverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian Countries. Retrieved from: at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319628690 (6 October 2021).

[1] Geographical Indications (GIs) is a sign indicating the area of origin of an item and product which due to geographical, environmental factors, including natural factors, human factors, or a combination of these two factors provides a certain reputation, quality, and characteristics to the goods and products produced. It is an exclusive right granted to the holders of registered GI, as long as the reputation, quality, and characteristics that are the basis for protecting the GI still exist (MoLHR, 2019).