ABSTRACT

Direct Payment Schemes (DPS) has played a central role in Korean agriculture, but not free from caveats and criticism. Against those problems, DPS reform has been in active progress these days. The author attempts to provide suggestions as follows. 1) The goal of the reform should be enhancing sustainability and multifunctionality rather than income support. 2) The scope of multifunctionality and eligible participants should be widened. 3) In the long run, the Selective DPS should be placed at the center of the new scheme.

BACKGROUNDS

Currently, nine kinds of Direct Payment Schemes (hereinafter DPS) have been implemented under the ACT ON PRESERVING AGRICULTURAL INCOME and the SPECIAL ACT ON ASSISTANCE TO FARMERS, FISHERMEN, ETC. FOLLOWING THE CONCLUSION OF FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS (Table 1).

Table 1. DPS status as of 2019

|

DPS

|

Main Purpose

|

|

Fixed DPS for Paddy Rice (FDPS)

|

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of farm income increment and enhancing multifunctionality.

|

|

Variable DPS for Paddy Rice (VDPS)

|

Increasing rice farm income by compensating income loss given a certain criterion is met.

|

|

Fixed DPS for Upland Crops (UDPS)

|

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of upland farm income increment.

|

|

Naturally Constrained Area DPS (NDPS)

|

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of maintaining production capacity in naturally constrained (less favored) areas.

|

|

Organic Farming DPS (ODPS)

|

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of expansion of organic farming by compensating income loss at the early conversion stage.

|

|

Landscape Enhancement DPS

(LDPS)

|

Providing per hectare payments for planting landscape-enhancing crops in pursuit of landscape management.

|

|

Generation Renewal DPS (GDPS)

|

Providing payments to promote generation renewal.

|

|

FTA-relevant Compensation DPS

(FCDPS)

|

Compensating a part of income loss caused by FTA implementation.

|

|

FTA-relevant-exiting Compensation DPS (FEDPS)

|

Enabling smooth and voluntary exiting of farms caused by FTA implementation.

|

Source: NABO (2019).

The DPS budget has increased steadily since its introduction to account for 17% of the total agricultural budget in 2018 (2.4 trillion KRW or about 2.0 billion USD) (Table 2). That is, DPS has played a central role in terms of farm management stabilization and income support. In particular, Fixed DPS for Paddy Rice (FDPS) is the single largest and most important one, accounting for 66% of the 2019 DPS budget.[1]

Table 2. DPS budget during 2016-2019 Unit: 100 mil. KRW, %

| |

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

|

amount

|

share

|

amount

|

share

|

amount

|

share

|

amount

|

share

|

|

DPS Total

|

21,124

|

100.0

|

28,543

|

100.0

|

24,390

|

100.0

|

16,122

|

100.0

|

|

FDPS

|

8,240

|

39.0

|

8,160

|

28.6

|

8,090

|

33.2

|

8,028

|

49.8

|

|

VDPS

|

7,193

|

34.1

|

14,900

|

52.2

|

10,800

|

44.6

|

2,533

|

15.7

|

|

GDPS

|

573

|

2.7

|

545

|

1.9

|

497

|

2.0

|

472

|

2.9

|

|

NDPS

|

395

|

1.9

|

472

|

1.7

|

506

|

2.1

|

546

|

3.4

|

|

UDPS

|

2,118

|

10.0

|

1,906

|

6.7

|

1,937

|

7.9

|

2,078

|

12.9

|

|

LDPS

|

136

|

0.6

|

116

|

0.4

|

93

|

0.4

|

84

|

0.5

|

|

ODPS

|

437

|

2.1

|

411

|

1.4

|

435

|

1.8

|

381

|

2.4

|

|

FCDPS

|

1,005

|

4.8

|

1,005

|

3.5

|

1,005

|

4.1

|

1,000

|

6.2

|

|

FEDPS

|

1,027

|

4.9

|

1,027

|

3.6

|

1,027

|

4.2

|

1,000

|

6.2

|

|

MAFRA Total

|

143,681

|

-

|

144,887

|

-

|

144,996

|

-

|

146,596

|

-

|

Source: Modified from Park et al. (2016).

Nevertheless, criticism regarding limitations inherent in current DPS continues to be raised, and there are number of claims requiring that reforming the current system is imperative. The main problems to be addressed are as follows. 1) Financial resource allocation: DPS budgets are largely concentrated on paddy rice sector causing inequality concern; 2) Coupling: a current VDPS potentially stimulated over-production, 3) Inconsistency and/or conflicts between objectives of individual DPS, e.g. those of FDPS/VDPS and GDPS. 4) In spite of rhetorical emphasis on multifunctionality of agriculture, actual and empirical provision of such functions is in question.

This article aims at outlining recent discussions regarding DPS reform and making suggestions with a particular focus on strengthening multifunctionality of agriculture.

Current discussions on DPS reform in Korea

In the meantime, the DPS proposals have shared Basic and Selective Payment Schemes architecture. However, the detailed structure and features vary across proposals.[2]

Some have put emphasis on reforming, among others, of paddy rice-related DPS including FDPS and VDPS (e.g. Lee and Sagong 2011; Lee 2013, 2017; Park et al. 2016). Proponents of this position argue that the current DPS should be reformed in such a way that structural overproduction of rice as well as income support inequality concerns can be alleviated. On the other hand, some argue that the multifunctionality of agriculture should be expanded and fulfilled to meet changing societal demands and, at the same time, guaranteeing the sustainability of agriculture (e.g. Kim, Im and Lee 2017; Kang 2017; Lee 2019; Rhew, Cho and Kim 2018; PCPP 2018). This position has paid more attention to what we call Selective DPS. Others argue that both positions matter and that they are to be balanced (e.g. Kim et al. 2017).

Standpoint 1: “Income support still matters.”

Lee and Sagong (2011) and Lee (2013) suggested that the current income support measures should be expanded to be effective as a policy instrument. The main goal is to extend the coverage of FCDPS payment to "all major commodities affected by market opening." They argued that the proposed scheme can be decoupled by setting up the base year cultivation area, and operating the VDPS separately. The suggested model was similar to the former Counter-Cyclical Payments (current Price Loss Coverage) in the U.S.[3] Lee (2017) further developed his previous idea to insist that current VDPS and FCDPS be integrated into so called CCP-type scheme and that the coverage of the new scheme should be widened.

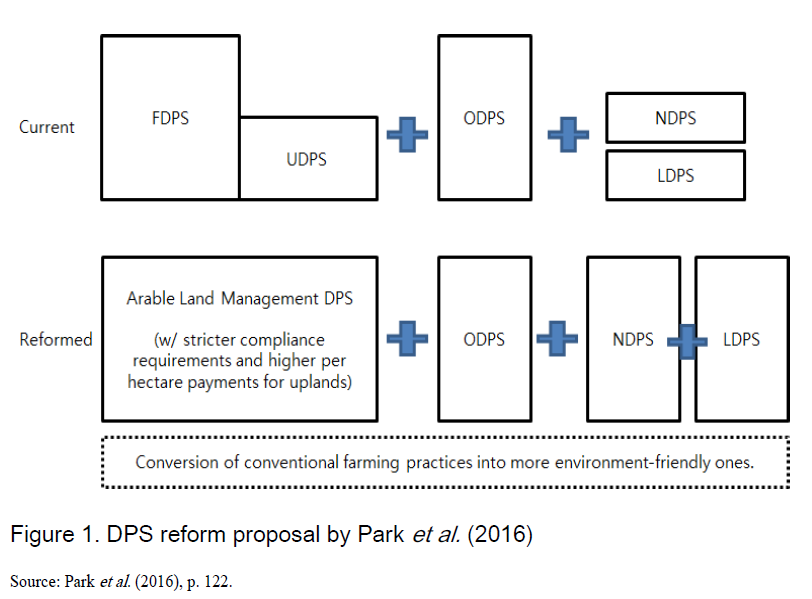

Park et al. (2016) suggested the future orientation of DPS as follows (Figure 1). 1) The scheme may play a role for income support and stabilization, but other measures such as crop insurance and check-off need to be strengthened. 2) Payment criteria are desired to be switched from commodity to land-base in that all kinds of arable land matter regardless of what sorts of crops are being planted. 3) Management requirement and/or reference levels should be stricter to permit the reform to be more persuasive, especially for the public. 4) Mitigating structural over-supply of paddy rice via more equitable DPS resource allocation is also important.

Standpoint 2: “Income support matters, but more important is meeting societal demand”

Lim, Im and Lee (2017) and Lee (2019) argued that introducing new DPS remunerating specific activities generating environmental and ecological benefits with public good properties would contribute to social welfare increments. To that end, they insist that the current system[1] should consist of Basic DPS and purpose-specific DPS to better serve individual goals (Figure 2).

Kang (2017) argued that the future agricultural policy should be directed to “multifunctional agriculture for all citizens” and the budget should be correspondingly allocated. Along with this direction, she argued, that the current DPS also needs to be newly set up, say, such as Food Security Enhancement Program and DPS for Contribution by Agriculture (Table 3).

Table 3. DPS reform proposal by Kang (2017)

|

Type

|

Title

|

Example

|

|

Basic

|

Food Security Enhancement Program or Food Security DPS or Food Self-provision DPS

|

|

|

Selective

(topping-up)

|

DPS for Contribution by Agriculture or DPS for Societal Service by Agriculture or Multifunctional Agriculture DPS

|

- Ag. Environment Conservation Program

- Young Farmers’ Scheme

- Rural Community and Safety Net Program

- Small Farmers’ Program

|

Source: Kang (2017).

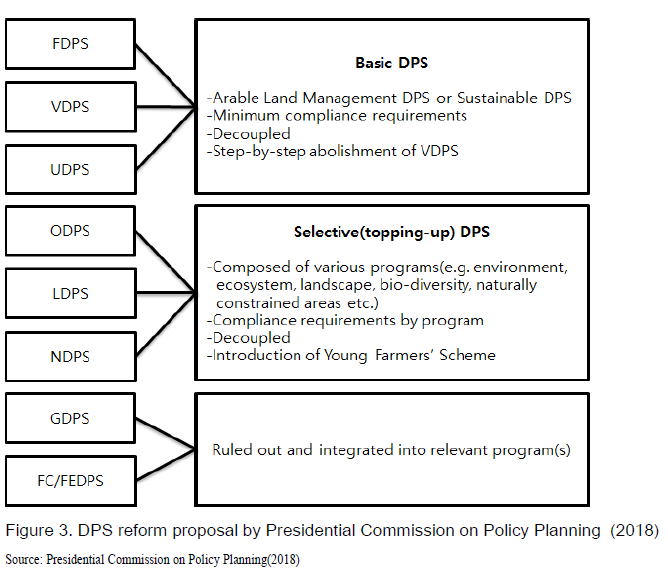

Presidential Commission on Policy Planning (PCPP 2018) handed in its own proposal (Figure 3) on the ground that DPS reform is a necessary prerequisite for agricultural policy paradigm shift. PCPP’s proposal regarding the reform direction as “from income support to remuneration for multifunctional agriculture and its benefits for the people.”

Standpoint 3: “Both matter. A newly balanced equilibrium should be sought.”

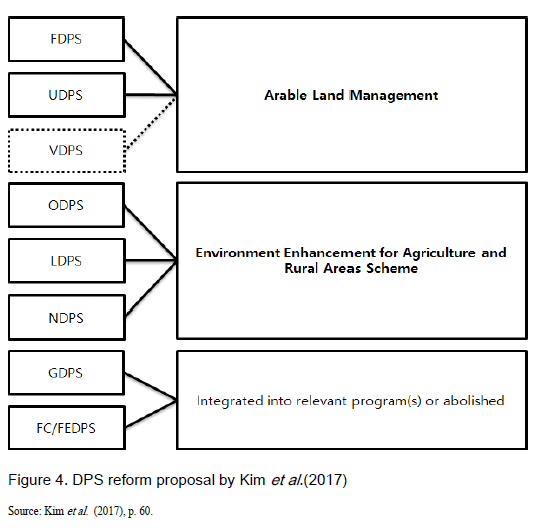

A proposal by Kim et al. (2017) centered on a couple of things (Figure 4). First, degree of relevance with multifunctionality and target should be placed as payment criteria. Second, based on the proposed criteria, a current Scheme may be reformed to Arable Land Management DPS (Basic Payment type) and Environment Enhancement for Agriculture and Rural Areas Scheme (selective/topping-up payment type), which is a way simpler than the current one.

Legislation in progress

Grounded on previously mentioned discussions, a legal proposal has been handed in September 9, 2019, which repealed the former ACT ON PRESERVING AGRICULTURAL INCOME. The new proposal, now in effect, is named ACT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF DIRECT PAYMENT SCHEME FOR ENHANCING PUBLIC FUNCTION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS. Its implementing ordinance also has been passed by Cabinet meeting in April 21, 2020. As a result, the new DPS will be in effect as of May 1, 2020.

Main features of the new scheme are as follows (Table 4). First, the purpose of the Act includes “Enhancement of multifunctionality out of agriculture and rural areas, and farmers’ income stabilization.” Second, the new DPS consists of Basic Public Benefit DPS and Selective Public Benefit DPS. The former again is comprised of Small Farmers’ Scheme (newly introduced) and Area-based Payment Scheme (similar with a current one except that a regressive per hectare payment formula is added). To be eligible for Small Farmers’ Scheme, any applicant shall meet all of 8 relevant requirements. An eligible applicant can, regardless of size of planted acres, receive about 1,000 USD annually, which is, on average, larger than his/her previous payment records by 2.8 times. Third, in total 17 mandatory requirements for applicants[1] to be eligible for the payments have been set up, which include maintaining shapes and functions of arable lands, proper use of pesticides and fertilizers, taking up multifunctionality-related education and so on. Additionally, restriction of planted acres may be implemented when necessary. Fourth, detailed descriptions regarding Selective Public Benefit DPS are yet to be provided. The proposal says that such things are to be included in its Enforcement Decree.

Table 4. An overview of Legal reform proposal (No. 2022404) as of Sep. 9, 2019

|

Current

|

Proposal

|

|

FDPS

|

Basic Payments

Scheme

|

- Small Farmers’ Scheme (fixed amounts)

- Acre-based Payments (regressive per hectare payments)

|

|

UDPS

|

|

VDPS

|

|

NDPS

|

|

ODPS

|

Selective Payments

Scheme

|

- ODPS, ODPS(livestock), LDPS, and Strategic Commodity Payments Scheme

|

|

ODPS(livestock)

|

|

LDPS

|

|

GDPS

|

GDPS

|

|

|

FCDPS

|

FCDPS

|

|

|

FEDPS

|

FEDPS

|

|

Source: Bill Information

Still a long way to go: Suggestions

In spite of enormous endeavors and efforts made so far, the DPS reform is not free from a number of challenges and caveats. In this sense, the author would like to make some suggestions.

Question 1: What should be an ultimate orientation point of the DPS reform?

Suggestion 1: Enhancing sustainability via multifunctionality, and income support as a stepping stone.

One of the largest debates on the legal proposal is whether it is appropriate to include income support as a manifest aim of DPS. The author believes that, in spite of its importance, income support may become a main goal of DPS itself and/or orientation of the reform. Enabling farmers’ to gain ‘sufficient’ level of income and thus allowing them to enjoy a decent quality of life cannot be too much emphasized. However, as long as we talk over the reform, addressing the farm income problem may as well be ‘necessary condition’ and ‘means’ of providing them an incentive such that they may play a role not only as ‘a producer of food and fiber’ but as ‘a manager of territory and environment.’[2]

Question 2: What functions should be contained in the multifunctionality?

Suggestion 2: Way wider than what have been conventionally defined in Korean agriculture.

Consensus on the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture is yet to be reached. The FRAMEWORK ACT ON AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES, RURAL COMMUNITY AND FOOD INDUSTRY, in its Article 3, provides a rough scope of multifunctionality of agriculture and rural areas, which is placed at the debate arena as well. Some argued that those functions directly or indirectly related with agricultural production may be included in the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture. Others insist that the scope may be widened such that rural territory and management and social safety net become a part of the scheme. Grounding on the concept and properties of multifunctionality of agriculture, the author is on the side of the latter. The author would like to substitute the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture in such a way presented in Figure 5. First, currently defined functions may be elaborated to better serve the ever changing societal demand (① in Figure 5).[3] For example, the newly fine-tuned terms may need to include not only “steady sellers” such as food security, but “new arrivals” such as coping with climate change, biodiversity, and animal welfare. Second, the scope may be further widened to explicitly aim at mitigating negative externalities stemming from agricultural activities (② in Figure 5), and enhancing positive externalities provided by farmers and/or rural participants (③ in Figure 5) (Rhew, Kim, and Cho, 2020).

Question 3: Who would deserve to be ‘actors’?

Suggestion 3: From solely farmers to farmers and rural participants.

An eligibility concern is desired to be further discussed. The author suggests that in addition to ‘farmers’, such potential participants as rural residents may be eligible for the payment given that they are willing to carry out activities to be defined under Selective Public Benefit DPS.

Question 4: How to set up reference level?

Suggestion 4: Kind a step-by-step approach is to be desired.

Reference level and relevant requirements should be elaborated such that they can be of effect in terms of goal of the reform, and simultaneously be able to be adopted by participants.

CONCLUSION

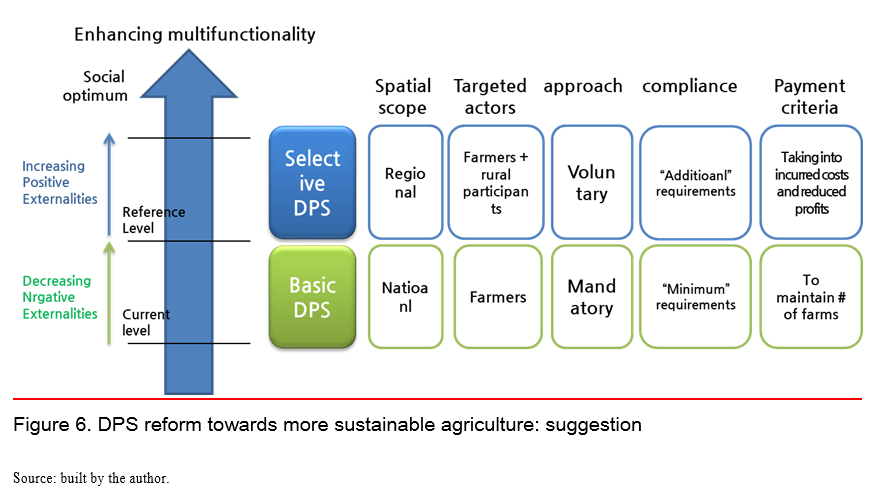

Like Neil Armstong mentioned, the DPS reform in progress these days could be “one small step for DPS itself, one giant leap for Korean agriculture.” Nevertheless, the author believes that there are lots of concerns to be advanced. The author’s suggestion may be arguably summarized as presented in Figure 6.

Basic DPS is desired to meet the following. 1) It aims at minimizing negative externalities, and at the same time, providing income safety net for participating farmers. 2) The components of the scheme, e.g. payment rate, compliance and so on, should be applied at the national level, and needs to be as uniform as possible. 3) A principle of “broad and shallow” is to be considered when setting up a reference level such that farmers can adopt them without radically and rapidly converting their “familiar” farming practices (“Rome was not built in a day.”). 4) Within budget constraint, the amount of total payment needs to be increased along with getting stricter compliance requirements.

More importantly, the Selective DPS should be placed at the center of overall the reformed scheme in the long run. The reason comes from that the ultimate goal of the reform is at guaranteeing sustainability of agriculture in Korea via strengthening multifunctionality, and that anticipated outcomes of Selective DPS, increasing positive externalities provided by more participants, is closer to that end. Selective DPS may well meet the following conditions: 1) It aims at satisfying diverse and dynamic societal demand mainly by providing more positive externalities; 2) The components of the scheme need to be, unlike those of Basic DPS, regional-contextual specific. For example, wider range of people, not necessarily farmers, may be allowed to join. Also, priority of functions to be conducted at the regional/local level could be differentiated. 3) Most activities under the Selective DPS are likely to be more challenging than those under the Basic DPS, in that they require more efforts and should be fulfilled in a more conscious and purposeful way. That is, without appropriate remuneration, the expected goal may not be reached. 4) In that sense, voluntary participation, for instance in forms of contract, is better than compulsory one.

APPENDIX 1: CHANGING SOCIETAL DEMAND ON AGRICULTURE IN KOREA

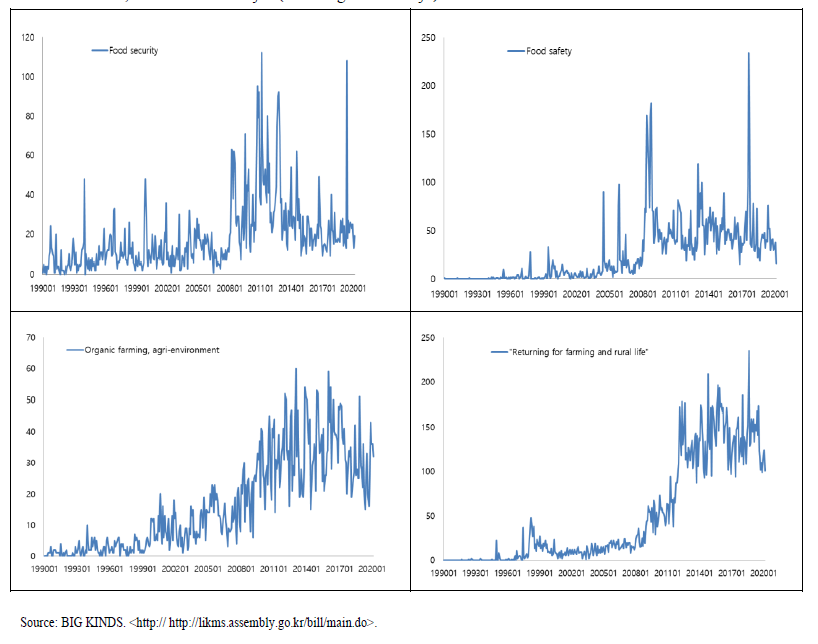

The Societal demand on agriculture in Korea has been dynamically changed, as can be shown in the snapshot below. Guided by Kim (2018), data withdrawn from BIG KINDS, integrated database for most major mass media in Korea, with specific and relevant keywords from 1990 through present are analyzed to disclose the changing pattern.

Not surprisingly, such multifunctionality as food security has gotten attention steadily over the period. A spike during the mid-2000s was due to skyrocketing grain price, a.k.a. agflation. No sufficient attention has been paid to other functions including food safety and organic farming/agri-environment until the early 2000s. Changes in social cognition, legislation and institution have been believed to invoke the change. More recently, the public has become more interested in negative externalities represented by livestock odors, and another lifestyle (kind of good old days).

REFERENCES

Big Kinds https://www.kinds.or.kr/> (Date of access: Jan-24-2020)

Bill Information http://likms.assembly.go.kr/bill/main.do> (Date of access: Dec-20-2019)

Kang, M.Y. 2017. “Agricultural Policy Reform Centering on Direct Payments Scheme and Restructuring Budget System.” A paper presented at Agricultural Policy Reform Centering on Direct Payments Scheme Seminar, Seoul, Sep. 14. 2017.

Kim, J.T. 2018. “Content and Evaluation of Agricultural and Rural Studies in Comparison with Social Cognition: Focusing on Text Mining Analysis.” Journal of Rural Society, 28(1): 65-103.

Kim, T.H., S.W., Kim, J.I., Kim and J.Y., Park.『A Study on Enhancing the Direct Payment Schemes Based on Multi-Faceted Evaluation(Year 2 of 2) 』. KREI.

Kim, T.Y., J.B. Im and J.H., Lee 2017. “Public Benefit-type Direct Payments Scheme: Raison d'être for Agriculture.” GSnJ Focus No. 234, GSnJ Institute.

Lee, J.H. and Y., Sagong. 2011. “Is Farm-based Income Support Scheme Legitimate and Feasible?” GSnJ Focus No. 119, GSnJ Institute.

Lee, J.H. 2013. “CCP: An Alternative to Paddy Rice and FTA Direct Payments.” GSnJ Focus No. 161, GSnJ Institute.

_______. 2017. “CCP: An Alternative against Deteriorated Price Conditions.” GSnJ Focus No. 233, GSnJ Institute.

_______. 2019. “Public Benefit-type Direct Payments Scheme: Expectations and Concerns.” GSnJ Focus No. 265, GSnJ Institute.

NABO (National Assembly Budget Office). 2019.『An Analysis of Debates on Public Benefit-type DPS reform』. NABO.

Park, J.K., N.W., Oh, C.H., Rhew, J.I., Kim and .J.Y., Park. 2016.『A Study on Current DPS Situation and Suggestions for Development』. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Presidential Commission on Policy Planning. 2018.『Agricultural Reform: Directions and Strategies』. PCPP.

Rhew, C.H., W.J., Cho, and S.W., Kim. 2018.『The Policy Agenda and Direction for Enhancing Multifunctionality in Agriculture』. KREI.

Rhew. C.H., S.S., Kim, and W.J. Cho. 2020. “Towards Sustainable Agriculture in Korea: Theoretical Backgrounds and Practical Challenges.” Korean Journal of Organic Agriculture, Volume 28, Number 1: 1-30.

[1] A huge reduction of DPS budget in 2019 is largely due to a sharp-cut-out of VDPS. The amount of VDPS to be actually allocated to farmers are subject to a legally-determined formula as follows: VDPS(/80 kg) = Max [(Target Price(/80 kg) –Harvesting-season Spot Price(/80 kg)) ⅹ 0.85 – FDPS(/80 kg), 0]. Once, the criterion is met, actual payment is made in the following year. Harvesting-season spot price in 2019 was equal to 193,447 KRW(165.3 USD)/80kg, higher than Target Price of 188,000 KRW(156.6 USD)/80kg, which results in substantial decrease of the amounts of VDPS to be paid.

[2] They, however, are not mutually exclusive.

[3] CCP has been replaced by Price Loss Coverage (PLC) with the introduction of the 2014 Farm Bill.

[4] It mainly includes FDPS, UDPS, NDPS, ODPS and LDPS.

[5] Even if a farmer is eligible for DPS payments, (s)he may not be automatically enrolled and get paid. Following the predetermined procedure, (s)he is supposed to hand in documents to prove (s)he is entitled. This procedure is introduced to prevent somewhat illegal persons, e.g. absentee landlords, from receiving the payments.

[6] For more detailed reasoning, see Rhew, Kim, and Cho (2020).

[7] For societal demand change on agriculture in Korea, see .

Trends and Discussions on Direct Payment Schemes Reform in Korea: Issues and Suggestions

ABSTRACT

Direct Payment Schemes (DPS) has played a central role in Korean agriculture, but not free from caveats and criticism. Against those problems, DPS reform has been in active progress these days. The author attempts to provide suggestions as follows. 1) The goal of the reform should be enhancing sustainability and multifunctionality rather than income support. 2) The scope of multifunctionality and eligible participants should be widened. 3) In the long run, the Selective DPS should be placed at the center of the new scheme.

BACKGROUNDS

Currently, nine kinds of Direct Payment Schemes (hereinafter DPS) have been implemented under the ACT ON PRESERVING AGRICULTURAL INCOME and the SPECIAL ACT ON ASSISTANCE TO FARMERS, FISHERMEN, ETC. FOLLOWING THE CONCLUSION OF FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS (Table 1).

Table 1. DPS status as of 2019

DPS

Main Purpose

Fixed DPS for Paddy Rice (FDPS)

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of farm income increment and enhancing multifunctionality.

Variable DPS for Paddy Rice (VDPS)

Increasing rice farm income by compensating income loss given a certain criterion is met.

Fixed DPS for Upland Crops (UDPS)

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of upland farm income increment.

Naturally Constrained Area DPS (NDPS)

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of maintaining production capacity in naturally constrained (less favored) areas.

Organic Farming DPS (ODPS)

Providing per hectare payments in pursuit of expansion of organic farming by compensating income loss at the early conversion stage.

Landscape Enhancement DPS

(LDPS)

Providing per hectare payments for planting landscape-enhancing crops in pursuit of landscape management.

Generation Renewal DPS (GDPS)

Providing payments to promote generation renewal.

FTA-relevant Compensation DPS

(FCDPS)

Compensating a part of income loss caused by FTA implementation.

FTA-relevant-exiting Compensation DPS (FEDPS)

Enabling smooth and voluntary exiting of farms caused by FTA implementation.

Source: NABO (2019).

The DPS budget has increased steadily since its introduction to account for 17% of the total agricultural budget in 2018 (2.4 trillion KRW or about 2.0 billion USD) (Table 2). That is, DPS has played a central role in terms of farm management stabilization and income support. In particular, Fixed DPS for Paddy Rice (FDPS) is the single largest and most important one, accounting for 66% of the 2019 DPS budget.[1]

Table 2. DPS budget during 2016-2019 Unit: 100 mil. KRW, %

2016

2017

2018

2019

amount

share

amount

share

amount

share

amount

share

DPS Total

21,124

100.0

28,543

100.0

24,390

100.0

16,122

100.0

FDPS

8,240

39.0

8,160

28.6

8,090

33.2

8,028

49.8

VDPS

7,193

34.1

14,900

52.2

10,800

44.6

2,533

15.7

GDPS

573

2.7

545

1.9

497

2.0

472

2.9

NDPS

395

1.9

472

1.7

506

2.1

546

3.4

UDPS

2,118

10.0

1,906

6.7

1,937

7.9

2,078

12.9

LDPS

136

0.6

116

0.4

93

0.4

84

0.5

ODPS

437

2.1

411

1.4

435

1.8

381

2.4

FCDPS

1,005

4.8

1,005

3.5

1,005

4.1

1,000

6.2

FEDPS

1,027

4.9

1,027

3.6

1,027

4.2

1,000

6.2

MAFRA Total

143,681

-

144,887

-

144,996

-

146,596

-

Source: Modified from Park et al. (2016).

Nevertheless, criticism regarding limitations inherent in current DPS continues to be raised, and there are number of claims requiring that reforming the current system is imperative. The main problems to be addressed are as follows. 1) Financial resource allocation: DPS budgets are largely concentrated on paddy rice sector causing inequality concern; 2) Coupling: a current VDPS potentially stimulated over-production, 3) Inconsistency and/or conflicts between objectives of individual DPS, e.g. those of FDPS/VDPS and GDPS. 4) In spite of rhetorical emphasis on multifunctionality of agriculture, actual and empirical provision of such functions is in question.

This article aims at outlining recent discussions regarding DPS reform and making suggestions with a particular focus on strengthening multifunctionality of agriculture.

Current discussions on DPS reform in Korea

In the meantime, the DPS proposals have shared Basic and Selective Payment Schemes architecture. However, the detailed structure and features vary across proposals.[2]

Some have put emphasis on reforming, among others, of paddy rice-related DPS including FDPS and VDPS (e.g. Lee and Sagong 2011; Lee 2013, 2017; Park et al. 2016). Proponents of this position argue that the current DPS should be reformed in such a way that structural overproduction of rice as well as income support inequality concerns can be alleviated. On the other hand, some argue that the multifunctionality of agriculture should be expanded and fulfilled to meet changing societal demands and, at the same time, guaranteeing the sustainability of agriculture (e.g. Kim, Im and Lee 2017; Kang 2017; Lee 2019; Rhew, Cho and Kim 2018; PCPP 2018). This position has paid more attention to what we call Selective DPS. Others argue that both positions matter and that they are to be balanced (e.g. Kim et al. 2017).

Standpoint 1: “Income support still matters.”

Lee and Sagong (2011) and Lee (2013) suggested that the current income support measures should be expanded to be effective as a policy instrument. The main goal is to extend the coverage of FCDPS payment to "all major commodities affected by market opening." They argued that the proposed scheme can be decoupled by setting up the base year cultivation area, and operating the VDPS separately. The suggested model was similar to the former Counter-Cyclical Payments (current Price Loss Coverage) in the U.S.[3] Lee (2017) further developed his previous idea to insist that current VDPS and FCDPS be integrated into so called CCP-type scheme and that the coverage of the new scheme should be widened.

Park et al. (2016) suggested the future orientation of DPS as follows (Figure 1). 1) The scheme may play a role for income support and stabilization, but other measures such as crop insurance and check-off need to be strengthened. 2) Payment criteria are desired to be switched from commodity to land-base in that all kinds of arable land matter regardless of what sorts of crops are being planted. 3) Management requirement and/or reference levels should be stricter to permit the reform to be more persuasive, especially for the public. 4) Mitigating structural over-supply of paddy rice via more equitable DPS resource allocation is also important.

Standpoint 2: “Income support matters, but more important is meeting societal demand”

Lim, Im and Lee (2017) and Lee (2019) argued that introducing new DPS remunerating specific activities generating environmental and ecological benefits with public good properties would contribute to social welfare increments. To that end, they insist that the current system[1] should consist of Basic DPS and purpose-specific DPS to better serve individual goals (Figure 2).

Kang (2017) argued that the future agricultural policy should be directed to “multifunctional agriculture for all citizens” and the budget should be correspondingly allocated. Along with this direction, she argued, that the current DPS also needs to be newly set up, say, such as Food Security Enhancement Program and DPS for Contribution by Agriculture (Table 3).

Table 3. DPS reform proposal by Kang (2017)

Type

Title

Example

Basic

Food Security Enhancement Program or Food Security DPS or Food Self-provision DPS

Selective

(topping-up)

DPS for Contribution by Agriculture or DPS for Societal Service by Agriculture or Multifunctional Agriculture DPS

Source: Kang (2017).

Presidential Commission on Policy Planning (PCPP 2018) handed in its own proposal (Figure 3) on the ground that DPS reform is a necessary prerequisite for agricultural policy paradigm shift. PCPP’s proposal regarding the reform direction as “from income support to remuneration for multifunctional agriculture and its benefits for the people.”

Standpoint 3: “Both matter. A newly balanced equilibrium should be sought.”

A proposal by Kim et al. (2017) centered on a couple of things (Figure 4). First, degree of relevance with multifunctionality and target should be placed as payment criteria. Second, based on the proposed criteria, a current Scheme may be reformed to Arable Land Management DPS (Basic Payment type) and Environment Enhancement for Agriculture and Rural Areas Scheme (selective/topping-up payment type), which is a way simpler than the current one.

Legislation in progress

Grounded on previously mentioned discussions, a legal proposal has been handed in September 9, 2019, which repealed the former ACT ON PRESERVING AGRICULTURAL INCOME. The new proposal, now in effect, is named ACT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF DIRECT PAYMENT SCHEME FOR ENHANCING PUBLIC FUNCTION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS. Its implementing ordinance also has been passed by Cabinet meeting in April 21, 2020. As a result, the new DPS will be in effect as of May 1, 2020.

Main features of the new scheme are as follows (Table 4). First, the purpose of the Act includes “Enhancement of multifunctionality out of agriculture and rural areas, and farmers’ income stabilization.” Second, the new DPS consists of Basic Public Benefit DPS and Selective Public Benefit DPS. The former again is comprised of Small Farmers’ Scheme (newly introduced) and Area-based Payment Scheme (similar with a current one except that a regressive per hectare payment formula is added). To be eligible for Small Farmers’ Scheme, any applicant shall meet all of 8 relevant requirements. An eligible applicant can, regardless of size of planted acres, receive about 1,000 USD annually, which is, on average, larger than his/her previous payment records by 2.8 times. Third, in total 17 mandatory requirements for applicants[1] to be eligible for the payments have been set up, which include maintaining shapes and functions of arable lands, proper use of pesticides and fertilizers, taking up multifunctionality-related education and so on. Additionally, restriction of planted acres may be implemented when necessary. Fourth, detailed descriptions regarding Selective Public Benefit DPS are yet to be provided. The proposal says that such things are to be included in its Enforcement Decree.

Table 4. An overview of Legal reform proposal (No. 2022404) as of Sep. 9, 2019

Current

Proposal

FDPS

Basic Payments

Scheme

UDPS

VDPS

NDPS

ODPS

Selective Payments

Scheme

ODPS(livestock)

LDPS

GDPS

GDPS

FCDPS

FCDPS

FEDPS

FEDPS

Source: Bill Information

Still a long way to go: Suggestions

In spite of enormous endeavors and efforts made so far, the DPS reform is not free from a number of challenges and caveats. In this sense, the author would like to make some suggestions.

Question 1: What should be an ultimate orientation point of the DPS reform?

Suggestion 1: Enhancing sustainability via multifunctionality, and income support as a stepping stone.

One of the largest debates on the legal proposal is whether it is appropriate to include income support as a manifest aim of DPS. The author believes that, in spite of its importance, income support may become a main goal of DPS itself and/or orientation of the reform. Enabling farmers’ to gain ‘sufficient’ level of income and thus allowing them to enjoy a decent quality of life cannot be too much emphasized. However, as long as we talk over the reform, addressing the farm income problem may as well be ‘necessary condition’ and ‘means’ of providing them an incentive such that they may play a role not only as ‘a producer of food and fiber’ but as ‘a manager of territory and environment.’[2]

Question 2: What functions should be contained in the multifunctionality?

Suggestion 2: Way wider than what have been conventionally defined in Korean agriculture.

Consensus on the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture is yet to be reached. The FRAMEWORK ACT ON AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES, RURAL COMMUNITY AND FOOD INDUSTRY, in its Article 3, provides a rough scope of multifunctionality of agriculture and rural areas, which is placed at the debate arena as well. Some argued that those functions directly or indirectly related with agricultural production may be included in the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture. Others insist that the scope may be widened such that rural territory and management and social safety net become a part of the scheme. Grounding on the concept and properties of multifunctionality of agriculture, the author is on the side of the latter. The author would like to substitute the scope of multifunctionality of agriculture in such a way presented in Figure 5. First, currently defined functions may be elaborated to better serve the ever changing societal demand (① in Figure 5).[3] For example, the newly fine-tuned terms may need to include not only “steady sellers” such as food security, but “new arrivals” such as coping with climate change, biodiversity, and animal welfare. Second, the scope may be further widened to explicitly aim at mitigating negative externalities stemming from agricultural activities (② in Figure 5), and enhancing positive externalities provided by farmers and/or rural participants (③ in Figure 5) (Rhew, Kim, and Cho, 2020).

Question 3: Who would deserve to be ‘actors’?

Suggestion 3: From solely farmers to farmers and rural participants.

An eligibility concern is desired to be further discussed. The author suggests that in addition to ‘farmers’, such potential participants as rural residents may be eligible for the payment given that they are willing to carry out activities to be defined under Selective Public Benefit DPS.

Question 4: How to set up reference level?

Suggestion 4: Kind a step-by-step approach is to be desired.

Reference level and relevant requirements should be elaborated such that they can be of effect in terms of goal of the reform, and simultaneously be able to be adopted by participants.

CONCLUSION

Like Neil Armstong mentioned, the DPS reform in progress these days could be “one small step for DPS itself, one giant leap for Korean agriculture.” Nevertheless, the author believes that there are lots of concerns to be advanced. The author’s suggestion may be arguably summarized as presented in Figure 6.

Basic DPS is desired to meet the following. 1) It aims at minimizing negative externalities, and at the same time, providing income safety net for participating farmers. 2) The components of the scheme, e.g. payment rate, compliance and so on, should be applied at the national level, and needs to be as uniform as possible. 3) A principle of “broad and shallow” is to be considered when setting up a reference level such that farmers can adopt them without radically and rapidly converting their “familiar” farming practices (“Rome was not built in a day.”). 4) Within budget constraint, the amount of total payment needs to be increased along with getting stricter compliance requirements.

More importantly, the Selective DPS should be placed at the center of overall the reformed scheme in the long run. The reason comes from that the ultimate goal of the reform is at guaranteeing sustainability of agriculture in Korea via strengthening multifunctionality, and that anticipated outcomes of Selective DPS, increasing positive externalities provided by more participants, is closer to that end. Selective DPS may well meet the following conditions: 1) It aims at satisfying diverse and dynamic societal demand mainly by providing more positive externalities; 2) The components of the scheme need to be, unlike those of Basic DPS, regional-contextual specific. For example, wider range of people, not necessarily farmers, may be allowed to join. Also, priority of functions to be conducted at the regional/local level could be differentiated. 3) Most activities under the Selective DPS are likely to be more challenging than those under the Basic DPS, in that they require more efforts and should be fulfilled in a more conscious and purposeful way. That is, without appropriate remuneration, the expected goal may not be reached. 4) In that sense, voluntary participation, for instance in forms of contract, is better than compulsory one.

APPENDIX 1: CHANGING SOCIETAL DEMAND ON AGRICULTURE IN KOREA

The Societal demand on agriculture in Korea has been dynamically changed, as can be shown in the snapshot below. Guided by Kim (2018), data withdrawn from BIG KINDS, integrated database for most major mass media in Korea, with specific and relevant keywords from 1990 through present are analyzed to disclose the changing pattern.

Not surprisingly, such multifunctionality as food security has gotten attention steadily over the period. A spike during the mid-2000s was due to skyrocketing grain price, a.k.a. agflation. No sufficient attention has been paid to other functions including food safety and organic farming/agri-environment until the early 2000s. Changes in social cognition, legislation and institution have been believed to invoke the change. More recently, the public has become more interested in negative externalities represented by livestock odors, and another lifestyle (kind of good old days).

REFERENCES

Big Kinds https://www.kinds.or.kr/> (Date of access: Jan-24-2020)

Bill Information http://likms.assembly.go.kr/bill/main.do> (Date of access: Dec-20-2019)

Kang, M.Y. 2017. “Agricultural Policy Reform Centering on Direct Payments Scheme and Restructuring Budget System.” A paper presented at Agricultural Policy Reform Centering on Direct Payments Scheme Seminar, Seoul, Sep. 14. 2017.

Kim, J.T. 2018. “Content and Evaluation of Agricultural and Rural Studies in Comparison with Social Cognition: Focusing on Text Mining Analysis.” Journal of Rural Society, 28(1): 65-103.

Kim, T.H., S.W., Kim, J.I., Kim and J.Y., Park.『A Study on Enhancing the Direct Payment Schemes Based on Multi-Faceted Evaluation(Year 2 of 2) 』. KREI.

Kim, T.Y., J.B. Im and J.H., Lee 2017. “Public Benefit-type Direct Payments Scheme: Raison d'être for Agriculture.” GSnJ Focus No. 234, GSnJ Institute.

Lee, J.H. and Y., Sagong. 2011. “Is Farm-based Income Support Scheme Legitimate and Feasible?” GSnJ Focus No. 119, GSnJ Institute.

Lee, J.H. 2013. “CCP: An Alternative to Paddy Rice and FTA Direct Payments.” GSnJ Focus No. 161, GSnJ Institute.

_______. 2017. “CCP: An Alternative against Deteriorated Price Conditions.” GSnJ Focus No. 233, GSnJ Institute.

_______. 2019. “Public Benefit-type Direct Payments Scheme: Expectations and Concerns.” GSnJ Focus No. 265, GSnJ Institute.

NABO (National Assembly Budget Office). 2019.『An Analysis of Debates on Public Benefit-type DPS reform』. NABO.

Park, J.K., N.W., Oh, C.H., Rhew, J.I., Kim and .J.Y., Park. 2016.『A Study on Current DPS Situation and Suggestions for Development』. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Presidential Commission on Policy Planning. 2018.『Agricultural Reform: Directions and Strategies』. PCPP.

Rhew, C.H., W.J., Cho, and S.W., Kim. 2018.『The Policy Agenda and Direction for Enhancing Multifunctionality in Agriculture』. KREI.

Rhew. C.H., S.S., Kim, and W.J. Cho. 2020. “Towards Sustainable Agriculture in Korea: Theoretical Backgrounds and Practical Challenges.” Korean Journal of Organic Agriculture, Volume 28, Number 1: 1-30.

[1] A huge reduction of DPS budget in 2019 is largely due to a sharp-cut-out of VDPS. The amount of VDPS to be actually allocated to farmers are subject to a legally-determined formula as follows: VDPS(/80 kg) = Max [(Target Price(/80 kg) –Harvesting-season Spot Price(/80 kg)) ⅹ 0.85 – FDPS(/80 kg), 0]. Once, the criterion is met, actual payment is made in the following year. Harvesting-season spot price in 2019 was equal to 193,447 KRW(165.3 USD)/80kg, higher than Target Price of 188,000 KRW(156.6 USD)/80kg, which results in substantial decrease of the amounts of VDPS to be paid.

[2] They, however, are not mutually exclusive.

[3] CCP has been replaced by Price Loss Coverage (PLC) with the introduction of the 2014 Farm Bill.

[4] It mainly includes FDPS, UDPS, NDPS, ODPS and LDPS.

[5] Even if a farmer is eligible for DPS payments, (s)he may not be automatically enrolled and get paid. Following the predetermined procedure, (s)he is supposed to hand in documents to prove (s)he is entitled. This procedure is introduced to prevent somewhat illegal persons, e.g. absentee landlords, from receiving the payments.

[6] For more detailed reasoning, see Rhew, Kim, and Cho (2020).

[7] For societal demand change on agriculture in Korea, see .