ABSTRACT

Accessing forest economic, social and environmental benefits is crucial for rural development, particularly in developing countries. Conservation and the sustainability of utilization are existential to the future availability of these resources. There is a relationship between utilization and conservation in addition to the inherent conflict. In Thailand, utilization of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) has a significant beneficial impact on household incomes and general livelihoods. Implementing community forest management (CFM) strategies not only bolsters forest economics but also increases the level of people’s participation in forest conservation efforts. Policies and strategies that facilitate CFM can further support both the economic and conservation objectives and lead Thailand toward sustainable forest management. Improving the potential for utilization in community forests should be considered to promote collaboration by local residents to conserve forest resources.

Keywords: Forest economics, conservation, rural development, community forest, non-timber forest products

INTRODUCTION

Thailand is a remarkably bio-diverse country as 8% of all global plant species, over 15,000 species, can be found in the country (Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning, 2009). Forest resources provide provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural ecosystem services (Millennium, 2005) and are vital to supporting and enhancing the quality of life of those who reside near natural forest reserve areas.

Forest biodiversity is economically beneficial to those in remote areas as it provides resources for household utilization or to sell in local markets to augment household incomes. Nowadays, forest products provide value for individual households as well as benefit general forest economics as worldwide it is estimated that the “value of biodiversity in maintaining commercial forest productivity” has been estimated to be US$166 billion to US$490 billion per year (Liang et al., 2016).

Any product or service other than timber that is produced by a forest such as fruit, nuts, vegetables, fish and game, medicinal plants, resins, essences, barks and fibres such as bamboo, rattans, and a host of other palms and grasses are considered to be a non-timber forest product (NTFP) (Center for International Forestry Research, 2008). In Thailand, roughly 23 million people live near national forest reserve areas which supply the NTFPs that help to satisfy basic needs of residents in rural communities (Witchawutipong, 2005).

NTFPs in Thailand are utilized in myriad ways to support the livelihood and economy of households. NTFPs provide food (edible plants, honey and insects, small animals, mushrooms) and medicines and are a source of fuelwood, fiber, ornamental plants and extractives (e.g., resins, gums, oils, waxes, and chemicals). The utilization of NTFPs is crucial to rural development of forest economics in Thailand.

The Thai government’s promulgation of the Community Forest Act 2019 authorized, among other things, local forest management decision-making. It recognized that community forest management (CFM) plays an important role in rural development with long-term economic, social, and environmental benefits inuring to local communities. Harvesting NTFPs for household utilization is permitted as it is for commercial purposes so long as it is done in a balanced and sustainable manner that does not adversely impact the environment or the community forest ecosystem.

However, utilization and conservation efforts often conflict which raises the question of how to manage forest resources to appease both objectives. This article will examine forest economics, conservation, and NTFP utilization in Thailand community forests and explore the possibility that utilizing NTFPs can not only improve rural livelihoods but can also foster sustainable management of local forests.

TRANSITION OF THAILAND’S FORESTS

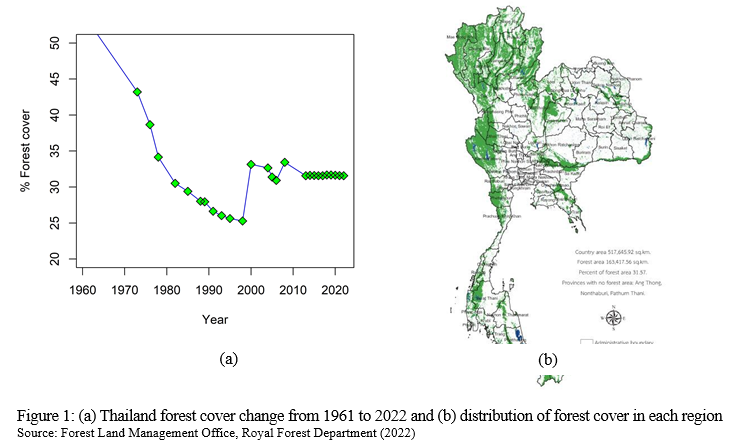

Thailand is one of the most bio-diverse countries in Southeast Asia and one of the 20 most bio-diverse countries in the world (The Swiftest, 2022). Forests cover 31.57% of the country with 63.53% of the northern, 59% of the western and 24.32% of the southern Thailand regions covered by forests (Royal Forest Department, 2022). The primary forest types are deciduous (mixed deciduous and dry dipterocarp forests) comprising 18.26% of the country’s forests. Other types include dry evergreen (4.30%), moist evergreen (3.68%), and montane forests (3.38%) (Royal Forest Department, 2019).

Historically, illegal logging and the demand for agricultural land have significantly and detrimentally impacted Thailand’s forests (Thai Forestry Sector Master Plan, 1993). Most notably, they have had wide-reaching and adverse effects on the economy, the environment, and the local residents. In 1961, forests covered 53.33% of the country’s total land area (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). In 1973, the forest area was 43.21%; in 1998 it was 25.28%, less than half of what it was in 1961 (Royal Forest Department, 2022). After 2000, technological advancements provided for more accurate analysis of forest coverage and a re-assessment of deforestation rates. Prior thereto, LANDSAT-5 imageries of a 1:200,000 scale were produced and assessed. Due to an improvement in scale to 1:50,000 and a modified method of calculation, new forest area standards were established (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). This expanded the detectable areas to include smaller, previously inestimable forest areas. Even though the Thai government imposed a nationwide logging ban in natural forests in 1989, thereby elevating the focus of forest management on local participation, promoting ecotourism and a greater understanding of NTFP utilization behaviors and impacts, Thailand is still facing issues that are having an adverse impact on forest resources and livelihoods.

Despite governmental efforts, no less than 1,442 plants have been classified as endangered species in the IUCN Red List (Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, 2017). Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (2020) reported that three plant species are extinct in nature while 999 species are classified as threatened; 647 species as Vulnerable (VU), 259 species as Endangered (EN) and 93 species as Critically Endangered (CR). Climate change, encroachment, fires, and land development all impact forest biodiversity and contribute to biodiversity loss. Thus, discussions of how to balance forest conservation with sustainable management to allow for beneficial utilization remain salient and ongoing.

STRATEGIES AND POLICIES

Pursuant to the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037), Thailand has committed to increase its green area cover to 55% with 35% being classified as natural forests, 15% as forest areas for utilization, and 5% for green areas or stands of trees outside forests. In addition, Thailand’s 1985 National Forest Policy, which was modified in 2019, reiterated Thailand’s goal of maintaining at least 40% of the country’s total area as forests, 25% for conservation forests and 15% for economic forests. Strategies to achieve these goals focused on forest management, forest product utilization and forest services and industry (Royal Forest Department, 2021). This indicates a commitment to a combination of policies and strategies aimed at balancing forest economics and conservation to ensure that economic benefits from forests through conservation can be realized.

Increasing forest areas and achieving these goals is challenging and involves numerous stakeholders, namely, governmental agencies, the private sector, and a high level of participation by community residents. Currently, three organizations under the Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment (MONRE) are primarily responsible for the country’s forest resources. The Royal Forest Department (RFD) manages forest reserves that are outside protected areas, the Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) manages protected areas such as national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, arboretums, and forest parks, while the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMC) has authority over the mangrove resources.

Thailand has promulgated several acts of legislation which address forest resource management such as the Forest Act B.E. 2484 (1941), the National Reserved Forest Act B.E. 2507 (1964), the Forest Plantation Act B.E. 2535 (1992), the Chainsaw Act B.E. 2545 (2002), the National Park Act B.E. 2562 (2019), the Wild Animal Conservation and Protection Act, B.E. 2562 (2019) and the Community Forest Act B.E. 2562 (2019). In addition, it has adopted policies and strategies in pursuit of forest management that lead to sustainable availability of economic, social, and environmental benefits.

The present forest coverage approximates 32% of the country’s area. As the RFD aims to respond to the 20-Year National Strategic Plan and achieve the 55% green area cover goal, there is clearly work to be done. Forest areas decline and destruction of forest resources is not higher than in previous years, and forest areas are not likely to decline further. Policies have been adopted to promote the establishment of 15,000 community forests encompassing 1.6 million ha, that manage forest land in a systematic and fair manner, and promote the restoration of degraded forests, increase economic forest areas, and promote and develop green spaces in cities and rural areas. Moreover, there have been advancements in the management of forest resources, such as improved technology, cooperation with foreign administrations, permission policies, and wood and wood product certification (Royal Forest Department, 2021).

COMMUNITY FOREST MANAGEMENT

The concept of community forest management (CFM) has been widely accepted and implemented in many developing countries, including Thailand. It has been adopted as a very effective approach to restoring degraded forests, helping to fulfill the needs of local residents, increasing income and benefiting the poor. Community forest management is also generally recognized as an effective sustainable forest management tool. In Thailand, the RFD has promoted CFM since 1987 (Royal Forest Department, 2014). Evidence of the acceptance and expansion of CFM is reflected in the widespread level of participation throughout the country.

Thammanu et al. (2021) demonstrated a positive correlation between income from forests and CFM (people’s participation, community forest regulations, perception and understanding, and benefit sharing). This suggests that CFM can create income opportunities and promote development in community forests. That study further found that utilization of community forest resources tends to improve the economy of lower income households. Therefore, CFM can lead to the support of the livelihoods of the poor.

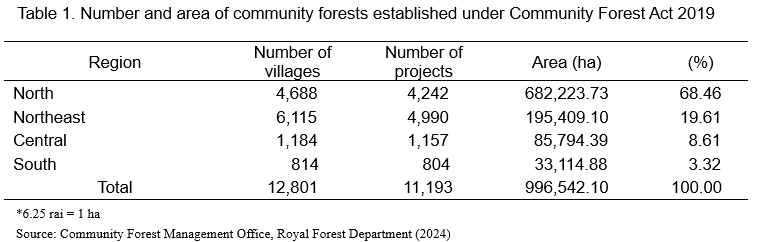

In accordance with the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037), the RFD aims to establish 10 million rai (1.6 million ha) of community forests in 15,000 villages. As of 31 May, 2024, 11,193 community forest projects in 12,801 villages encompassing approximately 1 million ha or 6% of the country’s total forest area have been implemented (Royal Forest Department, 2024). The proliferation of community forest projects after the Community Forest Act 2019 has resulted in the noteworthy expansion of forest areas in Thailand (Table 1). Moreover, the Community Forest Act 2019 addresses and supports forest economics as well as community conservation efforts through enforceable legislation and regulations.

UTILIZATION OF NTFPs IN A COMMUNITY FOREST

Worldwide, bio-diverse forest resources are crucial to the livelihoods of 1.6 billion people, or more than 25% of the world’s population, who live in proximity to forests (The World Bank, 2001). These resources, including NTFPs, contribute to basic needs and supplement income especially of lower income households in developing countries. CFM can support crucial NTFP sustainability. NTFPs sourced from forest ecosystems are crucial contributors to household incomes and their general well-being. Dependence on NTFPs by lower income households to support their livelihoods has been reported in many parts of the world.

Increased trade in NTFPs has been shown to slow deforestation by increasing the economic value of forest biodiversity; effective local institutional management can reduce forest degradation (Ostrom et al., 1994; Shanley et al., 2002; Ostrom, 2005). In addition, the responsible use of NTFPs under CFM can lead to successful forest management that is beneficial to human well-being and preservation of ecosystem services thereby improving rural livelihoods and supporting conservation efforts (Jumbe & Angelsen, 2007; Coulibaly-Lingani et al., 2011; Soe & Youn, 2019b). NTFPs provide food, serve other daily functions, and generate income to people in nearby communities. Many case studies in developing countries have shown that NTFPs can contribute economic benefits to households. For example, in a study conducted in Congo, it was estimated that 23.3% of total household income derived from NTFPs (Mondo et al., 2024), in Nigeria it was 20-60% (Suleiman et al., 2017) and in Myanmar, NTFPs accounted for 37% of the total household income (Soe & Youn, 2019a). A study in Bangladesh reported that NTFPs contributed 56.9% of total annual household incomes (Rahman et al., 2021).

NTFPs are used for daily household consumption and are often traded in local markets to provide and supplement household income. Commonly, NTFPs utilized in Thailand communities include edible plants, wild fruits, medicinal plants, fuelwood, mushrooms, insects, wild animals, fibers, and extractives. The average annual income from selling NTFPs in local markets in Thailand is estimated to be over US$25,000 per village (Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning, 2004) and over US$2 billion nationwide (International Tropical Timber Organization, 2006).

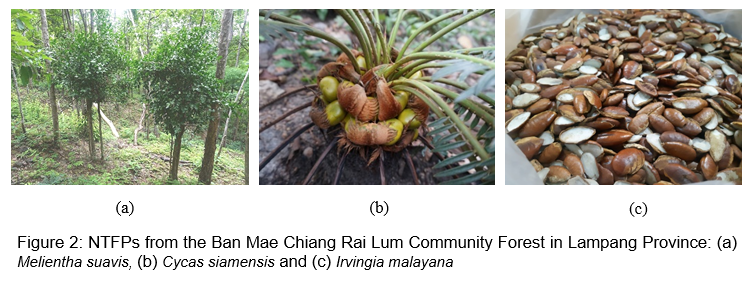

According to Thammanu et al. (2021), the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest in Lampang province in the north of Thailand, yielded a net return of approximately THB1,871,117.30 (US$60,358.62) from NTFPs to the community, an average of THB7,060.82 (US$227.77) per year/household. When comparing income to the cost of collection, mushrooms provided the highest net return (73.47%), followed by wild fruits (14.93%), small animals (6.04%), and edible plants (3.18%).

Many tree species provide foods such as Melientha suavis, Irvingia malayana, Adenia viridiflora, Cycas siamensis, Phyllanthus emblica, Trevesia plamata. Trees such as Elephantopus scaber and Eurycoma longifolia have medicinal value. In addition, some tree species are sourced as fuelwood such as Shorea spp. and some species such as Bauhinia strychnifolia as fiber. Moreover, some non-tree species were food sources such as mushrooms (Amanita spp., Astraeus spp., Cantharellus sp., Russula sp., Termitomyces spp.), insects (Oecophylla smaragdina), honey (Apis dorsata), and small animals (Kaloula pulchra, Glyphoglossus molossus, Leiolepis belliana).

Thailand has a very diverse composition of species, especially those used for medicines and foods. Previous research has found that NTFP utilization of some plant species was low when compared with their availability. This indicates greater potential for NTFP utilization and its concomitant benefits. An inventory of the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest yielded a total of 18,567 plants that encompassed 197 species, 144 genera, and 62 plant families. Of these, 160 plant species have been classified as having medicinal uses, 89 are used as food, 37 as extractive products, 32 as fuelwood, and 12 as fibers.

Only 6.35% of the total household income is attributed to the collection and utilization of NTFPs from the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest, which primarily came from food and herb NTFPs. Compared to other case studies in developing countries, as indicated above (Congo 23.3%, Nigeria 20-60%, Myanmar 37% and Bangladesh 56.9%), this percentage of income was low. This can be attributed to a lack of technology, insufficient transfer of practical local wisdom or even a financial calculus as harvesting forest products may not be as economically beneficial for a household as other employment away from the home. Regardless, the relatively low level of harvesting reflects that a potential for greater income exists, and enhancement of forest biodiversity to provide a larger and ongoing supply of NTFPs is needed.

Section 50 of Thailand’s community forest law increases the emphasis on the collection of forest products for use (Thai government, 2019). In conformity with the relevant laws, a community forest area is divided into areas for conservation and utilization. The utilization area does not exceed 40% of the total area or it can be designated as an area for conservation in its entirety. This facilitates the establishment of community enterprises to develop products for sale. Despite this favorable framework, a lack of funding, knowledge and technology to develop products to market and sell remain obstacles to achieving economic sustainability. The government, universities, the business sector and the public in general all need to cooperate to overcome these hurdles.

LINKING FOREST ECONOMICS AND CONSERVATION TO RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Utilization of forest resources not only affects species diversity, but also has a long-term impact on ecosystem health and resiliency (Rowe, 2009). Consequently, the dynamics and conflicts in the relationship between forest utilization and biodiversity conservation can affect people’s livelihoods. Effectively implemented forest management can help to safeguard species diversity and the ecosystem services it provides as well as improve rural livelihoods.

Previous research has shown that the benefits attained from forests were closely associated with the level of participation in conservation. In a Thailand study, people who were NTFP dependent were likely to participate more in CFM (Thammanu et al., 2021). This finding is consistent with studies in other countries wherein income derived from NTFPs is positively correlated with participation in forest management. In Cambodia, incentives from extraction of NTFPs motivate local people to join in forest protection and to contribute money for forest patrols (Chou, 2018). In Sumatra, Indonesia, Harbia et al. (2018) found that harvesting rattan can simultaneously benefit local livelihoods and forest conservation. These studies generally support the proposition that economic benefits of NTFPs can incentivize participation while also supporting forest conservation and rural development. This information can inform effective forest management strategies and policies toward sustainable forest management.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on this discussion, the following observations about improving forest management to develop living conditions and conserve the biodiversity of community forests in Thailand can be made:

- The community forest’s remarkable diversity plays an important role in providing NTFPs that can support rural livelihoods and conservation efforts simultaneously. NTFP utilization in the community forest tends to improve the economic condition of lower income households.

2) Receiving NTFP income leads to contributing to, and participating in, the management of a community forest. Involvement has a positive impact on management effectiveness which can create opportunities for more income. A relationship exists between NTFP dependence and participation for the benefit of all; this is a relationship that should be demonstrated and used to incentivize participation.

3) Realizing the potential of community forests in Thailand is an important driver in promoting involvement by local residents in local forest activities to conserve and preserve forest resources. A greater emphasis should be placed on promoting the generation of income from collecting NTFPs to the community. Value added development of NTFPs to increase their potential should also be considered. The government sector should provide regulatory, financial, educational and technological support to facilitate the implementation. The private sector and businesses should be recruited to promote community enterprises to compete in the market. Having a secure income will incentivize conservation of forest resources and assist in the overall rural development that will inevitably accrue from sustainable forest management.

4) CFM is an important tool in the pursuit of increasing green and forest areas in accordance with the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037) and of the National Forest Policy while simultaneously addressing economic and conservation concerns. The Thai government should promulgate legislative and other policies to support the utilization of biodiversity through encouraging people’s participation, particularly of NTFP utilization. Doing so will not only address deforestation and forest degradation, but will also secure NTFPs as a source of income, enhance the quality of life and have a beneficial impact on the environment.

REFERENCES

Chou, P. (2018). The role of non-timber forest products in creating incentives for forest conservation: A case study of Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary. Cambodia, Resources, 7(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7030041.

Center for International Forestry Research. (2008). Non-timber forest products. Available online: https://www2.cifor.org/ntfpcd/, April 1, 2024.

Coulibaly-Lingani, P., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., & Oden, P.-C. (2011). Factors influencing people’s participation in the forest management program in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Forest Policy and Economics, 13(4), 292-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.02.005.

Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. (2017). Threatened plants in Thailand. Omega Printing Co., Ltd., Bangkok, p 224.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2009). Thailand forestry outlook study. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/am617e/am617e00.pdf

Harbia, J., Erbaugh, J.T., Sidiq, M., Haasler, B., & Nurrochmat, D.R. (2018). Making a bridge between livelihoods and forest conservation: lessons from non timber forest products’ utilization in South Sumatera, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 94, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.05.011.

International Tropical Timber Organization. (2006). Achieving the ITTO objective 2000 and sustainable forest management in Thailand. Available online: https://www.itto.int/direct/topics/topics_pdf_download/topics_id=31270000&no=1&disp=inline, December 20, 2023

Jumbe, C.B.L., & Angelsen, A. (2007). Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecological Economics, 62(3-4), 661-672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.08.008.

Liang, J., Crowther, T.W., Picard, N., Wiser, S., Zhou, M., Alberti, G., Schulze, E.-D., & et al. (2016). Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science, 354(6309), aaf8957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8957.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. World Resource Institute, Washington DC.

Mondo, J.M., Chuma, G.B., Muke, M.B., Fadhidi, B.B., Kihye, J.B., Sibomana, C.I., Kazamwali, L.M.. & et al. (2024). Utilization of non-timber forest products as alternative sources of food and income in the highland regions of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Trees, Forests and People, 16 (2024) 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100547.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2004). Thailand environment monitor series. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2009). Thailand: national report on the implementation of the convention on biological diversity. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2020). The status of biodiversity in Thailand. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, games and common-pool resources. University of Michigan Press, Michigan.

Rahman, M.H., Roy, B., & Islam, M.S. (2021). Contribution of non-timber forest products to the livelihoods of the forest-dependent communities around the Khadimnagar National Park in northeastern Bangladesh. Regional Sustainability, 2(3), 280-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2021.11.001.

Rowe, R.J. (2009). Environmental and geometric drivers of small mammal diversity along elevational gradients in Utah. Ecography, 32(3), 411-422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05538.x.

Royal Forest Department. (2014). Implementation guidelines for communit forest projects of the Royal Forest Department. Community Forest Management Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2019). Executive summary. Forest Land Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2021). The Royal Forest Department’s 20-year (2018-2037) implementation plan. Planning and Information Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2022). Forestry Statistics Data 2022. Information Technology and Communication Center. Available online: http://forestinfo.forest.go.th/Content.aspx?id=10400, November 10, 2023.

Royal Forest Department. (2024). Information from Community Forest Act 2019. Community Management Office. Available online: https://www.forest.go.th/community-extension/, June 7, 2024.

Shanley, P., Luz, L., & Swingland, I.R. (2002). The faint promise of a distant market: a survey of Belém’s trade in non-timber forest products. Biodiversity & Conservation, 11, 615-636. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015556508925.

Soe, K.T., & Youn, Y. (2019a). Livelihood Dependency on Non-Timber Forest Products: Implications for REDD+. Forests, 10(5), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10050427.

Soe, K.T., & Youn, Y. (2019b). Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: a case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. Forest Policy and Economics, 100, 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.11.009.

Suleiman, M.S., Wasonga, V.O., Mbau J.S., Suleiman, A., & Elhadi, Y.A. (2017). Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecological Process, 6(23). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0090-8.

Thai Forestry Sector Master Plan. (1993). Thai forestry sector master plan vol. 5, subsectoral plan for people and forestry environment. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, and FINNIDA, Bangkok.

Thai Government. (2019). Community Forest Act, B.E. 2562; Royal Thai Government Gazette: Bangkok, Thailand.

Thammanu, S., Han, H., Ekanayake, E.M.B.P., Jung, Y., & Chung, J. (2021). Sustainability, 13(23), 13474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313474.

Thammanu, S., Han, H., Marod, D., Zang, L., Jung, Y., Soe, K.T., Onprom, S., & Chung, J. (2020). Forest Science and Technology, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2020.1862712.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are grateful to the Royal Forest Department (RFD) for providing the opportunity to pursue this research and for facilitating the preparation of this writing. Publication would otherwise not be possible without the assistance of RFD’s staff. All of its assistance and support are greatly appreciated.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Linking Forest Economics and Conservation to Rural Development in Community Forests of Thailand

ABSTRACT

Accessing forest economic, social and environmental benefits is crucial for rural development, particularly in developing countries. Conservation and the sustainability of utilization are existential to the future availability of these resources. There is a relationship between utilization and conservation in addition to the inherent conflict. In Thailand, utilization of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) has a significant beneficial impact on household incomes and general livelihoods. Implementing community forest management (CFM) strategies not only bolsters forest economics but also increases the level of people’s participation in forest conservation efforts. Policies and strategies that facilitate CFM can further support both the economic and conservation objectives and lead Thailand toward sustainable forest management. Improving the potential for utilization in community forests should be considered to promote collaboration by local residents to conserve forest resources.

Keywords: Forest economics, conservation, rural development, community forest, non-timber forest products

INTRODUCTION

Thailand is a remarkably bio-diverse country as 8% of all global plant species, over 15,000 species, can be found in the country (Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning, 2009). Forest resources provide provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural ecosystem services (Millennium, 2005) and are vital to supporting and enhancing the quality of life of those who reside near natural forest reserve areas.

Forest biodiversity is economically beneficial to those in remote areas as it provides resources for household utilization or to sell in local markets to augment household incomes. Nowadays, forest products provide value for individual households as well as benefit general forest economics as worldwide it is estimated that the “value of biodiversity in maintaining commercial forest productivity” has been estimated to be US$166 billion to US$490 billion per year (Liang et al., 2016).

Any product or service other than timber that is produced by a forest such as fruit, nuts, vegetables, fish and game, medicinal plants, resins, essences, barks and fibres such as bamboo, rattans, and a host of other palms and grasses are considered to be a non-timber forest product (NTFP) (Center for International Forestry Research, 2008). In Thailand, roughly 23 million people live near national forest reserve areas which supply the NTFPs that help to satisfy basic needs of residents in rural communities (Witchawutipong, 2005).

NTFPs in Thailand are utilized in myriad ways to support the livelihood and economy of households. NTFPs provide food (edible plants, honey and insects, small animals, mushrooms) and medicines and are a source of fuelwood, fiber, ornamental plants and extractives (e.g., resins, gums, oils, waxes, and chemicals). The utilization of NTFPs is crucial to rural development of forest economics in Thailand.

The Thai government’s promulgation of the Community Forest Act 2019 authorized, among other things, local forest management decision-making. It recognized that community forest management (CFM) plays an important role in rural development with long-term economic, social, and environmental benefits inuring to local communities. Harvesting NTFPs for household utilization is permitted as it is for commercial purposes so long as it is done in a balanced and sustainable manner that does not adversely impact the environment or the community forest ecosystem.

However, utilization and conservation efforts often conflict which raises the question of how to manage forest resources to appease both objectives. This article will examine forest economics, conservation, and NTFP utilization in Thailand community forests and explore the possibility that utilizing NTFPs can not only improve rural livelihoods but can also foster sustainable management of local forests.

TRANSITION OF THAILAND’S FORESTS

Thailand is one of the most bio-diverse countries in Southeast Asia and one of the 20 most bio-diverse countries in the world (The Swiftest, 2022). Forests cover 31.57% of the country with 63.53% of the northern, 59% of the western and 24.32% of the southern Thailand regions covered by forests (Royal Forest Department, 2022). The primary forest types are deciduous (mixed deciduous and dry dipterocarp forests) comprising 18.26% of the country’s forests. Other types include dry evergreen (4.30%), moist evergreen (3.68%), and montane forests (3.38%) (Royal Forest Department, 2019).

Historically, illegal logging and the demand for agricultural land have significantly and detrimentally impacted Thailand’s forests (Thai Forestry Sector Master Plan, 1993). Most notably, they have had wide-reaching and adverse effects on the economy, the environment, and the local residents. In 1961, forests covered 53.33% of the country’s total land area (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). In 1973, the forest area was 43.21%; in 1998 it was 25.28%, less than half of what it was in 1961 (Royal Forest Department, 2022). After 2000, technological advancements provided for more accurate analysis of forest coverage and a re-assessment of deforestation rates. Prior thereto, LANDSAT-5 imageries of a 1:200,000 scale were produced and assessed. Due to an improvement in scale to 1:50,000 and a modified method of calculation, new forest area standards were established (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009). This expanded the detectable areas to include smaller, previously inestimable forest areas. Even though the Thai government imposed a nationwide logging ban in natural forests in 1989, thereby elevating the focus of forest management on local participation, promoting ecotourism and a greater understanding of NTFP utilization behaviors and impacts, Thailand is still facing issues that are having an adverse impact on forest resources and livelihoods.

Despite governmental efforts, no less than 1,442 plants have been classified as endangered species in the IUCN Red List (Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, 2017). Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning (2020) reported that three plant species are extinct in nature while 999 species are classified as threatened; 647 species as Vulnerable (VU), 259 species as Endangered (EN) and 93 species as Critically Endangered (CR). Climate change, encroachment, fires, and land development all impact forest biodiversity and contribute to biodiversity loss. Thus, discussions of how to balance forest conservation with sustainable management to allow for beneficial utilization remain salient and ongoing.

STRATEGIES AND POLICIES

Pursuant to the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037), Thailand has committed to increase its green area cover to 55% with 35% being classified as natural forests, 15% as forest areas for utilization, and 5% for green areas or stands of trees outside forests. In addition, Thailand’s 1985 National Forest Policy, which was modified in 2019, reiterated Thailand’s goal of maintaining at least 40% of the country’s total area as forests, 25% for conservation forests and 15% for economic forests. Strategies to achieve these goals focused on forest management, forest product utilization and forest services and industry (Royal Forest Department, 2021). This indicates a commitment to a combination of policies and strategies aimed at balancing forest economics and conservation to ensure that economic benefits from forests through conservation can be realized.

Increasing forest areas and achieving these goals is challenging and involves numerous stakeholders, namely, governmental agencies, the private sector, and a high level of participation by community residents. Currently, three organizations under the Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment (MONRE) are primarily responsible for the country’s forest resources. The Royal Forest Department (RFD) manages forest reserves that are outside protected areas, the Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) manages protected areas such as national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, arboretums, and forest parks, while the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMC) has authority over the mangrove resources.

Thailand has promulgated several acts of legislation which address forest resource management such as the Forest Act B.E. 2484 (1941), the National Reserved Forest Act B.E. 2507 (1964), the Forest Plantation Act B.E. 2535 (1992), the Chainsaw Act B.E. 2545 (2002), the National Park Act B.E. 2562 (2019), the Wild Animal Conservation and Protection Act, B.E. 2562 (2019) and the Community Forest Act B.E. 2562 (2019). In addition, it has adopted policies and strategies in pursuit of forest management that lead to sustainable availability of economic, social, and environmental benefits.

The present forest coverage approximates 32% of the country’s area. As the RFD aims to respond to the 20-Year National Strategic Plan and achieve the 55% green area cover goal, there is clearly work to be done. Forest areas decline and destruction of forest resources is not higher than in previous years, and forest areas are not likely to decline further. Policies have been adopted to promote the establishment of 15,000 community forests encompassing 1.6 million ha, that manage forest land in a systematic and fair manner, and promote the restoration of degraded forests, increase economic forest areas, and promote and develop green spaces in cities and rural areas. Moreover, there have been advancements in the management of forest resources, such as improved technology, cooperation with foreign administrations, permission policies, and wood and wood product certification (Royal Forest Department, 2021).

COMMUNITY FOREST MANAGEMENT

The concept of community forest management (CFM) has been widely accepted and implemented in many developing countries, including Thailand. It has been adopted as a very effective approach to restoring degraded forests, helping to fulfill the needs of local residents, increasing income and benefiting the poor. Community forest management is also generally recognized as an effective sustainable forest management tool. In Thailand, the RFD has promoted CFM since 1987 (Royal Forest Department, 2014). Evidence of the acceptance and expansion of CFM is reflected in the widespread level of participation throughout the country.

Thammanu et al. (2021) demonstrated a positive correlation between income from forests and CFM (people’s participation, community forest regulations, perception and understanding, and benefit sharing). This suggests that CFM can create income opportunities and promote development in community forests. That study further found that utilization of community forest resources tends to improve the economy of lower income households. Therefore, CFM can lead to the support of the livelihoods of the poor.

In accordance with the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037), the RFD aims to establish 10 million rai (1.6 million ha) of community forests in 15,000 villages. As of 31 May, 2024, 11,193 community forest projects in 12,801 villages encompassing approximately 1 million ha or 6% of the country’s total forest area have been implemented (Royal Forest Department, 2024). The proliferation of community forest projects after the Community Forest Act 2019 has resulted in the noteworthy expansion of forest areas in Thailand (Table 1). Moreover, the Community Forest Act 2019 addresses and supports forest economics as well as community conservation efforts through enforceable legislation and regulations.

UTILIZATION OF NTFPs IN A COMMUNITY FOREST

Worldwide, bio-diverse forest resources are crucial to the livelihoods of 1.6 billion people, or more than 25% of the world’s population, who live in proximity to forests (The World Bank, 2001). These resources, including NTFPs, contribute to basic needs and supplement income especially of lower income households in developing countries. CFM can support crucial NTFP sustainability. NTFPs sourced from forest ecosystems are crucial contributors to household incomes and their general well-being. Dependence on NTFPs by lower income households to support their livelihoods has been reported in many parts of the world.

Increased trade in NTFPs has been shown to slow deforestation by increasing the economic value of forest biodiversity; effective local institutional management can reduce forest degradation (Ostrom et al., 1994; Shanley et al., 2002; Ostrom, 2005). In addition, the responsible use of NTFPs under CFM can lead to successful forest management that is beneficial to human well-being and preservation of ecosystem services thereby improving rural livelihoods and supporting conservation efforts (Jumbe & Angelsen, 2007; Coulibaly-Lingani et al., 2011; Soe & Youn, 2019b). NTFPs provide food, serve other daily functions, and generate income to people in nearby communities. Many case studies in developing countries have shown that NTFPs can contribute economic benefits to households. For example, in a study conducted in Congo, it was estimated that 23.3% of total household income derived from NTFPs (Mondo et al., 2024), in Nigeria it was 20-60% (Suleiman et al., 2017) and in Myanmar, NTFPs accounted for 37% of the total household income (Soe & Youn, 2019a). A study in Bangladesh reported that NTFPs contributed 56.9% of total annual household incomes (Rahman et al., 2021).

NTFPs are used for daily household consumption and are often traded in local markets to provide and supplement household income. Commonly, NTFPs utilized in Thailand communities include edible plants, wild fruits, medicinal plants, fuelwood, mushrooms, insects, wild animals, fibers, and extractives. The average annual income from selling NTFPs in local markets in Thailand is estimated to be over US$25,000 per village (Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning, 2004) and over US$2 billion nationwide (International Tropical Timber Organization, 2006).

According to Thammanu et al. (2021), the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest in Lampang province in the north of Thailand, yielded a net return of approximately THB1,871,117.30 (US$60,358.62) from NTFPs to the community, an average of THB7,060.82 (US$227.77) per year/household. When comparing income to the cost of collection, mushrooms provided the highest net return (73.47%), followed by wild fruits (14.93%), small animals (6.04%), and edible plants (3.18%).

Many tree species provide foods such as Melientha suavis, Irvingia malayana, Adenia viridiflora, Cycas siamensis, Phyllanthus emblica, Trevesia plamata. Trees such as Elephantopus scaber and Eurycoma longifolia have medicinal value. In addition, some tree species are sourced as fuelwood such as Shorea spp. and some species such as Bauhinia strychnifolia as fiber. Moreover, some non-tree species were food sources such as mushrooms (Amanita spp., Astraeus spp., Cantharellus sp., Russula sp., Termitomyces spp.), insects (Oecophylla smaragdina), honey (Apis dorsata), and small animals (Kaloula pulchra, Glyphoglossus molossus, Leiolepis belliana).

Thailand has a very diverse composition of species, especially those used for medicines and foods. Previous research has found that NTFP utilization of some plant species was low when compared with their availability. This indicates greater potential for NTFP utilization and its concomitant benefits. An inventory of the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Lum Community Forest yielded a total of 18,567 plants that encompassed 197 species, 144 genera, and 62 plant families. Of these, 160 plant species have been classified as having medicinal uses, 89 are used as food, 37 as extractive products, 32 as fuelwood, and 12 as fibers.

Only 6.35% of the total household income is attributed to the collection and utilization of NTFPs from the Ban Mae Chiang Rai Community Forest, which primarily came from food and herb NTFPs. Compared to other case studies in developing countries, as indicated above (Congo 23.3%, Nigeria 20-60%, Myanmar 37% and Bangladesh 56.9%), this percentage of income was low. This can be attributed to a lack of technology, insufficient transfer of practical local wisdom or even a financial calculus as harvesting forest products may not be as economically beneficial for a household as other employment away from the home. Regardless, the relatively low level of harvesting reflects that a potential for greater income exists, and enhancement of forest biodiversity to provide a larger and ongoing supply of NTFPs is needed.

Section 50 of Thailand’s community forest law increases the emphasis on the collection of forest products for use (Thai government, 2019). In conformity with the relevant laws, a community forest area is divided into areas for conservation and utilization. The utilization area does not exceed 40% of the total area or it can be designated as an area for conservation in its entirety. This facilitates the establishment of community enterprises to develop products for sale. Despite this favorable framework, a lack of funding, knowledge and technology to develop products to market and sell remain obstacles to achieving economic sustainability. The government, universities, the business sector and the public in general all need to cooperate to overcome these hurdles.

LINKING FOREST ECONOMICS AND CONSERVATION TO RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Utilization of forest resources not only affects species diversity, but also has a long-term impact on ecosystem health and resiliency (Rowe, 2009). Consequently, the dynamics and conflicts in the relationship between forest utilization and biodiversity conservation can affect people’s livelihoods. Effectively implemented forest management can help to safeguard species diversity and the ecosystem services it provides as well as improve rural livelihoods.

Previous research has shown that the benefits attained from forests were closely associated with the level of participation in conservation. In a Thailand study, people who were NTFP dependent were likely to participate more in CFM (Thammanu et al., 2021). This finding is consistent with studies in other countries wherein income derived from NTFPs is positively correlated with participation in forest management. In Cambodia, incentives from extraction of NTFPs motivate local people to join in forest protection and to contribute money for forest patrols (Chou, 2018). In Sumatra, Indonesia, Harbia et al. (2018) found that harvesting rattan can simultaneously benefit local livelihoods and forest conservation. These studies generally support the proposition that economic benefits of NTFPs can incentivize participation while also supporting forest conservation and rural development. This information can inform effective forest management strategies and policies toward sustainable forest management.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on this discussion, the following observations about improving forest management to develop living conditions and conserve the biodiversity of community forests in Thailand can be made:

2) Receiving NTFP income leads to contributing to, and participating in, the management of a community forest. Involvement has a positive impact on management effectiveness which can create opportunities for more income. A relationship exists between NTFP dependence and participation for the benefit of all; this is a relationship that should be demonstrated and used to incentivize participation.

3) Realizing the potential of community forests in Thailand is an important driver in promoting involvement by local residents in local forest activities to conserve and preserve forest resources. A greater emphasis should be placed on promoting the generation of income from collecting NTFPs to the community. Value added development of NTFPs to increase their potential should also be considered. The government sector should provide regulatory, financial, educational and technological support to facilitate the implementation. The private sector and businesses should be recruited to promote community enterprises to compete in the market. Having a secure income will incentivize conservation of forest resources and assist in the overall rural development that will inevitably accrue from sustainable forest management.

4) CFM is an important tool in the pursuit of increasing green and forest areas in accordance with the 20-Year National Strategic Plan (2018-2037) and of the National Forest Policy while simultaneously addressing economic and conservation concerns. The Thai government should promulgate legislative and other policies to support the utilization of biodiversity through encouraging people’s participation, particularly of NTFP utilization. Doing so will not only address deforestation and forest degradation, but will also secure NTFPs as a source of income, enhance the quality of life and have a beneficial impact on the environment.

REFERENCES

Chou, P. (2018). The role of non-timber forest products in creating incentives for forest conservation: A case study of Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary. Cambodia, Resources, 7(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources7030041.

Center for International Forestry Research. (2008). Non-timber forest products. Available online: https://www2.cifor.org/ntfpcd/, April 1, 2024.

Coulibaly-Lingani, P., Savadogo, P., Tigabu, M., & Oden, P.-C. (2011). Factors influencing people’s participation in the forest management program in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Forest Policy and Economics, 13(4), 292-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.02.005.

Department of National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. (2017). Threatened plants in Thailand. Omega Printing Co., Ltd., Bangkok, p 224.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2009). Thailand forestry outlook study. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/am617e/am617e00.pdf

Harbia, J., Erbaugh, J.T., Sidiq, M., Haasler, B., & Nurrochmat, D.R. (2018). Making a bridge between livelihoods and forest conservation: lessons from non timber forest products’ utilization in South Sumatera, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 94, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.05.011.

International Tropical Timber Organization. (2006). Achieving the ITTO objective 2000 and sustainable forest management in Thailand. Available online: https://www.itto.int/direct/topics/topics_pdf_download/topics_id=31270000&no=1&disp=inline, December 20, 2023

Jumbe, C.B.L., & Angelsen, A. (2007). Forest dependence and participation in CPR management: empirical evidence from forest co-management in Malawi. Ecological Economics, 62(3-4), 661-672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.08.008.

Liang, J., Crowther, T.W., Picard, N., Wiser, S., Zhou, M., Alberti, G., Schulze, E.-D., & et al. (2016). Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science, 354(6309), aaf8957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8957.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: biodiversity synthesis. World Resource Institute, Washington DC.

Mondo, J.M., Chuma, G.B., Muke, M.B., Fadhidi, B.B., Kihye, J.B., Sibomana, C.I., Kazamwali, L.M.. & et al. (2024). Utilization of non-timber forest products as alternative sources of food and income in the highland regions of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Trees, Forests and People, 16 (2024) 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100547.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2004). Thailand environment monitor series. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2009). Thailand: national report on the implementation of the convention on biological diversity. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok.

Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning. (2020). The status of biodiversity in Thailand. Office of National Resources and Environment Policy and Planning, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Ostrom, E., Gardner, R., & Walker, J. (1994). Rules, games and common-pool resources. University of Michigan Press, Michigan.

Rahman, M.H., Roy, B., & Islam, M.S. (2021). Contribution of non-timber forest products to the livelihoods of the forest-dependent communities around the Khadimnagar National Park in northeastern Bangladesh. Regional Sustainability, 2(3), 280-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2021.11.001.

Rowe, R.J. (2009). Environmental and geometric drivers of small mammal diversity along elevational gradients in Utah. Ecography, 32(3), 411-422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05538.x.

Royal Forest Department. (2014). Implementation guidelines for communit forest projects of the Royal Forest Department. Community Forest Management Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2019). Executive summary. Forest Land Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2021). The Royal Forest Department’s 20-year (2018-2037) implementation plan. Planning and Information Office, Bangkok. (in Thai)

Royal Forest Department. (2022). Forestry Statistics Data 2022. Information Technology and Communication Center. Available online: http://forestinfo.forest.go.th/Content.aspx?id=10400, November 10, 2023.

Royal Forest Department. (2024). Information from Community Forest Act 2019. Community Management Office. Available online: https://www.forest.go.th/community-extension/, June 7, 2024.

Shanley, P., Luz, L., & Swingland, I.R. (2002). The faint promise of a distant market: a survey of Belém’s trade in non-timber forest products. Biodiversity & Conservation, 11, 615-636. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015556508925.

Soe, K.T., & Youn, Y. (2019a). Livelihood Dependency on Non-Timber Forest Products: Implications for REDD+. Forests, 10(5), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10050427.

Soe, K.T., & Youn, Y. (2019b). Perceptions of forest-dependent communities toward participation in forest conservation: a case study in Bago Yoma, South-Central Myanmar. Forest Policy and Economics, 100, 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.11.009.

Suleiman, M.S., Wasonga, V.O., Mbau J.S., Suleiman, A., & Elhadi, Y.A. (2017). Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecological Process, 6(23). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0090-8.

Thai Forestry Sector Master Plan. (1993). Thai forestry sector master plan vol. 5, subsectoral plan for people and forestry environment. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, and FINNIDA, Bangkok.

Thai Government. (2019). Community Forest Act, B.E. 2562; Royal Thai Government Gazette: Bangkok, Thailand.

Thammanu, S., Han, H., Ekanayake, E.M.B.P., Jung, Y., & Chung, J. (2021). Sustainability, 13(23), 13474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313474.

Thammanu, S., Han, H., Marod, D., Zang, L., Jung, Y., Soe, K.T., Onprom, S., & Chung, J. (2020). Forest Science and Technology, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/21580103.2020.1862712.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are grateful to the Royal Forest Department (RFD) for providing the opportunity to pursue this research and for facilitating the preparation of this writing. Publication would otherwise not be possible without the assistance of RFD’s staff. All of its assistance and support are greatly appreciated.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.