CBFM: A National Strategy for Sustainable Forest Management[1]

Albert P. Aquino and Carl Rookie O. Daquio[2]

INTRODUCTION

Context

Forests used to be one of the richest natural resources in the Philippines. In fact, in 1900, more than 70%, on average, of the island’s total land area of 30 million hectares (ha) was covered with forests (ESSC, 1999a). Presently, of the country’s 15.86 million ha of classified and unclassified forestlands, only 6.52 million (41.11%) ha is under actual forest cover.

The decline in forest cover goes along with a significant loss of biodiversity, raw materials and storage capacity for water and an alarming release of greenhouse gases through the slash and burning cultivation/farming (Salzer, 2012). In economic terms, the challenge of the government to determine who should be held accountable for the open access nature of many forest lands leading to resource degradation is difficult (Carig, 2012). The continuous influx of migrant communities has further aggravated the diminishing forest resources. Given the dependence of human and social life of products from the forest-from wood to water and to the oxygen they produce-these consequences impinge on all sectors of the society.

Approach

In recognition of the urgent need for effective action to minimize negative upstream-downstream and on-site-off-site impacts of forest management externalities (Wallace, 1993), the Philippines in 1995, officially adopted the Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) as its overall strategy of the government towards the management and protection of forest and forestlands. This policy formulation was made through Presidential Executive Order (EO) No. 263, and allied people-oriented policies and programs of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

From a highly centralized form of management with punitive environmental laws, forest management evolved into more people responsive and participatory in nature (Carig, 2012). EO No. 263 identifies local forest communities, including indigenous people to be represented by their People’s Organization (POs)[3] and traditional tribunal councils as immediate stakeholders of the forestland resources in the protection and management of the forest ecosystem. The government expected that with the improvement in socio-economic condition of local communities, management of natural resources will also follow.

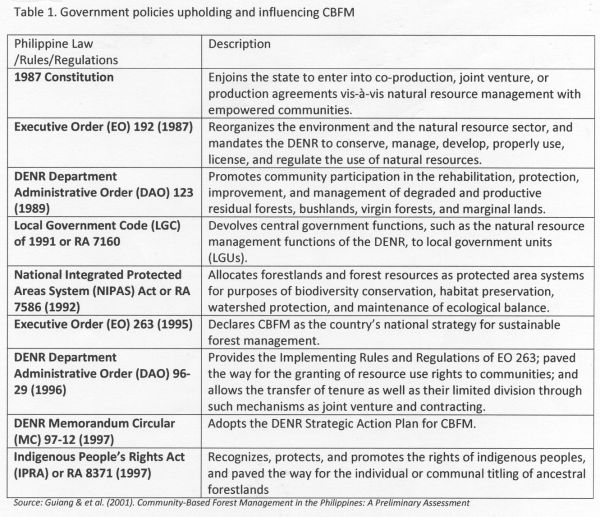

The CBFM is anchored on current and applicable policies of the Philippine government to (1) democratize access to forests and forest resources, (2) improve the upland communities’ socio-economic condition, (3) decentralize and devolve forest and forestland management, and (4) conserve biodiversity and maintain the environmental services of forests and forestlands to both on-site and off-site communities (Table 1).

Key features of CBFM[4]

Taking into account the ecological, social, and policy imperatives mentioned above, the Philippines has pursued the following key strategies through its CBFM program:

-

Security of Tenure. The policy includes the mechanism for legitimizing resource access and use rights through the issuance of long-term tenurial instruments, particularly the Community-Based Forest Management Agreement (CBFMA) for participating upland migrant communities, and the Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim (CADC)[5] for indigenous people.

-

Social Equity. Social justice is a basic principle underlying CBFM in granting forest communities and comprehensive rights to use and develop forest resources.

-

DENR and LGU Partnership. DENR and LGUs provide technical assistance to CBFM participants to help them attain sustainable forest management.

-

Investment Capital and Market Linkage. CBFM helps participants’ access investment capital, identify markets, and build marketing capabilities.

Extent and Coverage of CBFM

CBFM covers all areas classified as forestlands, including allowable zones within the protected areas not covered by prior vested rights. The program integrates and unifies all people-oriented forestry activities of the Integrated Social Forestry Program, Community Forestry Program, Coastal Environment Program, and Recognition of Ancestral Domain (Primer on CBFM, n.d.).

Since its launching in 1995, 5,503 projects were already established. These encompass an aggregate area of 5.97 million ha awarded to organize upland communities comprising about 690,691 households (Pulhin & et al., 2009). Of these areas, 1,577 sites with a total area of 1.57 million ha were allocated to organized communities through the issuance of long-term CBFMA (Bacalla, n.d.). The rest of the project sites were covered by land tenure instruments under the various people-oriented forestry projects that the Philippine government has implemented in the past.

The 5.97 million ha currently covered by CBFM represents 66.3% of the total area of 9 million ha targeted by the government. This is a concrete manifestation of the government’s determination to carry out its policy of involving and allocating suitable portions of forestlands devolved to different stakeholders for management and protection (Bacalla, n.d.).

CBFM Assessments and Reflections of Implementations

Over the years, CBFM has evolved from a forestry approach that covers only individual/family upland farms or claims into one that encompasses larger forest areas and different land use mixes. CBFM areas now include any or a combination of the following: (1) forestlands that have been planted or areas with existing reforestation projects, (2) grasslands that are quickly becoming the expansion area of upland agriculture, (3) areas with productive residual and old growth forests, and (4) multiple-use and buffer zones of protected areas and watershed reservations (Guiang & et al., 2001).

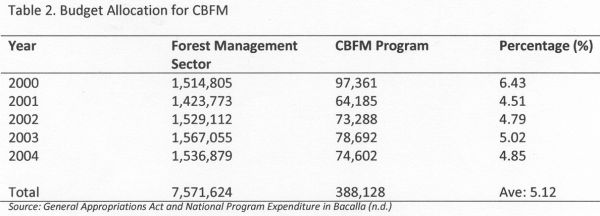

However, despite the continuous expansion of CBFM, a number of problems continue to beset its implementation (Bacalla, n.d.). First, the access of local communities to forest resources requires complex procedures relating to harvesting timber resources. In addition, there are plenty of restrictions being imposed on POs before they are allowed to utilize these resources. Second, the institutional insufficiencies affect CBFM’S overall policy implementation. The limited number of DENR staff, particularly at the field level, impedes the implementation of CBFM. The lack of appropriate capacity and necessary attitudes to provide technical assistance and to conduct regular monitoring of the implementation further aggravates the situation. And lastly, while CBFM contribution to forest management is incalculable, only a meager budget is provided for the program to be fully implemented. In fact, CBFM has only received an annual average of 5.12% out of the total forestry sector budget (Table 2) during the last five years (F.Y. 2000-2004).

CONCLUSION

The primary mandate of the development of CBFM comes with the associated tasks of national struggle against corruption and ineffective government, and with efforts to devolve power and control over natural resources from the state to the communities.

CBFM has come a long way in making natural resource assets available to upland occupants who depend on the forest. Improved forest conditions benefitted the life chances of both the communities involved and the forests they depend on. In addition, the mobilization of local communities as ‘partners’ in forest governance provides opportunities for them to learn to organize and manage themselves vis-à-vis their resource management practices.

While CBFM’s policy and institutional support is identified as a major area of concern, there’s a need to review CBFM policies and streamline operational guidelines to address the needs at the local level, especially on the criteria for the selection of participants, issuance of tenure instruments and utilization of forest resources.

References

Bacalla, D. (n.d.). Promoting Equity: A Challenge in the Implementation of Community-Based Forest Management Strategy in the Philippines.

Carig, E. (2012). Impact Assessment of Community-Based Forest Management in the Philippines: A Case study of CBFM Sites in Nueva Vizcaya. Paper presented during the International Conference on Management and Social Sciences, Penang Malaysia, 19 - 20 June.

Environmental Science for Social Change (ESSC) (1999a). The Decline of the Philippine Forests. Quezon City: ESSC.

Guiang, E., Borlagdan, S., & Pulhin, J. (2001). Community-Based Forest Management in the Philippines: A Preliminary Assessment. Institute of Philippine Culture of Ateneo de Manila University in collaboration with Department of Social Forestry and Forest Governance, College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines at Los Baños.

Pulhin, J. & M. Tapia, (2009). "Devolving bundles of rights or bundles of responsibilities?”. Paper presented during the XIII World Forestry Congress on Argentina, 18 – 23 October.

Salzer, W. (2012). Factsheet: Environment and Rural Development (EnRD) Program Philippines. Component 4: Community-based Forest Management (CBFM)

Wallace, M. (1993). “Philippine Forests: Private Privilege or Public Preserve?” Paper presented during the Fourth Annual Common Property Conference, International Association for the Study of Common Property, Manila, 19 June. Accessed on 27 May 2014: http://www.lawphil.net/executive/execord/eo1995/eo_263_1995.html

[1] A short policy paper submitted to the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC) for the project titled “Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy”. Short policy papers, as corollary outputs of the project, describe pertinent Philippine laws and regulations on agriculture, aquatic and natural resources.

[2] Philippine Point Person to the FFTC Project on Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy and Director and Science Research Analyst, respectively, of the Socio-Economics Research Division-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (SERD-PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Los Baños, Laguna, the Philippines.

[3] A People’s Organization (PO) may be an association, cooperative, federation or other legal entity established by the community to undertake collective action to address community concerns and needs and mutually share the benefits from the endeavor.

[4] Partly lifted from DENR’s Primer on CBFM

[5] The rights of indigenous peoples were further strengthened in 1997 with the passage of the Indigenous People’s Right Act (IPRA or Republic Act 8371) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations.

|

Date submitted: July 29, 2014

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: July 30, 2014

|

CBFM: A National Strategy for Sustainable Forest Management

CBFM: A National Strategy for Sustainable Forest Management[1]

Albert P. Aquino and Carl Rookie O. Daquio[2]

INTRODUCTION

Context

Forests used to be one of the richest natural resources in the Philippines. In fact, in 1900, more than 70%, on average, of the island’s total land area of 30 million hectares (ha) was covered with forests (ESSC, 1999a). Presently, of the country’s 15.86 million ha of classified and unclassified forestlands, only 6.52 million (41.11%) ha is under actual forest cover.

The decline in forest cover goes along with a significant loss of biodiversity, raw materials and storage capacity for water and an alarming release of greenhouse gases through the slash and burning cultivation/farming (Salzer, 2012). In economic terms, the challenge of the government to determine who should be held accountable for the open access nature of many forest lands leading to resource degradation is difficult (Carig, 2012). The continuous influx of migrant communities has further aggravated the diminishing forest resources. Given the dependence of human and social life of products from the forest-from wood to water and to the oxygen they produce-these consequences impinge on all sectors of the society.

Approach

In recognition of the urgent need for effective action to minimize negative upstream-downstream and on-site-off-site impacts of forest management externalities (Wallace, 1993), the Philippines in 1995, officially adopted the Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) as its overall strategy of the government towards the management and protection of forest and forestlands. This policy formulation was made through Presidential Executive Order (EO) No. 263, and allied people-oriented policies and programs of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

From a highly centralized form of management with punitive environmental laws, forest management evolved into more people responsive and participatory in nature (Carig, 2012). EO No. 263 identifies local forest communities, including indigenous people to be represented by their People’s Organization (POs)[3] and traditional tribunal councils as immediate stakeholders of the forestland resources in the protection and management of the forest ecosystem. The government expected that with the improvement in socio-economic condition of local communities, management of natural resources will also follow.

The CBFM is anchored on current and applicable policies of the Philippine government to (1) democratize access to forests and forest resources, (2) improve the upland communities’ socio-economic condition, (3) decentralize and devolve forest and forestland management, and (4) conserve biodiversity and maintain the environmental services of forests and forestlands to both on-site and off-site communities (Table 1).

Key features of CBFM[4]

Taking into account the ecological, social, and policy imperatives mentioned above, the Philippines has pursued the following key strategies through its CBFM program:

Extent and Coverage of CBFM

CBFM covers all areas classified as forestlands, including allowable zones within the protected areas not covered by prior vested rights. The program integrates and unifies all people-oriented forestry activities of the Integrated Social Forestry Program, Community Forestry Program, Coastal Environment Program, and Recognition of Ancestral Domain (Primer on CBFM, n.d.).

Since its launching in 1995, 5,503 projects were already established. These encompass an aggregate area of 5.97 million ha awarded to organize upland communities comprising about 690,691 households (Pulhin & et al., 2009). Of these areas, 1,577 sites with a total area of 1.57 million ha were allocated to organized communities through the issuance of long-term CBFMA (Bacalla, n.d.). The rest of the project sites were covered by land tenure instruments under the various people-oriented forestry projects that the Philippine government has implemented in the past.

The 5.97 million ha currently covered by CBFM represents 66.3% of the total area of 9 million ha targeted by the government. This is a concrete manifestation of the government’s determination to carry out its policy of involving and allocating suitable portions of forestlands devolved to different stakeholders for management and protection (Bacalla, n.d.).

CBFM Assessments and Reflections of Implementations

Over the years, CBFM has evolved from a forestry approach that covers only individual/family upland farms or claims into one that encompasses larger forest areas and different land use mixes. CBFM areas now include any or a combination of the following: (1) forestlands that have been planted or areas with existing reforestation projects, (2) grasslands that are quickly becoming the expansion area of upland agriculture, (3) areas with productive residual and old growth forests, and (4) multiple-use and buffer zones of protected areas and watershed reservations (Guiang & et al., 2001).

However, despite the continuous expansion of CBFM, a number of problems continue to beset its implementation (Bacalla, n.d.). First, the access of local communities to forest resources requires complex procedures relating to harvesting timber resources. In addition, there are plenty of restrictions being imposed on POs before they are allowed to utilize these resources. Second, the institutional insufficiencies affect CBFM’S overall policy implementation. The limited number of DENR staff, particularly at the field level, impedes the implementation of CBFM. The lack of appropriate capacity and necessary attitudes to provide technical assistance and to conduct regular monitoring of the implementation further aggravates the situation. And lastly, while CBFM contribution to forest management is incalculable, only a meager budget is provided for the program to be fully implemented. In fact, CBFM has only received an annual average of 5.12% out of the total forestry sector budget (Table 2) during the last five years (F.Y. 2000-2004).

CONCLUSION

The primary mandate of the development of CBFM comes with the associated tasks of national struggle against corruption and ineffective government, and with efforts to devolve power and control over natural resources from the state to the communities.

CBFM has come a long way in making natural resource assets available to upland occupants who depend on the forest. Improved forest conditions benefitted the life chances of both the communities involved and the forests they depend on. In addition, the mobilization of local communities as ‘partners’ in forest governance provides opportunities for them to learn to organize and manage themselves vis-à-vis their resource management practices.

While CBFM’s policy and institutional support is identified as a major area of concern, there’s a need to review CBFM policies and streamline operational guidelines to address the needs at the local level, especially on the criteria for the selection of participants, issuance of tenure instruments and utilization of forest resources.

References

Bacalla, D. (n.d.). Promoting Equity: A Challenge in the Implementation of Community-Based Forest Management Strategy in the Philippines.

Carig, E. (2012). Impact Assessment of Community-Based Forest Management in the Philippines: A Case study of CBFM Sites in Nueva Vizcaya. Paper presented during the International Conference on Management and Social Sciences, Penang Malaysia, 19 - 20 June.

Environmental Science for Social Change (ESSC) (1999a). The Decline of the Philippine Forests. Quezon City: ESSC.

Guiang, E., Borlagdan, S., & Pulhin, J. (2001). Community-Based Forest Management in the Philippines: A Preliminary Assessment. Institute of Philippine Culture of Ateneo de Manila University in collaboration with Department of Social Forestry and Forest Governance, College of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of the Philippines at Los Baños.

Pulhin, J. & M. Tapia, (2009). "Devolving bundles of rights or bundles of responsibilities?”. Paper presented during the XIII World Forestry Congress on Argentina, 18 – 23 October.

Salzer, W. (2012). Factsheet: Environment and Rural Development (EnRD) Program Philippines. Component 4: Community-based Forest Management (CBFM)

Wallace, M. (1993). “Philippine Forests: Private Privilege or Public Preserve?” Paper presented during the Fourth Annual Common Property Conference, International Association for the Study of Common Property, Manila, 19 June. Accessed on 27 May 2014: http://www.lawphil.net/executive/execord/eo1995/eo_263_1995.html

[1] A short policy paper submitted to the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center (FFTC) for the project titled “Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy”. Short policy papers, as corollary outputs of the project, describe pertinent Philippine laws and regulations on agriculture, aquatic and natural resources.

[2] Philippine Point Person to the FFTC Project on Asia-Pacific Information Platform in Agricultural Policy and Director and Science Research Analyst, respectively, of the Socio-Economics Research Division-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (SERD-PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), Los Baños, Laguna, the Philippines.

[3] A People’s Organization (PO) may be an association, cooperative, federation or other legal entity established by the community to undertake collective action to address community concerns and needs and mutually share the benefits from the endeavor.

[4] Partly lifted from DENR’s Primer on CBFM

[5] The rights of indigenous peoples were further strengthened in 1997 with the passage of the Indigenous People’s Right Act (IPRA or Republic Act 8371) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations.

Date submitted: July 29, 2014

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: July 30, 2014