ABSTRACT

Over the past five years(2015/16-2019/20), the average annual excess supply of rice in the Republic of Korea has been chronically increasing to 223,400 metric tons. On the other hand, the annual rice consumption per person is decreasing significantly from 119.6 kg in 1990 to 56.9 kg in 2021. Rice production in 2021 is 3,882 thousand metric tons, up 10.7% from 3,507 thousand metric tons in 2020, making it difficult to resolve the oversupply of rice in the short term. In June 2022, the nominal rice price was US$140.29 per 80 kg, down 18.5% from US$172.22 in June 2021. This downward trend of rice prices has continued since June 2021. Accordingly, the government quarantined about 270,000 metric tons of excess production in 2021 from the market twice in February and May 2022. The government announced on July 1 that it would quarantine 100,000 metric tons of rice again in the market. The new government, which was launched in May 2022, will also push to introduce a new type of production-adjusted direct payment system to improve the self-sufficiency rate of strategic crops such as wheat and soybeans in response to the food security crisis. This is aimed at preventing oversupply of rice, maintaining the base of rice self-sufficiency, and encouraging the production of strategic crops with low self-sufficiency. Meanwhile, on June 8, the government announced measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice, a type of rice exclusively for processing, to reduce dependence on wheat imports and solve the problem of oversupply of rice. By 2027, 200,000 metric tons of powdered rice will be supplied to replace 10% of the annual demand for about 2 million metric tons of flour.

Keywords: Rice policy, Market quarantine, Direct payment, Production adjustment, Powdered rice.

INTRODUCTION

Rice holds an important position in Korean agriculture. As of 2021, 533,000 farms, or 51.7% of the 1,031 thousand farms, have rice paddies. As of 2020, rice production was US$6.56 billion[1] out of US$38.6 billion in agricultural production, accounting for the highest proportion among single crops. In addition, rice income accounted for 32.8% of the average agricultural income per farm in 2021, making it an important crop that affects agricultural income.[2] Meanwhile, rice occupies an important position as a staple food of the people as well as agriculture, and as of 2019, 662 kcal, or 21.4% of the daily energy supply of 3,098 kcal, is supplied from rice (Korea Rural Economic Research Institute, 2020). This is more than twice as much as wheat (323 kcal) or meat (306 kcal). As such, rice has a large impact on the people's diet and the national economy, so the government has implemented a policy to supply rice stably through efficient supply and demand management.

There has been a major change in the rice policy since 2005. Until 2005, rice policies were implemented based on the government-led rice purchase system which the government purchases rice from farmers at a higher price than the market and sells it to the market at a lower price than the purchase price (Heo, Y.J., 2018). As a result, the government was able to simultaneously achieve policy goals such as increasing food production, supporting income for rice farmers, and stabilizing the lives of ordinary people (Kim, J.H., 2010). However, with the launch of the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 1995, subsidies to the rice purchase system were reduced from US$1.68 billion in 1995 to US$1.15 billion in 2004, and from 2005, the government's purchase volume could not exceed the subsidy limit, which will disrupt the operation of the rice purchase system. As the amount of rice purchased decreased[3], the government's supply and demand control function was weakened, and it was inevitable to reduce the size of farm income support through price support.

Accordingly, the government reformed rice policy by abolishing the rice purchase system to introduce public reserves program and the income of the compensation direct payment system for rice farmers since 2005. The public reserves program is a system where the government annually buys and sells a certain amount of rice at the market price to maintain an appropriate rice inventory level, letting the market determines the supply and demand of rice. For this reason, subsidies used in the public reserves program are classified as subsidies permitted by the WTO. In addition, the operation adopted a rotary stockpiling method in which only half of the stockpile is purchased and released every year. However, the government purchased only a certain amount of reserves every year regardless of rice supply and demand.[4] Therefore, the government's supply and demand control function was weakened. In addition, income compensation of the direct payment system for rice farmers was introduced to compensate rice farm income and stabilize management due to falling rice prices, which sets a target price and compensates 85% of the difference between the target price and the rice price during the harvest season.[5] Over the past 15 years, rice farmers have been able to maintain the rice price at 95.3% to 108.9% of the target price despite falling rice prices, and the ratio of farm prices to market prices during the harvest season has also been maintained at 106.6% to 138.1%. However, income compensation of the direct payment system for rice farmers was paid at a higher unit price than other crops.[6] There was a criticism that it served as a factor in the oversupply of rice (Kim, H.H. et al, 2014), and the income safety net function of small farmers was insufficient.[7] It was pointed out that there is a limit to improving the public profit function of agriculture and rural areas.

This system remained the basic framework of the rice income stabilization policy for 15 years until 2019. From 2020, the public direct payment system[8] has been introduced. It consisted of a basic direct payment system and an optional direct payment system. The basic direct payment system is divided into ‘area direct payment’ paid according to the size of the farmland and ‘small farm direct payment’ paid to farmers with small farm requirements regardless of the area. The optional direct payment system can be added to the basic direct payment by planting landscape conservation crops (landscape preservation direct payment), eco-friendly farming and livestock farming (green direct payment), and cultivating double cropping in rice paddies (direct payment using rice paddy). In order to receive the basic direct payment, there are requirements such as that the target farmland must have received the direct payment at least once during the period 2017-2019.

In recent years, rice prices have fallen significantly due to oversupply and reduced consumption. Accordingly, the rice market and rice policy trends will be analyzed recently.

RECENT RICE MARKET TRENDS

Rice oversupply and consumption decline

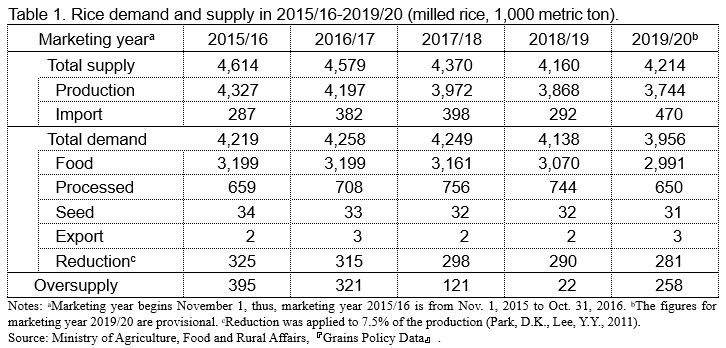

As of 2019/20, the excess rice supply was 258,000 metric tons, a significant increase from the previous year. This is because rice supply increased by 54,000 metric tons from the previous year, while rice demand decreased by 182,000 metric tons. Over the past five years (2015/16-2019/20), the average annual excess supply has been 223,400 metric tons. During the same period, rice supply decreased by 2.9% every year, while rice demand also decreased by 2.0% every year (Table 1).

In addition, due to the accumulation of excess rice, the average year-end inventory in the last five years (2016-2020)[9] is 1,390,000 metric tons. It was well above the level of 800,000 metric tons which is the amount that the entire nation can consume for about two months based on the recommended inventory level by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization).

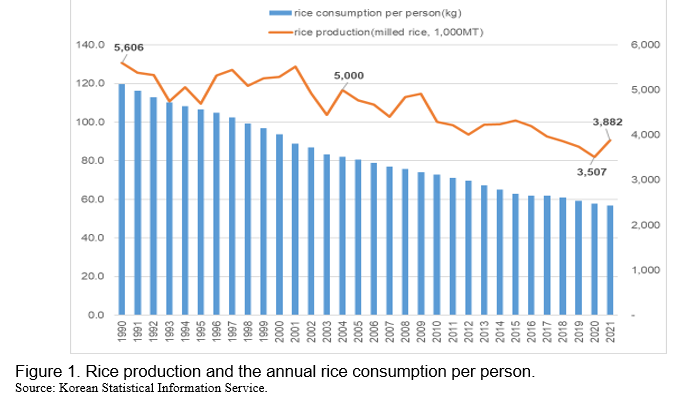

In particular, the annual consumption of rice per person is decreasing significantly. The annual rice consumption per person was 119.6 kg in 1990, but it was 56.9 kg in 2021, down more than half over the past 30 years. If this trend continues, there is a possibility that it will decrease to the range of around 50 kg or a little above in the next few years (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, rice production in 2021 was 3,882 thousand metric tons, up 10.7% from 3,507 thousand metric tons in 2020. Rice consumption is also continuously decreasing, making it difficult to resolve the oversupply in the short term.

Rice prices have been falling sharply recently

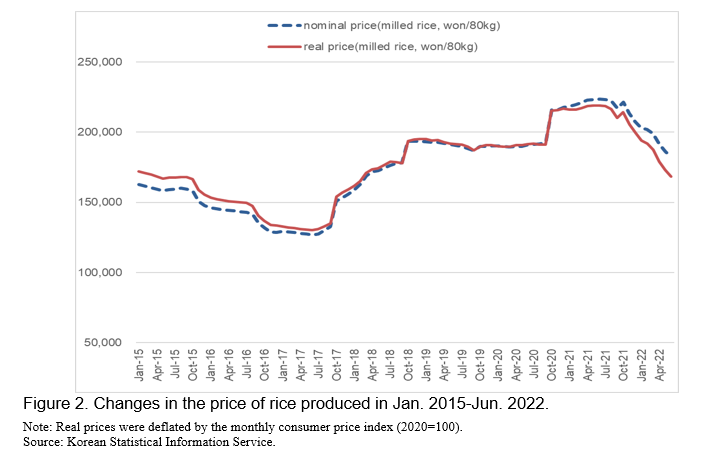

In June 2022, the nominal rice price was US$140.29 per 80 kg, down 18.5% from US$172.22 in June 2021, and the real rice price reflecting prices fell 23.2% during the same period. This downward trend in rice price of the produced stage has continued since June 2021 (Figure 2).

In addition, as the recent price of rice has fallen significantly, the rate of fluctuation in rice price at pre-harvest season (Jul.-Sep.) compared to the previous harvest period (Oct.-Dec.), that is, the seasonal amplitude, reached the highest record of –12.9% (Table 2). The reverse seasonal amplitude of such rice price acts as an incentive to sell excess inventory to the market, which eventually leads to a fall in rice price, adding to the management burden of agricultural cooperatives.[10]

RECENT RICE POLICY TRENDS

Rice market quarantine[11] three times this year

If the supply and demand control by market function was not smooth due to high yields, etc. after the abolition of the rice purchase system, the government intervened in the market through a rice supply and demand policy that purchases a certain amount of rice from the market.

A total of 2,162 thousand metric tons of rice had been quarantined from the market 14 times since 2005 and 2021, which is an average of 270,000 metric tons per year considering the 8 years the quarantine was implemented. That amount is 83.9% of the 322,000 metric tons of public reserves in 2020. The government's market intervention, or market quarantine supply and demand policy, is a policy tool to reduce the market supply afterwards in response to a drop in rice prices due to excessive rice supply. However, criticism has been raised that in the past, the rice market quarantine policy did not give a timely signal to the market because there were no clear standards for quantity and timing (Heo, Y.J., 2018).

Accordingly, the government institutionalized the rice supply and demand stabilization system by preparing the basis for the implementation of the preliminary rice market quarantine system through the revision of ‘the Grain Management Act’ in January 2020.[12] The preliminary rice market quarantine system is that preemptively quarantines excess production from the market after estimating appropriate production based on consumption prior to the harvest season. As rice price have fallen sharply recently, farmers’ organizations are demanding a revision of the law that mandates such a preliminary rice market quarantine system.

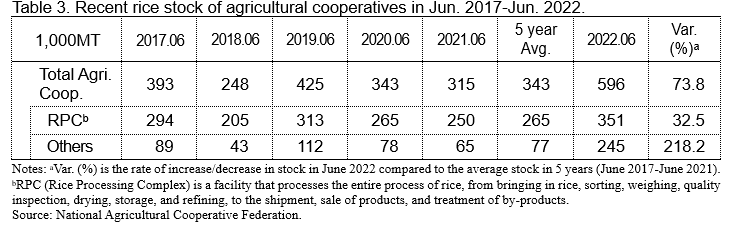

Recently, 3,882 thousand metric tons of rice production in 2021 exceeded the demand of 3,610 thousand metric tons (estimated) by about 270,000 metric tons. The government quarantined 270,000 metric tons twice in February and May this year. However, after twice market quarantine, the inventory of agricultural cooperatives still reached 596,000 metric tons in June 2022, up 73.8% from the average inventory of the past five years (343,000 metric tons) (Table 3). The government announced on July 1 that it would quarantine 100,000 metric tons of rice again in the market. Therefore, this year, the government purchased a total of 370,000 metric tons of rice produced last year on three occasions and quarantined it from the market.

The introduction of a new type of rice production adjustment system

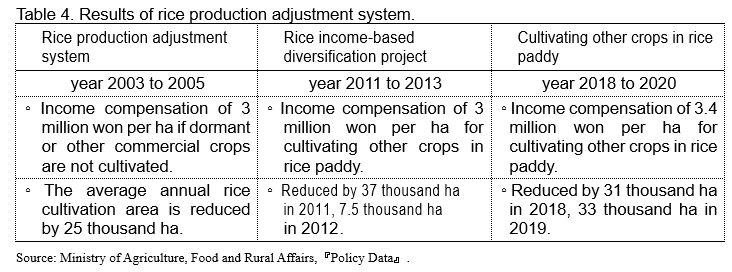

A rice production adjustment system was implemented three times in 2003, 2011, and 2018 to solve the problem of oversupply by reducing the area of rice cultivation in advance (Table 4). It was temporarily operated for two or three years in consideration of changes in supply and demand at the time, such as inventory reduction and poor harvest, and the impact on the supply and demand of crops cultivated instead of rice.

Recently, the new government, which was launched in May 2022, will also push to introduce a new type of production-adjusted direct payment system to improve the self-sufficiency rate of strategic crops such as wheat and soybeans in response to the food security crisis.[13] This is aimed at preventing oversupply of rice, maintaining the base of rice self-sufficiency, and encouraging the production of strategic crops with low self-sufficiency.

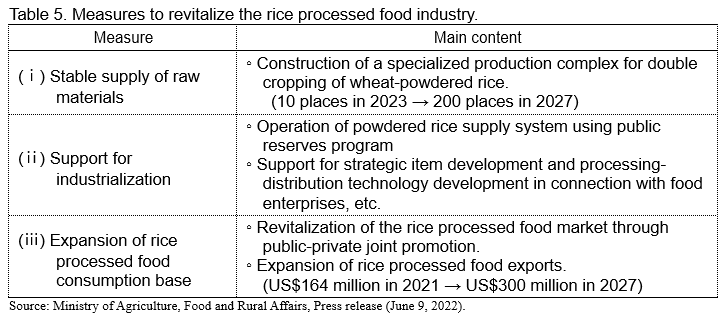

Revitalizing the rice processed food industry using powdered rice

On June 8, the government announced ‘measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice’ to reduce dependence on wheat imports and solve the problem of excessive rice supply. The goal is to supply 200,000 metric tons of powdered rice, a type of rice exclusively for processing, by 2027, replacing 10% of the annual demand for about 2 million metric tons of flour. To this end, three major policy measures were set up, preparing a stable raw material supply system, supporting industrialization, and expanding the consumption base of rice processed food (Table 5).

(ⅰ) In order to prepare a stable supply system for raw materials, it plans to create 10 production complexes specializing in growing rice to make powdered rice by 2023 and 200 by 2027, supporting direct payments, and guiding farm technology. (ⅱ) To support industrialization, it operates a powdered rice supply system using a public reserves program, and develops strategic products using powdered rice by providing samples to food and milling companies and supporting R&D. (ⅲ) In order to expand the consumption base of processed rice products, it operates a public-private joint governance to establish an ecosystem of powdered rice industry, and supports the use of food certification in the industry and expansion of exports.

Rice prices have fallen sharply in recent years. This is a structural phenomenon caused by the oversupply of rice due to the productivity increase and consumption decrease in rice. Policies to stabilize rice prices are being requested, and in particular, it is necessary to set policy goals in stabilizing rice prices and farm management through achieving a balance of rice supply and demand. First, it should be mandatory to operate the preliminary rice market quarantine system, which has institutionalized in 2020. Until now, temporary market quarantine has been carried out in the event of oversupply, but the effect has not reached the expected level due to the time lag between the market situation and the policy-making process, that is, market confusion. If the quantity exceeding the expected demand is preemptively quarantined during the harvest season, it is believed that the market confusion can be reduced due to the resolution of the market uncertainties. Also, it is necessary to encourage farmers to use rice paddies in different ways other than only growing rice. If the paddies are used in various ways, such as to grow wheat, beans, or rice for being powdered by means of the strategic crop direct payment system, which is recently planned to be introduced by the government, it will contribute to reducing the production of edible rice and creating new demand for rice. In addition, various efforts are needed to increase rice demand. In particular, continuous policy support is important, such as the government’s measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice. Providing rice processed foods for group meals such as school or military meals would be a good option to increase the demand for the foods. The above policies intended to stabilize the rice supply and demand are difficult to achieve in a short time, considering the low flexibilities of paddies, in particular, in terms of responding to the external environment, the lack of alternative crops, and low incentives to encourage elderly farmers to grow crops other than rice. Therefore, it is time to study and discuss policies to stabilize rice farm management, that is, policies to buffer the risk of price fluctuations, so that the structural improvement of the rice industry can be soft-landed.

Heo, Y.J., 2018, “Recent Rice Supply and Demand Trends and Policy Issues”, 『Rural and fishing communities, Environment』, The spring issue of 2018, pp.5-16.

Kim, H.H. et al, 2014,『A Study on the Improvement of Income Compensation Direct Payment System for rice farmers』, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Kim, J.H., 2010, “Rice Policy Direction in Republic of Korea”,『Food Storage and Processing Industries』, 9(2), pp.3-8.

Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs,『Grains Policy Data』, each year.

Park, D.K.·Lee, Y.Y., 2011, “Estimation of the Reduction Rate for the Improvement of Rice Reduction Statistics”,『Rural Economy』, 34(4), pp.41-58.

[1] US$ exchange rate standard as of June 30, 2022 (US$1=KRW1,298.4).

[2] As of 2021, the average agricultural income per farm is US$9,982. Rice income was estimated at US$3,279 among the agricultural income. Rice income (US$3,279) = Rice revenue (US$5,403) × Income rate (60.7%)

[3] The amount of rice purchased in 1993 accounted for 30.3% of rice production, but decreased to 14.2% in 2004.

[4] The actual amount of public reserves was 576,000 metric tons in 2005, 400,000 metric tons in 2008, 340,000 metric tons in 2011, 360,000 metric tons in 2015, 340,000 metric tons in 2018, 340,000 metric tons in 2019.

[5] (target price – rice price in harvest season) × 85% = fixed direct payment + variable direct payment. The target price was US$131.0 per 80kg at the time of introduction in 2005, increased to US$144.8 from 2013 to 2017, and increased to US$161.7 from 2018 to 2019. The unit price of fixed direct payment was continuously increased from US$462.1 per ha at the time of introduction in 2005, and US$770.2 was paid from 2015.

[6] The unit price of direct payment (variable payment +fixed payment) for rice was US$901.1 per ha, compared to US$385.1 for other crops.

[7] The proportion of small farmers (less than 1ha) receiving direct payments was only 29% of the total direct payments.

[8] The public direct payment system intends to provide subsidy to farmers to serve public purpose such as food safety and the conservation of environment and rural communities.

[9] 1,747,000 metric tons in 2016, 1,888,000 metric tons in 2017, 1,442,000 metric tons in 2018, 898,000 metric tons in 2019, 981,000 metric tons in 2020.

[10] The purchasing rice of agricultural cooperatives account for about 40% of all purchasing rice. In fact, RPC (Rice Processing Complex) in agricultural cooperatives had a profit and loss deficit of US$82.4 million in 2010, when the reverse seasonal amplitude was –7.9% (Heo, Y.J., 2018).

[11] Rice market quarantine is the government’s policy to reduce market supply by temporarily purchasing and storing up rice.

[12] According to Article 16 of ‘the Grain Management Act’, the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs shall establish and announce measures to stabilize the supply and demand of rice by October 15 every year.

[13] The grain self-sufficiency rate as of 2020 is 20.2%, and 3.2%, excluding rice. In particular, the self-sufficiency rate of wheat (0.5%), corn (0.7%), and soybeans (7.5%) is of great concern.

Recent Rice Policy Trends in the Republic of Korea

ABSTRACT

Over the past five years(2015/16-2019/20), the average annual excess supply of rice in the Republic of Korea has been chronically increasing to 223,400 metric tons. On the other hand, the annual rice consumption per person is decreasing significantly from 119.6 kg in 1990 to 56.9 kg in 2021. Rice production in 2021 is 3,882 thousand metric tons, up 10.7% from 3,507 thousand metric tons in 2020, making it difficult to resolve the oversupply of rice in the short term. In June 2022, the nominal rice price was US$140.29 per 80 kg, down 18.5% from US$172.22 in June 2021. This downward trend of rice prices has continued since June 2021. Accordingly, the government quarantined about 270,000 metric tons of excess production in 2021 from the market twice in February and May 2022. The government announced on July 1 that it would quarantine 100,000 metric tons of rice again in the market. The new government, which was launched in May 2022, will also push to introduce a new type of production-adjusted direct payment system to improve the self-sufficiency rate of strategic crops such as wheat and soybeans in response to the food security crisis. This is aimed at preventing oversupply of rice, maintaining the base of rice self-sufficiency, and encouraging the production of strategic crops with low self-sufficiency. Meanwhile, on June 8, the government announced measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice, a type of rice exclusively for processing, to reduce dependence on wheat imports and solve the problem of oversupply of rice. By 2027, 200,000 metric tons of powdered rice will be supplied to replace 10% of the annual demand for about 2 million metric tons of flour.

Keywords: Rice policy, Market quarantine, Direct payment, Production adjustment, Powdered rice.

INTRODUCTION

Rice holds an important position in Korean agriculture. As of 2021, 533,000 farms, or 51.7% of the 1,031 thousand farms, have rice paddies. As of 2020, rice production was US$6.56 billion[1] out of US$38.6 billion in agricultural production, accounting for the highest proportion among single crops. In addition, rice income accounted for 32.8% of the average agricultural income per farm in 2021, making it an important crop that affects agricultural income.[2] Meanwhile, rice occupies an important position as a staple food of the people as well as agriculture, and as of 2019, 662 kcal, or 21.4% of the daily energy supply of 3,098 kcal, is supplied from rice (Korea Rural Economic Research Institute, 2020). This is more than twice as much as wheat (323 kcal) or meat (306 kcal). As such, rice has a large impact on the people's diet and the national economy, so the government has implemented a policy to supply rice stably through efficient supply and demand management.

There has been a major change in the rice policy since 2005. Until 2005, rice policies were implemented based on the government-led rice purchase system which the government purchases rice from farmers at a higher price than the market and sells it to the market at a lower price than the purchase price (Heo, Y.J., 2018). As a result, the government was able to simultaneously achieve policy goals such as increasing food production, supporting income for rice farmers, and stabilizing the lives of ordinary people (Kim, J.H., 2010). However, with the launch of the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 1995, subsidies to the rice purchase system were reduced from US$1.68 billion in 1995 to US$1.15 billion in 2004, and from 2005, the government's purchase volume could not exceed the subsidy limit, which will disrupt the operation of the rice purchase system. As the amount of rice purchased decreased[3], the government's supply and demand control function was weakened, and it was inevitable to reduce the size of farm income support through price support.

Accordingly, the government reformed rice policy by abolishing the rice purchase system to introduce public reserves program and the income of the compensation direct payment system for rice farmers since 2005. The public reserves program is a system where the government annually buys and sells a certain amount of rice at the market price to maintain an appropriate rice inventory level, letting the market determines the supply and demand of rice. For this reason, subsidies used in the public reserves program are classified as subsidies permitted by the WTO. In addition, the operation adopted a rotary stockpiling method in which only half of the stockpile is purchased and released every year. However, the government purchased only a certain amount of reserves every year regardless of rice supply and demand.[4] Therefore, the government's supply and demand control function was weakened. In addition, income compensation of the direct payment system for rice farmers was introduced to compensate rice farm income and stabilize management due to falling rice prices, which sets a target price and compensates 85% of the difference between the target price and the rice price during the harvest season.[5] Over the past 15 years, rice farmers have been able to maintain the rice price at 95.3% to 108.9% of the target price despite falling rice prices, and the ratio of farm prices to market prices during the harvest season has also been maintained at 106.6% to 138.1%. However, income compensation of the direct payment system for rice farmers was paid at a higher unit price than other crops.[6] There was a criticism that it served as a factor in the oversupply of rice (Kim, H.H. et al, 2014), and the income safety net function of small farmers was insufficient.[7] It was pointed out that there is a limit to improving the public profit function of agriculture and rural areas.

This system remained the basic framework of the rice income stabilization policy for 15 years until 2019. From 2020, the public direct payment system[8] has been introduced. It consisted of a basic direct payment system and an optional direct payment system. The basic direct payment system is divided into ‘area direct payment’ paid according to the size of the farmland and ‘small farm direct payment’ paid to farmers with small farm requirements regardless of the area. The optional direct payment system can be added to the basic direct payment by planting landscape conservation crops (landscape preservation direct payment), eco-friendly farming and livestock farming (green direct payment), and cultivating double cropping in rice paddies (direct payment using rice paddy). In order to receive the basic direct payment, there are requirements such as that the target farmland must have received the direct payment at least once during the period 2017-2019.

In recent years, rice prices have fallen significantly due to oversupply and reduced consumption. Accordingly, the rice market and rice policy trends will be analyzed recently.

RECENT RICE MARKET TRENDS

Rice oversupply and consumption decline

As of 2019/20, the excess rice supply was 258,000 metric tons, a significant increase from the previous year. This is because rice supply increased by 54,000 metric tons from the previous year, while rice demand decreased by 182,000 metric tons. Over the past five years (2015/16-2019/20), the average annual excess supply has been 223,400 metric tons. During the same period, rice supply decreased by 2.9% every year, while rice demand also decreased by 2.0% every year (Table 1).

In addition, due to the accumulation of excess rice, the average year-end inventory in the last five years (2016-2020)[9] is 1,390,000 metric tons. It was well above the level of 800,000 metric tons which is the amount that the entire nation can consume for about two months based on the recommended inventory level by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization).

In particular, the annual consumption of rice per person is decreasing significantly. The annual rice consumption per person was 119.6 kg in 1990, but it was 56.9 kg in 2021, down more than half over the past 30 years. If this trend continues, there is a possibility that it will decrease to the range of around 50 kg or a little above in the next few years (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, rice production in 2021 was 3,882 thousand metric tons, up 10.7% from 3,507 thousand metric tons in 2020. Rice consumption is also continuously decreasing, making it difficult to resolve the oversupply in the short term.

Rice prices have been falling sharply recently

In June 2022, the nominal rice price was US$140.29 per 80 kg, down 18.5% from US$172.22 in June 2021, and the real rice price reflecting prices fell 23.2% during the same period. This downward trend in rice price of the produced stage has continued since June 2021 (Figure 2).

In addition, as the recent price of rice has fallen significantly, the rate of fluctuation in rice price at pre-harvest season (Jul.-Sep.) compared to the previous harvest period (Oct.-Dec.), that is, the seasonal amplitude, reached the highest record of –12.9% (Table 2). The reverse seasonal amplitude of such rice price acts as an incentive to sell excess inventory to the market, which eventually leads to a fall in rice price, adding to the management burden of agricultural cooperatives.[10]

RECENT RICE POLICY TRENDS

Rice market quarantine[11] three times this year

If the supply and demand control by market function was not smooth due to high yields, etc. after the abolition of the rice purchase system, the government intervened in the market through a rice supply and demand policy that purchases a certain amount of rice from the market.

A total of 2,162 thousand metric tons of rice had been quarantined from the market 14 times since 2005 and 2021, which is an average of 270,000 metric tons per year considering the 8 years the quarantine was implemented. That amount is 83.9% of the 322,000 metric tons of public reserves in 2020. The government's market intervention, or market quarantine supply and demand policy, is a policy tool to reduce the market supply afterwards in response to a drop in rice prices due to excessive rice supply. However, criticism has been raised that in the past, the rice market quarantine policy did not give a timely signal to the market because there were no clear standards for quantity and timing (Heo, Y.J., 2018).

Accordingly, the government institutionalized the rice supply and demand stabilization system by preparing the basis for the implementation of the preliminary rice market quarantine system through the revision of ‘the Grain Management Act’ in January 2020.[12] The preliminary rice market quarantine system is that preemptively quarantines excess production from the market after estimating appropriate production based on consumption prior to the harvest season. As rice price have fallen sharply recently, farmers’ organizations are demanding a revision of the law that mandates such a preliminary rice market quarantine system.

Recently, 3,882 thousand metric tons of rice production in 2021 exceeded the demand of 3,610 thousand metric tons (estimated) by about 270,000 metric tons. The government quarantined 270,000 metric tons twice in February and May this year. However, after twice market quarantine, the inventory of agricultural cooperatives still reached 596,000 metric tons in June 2022, up 73.8% from the average inventory of the past five years (343,000 metric tons) (Table 3). The government announced on July 1 that it would quarantine 100,000 metric tons of rice again in the market. Therefore, this year, the government purchased a total of 370,000 metric tons of rice produced last year on three occasions and quarantined it from the market.

The introduction of a new type of rice production adjustment system

A rice production adjustment system was implemented three times in 2003, 2011, and 2018 to solve the problem of oversupply by reducing the area of rice cultivation in advance (Table 4). It was temporarily operated for two or three years in consideration of changes in supply and demand at the time, such as inventory reduction and poor harvest, and the impact on the supply and demand of crops cultivated instead of rice.

Recently, the new government, which was launched in May 2022, will also push to introduce a new type of production-adjusted direct payment system to improve the self-sufficiency rate of strategic crops such as wheat and soybeans in response to the food security crisis.[13] This is aimed at preventing oversupply of rice, maintaining the base of rice self-sufficiency, and encouraging the production of strategic crops with low self-sufficiency.

Revitalizing the rice processed food industry using powdered rice

On June 8, the government announced ‘measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice’ to reduce dependence on wheat imports and solve the problem of excessive rice supply. The goal is to supply 200,000 metric tons of powdered rice, a type of rice exclusively for processing, by 2027, replacing 10% of the annual demand for about 2 million metric tons of flour. To this end, three major policy measures were set up, preparing a stable raw material supply system, supporting industrialization, and expanding the consumption base of rice processed food (Table 5).

(ⅰ) In order to prepare a stable supply system for raw materials, it plans to create 10 production complexes specializing in growing rice to make powdered rice by 2023 and 200 by 2027, supporting direct payments, and guiding farm technology. (ⅱ) To support industrialization, it operates a powdered rice supply system using a public reserves program, and develops strategic products using powdered rice by providing samples to food and milling companies and supporting R&D. (ⅲ) In order to expand the consumption base of processed rice products, it operates a public-private joint governance to establish an ecosystem of powdered rice industry, and supports the use of food certification in the industry and expansion of exports.

CONCLUSION

Rice prices have fallen sharply in recent years. This is a structural phenomenon caused by the oversupply of rice due to the productivity increase and consumption decrease in rice. Policies to stabilize rice prices are being requested, and in particular, it is necessary to set policy goals in stabilizing rice prices and farm management through achieving a balance of rice supply and demand. First, it should be mandatory to operate the preliminary rice market quarantine system, which has institutionalized in 2020. Until now, temporary market quarantine has been carried out in the event of oversupply, but the effect has not reached the expected level due to the time lag between the market situation and the policy-making process, that is, market confusion. If the quantity exceeding the expected demand is preemptively quarantined during the harvest season, it is believed that the market confusion can be reduced due to the resolution of the market uncertainties. Also, it is necessary to encourage farmers to use rice paddies in different ways other than only growing rice. If the paddies are used in various ways, such as to grow wheat, beans, or rice for being powdered by means of the strategic crop direct payment system, which is recently planned to be introduced by the government, it will contribute to reducing the production of edible rice and creating new demand for rice. In addition, various efforts are needed to increase rice demand. In particular, continuous policy support is important, such as the government’s measures to revitalize the rice processed food industry using powdered rice. Providing rice processed foods for group meals such as school or military meals would be a good option to increase the demand for the foods. The above policies intended to stabilize the rice supply and demand are difficult to achieve in a short time, considering the low flexibilities of paddies, in particular, in terms of responding to the external environment, the lack of alternative crops, and low incentives to encourage elderly farmers to grow crops other than rice. Therefore, it is time to study and discuss policies to stabilize rice farm management, that is, policies to buffer the risk of price fluctuations, so that the structural improvement of the rice industry can be soft-landed.

REFERENCES

Heo, Y.J., 2018, “Recent Rice Supply and Demand Trends and Policy Issues”, 『Rural and fishing communities, Environment』, The spring issue of 2018, pp.5-16.

Kim, H.H. et al, 2014,『A Study on the Improvement of Income Compensation Direct Payment System for rice farmers』, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Kim, J.H., 2010, “Rice Policy Direction in Republic of Korea”,『Food Storage and Processing Industries』, 9(2), pp.3-8.

Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs,『Grains Policy Data』, each year.

Park, D.K.·Lee, Y.Y., 2011, “Estimation of the Reduction Rate for the Improvement of Rice Reduction Statistics”,『Rural Economy』, 34(4), pp.41-58.

[1] US$ exchange rate standard as of June 30, 2022 (US$1=KRW1,298.4).

[2] As of 2021, the average agricultural income per farm is US$9,982. Rice income was estimated at US$3,279 among the agricultural income. Rice income (US$3,279) = Rice revenue (US$5,403) × Income rate (60.7%)

[3] The amount of rice purchased in 1993 accounted for 30.3% of rice production, but decreased to 14.2% in 2004.

[4] The actual amount of public reserves was 576,000 metric tons in 2005, 400,000 metric tons in 2008, 340,000 metric tons in 2011, 360,000 metric tons in 2015, 340,000 metric tons in 2018, 340,000 metric tons in 2019.

[5] (target price – rice price in harvest season) × 85% = fixed direct payment + variable direct payment. The target price was US$131.0 per 80kg at the time of introduction in 2005, increased to US$144.8 from 2013 to 2017, and increased to US$161.7 from 2018 to 2019. The unit price of fixed direct payment was continuously increased from US$462.1 per ha at the time of introduction in 2005, and US$770.2 was paid from 2015.

[6] The unit price of direct payment (variable payment +fixed payment) for rice was US$901.1 per ha, compared to US$385.1 for other crops.

[7] The proportion of small farmers (less than 1ha) receiving direct payments was only 29% of the total direct payments.

[8] The public direct payment system intends to provide subsidy to farmers to serve public purpose such as food safety and the conservation of environment and rural communities.

[9] 1,747,000 metric tons in 2016, 1,888,000 metric tons in 2017, 1,442,000 metric tons in 2018, 898,000 metric tons in 2019, 981,000 metric tons in 2020.

[10] The purchasing rice of agricultural cooperatives account for about 40% of all purchasing rice. In fact, RPC (Rice Processing Complex) in agricultural cooperatives had a profit and loss deficit of US$82.4 million in 2010, when the reverse seasonal amplitude was –7.9% (Heo, Y.J., 2018).

[11] Rice market quarantine is the government’s policy to reduce market supply by temporarily purchasing and storing up rice.

[12] According to Article 16 of ‘the Grain Management Act’, the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs shall establish and announce measures to stabilize the supply and demand of rice by October 15 every year.

[13] The grain self-sufficiency rate as of 2020 is 20.2%, and 3.2%, excluding rice. In particular, the self-sufficiency rate of wheat (0.5%), corn (0.7%), and soybeans (7.5%) is of great concern.