ABSTRACT

Rice is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Vietnam. Vietnam is one of the three major exporting countries in the world with total rice exports accounting for 13.6% of the world. Dong Thap is one of rice export provinces in the Mekong delta. Majority of producers are small scale, so the rice value chain in this province was very fragmented. The farmgate price is low and farmer’s income is not an incentive for farmer to produce rice. So the main question is the efficiency of rice value chain in Dong thap. This article uses the value chain analysis method to describe the current operations of rice value chain here and propose some solutions to improve the sustainability of rice value chain in the province.

Keywords: Rice, Value chain, Dong Thap.

BACKGROUND

Rice is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Vietnam. In 2020, Vietnam exported 6.25 million tons of rice, worth approximately US$3.12 billion, accounting for 7.6% of export turnover of agro-forestry-fishery (GSO, 2020). Vietnam is one of the three major exporting countries in the world with total rice exports accounting for 13.6% of the world. Vietnamese rice grains are present in more than 150 countries and territories. Not only that, rice is also a very important commodity for the livelihood of more than 15 million farming households and it plays an important role in ensuring national food security and contributes to ensuring world food security, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the Project on restructuring Vietnam's rice industry to 2025 and 2030, Vietnam is re-orienting the restructure of this industry in the direction of improving efficiency and sustainable development. At the same time, the Vietnamese people are exerting their efforts towards achieving the goal of fully meeting the needs of domestic consumption and improving the quality, nutritional value, and ensuring food hygiene and safety. This project is aiming to improve the efficiency of the rice value chain in terms of adaption and mitigation with climate change, and farmers' incomes improvement as well as the consumer’s welfare.

There are many studies on Vietnam's rice value chain, indicating that the linkage is still not strong, there is no closed rice export value chain. In particular, most of the studies on value chain just stopped at considering the relationship among the actors, calculating the added value between the agents, but have not studied the surrounding environment supporting the chain (like regulations, policies, etc.). In order to solve the above difficulties and with the aim towards improving and developing value chain of rice products, it is necessary to study the advantages and disadvantages of all actors participating in the rice value chain.

Dong Thap is a province which ranked 3rd in the country both in terms of rice cultivation area and rice output (GSO, 2020). The province also has favorable conditions in terms of soil and climate for agricultural development, especially in rice production. This is also the pioneer province in the country to implement the agricultural restructuring project since 2014. During the years of restructuring, the rice industry of Dong Thap has achieved many achievements: rice productivity, which increased by 140kg/ha; average profit reached US$557/ha/crop; 70% of cultivated area developed towards specialized production of high-quality seeds; and many safe rice production models attached with the consumption link which thus formed the value chain (Dong Thap DOIT, 2020). However, Dong Thap province is located in the area which is most heavily affected by climate change, in which saltwater intrusion and incidences of drought increase, greatly affecting the sustainable development of the province's rice industry (Dong Thap DARD, 2020). Another difficulty is that the production capacity of farmers is still low, and do not meet the requirements of product quality required by enterprises and the market (IPSARD, 2018). The linkage between actors in the value chain is loose, with rice farmers usually going through two main channels: traders and millers according to the principle of buying and selling and at market prices, which is done mainly orally without any contract or commitment (IPSARD, 2017). Post-harvest loss rate is high such as harvesting 3%, transporting 0.9%, drying 4.2%, preserving 2.6%, milling 3% (SIEAP, 2011). So, how is the current situation of the activities of the rice value chain actors in Dong Thap province? What are the advantages and disadvantages of actors in the chain? How effective is the rice production, business and export of the actors? What factors affect rice value chain in Dong Thap province? What are the solutions to improve and develop rice value chain locally in the near future? Those are the main questions that need to be resolved.

Therefore, it is necessary to carry out the "Study on rice value chain operations in Dong Thap province " in order to understand the bottlenecks in the development of rice value chain and offer solutions to promote rice efficiency and sustainable value chain.

RESEARCH METHODS

Analytical framework

Value chain in the narrow sense is made up of the activities within the same organization or company according to the analytical framework of Michael Porter (1985). Accordingly, a business can gain its competitive advantage by focusing on a strategy of low price or differentiation of its product or service, or a combination of both. The concept of value chain according to (Micheal Porter, 1985) only refers to the size of the enterprise.

Rappael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris (2000) suggest that value chain analysis shows that between activities in the different stages of the product life cycle exist a close relationship. These activities are not only established vertically but also interact with each other. Value chain in a broad sense is a sequence of production processes from inputs to output; it is an organized arrangement that connects and coordinates producers, production groups, businesses, and distributors in relation to a particular product; it is also an economic model in which there is a connection in the selection of appropriate products and technologies with the organization of relevant actors to access the market.

In this study, the author follows the value chain point of view in a broad sense. Accordingly, a value chain includes the many value-added links, the series of activities required to bring a product or service from conception, through the production stages. It has different effects on distribution to consumers.

Since 2010, in the book "Agricultural Value Chain Finance" of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), it defines: "Agricultural value chain includes a set of actors and activities that bring an agricultural product from production to the final consumer, whereby the value of the product is increased in each intermediate stage. A value chain can be a vertical link, or a network of independent actors involved in processing, packaging, storage, transportation, and distribution" (Calvin Miller and Linda Jones, 2010).

Data and research methods

- This research work includes the collection of secondary data on information and data related to research products for the period 2014-2020. Secondary data is also the basis for selecting research samples (sites);

- Investigation of primary data consists of a questionnaire that responds to all information and metrics relevant to production and consumption, logistics, risk and risk management, and support of all actor’s participation in the chain, relevant policies in 2021. Research to select the 2014 timeline is since the People's Committee of Dong Thap province issued Decision No. 591/QD-UBND approving the project "Reconstruction" of Agricultural Structure of Dong Thap province" on June 30, 2014, whereby, the rice industry is oriented as one of the key agricultural products of the province.

- The author chooses to survey farmers, cooperatives, and traders in the three districts of Dong Thap Muoi, Cao Lanh and Thanh Binh districts, which have large production areas and commercial activities. Significantly, in addition, other subjects include people involved in milling establishments, rice trading and exporting enterprises in Dong Thap province.

- The sample observation (structure of all actors, facilitators and experts interviewed) should be large enough to ensure representation and generalization. Representativeness of the sample (study area) selected using representative criteria (such as area, output or income criteria) and the selected sample having at least a representative criterion as from 50% or more of the total sample (for example, the three districts selected for the study have an area and rice production that account for 56% and 62% of the province, respectively).

RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The influence of some weather factors on the rice chain of Dong Thap province

Weather changes may reduce the quality of harvested rice, partly affecting other factors in the rice export value chain, but this effect compared to the effect that farmers suffer is insignificant. From the research results of "The model of agricultural production linkage in the Mekong Delta in the context of market competition and climate change response" (Nguyen Van Sanh, 2018), a cause-and-effect relationship has been established for extreme weather and its impact on production and consumption of rice. For farmers: extreme weather causes the development of many pests and diseases that affect productivity, reduces output and increase production costs, reduces farmers' income and production capacity according to the ecosystem. Traders often have a short time to move rice and have milling facilities, and exporters often have storage facilities, so they can limit the weather’s influence.

One of the advantages of climate and weather in Dong Thap for agricultural production development is: lots of sunshine, abundant radiant energy, on average (75 - 80 Kcal/cm2/year). The temperature is consistently high all-year round (average of months of the year is from 25oC - 27oC). But due to the influence of global climate change, many climatic factors in Dong Thap have changed significantly. Observed air temperature tends to increase typically. According to 15 years' observation data, the average temperature increases by 0.35 - 0.45oC.

The annual rainfall of Dong Thap province is quite high, averaging 1,100-1,600 mm/year, the average number of rainy days is 108 - 202 days/year. However, the rainfall is unevenly distributed throughout the year and months. In the rainy season, there are often concentrated and intense rains that cause soil erosion, washing and discoloration in areas with high terrain and flooding in lowland areas, whereas in the dry season water resources are scarce, causing prolonged drought.

Over the past 20 years, rainfall tends to decrease, which leads to increased saltwater intrusion. In particular, in the year 2015 - 2016, there was a record-long drought period and recorded heavy rains for the past 50 years.

Climate change with sea level rise, temperature rise, drought, and increasingly severe natural disasters affecting rice yield and quality, is also the most difficult challenge for rice producers. For example, in the first half of 2020, the Mekong Delta experienced a historic drought, affecting hundreds of thousands of hectares of rice cultivation in the provinces near the sea mouth. In the previous year, there were floods again, causing many rice cultivation areas to be flooded when nearing harvest, causing great damage to farmers.

Characteristics of actors participating in the rice value chain in Dong Thap province

The province has implemented technical solutions to reduce production costs, increase mechanization, all of which contributes to reducing costs and increasing profits compared to traditional processes. The situation of consumption association has progressed well with the volume consumed by companies increasing gradually over the years.

In addition, the province also implemented pilot production of 800 hectares of rice in the direction of an organic, high-tech application model of organic rice production, and implemented hi-tech agricultural production models such as information technology application, information in rice production, organic rice production associated with food safety and hygiene, smart rice farming adapting to climate change, reducing the number of seed sown, reducing production costs, flattening fields with Laser beam, and rice transplanter application.

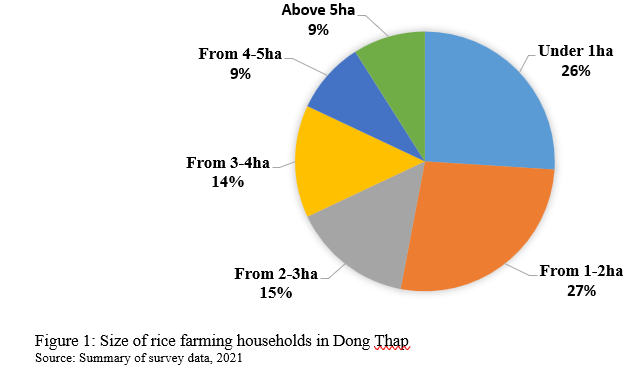

Up to 49% of surveyed households have only 2 household workers engaged in rice cultivation, 18% of households with 3 laborers engaged in rice cultivation and 19% of households with 4 laborers engaged in rice cultivation. The hiring of direct laborers to grow rice is very common in the locality. The stage most often employed by people is reaping with 99% of the households, followed by the tillage stage with 95% of the households agreeing, the sowing and spraying stage with 91% and the spreading stage. Up to 83% of households hire laborers. Households that do not hire laborers mostly have a small area of rice land (under 2 hectares) and a large number of people of working age.

Smallholder production, lack of linkages in input and output management, is a favorable condition for the existence of market intermediaries, widening the gap among farmers and processors, traders and the market. The majority of rice farmers still consume fresh rice through traders instead of signing contracts directly with processing and exporting enterprises despite having a policy of consuming agricultural products under contracts and incentive policies and production linkages between enterprises and farmers.

The fact that 100% of surveyed farmers sell fresh rice indicates that there is a clear division of labor in the value chain of rice production - processing - trading.

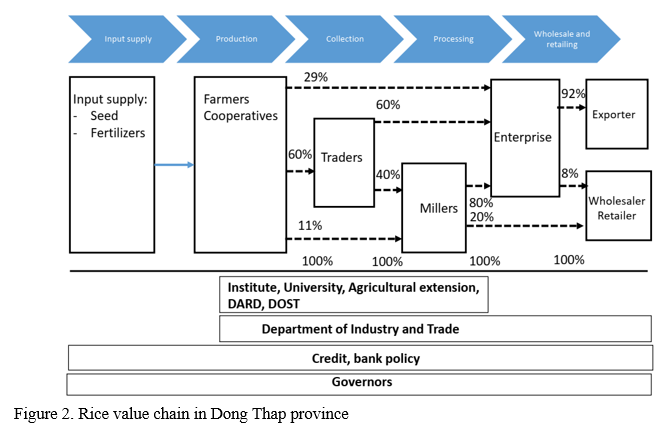

Diagram and description of rice value chain in Dong Thap province

According to survey results, the rice export value chain of Dong Thap province (only for rice products for export, excluding processed rice products such as rice flour, vermicelli and other rice-based products) which are described in Figure 2. Thus, the rice export value chain in Dong Thap province includes 3 main distribution channels:

Channel 1: Farmers è Traders è Milling plans è Exporting enterprises (accounting for about 60% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

Channel 1 is the longest channel and also the most popular consumption channel in the rice export value chain in the Mekong Delta in general and Dong Thap in particular, which accounts for about 60% of the total rice production in the whole chain. Although there are still many limitations in both quality management and market regulation, it is undeniable that this traditional consumption channel still plays an important role in collecting rice from millions of farmers in Dong Thap, and the Mekong Delta.

In this channel, consumption through traders is riskier for both farmers as well as Vietnam's rice export value chain. Most traders buy fresh rice directly from farmers without contracts, or only verbally. Before harvesting, traders will go to farmers' rice fields to see the quality of the rice and negotiate the price. Traders often do not care about rice production according to sustainable or unsustainable processes, whether or not they save inputs, but only care about the quality of rice at the time of harvest. Rice prices are negotiated according to market prices, but traders still have the right to decide, especially in the middle of the harvest season, when the market price of rice slows down. Because traders purchase rice from different areas in the Mekong Delta and their scope of activities can change from year to year, it is difficult to control and enumerate the quantity and activities of traders in an adequate and cost-effective manner. Many traders not only buy rice but also buy other agricultural products or do other jobs, so it is difficult to reach them, especially during the rice harvest season. Therefore, this is the most difficult factor to study in the rice export value chain.

The biggest drawback of traders is that they cannot guarantee the traceability and purity of the rice. Because a trader buys rice from many different fields, traceability is almost impossible. The purchase of rice varieties with similar appearance at the same time makes Vietnamese rice have a low percentage of purity, reducing the quality of exported rice. In addition, the cost of intermediaries between actors is also a problem that makes the rice export value chain less efficient.

After collecting rice from farmers, traders can consume it in the following ways: (1) sell to millers/exporters that have mills; (2) rice is milled and sold to polishing/exporting factories; and (3) rice is milled, polished, and then sold to wholesalers/retailers and exporters.

Milling facilities will process rice according to orders received from export enterprises and domestic demand. Export enterprises, after purchasing from milling establishments, will undertake the export stage (offering goods, transporting, carrying out procedures, etc.). If exporters have their own milling facilities, they can also purchase rice from traders for self-processing.

Because traders have the ability to collect flexibly, most of the company's exported rice is still purchased through this agent. Rice purchased from production links with farmers is usually only used by businesses for safe/sustainable rice products sold domestically or premium rice for export. The market capacity of this product is not high, so the production linkage has not been applied to export rice. Besides, linking production with farmers requires a large investment and is also the reason why many businesses have not yet boldly deployed linkages and feel more active with the traditional purchasing channel through traders.

Channel 2: Farmers è Exporters (accounting for about 29% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

This channel is the shortest channel in the rice export value chain in Dong Thap, with the participation of 3 actors: farmers, citizens and export enterprises. In this channel, exporters directly sign contracts (called offtake contracts) with farmers through cooperatives, thus limiting the intermediary stages. Some typical enterprises implementing the model of association with farmers in Dong Thap province include: Loc Troi Group; Southern Seed Company, and Dong Thap Food Company. Usually, companies buy rice with higher requirements, including purebred varieties, rice not mixed with other types, rice spillage rate, etc. These standards are different for each company. In the case of Loc Troi Group, farmers must apply the correct technical process, with the company's staff to supervise from sowing to harvesting. This is the short market channel and is said to be the most effective consumption channel both in terms of economy, as well as in terms of quality control and origin.

Although rice consumption through channel 2 brings high efficiency to both farmers and businesses, the implementation of contracts between rice farmers and businesses still faces many difficulties and obstacles in practice. This is a big barrier for promoting production linkages between farmers and businesses. Difficulties that businesses often face in implementing linkages with farmers include: (i) the output market is not stable, so it is not possible to consume a larger amount of rice; (ii) the supply of input materials, the organization of a complete linkage chain requires large investment capital; (iii) the production scale of households is still small, the capacity of cooperatives in coordinating production-consumption linkages is still limited, so to produce large fields need the consent of a large number of households, requires a lot of time and effort. Once the link has been formed, the guidance and supervision of the production process of the number of households is also a difficulty that enterprises must solve. On the farmers side, price is still the determining factor for their output. For many farmers, in order for them to accept farming according to their own requirements, the committed price is much higher than the market, making it difficult for businesses. In addition, most farmers are of the small-scale type, so they pay little attention to safe production processes and there are few cooperatives that have the capacity to organize and collect farmers' rice to supply them to farmers enterprises.

Channel 3: Farmers è Milling plants è Exporters (accounting for about 11% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

In this channel, three actors participate in the rice export value chain including: farmers, milling establishments and export enterprises. The proportion of rice consumption of this channel in total rice consumption in Dong Thap is considered to be quite low, accounting for only 11% of the total rice output of the whole chain, because there are not many milling establishments that have the capacity to collect directly from farmers.

Analysis of the value distribution of actors in the rice value chain of Dong Thap province

The study focuses on analyzing the value stream of actors participating in the rice export value chain of Dong Thap province through Channel 1 (Farmer è Tradersè Milling plantsè Exporters) and Channel 2 (Farmer è Exporters)

Channel 1: Among the actors participating in the value chain of the rice industry, farmers are the actors with a highest proportion of the production cost (55.8%) and the highest proportion of profit (73.5%) among value chain agents. Meanwhile, the traders only have to invest 8.5% of the cost in the rice export value chain but receive a profit of 13.4% of the value chain's profit. Compared to farmers, traders have the ability to avoid risks more flexibly and still receive a good proportion of profits. Exporters and millers have a much lower proportion of profits than costs. Enterprises have a proportion of profit accounting for 7% of the total profit of the value chain but bear 21.2% of the total additional costs of the chain. Millers have a lower profit ratio of 6.1% than cost ratio of 14.6%, but the by-product surcharge can help offset this correlation.

Channel 2: Unlike channel 1, the distribution of costs between the two agents’ farmers-enterprises is more balanced with the ratio of 43.7: 56.3. But the distribution of profits between these two agents is quite different from 82.6; 17.4 (more than 4 times). This shows that in terms of economic efficiency, enterprises are responsible for large costs and low profit rates per kg of rice, showing that enterprises bear more risks than farmers.

With both channels above, although farmers always account for the highest proportion of profits in the rice export value chain, due to the small scale of production (2ha/household on average), the profit that a single rice farmer makes is low, much lower than other actors in the chain. According to the survey, each farmer only produces on average of about 40 tons of rice per year while agents such as traders, millers, and consumers consume thousands or tens of thousands of tons per year. Exports also consume hundreds of thousands of tons per year. Because of the difference in scale, although the profit per kg of rice of other actors is lower than that of farmers, their total profit is much higher than that of a single rice farmer. It can be seen that the profit distribution of the rice export value chain is influenced by the production scale, the production and business cycle, and the power to operate the chain of each actor.

Besides, the climate and weather risks of farmers are very high, making them always face losses, even loss of money due to crop failure. Despite high risks, farmers do not have much power in operating the chain and are subject to price regulation from other individuals.

CONCLUSION

In order to respond to climate change, the Dong Thap agricultural sector needs to develop a relatively accurate scenario and plan to respond to climate change. On the other hand, it is necessary to complete the irrigation system, organize the management with scientific operation; at the same time arrange the appropriate crop structure and planting season.

Farmers are the subject that bears the most risks, for both subjective and objective reasons. On the intrinsic side, the small production scale and inaccurate profit calculation make the income from rice farming of farmers more precarious and smaller compared to other actors in the value chain. Regarding objective conditions, besides existing risks such as weather, epidemics, traditional processing processes and the distribution of actors in the value chain according to current popular channels, the value of South Vietnamese rice grains has not reached its full potential. The value of the entire export value chain is greatly influenced by the export price that enterprises negotiate. Farmers bear the largest proportion of costs but only receive a small portion of profits and do not have the right to negotiate prices in the chain, so they bear a lot of market risks.

Traders are an active part of the value chain but need to be placed under stricter management. Until now, traders are still the agents that connect the entire value chain, from farmers to exporters, with relatively small operating profit margins due to strong competition. The condition of traders' facilities is greatly affecting the quality of rice due to the long transport time, poor storage conditions of rice on boats, and rice being processed at many different locations leading to the quality is not equal. However, objectively, traders do not actively improve and manage quality because food and export businesses are the focal point of product quality requirements, most of them are still interested in whiteness, clarity, weight, so the current process that traders are implementing still meets the requirements.

Small private mills will face strong competition from large-scale processors in the future. However, at present, milling plants are still important supply satellites for food businesses, exporters and retailers, as well as providing services for traders. Therefore, in the short term, this will be the key stage to innovate processing technology and change the processing process in the direction of increasing quality, value, and reducing loss, thereby creating a breakthrough in the long-term for the rice industry in Vietnam.

The development of large processing-business enterprises with a closed, continuous processing system and direct links with farmers has been an important trend in the rice industry in the past 5 years. Objectively, Decree 109 on business and export conditions for rice has a decisive influence on the formation of this trend. However, it is worth noting that many large enterprises in this trend are those outside the industry, having traditional business fields outside the rice industry (Loc Troi, Cam Nguyen...). Due to the initial investment capital, large regular operating costs and high cash liquidity in the harvest season, businesses outside the industry have other business lines to compensate for rice purchasing, processing, and trading activities which have a great advantage to lead this trend.

Although cooperatives and cooperative economic organizations are not represented in the current popular value chain, with the emergence of farmer-enterprise cooperation, cooperative economic organizations are expected to play a more active role in the future. However, in order to develop in this direction, cooperatives need to improve their capacity to organize farmers and collect rice more to create trust for investment enterprises. At the same time, cooperatives also need to improve their negotiation ability, representing farmers to discuss with businesses to reach an agreement that is beneficial for both sides, creating motivation for farmers to participate in the association.

To meet the increasing quality requirements of the world market, as well as to cope with increasing competition from emerging rice export countries such as Cambodia and Myanmar, the strengthening of linkages between actors in the rice export value chain is the inevitable direction.

REFERENCES

Calvin Miller and Linda Jones (2010). Agricultural Value Chain Finance. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Dong Thap Provincial Statistics Office (2021). Dong Thap Province Statistical Yearbook 2020.

Dao The Anh (2017). Developing the value chain of Agri-food products.

Eaton, C and Shepherd, A. (2001). Contract Farming: Partnerships for Growth. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

GTZ (2007). Value Links Manual: Value Links Manual: The Methodology of Value Chain Promotion.

Michael Porter (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.

Nguyen Quoc Nghi. (2019). Solution to complete rice value chain in Phong Dien district, Can Tho city. Science Journal of Can Tho University, vol. 55, No. 1D (2019), pp. 101-108.

Nguyen Van Sanh (2018). Model of agricultural production linkage in the Mekong Delta in the context of market competition and climate change response. Regional workshop of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development held in Can Tho.

Vietnam Sub-Institute of Electromechanical and Postharvest Technology. (2011). Investigation results on post-harvest losses.

Rappael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris (2000). A Handbook for Value Chain Research.

Rerkasem, B. (2017). The Rice Value Chain: A Case Study of Thai Rice. ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (2017) Vol 4 No.1.

Department of Industry and Trade of Dong Thap province. (2020). Production and consumption of agricultural products of Dong Thap in the period 2014-2020.

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development of Dong Thap province. (2020). Report on implementation of agricultural restructuring in Dong Thap province, period 2016-2020. Dong Thap.

General Statistics Office. (2019). Results of the 2019 population and housing census, Hanoi.

General Statistics Office. (2020, 11-24). Statistics on agriculture, forestry and fishery. https://www.gso.gov.vn/nong-lam-nghiep-va-thuy-san/

Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development (2017). Report on the value chain of the rice industry in Dong Thap.

Institute of Policy and Strategy for Rural Development (2018). Status of sustainable rice farming in Dong Thap province.

Central Institute for Economic Management. (2017). Institutional review report on rice value chain. Hanoi.

Vo Thi Thanh Loc and Nguyen Phu Son. (2011). Rice value chain analysis in the Mekong Delta. Journal of Science 2011: 19a.

Vo Van Thanh, Le Ngoc Quynh Lam and Nguyen Thi Kim Pho. (2015). Situation of rice supply chain in the Mekong Delta. Science and technology development journal, volume 18, Q2-2015 issue.

Rice Value Chain Operation in Dong Thap Province

ABSTRACT

Rice is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Vietnam. Vietnam is one of the three major exporting countries in the world with total rice exports accounting for 13.6% of the world. Dong Thap is one of rice export provinces in the Mekong delta. Majority of producers are small scale, so the rice value chain in this province was very fragmented. The farmgate price is low and farmer’s income is not an incentive for farmer to produce rice. So the main question is the efficiency of rice value chain in Dong thap. This article uses the value chain analysis method to describe the current operations of rice value chain here and propose some solutions to improve the sustainability of rice value chain in the province.

Keywords: Rice, Value chain, Dong Thap.

BACKGROUND

Rice is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Vietnam. In 2020, Vietnam exported 6.25 million tons of rice, worth approximately US$3.12 billion, accounting for 7.6% of export turnover of agro-forestry-fishery (GSO, 2020). Vietnam is one of the three major exporting countries in the world with total rice exports accounting for 13.6% of the world. Vietnamese rice grains are present in more than 150 countries and territories. Not only that, rice is also a very important commodity for the livelihood of more than 15 million farming households and it plays an important role in ensuring national food security and contributes to ensuring world food security, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the Project on restructuring Vietnam's rice industry to 2025 and 2030, Vietnam is re-orienting the restructure of this industry in the direction of improving efficiency and sustainable development. At the same time, the Vietnamese people are exerting their efforts towards achieving the goal of fully meeting the needs of domestic consumption and improving the quality, nutritional value, and ensuring food hygiene and safety. This project is aiming to improve the efficiency of the rice value chain in terms of adaption and mitigation with climate change, and farmers' incomes improvement as well as the consumer’s welfare.

There are many studies on Vietnam's rice value chain, indicating that the linkage is still not strong, there is no closed rice export value chain. In particular, most of the studies on value chain just stopped at considering the relationship among the actors, calculating the added value between the agents, but have not studied the surrounding environment supporting the chain (like regulations, policies, etc.). In order to solve the above difficulties and with the aim towards improving and developing value chain of rice products, it is necessary to study the advantages and disadvantages of all actors participating in the rice value chain.

Dong Thap is a province which ranked 3rd in the country both in terms of rice cultivation area and rice output (GSO, 2020). The province also has favorable conditions in terms of soil and climate for agricultural development, especially in rice production. This is also the pioneer province in the country to implement the agricultural restructuring project since 2014. During the years of restructuring, the rice industry of Dong Thap has achieved many achievements: rice productivity, which increased by 140kg/ha; average profit reached US$557/ha/crop; 70% of cultivated area developed towards specialized production of high-quality seeds; and many safe rice production models attached with the consumption link which thus formed the value chain (Dong Thap DOIT, 2020). However, Dong Thap province is located in the area which is most heavily affected by climate change, in which saltwater intrusion and incidences of drought increase, greatly affecting the sustainable development of the province's rice industry (Dong Thap DARD, 2020). Another difficulty is that the production capacity of farmers is still low, and do not meet the requirements of product quality required by enterprises and the market (IPSARD, 2018). The linkage between actors in the value chain is loose, with rice farmers usually going through two main channels: traders and millers according to the principle of buying and selling and at market prices, which is done mainly orally without any contract or commitment (IPSARD, 2017). Post-harvest loss rate is high such as harvesting 3%, transporting 0.9%, drying 4.2%, preserving 2.6%, milling 3% (SIEAP, 2011). So, how is the current situation of the activities of the rice value chain actors in Dong Thap province? What are the advantages and disadvantages of actors in the chain? How effective is the rice production, business and export of the actors? What factors affect rice value chain in Dong Thap province? What are the solutions to improve and develop rice value chain locally in the near future? Those are the main questions that need to be resolved.

Therefore, it is necessary to carry out the "Study on rice value chain operations in Dong Thap province " in order to understand the bottlenecks in the development of rice value chain and offer solutions to promote rice efficiency and sustainable value chain.

RESEARCH METHODS

Analytical framework

Value chain in the narrow sense is made up of the activities within the same organization or company according to the analytical framework of Michael Porter (1985). Accordingly, a business can gain its competitive advantage by focusing on a strategy of low price or differentiation of its product or service, or a combination of both. The concept of value chain according to (Micheal Porter, 1985) only refers to the size of the enterprise.

Rappael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris (2000) suggest that value chain analysis shows that between activities in the different stages of the product life cycle exist a close relationship. These activities are not only established vertically but also interact with each other. Value chain in a broad sense is a sequence of production processes from inputs to output; it is an organized arrangement that connects and coordinates producers, production groups, businesses, and distributors in relation to a particular product; it is also an economic model in which there is a connection in the selection of appropriate products and technologies with the organization of relevant actors to access the market.

In this study, the author follows the value chain point of view in a broad sense. Accordingly, a value chain includes the many value-added links, the series of activities required to bring a product or service from conception, through the production stages. It has different effects on distribution to consumers.

Since 2010, in the book "Agricultural Value Chain Finance" of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), it defines: "Agricultural value chain includes a set of actors and activities that bring an agricultural product from production to the final consumer, whereby the value of the product is increased in each intermediate stage. A value chain can be a vertical link, or a network of independent actors involved in processing, packaging, storage, transportation, and distribution" (Calvin Miller and Linda Jones, 2010).

Data and research methods

RESEARCH RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The influence of some weather factors on the rice chain of Dong Thap province

Weather changes may reduce the quality of harvested rice, partly affecting other factors in the rice export value chain, but this effect compared to the effect that farmers suffer is insignificant. From the research results of "The model of agricultural production linkage in the Mekong Delta in the context of market competition and climate change response" (Nguyen Van Sanh, 2018), a cause-and-effect relationship has been established for extreme weather and its impact on production and consumption of rice. For farmers: extreme weather causes the development of many pests and diseases that affect productivity, reduces output and increase production costs, reduces farmers' income and production capacity according to the ecosystem. Traders often have a short time to move rice and have milling facilities, and exporters often have storage facilities, so they can limit the weather’s influence.

One of the advantages of climate and weather in Dong Thap for agricultural production development is: lots of sunshine, abundant radiant energy, on average (75 - 80 Kcal/cm2/year). The temperature is consistently high all-year round (average of months of the year is from 25oC - 27oC). But due to the influence of global climate change, many climatic factors in Dong Thap have changed significantly. Observed air temperature tends to increase typically. According to 15 years' observation data, the average temperature increases by 0.35 - 0.45oC.

The annual rainfall of Dong Thap province is quite high, averaging 1,100-1,600 mm/year, the average number of rainy days is 108 - 202 days/year. However, the rainfall is unevenly distributed throughout the year and months. In the rainy season, there are often concentrated and intense rains that cause soil erosion, washing and discoloration in areas with high terrain and flooding in lowland areas, whereas in the dry season water resources are scarce, causing prolonged drought.

Over the past 20 years, rainfall tends to decrease, which leads to increased saltwater intrusion. In particular, in the year 2015 - 2016, there was a record-long drought period and recorded heavy rains for the past 50 years.

Climate change with sea level rise, temperature rise, drought, and increasingly severe natural disasters affecting rice yield and quality, is also the most difficult challenge for rice producers. For example, in the first half of 2020, the Mekong Delta experienced a historic drought, affecting hundreds of thousands of hectares of rice cultivation in the provinces near the sea mouth. In the previous year, there were floods again, causing many rice cultivation areas to be flooded when nearing harvest, causing great damage to farmers.

Characteristics of actors participating in the rice value chain in Dong Thap province

The province has implemented technical solutions to reduce production costs, increase mechanization, all of which contributes to reducing costs and increasing profits compared to traditional processes. The situation of consumption association has progressed well with the volume consumed by companies increasing gradually over the years.

In addition, the province also implemented pilot production of 800 hectares of rice in the direction of an organic, high-tech application model of organic rice production, and implemented hi-tech agricultural production models such as information technology application, information in rice production, organic rice production associated with food safety and hygiene, smart rice farming adapting to climate change, reducing the number of seed sown, reducing production costs, flattening fields with Laser beam, and rice transplanter application.

Up to 49% of surveyed households have only 2 household workers engaged in rice cultivation, 18% of households with 3 laborers engaged in rice cultivation and 19% of households with 4 laborers engaged in rice cultivation. The hiring of direct laborers to grow rice is very common in the locality. The stage most often employed by people is reaping with 99% of the households, followed by the tillage stage with 95% of the households agreeing, the sowing and spraying stage with 91% and the spreading stage. Up to 83% of households hire laborers. Households that do not hire laborers mostly have a small area of rice land (under 2 hectares) and a large number of people of working age.

Smallholder production, lack of linkages in input and output management, is a favorable condition for the existence of market intermediaries, widening the gap among farmers and processors, traders and the market. The majority of rice farmers still consume fresh rice through traders instead of signing contracts directly with processing and exporting enterprises despite having a policy of consuming agricultural products under contracts and incentive policies and production linkages between enterprises and farmers.

The fact that 100% of surveyed farmers sell fresh rice indicates that there is a clear division of labor in the value chain of rice production - processing - trading.

Diagram and description of rice value chain in Dong Thap province

According to survey results, the rice export value chain of Dong Thap province (only for rice products for export, excluding processed rice products such as rice flour, vermicelli and other rice-based products) which are described in Figure 2. Thus, the rice export value chain in Dong Thap province includes 3 main distribution channels:

Channel 1: Farmers è Traders è Milling plans è Exporting enterprises (accounting for about 60% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

Channel 1 is the longest channel and also the most popular consumption channel in the rice export value chain in the Mekong Delta in general and Dong Thap in particular, which accounts for about 60% of the total rice production in the whole chain. Although there are still many limitations in both quality management and market regulation, it is undeniable that this traditional consumption channel still plays an important role in collecting rice from millions of farmers in Dong Thap, and the Mekong Delta.

In this channel, consumption through traders is riskier for both farmers as well as Vietnam's rice export value chain. Most traders buy fresh rice directly from farmers without contracts, or only verbally. Before harvesting, traders will go to farmers' rice fields to see the quality of the rice and negotiate the price. Traders often do not care about rice production according to sustainable or unsustainable processes, whether or not they save inputs, but only care about the quality of rice at the time of harvest. Rice prices are negotiated according to market prices, but traders still have the right to decide, especially in the middle of the harvest season, when the market price of rice slows down. Because traders purchase rice from different areas in the Mekong Delta and their scope of activities can change from year to year, it is difficult to control and enumerate the quantity and activities of traders in an adequate and cost-effective manner. Many traders not only buy rice but also buy other agricultural products or do other jobs, so it is difficult to reach them, especially during the rice harvest season. Therefore, this is the most difficult factor to study in the rice export value chain.

The biggest drawback of traders is that they cannot guarantee the traceability and purity of the rice. Because a trader buys rice from many different fields, traceability is almost impossible. The purchase of rice varieties with similar appearance at the same time makes Vietnamese rice have a low percentage of purity, reducing the quality of exported rice. In addition, the cost of intermediaries between actors is also a problem that makes the rice export value chain less efficient.

After collecting rice from farmers, traders can consume it in the following ways: (1) sell to millers/exporters that have mills; (2) rice is milled and sold to polishing/exporting factories; and (3) rice is milled, polished, and then sold to wholesalers/retailers and exporters.

Milling facilities will process rice according to orders received from export enterprises and domestic demand. Export enterprises, after purchasing from milling establishments, will undertake the export stage (offering goods, transporting, carrying out procedures, etc.). If exporters have their own milling facilities, they can also purchase rice from traders for self-processing.

Because traders have the ability to collect flexibly, most of the company's exported rice is still purchased through this agent. Rice purchased from production links with farmers is usually only used by businesses for safe/sustainable rice products sold domestically or premium rice for export. The market capacity of this product is not high, so the production linkage has not been applied to export rice. Besides, linking production with farmers requires a large investment and is also the reason why many businesses have not yet boldly deployed linkages and feel more active with the traditional purchasing channel through traders.

Channel 2: Farmers è Exporters (accounting for about 29% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

This channel is the shortest channel in the rice export value chain in Dong Thap, with the participation of 3 actors: farmers, citizens and export enterprises. In this channel, exporters directly sign contracts (called offtake contracts) with farmers through cooperatives, thus limiting the intermediary stages. Some typical enterprises implementing the model of association with farmers in Dong Thap province include: Loc Troi Group; Southern Seed Company, and Dong Thap Food Company. Usually, companies buy rice with higher requirements, including purebred varieties, rice not mixed with other types, rice spillage rate, etc. These standards are different for each company. In the case of Loc Troi Group, farmers must apply the correct technical process, with the company's staff to supervise from sowing to harvesting. This is the short market channel and is said to be the most effective consumption channel both in terms of economy, as well as in terms of quality control and origin.

Although rice consumption through channel 2 brings high efficiency to both farmers and businesses, the implementation of contracts between rice farmers and businesses still faces many difficulties and obstacles in practice. This is a big barrier for promoting production linkages between farmers and businesses. Difficulties that businesses often face in implementing linkages with farmers include: (i) the output market is not stable, so it is not possible to consume a larger amount of rice; (ii) the supply of input materials, the organization of a complete linkage chain requires large investment capital; (iii) the production scale of households is still small, the capacity of cooperatives in coordinating production-consumption linkages is still limited, so to produce large fields need the consent of a large number of households, requires a lot of time and effort. Once the link has been formed, the guidance and supervision of the production process of the number of households is also a difficulty that enterprises must solve. On the farmers side, price is still the determining factor for their output. For many farmers, in order for them to accept farming according to their own requirements, the committed price is much higher than the market, making it difficult for businesses. In addition, most farmers are of the small-scale type, so they pay little attention to safe production processes and there are few cooperatives that have the capacity to organize and collect farmers' rice to supply them to farmers enterprises.

Channel 3: Farmers è Milling plants è Exporters (accounting for about 11% of the total rice production of the whole chain)

In this channel, three actors participate in the rice export value chain including: farmers, milling establishments and export enterprises. The proportion of rice consumption of this channel in total rice consumption in Dong Thap is considered to be quite low, accounting for only 11% of the total rice output of the whole chain, because there are not many milling establishments that have the capacity to collect directly from farmers.

Analysis of the value distribution of actors in the rice value chain of Dong Thap province

The study focuses on analyzing the value stream of actors participating in the rice export value chain of Dong Thap province through Channel 1 (Farmer è Tradersè Milling plantsè Exporters) and Channel 2 (Farmer è Exporters)

Channel 1: Among the actors participating in the value chain of the rice industry, farmers are the actors with a highest proportion of the production cost (55.8%) and the highest proportion of profit (73.5%) among value chain agents. Meanwhile, the traders only have to invest 8.5% of the cost in the rice export value chain but receive a profit of 13.4% of the value chain's profit. Compared to farmers, traders have the ability to avoid risks more flexibly and still receive a good proportion of profits. Exporters and millers have a much lower proportion of profits than costs. Enterprises have a proportion of profit accounting for 7% of the total profit of the value chain but bear 21.2% of the total additional costs of the chain. Millers have a lower profit ratio of 6.1% than cost ratio of 14.6%, but the by-product surcharge can help offset this correlation.

Channel 2: Unlike channel 1, the distribution of costs between the two agents’ farmers-enterprises is more balanced with the ratio of 43.7: 56.3. But the distribution of profits between these two agents is quite different from 82.6; 17.4 (more than 4 times). This shows that in terms of economic efficiency, enterprises are responsible for large costs and low profit rates per kg of rice, showing that enterprises bear more risks than farmers.

With both channels above, although farmers always account for the highest proportion of profits in the rice export value chain, due to the small scale of production (2ha/household on average), the profit that a single rice farmer makes is low, much lower than other actors in the chain. According to the survey, each farmer only produces on average of about 40 tons of rice per year while agents such as traders, millers, and consumers consume thousands or tens of thousands of tons per year. Exports also consume hundreds of thousands of tons per year. Because of the difference in scale, although the profit per kg of rice of other actors is lower than that of farmers, their total profit is much higher than that of a single rice farmer. It can be seen that the profit distribution of the rice export value chain is influenced by the production scale, the production and business cycle, and the power to operate the chain of each actor.

Besides, the climate and weather risks of farmers are very high, making them always face losses, even loss of money due to crop failure. Despite high risks, farmers do not have much power in operating the chain and are subject to price regulation from other individuals.

CONCLUSION

In order to respond to climate change, the Dong Thap agricultural sector needs to develop a relatively accurate scenario and plan to respond to climate change. On the other hand, it is necessary to complete the irrigation system, organize the management with scientific operation; at the same time arrange the appropriate crop structure and planting season.

Farmers are the subject that bears the most risks, for both subjective and objective reasons. On the intrinsic side, the small production scale and inaccurate profit calculation make the income from rice farming of farmers more precarious and smaller compared to other actors in the value chain. Regarding objective conditions, besides existing risks such as weather, epidemics, traditional processing processes and the distribution of actors in the value chain according to current popular channels, the value of South Vietnamese rice grains has not reached its full potential. The value of the entire export value chain is greatly influenced by the export price that enterprises negotiate. Farmers bear the largest proportion of costs but only receive a small portion of profits and do not have the right to negotiate prices in the chain, so they bear a lot of market risks.

Traders are an active part of the value chain but need to be placed under stricter management. Until now, traders are still the agents that connect the entire value chain, from farmers to exporters, with relatively small operating profit margins due to strong competition. The condition of traders' facilities is greatly affecting the quality of rice due to the long transport time, poor storage conditions of rice on boats, and rice being processed at many different locations leading to the quality is not equal. However, objectively, traders do not actively improve and manage quality because food and export businesses are the focal point of product quality requirements, most of them are still interested in whiteness, clarity, weight, so the current process that traders are implementing still meets the requirements.

Small private mills will face strong competition from large-scale processors in the future. However, at present, milling plants are still important supply satellites for food businesses, exporters and retailers, as well as providing services for traders. Therefore, in the short term, this will be the key stage to innovate processing technology and change the processing process in the direction of increasing quality, value, and reducing loss, thereby creating a breakthrough in the long-term for the rice industry in Vietnam.

The development of large processing-business enterprises with a closed, continuous processing system and direct links with farmers has been an important trend in the rice industry in the past 5 years. Objectively, Decree 109 on business and export conditions for rice has a decisive influence on the formation of this trend. However, it is worth noting that many large enterprises in this trend are those outside the industry, having traditional business fields outside the rice industry (Loc Troi, Cam Nguyen...). Due to the initial investment capital, large regular operating costs and high cash liquidity in the harvest season, businesses outside the industry have other business lines to compensate for rice purchasing, processing, and trading activities which have a great advantage to lead this trend.

Although cooperatives and cooperative economic organizations are not represented in the current popular value chain, with the emergence of farmer-enterprise cooperation, cooperative economic organizations are expected to play a more active role in the future. However, in order to develop in this direction, cooperatives need to improve their capacity to organize farmers and collect rice more to create trust for investment enterprises. At the same time, cooperatives also need to improve their negotiation ability, representing farmers to discuss with businesses to reach an agreement that is beneficial for both sides, creating motivation for farmers to participate in the association.

To meet the increasing quality requirements of the world market, as well as to cope with increasing competition from emerging rice export countries such as Cambodia and Myanmar, the strengthening of linkages between actors in the rice export value chain is the inevitable direction.

REFERENCES

Calvin Miller and Linda Jones (2010). Agricultural Value Chain Finance. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Dong Thap Provincial Statistics Office (2021). Dong Thap Province Statistical Yearbook 2020.

Dao The Anh (2017). Developing the value chain of Agri-food products.

Eaton, C and Shepherd, A. (2001). Contract Farming: Partnerships for Growth. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

GTZ (2007). Value Links Manual: Value Links Manual: The Methodology of Value Chain Promotion.

Michael Porter (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.

Nguyen Quoc Nghi. (2019). Solution to complete rice value chain in Phong Dien district, Can Tho city. Science Journal of Can Tho University, vol. 55, No. 1D (2019), pp. 101-108.

Nguyen Van Sanh (2018). Model of agricultural production linkage in the Mekong Delta in the context of market competition and climate change response. Regional workshop of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development held in Can Tho.

Vietnam Sub-Institute of Electromechanical and Postharvest Technology. (2011). Investigation results on post-harvest losses.

Rappael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris (2000). A Handbook for Value Chain Research.

Rerkasem, B. (2017). The Rice Value Chain: A Case Study of Thai Rice. ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (2017) Vol 4 No.1.

Department of Industry and Trade of Dong Thap province. (2020). Production and consumption of agricultural products of Dong Thap in the period 2014-2020.

Department of Agriculture and Rural Development of Dong Thap province. (2020). Report on implementation of agricultural restructuring in Dong Thap province, period 2016-2020. Dong Thap.

General Statistics Office. (2019). Results of the 2019 population and housing census, Hanoi.

General Statistics Office. (2020, 11-24). Statistics on agriculture, forestry and fishery. https://www.gso.gov.vn/nong-lam-nghiep-va-thuy-san/

Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development (2017). Report on the value chain of the rice industry in Dong Thap.

Institute of Policy and Strategy for Rural Development (2018). Status of sustainable rice farming in Dong Thap province.

Central Institute for Economic Management. (2017). Institutional review report on rice value chain. Hanoi.

Vo Thi Thanh Loc and Nguyen Phu Son. (2011). Rice value chain analysis in the Mekong Delta. Journal of Science 2011: 19a.

Vo Van Thanh, Le Ngoc Quynh Lam and Nguyen Thi Kim Pho. (2015). Situation of rice supply chain in the Mekong Delta. Science and technology development journal, volume 18, Q2-2015 issue.