ABSTRACT

Shrimp farming has been one of the major suppliers in the global agri-food system. The rapid growth of marine shrimp farming had led to the innovation and intensive farming system causing negative social and environmental impacts. Thailand has been for many years the leading world exporter of shrimps, of which over 90% are cultured. To ensure that Thai shrimp farmers follow good management practices, the government has encouraged them to certify against national standards for shrimp aquaculture. Moreover, a policy for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG12, has called for an effective strategy that is geared towards a more sustainable production and ecosystem, which consequently leads to the establishment of additional Thai Agricultural Standards. Apart from product safety and quality certification, many retailers have also started demanding for a third-party certification of eco-friendly products, which can potentially affect trade restriction for Thai shrimp farming. Benchmarking of the national shrimp certification schemes using the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI) benchmark tool as based on the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) certification guidelines, therefore, is one of the strategies to promote the recognition of sustainable Thai shrimp production and to facilitate market access. This article aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the current situation of marine shrimp production in Thailand and to offer details on the necessary steps regarding the national standardization to improve the environmental sustainability of the marine shrimp industry.

Keywords: Marine shrimp farming, sustainability, standardization, Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative

INTRODUCTION

Aquaculture has been considered as one of the major players in the global agri-food system. Foods produced from this industry provide a vital source of protein and essential micronutrients and contribute to the economy in many areas across the world. Over the past decades, the farming of fish and aquatic animals has expanded widely and globally as evidenced by the establishment of a larger scale commercial aquaculture in many developing countries

(Bostock et al., 2010; Food & Nations, 2016). The rapid growth and expansion of aquaculture had also led to the development of an innovative and intensive farming system resulting in the excessive production of undesirable high concentration of organic matter, including uneaten feed, feces and other excretory wastes that are released to the environment. Furthermore, the overfishing of some aquatic animal species has been a major multi-stakeholder concern

(Edwards, 2015; Kobayashi et al., 2015; Laurance et al., 2014; Troell et al., 2014). In view of this, various frameworks and actions have been taken in response to the global challenges of sustainable development. These include the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations and various procurement decisions made by different governments and organizations. Dialogues have also been extended to address various challenges of sustainable development in the aquaculture industry, such as the reduction of pollution from feed and waste and the escape of aquaculture animals into the wild populations

(Bhari & Visvanathan, 2018; Stead, 2019).

The interaction between the fisheries sector and the SDGs is focused on the biosphere preservation. This consists of five SDGs, namely, (i) SDG 6 - ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all, (ii) SDG12 -ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, (iii) SDG13 - taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impact, (iv) SDG14 - conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, and (v) SDG15 - protecting, restoring and promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably managing forests, combatting desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, and halting biodiversity loss (Sampantamit et al., 2020).

In Thailand, the SDGs have been integrated in the national policies and development plans at all levels, including the 20-Year National Strategy and the 12th Economic and Social Development Plan. Moreover, Thailand, as a responsible maritime nation, has shown its efforts and commitment to combat the problem of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing through various means, such as reforming legislative framework, implementing international fishing standards as well as establishing collaborations with other countries, and capacity building between the European Union (EU) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In addition, Thailand has implemented a number of policies and measures under its national development plan to prevent illegal fishing and minimize the exploitation of marine resources, and also included the development of a framework for sustainable fisheries and aquaculture. To date, Thailand has made a significant progress in translating such policies into practices. Nevertheless, much work remains to be done to ensure that Thailand’s fishing industry is truly sustainable, legal and ethical.

The frozen and processed shrimps, mostly Pacific White Shrimp, are particularly valuable export products of Thailand for a period of not less than 30 years. The total production of these products amounted to almost 300,000 metric tons in 2020, of which 95.5% and 4.5% are Pacific White Shrimp and Black Tiger Shrimp, respectively. An average 76.53% of the Pacific White Shrimp production were exported to the USA, Japan, China, South Korea and other countries (DOF, 2020). In view of the recent global situation, shrimp farming in Thailand has experienced numerous predicaments not only massive losses in productivity from a serious viral disease outbreak but also from losses in a perfectly competitive market due to the progressively stricter regulations concerning animal health, food safety, traceability and suitability set by importing countries and retail buyers throughout the supply chain.

Thailand has implemented the Good Aquaculture Practices (GAqP) to improve the overall farming practices and increase the production of aquaculture, in the face of a declining production due to disease (Booncharoen & Anal, 2021; Samerwong et al., 2018). In addition, a well-managed and sustainable fishery has become an attractive business strategy for global companies. This is evidenced by the rising number of consumers who are expecting more from their seafood.

The purpose of this article is to offer insights and to highlight works and policies with regard to the standardization for sustainable shrimp aquaculture in Thailand.

SCENARIO OF MARINE SHRIMP PRODUCTION IN THAILAND

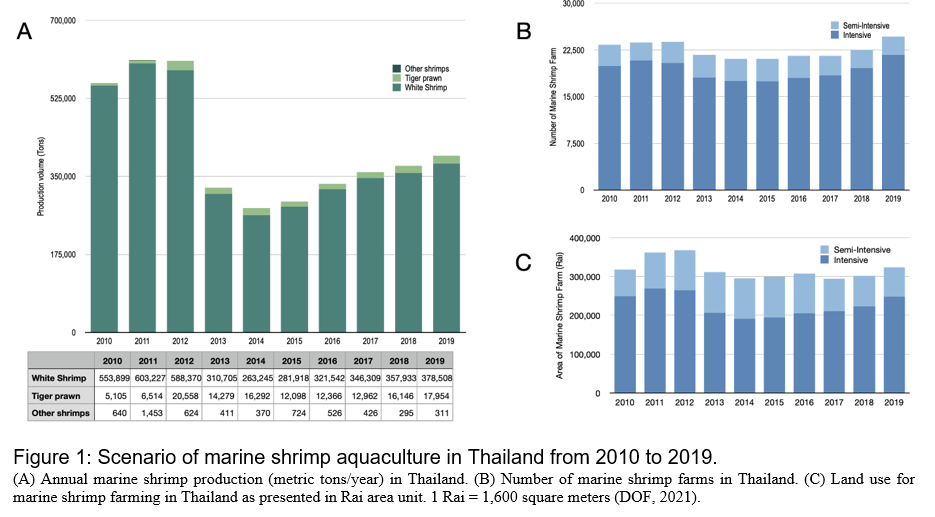

The ten-year data (from 2010 to 2019) from the Department of Fisheries (DOF), Thailand (Figure 1A) revealed that the average marine shrimp production before 2013 was around 593,000 metric tons/year (DOF, 2021). Since the outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS)/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in 2012, a significant loss in Thai shrimp production has been reported (Putth & Polchana, 2016). Thailand has been considered as one of the most affected countries in Asia by the outbreak, noting that Thailand was the second largest shrimp producer in the world after China and now has fallen to the sixth spot (Shinn et al., 2018). The total production decreased by 54% from 2012 (609,000 metric tons/year) to 2014 (279,000 metric tons/year) (Figure 1A). Corollary to this, a concomitant reduction by 11.6% and 20.0% in the number of marine shrimp farm and land use for shrimp aquaculture, respectively, was observed (Figure 1B and 1C).

Due to the recovery of Thailand’s shrimp farms after the EMS/AHPND outbreak, the year-on-year marine shrimp production in Thailand has gradually increased by 42%, when comparing productions between 2014 (279,000 metric tons/year) and 2019 (396,000 metric tons/year) (Figure 1A). The number of shrimp farm and its land use also increased by 17% and 10%, respectively (Figures 1B and 1C). It is very interesting to note that the area of land used for intensive shrimp farming had significantly increased by 30% over 5 years (from 2014 to 2019), whereas the area of land used for semi-intensive system had decreased by 10%. This rapid growth of intensive farming system may potentially cause a negative effect on the environment, especially when control measures are not being properly implemented.

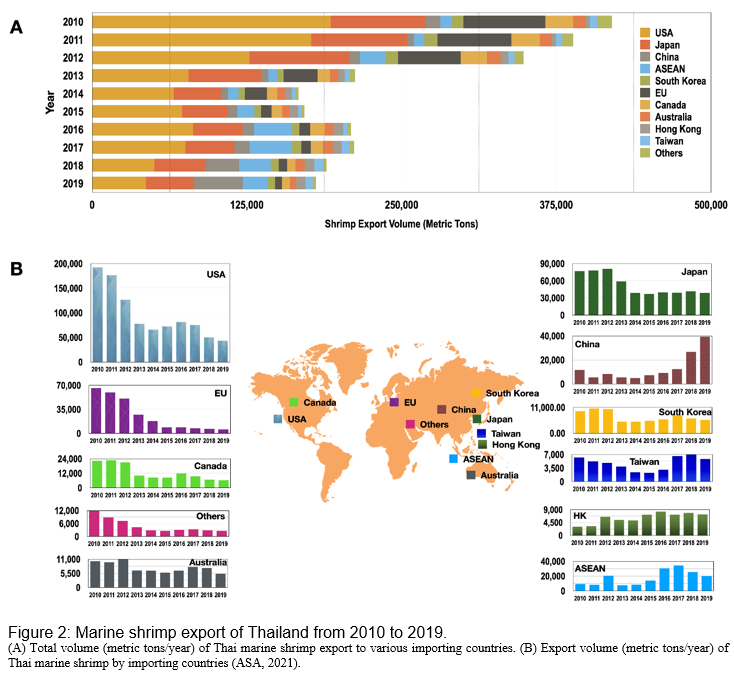

For the overseas markets, data from the DOF showed that the export of marine shrimp, mostly Pacific White Shrimp, were mainly driven by the US (ASA, 2021). After the EMS/APHND outbreak, the market of Thai marine shrimp in the US grew about 25% (from 2014 to 2016); however, the export to the US decreased by 35% in 2018, largely due to the lower price supply from India, Indonesia, Ecuador, and China entering the US market. With the EU, the export has dropped since 2015 due to the impact from losing privilege of the EU’s Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) (Yamabhai et al., 2017). On the other hand, the trade facilitation through ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) has turned Thailand to be one of the leading suppliers of marine shrimp to China since 2018 (Rattana-amornpirom, 2020). Additionally, the other major importers of Thai marine shrimp include Canada, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and ASEAN countries (Figure 2).

THAI CERTIFICATION STANDARDS FOR SHRIMP AQUACULTURE

To promote the safety, quality and profitability of shrimp farming in Thailand, two national standards for shrimp aquaculture, namely, the Code of Conduct (CoC) and GAqP were developed by the DOF of Thailand in 1998 and 2000, respectively. These national standards were developed based on the FAO CoC for Responsible Fisheries, Codex Code of Practice, and ISO14001 to address the various aspects of responsible fishery managements, such as the aquafarming systems and neighboring areas, disease control, the use of antimicrobials, environment protection, and traceability (DOF, 2002, 2010). At that time, the DOF served as the standards developer, inspection body and certification body (Samerwong et al., 2018).

Since 2002, the National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards (ACFS) has been established, acting as the national standard-setting agency for agricultural products and food. The ACFS also functions as an accreditation body that is the signatory to the Asia-Pacific Accreditation Cooperation /International Accreditation Forum Multilateral Recognition Arrangement (APAC/IAF MLA). Meanwhile, the DOF has changed its role to serving as an accredited certification body for fishery products. In 2009, ACFS has established the Thai Agricultural Standard on Good Aquaculture Practices for Marine Shrimp Farm (TAS-7401). This standard is applicable on a voluntary basis for all types of marine shrimp farms. In view of the changing trade situation and technical information, the TAS-7401 has been revised in 2014 and 2019 to include a wide range of updated criteria on environmental impacts, social issues, and animal welfares (ACFS, 2019).

In view of the EMS/APHND outbreak, the ACFS had also established the standard on Good Aquaculture Practices for Hatchery of Disease Free Pacific White Shrimp (TAS-7432) in 2015, covering from the receipt of the broodstock up until the shrimp nauplii are ready to be moved from the hatching pond or other hatching containers so as to obtain shrimps that are free from target diseases (ACFS, 2015).

As of October 2020, there are 9,111 GAqP-certified shrimp farms in Thailand or about 71.1% of the total number of registered farms. Despite the absence of variation in the actual price of shrimp, whether produced under GAqP or non-GAqP farms, it has been observed that the certified farmers in Thailand found the GAqP certification to be very useful in increasing productivity and product quality as well as in ensuring sustainable production system particularly in matters of environmental conservation (Booncharoen & Anal, 2021).

CHALLENGES AND POLICIES ON SUSTAINABILITY

In view of the global trend on sustainable fisheries, the SDG12 is the key component that promotes responsible consumptions and sustainable production, which can be achieved by the fisheries sectors through an efficient sustainable management of natural resources, recycling and sound management of chemicals and other wastes. The possible means of ensuring a responsible production system comprise, among others, the closer performance monitoring of business, regulatory constraints, and systems such as product certification, traceability systems, and ecolabelling (Sampantamit et al., 2020). As a result, the ecolabelling certification for seafood products has been developed to address the social and environmental impacts of the seafood industry. The ecolabelling standard requires various environmental considerations, such as the protection of natural habitats (mangrove forests and wetland), the avoidance of antimicrobial use, and the availability of waste water treatment system. Alongside the requirements on environment, the core principles of good labor practices are also included in this scheme. (Robinson et al., 2021; Roheim et al., 2018).

In the business sense, the concept of ecolabelling becomes a condition for market access and can also be a potential trade barrier upon implementation of the policy that ensures sustainable management in the fisheries production system. Despite the efforts made by Thai authorities to provide the necessary TAS certification to ensure a reliable, safe and environmentally friendly seafood products, the demand for a third-party certification for the ecolabelling of shrimp products from the major importing country has gradually increased. As a consequence, the market opportunity of Thai shrimp producers has opened to those who can afford the expense for the ecolabelling certification through several third-party private certification programs, such as Global Good Agricultural Practices (GLOBALG.A.P.), Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP), and Alaska Responsible Fisheries Management (RFM) Certification Program.

In 2013, the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI) Benchmark Tool project was launched in collaboration between the private and public sectors, international organization (i.e., FAO) and governments to improve the management of seafood production and create a uniform approach for seafood sustainability. The GSSI Benchmark Tool was created on the basis of three relevant FAO documents, including the FAO CoC for Responsible Fisheries, FAO Guidelines for the Ecolabelling of Fish and Fishery Products, and FAO Technical Guidelines on Aquaculture Certification (Sorg et al., 2019). Once a scheme successfully completes the benchmarking process, such scheme will be recognized as being aligned with the GSSI essential components or so called “GSSI-recognized”. The GSSI Benchmark is a set of 186 components used to assess if a scheme has sound governance and operational management (including Chain of Custody). These components also include the management of environmental sustainability using the best available scientific evidence, the protection of habitats and ecosystems, and the prevention of adverse effects on endangered species (GSSI, 2015).

Despite the certification of Thai shrimp products with the national GAqP standard, there has been an increasing demand for a third-party certification of eco-friendly products among major retailers importing Thai marine shrimps. As part of its continuous efforts to strengthen the Thai seafood industry, the ACFS has launched the next phase of its certification for Thai marine shrimps in order to increase the credibility and market penetration of Thai GAqP standard by benchmarking relevant national standards against the GSSI essential components. It is also interesting to note that the TAS-7401 has been acknowledged as one of eight seafood certification schemes that participated in the pilot testing of the GSSI Tool. However, much work remains to be completed before the GSSI-recognized certification scheme can be officially announced.

Following the above, it has been expected that within a couple of years, the next revision of the TAS-7401 standard would accommodate the various requirements of the relevant FAO guidelines and regulations. Moreover, another new standard on “Chain of Custody” will be established to provide an assurance to a certified product originating from a TAS-7401-certified farm. This policy will allow the GSSI-recognized certification to be a common pool resource for all Thai shrimp farmers, without paying a heavy expense for certification process through the certifying agent, and will also assist Thai marine shrimp producers to be more competitive in the global market while maintaining their rank as one of the top shrimp exporters in the world.

CONCLUSION

This article discussed the production and marketing of Thai marine shrimp over the past decade and explored how the emergence of disease outbreak affected the marine shrimp production in Thailand. The effort to revitalize and improve the profitability and competitiveness of commercial aquaculture farming has been observed in view of the significant increase in land use for intensive farming system and the gradual growth of year-to-year marine shrimp production. Although the loss in Thai marine shrimp exports has been intense over the years due to the entry of new key players in the global shrimp market and trade policy, opportunities are still available for premium products with great value in niche markets. Moreover, this article also provided details on the various national certifications, both voluntary and mandatory standards, for shrimp farming in Thailand. Considering that sustainable eco-friendly production systems are seen to be a global trend, response to the challenges on sustainability in fishery production through national policies and development plans is evident. However, the lack of international recognition of Thai marine shrimp certification is a problem that needs to be solved. With the mutual efforts of various stakeholders, including policymakers and the fisheries industry, the Thai national certification scheme for marine shrimp products will become ready for benchmarking and further become designated as a GSSI-recognized scheme in the near future. Ultimately, this will allow the Thai marine shrimp products to gain greater acceptance globally and become a leader in sustainable aquaculture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Ms. Oratai Silapanapaporn (Advisor, National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards) for technical support and Dr. Jedhan Ucat Galula (Graduate Institute of Microbiology and Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, National Chung-Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan ROC) for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

ACFS. (2015). Thai Agricultural Standard: Good Aquaculute Practices Hatchery of Disease Free Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) https://www.acfs.go.th/files/files/commodity-standard/20190610140525_397471.pdf

ACFS. (2019). Thai Agricultural Standard: Good Aquaculute Practices for Marine Shrimp Farm. https://www.acfs.go.th/files/files/commodity-standard/20201102101019_495088.pdf

ASA. (2021). Top 10 shrimp Export markets of Thailand during 2010 - 2019, ASEAN Shrimp Alliance. https://www.fisheries.go.th/aseanshrimpalliance/activities/exim5263.pdf

Bhari, B., & Visvanathan, C. (2018). Sustainable Aquaculture: Socio-Economic and Environmental Assessment. In F. I. Hai, C. Visvanathan, & R. Boopathy (Eds.), Sustainable Aquaculture (pp. 63-93). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73257-2_2

Booncharoen, C., & Anal, A. K. (2021). Attitudes, Perceptions, and On-Farm Self-Reported Practices of Shrimp Farmers’ towards Adoption of Good Aquaculture Practices (GAP) in Thailand. Sustainability, 13(9), 5194. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/9/5194

Bostock, J., McAndrew, B., Richards, R., Jauncey, K., Telfer, T., Lorenzen, K., Little, D., Ross, L., Handisyde, N., Gatward, I., & Corner, R. (2010). Aquaculture: global status and trends. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 365(1554), 2897-2912. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0170

DOF. (2002). Code of Conduct (CoC), Fisheries Commodity Standard System and Traceability Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/cf-chan/CoC/DOFCoC.pdf

DOF. (2010). Good Aquaculture Practice (GAP) Fisheries Commodity Standard System and Traceability Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/cf-chan/CoC/DOFGAP.doc

DOF. (2020). Thai marine shrimp product report 2020, Fisheries Development Policy and Planning Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/strategy/fisheconomic/Monthly%20report/Shrimp/%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B8%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B0%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A5%2012%20%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99%2063%20%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B8%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%A0%E0%B8%B2(end).pdf

DOF. (2021). Report on the situation of Thai marine shrimp, Fisheries Economic Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/strategy/fisheconomic/pages/fish%20shrimp.html

Edwards, P. (2015). Aquaculture environment interactions: Past, present and likely future trends. Aquaculture, 447, 2-14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.02.001

Food, & Nations, A. O. o. t. U. (2016). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. United Nations. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18356/8e4e0ebf-en

GSSI. (2015). Global sustainable seafood initiative global benchmark tool.

Kobayashi, M., Msangi, S., Batka, M., Vannuccini, S., Dey, M. M., & Anderson, J. L. (2015). Fish to 2030: The Role and Opportunity for Aquaculture. Aquaculture Economics & Management, 19(3), 282-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2015.994240

Laurance, W. F., Sayer, J., & Cassman, K. G. (2014). Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29(2), 107-116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.12.001

Putth, S., & Polchana, J. (2016). Current status and impact of early mortality syndrome (EMS)/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and hepatopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM) outbreaks on Thailand s shrimp farming. Addressing Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND) and Other Transboundary Diseases for Improved Aquatic Animal Health in Southeast Asia: Proceedings of the ASEAN Regional Technical Consultation on EMS/AHPND and Other Transboundary Diseases for Improved Aquatic Animal Health in Southeast Asia, 22-24 February 2016, Makati City, Philippines,

Rattana-amornpirom, O. (2020). The Impacts of ACFTA on Export of Thai Agricultural Products to China. Journal of ASEAN PLUS Studies, 1(1), 44-54.

Robinson, L. M., van Putten, I., Cavve, B. S., Longo, C., Watson, M., Bellchambers, L., Fisher, E., & Boschetti, F. (2021). Understanding societal approval of the fishing industry and the influence of third‐party sustainability certification. Fish and Fisheries.

Roheim, C., Bush, S., Asche, F., Sanchirico, J., & Uchida, H. (2018). Evolution and future of the sustainable seafood market. Nature Sustainability, 1(8), 392-398.

Samerwong, P., Bush, S. R., & Oosterveer, P. (2018). Implications of multiple national certification standards for Thai shrimp aquaculture. Aquaculture, 493, 319-327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.01.019

Sampantamit, T., Ho, L., Van Echelpoel, W., Lachat, C., & Goethals, P. (2020). Links and trade-offs between fisheries and environmental protection in relation to the sustainable development goals in Thailand. Water, 12(2), 399.

Shinn, A., Pratoomyot, J., Griffiths, D., Trong, T., Vu, N. T., Jiravanichpaisal, P., & Briggs, M. (2018). Asian shrimp production and the economic costs of disease. Asian Fish Sci S, 31, 29-58.

Sorg, F., Kahle, J., Wehner, N., Mangold, M., & Peters, S. (2019). Clarity in Diversity: How the Sustainability Standards Comparison Tool and the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative Provide Orientation. In Sustainable Global Value Chains (pp. 239-264). Springer.

Stead, S. M. (2019). Using systems thinking and open innovation to strengthen aquaculture policy for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. J Fish Biol, 94(6), 837-844. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13970

Troell, M., Naylor, R. L., Metian, M., Beveridge, M., Tyedmers, P. H., Folke, C., Arrow, K. J., Barrett, S., Crépin, A. S., Ehrlich, P. R., Gren, A., Kautsky, N., Levin, S. A., Nyborg, K., Österblom, H., Polasky, S., Scheffer, M., Walker, B. H., Xepapadeas, T., & de Zeeuw, A. (2014). Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(37), 13257-13263. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1404067111

Yamabhai, I., Santatiwongchai, B., & Akaleephan, C. (2017). Assessing the impact of the Thailand-European Union free trade agreement on trade and investment in Thailand. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access S, 1, 2.

Policies on Advancing Eco-friendly Aquaculture Shrimp Farming in Thailand

ABSTRACT

Shrimp farming has been one of the major suppliers in the global agri-food system. The rapid growth of marine shrimp farming had led to the innovation and intensive farming system causing negative social and environmental impacts. Thailand has been for many years the leading world exporter of shrimps, of which over 90% are cultured. To ensure that Thai shrimp farmers follow good management practices, the government has encouraged them to certify against national standards for shrimp aquaculture. Moreover, a policy for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG12, has called for an effective strategy that is geared towards a more sustainable production and ecosystem, which consequently leads to the establishment of additional Thai Agricultural Standards. Apart from product safety and quality certification, many retailers have also started demanding for a third-party certification of eco-friendly products, which can potentially affect trade restriction for Thai shrimp farming. Benchmarking of the national shrimp certification schemes using the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI) benchmark tool as based on the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) certification guidelines, therefore, is one of the strategies to promote the recognition of sustainable Thai shrimp production and to facilitate market access. This article aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the current situation of marine shrimp production in Thailand and to offer details on the necessary steps regarding the national standardization to improve the environmental sustainability of the marine shrimp industry.

Keywords: Marine shrimp farming, sustainability, standardization, Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative

INTRODUCTION

Aquaculture has been considered as one of the major players in the global agri-food system. Foods produced from this industry provide a vital source of protein and essential micronutrients and contribute to the economy in many areas across the world. Over the past decades, the farming of fish and aquatic animals has expanded widely and globally as evidenced by the establishment of a larger scale commercial aquaculture in many developing countries

(Bostock et al., 2010; Food & Nations, 2016). The rapid growth and expansion of aquaculture had also led to the development of an innovative and intensive farming system resulting in the excessive production of undesirable high concentration of organic matter, including uneaten feed, feces and other excretory wastes that are released to the environment. Furthermore, the overfishing of some aquatic animal species has been a major multi-stakeholder concern

(Edwards, 2015; Kobayashi et al., 2015; Laurance et al., 2014; Troell et al., 2014). In view of this, various frameworks and actions have been taken in response to the global challenges of sustainable development. These include the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations and various procurement decisions made by different governments and organizations. Dialogues have also been extended to address various challenges of sustainable development in the aquaculture industry, such as the reduction of pollution from feed and waste and the escape of aquaculture animals into the wild populations

(Bhari & Visvanathan, 2018; Stead, 2019).

The interaction between the fisheries sector and the SDGs is focused on the biosphere preservation. This consists of five SDGs, namely, (i) SDG 6 - ensuring the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all, (ii) SDG12 -ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, (iii) SDG13 - taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impact, (iv) SDG14 - conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, and (v) SDG15 - protecting, restoring and promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably managing forests, combatting desertification, halting and reversing land degradation, and halting biodiversity loss (Sampantamit et al., 2020).

In Thailand, the SDGs have been integrated in the national policies and development plans at all levels, including the 20-Year National Strategy and the 12th Economic and Social Development Plan. Moreover, Thailand, as a responsible maritime nation, has shown its efforts and commitment to combat the problem of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing through various means, such as reforming legislative framework, implementing international fishing standards as well as establishing collaborations with other countries, and capacity building between the European Union (EU) and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In addition, Thailand has implemented a number of policies and measures under its national development plan to prevent illegal fishing and minimize the exploitation of marine resources, and also included the development of a framework for sustainable fisheries and aquaculture. To date, Thailand has made a significant progress in translating such policies into practices. Nevertheless, much work remains to be done to ensure that Thailand’s fishing industry is truly sustainable, legal and ethical.

The frozen and processed shrimps, mostly Pacific White Shrimp, are particularly valuable export products of Thailand for a period of not less than 30 years. The total production of these products amounted to almost 300,000 metric tons in 2020, of which 95.5% and 4.5% are Pacific White Shrimp and Black Tiger Shrimp, respectively. An average 76.53% of the Pacific White Shrimp production were exported to the USA, Japan, China, South Korea and other countries (DOF, 2020). In view of the recent global situation, shrimp farming in Thailand has experienced numerous predicaments not only massive losses in productivity from a serious viral disease outbreak but also from losses in a perfectly competitive market due to the progressively stricter regulations concerning animal health, food safety, traceability and suitability set by importing countries and retail buyers throughout the supply chain.

Thailand has implemented the Good Aquaculture Practices (GAqP) to improve the overall farming practices and increase the production of aquaculture, in the face of a declining production due to disease (Booncharoen & Anal, 2021; Samerwong et al., 2018). In addition, a well-managed and sustainable fishery has become an attractive business strategy for global companies. This is evidenced by the rising number of consumers who are expecting more from their seafood.

The purpose of this article is to offer insights and to highlight works and policies with regard to the standardization for sustainable shrimp aquaculture in Thailand.

SCENARIO OF MARINE SHRIMP PRODUCTION IN THAILAND

The ten-year data (from 2010 to 2019) from the Department of Fisheries (DOF), Thailand (Figure 1A) revealed that the average marine shrimp production before 2013 was around 593,000 metric tons/year (DOF, 2021). Since the outbreak of early mortality syndrome (EMS)/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in 2012, a significant loss in Thai shrimp production has been reported (Putth & Polchana, 2016). Thailand has been considered as one of the most affected countries in Asia by the outbreak, noting that Thailand was the second largest shrimp producer in the world after China and now has fallen to the sixth spot (Shinn et al., 2018). The total production decreased by 54% from 2012 (609,000 metric tons/year) to 2014 (279,000 metric tons/year) (Figure 1A). Corollary to this, a concomitant reduction by 11.6% and 20.0% in the number of marine shrimp farm and land use for shrimp aquaculture, respectively, was observed (Figure 1B and 1C).

Due to the recovery of Thailand’s shrimp farms after the EMS/AHPND outbreak, the year-on-year marine shrimp production in Thailand has gradually increased by 42%, when comparing productions between 2014 (279,000 metric tons/year) and 2019 (396,000 metric tons/year) (Figure 1A). The number of shrimp farm and its land use also increased by 17% and 10%, respectively (Figures 1B and 1C). It is very interesting to note that the area of land used for intensive shrimp farming had significantly increased by 30% over 5 years (from 2014 to 2019), whereas the area of land used for semi-intensive system had decreased by 10%. This rapid growth of intensive farming system may potentially cause a negative effect on the environment, especially when control measures are not being properly implemented.

For the overseas markets, data from the DOF showed that the export of marine shrimp, mostly Pacific White Shrimp, were mainly driven by the US (ASA, 2021). After the EMS/APHND outbreak, the market of Thai marine shrimp in the US grew about 25% (from 2014 to 2016); however, the export to the US decreased by 35% in 2018, largely due to the lower price supply from India, Indonesia, Ecuador, and China entering the US market. With the EU, the export has dropped since 2015 due to the impact from losing privilege of the EU’s Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) (Yamabhai et al., 2017). On the other hand, the trade facilitation through ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) has turned Thailand to be one of the leading suppliers of marine shrimp to China since 2018 (Rattana-amornpirom, 2020). Additionally, the other major importers of Thai marine shrimp include Canada, Australia, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and ASEAN countries (Figure 2).

THAI CERTIFICATION STANDARDS FOR SHRIMP AQUACULTURE

To promote the safety, quality and profitability of shrimp farming in Thailand, two national standards for shrimp aquaculture, namely, the Code of Conduct (CoC) and GAqP were developed by the DOF of Thailand in 1998 and 2000, respectively. These national standards were developed based on the FAO CoC for Responsible Fisheries, Codex Code of Practice, and ISO14001 to address the various aspects of responsible fishery managements, such as the aquafarming systems and neighboring areas, disease control, the use of antimicrobials, environment protection, and traceability (DOF, 2002, 2010). At that time, the DOF served as the standards developer, inspection body and certification body (Samerwong et al., 2018).

Since 2002, the National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards (ACFS) has been established, acting as the national standard-setting agency for agricultural products and food. The ACFS also functions as an accreditation body that is the signatory to the Asia-Pacific Accreditation Cooperation /International Accreditation Forum Multilateral Recognition Arrangement (APAC/IAF MLA). Meanwhile, the DOF has changed its role to serving as an accredited certification body for fishery products. In 2009, ACFS has established the Thai Agricultural Standard on Good Aquaculture Practices for Marine Shrimp Farm (TAS-7401). This standard is applicable on a voluntary basis for all types of marine shrimp farms. In view of the changing trade situation and technical information, the TAS-7401 has been revised in 2014 and 2019 to include a wide range of updated criteria on environmental impacts, social issues, and animal welfares (ACFS, 2019).

In view of the EMS/APHND outbreak, the ACFS had also established the standard on Good Aquaculture Practices for Hatchery of Disease Free Pacific White Shrimp (TAS-7432) in 2015, covering from the receipt of the broodstock up until the shrimp nauplii are ready to be moved from the hatching pond or other hatching containers so as to obtain shrimps that are free from target diseases (ACFS, 2015).

As of October 2020, there are 9,111 GAqP-certified shrimp farms in Thailand or about 71.1% of the total number of registered farms. Despite the absence of variation in the actual price of shrimp, whether produced under GAqP or non-GAqP farms, it has been observed that the certified farmers in Thailand found the GAqP certification to be very useful in increasing productivity and product quality as well as in ensuring sustainable production system particularly in matters of environmental conservation (Booncharoen & Anal, 2021).

CHALLENGES AND POLICIES ON SUSTAINABILITY

In view of the global trend on sustainable fisheries, the SDG12 is the key component that promotes responsible consumptions and sustainable production, which can be achieved by the fisheries sectors through an efficient sustainable management of natural resources, recycling and sound management of chemicals and other wastes. The possible means of ensuring a responsible production system comprise, among others, the closer performance monitoring of business, regulatory constraints, and systems such as product certification, traceability systems, and ecolabelling (Sampantamit et al., 2020). As a result, the ecolabelling certification for seafood products has been developed to address the social and environmental impacts of the seafood industry. The ecolabelling standard requires various environmental considerations, such as the protection of natural habitats (mangrove forests and wetland), the avoidance of antimicrobial use, and the availability of waste water treatment system. Alongside the requirements on environment, the core principles of good labor practices are also included in this scheme. (Robinson et al., 2021; Roheim et al., 2018).

In the business sense, the concept of ecolabelling becomes a condition for market access and can also be a potential trade barrier upon implementation of the policy that ensures sustainable management in the fisheries production system. Despite the efforts made by Thai authorities to provide the necessary TAS certification to ensure a reliable, safe and environmentally friendly seafood products, the demand for a third-party certification for the ecolabelling of shrimp products from the major importing country has gradually increased. As a consequence, the market opportunity of Thai shrimp producers has opened to those who can afford the expense for the ecolabelling certification through several third-party private certification programs, such as Global Good Agricultural Practices (GLOBALG.A.P.), Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP), and Alaska Responsible Fisheries Management (RFM) Certification Program.

In 2013, the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative (GSSI) Benchmark Tool project was launched in collaboration between the private and public sectors, international organization (i.e., FAO) and governments to improve the management of seafood production and create a uniform approach for seafood sustainability. The GSSI Benchmark Tool was created on the basis of three relevant FAO documents, including the FAO CoC for Responsible Fisheries, FAO Guidelines for the Ecolabelling of Fish and Fishery Products, and FAO Technical Guidelines on Aquaculture Certification (Sorg et al., 2019). Once a scheme successfully completes the benchmarking process, such scheme will be recognized as being aligned with the GSSI essential components or so called “GSSI-recognized”. The GSSI Benchmark is a set of 186 components used to assess if a scheme has sound governance and operational management (including Chain of Custody). These components also include the management of environmental sustainability using the best available scientific evidence, the protection of habitats and ecosystems, and the prevention of adverse effects on endangered species (GSSI, 2015).

Despite the certification of Thai shrimp products with the national GAqP standard, there has been an increasing demand for a third-party certification of eco-friendly products among major retailers importing Thai marine shrimps. As part of its continuous efforts to strengthen the Thai seafood industry, the ACFS has launched the next phase of its certification for Thai marine shrimps in order to increase the credibility and market penetration of Thai GAqP standard by benchmarking relevant national standards against the GSSI essential components. It is also interesting to note that the TAS-7401 has been acknowledged as one of eight seafood certification schemes that participated in the pilot testing of the GSSI Tool. However, much work remains to be completed before the GSSI-recognized certification scheme can be officially announced.

Following the above, it has been expected that within a couple of years, the next revision of the TAS-7401 standard would accommodate the various requirements of the relevant FAO guidelines and regulations. Moreover, another new standard on “Chain of Custody” will be established to provide an assurance to a certified product originating from a TAS-7401-certified farm. This policy will allow the GSSI-recognized certification to be a common pool resource for all Thai shrimp farmers, without paying a heavy expense for certification process through the certifying agent, and will also assist Thai marine shrimp producers to be more competitive in the global market while maintaining their rank as one of the top shrimp exporters in the world.

CONCLUSION

This article discussed the production and marketing of Thai marine shrimp over the past decade and explored how the emergence of disease outbreak affected the marine shrimp production in Thailand. The effort to revitalize and improve the profitability and competitiveness of commercial aquaculture farming has been observed in view of the significant increase in land use for intensive farming system and the gradual growth of year-to-year marine shrimp production. Although the loss in Thai marine shrimp exports has been intense over the years due to the entry of new key players in the global shrimp market and trade policy, opportunities are still available for premium products with great value in niche markets. Moreover, this article also provided details on the various national certifications, both voluntary and mandatory standards, for shrimp farming in Thailand. Considering that sustainable eco-friendly production systems are seen to be a global trend, response to the challenges on sustainability in fishery production through national policies and development plans is evident. However, the lack of international recognition of Thai marine shrimp certification is a problem that needs to be solved. With the mutual efforts of various stakeholders, including policymakers and the fisheries industry, the Thai national certification scheme for marine shrimp products will become ready for benchmarking and further become designated as a GSSI-recognized scheme in the near future. Ultimately, this will allow the Thai marine shrimp products to gain greater acceptance globally and become a leader in sustainable aquaculture.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Ms. Oratai Silapanapaporn (Advisor, National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards) for technical support and Dr. Jedhan Ucat Galula (Graduate Institute of Microbiology and Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, National Chung-Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan ROC) for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

ACFS. (2015). Thai Agricultural Standard: Good Aquaculute Practices Hatchery of Disease Free Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) https://www.acfs.go.th/files/files/commodity-standard/20190610140525_397471.pdf

ACFS. (2019). Thai Agricultural Standard: Good Aquaculute Practices for Marine Shrimp Farm. https://www.acfs.go.th/files/files/commodity-standard/20201102101019_495088.pdf

ASA. (2021). Top 10 shrimp Export markets of Thailand during 2010 - 2019, ASEAN Shrimp Alliance. https://www.fisheries.go.th/aseanshrimpalliance/activities/exim5263.pdf

Bhari, B., & Visvanathan, C. (2018). Sustainable Aquaculture: Socio-Economic and Environmental Assessment. In F. I. Hai, C. Visvanathan, & R. Boopathy (Eds.), Sustainable Aquaculture (pp. 63-93). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73257-2_2

Booncharoen, C., & Anal, A. K. (2021). Attitudes, Perceptions, and On-Farm Self-Reported Practices of Shrimp Farmers’ towards Adoption of Good Aquaculture Practices (GAP) in Thailand. Sustainability, 13(9), 5194. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/9/5194

Bostock, J., McAndrew, B., Richards, R., Jauncey, K., Telfer, T., Lorenzen, K., Little, D., Ross, L., Handisyde, N., Gatward, I., & Corner, R. (2010). Aquaculture: global status and trends. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 365(1554), 2897-2912. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0170

DOF. (2002). Code of Conduct (CoC), Fisheries Commodity Standard System and Traceability Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/cf-chan/CoC/DOFCoC.pdf

DOF. (2010). Good Aquaculture Practice (GAP) Fisheries Commodity Standard System and Traceability Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/cf-chan/CoC/DOFGAP.doc

DOF. (2020). Thai marine shrimp product report 2020, Fisheries Development Policy and Planning Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/strategy/fisheconomic/Monthly%20report/Shrimp/%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B8%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B0%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%A5%2012%20%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B7%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99%2063%20%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B8%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%A0%E0%B8%B2(end).pdf

DOF. (2021). Report on the situation of Thai marine shrimp, Fisheries Economic Division. https://www.fisheries.go.th/strategy/fisheconomic/pages/fish%20shrimp.html

Edwards, P. (2015). Aquaculture environment interactions: Past, present and likely future trends. Aquaculture, 447, 2-14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.02.001

Food, & Nations, A. O. o. t. U. (2016). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016. United Nations. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18356/8e4e0ebf-en

GSSI. (2015). Global sustainable seafood initiative global benchmark tool.

Kobayashi, M., Msangi, S., Batka, M., Vannuccini, S., Dey, M. M., & Anderson, J. L. (2015). Fish to 2030: The Role and Opportunity for Aquaculture. Aquaculture Economics & Management, 19(3), 282-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13657305.2015.994240

Laurance, W. F., Sayer, J., & Cassman, K. G. (2014). Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29(2), 107-116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.12.001

Putth, S., & Polchana, J. (2016). Current status and impact of early mortality syndrome (EMS)/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) and hepatopancreatic microsporidiosis (HPM) outbreaks on Thailand s shrimp farming. Addressing Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease (AHPND) and Other Transboundary Diseases for Improved Aquatic Animal Health in Southeast Asia: Proceedings of the ASEAN Regional Technical Consultation on EMS/AHPND and Other Transboundary Diseases for Improved Aquatic Animal Health in Southeast Asia, 22-24 February 2016, Makati City, Philippines,

Rattana-amornpirom, O. (2020). The Impacts of ACFTA on Export of Thai Agricultural Products to China. Journal of ASEAN PLUS Studies, 1(1), 44-54.

Robinson, L. M., van Putten, I., Cavve, B. S., Longo, C., Watson, M., Bellchambers, L., Fisher, E., & Boschetti, F. (2021). Understanding societal approval of the fishing industry and the influence of third‐party sustainability certification. Fish and Fisheries.

Roheim, C., Bush, S., Asche, F., Sanchirico, J., & Uchida, H. (2018). Evolution and future of the sustainable seafood market. Nature Sustainability, 1(8), 392-398.

Samerwong, P., Bush, S. R., & Oosterveer, P. (2018). Implications of multiple national certification standards for Thai shrimp aquaculture. Aquaculture, 493, 319-327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.01.019

Sampantamit, T., Ho, L., Van Echelpoel, W., Lachat, C., & Goethals, P. (2020). Links and trade-offs between fisheries and environmental protection in relation to the sustainable development goals in Thailand. Water, 12(2), 399.

Shinn, A., Pratoomyot, J., Griffiths, D., Trong, T., Vu, N. T., Jiravanichpaisal, P., & Briggs, M. (2018). Asian shrimp production and the economic costs of disease. Asian Fish Sci S, 31, 29-58.

Sorg, F., Kahle, J., Wehner, N., Mangold, M., & Peters, S. (2019). Clarity in Diversity: How the Sustainability Standards Comparison Tool and the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative Provide Orientation. In Sustainable Global Value Chains (pp. 239-264). Springer.

Stead, S. M. (2019). Using systems thinking and open innovation to strengthen aquaculture policy for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. J Fish Biol, 94(6), 837-844. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13970

Troell, M., Naylor, R. L., Metian, M., Beveridge, M., Tyedmers, P. H., Folke, C., Arrow, K. J., Barrett, S., Crépin, A. S., Ehrlich, P. R., Gren, A., Kautsky, N., Levin, S. A., Nyborg, K., Österblom, H., Polasky, S., Scheffer, M., Walker, B. H., Xepapadeas, T., & de Zeeuw, A. (2014). Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(37), 13257-13263. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1404067111

Yamabhai, I., Santatiwongchai, B., & Akaleephan, C. (2017). Assessing the impact of the Thailand-European Union free trade agreement on trade and investment in Thailand. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access S, 1, 2.