ABSTRACT

Household food consumption patterns in Korea are changing rapidly. These changes are caused by the changes in population and household structure, development of science and technology, climate change, and accelerated opening of the agri-food market (Lee et al., 2016). Since household food consumption behavior affects various areas such as personal nutrition and health status, food manufacturing and service industry, and government policy, it is necessary to continuously track and study the behavioral changes. This paper provides market and policy implications to agriculture and food industry as well as to the government by summarizing the changes in food consumption in Korea mainly based on a national survey conducted by the Korea Rural Economic Institute, which is named by “The Consumer Behavior Survey for Food (CBSF, hereafter),” as well as other national statistics related to food consumption.

Keywords: Consumer Behavior, Food Consumption, Household, Trends

INTRODUCTION

Food consumption and eating habits in Korea are changing rapidly. Since 2000, eating out has been expanding dramatically, and since 2015, consumption of HMR (home meal replacement) has continued to grow. As the lives of modern people are fundamentally complex, and the economic participation of women increases, the opportunity cost of preparing for meals at home has increased. In addition, evident consumer preference for ‘simplification’ or ‘simple life’ also contributes to the growth of restaurants and the HMR industry. As the number of single-person households increases, and as what we called the ‘eating along culture’ or ‘drinking alone culture’ is widely spreading, the preference for small-sized items for agri-food products is rapidly expanding. Food distribution channels are also changing. Online purchases of agri-food products are on the rise, and the same-day shipping and early morning delivery are becoming popular among Korean consumers. Food purchases at convenience stores are soaring, and consumption of imported foods is also increasing. In terms of dietary habits, nutritional imbalance is expanded due to an increase in animal food or fat intake, excessive diet (excessive rate of being on a diet), and an increase in rate of skipping breakfast meals. Furthermore, the prevalence of dietary-related diseases such as obesity and metabolic syndrome is also increasing.

As described above, agri-food consumption is changing very rapidly. It is thus essential to understand changes and trends in food consumption in order to present the right direction of food policy and agriculture. Based on the enhanced understanding on consumers and food consumption, policies could be newly introduced or improved in response to the changes in food consumption, and new opportunities for development in agriculture and the food industry could be discovered.

Long-term food consumption stage in Korea

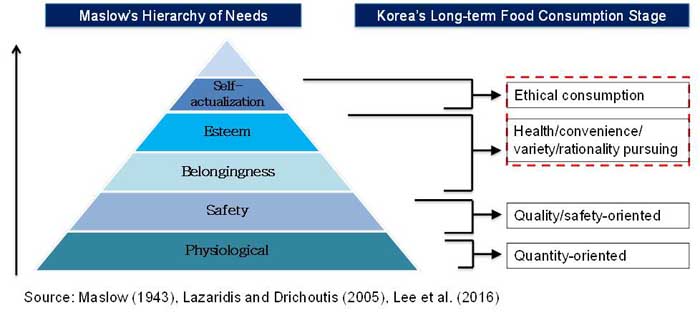

Many of the studies that have identified food consumption stages in the United States and EU countries are based on the Hierarchy of Needs proposed by Maslow (1943). For example, Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005) and Perianova (2012) classify and present food consumption stages by applying Maslow's hierarchical structure of needs. According to Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005), consumers want to meet their physiological needs first through food consumption. When the physiological needs are satisfied, people consume foods in a direction to pursue quality and safety. Foods are then consumed for promoting family harmony, displaying an appreciation (gift, etc.), revealing status or reputation, or expressing emotions or values.

To identify food consumption stages in Korea, we refer to the classification of food consumption stages of Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005) that apply Maslow's five-level needs hierarchy. The stage of fulfilling the quantity for avoiding hunger is equivalent to the ‘physiological stage’ and aims to meet minimum calories for survival. The quality-seeking stage is a stage where foods are consumed in a direction to pursue quality and health attributes, and corresponds to the second stage of Maslow's five-level hierarchy. At this stage, consumers will be interested in nutritional contents and food safety issue of foods, and will focus on the nutritional composition and food labeling of consumed foods. The diversification phase encompasses Maslow’s hierarchical structures 3 and 4, and is a stage in which characteristics such as simplicity, health/safety orientation, diversification/premium pursuit, and rationalized consumption behavior are expressed “simultaneously.” At the diversification stage, not only does it pursue high quality for physical/mental health needs like the second stage of the hierarchy of Maslow, but also pursue the family and social values and further self-realization through dietary life. At this stage, the importance of country of origin, and the expenditure on ethnic foods, HMR, and eating out increases. The ethical consumption stage corresponds to the fifth stage of the hierarchy of Maslow’s needs, and is a stage in which people consume foods based not only on their own preferences and utility maximization but also on their social/environmental concerns. In the ethical consumption stage, environment, animal welfare, organic farming, whether or not foods are genetically modified (GMO), and fair trade are attracting consumers’ attention.

Ethical consumption is moderately expanding in Korea, but it seems to be symbolic rather than a trend. Therefore, regarding ethical consumption as one of the various movements of the diversification food consumption stage in Korea is reasonable. Finally, it is recommended that the food consumption stage of Korea is classified into three stages of the fulfillment stage of quantity, the pursuit of quality, and the diversification stage (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs applied for food consumption trends

Increase in expenditure on foods away from home

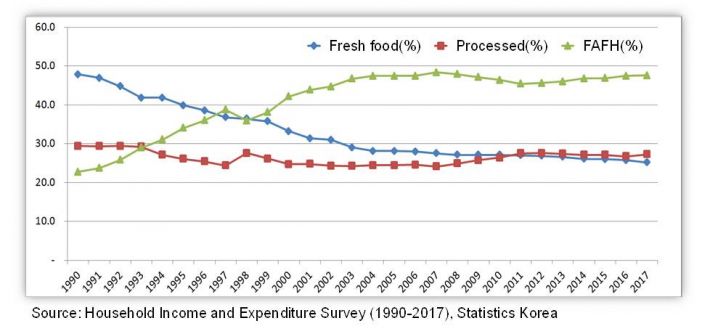

The most remarkable long-term change in the food consumption expenditure of Korean households is the decrease in expenditure on foods at home (FAH) and the increase in expenditure on foods away from home (FAFH). In the 1990s, the proportion of household expenditure on FAFH slightly exceeded 20%, but it has increased rapidly since then, reaching almost 50% in 2007. From 2007 onwards, it has maintained at 50% level. On the other hand, household spending on FAH, which is calculated by subtracting household spending on FAFH from total food expenditure, is steadily decreasing. More importantly, the share of fresh food expenditure in household expenditure on FAH is steadily decreasing, while the share of processed food expenditure is not significantly changed. This implies that an increase in household expenditure on FAFH has mainly crowded-out fresh food expenditure. The share of fresh food expenditure has been even lower than that of processed food expenditure since 2011, and the gap has remarkably expanded in 2017 (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Changes in household expenditure on fresh, processed foods and eating out

Expansion of HMR industry combined with growth of convenience stores

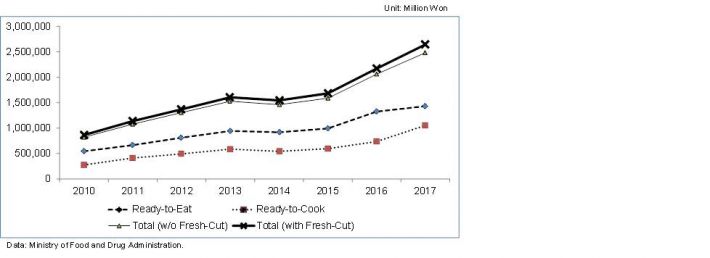

Another major change in food consumption in Korea is the rapid growth of the HMR (Home Meal Replacement) industry, which is combined with the growth of convenience stores as a distribution channel for foods. The HMR market is growing rapidly as the tendency to pursue simplification and diversification along with the improvement of living standards is spreading and the negative perception about processed foods is gradually resolved. The HMR market in Korea is steadily growing, especially since 2016. According to the Ministry of Food and Drug Administration, the market size was less than US$880 million in 2010(US$1=1,137 KRW), but grew to about US$2,375 million in 2017. As of 2017, ready-to-eat foods accounted for 54% of HMR market, US$1,258 million (increased by 8.0% from 2016), ready-to-cook foods and fresh-cut foods accounted for US$1,325 million (increased by 42.7% from 2016) and US$141 million (increased by 48.3% from 2016). The largest increase was observed for ready-to-cook food sales. It exceeded US$880 million for the first time in 2017 (see Fig. 3).

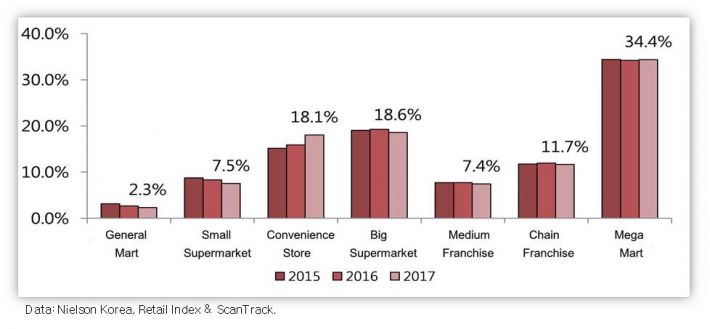

According to POS data analysis of Nielsen Korea, HMR’s main distribution channel is mega-mart (34.4%; e.g. E-mart) followed by big supermarkets (18.6%), convenience stores (18.1%) and chain franchise (11.7%). For three consecutive years since 2015, mega-mart accounted for over 33% of total distribution channels. The share of convenience stores has increased for three consecutive years since 2015, while general grocery stores and individual small businesses have had a downward trend in the recent three years (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. HMR Production

Fig. 4. HMR distribution channel

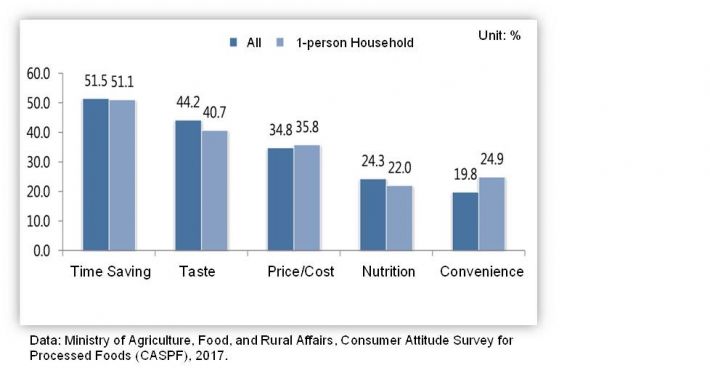

According to the results of the Consumer Attitude Survey for Processed Foods (CBSPF) in 2017, 51.5% of the respondents said that consumers purchases HMR because they can save cooking time (44.2%), HMR is cheaper than cooking (34.8%), and because HMR contains more balanced nutrition (24.3%) . In the case of single-person households, the reasons were either because it is relatively cheaper than direct cooking or because cooking meals are a complicated activity (see Fig. 5). As such, the recent HMR is a tool that quickly completes a meal in a busy modern life, and is recognized by consumers as a food with great taste and nutrition. It also meets reasonable and economical consumption patterns, and thus its market is expected to steadily grow as a new growth engine for the food industry and the beloved foods for future generations.

Fig. 5. Reason for HMR consumption

Strengthened preference for small-sized packages

One of the short-term but prominent features of food consumption behavior is the tendency to emphasize packaging. It is also noteworthy that the preference for small packages has been strengthened. In CBSF, information that consumers would like to check first when purchasing rice is investigated. Information that fell in importance in 2017 compared to 2016 was price, production area, country of origin, and rice varieties. On the other hand, information that consumers considered more important in 2016 compared to 2016 was the brand, the appearance of rice, whether it was certified eco-friendly, and packaging condition. The proportion of consumers who prefer to check packaging condition was only 0.2% in 2016, but it dramatically increased to 3.2% in 2017 (see Fig. 6).

.jpg)

Fig. 6. Information to check when purchasing rice: 2016 vs. 2017

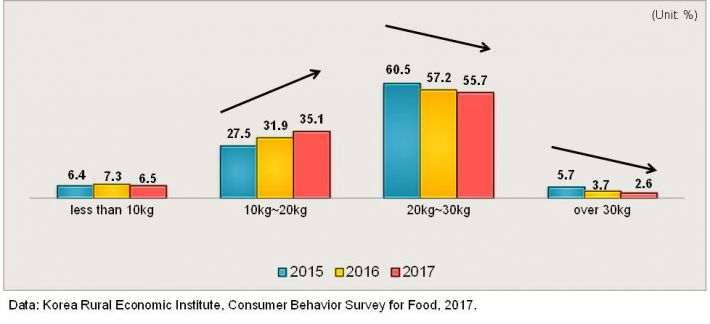

Looking at the purchase unit of rice, it is more conspicuous that consumption behavior changes into favoring small packages. The proportion of consumers buying rice in 10~20kg packages increased from 27.5% in 2015 to 35.1% in 2017. On the other hand, the percentage of consumers who purchase rice of 20~30kg or more than 30kg is decreasing for two consecutive years since 2015. In other words, consumers who bought more than 20kg of packaged rice now buy 10~20kg of small-packaged rice (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Unit of rice purchased

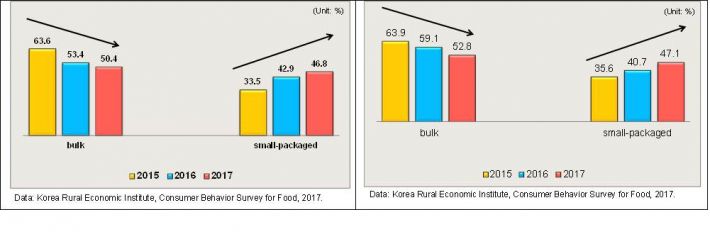

When purchasing fruits and vegetables, consumers are increasingly purchasing in small-sized packages rather than in bulk form. For example, the share of consumers purchasing fruits in bulk form, which accounted for 63.6% of the total in 2015, decreased gradually, reaching only 50.4% in 2017. On the other hand, the proportion of consumers purchasing fruits in the form of small packages has increased to 46.8%. It is checked that there is a similar pattern for vegetables. The important implication from this change is that when consumers buy fruits and vegetables, they are buying it in the form of small packages that are already packaged rather than putting it in the vinyl, weighing it on the scale, and buying it as much as they need (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Fruits (left) and vegetables (right) packages purchased

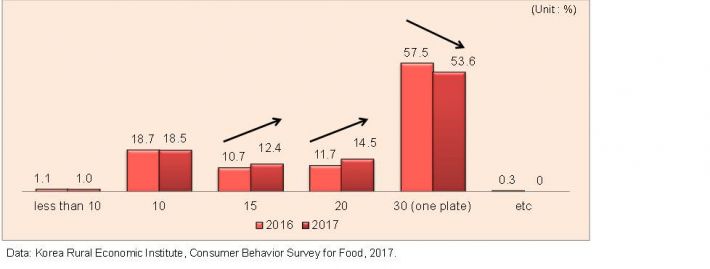

This preference for small-sized packages also appears for eggs which are widely eaten in Korea. The proportion of consumers who purchase eggs in 15 units or 20 units was low in 2016, but increased significantly in 2017. On the other hand, the share of consumers who purchase eggs in 30 units (1 egg plate) decreased by 4%p, thus supporting the preference of the small packages (see Fig. 9).

When purchasing Kimchi which is a representative traditional food of Korea, there is also an emerging preference for small-sized packaging. The proportion of consumers who purchase Kimchi less than 1kg or 2~4 kg has steadily increased for two consecutive years since 2015, while the proportion of consumers who purchase more than 10kg has decreased since 2015.

Fig. 9. Unit of eggs purchased

Emerging food attributes rather than price

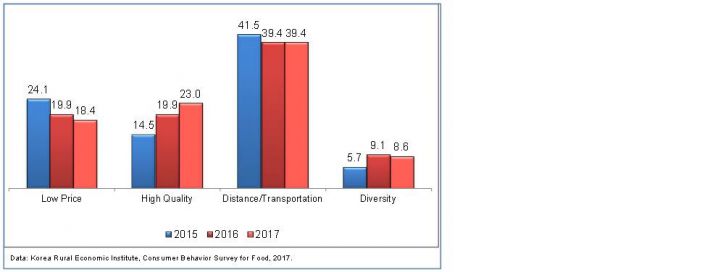

One of the salient features of recent food consumption behavior is that Korean households have begun to focus on other factors than price. It may be because of the increase in income level, and because the development of the Internet has made the information on the market more fully informative and consequently, the price has become closer to the price of perfectly competitive market. However, it is also highly possible that the attributes of foods which the consumers place emphasis on has changed. In the question about the reason for choosing the main shopping place, the proportion of consumers who answered that they chose main shopping place because of ‘low price’ decreased from 24.1% in 2015 to 18.4% in 2017. On the other hand, the proportion of consumers who responded that they chose the main shopping place because of ‘quality’ or ‘diversity’ of foods is steadily increasing. Consumers who responded that they chose the main shopping place due to the distance or transportation are also declining, which is possibly associated with the increase in online food purchases in Korea (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Reasons for choice of main shopping place

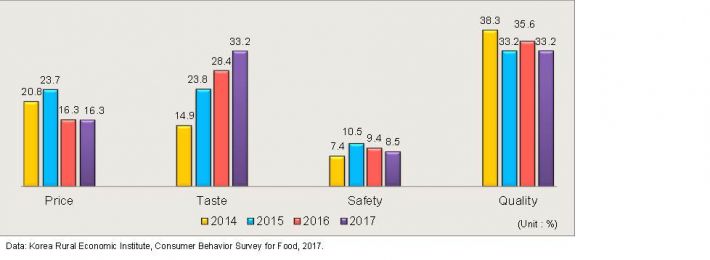

This phenomenon can be confirmed by the consumption behavior for various foods. For example, the percentage of consumers who consider prices first when purchasing rice is only 16.3% in 2017, the lowest among the last four years. On the other hand, the weight of taste is rapidly increasing for three consecutive years since 2014 (see Fig. 11). This reflects the recent changes in food consumption patterns that emphasize taste rather than price. This ‘taste-intensive tendency’ is similarly found for various foods.

Fig. 11. Factors to consider when purchasing rice

Soaring online food shopping

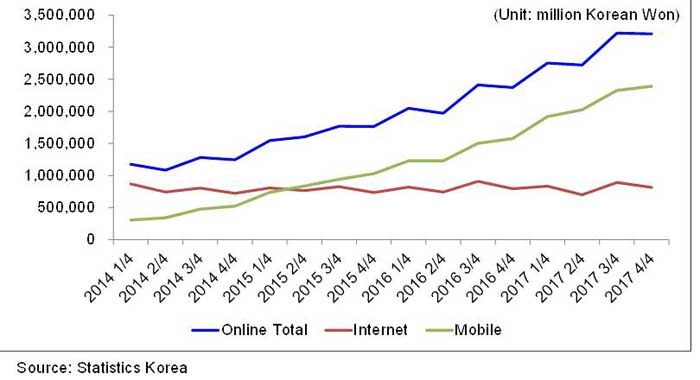

Another important change in food consumption in Korea is the sharp increase in online food shopping. In the first quarter of 2014, online food sales totaled 1.2 trillion Korean Won, surging to 3.4 trillion Korean Won in the fourth quarter of 2017. Much of this increase appears to be due to the increased food sales through mobile platform. Food sales through mobile platform amounted to about 0.3 trillion Korean Won in the first quarter of 2014, rising at a rate similar to that of total online food sales, rising to approximately 2.3 trillion KRW in the fourth quarter of 2017. On the other hand, food sales through the internet platform were 0.7~0.8 trillion Korean Won, showing no significant change during the last 12 quarters (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Online food sales

CONCLUSION

Agri-food consumption is changing very rapidly. It is thus essential to understand changes in food consumption as well as food consumption trends in order to present the right direction of food policy and agriculture. Based on the enhanced understanding on consumers and food consumption trends, policies could be newly introduced or improved in response to the changes in food consumption, and new opportunities for development in agriculture and the food industry could be discovered. Food consumption stage is classified into three stages in Korea: quantity-oriented, quality-oriented, and diversification stage. At the diversification stage of food consumption, consumer behaviors that pursue convenience, diversity, premium, health orientation, and rationality are simultaneously observed. In recent years in Korea, household expenditure on foods away from home has steadily increased, the HMR industry has rapidly grown, the consumer preference for small packages has strengthened, relative importance of other agri-food attributes rather than price has emphasized, and online food shopping has dramatically soared. Possible implications are that 1) labeling and provision of information on foods away from home, HMR, small-packaged products, and online-sold foods needs to be enhanced, 2) increased online transaction of agricultural produce addresses the necessity of tightened management of food safety, and 3) adding premium like taste and convenience into agricultural produce and food products could be a leading player for the steady growth of agriculture and the food industry.

REFERENCES

Kim, S.H. and S.Y. Heo, 2018. HMR Market Trend. Webzine of Korea Rural Economic Institute. (In Korean).

Lazaridis, P. and A.C. Drichoutis, 2005. Food Consumption Issues in the 21st Century. The food industry in Europe.

Lee, K.Y., S.H. Kim, and S.Y. Heo, 2016. In-Depth Analysis of Food Consumption in Korea. Korea Rural Economic Institute. (In Korean).

Maslow, A.H., 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50(4): 370-96.

Consumer Behavior Survey for Foods. 2014-2017. Korea Rural Economic Institute.

Consumer Attitude Survey for Processed Foods. 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Household Income and Expenditure Survey. 1990-2017. Statistics Korea.

Nielson Korea, Retail Index and ScanTrack.

Online Shopping Survey. 2014-2017. Statistics Korea.

Production of Food and Food Additives. 2014-2017. Ministry of Food and Drug Administration.

|

Date submitted: Oct. 28, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Nov. 13, 2018

|

Changes in Food Consumption in Korea

ABSTRACT

Household food consumption patterns in Korea are changing rapidly. These changes are caused by the changes in population and household structure, development of science and technology, climate change, and accelerated opening of the agri-food market (Lee et al., 2016). Since household food consumption behavior affects various areas such as personal nutrition and health status, food manufacturing and service industry, and government policy, it is necessary to continuously track and study the behavioral changes. This paper provides market and policy implications to agriculture and food industry as well as to the government by summarizing the changes in food consumption in Korea mainly based on a national survey conducted by the Korea Rural Economic Institute, which is named by “The Consumer Behavior Survey for Food (CBSF, hereafter),” as well as other national statistics related to food consumption.

Keywords: Consumer Behavior, Food Consumption, Household, Trends

INTRODUCTION

Food consumption and eating habits in Korea are changing rapidly. Since 2000, eating out has been expanding dramatically, and since 2015, consumption of HMR (home meal replacement) has continued to grow. As the lives of modern people are fundamentally complex, and the economic participation of women increases, the opportunity cost of preparing for meals at home has increased. In addition, evident consumer preference for ‘simplification’ or ‘simple life’ also contributes to the growth of restaurants and the HMR industry. As the number of single-person households increases, and as what we called the ‘eating along culture’ or ‘drinking alone culture’ is widely spreading, the preference for small-sized items for agri-food products is rapidly expanding. Food distribution channels are also changing. Online purchases of agri-food products are on the rise, and the same-day shipping and early morning delivery are becoming popular among Korean consumers. Food purchases at convenience stores are soaring, and consumption of imported foods is also increasing. In terms of dietary habits, nutritional imbalance is expanded due to an increase in animal food or fat intake, excessive diet (excessive rate of being on a diet), and an increase in rate of skipping breakfast meals. Furthermore, the prevalence of dietary-related diseases such as obesity and metabolic syndrome is also increasing.

As described above, agri-food consumption is changing very rapidly. It is thus essential to understand changes and trends in food consumption in order to present the right direction of food policy and agriculture. Based on the enhanced understanding on consumers and food consumption, policies could be newly introduced or improved in response to the changes in food consumption, and new opportunities for development in agriculture and the food industry could be discovered.

Long-term food consumption stage in Korea

Many of the studies that have identified food consumption stages in the United States and EU countries are based on the Hierarchy of Needs proposed by Maslow (1943). For example, Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005) and Perianova (2012) classify and present food consumption stages by applying Maslow's hierarchical structure of needs. According to Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005), consumers want to meet their physiological needs first through food consumption. When the physiological needs are satisfied, people consume foods in a direction to pursue quality and safety. Foods are then consumed for promoting family harmony, displaying an appreciation (gift, etc.), revealing status or reputation, or expressing emotions or values.

To identify food consumption stages in Korea, we refer to the classification of food consumption stages of Lazaridis and Drichoutis (2005) that apply Maslow's five-level needs hierarchy. The stage of fulfilling the quantity for avoiding hunger is equivalent to the ‘physiological stage’ and aims to meet minimum calories for survival. The quality-seeking stage is a stage where foods are consumed in a direction to pursue quality and health attributes, and corresponds to the second stage of Maslow's five-level hierarchy. At this stage, consumers will be interested in nutritional contents and food safety issue of foods, and will focus on the nutritional composition and food labeling of consumed foods. The diversification phase encompasses Maslow’s hierarchical structures 3 and 4, and is a stage in which characteristics such as simplicity, health/safety orientation, diversification/premium pursuit, and rationalized consumption behavior are expressed “simultaneously.” At the diversification stage, not only does it pursue high quality for physical/mental health needs like the second stage of the hierarchy of Maslow, but also pursue the family and social values and further self-realization through dietary life. At this stage, the importance of country of origin, and the expenditure on ethnic foods, HMR, and eating out increases. The ethical consumption stage corresponds to the fifth stage of the hierarchy of Maslow’s needs, and is a stage in which people consume foods based not only on their own preferences and utility maximization but also on their social/environmental concerns. In the ethical consumption stage, environment, animal welfare, organic farming, whether or not foods are genetically modified (GMO), and fair trade are attracting consumers’ attention.

Ethical consumption is moderately expanding in Korea, but it seems to be symbolic rather than a trend. Therefore, regarding ethical consumption as one of the various movements of the diversification food consumption stage in Korea is reasonable. Finally, it is recommended that the food consumption stage of Korea is classified into three stages of the fulfillment stage of quantity, the pursuit of quality, and the diversification stage (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs applied for food consumption trends

Increase in expenditure on foods away from home

The most remarkable long-term change in the food consumption expenditure of Korean households is the decrease in expenditure on foods at home (FAH) and the increase in expenditure on foods away from home (FAFH). In the 1990s, the proportion of household expenditure on FAFH slightly exceeded 20%, but it has increased rapidly since then, reaching almost 50% in 2007. From 2007 onwards, it has maintained at 50% level. On the other hand, household spending on FAH, which is calculated by subtracting household spending on FAFH from total food expenditure, is steadily decreasing. More importantly, the share of fresh food expenditure in household expenditure on FAH is steadily decreasing, while the share of processed food expenditure is not significantly changed. This implies that an increase in household expenditure on FAFH has mainly crowded-out fresh food expenditure. The share of fresh food expenditure has been even lower than that of processed food expenditure since 2011, and the gap has remarkably expanded in 2017 (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Changes in household expenditure on fresh, processed foods and eating out

Expansion of HMR industry combined with growth of convenience stores

Another major change in food consumption in Korea is the rapid growth of the HMR (Home Meal Replacement) industry, which is combined with the growth of convenience stores as a distribution channel for foods. The HMR market is growing rapidly as the tendency to pursue simplification and diversification along with the improvement of living standards is spreading and the negative perception about processed foods is gradually resolved. The HMR market in Korea is steadily growing, especially since 2016. According to the Ministry of Food and Drug Administration, the market size was less than US$880 million in 2010(US$1=1,137 KRW), but grew to about US$2,375 million in 2017. As of 2017, ready-to-eat foods accounted for 54% of HMR market, US$1,258 million (increased by 8.0% from 2016), ready-to-cook foods and fresh-cut foods accounted for US$1,325 million (increased by 42.7% from 2016) and US$141 million (increased by 48.3% from 2016). The largest increase was observed for ready-to-cook food sales. It exceeded US$880 million for the first time in 2017 (see Fig. 3).

According to POS data analysis of Nielsen Korea, HMR’s main distribution channel is mega-mart (34.4%; e.g. E-mart) followed by big supermarkets (18.6%), convenience stores (18.1%) and chain franchise (11.7%). For three consecutive years since 2015, mega-mart accounted for over 33% of total distribution channels. The share of convenience stores has increased for three consecutive years since 2015, while general grocery stores and individual small businesses have had a downward trend in the recent three years (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. HMR Production

Fig. 4. HMR distribution channel

According to the results of the Consumer Attitude Survey for Processed Foods (CBSPF) in 2017, 51.5% of the respondents said that consumers purchases HMR because they can save cooking time (44.2%), HMR is cheaper than cooking (34.8%), and because HMR contains more balanced nutrition (24.3%) . In the case of single-person households, the reasons were either because it is relatively cheaper than direct cooking or because cooking meals are a complicated activity (see Fig. 5). As such, the recent HMR is a tool that quickly completes a meal in a busy modern life, and is recognized by consumers as a food with great taste and nutrition. It also meets reasonable and economical consumption patterns, and thus its market is expected to steadily grow as a new growth engine for the food industry and the beloved foods for future generations.

Fig. 5. Reason for HMR consumption

Strengthened preference for small-sized packages

One of the short-term but prominent features of food consumption behavior is the tendency to emphasize packaging. It is also noteworthy that the preference for small packages has been strengthened. In CBSF, information that consumers would like to check first when purchasing rice is investigated. Information that fell in importance in 2017 compared to 2016 was price, production area, country of origin, and rice varieties. On the other hand, information that consumers considered more important in 2016 compared to 2016 was the brand, the appearance of rice, whether it was certified eco-friendly, and packaging condition. The proportion of consumers who prefer to check packaging condition was only 0.2% in 2016, but it dramatically increased to 3.2% in 2017 (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Information to check when purchasing rice: 2016 vs. 2017

Looking at the purchase unit of rice, it is more conspicuous that consumption behavior changes into favoring small packages. The proportion of consumers buying rice in 10~20kg packages increased from 27.5% in 2015 to 35.1% in 2017. On the other hand, the percentage of consumers who purchase rice of 20~30kg or more than 30kg is decreasing for two consecutive years since 2015. In other words, consumers who bought more than 20kg of packaged rice now buy 10~20kg of small-packaged rice (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Unit of rice purchased

When purchasing fruits and vegetables, consumers are increasingly purchasing in small-sized packages rather than in bulk form. For example, the share of consumers purchasing fruits in bulk form, which accounted for 63.6% of the total in 2015, decreased gradually, reaching only 50.4% in 2017. On the other hand, the proportion of consumers purchasing fruits in the form of small packages has increased to 46.8%. It is checked that there is a similar pattern for vegetables. The important implication from this change is that when consumers buy fruits and vegetables, they are buying it in the form of small packages that are already packaged rather than putting it in the vinyl, weighing it on the scale, and buying it as much as they need (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Fruits (left) and vegetables (right) packages purchased

This preference for small-sized packages also appears for eggs which are widely eaten in Korea. The proportion of consumers who purchase eggs in 15 units or 20 units was low in 2016, but increased significantly in 2017. On the other hand, the share of consumers who purchase eggs in 30 units (1 egg plate) decreased by 4%p, thus supporting the preference of the small packages (see Fig. 9).

When purchasing Kimchi which is a representative traditional food of Korea, there is also an emerging preference for small-sized packaging. The proportion of consumers who purchase Kimchi less than 1kg or 2~4 kg has steadily increased for two consecutive years since 2015, while the proportion of consumers who purchase more than 10kg has decreased since 2015.

Fig. 9. Unit of eggs purchased

Emerging food attributes rather than price

One of the salient features of recent food consumption behavior is that Korean households have begun to focus on other factors than price. It may be because of the increase in income level, and because the development of the Internet has made the information on the market more fully informative and consequently, the price has become closer to the price of perfectly competitive market. However, it is also highly possible that the attributes of foods which the consumers place emphasis on has changed. In the question about the reason for choosing the main shopping place, the proportion of consumers who answered that they chose main shopping place because of ‘low price’ decreased from 24.1% in 2015 to 18.4% in 2017. On the other hand, the proportion of consumers who responded that they chose the main shopping place because of ‘quality’ or ‘diversity’ of foods is steadily increasing. Consumers who responded that they chose the main shopping place due to the distance or transportation are also declining, which is possibly associated with the increase in online food purchases in Korea (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Reasons for choice of main shopping place

This phenomenon can be confirmed by the consumption behavior for various foods. For example, the percentage of consumers who consider prices first when purchasing rice is only 16.3% in 2017, the lowest among the last four years. On the other hand, the weight of taste is rapidly increasing for three consecutive years since 2014 (see Fig. 11). This reflects the recent changes in food consumption patterns that emphasize taste rather than price. This ‘taste-intensive tendency’ is similarly found for various foods.

Fig. 11. Factors to consider when purchasing rice

Soaring online food shopping

Another important change in food consumption in Korea is the sharp increase in online food shopping. In the first quarter of 2014, online food sales totaled 1.2 trillion Korean Won, surging to 3.4 trillion Korean Won in the fourth quarter of 2017. Much of this increase appears to be due to the increased food sales through mobile platform. Food sales through mobile platform amounted to about 0.3 trillion Korean Won in the first quarter of 2014, rising at a rate similar to that of total online food sales, rising to approximately 2.3 trillion KRW in the fourth quarter of 2017. On the other hand, food sales through the internet platform were 0.7~0.8 trillion Korean Won, showing no significant change during the last 12 quarters (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Online food sales

CONCLUSION

Agri-food consumption is changing very rapidly. It is thus essential to understand changes in food consumption as well as food consumption trends in order to present the right direction of food policy and agriculture. Based on the enhanced understanding on consumers and food consumption trends, policies could be newly introduced or improved in response to the changes in food consumption, and new opportunities for development in agriculture and the food industry could be discovered. Food consumption stage is classified into three stages in Korea: quantity-oriented, quality-oriented, and diversification stage. At the diversification stage of food consumption, consumer behaviors that pursue convenience, diversity, premium, health orientation, and rationality are simultaneously observed. In recent years in Korea, household expenditure on foods away from home has steadily increased, the HMR industry has rapidly grown, the consumer preference for small packages has strengthened, relative importance of other agri-food attributes rather than price has emphasized, and online food shopping has dramatically soared. Possible implications are that 1) labeling and provision of information on foods away from home, HMR, small-packaged products, and online-sold foods needs to be enhanced, 2) increased online transaction of agricultural produce addresses the necessity of tightened management of food safety, and 3) adding premium like taste and convenience into agricultural produce and food products could be a leading player for the steady growth of agriculture and the food industry.

REFERENCES

Kim, S.H. and S.Y. Heo, 2018. HMR Market Trend. Webzine of Korea Rural Economic Institute. (In Korean).

Lazaridis, P. and A.C. Drichoutis, 2005. Food Consumption Issues in the 21st Century. The food industry in Europe.

Lee, K.Y., S.H. Kim, and S.Y. Heo, 2016. In-Depth Analysis of Food Consumption in Korea. Korea Rural Economic Institute. (In Korean).

Maslow, A.H., 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50(4): 370-96.

Consumer Behavior Survey for Foods. 2014-2017. Korea Rural Economic Institute.

Consumer Attitude Survey for Processed Foods. 2017. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Household Income and Expenditure Survey. 1990-2017. Statistics Korea.

Nielson Korea, Retail Index and ScanTrack.

Online Shopping Survey. 2014-2017. Statistics Korea.

Production of Food and Food Additives. 2014-2017. Ministry of Food and Drug Administration.

Date submitted: Oct. 28, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Nov. 13, 2018