Introduction

Hokkaido is the northernmost prefecture in Japan, agriculture being one of its main industries. Unlike the other 46 prefectures, large-size farming is dominant in Hokkaido. Many farms here suffer from labor shortage. This is because Japanese laborers’ lifestyle is so urbanized that they avoid manual labor such as farming. Therefore, demand for foreign manual laborers is surging among Hokkaido farms. However, the Japanese government holds the principle that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan, a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that unskilled foreign laborers may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the social order of the local community. Consequently, numerous Hokkaido farms “employ” de facto unskilled foreign laborers under the pretense of training. Those laborers are commonly called Jisshusei (literal translation is “trainees from foreign countries”). As discussed in previous studies, Jisshusei are often enforced to work under unfavorable conditions1. As a result, Japan’s training schemes for foreigners have received severe criticism from human rights groups, both inside and outside Japan.

Previous papers use data on Jisshusei collected for the national and Hokkaido levels2. As such, agricultural cooperatives often play a key role as an intermediary body when Jisshusei join farms in Japan. By focusing on a case of an anonymous agricultural cooperative in Hokkaido, thereafter called Agri. Co-op X, this paper discusses problems and possible solutions of the Jisshusei system.

Legal framework of the Jisshusei system

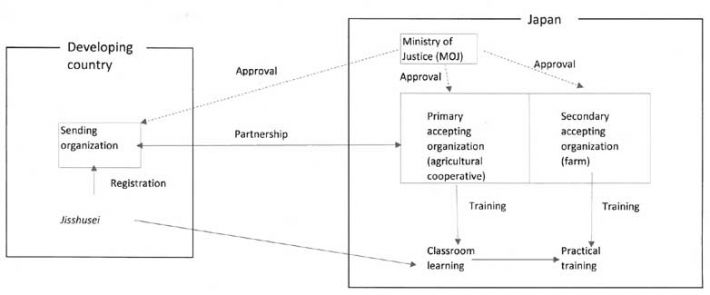

Before discussing the case study of Agri. Co-op X, we review how Japanese farms accept Jisshusei under the pretense of training. Figure 1 shows the basic structure of the training system3.

The training system is carried out under a partnership between a sending organization in a foreign country and accepting organizations in Japan. There are two types of accepting organizations: primary accepting organization, which provides classroom learning, and secondary, which provides practical training. By registering itself as a secondary accepting organization, a farm receives Jisshusei under the pretense of training. There are regulations on the number of Jisshusei allowed for a farm. If a farm has a corporate status, it is allowed up to three Jisshusei and two otherwise.

Fig. 1. The legal framework of the Jisshusei system

Those who want to stay in Japan as Jisshusei need to register as regular members of a sending organization in their country. Subsequently, each Jisshusei submits details of his/her training plan to the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), which is in charge of immigration regulations. Once the plan is approved and the person enters Japan, he/she first goes to a primary accepting organization and, then, to a secondary accepting organization.

There are various regulations on the activities of Jisshusei. Each must specify one from the 144 jobs listed by the MOJ4. He/she is not allowed to change the accepting organizations and job type after entrance in Japan. Additionally, once a Jisshusei returns to his/her country of origin after completing the training program, he/she cannot re-enter Japan as a trainee5.

There are various types of primary accepting organizations. The most popular ones are agricultural cooperatives, established in 1947 in every community, and have been engaged in various types of agriculture-related activities. Member farms tend to exert strong pressure on agricultural cooperatives to register as primary accepting organizations, particularly in areas facing serious labor shortage. However, an agricultural cooperative face difficulties if it registers as a primary accepting organization. Sometimes, fearing that the burden exceeds their management ability, agricultural cooperatives refuse member farms’ requests. In that case, farms are forced to look for an alternative such as a chamber of commerce and industry6.

Jisshusei are allowed to stay in Japan for a maximum of three years. Previously, the MOJ treated them differently depending on their period of stay. For the first year, they were recognized as trainees in the Status of Residence list. The MOJ did not admit a labor–management relationship between a trainee and a secondary accepting organization because the nature of work to be performed by a trainee is supposed to be entirely different from that performed by a laborer. Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work is termed as “compensation” for necessary expenses for his/her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Law was not be applicable to trainees. For the second and third years, by updating their status from trainees to “technical intern trainees,” Jisshusei are allowed to continue work with the secondary accepting organization7. Unlike a trainee, the relationship between a farm and a technical intern trainee is recognized as a labor relationship. This is because the MOJ assumes that a technical intern trainee is an individual learning advanced and practical skills through labor. Therefore, the payments from a farm to a technical intern trainee are considered salaries. Additionally, various regulations of the Labor Standards Law, such as maximum hours of overtime and minimum wage, are applicable to technical intern trainees.

In reality, the work does not change even after updating status from trainees to technical intern trainees. Therefore, domestic and international human rights organizations criticized the Japanese government for not regulating working conditions for trainees. For example, during the 94th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council at Geneva in October 2008, the Japanese government encountered severe criticisms for failure to protect trainees’human rights. In response, the MOJ revised its treatment of Jisshusei in July 2010, establishing two categories in the Status of Residence list: “technical interns training (i),” applied to Jisshusei in their first year in Japan, and “technical interns training (ii),” applied in their second and third year in Japan. This revision means that the MOJ admits a labor–management relationship between each Jisshusei and a secondary accepting organization from his/her first year in Japan. Accordingly, all payments from a secondary accepting organization to Jisshusei are now recognized as salaries.

However, it is unclear how much this revision improved the working conditions of Jisshusei. In practice, a serious problem is that many Jisshusei are in significantly disadvantageous positions. Often, a sending organization collects a large amount of money as a deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as Jisshusei. In this case, the deposit will not be returned to the Jisshusei unless they complete all the jobs in Japan without issues. As such, the secondary accepting organizations are in a stronger position than the Jisshusei are. Indeed, Jisshusei are allegedly often forced to do difficult jobs under tougher working conditions than the original training plan submitted to the MOJ. If such inappropriate practices become public, the training program is cancelled and the person in the program is required to return to his/her country of origin without finishing all the jobs scheduled. Fearing that the sending organization will not return the deposit, a trainee does not report inadequate workplace treatment. Therefore, the human rights of Jisshusei are allegedly not enforced even after the revision of the training system in 2010. This has received significant attention among human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan8.

History of the Jisshusei system in City X

Agri. Co-op X is located in City X, a rural city in the northern part of Hokkaido. The jurisdiction of Agri. Co-op X is the same as that of the municipal government of City X. All farms in City X belong to Agri. Co-op X as regular members.

Previously, there were three agricultural cooperatives in City X: Agri. Co-op. Xa, Xb, and Xc (the jurisdiction of today’s Agri. Co-op X was divided into three areas and each area has its own agricultural cooperative). Merging these three agricultural cooperatives, Agri. Co-op X was established in 2005 (hereafter, the Agri. Co-op Xa, Xb, and Xc before 2005 are referred to Agri. Co-op X in this paper unless mentioned otherwise).

There are 934 farms in City X. Their major agricultural products are pumpkin, asparagus, potato, beet, sweet corn, wheat, and onion. Winter in City X is long and cold, which is why field-farming activities are only held from May to October.

The acceptance of Jisshusei started in 1996, when Agri. Co-op Xa registered itself as a primary accepting organization and accepted nine Chinese trainees. The other two agricultural cooperatives also registered themselves as primary accepting organizations in 1997. There has been no primary accepting organization other than Agri. Co-op X that connects Jisshusei to farms in City X.

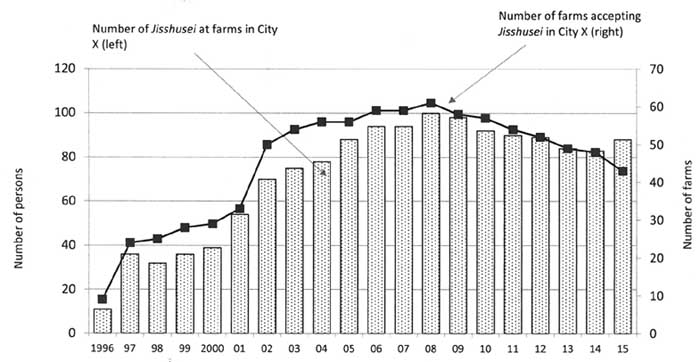

Fig. 2 shows changes in the total numbers of farms that accept Jisshusei through Agri. Co-op X and the total number of Jisshusei at farms in City X, all being from China and returning within a year except with few exceptions. Both totals in Fig. 2 increased until 2005 and started declining since then. As discussed later, this decline does not mean decreased demand for Jisshusei at farms in City X. Conversely, while demand keeps increasing, it is becoming more and more difficult to attract sufficient Jisshusei from China.

As of 2014, 48 farms accepted 83 Jisshusei from 20 to 39 years old. Almost half of them are male and most are married.

Among the 48 farms, only one has corporate status and accepts three Jisshusei. While, previously, another farm with corporate status received Jisshusei, it stopped when the MOJ revised the legal status of Jisshusei in 2010.

Fig. 2. Numbers of farms accepting Jisshusei in City X and number of Jisshusei at farms in City X

Source: Business records of Agri. Co-op X.

Details of Agri. Co-op X’s activities as a primary accepting organization

Agri. Co-op X has regular staff of 101. Three of them are exclusively engaged in carrying out the Jisshusei system. One of them is Chinese (male), whose wife is also Chinese and is engaged in taking care of Jisshusei as needed9.

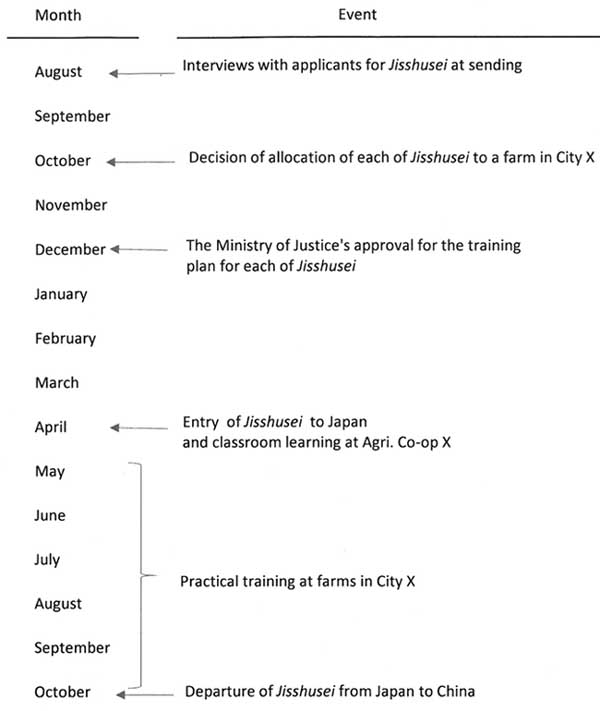

Fig. 3 shows a typical schedule of carrying out the Jisshusei system. Agri. Co-op X partnered with two sending organizations in China: one is in Shandong Province and the other in Jiangsu Province. These two sending organizations are in charge of receiving applications for Jisshusei. In the middle of August, five employees of Agri. Co-op X, namely the above-mentioned three and two board members, go to the sending organizations and decide on the successful applicants after the interview. In October, Agri. Co-op X determines farm allocation for each Jisshusei and prepares documents for the MOJ.

In April, Jisshusei arrive in City X and receive classroom training under the supervision of Agri. Co-op X. Here, in addition to Japanese language training and outline of farming jobs, Agri. Co-op X arranges lectures on the lifestyle of City X, such as public waste disposal service, traffic regulations, public health services, evacuation grills, and crime prevention system. To do so, Agri. Co-op X cooperates with various public authorities, such as the municipal office, police office, health center, and fire station.

Agri. Co-op X makes special efforts to find lodging for Jisshusei. Although Agri. Co-op X owns apartments, most of them are occupied by the families of its staff, making it impossible to accommodate all Jisshusei there. Thus, Agri. Co-op X leases of City X’s public housings, community halls, and empty houses as accommodation for Jisshusei during their stay in City X. They are divided into groups of six to 17 persons and live together at those locations10.

Fig. 3. Typical schedule of carrying out the Jisshusei system in City X

Source: The authors' interview at Agri. Co-op X.

Farm cost for accepting a Jisshusei

A Jisshusei’s salary is around JPY 120,000 per month. This is almost equivalent to the minimum wage in Hokkaido11. Additionally, farms need to pay for labor insurance when they accept Jisshusei, which costs cost nearly JPY 250,000 for each Gaikokujin Kenshusei. Since classroom training at Agri. Co-op X in April is included in the training period, a farm must pay salaries for seven months. Before the revision of Jisshusei in 2010, farmers paid only JPY 65,000 to each Jisshusei as “compensation” and did not buy labor insurance. As such, the revision of the status of Jisshusei in 2010 increased the financial burden of farms significantly12.

Moreover, in order to accept Jisshusei, farms must pay for commissions and necessary expenses to Agri. Co-op X and sending organizations in China. Basic payments to Agri. Co-op X and sending organizations are JPY 45,500 and JPY 90,000, respectively, for each Jisshusei. Besides these basic payments, farms need to pay around JPY 100,000 or more for each Jisshusei to Agri. Co-op X as compensation for Agri. Co-op X’s extra necessary expenses of caring for the trainees. As such, the total cost of accepting a Jisshusei is around JPY 1 million per year.

Agri. Co-op X’s problems in carrying out the Jisshusei system

Previous studies mention that Japan’s Jisshusei system is infamous because of various issues, such as ignoring minimum wage regulations, employer harassment to employee rights violations, and runaways from accepting organizations, often arouse13. However, Agri. Co-op X has been regarded as an exceptional case, being often called “the model agricultural cooperative” of a primary accepting organization14.

There are two major points that make Agri. Co-op X different from other agricultural cooperatives. First, as mentioned above, two of the staff are Chinese, with a good understanding of Chinese mentality and culture. If any Jisshusei is confronted with a problem, Agri. Co-op X is able to provide support. For example, the staff of Agri. Co-op X always attend to any Jisshusei who is sick and needs medical treatment.

Second, Agri. Co-op X has a unique inner organization, called Gaikokujin Ginou Jisshusei Ukeire Kyogikai (abbreviated as Kyogikai hereafter)15. All farms that accept Jisshusei are obliged to adhere to Kyogikai. Through Kyogikai, Agri. Co-op X provides careful and meticulous guidance to farms on how to maintain good communication with the Jisshusei, emphasizing the importance of forming a family-like atmosphere between employer and an employee.

However, there are still issues with Jisshusei at farms in City X. Their total number from 1996 to 2014 is 1,343. Among them, six ran away from farms, 42 persons returned to China without completing the training program because of homesickness, injuries, and lethargy.

The most serious problem for Agri. Co-op X is collecting sufficient applications for Jisshusei from China. This reflects the increase of wage rates and the anti-Japan sentiment in China. On the other hand, by interviewing at Agri. Co-op X and farms in City X, we find that demands for Jisshusei from farms are increasing because of the aging and depopulation of City X.

One possible solution is finding sending organizations in other countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines. Indeed, there are such movements among the primary accepting organizations in Hokkaido16. However, Agri. Co-op X has already employed two Chinese on its staff and accumulated experience on how to socialize with Chinese farming laborers. Therefore, if Agri. Co-op X changes current sending organizations to those outside China, these resources become useless. Additionally, there is no guarantee Agri. Co-op X can find a partners outside China17.

A solution could be the revision of Japan’s immigration policy. For example, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations recommends the government to consider alternatives to resist the acceptance of unskilled foreign laborers, and officially opening the Japanese labor market to manpower in developing countries by establishing a formal framework for receiving unskilled laborers18.

Without Jisshusei, farms in City X will sustain a significant loss. The case of Agri. Co-op X illustrates the limits of today’s Gaikokujin Kenshusei system.

Footnotes

- Godo, Y., “Unskilled Foreign Laborers in Japanese Food Processing Companies and Farms under the Pretense of Training,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region) August 3, 2016 (downloadable at http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=662 ); Godo, Y., and T. Miyairi, “Unskilled Foreign Laborers Employed in Hokkaido Food Industries Under the Pretense of Training,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (Food & Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region) September 1, 2016 (downloadable at http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=671 ).

- See Godo (ibid.) and Godo and Miyairi (ibid).

- This study provides an overview of the “training” system. For further details, see Godo (ibid.).

- The list is available at http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11800000-Shokugyounouryokuka...

- There are a few exceptions to this rule. However, the difficulty is rather high.

- Since major members of chambers of commerce and industry are commercial and manufacturing companies, they often keep a distance from farming businesses. Thus, it is not easy for farmers to use a chamber of commerce and industry as a primary accepting organization.

- In order to upgrade the status from “trainee” to “technical intern trainee,” the accepting organization must attest that he/she has already acquired technical skills equivalent with the Basic 2-Level in the National Technical Skill Test. However, this is not a difficult condition. In reality, whether the trainee will continue to stay in Japan by upgrading his/her status is determined before he or she enters Japan.

- For example, see the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, “Gaikokujin Gino Seido No Sokyu No Haishi Wo Motomeru Ikensho” (A Proposal to Abolish Technical Intern Training Program), June 2013.

- Usually, she works in different section of Agri. Co-op X as a part-time worker.

- In grouping, Agri. Co-op X pays special attention to the eating habits of each Jisshusei. If those who have different eating habits live together, arguments often start between them.

- Based on the Minimum Wage Law, the Hokkaido Prefectural Labor Bureaus determines the minimum wage in Hokkaido.

- The inflation rate in Japan is close to zero during these two decades.

- Godo (ibid.) and Godo and Miyairi (ibid).

- The Japanese Gaikokujin Ginou Jisshusei Ukeire Kyogikai translates as “the association of those who accept technical intern trainee.”

- See Miyairi, T., “Hokkaido Nokyo Ni Okeru Gaikokujin Gino Jisshusei No Ukeire Jittai to Kadai (Case Study of Agricultural Cooperatives’ Treatment of Technical Intern Trainees in Hokkaido), Kaihatsu Ronshu (Development Research Institute), Hokkai Gakuen University, No. 96. September 2015.

- Godo and Miyairi (ibid).

- We find that several agricultural cooperatives in Hokkaido that switched from Chinese to Vietnamese laborers had been involved in serious problems with the new sending organizations.

- For example, see the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (ibid.).

|

Date submitted: Jan. 16, 2017

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Jan. 16, 2017

|

Case Study of Farm Employment of Unskilled Foreign Laborers through an Agricultural Cooperative in Hokkaido

Introduction

Hokkaido is the northernmost prefecture in Japan, agriculture being one of its main industries. Unlike the other 46 prefectures, large-size farming is dominant in Hokkaido. Many farms here suffer from labor shortage. This is because Japanese laborers’ lifestyle is so urbanized that they avoid manual labor such as farming. Therefore, demand for foreign manual laborers is surging among Hokkaido farms. However, the Japanese government holds the principle that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan, a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that unskilled foreign laborers may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the social order of the local community. Consequently, numerous Hokkaido farms “employ” de facto unskilled foreign laborers under the pretense of training. Those laborers are commonly called Jisshusei (literal translation is “trainees from foreign countries”). As discussed in previous studies, Jisshusei are often enforced to work under unfavorable conditions1. As a result, Japan’s training schemes for foreigners have received severe criticism from human rights groups, both inside and outside Japan.

Previous papers use data on Jisshusei collected for the national and Hokkaido levels2. As such, agricultural cooperatives often play a key role as an intermediary body when Jisshusei join farms in Japan. By focusing on a case of an anonymous agricultural cooperative in Hokkaido, thereafter called Agri. Co-op X, this paper discusses problems and possible solutions of the Jisshusei system.

Legal framework of the Jisshusei system

Before discussing the case study of Agri. Co-op X, we review how Japanese farms accept Jisshusei under the pretense of training. Figure 1 shows the basic structure of the training system3.

The training system is carried out under a partnership between a sending organization in a foreign country and accepting organizations in Japan. There are two types of accepting organizations: primary accepting organization, which provides classroom learning, and secondary, which provides practical training. By registering itself as a secondary accepting organization, a farm receives Jisshusei under the pretense of training. There are regulations on the number of Jisshusei allowed for a farm. If a farm has a corporate status, it is allowed up to three Jisshusei and two otherwise.

Fig. 1. The legal framework of the Jisshusei system

Those who want to stay in Japan as Jisshusei need to register as regular members of a sending organization in their country. Subsequently, each Jisshusei submits details of his/her training plan to the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), which is in charge of immigration regulations. Once the plan is approved and the person enters Japan, he/she first goes to a primary accepting organization and, then, to a secondary accepting organization.

There are various regulations on the activities of Jisshusei. Each must specify one from the 144 jobs listed by the MOJ4. He/she is not allowed to change the accepting organizations and job type after entrance in Japan. Additionally, once a Jisshusei returns to his/her country of origin after completing the training program, he/she cannot re-enter Japan as a trainee5.

There are various types of primary accepting organizations. The most popular ones are agricultural cooperatives, established in 1947 in every community, and have been engaged in various types of agriculture-related activities. Member farms tend to exert strong pressure on agricultural cooperatives to register as primary accepting organizations, particularly in areas facing serious labor shortage. However, an agricultural cooperative face difficulties if it registers as a primary accepting organization. Sometimes, fearing that the burden exceeds their management ability, agricultural cooperatives refuse member farms’ requests. In that case, farms are forced to look for an alternative such as a chamber of commerce and industry6.

Jisshusei are allowed to stay in Japan for a maximum of three years. Previously, the MOJ treated them differently depending on their period of stay. For the first year, they were recognized as trainees in the Status of Residence list. The MOJ did not admit a labor–management relationship between a trainee and a secondary accepting organization because the nature of work to be performed by a trainee is supposed to be entirely different from that performed by a laborer. Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work is termed as “compensation” for necessary expenses for his/her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Law was not be applicable to trainees. For the second and third years, by updating their status from trainees to “technical intern trainees,” Jisshusei are allowed to continue work with the secondary accepting organization7. Unlike a trainee, the relationship between a farm and a technical intern trainee is recognized as a labor relationship. This is because the MOJ assumes that a technical intern trainee is an individual learning advanced and practical skills through labor. Therefore, the payments from a farm to a technical intern trainee are considered salaries. Additionally, various regulations of the Labor Standards Law, such as maximum hours of overtime and minimum wage, are applicable to technical intern trainees.

In reality, the work does not change even after updating status from trainees to technical intern trainees. Therefore, domestic and international human rights organizations criticized the Japanese government for not regulating working conditions for trainees. For example, during the 94th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council at Geneva in October 2008, the Japanese government encountered severe criticisms for failure to protect trainees’human rights. In response, the MOJ revised its treatment of Jisshusei in July 2010, establishing two categories in the Status of Residence list: “technical interns training (i),” applied to Jisshusei in their first year in Japan, and “technical interns training (ii),” applied in their second and third year in Japan. This revision means that the MOJ admits a labor–management relationship between each Jisshusei and a secondary accepting organization from his/her first year in Japan. Accordingly, all payments from a secondary accepting organization to Jisshusei are now recognized as salaries.

However, it is unclear how much this revision improved the working conditions of Jisshusei. In practice, a serious problem is that many Jisshusei are in significantly disadvantageous positions. Often, a sending organization collects a large amount of money as a deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as Jisshusei. In this case, the deposit will not be returned to the Jisshusei unless they complete all the jobs in Japan without issues. As such, the secondary accepting organizations are in a stronger position than the Jisshusei are. Indeed, Jisshusei are allegedly often forced to do difficult jobs under tougher working conditions than the original training plan submitted to the MOJ. If such inappropriate practices become public, the training program is cancelled and the person in the program is required to return to his/her country of origin without finishing all the jobs scheduled. Fearing that the sending organization will not return the deposit, a trainee does not report inadequate workplace treatment. Therefore, the human rights of Jisshusei are allegedly not enforced even after the revision of the training system in 2010. This has received significant attention among human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan8.

History of the Jisshusei system in City X

Agri. Co-op X is located in City X, a rural city in the northern part of Hokkaido. The jurisdiction of Agri. Co-op X is the same as that of the municipal government of City X. All farms in City X belong to Agri. Co-op X as regular members.

Previously, there were three agricultural cooperatives in City X: Agri. Co-op. Xa, Xb, and Xc (the jurisdiction of today’s Agri. Co-op X was divided into three areas and each area has its own agricultural cooperative). Merging these three agricultural cooperatives, Agri. Co-op X was established in 2005 (hereafter, the Agri. Co-op Xa, Xb, and Xc before 2005 are referred to Agri. Co-op X in this paper unless mentioned otherwise).

There are 934 farms in City X. Their major agricultural products are pumpkin, asparagus, potato, beet, sweet corn, wheat, and onion. Winter in City X is long and cold, which is why field-farming activities are only held from May to October.

The acceptance of Jisshusei started in 1996, when Agri. Co-op Xa registered itself as a primary accepting organization and accepted nine Chinese trainees. The other two agricultural cooperatives also registered themselves as primary accepting organizations in 1997. There has been no primary accepting organization other than Agri. Co-op X that connects Jisshusei to farms in City X.

Fig. 2 shows changes in the total numbers of farms that accept Jisshusei through Agri. Co-op X and the total number of Jisshusei at farms in City X, all being from China and returning within a year except with few exceptions. Both totals in Fig. 2 increased until 2005 and started declining since then. As discussed later, this decline does not mean decreased demand for Jisshusei at farms in City X. Conversely, while demand keeps increasing, it is becoming more and more difficult to attract sufficient Jisshusei from China.

As of 2014, 48 farms accepted 83 Jisshusei from 20 to 39 years old. Almost half of them are male and most are married.

Among the 48 farms, only one has corporate status and accepts three Jisshusei. While, previously, another farm with corporate status received Jisshusei, it stopped when the MOJ revised the legal status of Jisshusei in 2010.

Fig. 2. Numbers of farms accepting Jisshusei in City X and number of Jisshusei at farms in City X

Source: Business records of Agri. Co-op X.

Details of Agri. Co-op X’s activities as a primary accepting organization

Agri. Co-op X has regular staff of 101. Three of them are exclusively engaged in carrying out the Jisshusei system. One of them is Chinese (male), whose wife is also Chinese and is engaged in taking care of Jisshusei as needed9.

Fig. 3 shows a typical schedule of carrying out the Jisshusei system. Agri. Co-op X partnered with two sending organizations in China: one is in Shandong Province and the other in Jiangsu Province. These two sending organizations are in charge of receiving applications for Jisshusei. In the middle of August, five employees of Agri. Co-op X, namely the above-mentioned three and two board members, go to the sending organizations and decide on the successful applicants after the interview. In October, Agri. Co-op X determines farm allocation for each Jisshusei and prepares documents for the MOJ.

In April, Jisshusei arrive in City X and receive classroom training under the supervision of Agri. Co-op X. Here, in addition to Japanese language training and outline of farming jobs, Agri. Co-op X arranges lectures on the lifestyle of City X, such as public waste disposal service, traffic regulations, public health services, evacuation grills, and crime prevention system. To do so, Agri. Co-op X cooperates with various public authorities, such as the municipal office, police office, health center, and fire station.

Agri. Co-op X makes special efforts to find lodging for Jisshusei. Although Agri. Co-op X owns apartments, most of them are occupied by the families of its staff, making it impossible to accommodate all Jisshusei there. Thus, Agri. Co-op X leases of City X’s public housings, community halls, and empty houses as accommodation for Jisshusei during their stay in City X. They are divided into groups of six to 17 persons and live together at those locations10.

Fig. 3. Typical schedule of carrying out the Jisshusei system in City X

Source: The authors' interview at Agri. Co-op X.

Farm cost for accepting a Jisshusei

A Jisshusei’s salary is around JPY 120,000 per month. This is almost equivalent to the minimum wage in Hokkaido11. Additionally, farms need to pay for labor insurance when they accept Jisshusei, which costs cost nearly JPY 250,000 for each Gaikokujin Kenshusei. Since classroom training at Agri. Co-op X in April is included in the training period, a farm must pay salaries for seven months. Before the revision of Jisshusei in 2010, farmers paid only JPY 65,000 to each Jisshusei as “compensation” and did not buy labor insurance. As such, the revision of the status of Jisshusei in 2010 increased the financial burden of farms significantly12.

Moreover, in order to accept Jisshusei, farms must pay for commissions and necessary expenses to Agri. Co-op X and sending organizations in China. Basic payments to Agri. Co-op X and sending organizations are JPY 45,500 and JPY 90,000, respectively, for each Jisshusei. Besides these basic payments, farms need to pay around JPY 100,000 or more for each Jisshusei to Agri. Co-op X as compensation for Agri. Co-op X’s extra necessary expenses of caring for the trainees. As such, the total cost of accepting a Jisshusei is around JPY 1 million per year.

Agri. Co-op X’s problems in carrying out the Jisshusei system

Previous studies mention that Japan’s Jisshusei system is infamous because of various issues, such as ignoring minimum wage regulations, employer harassment to employee rights violations, and runaways from accepting organizations, often arouse13. However, Agri. Co-op X has been regarded as an exceptional case, being often called “the model agricultural cooperative” of a primary accepting organization14.

There are two major points that make Agri. Co-op X different from other agricultural cooperatives. First, as mentioned above, two of the staff are Chinese, with a good understanding of Chinese mentality and culture. If any Jisshusei is confronted with a problem, Agri. Co-op X is able to provide support. For example, the staff of Agri. Co-op X always attend to any Jisshusei who is sick and needs medical treatment.

Second, Agri. Co-op X has a unique inner organization, called Gaikokujin Ginou Jisshusei Ukeire Kyogikai (abbreviated as Kyogikai hereafter)15. All farms that accept Jisshusei are obliged to adhere to Kyogikai. Through Kyogikai, Agri. Co-op X provides careful and meticulous guidance to farms on how to maintain good communication with the Jisshusei, emphasizing the importance of forming a family-like atmosphere between employer and an employee.

However, there are still issues with Jisshusei at farms in City X. Their total number from 1996 to 2014 is 1,343. Among them, six ran away from farms, 42 persons returned to China without completing the training program because of homesickness, injuries, and lethargy.

The most serious problem for Agri. Co-op X is collecting sufficient applications for Jisshusei from China. This reflects the increase of wage rates and the anti-Japan sentiment in China. On the other hand, by interviewing at Agri. Co-op X and farms in City X, we find that demands for Jisshusei from farms are increasing because of the aging and depopulation of City X.

One possible solution is finding sending organizations in other countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines. Indeed, there are such movements among the primary accepting organizations in Hokkaido16. However, Agri. Co-op X has already employed two Chinese on its staff and accumulated experience on how to socialize with Chinese farming laborers. Therefore, if Agri. Co-op X changes current sending organizations to those outside China, these resources become useless. Additionally, there is no guarantee Agri. Co-op X can find a partners outside China17.

A solution could be the revision of Japan’s immigration policy. For example, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations recommends the government to consider alternatives to resist the acceptance of unskilled foreign laborers, and officially opening the Japanese labor market to manpower in developing countries by establishing a formal framework for receiving unskilled laborers18.

Without Jisshusei, farms in City X will sustain a significant loss. The case of Agri. Co-op X illustrates the limits of today’s Gaikokujin Kenshusei system.

Footnotes

Date submitted: Jan. 16, 2017

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Jan. 16, 2017