ABSTRACT

This study attempted to explore the marketing and distribution situation in the supply chain of rice seed in lower Myanmar. The survey was conducted from September to October, 2015. The stratified random sampling method was used to select the seed growers, seed dealers and farmers. A total of 16 sample seed growers were personally interviewed in which 14 and two seed growers from Maubin and Daik U Township and four seed dealers from Maubin were also interviewed. The household level survey was carried out in four villages in Maubin and three villages in Daik U Township. A total of 120 sample farmers were collected in which 67 farmers from Maubin Township, Ayarwaddy Region and 53 farmers from Daik U Township, Bago Region used the purposive random sampling method. Based on the research findings, 71% of the seeds used from informal seed sources were the main seeds supply for Maubin and 80% for Daik U, followed by formal quality seeds. The ways of seed distribution were farmers to farmers, seed dealers and rice millers to farmers, distribution by DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed farms), DAR / DAR(Research farms) and IO to seed growers then farmers or directly.

INTRODUCTION

Rice (paddy) is by far the most important crop, taking up approximately eight million hectares and 40% of all food production in Myanmar (Baroang 2004). Rice is predominantly dominated by smallholders under rain-fed conditions. Historically, rice has been categorized under the staple food crop rather than commercial/cash crop. However, in recent years with the rapid growth of cities and towns propelled by rapid population growth, the country has experienced enormous increase in rice demand. Most of rice demanded and consumed by the urban population is sourced from the rural rice producing areas that have stagnating production capacities. Therefore, in order to be sustainable in production, rice seeds are considered the most important input among the many inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. And, the productivity by 15-20% which can be increased by using quality seeds alone (Behura, n.d 2015).

In 2013-2014, the formal system produced 197 tons of Registered Seed (RS) (MoAI 2014). If all RS were grown into 15,000 tons of Certified Seed (CS) by the Seed Model Villages, contact farmers and private companies, these CS could cover approximately 370,000 hectares of land at a seed rate of 40 kg/ha. According to this data, this certified seed distribution system covers less than 5% of the rice acreage of Myanmar (ADB 2013).

Problem Statements

Maubin Township is situated in Ayarwaddy Region which is the largest rice growing area with a latitude of 16˚ 30' north and east longitudes 95˚ 24'. The area of Maubin township was 133,540 hectares and the cultivated area was 86,538 hectares, which is 67.71% of the total area. The area of paddy land was about 57,348 hectares and dry land was about 33,747 hectares. Ever since, Maubin farmers were mostly dependent on admixture HYV; hence seed requirement was met through informal seeds. Therefore, the yield and productivity is decreased drastically by the use of admixture HYV coupled with unguaranteed quality seeds although the Seed Village scheme was established.

Daik U Township is located between latitude 87˚ 50' north and east longitudes 97˚ 48'. It includes the Bago Region, which is the second largest rice acreage. The area of Daik U Township was 90,236 hectares and the cultivated area was 80,820 hectares, 89.57 % of total area. The area of paddy land was about 77,984 hectares, and dry land, which is about 897 hectares. There are two seed farms under the Department of Agriculture (DoA) in Daik U. However, the farmers do not access the certified rice seeds in enough amounts. Consequently, there is the availability of fake seeds with the stockiest in the market. Therefore, this study takes on a task of analyzing the seed marketing and distribution situation in Myanmar’s supply chain especially in Maubin and Daik U Township.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

The study was conducted by following the sample survey method. Data were collected from individual farmers of two selected townships (Maubin and Daik U Township) from October to November 2015. Data were taken from a total of 120 respondents in which 67 farmers from Maubin and 53 farmers from Daik U gathered information. Purposive random sampling technique was followed in selecting the respondent farmers. Primary data from the respondents were collected through structured questionnaire following the interview method. After completion of data collection, tabulation work including editing, coding and tabulation were done manually. Collected data were compiled in the Microsoft Excel program. The analysis was employed with demographical approach and descriptive method like average, percentage, etc by Excel Software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic and Socio-economic information

Age of the respondents

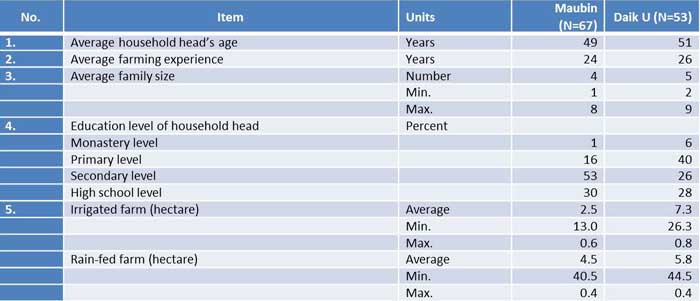

In agricultural work, young farmers carry out better compared to the older ones. Therefore, age is regarded as a very crucial factor. However, young farmers are more interested in adopting new technologies. In Maubin Township, the average age of farmer was 49 years. Respondents’ working experiences also play an important role in agricultural chain activities. Experiences in farming was 24 years and the average family member was 4.

In Daik U Township, the average age of farmer was 51 years and their experiences in farming was an average of 26 years. There were five family members in average.

Level of education

The level of education of the respondents was important for decision making of farming system and marketing practices. In this study, education level of the sample respondents was categorized into four groups: (1) "Monastery education" referred informal schooling although they could read and write; (2) "Primary level" referred formal schooling up to five years; (3) "Secondary level" intended formal schooling up to nine years, and (4) "High school level and above " referred the formal schooling up to 11 years and above (received degree from college or university). The education level of farmers was assumed to determine the decision making of their farming system.

In Maubin Township, 1%, 16%, 53% and 30% of farm households attained monastery, primary, secondary and high school and above education level, respectively. In this township, the secondary level was the highest number in the farm households.

In Daik U Township, 6%, 40%, 26% and 28% of farm households attained monastery, primary, secondary and high school and above education level, respectively. According to these data, the highest education level attained by the respondents was primary. Therefore, the respondents from Maubin Township had comparatively better education level than that of Daik U Township.

Farm size and different farm types of sample farm households

Land ownership or farm size is an important factor for adopting modern rice production technologies. In general, farmers owing large size farm apply diversified cropping system and adopt new technologies earlier. Hence, these farmers are assumed as earlier adopter.

In Maubin Township, the average irrigated farm size of sample respondents was 2.5 hectares ranging from 0.6 to 13.0 hectares. Rain-fed farm size was 4.5 hectares ranging from 0.4 to 40.5 hectares. In Daik U Township, 7.3 hectares and 5.8 hectares were the average farm size for irrigated and rain-fed area. The range for irrigated farm size was 0.8 to 26.3 hectares whereas rain-fed area was ranged from 0.4 to 44.5 hectares. Therefore, Daik U Township was more accessible to irrigation.

Varieties grown by sample farmers

There were different varieties cultivated by sample farmers in the study areas as shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. Among the varieties, Hnan Kar (46%), Sin Thu Kha (46%) and Thee Htat Yin (45%) varieties were grown by most of the farmers in Maubin. The other varieties such as Tawn Pyant, Sin Thwe Latt, Pyi Taw Yin, Paw Sann, Yay Anelo-4, Manaw Thukha, Yay Myoke Kan-2, Ayar Min, Vietnam, Pale Thwe and Yay Anelo-1 were also cultivated.

In Daik U, the major varieties planted by sample farmers were Hmawbi-2 (67%) and Sin Thu Kha (58%). Manaw Thukha, Sin Thwe Latt, Pyi Taw Yin, Yadanar Toe, Kyaw Zeya, Paw Sann Yin, Yar Kyaw, Kauk Hyinn, Vietnam and Pale Thwe varieties were also grown.

Table 1. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the sample respondents in the study areas

Fig. 1. Varieties grown by farmers in Maubin Township (N=67)

Fig. 2. Varieties grown by farmers in Daik U Township (N=53)

Sources of rice seeds for sample farmers

Among the rice seed sources, there were formal seed sources including DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed farm), International Organization (IO) and Department of Agricultural Research (DAR) and informal sources such as farmer themselves, other farmers, contact farmer/seed grower, rice miller and seed dealers (Table 2). In this table, 71% of the seeds used from informal seed sources was the major seed supply for Maubin and 80% for Daik U whereas 29% and 20% of formal sources were other seed supply in Maubin and Daik U, respectively. Therefore, the seed sector in both areas was dominant by informal seed system. Farmers were used to keep their rice seeds for next season and it was more profound in Daik U Township. The key strengths of this seed system are that the varieties are well adapted to the farmers’ production system, the quality is known by farmers, and the seeds are affordable due to the existence of local exchange and dissemination mechanisms (Broek et al. 2015).

Table 2. Classification of seed sources for the sample farmers in the study areas

Marketing Channels of Rice Quality Seed

Marketing channels are set of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use (Kolter 2001). A linkage from producer to other participants or to ultimate users is accomplished by marketing intermediaries. A channel to complete the gap between production and utilization in particular time, place, quantity and quality. Market intermediaries perform various functions in order to bridge these gaps. Seed marketing channels were observed for understanding the commodity flow from institutions or agents to market intermediaries and to final user farmers. Figure 3 shows the common rice quality seed marketing channels in the study areas. According to the market survey, most of the rice seeds came from farmers’ own seed stored from previous season of harvests. Most of the farmers usually replace the seeds at once in three years and is known as the seed renewal period. The renewal seed normally comes from seed growers, other (peers or fellows) farmers, contact farmers, seed dealers, DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed Farm) and DAR (Research farms).

Business size of the seed growers

In this study, 16 seed growers were interviewed to determine the rice seed production, marketing functions and marketing channels in the study areas. Business sizes of seed growers were distinguished according to the annual sale amounts of rice quality seeds (Table 3). In the rice seed market, Maubin and Daik U Township, seed growers were marketed as registered improved rice seeds except Yn-3155. Even though this variety, Yn-3155, was introduced by IRRI for trial, the farmers preferred to grow this variety because it is high yielding.

Based on the survey data, the amounts of total annual production by the sampled seed growers in Maubin and Daik U were 138.06 MT and 11.50 MT, respectively. The amounts of total annual sale were 138.06 MT in which all production of these varieties except Sin Thu Kha were sold as seeds in Maubin. About 60% of Sin Thu Kha was wholesaled as quality seeds and 40% as grains. In Daik U, only 63% of both Hmawbi-2 and Sin Thu Kha varieties was sold as good seeds and 37% as grain.

The results of the study revealed that the seed growers could not bring all produce to the market as good quality seeds due to the lack of advanced storage facilities and poor post harvest processing.

Table 3. Production and sale of rice seed growers in the study areas

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

.jpg)

Fig. 3. Marketing and distribution channels of rice quality seed in the study areas

Marketing activities of the seed growers of rice seed market in the study areas

Table 4 shows the marketing activities of seed growers of rice seed market. All seed growers grew and sold four varieties of rice seeds in Maubin and two varieties in Daik U. The main buyers were seed dealers (65%) and farmers (35%) in Maubin and farmers (100%) in Daik U. All seed growers in both townships sold by cash and by down payment transaction.

Mode of transportation system was especially by trailer in the study areas. The rice seeds were stored in 33% and 67% of bamboo granary and polyethylene bags at the silos or in their homes (by 21% of the seed growers in Maubin). All seed growers in Daik U stored the seeds in polyethylene bags at the silos or in their homes.

Regarding Table 3, although about 79% of seed growers in Maubin put up for sale the rice seed directly from threshing without labeling, guarantee and certification on polyethylene packages, all seed growers in the study areas sold the seeds without any trademark on their packaging. The farmers recognize the seeds by observing the fields, which contain a little off-type plants, uniformity and other aspects of plant characteristics. But the quality is reduced by post-harvest processing and was not done systematically.

Table 4. Marketing activities of the seed growers of rice seed market in the study areas

Business size of the seed dealers

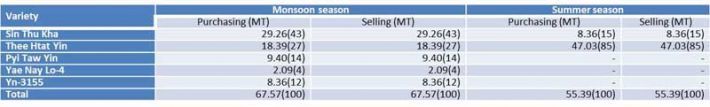

In this study, there were four seed dealers in only Maubin that were questioned to verify the rice seed marketing functions and marketing channels. Regarding the sale amounts of rice quality seeds per year, business sizes of seed dealers were recognized in Table 5.. In this table, seed dealers sold the rice seeds to farmers and private companies (Agro-chemical Company).

Based on the survey data, the seed dealers could sell all the seeds purchased in both seasons. The amounts of total marketed seeds were 67.57 MT in monsoon season and 55.39 MT in summer season.

The seed dealers sold Sin Thu Kha, Thee Htat Yin, Pyi Taw Yin, Yay Anelo-4 and Yn-3155 which were 43%, 27%, 14%, 4% and 12% in monsoon season and Sin Thu Kha (15%) and Thee Htat Yin (85%) in summer season. According to this result, Sin Thu Kha was the most marketed variety during the monsoon season and Thee Htat Yin variety during summer.

Table 5. Annual sale amount of rice quality seed by seed dealers in Maubin Township (N=4)

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

Marketing activities of the seed dealers of rice seed market in the study areas

As illustrated in Table 6, all seed dealers sold five varieties of rice seed in monsoon season and two varieties in summer. They bought the seeds from contact farmers (70%) and DAR (20%) and farmers (10%) in monsoon season and farmer (60%) and contact farmers (40%) in summer.

In monsoon season, 78% of the main buyers were farmers and 22% belonging to private companies. In summer 100% of the main buyers are farmers. In selling for monsoon season crop, about 75% of the down payment was paid through cash transaction. In summer, 50% each was paid through cash and credit payment transaction.

Mode of transportation system was mainly by trailer in the study areas. All rice seeds were stored in polyethylene bags at their homes.

Regarding the results, the seed dealers bought the largest portion of the seeds for monsoon season from contact farmers who used the quality seeds from the relevant formal institutions. The contact farmers were also key farmers for training, extension education and development programs. In summer season, most of the seeds marketed by seed dealers came from farmers. Similar to the seed growers, the seeds were sold without any trademarks on the packaging.

Table 6. Marketing activities of the seed dealers of rice seed market in Maubin Township (N=4)

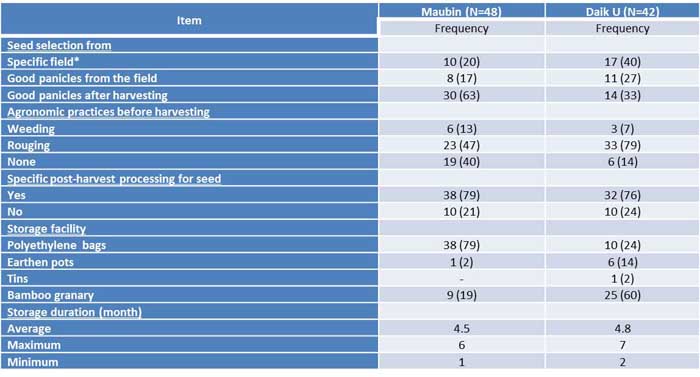

Farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas

Farmers owned seeds were the most mentioned among many sources as cited in Table 2 because of seed costs and availability. And on-farm seed production can solve the problems of ineffective seed distribution and poor seed availability by rural seed programs at the farmer and village levels. For those reasons, the practices of farmers to use the seeds for their next crop were the important role in crop production.

Table 7 explains the farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas. In seed selection, the farmers chose the seeds from specific fields (20%), good panicles from the fields (17%) and good panicles after harvesting (63%) in Maubin and from specific field (40%), good panicles from the fields (27%) and good panicles after harvesting (33%) in Daik U. Weeding was done by 13% of Maubin farmers and 7% of Daik U farmers and rouging by 47% and 79% of farmers in Maubin and Daik U, respectively. In Maubin and Daik U, 40% and 14% of farmers did not do any weeding and rouging. About 79% and 76% of farmers in Maubin and Daik U processed the post harvest activities specific for seeds. As storage facilities, the farmers used the polyethylene bags (79%), earthen pots (2%) and bamboo granary (19%) in Maubin Township and the polyethylene bags (24%), earthen pots (14%), tin (2%) and bamboo granary (60%) in Daik U. The average storage duration was 4.5 months ranging from 1 to 6 months in Maubin and 4.8 months ranging from 2 to 7 months in Daik U.

Table 7. Farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

*Specific field means the field which is indented to use for seed production.

Farmers’ perceptions to price, availability and satisfaction of formal rice seed use in the study areas

The results on Table 8 showed that about 60%, 66% and 57% of farmers respectively agreed with the notion that quality seeds are generally expensive, not readily available and give satisfaction for yield in Maubin Township while 43%, 57% and 53% of farmers in Daik U also agreed with these three facts. Although the farmers had an agreement on quality seeds that were expensive, they had a wiliness to buy. And the farmers were facing unavailability of quality seeds from formal sectors. The farmers accepted the fact that the production will be increased by quality seeds with favorable environment such as fair climate, low incidence of pests, etc.

Table 8. Farmers’ perceptions to price, availability and satisfaction of formal rice seed use in the study areas

CONCLUSION

In the marketing channels of rice quality seeds, there were three main market actors (seed growers, seed dealers and farmers) in Maubin and most of seed dealers were the extension workers. In Daik U Township, two main market actors (seed growers and farmers) involved in rice quality seed marketing channels according to the market survey. Regarding the result findings of the two areas, farmers were the most important participants because farmers used the rice seeds from their own seeds from previous harvests and bought the seeds from the other farmers.

There were two main high yielding varieties in each township. They were Sin Thu Kha, Thee Htat Yin in Maubin and Hmawbi-2 and Sin Thu Kha in Daik U. The rice quality seed was distributed through various channels including government, IO, local markets and farmers own production. Quality seeds were distributed from DAR/ DAR (Research farms) to DoA (Seed farms) then to DoA (Township office) to seed growers/contact farmers to seed dealers/other farmers to selected farmers or directly from DAR/DAR (Research farms), DoA (Township office) and seed growers for HYV in Maubin. The quality seed is also distributed from DAR/ DAR (Research farms) to DoA (seed farms) to seed growers and/or other farmers to selected farmers or directly from seed farms and seed growers for HYV in Daik U. Farmers and seed growers usually prefer the channel that was obtaining their seeds directly through government agencies. However, informal seed sources (71% for Maubin and 80% for Daik U) were the major sources providing opportunities to improve farmers’ access to good seeds, adapted to local requirements but there exists no appropriate system. The quality of seeds is questionable. Which cause a limiting factor in production.

In the marketing activities of the seed growers, they grew and sold the rice quality seeds on cash down payment system in both Maubin and Daik U Township. However, they could not sell the entire seeds because of lack of advanced storage facilities and poor post harvest facilities. For seed dealers in Maubin, they practiced buying and selling with both cash down and credit system. Their main transportation vehicle was trailer. In both townships, all seeds were sold by market participants without labeling: guarantee and any trademarks on packaging. Most of the farmers in Maubin selected the seeds for next crop from good panicles after harvesting and in Daik U, the farmers used the seeds from specific field. The majority of farmers in both study areas did rouging and the other varieties but did not perform weeding. All farmers processed post harvest activities specific for seeds. The seeds were stored in polyethylene bags by farmers in Maubin and in bamboo granary by farmers in Daik U.

POLICY IMPLICATION

Lack of entrepreneurship skills by the market participants was one of the main causes of low production and productivity of rice. Therefore, seed marketing skills should be enhanced by developing institutional base for seasonal forecast of quality seed demand and supply and training seed entrepreneurs and support local institutions to plan and market quality seeds.

Informal seed flows have been left out of government or donor efforts geared to improve the seed sector in the region. Strengthening these important seed flows could make a substantial contribution to the overall development of the seed sector. Government should recognize the informal seed sector and be committed to strengthening its capabilities.

In terms of quality seed distribution and marketing channels, farmers were the major participants. Although majority of the farmers select seeds from the portion of the field with good crop stand, and practice rouging and floatation, the quality of the rice seeds that farmers saved from the harvest for use in the next season is not of high standard. Thus, community based seed production should be encouraged by extension personnel to be well functioning in informal seed system. If the conducive policy environment is established, farmers can be more effective in playing their role as managers of agricultural biodiversity.

Most of farmers use the seeds from the informal seed sources (farmer own seeds). The quality of farmers own seeds can improve through reduced rates of re-use of this seeds, which can be achieved by improving farmers’ access to the varieties of their choice, for reasonable prices. Hence, focus should be on demand based on decentralized source of seed production and supply of choice varieties with greater involvement of private sector’s capacity to reduce mis-match in demand and supply and enhance efficiency in production and supply of quality seeds.

There was a lack of licensing of seed sellers, inspection of retailers to check adulteration. Therefore, there is an urgent need to strengthen the National Seed Committee (NSC) that is the body responsible for seed quality assurance and the supply of seeds and planting materials to farmers.

There is a need to strengthen the capacity of both seed growers by training on quality seed production and postharvest management as well as regulatory officers to implement improved seed inspection and certification.

Training on improved practices on rice production, packaging, transportation, storing and marketing of seeds is very important in improving knowledge and skills of the rice seed market actors. Therefore, linkages and synergy with stakeholders in seed production, marketing and consumption must be established. This could be achieved by creating linkages and capacity building of farmers in training centers, contact with DoA, and traders and cooperatives.

Coordination and linkages among all actors and stockholders is needed to strengthen and foster rapid, orderly and effective growth to get strong coordination and linkages among actors in the system for seed development, production, multiplication and distribution so that the seed sector can meet farmers’ needs in terms of timing of seed supply.

REFERENCES

ADB. 2013. Developing a competitive seed industry in Myanmar, CLMV Project Policy Brief No.1, ADB Institute.

Baroang, K. 2014. Background Paper No. 1 Myanmar Bio-Physical Characterization: Summary Findings and Issues to Explore, Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development, Earth Institute at Columbia University.

Behura, n.d. Production and marketing of rice seed and institutional constraints for quality seed distribution in Odisha. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

Broek, J.V.D., F. Jongeleen, A. Subedi, and N. L. Oo 2015. Pathways for Developing the Seed Sector of Myanmar: A Scoping Study. Center for Development Innovation. Wageningen.

Kotler, P. 2001. Marketing Management, Millennium edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MoAI). 2014. Activities of Department of Agriculture, Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

|

Date submitted: Nov. 15, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Nov. 16, 2016

|

Rice Seed Marketing and Distribution Situation along Supply Chains of Lower Myanmar

ABSTRACT

This study attempted to explore the marketing and distribution situation in the supply chain of rice seed in lower Myanmar. The survey was conducted from September to October, 2015. The stratified random sampling method was used to select the seed growers, seed dealers and farmers. A total of 16 sample seed growers were personally interviewed in which 14 and two seed growers from Maubin and Daik U Township and four seed dealers from Maubin were also interviewed. The household level survey was carried out in four villages in Maubin and three villages in Daik U Township. A total of 120 sample farmers were collected in which 67 farmers from Maubin Township, Ayarwaddy Region and 53 farmers from Daik U Township, Bago Region used the purposive random sampling method. Based on the research findings, 71% of the seeds used from informal seed sources were the main seeds supply for Maubin and 80% for Daik U, followed by formal quality seeds. The ways of seed distribution were farmers to farmers, seed dealers and rice millers to farmers, distribution by DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed farms), DAR / DAR(Research farms) and IO to seed growers then farmers or directly.

INTRODUCTION

Rice (paddy) is by far the most important crop, taking up approximately eight million hectares and 40% of all food production in Myanmar (Baroang 2004). Rice is predominantly dominated by smallholders under rain-fed conditions. Historically, rice has been categorized under the staple food crop rather than commercial/cash crop. However, in recent years with the rapid growth of cities and towns propelled by rapid population growth, the country has experienced enormous increase in rice demand. Most of rice demanded and consumed by the urban population is sourced from the rural rice producing areas that have stagnating production capacities. Therefore, in order to be sustainable in production, rice seeds are considered the most important input among the many inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. And, the productivity by 15-20% which can be increased by using quality seeds alone (Behura, n.d 2015).

In 2013-2014, the formal system produced 197 tons of Registered Seed (RS) (MoAI 2014). If all RS were grown into 15,000 tons of Certified Seed (CS) by the Seed Model Villages, contact farmers and private companies, these CS could cover approximately 370,000 hectares of land at a seed rate of 40 kg/ha. According to this data, this certified seed distribution system covers less than 5% of the rice acreage of Myanmar (ADB 2013).

Problem Statements

Maubin Township is situated in Ayarwaddy Region which is the largest rice growing area with a latitude of 16˚ 30' north and east longitudes 95˚ 24'. The area of Maubin township was 133,540 hectares and the cultivated area was 86,538 hectares, which is 67.71% of the total area. The area of paddy land was about 57,348 hectares and dry land was about 33,747 hectares. Ever since, Maubin farmers were mostly dependent on admixture HYV; hence seed requirement was met through informal seeds. Therefore, the yield and productivity is decreased drastically by the use of admixture HYV coupled with unguaranteed quality seeds although the Seed Village scheme was established.

Daik U Township is located between latitude 87˚ 50' north and east longitudes 97˚ 48'. It includes the Bago Region, which is the second largest rice acreage. The area of Daik U Township was 90,236 hectares and the cultivated area was 80,820 hectares, 89.57 % of total area. The area of paddy land was about 77,984 hectares, and dry land, which is about 897 hectares. There are two seed farms under the Department of Agriculture (DoA) in Daik U. However, the farmers do not access the certified rice seeds in enough amounts. Consequently, there is the availability of fake seeds with the stockiest in the market. Therefore, this study takes on a task of analyzing the seed marketing and distribution situation in Myanmar’s supply chain especially in Maubin and Daik U Township.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

The study was conducted by following the sample survey method. Data were collected from individual farmers of two selected townships (Maubin and Daik U Township) from October to November 2015. Data were taken from a total of 120 respondents in which 67 farmers from Maubin and 53 farmers from Daik U gathered information. Purposive random sampling technique was followed in selecting the respondent farmers. Primary data from the respondents were collected through structured questionnaire following the interview method. After completion of data collection, tabulation work including editing, coding and tabulation were done manually. Collected data were compiled in the Microsoft Excel program. The analysis was employed with demographical approach and descriptive method like average, percentage, etc by Excel Software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Demographic and Socio-economic information

Age of the respondents

In agricultural work, young farmers carry out better compared to the older ones. Therefore, age is regarded as a very crucial factor. However, young farmers are more interested in adopting new technologies. In Maubin Township, the average age of farmer was 49 years. Respondents’ working experiences also play an important role in agricultural chain activities. Experiences in farming was 24 years and the average family member was 4.

In Daik U Township, the average age of farmer was 51 years and their experiences in farming was an average of 26 years. There were five family members in average.

Level of education

The level of education of the respondents was important for decision making of farming system and marketing practices. In this study, education level of the sample respondents was categorized into four groups: (1) "Monastery education" referred informal schooling although they could read and write; (2) "Primary level" referred formal schooling up to five years; (3) "Secondary level" intended formal schooling up to nine years, and (4) "High school level and above " referred the formal schooling up to 11 years and above (received degree from college or university). The education level of farmers was assumed to determine the decision making of their farming system.

In Maubin Township, 1%, 16%, 53% and 30% of farm households attained monastery, primary, secondary and high school and above education level, respectively. In this township, the secondary level was the highest number in the farm households.

In Daik U Township, 6%, 40%, 26% and 28% of farm households attained monastery, primary, secondary and high school and above education level, respectively. According to these data, the highest education level attained by the respondents was primary. Therefore, the respondents from Maubin Township had comparatively better education level than that of Daik U Township.

Farm size and different farm types of sample farm households

Land ownership or farm size is an important factor for adopting modern rice production technologies. In general, farmers owing large size farm apply diversified cropping system and adopt new technologies earlier. Hence, these farmers are assumed as earlier adopter.

In Maubin Township, the average irrigated farm size of sample respondents was 2.5 hectares ranging from 0.6 to 13.0 hectares. Rain-fed farm size was 4.5 hectares ranging from 0.4 to 40.5 hectares. In Daik U Township, 7.3 hectares and 5.8 hectares were the average farm size for irrigated and rain-fed area. The range for irrigated farm size was 0.8 to 26.3 hectares whereas rain-fed area was ranged from 0.4 to 44.5 hectares. Therefore, Daik U Township was more accessible to irrigation.

Varieties grown by sample farmers

There were different varieties cultivated by sample farmers in the study areas as shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. Among the varieties, Hnan Kar (46%), Sin Thu Kha (46%) and Thee Htat Yin (45%) varieties were grown by most of the farmers in Maubin. The other varieties such as Tawn Pyant, Sin Thwe Latt, Pyi Taw Yin, Paw Sann, Yay Anelo-4, Manaw Thukha, Yay Myoke Kan-2, Ayar Min, Vietnam, Pale Thwe and Yay Anelo-1 were also cultivated.

In Daik U, the major varieties planted by sample farmers were Hmawbi-2 (67%) and Sin Thu Kha (58%). Manaw Thukha, Sin Thwe Latt, Pyi Taw Yin, Yadanar Toe, Kyaw Zeya, Paw Sann Yin, Yar Kyaw, Kauk Hyinn, Vietnam and Pale Thwe varieties were also grown.

Table 1. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the sample respondents in the study areas

Fig. 1. Varieties grown by farmers in Maubin Township (N=67)

Fig. 2. Varieties grown by farmers in Daik U Township (N=53)

Sources of rice seeds for sample farmers

Among the rice seed sources, there were formal seed sources including DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed farm), International Organization (IO) and Department of Agricultural Research (DAR) and informal sources such as farmer themselves, other farmers, contact farmer/seed grower, rice miller and seed dealers (Table 2). In this table, 71% of the seeds used from informal seed sources was the major seed supply for Maubin and 80% for Daik U whereas 29% and 20% of formal sources were other seed supply in Maubin and Daik U, respectively. Therefore, the seed sector in both areas was dominant by informal seed system. Farmers were used to keep their rice seeds for next season and it was more profound in Daik U Township. The key strengths of this seed system are that the varieties are well adapted to the farmers’ production system, the quality is known by farmers, and the seeds are affordable due to the existence of local exchange and dissemination mechanisms (Broek et al. 2015).

Table 2. Classification of seed sources for the sample farmers in the study areas

Marketing Channels of Rice Quality Seed

Marketing channels are set of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use (Kolter 2001). A linkage from producer to other participants or to ultimate users is accomplished by marketing intermediaries. A channel to complete the gap between production and utilization in particular time, place, quantity and quality. Market intermediaries perform various functions in order to bridge these gaps. Seed marketing channels were observed for understanding the commodity flow from institutions or agents to market intermediaries and to final user farmers. Figure 3 shows the common rice quality seed marketing channels in the study areas. According to the market survey, most of the rice seeds came from farmers’ own seed stored from previous season of harvests. Most of the farmers usually replace the seeds at once in three years and is known as the seed renewal period. The renewal seed normally comes from seed growers, other (peers or fellows) farmers, contact farmers, seed dealers, DoA (Township office), DoA (Seed Farm) and DAR (Research farms).

Business size of the seed growers

In this study, 16 seed growers were interviewed to determine the rice seed production, marketing functions and marketing channels in the study areas. Business sizes of seed growers were distinguished according to the annual sale amounts of rice quality seeds (Table 3). In the rice seed market, Maubin and Daik U Township, seed growers were marketed as registered improved rice seeds except Yn-3155. Even though this variety, Yn-3155, was introduced by IRRI for trial, the farmers preferred to grow this variety because it is high yielding.

Based on the survey data, the amounts of total annual production by the sampled seed growers in Maubin and Daik U were 138.06 MT and 11.50 MT, respectively. The amounts of total annual sale were 138.06 MT in which all production of these varieties except Sin Thu Kha were sold as seeds in Maubin. About 60% of Sin Thu Kha was wholesaled as quality seeds and 40% as grains. In Daik U, only 63% of both Hmawbi-2 and Sin Thu Kha varieties was sold as good seeds and 37% as grain.

The results of the study revealed that the seed growers could not bring all produce to the market as good quality seeds due to the lack of advanced storage facilities and poor post harvest processing.

Table 3. Production and sale of rice seed growers in the study areas

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

Fig. 3. Marketing and distribution channels of rice quality seed in the study areas

Marketing activities of the seed growers of rice seed market in the study areas

Table 4 shows the marketing activities of seed growers of rice seed market. All seed growers grew and sold four varieties of rice seeds in Maubin and two varieties in Daik U. The main buyers were seed dealers (65%) and farmers (35%) in Maubin and farmers (100%) in Daik U. All seed growers in both townships sold by cash and by down payment transaction.

Mode of transportation system was especially by trailer in the study areas. The rice seeds were stored in 33% and 67% of bamboo granary and polyethylene bags at the silos or in their homes (by 21% of the seed growers in Maubin). All seed growers in Daik U stored the seeds in polyethylene bags at the silos or in their homes.

Regarding Table 3, although about 79% of seed growers in Maubin put up for sale the rice seed directly from threshing without labeling, guarantee and certification on polyethylene packages, all seed growers in the study areas sold the seeds without any trademark on their packaging. The farmers recognize the seeds by observing the fields, which contain a little off-type plants, uniformity and other aspects of plant characteristics. But the quality is reduced by post-harvest processing and was not done systematically.

Table 4. Marketing activities of the seed growers of rice seed market in the study areas

Business size of the seed dealers

In this study, there were four seed dealers in only Maubin that were questioned to verify the rice seed marketing functions and marketing channels. Regarding the sale amounts of rice quality seeds per year, business sizes of seed dealers were recognized in Table 5.. In this table, seed dealers sold the rice seeds to farmers and private companies (Agro-chemical Company).

Based on the survey data, the seed dealers could sell all the seeds purchased in both seasons. The amounts of total marketed seeds were 67.57 MT in monsoon season and 55.39 MT in summer season.

The seed dealers sold Sin Thu Kha, Thee Htat Yin, Pyi Taw Yin, Yay Anelo-4 and Yn-3155 which were 43%, 27%, 14%, 4% and 12% in monsoon season and Sin Thu Kha (15%) and Thee Htat Yin (85%) in summer season. According to this result, Sin Thu Kha was the most marketed variety during the monsoon season and Thee Htat Yin variety during summer.

Table 5. Annual sale amount of rice quality seed by seed dealers in Maubin Township (N=4)

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

Marketing activities of the seed dealers of rice seed market in the study areas

As illustrated in Table 6, all seed dealers sold five varieties of rice seed in monsoon season and two varieties in summer. They bought the seeds from contact farmers (70%) and DAR (20%) and farmers (10%) in monsoon season and farmer (60%) and contact farmers (40%) in summer.

In monsoon season, 78% of the main buyers were farmers and 22% belonging to private companies. In summer 100% of the main buyers are farmers. In selling for monsoon season crop, about 75% of the down payment was paid through cash transaction. In summer, 50% each was paid through cash and credit payment transaction.

Mode of transportation system was mainly by trailer in the study areas. All rice seeds were stored in polyethylene bags at their homes.

Regarding the results, the seed dealers bought the largest portion of the seeds for monsoon season from contact farmers who used the quality seeds from the relevant formal institutions. The contact farmers were also key farmers for training, extension education and development programs. In summer season, most of the seeds marketed by seed dealers came from farmers. Similar to the seed growers, the seeds were sold without any trademarks on the packaging.

Table 6. Marketing activities of the seed dealers of rice seed market in Maubin Township (N=4)

Farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas

Farmers owned seeds were the most mentioned among many sources as cited in Table 2 because of seed costs and availability. And on-farm seed production can solve the problems of ineffective seed distribution and poor seed availability by rural seed programs at the farmer and village levels. For those reasons, the practices of farmers to use the seeds for their next crop were the important role in crop production.

Table 7 explains the farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas. In seed selection, the farmers chose the seeds from specific fields (20%), good panicles from the fields (17%) and good panicles after harvesting (63%) in Maubin and from specific field (40%), good panicles from the fields (27%) and good panicles after harvesting (33%) in Daik U. Weeding was done by 13% of Maubin farmers and 7% of Daik U farmers and rouging by 47% and 79% of farmers in Maubin and Daik U, respectively. In Maubin and Daik U, 40% and 14% of farmers did not do any weeding and rouging. About 79% and 76% of farmers in Maubin and Daik U processed the post harvest activities specific for seeds. As storage facilities, the farmers used the polyethylene bags (79%), earthen pots (2%) and bamboo granary (19%) in Maubin Township and the polyethylene bags (24%), earthen pots (14%), tin (2%) and bamboo granary (60%) in Daik U. The average storage duration was 4.5 months ranging from 1 to 6 months in Maubin and 4.8 months ranging from 2 to 7 months in Daik U.

Table 7. Farmers’ practices for own seed production in the study areas

Note: Figures in the parentheses represent percentage.

*Specific field means the field which is indented to use for seed production.

Farmers’ perceptions to price, availability and satisfaction of formal rice seed use in the study areas

The results on Table 8 showed that about 60%, 66% and 57% of farmers respectively agreed with the notion that quality seeds are generally expensive, not readily available and give satisfaction for yield in Maubin Township while 43%, 57% and 53% of farmers in Daik U also agreed with these three facts. Although the farmers had an agreement on quality seeds that were expensive, they had a wiliness to buy. And the farmers were facing unavailability of quality seeds from formal sectors. The farmers accepted the fact that the production will be increased by quality seeds with favorable environment such as fair climate, low incidence of pests, etc.

Table 8. Farmers’ perceptions to price, availability and satisfaction of formal rice seed use in the study areas

CONCLUSION

In the marketing channels of rice quality seeds, there were three main market actors (seed growers, seed dealers and farmers) in Maubin and most of seed dealers were the extension workers. In Daik U Township, two main market actors (seed growers and farmers) involved in rice quality seed marketing channels according to the market survey. Regarding the result findings of the two areas, farmers were the most important participants because farmers used the rice seeds from their own seeds from previous harvests and bought the seeds from the other farmers.

There were two main high yielding varieties in each township. They were Sin Thu Kha, Thee Htat Yin in Maubin and Hmawbi-2 and Sin Thu Kha in Daik U. The rice quality seed was distributed through various channels including government, IO, local markets and farmers own production. Quality seeds were distributed from DAR/ DAR (Research farms) to DoA (Seed farms) then to DoA (Township office) to seed growers/contact farmers to seed dealers/other farmers to selected farmers or directly from DAR/DAR (Research farms), DoA (Township office) and seed growers for HYV in Maubin. The quality seed is also distributed from DAR/ DAR (Research farms) to DoA (seed farms) to seed growers and/or other farmers to selected farmers or directly from seed farms and seed growers for HYV in Daik U. Farmers and seed growers usually prefer the channel that was obtaining their seeds directly through government agencies. However, informal seed sources (71% for Maubin and 80% for Daik U) were the major sources providing opportunities to improve farmers’ access to good seeds, adapted to local requirements but there exists no appropriate system. The quality of seeds is questionable. Which cause a limiting factor in production.

In the marketing activities of the seed growers, they grew and sold the rice quality seeds on cash down payment system in both Maubin and Daik U Township. However, they could not sell the entire seeds because of lack of advanced storage facilities and poor post harvest facilities. For seed dealers in Maubin, they practiced buying and selling with both cash down and credit system. Their main transportation vehicle was trailer. In both townships, all seeds were sold by market participants without labeling: guarantee and any trademarks on packaging. Most of the farmers in Maubin selected the seeds for next crop from good panicles after harvesting and in Daik U, the farmers used the seeds from specific field. The majority of farmers in both study areas did rouging and the other varieties but did not perform weeding. All farmers processed post harvest activities specific for seeds. The seeds were stored in polyethylene bags by farmers in Maubin and in bamboo granary by farmers in Daik U.

POLICY IMPLICATION

Lack of entrepreneurship skills by the market participants was one of the main causes of low production and productivity of rice. Therefore, seed marketing skills should be enhanced by developing institutional base for seasonal forecast of quality seed demand and supply and training seed entrepreneurs and support local institutions to plan and market quality seeds.

Informal seed flows have been left out of government or donor efforts geared to improve the seed sector in the region. Strengthening these important seed flows could make a substantial contribution to the overall development of the seed sector. Government should recognize the informal seed sector and be committed to strengthening its capabilities.

In terms of quality seed distribution and marketing channels, farmers were the major participants. Although majority of the farmers select seeds from the portion of the field with good crop stand, and practice rouging and floatation, the quality of the rice seeds that farmers saved from the harvest for use in the next season is not of high standard. Thus, community based seed production should be encouraged by extension personnel to be well functioning in informal seed system. If the conducive policy environment is established, farmers can be more effective in playing their role as managers of agricultural biodiversity.

Most of farmers use the seeds from the informal seed sources (farmer own seeds). The quality of farmers own seeds can improve through reduced rates of re-use of this seeds, which can be achieved by improving farmers’ access to the varieties of their choice, for reasonable prices. Hence, focus should be on demand based on decentralized source of seed production and supply of choice varieties with greater involvement of private sector’s capacity to reduce mis-match in demand and supply and enhance efficiency in production and supply of quality seeds.

There was a lack of licensing of seed sellers, inspection of retailers to check adulteration. Therefore, there is an urgent need to strengthen the National Seed Committee (NSC) that is the body responsible for seed quality assurance and the supply of seeds and planting materials to farmers.

There is a need to strengthen the capacity of both seed growers by training on quality seed production and postharvest management as well as regulatory officers to implement improved seed inspection and certification.

Training on improved practices on rice production, packaging, transportation, storing and marketing of seeds is very important in improving knowledge and skills of the rice seed market actors. Therefore, linkages and synergy with stakeholders in seed production, marketing and consumption must be established. This could be achieved by creating linkages and capacity building of farmers in training centers, contact with DoA, and traders and cooperatives.

Coordination and linkages among all actors and stockholders is needed to strengthen and foster rapid, orderly and effective growth to get strong coordination and linkages among actors in the system for seed development, production, multiplication and distribution so that the seed sector can meet farmers’ needs in terms of timing of seed supply.

REFERENCES

ADB. 2013. Developing a competitive seed industry in Myanmar, CLMV Project Policy Brief No.1, ADB Institute.

Baroang, K. 2014. Background Paper No. 1 Myanmar Bio-Physical Characterization: Summary Findings and Issues to Explore, Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development, Earth Institute at Columbia University.

Behura, n.d. Production and marketing of rice seed and institutional constraints for quality seed distribution in Odisha. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

Broek, J.V.D., F. Jongeleen, A. Subedi, and N. L. Oo 2015. Pathways for Developing the Seed Sector of Myanmar: A Scoping Study. Center for Development Innovation. Wageningen.

Kotler, P. 2001. Marketing Management, Millennium edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MoAI). 2014. Activities of Department of Agriculture, Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Date submitted: Nov. 15, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: Nov. 16, 2016