ABSTRACT

As Malaysia grapples with the dual challenges of urbanization and food insecurity, community gardens (CGs) are emerging as innovative responses to sustainable food production and community empowerment. This review paper explores the development, challenges, and transformative potential of CGs in the Klang Valley through a social enterprise lens. The paper highlights global best practices, introduces a social cooperative enterprise intervention model, and provides policy and practical recommendations for scaling CGs nationwide. Through collaborative governance, innovative farming, and inclusive participation, CGs can play a pivotal role in Malaysia’s sustainable urban development strategy.

Keywords: Community gardens, impact, social enterprise model, Klang Valley

INTRODUCTION

The intersection of urbanization and food security presents one of the most pressing challenges in the modern era. With rapid urban growth in regions such as the Klang Valley, Malaysia, the demand for locally sourced, affordable, and nutritious food has never been more urgent. Community gardens (CGs) are small-scale, community-driven agricultural initiatives located within urban environments and are increasingly recognized as practical solutions to address these challenges.

Community gardens in Malaysia is not a new concept and have gained renewed relevance under the Malaysia MADANI framework and the National Food Security Policy (2021–2025). These initiatives are supported by agencies such as the Department of Agriculture (DOA) and the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI). They serve multiple functions: enhancing household food security, reducing urban living costs, promoting healthy lifestyles, and fostering community cohesion.

Despite these benefits, the expansion and sustainability of CGs face numerous hurdles. These include limited access to land, inadequate funding, climate variability, low public awareness, and lack of technical knowledge among urban farmers (Ishak et al., 2022). Therefore, innovative frameworks are required to support these gardens not just as subsistence efforts, but as viable, community-driven enterprises.

This paper examines the potential of CGs in the Klang Valley to evolve into social enterprise models that blend economic goals with social missions. By drawing parallels with global practices in countries such as Singapore, Thailand, the USA, and Taiwan, the paper proposes strategies for integrating social entrepreneurship into Malaysia’s urban agriculture ecosystem.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON COMMUNITY GARDENS

Globally, CGs have become integral components of sustainable urban planning. In Singapore, where land scarcity is acute, the government promotes rooftop gardens to reduce reliance on food imports. These initiatives align with the city-state’s food resilience strategy and are embedded in housing and development policies (Mohd Hussain et al., 2020).

In Japan, particularly in Tokyo, regulations mandate green rooftops as part of building codes. These spaces not only serve environmental purposes but also function as productive agricultural zones, aligning with Japan’s vision of “urban forests.” Such policies are rooted in the cultural ethos of sustainability and collective responsibility.

The United States, especially cities like New York and Chicago, has institutionalized urban farming. The Brooklyn Grange in New York City stands as a commercial model of large-scale rooftop farming. By engaging diverse stakeholders—owners, volunteers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) —this initiative demonstrates the economic viability of urban agriculture alongside environmental and social benefits (Mohd Hussain et al., 2020).

Thailand’s Bangkok City Farm Program provides another compelling model. By transforming rooftops into farming hubs and promoting composting from household waste, Bangkok supports the urban poor in cultivating their food. Moreover, it promotes social capital through community-based training, knowledge sharing, and alternative markets (Boossabong, 2018).

Similarly, Taiwan’s Taipei Garden City Program and the Farming Urbanism Network (FUN) exemplify institutional collaboration in urban agriculture. Through partnerships with universities, NGOs, and municipalities, Taipei has created over 800 urban gardens, many of which are run by community groups that influence local food policy (Mabon, Shih & Jou, 2023). These international examples demonstrate that CGs, when supported by policy, community engagement, and sustainable design, can evolve into impactful enterprises.

COMMUNITY GARDENS IN KLANG VALLEY: OVERVIEW AND CHALLENGES

In Malaysia, the Klang Valley encompasses the nation's most urbanized and densely populated region. As urban sprawl increases, food accessibility becomes strained, particularly for low-income communities. According to the Global Hunger Index (2023), Malaysia's score has fallen from 17.3 in 2015 to 12.7 in 2023, placing it in the moderate category for hunger severity, signaling systemic issues in food distribution and affordability.

A survey identified 34 community gardens operating in the Klang Valley, ranging from small hobby farms to structured community projects (Ahmad et al., 2022). These gardens primarily grow vegetables such as chili, lettuce, spinach, and eggplant, often using organic or semi-organic methods. However, their scale, productivity, and sustainability vary considerably.

CGs in the Klang Valley face several structural and operational challenges that hinder their long-term sustainability and impact. One of the most pressing issues involves land tenure and legal constraints. Many CGs are established on plots of land that are temporarily granted or even illegally occupied, often without formal documentation or agreements. This legal ambiguity not only discourages investment in infrastructure and innovation but also leaves CGs vulnerable to eviction or redevelopment.

Financial sustainability is another significant concern. Most CGs rely on inconsistent government grants, ad-hoc donations, or internal member contributions. Limited access to credit and the absence of structured revenue models make it difficult for these gardens to scale their operations or adopt modern technologies that could enhance productivity and efficiency (Ishak et al., 2022).

Moreover, there is a notable deficiency in technical expertise and labor. Urban farmers often lack formal agricultural training, relying instead on trial-and-error approaches or informal knowledge sharing. The core workforce typically consists of retirees or volunteers, which raises concerns about long-term viability, physical capacity, and knowledge continuity.

Environmental factors further exacerbate these challenges. Unpredictable rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and extreme heat —likely amplified by climate change —complicate crop planning, irrigation management, and overall garden resilience (Hussain et al., 2019). These conditions increase the risk of crop failure, especially in gardens without proper shelter, drainage, or water-harvesting systems.

Lastly, limited youth involvement threatens the generational sustainability of CGs. Young people are often disengaged due to time constraints, lack of incentives, or the perception that urban farming lacks innovation or income potential. Without targeted outreach and opportunities for youth participation, CGs risk stagnation and leadership vacuums soon. Despite these challenges, they also present strategic entry points for policy and innovation. By adopting hybrid economic models such as social enterprises, CGs can access new funding streams, formalize their operations, and enhance their appeal to younger demographics and institutional partners.

READINESS TO ADOPT SOCIAL ENTERPRISE FRAMEWORK IN SELECTED COMMUNITY GARDENS

Overview of the selected community gardens

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of five selected CGs located in the Klang Valley, highlighting their key characteristics, challenges, and potential for transitioning into social enterprises. The table includes details such as the year of establishment, land size, farming approach, and main crops cultivated. It also outlines notable innovations implemented at each site, ranging from rainwater harvesting systems to aquaponics and solar-powered monitoring tools. Additionally, the table summarizes the specific operational challenges faced by each garden, including community involvement, aging membership, limited funding, and land-use constraints.

Table 1. Overview of the selected community gardens in the Klang Valley.

|

CG

|

Location & Year of establish-ment

|

Land size

|

Farming type

|

Key crops

|

Innovations

|

Challenges

|

|

A

|

Sepang, 2013

|

300 m²

|

Semi-organic

|

Eggplant, cabbage, chili

|

Self-watering containers, rainwater harvesting, and fertigation

|

Minimal community involvement, financial loss, pest threats, and inconsistent sponsorship

|

|

B

|

Subang Jaya, 2019

|

45 m²

|

Semi-organic

|

Leafy greens

|

Limited vertical gardening, fertigation

|

Space constraints, aging members, stagnant income, limited support

|

|

C

|

Kajang,

2005

|

8,094 m²

|

Organic + Aquaponics

|

Leafy greens, herbs, edible flowers, fish

|

Greenhouse, composting, companion planting, banana circle

|

Volunteer shortage, no formal technology training, underutilized land

|

|

D

|

TTDI, 2017

|

1,393 m²

|

Fully organic

|

Root vegetables, herbs, fruit

|

Solar monitoring, composting, wood chippers, permaculture

|

Local bureaucracy, rigid regulatory flexibility

|

|

E

|

Klang, 2018

|

1,011 m²

|

Semi-organic + Experimental rice

|

Vegetables, fruits, rice

|

Fertigation, barrel planters, Styrofoam rice boxes

|

Low monetization, despite strong agency support

|

CGs in Klang Valley contribute directly to the socio-economic well-being of their members and surrounding communities. Their impact can be categorized into internal benefits (experienced by CG members) and external benefits (affecting the broader community).

Internal impacts

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley have demonstrated notable internal impacts on the well-being, food security, and social cohesion of their members. One of the most frequently cited benefits is improved mental and physical health, particularly among older participants. As reported by Othman et al. (2018), involvement in gardening activities fosters a sense of purpose and therapeutic value, making these green spaces especially beneficial for retirees, the elderly, and individuals managing chronic illnesses. In addition to health outcomes, CGs have also contributed to tangible economic savings.

According to a report by MARDI, the primary goal of urban farming practices is to encourage residents, particularly those residing in high-rise buildings, to cultivate food crops for their daily consumption. This approach is expected to lower the cost of food production by minimising expenses. The Community Garden (CG) program was also designed to foster public participation and improve food supply for low-income populations, thereby helping to reduce household spending. It provided clear evidence of the program's financial impact which reported that the average monthly food expenses for participants before enrolling in the CG program were RM133.18 (US$31.33). Analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in these expenses, which fell to an average of RM78.76 (US$18.53) per month (Figure 1). The study further indicated that CG leaders in urban areas experienced a more substantial reduction in household expenditure than their counterparts in rural regions (Figure 2).

|

Before joining

|

After joining

|

|

RM133.18 (US$31.33)

|

RM78.76 (US$18.53)

|

Figure 1. Monthly household food expenditure

|

Urban

|

Rural

|

|

RM71.75 (US$16.88)

|

RM43.44 (US$10.22)

|

Figure 2. Average monthly reduction of food expenditure

Beyond economic and health benefits, CGs play a significant role in informal skills development. Members frequently gain hands-on experience in areas such as organic farming, composting, irrigation systems, and seed propagation. These competencies, while often self-taught or peer-shared, hold potential for commercialization and entrepreneurship. Additionally, the gardens function as hubs of social capital, strengthening bonds among participants through regular group activities. Weekly meetings, collaborative decision-making, and educational workshops foster mutual trust, shared responsibility, and a sense of collective identity within the community. These internal dynamics underscore the multifaceted value of CGs in enhancing quality of life at the individual and group levels.

External impacts

Beyond their internal community benefits, CGs in the Klang Valley generate substantial external impacts across education, food security, and local economies. Gardens such as Kebun-Kebun Bangsar and TTDI have evolved into open-access learning spaces, frequently hosting school visits, volunteer programs, and public workshops. These initiatives contribute to environmental awareness, agricultural literacy, and intergenerational knowledge sharing within urban communities. In terms of food security, CGs play a modest yet meaningful role by cultivating and donating produce to soup kitchens and vulnerable households, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. This community-based food distribution aligns with broader global strategies such as those outlined in the Global Hunger Index (2023), which emphasizes localized solutions to food insecurity.

Additionally, CGs support local economic resilience by creating opportunities for income generation. Several gardens facilitate the sale of seedlings, organic produce bundles, and compost products, often leveraging digital platforms to reach broader audiences. These initiatives also empower micro-entrepreneurs, particularly women and youth, by offering shared marketplaces, promotional support, and training in agro-based business practices. Overall, the external impacts of CGs reflect their growing relevance as decentralized hubs of education, nutrition, and grassroots enterprise within Malaysia’s urban development landscape.

Innovation, technology, and sustainability practices

The long-term sustainability of CGs is closely tied to their ability to innovate and adapt to urban constraints. This includes the evolution of farming methods, the adoption of relevant technologies, and the efficient use of local resources. Observations from the five case studies in the Klang Valley reveal considerable variation in the degree of innovation and technological integration across CGs, reflecting differences in leadership, access to resources and training.

Innovation in farming

Gardens showcased diverse approaches to farming and planting systems. Community Garden C (CG C) stood out for its crop variety and systems integration, cultivating a wide range of leafy greens, herbs, edible flowers, and fish through aquaponic methods (Table 1). Meanwhile, CG E introduced experimental rice cultivation using unconventional media such as styrofoam boxes, indicating a willingness to explore alternative production models in limited spaces. Organic and sustainable practices were prevalent in several gardens, particularly CG D where composting, vermiculture, and integrated pest management were routinely employed. Additionally, CG D adopted permaculture-based garden design, optimizing land use efficiency and reducing environmental impact. These design innovations supported higher yields while promoting ecological balance within the garden ecosystem.

Technology use

Technological adoption across the sampled CGs varied in scale and effectiveness. Advanced tools such as solar-powered irrigation systems were implemented in CG D, while CG A and CG E utilized fertigation systems to improve water and nutrient delivery. CG C employed greenhouse structures to support year-round production and crop protection. However, several gardens encountered challenges in fully utilizing available technologies. For instance, CG A had a hydroponic system but lacked the technical knowledge to operate it effectively, and CG B was unable to utilize a donated canopy fully due to space limitations. These issues highlight the need for technical training to accompany equipment provision.

Notably, only CG C and CG D practiced resource circularity by composting food and green waste, thereby lowering operational costs and minimizing their carbon footprint. These examples of waste-to-resource strategies underscore the potential for CGs to contribute to local sustainability goals through innovation and community-based environmental stewardship.

Social enterprise framework

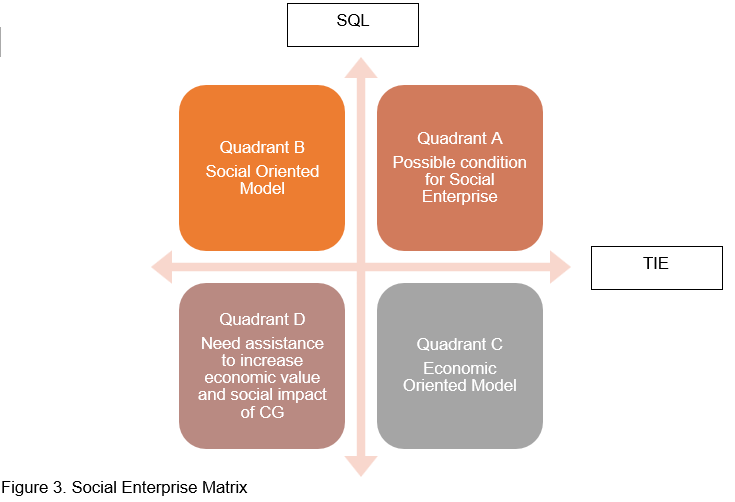

To assess their enterprise potential more systematically, the study employed a dual-axis framework adapted from Saebi et al. (2019) and Roy et al. (2014), focusing on two core dimensions: Social and Quality of Life (SQL) that measure contributions to community well-being, education, and food access; and Technology, Innovation, and Economy (TIE), that evaluate farming systems, internal resource use, and financial viability. This framework enabled the placement of each CG within a four-quadrant matrix as in Figure 3.

Assessing CGs using the quadrant model offers valuable insights into their readiness to transition into fully functioning social enterprises. Among the five case studies, CG C and CG D emerged as the most enterprise-ready, driven by a combination of financial, social, and organizational strengths. CG D reported a 75% increase in revenue within a single year, driven by its diversified income streams, including produce sales, compost products, and educational programs. Both gardens demonstrated a consistent capacity to deliver community services such as food donations, training sessions, and environmental outreach while maintaining effective operational structures.

A key factor contributing to their enterprise readiness is the ability to build and leverage multi-stakeholder networks. These gardens actively engage with public and private sector partners, including telecommunication firms, government agencies, and various NGOs. Such partnerships have enabled access to sponsorships, technical assistance, and broader public visibility, critical enablers for scaling up their social and economic impact.

In contrast, CG B and CG E exhibited strong community engagement and social value, particularly in fostering food access and volunteerism. However, their limited revenue generation and underdeveloped business models pose significant challenges for achieving financial sustainability. Meanwhile, CG A demonstrated entrepreneurial potential through early adoption of technologies and crop marketing initiatives. Still, its success is currently hindered by weak community participation and a need for more strategic leadership. These findings suggest that while several CGs are socially impactful, targeted interventions are necessary to strengthen their commercial viability and governance systems to enable a successful transition to social enterprise models.

Based on the data collected in Table 1, these CGs can be positioned as in Figure 1. CG C, CG E and CG D fall in Quadrant A (ready for social enterprise). While CG A and CG E fall in Quadrant C (moderate potential), and CG B requires targeted intervention as it falls in Quadrant B. These dimensions are crucial for understanding the feasibility of adopting a social enterprise model within CGs in the Klang Valley.

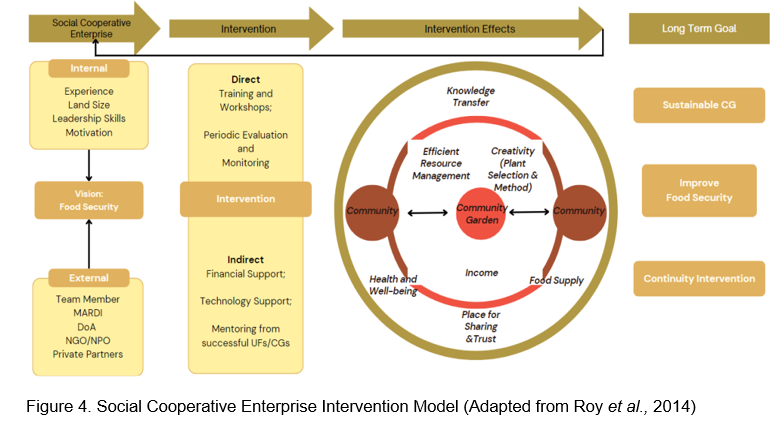

Therefore, the Social Enterprise with Intervention Model presents a more suitable approach, as demonstrated by Roy et al., (2014) in the context of healthcare-focused social enterprise. However, long-term goals for CGs should be robust in terms of food security, and measurement parameters need to consider internal motivation aspects in addition to other factors. To achieve this, a cooperative approach involving both CGs and their stakeholders is crucial. The model details are shown in Figure 4.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE POTENTIAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley exhibit the foundational elements of social enterprises, providing food, education, and community value, while attempting to sustain themselves through limited sales or donations. However, to transition into fully functioning social enterprises, CGs must formalize their operations, balance dual objectives (profit and purpose), and secure institutional support.

Understanding social enterprise in the context of CGs involves recognizing the intersection of economic activity and social impact. A social enterprise, as defined by Saebi, Foss, and Linder (2019), is an organization that employs market-based strategies to address social or environmental challenges. In agricultural settings, this approach enables the development of income-generating systems that not only support food security but also empower marginalized groups and promote ecological sustainability (Roy et al., 2014). Within CGs, the social enterprise model manifests through activities such as selling fresh produce, seedlings, or compost, offering paid training workshops or eco-tourism experiences, and forming partnerships with local restaurants, schools, and health-based NGOs. Crucially, the profits generated from these ventures are reinvested into the garden’s expansion or redirected toward community welfare initiatives. This dual-value model, combining financial viability with measurable social outcomes, positions social enterprise as a powerful framework for scaling CGs beyond mere subsistence into sustainable, community-anchored urban agriculture systems.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICYMAKERS AND STAKEHOLDERS

To ensure the sustainability and scalability of CGs in the Klang Valley, a concerted, multi-stakeholder strategy must be adopted. Policymakers, institutions, private entities, and local communities must work in synergy to remove structural barriers, provide targeted support, and create an enabling ecosystem for CGs to flourish as social enterprises.

Government agencies, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (KPKM), the Department of Agriculture (DOA), and the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI), play a pivotal role in mainstreaming CGs within national urban food strategies. Legal recognition of CGs is essential. Many currently operate on informal land arrangements, discouraging long-term investment. Thus, it is recommended that a formal registration mechanism be developed under the DOA to grant CGs secure land leases of three to five years. Urban zoning codes should also be amended to categorize CGs as community infrastructure, affording them basic protections and access to municipal services.

Further institutional support should include the establishment of MARDI-led urban agriculture advisory units. These units could offer site assessments, crop selection consultations, pest management guidance, and digital training modules tailored for CG leaders and volunteers. To address the financing gap, an Urban Agriculture Grant Program (UAGP) should be introduced. This fund would provide matching grants or microloans to CGs for infrastructural upgrades such as irrigation systems, composting stations, and protected farming units. The goal is not to promote dependency, but to catalyze self-reliance.

Local authorities and city councils also play a key role. They should proactively identify and allocate underutilized public spaces, rooftops, and vacant lots for CG development. This can be done in partnership with government-linked companies such as Tenaga Nasional Berhad or Telekom Malaysia. Local councils should also reduce bureaucratic friction by streamlining permit processes for CG events, composting activities, and the construction of basic facilities such as shades or greenhouses. The appointment of a dedicated CG Liaison Officer within each municipal council could further ease communication and procedural efficiency.

Civil society groups, NGOs, and academic institutions are well-positioned to provide non-financial support such as volunteer coordination, technical training, and impact documentation. Schools and universities can integrate CGs into service-learning curricula, promoting intergenerational knowledge transfer while offering real-life STEM applications. NGOs can also support the creation of a Community Garden Alliance (CGA), which is a horizontal network for CGs to share best practices, pool resources, and advocate collectively for policy change. Civil society organizations should also work to ensure CGs remain inclusive, encouraging participation from women, B40 youth, the elderly, Orang Asli, and persons with disabilities.

The private sector can make a significant contribution through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs. Companies can sponsor CG infrastructure or host employee volunteer days. Green retailers and cafés can enter into purchase agreements with CGs for organic produce, encouraging “community-grown” branding and consumer awareness. Meanwhile, agricultural startups and tech firms should collaborate with CGs to pilot affordable technologies such as solar irrigation systems or IoT sensors. These partnerships offer mutual benefits whereby startups gain testbeds for innovation, while CGs improve productivity.

CG leaders themselves must adopt more formalized management structures. Registering as cooperatives or societies under the Registrar of Societies (ROS) can help legitimize their operations and facilitate access to grants, legal contracts, and bulk procurement. CGs should also improve documentation by keeping records of harvest volumes, volunteer hours, training sessions, and community outreach. This data strengthens their funding proposals and aids in impact measurement. Engagement with schools and youth clubs is also critical. Gardens that serve as educational platforms, offering guided tours, farming classes, or biodiversity talks, tend to attract broader support and new leadership.

Finally, a phased implementation strategy is proposed. In the first six months, priority should be given to identifying and registering existing CGs and securing their land status. Over the next six to twelve months, MARDI should roll out training and technical support, complemented by financial disbursements through UAGP. By months 12 to 18, CGs can begin formalizing into social enterprises or cooperatives. The final phase involves scaling efforts, measuring outcomes, and integrating CGs into Malaysia’s National Agrofood Policy framework. This approach aligns with the Malaysia MADANI vision and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley are rapidly evolving from small-scale, volunteer-driven spaces into dynamic instruments of food security, community empowerment, and urban sustainability. As Malaysia continues to urbanize, the challenges of food access, environmental degradation, and social isolation are becoming more pressing. In this context, CGs represent a grassroots response that merges ecological consciousness with social innovation. They have the potential to fill critical gaps in Malaysia’s food system by promoting local production, reducing dependency on imports, and building resilience against supply chain disruptions.

This review shows that while CGs in the Klang Valley face considerable challenges — such as land insecurity, aging volunteers, limited financial sustainability, and bureaucratic hurdles —they also demonstrate significant strengths. The five gardens examined in this study reflect a spectrum of readiness for transformation into social enterprises, with CG C and CG D standing out as replicable models. These gardens not only provide produce but also serve as living laboratories for education, community building, and green entrepreneurship.

A key insight from this study is the value of adopting a social enterprise framework in scaling and sustaining community gardens. By balancing commercial activities such as selling produce, offering workshops, and leveraging tourism with social goals, CGs can become financially resilient while deepening their community contributions. The proposed Social Cooperative Enterprise Intervention Model offers a roadmap for stakeholders to guide this transition. Furthermore, global best practices from countries such as Singapore, Thailand, Japan, and Taiwan illustrate that CGs, when supported by policy, technology, and public participation, can flourish even in dense urban settings.

Policy alignment is essential. For CGs to succeed as social enterprises, they must be formally recognized within Malaysia’s urban planning and food security frameworks. This includes securing land tenure, providing targeted training, and facilitating access to grants and markets. Local authorities must simplify processes, while federal agencies such as MARDI and DOA should take the lead in providing extension services, knowledge transfer, and monitoring. NGOs and universities must support with outreach and training, while the private sector can contribute through CSR, technology partnerships, and supply chain integration.

Looking ahead, the creation of a Community Garden Network (CGN) could institutionalize support for CGs across Malaysia, beginning with the Klang Valley. This network would serve as a central platform for knowledge exchange, funding, certification, and advocacy. It would also enable Malaysia to document, monitor, and evaluate the contribution of CGs to national development goals, especially those related to health, food sovereignty, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability.

Future research should focus on measuring the long-term impacts of CGs on food security, urban biodiversity, and youth engagement. Quantitative impact studies can help policymakers allocate resources more effectively, while longitudinal case studies can reveal the lifecycle and scalability of successful CG models. Researchers may also explore the role of digital tools, blockchain, and agri-tech innovations in improving CG productivity and transparency.

In conclusion, community gardens offer more than just vegetables; they cultivate knowledge, resilience, and hope. By embracing a social enterprise approach, the Klang Valley's community gardens can become anchors of innovation, education, and inclusive development. With the right ecosystem in place, these green spaces can redefine urban living not just in Malaysia, but across Southeast Asia.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, A. A., Singh, K. S. J., Omar, N. R. N., & Muhammad, R. M. (2024). Factors Affecting Community Garden Leaders' Intentions to Sustain Community Gardens in Malaysia. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. 639-652. DOI: 10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.53.

Boossabong, P. (2018). Collaborative urban farming networks in Bangkok. In Cities in Asia by and for the People. Amsterdam University Press.

Global Hunger Index. (2023). Malaysia. https://www.globalhungerindex.org

Hashim, N. H., Mohd Hussain, N. H., & Ismail, A. (2020). Green roof concept analysis: A comparative study of urban farming practice in cities. Malaysian Journal of Sustainable Environment (MySE), 7(1), 115-132.

Hussain, M. R. M., Yusoff, N. H., Tukiman, I., & Abu Samah, M. A. (2019). Community perception and participation of urban farming activities. Int. J. of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8(1C2), 341–345.

Ishak, N., Abdullah, R., Mohd Rosli, N. S., Majid, H. A., Halim, N. S. A. A., & Ariffin, F. (2022). Challenges of urban garden initiatives for food security in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Quaestiones Geographicae, 41(4), 57-72.

Mabon, L., Shih, W. Y., & Jou, S. C. (2023). Farming Urbanism Network (FUN) in Taipei. Urban Studies, 60(5), 857–875.

Othman, N., Mohamad, M., Latip, R. A., & Ariffin, M. H. (2018). Urban farming activity towards sustainable wellbeing of urban dwellers. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 117, No. 1, p. 012007). IOP Publishing.

Roy, M., Donaldson, C., Baker, R., & Kerr, S. (2014). The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 182–193.

Saebi, T., Foss, N. J., & Linder, S. (2019). Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management, 45(1), 70–95.

Advancing Community Gardens in the Klang Valley, Malaysia through Social Enterprise

ABSTRACT

As Malaysia grapples with the dual challenges of urbanization and food insecurity, community gardens (CGs) are emerging as innovative responses to sustainable food production and community empowerment. This review paper explores the development, challenges, and transformative potential of CGs in the Klang Valley through a social enterprise lens. The paper highlights global best practices, introduces a social cooperative enterprise intervention model, and provides policy and practical recommendations for scaling CGs nationwide. Through collaborative governance, innovative farming, and inclusive participation, CGs can play a pivotal role in Malaysia’s sustainable urban development strategy.

Keywords: Community gardens, impact, social enterprise model, Klang Valley

INTRODUCTION

The intersection of urbanization and food security presents one of the most pressing challenges in the modern era. With rapid urban growth in regions such as the Klang Valley, Malaysia, the demand for locally sourced, affordable, and nutritious food has never been more urgent. Community gardens (CGs) are small-scale, community-driven agricultural initiatives located within urban environments and are increasingly recognized as practical solutions to address these challenges.

Community gardens in Malaysia is not a new concept and have gained renewed relevance under the Malaysia MADANI framework and the National Food Security Policy (2021–2025). These initiatives are supported by agencies such as the Department of Agriculture (DOA) and the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI). They serve multiple functions: enhancing household food security, reducing urban living costs, promoting healthy lifestyles, and fostering community cohesion.

Despite these benefits, the expansion and sustainability of CGs face numerous hurdles. These include limited access to land, inadequate funding, climate variability, low public awareness, and lack of technical knowledge among urban farmers (Ishak et al., 2022). Therefore, innovative frameworks are required to support these gardens not just as subsistence efforts, but as viable, community-driven enterprises.

This paper examines the potential of CGs in the Klang Valley to evolve into social enterprise models that blend economic goals with social missions. By drawing parallels with global practices in countries such as Singapore, Thailand, the USA, and Taiwan, the paper proposes strategies for integrating social entrepreneurship into Malaysia’s urban agriculture ecosystem.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON COMMUNITY GARDENS

Globally, CGs have become integral components of sustainable urban planning. In Singapore, where land scarcity is acute, the government promotes rooftop gardens to reduce reliance on food imports. These initiatives align with the city-state’s food resilience strategy and are embedded in housing and development policies (Mohd Hussain et al., 2020).

In Japan, particularly in Tokyo, regulations mandate green rooftops as part of building codes. These spaces not only serve environmental purposes but also function as productive agricultural zones, aligning with Japan’s vision of “urban forests.” Such policies are rooted in the cultural ethos of sustainability and collective responsibility.

The United States, especially cities like New York and Chicago, has institutionalized urban farming. The Brooklyn Grange in New York City stands as a commercial model of large-scale rooftop farming. By engaging diverse stakeholders—owners, volunteers, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) —this initiative demonstrates the economic viability of urban agriculture alongside environmental and social benefits (Mohd Hussain et al., 2020).

Thailand’s Bangkok City Farm Program provides another compelling model. By transforming rooftops into farming hubs and promoting composting from household waste, Bangkok supports the urban poor in cultivating their food. Moreover, it promotes social capital through community-based training, knowledge sharing, and alternative markets (Boossabong, 2018).

Similarly, Taiwan’s Taipei Garden City Program and the Farming Urbanism Network (FUN) exemplify institutional collaboration in urban agriculture. Through partnerships with universities, NGOs, and municipalities, Taipei has created over 800 urban gardens, many of which are run by community groups that influence local food policy (Mabon, Shih & Jou, 2023). These international examples demonstrate that CGs, when supported by policy, community engagement, and sustainable design, can evolve into impactful enterprises.

COMMUNITY GARDENS IN KLANG VALLEY: OVERVIEW AND CHALLENGES

In Malaysia, the Klang Valley encompasses the nation's most urbanized and densely populated region. As urban sprawl increases, food accessibility becomes strained, particularly for low-income communities. According to the Global Hunger Index (2023), Malaysia's score has fallen from 17.3 in 2015 to 12.7 in 2023, placing it in the moderate category for hunger severity, signaling systemic issues in food distribution and affordability.

A survey identified 34 community gardens operating in the Klang Valley, ranging from small hobby farms to structured community projects (Ahmad et al., 2022). These gardens primarily grow vegetables such as chili, lettuce, spinach, and eggplant, often using organic or semi-organic methods. However, their scale, productivity, and sustainability vary considerably.

CGs in the Klang Valley face several structural and operational challenges that hinder their long-term sustainability and impact. One of the most pressing issues involves land tenure and legal constraints. Many CGs are established on plots of land that are temporarily granted or even illegally occupied, often without formal documentation or agreements. This legal ambiguity not only discourages investment in infrastructure and innovation but also leaves CGs vulnerable to eviction or redevelopment.

Financial sustainability is another significant concern. Most CGs rely on inconsistent government grants, ad-hoc donations, or internal member contributions. Limited access to credit and the absence of structured revenue models make it difficult for these gardens to scale their operations or adopt modern technologies that could enhance productivity and efficiency (Ishak et al., 2022).

Moreover, there is a notable deficiency in technical expertise and labor. Urban farmers often lack formal agricultural training, relying instead on trial-and-error approaches or informal knowledge sharing. The core workforce typically consists of retirees or volunteers, which raises concerns about long-term viability, physical capacity, and knowledge continuity.

Environmental factors further exacerbate these challenges. Unpredictable rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and extreme heat —likely amplified by climate change —complicate crop planning, irrigation management, and overall garden resilience (Hussain et al., 2019). These conditions increase the risk of crop failure, especially in gardens without proper shelter, drainage, or water-harvesting systems.

Lastly, limited youth involvement threatens the generational sustainability of CGs. Young people are often disengaged due to time constraints, lack of incentives, or the perception that urban farming lacks innovation or income potential. Without targeted outreach and opportunities for youth participation, CGs risk stagnation and leadership vacuums soon. Despite these challenges, they also present strategic entry points for policy and innovation. By adopting hybrid economic models such as social enterprises, CGs can access new funding streams, formalize their operations, and enhance their appeal to younger demographics and institutional partners.

READINESS TO ADOPT SOCIAL ENTERPRISE FRAMEWORK IN SELECTED COMMUNITY GARDENS

Overview of the selected community gardens

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of five selected CGs located in the Klang Valley, highlighting their key characteristics, challenges, and potential for transitioning into social enterprises. The table includes details such as the year of establishment, land size, farming approach, and main crops cultivated. It also outlines notable innovations implemented at each site, ranging from rainwater harvesting systems to aquaponics and solar-powered monitoring tools. Additionally, the table summarizes the specific operational challenges faced by each garden, including community involvement, aging membership, limited funding, and land-use constraints.

Table 1. Overview of the selected community gardens in the Klang Valley.

CG

Location & Year of establish-ment

Land size

Farming type

Key crops

Innovations

Challenges

A

Sepang, 2013

300 m²

Semi-organic

Eggplant, cabbage, chili

Self-watering containers, rainwater harvesting, and fertigation

Minimal community involvement, financial loss, pest threats, and inconsistent sponsorship

B

Subang Jaya, 2019

45 m²

Semi-organic

Leafy greens

Limited vertical gardening, fertigation

Space constraints, aging members, stagnant income, limited support

C

Kajang,

2005

8,094 m²

Organic + Aquaponics

Leafy greens, herbs, edible flowers, fish

Greenhouse, composting, companion planting, banana circle

Volunteer shortage, no formal technology training, underutilized land

D

TTDI, 2017

1,393 m²

Fully organic

Root vegetables, herbs, fruit

Solar monitoring, composting, wood chippers, permaculture

Local bureaucracy, rigid regulatory flexibility

E

Klang, 2018

1,011 m²

Semi-organic + Experimental rice

Vegetables, fruits, rice

Fertigation, barrel planters, Styrofoam rice boxes

Low monetization, despite strong agency support

CGs in Klang Valley contribute directly to the socio-economic well-being of their members and surrounding communities. Their impact can be categorized into internal benefits (experienced by CG members) and external benefits (affecting the broader community).

Internal impacts

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley have demonstrated notable internal impacts on the well-being, food security, and social cohesion of their members. One of the most frequently cited benefits is improved mental and physical health, particularly among older participants. As reported by Othman et al. (2018), involvement in gardening activities fosters a sense of purpose and therapeutic value, making these green spaces especially beneficial for retirees, the elderly, and individuals managing chronic illnesses. In addition to health outcomes, CGs have also contributed to tangible economic savings.

According to a report by MARDI, the primary goal of urban farming practices is to encourage residents, particularly those residing in high-rise buildings, to cultivate food crops for their daily consumption. This approach is expected to lower the cost of food production by minimising expenses. The Community Garden (CG) program was also designed to foster public participation and improve food supply for low-income populations, thereby helping to reduce household spending. It provided clear evidence of the program's financial impact which reported that the average monthly food expenses for participants before enrolling in the CG program were RM133.18 (US$31.33). Analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in these expenses, which fell to an average of RM78.76 (US$18.53) per month (Figure 1). The study further indicated that CG leaders in urban areas experienced a more substantial reduction in household expenditure than their counterparts in rural regions (Figure 2).

Before joining

After joining

RM133.18 (US$31.33)

RM78.76 (US$18.53)

Figure 1. Monthly household food expenditure

Urban

Rural

RM71.75 (US$16.88)

RM43.44 (US$10.22)

Figure 2. Average monthly reduction of food expenditure

Beyond economic and health benefits, CGs play a significant role in informal skills development. Members frequently gain hands-on experience in areas such as organic farming, composting, irrigation systems, and seed propagation. These competencies, while often self-taught or peer-shared, hold potential for commercialization and entrepreneurship. Additionally, the gardens function as hubs of social capital, strengthening bonds among participants through regular group activities. Weekly meetings, collaborative decision-making, and educational workshops foster mutual trust, shared responsibility, and a sense of collective identity within the community. These internal dynamics underscore the multifaceted value of CGs in enhancing quality of life at the individual and group levels.

External impacts

Beyond their internal community benefits, CGs in the Klang Valley generate substantial external impacts across education, food security, and local economies. Gardens such as Kebun-Kebun Bangsar and TTDI have evolved into open-access learning spaces, frequently hosting school visits, volunteer programs, and public workshops. These initiatives contribute to environmental awareness, agricultural literacy, and intergenerational knowledge sharing within urban communities. In terms of food security, CGs play a modest yet meaningful role by cultivating and donating produce to soup kitchens and vulnerable households, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. This community-based food distribution aligns with broader global strategies such as those outlined in the Global Hunger Index (2023), which emphasizes localized solutions to food insecurity.

Additionally, CGs support local economic resilience by creating opportunities for income generation. Several gardens facilitate the sale of seedlings, organic produce bundles, and compost products, often leveraging digital platforms to reach broader audiences. These initiatives also empower micro-entrepreneurs, particularly women and youth, by offering shared marketplaces, promotional support, and training in agro-based business practices. Overall, the external impacts of CGs reflect their growing relevance as decentralized hubs of education, nutrition, and grassroots enterprise within Malaysia’s urban development landscape.

Innovation, technology, and sustainability practices

The long-term sustainability of CGs is closely tied to their ability to innovate and adapt to urban constraints. This includes the evolution of farming methods, the adoption of relevant technologies, and the efficient use of local resources. Observations from the five case studies in the Klang Valley reveal considerable variation in the degree of innovation and technological integration across CGs, reflecting differences in leadership, access to resources and training.

Innovation in farming

Gardens showcased diverse approaches to farming and planting systems. Community Garden C (CG C) stood out for its crop variety and systems integration, cultivating a wide range of leafy greens, herbs, edible flowers, and fish through aquaponic methods (Table 1). Meanwhile, CG E introduced experimental rice cultivation using unconventional media such as styrofoam boxes, indicating a willingness to explore alternative production models in limited spaces. Organic and sustainable practices were prevalent in several gardens, particularly CG D where composting, vermiculture, and integrated pest management were routinely employed. Additionally, CG D adopted permaculture-based garden design, optimizing land use efficiency and reducing environmental impact. These design innovations supported higher yields while promoting ecological balance within the garden ecosystem.

Technology use

Technological adoption across the sampled CGs varied in scale and effectiveness. Advanced tools such as solar-powered irrigation systems were implemented in CG D, while CG A and CG E utilized fertigation systems to improve water and nutrient delivery. CG C employed greenhouse structures to support year-round production and crop protection. However, several gardens encountered challenges in fully utilizing available technologies. For instance, CG A had a hydroponic system but lacked the technical knowledge to operate it effectively, and CG B was unable to utilize a donated canopy fully due to space limitations. These issues highlight the need for technical training to accompany equipment provision.

Notably, only CG C and CG D practiced resource circularity by composting food and green waste, thereby lowering operational costs and minimizing their carbon footprint. These examples of waste-to-resource strategies underscore the potential for CGs to contribute to local sustainability goals through innovation and community-based environmental stewardship.

Social enterprise framework

To assess their enterprise potential more systematically, the study employed a dual-axis framework adapted from Saebi et al. (2019) and Roy et al. (2014), focusing on two core dimensions: Social and Quality of Life (SQL) that measure contributions to community well-being, education, and food access; and Technology, Innovation, and Economy (TIE), that evaluate farming systems, internal resource use, and financial viability. This framework enabled the placement of each CG within a four-quadrant matrix as in Figure 3.

Assessing CGs using the quadrant model offers valuable insights into their readiness to transition into fully functioning social enterprises. Among the five case studies, CG C and CG D emerged as the most enterprise-ready, driven by a combination of financial, social, and organizational strengths. CG D reported a 75% increase in revenue within a single year, driven by its diversified income streams, including produce sales, compost products, and educational programs. Both gardens demonstrated a consistent capacity to deliver community services such as food donations, training sessions, and environmental outreach while maintaining effective operational structures.

A key factor contributing to their enterprise readiness is the ability to build and leverage multi-stakeholder networks. These gardens actively engage with public and private sector partners, including telecommunication firms, government agencies, and various NGOs. Such partnerships have enabled access to sponsorships, technical assistance, and broader public visibility, critical enablers for scaling up their social and economic impact.

In contrast, CG B and CG E exhibited strong community engagement and social value, particularly in fostering food access and volunteerism. However, their limited revenue generation and underdeveloped business models pose significant challenges for achieving financial sustainability. Meanwhile, CG A demonstrated entrepreneurial potential through early adoption of technologies and crop marketing initiatives. Still, its success is currently hindered by weak community participation and a need for more strategic leadership. These findings suggest that while several CGs are socially impactful, targeted interventions are necessary to strengthen their commercial viability and governance systems to enable a successful transition to social enterprise models.

Based on the data collected in Table 1, these CGs can be positioned as in Figure 1. CG C, CG E and CG D fall in Quadrant A (ready for social enterprise). While CG A and CG E fall in Quadrant C (moderate potential), and CG B requires targeted intervention as it falls in Quadrant B. These dimensions are crucial for understanding the feasibility of adopting a social enterprise model within CGs in the Klang Valley.

Therefore, the Social Enterprise with Intervention Model presents a more suitable approach, as demonstrated by Roy et al., (2014) in the context of healthcare-focused social enterprise. However, long-term goals for CGs should be robust in terms of food security, and measurement parameters need to consider internal motivation aspects in addition to other factors. To achieve this, a cooperative approach involving both CGs and their stakeholders is crucial. The model details are shown in Figure 4.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE POTENTIAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley exhibit the foundational elements of social enterprises, providing food, education, and community value, while attempting to sustain themselves through limited sales or donations. However, to transition into fully functioning social enterprises, CGs must formalize their operations, balance dual objectives (profit and purpose), and secure institutional support.

Understanding social enterprise in the context of CGs involves recognizing the intersection of economic activity and social impact. A social enterprise, as defined by Saebi, Foss, and Linder (2019), is an organization that employs market-based strategies to address social or environmental challenges. In agricultural settings, this approach enables the development of income-generating systems that not only support food security but also empower marginalized groups and promote ecological sustainability (Roy et al., 2014). Within CGs, the social enterprise model manifests through activities such as selling fresh produce, seedlings, or compost, offering paid training workshops or eco-tourism experiences, and forming partnerships with local restaurants, schools, and health-based NGOs. Crucially, the profits generated from these ventures are reinvested into the garden’s expansion or redirected toward community welfare initiatives. This dual-value model, combining financial viability with measurable social outcomes, positions social enterprise as a powerful framework for scaling CGs beyond mere subsistence into sustainable, community-anchored urban agriculture systems.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICYMAKERS AND STAKEHOLDERS

To ensure the sustainability and scalability of CGs in the Klang Valley, a concerted, multi-stakeholder strategy must be adopted. Policymakers, institutions, private entities, and local communities must work in synergy to remove structural barriers, provide targeted support, and create an enabling ecosystem for CGs to flourish as social enterprises.

Government agencies, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (KPKM), the Department of Agriculture (DOA), and the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI), play a pivotal role in mainstreaming CGs within national urban food strategies. Legal recognition of CGs is essential. Many currently operate on informal land arrangements, discouraging long-term investment. Thus, it is recommended that a formal registration mechanism be developed under the DOA to grant CGs secure land leases of three to five years. Urban zoning codes should also be amended to categorize CGs as community infrastructure, affording them basic protections and access to municipal services.

Further institutional support should include the establishment of MARDI-led urban agriculture advisory units. These units could offer site assessments, crop selection consultations, pest management guidance, and digital training modules tailored for CG leaders and volunteers. To address the financing gap, an Urban Agriculture Grant Program (UAGP) should be introduced. This fund would provide matching grants or microloans to CGs for infrastructural upgrades such as irrigation systems, composting stations, and protected farming units. The goal is not to promote dependency, but to catalyze self-reliance.

Local authorities and city councils also play a key role. They should proactively identify and allocate underutilized public spaces, rooftops, and vacant lots for CG development. This can be done in partnership with government-linked companies such as Tenaga Nasional Berhad or Telekom Malaysia. Local councils should also reduce bureaucratic friction by streamlining permit processes for CG events, composting activities, and the construction of basic facilities such as shades or greenhouses. The appointment of a dedicated CG Liaison Officer within each municipal council could further ease communication and procedural efficiency.

Civil society groups, NGOs, and academic institutions are well-positioned to provide non-financial support such as volunteer coordination, technical training, and impact documentation. Schools and universities can integrate CGs into service-learning curricula, promoting intergenerational knowledge transfer while offering real-life STEM applications. NGOs can also support the creation of a Community Garden Alliance (CGA), which is a horizontal network for CGs to share best practices, pool resources, and advocate collectively for policy change. Civil society organizations should also work to ensure CGs remain inclusive, encouraging participation from women, B40 youth, the elderly, Orang Asli, and persons with disabilities.

The private sector can make a significant contribution through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs. Companies can sponsor CG infrastructure or host employee volunteer days. Green retailers and cafés can enter into purchase agreements with CGs for organic produce, encouraging “community-grown” branding and consumer awareness. Meanwhile, agricultural startups and tech firms should collaborate with CGs to pilot affordable technologies such as solar irrigation systems or IoT sensors. These partnerships offer mutual benefits whereby startups gain testbeds for innovation, while CGs improve productivity.

CG leaders themselves must adopt more formalized management structures. Registering as cooperatives or societies under the Registrar of Societies (ROS) can help legitimize their operations and facilitate access to grants, legal contracts, and bulk procurement. CGs should also improve documentation by keeping records of harvest volumes, volunteer hours, training sessions, and community outreach. This data strengthens their funding proposals and aids in impact measurement. Engagement with schools and youth clubs is also critical. Gardens that serve as educational platforms, offering guided tours, farming classes, or biodiversity talks, tend to attract broader support and new leadership.

Finally, a phased implementation strategy is proposed. In the first six months, priority should be given to identifying and registering existing CGs and securing their land status. Over the next six to twelve months, MARDI should roll out training and technical support, complemented by financial disbursements through UAGP. By months 12 to 18, CGs can begin formalizing into social enterprises or cooperatives. The final phase involves scaling efforts, measuring outcomes, and integrating CGs into Malaysia’s National Agrofood Policy framework. This approach aligns with the Malaysia MADANI vision and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Community gardens (CGs) in the Klang Valley are rapidly evolving from small-scale, volunteer-driven spaces into dynamic instruments of food security, community empowerment, and urban sustainability. As Malaysia continues to urbanize, the challenges of food access, environmental degradation, and social isolation are becoming more pressing. In this context, CGs represent a grassroots response that merges ecological consciousness with social innovation. They have the potential to fill critical gaps in Malaysia’s food system by promoting local production, reducing dependency on imports, and building resilience against supply chain disruptions.

This review shows that while CGs in the Klang Valley face considerable challenges — such as land insecurity, aging volunteers, limited financial sustainability, and bureaucratic hurdles —they also demonstrate significant strengths. The five gardens examined in this study reflect a spectrum of readiness for transformation into social enterprises, with CG C and CG D standing out as replicable models. These gardens not only provide produce but also serve as living laboratories for education, community building, and green entrepreneurship.

A key insight from this study is the value of adopting a social enterprise framework in scaling and sustaining community gardens. By balancing commercial activities such as selling produce, offering workshops, and leveraging tourism with social goals, CGs can become financially resilient while deepening their community contributions. The proposed Social Cooperative Enterprise Intervention Model offers a roadmap for stakeholders to guide this transition. Furthermore, global best practices from countries such as Singapore, Thailand, Japan, and Taiwan illustrate that CGs, when supported by policy, technology, and public participation, can flourish even in dense urban settings.

Policy alignment is essential. For CGs to succeed as social enterprises, they must be formally recognized within Malaysia’s urban planning and food security frameworks. This includes securing land tenure, providing targeted training, and facilitating access to grants and markets. Local authorities must simplify processes, while federal agencies such as MARDI and DOA should take the lead in providing extension services, knowledge transfer, and monitoring. NGOs and universities must support with outreach and training, while the private sector can contribute through CSR, technology partnerships, and supply chain integration.

Looking ahead, the creation of a Community Garden Network (CGN) could institutionalize support for CGs across Malaysia, beginning with the Klang Valley. This network would serve as a central platform for knowledge exchange, funding, certification, and advocacy. It would also enable Malaysia to document, monitor, and evaluate the contribution of CGs to national development goals, especially those related to health, food sovereignty, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability.

Future research should focus on measuring the long-term impacts of CGs on food security, urban biodiversity, and youth engagement. Quantitative impact studies can help policymakers allocate resources more effectively, while longitudinal case studies can reveal the lifecycle and scalability of successful CG models. Researchers may also explore the role of digital tools, blockchain, and agri-tech innovations in improving CG productivity and transparency.

In conclusion, community gardens offer more than just vegetables; they cultivate knowledge, resilience, and hope. By embracing a social enterprise approach, the Klang Valley's community gardens can become anchors of innovation, education, and inclusive development. With the right ecosystem in place, these green spaces can redefine urban living not just in Malaysia, but across Southeast Asia.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, A. A., Singh, K. S. J., Omar, N. R. N., & Muhammad, R. M. (2024). Factors Affecting Community Garden Leaders' Intentions to Sustain Community Gardens in Malaysia. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. 639-652. DOI: 10.15405/epsbs.2024.05.53.

Boossabong, P. (2018). Collaborative urban farming networks in Bangkok. In Cities in Asia by and for the People. Amsterdam University Press.

Global Hunger Index. (2023). Malaysia. https://www.globalhungerindex.org

Hashim, N. H., Mohd Hussain, N. H., & Ismail, A. (2020). Green roof concept analysis: A comparative study of urban farming practice in cities. Malaysian Journal of Sustainable Environment (MySE), 7(1), 115-132.

Hussain, M. R. M., Yusoff, N. H., Tukiman, I., & Abu Samah, M. A. (2019). Community perception and participation of urban farming activities. Int. J. of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8(1C2), 341–345.

Ishak, N., Abdullah, R., Mohd Rosli, N. S., Majid, H. A., Halim, N. S. A. A., & Ariffin, F. (2022). Challenges of urban garden initiatives for food security in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Quaestiones Geographicae, 41(4), 57-72.

Mabon, L., Shih, W. Y., & Jou, S. C. (2023). Farming Urbanism Network (FUN) in Taipei. Urban Studies, 60(5), 857–875.

Othman, N., Mohamad, M., Latip, R. A., & Ariffin, M. H. (2018). Urban farming activity towards sustainable wellbeing of urban dwellers. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 117, No. 1, p. 012007). IOP Publishing.

Roy, M., Donaldson, C., Baker, R., & Kerr, S. (2014). The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 182–193.

Saebi, T., Foss, N. J., & Linder, S. (2019). Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management, 45(1), 70–95.