ABSTRACT

Thailand is a tropical country in Southeast Asia with coastlines on both the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, covering a total of 18 provinces suitable for seaweed farming. The most cultivated economic seaweed at present is sea grape (Caulerpa lentillifera), which is cultivated in many provinces using various methods. This article provides general information on seaweeds used in Thailand, especially sea grapes, including cultivation methods, basic information on the number of farms, production volumes, and income. In 2023, there are 167 sea grape farms in Thailand, covering an area of approximately 553.12 rai (88.50 hectares) and producing more than 1,340.18 tons of sea grapes annually. Phetchaburi province is one of the largest producers of sea grapes, with an estimated output of 1,084.68 tons, worth more than 42.69 million Baht (~US$1.3 million)[1]. In the past, Thailand lacked a direct standard for seaweed farming, instead relying on general aquaculture standards. However, in 2019, a standard for agricultural products, the Good Aquaculture Practice for Seaweed Farms (GAP 7434(G)-2562), was developed. Furthermore, the results of the study to evaluate and compare the feasibility of sea grape farming in earthen ponds and in cages were mentioned, which showed that both types of sea grape farming are suitable from a financial feasibility point of view, except for the sale of sea grape at US$0.35/kg, which would result in a loss. Additionally, the results of the SWOT analysis aid in formulating strategic recommendations for new entrepreneurs seeking to invest in commercial sea grape farming.

Keywords: Caulerpa lentillifera, GAP, Seaweed, Sea grape, SWOT analysis

INTRODUCTION

Thailand's coastline is approximately 3,148 km long, with 1,093 km on the west coast (Andaman Sea) and 2,055 km on the Gulf of Thailand. From sandy beaches to rocky shores and even muddy areas with dead coral fragments, everything is suitable for colonization by algae. More than 500 taxa of marine algae from Thailand have been recorded. Of these, 462 species have been identified. Many have not yet been identified or are listed as uncertain species. Of the identified species, 214 belong to the red algae, 123 to the green algae, 70 to the blue-green algae (cyanobacteria), and 55 to the brown algae (Lewmanomont and Chirapart, 2022). The use of seaweed as a food source in Thailand was initially limited to certain coastal regions. The most consumed seaweeds are Gracilaria, Porphyra, Caulerpa, Ulva, and Sargassum (Lewmanomont, 1998). They are eaten fresh, like salad vegetables, mixed with other ingredients, or added to soups. Due to changing consumer habits, numerous algae products and products containing algae extracts are now commercially available.

The domestic production of seaweed in Thailand is relatively low. However, as the country's consumption and utilization in the food and non-food sectors is high, Thailand is a net importer of seaweed and hydrocolloids. In general, Thailand imports edible seaweeds such as dried wakame, nori, agar strips, and powder for direct consumption, US$65.76 million in 2022 and US$119.36 million in 2024 (Thai Customs Department, 2025). China and the Republic of Korea are the primary sources of dried edible seaweed, with well-known brands such as Taokaenoi dominating the market. Hydrocolloids (carrageenan, agar, and alginate) are imported for the country's large food processing sector, which produces a wide range of ‘ready-to-cook and ‘ready-to-eat foods for the local and export markets. In addition to food for human consumption, Thailand has a large export-oriented animal feed industry that uses seaweed products as a binding agent (FAO, 2018a).

Due to the increasing popularity of seaweed as a healthy food, more seaweed is being cultivated for domestic consumption. This differs from the past, when seaweed was collected in the wild, and more and more people want to invest in seaweed cultivation, especially Caulerpa lentillifera, often referred to as "sea grape", because this type of seaweed has a beautiful and delicious appearance that attracts consumers. Additionally, other types of seaweed are being increasingly cultivated, such as Caulerpa corynephora, which is popular in southern Thailand. After 2014, the cultivation of sea grapes was introduced. They became popular as a healthy food option and generated additional profits for farmers.

The sea grape species C. lentillifera has been cultivated in land-based tanks in Okinawa, Japan, for many years. In the national aquaculture statistics of Japan, Vietnam, and China, cultivated sea grapes are not listed separately. Annual production in the three countries is around 600 tons, 300-400 tons, and over 1,000 tons, respectively (FAO, 2018b). The Philippines is the leading producer of sea grapes. In 2019, 1,090 tons of cultivated sea grapes were produced, excluding those collected in the wild (FAO, 2021). Commercial cultivation of sea grapes in Thailand began in 2014. Currently, there are no official reports on the actual production volumes from cultivation. Most of the data collected comes from farms registered with the Department of Fisheries, and the standards for seaweed farming were not established until 2019.

This article contains data on the cultivation of sea grape in Thailand, including utilization, basic information on the number of farms, production volumes, and income. The data are collected from current observations, primarily in Thai, along with data from our research, which includes interviews with seaweed farmers and related parties, as well as the experience of researchers who have been working with seaweed for over 20 years. In addition, the results of the study to evaluate and compare the feasibility of sea grape farming in earthen ponds and in cages, as well as the results of the SWOT analysis, on strategic recommendations for new entrepreneurs who want to invest in commercial sea grape farming.

CAULERPA UNTILIZATION IN THAILAND

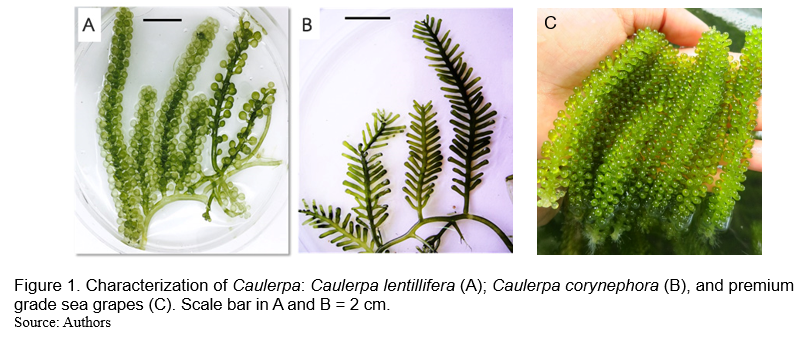

Caulerpa is a green alga that is often used as a salad vegetable. As it is rich in minerals, vitamins, trace elements, and bioactive substances, it has become a popular health food in recent years. The two most popular species are C. lentilifera and C. corynephora due to their succulent texture (Fig. 1).

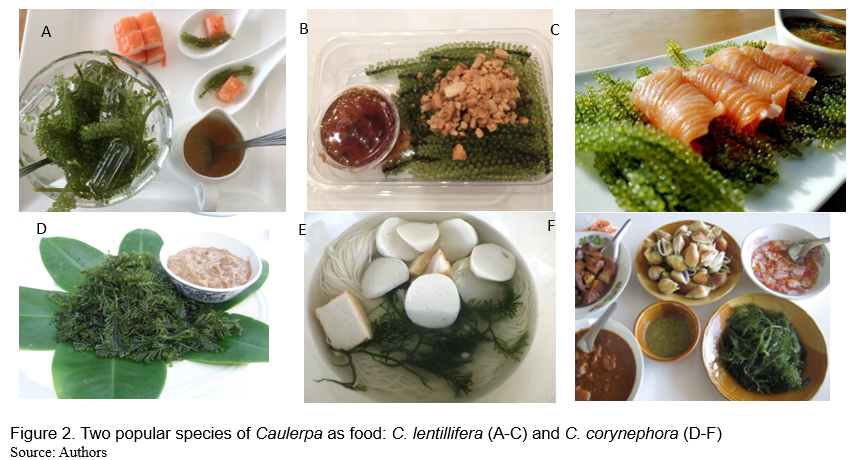

Caulerpa lentillifera, also known as “sea grape” or “green caviar”, has a tubular thallus that is connected without a dividing wall. It consists of horizontal stolons running parallel to the ground, which branch out upright from the ground and grow up to 10 cm high (Fig. 1A). The stolons are cylindrical, have a 1-1.5 mm diameter, and are provided with leaves or ramulus at the branches. The ramulus is spherical, translucent, densely arranged, and has a very short stem, almost connected to the axis. The ramulus has a diameter of 1-2 mm, is regularly branched, and has rhizoids that branch into fine hairs (Belleza and Liao, 2007). This species was previously used to treat wastewater from shrimp ponds. The plant's ability to absorb large concentrations of nutrients makes it a suitable candidate for the biofiltration of aquaculture effluent. It has also been found to thrive in various habitats, including ponds, and has recently been successfully cultivated for food. It is usually eaten fresh as a salad or dressed with a special Thai hot sauce (Fig. 2A-C). Sea grape is mainly cultivated in earth ponds. The retail price for this seaweed is between US$5.49-6.10/kg. The wholesale price is US$3.97-4.58/kg, depending on the quantity of each order. Most farmers sell the sea grapes in bunches. In addition, premium-grade sea grapes are also sold, i.e., sea grapes with a length of more than 3 inches (Fig. 1C). The selling price ranges from US$6.71 to 9.15/kg. The retail price during the rainy season is higher because the market produces less. The retail price for sea grapes in bunches is US$9.15/kg, while the wholesale price is US$9.15/kg, depending on the quantity of each order. During the rainy season, the retail price for premium sea grapes is US$10.68-21.35/kg. However, for several years now, there have been no orders from customers for the premium grade. Following the outbreak of COVID-19 at the end of 2019, the farm price for sea grapes has declined significantly, altering the sales model for sea grapes. Currently, many farmers sell sea grapes at retail and wholesale at the same price, with prices varying from farm to farm and depending on the quantity of sea grapes placed on the market at the time of trading. The farm price is US$3.05, 3.66, or 4.58/kg. In addition, most farms no longer categorize the quality of the algae as they used to. They now only sell the cluster quality and no longer the premium grade. A new form of sale has also been found: wholesale, where farmers wash the seaweed in the pond, then place it in a basket and weigh it for sale without sorting the quality of the seaweed and cleaning it, as is done when selling in clusters. The price for seaweed of sale from the whole pond depends on the quality of the seaweed at the time of purchase. Usually, the price for selling whole seaweed is US$1.22/kg.

Caulerpa corynephora, thallus branches sparsely from the stolons, the branching consisting of widely spaced ramifications extending to the tip of the branch (Fig. 1B). The thallus is club-shaped but with a constriction between the ramulus and the stem, 2-4 mm in diameter, opaque green, with fibrous roots that do not branch into fibrils (Belleza and Liao, 2007). This species was found growing only in the southern part of Thailand along the Andaman Sea coast, especially in Krabi, Trang, and Satun provinces. It has been consumed fresh by local people (Fig. 2D-E) and is now cultured in earth ponds and fish cages. The selling price of this seaweed is US$2.44-3.66/kg.

SEAGRAPE FARMING IN THAILAND

In the past, the cultivation of seaweed was not very popular in Thailand. Only Gracialria was accepted by the locals in the provinces of Songkhla and Pattani. In 2010, seaweed, particularly sea lettuce (Ulva rigida), was successfully cultivated for pond farming in Trat Province, followed by sea grape (C. lentillifera) in Phetchaburi Province in 2014. Currently, seaweed farming is well known in many provinces in southern Thailand, providing additional income for coastal fishermen.

Sea grape farming is popular in many provinces in southern Thailand, especially in the province of Phetchaburi, where seaweed cultivation has begun. More than 61 farms are active in this province. The farmers use the salt ponds, which no longer produce salt, and the abandoned shrimp ponds for sea grape cultivation. The Department of Fisheries is responsible for promoting and developing the commercial cultivation of seaweed through the Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre in Phetchaburi until it was successful in 2014. This center is responsible for technology transfer through training and knowledge transfer to farmers who have wanted to cultivate seaweed for over 10 years, to create additional income for the farmers.

There are three types of Caulerpa farming:

- Cultivation in earthen ponds

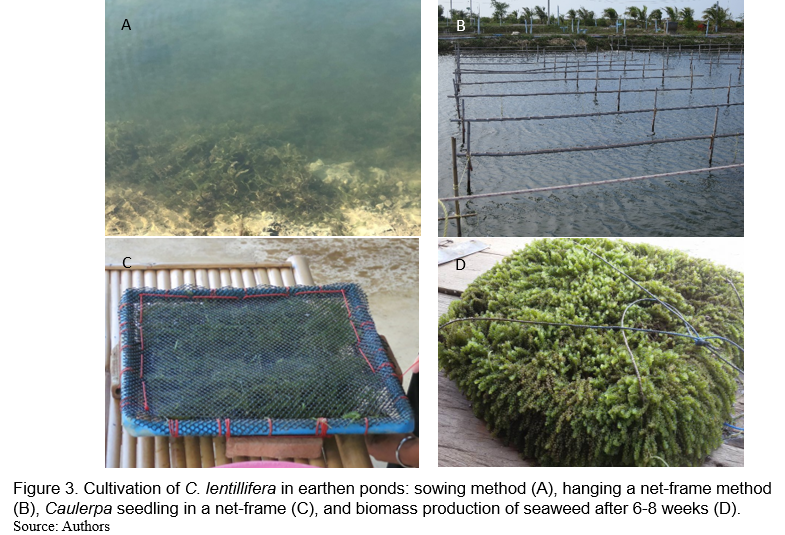

This type of cultivation can be divided into three methods: planting, sowing, and hanging a net-frame.

- 1) Planting: The Caulerpa seedlings are buried in the sandy and muddy bottom. The seedlings are cut back to have two branches on each side. After planting the seaweed, keep it at 1 m. Then fill the pond with water to a depth of 0.5 to 0.8 m. Sea water was slowly added to avoid damaging the algae seedlings. In the initial phase, change the seawater every 3 to 4 days, gradually increasing the frequency of water changes. If it rains, drain the pond immediately and refill it with seawater, as the seaweed cannot tolerate low salinity. After changing the water, apply 2.5 kg of urea fertilizer per rai (approximately 0.16 hectares). The fertilizer should be applied 1 to 2 weeks before harvesting. During cultivation, remove weeds from the pond as they compete for light and nutrients. Harvesting depends on the growth rate of the seaweed in the pond, approximately every 6-8 weeks. This involves harvesting the seaweed from the bottom of the pond, leaving about 25% of the seaweed as seedlings for the next harvest. After harvesting, wash the seaweed with seawater.

- 2) Sowing: This cultivation method has the same pond preparation method as planting. Caulerpa seedlings are sown on the bottom of a pond filled with seawater about 0.5-1.0 m deep or uniformly planted at approximately 1 m intervals (Fig. 3A). The appropriate sowing rate for seaweed stalks, recommended by the experience of seaweed farmers, is 200 kg/rai (approximately 1,250 kg/ha). The disadvantage of this sowing method, however, is that the seedlings do not adhere to the bottom of the pond when sown, so they easily fall off with the water current and do not spread evenly throughout the pond, resulting in uneven growth.

- 3 ) Hanging a net-frame: This cultivation method uses a 0.5 x 0.5 m2 mesh frame. The prepared sea grapes (500 g) are placed in a plastic frame, covered with another layer of plastic mesh, and tied together with a nylon rope to prevent the seedlings from slipping. The Caulerpa net frames are then hung in the culture pond with bamboo poles at a depth of 20 to 100 cm from the water surface, depending on the turbidity of the water, with the individual net frames spaced 1.5 m apart (Fig. 3B-C). After 6-8 weeks, check the plant density by pulling the frame up to the water's surface to see if the entire frame is densely covered enough for harvesting. Then, remove the frame from the water and cut the plants close to the net. The remaining plants on the frame can be cultivated again and harvesting can be done weekly thereafter.

Sea grape is adaptable to a variety of environments, making it suitable for cultivation in earthen ponds. Regular replacement of seawater is necessary to maintain the nutrient levels and ensure good water quality, which are essential for growth. The plants can be harvested after 6 to 8 weeks. In the dry season (December-April), sowing in the earthen ponds results in a total quantity of algae that is around twelve times the quantity of all the seedlings used before sorting, i.e. around 15,000 kg/ha. After sorting for sale in bundles, 50 % of the production remains for sale, i.e., around 7,500 kg/ha. The yield of sea grapes in the rainy season (May-October) is approximately 40% lower than in the dry season, with a yield of about 60% of the dry season yield, i.e., approximately 9,000 kg/ha. The sea grape production in this season is not very nice or has a less desirable quality than in the dry season, with only 30% or about 2,700 kg/ha reaching a saleable grade.

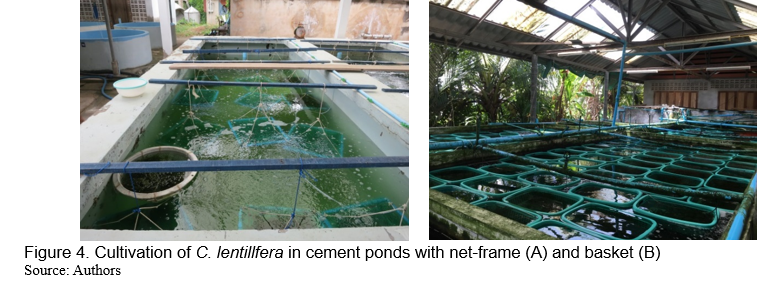

2. Cultivation in cement ponds or tanks. Cultivation of seaweed in cement ponds, plastic tanks, or fiber tanks can be carried out in small and large tanks. The tank used for cultivation has a volume of 1-2 m³. There are 2 types of cultivation: sawing and hanging a net-frame or a basket.

2.1) Sowing: This method uses a fiberglass tank or a cement tank into which seawater is pumped into a high tank with a muddy bottom. Plant the seaweed by burying it about 3 to 5 cm deep. Use C. lentillifera seedlings harvested from the wild. Cover the tank with clear plastic to prevent rainwater from entering. Change the water every 2-3 days with natural seawater. No fertilizer is added as the seawater contains sufficient nutrients. With seaweed grown at low density, no significant growth is observed in the first week, and the algae gain approximately 3-4 kg/m²/year. The cultivation period is about 2 months.

2.2) Hanging net frame or basket: In this method, C. lentillifera is cultivated in a cement tank by hanging a net frame or using a plastic basket and placing it in the tank (Fig. 4). The initial density of C. lentillifera was 0.5 kg/m². When C. lentillifera had reached 5.2 kg/m2 and 65 % of the algae had been harvested

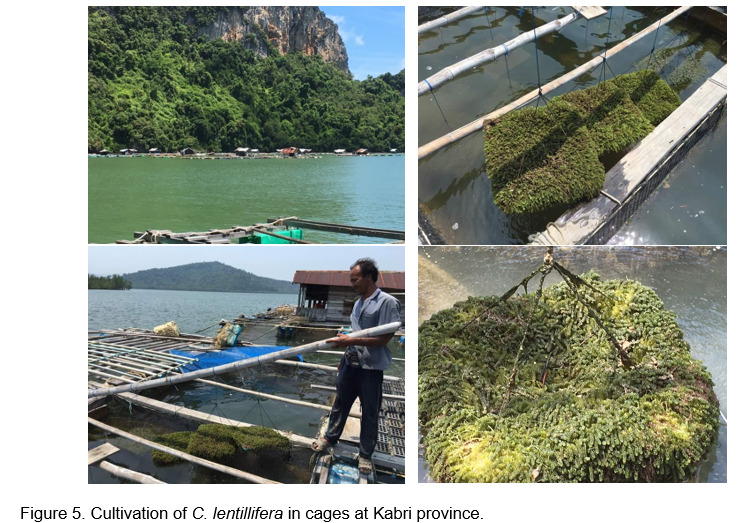

3.Cultivation in cages. The success of cultivating sea grapes in cages depends on selecting a suitable location, such as a fish cage at the mouth of a river. The algae can be harvested in summer when freshwater runoff is low. By adding 0.5 kg of seedlings per frame, 10 kg can be harvested per frame, i.e., approximately 20 times the number of seedlings added. After sorting, 50% of the products remain ready for sale, i.e., approximately 5 kg per frame. Of these, 2 kg are used as seedlings for the next cultivation, while the remaining 3 kg are discarded. Sea grapes can be cultured in cages all year round (about 3-4 crops/year). The biomass is 5-10 kg/m2/year. In the provinces of Satun, Trang, and Krabi, sea grapes are preferably grown in cages using the hanging frame method. The number of cages varies from 2 to 10 for small farms to more than 100 for large farms.

When comparing the cultivation methods, it was found that the sowing method resulted in a higher biomass of sea grapes than the net-frames method and that cultivation in earth ponds resulted in a higher biomass than in cement ponds or cages (Lewmanomont and Chirapart, 2022).

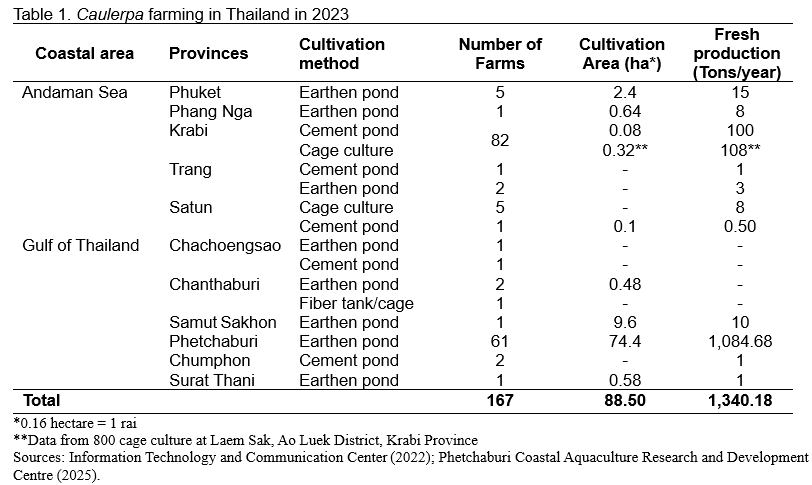

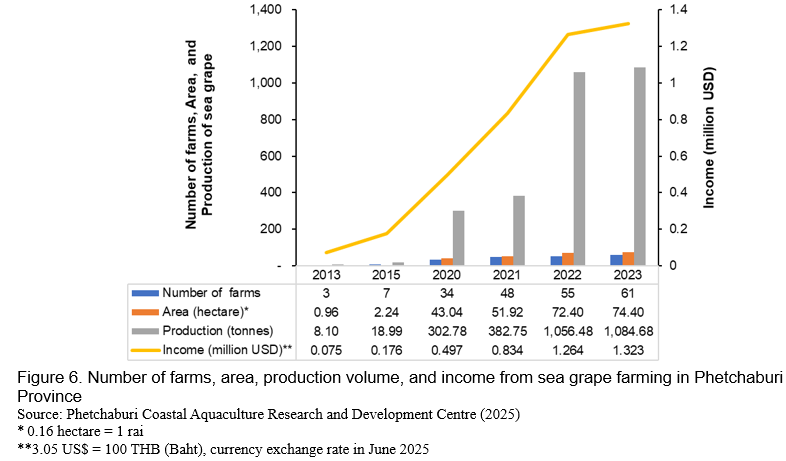

According to our research and information from the Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre, Department of Fisheries, there are currently 167 sea grape farms with an area of about 553.12 rai (88.50 hectares) and annual sea grape production of more than 1,340.18 tons/year (Table 1). However, the actual area under cultivation and production of sea grapes in some regions is not recorded. Therefore, the actual cultivation area and production volume are higher than stated. The area with the most sea grape farms in Thailand is Phetchaburi province. In 2023, there are 61 farms with an area of 465 rai (74.4 hectares) and an annual production volume of 1,084.68 tons, generating more than THB42.69 million (approximately US$1.30 million). It is estimated that the area under cultivation in Phetchaburi will increase by 188 rai (approximately 30.08 hectares) and the production volume will rise by around 200 tons by 2026, generating revenue of more than THB50 million (approximately US$1.53 million).

Good Aquaculture Practices for Seaweed Farms in Thailand

In the past, most seaweed with economic value was harvested from the wild. Today, due to environmental changes, the quantity and extent of natural seaweed has decreased significantly. Therefore, seaweed farming is crucial for planning the expansion of this industry. However, as there are no regulations, rules, or controls on the production process of seaweed in Thailand to produce high-quality, safe, and acceptable seaweeds for consumers, this represents an improvement in quality standards for agricultural products and increases the ability to compete in the international market. Quality issues that can occur with seaweed include inconsistent quality and cleanliness, heavy metal content, and ineffective storage methods to maintain quality over time. The quality of the seaweed obtained from farms depends on the environment in which the seaweed grows, especially the quality of the seawater used for cultivation. Based on the problems and trends in the demand for seaweed in the market, the National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards, together with the Department of Fisheries, developed the standard for agricultural products "Good Aquaculture Practices for Seaweed Farms (GAP 7434(G)-2562) " in 2019, as well as guidelines for the application of the standard, so that seaweed farmers can use it as a guide under the principles of food hygiene and safety, and so that farmers can produce seaweeds of a quality that meets market demand, thereby improving the quality standards of agricultural products and increasing competitiveness in the international market. The requirements include: 1. Farm registration, 2. Farm location, 3. General management, 4. Production factors, 5. Hygiene on the farm, 6. Harvest and post-harvest procedures before sale, 7. Social responsibility, 8. Environmental responsibility, and 9. Data collection. There are currently 26 certified seaweed farms. Of these, 23 are from Phetchaburi Province, 2 from Trang Province, and 1 from Chanthaburi Province. In addition, there are 9 farms that have applied for certification and are currently being audited (Fishery Product Standards Certification System Development and Traceability Evidence Division, 2025). Nevertheless, the number of farms that have received this standard is low compared to the total number of farms.

Feasibility analysis of seagrape farming

Currently, seaweed is being cultivated for domestic consumption, and an increasing number of people are interested in investing in seaweed farming, particularly sea grapes (C. lentillifera). There are various types and techniques of sea grape cultivation, including cultivation in earthen ponds (planting, sowing, and hanging net frames), cultivation in cages within natural water sources, and cultivation in cement ponds. These different methods of cultivation involve different costs and yields, which determine the value or non-value of each type of investment. Although seaweed cultivation is an investment opportunity that is currently attracting interest from farmers in Thailand and is being promoted by the Department of Fisheries, however, seaweed farmers still lack data on the feasibility of investing in seaweed cultivation. Market data, utilization (or demand), production volume data, and the number of seaweed farms (or supply) are essential data that can be used for investment considerations, such as whether the farms are suitable for seaweed production. For example, whether the investment is feasible in terms of production volume and number of seaweed farms (or supply), whether the investment is feasible in terms of technology, commercialization, and supply and demand, and most importantly, in terms of financing. This feasibility analysis data gives farmers who want to invest in seaweed cultivation the certainty that it is feasible in practice. It also provides guidance for selecting an efficient farming model with low costs, with yields or benefits that are worth the investment, and with which production capacity can be planned and production resources utilized for an effective investment.

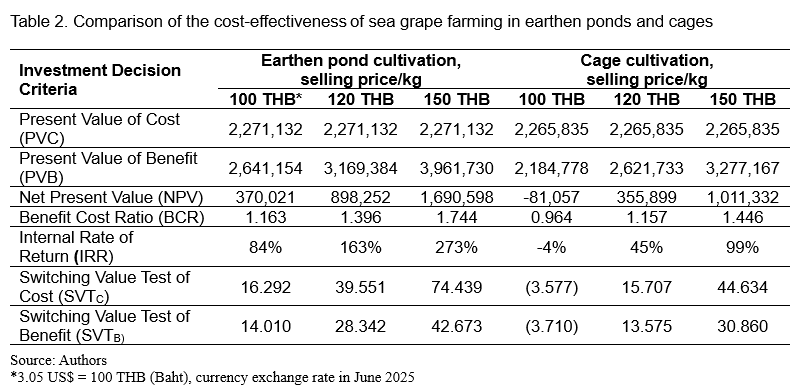

Our study was conducted during 2020-2021, the farming methods currently preferred by farmers in earthen ponds and cages were selected to investigate and analyze the cost-effectiveness of commercial farming and the feasibility of seaweed farming from various aspects, including the investigation and analysis of the internal and external environment of commercial sea grape farming in the two farming methods. The data was analyzed based on the project objectives to evaluate and compare the feasibility of the two investment projects between an investment project for commercial seaweed cultivation in earth ponds in Phetchaburi province with a cultivation area of 4 rai (approximately 0.64 ha) and an investment project for commercial seaweed cultivation in cages in Krabi province with an operation of 40 cages. The period for the investment projects is 5 years. The selling price of sea grapes is fixed in three cases: THB100, 120, and 150, which correspond to the current selling price on the farm.

Comparison of investment opportunities between sea grapes in earthen ponds and cages (Table 2). From the study on the feasibility of investing in the cultivation of sea grapes, taking into account the net present value (NPV), the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) and the internal rate of return (IRR) of the project from the cultivation in earth ponds with sowing method, the total cultivation area of 4 rai at a selling price/kg of THB100, 120 and 150 and the cultivation in 40 cages at the same selling price, it was found that the investment pays off in almost all cases, except for the cage cultivation at a selling price of THB100/kg, which has a negative net present value (NPV) of (-81.057). This means that with 40 cages and a selling price of THB100/kg over a 5-year project period, there would be a loss of THB81,057 (approximately US$2,472.76). Therefore, the selling price for sea grapes from cages should not be set at THB100/ kg. When comparing the return and value of commercial cultivation of sea grapes in earthen ponds and cages, it was found that cultivation in earthen ponds produced a higher return than cultivation in cages. The highest return on investment for cultivation in earth ponds was obtained at a selling price of THB150/kg (IRR = 273%), followed by a selling price of THB120/kg (IRR = 163%). The highest return on investment for cage farming was achieved at a selling price of THB150/kg (IRR = 99%), followed by a selling price of THB120/kg (IRR = 45%).

The sensitivity analysis, which aims to determine whether the decision on financial feasibility is still acceptable or not if the investment in a sea grape cultivation, compares the change in costs (SVTC) and the change in benefit due to the change in the price of sea grape (STVB) between cultivation in earth ponds and cultivation in cages to compare the investment risk. It was found that cultivating sea grapes in earth ponds is less risky than cultivating them in cages. It was also found that the sea grape selling price of THB150/kg from earth ponds cultivation has the lowest risk compared to the other cases with a variability of cost value (SVTC) of 74.44%, which means that the cost may increase by 74.44%, while the variability of benefit value (SVTB) is 42.67% or the return may decrease by 42.67%, resulting in a loss of the project. Regarding the sale of sea grapes from cage culture, considering the above break-even point, it was determined that they should not be sold for THB100/kg, as this would result in a loss. However, considering the case of selling at prices of THB120 and 150, the selling price of THB150/kg from cage cultivation was found to be less risky, with a variability of value of cost (SVTC) of 44.63% and a variability of value of benefit (SVTB) of 30.86%. This shows that the costs can only increase by 44.63% or the return can decrease by a maximum of 30.86%, which would lead to a project loss.

SWOT ANALYSIS OF SEA GRAPE FARMING

Based on a SWOT analysis of sea grape cultivation in earthen ponds and cages as a basis for strategic proposals for commercial sea grape cultivation using the TOWS matrix, a survey was conducted by our research group (2020-2021). The SWOT analysis was created to provide information for new entrepreneurs who want to invest in sea grape cultivation in ponds or cages. The internal factor analysis (strengths and weaknesses) of the seaweed farms analyzed in this study was divided into 5 categories: (1) the product, i.e. the seaweed production or investment project, (2) management and production, (3) research and development, (4) marketing, and (5) planning. When analyzing the external factors (opportunity and threat), the analysis can be divided into two types of factors: (1) macro-environmental factors, and (2) micro-environmental factors such as customers, competitors, distributors, and vendors. The results of the comparative analysis of internal and external factors (SWOT analysis) for new entrepreneurs interested in investing in commercial sea grape cultivation projects in earthen ponds or cages are summarized as follows.

- Strengths (S) – The product itself, i.e., sea grapes produced from both earth ponds and cages, is an interesting strength for new entrepreneurs, as sea grapes are nutritionally important and well known to consumers. The sea grapes produced by both farming methods are fresh and clean when they reach the consumer, as they have modern cleaning techniques. And since Phetchaburi province is not far from Bangkok and the central, eastern, northeastern, and northern regions, the transport of sea grapes to consumers in these regions is fast, and the sea grapes are still fresh. Another strength comes from the results of this research, which shows that the investment project for the cultivation of sea grapes is feasible in technical, financial, and marketing terms. However, the research results also show strengths in terms of investment planning, which is flexible in terms of production costs and returns, especially the financial feasibility of cultivation in earthen ponds, which is profitable in all three cases (except for cultivation in cages, where all production is sold at THB100/kg, resulting in a loss).

- Weaknesses (W) – Weaknesses that new entrepreneurs should consider are management and production issues, in which new entrepreneurs still have less experience than old entrepreneurs who are already farming sea grapes. New entrepreneurs still need time to develop their business so that it fulfils the standards for cultivation of sea grapes, which affects the image and credibility of the business. In terms of research and development, new entrepreneurs do not yet have the necessary expertise to research and develop products compared to their competitors. As far as marketing is concerned, new entrepreneurs often lack a market. They need time to find new marketing channels, which is a weakness that new entrepreneurs must carefully consider when entering the market, including selling, advertising, and identifying effective marketing channels. In addition, starting as a new entrepreneur can be challenging for outsiders, especially in cage farming, as most cage farming operations take place in public areas with limited space. The area must be declared acceptable by the provincial fisheries committee before a license can be applied for. It is usually reserved for the local population. If the entrepreneur has to invest more in land rent for rearing in earthen ponds than the project envisages (THB60,000 (~US$1,967.21) per year for 4 rai), new entrepreneurs should carefully plan to reduce other costs or increase profits to ensure the business remains profitable.

- Opportunities (O) - In terms of macro-environmental factors, entrepreneurs have opportunities through the Department of Fisheries, which promotes the standard of sea grape cultivation in the country and continuously supports sea grape cultivation for farmers, especially sea grape cultivation in earthen ponds. Opportunities also exist in micro-environmental factors, i.e. popularity and consumption demand from both domestic and international customers. In addition, there are currently opportunities in relation to the various distribution channels, including online sales.

- Threats (T) – In terms of macro-environmental factors, the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus has a significant impact on sales and prices of ponds and cages in both the short and long term. Additionally, recovering the business after the outbreak of the virus is challenging, especially for cage farmers. In terms of micro-environmental factors, the current household economy of consumers or customers in the country is not as good as it should be. If the selling price is set too high, customers may not have enough purchasing power. There is also an obstacle for competitors as farmers who are already farming have more experience and an established customer base. They also take prices from each other. Therefore, new entrepreneurs entering the market must have suitable strategies to compete in the market.

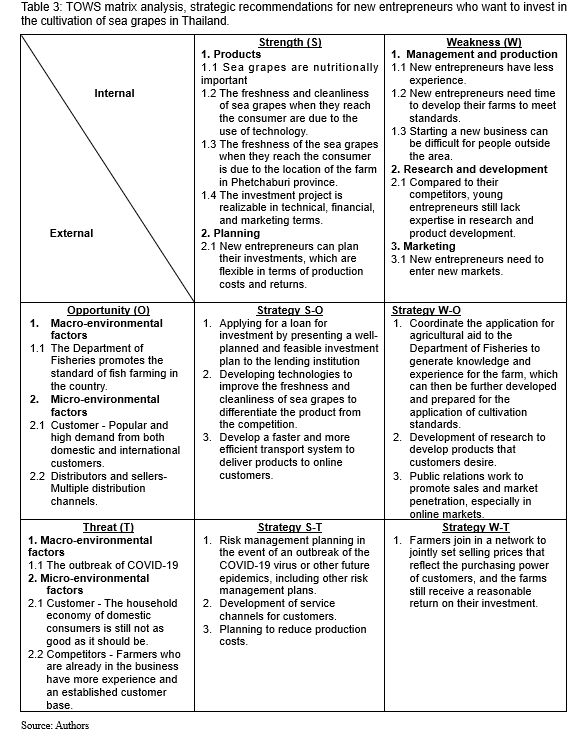

Based on the SWOT analysis above, the weakness factors will be addressed in a strategy to overcome the weakness of the sea grape cultivation business in the TOWS analysis matrix (Table 3). The TOWS matrix analysis for the preparation of strategic proposals for new entrepreneurs interested in investing in commercial sea grape cultivation results in the following ten strategic proposals:

Strategy S-O (Strengths-Opportunities)

- Applying for a loan for investment by presenting a well-planned and feasible investment plan to the lending institution.

- Developing technologies to improve the freshness and cleanliness of sea grapes to create products that stand out from the competition.

- Development of a faster and more efficient transport system for the delivery of products to online customers.

Strategy W-O (Weakness-Opportunities)

- Coordination to apply to the Ministry of Fisheries for the promotion of seaweed farming to create knowledge and experience for the farms, which can then be further developed and prepared for the application of the GAP 7434(G)-2562 standards.

- Expanding research to develop sea grape products that are in demand by customers.

- Public relations, sales promotion, and market penetration, especially online marketing.

Strategy S-T (Strengths-Threats)

- Risk management planning in the event of a COVID-19 outbreak or other future epidemics, including other risk management plans.

- Developing service channels for customers.

- Planning to reduce production costs.

Strategy W-T (Weakness-Threats)

- Farmers join in a network to jointly set a selling price that is appropriate to the purchasing power of customers, and the farm can still make a worthwhile profit.

New farmers or entrepreneurs interested in this investment project can use the results of the study and the strategic recommendations to plan their future investments in sea grape cultivation.

CONCLUSION

Seaweed farming has a major advantage over other marine products. The plants can be harvested throughout the year. Only during the rainy season, when the salt content is low, does production decline. In many Thai provinces, seaweed cultivation has thrived, especially the cultivation of sea grapes, which can provide farmers with additional income. Therefore, seaweed farming in Thailand holds promise for a promising future that not only increases the community's profit but also improves the environment's quality. The study on the feasibility of investing in the commercial cultivation of sea grapes in both earthen ponds and cages has shown that it is financially feasible, except in the case of selling all produce for THB100/kg (approximately US$3.05/kg), which results in a loss. The strategic conclusion of this study is that, following the SWOT analysis, ten strategic suggestions can be made for a new entrepreneur considering investment in sea grape cultivation. However, this is only a preliminary study. Further systematic and comprehensive studies should be conducted on the demand, utilization, marketing, and distribution channels of sea grapes, both domestically and internationally. In co-operation with the Department of Fisheries, studies should be carried out on the number of farmers, areas under cultivation, cultivation methods and the quantity of sea grapes produced annually, as well as on the needs and problems of farmers, both those registered with the Department of Fisheries and those not yet registered, since most of the data collected only apply to farmers who are already registered. In addition, studies should be conducted on the total value of each activity involved in cultivating the different types of sea grapes, including investment in the construction of a cultivation area (pond), fertilization, and associated costs. How do the yields and other factors differ between the different types of sea grapes? For example, in the case of sea lettuce (U. rigida), which the Department of Fisheries wants to promote as an economic sea grape.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI) and the Office of National Higher Education Science Research and Innovation Policy Council, the Program Management Unit for Competitiveness (PMU-C), No: C10F630067. We would also like to acknowledge the support of all fisheries department staff and farmers who participated in answering the questionnaire to complete the data.

REFERENCES

Belleza, D. F. C. and Liao L. M. 2007. Taxonomic inventory of the marine green algal genus at the University of San Carlos (Cebu) herbarium. Philippine Scientist 44, 71-104.

FAO. 2018a. The global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization. FAO Global research program. Vol. 124, Rome, Italy.

FAO. 2018b. FAO Aquaculture Newsletter No. 58, 6-8, April 2018.

FAO. 2021. Seaweeds and microalgae: an overview for unlocking their potential in global aquaculture development. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1229, Rome, Italy.

Fisheries Department Information and Communication Technology Center. 2022. Aquatic Animal Farmer Registration (Seaweed). Department of Fisheries. https://www4.fisheries.go.th/local/index.php/main/view_

activities/9/13164

Fishery Product Standards Certification System Development and Traceability Evidence Division. 2025. Aquaculture farm certification database management program. Department of Fisheries (DOF). Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, https://workspace.bcommart.com/seafish/index.php/announce/index/?page=1&... =3&cert_status_id=ALL&search_field=1, Retrieved on 3 June 2025. (in Thai).

Lewmanomont, K. 1998. The Seaweed Resource of Thailand. In: Critchley, A. T. and Ohno, M. (eds.), Seaweed Resources of the World. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Yokosuka, Japan. p.p. 70-78.

Lewmanomont, K., Chirapart, A. 2022. Biodiversity, Cultivation and Utilization of Seaweeds in Thailand: An Overview. In: Ranga Rao, A., Ravishankar, G.A. (eds) Sustainable Global Resources of Seaweeds. Volume 1, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91955-9_6.

Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre. 2025. Annual report of Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre, Department of Fisheries. (personal contact)

Thai Customs Department, Ministry of Finance. 2025. Statistics report. https://www.customs.go.th/statistic_report. php?lang=th&show_search=1&s=IaZpYpQcvK0zcmHH, Retrieved on 6 July 2025. (in Thai).

[1] 3.05 US$ = 100 Baht, currency exchange rate in June 2025

Sea Grape Farming in Thailand: Status and Feasibility Analysis

ABSTRACT

Thailand is a tropical country in Southeast Asia with coastlines on both the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, covering a total of 18 provinces suitable for seaweed farming. The most cultivated economic seaweed at present is sea grape (Caulerpa lentillifera), which is cultivated in many provinces using various methods. This article provides general information on seaweeds used in Thailand, especially sea grapes, including cultivation methods, basic information on the number of farms, production volumes, and income. In 2023, there are 167 sea grape farms in Thailand, covering an area of approximately 553.12 rai (88.50 hectares) and producing more than 1,340.18 tons of sea grapes annually. Phetchaburi province is one of the largest producers of sea grapes, with an estimated output of 1,084.68 tons, worth more than 42.69 million Baht (~US$1.3 million)[1]. In the past, Thailand lacked a direct standard for seaweed farming, instead relying on general aquaculture standards. However, in 2019, a standard for agricultural products, the Good Aquaculture Practice for Seaweed Farms (GAP 7434(G)-2562), was developed. Furthermore, the results of the study to evaluate and compare the feasibility of sea grape farming in earthen ponds and in cages were mentioned, which showed that both types of sea grape farming are suitable from a financial feasibility point of view, except for the sale of sea grape at US$0.35/kg, which would result in a loss. Additionally, the results of the SWOT analysis aid in formulating strategic recommendations for new entrepreneurs seeking to invest in commercial sea grape farming.

Keywords: Caulerpa lentillifera, GAP, Seaweed, Sea grape, SWOT analysis

INTRODUCTION

Thailand's coastline is approximately 3,148 km long, with 1,093 km on the west coast (Andaman Sea) and 2,055 km on the Gulf of Thailand. From sandy beaches to rocky shores and even muddy areas with dead coral fragments, everything is suitable for colonization by algae. More than 500 taxa of marine algae from Thailand have been recorded. Of these, 462 species have been identified. Many have not yet been identified or are listed as uncertain species. Of the identified species, 214 belong to the red algae, 123 to the green algae, 70 to the blue-green algae (cyanobacteria), and 55 to the brown algae (Lewmanomont and Chirapart, 2022). The use of seaweed as a food source in Thailand was initially limited to certain coastal regions. The most consumed seaweeds are Gracilaria, Porphyra, Caulerpa, Ulva, and Sargassum (Lewmanomont, 1998). They are eaten fresh, like salad vegetables, mixed with other ingredients, or added to soups. Due to changing consumer habits, numerous algae products and products containing algae extracts are now commercially available.

The domestic production of seaweed in Thailand is relatively low. However, as the country's consumption and utilization in the food and non-food sectors is high, Thailand is a net importer of seaweed and hydrocolloids. In general, Thailand imports edible seaweeds such as dried wakame, nori, agar strips, and powder for direct consumption, US$65.76 million in 2022 and US$119.36 million in 2024 (Thai Customs Department, 2025). China and the Republic of Korea are the primary sources of dried edible seaweed, with well-known brands such as Taokaenoi dominating the market. Hydrocolloids (carrageenan, agar, and alginate) are imported for the country's large food processing sector, which produces a wide range of ‘ready-to-cook and ‘ready-to-eat foods for the local and export markets. In addition to food for human consumption, Thailand has a large export-oriented animal feed industry that uses seaweed products as a binding agent (FAO, 2018a).

Due to the increasing popularity of seaweed as a healthy food, more seaweed is being cultivated for domestic consumption. This differs from the past, when seaweed was collected in the wild, and more and more people want to invest in seaweed cultivation, especially Caulerpa lentillifera, often referred to as "sea grape", because this type of seaweed has a beautiful and delicious appearance that attracts consumers. Additionally, other types of seaweed are being increasingly cultivated, such as Caulerpa corynephora, which is popular in southern Thailand. After 2014, the cultivation of sea grapes was introduced. They became popular as a healthy food option and generated additional profits for farmers.

The sea grape species C. lentillifera has been cultivated in land-based tanks in Okinawa, Japan, for many years. In the national aquaculture statistics of Japan, Vietnam, and China, cultivated sea grapes are not listed separately. Annual production in the three countries is around 600 tons, 300-400 tons, and over 1,000 tons, respectively (FAO, 2018b). The Philippines is the leading producer of sea grapes. In 2019, 1,090 tons of cultivated sea grapes were produced, excluding those collected in the wild (FAO, 2021). Commercial cultivation of sea grapes in Thailand began in 2014. Currently, there are no official reports on the actual production volumes from cultivation. Most of the data collected comes from farms registered with the Department of Fisheries, and the standards for seaweed farming were not established until 2019.

This article contains data on the cultivation of sea grape in Thailand, including utilization, basic information on the number of farms, production volumes, and income. The data are collected from current observations, primarily in Thai, along with data from our research, which includes interviews with seaweed farmers and related parties, as well as the experience of researchers who have been working with seaweed for over 20 years. In addition, the results of the study to evaluate and compare the feasibility of sea grape farming in earthen ponds and in cages, as well as the results of the SWOT analysis, on strategic recommendations for new entrepreneurs who want to invest in commercial sea grape farming.

CAULERPA UNTILIZATION IN THAILAND

Caulerpa is a green alga that is often used as a salad vegetable. As it is rich in minerals, vitamins, trace elements, and bioactive substances, it has become a popular health food in recent years. The two most popular species are C. lentilifera and C. corynephora due to their succulent texture (Fig. 1).

Caulerpa lentillifera, also known as “sea grape” or “green caviar”, has a tubular thallus that is connected without a dividing wall. It consists of horizontal stolons running parallel to the ground, which branch out upright from the ground and grow up to 10 cm high (Fig. 1A). The stolons are cylindrical, have a 1-1.5 mm diameter, and are provided with leaves or ramulus at the branches. The ramulus is spherical, translucent, densely arranged, and has a very short stem, almost connected to the axis. The ramulus has a diameter of 1-2 mm, is regularly branched, and has rhizoids that branch into fine hairs (Belleza and Liao, 2007). This species was previously used to treat wastewater from shrimp ponds. The plant's ability to absorb large concentrations of nutrients makes it a suitable candidate for the biofiltration of aquaculture effluent. It has also been found to thrive in various habitats, including ponds, and has recently been successfully cultivated for food. It is usually eaten fresh as a salad or dressed with a special Thai hot sauce (Fig. 2A-C). Sea grape is mainly cultivated in earth ponds. The retail price for this seaweed is between US$5.49-6.10/kg. The wholesale price is US$3.97-4.58/kg, depending on the quantity of each order. Most farmers sell the sea grapes in bunches. In addition, premium-grade sea grapes are also sold, i.e., sea grapes with a length of more than 3 inches (Fig. 1C). The selling price ranges from US$6.71 to 9.15/kg. The retail price during the rainy season is higher because the market produces less. The retail price for sea grapes in bunches is US$9.15/kg, while the wholesale price is US$9.15/kg, depending on the quantity of each order. During the rainy season, the retail price for premium sea grapes is US$10.68-21.35/kg. However, for several years now, there have been no orders from customers for the premium grade. Following the outbreak of COVID-19 at the end of 2019, the farm price for sea grapes has declined significantly, altering the sales model for sea grapes. Currently, many farmers sell sea grapes at retail and wholesale at the same price, with prices varying from farm to farm and depending on the quantity of sea grapes placed on the market at the time of trading. The farm price is US$3.05, 3.66, or 4.58/kg. In addition, most farms no longer categorize the quality of the algae as they used to. They now only sell the cluster quality and no longer the premium grade. A new form of sale has also been found: wholesale, where farmers wash the seaweed in the pond, then place it in a basket and weigh it for sale without sorting the quality of the seaweed and cleaning it, as is done when selling in clusters. The price for seaweed of sale from the whole pond depends on the quality of the seaweed at the time of purchase. Usually, the price for selling whole seaweed is US$1.22/kg.

Caulerpa corynephora, thallus branches sparsely from the stolons, the branching consisting of widely spaced ramifications extending to the tip of the branch (Fig. 1B). The thallus is club-shaped but with a constriction between the ramulus and the stem, 2-4 mm in diameter, opaque green, with fibrous roots that do not branch into fibrils (Belleza and Liao, 2007). This species was found growing only in the southern part of Thailand along the Andaman Sea coast, especially in Krabi, Trang, and Satun provinces. It has been consumed fresh by local people (Fig. 2D-E) and is now cultured in earth ponds and fish cages. The selling price of this seaweed is US$2.44-3.66/kg.

SEAGRAPE FARMING IN THAILAND

In the past, the cultivation of seaweed was not very popular in Thailand. Only Gracialria was accepted by the locals in the provinces of Songkhla and Pattani. In 2010, seaweed, particularly sea lettuce (Ulva rigida), was successfully cultivated for pond farming in Trat Province, followed by sea grape (C. lentillifera) in Phetchaburi Province in 2014. Currently, seaweed farming is well known in many provinces in southern Thailand, providing additional income for coastal fishermen.

Sea grape farming is popular in many provinces in southern Thailand, especially in the province of Phetchaburi, where seaweed cultivation has begun. More than 61 farms are active in this province. The farmers use the salt ponds, which no longer produce salt, and the abandoned shrimp ponds for sea grape cultivation. The Department of Fisheries is responsible for promoting and developing the commercial cultivation of seaweed through the Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre in Phetchaburi until it was successful in 2014. This center is responsible for technology transfer through training and knowledge transfer to farmers who have wanted to cultivate seaweed for over 10 years, to create additional income for the farmers.

There are three types of Caulerpa farming:

This type of cultivation can be divided into three methods: planting, sowing, and hanging a net-frame.

Sea grape is adaptable to a variety of environments, making it suitable for cultivation in earthen ponds. Regular replacement of seawater is necessary to maintain the nutrient levels and ensure good water quality, which are essential for growth. The plants can be harvested after 6 to 8 weeks. In the dry season (December-April), sowing in the earthen ponds results in a total quantity of algae that is around twelve times the quantity of all the seedlings used before sorting, i.e. around 15,000 kg/ha. After sorting for sale in bundles, 50 % of the production remains for sale, i.e., around 7,500 kg/ha. The yield of sea grapes in the rainy season (May-October) is approximately 40% lower than in the dry season, with a yield of about 60% of the dry season yield, i.e., approximately 9,000 kg/ha. The sea grape production in this season is not very nice or has a less desirable quality than in the dry season, with only 30% or about 2,700 kg/ha reaching a saleable grade.

2. Cultivation in cement ponds or tanks. Cultivation of seaweed in cement ponds, plastic tanks, or fiber tanks can be carried out in small and large tanks. The tank used for cultivation has a volume of 1-2 m³. There are 2 types of cultivation: sawing and hanging a net-frame or a basket.

2.1) Sowing: This method uses a fiberglass tank or a cement tank into which seawater is pumped into a high tank with a muddy bottom. Plant the seaweed by burying it about 3 to 5 cm deep. Use C. lentillifera seedlings harvested from the wild. Cover the tank with clear plastic to prevent rainwater from entering. Change the water every 2-3 days with natural seawater. No fertilizer is added as the seawater contains sufficient nutrients. With seaweed grown at low density, no significant growth is observed in the first week, and the algae gain approximately 3-4 kg/m²/year. The cultivation period is about 2 months.

2.2) Hanging net frame or basket: In this method, C. lentillifera is cultivated in a cement tank by hanging a net frame or using a plastic basket and placing it in the tank (Fig. 4). The initial density of C. lentillifera was 0.5 kg/m². When C. lentillifera had reached 5.2 kg/m2 and 65 % of the algae had been harvested

3.Cultivation in cages. The success of cultivating sea grapes in cages depends on selecting a suitable location, such as a fish cage at the mouth of a river. The algae can be harvested in summer when freshwater runoff is low. By adding 0.5 kg of seedlings per frame, 10 kg can be harvested per frame, i.e., approximately 20 times the number of seedlings added. After sorting, 50% of the products remain ready for sale, i.e., approximately 5 kg per frame. Of these, 2 kg are used as seedlings for the next cultivation, while the remaining 3 kg are discarded. Sea grapes can be cultured in cages all year round (about 3-4 crops/year). The biomass is 5-10 kg/m2/year. In the provinces of Satun, Trang, and Krabi, sea grapes are preferably grown in cages using the hanging frame method. The number of cages varies from 2 to 10 for small farms to more than 100 for large farms.

When comparing the cultivation methods, it was found that the sowing method resulted in a higher biomass of sea grapes than the net-frames method and that cultivation in earth ponds resulted in a higher biomass than in cement ponds or cages (Lewmanomont and Chirapart, 2022).

According to our research and information from the Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre, Department of Fisheries, there are currently 167 sea grape farms with an area of about 553.12 rai (88.50 hectares) and annual sea grape production of more than 1,340.18 tons/year (Table 1). However, the actual area under cultivation and production of sea grapes in some regions is not recorded. Therefore, the actual cultivation area and production volume are higher than stated. The area with the most sea grape farms in Thailand is Phetchaburi province. In 2023, there are 61 farms with an area of 465 rai (74.4 hectares) and an annual production volume of 1,084.68 tons, generating more than THB42.69 million (approximately US$1.30 million). It is estimated that the area under cultivation in Phetchaburi will increase by 188 rai (approximately 30.08 hectares) and the production volume will rise by around 200 tons by 2026, generating revenue of more than THB50 million (approximately US$1.53 million).

Good Aquaculture Practices for Seaweed Farms in Thailand

In the past, most seaweed with economic value was harvested from the wild. Today, due to environmental changes, the quantity and extent of natural seaweed has decreased significantly. Therefore, seaweed farming is crucial for planning the expansion of this industry. However, as there are no regulations, rules, or controls on the production process of seaweed in Thailand to produce high-quality, safe, and acceptable seaweeds for consumers, this represents an improvement in quality standards for agricultural products and increases the ability to compete in the international market. Quality issues that can occur with seaweed include inconsistent quality and cleanliness, heavy metal content, and ineffective storage methods to maintain quality over time. The quality of the seaweed obtained from farms depends on the environment in which the seaweed grows, especially the quality of the seawater used for cultivation. Based on the problems and trends in the demand for seaweed in the market, the National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards, together with the Department of Fisheries, developed the standard for agricultural products "Good Aquaculture Practices for Seaweed Farms (GAP 7434(G)-2562) " in 2019, as well as guidelines for the application of the standard, so that seaweed farmers can use it as a guide under the principles of food hygiene and safety, and so that farmers can produce seaweeds of a quality that meets market demand, thereby improving the quality standards of agricultural products and increasing competitiveness in the international market. The requirements include: 1. Farm registration, 2. Farm location, 3. General management, 4. Production factors, 5. Hygiene on the farm, 6. Harvest and post-harvest procedures before sale, 7. Social responsibility, 8. Environmental responsibility, and 9. Data collection. There are currently 26 certified seaweed farms. Of these, 23 are from Phetchaburi Province, 2 from Trang Province, and 1 from Chanthaburi Province. In addition, there are 9 farms that have applied for certification and are currently being audited (Fishery Product Standards Certification System Development and Traceability Evidence Division, 2025). Nevertheless, the number of farms that have received this standard is low compared to the total number of farms.

Feasibility analysis of seagrape farming

Currently, seaweed is being cultivated for domestic consumption, and an increasing number of people are interested in investing in seaweed farming, particularly sea grapes (C. lentillifera). There are various types and techniques of sea grape cultivation, including cultivation in earthen ponds (planting, sowing, and hanging net frames), cultivation in cages within natural water sources, and cultivation in cement ponds. These different methods of cultivation involve different costs and yields, which determine the value or non-value of each type of investment. Although seaweed cultivation is an investment opportunity that is currently attracting interest from farmers in Thailand and is being promoted by the Department of Fisheries, however, seaweed farmers still lack data on the feasibility of investing in seaweed cultivation. Market data, utilization (or demand), production volume data, and the number of seaweed farms (or supply) are essential data that can be used for investment considerations, such as whether the farms are suitable for seaweed production. For example, whether the investment is feasible in terms of production volume and number of seaweed farms (or supply), whether the investment is feasible in terms of technology, commercialization, and supply and demand, and most importantly, in terms of financing. This feasibility analysis data gives farmers who want to invest in seaweed cultivation the certainty that it is feasible in practice. It also provides guidance for selecting an efficient farming model with low costs, with yields or benefits that are worth the investment, and with which production capacity can be planned and production resources utilized for an effective investment.

Our study was conducted during 2020-2021, the farming methods currently preferred by farmers in earthen ponds and cages were selected to investigate and analyze the cost-effectiveness of commercial farming and the feasibility of seaweed farming from various aspects, including the investigation and analysis of the internal and external environment of commercial sea grape farming in the two farming methods. The data was analyzed based on the project objectives to evaluate and compare the feasibility of the two investment projects between an investment project for commercial seaweed cultivation in earth ponds in Phetchaburi province with a cultivation area of 4 rai (approximately 0.64 ha) and an investment project for commercial seaweed cultivation in cages in Krabi province with an operation of 40 cages. The period for the investment projects is 5 years. The selling price of sea grapes is fixed in three cases: THB100, 120, and 150, which correspond to the current selling price on the farm.

Comparison of investment opportunities between sea grapes in earthen ponds and cages (Table 2). From the study on the feasibility of investing in the cultivation of sea grapes, taking into account the net present value (NPV), the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) and the internal rate of return (IRR) of the project from the cultivation in earth ponds with sowing method, the total cultivation area of 4 rai at a selling price/kg of THB100, 120 and 150 and the cultivation in 40 cages at the same selling price, it was found that the investment pays off in almost all cases, except for the cage cultivation at a selling price of THB100/kg, which has a negative net present value (NPV) of (-81.057). This means that with 40 cages and a selling price of THB100/kg over a 5-year project period, there would be a loss of THB81,057 (approximately US$2,472.76). Therefore, the selling price for sea grapes from cages should not be set at THB100/ kg. When comparing the return and value of commercial cultivation of sea grapes in earthen ponds and cages, it was found that cultivation in earthen ponds produced a higher return than cultivation in cages. The highest return on investment for cultivation in earth ponds was obtained at a selling price of THB150/kg (IRR = 273%), followed by a selling price of THB120/kg (IRR = 163%). The highest return on investment for cage farming was achieved at a selling price of THB150/kg (IRR = 99%), followed by a selling price of THB120/kg (IRR = 45%).

The sensitivity analysis, which aims to determine whether the decision on financial feasibility is still acceptable or not if the investment in a sea grape cultivation, compares the change in costs (SVTC) and the change in benefit due to the change in the price of sea grape (STVB) between cultivation in earth ponds and cultivation in cages to compare the investment risk. It was found that cultivating sea grapes in earth ponds is less risky than cultivating them in cages. It was also found that the sea grape selling price of THB150/kg from earth ponds cultivation has the lowest risk compared to the other cases with a variability of cost value (SVTC) of 74.44%, which means that the cost may increase by 74.44%, while the variability of benefit value (SVTB) is 42.67% or the return may decrease by 42.67%, resulting in a loss of the project. Regarding the sale of sea grapes from cage culture, considering the above break-even point, it was determined that they should not be sold for THB100/kg, as this would result in a loss. However, considering the case of selling at prices of THB120 and 150, the selling price of THB150/kg from cage cultivation was found to be less risky, with a variability of value of cost (SVTC) of 44.63% and a variability of value of benefit (SVTB) of 30.86%. This shows that the costs can only increase by 44.63% or the return can decrease by a maximum of 30.86%, which would lead to a project loss.

SWOT ANALYSIS OF SEA GRAPE FARMING

Based on a SWOT analysis of sea grape cultivation in earthen ponds and cages as a basis for strategic proposals for commercial sea grape cultivation using the TOWS matrix, a survey was conducted by our research group (2020-2021). The SWOT analysis was created to provide information for new entrepreneurs who want to invest in sea grape cultivation in ponds or cages. The internal factor analysis (strengths and weaknesses) of the seaweed farms analyzed in this study was divided into 5 categories: (1) the product, i.e. the seaweed production or investment project, (2) management and production, (3) research and development, (4) marketing, and (5) planning. When analyzing the external factors (opportunity and threat), the analysis can be divided into two types of factors: (1) macro-environmental factors, and (2) micro-environmental factors such as customers, competitors, distributors, and vendors. The results of the comparative analysis of internal and external factors (SWOT analysis) for new entrepreneurs interested in investing in commercial sea grape cultivation projects in earthen ponds or cages are summarized as follows.

Based on the SWOT analysis above, the weakness factors will be addressed in a strategy to overcome the weakness of the sea grape cultivation business in the TOWS analysis matrix (Table 3). The TOWS matrix analysis for the preparation of strategic proposals for new entrepreneurs interested in investing in commercial sea grape cultivation results in the following ten strategic proposals:

Strategy S-O (Strengths-Opportunities)

Strategy W-O (Weakness-Opportunities)

Strategy S-T (Strengths-Threats)

Strategy W-T (Weakness-Threats)

New farmers or entrepreneurs interested in this investment project can use the results of the study and the strategic recommendations to plan their future investments in sea grape cultivation.

CONCLUSION

Seaweed farming has a major advantage over other marine products. The plants can be harvested throughout the year. Only during the rainy season, when the salt content is low, does production decline. In many Thai provinces, seaweed cultivation has thrived, especially the cultivation of sea grapes, which can provide farmers with additional income. Therefore, seaweed farming in Thailand holds promise for a promising future that not only increases the community's profit but also improves the environment's quality. The study on the feasibility of investing in the commercial cultivation of sea grapes in both earthen ponds and cages has shown that it is financially feasible, except in the case of selling all produce for THB100/kg (approximately US$3.05/kg), which results in a loss. The strategic conclusion of this study is that, following the SWOT analysis, ten strategic suggestions can be made for a new entrepreneur considering investment in sea grape cultivation. However, this is only a preliminary study. Further systematic and comprehensive studies should be conducted on the demand, utilization, marketing, and distribution channels of sea grapes, both domestically and internationally. In co-operation with the Department of Fisheries, studies should be carried out on the number of farmers, areas under cultivation, cultivation methods and the quantity of sea grapes produced annually, as well as on the needs and problems of farmers, both those registered with the Department of Fisheries and those not yet registered, since most of the data collected only apply to farmers who are already registered. In addition, studies should be conducted on the total value of each activity involved in cultivating the different types of sea grapes, including investment in the construction of a cultivation area (pond), fertilization, and associated costs. How do the yields and other factors differ between the different types of sea grapes? For example, in the case of sea lettuce (U. rigida), which the Department of Fisheries wants to promote as an economic sea grape.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute (KURDI) and the Office of National Higher Education Science Research and Innovation Policy Council, the Program Management Unit for Competitiveness (PMU-C), No: C10F630067. We would also like to acknowledge the support of all fisheries department staff and farmers who participated in answering the questionnaire to complete the data.

REFERENCES

Belleza, D. F. C. and Liao L. M. 2007. Taxonomic inventory of the marine green algal genus at the University of San Carlos (Cebu) herbarium. Philippine Scientist 44, 71-104.

FAO. 2018a. The global status of seaweed production, trade and utilization. FAO Global research program. Vol. 124, Rome, Italy.

FAO. 2018b. FAO Aquaculture Newsletter No. 58, 6-8, April 2018.

FAO. 2021. Seaweeds and microalgae: an overview for unlocking their potential in global aquaculture development. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1229, Rome, Italy.

Fisheries Department Information and Communication Technology Center. 2022. Aquatic Animal Farmer Registration (Seaweed). Department of Fisheries. https://www4.fisheries.go.th/local/index.php/main/view_

activities/9/13164

Fishery Product Standards Certification System Development and Traceability Evidence Division. 2025. Aquaculture farm certification database management program. Department of Fisheries (DOF). Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, https://workspace.bcommart.com/seafish/index.php/announce/index/?page=1&... =3&cert_status_id=ALL&search_field=1, Retrieved on 3 June 2025. (in Thai).

Lewmanomont, K. 1998. The Seaweed Resource of Thailand. In: Critchley, A. T. and Ohno, M. (eds.), Seaweed Resources of the World. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Yokosuka, Japan. p.p. 70-78.

Lewmanomont, K., Chirapart, A. 2022. Biodiversity, Cultivation and Utilization of Seaweeds in Thailand: An Overview. In: Ranga Rao, A., Ravishankar, G.A. (eds) Sustainable Global Resources of Seaweeds. Volume 1, Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91955-9_6.

Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre. 2025. Annual report of Phetchaburi Coastal Aquaculture Research and Development Centre, Department of Fisheries. (personal contact)

Thai Customs Department, Ministry of Finance. 2025. Statistics report. https://www.customs.go.th/statistic_report. php?lang=th&show_search=1&s=IaZpYpQcvK0zcmHH, Retrieved on 6 July 2025. (in Thai).

[1] 3.05 US$ = 100 Baht, currency exchange rate in June 2025