ABSTRACT

Food security has been a significant concern for many countries, including Malaysia, as it plays a crucial role in determining a nation's survival by ensuring a stable food supply for its population. Different countries define food security differently; some emphasize availability regardless of origin, resulting in non-agricultural countries like Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia having higher food security indexes than agricultural countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Malaysia faces a dilemma as it aims to reduce its dependency on increasing food imports, which reached RM78.79 (US$17.50) billion in 2023, while local producers struggle to meet demand despite increased agricultural production. The Malaysian government is continuously introducing new initiatives to balance the food supply from both local production and international sources.

Keywords: Food security dilemma, agriculture sector, production, import, government initiatives

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia remains vulnerable to the issue of food security as it continues to rely on imported food. In 2023, Malaysia imported approximately RM78.79 (US$17.50) billion worth of food products, up from RM75.62 (US$16.80) billion in the previous year. Since 2012, the value of food imports has steadily increased, despite a decline in 2018. To meet consumer needs and demands, Malaysia imports various food products, including rice, onions, dairy products, coffee, wheat flour, tea, shallots, potatoes, and cabbage. The country also heavily depends on imports of mutton and beef to satisfy domestic demand, with more than 80% of imported mutton coming from Australia and 82% of beef coming from Australia, New Zealand, and India. Live cattle are sourced from Australia, Thailand, and Indonesia, while the main suppliers of vegetables are China, Thailand, and Vietnam.

When producing countries changed their policies to reduce food exports, Malaysia was greatly affected, causing panic. Food prices skyrocketed, and food supplies dwindled as people made panic purchases. For instance, when the Indian government decided to reduce its export of white rice in 2020, the local supply in Malaysia dropped drastically. People started buying local white rice due to the significant increase in imported commodities prices. India is a crucial rice supplier for Malaysia. According to the Malaysia Trade Statistics Review 2021 by the Malaysian Statistics Department, Malaysia imported more than RM681.00 (US$151.33) million worth of rice from India in 2020, accounting for 27.5% of the country's total rice imports. Rice imports from India surged almost fivefold compared to 2019, making India the second-largest rice supplier for Malaysia after Vietnam.

In Malaysia, the government controls the price of local white rice while allowing the price of imported white rice to fluctuate. The price of local white rice is RM2.60 (US$0.58) per kilogram, and imported white rice must be sold at a higher price. As the price of imported white rice increased significantly, consumers shifted their preference to local white rice. Traders have exploited this situation by mixing local rice with imported rice and selling it at higher prices. Consequently, the supply of local white rice in the market has continuously decreased.

The same scenario applies to other products such as onions, grain corn, eggs, and temperate vegetables. When India reduced the export of small onions, the supply in Malaysia's market dropped, causing prices to increase two to three times. The scarcity of food products and higher prices heightened consumer tension and necessitated rapid government intervention. The Malaysian government swiftly allowed more imports from alternative sources to stabilize the supply.

On the other hand, the increase in imported food products has adversely affected Malaysia's agri-food industry. Local agri-preneurs struggle to compete with cheaper imported food products, rendering local products less competitive. Although agricultural production has continuously increased, it still falls short of meeting the food requirements of local consumers. The agriculture sector in Malaysia faces several challenges in sustaining food security and balancing food imports, including limited land for food crops, low productivity, climate change, and natural disasters, all of which contribute to the ongoing food security dilemma.

This paper discusses issues related to food security in Malaysia, focusing on the dilemma faced by the agri-food sector in sustaining the food supply for local consumers.

FOOD SECURITY DILEMMA

Food security measures a community's availability and ability to obtain the necessary food. The concept of food security is divided into four key components: food availability, food access, food nutritional value, and food stability. It encompasses the minimum requirements based on sufficient and available sources, ensuring both efficacy and safety, as well as a guarantee of the ability to obtain food consistently over time.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has provided four indicators for identifying food security in a country: availability of food supplies, affordability, ease of market access, and nutritious food supply. In the context of Malaysian society, food security is defined as the ability and willingness of the community to purchase quality food at reasonable prices when needed. According to Noorlidawati & Rozita (2015), as recommended by the FAO, the concept of food security is divided into four key components:

Food availability refers to households' ability to obtain sufficient food supplies of appropriate quality. This sufficient quantity and quality of food must be supplied through domestic or imported food production and food suppliers.

Food access refers to households' ability to access sufficient resources to obtain appropriate food to meet their needs. Adequacy for this access includes household production and stockpiling, purchases, gifts, loans, and food supplies.

Food consumption indicates households' ability to obtain sufficient nutrients through the amount of food consumed, access to clean water supplies, and the level of healthcare to meet good nutrition and physiological needs. This also includes household or individual knowledge of food management, processing techniques, and food preparation. This element considers the food or nutritional value supplied to consumers and the potential harm it may cause to human health.

Food stability means that every individual or household has access to sufficient food at all times. Unexpected risks that can threaten food security, such as economic crises, weather changes, and other factors, must be taken into account to ensure food stability.

Food security is crucial to ensure everyone can obtain nutritious basic food without food shortages or exorbitant prices.

Food security policies in Malaysia

At least three ministries spearhead the implementation of the food security policy in Malaysia: the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, which is responsible for food supply and availability; the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living, which oversees food affordability and price control; and the Ministry of Health, which ensures food safety and addresses the nutritional aspects of the food supply to markets.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security's role is to develop the agricultural sector. Additionally, it formulates various policies and programs to increase food production and ensure food security in the country. Since Malaysia's independence from the British in 1957, the government has introduced many agricultural policies to transform agriculture into a dynamic and progressive sector. These policies include the Five-Year Development Plan, National Transformation Programs, and National Agriculture Policies 1, 2, and 3. The Ministry has also introduced short-term initiative programs and projects.

Besides formulating policies and strategies related to the development of domestic trade, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living is responsible for determining and monitoring the prices of essential goods. This Ministry formulates the National Consumer Policy, which aims to create a harmonious environment and balance rights and responsibilities among consumers, suppliers/manufacturers, and the government. This is achieved by strengthening the legal field, trade practices, education, health, public facilities, and other related fields. The policy creates a win-win situation between product suppliers, including food, and consumers. Suppliers gain profits from their businesses, while consumers have access to and can afford to buy food for their families.

The Ministry of Health is responsible for the health system, public health, and promoting a good quality of life. Regarding food security, the Ministry aims to ensure that Malaysia's food supply is of high quality, meets nutritional standards, and is always guaranteed to be highly nutritious. The Ministry emphasizes efforts to strengthen the country's food safety by ensuring that food produced is safe and complies with established food safety standards through various strategies and interventions.

Food standards and hygiene provisions are enforced through the Food Act 1983 and its accompanying regulations, including the Food Regulations 1985 and the Food Hygiene Regulations 2009. Food operators must comply with these regulations before marketing any food product. The Ministry of Health (MOH) also collaborates with other agencies to ensure food safety control along the entire food chain, from farm to table.

Food security index

In general, the food supply in Malaysia is secure. Based on the Global Food Security ranking for 2022, Malaysia was ranked eighth among Asia-Pacific countries and second after Singapore among Southeast Asian countries. In the same year, Malaysia was ranked 41st among 133 countries globally, surpassing many agri-food exporting countries, including Thailand, Vietnam, Russia, and Ukraine. Malaysia has improved its food security index compared to ten years ago (2012). In 2022, Malaysia's score was 69.9 points, an increase of 5.7 points compared to 2012.

According to the Global Food Security Index 2022 report, Malaysia scored 53.7 points in food sustainability and ranked 57th. Malaysia scored 74.7 points in food quality and safety, indicating the government's rigorous efforts to ensure the quality and safety of food supplied to the people. Government policies and initiatives in monitoring and controlling food prices have shown promising results. Malaysia obtained a score of 87 and ranked 30th in price affordability. In other words, food is available, and consumers have access to and can afford to purchase it.

Although Malaysia has improved its food security score, its aspiration to reduce the importation of agri-food products is considered a challenge. The limited supply of agri-food products is complemented by imports, resulting in the import value of agri-food products increasing every year. This is especially true as the value of the Malaysian Ringgit depreciates annually.

Food supply

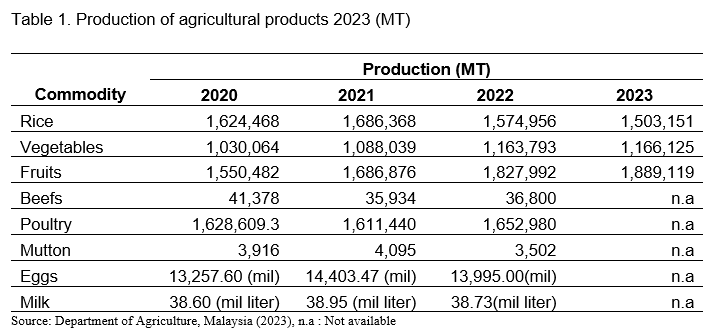

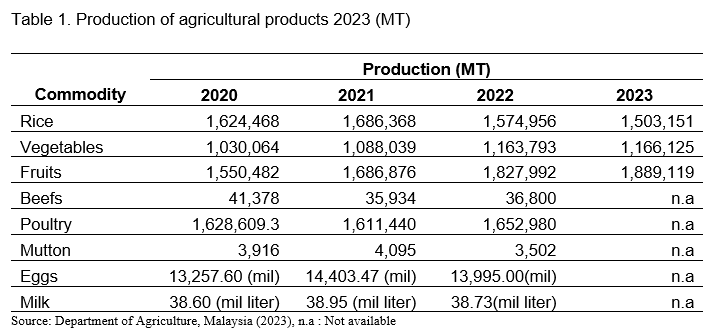

In general, Malaysia sustains its food security index through the good performance of food security elements: food availability, accessibility, affordability, and stability. The main suppliers of food in Malaysia are the agriculture sector. In 2022, the agri-food sector's significant contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) amounted to RM173.9 (US$38.64) billion, or 11.5%. This value-added production encompasses agri-food production in the agricultural, manufacturing, and services sectors. The production of agricultural products is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that agricultural food production is increasing every year. However, despite good agricultural performance, production still does not meet consumer demands. The demand for food products has grown faster than production. Health concerns have also led to increased consumption of certain agricultural foods. According to the Statistics Report by the Department of Agriculture 2024, the per capita consumption of fruits increased from 57.3 kg in 2020 to 65.90 kg in 2023, and the per capita consumption of vegetables increased from 81.80 kg to 84.90 kg during the same period. Additionally, the growing population of Malaysia, which increased from 32.45 million in 2020 to 33.40 million in 2023, has contributed to a higher total consumption of agricultural products.

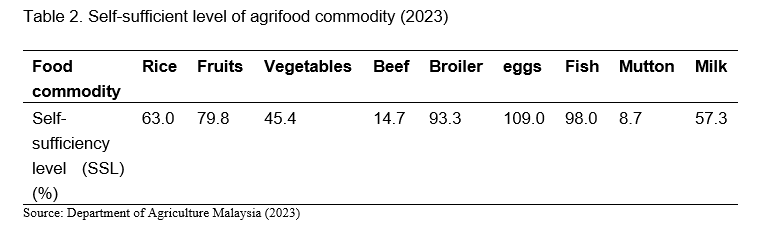

The local production of agricultural food in Malaysia cannot meet local consumers' demand. The main challenges faced by Malaysia's agriculture sector are low productivity and higher production costs. Currently, Malaysia can only produce between 14% and 70% of its food supply (Table 2).

Table 2 shows that agricultural production is insufficient to meet the total local requirements, except for eggs, which exceed local demand by 9%. The government is very concerned about the performance of livestock commodities such as beef, mutton, and milk, with local producers meeting only about 15%, 9%, and 60% of the local needs, respectively. Similar concerns apply to rice production, the most subsidized commodity in Malaysia. Despite significant government funding, the performance of this industry remains inadequate. In 2023, the government allocated RM1.6 (US$0.35) billion to continue distributing various subsidies and incentives, including production inputs (seeds, fertilizers, and chemicals), mechanization, and paddy prices (floor price).

Malaysia's performance in food production is also affected by the limited areas of land available for food production. In 2020, more than 7.6 million hectares of arable land were used for agricultural activities. However, over 5.2 million hectares were dedicated to industrial crops such as oil palms and rubber. Generally, investing in industrial crops, especially oil palms, is more profitable than investing in agri-food. As a result, farmers prefer to use arable land for these commodities.

Around 996,950 hectares were used for agri-food activities in Malaysia, with 373,783 hectares dedicated to paddy cultivation, 153,206 hectares for fruits, 64,220 hectares for vegetables, and 344,310 hectares for other food crops. The limited areas for agri-food crops resulted in a small quantity of food products. In comparison, Vietnam allocated over 33 million hectares for paddy, Thailand 9.2 million hectares, Indonesia 10.6 million hectares, and the Philippines 5.6 million hectares. Vietnam produces over 181.5 million metric tons (MT) of rice, while Indonesia produces 54.6 MT, Thailand 32.2 MT, and the Philippines 19.6 MT. On the other hand, Malaysia can only produce around 2.91 MT of rice annually, far behind those countries.

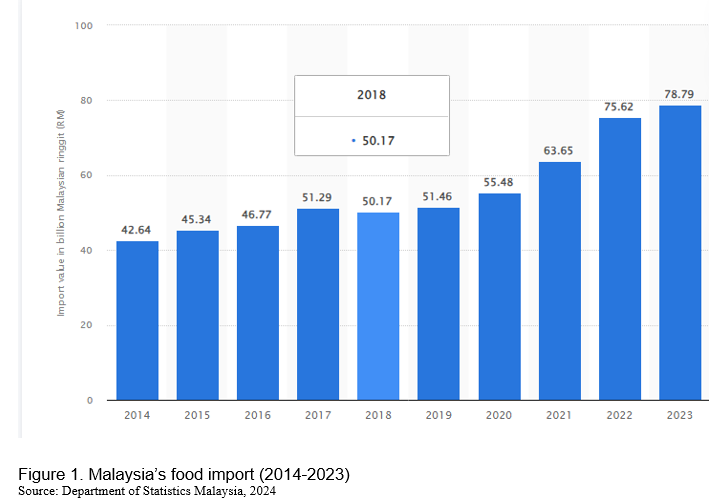

Malaysia has to supplement its food deficit by importing food products. In general, Malaysia's food imports have doubled within ten years, from RM42.64 (US$9.47) billion in 2014 to RM78.80 (US$17.51) billion in 2023 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2024), as shown in Figure 1. Malaysia's food trade witnessed a remarkable surge in 2023, increasing nearly RM30.00 (US$6.67) billion in five years (2019-2023) (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2023). China dominated the leading countries of origin for Malaysia's food products in 2022, with imports valued at RM8.70 (US$1.93) billion (11.5% of food imports), followed by Argentina at RM7.90 (US$1.75) billion and Thailand at RM7.00 (US$1.56) billion.

The increase in food imports is an attempt to ensure that food is always available and affordable for most consumers. Importing food is also a strategy used to control prices in domestic markets. The government allows the importation of food products when prices increase. For example, the price of chicken in farms throughout Peninsular Malaysia increased from November 2023 to February 2024. The average price of standard chicken in February 2023 rose to RM10.50 (US$2.30) per kilogram compared to RM9.50 (US$2.10) in February 2022. In response to this price fluctuation, the government decided to abolish the Approved Permit (AP) for chicken (whole chickens and their cuts) to enable faster supply by more local companies without the AP. The government also abolished the import permit for round cabbage, coconut, and fresh milk. This incentive has stabilized the supply and price of these commodities.

Despite improved availability, accessibility, and affordability of food in the country, Malaysia is still facing several major issues in food security that require immediate attention:

1. Dependence on imports: Malaysia still relies on imports to meet specific food needs, making the country vulnerable to global price fluctuations and supply disruptions.

2. Price instability: Food prices are unstable, especially for essential commodities such as rice, animal feed, and cooking oil. The prices of most foods that the government does not control fluctuate easily. Currently, the government controls the prices of many food products, including rice, chicken, eggs, sugar, cooking oil, flour, and meat. The government sets ceiling prices for food, especially during religious festivals, to ensure affordability for most consumers.

3. Limited domestic production: Despite efforts to increase domestic agricultural production, Malaysia still faces challenges in improving the productivity and sustainability of the agricultural sector. The agri-food sector competes with other sectors, such as manufacturing and industrial crops, which offer better land use opportunities.

4. Food safety assurance: Food safety is crucial, especially in ensuring that food produced and imported is free from contamination and safe to eat. This requires strict supervision and compliance with food safety standards.

5. Limited availability and accessibility: Although Malaysia has a good score in food affordability, food availability and accessibility are still issues, especially in rural areas and for low-income groups.

Considering that the food supply is secure in Malaysia, balancing local production with importing food products remains a significant dilemma. The government has invested heavily in developing agricultural infrastructures, such as dams and farm roads, provided subsidies and incentives to motivate farmers to remain in the industry, and trained youth to replace older farmers. However, the performance of the agriculture sector, especially the agri-food subsector, has been lacking. Nevertheless, the government remains committed and will continue its efforts to transform this sector.

WAY FORWARD

Under the leadership of Anwar Ibrahim, the 10th Prime Minister of Malaysia, the government is addressing the food security issue with renewed vigor. One of the fundamental steps is transforming the Agriculture Ministry into the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security to better tackle the challenges ahead.

To make the national food security agenda successful, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security has formulated a Food Security Policy Action Plan 2021-2030. This plan aims to strengthen the country's food security by addressing issues and challenges along the entire food supply chain, from agricultural inputs to food waste. The National Food Security Policy Action Plan (DSMN Action Plan) 2021-2030 includes five cores, 15 strategies, and 96 initiatives. It is expected to ensure the continuity of the country's food supply at all times, especially in the face of unexpected situations.

Besides this Food Security Policy Action Plan, the Ministry also has outlined five main directions as follows:

1. Empowering the aquaculture industry can reduce the country's dependence on fish resources obtained through captured fisheries. Currently, aquaculture contributes between 20% and 26% of fish production, compared to 80% from coastal and deep-sea fishing activities. The government aims to increase fish yield from aquaculture activities to 60%, reducing pressure on natural water resources and increasing income through the aquaculture industry. Aquaculture fish farming is carried out using cages in rivers, coastal and abandoned lakes. The government provides various incentives such as grants, fish seedlings and equipment to help fishermen increase production

2. Expanding cattle breeding in feedlots is expected to increase the self-sufficiency rate to 50% by 2030 significantly. The development of mega feedlots is a key strategy in this plan. Additionally, the Ministry plans to establish a new entity to administer and monitor the development of the ruminant industry.

3. The cultivation of grain corn targets the production of 600,000 metric tons of animal feed within the next 10 years. The Ministry has produced a National Grain Maize Industry Blueprint, aiming to reduce dependence on imports of grain corn by up to 30% by 2030. Currently, Malaysia imports almost 100% of its grain corn, or two million tons per year, from countries like Argentina, Brazil, and the US. This initiative is projected to reduce the price of animal feeds and, as a result, enhance the ruminant industry.

4. Enhancing youth participation in the agri-food sector and smart agriculture aims to overcome the issue of foreign worker dependency and aging farmers. The Ministry needs to attract the youth by applying modern agricultural technology and strengthening agricultural R&D. The agri-food sector provides opportunities and broad business prospects for young people to get involved in one of the country's most important sectors. Youth are the leading group open to accepting modern and smart agricultural technology in line with IR4.0.

5. Enhancing R&D&C in the agri-food sector is one of the final initiatives by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security to ensure the sustainability of food security.

As agricultural land is limited and has to compete with other sectors such as manufacturing, housing, or even industrial crops, farmers need to grow more food on the same land with fewer inputs. Thus, the application of innovation and technology is a must. Innovation is critical to building resilient crops and is key to transforming agri-food production.

Small-scale and older farmers dominate Malaysia's agricultural sector. More than 90% of farmers own small plots of land, with an average age of 60. The average farm size in Malaysia is 2.5 hectares per person. Therefore, farmers prefer small and simple technologies that are financially viable and easy to adopt. They also prefer technology that can be shared to reduce maintenance costs and aspire to use technology provided by service providers due to a lack of knowledge or skills to operate it themselves.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security introduced a new concept called PINTAR, which can be translated as the SMART System. The National Innovation Program for Food Security (PINTAR) is being implemented to ensure increased productivity in the country's agri-food sector.

PINTAR is vital in ensuring the sustainability of the country's agri-food sector aligns with current needs, especially in facing the complex geopolitical and economic situation and the challenges of climate change. It emphasizes innovation and re-engineering in all agri-food sector value chain aspects. The PINTAR concept is a game changer in the Ministry of Agriculture's efforts to reform the agri-food sector. PINTAR will emphasize five main strategies: i) the development of industrial capacity and infrastructure, ii) institutional and governance reforms, iii) research, development, commercialization, and innovation (R&D&C&I), iv) mechanization and automation technology, and v) the expansion of cooperation networks based on the concepts of the whole government, whole of approach, and food diplomacy. All five strategic pillars of PINTAR are critical indicators for developing, expanding, and strengthening the country's agri-food sector, including crops, livestock, fisheries, and agri-based industries along the production and value chain.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture, Malaysia (2024). Food Crop Statistics 2024. Department of Agriculture Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Department of Veterinary Services, Malaysia (2023). Livestock Statistics 2023. Department of Veterinary Services, Putrajaya.

Department of Statistics Malaysia (2023). Agrofood statistic 2023. Department of Statistics, Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Noorlidawati A.B and Rozita M.Y. (2015) Food Security in Malaysia: Perspectives of Industry Players. Economic and Technology Management Review, Vol 10a. MARDI.

Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2021). National Agrofood Policy 2021-2030. Putrajaya.

Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, 2024. PINTAR 30: Merefomasi Agromakan Negara (PINTAR30: Refomation the National Agrofood). Unpublished paper.

Zaeidah Mohamed Esa, Prakash Santhanam, Jefiena Jaafar, Zaemah Zainuddin. (2023). Feeding the Future: Achieving Food Security in Malaysia Through Trade Mechanism. Journal of Agribusiness Marketing. V11, Issue 2.

Food Security Dilemma in Malaysia

ABSTRACT

Food security has been a significant concern for many countries, including Malaysia, as it plays a crucial role in determining a nation's survival by ensuring a stable food supply for its population. Different countries define food security differently; some emphasize availability regardless of origin, resulting in non-agricultural countries like Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia having higher food security indexes than agricultural countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Malaysia faces a dilemma as it aims to reduce its dependency on increasing food imports, which reached RM78.79 (US$17.50) billion in 2023, while local producers struggle to meet demand despite increased agricultural production. The Malaysian government is continuously introducing new initiatives to balance the food supply from both local production and international sources.

Keywords: Food security dilemma, agriculture sector, production, import, government initiatives

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia remains vulnerable to the issue of food security as it continues to rely on imported food. In 2023, Malaysia imported approximately RM78.79 (US$17.50) billion worth of food products, up from RM75.62 (US$16.80) billion in the previous year. Since 2012, the value of food imports has steadily increased, despite a decline in 2018. To meet consumer needs and demands, Malaysia imports various food products, including rice, onions, dairy products, coffee, wheat flour, tea, shallots, potatoes, and cabbage. The country also heavily depends on imports of mutton and beef to satisfy domestic demand, with more than 80% of imported mutton coming from Australia and 82% of beef coming from Australia, New Zealand, and India. Live cattle are sourced from Australia, Thailand, and Indonesia, while the main suppliers of vegetables are China, Thailand, and Vietnam.

When producing countries changed their policies to reduce food exports, Malaysia was greatly affected, causing panic. Food prices skyrocketed, and food supplies dwindled as people made panic purchases. For instance, when the Indian government decided to reduce its export of white rice in 2020, the local supply in Malaysia dropped drastically. People started buying local white rice due to the significant increase in imported commodities prices. India is a crucial rice supplier for Malaysia. According to the Malaysia Trade Statistics Review 2021 by the Malaysian Statistics Department, Malaysia imported more than RM681.00 (US$151.33) million worth of rice from India in 2020, accounting for 27.5% of the country's total rice imports. Rice imports from India surged almost fivefold compared to 2019, making India the second-largest rice supplier for Malaysia after Vietnam.

In Malaysia, the government controls the price of local white rice while allowing the price of imported white rice to fluctuate. The price of local white rice is RM2.60 (US$0.58) per kilogram, and imported white rice must be sold at a higher price. As the price of imported white rice increased significantly, consumers shifted their preference to local white rice. Traders have exploited this situation by mixing local rice with imported rice and selling it at higher prices. Consequently, the supply of local white rice in the market has continuously decreased.

The same scenario applies to other products such as onions, grain corn, eggs, and temperate vegetables. When India reduced the export of small onions, the supply in Malaysia's market dropped, causing prices to increase two to three times. The scarcity of food products and higher prices heightened consumer tension and necessitated rapid government intervention. The Malaysian government swiftly allowed more imports from alternative sources to stabilize the supply.

On the other hand, the increase in imported food products has adversely affected Malaysia's agri-food industry. Local agri-preneurs struggle to compete with cheaper imported food products, rendering local products less competitive. Although agricultural production has continuously increased, it still falls short of meeting the food requirements of local consumers. The agriculture sector in Malaysia faces several challenges in sustaining food security and balancing food imports, including limited land for food crops, low productivity, climate change, and natural disasters, all of which contribute to the ongoing food security dilemma.

This paper discusses issues related to food security in Malaysia, focusing on the dilemma faced by the agri-food sector in sustaining the food supply for local consumers.

FOOD SECURITY DILEMMA

Food security measures a community's availability and ability to obtain the necessary food. The concept of food security is divided into four key components: food availability, food access, food nutritional value, and food stability. It encompasses the minimum requirements based on sufficient and available sources, ensuring both efficacy and safety, as well as a guarantee of the ability to obtain food consistently over time.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has provided four indicators for identifying food security in a country: availability of food supplies, affordability, ease of market access, and nutritious food supply. In the context of Malaysian society, food security is defined as the ability and willingness of the community to purchase quality food at reasonable prices when needed. According to Noorlidawati & Rozita (2015), as recommended by the FAO, the concept of food security is divided into four key components:

Food availability refers to households' ability to obtain sufficient food supplies of appropriate quality. This sufficient quantity and quality of food must be supplied through domestic or imported food production and food suppliers.

Food access refers to households' ability to access sufficient resources to obtain appropriate food to meet their needs. Adequacy for this access includes household production and stockpiling, purchases, gifts, loans, and food supplies.

Food consumption indicates households' ability to obtain sufficient nutrients through the amount of food consumed, access to clean water supplies, and the level of healthcare to meet good nutrition and physiological needs. This also includes household or individual knowledge of food management, processing techniques, and food preparation. This element considers the food or nutritional value supplied to consumers and the potential harm it may cause to human health.

Food stability means that every individual or household has access to sufficient food at all times. Unexpected risks that can threaten food security, such as economic crises, weather changes, and other factors, must be taken into account to ensure food stability.

Food security is crucial to ensure everyone can obtain nutritious basic food without food shortages or exorbitant prices.

Food security policies in Malaysia

At least three ministries spearhead the implementation of the food security policy in Malaysia: the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, which is responsible for food supply and availability; the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living, which oversees food affordability and price control; and the Ministry of Health, which ensures food safety and addresses the nutritional aspects of the food supply to markets.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security's role is to develop the agricultural sector. Additionally, it formulates various policies and programs to increase food production and ensure food security in the country. Since Malaysia's independence from the British in 1957, the government has introduced many agricultural policies to transform agriculture into a dynamic and progressive sector. These policies include the Five-Year Development Plan, National Transformation Programs, and National Agriculture Policies 1, 2, and 3. The Ministry has also introduced short-term initiative programs and projects.

Besides formulating policies and strategies related to the development of domestic trade, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living is responsible for determining and monitoring the prices of essential goods. This Ministry formulates the National Consumer Policy, which aims to create a harmonious environment and balance rights and responsibilities among consumers, suppliers/manufacturers, and the government. This is achieved by strengthening the legal field, trade practices, education, health, public facilities, and other related fields. The policy creates a win-win situation between product suppliers, including food, and consumers. Suppliers gain profits from their businesses, while consumers have access to and can afford to buy food for their families.

The Ministry of Health is responsible for the health system, public health, and promoting a good quality of life. Regarding food security, the Ministry aims to ensure that Malaysia's food supply is of high quality, meets nutritional standards, and is always guaranteed to be highly nutritious. The Ministry emphasizes efforts to strengthen the country's food safety by ensuring that food produced is safe and complies with established food safety standards through various strategies and interventions.

Food standards and hygiene provisions are enforced through the Food Act 1983 and its accompanying regulations, including the Food Regulations 1985 and the Food Hygiene Regulations 2009. Food operators must comply with these regulations before marketing any food product. The Ministry of Health (MOH) also collaborates with other agencies to ensure food safety control along the entire food chain, from farm to table.

Food security index

In general, the food supply in Malaysia is secure. Based on the Global Food Security ranking for 2022, Malaysia was ranked eighth among Asia-Pacific countries and second after Singapore among Southeast Asian countries. In the same year, Malaysia was ranked 41st among 133 countries globally, surpassing many agri-food exporting countries, including Thailand, Vietnam, Russia, and Ukraine. Malaysia has improved its food security index compared to ten years ago (2012). In 2022, Malaysia's score was 69.9 points, an increase of 5.7 points compared to 2012.

According to the Global Food Security Index 2022 report, Malaysia scored 53.7 points in food sustainability and ranked 57th. Malaysia scored 74.7 points in food quality and safety, indicating the government's rigorous efforts to ensure the quality and safety of food supplied to the people. Government policies and initiatives in monitoring and controlling food prices have shown promising results. Malaysia obtained a score of 87 and ranked 30th in price affordability. In other words, food is available, and consumers have access to and can afford to purchase it.

Although Malaysia has improved its food security score, its aspiration to reduce the importation of agri-food products is considered a challenge. The limited supply of agri-food products is complemented by imports, resulting in the import value of agri-food products increasing every year. This is especially true as the value of the Malaysian Ringgit depreciates annually.

Food supply

In general, Malaysia sustains its food security index through the good performance of food security elements: food availability, accessibility, affordability, and stability. The main suppliers of food in Malaysia are the agriculture sector. In 2022, the agri-food sector's significant contribution to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) amounted to RM173.9 (US$38.64) billion, or 11.5%. This value-added production encompasses agri-food production in the agricultural, manufacturing, and services sectors. The production of agricultural products is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that agricultural food production is increasing every year. However, despite good agricultural performance, production still does not meet consumer demands. The demand for food products has grown faster than production. Health concerns have also led to increased consumption of certain agricultural foods. According to the Statistics Report by the Department of Agriculture 2024, the per capita consumption of fruits increased from 57.3 kg in 2020 to 65.90 kg in 2023, and the per capita consumption of vegetables increased from 81.80 kg to 84.90 kg during the same period. Additionally, the growing population of Malaysia, which increased from 32.45 million in 2020 to 33.40 million in 2023, has contributed to a higher total consumption of agricultural products.

The local production of agricultural food in Malaysia cannot meet local consumers' demand. The main challenges faced by Malaysia's agriculture sector are low productivity and higher production costs. Currently, Malaysia can only produce between 14% and 70% of its food supply (Table 2).

Table 2 shows that agricultural production is insufficient to meet the total local requirements, except for eggs, which exceed local demand by 9%. The government is very concerned about the performance of livestock commodities such as beef, mutton, and milk, with local producers meeting only about 15%, 9%, and 60% of the local needs, respectively. Similar concerns apply to rice production, the most subsidized commodity in Malaysia. Despite significant government funding, the performance of this industry remains inadequate. In 2023, the government allocated RM1.6 (US$0.35) billion to continue distributing various subsidies and incentives, including production inputs (seeds, fertilizers, and chemicals), mechanization, and paddy prices (floor price).

Malaysia's performance in food production is also affected by the limited areas of land available for food production. In 2020, more than 7.6 million hectares of arable land were used for agricultural activities. However, over 5.2 million hectares were dedicated to industrial crops such as oil palms and rubber. Generally, investing in industrial crops, especially oil palms, is more profitable than investing in agri-food. As a result, farmers prefer to use arable land for these commodities.

Around 996,950 hectares were used for agri-food activities in Malaysia, with 373,783 hectares dedicated to paddy cultivation, 153,206 hectares for fruits, 64,220 hectares for vegetables, and 344,310 hectares for other food crops. The limited areas for agri-food crops resulted in a small quantity of food products. In comparison, Vietnam allocated over 33 million hectares for paddy, Thailand 9.2 million hectares, Indonesia 10.6 million hectares, and the Philippines 5.6 million hectares. Vietnam produces over 181.5 million metric tons (MT) of rice, while Indonesia produces 54.6 MT, Thailand 32.2 MT, and the Philippines 19.6 MT. On the other hand, Malaysia can only produce around 2.91 MT of rice annually, far behind those countries.

Malaysia has to supplement its food deficit by importing food products. In general, Malaysia's food imports have doubled within ten years, from RM42.64 (US$9.47) billion in 2014 to RM78.80 (US$17.51) billion in 2023 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2024), as shown in Figure 1. Malaysia's food trade witnessed a remarkable surge in 2023, increasing nearly RM30.00 (US$6.67) billion in five years (2019-2023) (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2023). China dominated the leading countries of origin for Malaysia's food products in 2022, with imports valued at RM8.70 (US$1.93) billion (11.5% of food imports), followed by Argentina at RM7.90 (US$1.75) billion and Thailand at RM7.00 (US$1.56) billion.

The increase in food imports is an attempt to ensure that food is always available and affordable for most consumers. Importing food is also a strategy used to control prices in domestic markets. The government allows the importation of food products when prices increase. For example, the price of chicken in farms throughout Peninsular Malaysia increased from November 2023 to February 2024. The average price of standard chicken in February 2023 rose to RM10.50 (US$2.30) per kilogram compared to RM9.50 (US$2.10) in February 2022. In response to this price fluctuation, the government decided to abolish the Approved Permit (AP) for chicken (whole chickens and their cuts) to enable faster supply by more local companies without the AP. The government also abolished the import permit for round cabbage, coconut, and fresh milk. This incentive has stabilized the supply and price of these commodities.

Despite improved availability, accessibility, and affordability of food in the country, Malaysia is still facing several major issues in food security that require immediate attention:

1. Dependence on imports: Malaysia still relies on imports to meet specific food needs, making the country vulnerable to global price fluctuations and supply disruptions.

2. Price instability: Food prices are unstable, especially for essential commodities such as rice, animal feed, and cooking oil. The prices of most foods that the government does not control fluctuate easily. Currently, the government controls the prices of many food products, including rice, chicken, eggs, sugar, cooking oil, flour, and meat. The government sets ceiling prices for food, especially during religious festivals, to ensure affordability for most consumers.

3. Limited domestic production: Despite efforts to increase domestic agricultural production, Malaysia still faces challenges in improving the productivity and sustainability of the agricultural sector. The agri-food sector competes with other sectors, such as manufacturing and industrial crops, which offer better land use opportunities.

4. Food safety assurance: Food safety is crucial, especially in ensuring that food produced and imported is free from contamination and safe to eat. This requires strict supervision and compliance with food safety standards.

5. Limited availability and accessibility: Although Malaysia has a good score in food affordability, food availability and accessibility are still issues, especially in rural areas and for low-income groups.

Considering that the food supply is secure in Malaysia, balancing local production with importing food products remains a significant dilemma. The government has invested heavily in developing agricultural infrastructures, such as dams and farm roads, provided subsidies and incentives to motivate farmers to remain in the industry, and trained youth to replace older farmers. However, the performance of the agriculture sector, especially the agri-food subsector, has been lacking. Nevertheless, the government remains committed and will continue its efforts to transform this sector.

WAY FORWARD

Under the leadership of Anwar Ibrahim, the 10th Prime Minister of Malaysia, the government is addressing the food security issue with renewed vigor. One of the fundamental steps is transforming the Agriculture Ministry into the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security to better tackle the challenges ahead.

To make the national food security agenda successful, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security has formulated a Food Security Policy Action Plan 2021-2030. This plan aims to strengthen the country's food security by addressing issues and challenges along the entire food supply chain, from agricultural inputs to food waste. The National Food Security Policy Action Plan (DSMN Action Plan) 2021-2030 includes five cores, 15 strategies, and 96 initiatives. It is expected to ensure the continuity of the country's food supply at all times, especially in the face of unexpected situations.

Besides this Food Security Policy Action Plan, the Ministry also has outlined five main directions as follows:

1. Empowering the aquaculture industry can reduce the country's dependence on fish resources obtained through captured fisheries. Currently, aquaculture contributes between 20% and 26% of fish production, compared to 80% from coastal and deep-sea fishing activities. The government aims to increase fish yield from aquaculture activities to 60%, reducing pressure on natural water resources and increasing income through the aquaculture industry. Aquaculture fish farming is carried out using cages in rivers, coastal and abandoned lakes. The government provides various incentives such as grants, fish seedlings and equipment to help fishermen increase production

2. Expanding cattle breeding in feedlots is expected to increase the self-sufficiency rate to 50% by 2030 significantly. The development of mega feedlots is a key strategy in this plan. Additionally, the Ministry plans to establish a new entity to administer and monitor the development of the ruminant industry.

3. The cultivation of grain corn targets the production of 600,000 metric tons of animal feed within the next 10 years. The Ministry has produced a National Grain Maize Industry Blueprint, aiming to reduce dependence on imports of grain corn by up to 30% by 2030. Currently, Malaysia imports almost 100% of its grain corn, or two million tons per year, from countries like Argentina, Brazil, and the US. This initiative is projected to reduce the price of animal feeds and, as a result, enhance the ruminant industry.

4. Enhancing youth participation in the agri-food sector and smart agriculture aims to overcome the issue of foreign worker dependency and aging farmers. The Ministry needs to attract the youth by applying modern agricultural technology and strengthening agricultural R&D. The agri-food sector provides opportunities and broad business prospects for young people to get involved in one of the country's most important sectors. Youth are the leading group open to accepting modern and smart agricultural technology in line with IR4.0.

5. Enhancing R&D&C in the agri-food sector is one of the final initiatives by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security to ensure the sustainability of food security.

As agricultural land is limited and has to compete with other sectors such as manufacturing, housing, or even industrial crops, farmers need to grow more food on the same land with fewer inputs. Thus, the application of innovation and technology is a must. Innovation is critical to building resilient crops and is key to transforming agri-food production.

Small-scale and older farmers dominate Malaysia's agricultural sector. More than 90% of farmers own small plots of land, with an average age of 60. The average farm size in Malaysia is 2.5 hectares per person. Therefore, farmers prefer small and simple technologies that are financially viable and easy to adopt. They also prefer technology that can be shared to reduce maintenance costs and aspire to use technology provided by service providers due to a lack of knowledge or skills to operate it themselves.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security introduced a new concept called PINTAR, which can be translated as the SMART System. The National Innovation Program for Food Security (PINTAR) is being implemented to ensure increased productivity in the country's agri-food sector.

PINTAR is vital in ensuring the sustainability of the country's agri-food sector aligns with current needs, especially in facing the complex geopolitical and economic situation and the challenges of climate change. It emphasizes innovation and re-engineering in all agri-food sector value chain aspects. The PINTAR concept is a game changer in the Ministry of Agriculture's efforts to reform the agri-food sector. PINTAR will emphasize five main strategies: i) the development of industrial capacity and infrastructure, ii) institutional and governance reforms, iii) research, development, commercialization, and innovation (R&D&C&I), iv) mechanization and automation technology, and v) the expansion of cooperation networks based on the concepts of the whole government, whole of approach, and food diplomacy. All five strategic pillars of PINTAR are critical indicators for developing, expanding, and strengthening the country's agri-food sector, including crops, livestock, fisheries, and agri-based industries along the production and value chain.

REFERENCES

Department of Agriculture, Malaysia (2024). Food Crop Statistics 2024. Department of Agriculture Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Department of Veterinary Services, Malaysia (2023). Livestock Statistics 2023. Department of Veterinary Services, Putrajaya.

Department of Statistics Malaysia (2023). Agrofood statistic 2023. Department of Statistics, Malaysia, Putrajaya.

Noorlidawati A.B and Rozita M.Y. (2015) Food Security in Malaysia: Perspectives of Industry Players. Economic and Technology Management Review, Vol 10a. MARDI.

Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2021). National Agrofood Policy 2021-2030. Putrajaya.

Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, 2024. PINTAR 30: Merefomasi Agromakan Negara (PINTAR30: Refomation the National Agrofood). Unpublished paper.

Zaeidah Mohamed Esa, Prakash Santhanam, Jefiena Jaafar, Zaemah Zainuddin. (2023). Feeding the Future: Achieving Food Security in Malaysia Through Trade Mechanism. Journal of Agribusiness Marketing. V11, Issue 2.