ABSTRACT

This study examined the importance of different determinants influencing farmer participation in the collective water management activities in the Pyawt Ywar pump irrigation project area of Myinmu Township in Myanmar. Stratified random sampling was used to collect data from the sample number of 208 irrigation beneficiaries. The level of farmers’ participation in water management activities was ranked by computing a participation index (PI) using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for individual beneficiaries. The Tobit regression model was then applied to analyze the determinants of collective participation in water management. The results revealed that participation in water management was influenced by prior experience in irrigated farming, the availability of alternative water sources, summer crop income, involvement in social organizations, and the frequency of attending water management meetings, as well as involvement in water-related conflict resolution and perceptions of farmer beneficiaries in irrigation water management.

Keywords: collective action, participation, irrigation

INTRODUCTION

Good water management is critical for developing efficient irrigated agriculture, particularly in areas subject to drought and erratic rainfall (Ashraf, Kahlown & Ashfaq, 2007). Water resource management includes planning, developing, distributing, and ensuring the optimum use of water resources.

Myanmar has extensive water resources available for irrigated agriculture, including for rice farming. Surface water from the Ayeyarwady and Sittoung River Basins has been developed for rice irrigation over the past century. However, the larger proportion of Myanmar cultivated area is rain-fed and vulnerable to unpredictable rainfall patterns as only about 16.5% of the net sown area in Myanmar in 2017 was irrigated (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018).

Moreover, the existing irrigation schemes in Myanmar are very low in efficiency (International Water Management Institute [IWMI], 2013). The larger proportion of irrigated land has provided a greater improvement in livelihoods than those depending on rainfall. As long as agriculture is largely rain-fed, irrigation has become a very crucial resource in agricultural production and livelihood improvement. There is, therefore, a need for improving irrigated agriculture to improve rural livelihoods through improving irrigation efficiency in Myanmar.

Water planning and management activities are undertaken to solve problems such as inadequate water supplies or unfair water distribution. According to Dungumaro and Madulu (2003), local communities need to be involved in assessing and solving water problems since they are the ones who interact directly with their local environment and conduct the activities that impact the environment. In connection with this community participation in irrigation water management, it is essential to ensure efficient and effective water utilization and balance the equity concerns of upstream and downstream users.

Management of irrigation systems is based on a traditional, top-down, supply-led approach aimed at maximizing rice production. There is no single law on water resources. The development and management of irrigation is still governed by the 1905 Canal Act which does not recognize the need for modern concepts such as effective participatory irrigation management, a user-oriented service delivery approach, and sustainable arrangements for cost recovery (Than, 2018).

However, farmers have little experience in managing water resources in Myanmar’s collective maintenance and management. Irrigation efficiency in Myanmar, however, is somewhat low due to the plot-to-plot irrigation practice and farmer’s participation in water management in most of the irrigated areas is relatively rare in recent history (Than, 2018). Often official management systems are inequitable, inefficient, or both and characterized by conflicts among user farmers in local level.

One way to overcome these problems is to reform water management activities by forming well-functioning water user groups, which has led to more effective irrigation management because water user groups may be able to manage water effectively (Kajisa & Dong, 2015). Users’ involvement in management decisions can build trust (Dungumaro & Madulu, 2003) and improve overall participation in water management, leading to better paths to effective conflict resolution (Jansky & Juha, 2006). Therefore, collective action in water management has been documented as a critical instrument in improving water management in various developing countries (Meinzen-Dick, Di Gregorio & McCarthy, 2004).

No previous research has investigated collective water management in Myanmar, and this study aimed to identify the critical determinants of collective participation in water management that result in better management techniques used in irrigation management in Myanmar.

METHODOLOGY

Description of the study area

This study was conducted in Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation Project (PYPIP) area, located in Myinmu Township, Sagaing Region. The Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation Project (PYPIP) is one of more than 300 pump irrigation projects constructed by the Government of Myanmar as part of its strategy to increase agricultural production, particularly of rice. The scheme draws water from the Mu River through one primary and two secondary pump stations, irrigating a range of crops including paddy (monsoon and summer), green gram, chickpea, sesame, groundnut, wheat, maize and cotton. It was constructed in 2004 with a nominal command area of 2,024 ha.

This project area comprises an irrigated area with three pump stations and three main canals. Irrigation water is taken from the Mu River. The study area has a water management committee organized by the Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department, comprising of representatives from each irrigation command area. This committee schedules the irrigation water allocation to those areas on a rotational basis. As the first pump station command area has access to irrigation water from the main canal, it has the most favorable access to irrigation water compared to the command areas serviced by the other pump stations.

In collaboration with the Irrigation and Water Utilizations Management Department (IWUMD) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI), LIFT had invested US$5 million in the Pyawt Ywar pump irrigation rehabilitation project in Myanmar’s central Dry Zone to improve livelihoods of local communities through irrigation, as well as to improve irrigation investment decisions made by the Government, development partners and the private sector. The infrastructure and agricultural technical support project is implemented by United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), and a consortium led by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and National Engineering and Planning Services (NEPS), with Welthungerhilfe (WHH) and International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT).

This project aimed to define institutional guidelines for pump based irrigation schemes in the Central Dry Zone to empower farmers and IWUMD to work together to enhance equity and efficiency in schemes, thus increasing agricultural production. This project had three main goals: 1) rehabilitate existing irrigation infrastructure; 2) facilitate the institutionalization of participatory water management; and 3) educate farmers about sustainable agriculture, water usage and high-value crops.

The study area has other non-riverine water sources, such as lakes and tube wells. Due to the irrigation scheme and these other inland water sources, multiple cropping systems have been practiced in this area, even in the summer.

Sampling design

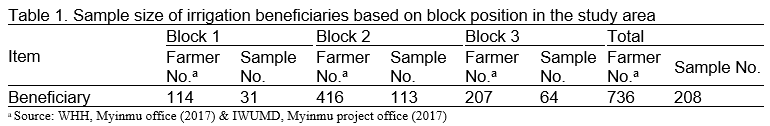

A stratified random sampling method was used to collect data from farm households in the PYPIP command area. The study area was divided into three segments (Block 1, Block 2, and Block 3) based on pump station locations to ensure a representative sample. The farmers in each block were further separated into beneficiaries (farmers who could access canal irrigation) and non-beneficiaries (farmers who could not access canal irrigation). This separation was done using the farmer list from the Myinmu Township offices of the Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department and Welthugerhilfe (WHH) of an international non-government organization. Irrigation beneficiaries were further divided into head-end, middle, and tail-end beneficiaries based on their plot locations concerning the distance from the pump station. The number of irrigation beneficiaries in the study area was made up of 736 farmers. A total of 208 beneficiaries were sampled from the three blocks with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level (Table 1).

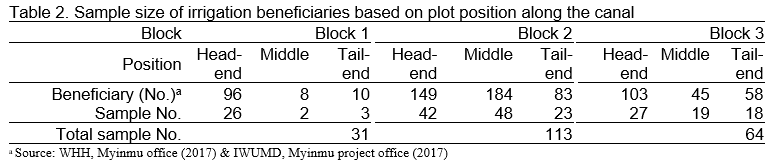

These 208 beneficiaries consisted of 3l beneficiaries from Block (1), 113 beneficiaries from Block (2), and 64 beneficiaries from Block (3) (see Table 2). Further sampling stratification was made as follows; 26 head-end, 2 middle and 3 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (l), 42 head-end, 48 middle and 23 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (2), and 27 head-end, 19 middle and 18 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (3) were again stratified. Data were collected from 208 beneficiaries of irrigation based on production activities for the 2016-2017 cropping season using a structured questionnaire.

Methods of data analysis

Participation levels in collective water management activities were ranked using a 5- point Likert scale from zero to four; The levels of participation in collective water management activities were measured by using a 5-point Likert scale from zero to four (0 = not involved, 1 = low, 2 = average, 3= high and 4 = very high) beneficiaries who had no involvement in any given activities were ranked as zero, and beneficiaries who had high levels of involvement in the given activities were ranked as four for providing a composite index of participation. The rankings were then used to compute the participation index (PI) in water management activities using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for individual beneficiaries.

Farmers’ participation in collective water management activities was weighed equally. This assumption, however, may be queried where farmers value differently the forms of contribution that are measured; for example, one farmer might value labor contribution more than financial contribution or attendance at meetings. Differences in value allocation may arise from the respondents’ different socio-economic status or the resource’s characteristics. The complexity of allocating individual-specific values to the various forms of participation has resulted in the equal weighting of the components examined in the study. This study used the participation index (PI) to measure farmers’ involvement in collective water management.

The PCA-derived composite index of participation (σ) was used as the dependent variable. Given right- and left-censoring at minimum (σ min) and maximum (σ mix) score, respectively, the 2-limit Tobit model (Maddala, 1986) was used as follows:

σi* = β0+ β1X1+ β2X2+…+ βiXi+µi

σi = σmin if σi * ≤ σmin e.i. farmer is not involved in collective activity,

σi = β’(Xi) + ui if σmin ≤ σi * ≤ σmax e.i. farmer is involved in collective activities,

σi = σmax if σi * ≥ σmax e.i. farmer is highly involved in collective activities,

Where σi* is an unobservable latent response variable, Xi is an observable vector of explanatory variables. βi is a vector of parameters to be estimated, and µi is a vector of independently and normally distributed residuals with a common variance θ.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Descriptive statistics of variables used in the model

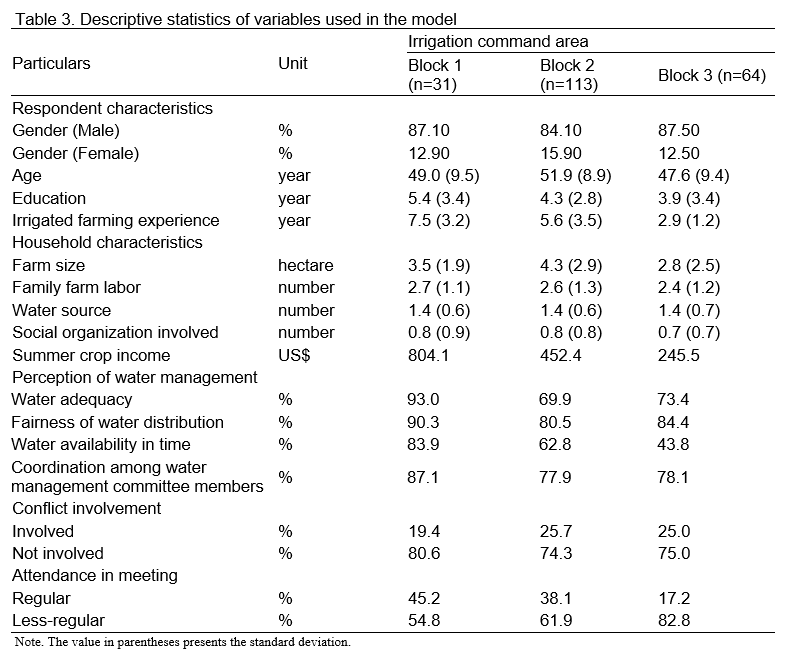

The descriptive statistics in Table 3 indicated that a large majority (84-87%) of beneficiaries (respondents) from the three blocks were male. There was little difference in the average age of beneficiaries in the three blocks, with their average age being approximately 50 years. The average number of years of school attendance of the beneficiaries from the three blocks was also reasonably uniform, ranging from 4 to 5 years. Since the block command areas were established at different times, with Block (1) first and afterward the others, there was a considerable difference in the experience of irrigation farming among farmers on the different blocks. Therefore the experience of irrigation farming (7.5 years) of beneficiaries from Block (1) was more than that of the beneficiaries from the other two blocks.

Table 3 provides a profile of the beneficiary households regarding farm household assets and social relations. Regarding land ownership, beneficiaries from Block (2) had the most significant farm size (4.3 ha), followed by beneficiaries from Block (1) (3.5 ha) and Block (3), the smallest (2.8 ha). However, the average member of farm labor employed by beneficiary households from the three blocks was similar, with an average of approximately 2.5 persons per household. The number of water sources available for crop production among the three blocks was similar (1.4 sources/farm household). Furthermore, the involvement of beneficiary households in social organizations (village development groups, social-help groups, cooperative associations, and saving and loans associations) was measured (Table 3). The average number of social organizations in which beneficiaries were involved across the three blocks was similar.

Although the beneficiary households from all blocks cultivated crops over the three seasons over the whole year (summer, monsoon, and winter), they mainly relied on canal water for crop production in summer. There was quite a difference in income from summer crops for the three blocks; beneficiaries from Block (1) earned US$ 804.1 (MMK 1,009,800), while those from Block (2) and Block (3) earned US$ 452.4 (MMK 568,100) and US$ 245.5 (MMK 308,400), respectively. As there was more favorable access to irrigation water in Block (1) compared to the other blocks, its beneficiaries earned much more from summer crop cultivation than those from the other blocks. Regarding the income of summer crops, cash crop growing positively affected the summer crop income, indicating that, for beneficiaries, cash crop (onion) growers had higher crop income than other crops growers. According to the irrigation water availability, Block (1) farmers seemed to grow cash crops than other farmers who consisted in Blocks (2) and (3).

The perceptions of the equity and efficiency of irrigation water allocation were measured using four indicators: water adequacy; fairness of water distribution; timeliness of water availability; and whether there was effective coordination among water management committee members (Table 3). With the allocation of irrigation water, a majority of beneficiaries (93%) in Block (1) received adequate irrigation water, while about 70% and 73% of beneficiaries from Block (2) and (3), respectively, received adequate irrigation. Of the three blocks, beneficiaries from Block (1) received adequate irrigation water for crop production as they could access irrigation water from the main canal, which was the first water lift in the irrigation scheme. Notably, most beneficiaries (80 to 90%) from all blocks described that water allocation was fair. In measuring the timeliness of supply, a majority of beneficiaries (63 to 84%) from Block (l) and Block (2) received irrigation water in time, while only about 44% of beneficiaries from Block (3) had that in time. For the fourth parameter, the effectiveness of coordination among the committee members, a majority of beneficiaries (78 to 87%) from all blocks agreed that the coordination activities of the committee members were practical.

In the study area, water-related conflicts arose primarily due to poor attitudes of farmers acting in their unmediated self-interest, often due to inadequate water supply. Since there was less favorable access to irrigation water in Blocks (2) and (3) in comparison to Block (1), beneficiaries from these blocks were involved much more often in water-related conflict (25%) than the beneficiaries from Block (l) (19%). The beneficiaries from Blocks (1) and (2) regularly attended water management meetings, at a regular rate of 38 to 45% compared to those from Block (3), who attended water management meetings not as often, at l7% (Table 3). This result indicates that water availability is crucial in encouraging users’ participation in meetings.

Measuring farmer participation in collective activities of water management

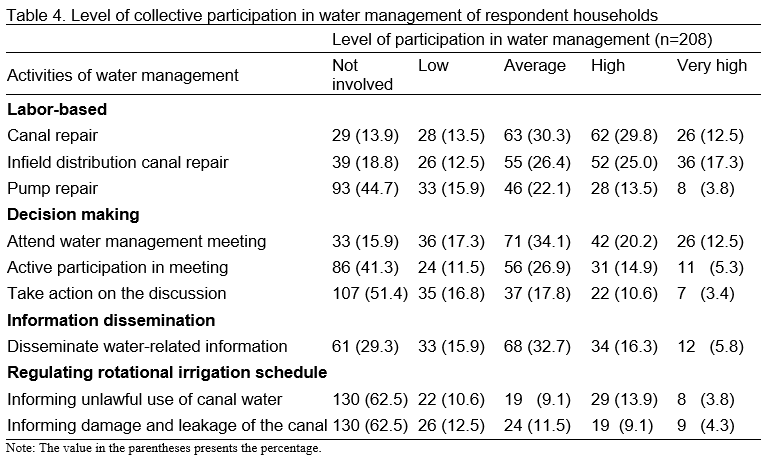

Participation of irrigation beneficiaries in activities such as the input of labor, decision-making, information dissemination, and ensuring the regulation of the rotational irrigation schedule is shown in Table 4. The beneficiaries’ participation levels in collective water management activities were measured using a nine-item, Likert-type scale to provide a composite participation index. A participation index to measure farmers’ levels of participation in water management was determined. In labor-based activities, beneficiaries participated significantly in the canal and infield-distribution-canal repair work. However, for the pump repair activity, the participation level of beneficiaries showed a marked decrease, especially in comparison with participation levels in the other types of labor-based activities. About 34% of beneficiaries participated in decision-making activities at an average level in attending water management meetings. However, approximately 41% did not actively participate in these meetings, and 5l% of the beneficiaries did not involve themselves in the actions necessary to implement by the management committee. It can be seen that although most beneficiaries participated in more than an average level in attending water management meetings, the level of participation gradually decreased when active participation in meetings was considered. There was a further decline in the commissioning of recommended actions.

In terms of information dissemination, about 33% of beneficiaries participated in an average level, but nearly 30% of beneficiaries had no involvement at all in this activity. Most beneficiaries (63%) did not have any involvement in the two activities used to measure participation levels in the regulation of the rotational irrigation schedule.

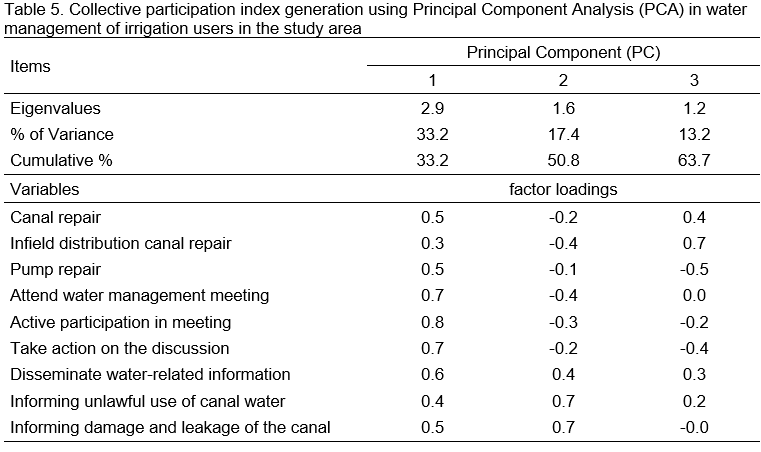

The participation index (PI) was computed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the individual beneficiary’s involvement in collective water management activities (Table 5). From the results of the PCA, the three components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained. The first component can be used alone without much loss of information because it accounts for such a large percentage of variance in the variables (Manyong, Okike & Williams, 2006). The highest explanatory power was found in the first principal component (PC-l), which explained 33.2% of the variation in participation in collective activities by beneficiaries, while the other principal components, PC-2, and PC-3, explained 17.4% and 13.2%, respectively. That is, 63.7% of the variation in the data can be explained by these three components (PCs). Only the first component (PC-l) among these three PCs provided no negative coefficients. Therefore, PC-l was retained as a value to generate the participation index because it presented the aggregate variations resulting from the differing degrees of participation. The retained first component can be used alone without much loss in information because it accounts for a large percentage of variance in the variables (Manyoung et al., 2006).

In Table 5, beneficiary farmers’ participation in the three decision-making activities dominated the first component (PC-l) (approximately 0.7) as well as activities involving water-related information dissemination (0.6). It can also be seen that farmers’ participation was relatively higher in the activities of decision-making through participating in the meeting (0.8). These same farmers have also been involved in other activities like labor-based activities, reporting damage and canal leakage, maintaining irrigation infrastructure, and preventing water loss. The success or failure of a particular activity affected the subsequent performance of the other activities, as most of the management activities in communal irrigation schemes are complementary (Fujiie, Hayami & Kikuchi, 2005). Therefore, irrigation beneficiaries must be encouraged to participate equally in all activities as a practical approach to ensure sustainable management of communal irrigation schemes.

Determinants of collective participation in water management

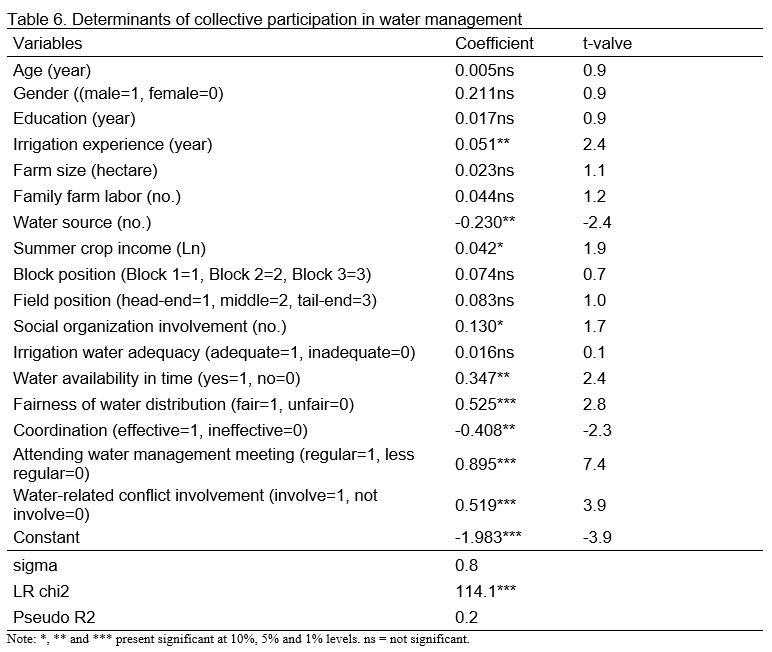

The result of the Tobit model is shown in Table 6. The dependent variable for the model was the participation index (PI), resulting from the PCA on farmer participation in water management activities.

The results showed that the experience of the respondent influenced the participation in collective water management in irrigation, the number of water sources available, summer crop income, the household’s involvement in social organizations, attendance at water management meetings as well as involvement in trying to resolve water-related conflict of beneficiary households, the perceptions of beneficiaries on the equity and efficiency of irrigation water management, timeliness of water availability, equity of water distribution, and the effectiveness of coordination among the committee members.

According to this study, irrigation experience and involvement in social organizations correlated with an increased probability of a beneficiary participating in water management. Furthermore, timeliness of water availability, attendance at water management meetings, and involvement in seeking resolution for water-related conflicts also increased the probability of participation in water management activities. The availability of other water sources also decreased the probability of participation in water management activities.

The coefficient for irrigation experience was statistically significant and positively related to the likelihood of the beneficiary being an active participant. It can be seen that the beneficiaries who had more experience in irrigated farming participated more in water management activities. The estimated coefficient reflecting the number of water sources available to the beneficiary was statistically significant and inversely related to participation levels. If a beneficiary has multiple water sources available, the probability of their participation in collective activities decreases. The coefficient for summer crop income was also statistically significant and positively related to the probability of participation. Beneficiaries who received more income from irrigated farming in summer were more willing to participate in collective water management activities than those who received less; this can directly be related to economic incentives. The coefficient obtained for involvement in social organizations was another statistically significant result and was positively related to the probability of a beneficiary’s participation in water management. Beneficiaries who frequently attended water management meetings and beneficiaries who received a timely supply of irrigation water were more likely to participate in collective water management activities.

Interestingly, effective coordination among water management committees resulted in lower participation in collective water management. This result indicates that beneficiaries, who perceived that the water management committee was influential, participated in less number of collective water management activities. Moreover, beneficiary households with more involvement in the water-related conflict were more willing to participate in collective water management activities than those with fewer problems.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

An in-depth understanding of the factors influencing farmer participation in irrigation water management is vital to form a successful irrigation management scheme. This study examined the determinants that measure farmer participation in collective water management activities in the Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation project area. Based on the Tobit regression results, this study concludes that perceptions of beneficiary farmers’ current water management practices significantly correlate with the probability of a beneficiary’s participation in collective activities. Moreover, attendance at water management meetings and involvement in resolving water-related conflicts are good indicators of involvement in collective water management. Irrigation experience positively impacts a farmer’s participation in collective water management, while the availability of other water sources exhibits an inverse relationship. The amount of income from irrigated summer crops is also positively related to farmer participation in collective activities in water management.

The study clearly shows the necessity of improving the existing collective management practices of the irrigation scheme. Local irrigation beneficiaries need to be engaged and educated in collective water management. Water-related conflicts are reduced if such programs are well designed and executed amongst the local irrigation beneficiaries. It can be seen that a critical factor in both the system’s quality and water distribution development can be achieved by promoting community participation.

It is hoped that there will be increasing farmer participation in collective water management and in reducing water-related conflicts by increasing equity and adequacy in the water distribution systems and improving infrastructure and management. The irrigation department should promote policies that remove obstacles resulting in unequal water distribution, inadequate supply, and any delays in water supply in the cropping season. The water management committee should emphasize effective coordination and decision-making with a transparent management system. Moreover, the committee should emphasize decision-making activities and take action according to the discussion. Mutual understanding and mutual respect in a rural community are the key factors because they enhance the culture of farmers’ involvement in social organization and water management. As more significant equity and efficiency are achieved, participation rates in management would be expected.

REFERENCES

Ashraf M., M. A. Kahlown & A. Ashfaq. (2007). Impact of small dams on agriculture and groundwater development: A case study from Pakistan. Agricultural Water Management, 92(1-2), 90-98.

Dungumaro E. W. & N. F. Madulu. (2003). Public participation in integrated water resources management: the case of Tanzania. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 28(20-27), 1009-1014.

Fujiie M., Y. Hayami & M. Kikuchi. (2005). The conditions of collective action for local commons management: the case of irrigation in the Philippines. Agricultural economics, 33(2), 179-189.

Jansky L. & I. Juha. (2006). Enhancing participation in water resources management. Conventional approaches and information technology. Environmental Conservation, 33(3), 274-274.

Kajisa K. & B. Dong. (2015). The Effects of Volumetric Pricing Policy on Farmers’ Water Management Institutions and Their Water Use: The Case of Water User Organization in an Irrigation System in Hubei, China. The World Bank Economic Review, 31(1), 220-240.

Maddala G. S. (1986). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics: Cambridge university press.

Manyong V. M., I. Okike & T. O. Williams. (2006). Effective dimensionality and factors affecting crop‐livestock integration in West African savannas: a combination of principal component analysis and Tobit approaches. Agricultural economics, 35(2), 145-155.

Meinzen-Dick R., M. DiGregorio & N. McCarthy. (2004). Methods for studying collective action in rural development: CAPRi working paper 33, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Than M. M. (2018). Roles and Efforts of the Irrigation Sector in Myanmar Agricultural Practice. Irrigation and drainage, 67(1), 118-122.

Determinants of Collective Participation in Water Management: A Case Study of Pyawt Ywar Irrigation Project Area, Myinmu Township in Myanmar

ABSTRACT

This study examined the importance of different determinants influencing farmer participation in the collective water management activities in the Pyawt Ywar pump irrigation project area of Myinmu Township in Myanmar. Stratified random sampling was used to collect data from the sample number of 208 irrigation beneficiaries. The level of farmers’ participation in water management activities was ranked by computing a participation index (PI) using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for individual beneficiaries. The Tobit regression model was then applied to analyze the determinants of collective participation in water management. The results revealed that participation in water management was influenced by prior experience in irrigated farming, the availability of alternative water sources, summer crop income, involvement in social organizations, and the frequency of attending water management meetings, as well as involvement in water-related conflict resolution and perceptions of farmer beneficiaries in irrigation water management.

Keywords: collective action, participation, irrigation

INTRODUCTION

Good water management is critical for developing efficient irrigated agriculture, particularly in areas subject to drought and erratic rainfall (Ashraf, Kahlown & Ashfaq, 2007). Water resource management includes planning, developing, distributing, and ensuring the optimum use of water resources.

Myanmar has extensive water resources available for irrigated agriculture, including for rice farming. Surface water from the Ayeyarwady and Sittoung River Basins has been developed for rice irrigation over the past century. However, the larger proportion of Myanmar cultivated area is rain-fed and vulnerable to unpredictable rainfall patterns as only about 16.5% of the net sown area in Myanmar in 2017 was irrigated (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation [MOALI], 2018).

Moreover, the existing irrigation schemes in Myanmar are very low in efficiency (International Water Management Institute [IWMI], 2013). The larger proportion of irrigated land has provided a greater improvement in livelihoods than those depending on rainfall. As long as agriculture is largely rain-fed, irrigation has become a very crucial resource in agricultural production and livelihood improvement. There is, therefore, a need for improving irrigated agriculture to improve rural livelihoods through improving irrigation efficiency in Myanmar.

Water planning and management activities are undertaken to solve problems such as inadequate water supplies or unfair water distribution. According to Dungumaro and Madulu (2003), local communities need to be involved in assessing and solving water problems since they are the ones who interact directly with their local environment and conduct the activities that impact the environment. In connection with this community participation in irrigation water management, it is essential to ensure efficient and effective water utilization and balance the equity concerns of upstream and downstream users.

Management of irrigation systems is based on a traditional, top-down, supply-led approach aimed at maximizing rice production. There is no single law on water resources. The development and management of irrigation is still governed by the 1905 Canal Act which does not recognize the need for modern concepts such as effective participatory irrigation management, a user-oriented service delivery approach, and sustainable arrangements for cost recovery (Than, 2018).

However, farmers have little experience in managing water resources in Myanmar’s collective maintenance and management. Irrigation efficiency in Myanmar, however, is somewhat low due to the plot-to-plot irrigation practice and farmer’s participation in water management in most of the irrigated areas is relatively rare in recent history (Than, 2018). Often official management systems are inequitable, inefficient, or both and characterized by conflicts among user farmers in local level.

One way to overcome these problems is to reform water management activities by forming well-functioning water user groups, which has led to more effective irrigation management because water user groups may be able to manage water effectively (Kajisa & Dong, 2015). Users’ involvement in management decisions can build trust (Dungumaro & Madulu, 2003) and improve overall participation in water management, leading to better paths to effective conflict resolution (Jansky & Juha, 2006). Therefore, collective action in water management has been documented as a critical instrument in improving water management in various developing countries (Meinzen-Dick, Di Gregorio & McCarthy, 2004).

No previous research has investigated collective water management in Myanmar, and this study aimed to identify the critical determinants of collective participation in water management that result in better management techniques used in irrigation management in Myanmar.

METHODOLOGY

Description of the study area

This study was conducted in Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation Project (PYPIP) area, located in Myinmu Township, Sagaing Region. The Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation Project (PYPIP) is one of more than 300 pump irrigation projects constructed by the Government of Myanmar as part of its strategy to increase agricultural production, particularly of rice. The scheme draws water from the Mu River through one primary and two secondary pump stations, irrigating a range of crops including paddy (monsoon and summer), green gram, chickpea, sesame, groundnut, wheat, maize and cotton. It was constructed in 2004 with a nominal command area of 2,024 ha.

This project area comprises an irrigated area with three pump stations and three main canals. Irrigation water is taken from the Mu River. The study area has a water management committee organized by the Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department, comprising of representatives from each irrigation command area. This committee schedules the irrigation water allocation to those areas on a rotational basis. As the first pump station command area has access to irrigation water from the main canal, it has the most favorable access to irrigation water compared to the command areas serviced by the other pump stations.

In collaboration with the Irrigation and Water Utilizations Management Department (IWUMD) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation (MOALI), LIFT had invested US$5 million in the Pyawt Ywar pump irrigation rehabilitation project in Myanmar’s central Dry Zone to improve livelihoods of local communities through irrigation, as well as to improve irrigation investment decisions made by the Government, development partners and the private sector. The infrastructure and agricultural technical support project is implemented by United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS), and a consortium led by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and National Engineering and Planning Services (NEPS), with Welthungerhilfe (WHH) and International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT).

This project aimed to define institutional guidelines for pump based irrigation schemes in the Central Dry Zone to empower farmers and IWUMD to work together to enhance equity and efficiency in schemes, thus increasing agricultural production. This project had three main goals: 1) rehabilitate existing irrigation infrastructure; 2) facilitate the institutionalization of participatory water management; and 3) educate farmers about sustainable agriculture, water usage and high-value crops.

The study area has other non-riverine water sources, such as lakes and tube wells. Due to the irrigation scheme and these other inland water sources, multiple cropping systems have been practiced in this area, even in the summer.

Sampling design

A stratified random sampling method was used to collect data from farm households in the PYPIP command area. The study area was divided into three segments (Block 1, Block 2, and Block 3) based on pump station locations to ensure a representative sample. The farmers in each block were further separated into beneficiaries (farmers who could access canal irrigation) and non-beneficiaries (farmers who could not access canal irrigation). This separation was done using the farmer list from the Myinmu Township offices of the Irrigation and Water Utilization Management Department and Welthugerhilfe (WHH) of an international non-government organization. Irrigation beneficiaries were further divided into head-end, middle, and tail-end beneficiaries based on their plot locations concerning the distance from the pump station. The number of irrigation beneficiaries in the study area was made up of 736 farmers. A total of 208 beneficiaries were sampled from the three blocks with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level (Table 1).

These 208 beneficiaries consisted of 3l beneficiaries from Block (1), 113 beneficiaries from Block (2), and 64 beneficiaries from Block (3) (see Table 2). Further sampling stratification was made as follows; 26 head-end, 2 middle and 3 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (l), 42 head-end, 48 middle and 23 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (2), and 27 head-end, 19 middle and 18 tail-end beneficiaries of Block (3) were again stratified. Data were collected from 208 beneficiaries of irrigation based on production activities for the 2016-2017 cropping season using a structured questionnaire.

Methods of data analysis

Participation levels in collective water management activities were ranked using a 5- point Likert scale from zero to four; The levels of participation in collective water management activities were measured by using a 5-point Likert scale from zero to four (0 = not involved, 1 = low, 2 = average, 3= high and 4 = very high) beneficiaries who had no involvement in any given activities were ranked as zero, and beneficiaries who had high levels of involvement in the given activities were ranked as four for providing a composite index of participation. The rankings were then used to compute the participation index (PI) in water management activities using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for individual beneficiaries.

Farmers’ participation in collective water management activities was weighed equally. This assumption, however, may be queried where farmers value differently the forms of contribution that are measured; for example, one farmer might value labor contribution more than financial contribution or attendance at meetings. Differences in value allocation may arise from the respondents’ different socio-economic status or the resource’s characteristics. The complexity of allocating individual-specific values to the various forms of participation has resulted in the equal weighting of the components examined in the study. This study used the participation index (PI) to measure farmers’ involvement in collective water management.

The PCA-derived composite index of participation (σ) was used as the dependent variable. Given right- and left-censoring at minimum (σ min) and maximum (σ mix) score, respectively, the 2-limit Tobit model (Maddala, 1986) was used as follows:

σi* = β0+ β1X1+ β2X2+…+ βiXi+µi

σi = σmin if σi * ≤ σmin e.i. farmer is not involved in collective activity,

σi = β’(Xi) + ui if σmin ≤ σi * ≤ σmax e.i. farmer is involved in collective activities,

σi = σmax if σi * ≥ σmax e.i. farmer is highly involved in collective activities,

Where σi* is an unobservable latent response variable, Xi is an observable vector of explanatory variables. βi is a vector of parameters to be estimated, and µi is a vector of independently and normally distributed residuals with a common variance θ.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Descriptive statistics of variables used in the model

The descriptive statistics in Table 3 indicated that a large majority (84-87%) of beneficiaries (respondents) from the three blocks were male. There was little difference in the average age of beneficiaries in the three blocks, with their average age being approximately 50 years. The average number of years of school attendance of the beneficiaries from the three blocks was also reasonably uniform, ranging from 4 to 5 years. Since the block command areas were established at different times, with Block (1) first and afterward the others, there was a considerable difference in the experience of irrigation farming among farmers on the different blocks. Therefore the experience of irrigation farming (7.5 years) of beneficiaries from Block (1) was more than that of the beneficiaries from the other two blocks.

Table 3 provides a profile of the beneficiary households regarding farm household assets and social relations. Regarding land ownership, beneficiaries from Block (2) had the most significant farm size (4.3 ha), followed by beneficiaries from Block (1) (3.5 ha) and Block (3), the smallest (2.8 ha). However, the average member of farm labor employed by beneficiary households from the three blocks was similar, with an average of approximately 2.5 persons per household. The number of water sources available for crop production among the three blocks was similar (1.4 sources/farm household). Furthermore, the involvement of beneficiary households in social organizations (village development groups, social-help groups, cooperative associations, and saving and loans associations) was measured (Table 3). The average number of social organizations in which beneficiaries were involved across the three blocks was similar.

Although the beneficiary households from all blocks cultivated crops over the three seasons over the whole year (summer, monsoon, and winter), they mainly relied on canal water for crop production in summer. There was quite a difference in income from summer crops for the three blocks; beneficiaries from Block (1) earned US$ 804.1 (MMK 1,009,800), while those from Block (2) and Block (3) earned US$ 452.4 (MMK 568,100) and US$ 245.5 (MMK 308,400), respectively. As there was more favorable access to irrigation water in Block (1) compared to the other blocks, its beneficiaries earned much more from summer crop cultivation than those from the other blocks. Regarding the income of summer crops, cash crop growing positively affected the summer crop income, indicating that, for beneficiaries, cash crop (onion) growers had higher crop income than other crops growers. According to the irrigation water availability, Block (1) farmers seemed to grow cash crops than other farmers who consisted in Blocks (2) and (3).

The perceptions of the equity and efficiency of irrigation water allocation were measured using four indicators: water adequacy; fairness of water distribution; timeliness of water availability; and whether there was effective coordination among water management committee members (Table 3). With the allocation of irrigation water, a majority of beneficiaries (93%) in Block (1) received adequate irrigation water, while about 70% and 73% of beneficiaries from Block (2) and (3), respectively, received adequate irrigation. Of the three blocks, beneficiaries from Block (1) received adequate irrigation water for crop production as they could access irrigation water from the main canal, which was the first water lift in the irrigation scheme. Notably, most beneficiaries (80 to 90%) from all blocks described that water allocation was fair. In measuring the timeliness of supply, a majority of beneficiaries (63 to 84%) from Block (l) and Block (2) received irrigation water in time, while only about 44% of beneficiaries from Block (3) had that in time. For the fourth parameter, the effectiveness of coordination among the committee members, a majority of beneficiaries (78 to 87%) from all blocks agreed that the coordination activities of the committee members were practical.

In the study area, water-related conflicts arose primarily due to poor attitudes of farmers acting in their unmediated self-interest, often due to inadequate water supply. Since there was less favorable access to irrigation water in Blocks (2) and (3) in comparison to Block (1), beneficiaries from these blocks were involved much more often in water-related conflict (25%) than the beneficiaries from Block (l) (19%). The beneficiaries from Blocks (1) and (2) regularly attended water management meetings, at a regular rate of 38 to 45% compared to those from Block (3), who attended water management meetings not as often, at l7% (Table 3). This result indicates that water availability is crucial in encouraging users’ participation in meetings.

Measuring farmer participation in collective activities of water management

Participation of irrigation beneficiaries in activities such as the input of labor, decision-making, information dissemination, and ensuring the regulation of the rotational irrigation schedule is shown in Table 4. The beneficiaries’ participation levels in collective water management activities were measured using a nine-item, Likert-type scale to provide a composite participation index. A participation index to measure farmers’ levels of participation in water management was determined. In labor-based activities, beneficiaries participated significantly in the canal and infield-distribution-canal repair work. However, for the pump repair activity, the participation level of beneficiaries showed a marked decrease, especially in comparison with participation levels in the other types of labor-based activities. About 34% of beneficiaries participated in decision-making activities at an average level in attending water management meetings. However, approximately 41% did not actively participate in these meetings, and 5l% of the beneficiaries did not involve themselves in the actions necessary to implement by the management committee. It can be seen that although most beneficiaries participated in more than an average level in attending water management meetings, the level of participation gradually decreased when active participation in meetings was considered. There was a further decline in the commissioning of recommended actions.

In terms of information dissemination, about 33% of beneficiaries participated in an average level, but nearly 30% of beneficiaries had no involvement at all in this activity. Most beneficiaries (63%) did not have any involvement in the two activities used to measure participation levels in the regulation of the rotational irrigation schedule.

The participation index (PI) was computed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for the individual beneficiary’s involvement in collective water management activities (Table 5). From the results of the PCA, the three components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained. The first component can be used alone without much loss of information because it accounts for such a large percentage of variance in the variables (Manyong, Okike & Williams, 2006). The highest explanatory power was found in the first principal component (PC-l), which explained 33.2% of the variation in participation in collective activities by beneficiaries, while the other principal components, PC-2, and PC-3, explained 17.4% and 13.2%, respectively. That is, 63.7% of the variation in the data can be explained by these three components (PCs). Only the first component (PC-l) among these three PCs provided no negative coefficients. Therefore, PC-l was retained as a value to generate the participation index because it presented the aggregate variations resulting from the differing degrees of participation. The retained first component can be used alone without much loss in information because it accounts for a large percentage of variance in the variables (Manyoung et al., 2006).

In Table 5, beneficiary farmers’ participation in the three decision-making activities dominated the first component (PC-l) (approximately 0.7) as well as activities involving water-related information dissemination (0.6). It can also be seen that farmers’ participation was relatively higher in the activities of decision-making through participating in the meeting (0.8). These same farmers have also been involved in other activities like labor-based activities, reporting damage and canal leakage, maintaining irrigation infrastructure, and preventing water loss. The success or failure of a particular activity affected the subsequent performance of the other activities, as most of the management activities in communal irrigation schemes are complementary (Fujiie, Hayami & Kikuchi, 2005). Therefore, irrigation beneficiaries must be encouraged to participate equally in all activities as a practical approach to ensure sustainable management of communal irrigation schemes.

Determinants of collective participation in water management

The result of the Tobit model is shown in Table 6. The dependent variable for the model was the participation index (PI), resulting from the PCA on farmer participation in water management activities.

The results showed that the experience of the respondent influenced the participation in collective water management in irrigation, the number of water sources available, summer crop income, the household’s involvement in social organizations, attendance at water management meetings as well as involvement in trying to resolve water-related conflict of beneficiary households, the perceptions of beneficiaries on the equity and efficiency of irrigation water management, timeliness of water availability, equity of water distribution, and the effectiveness of coordination among the committee members.

According to this study, irrigation experience and involvement in social organizations correlated with an increased probability of a beneficiary participating in water management. Furthermore, timeliness of water availability, attendance at water management meetings, and involvement in seeking resolution for water-related conflicts also increased the probability of participation in water management activities. The availability of other water sources also decreased the probability of participation in water management activities.

The coefficient for irrigation experience was statistically significant and positively related to the likelihood of the beneficiary being an active participant. It can be seen that the beneficiaries who had more experience in irrigated farming participated more in water management activities. The estimated coefficient reflecting the number of water sources available to the beneficiary was statistically significant and inversely related to participation levels. If a beneficiary has multiple water sources available, the probability of their participation in collective activities decreases. The coefficient for summer crop income was also statistically significant and positively related to the probability of participation. Beneficiaries who received more income from irrigated farming in summer were more willing to participate in collective water management activities than those who received less; this can directly be related to economic incentives. The coefficient obtained for involvement in social organizations was another statistically significant result and was positively related to the probability of a beneficiary’s participation in water management. Beneficiaries who frequently attended water management meetings and beneficiaries who received a timely supply of irrigation water were more likely to participate in collective water management activities.

Interestingly, effective coordination among water management committees resulted in lower participation in collective water management. This result indicates that beneficiaries, who perceived that the water management committee was influential, participated in less number of collective water management activities. Moreover, beneficiary households with more involvement in the water-related conflict were more willing to participate in collective water management activities than those with fewer problems.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

An in-depth understanding of the factors influencing farmer participation in irrigation water management is vital to form a successful irrigation management scheme. This study examined the determinants that measure farmer participation in collective water management activities in the Pyawt Ywar Pump Irrigation project area. Based on the Tobit regression results, this study concludes that perceptions of beneficiary farmers’ current water management practices significantly correlate with the probability of a beneficiary’s participation in collective activities. Moreover, attendance at water management meetings and involvement in resolving water-related conflicts are good indicators of involvement in collective water management. Irrigation experience positively impacts a farmer’s participation in collective water management, while the availability of other water sources exhibits an inverse relationship. The amount of income from irrigated summer crops is also positively related to farmer participation in collective activities in water management.

The study clearly shows the necessity of improving the existing collective management practices of the irrigation scheme. Local irrigation beneficiaries need to be engaged and educated in collective water management. Water-related conflicts are reduced if such programs are well designed and executed amongst the local irrigation beneficiaries. It can be seen that a critical factor in both the system’s quality and water distribution development can be achieved by promoting community participation.

It is hoped that there will be increasing farmer participation in collective water management and in reducing water-related conflicts by increasing equity and adequacy in the water distribution systems and improving infrastructure and management. The irrigation department should promote policies that remove obstacles resulting in unequal water distribution, inadequate supply, and any delays in water supply in the cropping season. The water management committee should emphasize effective coordination and decision-making with a transparent management system. Moreover, the committee should emphasize decision-making activities and take action according to the discussion. Mutual understanding and mutual respect in a rural community are the key factors because they enhance the culture of farmers’ involvement in social organization and water management. As more significant equity and efficiency are achieved, participation rates in management would be expected.

REFERENCES

Ashraf M., M. A. Kahlown & A. Ashfaq. (2007). Impact of small dams on agriculture and groundwater development: A case study from Pakistan. Agricultural Water Management, 92(1-2), 90-98.

Dungumaro E. W. & N. F. Madulu. (2003). Public participation in integrated water resources management: the case of Tanzania. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 28(20-27), 1009-1014.

Fujiie M., Y. Hayami & M. Kikuchi. (2005). The conditions of collective action for local commons management: the case of irrigation in the Philippines. Agricultural economics, 33(2), 179-189.

Jansky L. & I. Juha. (2006). Enhancing participation in water resources management. Conventional approaches and information technology. Environmental Conservation, 33(3), 274-274.

Kajisa K. & B. Dong. (2015). The Effects of Volumetric Pricing Policy on Farmers’ Water Management Institutions and Their Water Use: The Case of Water User Organization in an Irrigation System in Hubei, China. The World Bank Economic Review, 31(1), 220-240.

Maddala G. S. (1986). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics: Cambridge university press.

Manyong V. M., I. Okike & T. O. Williams. (2006). Effective dimensionality and factors affecting crop‐livestock integration in West African savannas: a combination of principal component analysis and Tobit approaches. Agricultural economics, 35(2), 145-155.

Meinzen-Dick R., M. DiGregorio & N. McCarthy. (2004). Methods for studying collective action in rural development: CAPRi working paper 33, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Than M. M. (2018). Roles and Efforts of the Irrigation Sector in Myanmar Agricultural Practice. Irrigation and drainage, 67(1), 118-122.