ABSTRACT

Thailand ranks sixth among the world’s top rice producers. Knowledge production has made important contributions to technological innovation in the whole supply chain of the Thai rice sector. The aim of this paper is to provide insight into the broader innovation system context in the Thai rice sector based on the sectoral innovation system framework and expand to the agenda on strengthening innovation system. This paper presents the key components of the innovation system in the rice sector, namely market demand, business domain, research domain, intermediate organizations and infrastructure and framework conditions. The knowledge flow between the public research and business domain, especially smallholder farmers, is mainly found to be in the form of extension programs that follow a linear model of knowledge transfer. The collaboration is enabled and facilitated by intermediate organizations such as government organizations and international agencies which are found to be organized and playing an active role in bridging the research and business domains. Market demand has a strong influence on the role of Thailand in domestic and global rice market. The findings in this paper help policymakers and stakeholders to understand the conditions and knowledge flows among the various domains in the Thai rice innovation system and provide policy implications to strengthen innovation system in the Thai rice sector.

Keywords: Thailand; rice; sectoral innovation system; rice research; knowledge flows

INTRODUCTION

Thailand has become an important exporter of food crops, especially rice. Each year, approximately 55% of the total production is used for domestic consumption, while the remaining 45% is exported to the world market (Titapiwatanakun, 2012). This export trend has generated a large amount of income to Thailand. In prior studies of the agriculture sector of Thailand, rice sector was recognized as a relatively innovative sector compared to other commodities (Gijsbers and van Tulder, 2011). Knowledge has made important contributions to technological innovation in rice production (Jaroensathapornkul, 2007) and food processing, and has thus affected the whole supply chain of the rice sector (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2008). It is, therefore, of particular interest to explore interactions and activities of research and key actors within the rice sector in Thailand.

The sectoral innovation system concepts are applied in different sectors to provide the insights on differential innovation dynamics across sectors in terms of the knowledge base, the actors involved in innovation, the links and relationships among actors, and the relevant institutions that shape interaction and support the emergence of innovative technologies (Malerba, 2002; Thitinunsomboon et al., 2008). In this paper, the sectoral innovation system provides understanding on the organization of knowledge flows between the domains in the rice sector innovation system in Thailand. Understandings on the innovation conditions in different domains on the sectoral innovation system in Thailand’s rice sector namely, research, business, intermediate organizations, market demand, and policy and institutional conditions can help to organize knowledge flows among the different domains in various formats.

THE CONCEPT OF SECTORAL INNOVATION SYSTEM

In this study, the concept of innovation system on a sectoral level by Malerba (2002) is applied to analyze key features composing the innovation system in Thailand’s sector. The Sectoral Innovation System (SIS) is defined as a set of new and established products for specific uses and the set of agents carrying out market and non-market interactions for the creation of production and sale of those products.

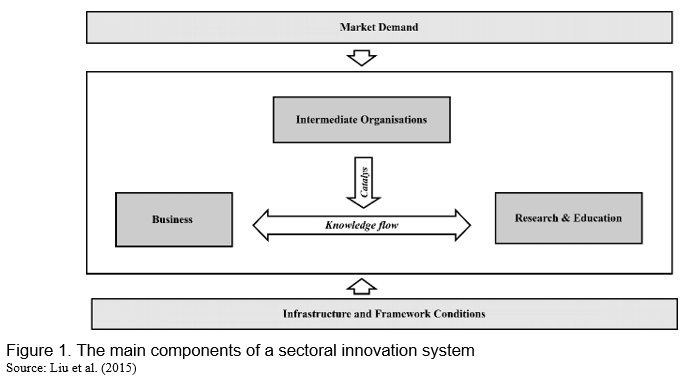

The importance of the sectoral system is that it forms the locus of intersections of numerous networks generating particular kinds of knowledge. Each of the networks has different members and different purposes but all contribute to innovation. In this study, the key features composing the sectoral innovation system (SIS) are described using the principal domains proposed in Liu et al., (2015) (Figure 1). For the analysis of the rice sector in Thailand, the key components for the flow of knowledge in the rice sector is organized among the key components: 1) the market demand referring to the demand from global market and the market prospection for rice and rice products; 2) business domain with focus on farmers, rice millers and rice manufacturer; 3) research domain with focus on the public research including public universities and public research organizations, and research units in private companies that produce and transfer knowledge and new technologies; 4) the intermediate organization that stimulates knowledge transfer between the domains; and 5) the infrastructure and framework conditions including the general views of policies, regulations and institutions related to technology development in the rice sector.

THE INNOVATION SYSTEM IN THAILAND’S RICE SECTOR

THE INNOVATION SYSTEM IN THAILAND’S RICE SECTOR

The key components in the rice sector in Thailand

The business domain

In the business domain, the three main groups of stakeholders in the Thai rice industry representing the three stages of productions in rice value chain, are farmers, millers and rice product manufacturers. Small-scale farmers that are majority of paddy farmers (OAE, 20), are often confronted with a lack of access to resources including new knowledge and technologies. Thai rice farming is facing challenges such as high cost of production, deceleration of productivity, decrease in competitiveness in the global market, plant disease outbreak and labor shortages. Apart from the factors such as the limited access to inputs such as seeds, land and water supply and low household income, the prior studies indicated that the ability of small farmers to benefit from technological change is restricted by, and limited exposure to in relation to rice production technology (Suwanmaneepong et al., 2020; Joblaew et al., 2020; Kwanmuang et al., 2020). The need to strengthen local knowledge and grassroots innovations are emphasised to respond to farmers’ challenges. Rice miller is an intermediate segment playing an important role in a value-added process for rice. Thailand’s rice mills can be classified by size into three groups: small-scale (capacity of less than 12 tons per day), medium scale (13 to 59 tons per day), and large-scale mills (over 60 tons per day) (Rerkasem, B, 2017; Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). Among the large rice mills, the use of technologies to improve production lines and to obtain the food safety standard, including GMP, ISO and HACCP standards could benefit the same commercial network as exporters (Sowcharoensuk, 2022). However, most of the rice mills that are small-scale business, are reported as inefficient and can only produce low quality rice at a relatively high production cost (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). The rice product manufacturers are processing plants for producing a wide diversity of rice products such as vermicelli, rice noodles, crackers, rice bran oil and ready-to-eat meals located in many areas in Thailand. While 91% of rice products processing plants are often using outdated equipment, only a few large factories are equipped with innovative equipment to meet export market criteria, and a few have invested in in-house R&D or collaboratively work with the public sector.

The research domain

Rice research in Thailand started officially in 1916 when the first rice research and experiment station was established under the Department of Agriculture (DoA). In 1938, the Rice Division was established under the DoA to support rice production and seed multiplication programs (DoR, 2001). The first rice breeding program in Thailand began in 1950s, with support from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (Pochanukul, 1990). This program marks the official start of the first research phase of Thailand (here called the formative phase) (FAO, 2011). Since 1980s, rice research in Thailand became more active in breeding programs (Napasintwong, 2018). Biotechnology and molecular biology applied to breeding rice for developing disease resistance and improving quality gradually increased their role in increasing rice yields (Toojinda and Lanceras-Siangliw, 2013). Rice research in Thailand has been conducted at all stages of the rice value chain by public research under the auspices of two ministries, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MoAC) (e.g., Department of Rice (DoR) and research institutes under the MoAC) and the Ministry of Higher Education Science and Innovation (e.g. public universities and public research organizations). Rice research conducted by DoR mainly concentrates on farm technologies and varietal improvement to improve farm productivity. A broad range of rice research is conducted by public universities especially those concerning new product development for both food and non-food products, postharvest technologies and varietal improvement. The public research organizations namely, the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) intend to apply cross-cutting technologies, for instance biotechnology and molecular biology for varietal improvements (Toojinda and Lanceras-siangliw, 2013). The private companies invest in in-house research towards commercialization of seeds and rice products. For rice varietal improvement research, in the past decade, there have been initiatives for hybrid rice breeding and hybrid rice seed production by multinational companies, namely Pioneer, Bayer, Syngenta, Pacific and a Thai-parent multinational company, Charoen Pokapand (CP) (FAO, 2011; Napasintuwong, 2018).

Although knowledge production and technology development are emphasized as ways to maintain the competitive advantage of Thai rice in the global market, it is relevant to note that the new integrated policy contains no specific rice research agenda (Paopongsakorn, 2019) on how to respond to changing global market conditions. The recent rice policy and strategy (2020-2024) has been developed through an integrative process between the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and the Ministry of Commerce together with relevant stakeholders including rice farmer associations, rice traders and rice millers. The rice policy focuses on: 1) strengthening farmers and farmer organizations for self-reliance and having enough income and well-being; 2) increasing the efficiency of rice production management and efficiency of competitiveness; and 3) increasing the potential of research in rice breeding and rice production technology (Buddaboon et al., 2022).

The intermediate organizations

The roles of intermediary in the system of sectoral innovation and production in the Thai rice sector have been performed in different ways. The exchange of knowledge within the research domain is often facilitated by a close interaction among research actors, for instance the public universities and public research organizations, as well as through trainings and networks. The knowledge dissemination to stakeholders in the business domain, especially farmers and small-scale millers is, mainly arranged in the classical knowledge transfer model. The flow of knowledge is still largely in the linear form starting with research at the university and public research organizations, experimental stations and extension offices, to dissemination and practical implementation such as training programs and seed distribution systems. A growing realization of increasing competitiveness in the rice sector has led to the recognition of the importance of close linkages among the key actors, and in connection with some public research organizations have changed from the linear form of the knowledge transfer towards experimentation with new approaches. The NSTDA applies the so-called triple helix model (Chaisalee et al., 2015) to provide consultation in parameters optimization, productivity improvement, loss reduction and training of workers in the local millers though its innovation and technology assistance program (ITAP) and local universities (Ministry of Science and Technology, 2016).

Co-innovation and knowledge dissemination between research organizations and/or public universities and private companies is also facilitated via cooperative research programs in which research organizations and/or public universities and private companies participate, facilitated, and granted by the government agencies such as the National Innovation Agency (NIA) (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). This is expected to result in synergies derived from coordination and coherence among the business domain, research domain and intermediate organizations. One case exemplifying novel public and private partnerships and how actors perform their intermediary roles is the GABA rice project. The GABA rice project was initiated in 2007 by the Institute of Food Research and Product Development (IFRPD) and Kasetsart University to produce partially germinating brown rice which is an excellent source of gamma–aminobutyric acid (GABA). The project was granted by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT). The added value generated by GABA rice had the potential to bring increased benefits to all stakeholders, including farmers, mill operators, manufacturers, the university and ultimately the consumers. Later, technology transfer of GABA production to the private sector partners namely, Patum Rice Mill and Granary Public Company (PRG) and Tawatchai Inter Rice Co., Ltd. (TIR) was facilitated by the NIA and the Ministry of Science and Technology (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). The intermediary roles in facilitating, participating, and managing network with actors from different domains are also performed by international agencies. For instance, the German International Cooperation (GIZ) launched the Thai Rice NAMA (Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action) project. The Thai rice NAMA project attempts to enable a shift towards low-emission rice production in Thailand through a combination of three important components of Thailand’s rice sector namely, farmers, entrepreneurs and policy and measures. The GIZ works cooperating with the DoR, Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the private companies, namely Olam group and UTZ, to promote sustainable rice farming practices for farmers by supplying information for problem-solving and responding to farmers’ needs, developing capacity building program for farmers and local government staff on sustainable rice farming practice and implementing an area-based market strategy.

Market demand of rice and rice products

In Thailand, the total area devoted to rice amounts to approximately 9.0 million hectares, producing about 20-25 million tons of milled rice per year (FAO, 2018). The main rice categories that Thailand exports are white rice, Hom mali rice and parboiled rice. White rice is the most widely traded on global markets, accounting for 55-60% of all rice on world exchanges. Hom mali rice is a high-quality, high-price product by volume accounting for 12-14% of the rice traded on global markets which Thailand is the world’s biggest exporter. Parboiled rice contributes a roughly 14-18% share of all world exports of rice (Sowcharoensuk, 2022). In 2018, the prices of premium Thai jasmine rice reached a three-year high of US$1,177 (FAO, 2018). Thailand puts efforts into maintaining a high-value added export sector for aromatic rice, which aims to further boost the country’s performance as world-leading rice exporter. However, Thailand’s rice exports in 2020 dropped to the lowest level in 10 years, as the tighter availabilities in rice stock and the strong currency reduced the competitiveness against other exporters (FAO, 2018).

Due to urbanization and changes in consumption patterns towards convenience and more health-conscious eating has resulted in Thai consumers opting for innovative products that are seen to support well-being and health. The consumption and utilization of the by-products of the rice milling process has increased, particularly using broken kernels (Triratanasirichai et al., 2017). Rice bran, rice husk, and broken rice have potential health, animal, and alternative food uses and can be profiled as waste reducing circular products. Rice bran, husk, and broken rice have a variety of applications for the mechanical, food, cosmetic, agricultural and fuel industries (Bodie et al., 2019). Pigmented rice gains attract attention among domestic and international markets given their potential to play a role in new health care products. Although nutritional values and health benefits are what consumers are concerned most when selecting pigmented rice, the standard and labelling of nutritional values of pigmented rice are not mandatory in the domestic market (Napasintuwong, 2020).

Policies, regulations and institutions related to knowledge and technology development in Thailand’s rice sector

In general, the policies related to the rice sector in Thailand mostly are translated and formulated from the national development plan. A five-year rice policy and strategy has been prepared jointly by the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and the Ministry of Commerce (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011; Paopongsakorn, 2019) to enhance rice production, promote rice export markets and solve rice problems. According to the government document, Thailand’s rice strategies are oriented to enhancing rice productivity at all stages of rice value chain, including management and development of farm production technology, postharvest and product development, improvement of marketing systems and logistics and supporting farmers’ livelihood (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). In addition, Thailand has a strategy towards adding more value to agricultural products, including rice products (e.g. noodles, crackers, rice drinks), supplement foods (e.g. oryzanol, probiotics) and consumer goods (e.g. cosmetics) (Napasintuwong, 2019). The strategy towards value adding includes the promotion of organic products in both local and export markets. In order to address environmental challenges, an organic agriculture policy in Thailand was included in the national agenda and was later set up as the National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development (NESDB, 2008; OAE, 2013). The Thai Government encourages organic rice farming practices through financial and technical support for the participating farmers. However, organic rice production in Thailand is reportedly not very successful yet due to the lack of institutional capacity, a lack of coordination and cooperation among relevant agencies, and inconsistency in policies (Lee, 2021).

The regulations related to rice research mainly focus on protecting and controlling rice germplasms and species (Napasintuwong, 2018). Thailand’s Plant Variety Act (PVA) or seed law was enacted to promote agricultural development and it regulates that all imports, exports, collections and transits of controlled seeds (including rice seeds) require a permit (Lertdhamtewe, 2015; Napasintuwong, 2018). For research purposes, rice seeds can be requested for approval by the Department of Agriculture (DOA). The intellectual property right system, including patent protection, trademarks, certification marks, and geographical indications (Tanasugarn, 1998) are mainly applied in the rice sector in the light of promoting quality of Thai rice in the market. In the rice sector, the government support technology dissemination between public and private sectors mainly via research grants (see also Chapter 3).

DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

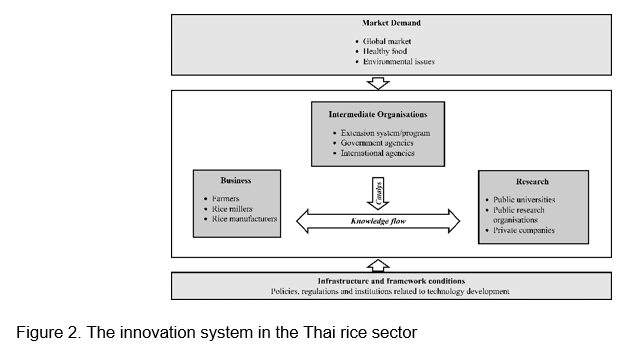

The key actors and their characteristics of each domain as derived from this analysis are mentioned in the innovation system in the Thai rice sector diagram (Figure 2).

The knowledge flow between the public research and business domain especially, smallholder farmers is mainly found to be through extension programs that follow a linear model of knowledge transfer. Collaboration in the system is enabled and facilitated by intermediate organizations such as government organizations (e.g. the NIA) and international agencies (e.g. GIZ), and these play an active role in bridging the research domain and business domain. The findings on intermediate organizations in the rice sector indicate that they perform multiple roles in knowledge and innovation intermediation (see Yang et al., 2014) to navigate the knowledge flow in the rice sector. The government agencies and international agencies play roles in facilitating stakeholder partnerships between research and rice manufacturing by identifying the potential enterprises and providing funding sources for establishing product development at the industrial scale and implementing policies and interventions to promote sustainable production in the rice sector along the rice value chain by facilitating cooperations among private companies, public research organisations and local farmers. Market demand has strong influence as rice is an important component of daily consumption patterns, and because it plays a vital role in Thailand’s socioeconomic development strategy. Global market demands are shifting towards healthy food and environmentally friendly production, and these trends have been translated to rice policies and strategies. Due to the absence of central policy and institutional mechanism to direct, support and ensure the effectiveness and cohesion of research activities in Thailand, there may remain gaps between knowledge generation at public research institutes, and the demands of the business domain and the global market.

In summary, the organization of knowledge flows among the domains in the rice sector innovation system in Thailand continues to be dominated by a linear knowledge flow from research to extension. Intermediate organization plays a limited role in promoting technological change and development through more interactive and integrated public-private partnerships.

Policy implications: Moving towards an agenda to strengthen innovation system in Thailand’s rice sector

From the sectoral system view, the generation and commercialization of innovation involve extensive cooperation and division of labor which is negotiated in networks (Malerba, 2002). Understandings the roles of domains in sectoral innovation system namely, research, business, intermediate organizations, market demand, and policy and institutional conditions can help the policy makers and stakeholders to organize knowledge flows among the different domains in various formats. The evidence from the case of rice in Thailand presents the multidimensional and dynamic nature of the sectoral system. The knowledge flow in the sector has developed with the support of government by investing in research and knowledge transfer. According to this case study, while the agendas for rice research are oriented to enhancing rice productivity at all stages of rice value chain. The knowledge flow can be supported by institutional infrastructure and conditions that support public-private partnerships, intellectual property protection, encouragement of innovation investments for the small and mid-scale firms and an emphasis on innovation that is suitable for the local’s adaptability. It is observed that in the sectoral system of Thai rice, economic policy, policies related to property rights are linked with and affect the agendas for research and technology transfer. It could imply the possibilities to enhance the synergies between each domain through the expansion of formal linkages and the creation of more coherence in research policies.

REFERENCES

Bodie, A. R., Micciche, A. C., Atungulu, G. G., Rothrock Jr, M. J., & Ricke, S. C. (2019). Current trends of rice milling by-products for agricultural applications and alternative food production systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, 47.

Buddhaboon, C., Sankum, Y., Tongnoy, S., t, A. (2022). Adaptation of Rice Production System to Climate Change in Thailand: Trend and Policy. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/3072.

Chaisalee, W., Jongkaewwattana, A., Tanticharoen, M., & Bhumiratana, S. (2010). Triple Helix System: The Heart of Innovation and Development for Rural Community in Thailand. In the 8th Triple Helix International Scientific and Organizing Committees. Spain.

Department of Rice (2011). History of Department of Rice. Bangkok, Thailand: Department of Rice. Retrieved from http://www.ricethailand.go.th web/images/pdf/history.pdf (in Thai).

FAO (2011). The dynamic tension between public and private plant breeding in Thailand. FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 208. Rome: FAO.

FAO (2018). Country fact sheet on food and agriculture policy trends. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/I8684EN/i8684en.pdf.

FAO. (2018). Rice Market Monitor XXI(1). Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3 /I9243EN /i9243en.pdf

Gijsbers, G., & Tulder, R. V. (2011). New Asian challenges: Missing linkages in Asian agricultural innovation and the role of public research organizations in four small-and-medium-sized Asian countries. Science, Technology and Society, 16(1), 29-51.]

Jaroensathapornkul, J. (2007). The Economic Impact of Public Rice Research in Thailand. Chulalongkorn Journal of Economics, 19(2), 111-134.

Joblaew, P., Sirisunyaluck, R., Kanjina, S., Chalermphol, J., & Prom–u–thai, C. (2020). Factors affecting farmers’ adoption of rice production technology from the collaborative farming project in Phrae province, Thailand. International Journal of Agricultural Technology, 15(6), 901-912.

Kwanmuang, K., Pongputhinan, T., Jabri, A., & Chitchumnung, P. (2020). Small-scale farmers under Thailand’s smart farming system. FFTC-AP, 2647.

Lee, S. (2021). In the Era of Climate Change: Moving Beyond Conventional Agriculture in Thailand. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 18(1362-2021-1176), 1-14.

Lertdhamtewe, P. (2015). Intellectual Property Law of Plant Varieties in Thailand: A Contextual Analysis. IIC-International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 46(4), 386-409.

Liu, Z., Jongsma, M. A., Huang, C., Dons, J. J. M., & Omta, S. W. F. (2015). The sectoral innovation system of the Dutch vegetable breeding industry. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 74(1), 27-39.

Malerba, F. (2002). Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Research Policy, 31(2), 247-264.

Ministry of Science and Technology. (2016) Annual Report. Ministry of Science and Technology. Retrieved from http://www.clinictech.ops.go.th/online/filemanager /fileclinic/F1/files/summaryreport2016.pdf

Napasintuwong, O. (2018). Rice breeding and R&D policies in Thailand. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from thttp://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=85

Napasintuwong, O. (2019). Rice Economy of Thailand. ARE Working Paper No. 2562/1. (January 2019). Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand

Napasintuwong, O. (2020). Thailand’s Colored Rice Standard and Markets. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from : http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=1100

NESDB. (2008). The First National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development B.E. 2551–2554 (2008–2011). Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Bangkok, Thailand.

OAE. (2013). Draft of the Second National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development B.E. 2556– 2559 (2013–2016). Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand.

Poapongsakorn, N. (2019). Overview of rice policy 2000–2018 in Thailand: A political economy analysis. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1426.

Pochanukul, P. (1990). The Development of Publicly-conducted Crop Research in Thailand. Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 28(1), 20-44.

Rerkasem, B. (2017). The rice value chain: a case study of Thai rice. Chiang Mai University Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(1), 1-26.

Sowcharoensuk, C. (2022). Industry Outlook 2022-2024: Rice Industry. Krungsri Research. Retrieved from https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/ industry-outlook/agriculture/rice/io/io-rice-2022

Suwanmaneepong, S., Kerdsriserm, C., Iyapunya, K., & Wongtragoon, U. (2020). Farmers’ adoption of organic rice production in Chachoengsao province, Thailand. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 24(2), 71-79.

Tanasugarn, L. (1998 November). Jasmine rice crisis: A Thai perspective. In Intellectual Property and International Trade Law Forum Special Issue. Bangkok: Central Intellectual Property and Trade Court.

Titapiwatanakun, B. (2012). The rice situation in Thailand. Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report (TA-REG, 74595). Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/ default/files/project-document/73082/43430-012-reg-tacr-03.pdf.

Thitinunsomboon, S., Chairatana, P. A., & Keeratipibul, S. (2008). Sectoral innovation systems in agriculture: the case of rice in Thailand. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 16(1), 83-100.

Toojinda, T., & Lanceras-Siangliw, J. (2013). Advancing Thailand’s rice Agriculture through molecular breeding. Asia-Pacific Biotech News, 17(4). 40-43.

Triratanasirichai, K., Singh, M., and Anal, A. K. (2017). Value-added byproducts from rice processing industries, in Food Processing By-Products and Their Utilization, ed A. K. Anal (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons), 277–293

An Innovation System Perspective on Strengthening Rice Sector in Thailand

ABSTRACT

Thailand ranks sixth among the world’s top rice producers. Knowledge production has made important contributions to technological innovation in the whole supply chain of the Thai rice sector. The aim of this paper is to provide insight into the broader innovation system context in the Thai rice sector based on the sectoral innovation system framework and expand to the agenda on strengthening innovation system. This paper presents the key components of the innovation system in the rice sector, namely market demand, business domain, research domain, intermediate organizations and infrastructure and framework conditions. The knowledge flow between the public research and business domain, especially smallholder farmers, is mainly found to be in the form of extension programs that follow a linear model of knowledge transfer. The collaboration is enabled and facilitated by intermediate organizations such as government organizations and international agencies which are found to be organized and playing an active role in bridging the research and business domains. Market demand has a strong influence on the role of Thailand in domestic and global rice market. The findings in this paper help policymakers and stakeholders to understand the conditions and knowledge flows among the various domains in the Thai rice innovation system and provide policy implications to strengthen innovation system in the Thai rice sector.

Keywords: Thailand; rice; sectoral innovation system; rice research; knowledge flows

INTRODUCTION

Thailand has become an important exporter of food crops, especially rice. Each year, approximately 55% of the total production is used for domestic consumption, while the remaining 45% is exported to the world market (Titapiwatanakun, 2012). This export trend has generated a large amount of income to Thailand. In prior studies of the agriculture sector of Thailand, rice sector was recognized as a relatively innovative sector compared to other commodities (Gijsbers and van Tulder, 2011). Knowledge has made important contributions to technological innovation in rice production (Jaroensathapornkul, 2007) and food processing, and has thus affected the whole supply chain of the rice sector (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2008). It is, therefore, of particular interest to explore interactions and activities of research and key actors within the rice sector in Thailand.

The sectoral innovation system concepts are applied in different sectors to provide the insights on differential innovation dynamics across sectors in terms of the knowledge base, the actors involved in innovation, the links and relationships among actors, and the relevant institutions that shape interaction and support the emergence of innovative technologies (Malerba, 2002; Thitinunsomboon et al., 2008). In this paper, the sectoral innovation system provides understanding on the organization of knowledge flows between the domains in the rice sector innovation system in Thailand. Understandings on the innovation conditions in different domains on the sectoral innovation system in Thailand’s rice sector namely, research, business, intermediate organizations, market demand, and policy and institutional conditions can help to organize knowledge flows among the different domains in various formats.

THE CONCEPT OF SECTORAL INNOVATION SYSTEM

In this study, the concept of innovation system on a sectoral level by Malerba (2002) is applied to analyze key features composing the innovation system in Thailand’s sector. The Sectoral Innovation System (SIS) is defined as a set of new and established products for specific uses and the set of agents carrying out market and non-market interactions for the creation of production and sale of those products.

The importance of the sectoral system is that it forms the locus of intersections of numerous networks generating particular kinds of knowledge. Each of the networks has different members and different purposes but all contribute to innovation. In this study, the key features composing the sectoral innovation system (SIS) are described using the principal domains proposed in Liu et al., (2015) (Figure 1). For the analysis of the rice sector in Thailand, the key components for the flow of knowledge in the rice sector is organized among the key components: 1) the market demand referring to the demand from global market and the market prospection for rice and rice products; 2) business domain with focus on farmers, rice millers and rice manufacturer; 3) research domain with focus on the public research including public universities and public research organizations, and research units in private companies that produce and transfer knowledge and new technologies; 4) the intermediate organization that stimulates knowledge transfer between the domains; and 5) the infrastructure and framework conditions including the general views of policies, regulations and institutions related to technology development in the rice sector.

The key components in the rice sector in Thailand

The business domain

In the business domain, the three main groups of stakeholders in the Thai rice industry representing the three stages of productions in rice value chain, are farmers, millers and rice product manufacturers. Small-scale farmers that are majority of paddy farmers (OAE, 20), are often confronted with a lack of access to resources including new knowledge and technologies. Thai rice farming is facing challenges such as high cost of production, deceleration of productivity, decrease in competitiveness in the global market, plant disease outbreak and labor shortages. Apart from the factors such as the limited access to inputs such as seeds, land and water supply and low household income, the prior studies indicated that the ability of small farmers to benefit from technological change is restricted by, and limited exposure to in relation to rice production technology (Suwanmaneepong et al., 2020; Joblaew et al., 2020; Kwanmuang et al., 2020). The need to strengthen local knowledge and grassroots innovations are emphasised to respond to farmers’ challenges. Rice miller is an intermediate segment playing an important role in a value-added process for rice. Thailand’s rice mills can be classified by size into three groups: small-scale (capacity of less than 12 tons per day), medium scale (13 to 59 tons per day), and large-scale mills (over 60 tons per day) (Rerkasem, B, 2017; Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). Among the large rice mills, the use of technologies to improve production lines and to obtain the food safety standard, including GMP, ISO and HACCP standards could benefit the same commercial network as exporters (Sowcharoensuk, 2022). However, most of the rice mills that are small-scale business, are reported as inefficient and can only produce low quality rice at a relatively high production cost (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). The rice product manufacturers are processing plants for producing a wide diversity of rice products such as vermicelli, rice noodles, crackers, rice bran oil and ready-to-eat meals located in many areas in Thailand. While 91% of rice products processing plants are often using outdated equipment, only a few large factories are equipped with innovative equipment to meet export market criteria, and a few have invested in in-house R&D or collaboratively work with the public sector.

The research domain

Rice research in Thailand started officially in 1916 when the first rice research and experiment station was established under the Department of Agriculture (DoA). In 1938, the Rice Division was established under the DoA to support rice production and seed multiplication programs (DoR, 2001). The first rice breeding program in Thailand began in 1950s, with support from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (Pochanukul, 1990). This program marks the official start of the first research phase of Thailand (here called the formative phase) (FAO, 2011). Since 1980s, rice research in Thailand became more active in breeding programs (Napasintwong, 2018). Biotechnology and molecular biology applied to breeding rice for developing disease resistance and improving quality gradually increased their role in increasing rice yields (Toojinda and Lanceras-Siangliw, 2013). Rice research in Thailand has been conducted at all stages of the rice value chain by public research under the auspices of two ministries, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MoAC) (e.g., Department of Rice (DoR) and research institutes under the MoAC) and the Ministry of Higher Education Science and Innovation (e.g. public universities and public research organizations). Rice research conducted by DoR mainly concentrates on farm technologies and varietal improvement to improve farm productivity. A broad range of rice research is conducted by public universities especially those concerning new product development for both food and non-food products, postharvest technologies and varietal improvement. The public research organizations namely, the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) intend to apply cross-cutting technologies, for instance biotechnology and molecular biology for varietal improvements (Toojinda and Lanceras-siangliw, 2013). The private companies invest in in-house research towards commercialization of seeds and rice products. For rice varietal improvement research, in the past decade, there have been initiatives for hybrid rice breeding and hybrid rice seed production by multinational companies, namely Pioneer, Bayer, Syngenta, Pacific and a Thai-parent multinational company, Charoen Pokapand (CP) (FAO, 2011; Napasintuwong, 2018).

Although knowledge production and technology development are emphasized as ways to maintain the competitive advantage of Thai rice in the global market, it is relevant to note that the new integrated policy contains no specific rice research agenda (Paopongsakorn, 2019) on how to respond to changing global market conditions. The recent rice policy and strategy (2020-2024) has been developed through an integrative process between the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and the Ministry of Commerce together with relevant stakeholders including rice farmer associations, rice traders and rice millers. The rice policy focuses on: 1) strengthening farmers and farmer organizations for self-reliance and having enough income and well-being; 2) increasing the efficiency of rice production management and efficiency of competitiveness; and 3) increasing the potential of research in rice breeding and rice production technology (Buddaboon et al., 2022).

The intermediate organizations

The roles of intermediary in the system of sectoral innovation and production in the Thai rice sector have been performed in different ways. The exchange of knowledge within the research domain is often facilitated by a close interaction among research actors, for instance the public universities and public research organizations, as well as through trainings and networks. The knowledge dissemination to stakeholders in the business domain, especially farmers and small-scale millers is, mainly arranged in the classical knowledge transfer model. The flow of knowledge is still largely in the linear form starting with research at the university and public research organizations, experimental stations and extension offices, to dissemination and practical implementation such as training programs and seed distribution systems. A growing realization of increasing competitiveness in the rice sector has led to the recognition of the importance of close linkages among the key actors, and in connection with some public research organizations have changed from the linear form of the knowledge transfer towards experimentation with new approaches. The NSTDA applies the so-called triple helix model (Chaisalee et al., 2015) to provide consultation in parameters optimization, productivity improvement, loss reduction and training of workers in the local millers though its innovation and technology assistance program (ITAP) and local universities (Ministry of Science and Technology, 2016).

Co-innovation and knowledge dissemination between research organizations and/or public universities and private companies is also facilitated via cooperative research programs in which research organizations and/or public universities and private companies participate, facilitated, and granted by the government agencies such as the National Innovation Agency (NIA) (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). This is expected to result in synergies derived from coordination and coherence among the business domain, research domain and intermediate organizations. One case exemplifying novel public and private partnerships and how actors perform their intermediary roles is the GABA rice project. The GABA rice project was initiated in 2007 by the Institute of Food Research and Product Development (IFRPD) and Kasetsart University to produce partially germinating brown rice which is an excellent source of gamma–aminobutyric acid (GABA). The project was granted by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT). The added value generated by GABA rice had the potential to bring increased benefits to all stakeholders, including farmers, mill operators, manufacturers, the university and ultimately the consumers. Later, technology transfer of GABA production to the private sector partners namely, Patum Rice Mill and Granary Public Company (PRG) and Tawatchai Inter Rice Co., Ltd. (TIR) was facilitated by the NIA and the Ministry of Science and Technology (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). The intermediary roles in facilitating, participating, and managing network with actors from different domains are also performed by international agencies. For instance, the German International Cooperation (GIZ) launched the Thai Rice NAMA (Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action) project. The Thai rice NAMA project attempts to enable a shift towards low-emission rice production in Thailand through a combination of three important components of Thailand’s rice sector namely, farmers, entrepreneurs and policy and measures. The GIZ works cooperating with the DoR, Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the private companies, namely Olam group and UTZ, to promote sustainable rice farming practices for farmers by supplying information for problem-solving and responding to farmers’ needs, developing capacity building program for farmers and local government staff on sustainable rice farming practice and implementing an area-based market strategy.

Market demand of rice and rice products

In Thailand, the total area devoted to rice amounts to approximately 9.0 million hectares, producing about 20-25 million tons of milled rice per year (FAO, 2018). The main rice categories that Thailand exports are white rice, Hom mali rice and parboiled rice. White rice is the most widely traded on global markets, accounting for 55-60% of all rice on world exchanges. Hom mali rice is a high-quality, high-price product by volume accounting for 12-14% of the rice traded on global markets which Thailand is the world’s biggest exporter. Parboiled rice contributes a roughly 14-18% share of all world exports of rice (Sowcharoensuk, 2022). In 2018, the prices of premium Thai jasmine rice reached a three-year high of US$1,177 (FAO, 2018). Thailand puts efforts into maintaining a high-value added export sector for aromatic rice, which aims to further boost the country’s performance as world-leading rice exporter. However, Thailand’s rice exports in 2020 dropped to the lowest level in 10 years, as the tighter availabilities in rice stock and the strong currency reduced the competitiveness against other exporters (FAO, 2018).

Due to urbanization and changes in consumption patterns towards convenience and more health-conscious eating has resulted in Thai consumers opting for innovative products that are seen to support well-being and health. The consumption and utilization of the by-products of the rice milling process has increased, particularly using broken kernels (Triratanasirichai et al., 2017). Rice bran, rice husk, and broken rice have potential health, animal, and alternative food uses and can be profiled as waste reducing circular products. Rice bran, husk, and broken rice have a variety of applications for the mechanical, food, cosmetic, agricultural and fuel industries (Bodie et al., 2019). Pigmented rice gains attract attention among domestic and international markets given their potential to play a role in new health care products. Although nutritional values and health benefits are what consumers are concerned most when selecting pigmented rice, the standard and labelling of nutritional values of pigmented rice are not mandatory in the domestic market (Napasintuwong, 2020).

Policies, regulations and institutions related to knowledge and technology development in Thailand’s rice sector

In general, the policies related to the rice sector in Thailand mostly are translated and formulated from the national development plan. A five-year rice policy and strategy has been prepared jointly by the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives and the Ministry of Commerce (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011; Paopongsakorn, 2019) to enhance rice production, promote rice export markets and solve rice problems. According to the government document, Thailand’s rice strategies are oriented to enhancing rice productivity at all stages of rice value chain, including management and development of farm production technology, postharvest and product development, improvement of marketing systems and logistics and supporting farmers’ livelihood (Thitinunsomboon et al., 2011). In addition, Thailand has a strategy towards adding more value to agricultural products, including rice products (e.g. noodles, crackers, rice drinks), supplement foods (e.g. oryzanol, probiotics) and consumer goods (e.g. cosmetics) (Napasintuwong, 2019). The strategy towards value adding includes the promotion of organic products in both local and export markets. In order to address environmental challenges, an organic agriculture policy in Thailand was included in the national agenda and was later set up as the National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development (NESDB, 2008; OAE, 2013). The Thai Government encourages organic rice farming practices through financial and technical support for the participating farmers. However, organic rice production in Thailand is reportedly not very successful yet due to the lack of institutional capacity, a lack of coordination and cooperation among relevant agencies, and inconsistency in policies (Lee, 2021).

The regulations related to rice research mainly focus on protecting and controlling rice germplasms and species (Napasintuwong, 2018). Thailand’s Plant Variety Act (PVA) or seed law was enacted to promote agricultural development and it regulates that all imports, exports, collections and transits of controlled seeds (including rice seeds) require a permit (Lertdhamtewe, 2015; Napasintuwong, 2018). For research purposes, rice seeds can be requested for approval by the Department of Agriculture (DOA). The intellectual property right system, including patent protection, trademarks, certification marks, and geographical indications (Tanasugarn, 1998) are mainly applied in the rice sector in the light of promoting quality of Thai rice in the market. In the rice sector, the government support technology dissemination between public and private sectors mainly via research grants (see also Chapter 3).

DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The key actors and their characteristics of each domain as derived from this analysis are mentioned in the innovation system in the Thai rice sector diagram (Figure 2).

The knowledge flow between the public research and business domain especially, smallholder farmers is mainly found to be through extension programs that follow a linear model of knowledge transfer. Collaboration in the system is enabled and facilitated by intermediate organizations such as government organizations (e.g. the NIA) and international agencies (e.g. GIZ), and these play an active role in bridging the research domain and business domain. The findings on intermediate organizations in the rice sector indicate that they perform multiple roles in knowledge and innovation intermediation (see Yang et al., 2014) to navigate the knowledge flow in the rice sector. The government agencies and international agencies play roles in facilitating stakeholder partnerships between research and rice manufacturing by identifying the potential enterprises and providing funding sources for establishing product development at the industrial scale and implementing policies and interventions to promote sustainable production in the rice sector along the rice value chain by facilitating cooperations among private companies, public research organisations and local farmers. Market demand has strong influence as rice is an important component of daily consumption patterns, and because it plays a vital role in Thailand’s socioeconomic development strategy. Global market demands are shifting towards healthy food and environmentally friendly production, and these trends have been translated to rice policies and strategies. Due to the absence of central policy and institutional mechanism to direct, support and ensure the effectiveness and cohesion of research activities in Thailand, there may remain gaps between knowledge generation at public research institutes, and the demands of the business domain and the global market.

In summary, the organization of knowledge flows among the domains in the rice sector innovation system in Thailand continues to be dominated by a linear knowledge flow from research to extension. Intermediate organization plays a limited role in promoting technological change and development through more interactive and integrated public-private partnerships.

Policy implications: Moving towards an agenda to strengthen innovation system in Thailand’s rice sector

From the sectoral system view, the generation and commercialization of innovation involve extensive cooperation and division of labor which is negotiated in networks (Malerba, 2002). Understandings the roles of domains in sectoral innovation system namely, research, business, intermediate organizations, market demand, and policy and institutional conditions can help the policy makers and stakeholders to organize knowledge flows among the different domains in various formats. The evidence from the case of rice in Thailand presents the multidimensional and dynamic nature of the sectoral system. The knowledge flow in the sector has developed with the support of government by investing in research and knowledge transfer. According to this case study, while the agendas for rice research are oriented to enhancing rice productivity at all stages of rice value chain. The knowledge flow can be supported by institutional infrastructure and conditions that support public-private partnerships, intellectual property protection, encouragement of innovation investments for the small and mid-scale firms and an emphasis on innovation that is suitable for the local’s adaptability. It is observed that in the sectoral system of Thai rice, economic policy, policies related to property rights are linked with and affect the agendas for research and technology transfer. It could imply the possibilities to enhance the synergies between each domain through the expansion of formal linkages and the creation of more coherence in research policies.

REFERENCES

Bodie, A. R., Micciche, A. C., Atungulu, G. G., Rothrock Jr, M. J., & Ricke, S. C. (2019). Current trends of rice milling by-products for agricultural applications and alternative food production systems. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, 47.

Buddhaboon, C., Sankum, Y., Tongnoy, S., t, A. (2022). Adaptation of Rice Production System to Climate Change in Thailand: Trend and Policy. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/3072.

Chaisalee, W., Jongkaewwattana, A., Tanticharoen, M., & Bhumiratana, S. (2010). Triple Helix System: The Heart of Innovation and Development for Rural Community in Thailand. In the 8th Triple Helix International Scientific and Organizing Committees. Spain.

Department of Rice (2011). History of Department of Rice. Bangkok, Thailand: Department of Rice. Retrieved from http://www.ricethailand.go.th web/images/pdf/history.pdf (in Thai).

FAO (2011). The dynamic tension between public and private plant breeding in Thailand. FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 208. Rome: FAO.

FAO (2018). Country fact sheet on food and agriculture policy trends. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/I8684EN/i8684en.pdf.

FAO. (2018). Rice Market Monitor XXI(1). Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3 /I9243EN /i9243en.pdf

Gijsbers, G., & Tulder, R. V. (2011). New Asian challenges: Missing linkages in Asian agricultural innovation and the role of public research organizations in four small-and-medium-sized Asian countries. Science, Technology and Society, 16(1), 29-51.]

Jaroensathapornkul, J. (2007). The Economic Impact of Public Rice Research in Thailand. Chulalongkorn Journal of Economics, 19(2), 111-134.

Joblaew, P., Sirisunyaluck, R., Kanjina, S., Chalermphol, J., & Prom–u–thai, C. (2020). Factors affecting farmers’ adoption of rice production technology from the collaborative farming project in Phrae province, Thailand. International Journal of Agricultural Technology, 15(6), 901-912.

Kwanmuang, K., Pongputhinan, T., Jabri, A., & Chitchumnung, P. (2020). Small-scale farmers under Thailand’s smart farming system. FFTC-AP, 2647.

Lee, S. (2021). In the Era of Climate Change: Moving Beyond Conventional Agriculture in Thailand. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development, 18(1362-2021-1176), 1-14.

Lertdhamtewe, P. (2015). Intellectual Property Law of Plant Varieties in Thailand: A Contextual Analysis. IIC-International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 46(4), 386-409.

Liu, Z., Jongsma, M. A., Huang, C., Dons, J. J. M., & Omta, S. W. F. (2015). The sectoral innovation system of the Dutch vegetable breeding industry. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 74(1), 27-39.

Malerba, F. (2002). Sectoral systems of innovation and production. Research Policy, 31(2), 247-264.

Ministry of Science and Technology. (2016) Annual Report. Ministry of Science and Technology. Retrieved from http://www.clinictech.ops.go.th/online/filemanager /fileclinic/F1/files/summaryreport2016.pdf

Napasintuwong, O. (2018). Rice breeding and R&D policies in Thailand. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from thttp://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=85

Napasintuwong, O. (2019). Rice Economy of Thailand. ARE Working Paper No. 2562/1. (January 2019). Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand

Napasintuwong, O. (2020). Thailand’s Colored Rice Standard and Markets. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from : http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=1100

NESDB. (2008). The First National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development B.E. 2551–2554 (2008–2011). Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Bangkok, Thailand.

OAE. (2013). Draft of the Second National Strategic Plan for Organic Agriculture Development B.E. 2556– 2559 (2013–2016). Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Bangkok, Thailand.

Poapongsakorn, N. (2019). Overview of rice policy 2000–2018 in Thailand: A political economy analysis. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asia and Pacific Region Agricultural Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1426.

Pochanukul, P. (1990). The Development of Publicly-conducted Crop Research in Thailand. Japanese Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 28(1), 20-44.

Rerkasem, B. (2017). The rice value chain: a case study of Thai rice. Chiang Mai University Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(1), 1-26.

Sowcharoensuk, C. (2022). Industry Outlook 2022-2024: Rice Industry. Krungsri Research. Retrieved from https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/ industry-outlook/agriculture/rice/io/io-rice-2022

Suwanmaneepong, S., Kerdsriserm, C., Iyapunya, K., & Wongtragoon, U. (2020). Farmers’ adoption of organic rice production in Chachoengsao province, Thailand. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 24(2), 71-79.

Tanasugarn, L. (1998 November). Jasmine rice crisis: A Thai perspective. In Intellectual Property and International Trade Law Forum Special Issue. Bangkok: Central Intellectual Property and Trade Court.

Titapiwatanakun, B. (2012). The rice situation in Thailand. Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report (TA-REG, 74595). Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/ default/files/project-document/73082/43430-012-reg-tacr-03.pdf.

Thitinunsomboon, S., Chairatana, P. A., & Keeratipibul, S. (2008). Sectoral innovation systems in agriculture: the case of rice in Thailand. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 16(1), 83-100.

Toojinda, T., & Lanceras-Siangliw, J. (2013). Advancing Thailand’s rice Agriculture through molecular breeding. Asia-Pacific Biotech News, 17(4). 40-43.

Triratanasirichai, K., Singh, M., and Anal, A. K. (2017). Value-added byproducts from rice processing industries, in Food Processing By-Products and Their Utilization, ed A. K. Anal (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons), 277–293