ABSTRACT

The Japanese rice fish, also known as medaka, is increasing in popularity as ornamental fish. The mutant breeding of new varieties of non-wild medaka is booming among medaka lovers. However, there is no generally accepted framework for labeling non-wild medaka varieties, which causes serious problems such as fraudulent trade. Four years ago, searching for solutions to solve this problem, the Japan Medaka Association, a voluntary organization of non-wild medaka lovers, submitted a proposal to establish a system for labeling and registering new varieties. Currently, the Japan Medaka Association is tackling the challenge of persuading all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the Japan Medaka Association, to favor this proposal.

Keywords: Fraud, Mutant Breeding, Non-wild Medaka, Oba Yukio, Selecting Breeding, Wild Medaka

INTRODUCTION

The Japanese rice fish, also known as medaka, is widely recognized as a symbolic icon of rice farming in Japan. A medaka has a body weight of 0.6-0.9 grams, a body length of 2-3 centimeters, and is dark grey in color. Medaka appears in many traditional Japanese paintings, songs, and poetry, which depict rural life in Japan’s bygone days[1].

Medaka did not have any direct effect on rice farming and used to be abundant in Japanese paddy fields, but due to their low tolerance of agrochemicals, the population in the wild declined drastically due to the spread of agrochemicals in the post-WWII period. In 1999, the Japanese government included medaka in its list of endangered species.

Previously, when medaka were abundant in paddy fields, most of the Japanese general publics were not interested in maintaining medaka under artificial conditions, such as aquariums. However, the popularity of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish has increased because of the disappearance of wild medaka. Mutant breeding of non-wild medaka has boomed among non-wild medaka lovers since the 2000s. As a result, the total number of non-wild medaka varieties has drastically increased.

Currently, non-wild medaka are popularly purchased and sold in pet shops and by non-wild medaka lovers. However, the lack of generally accepted rules for labeling medaka varieties causes various problems such as fraud. Searching for solutions to this problem, the Japan Medaka Association (JMA), which was founded in 2009 as a voluntary group of non-wild medaka lovers, submitted a proposal for establishing a new system for labeling and registering non-wild medaka varieties (henceforth referred to as “the JMA proposal”). Does the JMA’s proposal present a fair and consistent system? Will the system be realized? By answering these questions, this paper aims to describe the current situation of Japan’s non-wild medaka.

THE BIOLOGY OF MEDAKA

Before discussing the trade problems of non-wild medaka, it would be useful to present the basic information on medaka biology[2]. A wild medaka reproduces approximately four months after birth. The conditions of spawning are: (1) from 15 to 27 centigrade in water temperature, and (2) more than 13 hours of sunlight in a day. A female medaka releases nearly 20 eggs on waterweeds every day once it starts spawning (the spawning period spans nearly 20 days). A male medaka inseminates a female by closely attaching when she starts spawning. Medaka are polyphagous: they eat bacterioplankton (e.g., rotifers, water fleas, and paramecia), phytoplankton (e.g., diatoms and chlorella), mosquito larvae, small insects, and small crustaceans. Predators of medaka include dragonfly nymphs, giant water bugs, gobies, flesh-eating fishes, prawns, wagtails, and kingfishers.

Compared to other ornamental fish, such as goldfish, tropical fish, and fancy carp, medaka can be easily raised as pets because they are physically strong. Medaka can survive in water with temperatures of 2 to 38 degrees centigrade and pH levels of 5 to 9. Medaka can be raised both indoors and outdoors. If medaka are raised in outdoor water, where bacterioplankton, phytoplankton, and mosquito larvae emerge spontaneously, there is no need for feeding. If medaka are raised indoors, live bait, such as paramecia, should be fed. Maintaining the population density of medaka to at least 10 liters of water per medaka is preferable.

From a genetic standpoint, medaka are known for their high rate of mutation[3]. This means that anyone keeping medakas has a good chance of finding new varieties.

DEVELOPING NEW VARIETIES OF NON-WILD MEDAKA

When medaka are abundant in paddy fields, they are not usually recognized as targets for selective breeding. An exception is a variety of non-wild medaka, called himedaka, whose body is orange-red. Himedaka can survive only in an artificial environment, such as an indoor aquarium, which is protected from natural enemies (it is difficult for a himedaka to survive in the wild because its orange-red color makes it easy for predators to spot). Himedaka was allegedly developed during the Edo period (1603-1868)[4]. However, exactly how and when himedaka developed remains unclear.

For years, there have been no non-wild medaka varieties other than himedaka. Oba Yukio, now a living legend among non-wild medaka lovers, changed this situation[5]. Initially, he found a small number of mutant individuals in a group of himedaka that were scarlet colored. He separated these individuals from the others and waited for egg deposition. Once the eggs hatched, the scarlet-colored individuals were selected for further mating. By repeating this process for three years, he obtained a special group of medaka individuals in which the scarlet-colored body was almost perfectly passed on from generation to generation. He named this variety of medaka yokihi, the Japanese name for Yang Guifei (an exquisitely beautiful woman who lived in China in the 8th century). In 2004, he began selling himedaka at prices nearly five times higher than wild medaka.

Yokihi’s beauty attracted ornamental fish lovers. Importantly, as will be discussed in the following section, Oba Yukio neither received high-level academic training nor had expensive facilities for breeding. This proved that anyone has the chance to develop new and beautiful varieties of non-wild medaka.

OBA YUKIO: “FATHER OF NON-WILD MEDAKA”

Before further discussion, it is worth having a quick review of Oba Yukio’s personal history, since he is nicknamed “father of non-wild medaka”[6].

After graduating from high school, Oba Yukio changed jobs several times. He sometimes worked as a factory worker, house-to-house salesperson, or landscape designer[7]. Medaka was (and is) often used as a component of Japanese gardening. When engaged in landscape design, he was charmed by the beauty of medaka. He held the view that there was much room for fostering the business and culture of non-wild medaka by inspiring the public with the charm of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish.

In 2000, quitting landscape design, he opened an unseen type of pet shop, named Medakano Yakata (literally translating to “Medaka’s House”), in Hiroshima. This was the first pet shop in Japan to specialize in medaka[8].

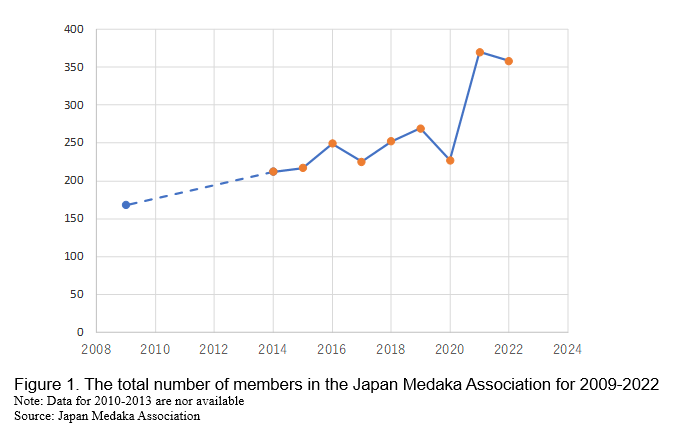

As Oba Yukio observed, the popularity of non-wild medaka was increasing annually[9]. This motivated him to establish a private organization to enhance mutual friendships among non-wild medaka lovers throughout the nation. In 2009, he and seven of his friends founded the JMA, Japan’s first nationwide organization of non-wild medaka lovers. The headquarters of the JMA are in Medakano Yakata. The entrance fee is ¥2,000 (nearly US$15) and the annual membership fee is ¥6,000 (nearly US$45). As the first major event in its activities, the JMA organized a beauty contest for non-wild medaka in April 2009. Since then, the JMA’s beauty contest for non-wild medaka has been held twice annually. The JMA also issues a monthly bulletin to its members. Figure 1 shows the total number of JMA members for 2009-2022. While the JMA is small of members, the reputation of the JMA is high among non-wild medaka lovers.

PROBLEM OF LABELING MEDAKA VARIETIES

Oba Yukio’s success in developing yokihi led to a boom in mutation breeding for new varieties of non-wild medaka. One problem is that the meaning (and/or judgment) of a variety (and new variety) differs according to the person. From a commonsense view, in order to claim a group of individuals as a new variety, it must satisfy the following two conditions: all individuals in the group have a characteristic that is unseen in any other existing variety, and the new characteristic is hereditary. However, judgements about whether a group satisfies these two conditions may differ from person to person. In addition, there are no generally accepted rules on how to name new medaka varieties.

As a result, when selling and/or purchasing medaka, the following three types of problems often arise:

- The same variety of medaka is sold under different variety names;

- An existing variety of medaka is sold by falsely stating it is a new variety; and

- While some individuals are sold as a new variety because their characteristic is unseen in any other existing variety, it cannot be transmitted to their children.

THE JMA PROPOSAL FOR ESTABLISHING A NEW SYSTEM FOR LABELING AND REGISTERING NON-WILD MEDAKA VARIETIES

To solve the above-mentioned problems, in April 2019, the JMA launched a special team consisting of eight of its most influential members. Oba Kenji, Oba Yukio’s second son, assumed leadership of the special team[10]. After in-depth discussions, the special team issued a proposal for rules on medaka variety labeling (henceforth referred to as “the JMA proposal”) in April 2021[11]. The essence of this study is as follows:

- The characteristics of medaka consists of seven elements: body color, squama, eyes, chromophores, black spots, fins, and body shape;

- There are 11 types of body colors: standard (similar to wild medaka body color), brown, yellow, white, blue, black, gold, amber, scarlet, orange-red, and pink;

- There are three types of squama: standard (similar to wild medaka squama), transparent, and half-transparent;

- There are seven types of eyes: standard (similar to wild medaka eyes), albino, small, goggled, monotonic black, anteverted, and big;

- There are six types of chromophores: standard (similar to wild medaka chromophores), whole-body type 1 (non-transparent), whole-body type 2 (transparent), back, inside, and belly;

- There are three types of black spots: standard (similar to wild medaka spots), whole body, and spotty spots;

- There are three types of fins: standard (similar to wild medaka fins), double dorsal fin, diamond tail fin, no dorsal fin, no skin, partially tall, entirely tall, large, and long anal fin;

- There are four types of body shape: standard (similar to wild medaka body shape), light, the shape of Bodhidharma, and mixture of light and the shape of Bodhidharma;

- In the case of wild medaka, all seven factors were standardized. If at least one factor was not standard, it was considered a non-wild medaka. This means that, in theory, there are 13,055 possible combinations of characteristic types for non-wild medaka (11×3×7×6×3×8×4-1=13,055);

- Let us consider the case of mating non-wild medaka individuals with the same characteristics. Some of their children may have the same characteristic passed on from their parents, whereas others may not. The percentage of the former among all the children is called the “transmission ratio.” If a group of non-wild medaka individuals have a brand-new type of character (e.g., green colored body) and the transmission rate exceeds 30%, they should be recognized as a new variety;

- The JMA estimates that nearly 700 of 13,055 combinations have already been developed. If a group of non-wild medaka individuals have the characteristics of a new combination and the transmission rate exceeds 30%, they should be recognized as a new variety;

- A breeder who first develops a new variety should report to the JMA to confirm that he or she is the first developer; and

- The first developer of a new variety is entitled to place nicknames on the variety. The formal name of the variety should be expressed using a combination of seven factors. For example, a yokihi is regarded as a nickname given by Oba Yukio. Yokihi’s formal variety name is expressed as “a variety of scarlet body color, standard squama, standard eye, standard chromophore, standard black spot, standard fin, and standard body shape.”

The JMA proposal presents a consistent and suitable framework for labeling non-wild medaka varieties. However, because the JMA is only a voluntary organization, unless the government provides legal support for the JMA proposal, it is not easy for the JMA to persuade all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the JMA, to favor the JMA proposal.

NON-WILD MEDAKA’S POTENTIAL IN THE INTERNATIONAL ORNAMENTAL FISH MARKET

Japan has a rich culture of ornamental fishes. For example, Japan’s fancy carp is famous worldwide among ornamental fish lovers, and is booming in the international market. The total value of exports of Japan’s fancy carp increased from ¥1.4 billion (nearly US$10.5 million) in the 2003 fiscal year to ¥3.9 billion (nearly US$29.3 million) in the 2021 fiscal year[12].

Although there are no official statistics on the total value of medaka exports, shops are aware of the enormous potential of non-wild medaka as an export commodity. For example, as reported by Godo (2020), Arashimaya, a non-wild medaka pet shop, attracted ornamental fish lovers from Hong Kong as soon as a direct flight between Hong Kong Airport and Yonago Airport opened in 2019[13]. This increased Arashimaya’s total sales by nearly 1.5 times higher than the previous year. To increase the potential of non-wild medaka in the international market, it is desirable for Japan to establish a consistent framework for labeling medaka varieties, such as that presented in the JMA proposal.

CONCLUSION

Medaka symbolizes Japan’s rural life and used to be abundant in paddy fields. While medaka is now disappearing in the wild due to the spread of agrochemicals, the popularity of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish is increasing. In particular, mutant breeding of non-wild medaka has been booming since Oba Yukio, a pioneer of non-wild medaka breeding, developed a new variety called yokihi.

As there is no generally accepted framework for labeling medaka varieties, fraud often occurs when purchasing and selling non-wild medaka. The JMA proposed a scheme for improving fairness and transparency in trading non-wild medaka individuals. Currently, the JMA is tackling the challenge of persuading all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the JMA, to favor the JMA proposal.

REFERENCES

Munekata, Arimune, Tadao Kitagawa, Makito Kobayashi, 2020. Nihon No Yasei Medaka Wo Mamoru (Japanese Wild Medaka on the Brink of Extinction), Seibutsu Kenkyu Sha.

Iwamatsu, Takashi, 2018. The Integrated Book for the Biology of the Medaka (Third Edition), Tokyo: Daigaku Kyoiku Shuppam.

Medakano Yakata, 2021. Medaka Collection (2021 version), Hiroshima: Medakano Yakata.

Godo, Yoshihisa, 2021. “Kairyo Medakano Kikkyo (Potentials and Risks of Non-wild Medaka)”, Kometo Ryutsu, Vol. 46, No. 11.

- For example, in 2018, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the National Congress of Parents and Teachers Associations of Japan recognized that Medakano Gakko (literally translating to “Medaka’s School”) was one of the top 100 popular folk songs in Japan.

- Iwamatasu (2018) provides comprehensive information on the biology of medaka.

[5] In Japan, it is common for a family name or last name to appear first, followed by the first name (Japanese people do not have middle names). This paper follows the traditional Japanese method of expressing people’s names.

[6] Asahi Shimbun, one of the top newspapers in Japan, describes Oba Yukio as the pioneer of the business related to non-wild medaka (for example, Medaka Hyakunen Tsuduku Bunkani (Japanese rice fish should be Japan’s new culture), Asahi Newspaper July 27, 2021, morning edition of Hiroshima version, page 23.

[7] As part of landscape design, Oba Yukio loved trimming satsuki (Rhododendron indicum), which was (and still is) one of the most popular flowering trees in Japanese gardens. Satsuki originated in Japan. Through cross-breeding and collection of mutations, there are nearly 1,500 varieties of satsuki (https://botanica-media.jp/1902). Although he was not engaged in developing new varieties of satsuki, he dreamed of developing new varieties of plants and animals.

[8] Until Oba Yasuo opened Medakano Yakata in 2000, medaka was sold only in a small part of a pet shop.

[9] As of 2019, it is estimated that more than 5 million families keep medaka at home as ornamental fish, and the total number of pet shops specializing in medaka exceeds 100 (https://jyoge-ippin.jp/company/439/).

[10] Oba Kenji holds a master’s degree in agronomy. While he usually works as a researcher at a public food laboratory, he is also involved in the JMA’s activities during his leisure time.

[11] Details of the JMA proposal are available at Medakano Yakata (2021).

[12] The export data are taken from the Trade Statistics of Japan, edited by the Ministry of Finance ( https://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/tsdl.htm ). The Japanese fiscal year starts on April 1 in the calendar year and ends on March 31 in the next calendar year.

[13] International flights between Hong Kong Airport and Yonago Airport have been suspended since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020.

The Japan Medaka Association’s Proposal for a Labeling System for Japanese Rice Fish Varieties

ABSTRACT

The Japanese rice fish, also known as medaka, is increasing in popularity as ornamental fish. The mutant breeding of new varieties of non-wild medaka is booming among medaka lovers. However, there is no generally accepted framework for labeling non-wild medaka varieties, which causes serious problems such as fraudulent trade. Four years ago, searching for solutions to solve this problem, the Japan Medaka Association, a voluntary organization of non-wild medaka lovers, submitted a proposal to establish a system for labeling and registering new varieties. Currently, the Japan Medaka Association is tackling the challenge of persuading all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the Japan Medaka Association, to favor this proposal.

Keywords: Fraud, Mutant Breeding, Non-wild Medaka, Oba Yukio, Selecting Breeding, Wild Medaka

INTRODUCTION

The Japanese rice fish, also known as medaka, is widely recognized as a symbolic icon of rice farming in Japan. A medaka has a body weight of 0.6-0.9 grams, a body length of 2-3 centimeters, and is dark grey in color. Medaka appears in many traditional Japanese paintings, songs, and poetry, which depict rural life in Japan’s bygone days[1].

Medaka did not have any direct effect on rice farming and used to be abundant in Japanese paddy fields, but due to their low tolerance of agrochemicals, the population in the wild declined drastically due to the spread of agrochemicals in the post-WWII period. In 1999, the Japanese government included medaka in its list of endangered species.

Previously, when medaka were abundant in paddy fields, most of the Japanese general publics were not interested in maintaining medaka under artificial conditions, such as aquariums. However, the popularity of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish has increased because of the disappearance of wild medaka. Mutant breeding of non-wild medaka has boomed among non-wild medaka lovers since the 2000s. As a result, the total number of non-wild medaka varieties has drastically increased.

Currently, non-wild medaka are popularly purchased and sold in pet shops and by non-wild medaka lovers. However, the lack of generally accepted rules for labeling medaka varieties causes various problems such as fraud. Searching for solutions to this problem, the Japan Medaka Association (JMA), which was founded in 2009 as a voluntary group of non-wild medaka lovers, submitted a proposal for establishing a new system for labeling and registering non-wild medaka varieties (henceforth referred to as “the JMA proposal”). Does the JMA’s proposal present a fair and consistent system? Will the system be realized? By answering these questions, this paper aims to describe the current situation of Japan’s non-wild medaka.

THE BIOLOGY OF MEDAKA

Before discussing the trade problems of non-wild medaka, it would be useful to present the basic information on medaka biology[2]. A wild medaka reproduces approximately four months after birth. The conditions of spawning are: (1) from 15 to 27 centigrade in water temperature, and (2) more than 13 hours of sunlight in a day. A female medaka releases nearly 20 eggs on waterweeds every day once it starts spawning (the spawning period spans nearly 20 days). A male medaka inseminates a female by closely attaching when she starts spawning. Medaka are polyphagous: they eat bacterioplankton (e.g., rotifers, water fleas, and paramecia), phytoplankton (e.g., diatoms and chlorella), mosquito larvae, small insects, and small crustaceans. Predators of medaka include dragonfly nymphs, giant water bugs, gobies, flesh-eating fishes, prawns, wagtails, and kingfishers.

Compared to other ornamental fish, such as goldfish, tropical fish, and fancy carp, medaka can be easily raised as pets because they are physically strong. Medaka can survive in water with temperatures of 2 to 38 degrees centigrade and pH levels of 5 to 9. Medaka can be raised both indoors and outdoors. If medaka are raised in outdoor water, where bacterioplankton, phytoplankton, and mosquito larvae emerge spontaneously, there is no need for feeding. If medaka are raised indoors, live bait, such as paramecia, should be fed. Maintaining the population density of medaka to at least 10 liters of water per medaka is preferable.

From a genetic standpoint, medaka are known for their high rate of mutation[3]. This means that anyone keeping medakas has a good chance of finding new varieties.

DEVELOPING NEW VARIETIES OF NON-WILD MEDAKA

When medaka are abundant in paddy fields, they are not usually recognized as targets for selective breeding. An exception is a variety of non-wild medaka, called himedaka, whose body is orange-red. Himedaka can survive only in an artificial environment, such as an indoor aquarium, which is protected from natural enemies (it is difficult for a himedaka to survive in the wild because its orange-red color makes it easy for predators to spot). Himedaka was allegedly developed during the Edo period (1603-1868)[4]. However, exactly how and when himedaka developed remains unclear.

For years, there have been no non-wild medaka varieties other than himedaka. Oba Yukio, now a living legend among non-wild medaka lovers, changed this situation[5]. Initially, he found a small number of mutant individuals in a group of himedaka that were scarlet colored. He separated these individuals from the others and waited for egg deposition. Once the eggs hatched, the scarlet-colored individuals were selected for further mating. By repeating this process for three years, he obtained a special group of medaka individuals in which the scarlet-colored body was almost perfectly passed on from generation to generation. He named this variety of medaka yokihi, the Japanese name for Yang Guifei (an exquisitely beautiful woman who lived in China in the 8th century). In 2004, he began selling himedaka at prices nearly five times higher than wild medaka.

Yokihi’s beauty attracted ornamental fish lovers. Importantly, as will be discussed in the following section, Oba Yukio neither received high-level academic training nor had expensive facilities for breeding. This proved that anyone has the chance to develop new and beautiful varieties of non-wild medaka.

OBA YUKIO: “FATHER OF NON-WILD MEDAKA”

Before further discussion, it is worth having a quick review of Oba Yukio’s personal history, since he is nicknamed “father of non-wild medaka”[6].

After graduating from high school, Oba Yukio changed jobs several times. He sometimes worked as a factory worker, house-to-house salesperson, or landscape designer[7]. Medaka was (and is) often used as a component of Japanese gardening. When engaged in landscape design, he was charmed by the beauty of medaka. He held the view that there was much room for fostering the business and culture of non-wild medaka by inspiring the public with the charm of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish.

In 2000, quitting landscape design, he opened an unseen type of pet shop, named Medakano Yakata (literally translating to “Medaka’s House”), in Hiroshima. This was the first pet shop in Japan to specialize in medaka[8].

As Oba Yukio observed, the popularity of non-wild medaka was increasing annually[9]. This motivated him to establish a private organization to enhance mutual friendships among non-wild medaka lovers throughout the nation. In 2009, he and seven of his friends founded the JMA, Japan’s first nationwide organization of non-wild medaka lovers. The headquarters of the JMA are in Medakano Yakata. The entrance fee is ¥2,000 (nearly US$15) and the annual membership fee is ¥6,000 (nearly US$45). As the first major event in its activities, the JMA organized a beauty contest for non-wild medaka in April 2009. Since then, the JMA’s beauty contest for non-wild medaka has been held twice annually. The JMA also issues a monthly bulletin to its members. Figure 1 shows the total number of JMA members for 2009-2022. While the JMA is small of members, the reputation of the JMA is high among non-wild medaka lovers.

PROBLEM OF LABELING MEDAKA VARIETIES

Oba Yukio’s success in developing yokihi led to a boom in mutation breeding for new varieties of non-wild medaka. One problem is that the meaning (and/or judgment) of a variety (and new variety) differs according to the person. From a commonsense view, in order to claim a group of individuals as a new variety, it must satisfy the following two conditions: all individuals in the group have a characteristic that is unseen in any other existing variety, and the new characteristic is hereditary. However, judgements about whether a group satisfies these two conditions may differ from person to person. In addition, there are no generally accepted rules on how to name new medaka varieties.

As a result, when selling and/or purchasing medaka, the following three types of problems often arise:

THE JMA PROPOSAL FOR ESTABLISHING A NEW SYSTEM FOR LABELING AND REGISTERING NON-WILD MEDAKA VARIETIES

To solve the above-mentioned problems, in April 2019, the JMA launched a special team consisting of eight of its most influential members. Oba Kenji, Oba Yukio’s second son, assumed leadership of the special team[10]. After in-depth discussions, the special team issued a proposal for rules on medaka variety labeling (henceforth referred to as “the JMA proposal”) in April 2021[11]. The essence of this study is as follows:

The JMA proposal presents a consistent and suitable framework for labeling non-wild medaka varieties. However, because the JMA is only a voluntary organization, unless the government provides legal support for the JMA proposal, it is not easy for the JMA to persuade all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the JMA, to favor the JMA proposal.

NON-WILD MEDAKA’S POTENTIAL IN THE INTERNATIONAL ORNAMENTAL FISH MARKET

Japan has a rich culture of ornamental fishes. For example, Japan’s fancy carp is famous worldwide among ornamental fish lovers, and is booming in the international market. The total value of exports of Japan’s fancy carp increased from ¥1.4 billion (nearly US$10.5 million) in the 2003 fiscal year to ¥3.9 billion (nearly US$29.3 million) in the 2021 fiscal year[12].

Although there are no official statistics on the total value of medaka exports, shops are aware of the enormous potential of non-wild medaka as an export commodity. For example, as reported by Godo (2020), Arashimaya, a non-wild medaka pet shop, attracted ornamental fish lovers from Hong Kong as soon as a direct flight between Hong Kong Airport and Yonago Airport opened in 2019[13]. This increased Arashimaya’s total sales by nearly 1.5 times higher than the previous year. To increase the potential of non-wild medaka in the international market, it is desirable for Japan to establish a consistent framework for labeling medaka varieties, such as that presented in the JMA proposal.

CONCLUSION

Medaka symbolizes Japan’s rural life and used to be abundant in paddy fields. While medaka is now disappearing in the wild due to the spread of agrochemicals, the popularity of non-wild medaka as ornamental fish is increasing. In particular, mutant breeding of non-wild medaka has been booming since Oba Yukio, a pioneer of non-wild medaka breeding, developed a new variety called yokihi.

As there is no generally accepted framework for labeling medaka varieties, fraud often occurs when purchasing and selling non-wild medaka. The JMA proposed a scheme for improving fairness and transparency in trading non-wild medaka individuals. Currently, the JMA is tackling the challenge of persuading all non-wild medaka lovers, including those who do not belong to the JMA, to favor the JMA proposal.

REFERENCES

Munekata, Arimune, Tadao Kitagawa, Makito Kobayashi, 2020. Nihon No Yasei Medaka Wo Mamoru (Japanese Wild Medaka on the Brink of Extinction), Seibutsu Kenkyu Sha.

Iwamatsu, Takashi, 2018. The Integrated Book for the Biology of the Medaka (Third Edition), Tokyo: Daigaku Kyoiku Shuppam.

Medakano Yakata, 2021. Medaka Collection (2021 version), Hiroshima: Medakano Yakata.

Godo, Yoshihisa, 2021. “Kairyo Medakano Kikkyo (Potentials and Risks of Non-wild Medaka)”, Kometo Ryutsu, Vol. 46, No. 11.

[4] See https://piscesbook.com/archives/6086.

[5] In Japan, it is common for a family name or last name to appear first, followed by the first name (Japanese people do not have middle names). This paper follows the traditional Japanese method of expressing people’s names.

[6] Asahi Shimbun, one of the top newspapers in Japan, describes Oba Yukio as the pioneer of the business related to non-wild medaka (for example, Medaka Hyakunen Tsuduku Bunkani (Japanese rice fish should be Japan’s new culture), Asahi Newspaper July 27, 2021, morning edition of Hiroshima version, page 23.

[7] As part of landscape design, Oba Yukio loved trimming satsuki (Rhododendron indicum), which was (and still is) one of the most popular flowering trees in Japanese gardens. Satsuki originated in Japan. Through cross-breeding and collection of mutations, there are nearly 1,500 varieties of satsuki (https://botanica-media.jp/1902). Although he was not engaged in developing new varieties of satsuki, he dreamed of developing new varieties of plants and animals.

[8] Until Oba Yasuo opened Medakano Yakata in 2000, medaka was sold only in a small part of a pet shop.

[9] As of 2019, it is estimated that more than 5 million families keep medaka at home as ornamental fish, and the total number of pet shops specializing in medaka exceeds 100 (https://jyoge-ippin.jp/company/439/).

[10] Oba Kenji holds a master’s degree in agronomy. While he usually works as a researcher at a public food laboratory, he is also involved in the JMA’s activities during his leisure time.

[11] Details of the JMA proposal are available at Medakano Yakata (2021).

[12] The export data are taken from the Trade Statistics of Japan, edited by the Ministry of Finance ( https://www.customs.go.jp/toukei/info/tsdl.htm ). The Japanese fiscal year starts on April 1 in the calendar year and ends on March 31 in the next calendar year.

[13] International flights between Hong Kong Airport and Yonago Airport have been suspended since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020.