ABSTRACT

On 18 May 2021, the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture issued Regulation Number 18/2021 concerning the Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development in the country. This regulation expects to facilitate business investment as mandated by Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation and Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector. Within more than one year, the implementation of this regulation still faces dynamic perspectives among oil palm stakeholders. The policy review of this paper indicates that the extent of socialization of this regulation is still low since it is considered not sufficiently implemented and requires operational guidelines to be more easily understood by all relevant stakeholders. Hence, massive and measurable socialization is recommended. The preparation of socialization materials is essential to generate harmonization and synergy among the central and local governments, business companies, communities, and other relevant parties.

Keywords: oil palm, facilitation, development, policy, community farms, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

Agriculture has a vital role in Indonesia’s economy. In 2021, this sector contributed 13.28% to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or the second largest after manufacturing industries (19.25%). One of the sub-sectors with considerable potential is plantation (estate crops) which contributes about 3.94% to the national GDP. In the same year, this sub-sector contributed 29.97% to the agricultural GDP (BPS, 2021).

Within the plantation sub-sector, oil palm is one of the essential commodities in Indonesia, i.e., to produce vegetable oil required by the industrial sector. Palm oil is suitable for various uses, including industrial oil and fuel/biodiesel. It is because the commodity has oxidation-resistant properties at high pressure, dissolves chemicals that are insoluble in other solvents, and high-coating ability (MoT, 2013).

Indonesia ranked first in the global oil palm fruit (Rob Cook, 2023). The country contributes 60.14% of the total world’s oil palm fruit (450.21 million tons), followed by Malaysia (24.26%), Thailand (4.11%), Nigeria (2.45%), and Colombia (2.05%). Indonesia has great potential for domestic and global markets, namely Crude Palm Oil (CPO) and Palm Kernel Oil (PKO) for fractionation/refining industries (especially cooking oil), special fats (cocoa butter substitution), margarine/shortening, oleochemical, body soaps, and others.

According to BPS (2021), there are 14,586,589 hectares of oil palm plantation area in Indonesia comprising 7,977,298 hectares of private plantation (54.69%), 6,044,058 hectares of smallholder plantation (41.44%), and 565,241 hectares of state plantation (3.88%). Oil palm plantation is one of the income sources of Indonesian farmers. Due to the lack of information on access to quality seeds, proper management methods, and funding sources, the productivity of smallholder plantations was quite low (Databox, 2020). The average productivity of smallholder plantation was about 2.50 tons CPO per hectare, or lower than those of state and private plantations i.e., 3.32 tons and 3.49 tons CPO per hectare, respectively (DGEC, 2021).

Since smallholders critically support the oil palm industry in Indonesia, the government issued the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 on Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development (MoA, 2021). The essence of this regulation is to generate a good business partnership opportunity model between private companies and smallholders toward improving sustainable palm oil governance in Indonesia and to narrow the gap between them (Ichsan, et.al., 2021).

Objectives

This paper reviews the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 concerning the Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development in Indonesia. It discusses a brief overview of Indonesia’s oil palm industry followed by a policy review including perspective and challenges, conclusion, and recommendation related to the implementation of this regulation.

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF INDONESIA’S OIL PALM INDUSTRY

Area

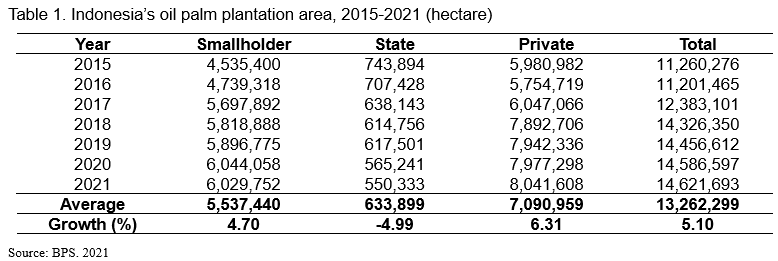

In the last seven years (2015-2021), the average area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia was 13,262,299 hectares (Table 1). The oil palm plantations are managed by smallholders (41.75%), state (4.78%), and private (53.47%). Within these periods, the total area of oil palm plantations increased by about 5.10% per year, from 11,260,276 hectares to 14,621,693 hectares. The highest increase was in private plantations (6.31%/year), followed by smallholder plantations (4.70%/year). Meanwhile, the total area of state plantations decreased by about 4.99% per year (Table 1).

Oil palm plantation areas are spread across 26 provinces in Indonesia. The central producing area is Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java regions. About 76.54% was in Sumatra, followed by Kalimantan and Sulawesi i.e., 19.22% and 3.42% respectively. Riau is the largest palm oil-producing province with an area of 2.86 million hectares or 19.55% of the total area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia.

Production and productivity

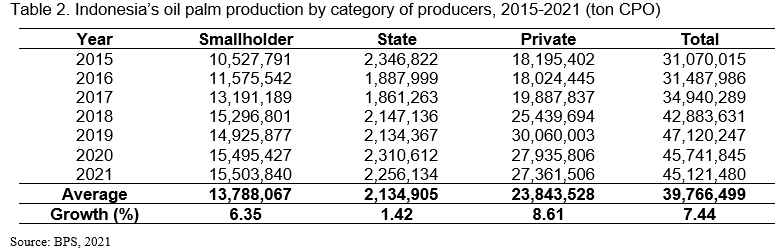

The total production of oil palm in Indonesia is shown in Table 2. From 2015 to 2021, the average production of oil palm was 39,766,499 tons of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) with an increase of about 7.44% annually. The highest increase was in private plantations (8.61%/year), followed by smallholder plantations (6.35%/year) and state plantations (1.42 %/year).

The average productivity of Indonesia’s oil palm over the last seven years (2015-2021) was about 2.98 tons per hectare, namely increased by 2.48% per year (Table 3). The highest productivity was from state plantations (3.41 tons/ha), followed by private and smallholder plantations (3.34 tons/ha and 2.48 tons/ha, respectively). As a result, higher productivity relatively indicates better plantation management.

Consumption

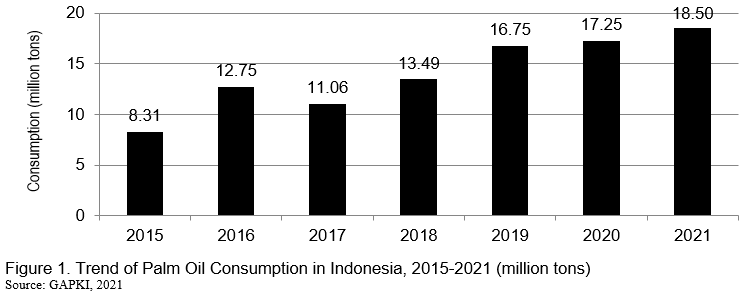

The trend of palm oil consumption tends to increase relatively from year to year (Figure 1). Palm oil consumption in 2021 was 18.50 million tons, or higher than the average consumption from 2015 to 2021 (14.02 million tons). During these periods, the decline in consumption only occurred in 2017 by 13.25% i.e., from 12.75 million tons to 11.06 million tons in the following year. The majority of palm oil was for export (65.02%), and the rest was for domestic consumption comprising of food, biodiesel, and oleochemical (Table 4). It notes that the use of biodiesel has increased rapidly due to the mandatory biodiesel program which gradually started in 2008.

Export and import

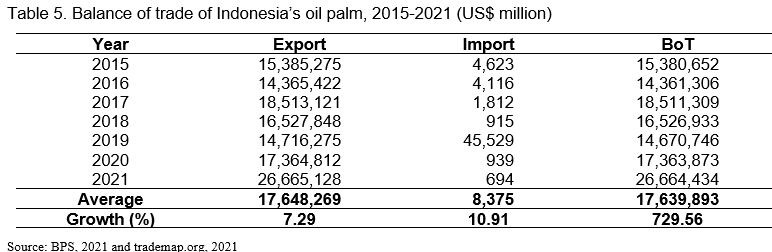

Indonesia has a favorable balance of trade (BoT) surplus of oil palm commodities. In the last seven years (2015-2021), the average BoT of this commodity was US$17,639,893 annually (Table 5). The trend for exports was an increase by 7.29% per year. Meanwhile, the extent of imports tends to be positive, especially due to imports of other palm oil (HS 15119000) in 2019. It notes that there was a decrease in export value from 2018 to 2019 due to falling palm oil prices on the global market. Conversely, at the same time, the import value increased significantly due to the national processing industry importing raw material of CPO for oleochemical which was triggered by a black campaign on the market that domestic CPO did not meet the technical requirements for biodiesel development and quality issues.

Human resources

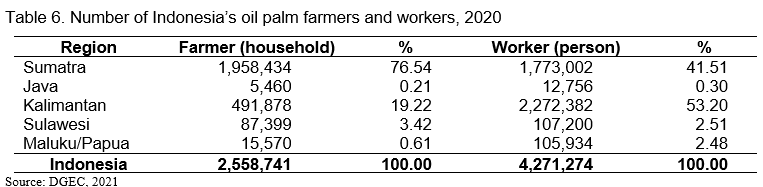

Human resources in Indonesia’s oil palm plantations consist of farmers and workers (Table 6). In 2020, there were 2,558,741 farmer households, the majority was in the Sumatra region (main central producing area), namely 1,958,434 households (76.54%). Others were in Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java regions. In the same year, the number of workers was 4,271,274 people. The highest number was in Kalimantan, namely 2,272,382 people (53.20%). Consecutively, the oil palm plantation workers were in Sumatra, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java.

POLICY REVIEW

The Indonesian palm oil industry plays an important role in the national economy involving many business actors from various economic groups. The national oil palm plantations continue to grow significantly with an area of 16.38 million hectares and employ more than 17 million heads of households, farmers, and employees who work in the on-farm and off-farm sectors. In order to encourage the sustainability of the palm oil industry, the government has implemented a regulatory framework and encouraged multi-stakeholder cooperation in the palm oil sector (CMEA, 2022).

The development of the Indonesian palm oil policy is closely related to time/when and is very dynamically developing from time to time. Referring to the concept of dividing the stages of oil palm industrialization (Sipayung et al., 2012), so far the policy dynamics pursued by Indonesia have led to an increase in total factor productivity and added value in an innovation-driven position (Figure 2). On the other hand, oil palm plantation business actors in Indonesia (state, private, and community) with various business scales have led to a fairly massive expansion of oil palm land since 2006, resulting in a condition where the government needed to be present by issuing regulations both upstream and downstream to accommodate common interests.

Overview of Indonesian palm oil development policy

Indonesia’s oil palm has rapidly developed since 2006. In that year, the country succeeded as the largest producer and exporter of palm oil in the world. Indonesia dominated the global trade of this commodity with Malaysia as a competitor country.

The high opportunity for the world market and domestic production of oil palm has been optimally utilized by strengthening the CPO downstream industry. It is expected to increase competitiveness and added value which have an impact on state revenues. Even though Sari (2010) stated that Indonesian palm oil has a comparative advantage in all palm oil products, Nova (2010) believes that it is still below Malaysia in terms of the development of derivative products.

Indonesia has implemented mixed upstream and downstream policies to continually push forward palm oil through various restrictive and stimulus policies in the form of subsidies, incentives, and taxes on the downstream side. On the upstream side, it develops the priority plantation policies through various technological innovations and capacity building of farmers to be able to realize sustainable increases in production and productivity performances. Hence, efforts in synergizing across sectors and integrating palm oil upstream and downstream have been implemented based on the issuance of Presidential Regulation Number 44/2020 on the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Plantations Certification System (GoI, 2020c). It was followed by establishing sustainable palm oil as part of the national action plan through Presidential Instruction Number 6/2019 on the National Action Plan for Sustainable Oil Palm Plantations (GoI, 2019), Regulation of Agricultural Minister Number 3/2022 on Development of Human Resources, Research and Developments, Rejuvenations, Infrastructures, and Facilities of Oil Palm Plantations (MoA, 2022). Those are supported by the mandatory biodiesel policy as part of the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020-2024 (GoI, 2020b) that cannot be separated from the regulations used as a guideline in the development of palm oil.

Facilitation of local community farm development

Facilitation of local community farm development is one of the many regulations that essentially develop the upstream oil palm in Indonesia. This aspect was mandated by Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 based on Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation (GoI, 2020a) and Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2021). The former provides the investment ecosystem by creating possible employment opportunities for the community on an equal basis and providing convenience for business companies to invest. The latter is concerned with the implementation of the agricultural sector.

The essence of Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 is related to the responsibility of the company to provide support and ease of access to financing, knowledge, and cultivation techniques to generate local community welfare through developing farms until the plants produce. It implements through credit and profit-sharing schemes, other forms of funding agreed upon by the parties, and partnerships (MoA, 2021).

The content of Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 is summarized in Table 7. It comprises of two stages, namely: (1) Preparation (socialization, identification/determination of potential farmers/farms, institutional farmers, and administrative requirements); and (2) Implementation (development facilitation and handover of farms).

Reflection and argues

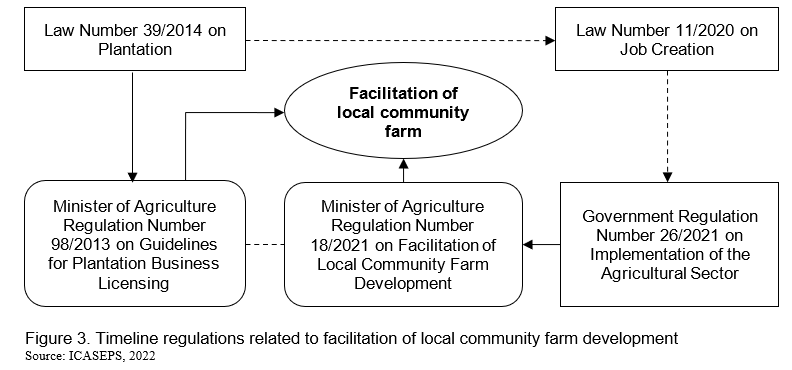

The facilitation of local community farm development is an obligation in the form of the contribution of companies’ communities as a result of opening oil palm plantation land that can be seen as an investment activity that brings profits and business continuity. The implementation of this facilitation has been supported by certain regulations presented in Figure 3.

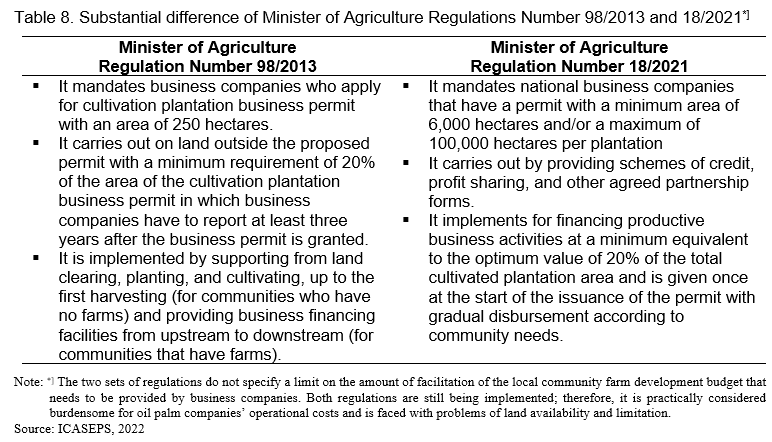

The primary support was Law Number 39/2014 on Plantation (GoI, 2014), operated by the Ministry of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013 on Guidelines for Plantation Business Licensing (MoA, 2013). Since Law Number 39/2014 was amended by Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation (GoI, 2020); therefore, the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development was translated and further regulated by Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2021) to be operated by Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 (MoA, 2021). Consequently, there are two types of regulations applied in the field, which have substantial mechanisms (Table 8).

It notes that the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 attempts to improve and provide certain obligations of the previous Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013. In essence, business companies are both objects and subjects of a set of regulations related to the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development, while the government as a regulator oversees and ensures that the implementation of the obligation can be carried out properly. However, there were some occurrence problems in the field due to an accumulation of applicable regulations and the existence of multiple interpretations from business companies, communities, and local governments.

The existence of Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 has not been fully able to respond to the land provided for the community since it faced the main problem of land availability and limitations as existed in the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013. It requires further efforts to provide more guarantees for continuing the business of companies and receiving the benefit of communities. Therefore, there is a need for communicative and comprehensive approaches from all parties to identify and determine the types of facilitation obligations required in both regulations.

There are crucial value points in the obligations of the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021. They are:

- The determination of the obligation value of 20% from the concession land can generate problems based-perspective of business companies. It notes that not all concession lands are productive oil palm plantations. There are some supporting infrastructures such as farm roads, ditches, drains, fences, and buildings for offices, employee mess, warehouses, and other facilities. Thus, the business companies expected that the 20% of land determination should take into account the reality in the field.

- The optimum value is the average net production in one year. Up to the present, the determination of the optimum value cannot be fully implemented since it is still under discussion. Determining the optimum value has a problem because not all oil palm plantations are planted simultaneously in each block and the variable land suitability. Apart from that, there are some differences among regions that will potentially lead to a variety of different optimum values.

Determining the form and pattern of the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development will be greatly influenced by the value of the obligations. Mechanisms for planning, implementing, and compiling cooperation agreements are the next crucial points. Support and easy access to financing as well as knowledge and cultivation techniques in developing until producing community’s farms are the main goals of the obligations.

There were new impacts and problems related to the implementation of obligations. Consequently, the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms with different patterns and forms will be equally important as required measurable indicators of achieving the implementation of obligations. These are not clearly stated in the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021. The regulation only includes a monitoring form for business companies in terms of monitoring the development of oil palm plantations in terms of physical development and rejuvenation activities. Indeed, there is a need to assess the performance of activities related to the level of technology adoption and outcome impacts. The scheme of obligations can take various forms such as financing, profit sharing, grants, contributions, joint ventures, and other forms of funding within the framework of a partnership or non-partnership patterns.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion

The obligation of facilitation of the local community plantation farm development does not always have to be in the form of developing new plantations but it can be carried out for improving the productive plantation business activities based-financing mechanism through determining the optimum value of obligations.

Determination of the optimum value of obligations becomes a crucial point. It is followed by determining the activity's obligations which involve many stakeholders, both central and local governments, business companies, and communities as subjects and objects of the implementation of facilitation of the local community plantation farm development.

The mechanism is not complete enough to be implemented in the field because there is no determination of the optimum value as a basis for calculating the obligations. In addition, differences in perceptions and multiple interpretations still occur frequently in the field and become a prolonged polemic.

The extent of socialization is still low since the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 is considered not sufficiently operational and still requires operational guidelines of supporting regulations to be more easily understood by all relevant stakeholders.

Recommendations

The Indonesian Minister of Agriculture through the Directorate General of Estate crops should immediately develop the determination and mechanism of the optimum value of the plantation. It is required that other necessary supporting regulations such as general guidelines and implementation instructions be used as a complement to the operationalization of Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 at the field level.

Determining the optimum value requires caution and considering variables such as plant age, land type, and variations among oil palm plantation areas. It is recommended in determining the optimum value to specify transparently and fairly the costs and revenues that result in net plantation production. The optimum value must be reliable so that it can be accepted by all parties, bearing in mind that the optimum value is the basis for determining the value of obligations among central producing areas of oil palm.

Above all, massive and measurable socialization is required. The preparation of socialization materials is essential to generate harmonization and synergy among central and local governments, business companies, communities, and other relevant parties.

REFERENCES

BPS. 2021. Statistik Kelapa Sawit Indonesia 2021 (Indonesia Oil Palm Statistics). Badan Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

CMEA. 2022. Pemerintah Terus Dorong Industri Sawit Berkelanjutan dari Hulu hingga Hilir (The Government Continues to Encourage the Sustainable Palm Oil Industry from Upstream to Downstream). Retrieved from: https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/4639/pemerintah-terus-dorong-ind... (14 April 2023). Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs of the Republic of Indonesi. Jakarta.

Databox. 2020. 2,7 Juta Petani Bergantung pada Perkebunan Sawit Rakyat (2.7 Million Farmers depend on Smallholder Oil Palm Plantations). Retrieved from: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/ 2020/04/06/27-juta-petani-bergantung-pada-perkebunan-sawit-rakyat (5 January 2023).

DGEC. 2021. Statistik Perkebunan Unggulan Nasional 2020-2022 (Statistics of National Leading Estate Crops Commodity 2020-2022). Directorate General of Estate Crops. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GoI. 2014. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 39 Tahun 2014 tentang Perkebunan (Law Number 39/2014 on Plantation).Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2019. Instruksi Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 6 Tahun 2019 tentang Rencana Aksi Nasional Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Berkelanjutan (Presidential Instruction Number 6/2019 on the National Action Plan for Sustainable Oil Palm Plantations). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020a. Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2020 tentang Cipta Kerja (Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta

GoI. 2020b. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2020 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional Tahun 2020-2024 (Presidential Regulation of Republic Indonesia Number 18/2020 on National Mid-term Development Plan 2020-2024). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020c. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 44 Tahun 2020 tentang Sistem Sertifikasi Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Berkelanjutan Indonesia (Presidential Regulation Number 44/2020 on the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Plantation Certification System). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2021. Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 26 Tahun 2021 tentang Penyelenggaraan Bidang Pertanian (Regulation of Government of Indonesia Number 26 of 2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

ICASEPS. 2022. Critical Review: Potensi Dampak Implementasi Permentan Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 terhadap Investasi dan Industri Perkebunan Sawit (Critical Review: Potential Impacts of Implementation of Minister of Agriculture Number 18/2021 on Oil Palm Plantation Investment and Industry). Policy Brief. Indonesian Center for Agricultural Socioeconomic and Policy Sudies. Bogor.

Ichsan, M., W. Saputra, and A. Permatasari. 2021. Oil Palm Smallholders on the Edge: Why Business Partnerships Need to be Redefined. Information Brief: Published on 6 July 2021. SPOS Indonesia, KEHATI, and UKaid from the British people. Jakarta.

MoA. 2013. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 98 Tahun 2013 tentang Pedoman Perizinan Usaha Perkebunan (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 98/2013 on Guidelines for Plantation Business Licensing). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2021. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 tentang Fasilitasi Pembangunan Kebun Masyarakat Sekitar (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 18/2021 on Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2022. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 3 Tahun 2022 tentang Pengembangan Sumber Daya Manusia, Penelitian dan Pengembangan, Peremajaan serta Sarana dan Prasarana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit (Regulation of Agricultural Minister Number 3/2022 on Development of Human Resources, Research and Developments, Rejuvenations, Infrastructures, and Facilities of Oil Palm Plantations). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoT. 2013. Market Brief Kelapa Sawit dan Olahannya (Market Brief of Palm Oil and Its Processed Products). Indonesian Ministry of Trade. Jakarta.

Nova, V. 2010. The effect of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) export tax on the production of its derivative products in Indonesia. Thesis, International institute of social studies, The Hague.

Rob Cook. 2023. Indonesia was the largest producer of oil palm fruit in the world in 2019 followed by Malaysia and Thailand. Retrieved from: https://beef2live.com/story-ranking-countries-produce-oil-palm-fruit-fao... (17 January 2023). Ranking of Countries that Produce the Most Oil Palm Fruit (FAO). Rob Cook, Published on 15 January 2023.

Sari, E. T. 2010. Revealed comparative advantage (RCA) and constant market share model (CMS) of Indonesian palm oil in ASEAN market. Thesis. Agribusiness Management Prince of Songkla University, Bangkok.

Sipayung, t. and j. H. V. Purba. 2015. Ekonomi Agribisnis Minyak Sawit (Palm Oil Economic Agribusiness). Palm Oil Agribusiness Policy Institute (PASPI). Bogor.

Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development in Indonesia: A Policy Review

ABSTRACT

On 18 May 2021, the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture issued Regulation Number 18/2021 concerning the Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development in the country. This regulation expects to facilitate business investment as mandated by Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation and Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector. Within more than one year, the implementation of this regulation still faces dynamic perspectives among oil palm stakeholders. The policy review of this paper indicates that the extent of socialization of this regulation is still low since it is considered not sufficiently implemented and requires operational guidelines to be more easily understood by all relevant stakeholders. Hence, massive and measurable socialization is recommended. The preparation of socialization materials is essential to generate harmonization and synergy among the central and local governments, business companies, communities, and other relevant parties.

Keywords: oil palm, facilitation, development, policy, community farms, Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Background

Agriculture has a vital role in Indonesia’s economy. In 2021, this sector contributed 13.28% to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or the second largest after manufacturing industries (19.25%). One of the sub-sectors with considerable potential is plantation (estate crops) which contributes about 3.94% to the national GDP. In the same year, this sub-sector contributed 29.97% to the agricultural GDP (BPS, 2021).

Within the plantation sub-sector, oil palm is one of the essential commodities in Indonesia, i.e., to produce vegetable oil required by the industrial sector. Palm oil is suitable for various uses, including industrial oil and fuel/biodiesel. It is because the commodity has oxidation-resistant properties at high pressure, dissolves chemicals that are insoluble in other solvents, and high-coating ability (MoT, 2013).

Indonesia ranked first in the global oil palm fruit (Rob Cook, 2023). The country contributes 60.14% of the total world’s oil palm fruit (450.21 million tons), followed by Malaysia (24.26%), Thailand (4.11%), Nigeria (2.45%), and Colombia (2.05%). Indonesia has great potential for domestic and global markets, namely Crude Palm Oil (CPO) and Palm Kernel Oil (PKO) for fractionation/refining industries (especially cooking oil), special fats (cocoa butter substitution), margarine/shortening, oleochemical, body soaps, and others.

According to BPS (2021), there are 14,586,589 hectares of oil palm plantation area in Indonesia comprising 7,977,298 hectares of private plantation (54.69%), 6,044,058 hectares of smallholder plantation (41.44%), and 565,241 hectares of state plantation (3.88%). Oil palm plantation is one of the income sources of Indonesian farmers. Due to the lack of information on access to quality seeds, proper management methods, and funding sources, the productivity of smallholder plantations was quite low (Databox, 2020). The average productivity of smallholder plantation was about 2.50 tons CPO per hectare, or lower than those of state and private plantations i.e., 3.32 tons and 3.49 tons CPO per hectare, respectively (DGEC, 2021).

Since smallholders critically support the oil palm industry in Indonesia, the government issued the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 on Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development (MoA, 2021). The essence of this regulation is to generate a good business partnership opportunity model between private companies and smallholders toward improving sustainable palm oil governance in Indonesia and to narrow the gap between them (Ichsan, et.al., 2021).

Objectives

This paper reviews the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 concerning the Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development in Indonesia. It discusses a brief overview of Indonesia’s oil palm industry followed by a policy review including perspective and challenges, conclusion, and recommendation related to the implementation of this regulation.

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF INDONESIA’S OIL PALM INDUSTRY

Area

In the last seven years (2015-2021), the average area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia was 13,262,299 hectares (Table 1). The oil palm plantations are managed by smallholders (41.75%), state (4.78%), and private (53.47%). Within these periods, the total area of oil palm plantations increased by about 5.10% per year, from 11,260,276 hectares to 14,621,693 hectares. The highest increase was in private plantations (6.31%/year), followed by smallholder plantations (4.70%/year). Meanwhile, the total area of state plantations decreased by about 4.99% per year (Table 1).

Oil palm plantation areas are spread across 26 provinces in Indonesia. The central producing area is Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java regions. About 76.54% was in Sumatra, followed by Kalimantan and Sulawesi i.e., 19.22% and 3.42% respectively. Riau is the largest palm oil-producing province with an area of 2.86 million hectares or 19.55% of the total area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia.

Production and productivity

The total production of oil palm in Indonesia is shown in Table 2. From 2015 to 2021, the average production of oil palm was 39,766,499 tons of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) with an increase of about 7.44% annually. The highest increase was in private plantations (8.61%/year), followed by smallholder plantations (6.35%/year) and state plantations (1.42 %/year).

The average productivity of Indonesia’s oil palm over the last seven years (2015-2021) was about 2.98 tons per hectare, namely increased by 2.48% per year (Table 3). The highest productivity was from state plantations (3.41 tons/ha), followed by private and smallholder plantations (3.34 tons/ha and 2.48 tons/ha, respectively). As a result, higher productivity relatively indicates better plantation management.

Consumption

The trend of palm oil consumption tends to increase relatively from year to year (Figure 1). Palm oil consumption in 2021 was 18.50 million tons, or higher than the average consumption from 2015 to 2021 (14.02 million tons). During these periods, the decline in consumption only occurred in 2017 by 13.25% i.e., from 12.75 million tons to 11.06 million tons in the following year. The majority of palm oil was for export (65.02%), and the rest was for domestic consumption comprising of food, biodiesel, and oleochemical (Table 4). It notes that the use of biodiesel has increased rapidly due to the mandatory biodiesel program which gradually started in 2008.

Export and import

Indonesia has a favorable balance of trade (BoT) surplus of oil palm commodities. In the last seven years (2015-2021), the average BoT of this commodity was US$17,639,893 annually (Table 5). The trend for exports was an increase by 7.29% per year. Meanwhile, the extent of imports tends to be positive, especially due to imports of other palm oil (HS 15119000) in 2019. It notes that there was a decrease in export value from 2018 to 2019 due to falling palm oil prices on the global market. Conversely, at the same time, the import value increased significantly due to the national processing industry importing raw material of CPO for oleochemical which was triggered by a black campaign on the market that domestic CPO did not meet the technical requirements for biodiesel development and quality issues.

Human resources

Human resources in Indonesia’s oil palm plantations consist of farmers and workers (Table 6). In 2020, there were 2,558,741 farmer households, the majority was in the Sumatra region (main central producing area), namely 1,958,434 households (76.54%). Others were in Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java regions. In the same year, the number of workers was 4,271,274 people. The highest number was in Kalimantan, namely 2,272,382 people (53.20%). Consecutively, the oil palm plantation workers were in Sumatra, Sulawesi, Maluku/Papua, and Java.

POLICY REVIEW

The Indonesian palm oil industry plays an important role in the national economy involving many business actors from various economic groups. The national oil palm plantations continue to grow significantly with an area of 16.38 million hectares and employ more than 17 million heads of households, farmers, and employees who work in the on-farm and off-farm sectors. In order to encourage the sustainability of the palm oil industry, the government has implemented a regulatory framework and encouraged multi-stakeholder cooperation in the palm oil sector (CMEA, 2022).

The development of the Indonesian palm oil policy is closely related to time/when and is very dynamically developing from time to time. Referring to the concept of dividing the stages of oil palm industrialization (Sipayung et al., 2012), so far the policy dynamics pursued by Indonesia have led to an increase in total factor productivity and added value in an innovation-driven position (Figure 2). On the other hand, oil palm plantation business actors in Indonesia (state, private, and community) with various business scales have led to a fairly massive expansion of oil palm land since 2006, resulting in a condition where the government needed to be present by issuing regulations both upstream and downstream to accommodate common interests.

Overview of Indonesian palm oil development policy

Indonesia’s oil palm has rapidly developed since 2006. In that year, the country succeeded as the largest producer and exporter of palm oil in the world. Indonesia dominated the global trade of this commodity with Malaysia as a competitor country.

The high opportunity for the world market and domestic production of oil palm has been optimally utilized by strengthening the CPO downstream industry. It is expected to increase competitiveness and added value which have an impact on state revenues. Even though Sari (2010) stated that Indonesian palm oil has a comparative advantage in all palm oil products, Nova (2010) believes that it is still below Malaysia in terms of the development of derivative products.

Indonesia has implemented mixed upstream and downstream policies to continually push forward palm oil through various restrictive and stimulus policies in the form of subsidies, incentives, and taxes on the downstream side. On the upstream side, it develops the priority plantation policies through various technological innovations and capacity building of farmers to be able to realize sustainable increases in production and productivity performances. Hence, efforts in synergizing across sectors and integrating palm oil upstream and downstream have been implemented based on the issuance of Presidential Regulation Number 44/2020 on the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Plantations Certification System (GoI, 2020c). It was followed by establishing sustainable palm oil as part of the national action plan through Presidential Instruction Number 6/2019 on the National Action Plan for Sustainable Oil Palm Plantations (GoI, 2019), Regulation of Agricultural Minister Number 3/2022 on Development of Human Resources, Research and Developments, Rejuvenations, Infrastructures, and Facilities of Oil Palm Plantations (MoA, 2022). Those are supported by the mandatory biodiesel policy as part of the National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020-2024 (GoI, 2020b) that cannot be separated from the regulations used as a guideline in the development of palm oil.

Facilitation of local community farm development

Facilitation of local community farm development is one of the many regulations that essentially develop the upstream oil palm in Indonesia. This aspect was mandated by Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 based on Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation (GoI, 2020a) and Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2021). The former provides the investment ecosystem by creating possible employment opportunities for the community on an equal basis and providing convenience for business companies to invest. The latter is concerned with the implementation of the agricultural sector.

The essence of Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 is related to the responsibility of the company to provide support and ease of access to financing, knowledge, and cultivation techniques to generate local community welfare through developing farms until the plants produce. It implements through credit and profit-sharing schemes, other forms of funding agreed upon by the parties, and partnerships (MoA, 2021).

The content of Agricultural Minister Regulation Number 18/2021 is summarized in Table 7. It comprises of two stages, namely: (1) Preparation (socialization, identification/determination of potential farmers/farms, institutional farmers, and administrative requirements); and (2) Implementation (development facilitation and handover of farms).

Reflection and argues

The facilitation of local community farm development is an obligation in the form of the contribution of companies’ communities as a result of opening oil palm plantation land that can be seen as an investment activity that brings profits and business continuity. The implementation of this facilitation has been supported by certain regulations presented in Figure 3.

The primary support was Law Number 39/2014 on Plantation (GoI, 2014), operated by the Ministry of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013 on Guidelines for Plantation Business Licensing (MoA, 2013). Since Law Number 39/2014 was amended by Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation (GoI, 2020); therefore, the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development was translated and further regulated by Government Regulation Number 26/2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector (GoI, 2021) to be operated by Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 (MoA, 2021). Consequently, there are two types of regulations applied in the field, which have substantial mechanisms (Table 8).

It notes that the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 attempts to improve and provide certain obligations of the previous Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013. In essence, business companies are both objects and subjects of a set of regulations related to the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development, while the government as a regulator oversees and ensures that the implementation of the obligation can be carried out properly. However, there were some occurrence problems in the field due to an accumulation of applicable regulations and the existence of multiple interpretations from business companies, communities, and local governments.

The existence of Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 has not been fully able to respond to the land provided for the community since it faced the main problem of land availability and limitations as existed in the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 98/2013. It requires further efforts to provide more guarantees for continuing the business of companies and receiving the benefit of communities. Therefore, there is a need for communicative and comprehensive approaches from all parties to identify and determine the types of facilitation obligations required in both regulations.

There are crucial value points in the obligations of the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021. They are:

Determining the form and pattern of the implementation of facilitation of local community farm development will be greatly influenced by the value of the obligations. Mechanisms for planning, implementing, and compiling cooperation agreements are the next crucial points. Support and easy access to financing as well as knowledge and cultivation techniques in developing until producing community’s farms are the main goals of the obligations.

There were new impacts and problems related to the implementation of obligations. Consequently, the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms with different patterns and forms will be equally important as required measurable indicators of achieving the implementation of obligations. These are not clearly stated in the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021. The regulation only includes a monitoring form for business companies in terms of monitoring the development of oil palm plantations in terms of physical development and rejuvenation activities. Indeed, there is a need to assess the performance of activities related to the level of technology adoption and outcome impacts. The scheme of obligations can take various forms such as financing, profit sharing, grants, contributions, joint ventures, and other forms of funding within the framework of a partnership or non-partnership patterns.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion

The obligation of facilitation of the local community plantation farm development does not always have to be in the form of developing new plantations but it can be carried out for improving the productive plantation business activities based-financing mechanism through determining the optimum value of obligations.

Determination of the optimum value of obligations becomes a crucial point. It is followed by determining the activity's obligations which involve many stakeholders, both central and local governments, business companies, and communities as subjects and objects of the implementation of facilitation of the local community plantation farm development.

The mechanism is not complete enough to be implemented in the field because there is no determination of the optimum value as a basis for calculating the obligations. In addition, differences in perceptions and multiple interpretations still occur frequently in the field and become a prolonged polemic.

The extent of socialization is still low since the Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 is considered not sufficiently operational and still requires operational guidelines of supporting regulations to be more easily understood by all relevant stakeholders.

Recommendations

The Indonesian Minister of Agriculture through the Directorate General of Estate crops should immediately develop the determination and mechanism of the optimum value of the plantation. It is required that other necessary supporting regulations such as general guidelines and implementation instructions be used as a complement to the operationalization of Minister of Agriculture Regulation Number 18/2021 at the field level.

Determining the optimum value requires caution and considering variables such as plant age, land type, and variations among oil palm plantation areas. It is recommended in determining the optimum value to specify transparently and fairly the costs and revenues that result in net plantation production. The optimum value must be reliable so that it can be accepted by all parties, bearing in mind that the optimum value is the basis for determining the value of obligations among central producing areas of oil palm.

Above all, massive and measurable socialization is required. The preparation of socialization materials is essential to generate harmonization and synergy among central and local governments, business companies, communities, and other relevant parties.

REFERENCES

BPS. 2021. Statistik Kelapa Sawit Indonesia 2021 (Indonesia Oil Palm Statistics). Badan Pusat Statistik (Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics). Jakarta.

CMEA. 2022. Pemerintah Terus Dorong Industri Sawit Berkelanjutan dari Hulu hingga Hilir (The Government Continues to Encourage the Sustainable Palm Oil Industry from Upstream to Downstream). Retrieved from: https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/4639/pemerintah-terus-dorong-ind... (14 April 2023). Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs of the Republic of Indonesi. Jakarta.

Databox. 2020. 2,7 Juta Petani Bergantung pada Perkebunan Sawit Rakyat (2.7 Million Farmers depend on Smallholder Oil Palm Plantations). Retrieved from: https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/ 2020/04/06/27-juta-petani-bergantung-pada-perkebunan-sawit-rakyat (5 January 2023).

DGEC. 2021. Statistik Perkebunan Unggulan Nasional 2020-2022 (Statistics of National Leading Estate Crops Commodity 2020-2022). Directorate General of Estate Crops. Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

GoI. 2014. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 39 Tahun 2014 tentang Perkebunan (Law Number 39/2014 on Plantation).Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2019. Instruksi Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 6 Tahun 2019 tentang Rencana Aksi Nasional Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Berkelanjutan (Presidential Instruction Number 6/2019 on the National Action Plan for Sustainable Oil Palm Plantations). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020a. Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2020 tentang Cipta Kerja (Law Number 11/2020 on Job Creation). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta

GoI. 2020b. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2020 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional Tahun 2020-2024 (Presidential Regulation of Republic Indonesia Number 18/2020 on National Mid-term Development Plan 2020-2024). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2020c. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia Nomor 44 Tahun 2020 tentang Sistem Sertifikasi Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit Berkelanjutan Indonesia (Presidential Regulation Number 44/2020 on the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) Plantation Certification System). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

GoI. 2021. Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia Nomor 26 Tahun 2021 tentang Penyelenggaraan Bidang Pertanian (Regulation of Government of Indonesia Number 26 of 2021 on Implementation of the Agricultural Sector). Government of Indonesia. Jakarta.

ICASEPS. 2022. Critical Review: Potensi Dampak Implementasi Permentan Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 terhadap Investasi dan Industri Perkebunan Sawit (Critical Review: Potential Impacts of Implementation of Minister of Agriculture Number 18/2021 on Oil Palm Plantation Investment and Industry). Policy Brief. Indonesian Center for Agricultural Socioeconomic and Policy Sudies. Bogor.

Ichsan, M., W. Saputra, and A. Permatasari. 2021. Oil Palm Smallholders on the Edge: Why Business Partnerships Need to be Redefined. Information Brief: Published on 6 July 2021. SPOS Indonesia, KEHATI, and UKaid from the British people. Jakarta.

MoA. 2013. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 98 Tahun 2013 tentang Pedoman Perizinan Usaha Perkebunan (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 98/2013 on Guidelines for Plantation Business Licensing). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2021. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 18 Tahun 2021 tentang Fasilitasi Pembangunan Kebun Masyarakat Sekitar (Regulation of the Indonesian Minister of Agriculture Number 18/2021 on Facilitation of the Local Community Plantation Farm Development). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoA. 2022. Peraturan Menteri Pertanian Republik Indonesia Nomor 3 Tahun 2022 tentang Pengembangan Sumber Daya Manusia, Penelitian dan Pengembangan, Peremajaan serta Sarana dan Prasarana Perkebunan Kelapa Sawit (Regulation of Agricultural Minister Number 3/2022 on Development of Human Resources, Research and Developments, Rejuvenations, Infrastructures, and Facilities of Oil Palm Plantations). Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture. Jakarta.

MoT. 2013. Market Brief Kelapa Sawit dan Olahannya (Market Brief of Palm Oil and Its Processed Products). Indonesian Ministry of Trade. Jakarta.

Nova, V. 2010. The effect of Crude Palm Oil (CPO) export tax on the production of its derivative products in Indonesia. Thesis, International institute of social studies, The Hague.

Rob Cook. 2023. Indonesia was the largest producer of oil palm fruit in the world in 2019 followed by Malaysia and Thailand. Retrieved from: https://beef2live.com/story-ranking-countries-produce-oil-palm-fruit-fao... (17 January 2023). Ranking of Countries that Produce the Most Oil Palm Fruit (FAO). Rob Cook, Published on 15 January 2023.

Sari, E. T. 2010. Revealed comparative advantage (RCA) and constant market share model (CMS) of Indonesian palm oil in ASEAN market. Thesis. Agribusiness Management Prince of Songkla University, Bangkok.

Sipayung, t. and j. H. V. Purba. 2015. Ekonomi Agribisnis Minyak Sawit (Palm Oil Economic Agribusiness). Palm Oil Agribusiness Policy Institute (PASPI). Bogor.