ABSTRACT

Potato is an important cash crop for many farmers in the rural area of Myanmar and especially in the hilly region of Southern Shan State and riverbanks in the lowlands in Magway Region. The consumption of potatoes in curries, crisps and French fries increases substantially in the coming years offering opportunities for employment and income. The potato sector in Myanmar has huge potentials and can contribute to rural development. Because there is currently limited knowledge of the potato sector, there is a need for an inventory and a description of the actual situation, and an assessment of possible developments. This study gives a glimpse of the current status of the potato sector and the ware potato value chain. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from potato farmers, traders and chip producers as primary sources and the published reports as secondary one. The area of potato cultivation has been dropped in 2020 - 2021 because of suffering a loss last year due to facing soil problem, import of potato from external countries, especially China from border trade, rising of inputs costs, particularly potato seeds and fertilizers. The potato farmers used the Chinese variety, Netherlands variety, and Indian variety for ware potato production. Most farmers (58%) sold their ware potatoes directly from the field due to lack of storage facilities. The 78% of total ware potato production in the study areas was sold to traders through respective traders' agents or directly to processors while farmers saved 22% for next potato seeds stored in cold storage for 3-7 months. The 35% of ware potatoes was marketed to traders through agents and 54% to traders directly and 11% to chip producers. The ware potatoes from traders were sold to retailers (25%), wholesalers in other townships (33%), consumers (13%) and chip producers (4%), respectively. As informal potato seeds, the traders kept the small potatoes and distributed to farmers (25%) when there was high demand during the growing season. In 2021, approximately 1.4% of the total ware potato production was taken for processing. Government should create a favorable environment for agrifood businesses by providing basic infrastructure: cold storage, creating the right market incentives, promoting inclusive agribusiness models, and supporting the use of information and communications technology that fosters inclusive value chains. For enabling smallholder farmers engagement in dynamic value chain, policies and regulatory frameworks should ensure access to rural financing, training and technical assistance, and subsidy program for agrochemicals.

Keywords: ware potatoes, value chain, smallholder farmers, high yield variety, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Agriculture is the predominant economic activity in the rural areas of Myanmar, and smallholders make up the largest share of farmers. Agricultural value chains are organizational schemes enabling a primary product to get sold and transformed into consumable end products, adding value at each step of a gradual process of transformation and marketing. The smallholder farmers integrate in value chains as producers in the primary production segment supplying products to local buyers. Domestic markets are the primary markets for smallholder farmers in Myanmar and their importance in crop production is likely to grow.

The economic growth of any nation is dependent on the health of the community which is driven by the availability, and accessibility of food. In Myanmar, ware potato is one of the key components in the livelihood system of the farmers as cash crop. Potato is a calorie-dense nutritious vegetable and is considered the most important non cereal crop for its contribution towards food security. Potato has been introduced in the mid-19th century in Myanmar, where there is a large producer of potatoes in Southeast Asia. At present, ware potato is an important cash crop for many farmers in the rural areas of Myanmar, especially in the hilly region of Southern Shan State and riverbanks in the lowlands in Magway Region, Central dry zone.

With the expected growth of the economy and income per capita, the consumption of potatoes (in curries and processed: crisps, French fries) could increase substantially in the coming years. The changing recent market demand offers opportunities for employment and income. The ever-increasing demand of processed food as one of the consequences of changing eating habits such as snacking leads to the increment of potato processing as an emerging fast growing industry as well as providing more opportunity for entrepreneurship. The rapid growth in farmer engagement in potato production and market demand is attributed to rapid urban population growth, and changing food eating habits of urban dwellers. This has a strong impact on potato markets, creating opportunities for the smallholder farmers but also posing serious threats due to competition with larger suppliers of potatoes globally (Njuki et al.,2005). However, smallholder farmers use the small potatoes of the previous harvest as seed potato, resulting in heavily diseased low yielding crops.

Though the bumper production, the farmers were devoid of a good margin from their cultivated product. The growers sell their products immediately after harvesting due to weak storage facilities, ignorance about market price and cash needs (Hajong et al., 2014). Basically, this distressed sale occurred during peak production season. Along with this, some other risk factors such as potato chip producer preferences and priority, weather instability, storing infestation of diseases and so on helps to change the market situation rapidly (Hall et al., 2006) which also triggered farmers to sell their product immediately after harvest. Middlemen are waiting for this situation and buy potatoes from farmers and stored, then sold them in high pricing month. Due to the above circumstances, the consumers need to pay more money for buying the product but farmers share on this wages is very low. Such an inefficient marketing system does not assure a remunerative price to the farmers. These problems present most of the developing countries due to the presence of excessive number of intermediaries between producers and consumers (Huq et al., 2004) but their role in marketing cannot be demoralized (De and Bhukta, 1994).

The potato sector in Myanmar has great potentials and can contribute to rural development. Because there is currently limited knowledge of the potato sector, there is a need for an inventory and a description of the actual situation, and an assessment of its possible developments. On behalf of the seed potato project in 2012-2015, specific needs related to technology and knowhow of local potato growers on storage and mechanization have been identified. Agronomists can fulfill those needs and can contribute to the future development of the potato sector in Myanmar.

The objectives of this study are to:

- review the potato sector in Myanmar, in relation to areas of production and production volumes; and

- observe the current status of ware potato value chain.

METHODOLOGY

Study areas

Heho, sub-township of Kalaw Township, and Naungtayar Township are the first and second biggest potato-growing areas among townships in Southern Shan State. Sinphyukyun, sub-township of Salin Township, and Magway Township in Magway Region are also considered the largest potato-growing area in Central dry zone of Myanmar (DoA, 2021). Therefore, these townships were selected as the study areas.

Data collection

For the purpose of this study, qualitative and quantitative data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. The primary sources of data were mainly ware potato producers in the region and state. In addition to the primary data gathered from these sources, supplementary information from other secondary sources was also gathered from various published and unpublished documents. The main sources of secondary data include reports from different organizations like the Department of Planning (DoP), Department of Agriculture (DoA), Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics (DALMS).

The primary information pertaining to potato production in the year 2020-2021 was collected from 96 randomly sampled households, 7 traders and 5 potato chip producers in the areas using standardized questionnaire. In addition to data gathering using standardized questionnaire, informal interviews with key farmers were also conducted. Before the actual data collection, preliminary test was carried out that enabled some modification on the questionnaire afterwards. Based on this preliminary test, some questions that were found to be irrelevant or misleading were modified to fit the existing situation in the study area.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Potato production in Myanmar

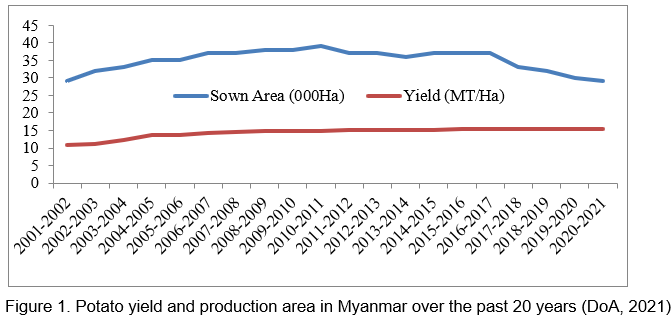

Potato was cultivated in 16,215 ha in monsoon and 13,969 ha in winter with the total yield of 450,116 tons in 2020-2021 (DoA). Over the past period, the average potato yields in Myanmar have steadily increased up to 15 tons/ha but seem to stabilize for recent years (Figure 1). The area of potato cultivation has been dropped in 2020 - 2021 because the farmers suffered a loss last year due to facing soil problem, import of potato from external countries, especially China from border trade, rising of inputs costs, particularly potato seeds and fertilizers.

Production region

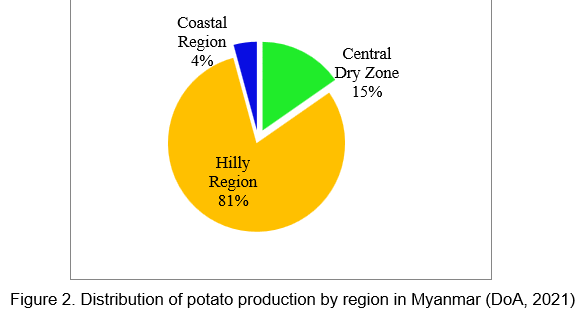

In Myanmar, potato is grown all-year round in 4 distinct seasons per region. This crop is grown on peaty and clay soils as an irrigated spring crop in rice paddies from January to April in Southern Shan State. This is a major crop with relatively high yields. It is as an early monsoon crop from April to August in the higher valleys (1,000-1,500 m above sea level) in the hilly regions of Shan State. This crop is rain-fed and is a minor crop during this season. As a late monsoon crop, potato is cultivated in the Southern Shan State from August to November. This is a major potato cropping season. The farmers cultivate this crop as a (minor) winter crop from November to February in the alluvial plains and irrigated crops in central Myanmar. The distribution of potato production of Myanmar by region is shown in Figure 2.

Export and import condition

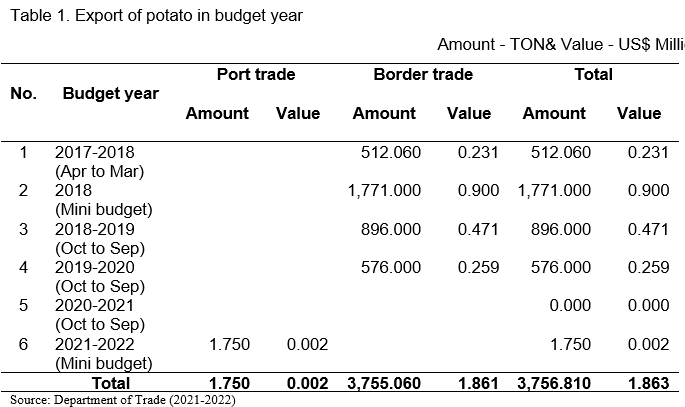

Myanmar's potatoes exports are categorized in four respective HS code. These are fresh or chilled potatoes (excluding seeds); potatoes, prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid, frozen; potatoes, prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid (excluding frozen) and potatoes, uncooked or cooked by steaming or by boiling in water, frozen. However, among 4 exported categories, potatoes that are prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid, frozen, could not be exported from Myanmar.

In 2019-2020 budget year, potatoes were exported with a worth of US$ 0.259 million; it was a drop of 45% from the 2018-2019 budget year in which the total potatoes export was US$ 0.471 million. In value terms, Thailand remained the key foreign market for potato exports from Myanmar, comprising 81% of total exports. The second position in the ranking was occupied by Malaysia, with a 14% share of total exports. Myanmar potatoes had not been exported in the 2020-2021 budget year because trade has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the current political situation.

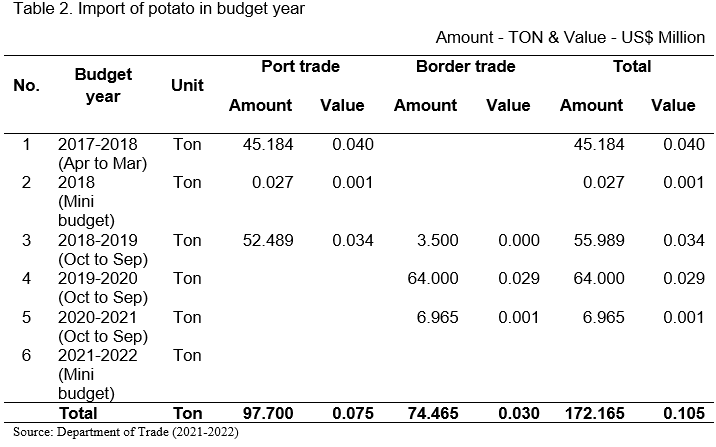

The Netherlands constituted the largest supplier of potato to Myanmar, comprising 40% of the country’s total imports. The second position in the ranking was occupied by Malaysia, with an 18% share of total imports. It was followed by India, with a 17% share. The imported potatoes have been used as seed potatoes and the farmers prefer the seed potatoes from the Netherlands.

Ware potato value chain

Ware potato consumption

Potatoes produced in Myanmar are mainly used for fresh consumption and small-scale potato chips production. Therefore, the potatoes are entirely marketed for domestic consumption. Consumption can be estimated by total production because all potato production is locally consumed. The average annual potato consumption per capita was about 7.86 kg in 2019 (FAOSTAT). In urban areas where preference for potato French fries and chips increases due to changing lifestyles, the potato is greatly in demand by urban residents.

Potato is one of the major culinary crops in Myanmar. In the domestic market, potatoes are arranged by traders and consumers depend on the products which enter in the market centers/ wholesalers. It is hard for consumers to choose the best potatoes because no branding is done, and varieties are often mixed. Consumer quality awareness is only concerned on tuber size: the bigger the better. Potato production is highly pro-poor and contributes to food security of the growers and their families through substantial employment, income and nutritious food; and it has a great potential if the constraints are removed.

Varieties of ware potato grown by farmers

In 1982, the varieties from India were grown in Southern Shan State (Taungyi and Pintaya). Among these varieties, Up-to-Date (Sip-Po in local name) and CIP 24 became the most growing varieties for high yield in Kalaw township. In 2011, PepsiCo Trading and Capital Diamond Star Group introduced the Atlantic variety of potato for French fries production. Other varieties: Granola, Jelly, Waneta, Jacqueline Lee, Lamoka, Calwhite, Carolus, Markies, Manistee, Marabel and Rosagold were trial on farms for improvement of the potato sector in Myanmar with a project in 2014. Farmers had also grown Megachip, PO3, Defender, Sarpomira, and Rumba variety.

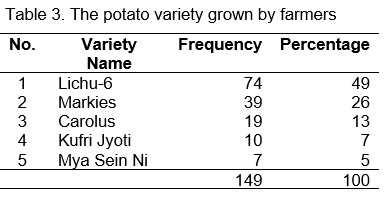

According to the result of survey data, the potato farmers have been using the variety Markies and Carolus introduced from the Netherlands, Lichu-6 from China, Kufri Jyoti from India in Southern Shan State and Magway Region. Some smallholder farmers grow the local variety, Mya Sein Ni. Last year, the farmers faced the Netherlands potato seed shortage due to trade disruption. Hence, they mostly used the Chinese variety, Lichu-6, imported from border area. It implies that the farmers are using any potato seeds available in the region through either imported by producer organization or saved by farmers/traders although they demanded the marketable existing varieties.

Marketing

Smallholder farmers sold ware potatoes at low farm gate prices, due to lack of storage facilities and unavailability of transportation services. Often they were forced to sell their products rapidly to cover for other needs and expenses. According to potato size, there were 6 grades: the lowest grade potato, A1, OK, S1, S2 and S3. Grade A1, OK and S1 potatoes were sold for home consumption and S2 and S3 for fried potato. As farmer saved potato seeds, OK and S1 were stored.

There was no evidence of collective marketing although the potato producer organizations exist. Regarding the analysis results, 58% of farmers could not store ware potatoes, and hence sold them directly from the field, leading to glut periods and low prices. Ware potato farmers were price takers despite supply and demand factors which determine the setting price. In Myanmar, seasonality in production makes farmers prone to exploitation by traders and agents. The 78% of total ware potato production in the study areas was sold to local traders through respective traders' agents or directly and to chip producers while farmers saved 22% for next potato seeds stored in cold storage for 3-7 months. The 35% of ware potatoes was marketed to traders through agents; 54 % directly to traders and 11% to chip producers. There are many different handlers in a vertical chain resulting in high transaction costs. From traders, the 25% of ware potatoes was sold to retailers; 33% transported to wholesalers in other townships; 13% to local consumers and 4% to potato chip producers. As an informal potato seed source, the traders kept the small ware potatoes and the 25% of ware potatoes was distributed to farmers when there was high demand in growing season. In the case of fresh potatoes, supermarket chains had not played in any role so far since prices for potatoes are comparatively high at supermarkets. Hence, open air markets, small shops and retailers are important outlets.

Processing

The ware potatoes are processed into crisps and French fries. There are five potato chip enterprises that are famous and these products are distributed to the whole country. From chip producer interviews, they preferred high yielding varieties with the following attributes: long to oblong shape; large to medium size; yellow flesh color; shallow eyes; available throughout the year; long shelf-life; and minimum discolorations or oxidation after peeling. The variety Markies was the best to produce the chips that were marketable with small amount of chip in a package. The variety Carolus was also preferred by chip producers. In 2021, approximately 1.4% of the total potato production was taken for processing. The processing industry's fresh potato suppliers were smallholder farmers and traders. The top five chip producers had processed about 1,926 tons of potato per year into 423.72 tons of chips. Mary Cho enterprise had a market share of 85%. The 62% of potato chips was sold to the consumers and 38% to the Supermarket/City mart. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rise of popular online marketing of potato chips through online shops in the whole country.

Logistics

Limited storage facilities lead to considerable postharvest losses and produce deterioration, which ultimately affect selling prices. Potatoes are stored in general storage and cold storage. There are two cold storage warehouses in Southern Shan State. It is not enough compared with the production and its storage cost is relatively high. Only potato seeds for the next season are in cold storage of potato producer association for 3 to 7 months. All traders stored potatoes as ware potatoes and potato seeds in general warehouses. There is a demand of standard storage facilities for produce and commodity trading. Most of the current facilities in Myanmar are still in the basic stage and it needs to be upgraded to reduce and entirely eliminate wastage incurred by rodents and bad weather conditions.

The potatoes, grown in Southern Shan State, are transported to the Thirimalar wholesale market in Mandalay, the Bayintnaung wholesale market in Yangon daily and other townships especially Monywa, Kyaukpadaung, Myinchan by 12-wheeled trucks (90%) and public bus (10%).

Ware potato production constraints

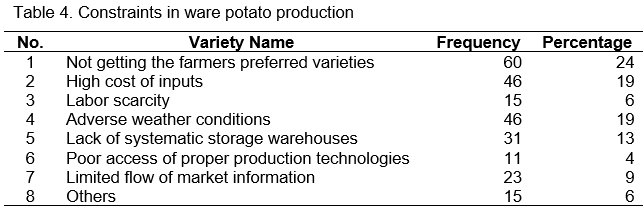

From farmers' interviews, they could not get their preferred varieties at sowing time; high cost of inputs (agrochemicals and fuel); labor scarcity causing increased labor cost; adverse weather conditions (frosting, flooding and drought); lack of systematic storage warehouse; poor access to proper production technologies; limited flow of market information and others (potatoes are stolen in the fields and there is a low level in knowledge sharing among organizational members).

Value chain constraints

The main constraints are lack of transparent pricing and contract farming for farmers. Most of the potato processing is just in the cottage industry stage. The processing industry is weakly developed in view of the rapidly urbanizing and more earning population.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATION

Engaging smallholders in value chains can generate benefits for smallholders as well as for buyers, suppliers and other actors in the value chain. In ware potato value chain, there were potato production, potato chip production, marketing and distribution. The potato production in 2020-2021 was decreased due to the high cost of production and low potato market price with bumper supply of China produced potatoes. The market participants involved in this value chain were potato producers’ organization, farmers, traders, wholesalers, retailers and potato processors. Among them, farmers and traders were the main participants along the chain. The farmers bought back the potato seeds stored in the traders' general warehouse at the planting time. Therefore, this shows that the farmers were facing the availability of potato seeds of demanded variety at the first rank of their constraints faced in ware potato production. There was no contract farming for potato farmers to secure the transparent market price. In Myanmar, the potato processing industry has been underdeveloped till now and can produce just only the potato chip.

Locally adapted varieties, tolerant or resistant to pests, drought, frost and heat for limited input production systems should be supplied urgently despite the fact that there was a project for potato sector improvement through the selection and promotion of locally adapted, demand-led potato varieties. Lowering cost of ware potato production and pumping efficiency in the value chain are critical. Efforts to produce and making the crop available for smallholder farmers with high quality potato seeds at affordable prices should be intensified. Potato farmers should also be allowed to benefit from the government subsidized fertilizer program. Efforts should be made to facilitate arbitrage through the development of storage and physical infrastructure. Lack of proper storage facilities in the farm level necessitates that farmers sell in order to avoid losses, and this leads to acceleration of intra-seasonal price instability. Government should create a favorable environment for agri-food businesses by providing basic infrastructure, creating the right market incentives, promoting inclusive agribusiness models, and supporting information and communications technology use that fosters inclusive value chains. These investments strengthen food supply links so that smallholder farmers have greater market access and other market participants can thrive. For enabling smallholder farmers engagement in dynamic value chain, policies and regulatory frameworks should ensure access to rural financing, training and technical assistance, and subsidy program for agrochemicals. The effective agricultural extension services of subject matter specialists should be conducted so that the farmers can be trained about the best crop management practices and cropping patterns. This can help farmers to follow the crop management practices like the use of fertilizers, improved seeds and to get the correct treatment for disease attacking their products and to have judicious use of available resources.

REFERENCES

De AK and Bhukta A. 1994. Marketing of potato in West Bengal: An economic view. Agril. Mar., 36(4): 36-44.

DoA. 2021. Data Records from Department of Agriculture (DOA), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

FAOSTAT (2019) Statistical database. Food and Agricultural Organization of United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy. www.fao.org/faostat/en

Hajong P., M. Moniruzzaman M, Mia MIA and Rahman MM. 2014 Storage system of potato in Bangladesh. Uni. J. Agrl. Res., 2(1): 11-17.

Hall C., J. Brooker, D. Eastwood, J. Epperson, E. Estes and T. Woods. 2006. A marketing systems approach to removing distribution barriers confronting small-volume fruit and vegetable growers. Choices 21(4):259-264.

Huq ASMA, S. Alam and S. Akter. 2004 Marketing efficiency of different channels for potato in selected areas of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Agric. Econs., 27(1): 67-79.

Njuki J., E. Kaganzi, S. Ferris, J. Barham, A. Abenakyo and P. Sanginga. 2008. Sustaining linkages to high value markets through collective action in Uganda, Food Policy 34 (2008) 23–30.

Potato Crop Sector and Value Chain of Ware Potato in Southern Shan State and Magway Region, Myanmar

ABSTRACT

Potato is an important cash crop for many farmers in the rural area of Myanmar and especially in the hilly region of Southern Shan State and riverbanks in the lowlands in Magway Region. The consumption of potatoes in curries, crisps and French fries increases substantially in the coming years offering opportunities for employment and income. The potato sector in Myanmar has huge potentials and can contribute to rural development. Because there is currently limited knowledge of the potato sector, there is a need for an inventory and a description of the actual situation, and an assessment of possible developments. This study gives a glimpse of the current status of the potato sector and the ware potato value chain. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from potato farmers, traders and chip producers as primary sources and the published reports as secondary one. The area of potato cultivation has been dropped in 2020 - 2021 because of suffering a loss last year due to facing soil problem, import of potato from external countries, especially China from border trade, rising of inputs costs, particularly potato seeds and fertilizers. The potato farmers used the Chinese variety, Netherlands variety, and Indian variety for ware potato production. Most farmers (58%) sold their ware potatoes directly from the field due to lack of storage facilities. The 78% of total ware potato production in the study areas was sold to traders through respective traders' agents or directly to processors while farmers saved 22% for next potato seeds stored in cold storage for 3-7 months. The 35% of ware potatoes was marketed to traders through agents and 54% to traders directly and 11% to chip producers. The ware potatoes from traders were sold to retailers (25%), wholesalers in other townships (33%), consumers (13%) and chip producers (4%), respectively. As informal potato seeds, the traders kept the small potatoes and distributed to farmers (25%) when there was high demand during the growing season. In 2021, approximately 1.4% of the total ware potato production was taken for processing. Government should create a favorable environment for agrifood businesses by providing basic infrastructure: cold storage, creating the right market incentives, promoting inclusive agribusiness models, and supporting the use of information and communications technology that fosters inclusive value chains. For enabling smallholder farmers engagement in dynamic value chain, policies and regulatory frameworks should ensure access to rural financing, training and technical assistance, and subsidy program for agrochemicals.

Keywords: ware potatoes, value chain, smallholder farmers, high yield variety, Myanmar

INTRODUCTION

Agriculture is the predominant economic activity in the rural areas of Myanmar, and smallholders make up the largest share of farmers. Agricultural value chains are organizational schemes enabling a primary product to get sold and transformed into consumable end products, adding value at each step of a gradual process of transformation and marketing. The smallholder farmers integrate in value chains as producers in the primary production segment supplying products to local buyers. Domestic markets are the primary markets for smallholder farmers in Myanmar and their importance in crop production is likely to grow.

The economic growth of any nation is dependent on the health of the community which is driven by the availability, and accessibility of food. In Myanmar, ware potato is one of the key components in the livelihood system of the farmers as cash crop. Potato is a calorie-dense nutritious vegetable and is considered the most important non cereal crop for its contribution towards food security. Potato has been introduced in the mid-19th century in Myanmar, where there is a large producer of potatoes in Southeast Asia. At present, ware potato is an important cash crop for many farmers in the rural areas of Myanmar, especially in the hilly region of Southern Shan State and riverbanks in the lowlands in Magway Region, Central dry zone.

With the expected growth of the economy and income per capita, the consumption of potatoes (in curries and processed: crisps, French fries) could increase substantially in the coming years. The changing recent market demand offers opportunities for employment and income. The ever-increasing demand of processed food as one of the consequences of changing eating habits such as snacking leads to the increment of potato processing as an emerging fast growing industry as well as providing more opportunity for entrepreneurship. The rapid growth in farmer engagement in potato production and market demand is attributed to rapid urban population growth, and changing food eating habits of urban dwellers. This has a strong impact on potato markets, creating opportunities for the smallholder farmers but also posing serious threats due to competition with larger suppliers of potatoes globally (Njuki et al.,2005). However, smallholder farmers use the small potatoes of the previous harvest as seed potato, resulting in heavily diseased low yielding crops.

Though the bumper production, the farmers were devoid of a good margin from their cultivated product. The growers sell their products immediately after harvesting due to weak storage facilities, ignorance about market price and cash needs (Hajong et al., 2014). Basically, this distressed sale occurred during peak production season. Along with this, some other risk factors such as potato chip producer preferences and priority, weather instability, storing infestation of diseases and so on helps to change the market situation rapidly (Hall et al., 2006) which also triggered farmers to sell their product immediately after harvest. Middlemen are waiting for this situation and buy potatoes from farmers and stored, then sold them in high pricing month. Due to the above circumstances, the consumers need to pay more money for buying the product but farmers share on this wages is very low. Such an inefficient marketing system does not assure a remunerative price to the farmers. These problems present most of the developing countries due to the presence of excessive number of intermediaries between producers and consumers (Huq et al., 2004) but their role in marketing cannot be demoralized (De and Bhukta, 1994).

The potato sector in Myanmar has great potentials and can contribute to rural development. Because there is currently limited knowledge of the potato sector, there is a need for an inventory and a description of the actual situation, and an assessment of its possible developments. On behalf of the seed potato project in 2012-2015, specific needs related to technology and knowhow of local potato growers on storage and mechanization have been identified. Agronomists can fulfill those needs and can contribute to the future development of the potato sector in Myanmar.

The objectives of this study are to:

- review the potato sector in Myanmar, in relation to areas of production and production volumes; and

- observe the current status of ware potato value chain.

METHODOLOGY

Study areas

Heho, sub-township of Kalaw Township, and Naungtayar Township are the first and second biggest potato-growing areas among townships in Southern Shan State. Sinphyukyun, sub-township of Salin Township, and Magway Township in Magway Region are also considered the largest potato-growing area in Central dry zone of Myanmar (DoA, 2021). Therefore, these townships were selected as the study areas.

Data collection

For the purpose of this study, qualitative and quantitative data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. The primary sources of data were mainly ware potato producers in the region and state. In addition to the primary data gathered from these sources, supplementary information from other secondary sources was also gathered from various published and unpublished documents. The main sources of secondary data include reports from different organizations like the Department of Planning (DoP), Department of Agriculture (DoA), Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics (DALMS).

The primary information pertaining to potato production in the year 2020-2021 was collected from 96 randomly sampled households, 7 traders and 5 potato chip producers in the areas using standardized questionnaire. In addition to data gathering using standardized questionnaire, informal interviews with key farmers were also conducted. Before the actual data collection, preliminary test was carried out that enabled some modification on the questionnaire afterwards. Based on this preliminary test, some questions that were found to be irrelevant or misleading were modified to fit the existing situation in the study area.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Potato production in Myanmar

Potato was cultivated in 16,215 ha in monsoon and 13,969 ha in winter with the total yield of 450,116 tons in 2020-2021 (DoA). Over the past period, the average potato yields in Myanmar have steadily increased up to 15 tons/ha but seem to stabilize for recent years (Figure 1). The area of potato cultivation has been dropped in 2020 - 2021 because the farmers suffered a loss last year due to facing soil problem, import of potato from external countries, especially China from border trade, rising of inputs costs, particularly potato seeds and fertilizers.

Production region

In Myanmar, potato is grown all-year round in 4 distinct seasons per region. This crop is grown on peaty and clay soils as an irrigated spring crop in rice paddies from January to April in Southern Shan State. This is a major crop with relatively high yields. It is as an early monsoon crop from April to August in the higher valleys (1,000-1,500 m above sea level) in the hilly regions of Shan State. This crop is rain-fed and is a minor crop during this season. As a late monsoon crop, potato is cultivated in the Southern Shan State from August to November. This is a major potato cropping season. The farmers cultivate this crop as a (minor) winter crop from November to February in the alluvial plains and irrigated crops in central Myanmar. The distribution of potato production of Myanmar by region is shown in Figure 2.

Export and import condition

Myanmar's potatoes exports are categorized in four respective HS code. These are fresh or chilled potatoes (excluding seeds); potatoes, prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid, frozen; potatoes, prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid (excluding frozen) and potatoes, uncooked or cooked by steaming or by boiling in water, frozen. However, among 4 exported categories, potatoes that are prepared or preserved otherwise than by vinegar or acetic acid, frozen, could not be exported from Myanmar.

In 2019-2020 budget year, potatoes were exported with a worth of US$ 0.259 million; it was a drop of 45% from the 2018-2019 budget year in which the total potatoes export was US$ 0.471 million. In value terms, Thailand remained the key foreign market for potato exports from Myanmar, comprising 81% of total exports. The second position in the ranking was occupied by Malaysia, with a 14% share of total exports. Myanmar potatoes had not been exported in the 2020-2021 budget year because trade has been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the current political situation.

The Netherlands constituted the largest supplier of potato to Myanmar, comprising 40% of the country’s total imports. The second position in the ranking was occupied by Malaysia, with an 18% share of total imports. It was followed by India, with a 17% share. The imported potatoes have been used as seed potatoes and the farmers prefer the seed potatoes from the Netherlands.

Ware potato value chain

Ware potato consumption

Potatoes produced in Myanmar are mainly used for fresh consumption and small-scale potato chips production. Therefore, the potatoes are entirely marketed for domestic consumption. Consumption can be estimated by total production because all potato production is locally consumed. The average annual potato consumption per capita was about 7.86 kg in 2019 (FAOSTAT). In urban areas where preference for potato French fries and chips increases due to changing lifestyles, the potato is greatly in demand by urban residents.

Potato is one of the major culinary crops in Myanmar. In the domestic market, potatoes are arranged by traders and consumers depend on the products which enter in the market centers/ wholesalers. It is hard for consumers to choose the best potatoes because no branding is done, and varieties are often mixed. Consumer quality awareness is only concerned on tuber size: the bigger the better. Potato production is highly pro-poor and contributes to food security of the growers and their families through substantial employment, income and nutritious food; and it has a great potential if the constraints are removed.

Varieties of ware potato grown by farmers

In 1982, the varieties from India were grown in Southern Shan State (Taungyi and Pintaya). Among these varieties, Up-to-Date (Sip-Po in local name) and CIP 24 became the most growing varieties for high yield in Kalaw township. In 2011, PepsiCo Trading and Capital Diamond Star Group introduced the Atlantic variety of potato for French fries production. Other varieties: Granola, Jelly, Waneta, Jacqueline Lee, Lamoka, Calwhite, Carolus, Markies, Manistee, Marabel and Rosagold were trial on farms for improvement of the potato sector in Myanmar with a project in 2014. Farmers had also grown Megachip, PO3, Defender, Sarpomira, and Rumba variety.

According to the result of survey data, the potato farmers have been using the variety Markies and Carolus introduced from the Netherlands, Lichu-6 from China, Kufri Jyoti from India in Southern Shan State and Magway Region. Some smallholder farmers grow the local variety, Mya Sein Ni. Last year, the farmers faced the Netherlands potato seed shortage due to trade disruption. Hence, they mostly used the Chinese variety, Lichu-6, imported from border area. It implies that the farmers are using any potato seeds available in the region through either imported by producer organization or saved by farmers/traders although they demanded the marketable existing varieties.

Marketing

Smallholder farmers sold ware potatoes at low farm gate prices, due to lack of storage facilities and unavailability of transportation services. Often they were forced to sell their products rapidly to cover for other needs and expenses. According to potato size, there were 6 grades: the lowest grade potato, A1, OK, S1, S2 and S3. Grade A1, OK and S1 potatoes were sold for home consumption and S2 and S3 for fried potato. As farmer saved potato seeds, OK and S1 were stored.

There was no evidence of collective marketing although the potato producer organizations exist. Regarding the analysis results, 58% of farmers could not store ware potatoes, and hence sold them directly from the field, leading to glut periods and low prices. Ware potato farmers were price takers despite supply and demand factors which determine the setting price. In Myanmar, seasonality in production makes farmers prone to exploitation by traders and agents. The 78% of total ware potato production in the study areas was sold to local traders through respective traders' agents or directly and to chip producers while farmers saved 22% for next potato seeds stored in cold storage for 3-7 months. The 35% of ware potatoes was marketed to traders through agents; 54 % directly to traders and 11% to chip producers. There are many different handlers in a vertical chain resulting in high transaction costs. From traders, the 25% of ware potatoes was sold to retailers; 33% transported to wholesalers in other townships; 13% to local consumers and 4% to potato chip producers. As an informal potato seed source, the traders kept the small ware potatoes and the 25% of ware potatoes was distributed to farmers when there was high demand in growing season. In the case of fresh potatoes, supermarket chains had not played in any role so far since prices for potatoes are comparatively high at supermarkets. Hence, open air markets, small shops and retailers are important outlets.

Processing

The ware potatoes are processed into crisps and French fries. There are five potato chip enterprises that are famous and these products are distributed to the whole country. From chip producer interviews, they preferred high yielding varieties with the following attributes: long to oblong shape; large to medium size; yellow flesh color; shallow eyes; available throughout the year; long shelf-life; and minimum discolorations or oxidation after peeling. The variety Markies was the best to produce the chips that were marketable with small amount of chip in a package. The variety Carolus was also preferred by chip producers. In 2021, approximately 1.4% of the total potato production was taken for processing. The processing industry's fresh potato suppliers were smallholder farmers and traders. The top five chip producers had processed about 1,926 tons of potato per year into 423.72 tons of chips. Mary Cho enterprise had a market share of 85%. The 62% of potato chips was sold to the consumers and 38% to the Supermarket/City mart. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rise of popular online marketing of potato chips through online shops in the whole country.

Logistics

Limited storage facilities lead to considerable postharvest losses and produce deterioration, which ultimately affect selling prices. Potatoes are stored in general storage and cold storage. There are two cold storage warehouses in Southern Shan State. It is not enough compared with the production and its storage cost is relatively high. Only potato seeds for the next season are in cold storage of potato producer association for 3 to 7 months. All traders stored potatoes as ware potatoes and potato seeds in general warehouses. There is a demand of standard storage facilities for produce and commodity trading. Most of the current facilities in Myanmar are still in the basic stage and it needs to be upgraded to reduce and entirely eliminate wastage incurred by rodents and bad weather conditions.

The potatoes, grown in Southern Shan State, are transported to the Thirimalar wholesale market in Mandalay, the Bayintnaung wholesale market in Yangon daily and other townships especially Monywa, Kyaukpadaung, Myinchan by 12-wheeled trucks (90%) and public bus (10%).

Ware potato production constraints

From farmers' interviews, they could not get their preferred varieties at sowing time; high cost of inputs (agrochemicals and fuel); labor scarcity causing increased labor cost; adverse weather conditions (frosting, flooding and drought); lack of systematic storage warehouse; poor access to proper production technologies; limited flow of market information and others (potatoes are stolen in the fields and there is a low level in knowledge sharing among organizational members).

Value chain constraints

The main constraints are lack of transparent pricing and contract farming for farmers. Most of the potato processing is just in the cottage industry stage. The processing industry is weakly developed in view of the rapidly urbanizing and more earning population.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATION

Engaging smallholders in value chains can generate benefits for smallholders as well as for buyers, suppliers and other actors in the value chain. In ware potato value chain, there were potato production, potato chip production, marketing and distribution. The potato production in 2020-2021 was decreased due to the high cost of production and low potato market price with bumper supply of China produced potatoes. The market participants involved in this value chain were potato producers’ organization, farmers, traders, wholesalers, retailers and potato processors. Among them, farmers and traders were the main participants along the chain. The farmers bought back the potato seeds stored in the traders' general warehouse at the planting time. Therefore, this shows that the farmers were facing the availability of potato seeds of demanded variety at the first rank of their constraints faced in ware potato production. There was no contract farming for potato farmers to secure the transparent market price. In Myanmar, the potato processing industry has been underdeveloped till now and can produce just only the potato chip.

Locally adapted varieties, tolerant or resistant to pests, drought, frost and heat for limited input production systems should be supplied urgently despite the fact that there was a project for potato sector improvement through the selection and promotion of locally adapted, demand-led potato varieties. Lowering cost of ware potato production and pumping efficiency in the value chain are critical. Efforts to produce and making the crop available for smallholder farmers with high quality potato seeds at affordable prices should be intensified. Potato farmers should also be allowed to benefit from the government subsidized fertilizer program. Efforts should be made to facilitate arbitrage through the development of storage and physical infrastructure. Lack of proper storage facilities in the farm level necessitates that farmers sell in order to avoid losses, and this leads to acceleration of intra-seasonal price instability. Government should create a favorable environment for agri-food businesses by providing basic infrastructure, creating the right market incentives, promoting inclusive agribusiness models, and supporting information and communications technology use that fosters inclusive value chains. These investments strengthen food supply links so that smallholder farmers have greater market access and other market participants can thrive. For enabling smallholder farmers engagement in dynamic value chain, policies and regulatory frameworks should ensure access to rural financing, training and technical assistance, and subsidy program for agrochemicals. The effective agricultural extension services of subject matter specialists should be conducted so that the farmers can be trained about the best crop management practices and cropping patterns. This can help farmers to follow the crop management practices like the use of fertilizers, improved seeds and to get the correct treatment for disease attacking their products and to have judicious use of available resources.

REFERENCES

De AK and Bhukta A. 1994. Marketing of potato in West Bengal: An economic view. Agril. Mar., 36(4): 36-44.

DoA. 2021. Data Records from Department of Agriculture (DOA), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar.

FAOSTAT (2019) Statistical database. Food and Agricultural Organization of United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy. www.fao.org/faostat/en

Hajong P., M. Moniruzzaman M, Mia MIA and Rahman MM. 2014 Storage system of potato in Bangladesh. Uni. J. Agrl. Res., 2(1): 11-17.

Hall C., J. Brooker, D. Eastwood, J. Epperson, E. Estes and T. Woods. 2006. A marketing systems approach to removing distribution barriers confronting small-volume fruit and vegetable growers. Choices 21(4):259-264.

Huq ASMA, S. Alam and S. Akter. 2004 Marketing efficiency of different channels for potato in selected areas of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Agric. Econs., 27(1): 67-79.

Njuki J., E. Kaganzi, S. Ferris, J. Barham, A. Abenakyo and P. Sanginga. 2008. Sustaining linkages to high value markets through collective action in Uganda, Food Policy 34 (2008) 23–30.