ABSTRACT

Agriculture is one of the backbone sectors in Malaysia’s economic development. The implementation of agriculture activities in Malaysia is guided by the medium-term master plan known as the Malaysian Development Plan. Malaysia has carried out 11 development plans since 1952. This article analyzes the performance of the agriculture sector during the 11th Malaysia Development Plan that covers a period between 2016 and 2020. In general, this sector experienced positive growth that indicates the positive effect of the strategies outlined in the master plan. The production of all agro-food commodities increased marginally due to low productivity. The production growth is smaller than the growth in demand. As a result, Malaysia still relies on the import of agro-food commodities from global markets. The Malaysian government aspires to transform its agriculture into a dynamic and progressive sector. The government sets new directions and introduces new strategies in the 12th Malaysian Development Plan that covers a period between 2021 and 2025.

Keywords: Malaysia development plan, agriculture sector, food security, sustainable agriculture

INTRODUCTION

The agriculture sector is the backbone of Malaysia's economy. This sector provides employment, generates income for the people, and generates revenue from exporting the commodities. The development of the agriculture sector is guided by its Medium-term planning called the Malaysian Development Plan. It is a road map that outlines the broad thrusts and strategies in the development agenda for the nation over the long term. It sets the macroeconomic framework and long-term targets to achieve the vision of the society (Vision, 2020). The development planning in Malaysia began in 1950, and until now, Malaysia has carried out 11 development plans. The current development plan is the 12th Malaysian Development Plan that covers 2021 and 2025.

The government published the statistics of all industries, including the agriculture sector, quite recently. The statistics revealed the implementation of the development plan and the outcome of the strategies in the master plan. This paper analyzes the statistics and discusses the performance of the agriculture sector during the Eleventh Malaysian Development Plan that covers a period between 2016 and 2020. The agriculture sector refers to the agriculture industries and agro-food sub-sector in the statistical report. This paper discusses the performance of the agro-food sub-sector. While the agriculture industry focuses on the country's wealth creation or income generation, the agro-food sub-sector focuses on food security and people's economy.

AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN THE 11TH MALAYSIAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN

The 11th Malaysian Development Plan (EMDP) covers the period between 2016 and 2020. The EMDP is very important because it marks the end of the 30 years of the Malaysia development plan under the National Vision 2020 agenda. It marks a momentous milestone as the next critical step in Malaysia's journey to becoming an advanced nation by 2020, as inspired by Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad in 1991. Malaysia aims to be a developed nation in all dimensions, including economically, politically, socially, spiritually, psychologically, and culturally by 2020. Under the EMDP, Malaysia aims to improve the quality of life of the people, which is reflected by an increase in per-capita income and the average household income. The EMDP was guided by the Malaysian National Development Strategy that focuses on rapidly delivering high-impact outcomes to both capital and people economy at affordable cost. The capital economy is about Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, big business, large investment projects, and financial markets. In contrast, people's economy is concerned with what matters the most to the people, including jobs, small businesses, the cost of living, family well-being, and social inclusion.

The EMDP focused on productivity and innovation as the pillars for developing the economy in Malaysia. It contains specific strategies and programs to improve productivity and transform innovation into wealth. The Malaysian government is aware that spurring productivity and innovation will provide the basis for sustained economic growth, create new economic opportunities, and ensure the people's continued well-being. Increasing productivity is one of the game-changers that will rapidly enhance the economy's development. Productivity growth will be achieved through innovation and technology adoption in all sectors. In this regard, the government gives the people's economy a higher priority. This effort ensures that all people will have a better quality of life. The EMDP outlines six strategic thrusts as follows:

- Enhancing inclusiveness towards an equitable society;

- Improving well-being for all;

- Accelerating human capital development for an advanced nation;

- Pursuing green growth for sustainability and resilience;

- Strengthening infrastructure to support economic expansion; and

- Re-engineering economic growth for greater prosperity.

In the EMDP, the government aimed to transform and modernize its agriculture into a high-income and sustainable sector. This sector is projected to grow at 3.5% per annum, contributing to 7.8% of its GDP in 2020. Industrial commodities will contribute 57.0% and agro-food 42.4% to the total agriculture value-added in 2020. Efforts are focused on ensuring food security, improving productivity, increasing the skills of farmers, fisherfolk, and smallholders, enhancing support and delivery services, strengthening the supply chain, and ensuring compliance with international market requirements. The sector's development will also take into account the impact of climate change on sustainable agriculture.

The government has identified seven strategies to speed up the growth of the agriculture sector, as follows:

- Improving productivity and income of farmers, fisherfolk, and smallholders by accelerating adoption of ICT and farming technology, preserving and optimizing agricultural land, and intensifying R&D&C in a priority area;

- Promoting training and youth agropreneur development through collaboration across agencies and the private sector to modernize farming techniques and nurture agribusiness start-ups;

- Strengthening institutional support and extension services by streaming extension services and encouraging advisory services from industry and academia;

- Building capacity of agricultural cooperatives and associations along the supply chain by vertically integrating the supply chain for selected crops, enhancing management skills, and pooling resources for promotion and exports;

- Improving market access and logistics support by strengthening logistics and enhancing access to domestic and international marketplaces;

- Scaling up access to agricultural financing by restructuring and providing a more flexible payment mechanism as well as increasing sustainability of financing mechanisms for replanting programs; and

- Intensifying performance-based incentive and certification programs by encouraging farmers to get certified and prioritizing certified farms for incentives and support.

The strategies for developing the agriculture sector outlined in the EMDP complements the National Agro-food Policy. The development of the agriculture sector was guided by the National Agro-food Policy (NAP), 2011-2020, and the National Commodity Policy, 2011-2020, which aimed to increase food production and exports of industrial commodities. The NAP was developed in 2010/2011 to improve the efficiency of the agro-food industry in Malaysia by driving productivity and competitiveness across the industry value chain. This NAP identified three objectives:

1. To ensure adequate food supply and safety;

2. To develop the agrofood industry into a competitive and sustainable industry; and

3. To increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs.

The government has identified 15 industries that will impact the development of the agriculture sector: i) paddy and rice, ii) capture fisheries, iii) livestock, iv) vegetables, v) fruits, vi) coconuts, vii) edible bird's nest, viii) aquaculture, ix) ornamental fishes, x) seaweed, xi) herbs and spices, xii) floriculture, xiii) mushrooms, xiv) agro-based food, and xv) agro-tourism. The government plans to transform these industries into a modern and progressive industry.

Performance of the agriculture sector

In general, this sector experienced positive growth since the inception of the National Agro-food Policy (NAP 2011-2020) in 2011, which indicates the positive effects of the NAP on the whole agro-food industry. This paper analyzes the five most important industries that could significantly impact food security. The industries are i) paddy and rice, ii) vegetables, iii) fruits, iv) fisheries, and v) livestock.

The GDP contribution of the agriculture sector remains relatively stable, within the range of 6% and 8%, but at a decreasing trend. Although the total production has increased from RM97.538 (US$23.2) billion in 2015 to more than RM107.313 (US$25.55) billion in 2020, the agriculture contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped from 8.90% to 7.17%, respectively. The compound’s annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2015 and 2020 also diminished to 1.93% compared to 2010-2015 at 3.09%. The agro-food sub-sector contributed around 48.20% of the agriculture GDP in 2020, valued at about RM51.530 (US$12.26) billion.

The contribution to the export has increased to RM36.479 (US$8.68) billion in 2020, from RM27.310 (US$6.50) billion in 2015, with an annual growth rate of 3.18%. The main contributor of export products is beverages and spices (26.03%), followed by processed food products (25.67%) and cereals and processed cereals (12.22%). At the same time, the import has also increased to RM57.697 (US$13.73) billion in 2020, from RM45.318 (US$10.79) billion in 2015, to make a more significant deficit in the balance of trade. The trade balance has surged to -RM21.218 (US$-5.05) billion in 2020, compared to -RM18.01 (US$4.29) in 2015.

During the EMDP, the number of people working in the agriculture sector has reduced by around 0.30%. More than 1.566 million people are working in the agriculture sector, or approximately 10.5% of the total workforce in Malaysia. In 2020, 484,520 people were working in the agro-food sub-sector. The workforce in the agro-food sector also dropped from 498,900 people in 2015. The yearly average growth between 2015 and 2020 was -1.41%.

Despite its importance as the food source, the agricultural land has reduced from 5.29 million hectares in 2017 to 5.26 million hectares in 2020, a reduction of around 0.58% or more than 30,000 hectares. Approximately 4.2 million hectares (80.69%) of arable land are used for industrial crops such as oil palm, cocoa, and the balance 900,000 hectares or 16.75% for agro-food industries. The competition in using land for lucrative industries has ended up with the losing side of the agriculture sector.

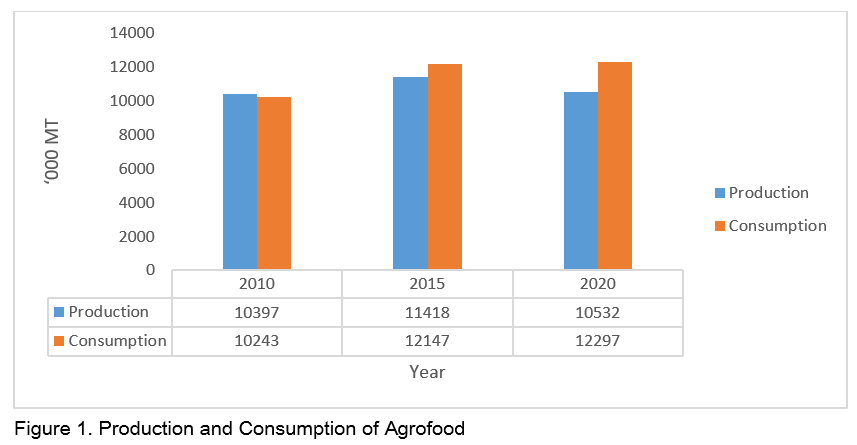

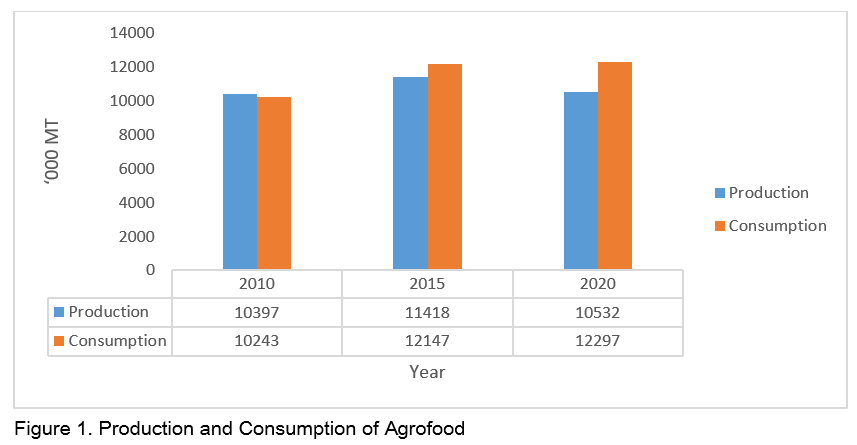

The production and consumption of major agro-food commodities show an increasing trend, with the production growth being lower than the consumption. The production of agro-food commodities increases around 0.13% compared with consumption (1.84%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows that the consumption growth of agro-food is greater than the production. In 2010, Malaysia produced 10.4 million tons (T) of agro-food, compared to 10.24 million tons of the consumption. Although the total production increased to 11.42 million tons in 2015, the total consumption increased to 12.14 million tons, and further increased to 12.30 million tons in 2020, overtaking the production by more than 1.76 million tons. Almost all commodities show a reduction in production. For example, the accumulative production growth rate between 2010 and 2020 indicates that rice has negative 0.48%, fruits (-0.5%), fish (-0.73%), and beef (-0.43%). Only chicken has indicated a positive growth of 2.48% and vegetables (1.45%).

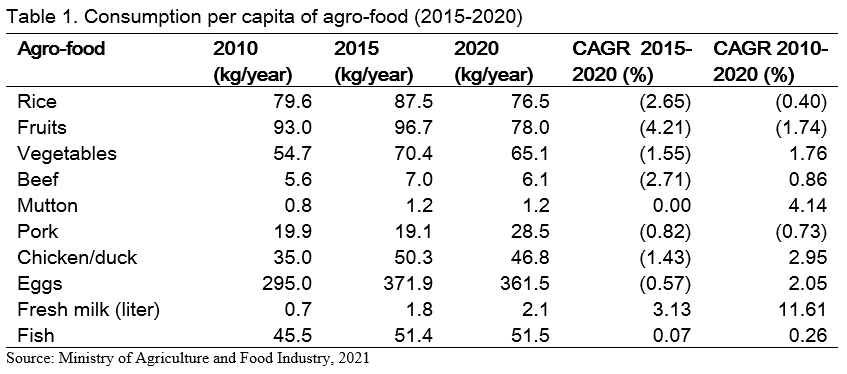

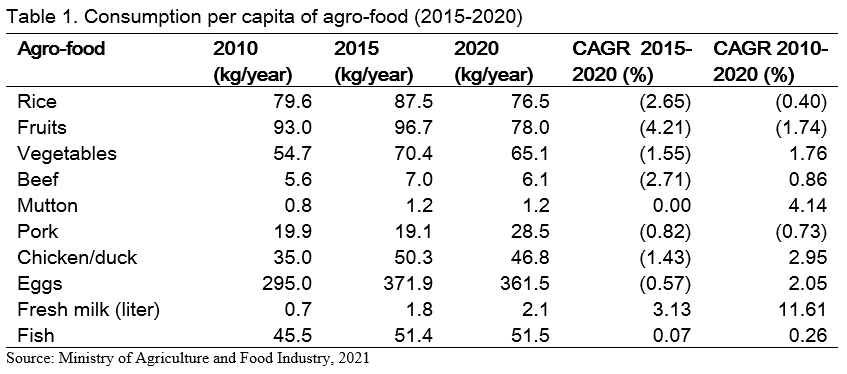

The increase in population is the main factor contributing to the higher consumption. The population of Malaysia has increased from 30.40 million people in 2015 to 32.37 million people in 2020. At the same time, changes in lifestyles and concerns about health have also changed the consumption pattern of agro-food products (Table 1).

Table 1 shows that, in general, the consumption per capita of most agro-food commodities has increased within 10 years (2010-2020). The protein-based food consumption has increased, while the carbohydrates foods have been reduced significantly. Consumption per capita has relatively decreased during the short-term of 2015 and 2020 due to more awareness about a healthy lifestyle.

Despite the increase in total production, the supply by local producers cannot meet the demand. As a result, Malaysia imports almost all types of agro-food products. Malaysia is the net importer of food. Malaysia imported more than RM57.7 (US$13.77) billion agro-food products in 2020, increasing from RM45.3 (US$10.79) billion in 2015. This situation indicated that Malaysia still relies on its food supply from global markets.

The following analysis focuses on the specific industry: paddy, fruits, vegetables, livestock, and fisheries. The analysis evaluates each industry's performance based on the three objectives identified in the National Agro-food Policy (2011-2020).

Objective 1: to ensure adequate food supply and safety

The government aims to increase food production so that supply in the country is sufficient for the growing demand. The government also aspires to provide more direct access between farmers and consumers to get better returns while the consumers enjoy affordable prices.

In general, the production of all commodities showed positive growth and met their production targets. However, the total production of most commodities is still unable to meet the demand of local consumers.

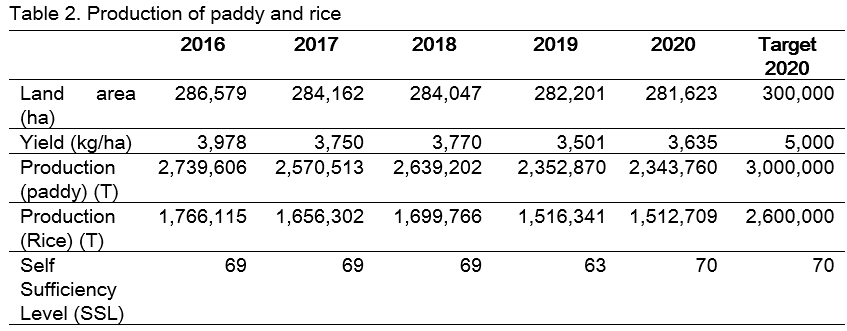

Paddy

Paddy production has dropped significantly from 2.74 million tons in 2016 to 2.34 million tons in 2020, a drop of around 14.4% in five years. The reduction of production is contributed by low productivity, which was dropped from 9.56 tons per hectare (2016) to 8.32 tons per hectare. Paddy production in Malaysia was carried out in 12 greenery areas and outside the greenery areas. Generally, the production productivity in greenery areas is higher than the outside. Paddy yield in the greenery area is around 4,414 kg per hectare, while the yield outside the greenery is around 4,008 kg per hectare.

On the other hand, the paddy yield in Sabah and Sarawak is further low, at around 2,914 kg and 1,844 kg per hectare, respectively. The low productivity in Sabah and Sarawak lowers Malaysia's average productivity. Post-harvest losses during the harvesting stage and pest attacks are two significant factors that lower the productivity of paddy. A study by MARDI revealed that around 28% of paddy yield was lost during harvesting, transporting, and processing in the factories.

Paddy production can only supply around 70% of the local demand; hence the self-sufficiency level (SSL) of paddy is 70%. Malaysia does not have the capability to produce 100% of its paddy. Malaysia exercises freedom of choice, where people can buy different rice varieties. Since the local farmers only produce white rice, Malaysia imports other rice commodities such as Basmati, Fragrance, and Japonica from other countries. Malaysia imports around 1.1 million tons of rice in 2020, mainly from Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, India, and Pakistan.

Three main factors that contributed to the lower performance of the paddy and rice industry in Malaysia:

- High production cost contributed by the high price of input and low yield per hectare. At the same time, small-scale production is not economic of scale. The average land area per farmer is 3.48 hectares;

- Low yield per hectare. The average yield per hectare is 3,496 kg, less than the target in the national agro-food policy, which is 5,000 kg/hectare; and

- Lack of mechanization and automation. Majority of farmers are still using traditional production, especially farmers outside the greenery areas.

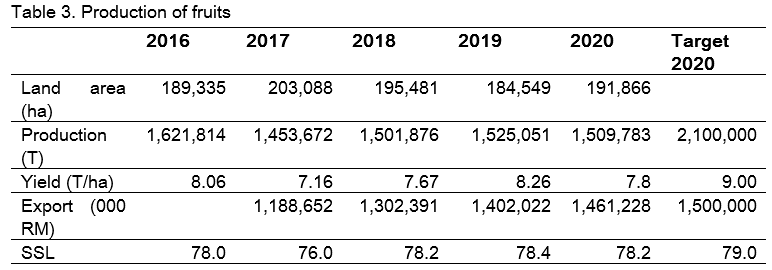

Fruits

In general, the fruit industry was unable to achieve the overall target of fruit production in 2020, which is 2.1 million tons. The fruit industry in Malaysia encountered an overall decline in production growth (-0.31%) between 2011 and 2020, which is contrary to 3.8% growth per year targeted under the National Agriculture Policy (2011-2020). The production of fruits dropped from 1.62 million tons in 2016 to 1.50 million tons in 2022. The target production of fruits was revised from 2.56 million tons to 2.10 million tons. At the same time, the average yield also decreased from 8.06 tons/hectare to 7.80 tons/hectare in the same period (Table 3).

The actual yield was also far below the target, 12.9 tons/hectare. Some factors contributing to a lower production are the replanting of fruit trees, especially durian that received a higher demand from China. Farmers are replanting their crops with a better variety of fruit that could be sold at premium price. The government also provided a special grant and subsidy in 2016 for farmers who wanted to replant their orchards with selected fruits recommended by the Department of Agriculture.

Table 3 shows that the land area for fruit production is stable at around 192,000 hectares. However, the production of fruits decreased on average about 1.3% every year. At the same time, the value of export has increased to RM1.46 (US$0.347) billion in 2020, a significant contribution to the total export of agricultural products. During the EMDP, the self-sufficiency level of fruits declined to 78.2% in 2020, from 83.7% in 2010. The lower SSL indicated that Malaysia needs to import more fruits from global markets to meet the consumers' demand.

Vegetables

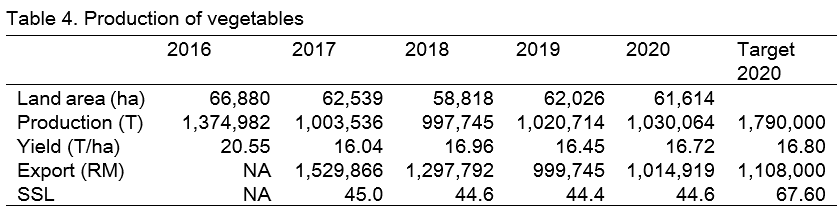

The growth of local vegetable production has been inconsistent since 2006 when the domestic production falls below consumption. The production of vegetables reduced to 1.03 million tons in 2020, from 1.37 million tons in 2010, far below the target set in the national Agrofood Policy, which is 1.79 million tons (Table 4). The government projected that the consumption would reach around 2.48 million tons. Thus, the deficit between production and consumption has enlarged to 1.45 million tons, compared to the projection of a shortage of only 0.69 million tons, which will come from global market sources. The higher consumption than the production has resulted in higher import of vegetables. Malaysia imported more than 1.81 million tons of vegetables, mainly temperate products, in 2020.

Table 4 shows that the productivity of vegetables is stable at 16.0 tons/hectare. The application of technology in vegetable production is the main factor for the higher productivity of vegetables in Malaysia. The table also shows that the export value of vegetables has decreased from 2017 to 2020. Malaysia exports most of its vegetables to Singapore. The competition with other countries such as Indonesia and China has reduced the import from Malaysia by Singapore.

Fisheries

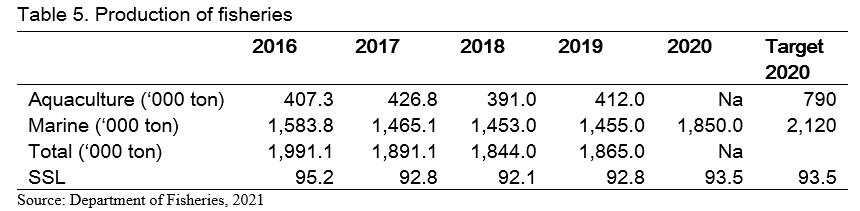

In general, fisheries in Malaysia consist of two sub-industries: inland, aquaculture, and marine. Marine fish contributed about 76% of the total fish supply in Malaysia. The Malaysian fisheries industry has produced 1.86 million tons production, estimated at US$3.3 billion (RM14.5 billion) in 2019. Since 2016, food fish landing has encountered an overall decrease in growth. The total fish landed decreased from 1.99 million tons in 2016 to 1.85 million tons in 2020. Despite indicating a positive trend in landing, the figure is still below the NAP targeted average annual growth rate of 4%. The actual landing is approximately 92.0% of the forecast of 2.12 million tons in 2020. However, the total production can supply approximately 93.51% of the local demand, achieving the NAP target. The government aspires to increase marine fish production by increasing the catchment of deep-sea fish from 1.32 million tons in 2010 to 1.76 million tons in 2020. The data shows that this aspiration was achieved significantly where marine fish production achieved the target in 2020.

With a growing population and an increasing preference for fish as a healthy source of animal protein, it has been estimated that the annual demand for fish will increase to 1.7 million tons in 2011 and further to 1.93 million tons by 2020. Based on the projection written in the NAP, the actual production achieved the total demand of the fishery products in 2020.

Livestock

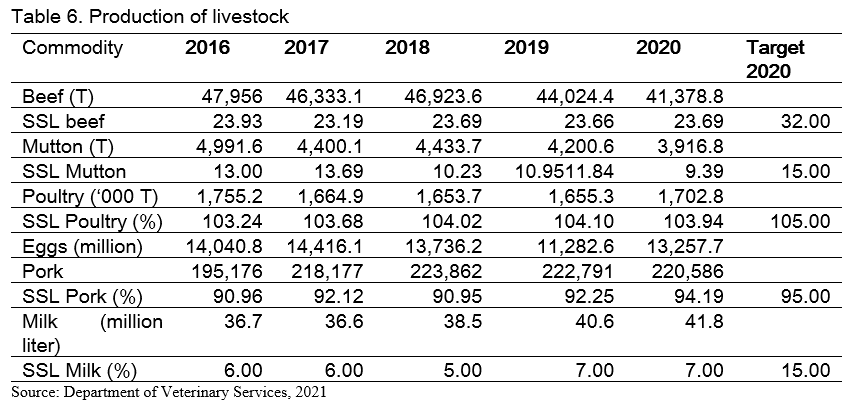

Livestock is one of the important sources of protein in Malaysia. In general, livestock is divided into two categories: ruminants and non-ruminants. The production of meat and meat-based products increases every year. Meat production increased from 1.6 million tons in 2010 and is projected to achieve 2.1 million tons in 2020, with a growth of 2.7% per year. At the same time, the consumption is projected to increase to 1.8 million in 2020.

In general, the production of meat products is decreasing every year, except pork. For example, beef production has dropped from 47,960 tons in 2016 to 41,380 tons in 2020. The local production can only supply around 24% of the local demand. This figure indicates that the livestock industry generally also does not perform as expected in the National Agrofood Policy, which is targeted to achieve at least 32% of the SSL. Due to the low production of beef meat locally, the industry is forced to rely highly on imported beef, contributing to the high trade deficit. The inconsistency of local beef production is mainly affected by the cost of production.

Consumers in Malaysia prefer to eat less mutton. The consumption per capita of mutton is stable at 1.2 kg per person per year between 2015 and 2020. The mutton production dropped from nearly 5,000 tons in 2016 to almost 4,000 tons in 2020 but did not affect the demand much.

On the other hand, poultry is the most established segment under the livestock industry and the cheapest source of protein in Malaysia. The poultry meat production also decreased from 1.75 million tons in 2016 to 1.70 million tons in 2020. Despite drop in production, the supply is more than sufficient for local consumers. Table 6 shows that only poultry meat surpasses consumption (the supply is more than the demand). The consumption per capita for poultry has decreased from 56.5 kg in 2015 to 53.6 kg in 2020. As a result, the SSL for chicken was also reduced from 113.6% in 2015 to 105.4% in 2020. The excess supply of chicken enables Malaysia to export its products, primarily to Singapore. Malaysia exports more than 40,000 tons of poultry and poultry-based products to global marketplaces every year.

The NAP has targeted pork meat production to reduce by 0.8% annually; however, the production increased from 195,200 tons in 2016 to more than 220,000 tons in 2020. In addition, pork production is relatively consistent, almost equivalent to consumption. The production in 2020, however, is still below the target of 230,500 tons, or 94% of the SSL. The short supply will be imported from other countries.

Overall, milk production can only satisfy around 7.00% of total local demand, indicating high reliance on imported milk. Production of milk is stable at approximately 38 - 42 million liter every year. Thus, milk production has not been able to meet its NAP targets in 2020.

Objective 2: To develop the agro-food industry into a competitive and sustainable industry

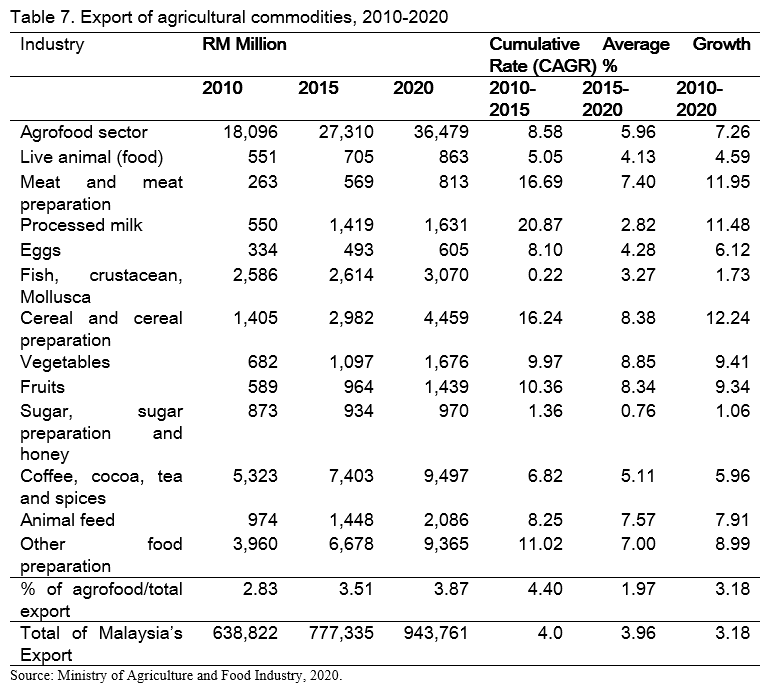

Malaysia is a trading nation. Malaysia is the 27th most competitive nation globally out of 140 countries ranked in the 2018 edition of the Global Competitiveness Report published by the World Economic Forum. The Malaysian economy is driven by the import and export of finished products for local consumption or processing and repackaging for exports. The import and export of agro-food products are determined by the competitiveness of the local industry. Malaysia will export its agro-food products if the price is more competitive than the other countries that produce the same agro-food. At the same time, the local consumers will buy local products if the price is lower than the imported products. The export of the agro-food products is presented in Table 7.

Table 7 shows that the export of agricultural and processed products is increasing every year, indicating that Malaysia’s industry is sustainable and remains competitive in the global market. The export for the agro-food sector increased from RM18.1 (US$4.31) billion in 2010 to more than RM36.4 (US$8.67) billion in 2020, with the cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) about 7.26% in 10 years. Beverages and spices products contributed the most significant export value, while meat preparation, processed milk, and cereal preparation grew substantially in ten years. These figures indicate that global markets well accept Malaysia’s agro-food products.

Despite relying upon most agro-food commodities from other countries, Malaysia has a competitive advantage in its processing capability. Malaysia imports raw materials from neighboring countries, processes them and re-exports them to other countries. For example, Malaysia imported more than 100 million liters of milk from New Zealand, processed it, and re-export to other countries. The trading activities generate more than RM1.6 (US$0.38) billion in revenue to Malaysia.

Objective 3: To increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs

The third objective of the National Agro-food Policy (2011-2020) is to increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs. This policy aims to sustain the number of people working in this sector. This policy is essential because other sectors offer better financial opportunities and conducive working environment. Statistics show that the workforce in the agro-food sector has reduced from 535,700 people in 2010 to 484,520 people in 2020. The involvement of the workforce in agro-food compared to the country's total workforce also decreased from 4.50% to 3.21%.

Currently, no official data were published to indicate the income level of the agricultural entrepreneurs in Malaysia. The last national census on the demographic profile of the agriculture sector was carried out in 2016. In general, the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs increases marginally. Most of the industry received subsidies from the government, such as production subsidy for paddy and vegetable, price subsidy (floor price) for vegetables and fruit, petrol and diesel subsidy for the fisheries industry. The agricultural entrepreneurs also receive many incentives from the government that can be considered additional income for them.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

In general, the agriculture sector in Malaysia was affected by global and regional economic trends. For example, the supply of agricultural products in the world has increased significantly between 2000 and 2020. According to the statistic by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2021, the agriculture value-added has increased around 67% between 2000 and 2018 to around US$3.4 trillion, while the share of agriculture in global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) went up around 4% in 2020, compared to 2000. The total production of primary crops increased by 50% between 2000 and 2018, to 9.1 billion tons. According to the report, about one-third of the produce is contributed by cereals, followed by sugar (24%) and vegetables (12%). Vegetable oil production increased 108% between 2000 and 2017, while meat production increased more than 47% to around 342 million tons.

The monetary value of global food exports has increased to around US$1.4 trillion in 2018, compared to about US$380 billion in 2000. Fruits and vegetables accounted for 23% of the total food export value in 2018, followed by cereals and preparations (14%), fish, and meat (11%). The global food prices have moderated in the past five years, given the adoption of more policies in favor of food security. The higher supply of agro-food products affected agro-food production in Malaysia because the cost of production is relatively higher, and it is cheaper to buy the products from global marketplaces.

From the local perspective, the depreciation of the Malaysian Ringgit has contributed to a higher cost of production. For example, the value of the Malaysian Ringgit has depreciated to RM4.50 for US$1.0 in 2017 compared to RM2.90 in 2012. The prices of fertilizers, animal feeds, and agricultural machinery have increased and affected Malaysia's production cost.

Nonetheless, several key issues impede the sustainable growth of the agro-food industry. These issues are categorized into several themes, namely:

- High reliance on imported agriculture inputs, which would impact the stability of food supply and food price;

- Competition for land which requires alternative strategies to be developed for obtaining higher agro-food productivity;

- Reliance on manual labor with insufficient knowledge on post-harvest handling methods, which lead to relatively high post-harvest losses at farm level;

- Predominance of middlemen as a result of continuous reliance by farmers and this contributes to the disparity between the farm gate (ex-farm) and consumer price;

- Relatively low compliance with international standards and quality accreditation, affecting the marketability of local agro-food-based products;

- Lack of sufficient and efficient logistics and infrastructure which affects the marketability and brand image of the local produce;

- Low interest among the young generation that has an impact on the sustainable development of the local agri-food industry;

- Majority of existing industry players are small-scale and are scattered across the country, limiting the potential of achieving benefits from large-scale farming and resulting in a higher operational cost;

- Less effective enforcement and monitoring which contributes to issues such as smuggling at the borders; and

- Limitation in stock data which is crucial to provide relevant agencies in having a clear and accurate picture while charting the future growth for the agro-food industry.

WAY FORWARD

The 12th Malaysian Development Plan replaced the 11th Malaysian Development Plan. The Malaysian government has identified new directions and strategies that can spearhead the development of the agriculture sector in Malaysia. The 12th development plan is the first part of Malaysia's ten-year plan, 2021-2030. This long-term plan aspires to balance the development of the economy with income distribution and people's well-being.

Under the 12th Malaysian Development Plan, the agriculture sector is projected to grow around 3.8% every year and contribute about 7.0% to the Good Domestic Product (GDP). The application of technology will enhance the development growth of this sector. The emphasis is to speed up the transformation of this sector to be a modern, dynamic and competitive sector supported by research, development, commercialization, and innovation (R&D&C&I).

In addition, strategies and initiatives under the National Food Securities Framework and National Agro-food Policy 2021-2030 will be implemented to achieve the sufficiency of food supply and comply with international food safety standards. The use of biomass and biogas will also be optimized. Development of agri-commodity entrepreneurs for specialized products will be encouraged to diversify its products with a high added value.

REFERENCE

Department of Prime Minister (2021). 12th Malaysia Development Plan: prosperous, Sustainable and Inclusive. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department. Kuala Lumpur.

Department of Prime Minster (2015). Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020: Anchoring growth on people. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department. Kuala Lumpur.

Fisheries Department Malaysia (2021). Statistic of landed fish in Malaysia 2021. Strategic Planning Unit, Fisheries Department Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur.

Jabatan Pertanian Malaysia (2021). Booklet Statistik tanaman 2021. Sub-sektor tanaman makanan. (Department of Agriculture Malaysia (2021). booklet sub-sector food crops)

Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Makanan (2020). Dasar Agromakanan Negara 2.0: Permodenan agromakanan: Menjamin masa depan sekuriti makanan negra (Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (2020). National Agrofood Policy 2.0: Modernization of agrofood: Ensuring the future food security).

Veterinary Services Department (2021). Statistics of Livestock Malaysia (2021). Strategic Planning Unit, Veterinary Services Department, Kuala Lumpur.

Overview of the Agriculture Sector during the 11th Malaysian Development Plan (2016-2020)

ABSTRACT

Agriculture is one of the backbone sectors in Malaysia’s economic development. The implementation of agriculture activities in Malaysia is guided by the medium-term master plan known as the Malaysian Development Plan. Malaysia has carried out 11 development plans since 1952. This article analyzes the performance of the agriculture sector during the 11th Malaysia Development Plan that covers a period between 2016 and 2020. In general, this sector experienced positive growth that indicates the positive effect of the strategies outlined in the master plan. The production of all agro-food commodities increased marginally due to low productivity. The production growth is smaller than the growth in demand. As a result, Malaysia still relies on the import of agro-food commodities from global markets. The Malaysian government aspires to transform its agriculture into a dynamic and progressive sector. The government sets new directions and introduces new strategies in the 12th Malaysian Development Plan that covers a period between 2021 and 2025.

Keywords: Malaysia development plan, agriculture sector, food security, sustainable agriculture

INTRODUCTION

The agriculture sector is the backbone of Malaysia's economy. This sector provides employment, generates income for the people, and generates revenue from exporting the commodities. The development of the agriculture sector is guided by its Medium-term planning called the Malaysian Development Plan. It is a road map that outlines the broad thrusts and strategies in the development agenda for the nation over the long term. It sets the macroeconomic framework and long-term targets to achieve the vision of the society (Vision, 2020). The development planning in Malaysia began in 1950, and until now, Malaysia has carried out 11 development plans. The current development plan is the 12th Malaysian Development Plan that covers 2021 and 2025.

The government published the statistics of all industries, including the agriculture sector, quite recently. The statistics revealed the implementation of the development plan and the outcome of the strategies in the master plan. This paper analyzes the statistics and discusses the performance of the agriculture sector during the Eleventh Malaysian Development Plan that covers a period between 2016 and 2020. The agriculture sector refers to the agriculture industries and agro-food sub-sector in the statistical report. This paper discusses the performance of the agro-food sub-sector. While the agriculture industry focuses on the country's wealth creation or income generation, the agro-food sub-sector focuses on food security and people's economy.

AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN THE 11TH MALAYSIAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN

The 11th Malaysian Development Plan (EMDP) covers the period between 2016 and 2020. The EMDP is very important because it marks the end of the 30 years of the Malaysia development plan under the National Vision 2020 agenda. It marks a momentous milestone as the next critical step in Malaysia's journey to becoming an advanced nation by 2020, as inspired by Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad in 1991. Malaysia aims to be a developed nation in all dimensions, including economically, politically, socially, spiritually, psychologically, and culturally by 2020. Under the EMDP, Malaysia aims to improve the quality of life of the people, which is reflected by an increase in per-capita income and the average household income. The EMDP was guided by the Malaysian National Development Strategy that focuses on rapidly delivering high-impact outcomes to both capital and people economy at affordable cost. The capital economy is about Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, big business, large investment projects, and financial markets. In contrast, people's economy is concerned with what matters the most to the people, including jobs, small businesses, the cost of living, family well-being, and social inclusion.

The EMDP focused on productivity and innovation as the pillars for developing the economy in Malaysia. It contains specific strategies and programs to improve productivity and transform innovation into wealth. The Malaysian government is aware that spurring productivity and innovation will provide the basis for sustained economic growth, create new economic opportunities, and ensure the people's continued well-being. Increasing productivity is one of the game-changers that will rapidly enhance the economy's development. Productivity growth will be achieved through innovation and technology adoption in all sectors. In this regard, the government gives the people's economy a higher priority. This effort ensures that all people will have a better quality of life. The EMDP outlines six strategic thrusts as follows:

In the EMDP, the government aimed to transform and modernize its agriculture into a high-income and sustainable sector. This sector is projected to grow at 3.5% per annum, contributing to 7.8% of its GDP in 2020. Industrial commodities will contribute 57.0% and agro-food 42.4% to the total agriculture value-added in 2020. Efforts are focused on ensuring food security, improving productivity, increasing the skills of farmers, fisherfolk, and smallholders, enhancing support and delivery services, strengthening the supply chain, and ensuring compliance with international market requirements. The sector's development will also take into account the impact of climate change on sustainable agriculture.

The government has identified seven strategies to speed up the growth of the agriculture sector, as follows:

The strategies for developing the agriculture sector outlined in the EMDP complements the National Agro-food Policy. The development of the agriculture sector was guided by the National Agro-food Policy (NAP), 2011-2020, and the National Commodity Policy, 2011-2020, which aimed to increase food production and exports of industrial commodities. The NAP was developed in 2010/2011 to improve the efficiency of the agro-food industry in Malaysia by driving productivity and competitiveness across the industry value chain. This NAP identified three objectives:

1. To ensure adequate food supply and safety;

2. To develop the agrofood industry into a competitive and sustainable industry; and

3. To increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs.

The government has identified 15 industries that will impact the development of the agriculture sector: i) paddy and rice, ii) capture fisheries, iii) livestock, iv) vegetables, v) fruits, vi) coconuts, vii) edible bird's nest, viii) aquaculture, ix) ornamental fishes, x) seaweed, xi) herbs and spices, xii) floriculture, xiii) mushrooms, xiv) agro-based food, and xv) agro-tourism. The government plans to transform these industries into a modern and progressive industry.

Performance of the agriculture sector

In general, this sector experienced positive growth since the inception of the National Agro-food Policy (NAP 2011-2020) in 2011, which indicates the positive effects of the NAP on the whole agro-food industry. This paper analyzes the five most important industries that could significantly impact food security. The industries are i) paddy and rice, ii) vegetables, iii) fruits, iv) fisheries, and v) livestock.

The GDP contribution of the agriculture sector remains relatively stable, within the range of 6% and 8%, but at a decreasing trend. Although the total production has increased from RM97.538 (US$23.2) billion in 2015 to more than RM107.313 (US$25.55) billion in 2020, the agriculture contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped from 8.90% to 7.17%, respectively. The compound’s annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2015 and 2020 also diminished to 1.93% compared to 2010-2015 at 3.09%. The agro-food sub-sector contributed around 48.20% of the agriculture GDP in 2020, valued at about RM51.530 (US$12.26) billion.

The contribution to the export has increased to RM36.479 (US$8.68) billion in 2020, from RM27.310 (US$6.50) billion in 2015, with an annual growth rate of 3.18%. The main contributor of export products is beverages and spices (26.03%), followed by processed food products (25.67%) and cereals and processed cereals (12.22%). At the same time, the import has also increased to RM57.697 (US$13.73) billion in 2020, from RM45.318 (US$10.79) billion in 2015, to make a more significant deficit in the balance of trade. The trade balance has surged to -RM21.218 (US$-5.05) billion in 2020, compared to -RM18.01 (US$4.29) in 2015.

During the EMDP, the number of people working in the agriculture sector has reduced by around 0.30%. More than 1.566 million people are working in the agriculture sector, or approximately 10.5% of the total workforce in Malaysia. In 2020, 484,520 people were working in the agro-food sub-sector. The workforce in the agro-food sector also dropped from 498,900 people in 2015. The yearly average growth between 2015 and 2020 was -1.41%.

Despite its importance as the food source, the agricultural land has reduced from 5.29 million hectares in 2017 to 5.26 million hectares in 2020, a reduction of around 0.58% or more than 30,000 hectares. Approximately 4.2 million hectares (80.69%) of arable land are used for industrial crops such as oil palm, cocoa, and the balance 900,000 hectares or 16.75% for agro-food industries. The competition in using land for lucrative industries has ended up with the losing side of the agriculture sector.

The production and consumption of major agro-food commodities show an increasing trend, with the production growth being lower than the consumption. The production of agro-food commodities increases around 0.13% compared with consumption (1.84%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows that the consumption growth of agro-food is greater than the production. In 2010, Malaysia produced 10.4 million tons (T) of agro-food, compared to 10.24 million tons of the consumption. Although the total production increased to 11.42 million tons in 2015, the total consumption increased to 12.14 million tons, and further increased to 12.30 million tons in 2020, overtaking the production by more than 1.76 million tons. Almost all commodities show a reduction in production. For example, the accumulative production growth rate between 2010 and 2020 indicates that rice has negative 0.48%, fruits (-0.5%), fish (-0.73%), and beef (-0.43%). Only chicken has indicated a positive growth of 2.48% and vegetables (1.45%).

The increase in population is the main factor contributing to the higher consumption. The population of Malaysia has increased from 30.40 million people in 2015 to 32.37 million people in 2020. At the same time, changes in lifestyles and concerns about health have also changed the consumption pattern of agro-food products (Table 1).

Table 1 shows that, in general, the consumption per capita of most agro-food commodities has increased within 10 years (2010-2020). The protein-based food consumption has increased, while the carbohydrates foods have been reduced significantly. Consumption per capita has relatively decreased during the short-term of 2015 and 2020 due to more awareness about a healthy lifestyle.

Despite the increase in total production, the supply by local producers cannot meet the demand. As a result, Malaysia imports almost all types of agro-food products. Malaysia is the net importer of food. Malaysia imported more than RM57.7 (US$13.77) billion agro-food products in 2020, increasing from RM45.3 (US$10.79) billion in 2015. This situation indicated that Malaysia still relies on its food supply from global markets.

The following analysis focuses on the specific industry: paddy, fruits, vegetables, livestock, and fisheries. The analysis evaluates each industry's performance based on the three objectives identified in the National Agro-food Policy (2011-2020).

Objective 1: to ensure adequate food supply and safety

The government aims to increase food production so that supply in the country is sufficient for the growing demand. The government also aspires to provide more direct access between farmers and consumers to get better returns while the consumers enjoy affordable prices.

In general, the production of all commodities showed positive growth and met their production targets. However, the total production of most commodities is still unable to meet the demand of local consumers.

Paddy

Paddy production has dropped significantly from 2.74 million tons in 2016 to 2.34 million tons in 2020, a drop of around 14.4% in five years. The reduction of production is contributed by low productivity, which was dropped from 9.56 tons per hectare (2016) to 8.32 tons per hectare. Paddy production in Malaysia was carried out in 12 greenery areas and outside the greenery areas. Generally, the production productivity in greenery areas is higher than the outside. Paddy yield in the greenery area is around 4,414 kg per hectare, while the yield outside the greenery is around 4,008 kg per hectare.

On the other hand, the paddy yield in Sabah and Sarawak is further low, at around 2,914 kg and 1,844 kg per hectare, respectively. The low productivity in Sabah and Sarawak lowers Malaysia's average productivity. Post-harvest losses during the harvesting stage and pest attacks are two significant factors that lower the productivity of paddy. A study by MARDI revealed that around 28% of paddy yield was lost during harvesting, transporting, and processing in the factories.

Paddy production can only supply around 70% of the local demand; hence the self-sufficiency level (SSL) of paddy is 70%. Malaysia does not have the capability to produce 100% of its paddy. Malaysia exercises freedom of choice, where people can buy different rice varieties. Since the local farmers only produce white rice, Malaysia imports other rice commodities such as Basmati, Fragrance, and Japonica from other countries. Malaysia imports around 1.1 million tons of rice in 2020, mainly from Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, India, and Pakistan.

Three main factors that contributed to the lower performance of the paddy and rice industry in Malaysia:

Fruits

In general, the fruit industry was unable to achieve the overall target of fruit production in 2020, which is 2.1 million tons. The fruit industry in Malaysia encountered an overall decline in production growth (-0.31%) between 2011 and 2020, which is contrary to 3.8% growth per year targeted under the National Agriculture Policy (2011-2020). The production of fruits dropped from 1.62 million tons in 2016 to 1.50 million tons in 2022. The target production of fruits was revised from 2.56 million tons to 2.10 million tons. At the same time, the average yield also decreased from 8.06 tons/hectare to 7.80 tons/hectare in the same period (Table 3).

The actual yield was also far below the target, 12.9 tons/hectare. Some factors contributing to a lower production are the replanting of fruit trees, especially durian that received a higher demand from China. Farmers are replanting their crops with a better variety of fruit that could be sold at premium price. The government also provided a special grant and subsidy in 2016 for farmers who wanted to replant their orchards with selected fruits recommended by the Department of Agriculture.

Table 3 shows that the land area for fruit production is stable at around 192,000 hectares. However, the production of fruits decreased on average about 1.3% every year. At the same time, the value of export has increased to RM1.46 (US$0.347) billion in 2020, a significant contribution to the total export of agricultural products. During the EMDP, the self-sufficiency level of fruits declined to 78.2% in 2020, from 83.7% in 2010. The lower SSL indicated that Malaysia needs to import more fruits from global markets to meet the consumers' demand.

Vegetables

The growth of local vegetable production has been inconsistent since 2006 when the domestic production falls below consumption. The production of vegetables reduced to 1.03 million tons in 2020, from 1.37 million tons in 2010, far below the target set in the national Agrofood Policy, which is 1.79 million tons (Table 4). The government projected that the consumption would reach around 2.48 million tons. Thus, the deficit between production and consumption has enlarged to 1.45 million tons, compared to the projection of a shortage of only 0.69 million tons, which will come from global market sources. The higher consumption than the production has resulted in higher import of vegetables. Malaysia imported more than 1.81 million tons of vegetables, mainly temperate products, in 2020.

Table 4 shows that the productivity of vegetables is stable at 16.0 tons/hectare. The application of technology in vegetable production is the main factor for the higher productivity of vegetables in Malaysia. The table also shows that the export value of vegetables has decreased from 2017 to 2020. Malaysia exports most of its vegetables to Singapore. The competition with other countries such as Indonesia and China has reduced the import from Malaysia by Singapore.

Fisheries

In general, fisheries in Malaysia consist of two sub-industries: inland, aquaculture, and marine. Marine fish contributed about 76% of the total fish supply in Malaysia. The Malaysian fisheries industry has produced 1.86 million tons production, estimated at US$3.3 billion (RM14.5 billion) in 2019. Since 2016, food fish landing has encountered an overall decrease in growth. The total fish landed decreased from 1.99 million tons in 2016 to 1.85 million tons in 2020. Despite indicating a positive trend in landing, the figure is still below the NAP targeted average annual growth rate of 4%. The actual landing is approximately 92.0% of the forecast of 2.12 million tons in 2020. However, the total production can supply approximately 93.51% of the local demand, achieving the NAP target. The government aspires to increase marine fish production by increasing the catchment of deep-sea fish from 1.32 million tons in 2010 to 1.76 million tons in 2020. The data shows that this aspiration was achieved significantly where marine fish production achieved the target in 2020.

With a growing population and an increasing preference for fish as a healthy source of animal protein, it has been estimated that the annual demand for fish will increase to 1.7 million tons in 2011 and further to 1.93 million tons by 2020. Based on the projection written in the NAP, the actual production achieved the total demand of the fishery products in 2020.

Livestock

Livestock is one of the important sources of protein in Malaysia. In general, livestock is divided into two categories: ruminants and non-ruminants. The production of meat and meat-based products increases every year. Meat production increased from 1.6 million tons in 2010 and is projected to achieve 2.1 million tons in 2020, with a growth of 2.7% per year. At the same time, the consumption is projected to increase to 1.8 million in 2020.

In general, the production of meat products is decreasing every year, except pork. For example, beef production has dropped from 47,960 tons in 2016 to 41,380 tons in 2020. The local production can only supply around 24% of the local demand. This figure indicates that the livestock industry generally also does not perform as expected in the National Agrofood Policy, which is targeted to achieve at least 32% of the SSL. Due to the low production of beef meat locally, the industry is forced to rely highly on imported beef, contributing to the high trade deficit. The inconsistency of local beef production is mainly affected by the cost of production.

Consumers in Malaysia prefer to eat less mutton. The consumption per capita of mutton is stable at 1.2 kg per person per year between 2015 and 2020. The mutton production dropped from nearly 5,000 tons in 2016 to almost 4,000 tons in 2020 but did not affect the demand much.

On the other hand, poultry is the most established segment under the livestock industry and the cheapest source of protein in Malaysia. The poultry meat production also decreased from 1.75 million tons in 2016 to 1.70 million tons in 2020. Despite drop in production, the supply is more than sufficient for local consumers. Table 6 shows that only poultry meat surpasses consumption (the supply is more than the demand). The consumption per capita for poultry has decreased from 56.5 kg in 2015 to 53.6 kg in 2020. As a result, the SSL for chicken was also reduced from 113.6% in 2015 to 105.4% in 2020. The excess supply of chicken enables Malaysia to export its products, primarily to Singapore. Malaysia exports more than 40,000 tons of poultry and poultry-based products to global marketplaces every year.

The NAP has targeted pork meat production to reduce by 0.8% annually; however, the production increased from 195,200 tons in 2016 to more than 220,000 tons in 2020. In addition, pork production is relatively consistent, almost equivalent to consumption. The production in 2020, however, is still below the target of 230,500 tons, or 94% of the SSL. The short supply will be imported from other countries.

Overall, milk production can only satisfy around 7.00% of total local demand, indicating high reliance on imported milk. Production of milk is stable at approximately 38 - 42 million liter every year. Thus, milk production has not been able to meet its NAP targets in 2020.

Objective 2: To develop the agro-food industry into a competitive and sustainable industry

Malaysia is a trading nation. Malaysia is the 27th most competitive nation globally out of 140 countries ranked in the 2018 edition of the Global Competitiveness Report published by the World Economic Forum. The Malaysian economy is driven by the import and export of finished products for local consumption or processing and repackaging for exports. The import and export of agro-food products are determined by the competitiveness of the local industry. Malaysia will export its agro-food products if the price is more competitive than the other countries that produce the same agro-food. At the same time, the local consumers will buy local products if the price is lower than the imported products. The export of the agro-food products is presented in Table 7.

Table 7 shows that the export of agricultural and processed products is increasing every year, indicating that Malaysia’s industry is sustainable and remains competitive in the global market. The export for the agro-food sector increased from RM18.1 (US$4.31) billion in 2010 to more than RM36.4 (US$8.67) billion in 2020, with the cumulative average growth rate (CAGR) about 7.26% in 10 years. Beverages and spices products contributed the most significant export value, while meat preparation, processed milk, and cereal preparation grew substantially in ten years. These figures indicate that global markets well accept Malaysia’s agro-food products.

Despite relying upon most agro-food commodities from other countries, Malaysia has a competitive advantage in its processing capability. Malaysia imports raw materials from neighboring countries, processes them and re-exports them to other countries. For example, Malaysia imported more than 100 million liters of milk from New Zealand, processed it, and re-export to other countries. The trading activities generate more than RM1.6 (US$0.38) billion in revenue to Malaysia.

Objective 3: To increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs

The third objective of the National Agro-food Policy (2011-2020) is to increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs. This policy aims to sustain the number of people working in this sector. This policy is essential because other sectors offer better financial opportunities and conducive working environment. Statistics show that the workforce in the agro-food sector has reduced from 535,700 people in 2010 to 484,520 people in 2020. The involvement of the workforce in agro-food compared to the country's total workforce also decreased from 4.50% to 3.21%.

Currently, no official data were published to indicate the income level of the agricultural entrepreneurs in Malaysia. The last national census on the demographic profile of the agriculture sector was carried out in 2016. In general, the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs increases marginally. Most of the industry received subsidies from the government, such as production subsidy for paddy and vegetable, price subsidy (floor price) for vegetables and fruit, petrol and diesel subsidy for the fisheries industry. The agricultural entrepreneurs also receive many incentives from the government that can be considered additional income for them.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

In general, the agriculture sector in Malaysia was affected by global and regional economic trends. For example, the supply of agricultural products in the world has increased significantly between 2000 and 2020. According to the statistic by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2021, the agriculture value-added has increased around 67% between 2000 and 2018 to around US$3.4 trillion, while the share of agriculture in global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) went up around 4% in 2020, compared to 2000. The total production of primary crops increased by 50% between 2000 and 2018, to 9.1 billion tons. According to the report, about one-third of the produce is contributed by cereals, followed by sugar (24%) and vegetables (12%). Vegetable oil production increased 108% between 2000 and 2017, while meat production increased more than 47% to around 342 million tons.

The monetary value of global food exports has increased to around US$1.4 trillion in 2018, compared to about US$380 billion in 2000. Fruits and vegetables accounted for 23% of the total food export value in 2018, followed by cereals and preparations (14%), fish, and meat (11%). The global food prices have moderated in the past five years, given the adoption of more policies in favor of food security. The higher supply of agro-food products affected agro-food production in Malaysia because the cost of production is relatively higher, and it is cheaper to buy the products from global marketplaces.

From the local perspective, the depreciation of the Malaysian Ringgit has contributed to a higher cost of production. For example, the value of the Malaysian Ringgit has depreciated to RM4.50 for US$1.0 in 2017 compared to RM2.90 in 2012. The prices of fertilizers, animal feeds, and agricultural machinery have increased and affected Malaysia's production cost.

Nonetheless, several key issues impede the sustainable growth of the agro-food industry. These issues are categorized into several themes, namely:

WAY FORWARD

The 12th Malaysian Development Plan replaced the 11th Malaysian Development Plan. The Malaysian government has identified new directions and strategies that can spearhead the development of the agriculture sector in Malaysia. The 12th development plan is the first part of Malaysia's ten-year plan, 2021-2030. This long-term plan aspires to balance the development of the economy with income distribution and people's well-being.

Under the 12th Malaysian Development Plan, the agriculture sector is projected to grow around 3.8% every year and contribute about 7.0% to the Good Domestic Product (GDP). The application of technology will enhance the development growth of this sector. The emphasis is to speed up the transformation of this sector to be a modern, dynamic and competitive sector supported by research, development, commercialization, and innovation (R&D&C&I).

In addition, strategies and initiatives under the National Food Securities Framework and National Agro-food Policy 2021-2030 will be implemented to achieve the sufficiency of food supply and comply with international food safety standards. The use of biomass and biogas will also be optimized. Development of agri-commodity entrepreneurs for specialized products will be encouraged to diversify its products with a high added value.

REFERENCE

Department of Prime Minister (2021). 12th Malaysia Development Plan: prosperous, Sustainable and Inclusive. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department. Kuala Lumpur.

Department of Prime Minster (2015). Eleventh Malaysia Plan 2016-2020: Anchoring growth on people. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department. Kuala Lumpur.

Fisheries Department Malaysia (2021). Statistic of landed fish in Malaysia 2021. Strategic Planning Unit, Fisheries Department Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur.

Jabatan Pertanian Malaysia (2021). Booklet Statistik tanaman 2021. Sub-sektor tanaman makanan. (Department of Agriculture Malaysia (2021). booklet sub-sector food crops)

Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Makanan (2020). Dasar Agromakanan Negara 2.0: Permodenan agromakanan: Menjamin masa depan sekuriti makanan negra (Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (2020). National Agrofood Policy 2.0: Modernization of agrofood: Ensuring the future food security).

Veterinary Services Department (2021). Statistics of Livestock Malaysia (2021). Strategic Planning Unit, Veterinary Services Department, Kuala Lumpur.