ABSTRACT

Malaysia was hit by the COVID-19 since early February 2020. As of 20 July 2021, nearly one million people have been infected, with more than 10,000 deaths. At the same time, more than 950,000 have recovered from the disease. During the pandemic, the agriculture sector remained open as to ensure that food supply is not interrupted. However, the movement control order or MCO has restricted the movement of the workers and the logistics of the food supply. The MCO has reduced the supply of agri-food products in the market place, and in the long run, will affect the food security of the nation, if farmers are leaving the industry. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (MAFI) has taken several strategies to ensure that food security is sustainable during and after the pandemic crisis. Some mitigation programs or initiatives have been implemented such as the establishment of the COVID-19 mitigation subgroups that monitor the supply of food products, the establishment of the National Cabinet Committee on Food Security Policy and the Executive Committee on the National Food Security. The roles of these committees are to ensure that food security in this country is always sustainable and secured.

Keywords: Food security, COVID-19, pandemic, crisis

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia is a part of the 2019 corona virus pandemic that is hitting the world. The pandemic started in early February 2020, and the government has announced the Movement Control Order (MCO) on March 18, 2020 as a measure to deal with the health crisis. As of July 20, 2021, the cumulative cases in Malaysia were 951,884 with total number of deaths exceeding 6,700 people. At the same time, more than 806,857 patients have fully recovered from the disease since it started about one-and-a-half years ago. Malaysia is currently in phase one of the National Recovery Plan (NRP) from June 29, 2021 until the required indicators are met to move to phase two. The National Recovery Plan is a four-phase exit strategy from the COVID-19 crisis. The strategy of the National Recovery Plan is based on three indicators:

- COVID-19 transmissions among the community, based on the number of daily COVID-19 infections;

- Capability of the public healthcare system, based on the bed utilization rate in the intensive care unit (ICU) wards; and

- How much of the population is protected against the COVID-19, based on the percentage of people who has received two doses of vaccines.

The first phase of the plan entails the implementation of the full movement control order (FMCO) in light of the high COVID-19 cases, the critical state of the healthcare system and the low vaccination rate. The government will then consider shifting into phase two of the plan if the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 4,000, the healthcare system is no longer at a critical stage, with the ICU bed usage, return to moderate levels and 10% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. During this phase, economic activities will be reopening in phases, starting with the essential services such as food sectors, health care services and transportation industry, and followed by other industries such as contraction and manufacturing, with up to 80% of workers are allowed onsite. Only certain sectors will be allowed to operate, including the agriculture sector. The government will add more sectors to the current list, such as cement manufacturing to support construction activities, sales of computers and electronic devices to cater to those who work from home. At the same time, no social activities and interstate travels are allowed.

In phase three, all economic activities except for those with high risks of COVID-19 transmissions and involving large gatherings will be allowed to resume. The government will consider shifting to phase three if the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 2,000, the healthcare system is operating at a comfortable level, with the ICU bed usage reduced sufficiently and 40% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. In this phase, all economic sectors will continue operating at 80% capacity. Manufacturing activities will be allowed, subject to the SOPs and the capacity limits. However, companies may be allowed to operate fully if workers have been vaccinated. The government will consider moving on to phase four, or the final phase, when the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 500, the healthcare system is at a safe level, with the ICU bed usage at a sufficient level and 60% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. The government is expecting that 80% of the population will receive their double vaccines in October 2021, and all economic activities, including the agriculture sector will go back to normal.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the sectors were ordered to shut down their operations. Only some sectors economy including the agriculture sector and related industries along the supply chain of good has been listed as necessary or essential services. The efforts to make sure food supply are guaranteed is one of the factors that need to be given special attention when a nation is struggling with the pandemic. A study by the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) reveals that around 91.1% of entrepreneurs in the agri-food sector were affected by the pandemic. Many agri-food crops are left unharvested on the farm due to lack of manpower and the drop of demand from consumers. The ASEAN Secretariat reported that the COVID-19 crisis has shrunk around 5% of the economy of the ASEAN countries in 2020. Report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry Malaysia (MAFI) on the other hand, indicates that the agriculture GDP has dropped around 7% during this crisis.

This paper highlights some issues related to the supply side of the agricultural products during the COVID-19 pandemic and some suggestions in overcoming the shortage of agriculture products during and after the crisis.

CHALLENGES IN MANAGING FOOD SECURITY IN MALAYSIA

In Malaysia, there are two types of agriculture - plantation and food production. On the plantation side, Malaysia is doing very well. The value of palm oil exports is about RM90 (US$21.43) billion a year. But on the food production side, Malaysia in general, is way behind its neighboring countries. For example, Malaysia only produced 71% of the rice, fruit (66%), vegetables (40%) and ruminants (29%). There are many reasons food security has become a problem in Malaysia. The main one is that food crops are a lot harder to plant and maintain compared with oil palm. The lifespan of an oil palm tree is 25 years while that of most food crops is a few months to a few years. Growing food requires a lot of manpower as the turnover rate is high. Farmers need to use a lot of fertilizers and pesticides. As most of these products are imported, they are getting increasingly expensive due to the weak value of the Malaysian Ringgit.

Currently, there are 5.8 million hectares of land in Malaysia being cultivated to palm oil, compared with just one million hectares allotted to food crops. A typical plantation company would have thousands of acres of land to cultivate oil palm. Food crop farmers, on the other hand, only have about five acres each to work on. The income from food crop cultivation is not big enough to attract more people to engage in agriculture. Only 28% of the country’s population is involved in agriculture, and they are, on average, 60 years old. Youngsters have started to realize that plantations are a lot easier to maintain than food crops, and palm oil prices are relatively stable. So, many farmers quit planting food crops and start planting oil palm. Some of them even sold their agricultural lands to be converted into housing and industrial areas.

The other challenges in cultivating food crops are about managing pests and diseases. Farmers have to deal with blast disease (rice), leaf rust disease (corn) and fusarium disease (tomato), among others. Most of agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and chemicals are imported and the price of these inputs has increased, and consequently, increased the cost of production. In general, the competitiveness of the agricultural produce in Malaysia has diminished as compared to other neighboring countries such as Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam. These are some of the issues that could reduce the food production and make it difficult for Malaysia to meet the demand of the population.

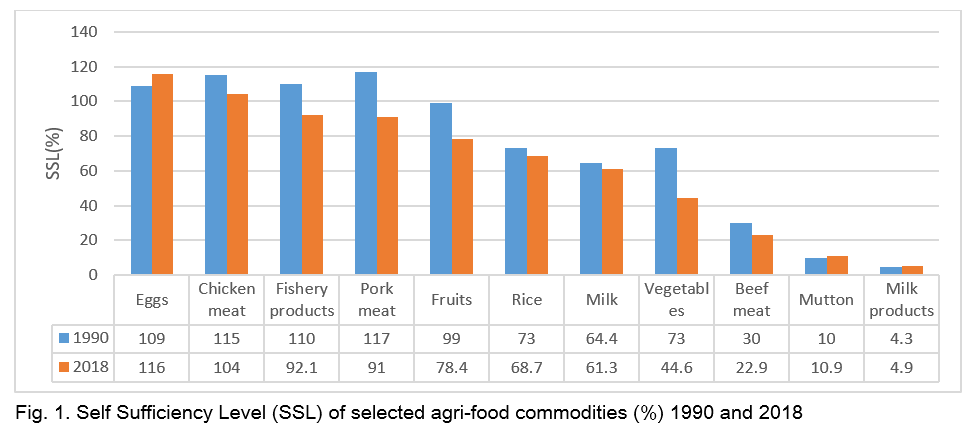

The growing population is also one of the factors that is challenging the supply of agriculture products. In 2003, the population of Malaysia was only 23 million. Currently, the population has grown to more than 32 million, and is projected to reach 37 million by 2030. The government is doing its best to maintain the percentage of production, but it is harder. This is reflected by the percentage of self-sufficiency level (SSL) of food crops (Figure 1). The limitation in producing more food crops as discussed above is a new challenge that the government has to face in the future.

Figure 1 shows that the self-sufficiency level of most of the agri-food commodities has dropped significantly, except chicken and duck eggs. Despite increased in production, the higher demand from local consumers has reduced the SSL of all agri-food commodities in Malaysia. For example, despite the fact that production of rice has increased from 1.215 million MT in 1990 to more than 2.000 million MT in 2018, the SSL has dropped from 73% to 68.7%. The increase in population is parallel with the demand and consumption of rice. As a result, Malaysia needs to import more rice from Thailand, Vietnam, India and Pakistan for its population.

IMPACT OF THE COVID-19 CRISIS ON FOOD SUPPLY

The COVID-19 crisis has affected Malaysia’s economy. The country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has contracted 17% in the second quarter of 2020, more than one million people lost their jobs and nearly 70,000 small and medium industries or SMEs went bankrupt. The choice between saving lives and economic health is a complicated consideration. The economic impact of the pandemic on the low-income group has also been severe, especially in terms of food security. Studies show that more than half of Malaysia's population cannot afford to provide RM1,000 (US$238.10) when the crisis occurs. During the pandemic, almost 60% of households experienced a reduction in income of up to RM700 (US$166.70) a month. Economic instability affects the food security status of the population, especially in terms of the financial ability to buy, and more importantly, in providing nutritious food for children.

To date, the main way in which the COVID-19 has threatened food security and undermined households’ nutrition is via overall stagnation in the economy, income shortfalls and job losses, particularly for migrant workers and poor households. These threats have undermined households’ abilities to buy food and other essentials. It is estimated that more than one million immigrants are affected because of the closure of the many businesses and factory operations. The agriculture sector activities such as the cultivation of vegetables and short term fruits like pineapples have also been reported to be stagnant for many months.

Social problems are also prevalent such as depression, child abuse, domestic malpractice and many other issues. A study by UNICEF and the health ministry found that one in five children in Kuala Lumpur and one in four senior citizens in Putrajaya suffered from physical growth retardation, respectively. In fact, it also affects the eating habits of people as seen in an increase in the intake of instant noodles (40%), eggs (50%) and rice (40%) among the poor during this period of the epidemic. Nutritious foods such as fresh meat and vegetables are expensive foods for the B40 income group, where this group represents the bottom 40% of income earners. The main factors that cause these symptoms are due to reduced income, inadequate local food supply and prices of food items that are unaffordable. These symptoms can be minimized if local food production is adequate and cheap.

Issues related to the supply of food products

The MCO has affected the supply of food commodity in the market places. There are many issues and challenges faced by the agri-food entrepreneurs in supplying the agri-food products during the pandemic crisis as follows:

- The agricultural produce are reported to remain on the farms and are left unharvested due to lack of manpower or labor, and lack of transportation to bring the produce to the market place. As a result, the price of the agricultural produce has dropped significantly;

- Intra-state travel restrictions and checkpoints continue to pose barriers to the distribution of food, despite sufficient supply in most states. Even in sites near food-producing facilities, the delivery and transport of fresh fruits, vegetables, and animal products may take up to several weeks as personnel are required to adhere to standards of operation procedure (SOP); and

- The price of fresh agri-food products are reported to be unstable, especially the locally produce food commodity, except the control products such as rice, fresh chicken, and meat (beef, mutton). A report by the MAFI in 2020 shows that the price of 32% of fresh food has increased, while around 30% of them has dropped (Table 1). The price increase is between 0.4% and 113%, while the price dropped is between 0.4% and 20.27%. In other words, the price increase is greater than the price dropped.

-

In the long term, the pandemic crisis will affect the pattern of food supply from foreign markets. Malaysia’s dependency on imported products is expected to increase in the future when the local producers are leaving the industry. For many years, Malaysia is a net importer of agricultural food and food products. Malaysia imported more than RM51 (US$12.14) billion of food and food products in 2018. In certain food market segments, Malaysia is almost totally dependent on the importation, especially in the meat sector, along with dairy, seafood and cocoa. Malaysia imports approximately 80% of its beef from other countries, reaching an import value of US$937.81 million. The domestic supply of beef meat is fulfilled by importation, mainly from India (77%), Australia (14%) and New Zealand (5%). Almost all dairy product ingredients are imported, including nonfat and whole milk powder, whey, and other dairy solids. These imported products are then used to produce sweetened condensed milk, yogurt, and reconstituted fluid milk. Malaysia’s imports of milk and cream have also significantly increased year-to-year, reaching US$63.7 million in 2019. The major suppliers of dairy products are New Zealand (37%), U.S. (13%) and Australia (15%).

Research on the pattern of food imports in the country reveals several things of concern, namely:

- The trade deficit continued to increase from RM1.0 (US$0.24) billion (1990) to RM18.0 (US$4.28) billion (2018). This reflects the failure to stimulate substantial growth in local food production;

- High dependence on imports for food supply - The largest import value reaching RM8.0 (US$1.90) billion is animal feed and cereals. The largest deficit was from animal feed worth RM3.9 (US$0.93) billion, while meat and meat-based products were worth RM3.2 (US$0.76) billion;

- Food and beverage products account for more than half of total exports, thus showing the bright export potential of these products; and

- Apart from food, Malaysia also imports almost all agricultural inputs such as seeds and animal breeds, fertilizers and pesticides, machineries, animal feeds and labor. As a result, the cost of food production skyrocketed.

-

Plan of action

Instability and falling prices are common in commodity markets, especially those involving foods. The last food crisis was during the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 and showed that the price of the agricultural products, especially rice and cereal has increased. Generally, after the crisis subsided, prices returned to normal. However, the fall in commodity prices during the COVID-19 pandemic was vastly different. First, it is a global symptom. Second, it affects supply and demand. Third, it demands new norms in life as well as business procedures. Fourth, the duration of the pandemic is difficult to predict due to the uncertainty of the vaccine efficacy. Therefore, finding a solution in such a matrix framework is not an easy task. Strategies to fight infection through the method of movement restriction or lockdown are very effective, but it has a great impact on the economy. Furthermore, Malaysia is facing the third wave of the COVID-19, which is more aggressive and harmful.

The MAFI has set about an operation room for the COVID-19 crisis for monitoring the status of daily food supply and issues faced by farmers so that mitigation action can be taken immediately. Monitoring of the conditions in the field is implemented by departments and agencies through a Situation Report (SITREP) as many as two times a day. The report by the SITREP showed that almost 80% of the problems faced by farmers during the crisis are connected to distribution and marketing issues as a result of movement control, as well as lack of demand for raw materials due to the closure of farmers markets, processing plants, factories, hotels and restaurants.

The MAFI has established a COVID-19 Mitigation Subgroup to ensure the food security remains intact. Five clusters were established, that include the Marketing Cluster, the Support Agriculture Cluster, the Sustainable Production Cluster, the Agricultural Modernization Cluster and the Trade Cluster. The role of these clusters is to ensure that food supply remains secure throughout the pandemic, and it is implemented under the Mitigation Plan for Agri-Food Sector. Among them is by leveraging e-commerce platforms (e-commerce) such as Agrobazaar Online and NEKMATBIZ, establish cooperation with private companies as well as implementing the financial assistance schemes as incentives based on output, and fund for working capital. The ministry also used other strategies that include providing incentives to ensure farmers will continue to produce agricultural products through the Buy Back Scheme. The government also enhanced the speed of the Internet in rural areas for on-line marketing, introduced innovation in the value chain and markets as well as enhanced cooperation and diplomacy between countries within the ASEAN. In addition, Malaysia will try to get the support from member countries of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

In addition, the government has also allocated RM590 (US$140.47) million under the People's Concerned Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN) and the Economic Regeneration Plan (GENERATOR) 2020 for the implementation programs that can help and increase the capacity of farmers, breeders, fishermen and entrepreneurs in food industries. Among them is fund from the Farmers Organization (PPK), Fishermen Association (PNK), Mobilization Enhancement Program and Foodstuff Logistics, Financing Scheme, Micro Credit, Kebuniti/Urban Agriculture Program and Workforce Mobility Programs. The MAFI realizes the need to create an integrated mechanism involving agencies and ministries to improve the reliability and efficiency of the national food system. The government supports these mitigation mechanisms, and this is indicated when the Cabinet of Ministers has agreed to the establishment of the National Cabinet Committee on Food Security Policy (JKKDSMN) with the chairmanship by the Prime Minister. JKKDSMN has the role of formulating policies on national food security holistically and sustainable. This committee will be assisted by the Executive Committee on the National Food Security Policy which serves as a committee coordinator and chaired by the Minister of the MAFI. The members of the Executive Committee are the secretary-general of the ministries and directors-general of departments, the Governor of the National Bank, industry activists, and agricultural experts such as the academics as well as the non-governmental organization (NGO) related to the agri-food sector. The role of JKKDSMN is to enhance the national food security by ensuring the food is always available all the time, people have the access to food sources, the foods are always safe and nutritious and the supply is always sustainable.

WAY FORWARD

Crisis comes and goes. Malaysia has experienced many crises such as the recession in 1985, the financial crisis of 1997-1998, and the financial crisis of 2007–2008, which is also known as the global financial crisis (GFC). The GFC was a severe worldwide economic crisis. These crises have affected Malaysia’s economy. The price of local goods has increased, and it changed the consumption pattern of the people. People wanted to buy cheaper products, and as a result, the government allows more products from overseas to enter this market. In general, the import of the food products is increased during the crisis in Malaysia because most of the products are imported from overseas markets.

The approach that needs to be taken by Malaysia to reduce its dependency on imported products are as follows:

- Establish the "Food first" policy because Malaysia has a wealth of natural resources that should be utilized as much as possible for food production. These resources include land, biodiversity, sunlight, infrastructure and so on. Emphasis should be given to nutritious, safe and quality crops and food for the people;

- Mobilize modern and sustainable technologies such as precision farming and ICT applications such as drones, sensors, artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) to increase productivity and marketing needs to be mobilized systematically and integrated. A research and development (R&D) agenda as well as its extension also needs to be formulated towards achieving this goal;

- Encourage new business or startups in the area of food and beverage, local organic fertilizer production, green and sustainable production technologies, small machine for small-scale business. The government is also suggested to build smart factories for small farmers and small and medium industries (SMIs);

- In order to cultivate interest in youth into agricultural entrepreneurship, Malaysian government has been providing a variety of activities and programs to improve their skills (Pemandu, 2013). Training such as cultivating premium vegetable in controlled environment, product processing, marketing, advertising, branding are offered and organized largely by agricultural departments;

- Strengthen the communication system that includes the use of the Internet of thing (IoT), increase the speed of the internet in rural areas and provide training on the application of smart agriculture to all farmers and agrofood entrepreneurs;

- Improve big data and provide data analytic to aid farmer to make decision on the production and the marketing of their agri-food products;

- Transform wholesale/retail market to be a clean, organized, and modern market design; and

- Consolidate an advanced integrated agricultural cooperative model to engage in value-added activities.

-

In order to ensure the success of the above proposal, support from institutions as well as other physical assistance is also needed. It is a beginning that promises a more prosperous future for the people.

REFERENCES

________(2020). Kesan COVID-19 dan Jaminan makanan Negara - Isu, Cadangan dan Solusi. Agrobank Malaysia.

Amalia, F., Wang, K., & Gunawan, A. (2020). COVID-19: Can Halal Food Lessen the Risks of the Next Similar Outbreak?. International Journal of Applied Business Research, 2(02), 86-95https://doi.org/10.35313/ijabr.v2i02.112

Ahmad Ashraf Shaharudin. 2020. Protecting the Agriculture Sector During the COVID-19 Crisis. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute

Businesswire (2020). Pre & Post COVID-19 Market Estimates-Halal Food Market 2019-2023 | Demand of Halal Food to Boost Growth | Technavio https://www.businesswire.com/news/ home/20200424005425/en/

Bank Negara Malaysia (2018). Pasaran dan Pemerkasaan Pengguna ttps://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/fsps/bm/2018/cp04.pdf Amalan Pasaran dan Pemerkasaan Pengguna 2018

Christopher Choong Weng Wai (2020). PostMCO: A Labour Reallocation Strategy. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Fatimah Mohamed Arshad (2016). Food Policy in Malaysia. Reference Module in Food Sciences. Elsevier, pp. 1–12

FAO (2008), An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security http://www.fao.org/3/a-al936e.pdf

High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and nutrition (HLPE). (2020). Interim issues paper on the impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition (FSN). Rome, Italy: Committee on World Food Security

Jabatan Pertanian (2018), Statistik Tanaman (SubSektor Tanaman Makanan) 2018, Jabatan Pertanian, Putrajaya: Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas-tani

Kementerian Pertanian dan Agro-makanan (2019). Statistik Agro Makakanan 2018Malaysia. (1984). The National Agricultural Policy I 1984.

Ma, N.L., Peng, W., Soon, C.F., Noor Hassim, M.F., Misbah, S., Rahmat, Z., Lym Yong, W.T., Sonne, C., (2020) COVID-19 Pandemic in the lens of food safety and security, Environmental Research https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110405

Majlis Keselamatan Negara (MKN). (2020). SOP Pembukaan Semula Sektor Ekonomi https://www.mkn.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SOPPembukaan-Semula-Ekonomi.pdf

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. (1992). The National Agricultural Policy II, 1992–2010.

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. (1999). The Third Agricultural Policy, 1998–2010.

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia (2011). Malaysian National Agro-Food Policy (2011-2020). Ministry of Agriculture & Agro-Based Industry, Putrajaya

Norfatin Nadiah Rosli (2020). Pelan Strategik Kerajaan Terhadap Jaminan Bekalan Makanan

Negara Sepanjang Tempoh PKP, Perspektif 20/2020. Didapatkan dari Terengganu Strategic & Integrity Institute (TSIS)

Managing Food Security during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic

ABSTRACT

Malaysia was hit by the COVID-19 since early February 2020. As of 20 July 2021, nearly one million people have been infected, with more than 10,000 deaths. At the same time, more than 950,000 have recovered from the disease. During the pandemic, the agriculture sector remained open as to ensure that food supply is not interrupted. However, the movement control order or MCO has restricted the movement of the workers and the logistics of the food supply. The MCO has reduced the supply of agri-food products in the market place, and in the long run, will affect the food security of the nation, if farmers are leaving the industry. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry (MAFI) has taken several strategies to ensure that food security is sustainable during and after the pandemic crisis. Some mitigation programs or initiatives have been implemented such as the establishment of the COVID-19 mitigation subgroups that monitor the supply of food products, the establishment of the National Cabinet Committee on Food Security Policy and the Executive Committee on the National Food Security. The roles of these committees are to ensure that food security in this country is always sustainable and secured.

Keywords: Food security, COVID-19, pandemic, crisis

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia is a part of the 2019 corona virus pandemic that is hitting the world. The pandemic started in early February 2020, and the government has announced the Movement Control Order (MCO) on March 18, 2020 as a measure to deal with the health crisis. As of July 20, 2021, the cumulative cases in Malaysia were 951,884 with total number of deaths exceeding 6,700 people. At the same time, more than 806,857 patients have fully recovered from the disease since it started about one-and-a-half years ago. Malaysia is currently in phase one of the National Recovery Plan (NRP) from June 29, 2021 until the required indicators are met to move to phase two. The National Recovery Plan is a four-phase exit strategy from the COVID-19 crisis. The strategy of the National Recovery Plan is based on three indicators:

The first phase of the plan entails the implementation of the full movement control order (FMCO) in light of the high COVID-19 cases, the critical state of the healthcare system and the low vaccination rate. The government will then consider shifting into phase two of the plan if the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 4,000, the healthcare system is no longer at a critical stage, with the ICU bed usage, return to moderate levels and 10% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. During this phase, economic activities will be reopening in phases, starting with the essential services such as food sectors, health care services and transportation industry, and followed by other industries such as contraction and manufacturing, with up to 80% of workers are allowed onsite. Only certain sectors will be allowed to operate, including the agriculture sector. The government will add more sectors to the current list, such as cement manufacturing to support construction activities, sales of computers and electronic devices to cater to those who work from home. At the same time, no social activities and interstate travels are allowed.

In phase three, all economic activities except for those with high risks of COVID-19 transmissions and involving large gatherings will be allowed to resume. The government will consider shifting to phase three if the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 2,000, the healthcare system is operating at a comfortable level, with the ICU bed usage reduced sufficiently and 40% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. In this phase, all economic sectors will continue operating at 80% capacity. Manufacturing activities will be allowed, subject to the SOPs and the capacity limits. However, companies may be allowed to operate fully if workers have been vaccinated. The government will consider moving on to phase four, or the final phase, when the average daily COVID-19 cases fall below 500, the healthcare system is at a safe level, with the ICU bed usage at a sufficient level and 60% of the population has received two doses of COVID-19 vaccines. The government is expecting that 80% of the population will receive their double vaccines in October 2021, and all economic activities, including the agriculture sector will go back to normal.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the sectors were ordered to shut down their operations. Only some sectors economy including the agriculture sector and related industries along the supply chain of good has been listed as necessary or essential services. The efforts to make sure food supply are guaranteed is one of the factors that need to be given special attention when a nation is struggling with the pandemic. A study by the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) reveals that around 91.1% of entrepreneurs in the agri-food sector were affected by the pandemic. Many agri-food crops are left unharvested on the farm due to lack of manpower and the drop of demand from consumers. The ASEAN Secretariat reported that the COVID-19 crisis has shrunk around 5% of the economy of the ASEAN countries in 2020. Report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry Malaysia (MAFI) on the other hand, indicates that the agriculture GDP has dropped around 7% during this crisis.

This paper highlights some issues related to the supply side of the agricultural products during the COVID-19 pandemic and some suggestions in overcoming the shortage of agriculture products during and after the crisis.

CHALLENGES IN MANAGING FOOD SECURITY IN MALAYSIA

In Malaysia, there are two types of agriculture - plantation and food production. On the plantation side, Malaysia is doing very well. The value of palm oil exports is about RM90 (US$21.43) billion a year. But on the food production side, Malaysia in general, is way behind its neighboring countries. For example, Malaysia only produced 71% of the rice, fruit (66%), vegetables (40%) and ruminants (29%). There are many reasons food security has become a problem in Malaysia. The main one is that food crops are a lot harder to plant and maintain compared with oil palm. The lifespan of an oil palm tree is 25 years while that of most food crops is a few months to a few years. Growing food requires a lot of manpower as the turnover rate is high. Farmers need to use a lot of fertilizers and pesticides. As most of these products are imported, they are getting increasingly expensive due to the weak value of the Malaysian Ringgit.

Currently, there are 5.8 million hectares of land in Malaysia being cultivated to palm oil, compared with just one million hectares allotted to food crops. A typical plantation company would have thousands of acres of land to cultivate oil palm. Food crop farmers, on the other hand, only have about five acres each to work on. The income from food crop cultivation is not big enough to attract more people to engage in agriculture. Only 28% of the country’s population is involved in agriculture, and they are, on average, 60 years old. Youngsters have started to realize that plantations are a lot easier to maintain than food crops, and palm oil prices are relatively stable. So, many farmers quit planting food crops and start planting oil palm. Some of them even sold their agricultural lands to be converted into housing and industrial areas.

The other challenges in cultivating food crops are about managing pests and diseases. Farmers have to deal with blast disease (rice), leaf rust disease (corn) and fusarium disease (tomato), among others. Most of agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and chemicals are imported and the price of these inputs has increased, and consequently, increased the cost of production. In general, the competitiveness of the agricultural produce in Malaysia has diminished as compared to other neighboring countries such as Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam. These are some of the issues that could reduce the food production and make it difficult for Malaysia to meet the demand of the population.

The growing population is also one of the factors that is challenging the supply of agriculture products. In 2003, the population of Malaysia was only 23 million. Currently, the population has grown to more than 32 million, and is projected to reach 37 million by 2030. The government is doing its best to maintain the percentage of production, but it is harder. This is reflected by the percentage of self-sufficiency level (SSL) of food crops (Figure 1). The limitation in producing more food crops as discussed above is a new challenge that the government has to face in the future.

Figure 1 shows that the self-sufficiency level of most of the agri-food commodities has dropped significantly, except chicken and duck eggs. Despite increased in production, the higher demand from local consumers has reduced the SSL of all agri-food commodities in Malaysia. For example, despite the fact that production of rice has increased from 1.215 million MT in 1990 to more than 2.000 million MT in 2018, the SSL has dropped from 73% to 68.7%. The increase in population is parallel with the demand and consumption of rice. As a result, Malaysia needs to import more rice from Thailand, Vietnam, India and Pakistan for its population.

IMPACT OF THE COVID-19 CRISIS ON FOOD SUPPLY

The COVID-19 crisis has affected Malaysia’s economy. The country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has contracted 17% in the second quarter of 2020, more than one million people lost their jobs and nearly 70,000 small and medium industries or SMEs went bankrupt. The choice between saving lives and economic health is a complicated consideration. The economic impact of the pandemic on the low-income group has also been severe, especially in terms of food security. Studies show that more than half of Malaysia's population cannot afford to provide RM1,000 (US$238.10) when the crisis occurs. During the pandemic, almost 60% of households experienced a reduction in income of up to RM700 (US$166.70) a month. Economic instability affects the food security status of the population, especially in terms of the financial ability to buy, and more importantly, in providing nutritious food for children.

To date, the main way in which the COVID-19 has threatened food security and undermined households’ nutrition is via overall stagnation in the economy, income shortfalls and job losses, particularly for migrant workers and poor households. These threats have undermined households’ abilities to buy food and other essentials. It is estimated that more than one million immigrants are affected because of the closure of the many businesses and factory operations. The agriculture sector activities such as the cultivation of vegetables and short term fruits like pineapples have also been reported to be stagnant for many months.

Social problems are also prevalent such as depression, child abuse, domestic malpractice and many other issues. A study by UNICEF and the health ministry found that one in five children in Kuala Lumpur and one in four senior citizens in Putrajaya suffered from physical growth retardation, respectively. In fact, it also affects the eating habits of people as seen in an increase in the intake of instant noodles (40%), eggs (50%) and rice (40%) among the poor during this period of the epidemic. Nutritious foods such as fresh meat and vegetables are expensive foods for the B40 income group, where this group represents the bottom 40% of income earners. The main factors that cause these symptoms are due to reduced income, inadequate local food supply and prices of food items that are unaffordable. These symptoms can be minimized if local food production is adequate and cheap.

Issues related to the supply of food products

The MCO has affected the supply of food commodity in the market places. There are many issues and challenges faced by the agri-food entrepreneurs in supplying the agri-food products during the pandemic crisis as follows:

In the long term, the pandemic crisis will affect the pattern of food supply from foreign markets. Malaysia’s dependency on imported products is expected to increase in the future when the local producers are leaving the industry. For many years, Malaysia is a net importer of agricultural food and food products. Malaysia imported more than RM51 (US$12.14) billion of food and food products in 2018. In certain food market segments, Malaysia is almost totally dependent on the importation, especially in the meat sector, along with dairy, seafood and cocoa. Malaysia imports approximately 80% of its beef from other countries, reaching an import value of US$937.81 million. The domestic supply of beef meat is fulfilled by importation, mainly from India (77%), Australia (14%) and New Zealand (5%). Almost all dairy product ingredients are imported, including nonfat and whole milk powder, whey, and other dairy solids. These imported products are then used to produce sweetened condensed milk, yogurt, and reconstituted fluid milk. Malaysia’s imports of milk and cream have also significantly increased year-to-year, reaching US$63.7 million in 2019. The major suppliers of dairy products are New Zealand (37%), U.S. (13%) and Australia (15%).

Research on the pattern of food imports in the country reveals several things of concern, namely:

Plan of action

Instability and falling prices are common in commodity markets, especially those involving foods. The last food crisis was during the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 and showed that the price of the agricultural products, especially rice and cereal has increased. Generally, after the crisis subsided, prices returned to normal. However, the fall in commodity prices during the COVID-19 pandemic was vastly different. First, it is a global symptom. Second, it affects supply and demand. Third, it demands new norms in life as well as business procedures. Fourth, the duration of the pandemic is difficult to predict due to the uncertainty of the vaccine efficacy. Therefore, finding a solution in such a matrix framework is not an easy task. Strategies to fight infection through the method of movement restriction or lockdown are very effective, but it has a great impact on the economy. Furthermore, Malaysia is facing the third wave of the COVID-19, which is more aggressive and harmful.

The MAFI has set about an operation room for the COVID-19 crisis for monitoring the status of daily food supply and issues faced by farmers so that mitigation action can be taken immediately. Monitoring of the conditions in the field is implemented by departments and agencies through a Situation Report (SITREP) as many as two times a day. The report by the SITREP showed that almost 80% of the problems faced by farmers during the crisis are connected to distribution and marketing issues as a result of movement control, as well as lack of demand for raw materials due to the closure of farmers markets, processing plants, factories, hotels and restaurants.

The MAFI has established a COVID-19 Mitigation Subgroup to ensure the food security remains intact. Five clusters were established, that include the Marketing Cluster, the Support Agriculture Cluster, the Sustainable Production Cluster, the Agricultural Modernization Cluster and the Trade Cluster. The role of these clusters is to ensure that food supply remains secure throughout the pandemic, and it is implemented under the Mitigation Plan for Agri-Food Sector. Among them is by leveraging e-commerce platforms (e-commerce) such as Agrobazaar Online and NEKMATBIZ, establish cooperation with private companies as well as implementing the financial assistance schemes as incentives based on output, and fund for working capital. The ministry also used other strategies that include providing incentives to ensure farmers will continue to produce agricultural products through the Buy Back Scheme. The government also enhanced the speed of the Internet in rural areas for on-line marketing, introduced innovation in the value chain and markets as well as enhanced cooperation and diplomacy between countries within the ASEAN. In addition, Malaysia will try to get the support from member countries of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

In addition, the government has also allocated RM590 (US$140.47) million under the People's Concerned Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN) and the Economic Regeneration Plan (GENERATOR) 2020 for the implementation programs that can help and increase the capacity of farmers, breeders, fishermen and entrepreneurs in food industries. Among them is fund from the Farmers Organization (PPK), Fishermen Association (PNK), Mobilization Enhancement Program and Foodstuff Logistics, Financing Scheme, Micro Credit, Kebuniti/Urban Agriculture Program and Workforce Mobility Programs. The MAFI realizes the need to create an integrated mechanism involving agencies and ministries to improve the reliability and efficiency of the national food system. The government supports these mitigation mechanisms, and this is indicated when the Cabinet of Ministers has agreed to the establishment of the National Cabinet Committee on Food Security Policy (JKKDSMN) with the chairmanship by the Prime Minister. JKKDSMN has the role of formulating policies on national food security holistically and sustainable. This committee will be assisted by the Executive Committee on the National Food Security Policy which serves as a committee coordinator and chaired by the Minister of the MAFI. The members of the Executive Committee are the secretary-general of the ministries and directors-general of departments, the Governor of the National Bank, industry activists, and agricultural experts such as the academics as well as the non-governmental organization (NGO) related to the agri-food sector. The role of JKKDSMN is to enhance the national food security by ensuring the food is always available all the time, people have the access to food sources, the foods are always safe and nutritious and the supply is always sustainable.

WAY FORWARD

Crisis comes and goes. Malaysia has experienced many crises such as the recession in 1985, the financial crisis of 1997-1998, and the financial crisis of 2007–2008, which is also known as the global financial crisis (GFC). The GFC was a severe worldwide economic crisis. These crises have affected Malaysia’s economy. The price of local goods has increased, and it changed the consumption pattern of the people. People wanted to buy cheaper products, and as a result, the government allows more products from overseas to enter this market. In general, the import of the food products is increased during the crisis in Malaysia because most of the products are imported from overseas markets.

The approach that needs to be taken by Malaysia to reduce its dependency on imported products are as follows:

In order to ensure the success of the above proposal, support from institutions as well as other physical assistance is also needed. It is a beginning that promises a more prosperous future for the people.

REFERENCES

________(2020). Kesan COVID-19 dan Jaminan makanan Negara - Isu, Cadangan dan Solusi. Agrobank Malaysia.

Amalia, F., Wang, K., & Gunawan, A. (2020). COVID-19: Can Halal Food Lessen the Risks of the Next Similar Outbreak?. International Journal of Applied Business Research, 2(02), 86-95https://doi.org/10.35313/ijabr.v2i02.112

Ahmad Ashraf Shaharudin. 2020. Protecting the Agriculture Sector During the COVID-19 Crisis. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute

Businesswire (2020). Pre & Post COVID-19 Market Estimates-Halal Food Market 2019-2023 | Demand of Halal Food to Boost Growth | Technavio https://www.businesswire.com/news/ home/20200424005425/en/

Bank Negara Malaysia (2018). Pasaran dan Pemerkasaan Pengguna ttps://www.bnm.gov.my/files/publication/fsps/bm/2018/cp04.pdf Amalan Pasaran dan Pemerkasaan Pengguna 2018

Christopher Choong Weng Wai (2020). PostMCO: A Labour Reallocation Strategy. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Fatimah Mohamed Arshad (2016). Food Policy in Malaysia. Reference Module in Food Sciences. Elsevier, pp. 1–12

FAO (2008), An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security http://www.fao.org/3/a-al936e.pdf

High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and nutrition (HLPE). (2020). Interim issues paper on the impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition (FSN). Rome, Italy: Committee on World Food Security

Jabatan Pertanian (2018), Statistik Tanaman (SubSektor Tanaman Makanan) 2018, Jabatan Pertanian, Putrajaya: Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas-tani

Kementerian Pertanian dan Agro-makanan (2019). Statistik Agro Makakanan 2018Malaysia. (1984). The National Agricultural Policy I 1984.

Ma, N.L., Peng, W., Soon, C.F., Noor Hassim, M.F., Misbah, S., Rahmat, Z., Lym Yong, W.T., Sonne, C., (2020) COVID-19 Pandemic in the lens of food safety and security, Environmental Research https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110405

Majlis Keselamatan Negara (MKN). (2020). SOP Pembukaan Semula Sektor Ekonomi https://www.mkn.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SOPPembukaan-Semula-Ekonomi.pdf

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. (1992). The National Agricultural Policy II, 1992–2010.

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. (1999). The Third Agricultural Policy, 1998–2010.

Ministry of Agriculture, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia (2011). Malaysian National Agro-Food Policy (2011-2020). Ministry of Agriculture & Agro-Based Industry, Putrajaya

Norfatin Nadiah Rosli (2020). Pelan Strategik Kerajaan Terhadap Jaminan Bekalan Makanan

Negara Sepanjang Tempoh PKP, Perspektif 20/2020. Didapatkan dari Terengganu Strategic & Integrity Institute (TSIS)