ABSTRACT

Herbs have been identified as a new source of economic growth for Malaysia since 2011. This is in tandem with higher demand for herbal products in the world markets. Malaysia is rich in flora and fauna that contain medicinal ingredients and health benefits. However, the herbal industry is a small and fragmented industry in Malaysia. In general, there are no comprehensive programs and initiatives for this industry until 2011 when the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry started to recognize the importance of these commodities. Starting from that time, the government has created new directions and strategies that can transform this industry into a dynamic, competitive and profitable industry.

Keywords: Herbal industry, transformation, dynamic, competitive, profitable industry

INTRODUCTION

The herbal industry has been identified as a new source of economic growth contributor for Malaysia since 2011. Herbs have been classified as potential agricultural commodities under the National Key Economic Area (NKEA), and is expecting to contribute to country’s income and create employment opportunities. The Malaysian government has chosen the herbal industry as the first Entry Point Project (EPP1) for the nation’s Agriculture New Key Economic Area. The value of the herbal industry was around RM17 billion (US$4.1 billion) in 2013 and is projected to grow between 8% and 15% annually to reach around RM32 billion (US$ 7.6 billion) by 2020. The development of this industry is projected to contribute around RM2.2 billion (US$0.5 billion) gross national income (GNI) by 2020 and create around 1,800 new job opportunities for Malaysian people. Herbs have been considered as the crops of the future.

Higher demand from domestic as well as global markets offers new opportunities for Malaysia to transform its herbal industry from a fragmented to a structured and competitive industry. Malaysia needs to transform this industry and strategize the short and long term action plans to ensure all programs are carried out effectively and efficiently. This paper discusses current scenario of the herbal industry in Malaysia and highlights the Malaysian government’s initiatives in transforming this industry towards a sustainable one.

Global Herbal Industry

In general, herbs are plants with aromatic properties that are used for flavouring and garnishing food, as fragrance and medicine. Herbs are used mainly for food supplements, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, in the chemical industry, for personal care and as medicine. People are slowly recognizing that herbal products are effective, safe and non-toxic and have lesser side effects to humans. The global trend is toward ‘return to nature’. As a result, the global market value of the herbal industry has increased tremendously from US$60 billion in 2000, to US$200 billion (2008) and US$105 billion in 2017. The World Bank projected the global market to grow around 7.6% annually and will reach US$5 trillion by 2050 (Ghosh, 2013; World Bank, 2007).

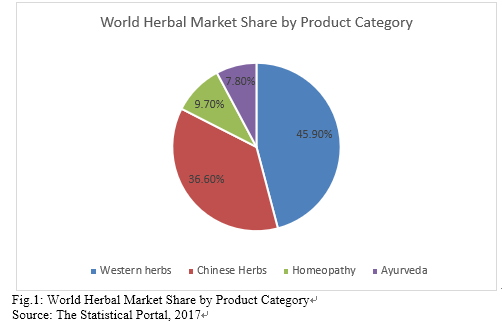

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of the world's population relies on traditional herbal medicine as a basic health care. The Statistical Portal revealed that in 2017, the highest global market share for herbal products is the Western Herbs of 45.9%, followed by the Chinese Herbs (36.6%), the Homeopathy (9.7%) and the Ayurveda (7.8%) (Figure 1).

Fig.1: World Herbal Market Share by Product Category

Source: The Statistical Portal, 2017

In Asia, herbal production is dominated by China through Chinese traditional medicine products worth around US$48 billion and export value of around US$3.6 billion in 2010 (Sangita Kumari et al, 2011). Asia Pacific (excluding Japan) is the largest contributor in the production and utilization of herbs (extracts and spices) with estimated market value of US$4 billion (2017). This value is expected to increase to US$7 billion in 2027 with the annual growth rate of 5.5% (Future Market Insight, 2017).

Malaysian Herbal Industry

Malaysia is one of the largest contributors to the world’s biodiversity. According to a report released by the Malaysian Biotechnology Corporation (2009), Malaysia ranked 12th in the world and the fourth in Asia as a diversified country. Malaysia is rich with tropical rainforests that contain more than 100 species of ferns, 185,000 fauna and medicinal crops. There are about 2,000 plant species in Malaysia that can be used as medicines and therapies by various levels of society and generations (Bidin and Latiff, 1995). Additionally, 1,200 and 2,000 herbaceous species are found in Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak (Soepadmo, 1992). Most species of herbs in Malaysia are wild plants in the forests, and some of them have been cultivated in residential areas.

In Malaysia, herbs have been classified by product groups as follows:

- Flavours and fragrance

- Cosmetics

- Perfumes

- Oil for aroma

- Essential oils

- Beverages

- Pharmaceuticals/Herbal

- Remedies/Drugs

- Vitamins/ Supplements

- Health/Functional food

- Health food

- Herbal teas

- Herbal supplements

- Bio-pesticides

- Insect repellent

- Crops pesticide

- Household pesticide

Some species of herbs have been identified to be cultivated in large-scale for commercial purposes. For example, Mas Cotek (Ficus deltoid), Misai Kucing (Ortho siphon aristatus/ stamineus benth), Lidah Buaya (Aloe Vera Inn) and Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia) are potential herbal crops for medicinal use. These wild herbs were cultivated in new ecosystem and managed under the good agricultural practices. The domestication of wild herbs has increased the production of herbal products in Malaysia. As a result, the market value of the herbal industry has reached RM10 billion (US$2.44 billion) in 2008 (NAP, 2011) and this figure is expected to increase further to RM32 billion (US$ 7.8 billion) by 2020.

Production of herbs

Despite its being a small industry, the commercial herbal crops are cultivated in all areas in Malaysia. The cultivated herbaceous area in Malaysia has increased from 1,198 hectares in 2011 to 2,317 hectares in 2017, an increase about 14% annually (Department of Agriculture, 2017). The increase of land area has led to the increase in production of herbs from 8,911 tons (2011) to 11,674 tons (2017) with an average annual growth rate of 9% (Table 1). On the other hand, spices cultivation area also increased from 4,993 hectares in 2011 to 6,998 (2017) with an average annual growth rate of 6%. The spices production also increased by 11% for the same period with production values of 32,469 tons and 56,946 tons respectively (Table 2) (DOA, 2018).

Table 1: Herbal Area and Production in Malaysia

|

Item

|

2011

|

2013

|

2014

|

2016

|

2017

|

Annual Growth Rate (%)

|

|

Area (Hectare)

|

1,198

|

1,299

|

2,176

|

2,312

|

2,317

|

14

|

|

Production (Tons)

|

8,911

|

8,425

|

13,468

|

11,649

|

11,674

|

9

|

*Kaemprefis Galanga, Orthosiphon Stamineus, Aloe Vera, Indian Pennywort, Morinda Citrifolia, Tea Tree, Cymbophogon Nardus, Eurycoma Longifolia, Betel Vine

Source: Agrofood Statistic, Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2015-2017)

Table 2: Spices Area and Production in Malaysia

|

Item

|

2011

|

2013

|

2014

|

2016

|

2017

|

Annual Growth Rate (%)

|

|

Area (Hectare)

|

4,993

|

5,860

|

6,163

|

6,723

|

6,997

|

6

|

|

Production (Tons)

|

32,469

|

52,256

|

56,105

|

53,212

|

56,946

|

11

|

* Hot Chilli, Ginger, Turmeric, Greater Galangal, Musklime, Lime, Nutmeg, Lemon Grass

Source: Agrofood Statistic, Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2015-2017)

Herbal trade

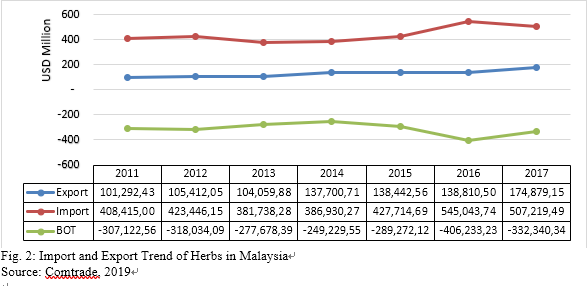

The last ten years have seen substantial growth in the global market for herbs and herbal products, and Malaysia also feels the impacts. Despite being rich in biodiversity, Malaysia is the net importer of herbal products. The average value of imports has increased around 4% between 2011 and 2017; as compared to the average export which increased about 10%. The highest import and export value were recorded in 2016 and 2017 at US $ 547 million and US $ 174.8 million, respectively (Figure 2).

Although the trade balance of the herbal industry shows deficit value every year, the report shows that the export of herbal products has increased tremendously from US$137.7 in 2014 to US$174.8 million in 2017. This record shows that the local herbal industry has grown significantly. However, high dependence on raw materials by the local herbal industry has led to increase in imports. Most raw herbal sources are imported from China, Indonesia and India (Comtrade, 2018). In the same period, the imports of raw materials have increased about 15%. It shows that the export of herbal products performed better and has contributed to the revenue of Malaysia.

Issues and challenges

In general, the issues and challenges that impede the development of the herbal industry in Malaysia can be divided into three main factors: 1) Failure in implementing the policy and strategy; 2) Insufficient supply of raw materials’ and 3) No official standard for quality management. The policy related to the herbal industry has been created in the National Agricultural Policy 1, 2, 3 and National Agrofood Policy. All national agricultural policy addressed the issues and challenges faced by this industry, creates strategies and action plans on how to enhance the industry. Malaysia has a comprehensive and beautiful policies related to the development of the herbal industry. The policies addressed the fragmentation of the industry clearly. However, Malaysia is still lacking in the implementation of the policies, strategies and action plan. The implementation of the strategies was carried out by many organizations. For example, R&D activities are carried out by the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute or MARDI, the Forest Research Institute or FRIM and universities. The production of commercial herbs is monitored by the Department of Agriculture (DOA) and the marketing of herbal products is carried out by SMEs which is monitored by many agencies. On the other hand, the registration of herbal products for consumption (such as food supplements or healthy food) or as medicinal product is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Health. These agencies sit under different Ministries and they have different directions. There is no specific lead agency that can ensure the success of the implementation of the policies for the development of the industry. The industry needs an integrated effort that is led by one Ministry.

Despite being rich with agro-biodiversity, Malaysia has limited sources of raw materials. This is evidenced by the higher quantity of imported raw herbs every year. Report shows that the value of imported herbs has increased from US$ 381.7 million in 2013 to US$ 507.2 million in 2017. These raw herbs are processed by SMEs to become herbal products. A study by MARDI in 2002 revealed that around 50% of the SMEs relied on imported raw herbs to meet their needs. High dependency on imported raw materials is also influenced by the price factor of raw herbs from cheaper exporting countries and inconsistent supply by local farmers. At the same time, extensive exploring forests for development has led to the destruction and extinction of the wild herb plants.

To avoid the extinction of herbal and spice crops, an initiative of selective replanting of herbs has been taken through a number of government projects and initiatives, especially the East Coast Economic Region (ECER), the Permanent Food Production Park (TKPM), the Iskandar Regional Development Authority (IRDA) and the Sabah Development Corridor (SDC). More commercially grown of herb cultivation area were developed aims to increase production and quality of herbs. Other agencies involved in this program are the South Kelantan Development Authority (KESEDAR) and the Central Terengganu Development Authority (KETENGAH).

The other issue that slows down the development of the herbal industry in Malaysia is lacking of standard that will lead to inconsistent quality of raw herbs. In general, the quality of fresh herbs is similar or better than the imported one. The herbs are collected directly from the jungle or harvested from the farms. The issue arises during the post-harvest handling that include the cleaning, drying, packaging and storing. The mismanagement of the process reduced the quality of the herbs and affects the final products. According to the WHO (2007) report, Malaysian herbs industry is still less encouraging in terms of quality and safety controls to the effectiveness of product utilization especially in traditional herbal medicine industries. Studies on the active ingredient content, synergistic effects, critical dose, side effects, contraindications with herbs and other medicines as well as animal and human testing should be further enhanced to increase the value of local herbal products (Ramlan, 2003).

The national herbal industry is still lagging in the global market if compared to other Asian countries, especially China and India. The majority of herbal firms in Malaysia are of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), most of them are not able to invest in R&D and value-added activities because of their limited financial and knowledge resources. Research and development in the herbal industry is essential to enhance the competitiveness of local herbal products in the global marketplace with the creation of new herbal products from local herbal sources thus ensuring continuous supply of raw herbs (Ahmad and Othman, 2013).

STRATEGIES, POLICIES & DIRECTION

Policies and strategic plans

Several policies and strategies have been created to support the national herbal industry. Almost every long-term country plan such as the Second Malaysia Development Plan until the 11th Malaysia Development Plan contains the basic elements and strategies for the local herbal industry. In addition, the First and Third Industry Master Plans, First and Second Agricultural Policy and the National Agro-Food Policy (NAP), Science and Technology Policy, National Biodiversity Policy, Traditional Medicine and Complimentary Policy, and National Key Economic Areas (NKEA) emphasizing the development of the herbal industry. Through the NAP and NKEA, a rationalization of development has been implemented by establishing the National Herbs Development Council (approved by the Malaysian Cabinet on 9 February 2011) which combines the major players of the industrial herb market including growers, manufacturers and marketers to coordinate the planning and development of the herbal industry. Additionally, through the NAP, emphasis is given to produce and develop high value herbal products. The increase in production and productivity is intensified further by establishing the Permanent Food Production Park of Herbal and Spices (TKPM) in the East Coast Economic Region (ECER) including KESEDAR and KETENGAH.

Recently, the government has identified 18 species of herbs and ten species of spices to be developed commercially in Malaysia. Among the ten herbs are aloe vera, tongkat ali (eurycoma longifolia), kacip tatimah (labisia pumila), misai kucing (orthosiphon stamineus), pegaga (centella asiatica), mengkudu (morinda citrifolia), hempedu bumi (andographis paniculata), serai wangi (cymbopogon nardus), roselle (hibiscus sabdariffa), dukung anak (phyllanthus niruri) and mas cotek (ficus deltoidea). While the spices are lemongrass (cymbopogom citrates), ginger (zingiber officinale), key lime (citrus aurantifolia), calamansi (citrus microcarpa), kaffir lime (citrus hystrix), galangal (alpinia galanga), torchginger flower (phaeomeria speciosa), kesum (polygonum minus huds) and tamarind (gracinia atroviridis).

Way forward

Malaysia has significant competitive advantages that the herbal industry can claim leverage, including its biodiversity, arable land for cultivation of high value herbal crops and the ecosystem that can boost-up the industry. The government has set a new direction to ensure the herbal industry is growing and has a bright future. Six programs will be implemented under a coordinated national projects. The objectives are to improve the quality of the products and strengthen the marketing efforts so that Malaysian herbal products can penetrate global export markets for nutraceutical products and botanical drugs. The new programs include:

Production of raw materials

Intensive cultivation needs to be done in a more structured manner and will be managed on a large scale that can meet the Good Agricultural Practice (myGAP). At the same time all farmers are encouraged to apply the Malaysian Organic Certification Scheme (myOrganic). The government provides some incentives for those who register their farm with the myGAP and myOrganic. These initiatives will ensure all herbal crops are certified with international standard and can compete in the international markets.

Guaranteed supply of raw herbs at the farm level

Supply of raw herbs to industrial consumers need to be consistent in ensuring sustainable business relationships. Efficient herbal storage facilities are also very important, especially from logistics, frozen storage and so on to ensure the freshness and quality of the raw herbs are guaranteed. The government will build extraction facilities with a capacity of 1,000 kilograms per week to supply the industry with reliable, premium quality extracts at competitive cost. The extraction centres will be located in strategic areas where farmers can send their herbs easily and cost effectively.

Guaranteed quality

Herbal products produced must adhere to the essential aspects of use such as quality, safety and effectiveness to ensure consumer confidence in local herbal products. The focus of the herbal industry is not just fresh herbs but also more herbs processed as medicinal, cosmetics, functional foods that have added value. The government will establish herbal centre of excellence where each centre will respectively lead R&D in discovery, crop production and agronomy, standardization and product development and pre-clinical studies. The centre of excellence will be responsible for coordinating R&D among research institutions, establishing collaboration between local and international institutions and obtaining and managing the IP of the research findings.

Product development

In ensuring the development of herbal products to meet consumer demand, government agencies and product or technology generators need to have a strong networking with the private sector. Herb products is manufactured based on the current market demand. In addition, legal aspects of product generation such as protecting copyright should also be implemented. The commercialization of technologies by public research institution will be intensified. The government provides many platforms and events that can match between entrepreneurs and inventors. For example, the Malaysian Commercial Year Program or MCY creates a platform for inventors to commercialize their technology directly to capable investors.

Manufacturing standards

Herbal product processing plants should be benchmarked and adhere to international standards by obtaining certified certificates such as Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and complying with the requirement of exporting countries such as obtaining phytosanitary certificates.

Marketing strategy

Marketing strategies need to be enhanced to include market links internationally to ensure that herbal products can penetrate the global marketplace efficiently. In addition, Malaysian herbal products will be branding as a quality and niche products. Malaysian products will be exported under the umbrella brand and the government will work with foreign regulators to facilitate the registration of Malaysian herbal products in their markets.

CONCLUSION

Herbs have become an established industry in the world. However, Malaysia is still in the process of developing its industry. It is a long process for the Malaysian herbal industry to be at par with the major players such as China and India. Nevertheless, continuous efforts by the government has resulted in a progressive and dynamic industry. The government initiatives accomplished industry players toward a sustainable and profitable venture. It is hoped that the industry will grow faster and contribute to the welfare of the farmers and the economy of the nation.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, F., Shah Zaidi, M.A., Sulaiman, N. dan Abdul Majid, F.A. (2015). Issues and Challenges in the Development of the Herbal Industry in Malaysia. PROSIDINGPERKEM 10, (2015) 227 – 238 ISSN: 2231-962X

Ahmad, S. dan Othman, N. (2013). Strategic Planning, Issues, Prospects and the Future of the Malaysian Herbal Industry. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences. Vol.3, No. 4, pp. 91-102.

Bidin, A. A., & Latiff, A. (1995). The status of terrestrial biodiversity in Malaysia. In : A.H. Zakri (Ed.). Prospects in biodiversity prospecting (pp. 59-73). Genetic Society of Malaysia & Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur

Comtrade. (2018). International Trade Statistics Database, http://comtrade.un.org/. Diaksespada April 2018.

Jabatan Pertanian Malaysia (2017). Booklet Statistik Tanaman 2017. Malaysia

Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani. (2015). Statitik Agro Makanan2015- 2017, Malaysia.

Ramlan, A.A. (2003). Turning Malaysia into A Global Herbal Producer A Personel Perspective. Siri Syarahan Perdana Profesor.

The Statistical Portal (2017). https://www.statista.com/ Diakses pada April 2018

World Health Organization (2007). Strategic Planning, Issues, Prospect and the future of Malaysian Hebal Industry. World Health Organization.

Zakaria, M.H., Abdullah, A.M., Kamarulzaman, N.H., dan Abd latif, I. (2012). Macro Outlook of Herbal Industry in Malaysia.

|

Date submitted: May. 1, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June. 13, 2019

|

Transformation of Herbal Industry in Malaysia

ABSTRACT

Herbs have been identified as a new source of economic growth for Malaysia since 2011. This is in tandem with higher demand for herbal products in the world markets. Malaysia is rich in flora and fauna that contain medicinal ingredients and health benefits. However, the herbal industry is a small and fragmented industry in Malaysia. In general, there are no comprehensive programs and initiatives for this industry until 2011 when the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry started to recognize the importance of these commodities. Starting from that time, the government has created new directions and strategies that can transform this industry into a dynamic, competitive and profitable industry.

Keywords: Herbal industry, transformation, dynamic, competitive, profitable industry

INTRODUCTION

The herbal industry has been identified as a new source of economic growth contributor for Malaysia since 2011. Herbs have been classified as potential agricultural commodities under the National Key Economic Area (NKEA), and is expecting to contribute to country’s income and create employment opportunities. The Malaysian government has chosen the herbal industry as the first Entry Point Project (EPP1) for the nation’s Agriculture New Key Economic Area. The value of the herbal industry was around RM17 billion (US$4.1 billion) in 2013 and is projected to grow between 8% and 15% annually to reach around RM32 billion (US$ 7.6 billion) by 2020. The development of this industry is projected to contribute around RM2.2 billion (US$0.5 billion) gross national income (GNI) by 2020 and create around 1,800 new job opportunities for Malaysian people. Herbs have been considered as the crops of the future.

Higher demand from domestic as well as global markets offers new opportunities for Malaysia to transform its herbal industry from a fragmented to a structured and competitive industry. Malaysia needs to transform this industry and strategize the short and long term action plans to ensure all programs are carried out effectively and efficiently. This paper discusses current scenario of the herbal industry in Malaysia and highlights the Malaysian government’s initiatives in transforming this industry towards a sustainable one.

Global Herbal Industry

In general, herbs are plants with aromatic properties that are used for flavouring and garnishing food, as fragrance and medicine. Herbs are used mainly for food supplements, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, in the chemical industry, for personal care and as medicine. People are slowly recognizing that herbal products are effective, safe and non-toxic and have lesser side effects to humans. The global trend is toward ‘return to nature’. As a result, the global market value of the herbal industry has increased tremendously from US$60 billion in 2000, to US$200 billion (2008) and US$105 billion in 2017. The World Bank projected the global market to grow around 7.6% annually and will reach US$5 trillion by 2050 (Ghosh, 2013; World Bank, 2007).

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of the world's population relies on traditional herbal medicine as a basic health care. The Statistical Portal revealed that in 2017, the highest global market share for herbal products is the Western Herbs of 45.9%, followed by the Chinese Herbs (36.6%), the Homeopathy (9.7%) and the Ayurveda (7.8%) (Figure 1).

Fig.1: World Herbal Market Share by Product Category

Source: The Statistical Portal, 2017

In Asia, herbal production is dominated by China through Chinese traditional medicine products worth around US$48 billion and export value of around US$3.6 billion in 2010 (Sangita Kumari et al, 2011). Asia Pacific (excluding Japan) is the largest contributor in the production and utilization of herbs (extracts and spices) with estimated market value of US$4 billion (2017). This value is expected to increase to US$7 billion in 2027 with the annual growth rate of 5.5% (Future Market Insight, 2017).

Malaysian Herbal Industry

Malaysia is one of the largest contributors to the world’s biodiversity. According to a report released by the Malaysian Biotechnology Corporation (2009), Malaysia ranked 12th in the world and the fourth in Asia as a diversified country. Malaysia is rich with tropical rainforests that contain more than 100 species of ferns, 185,000 fauna and medicinal crops. There are about 2,000 plant species in Malaysia that can be used as medicines and therapies by various levels of society and generations (Bidin and Latiff, 1995). Additionally, 1,200 and 2,000 herbaceous species are found in Peninsular Malaysia, Sabah and Sarawak (Soepadmo, 1992). Most species of herbs in Malaysia are wild plants in the forests, and some of them have been cultivated in residential areas.

In Malaysia, herbs have been classified by product groups as follows:

Some species of herbs have been identified to be cultivated in large-scale for commercial purposes. For example, Mas Cotek (Ficus deltoid), Misai Kucing (Ortho siphon aristatus/ stamineus benth), Lidah Buaya (Aloe Vera Inn) and Tongkat Ali (Eurycoma longifolia) are potential herbal crops for medicinal use. These wild herbs were cultivated in new ecosystem and managed under the good agricultural practices. The domestication of wild herbs has increased the production of herbal products in Malaysia. As a result, the market value of the herbal industry has reached RM10 billion (US$2.44 billion) in 2008 (NAP, 2011) and this figure is expected to increase further to RM32 billion (US$ 7.8 billion) by 2020.

Production of herbs

Despite its being a small industry, the commercial herbal crops are cultivated in all areas in Malaysia. The cultivated herbaceous area in Malaysia has increased from 1,198 hectares in 2011 to 2,317 hectares in 2017, an increase about 14% annually (Department of Agriculture, 2017). The increase of land area has led to the increase in production of herbs from 8,911 tons (2011) to 11,674 tons (2017) with an average annual growth rate of 9% (Table 1). On the other hand, spices cultivation area also increased from 4,993 hectares in 2011 to 6,998 (2017) with an average annual growth rate of 6%. The spices production also increased by 11% for the same period with production values of 32,469 tons and 56,946 tons respectively (Table 2) (DOA, 2018).

Table 1: Herbal Area and Production in Malaysia

Item

2011

2013

2014

2016

2017

Annual Growth Rate (%)

Area (Hectare)

1,198

1,299

2,176

2,312

2,317

14

Production (Tons)

8,911

8,425

13,468

11,649

11,674

9

*Kaemprefis Galanga, Orthosiphon Stamineus, Aloe Vera, Indian Pennywort, Morinda Citrifolia, Tea Tree, Cymbophogon Nardus, Eurycoma Longifolia, Betel Vine

Source: Agrofood Statistic, Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2015-2017)

Table 2: Spices Area and Production in Malaysia

Item

2011

2013

2014

2016

2017

Annual Growth Rate (%)

Area (Hectare)

4,993

5,860

6,163

6,723

6,997

6

Production (Tons)

32,469

52,256

56,105

53,212

56,946

11

* Hot Chilli, Ginger, Turmeric, Greater Galangal, Musklime, Lime, Nutmeg, Lemon Grass

Source: Agrofood Statistic, Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2015-2017)

Herbal trade

The last ten years have seen substantial growth in the global market for herbs and herbal products, and Malaysia also feels the impacts. Despite being rich in biodiversity, Malaysia is the net importer of herbal products. The average value of imports has increased around 4% between 2011 and 2017; as compared to the average export which increased about 10%. The highest import and export value were recorded in 2016 and 2017 at US $ 547 million and US $ 174.8 million, respectively (Figure 2).

Although the trade balance of the herbal industry shows deficit value every year, the report shows that the export of herbal products has increased tremendously from US$137.7 in 2014 to US$174.8 million in 2017. This record shows that the local herbal industry has grown significantly. However, high dependence on raw materials by the local herbal industry has led to increase in imports. Most raw herbal sources are imported from China, Indonesia and India (Comtrade, 2018). In the same period, the imports of raw materials have increased about 15%. It shows that the export of herbal products performed better and has contributed to the revenue of Malaysia.

Issues and challenges

In general, the issues and challenges that impede the development of the herbal industry in Malaysia can be divided into three main factors: 1) Failure in implementing the policy and strategy; 2) Insufficient supply of raw materials’ and 3) No official standard for quality management. The policy related to the herbal industry has been created in the National Agricultural Policy 1, 2, 3 and National Agrofood Policy. All national agricultural policy addressed the issues and challenges faced by this industry, creates strategies and action plans on how to enhance the industry. Malaysia has a comprehensive and beautiful policies related to the development of the herbal industry. The policies addressed the fragmentation of the industry clearly. However, Malaysia is still lacking in the implementation of the policies, strategies and action plan. The implementation of the strategies was carried out by many organizations. For example, R&D activities are carried out by the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute or MARDI, the Forest Research Institute or FRIM and universities. The production of commercial herbs is monitored by the Department of Agriculture (DOA) and the marketing of herbal products is carried out by SMEs which is monitored by many agencies. On the other hand, the registration of herbal products for consumption (such as food supplements or healthy food) or as medicinal product is under the jurisdiction of the Department of Health. These agencies sit under different Ministries and they have different directions. There is no specific lead agency that can ensure the success of the implementation of the policies for the development of the industry. The industry needs an integrated effort that is led by one Ministry.

Despite being rich with agro-biodiversity, Malaysia has limited sources of raw materials. This is evidenced by the higher quantity of imported raw herbs every year. Report shows that the value of imported herbs has increased from US$ 381.7 million in 2013 to US$ 507.2 million in 2017. These raw herbs are processed by SMEs to become herbal products. A study by MARDI in 2002 revealed that around 50% of the SMEs relied on imported raw herbs to meet their needs. High dependency on imported raw materials is also influenced by the price factor of raw herbs from cheaper exporting countries and inconsistent supply by local farmers. At the same time, extensive exploring forests for development has led to the destruction and extinction of the wild herb plants.

To avoid the extinction of herbal and spice crops, an initiative of selective replanting of herbs has been taken through a number of government projects and initiatives, especially the East Coast Economic Region (ECER), the Permanent Food Production Park (TKPM), the Iskandar Regional Development Authority (IRDA) and the Sabah Development Corridor (SDC). More commercially grown of herb cultivation area were developed aims to increase production and quality of herbs. Other agencies involved in this program are the South Kelantan Development Authority (KESEDAR) and the Central Terengganu Development Authority (KETENGAH).

The other issue that slows down the development of the herbal industry in Malaysia is lacking of standard that will lead to inconsistent quality of raw herbs. In general, the quality of fresh herbs is similar or better than the imported one. The herbs are collected directly from the jungle or harvested from the farms. The issue arises during the post-harvest handling that include the cleaning, drying, packaging and storing. The mismanagement of the process reduced the quality of the herbs and affects the final products. According to the WHO (2007) report, Malaysian herbs industry is still less encouraging in terms of quality and safety controls to the effectiveness of product utilization especially in traditional herbal medicine industries. Studies on the active ingredient content, synergistic effects, critical dose, side effects, contraindications with herbs and other medicines as well as animal and human testing should be further enhanced to increase the value of local herbal products (Ramlan, 2003).

The national herbal industry is still lagging in the global market if compared to other Asian countries, especially China and India. The majority of herbal firms in Malaysia are of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), most of them are not able to invest in R&D and value-added activities because of their limited financial and knowledge resources. Research and development in the herbal industry is essential to enhance the competitiveness of local herbal products in the global marketplace with the creation of new herbal products from local herbal sources thus ensuring continuous supply of raw herbs (Ahmad and Othman, 2013).

STRATEGIES, POLICIES & DIRECTION

Policies and strategic plans

Several policies and strategies have been created to support the national herbal industry. Almost every long-term country plan such as the Second Malaysia Development Plan until the 11th Malaysia Development Plan contains the basic elements and strategies for the local herbal industry. In addition, the First and Third Industry Master Plans, First and Second Agricultural Policy and the National Agro-Food Policy (NAP), Science and Technology Policy, National Biodiversity Policy, Traditional Medicine and Complimentary Policy, and National Key Economic Areas (NKEA) emphasizing the development of the herbal industry. Through the NAP and NKEA, a rationalization of development has been implemented by establishing the National Herbs Development Council (approved by the Malaysian Cabinet on 9 February 2011) which combines the major players of the industrial herb market including growers, manufacturers and marketers to coordinate the planning and development of the herbal industry. Additionally, through the NAP, emphasis is given to produce and develop high value herbal products. The increase in production and productivity is intensified further by establishing the Permanent Food Production Park of Herbal and Spices (TKPM) in the East Coast Economic Region (ECER) including KESEDAR and KETENGAH.

Recently, the government has identified 18 species of herbs and ten species of spices to be developed commercially in Malaysia. Among the ten herbs are aloe vera, tongkat ali (eurycoma longifolia), kacip tatimah (labisia pumila), misai kucing (orthosiphon stamineus), pegaga (centella asiatica), mengkudu (morinda citrifolia), hempedu bumi (andographis paniculata), serai wangi (cymbopogon nardus), roselle (hibiscus sabdariffa), dukung anak (phyllanthus niruri) and mas cotek (ficus deltoidea). While the spices are lemongrass (cymbopogom citrates), ginger (zingiber officinale), key lime (citrus aurantifolia), calamansi (citrus microcarpa), kaffir lime (citrus hystrix), galangal (alpinia galanga), torchginger flower (phaeomeria speciosa), kesum (polygonum minus huds) and tamarind (gracinia atroviridis).

Way forward

Malaysia has significant competitive advantages that the herbal industry can claim leverage, including its biodiversity, arable land for cultivation of high value herbal crops and the ecosystem that can boost-up the industry. The government has set a new direction to ensure the herbal industry is growing and has a bright future. Six programs will be implemented under a coordinated national projects. The objectives are to improve the quality of the products and strengthen the marketing efforts so that Malaysian herbal products can penetrate global export markets for nutraceutical products and botanical drugs. The new programs include:

Production of raw materials

Intensive cultivation needs to be done in a more structured manner and will be managed on a large scale that can meet the Good Agricultural Practice (myGAP). At the same time all farmers are encouraged to apply the Malaysian Organic Certification Scheme (myOrganic). The government provides some incentives for those who register their farm with the myGAP and myOrganic. These initiatives will ensure all herbal crops are certified with international standard and can compete in the international markets.

Guaranteed supply of raw herbs at the farm level

Supply of raw herbs to industrial consumers need to be consistent in ensuring sustainable business relationships. Efficient herbal storage facilities are also very important, especially from logistics, frozen storage and so on to ensure the freshness and quality of the raw herbs are guaranteed. The government will build extraction facilities with a capacity of 1,000 kilograms per week to supply the industry with reliable, premium quality extracts at competitive cost. The extraction centres will be located in strategic areas where farmers can send their herbs easily and cost effectively.

Guaranteed quality

Herbal products produced must adhere to the essential aspects of use such as quality, safety and effectiveness to ensure consumer confidence in local herbal products. The focus of the herbal industry is not just fresh herbs but also more herbs processed as medicinal, cosmetics, functional foods that have added value. The government will establish herbal centre of excellence where each centre will respectively lead R&D in discovery, crop production and agronomy, standardization and product development and pre-clinical studies. The centre of excellence will be responsible for coordinating R&D among research institutions, establishing collaboration between local and international institutions and obtaining and managing the IP of the research findings.

Product development

In ensuring the development of herbal products to meet consumer demand, government agencies and product or technology generators need to have a strong networking with the private sector. Herb products is manufactured based on the current market demand. In addition, legal aspects of product generation such as protecting copyright should also be implemented. The commercialization of technologies by public research institution will be intensified. The government provides many platforms and events that can match between entrepreneurs and inventors. For example, the Malaysian Commercial Year Program or MCY creates a platform for inventors to commercialize their technology directly to capable investors.

Manufacturing standards

Herbal product processing plants should be benchmarked and adhere to international standards by obtaining certified certificates such as Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and complying with the requirement of exporting countries such as obtaining phytosanitary certificates.

Marketing strategy

Marketing strategies need to be enhanced to include market links internationally to ensure that herbal products can penetrate the global marketplace efficiently. In addition, Malaysian herbal products will be branding as a quality and niche products. Malaysian products will be exported under the umbrella brand and the government will work with foreign regulators to facilitate the registration of Malaysian herbal products in their markets.

CONCLUSION

Herbs have become an established industry in the world. However, Malaysia is still in the process of developing its industry. It is a long process for the Malaysian herbal industry to be at par with the major players such as China and India. Nevertheless, continuous efforts by the government has resulted in a progressive and dynamic industry. The government initiatives accomplished industry players toward a sustainable and profitable venture. It is hoped that the industry will grow faster and contribute to the welfare of the farmers and the economy of the nation.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, F., Shah Zaidi, M.A., Sulaiman, N. dan Abdul Majid, F.A. (2015). Issues and Challenges in the Development of the Herbal Industry in Malaysia. PROSIDINGPERKEM 10, (2015) 227 – 238 ISSN: 2231-962X

Ahmad, S. dan Othman, N. (2013). Strategic Planning, Issues, Prospects and the Future of the Malaysian Herbal Industry. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences. Vol.3, No. 4, pp. 91-102.

Bidin, A. A., & Latiff, A. (1995). The status of terrestrial biodiversity in Malaysia. In : A.H. Zakri (Ed.). Prospects in biodiversity prospecting (pp. 59-73). Genetic Society of Malaysia & Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur

Comtrade. (2018). International Trade Statistics Database, http://comtrade.un.org/. Diaksespada April 2018.

Jabatan Pertanian Malaysia (2017). Booklet Statistik Tanaman 2017. Malaysia

Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani. (2015). Statitik Agro Makanan2015- 2017, Malaysia.

Ramlan, A.A. (2003). Turning Malaysia into A Global Herbal Producer A Personel Perspective. Siri Syarahan Perdana Profesor.

The Statistical Portal (2017). https://www.statista.com/ Diakses pada April 2018

World Health Organization (2007). Strategic Planning, Issues, Prospect and the future of Malaysian Hebal Industry. World Health Organization.

Zakaria, M.H., Abdullah, A.M., Kamarulzaman, N.H., dan Abd latif, I. (2012). Macro Outlook of Herbal Industry in Malaysia.

Date submitted: May. 1, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June. 13, 2019