INTRODUCTION

Organic foods continue to grow in popularity worldwide. This rapid growth has been accompanied with an increase in the production of organic foods. Taiwan is no exception to that trend. As of 2016, the total amount of farmlands under organic production in the island state stood at 7,200 hectares (COA, 2016). This accounts for 0.7% of the total farmlands in Taiwan. The government of Taiwan actively tries to encourage organic production through legislation and practical support to farmers such as subsidies.

Organic food production in Taiwan

Modern day organic farming often requires a strict and extensive process of regulation and certification (Hsieh, 2005).However, small farmers in developing countries in the absence of capital to purchase expensive fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides have been practicing forms of uncertified organic farming for a long time (Paull, 2013). As of 2017, according to Taiwan’s agriculture census, 45,438 hectares of farmland in Taiwan which are used for agricultural production are operating without making use of fertilizers or pesticides (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017). This figure is much lower than the official figure of 7,200 hectares for organic farming. However, Taiwan saw massive investments and growth in agriculture during the post-war period after 1945 and lasted until the late 1980s. This period saw a rapid increase in food production since the government at that time was keen on achieving the rapid industrialization of the country (Mao & Schive, 1995). One of the unfortunate side effects of this rapid growth in industry was the increased use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Researchers have frequently uncovered the presence of high levels of pesticide residues in the environment of Taiwan (Doong & Lee, 1999; Doong et al., 2002).

Taiwan started exploring the idea of certified organic food production as early as 1986. This interest led to the introduction of experimental organic farms in the late 1980s. By 1997, the Council of Agriculture (COA) established guidelines for organic farming, and in January 2007, the “Agricultural Production and Certification Act” was implemented, setting out the regulatory framework for organic agriculture production (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017). From the beginning, the Executive Yuan of Taiwan sought to promote organic agriculture by launching ambitious targets designed to significantly increase the amount of land under organic production.

The latest legislative measure undertaken by the Taiwanese Executive Yuan is the “Organic Agriculture Promotion Act.” This act aims to more than double the amount of farmlands under organic production to 15,000 hectares by 2020 (“Taiwan Organic Agriculture,” 2017). The government also makes available subsidies to organic farmers. For example as of 2016, the government committed to providing subsidies ranging between NT$5,000 and NT$10,000 to organic farmers to assist in the purchase of raw materials and farm equipment. COA also offers financial support to organic farmers who wish to secure land purchases and buy organic fertilizers.

The organic food market in Taiwan

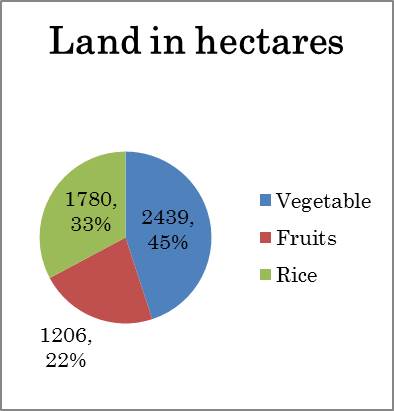

As seen in Fig 1, the majority of the organic foods grown in Taiwan based on the amount of land dedicated to cultivation are vegetables (45%, 2,439 hectares). This is followed by rice (33%, 1,780 hectares) and then fruits (22%, 1,206 hectares). The domestic production of organic food in Taiwan amounts to a total $123 million as of 2016. In addition, the value of imported organic foods which are mostly from the US stands at $40 million. Organic foods are normally sold in organic chain stores. The most popular organic chain store in Taiwan is Leezen, which has a total of 129 stores. (Refer to Table 1).

Fig. 1. Organic foods grown in Taiwan (Council of Agriculture, 2016)

Table 1. The complete list of the organic stores responsible for selling organic food products

|

Organic retail chain

|

Number of stores

|

|

Leezen

|

129

|

|

Uni-President Santa Cruz

|

96

|

|

Yogi House

|

70

|

|

Cotton Land Health Stores

|

61

|

|

Orange Market

|

19

|

|

Organic Garden

|

11

|

|

Organic Yam

|

10

|

|

Anyong Fresh

|

9

|

|

Green & Safe

|

5

|

Regulatory framework for organic certification in Taiwan

The certification process worldwide is usually defined by very strict rules and regulations. However, in the case of Taiwan, the lack of coordination with external organic certification bodies often leads to complications. The main regulatory bodies for overseeing the organic industry in Taiwan include the “Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Certification Management Regulations” and the “Imported Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Management Regulations.” Furthermore, three agencies within the COA bear responsibility for implementing this regulation: the “Department of Animal Industry for organic livestock and livestock processed products,” the “Fisheries Agency for organic aquatic and aquatic processed products, and the “Agriculture and Food Agency (AFA) for organic crops and crops processed products” (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005).

The Taiwan Accreditation Foundation (TAF) has been selected by the COA as the body with unique responsibility for evaluating organizations that apply as organic certifying boards. Taiwan hosts a total of 14 certifying agencies accredited to issue the Certified Agricultural Standards (CAS) organic stamp on domestic organic products; this stamp of approval is obligatory for all organic foods grown in Taiwan. CAS’ certification must be renewed every three years. CAS has the power to strip farmers of their organic certification when they have violations (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005).

Domestically, the COA has accredited 13 institutions to inspect and verify organic products, and in 2010, a total of 1,778 producers were audited and met the relevant standards, with certification covering a total of 4,034 hectares. To ensure the quality of organic products, 1,853 tests were made based on product quality, both in the field and at points of sale, with 1,841 (99.4%) found to be up to standard. In addition, 3,192 product label reviews were conducted, with 3,082 (96.6%) passing. Products that violated regulations were immediately removed from shelves and recalled, and local governments investigated responsibility under the law. These measures ensure that the interests of consumers of organic products are protected (COA, 2010). In addition, for imported organic foods, they are also protected by the law of trading organic products which in itself is regulated by the Agriculture Organic Imported Act, 2011 (COA, 2011).

However, the Taiwanese government does not recognize organic certification bodies from abroad (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005). This means that food certified as organic by certification bodies in Europe or the US would have to be tested again by certified bodies in Taiwan in order to earn the right to be classified as organic on store shelves in Taiwan. As a result, non-Taiwanese organic producers find it difficult and overly complicated to sell their organic foods in Taiwan. Furthermore, in 2017, Taiwan was working on a draft organic law that makes it compulsory for outside countries to recognize Taiwan’s certifying bodies’ authority in order to have their own organic products accepted in Taiwan.

CONCLUSION

The government of Taiwan seems dedicated to promoting organic agriculture in Taiwan. Relatively high incomes for consumers in Taiwan and the rapid expansion of farmlands under organic production augur well for the future of the industry in Taiwan. However, the complicated regulations required for producers wishing to export organic products to Taiwan may mean that the consumption or demand for imported organic foods remain restricted.

REFERENCES

Council of Agriculture, & Executive Yuan. (2017, July 27). Executive Yuan Passed the Draft to Organic Agriculture Promotion Act, a legislation aiming to promote the Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture. Retrieved June 08, 2018, from https://eng.coa.gov.tw/theme_data.php?theme=eng_news&id=501

Council of Agriculture (2011, June 23). Imported Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Management Regulations. Executive Yuan: Taiwan. Retrieved from http://law.coa.gov.tw/GLRSnewsout/EngLawContent.aspx?Type=E&id=117

Council of Agriculture (2010). The Quality Agriculture Development Program and Diversification of Value in Agriculture. Executive Yuan: Taiwan. Retrieved from https://eng.coa.gov.tw/ws.php?id=2444984

Doong, R. A., Lee, C. Y., & Sun, Y. C. (1999). Dietary intake and residues of organochlorine pesticides in foods from Hsinchu, Taiwan. Journal of AOAC International, 82(3), 677-682.

Doong, R. A., Sun, Y. C., Liao, P. L., Peng, C. K., & Wu, S. C. (2002). Distribution and fate of organochlorine pesticide residues in sediments from the selected rivers in Taiwan. Chemosphere, 48(2), 237-246.

Hsieh, S. C. (2005). Organic farming for sustainable agriculture in Asia with special reference to Taiwan experience. Research Institute of Tropical Agriculture and International Cooperation, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Pingtung, Taiwan.

Lee, H.J. (2013, November 27th). Organic Farming Certification of Taiwan. FFTC Agriculture Policy Platform. Retrieved from http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=141

Mao, Y. K., & Schive, C. (1995). Agricultural and industrial development in Taiwan. Agriculture on the Road to Industrialization, 23-66.

Paull, J. (2013). A history of the organic agriculture movement in Australia. In Organics in the global food chain (pp. 37-61). Connor Court Publishing.

Wu, P., & Anderson-Sprecher, A. (2017). Growing Demand for Organics in Taiwan Stifled by Unique Regulatory Barriers (Rep. No. TW17006). Taipei: USDA.

|

Date submitted: June 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: July 20, 2018

|

Organic Agriculture Development in Taiwan

INTRODUCTION

Organic foods continue to grow in popularity worldwide. This rapid growth has been accompanied with an increase in the production of organic foods. Taiwan is no exception to that trend. As of 2016, the total amount of farmlands under organic production in the island state stood at 7,200 hectares (COA, 2016). This accounts for 0.7% of the total farmlands in Taiwan. The government of Taiwan actively tries to encourage organic production through legislation and practical support to farmers such as subsidies.

Organic food production in Taiwan

Modern day organic farming often requires a strict and extensive process of regulation and certification (Hsieh, 2005).However, small farmers in developing countries in the absence of capital to purchase expensive fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides have been practicing forms of uncertified organic farming for a long time (Paull, 2013). As of 2017, according to Taiwan’s agriculture census, 45,438 hectares of farmland in Taiwan which are used for agricultural production are operating without making use of fertilizers or pesticides (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017). This figure is much lower than the official figure of 7,200 hectares for organic farming. However, Taiwan saw massive investments and growth in agriculture during the post-war period after 1945 and lasted until the late 1980s. This period saw a rapid increase in food production since the government at that time was keen on achieving the rapid industrialization of the country (Mao & Schive, 1995). One of the unfortunate side effects of this rapid growth in industry was the increased use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Researchers have frequently uncovered the presence of high levels of pesticide residues in the environment of Taiwan (Doong & Lee, 1999; Doong et al., 2002).

Taiwan started exploring the idea of certified organic food production as early as 1986. This interest led to the introduction of experimental organic farms in the late 1980s. By 1997, the Council of Agriculture (COA) established guidelines for organic farming, and in January 2007, the “Agricultural Production and Certification Act” was implemented, setting out the regulatory framework for organic agriculture production (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017). From the beginning, the Executive Yuan of Taiwan sought to promote organic agriculture by launching ambitious targets designed to significantly increase the amount of land under organic production.

The latest legislative measure undertaken by the Taiwanese Executive Yuan is the “Organic Agriculture Promotion Act.” This act aims to more than double the amount of farmlands under organic production to 15,000 hectares by 2020 (“Taiwan Organic Agriculture,” 2017). The government also makes available subsidies to organic farmers. For example as of 2016, the government committed to providing subsidies ranging between NT$5,000 and NT$10,000 to organic farmers to assist in the purchase of raw materials and farm equipment. COA also offers financial support to organic farmers who wish to secure land purchases and buy organic fertilizers.

The organic food market in Taiwan

As seen in Fig 1, the majority of the organic foods grown in Taiwan based on the amount of land dedicated to cultivation are vegetables (45%, 2,439 hectares). This is followed by rice (33%, 1,780 hectares) and then fruits (22%, 1,206 hectares). The domestic production of organic food in Taiwan amounts to a total $123 million as of 2016. In addition, the value of imported organic foods which are mostly from the US stands at $40 million. Organic foods are normally sold in organic chain stores. The most popular organic chain store in Taiwan is Leezen, which has a total of 129 stores. (Refer to Table 1).

Fig. 1. Organic foods grown in Taiwan (Council of Agriculture, 2016)

Table 1. The complete list of the organic stores responsible for selling organic food products

Organic retail chain

Number of stores

Leezen

129

Uni-President Santa Cruz

96

Yogi House

70

Cotton Land Health Stores

61

Orange Market

19

Organic Garden

11

Organic Yam

10

Anyong Fresh

9

Green & Safe

5

Regulatory framework for organic certification in Taiwan

The certification process worldwide is usually defined by very strict rules and regulations. However, in the case of Taiwan, the lack of coordination with external organic certification bodies often leads to complications. The main regulatory bodies for overseeing the organic industry in Taiwan include the “Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Certification Management Regulations” and the “Imported Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Management Regulations.” Furthermore, three agencies within the COA bear responsibility for implementing this regulation: the “Department of Animal Industry for organic livestock and livestock processed products,” the “Fisheries Agency for organic aquatic and aquatic processed products, and the “Agriculture and Food Agency (AFA) for organic crops and crops processed products” (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005).

The Taiwan Accreditation Foundation (TAF) has been selected by the COA as the body with unique responsibility for evaluating organizations that apply as organic certifying boards. Taiwan hosts a total of 14 certifying agencies accredited to issue the Certified Agricultural Standards (CAS) organic stamp on domestic organic products; this stamp of approval is obligatory for all organic foods grown in Taiwan. CAS’ certification must be renewed every three years. CAS has the power to strip farmers of their organic certification when they have violations (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005).

Domestically, the COA has accredited 13 institutions to inspect and verify organic products, and in 2010, a total of 1,778 producers were audited and met the relevant standards, with certification covering a total of 4,034 hectares. To ensure the quality of organic products, 1,853 tests were made based on product quality, both in the field and at points of sale, with 1,841 (99.4%) found to be up to standard. In addition, 3,192 product label reviews were conducted, with 3,082 (96.6%) passing. Products that violated regulations were immediately removed from shelves and recalled, and local governments investigated responsibility under the law. These measures ensure that the interests of consumers of organic products are protected (COA, 2010). In addition, for imported organic foods, they are also protected by the law of trading organic products which in itself is regulated by the Agriculture Organic Imported Act, 2011 (COA, 2011).

However, the Taiwanese government does not recognize organic certification bodies from abroad (Wu & Anderson-Sprecher, 2017; Hsieh, 2005). This means that food certified as organic by certification bodies in Europe or the US would have to be tested again by certified bodies in Taiwan in order to earn the right to be classified as organic on store shelves in Taiwan. As a result, non-Taiwanese organic producers find it difficult and overly complicated to sell their organic foods in Taiwan. Furthermore, in 2017, Taiwan was working on a draft organic law that makes it compulsory for outside countries to recognize Taiwan’s certifying bodies’ authority in order to have their own organic products accepted in Taiwan.

CONCLUSION

The government of Taiwan seems dedicated to promoting organic agriculture in Taiwan. Relatively high incomes for consumers in Taiwan and the rapid expansion of farmlands under organic production augur well for the future of the industry in Taiwan. However, the complicated regulations required for producers wishing to export organic products to Taiwan may mean that the consumption or demand for imported organic foods remain restricted.

REFERENCES

Council of Agriculture, & Executive Yuan. (2017, July 27). Executive Yuan Passed the Draft to Organic Agriculture Promotion Act, a legislation aiming to promote the Sustainable Development of Organic Agriculture. Retrieved June 08, 2018, from https://eng.coa.gov.tw/theme_data.php?theme=eng_news&id=501

Council of Agriculture (2011, June 23). Imported Organic Agricultural Product and Organic Agricultural Processed Product Management Regulations. Executive Yuan: Taiwan. Retrieved from http://law.coa.gov.tw/GLRSnewsout/EngLawContent.aspx?Type=E&id=117

Council of Agriculture (2010). The Quality Agriculture Development Program and Diversification of Value in Agriculture. Executive Yuan: Taiwan. Retrieved from https://eng.coa.gov.tw/ws.php?id=2444984

Doong, R. A., Lee, C. Y., & Sun, Y. C. (1999). Dietary intake and residues of organochlorine pesticides in foods from Hsinchu, Taiwan. Journal of AOAC International, 82(3), 677-682.

Doong, R. A., Sun, Y. C., Liao, P. L., Peng, C. K., & Wu, S. C. (2002). Distribution and fate of organochlorine pesticide residues in sediments from the selected rivers in Taiwan. Chemosphere, 48(2), 237-246.

Hsieh, S. C. (2005). Organic farming for sustainable agriculture in Asia with special reference to Taiwan experience. Research Institute of Tropical Agriculture and International Cooperation, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Pingtung, Taiwan.

Lee, H.J. (2013, November 27th). Organic Farming Certification of Taiwan. FFTC Agriculture Policy Platform. Retrieved from http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=141

Mao, Y. K., & Schive, C. (1995). Agricultural and industrial development in Taiwan. Agriculture on the Road to Industrialization, 23-66.

Paull, J. (2013). A history of the organic agriculture movement in Australia. In Organics in the global food chain (pp. 37-61). Connor Court Publishing.

Wu, P., & Anderson-Sprecher, A. (2017). Growing Demand for Organics in Taiwan Stifled by Unique Regulatory Barriers (Rep. No. TW17006). Taipei: USDA.

Date submitted: June 1, 2018

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: July 20, 2018