Introduction

When pork imports increase sharply, the Japanese government is geared to implement a special measure for protecting domestic pork producers. This urgent and temporary measure is called a “safeguard.” In the ongoing Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade negotiations, the Japanese government has promised to introduce a new type of safeguard that is applicable only for the TPP member countries. However, the TPP agreement is still subject to ratification in each country and remaining uncertainty about when, and indeed whether, the new agreement will become effective (note 1). Once the agreement becomes effective, however, Japan will have two types of safeguard. One is the current safeguard, which will be applied to countries outside the TPP (the authors call this the “regular safeguard” hereafter). The other is the new safeguard, which Japan has promised to apply only to the TPP member countries (the authors call this the “TPP safeguard” hereafter).

After studying the details of the TPP agreement, the authors have found that the TPP safeguard is something different from the regular safeguard and thus would not be effective for preventing sharp increases in pork imports. In spite of these important finding, it is not widely recognized in Japan at this stage. The authors consider that this low degree of recognition could have originated from the complicated structure of Japan’s pork import system and insufficient transparency in the behavior of Japanese customs regarding to pork imports. In this paper, the authors explain the details of the TPP safeguard and discuss its impacts on the pork market.

The current framework for pork imports

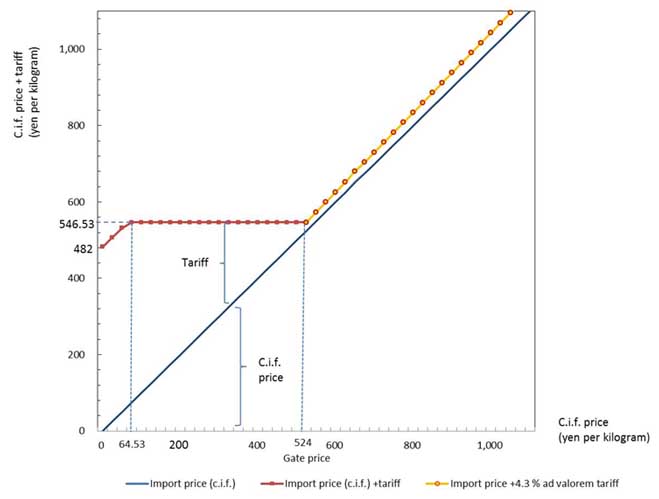

Japan has a unique system, called the “gate price system”, for pork imports. The system’s outline is shown in Fig. 1. There is a critical price, called the “gate price”, whereby the method of accessing the tariff differs. Historically, the gate price was revised in accordance with changes of the domestic pork market conditions acting as “Variable levy” (note 2). Since 2000, however the gate price has been fixed at 524 yen/kg (note 3). If the cost, insurance, and freight (c.i.f.) price is higher than the gate price, customs would apply a 4.3% ad valorem tariff. If the former is lower than the latter, the tariff assessment is lower level of the following: (1) 482 yen/kg, and (2) the difference between 546.53 yen (the gate price multiplied by 1.043) and the c.i.f. price.

Fig. 1. Japan's current pork import system (in the period when the regular safeguard is not implemented)

Combination imports and the tariff evasion problem

While domestically produced pork is ordinary traded in carcass form, foreign pork is mainly traded in boxed meat (cuts). The price differs in accordance to the cuts. As a result, pork importers have a problem in reporting pork price to the customs. For example, if a pork importer intends to import 10,000 kg of tenderloin at a c.i.f. price of 800 yen/kg and 10,000 kg of picnic at a c.i.f. price of 300 yen/kg. The importer has to report 10,000 kg of tenderloin imports and 10,000 kg of picnic imports separately at customs, therefore the total tariff will be 2,809,300 yen (800*10,000*0.043+(546.53-300)*10,000=2,809,300). However, if the same importer reports 20,000 kg of pork imports at a c.i.f. price of 550 yen/kg at customs (combining tenderloin and picnic), the total tariff will be as low as 473,000 yen (550*20,000*0.043=473,000). The latter is, well known, called a “combination import.” Thus, if a pork importer equates the c.i.f. price to the gate price by combining the expensive and cheap parts of pork, the company could easily minimize its tariff burden. However, in an official view, according to customs, undertaking combination imports in attempt of evading the tariff (i.e., if a pork importer mixes different types of pork for customs entry) is an illegal action and a penalty could be imposed. In practice, however, it is difficult to identify combination imports. Generally, a pork importer frequently imports many different cuts; thus, reporting all imports separately at customs is quite troublesome.

The regular safeguard

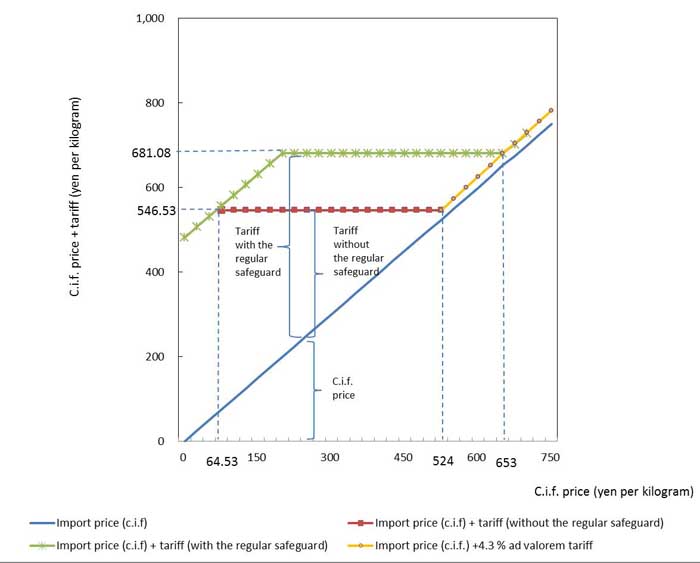

Fig. 2. shows the regular safeguard as follows.

Fig. 2. The regular safeguard for pork imports

(1) If the total amount of pork imports from the beginning of the fiscal year exceeds more than 119% of the average of the same quarter period from the beginning of the fiscal year for the prior three fiscal years, the gate price will be increased to 653 yen/kg from the following quarter until the end of the fiscal year. Please note that the Japanese fiscal year starts on April 1, ending on March 31 the following year.

(2) If the total volume of pork imports in the fiscal year exceeds more than 119% of the average of the total amount of pork imports in the prior three fiscal years, the gate price will be increased to 653 yen/kg in the first quarter of the next fiscal year.

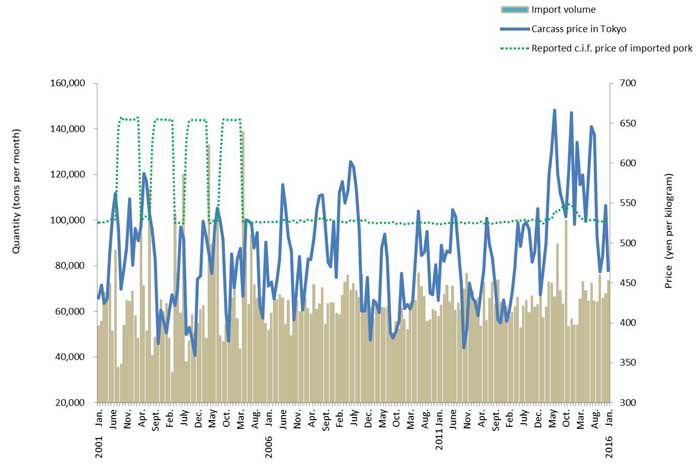

Reviewing Japan’s pork imports since 2001

Fig. 3. shows monthly data for last 15 years since 2001 with regard to the domestic pork carcass price, the reported c.i.f. prices of the imported pork, and the total amount of pork imports. In these 15 years, the regular safeguard was implemented in the four periods: from August 2011 to March 2012, from August 2012 to March 2013, from August 2013 to March 2014, and from August 2014 to March 2015.

Fig. 3. Pork carcass price in Tokyo, reported c.i.f. price, and imported volume of pork

The first two periods of the regular safeguard were implemented just after the outbreak of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy among cows in Japan. During these periods, because of anxiety about the safety of beef, consumers’ preference moved from beef to pork. The third and fourth periods of the regular safeguard were implemented just after the prohibition of beef imports from the US and chicken imports from China and Thailand. These prohibitions increased pork imports in order to cover the shortage of beef and chicken imports. These four cases show that pork can be consumed as a substitute for chicken and beef if an unfavorable event occurs in the beef and chicken markets in Japan. Thus, when considering the possibilities for the implementation of the regular safeguard, we must always need to take account of conditions not only in the pork market but also in the beef and chicken markets.

Fig. 3 presents a significant fact: The average of reported c.i.f. prices for imported pork is almost equivalent to the gate price (i.e., 654 yen/kg for the periods during which the regular safeguard was implemented and 524 yen/kg for the other periods), while the average price of domestically produced pork carcasses fluctuates irregularly. This is strong evidence for our view that customs gives tacit approval to combination imports (note 4).

It should be noted, however, that customs sometimes prosecutes pork importers on a charge of combination imports. For example, in 2012 the Special Investigation Department of the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office arrested Kunihiro Dodani and Kenji Shibata on suspicion of tariff evasion amounting to 13 billion yen of pork imports. Further, in 2009 the Special Investigation Department of the Nagoya District Public Prosecutors Office arrested Kazuo Akaogi on suspicion of tariff evasion amounting to 4.5 billion yen of pork imports. In addition, two major pork import companies, namely Narita Foods and the Mitsubishi Corporation, were revealed as having committed tariff evasion amounting to 6 billion yen in 2009 and 5 billion yen in 2008 respectively.

Experts in the pork business find that customs are rather arbitrary about judging whether each instance of pork imports is a combination import or not (note 5). While customs provides tacit approval to most combination imports, once customs has decided to pursue a specific instance of suspected tariff evasion, it surely levies a heavy penalty amount to the pork importer, as warning.

Impacts of the regular safeguards

As can be seen, in an ordinary time (i.e., when the regular safeguard is not implemented), pork is imported at the c.i.f. price of 524 yen/kg regardless of the domestic carcass price. This means that the tariff burden in ordinary times is 22.53 yen/kg (524*0.043=22.53). If the regular safeguard is implemented and a pork importer reports the c.i.f. price of 524 yen/kg, then the tariff burden is 157.08 yen/kg (681.08-524=157.08). In practice, however, a pork importer can minimize the tax burden by reporting the c.i.f. price of 654 yen/kg. This is achieved by changing the composition of the pork parts in combination imports. If pork is imported at the c.i.f. price of 654 yen/kg, the tax burden of importers is 28.13 yen/kg (654*0.043=28.13). Thus, the regular safeguard increases the tariff burden by only 5.6 yen/kg. This figure is just 7% of 524 yen/kg. Considering the large fluctuations in exchange rates, the impact of the tariff increase of 5.6% is insignificant.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the quantity of pork imports decreased significantly in the four the periods when the regular safeguard was implemented (see Figure 3). This is because pork importers need to make extra efforts in order to change the c.i.f. price from 524 yen/kg to 654 yen/kg. For example, a pork importer must increase a portion of the high-priced pork cuts (e.g., tenderloin) only during the period of the regular safeguard implementation. It is often the case that pork importers adopt complicated procedures by colluding with foreign collaborators in order to disguise their transactions as non-combination imports. However, frequent changes in the composition could increase the risk of difficulties between Japanese pork importers and foreign collaborators.

If a pork importer has trouble with a foreign collaborator, it could invite the authorities (e.g., customs) to start investigating the transactions with the foreign collaborator; then, combination imports are revealed. In sum, although the impact of the regular safeguard on the tariff burden is limited, the regular safeguard discourages pork imports by increasing the possibility for combination imports exposed.

Pork imports in the TPP agreement

The TPP members reached a new agreement on October 5, 2015. For Japan’s pork, there are three basic aspects of the agreement as follows.

- The gate price should be maintained at 524 yen/kg.

- The specific tariff should be reduced to 125 yen/kg from the first to the fourth year from when the TPP agreement becomes effective. For the fifth year, it will be reduced to 70 yen/kg and further reduced by 4 yen/kg every year from the sixth to the ninth year. For the tenth year and thereafter, it will be fixed at 50 yen/kg.

- The 4.3% ad valorem tariff should be reduced to 2.2% in the first year when the TPP agreement becomes effective. Then, within 10 years, it should be reduced to 0%.

These three conditions are for the periods when the TPP safeguard is not implemented. The conditions for implementation of the TPP safeguard are the same as those of the regular safeguard. However, the nature of the TPP safeguard differs from that of the regular safeguard as described below.

(S1) The gate price should be maintained at 524 yen/kg.

(S2) The ad valorem tariff should be 4.0% from the first to the third year from when the TPP agreement becomes effective. From the fourth to the sixth year, the tariff should be reduced to 3.4% and further reduced to 2.8% from the sixth to the ninth year. For the tenth year and thereafter, it will be fixed at 2.2%.

(S3) The specific tariff should not change from 125 yen/kg from the first to the fourth year from when the TPP agreement becomes effective. From the fifth to the ninth year, the specific tariff under the safeguard should be 100 yen/kg. For the tenth year and thereafter, it should be fixed at 70 yen/kg.

Comparison between the regular safeguard and the TPP safeguard

The authors estimate that the TPP agreement will not change the situation whereby a combination import is the most profitable import method for Japanese pork importers (note 6). In addition, as discussed above, customs has given tacit approval to combination imports for years. Thus, it would not be unreasonable to expect that combination imports will continue to represent the overwhelming portion of Japan’s pork imports even after the TPP agreement becomes effective. If so, the impact of the TPP will be limited. In that sense, TPP members will not have significant advantages over countries out of the TPP.

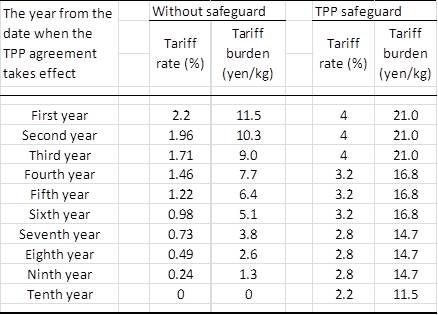

However, the story is different for the safeguard. Unlike the regular safeguard, pork importers in the TPP countries need not change the combination of pork parts because the gate price does not change in the TPP safeguard. In addition, the increase of the tariff burden under the TPP safeguard would also be limited (Table 1); namely, the tariff will increase by less than 5% of the gate price. In the context of large exchange rate fluctuations, 5% is negligible. In sum, the authors estimate that the TPP safeguard would be powerless against expected a sharp increase of pork imports from the TPP member countries.

Table 1. Tariff burden when pork is imported from the TPP member countries at the gate price of 524 yen/kg

Possible problems caused by the TPP safeguard

Japan is the world’s biggest pork importer. Its self-sufficiency rate for pork is only around 50%. Consequently, Japan imports pork from across the globe although the major pork exporters to Japan are the US, Canada, Mexico, Spain, and Denmark. Among these five countries, Spain and Denmark are not in the TPP. In order to stabilize its pork market, Japan must have a good relationship with the all five countries. In fact, we find that except for the agreement regarding the TPP safeguard, the TPP agreement on Japan’s pork imports will not provide a significant advantage to TPP member countries. The authors consider that this is one of the reasons why the Japanese government has made efforts to maintain the gate price system in the TPP agreement. However, the TPP safeguard is different. In the period of implementation of the safeguard, pork exporters outside the TPP will complain to the Japanese government. In addition, when they find that the TPP safeguard is ineffective in blocking against a sharp increase in pork imports, domestic pork producers will complain to the Japanese government.

The authors are unsure why the Japanese government has made such a problematic promise about its safeguard in the TPP negotiations. One way of understanding this situation is as follows. A patchwork of unsystematic import regulations can result in a difficult situation that even the government would have never expected. Japan’s TPP safeguard for pork imports can be seen as an example of such circumstances.

Notes

- If more than six countries, constituting over 85% of the total GDP of the 12 member countries, together complete the ratification procedures, and the remaining member countries fail to do so, the TPP agreement comes into effect by excluding these remaining countries.

- This brief history of the gate price system is taken from Godo, Yoshihisa “The Gate Price System for Japan’s Pork Imports,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region) March 28, 2014 (downloadable at http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=217).

- There are two types of pork for trading: one is cut meat and the other is carcass. The gate price for imported carcasses is 393 yen/kg. Since almost of all Japan’s pork imports are undertaken in cut meat, the authors have explained the gate price system only for the trading cut meat.

- In 2012, customs introduced a stricter policy for investigating combination imports (see Godo, “The Gate Price System for Japan’s Pork Imports”). This is why there are gaps between reported c.i.f. prices and gate prices around 2012 and 2013 in Figure 3. However, customs is gradually returning to the prior policy. Currently, the reported c.i.f. price has already returned to the gate price, as can be seen in Figure 3.

- See Shiga, Sakura, Buta Niku no Sagaku Kanzei Seido wo Danzai Suru, Paru Shuppan, 2011.

- Godo, Yoshihisa, and Hiroshi Takahashi, “Japan's Pork Imports: New Agreement in the Trans-Pacific Partnership Free Trade Negotiations,” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region) March 1, 2016 (downloadable at http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=586).

[*] We would like to thank Mr. Akira Shiratake for English language editing.

|

Date submitted: May 31, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June 1, 2016

|

A new agreement for Japan’s pork “safeguard” in the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations

Introduction

When pork imports increase sharply, the Japanese government is geared to implement a special measure for protecting domestic pork producers. This urgent and temporary measure is called a “safeguard.” In the ongoing Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade negotiations, the Japanese government has promised to introduce a new type of safeguard that is applicable only for the TPP member countries. However, the TPP agreement is still subject to ratification in each country and remaining uncertainty about when, and indeed whether, the new agreement will become effective (note 1). Once the agreement becomes effective, however, Japan will have two types of safeguard. One is the current safeguard, which will be applied to countries outside the TPP (the authors call this the “regular safeguard” hereafter). The other is the new safeguard, which Japan has promised to apply only to the TPP member countries (the authors call this the “TPP safeguard” hereafter).

After studying the details of the TPP agreement, the authors have found that the TPP safeguard is something different from the regular safeguard and thus would not be effective for preventing sharp increases in pork imports. In spite of these important finding, it is not widely recognized in Japan at this stage. The authors consider that this low degree of recognition could have originated from the complicated structure of Japan’s pork import system and insufficient transparency in the behavior of Japanese customs regarding to pork imports. In this paper, the authors explain the details of the TPP safeguard and discuss its impacts on the pork market.

The current framework for pork imports

Japan has a unique system, called the “gate price system”, for pork imports. The system’s outline is shown in Fig. 1. There is a critical price, called the “gate price”, whereby the method of accessing the tariff differs. Historically, the gate price was revised in accordance with changes of the domestic pork market conditions acting as “Variable levy” (note 2). Since 2000, however the gate price has been fixed at 524 yen/kg (note 3). If the cost, insurance, and freight (c.i.f.) price is higher than the gate price, customs would apply a 4.3% ad valorem tariff. If the former is lower than the latter, the tariff assessment is lower level of the following: (1) 482 yen/kg, and (2) the difference between 546.53 yen (the gate price multiplied by 1.043) and the c.i.f. price.

Fig. 1. Japan's current pork import system (in the period when the regular safeguard is not implemented)

Combination imports and the tariff evasion problem

While domestically produced pork is ordinary traded in carcass form, foreign pork is mainly traded in boxed meat (cuts). The price differs in accordance to the cuts. As a result, pork importers have a problem in reporting pork price to the customs. For example, if a pork importer intends to import 10,000 kg of tenderloin at a c.i.f. price of 800 yen/kg and 10,000 kg of picnic at a c.i.f. price of 300 yen/kg. The importer has to report 10,000 kg of tenderloin imports and 10,000 kg of picnic imports separately at customs, therefore the total tariff will be 2,809,300 yen (800*10,000*0.043+(546.53-300)*10,000=2,809,300). However, if the same importer reports 20,000 kg of pork imports at a c.i.f. price of 550 yen/kg at customs (combining tenderloin and picnic), the total tariff will be as low as 473,000 yen (550*20,000*0.043=473,000). The latter is, well known, called a “combination import.” Thus, if a pork importer equates the c.i.f. price to the gate price by combining the expensive and cheap parts of pork, the company could easily minimize its tariff burden. However, in an official view, according to customs, undertaking combination imports in attempt of evading the tariff (i.e., if a pork importer mixes different types of pork for customs entry) is an illegal action and a penalty could be imposed. In practice, however, it is difficult to identify combination imports. Generally, a pork importer frequently imports many different cuts; thus, reporting all imports separately at customs is quite troublesome.

The regular safeguard

Fig. 2. shows the regular safeguard as follows.

Fig. 2. The regular safeguard for pork imports

(1) If the total amount of pork imports from the beginning of the fiscal year exceeds more than 119% of the average of the same quarter period from the beginning of the fiscal year for the prior three fiscal years, the gate price will be increased to 653 yen/kg from the following quarter until the end of the fiscal year. Please note that the Japanese fiscal year starts on April 1, ending on March 31 the following year.

(2) If the total volume of pork imports in the fiscal year exceeds more than 119% of the average of the total amount of pork imports in the prior three fiscal years, the gate price will be increased to 653 yen/kg in the first quarter of the next fiscal year.

Reviewing Japan’s pork imports since 2001

Fig. 3. shows monthly data for last 15 years since 2001 with regard to the domestic pork carcass price, the reported c.i.f. prices of the imported pork, and the total amount of pork imports. In these 15 years, the regular safeguard was implemented in the four periods: from August 2011 to March 2012, from August 2012 to March 2013, from August 2013 to March 2014, and from August 2014 to March 2015.

Fig. 3. Pork carcass price in Tokyo, reported c.i.f. price, and imported volume of pork

The first two periods of the regular safeguard were implemented just after the outbreak of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy among cows in Japan. During these periods, because of anxiety about the safety of beef, consumers’ preference moved from beef to pork. The third and fourth periods of the regular safeguard were implemented just after the prohibition of beef imports from the US and chicken imports from China and Thailand. These prohibitions increased pork imports in order to cover the shortage of beef and chicken imports. These four cases show that pork can be consumed as a substitute for chicken and beef if an unfavorable event occurs in the beef and chicken markets in Japan. Thus, when considering the possibilities for the implementation of the regular safeguard, we must always need to take account of conditions not only in the pork market but also in the beef and chicken markets.

Fig. 3 presents a significant fact: The average of reported c.i.f. prices for imported pork is almost equivalent to the gate price (i.e., 654 yen/kg for the periods during which the regular safeguard was implemented and 524 yen/kg for the other periods), while the average price of domestically produced pork carcasses fluctuates irregularly. This is strong evidence for our view that customs gives tacit approval to combination imports (note 4).

It should be noted, however, that customs sometimes prosecutes pork importers on a charge of combination imports. For example, in 2012 the Special Investigation Department of the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office arrested Kunihiro Dodani and Kenji Shibata on suspicion of tariff evasion amounting to 13 billion yen of pork imports. Further, in 2009 the Special Investigation Department of the Nagoya District Public Prosecutors Office arrested Kazuo Akaogi on suspicion of tariff evasion amounting to 4.5 billion yen of pork imports. In addition, two major pork import companies, namely Narita Foods and the Mitsubishi Corporation, were revealed as having committed tariff evasion amounting to 6 billion yen in 2009 and 5 billion yen in 2008 respectively.

Experts in the pork business find that customs are rather arbitrary about judging whether each instance of pork imports is a combination import or not (note 5). While customs provides tacit approval to most combination imports, once customs has decided to pursue a specific instance of suspected tariff evasion, it surely levies a heavy penalty amount to the pork importer, as warning.

Impacts of the regular safeguards

As can be seen, in an ordinary time (i.e., when the regular safeguard is not implemented), pork is imported at the c.i.f. price of 524 yen/kg regardless of the domestic carcass price. This means that the tariff burden in ordinary times is 22.53 yen/kg (524*0.043=22.53). If the regular safeguard is implemented and a pork importer reports the c.i.f. price of 524 yen/kg, then the tariff burden is 157.08 yen/kg (681.08-524=157.08). In practice, however, a pork importer can minimize the tax burden by reporting the c.i.f. price of 654 yen/kg. This is achieved by changing the composition of the pork parts in combination imports. If pork is imported at the c.i.f. price of 654 yen/kg, the tax burden of importers is 28.13 yen/kg (654*0.043=28.13). Thus, the regular safeguard increases the tariff burden by only 5.6 yen/kg. This figure is just 7% of 524 yen/kg. Considering the large fluctuations in exchange rates, the impact of the tariff increase of 5.6% is insignificant.

Nonetheless, it should be noted that the quantity of pork imports decreased significantly in the four the periods when the regular safeguard was implemented (see Figure 3). This is because pork importers need to make extra efforts in order to change the c.i.f. price from 524 yen/kg to 654 yen/kg. For example, a pork importer must increase a portion of the high-priced pork cuts (e.g., tenderloin) only during the period of the regular safeguard implementation. It is often the case that pork importers adopt complicated procedures by colluding with foreign collaborators in order to disguise their transactions as non-combination imports. However, frequent changes in the composition could increase the risk of difficulties between Japanese pork importers and foreign collaborators.

If a pork importer has trouble with a foreign collaborator, it could invite the authorities (e.g., customs) to start investigating the transactions with the foreign collaborator; then, combination imports are revealed. In sum, although the impact of the regular safeguard on the tariff burden is limited, the regular safeguard discourages pork imports by increasing the possibility for combination imports exposed.

Pork imports in the TPP agreement

The TPP members reached a new agreement on October 5, 2015. For Japan’s pork, there are three basic aspects of the agreement as follows.

These three conditions are for the periods when the TPP safeguard is not implemented. The conditions for implementation of the TPP safeguard are the same as those of the regular safeguard. However, the nature of the TPP safeguard differs from that of the regular safeguard as described below.

(S1) The gate price should be maintained at 524 yen/kg.

(S2) The ad valorem tariff should be 4.0% from the first to the third year from when the TPP agreement becomes effective. From the fourth to the sixth year, the tariff should be reduced to 3.4% and further reduced to 2.8% from the sixth to the ninth year. For the tenth year and thereafter, it will be fixed at 2.2%.

(S3) The specific tariff should not change from 125 yen/kg from the first to the fourth year from when the TPP agreement becomes effective. From the fifth to the ninth year, the specific tariff under the safeguard should be 100 yen/kg. For the tenth year and thereafter, it should be fixed at 70 yen/kg.

Comparison between the regular safeguard and the TPP safeguard

The authors estimate that the TPP agreement will not change the situation whereby a combination import is the most profitable import method for Japanese pork importers (note 6). In addition, as discussed above, customs has given tacit approval to combination imports for years. Thus, it would not be unreasonable to expect that combination imports will continue to represent the overwhelming portion of Japan’s pork imports even after the TPP agreement becomes effective. If so, the impact of the TPP will be limited. In that sense, TPP members will not have significant advantages over countries out of the TPP.

However, the story is different for the safeguard. Unlike the regular safeguard, pork importers in the TPP countries need not change the combination of pork parts because the gate price does not change in the TPP safeguard. In addition, the increase of the tariff burden under the TPP safeguard would also be limited (Table 1); namely, the tariff will increase by less than 5% of the gate price. In the context of large exchange rate fluctuations, 5% is negligible. In sum, the authors estimate that the TPP safeguard would be powerless against expected a sharp increase of pork imports from the TPP member countries.

Table 1. Tariff burden when pork is imported from the TPP member countries at the gate price of 524 yen/kg

Possible problems caused by the TPP safeguard

Japan is the world’s biggest pork importer. Its self-sufficiency rate for pork is only around 50%. Consequently, Japan imports pork from across the globe although the major pork exporters to Japan are the US, Canada, Mexico, Spain, and Denmark. Among these five countries, Spain and Denmark are not in the TPP. In order to stabilize its pork market, Japan must have a good relationship with the all five countries. In fact, we find that except for the agreement regarding the TPP safeguard, the TPP agreement on Japan’s pork imports will not provide a significant advantage to TPP member countries. The authors consider that this is one of the reasons why the Japanese government has made efforts to maintain the gate price system in the TPP agreement. However, the TPP safeguard is different. In the period of implementation of the safeguard, pork exporters outside the TPP will complain to the Japanese government. In addition, when they find that the TPP safeguard is ineffective in blocking against a sharp increase in pork imports, domestic pork producers will complain to the Japanese government.

The authors are unsure why the Japanese government has made such a problematic promise about its safeguard in the TPP negotiations. One way of understanding this situation is as follows. A patchwork of unsystematic import regulations can result in a difficult situation that even the government would have never expected. Japan’s TPP safeguard for pork imports can be seen as an example of such circumstances.

Notes

[*] We would like to thank Mr. Akira Shiratake for English language editing.

Date submitted: May 31, 2016

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: June 1, 2016