Dr. Jeongbin Im

Professor

Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development

College of Agricultural and Life Science

Seoul National University

Seoul, Korea

E-mail: jeongbin@snu.ac.kr

1. Introduction

The total area of South Korea is 10,015 thousand hectares. Farmland makes up 17% of the country, forests 64% and others 19%. During the past 50 years, the total land area increased by 6%, whereas farmland has steadily declined. The decline in farmland, however, has been stagnant recently. The land area of South Korea represents only 0.1% of the world’s total land mass and just 0.22% of the Asian Continent. This article examines Korean farmland, related institutions and policies. The first to be looked into are distribution traits of farmland and state of farmland use, transformation of farmland institutions and policies resulting from changes in the socio-economic structure, and a variety of farmland related laws that affect ownership and use of farmland. Also, we will analyze the current state of farmland mobilization which has been pushed aggressively as a policy to reform the agricultural system in order to create large-scale faming in preparation of expanding agricultural market liberalization. Lastly, we will discuss the following major pending issues of farmland policy while forecasting circumstantial changes in the use of farmland in the future: laying the principles of ownership and use of farmland, management of idle farmland, stable securement of farmland for future farmers, farmland price stabilization, and prevention of thoughtless development.

2. Situations of agricultural land

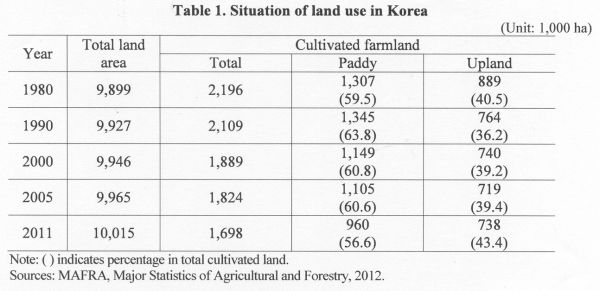

As of the end of 2011, the total size of South Korea's national territory is 10,015,000 ha, and 1,698,000 ha, or 17% of the territory, is farmland. The farmland is further divided into 960,000 ha of paddy fields and 738,000 ha of upland fields. Farmland is also classified into two types of agricultural land: agriculture-promoted area and others according to whether or not it is designated as agriculture-promoted area, which belongs to the same category as preserved farmland. The size of agriculture-promoted areas is 807,000 ha, or 47.5% of total farmland, whereas the farmland that has not been designated as agriculture-promoted area is 891,000 ha. The size of agriculture-promoted areas had decreased dramatically when the promotion of agriculture areas stopped in 2004.

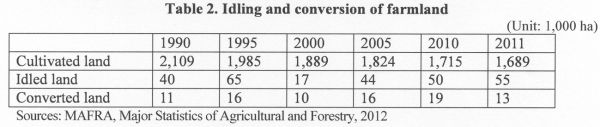

Korea's average cultivated land per farm household is 1.46ha, which is very small scale farming compared to other countries. Therefore, food sufficiency rate is very low. Although the self-sufficiency rate of rice, the staple crop, is almost 100% because of government investment in the production base and decline in rice consumption, the self-sufficiency rate of grains as a whole is merely 23% in 2011. Despite the low self-sufficiency rate of food, a considerable amount of farmland has become idled or transferred to non-agricultural use, and such a trend is projected to continue. In recent years, about 40,000 ha of farmland have become idle every year, and much of the deserted land have been turned into a land that is difficult to use again because generally they are not used as farmland for a long time. Apart from the idling of farmland, about 20,000 ha of farmland are converted to other uses every year. As a result, farmland continues to decrease despite of various efforts to create and preserve farmland.

3. Historical perspectives and change of farmland policy

3.1 Major contents of farmland related acts

According to the current Farmland Act Article 3, Farmland is the foundation for supplying food and preserving the territorial environment of the country. Since it is a precious resource that has influence on balanced development of agriculture and national economy, it should not only be preserved carefully, but properly managed in tune with the public interest, and the exercise of rights impose necessary restrictions and obligations. The law explicitly states that“farmland cannot be owned by anyone other than those who use it or intend to use it for farming of his or her ownself” Specifically, the law has adopted an acquisition qualification system titled “Issuance of Qualification Certificate for Acquisition of Farmland” and authorizes the acquisition of farmland to only eligible applicants after checking and examining the eligibility and ownership ceiling of a prospective buyer. The law has also adopted “Disposition Order” and “Charge of Forcing Execution”as post-management tools to handle the failure to comply with the original purpose of the acquisition. In other words, the land-to-tiller principle forms the basis of farmland ownership and use in Korea.

Such a farmland ownership and usage system that centers on farmers who own farmland was established through a farmland reform in accordance with the Farmland Reform Act of 1949 and forms the basis of today's farmland system. The main purpose of the Farmland Reform Act was to end the abuses of the past landlord-tenant system and foster self-employed farmers as a means to build a stable social foundation. Specifically, the government created self-employed farmers by buying the farmlands of landlords and distributing a maximum of 3 ha of farmland to actual farmers. Acquisition of farmland by non-farmers and ownership of more than 3 ha of farmland were restricted, and the government regulated the acquisition of farmland by issuing farmland transaction certificates. The basic structure of“upper limit of farmland ownership”and“farmland transaction certification”has been maintained until recently.

In the 1960s and 1970s, physical expansion of farmland through reclamation and restoration of land was at the center of agricultural policy to address the food shortage resulting from the division of South and North Korea and the subsequent Korean War. The farmland expansion policy was implemented together with the enactment of Reclamation Promotion Act in 1962 to accelerate the development of uncultivated mountainous areas. In 1967, Farmland Development Act was enacted. In the case of Farmland Development Act, development was limited due to high financial burden on landowners. After the global food crisis in 1974, Farmland Expansion and Development Promotion Act was enacted in 1975.

Since the late 1960s, the use of farmland for purposes other than farming increased rapidly due to urbanization and industrialization, and in the 1970s, the world experienced an oil crisis and food shortage. Alarmed by these challenges, the government enacted Farmland Preservation and Utilization Act in 1972 and strictly restricted the diversion of farmland for non-agricultural purposes. The core content of this law was to selectively protect farmland by designating them as“absolute farmland”and“relative farmland.”Absolute farmland was designated for mostly rice paddies and other farmland that need to be strictly protected, and “relative farmland” for other types of farmland. The government also required anyone who intends to use farmland for other purposes to obtain government permission and pay a fee to Farmland Management Fund to bear the“farmland creation cost” in making alternative land available for farming. During this period, the government’s will to preserve farmland was stronger than in any other period.

However, the number of non-farmers owning farmland rose due to desertion of farming and inheritance of farmland, and farmland price rose and became higher relative to the profitability of farming. As these problems emerged, it became difficult to follow the land-to-tiller principle. Accordingly, the realistic question of whether or not to recognize and authorize the legally banned farmland lease from the perspective of reforming the agricultural structure attracted attention and prompted the legislation of Farmland Lend-Lease Management Act in 1986.

In addition to the discussions in the late 1980s and afterward on further opening of the domestic agricultural market, the need to foster competitive agricultural enterprises was raised. As a result, the Act on Special Measures for Development of Agricultural and Fishing Villages was enacted and enforced, authorizing farmland ownership of agricultural enterprises and relaxing regulations on farmland. The Farmland Reform Act of 1949 did not allow farmland ownership of enterprises, but rather recognized the ownership and use of farmland by self-employed family farms. The authorization of farmland ownership of enterprises was a big change. Also, the means of preserving farmland, too, has changed. The plot-based farmland preservation system of designating absolute and relative farmland was abolished and a new system of designating good collectivized farmland as “agricultural development region”was introduced, replacing the plot-based system which was introduced in 1972. In other words, the plot-based farmland preservation system has been converted to region-based farmland preservation system. In addition, the government eased restrictions on farmland use and conversion and raised the ownership ceiling to 10 ha from 3 ha to flexibly respond to agricultural imports.

Also, the Farmland Act was enacted in 1994 by combining all the preexisting laws related to farmland, such as Farmland Reform Act (1949), Farmland Preservation and Utilization Act (1972), Farmland Lend-Lease Management Act (1986), and Rural Development Special Act (1990). The Farmland Act, which is a comprehensive legal system related to farmland, was implemented in 1996 and is currently in force today.

Even though Farmland Act clearly stipulates strict compliance with the land-to-tiller principle, regulations on ownership and use of farmland have been greatly eased in accordance with changes in socio-economic circumstances. Restrictions on farmland ownership were reduced greatly, too. An amendment to the Farmland Act in 2003 enabled non-farmers to own a land of less than 1,000m2 for the purpose of using it to experience farming or as a weekend farm. Also, a farmland bank was introduced in 2005. As a result, it became possible for non-farmers to own a limited amount of farmland if they lease it to the farmland bank on a long-term basis. Such an authorization of farmland ownership partially broke the principle that strictly restricted farmland ownership for reasons other than farming, and brought about a de facto effect of allowing non-farmers to own farmland. Also, the scope of authorized farmland ownership was further expanded and it became possible for agricultural stock company to own farmland.

In the meantime, the ownership ceiling of 10 ha of farmland in agriculture-promoted regions under the Farmland Reform Act was raised to 20 ha on condition of approval by municipal governments of cities and counties. In 1999, the ownership ceiling itself was abolished for farmlands in agriculture-promoted regions. Ownership limit for farmland outside of agriculture-promoted regions was expanded to 5 ha in 1999, but was abolished in 2002 after 50 years in existence.

In regard to land ownership as indicated above, the Constitution and the Farmland Act clearly state the land-to-tiller principle:“The farmland shall not be owned by any person unless he or she uses it or is going to use it for their own purpose of managing agriculture.” However, even though farmland ownership is limited to farmers and agricultural enterprises, there are exceptions for non-farmers who happen to own farmland as a result of people leaving the farming profession and people inheriting the land. Also, exceptions are granted to those non-farmers who use farmland to have experience in farming and who use it as a weekend farm under the condition that the farmland does not exceed a certain size.

Although the Constitution prohibits the semi-feudal tenant farming, lease and entrusted management of farmland are allowed on a limited basis according to law. The Farmland Act allows leasing of farmland if the ownership of the farmland to be leased changed hands due to migration of farmers or succession to property. In 2005, the Farmland Act was revised and the revised law granted the Korea Rural Community Corporation the right to perform the role of a farmland bank. If farmland is entrusted to the bank for long-term lease, all were allowed to lease the entrusted farmland. With the introduction of such a farmland banking system, farmland lease is expected to increase significantly.

In regard to preservation of farmland, the government introduced a prime farmland designation system to preserve premium farmland that has been rearranged or collectivized. The system requires permission, registration and consultation to convert farmland for non-farming purposes. In the case of collectivized high-quality farmland that are designated as prime farmland, the government restricts farmland conversion except for installation and construction of agricultural facilities and social infrastructure to help preserve the farmland.

Meanwhile, the National Territory Planning Act manages the development and preservation of the entire national territory by specifying and placing different zones and restrictions based on a zoning system. The farmland management system was transformed as the Act on the Planning and Utilization of the National Territory was enacted on January 1, 2003. The new law was created by combining the Act on the Utilization and Management of the National Territory with the Urban Planning Act. Of the existing five zones, semi-urban and semi-agricultural zones were integrated into“management zones,”and“management zones”were subdivided again into“planned management zones,”“production management zones” and “preservation management zones.” Farmlands in general are found mainly in “agricultural zones” and “production management zones.

3.2. Use and conversion of farmland

Amid an overall decline in the size of cultivated land, the number of farms fell sharply, whereas cultivation area decreased relatively gradually. As a result, average size of cultivated land per farm increased from 0.93 ha in 1970 to 1.19 ha in 1990, 1.37 ha in 2000 and to 1.46 ha in 2011. A structural change in the size of farmland cultivated by farm household took place around after the farmland reform. From 1965 to 1990, the numbers of small farms and relatively big farms decreased continuously, whereas mid-size farms increased. However, a polarized distribution of cultivated land began to appear since the 1990s. The ratio of mid-size farms with a cultivated land of 0.5~2.0 ha decreased, whereas farms with cultivated land of less than 0.5 ha and over 2 ha increased in comparison. While average size of cultivated land per farm is increasing slowly, the concentration of farmland to relatively big farms is increasing at a fairly rapid pace. However, the size of cultivated land per farm still remains small.

Meanwhile, the ratio of leased farms rose from 17.8% in 1970 to 37.4% in 1990 and to 47.3% in 2011 even though the Farmland Act prohibits farmland leasing. In terms of ownership of leased farmland, only about 20% of leased farmland is owned by farmers, whereas 60~70% of leased farmland is owned by non-farmers. The reason for the rise in farmland lease is that, on one hand, farmland ownership by non-farmers has increased due to farmers leaving the profession and non-farmers inheriting the land and, on the other hand, most farms are expanding their business scale by leasing relatively economical farmland than buying high-priced farmland.

Farmland has continuously decreased since 1968 due to conversion of farmland resulting from urbanization and industrialization. In the course of rapid economic growth, farmland was converted to other uses, such as housing, commercial-industrial, and public space, at a high rate as population grew and urbanization and industrialization progressed. In addition, the worsening conditions for agriculture have steadily increased the amount of idle farmland. Accordingly, farmland was reduced from 2,298 thousand ha in 1970 to 1,698 thousand ha in 2011.

Currently, idle farmland is larger than converted farmland. During the early to mid-1990s, there were cases where idle farmland was two to three times larger than converted farmland. Caused by inadequate maintenance of production infrastructure and shortage of labor, the amount of idle farmland increased greatly due to further opening of the domestic agricultural market and reduction in rice consumption. In the future, too, idle farmland is expected to grow since the circumstances for farming are likely to worsen due to further opening of agricultural markets through FTAs with major trading partners.

Today's problem with farmland conversion is that even prime farmland is being converted to other uses in large scale. If we look at the trend of farmland conversion by type of land use, public use in general accounts for the largest share of the conversion, whereas the use for agricultural facilities accounts for only a small portion except in the early and mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. The early and mid-1990s was a period when restrictions on farmland conversion were eased greatly. Farmland conversion for agricultural use increased a lot as the period coincided with the expansion of greenhouse agriculture. But in 2011, only 5% of converted farmland was used for the installation of facilities for agriculture and fisheries.

3.3 Farmland mobilization policy

Farmland mobilization accelerates the business expansion-driven improvement of agricultural structure, and farmland mobilization tasks are carried out through the Farm Scale Expansion Project and the Farmland Banking Project. The Farm Scale Expansion Project began in 1990 as a central project contributing to mobilizing farmland. Also, the Farmland Banking Project was launched to cope with changes in the agricultural market environment home and abroad, such as further opening of the domestic agricultural market, reduction of farming population, and aging of farmers. The project began with the revision of Farmland Act in July 2005, the contents of which included the function of farmland banking. The Farm Scale Expansion Project, which had been carried out as a separate project from the farmland banking project, is currently managed as part of the banking project.

The Farmland Banking Project is carried out to optimize the scale of farming, promote efficient use of farmland, improve the agricultural structure, and stabilize the farmland market and farmers's income. According to Article 10 of the Law on Korea Rural Community Corporation and Farmland Management Fund, farmland banking project activities are as follows: ① sales, lease, exchange, and separation and merger of farmland; ② supply of information about farmland price and transaction trends; ③ farmland purchase to assist revival of farming; ④ leasing of entrusted farmland; and ⑤ assistance to stabilize the income of retired farmers with farmland as collateral. But the actual activities performed in regard to farmland mobilization are farm-scale expansion, sale and lease of entrusted farmland, and purchase of farmland.

The Farm Scale Expansion Project began in July, 1990 to increase farm scale, promote farmland collectivization, reduce production cost, and increase competitiveness through farmland sale, long-term lease, and exchange of farmland. Since then, it has gone through changes with respect to project goal, eligibility for assistance, loan rate and others. Then in December 2004, a comprehensive program for the rice industry was launched with the goal of creating 70,000 rice farms. Under the program, each farm will have 6 ha of rice field, and the rice farms will take charge of half (420,000 ha) of rice fields in Korea by 2013. But in 1997, when a direct payment was launched to subsidize old retired farmers who transferred their farmland, the implementation of the farm scale expansion project was changed from purchasing of farmland to leasing of farmland.

The farmland lease project is for leasing entrusted farmland to full-time farmers on a long-term basis. The leasable farmland here refers to rice paddies, coarse farmland, orchards and facilities attached to entrusted farmland, all of which are actually used for farming. The lease period is five years, and the rent paid each year is determined between the farmland bank and the lessee. The bank then pays the rent to the lessor after deducting 8-12% from the rent as a commission.

Buying and stockpiling farmland is a key function of the farmland banking project. Farmlands are bought and stockpiled when farmland price is expected to fall due to a rise in the amount of farmland on sale resulting from a sharp drop in the number of farmers, and especially when farmers are expected to suffer a big loss due to a big price fall of prime farmland in agriculture-promoted areas where the demand for farmland for non-agricultural use is low. The farmland banking project aims to stabilize the farmland market, accelerate the improvement of agricultural structure, and preserve farmland, as well as cope flexibly with the demand for farmland for non-agricultural use and foster large-scale agricultural businesses. The farmlands bought under the project are farmlands in agriculture-promoted areas and were previously owned by farmers retiring or leaving the business. The farmlands are leased on a long-term basis under the principle that farmland ownership is maintained and selling it is exercised on a limited basis to stabilize the farmland market. Those persons and entities who are eligible to lease farmland are individuals or companies that intend to work at farming, and the principle that lease period is over five years should be maintained. This project has been in progress since 2010.

4. Future tasks of farmland policy

As the proceeding of agricultural trade liberalization, the agribusiness conditions have worsened. As a result, the amount of idle farmland has been increasing and this trend is expected to continue in the future, too. The total farmland size is also expected to continue decreasing along with the rise in the amount of farmland being converted to other uses. The amount of farmland either owned by non-farmers or leased is also expected to rise due to deregulation of ownership and use of farmland. The situation is that it is necessary to continue making efforts to increase the farm scale per farm as part of the effort to improve competitiveness. And it is expected that leasing farmland will be a more preferred method of increasing the cultivated land per farm over purchasing farmland.

In addition to such circumstantial changes, various pending issues related to the current farmland policy are expected to remain as major tasks that need to be performed in the near future, too. What comes to mind as a primary task concerning the current farmland problem is how to legitimize the disparity between the reality of increasing ownership and use of farmland by non-farmers and the ideal of the land-to-tiller principle stated in the Constitution and the Farmland Act. The perception is spreading that the present farmland system, which allows only farmers to own their farmland, should be rectified to better suit the reality and that it is no longer viable to adhere to the land-to-tiller principle when farmland price is relatively high. There is even an argument that abandoning the land-to-tiller principle and fully authorizing farmland lease is more advantageous to improving the agricultural structure. In this respect, the question as to how to actively utilize farmland banking becomes a major pending issue as it requires a realistic approach to enable relatively competitive professional farmers to secure more farmland in a more stable manner.

The second policy task is to find an effective way how to secure an appropriate amount of farmland needed to supply a base for stable food to the public under the current condition of low food self-sufficiency rate below 30% and with growing idle farmland. On the one hand, there is a need to ease farmland regulations for the efficient use of idle farmland while, on the other hand, there is a need to preserve and manage farmland to build a base for stable food security in preparation for food crisis era. Under such circumstances, voices are raised on the need to reach a social consensus on preserving an optimum amount of farmland and the need to seek ways of managing idle farmland and securing farmland that can be utilized in times of food crisis.

Thirdly, the reality is that about 60% of farmers are aged 60 years or more and that most farms have not yet secured new farmers who can succeed their farming business. In view of the situation, it is necessary to actively seek policies that can improve conditions for retiring and selling farmland and that can help future farmers secure farmland. Allowing non-farmers to buy farmland will enable real estate speculators to obtain farmland and thus encourage speculation and make it difficult for farmers to secure farmland with ease. Possession of farmland for speculative purpose can prevent farmers from acquiring land on lease and make it difficult for them to efficiently and stably use their farmland. Measures should be found to improve the liquidity of farmland and supply farmland to future farmers while avoiding these problems.

Fourthly, change of thinking is needed concerning the policy on farmland price. Under the current circumstances where most farmers want to see farmland price rise and demand that non-farmers be allowed to buy farmland freely, the government policy of preserving farmland and stabilizing farmland price will face many difficulties. Even though farmland price in suburban areas can skyrocket with the deregulation of farmland, farmland price in rural areas will fall because of deterioration of net profit of farming, and this will cause problems in maintaining the asset value of farms and lower the ability to pay back debts. Accordingly, the problem of maintaining farmland price at an appropriate level is expected to emerge as a new policy agenda.

Finally, under the current environment where the multi-functionality of agriculture and rural community is stressed, planned management of rural space and prevention of thoughtless development have become major challenges. Important rural amenity resources are disappearing due to emergence of buildings that do not blend with the landscape, livestock barns that are not in harmony with the plough and sowing of agriculture, and various facilities installed randomly in different locations. As this problem is related with farmland conversion and planned management of space, it is necessary to seek a comprehensive way to manage rural space under the sophisticated plan. For instance, various action plans, such as the adoption of the‘plan before development’ principle, are required to prevent imprudent development and indiscreet use of farmland.

|

Date submitted: July 27, 2013

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: August 6, 2013

|

Farmland Policies of Korea

Dr. Jeongbin Im

Professor

Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development

College of Agricultural and Life Science

Seoul National University

Seoul, Korea

E-mail: jeongbin@snu.ac.kr

1. Introduction

The total area of South Korea is 10,015 thousand hectares. Farmland makes up 17% of the country, forests 64% and others 19%. During the past 50 years, the total land area increased by 6%, whereas farmland has steadily declined. The decline in farmland, however, has been stagnant recently. The land area of South Korea represents only 0.1% of the world’s total land mass and just 0.22% of the Asian Continent. This article examines Korean farmland, related institutions and policies. The first to be looked into are distribution traits of farmland and state of farmland use, transformation of farmland institutions and policies resulting from changes in the socio-economic structure, and a variety of farmland related laws that affect ownership and use of farmland. Also, we will analyze the current state of farmland mobilization which has been pushed aggressively as a policy to reform the agricultural system in order to create large-scale faming in preparation of expanding agricultural market liberalization. Lastly, we will discuss the following major pending issues of farmland policy while forecasting circumstantial changes in the use of farmland in the future: laying the principles of ownership and use of farmland, management of idle farmland, stable securement of farmland for future farmers, farmland price stabilization, and prevention of thoughtless development.

2. Situations of agricultural land

As of the end of 2011, the total size of South Korea's national territory is 10,015,000 ha, and 1,698,000 ha, or 17% of the territory, is farmland. The farmland is further divided into 960,000 ha of paddy fields and 738,000 ha of upland fields. Farmland is also classified into two types of agricultural land: agriculture-promoted area and others according to whether or not it is designated as agriculture-promoted area, which belongs to the same category as preserved farmland. The size of agriculture-promoted areas is 807,000 ha, or 47.5% of total farmland, whereas the farmland that has not been designated as agriculture-promoted area is 891,000 ha. The size of agriculture-promoted areas had decreased dramatically when the promotion of agriculture areas stopped in 2004.

Korea's average cultivated land per farm household is 1.46ha, which is very small scale farming compared to other countries. Therefore, food sufficiency rate is very low. Although the self-sufficiency rate of rice, the staple crop, is almost 100% because of government investment in the production base and decline in rice consumption, the self-sufficiency rate of grains as a whole is merely 23% in 2011. Despite the low self-sufficiency rate of food, a considerable amount of farmland has become idled or transferred to non-agricultural use, and such a trend is projected to continue. In recent years, about 40,000 ha of farmland have become idle every year, and much of the deserted land have been turned into a land that is difficult to use again because generally they are not used as farmland for a long time. Apart from the idling of farmland, about 20,000 ha of farmland are converted to other uses every year. As a result, farmland continues to decrease despite of various efforts to create and preserve farmland.

3. Historical perspectives and change of farmland policy

3.1 Major contents of farmland related acts

According to the current Farmland Act Article 3, Farmland is the foundation for supplying food and preserving the territorial environment of the country. Since it is a precious resource that has influence on balanced development of agriculture and national economy, it should not only be preserved carefully, but properly managed in tune with the public interest, and the exercise of rights impose necessary restrictions and obligations. The law explicitly states that“farmland cannot be owned by anyone other than those who use it or intend to use it for farming of his or her ownself” Specifically, the law has adopted an acquisition qualification system titled “Issuance of Qualification Certificate for Acquisition of Farmland” and authorizes the acquisition of farmland to only eligible applicants after checking and examining the eligibility and ownership ceiling of a prospective buyer. The law has also adopted “Disposition Order” and “Charge of Forcing Execution”as post-management tools to handle the failure to comply with the original purpose of the acquisition. In other words, the land-to-tiller principle forms the basis of farmland ownership and use in Korea.

Such a farmland ownership and usage system that centers on farmers who own farmland was established through a farmland reform in accordance with the Farmland Reform Act of 1949 and forms the basis of today's farmland system. The main purpose of the Farmland Reform Act was to end the abuses of the past landlord-tenant system and foster self-employed farmers as a means to build a stable social foundation. Specifically, the government created self-employed farmers by buying the farmlands of landlords and distributing a maximum of 3 ha of farmland to actual farmers. Acquisition of farmland by non-farmers and ownership of more than 3 ha of farmland were restricted, and the government regulated the acquisition of farmland by issuing farmland transaction certificates. The basic structure of“upper limit of farmland ownership”and“farmland transaction certification”has been maintained until recently.

In the 1960s and 1970s, physical expansion of farmland through reclamation and restoration of land was at the center of agricultural policy to address the food shortage resulting from the division of South and North Korea and the subsequent Korean War. The farmland expansion policy was implemented together with the enactment of Reclamation Promotion Act in 1962 to accelerate the development of uncultivated mountainous areas. In 1967, Farmland Development Act was enacted. In the case of Farmland Development Act, development was limited due to high financial burden on landowners. After the global food crisis in 1974, Farmland Expansion and Development Promotion Act was enacted in 1975.

Since the late 1960s, the use of farmland for purposes other than farming increased rapidly due to urbanization and industrialization, and in the 1970s, the world experienced an oil crisis and food shortage. Alarmed by these challenges, the government enacted Farmland Preservation and Utilization Act in 1972 and strictly restricted the diversion of farmland for non-agricultural purposes. The core content of this law was to selectively protect farmland by designating them as“absolute farmland”and“relative farmland.”Absolute farmland was designated for mostly rice paddies and other farmland that need to be strictly protected, and “relative farmland” for other types of farmland. The government also required anyone who intends to use farmland for other purposes to obtain government permission and pay a fee to Farmland Management Fund to bear the“farmland creation cost” in making alternative land available for farming. During this period, the government’s will to preserve farmland was stronger than in any other period.

However, the number of non-farmers owning farmland rose due to desertion of farming and inheritance of farmland, and farmland price rose and became higher relative to the profitability of farming. As these problems emerged, it became difficult to follow the land-to-tiller principle. Accordingly, the realistic question of whether or not to recognize and authorize the legally banned farmland lease from the perspective of reforming the agricultural structure attracted attention and prompted the legislation of Farmland Lend-Lease Management Act in 1986.

In addition to the discussions in the late 1980s and afterward on further opening of the domestic agricultural market, the need to foster competitive agricultural enterprises was raised. As a result, the Act on Special Measures for Development of Agricultural and Fishing Villages was enacted and enforced, authorizing farmland ownership of agricultural enterprises and relaxing regulations on farmland. The Farmland Reform Act of 1949 did not allow farmland ownership of enterprises, but rather recognized the ownership and use of farmland by self-employed family farms. The authorization of farmland ownership of enterprises was a big change. Also, the means of preserving farmland, too, has changed. The plot-based farmland preservation system of designating absolute and relative farmland was abolished and a new system of designating good collectivized farmland as “agricultural development region”was introduced, replacing the plot-based system which was introduced in 1972. In other words, the plot-based farmland preservation system has been converted to region-based farmland preservation system. In addition, the government eased restrictions on farmland use and conversion and raised the ownership ceiling to 10 ha from 3 ha to flexibly respond to agricultural imports.

Also, the Farmland Act was enacted in 1994 by combining all the preexisting laws related to farmland, such as Farmland Reform Act (1949), Farmland Preservation and Utilization Act (1972), Farmland Lend-Lease Management Act (1986), and Rural Development Special Act (1990). The Farmland Act, which is a comprehensive legal system related to farmland, was implemented in 1996 and is currently in force today.

Even though Farmland Act clearly stipulates strict compliance with the land-to-tiller principle, regulations on ownership and use of farmland have been greatly eased in accordance with changes in socio-economic circumstances. Restrictions on farmland ownership were reduced greatly, too. An amendment to the Farmland Act in 2003 enabled non-farmers to own a land of less than 1,000m2 for the purpose of using it to experience farming or as a weekend farm. Also, a farmland bank was introduced in 2005. As a result, it became possible for non-farmers to own a limited amount of farmland if they lease it to the farmland bank on a long-term basis. Such an authorization of farmland ownership partially broke the principle that strictly restricted farmland ownership for reasons other than farming, and brought about a de facto effect of allowing non-farmers to own farmland. Also, the scope of authorized farmland ownership was further expanded and it became possible for agricultural stock company to own farmland.

In the meantime, the ownership ceiling of 10 ha of farmland in agriculture-promoted regions under the Farmland Reform Act was raised to 20 ha on condition of approval by municipal governments of cities and counties. In 1999, the ownership ceiling itself was abolished for farmlands in agriculture-promoted regions. Ownership limit for farmland outside of agriculture-promoted regions was expanded to 5 ha in 1999, but was abolished in 2002 after 50 years in existence.

In regard to land ownership as indicated above, the Constitution and the Farmland Act clearly state the land-to-tiller principle:“The farmland shall not be owned by any person unless he or she uses it or is going to use it for their own purpose of managing agriculture.” However, even though farmland ownership is limited to farmers and agricultural enterprises, there are exceptions for non-farmers who happen to own farmland as a result of people leaving the farming profession and people inheriting the land. Also, exceptions are granted to those non-farmers who use farmland to have experience in farming and who use it as a weekend farm under the condition that the farmland does not exceed a certain size.

Although the Constitution prohibits the semi-feudal tenant farming, lease and entrusted management of farmland are allowed on a limited basis according to law. The Farmland Act allows leasing of farmland if the ownership of the farmland to be leased changed hands due to migration of farmers or succession to property. In 2005, the Farmland Act was revised and the revised law granted the Korea Rural Community Corporation the right to perform the role of a farmland bank. If farmland is entrusted to the bank for long-term lease, all were allowed to lease the entrusted farmland. With the introduction of such a farmland banking system, farmland lease is expected to increase significantly.

In regard to preservation of farmland, the government introduced a prime farmland designation system to preserve premium farmland that has been rearranged or collectivized. The system requires permission, registration and consultation to convert farmland for non-farming purposes. In the case of collectivized high-quality farmland that are designated as prime farmland, the government restricts farmland conversion except for installation and construction of agricultural facilities and social infrastructure to help preserve the farmland.

Meanwhile, the National Territory Planning Act manages the development and preservation of the entire national territory by specifying and placing different zones and restrictions based on a zoning system. The farmland management system was transformed as the Act on the Planning and Utilization of the National Territory was enacted on January 1, 2003. The new law was created by combining the Act on the Utilization and Management of the National Territory with the Urban Planning Act. Of the existing five zones, semi-urban and semi-agricultural zones were integrated into“management zones,”and“management zones”were subdivided again into“planned management zones,”“production management zones” and “preservation management zones.” Farmlands in general are found mainly in “agricultural zones” and “production management zones.

3.2. Use and conversion of farmland

Amid an overall decline in the size of cultivated land, the number of farms fell sharply, whereas cultivation area decreased relatively gradually. As a result, average size of cultivated land per farm increased from 0.93 ha in 1970 to 1.19 ha in 1990, 1.37 ha in 2000 and to 1.46 ha in 2011. A structural change in the size of farmland cultivated by farm household took place around after the farmland reform. From 1965 to 1990, the numbers of small farms and relatively big farms decreased continuously, whereas mid-size farms increased. However, a polarized distribution of cultivated land began to appear since the 1990s. The ratio of mid-size farms with a cultivated land of 0.5~2.0 ha decreased, whereas farms with cultivated land of less than 0.5 ha and over 2 ha increased in comparison. While average size of cultivated land per farm is increasing slowly, the concentration of farmland to relatively big farms is increasing at a fairly rapid pace. However, the size of cultivated land per farm still remains small.

Meanwhile, the ratio of leased farms rose from 17.8% in 1970 to 37.4% in 1990 and to 47.3% in 2011 even though the Farmland Act prohibits farmland leasing. In terms of ownership of leased farmland, only about 20% of leased farmland is owned by farmers, whereas 60~70% of leased farmland is owned by non-farmers. The reason for the rise in farmland lease is that, on one hand, farmland ownership by non-farmers has increased due to farmers leaving the profession and non-farmers inheriting the land and, on the other hand, most farms are expanding their business scale by leasing relatively economical farmland than buying high-priced farmland.

Farmland has continuously decreased since 1968 due to conversion of farmland resulting from urbanization and industrialization. In the course of rapid economic growth, farmland was converted to other uses, such as housing, commercial-industrial, and public space, at a high rate as population grew and urbanization and industrialization progressed. In addition, the worsening conditions for agriculture have steadily increased the amount of idle farmland. Accordingly, farmland was reduced from 2,298 thousand ha in 1970 to 1,698 thousand ha in 2011.

Currently, idle farmland is larger than converted farmland. During the early to mid-1990s, there were cases where idle farmland was two to three times larger than converted farmland. Caused by inadequate maintenance of production infrastructure and shortage of labor, the amount of idle farmland increased greatly due to further opening of the domestic agricultural market and reduction in rice consumption. In the future, too, idle farmland is expected to grow since the circumstances for farming are likely to worsen due to further opening of agricultural markets through FTAs with major trading partners.

Today's problem with farmland conversion is that even prime farmland is being converted to other uses in large scale. If we look at the trend of farmland conversion by type of land use, public use in general accounts for the largest share of the conversion, whereas the use for agricultural facilities accounts for only a small portion except in the early and mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. The early and mid-1990s was a period when restrictions on farmland conversion were eased greatly. Farmland conversion for agricultural use increased a lot as the period coincided with the expansion of greenhouse agriculture. But in 2011, only 5% of converted farmland was used for the installation of facilities for agriculture and fisheries.

3.3 Farmland mobilization policy

Farmland mobilization accelerates the business expansion-driven improvement of agricultural structure, and farmland mobilization tasks are carried out through the Farm Scale Expansion Project and the Farmland Banking Project. The Farm Scale Expansion Project began in 1990 as a central project contributing to mobilizing farmland. Also, the Farmland Banking Project was launched to cope with changes in the agricultural market environment home and abroad, such as further opening of the domestic agricultural market, reduction of farming population, and aging of farmers. The project began with the revision of Farmland Act in July 2005, the contents of which included the function of farmland banking. The Farm Scale Expansion Project, which had been carried out as a separate project from the farmland banking project, is currently managed as part of the banking project.

The Farmland Banking Project is carried out to optimize the scale of farming, promote efficient use of farmland, improve the agricultural structure, and stabilize the farmland market and farmers's income. According to Article 10 of the Law on Korea Rural Community Corporation and Farmland Management Fund, farmland banking project activities are as follows: ① sales, lease, exchange, and separation and merger of farmland; ② supply of information about farmland price and transaction trends; ③ farmland purchase to assist revival of farming; ④ leasing of entrusted farmland; and ⑤ assistance to stabilize the income of retired farmers with farmland as collateral. But the actual activities performed in regard to farmland mobilization are farm-scale expansion, sale and lease of entrusted farmland, and purchase of farmland.

The Farm Scale Expansion Project began in July, 1990 to increase farm scale, promote farmland collectivization, reduce production cost, and increase competitiveness through farmland sale, long-term lease, and exchange of farmland. Since then, it has gone through changes with respect to project goal, eligibility for assistance, loan rate and others. Then in December 2004, a comprehensive program for the rice industry was launched with the goal of creating 70,000 rice farms. Under the program, each farm will have 6 ha of rice field, and the rice farms will take charge of half (420,000 ha) of rice fields in Korea by 2013. But in 1997, when a direct payment was launched to subsidize old retired farmers who transferred their farmland, the implementation of the farm scale expansion project was changed from purchasing of farmland to leasing of farmland.

The farmland lease project is for leasing entrusted farmland to full-time farmers on a long-term basis. The leasable farmland here refers to rice paddies, coarse farmland, orchards and facilities attached to entrusted farmland, all of which are actually used for farming. The lease period is five years, and the rent paid each year is determined between the farmland bank and the lessee. The bank then pays the rent to the lessor after deducting 8-12% from the rent as a commission.

Buying and stockpiling farmland is a key function of the farmland banking project. Farmlands are bought and stockpiled when farmland price is expected to fall due to a rise in the amount of farmland on sale resulting from a sharp drop in the number of farmers, and especially when farmers are expected to suffer a big loss due to a big price fall of prime farmland in agriculture-promoted areas where the demand for farmland for non-agricultural use is low. The farmland banking project aims to stabilize the farmland market, accelerate the improvement of agricultural structure, and preserve farmland, as well as cope flexibly with the demand for farmland for non-agricultural use and foster large-scale agricultural businesses. The farmlands bought under the project are farmlands in agriculture-promoted areas and were previously owned by farmers retiring or leaving the business. The farmlands are leased on a long-term basis under the principle that farmland ownership is maintained and selling it is exercised on a limited basis to stabilize the farmland market. Those persons and entities who are eligible to lease farmland are individuals or companies that intend to work at farming, and the principle that lease period is over five years should be maintained. This project has been in progress since 2010.

4. Future tasks of farmland policy

As the proceeding of agricultural trade liberalization, the agribusiness conditions have worsened. As a result, the amount of idle farmland has been increasing and this trend is expected to continue in the future, too. The total farmland size is also expected to continue decreasing along with the rise in the amount of farmland being converted to other uses. The amount of farmland either owned by non-farmers or leased is also expected to rise due to deregulation of ownership and use of farmland. The situation is that it is necessary to continue making efforts to increase the farm scale per farm as part of the effort to improve competitiveness. And it is expected that leasing farmland will be a more preferred method of increasing the cultivated land per farm over purchasing farmland.

In addition to such circumstantial changes, various pending issues related to the current farmland policy are expected to remain as major tasks that need to be performed in the near future, too. What comes to mind as a primary task concerning the current farmland problem is how to legitimize the disparity between the reality of increasing ownership and use of farmland by non-farmers and the ideal of the land-to-tiller principle stated in the Constitution and the Farmland Act. The perception is spreading that the present farmland system, which allows only farmers to own their farmland, should be rectified to better suit the reality and that it is no longer viable to adhere to the land-to-tiller principle when farmland price is relatively high. There is even an argument that abandoning the land-to-tiller principle and fully authorizing farmland lease is more advantageous to improving the agricultural structure. In this respect, the question as to how to actively utilize farmland banking becomes a major pending issue as it requires a realistic approach to enable relatively competitive professional farmers to secure more farmland in a more stable manner.

The second policy task is to find an effective way how to secure an appropriate amount of farmland needed to supply a base for stable food to the public under the current condition of low food self-sufficiency rate below 30% and with growing idle farmland. On the one hand, there is a need to ease farmland regulations for the efficient use of idle farmland while, on the other hand, there is a need to preserve and manage farmland to build a base for stable food security in preparation for food crisis era. Under such circumstances, voices are raised on the need to reach a social consensus on preserving an optimum amount of farmland and the need to seek ways of managing idle farmland and securing farmland that can be utilized in times of food crisis.

Thirdly, the reality is that about 60% of farmers are aged 60 years or more and that most farms have not yet secured new farmers who can succeed their farming business. In view of the situation, it is necessary to actively seek policies that can improve conditions for retiring and selling farmland and that can help future farmers secure farmland. Allowing non-farmers to buy farmland will enable real estate speculators to obtain farmland and thus encourage speculation and make it difficult for farmers to secure farmland with ease. Possession of farmland for speculative purpose can prevent farmers from acquiring land on lease and make it difficult for them to efficiently and stably use their farmland. Measures should be found to improve the liquidity of farmland and supply farmland to future farmers while avoiding these problems.

Fourthly, change of thinking is needed concerning the policy on farmland price. Under the current circumstances where most farmers want to see farmland price rise and demand that non-farmers be allowed to buy farmland freely, the government policy of preserving farmland and stabilizing farmland price will face many difficulties. Even though farmland price in suburban areas can skyrocket with the deregulation of farmland, farmland price in rural areas will fall because of deterioration of net profit of farming, and this will cause problems in maintaining the asset value of farms and lower the ability to pay back debts. Accordingly, the problem of maintaining farmland price at an appropriate level is expected to emerge as a new policy agenda.

Finally, under the current environment where the multi-functionality of agriculture and rural community is stressed, planned management of rural space and prevention of thoughtless development have become major challenges. Important rural amenity resources are disappearing due to emergence of buildings that do not blend with the landscape, livestock barns that are not in harmony with the plough and sowing of agriculture, and various facilities installed randomly in different locations. As this problem is related with farmland conversion and planned management of space, it is necessary to seek a comprehensive way to manage rural space under the sophisticated plan. For instance, various action plans, such as the adoption of the‘plan before development’ principle, are required to prevent imprudent development and indiscreet use of farmland.

Date submitted: July 27, 2013

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: August 6, 2013