ABSTRACT

This study examines the market trends and policy frameworks surrounding subtropical fruits within the context of climate change. The analysis focuses on key crops including lemons, mangos, figs, bananas, passion fruits, blueberries, pomegranates, dragon fruits, cherries, kiwis, and papayas. It examines factors such as cultivation patterns, regional concentration, import volumes, prices, and production costs. Additionally, the study evaluates policies related to facility installation and energy cost reduction to support subtropical fruit cultivation. The findings reveal that subtropical fruit production is generally expanding, it remains concentrated in southern regions like Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do due to climate limitations. This regional concentration has resulted in gaps in central government support, leaving subtropical fruit growers underrepresented in national policy initiatives. Although local governments in key production areas have introduced some compensatory measures, there is still a significant lack of policies promoting renewable energy installations, which are eseential for reducing heating costs. In the short term, including subtropical fruit farms in the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Program could help address energy-related challenges. However, a broader policy discussion is needed to integrate subtropical fruits into the wider fruit industry alongside traditional crops, ensuring the sector’s sustainable growth.

Keywords: subtropical fruit, market trend, global warming, adaptation to climate change

INTRODUCTION

The Korean Peninsula is undergoing a climatic shift towards subtropical conditions, driven by global warming. According to the widely accepted Trewartha criteria for defining subtropical climates, such regions are characterized by having eight or more months with an average temperature of 10°C or higher. As of 2022, subtropical zones account for 6.3% of Korea's total land area. However, climate projections based on the SSP5-8.5 scenario[1] predict that this will expand dramatically to 55.9% by the 2050s (Rural Development Administration, 2022, Apr 13).

This climate change has opened up new opportunities for Korean farmers with the emergence of subtropical crops as a potential income source, prompting a series of research. Recent studies have primarily focused on the current state of cultivation, analyzing the acreage and number of farms dedicated to various subtropical crops (Kim et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2020). Other studies have concentrated on specific crops, especially mangoes, exploring factors influencing consumer purchase intentions, willingness to pay (Jeong et al., 2014; Jeong, 2021), cultivation feasibility under Korean conditions (Ji et al., 2018), and the technical efficiency of mango farms (Kim et al., 2022). Additionally, local governments have initiated studies to encourage the cultivation of subtropical crops, particularly in the southern regions of Korea, including Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do.

This study aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of subtropical crop cultivation in Korea and to suggest effective policy recommendations for supporting this emerging agricultural sector. Expanding upon previous research, this investigation adopts a nationwide perspective and examines a broader range of subtropical crops. Vegetables among subtropical crops are somewhat similar to those currently grown, as they are often cultivated outdoors or in unheated greenhouses. Therefore, this study focuses on subtropical fruits due to their more distinct cultivation requirements compared to conventional ones such as apples, pears, and peaches. Specifically, 11 items including lemon, mango, fig, banana, passion fruit, blueberry, pomegranate, dragon fruit, cherry, kiwi, and papaya have been chosen for analysis. These fruits were chosen based on their familiarity to domestic consumers and the availability of sufficient data for comprehensive analysis.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the analytical methods and data utilized in this study. Section 3 examines the cultivation status, regional concentration, import volume, prices, and production costs of the selected subtropical fruits, as well as the current policy landscape related to them in Korea. Finally, Section 4 derives implications from these findings and discusses their significance for the future of Korean agriculture in the context of climate change.

METHODOLOGY

To examine the status of subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea, we utilized statistical data published by various government agencies, including the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), the Rural Development Administration (RDA), and the Korea Customs Service. In cases where government data were insufficient or unavailable, we supplemented our analysis with reliable information from the National Agricultural Cooperative Federation (NACF) and findings from national research and development projects. The policy review covered both central and local government initiatives, providing a comprehensive overview of the current policy landscape regarding subtropical fruit cultivation.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

Key trends in Korea’s subtropical fruit market

While there are variations across individual crops, the overall trend in farm numbers suggests that subtropical fruits are generally in a growth phase. By 2022, the total number of farms had reached 48,332, an increase of over 10,000 compared to 2015.[2] Among the crops analyzed, blueberry farms were the most numerous, with 23,625 farms, followed by figs, cherries, pomegranates, and kiwis. The fastest growth rates were observed for bananas, passion fruits, lemons, cherries, papayas, and mangos. However, pomegranates were the only crop to show a decline in the number of farms.

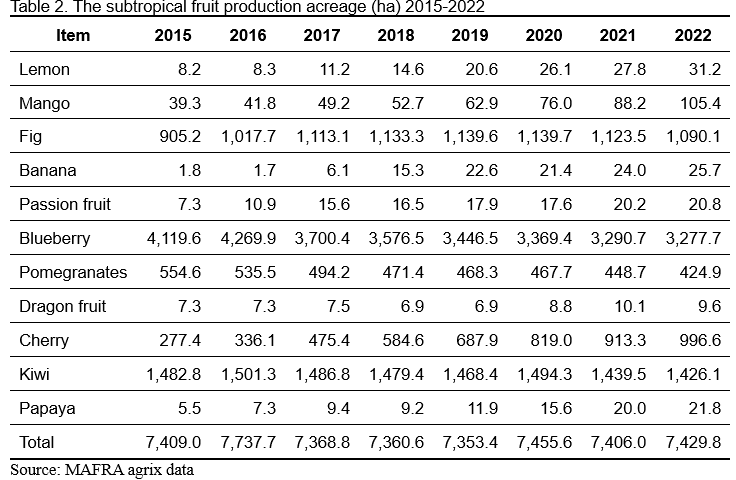

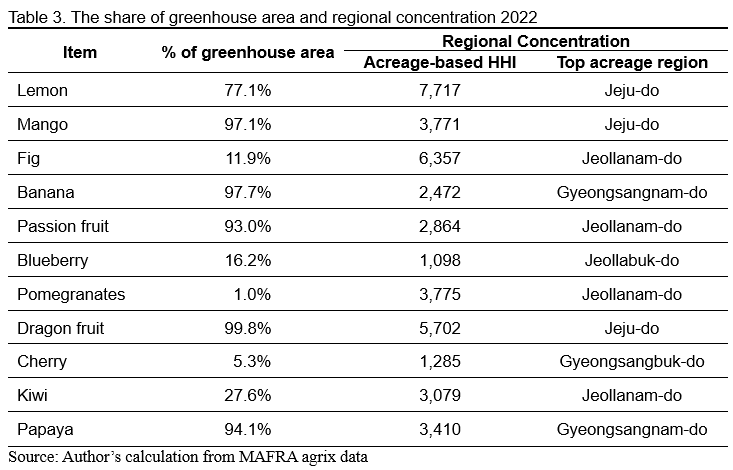

The acreage for subtropical fruits has not changed significantly since 2015, primarily due to a decrease in the acreages of blueberry and kiwi, which previously had large cultivation areas. However, crops such as banana, lemon, papaya, cherry, passion fruit, and mango have shown high rates of increase in cultivated area, and it has been found that they are generally grown in greenhouses. Most of the items have an acreage-based Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)[3] of 1,500 or higher, indicating that subtropical fruits are predominantly grown in the southern regions such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do, where the climate is relatively favorable for cultivation due to higher temperatures.

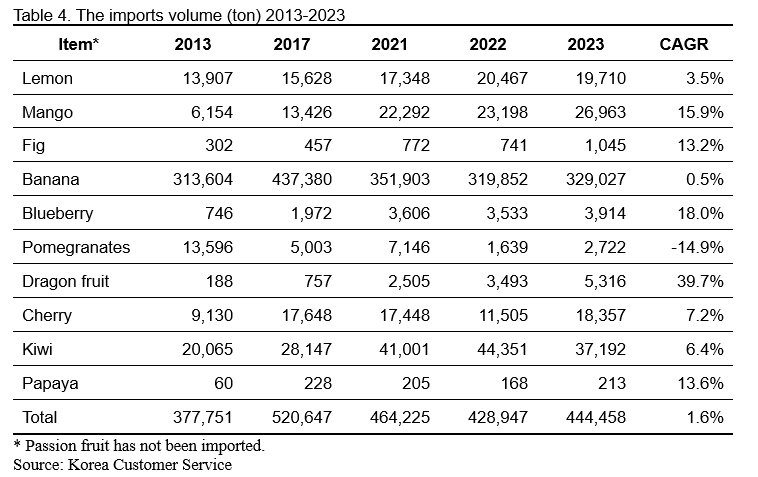

Subtropical fruit imports are on the rise as well. Banana imports are significantly dominant, reaching approximately 330,000 tons in 2023. While this marks a slight increase compared to 2013, it represents a decline of over 100,000 tons from the record high in 2017. This drop seems to be linked to sluggish domestic consumption and supply instability caused by local weather conditions (Nam et al., 2023). While most items showed an increase in imports, pomegranates saw a decline in import volumes.

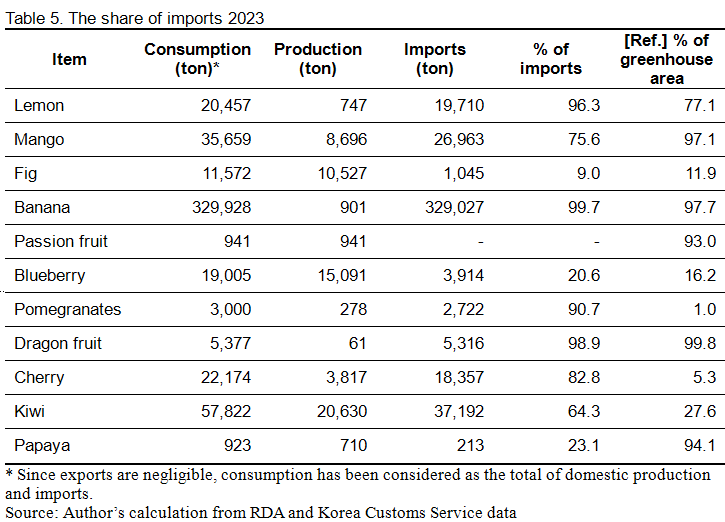

The proportion of imports in domestic consumption varies considerably across different items. For example, imports of figs account for 9.0% of consumption, while for bananas the figure soars to 99.7%. However, for items with domestic consumption exceeding 10,000 tons, those that have a greater share of greenhouse cultivation generally exhibit a higher percentage of imports. This points to the need to either develop varieties suited for open-field cultivation or to address the challenges associated with greenhouse farming to boost the competitiveness of domestically grown subtropical fruits.

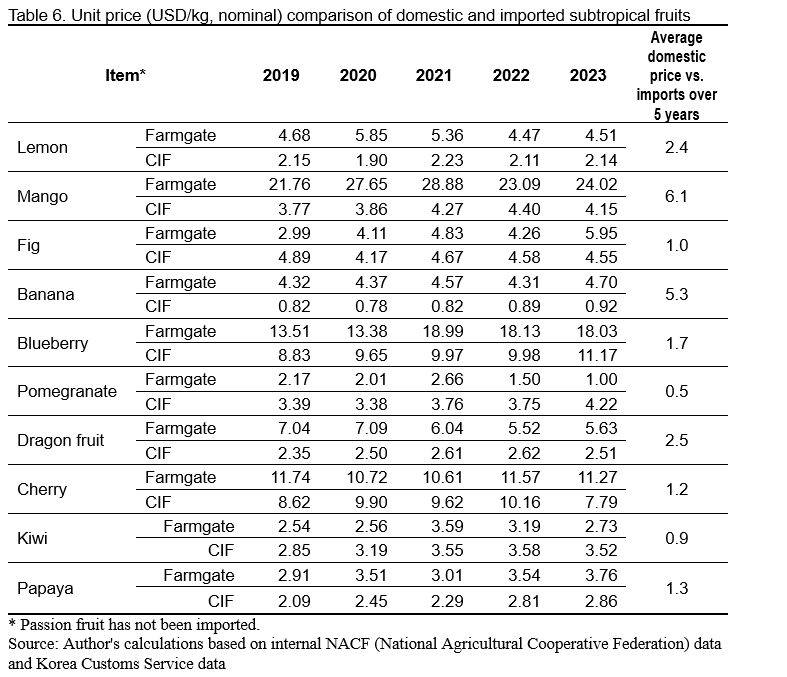

A similar pattern can be observed when comparing the farm-gate prices of domestically produced subtropical fruits with CIF (Cost Insurance Freight) price of imports. In most cases, domestic prices are higher, highlighting a lack of price competitiveness. However, for fruits like pomegranates, figs, and cherries - where greenhouse cultivation is less prevalent - the price difference between domestic and imported products is relatively small.

The market openness for subtropical fruits in Korea is quite high. Tariffs have been eliminated or are scheduled to be eliminated for most analyzed items, except for mangoes from Thailand. Tariff reductions are expected for mangoes and papayas from the Philippines. Korea and the Philippines signed a bilateral FTA in 2023 and are preparing for its implementation. Once this agreement takes effect, tariffs on bananas and papayas from the Philippines will be eliminated within five years. Consequently, the only import subject to tariffs are limited to Thai mangoes.

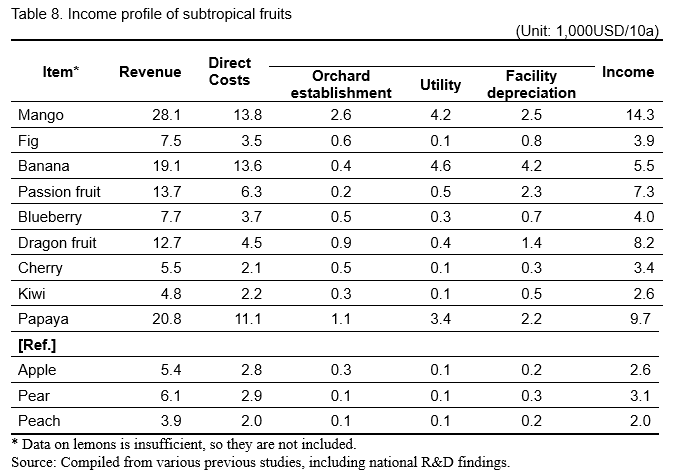

The income per unit area for subtropical fruits tended to be higher than that of traditional fruits like apples, pears, and peaches. However, the direct costs—especially for orchard establishment, utilities, and facility depreciation—were also generally higher compared to these conventional fruits. When looking at the cost structure of subtropical fruit production, it becomes evident that greenhouse farming drives up costs significantly. These fruits require higher per-unit-area expenses for orchard establishment, utility bills, and depreciation of farming facilities. For apples, pears, and peaches, these three cost categories account for around 20.1% of total direct costs, but for subtropical fruits, the average rises to 51.7%. Orchard establishment and facility depreciation are tied to the costs of greenhouse installation, while utility costs are primarily related to heating. To encourage the production of subtropical fruits, there’s a clear need for support measures aimed at reducing these financial pressures.

Policy overview for subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea

Earlier, it was emphasized that reducing the costs associated with greenhouse installation and heating is crucial for supporting subtropical fruit production. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on examining policies related to greenhouse installation and heating. The review revealed that subtropical fruit farmers encounter difficulties in accessing central government support for these aspects.

Generally, for greenhouse installation, central government initiatives such as the Facility Modernization Project and the Smart Farm Expansion Project are available. The Facility Modernization Project supports facilities for high-quality production and disaster prevention, including multi-layer insulating curtains and unmanned pest control aircraft. This project comprises 50% grant funding, 30% interest subsidies, and 20% self-financing. Similarly, the Smart Farm Expansion Project provides support for the installation of ICT facilities and equipment, also structured with 50% grant funding, 30% interest subsidies, and 20% self-financing. Both initiatives are financed by the Free Trade Agreement Implementation Fund, which is designed to assist crops anticipated to be adversely affected by FTAs. Since subtropical fruits were only recently introduced to Korea and do not face significant impacts from FTAs, they are excluded from these programs.

In terms of greenhouse heating costs, the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project provides support for the installation of renewable energy systems. However, this project does not include orchard farms, regardless of the type of fruit, which means subtropical fruit farmers are also ineligible for this support. In short, subtropical fruit farmers find it difficult to access any support from central government policies. This lack of national-level policy support likely stems from the fact that subtropical fruit cultivation is still largely concentrated in southern regions.

To address this gap in central government support, some local governments in regions with significant subtropical fruit production—such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do—have implemented their own policies. Jeollanam-do, in particular, described the intention behind related policies as "support for facility-based fruit cultivation that is excluded from national funding programs." However, while these regions have developed measures that complement the central government's Facility Modernization Project, there are currently no local policies in place to address the lack of support for heating costs, especially in relation to the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Subtropical fruit production is currently on the rise but is mainly concentrated in the southern regions, such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do, due to climate limitations. This regional focus has created gaps in support from the central government, resulting in subtropical fruit growers being largely overlooked by national policy initiatives.

The promotion of subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea presents both opportunities and challenges. As the viability of traditional crops like apples, pears, and peaches gradually declines, there is an increasing need to develop subtropical fruits as a forward-looking strategy. However, since Korea hasn't fully transitioned to a subtropical climate, cultivating these crops will likely require the use of greenhouses and additional heating. This brings with it significant costs, and the associated greenhouse gas emissions could worsen climate change, making it less attractive to aggressively promote subtropical fruit farming.

To address these concerns, it is essential to encourage the use of renewable energy to reduce heating costs and lower greenhouse gas emissions. However, as mentioned earlier, the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Program, which supports the installation of renewable energy facilities, currently excludes fruit farms from eligibility. In the short term, a potential solution could be to include fruit farms in the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project.

Moving forward, it is crucial to explore support measures for the period before profits are generated following orchard establishment. Generally, it takes about 3 to 4 years for fruit trees to yield stable income after planting. This timeline is equally applicable to subtropical fruits, particularly, the financial strain during the non-revenue phase is exacerbated by the costs associated with facility installation. Implementing support programs to alleviate this burden could play a significant role in enhancing the competitiveness of subtropical fruits.

Finally, broader efforts will be needed to expand the scope of Korea's fruit industry. Traditionally, the industry has focused on six key crops—apples, pears, peaches, grapes, citrus, and persimmons. However, with climate change likely to expand the areas suitable for subtropical fruit cultivation, it will be important to integrate subtropical fruits into the country’s fruit industry and position them as a key driver of future agricultural growth.

This study does not examine the distribution processes, including marketing channels for subtropical fruits, due to limitations in data collection. Initially, sales primarily occurred through direct transactions between farmers and consumers; however, distribution has recently expanded to encompass major retail chains and live commerce platforms. Nonetheless, the absence of adequate quantitative data has hindered a comprehensive analysis of this topic, leading to its exclusion from this research. Future studies are anticipated to investigate this significant aspect further.

REFERENCES

Gyeongnam Institute. 2023. A Fundamental Study on Establishing Subtropical Complexes for Climate Change Adaptation, Gyeongnam Institute.

Gyeongnam Institute. 2023. A Fundamental Study on promoting Subtropical Agriculture in Gyeongnam, Gyeongnam Institute.

Gyeongsangbuk-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2023. A Study on Setting Criteria for Location of the East Coast Subtropical Crop Research Institute, Gyeongsangbuk-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services

Gyeongsangnam-do Council. 2023. Strategies and Support Measures for Fostering Subtropical Crops in Gyeongnam, Gyeongsangnam-do Council

Jeollanam-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2021. Analysis of Farm Management Performance in Introducing Subtropical Crops for Climate Change Adaptation, Rural Development Administration

Jeollanam-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2021. Development of Production-Consumption Infrastructure for Subtropical Complex Establishment, Rural Development Administration

Jeong, H. K., Kim, C. G., and Lee, M. S. 2014. Identifying Factors Affecting Consumer’s Choice to Domestic Mango, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy 41(2), 271-292

Jeong, J. 2021. Mango and Banana Consumption Trend, and Estimation of Domestic Product’s WTP [Conference presentation], Korea Food Marketing Association 2021 Convention, 167-176

Jeong, U. S., Kim, S., and Chae, Y. W. 2020. Analysis on the Cultivation Trends and Main Producing Areas of Subtropical Crops in Korea, Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 21(12), 524-535

Ji, S., T., Youm, J. W., and Yoo, J. Y. 2018. A Feasibility Study on the Cultivation of Tropical Fruit in Korea: Focused on Mango, Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 19(6), 252-263

Kim, C. Y., Kim, Y. H., Han, S. H., and Ko, H. C. 2019. Current Situations and Prospects on the Cultivation Program of Tropical and Subtropical Crops in Korea, Korean Journal of Plant Resources 32(1), 45-52

Kim, J., You, H., Ma, E., and Jeong W. 2022. An Analysis on Technical Efficiency of Mango Farms, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy 49(1), 89-111

Nam, K., Chae, S., Choi, M., and Kim, K. 2023. A Study on Agricultural and Agri-livestock Trade Trends in the Philippines, Korea Rural Economic Institute

Rural Development Administration. 2016. 2016 Management Insights for Niche Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2017, Aug 31. Exploring New Food opportunities with Subtropical Crops, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2017. 2017 Management Insights for Niche Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022, Apr 13. Global Warming Will Alter Future Fruit Cultivation Contours, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022, Feb 14. Use Heating Cost Maps to Identify Subtropical Fruit Growing Areas, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022. Strategies for Responding to Consumer Needs in the Agricultural Market, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2022 Agricultural Production Cost Survey, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2022 State-Level Agricultural Production Cost Survey, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2023 Survey on the Current Status of Subtropical Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

[1] Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are climate scenarios presented in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. These scenarios are categorized into five pathways based on the radiative forcing intensity in 2100 and anticipated socioeconomic changes. Among them, the SSP5-8.5 scenario assumes high use of fossil fuels and indiscriminate development centered on cities, with a focus on rapid industrial technological advancements.

[2] In Korea, it’s common for farms to grow multiple crops simultaneously. This means that a single farm may cultivate two or more types of subtropical fruits, which suggests that the number of subtropical fruit farms might be and overestimation.

[3] The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a widely used measure of market concentration, calculated by summing the squares of each firm's market share and multiplying the total by 10,000. In this study, the HHI is applied to assess the concentration of cultivation areas, so it was determined by summing the squares of each region's share of the total cultivation area and multiplying the result by 10,000. The U.S. Department of Justice considers markets in which the HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800 points to be moderately concentrated, and considers markets in which the HHI is in excess of 1,800 points to be highly concentrated.

Subtropical Fruit Cultivation in Korea: Current Trends and Policy Issues

ABSTRACT

This study examines the market trends and policy frameworks surrounding subtropical fruits within the context of climate change. The analysis focuses on key crops including lemons, mangos, figs, bananas, passion fruits, blueberries, pomegranates, dragon fruits, cherries, kiwis, and papayas. It examines factors such as cultivation patterns, regional concentration, import volumes, prices, and production costs. Additionally, the study evaluates policies related to facility installation and energy cost reduction to support subtropical fruit cultivation. The findings reveal that subtropical fruit production is generally expanding, it remains concentrated in southern regions like Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do due to climate limitations. This regional concentration has resulted in gaps in central government support, leaving subtropical fruit growers underrepresented in national policy initiatives. Although local governments in key production areas have introduced some compensatory measures, there is still a significant lack of policies promoting renewable energy installations, which are eseential for reducing heating costs. In the short term, including subtropical fruit farms in the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Program could help address energy-related challenges. However, a broader policy discussion is needed to integrate subtropical fruits into the wider fruit industry alongside traditional crops, ensuring the sector’s sustainable growth.

Keywords: subtropical fruit, market trend, global warming, adaptation to climate change

INTRODUCTION

The Korean Peninsula is undergoing a climatic shift towards subtropical conditions, driven by global warming. According to the widely accepted Trewartha criteria for defining subtropical climates, such regions are characterized by having eight or more months with an average temperature of 10°C or higher. As of 2022, subtropical zones account for 6.3% of Korea's total land area. However, climate projections based on the SSP5-8.5 scenario[1] predict that this will expand dramatically to 55.9% by the 2050s (Rural Development Administration, 2022, Apr 13).

This climate change has opened up new opportunities for Korean farmers with the emergence of subtropical crops as a potential income source, prompting a series of research. Recent studies have primarily focused on the current state of cultivation, analyzing the acreage and number of farms dedicated to various subtropical crops (Kim et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2020). Other studies have concentrated on specific crops, especially mangoes, exploring factors influencing consumer purchase intentions, willingness to pay (Jeong et al., 2014; Jeong, 2021), cultivation feasibility under Korean conditions (Ji et al., 2018), and the technical efficiency of mango farms (Kim et al., 2022). Additionally, local governments have initiated studies to encourage the cultivation of subtropical crops, particularly in the southern regions of Korea, including Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do.

This study aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of subtropical crop cultivation in Korea and to suggest effective policy recommendations for supporting this emerging agricultural sector. Expanding upon previous research, this investigation adopts a nationwide perspective and examines a broader range of subtropical crops. Vegetables among subtropical crops are somewhat similar to those currently grown, as they are often cultivated outdoors or in unheated greenhouses. Therefore, this study focuses on subtropical fruits due to their more distinct cultivation requirements compared to conventional ones such as apples, pears, and peaches. Specifically, 11 items including lemon, mango, fig, banana, passion fruit, blueberry, pomegranate, dragon fruit, cherry, kiwi, and papaya have been chosen for analysis. These fruits were chosen based on their familiarity to domestic consumers and the availability of sufficient data for comprehensive analysis.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses the analytical methods and data utilized in this study. Section 3 examines the cultivation status, regional concentration, import volume, prices, and production costs of the selected subtropical fruits, as well as the current policy landscape related to them in Korea. Finally, Section 4 derives implications from these findings and discusses their significance for the future of Korean agriculture in the context of climate change.

METHODOLOGY

To examine the status of subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea, we utilized statistical data published by various government agencies, including the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA), the Rural Development Administration (RDA), and the Korea Customs Service. In cases where government data were insufficient or unavailable, we supplemented our analysis with reliable information from the National Agricultural Cooperative Federation (NACF) and findings from national research and development projects. The policy review covered both central and local government initiatives, providing a comprehensive overview of the current policy landscape regarding subtropical fruit cultivation.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

Key trends in Korea’s subtropical fruit market

While there are variations across individual crops, the overall trend in farm numbers suggests that subtropical fruits are generally in a growth phase. By 2022, the total number of farms had reached 48,332, an increase of over 10,000 compared to 2015.[2] Among the crops analyzed, blueberry farms were the most numerous, with 23,625 farms, followed by figs, cherries, pomegranates, and kiwis. The fastest growth rates were observed for bananas, passion fruits, lemons, cherries, papayas, and mangos. However, pomegranates were the only crop to show a decline in the number of farms.

The acreage for subtropical fruits has not changed significantly since 2015, primarily due to a decrease in the acreages of blueberry and kiwi, which previously had large cultivation areas. However, crops such as banana, lemon, papaya, cherry, passion fruit, and mango have shown high rates of increase in cultivated area, and it has been found that they are generally grown in greenhouses. Most of the items have an acreage-based Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)[3] of 1,500 or higher, indicating that subtropical fruits are predominantly grown in the southern regions such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do, where the climate is relatively favorable for cultivation due to higher temperatures.

Subtropical fruit imports are on the rise as well. Banana imports are significantly dominant, reaching approximately 330,000 tons in 2023. While this marks a slight increase compared to 2013, it represents a decline of over 100,000 tons from the record high in 2017. This drop seems to be linked to sluggish domestic consumption and supply instability caused by local weather conditions (Nam et al., 2023). While most items showed an increase in imports, pomegranates saw a decline in import volumes.

The proportion of imports in domestic consumption varies considerably across different items. For example, imports of figs account for 9.0% of consumption, while for bananas the figure soars to 99.7%. However, for items with domestic consumption exceeding 10,000 tons, those that have a greater share of greenhouse cultivation generally exhibit a higher percentage of imports. This points to the need to either develop varieties suited for open-field cultivation or to address the challenges associated with greenhouse farming to boost the competitiveness of domestically grown subtropical fruits.

A similar pattern can be observed when comparing the farm-gate prices of domestically produced subtropical fruits with CIF (Cost Insurance Freight) price of imports. In most cases, domestic prices are higher, highlighting a lack of price competitiveness. However, for fruits like pomegranates, figs, and cherries - where greenhouse cultivation is less prevalent - the price difference between domestic and imported products is relatively small.

The market openness for subtropical fruits in Korea is quite high. Tariffs have been eliminated or are scheduled to be eliminated for most analyzed items, except for mangoes from Thailand. Tariff reductions are expected for mangoes and papayas from the Philippines. Korea and the Philippines signed a bilateral FTA in 2023 and are preparing for its implementation. Once this agreement takes effect, tariffs on bananas and papayas from the Philippines will be eliminated within five years. Consequently, the only import subject to tariffs are limited to Thai mangoes.

The income per unit area for subtropical fruits tended to be higher than that of traditional fruits like apples, pears, and peaches. However, the direct costs—especially for orchard establishment, utilities, and facility depreciation—were also generally higher compared to these conventional fruits. When looking at the cost structure of subtropical fruit production, it becomes evident that greenhouse farming drives up costs significantly. These fruits require higher per-unit-area expenses for orchard establishment, utility bills, and depreciation of farming facilities. For apples, pears, and peaches, these three cost categories account for around 20.1% of total direct costs, but for subtropical fruits, the average rises to 51.7%. Orchard establishment and facility depreciation are tied to the costs of greenhouse installation, while utility costs are primarily related to heating. To encourage the production of subtropical fruits, there’s a clear need for support measures aimed at reducing these financial pressures.

Policy overview for subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea

Earlier, it was emphasized that reducing the costs associated with greenhouse installation and heating is crucial for supporting subtropical fruit production. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on examining policies related to greenhouse installation and heating. The review revealed that subtropical fruit farmers encounter difficulties in accessing central government support for these aspects.

Generally, for greenhouse installation, central government initiatives such as the Facility Modernization Project and the Smart Farm Expansion Project are available. The Facility Modernization Project supports facilities for high-quality production and disaster prevention, including multi-layer insulating curtains and unmanned pest control aircraft. This project comprises 50% grant funding, 30% interest subsidies, and 20% self-financing. Similarly, the Smart Farm Expansion Project provides support for the installation of ICT facilities and equipment, also structured with 50% grant funding, 30% interest subsidies, and 20% self-financing. Both initiatives are financed by the Free Trade Agreement Implementation Fund, which is designed to assist crops anticipated to be adversely affected by FTAs. Since subtropical fruits were only recently introduced to Korea and do not face significant impacts from FTAs, they are excluded from these programs.

In terms of greenhouse heating costs, the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project provides support for the installation of renewable energy systems. However, this project does not include orchard farms, regardless of the type of fruit, which means subtropical fruit farmers are also ineligible for this support. In short, subtropical fruit farmers find it difficult to access any support from central government policies. This lack of national-level policy support likely stems from the fact that subtropical fruit cultivation is still largely concentrated in southern regions.

To address this gap in central government support, some local governments in regions with significant subtropical fruit production—such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do—have implemented their own policies. Jeollanam-do, in particular, described the intention behind related policies as "support for facility-based fruit cultivation that is excluded from national funding programs." However, while these regions have developed measures that complement the central government's Facility Modernization Project, there are currently no local policies in place to address the lack of support for heating costs, especially in relation to the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Subtropical fruit production is currently on the rise but is mainly concentrated in the southern regions, such as Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do, due to climate limitations. This regional focus has created gaps in support from the central government, resulting in subtropical fruit growers being largely overlooked by national policy initiatives.

The promotion of subtropical fruit cultivation in Korea presents both opportunities and challenges. As the viability of traditional crops like apples, pears, and peaches gradually declines, there is an increasing need to develop subtropical fruits as a forward-looking strategy. However, since Korea hasn't fully transitioned to a subtropical climate, cultivating these crops will likely require the use of greenhouses and additional heating. This brings with it significant costs, and the associated greenhouse gas emissions could worsen climate change, making it less attractive to aggressively promote subtropical fruit farming.

To address these concerns, it is essential to encourage the use of renewable energy to reduce heating costs and lower greenhouse gas emissions. However, as mentioned earlier, the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Program, which supports the installation of renewable energy facilities, currently excludes fruit farms from eligibility. In the short term, a potential solution could be to include fruit farms in the Agricultural Energy Efficiency Project.

Moving forward, it is crucial to explore support measures for the period before profits are generated following orchard establishment. Generally, it takes about 3 to 4 years for fruit trees to yield stable income after planting. This timeline is equally applicable to subtropical fruits, particularly, the financial strain during the non-revenue phase is exacerbated by the costs associated with facility installation. Implementing support programs to alleviate this burden could play a significant role in enhancing the competitiveness of subtropical fruits.

Finally, broader efforts will be needed to expand the scope of Korea's fruit industry. Traditionally, the industry has focused on six key crops—apples, pears, peaches, grapes, citrus, and persimmons. However, with climate change likely to expand the areas suitable for subtropical fruit cultivation, it will be important to integrate subtropical fruits into the country’s fruit industry and position them as a key driver of future agricultural growth.

This study does not examine the distribution processes, including marketing channels for subtropical fruits, due to limitations in data collection. Initially, sales primarily occurred through direct transactions between farmers and consumers; however, distribution has recently expanded to encompass major retail chains and live commerce platforms. Nonetheless, the absence of adequate quantitative data has hindered a comprehensive analysis of this topic, leading to its exclusion from this research. Future studies are anticipated to investigate this significant aspect further.

REFERENCES

Gyeongnam Institute. 2023. A Fundamental Study on Establishing Subtropical Complexes for Climate Change Adaptation, Gyeongnam Institute.

Gyeongnam Institute. 2023. A Fundamental Study on promoting Subtropical Agriculture in Gyeongnam, Gyeongnam Institute.

Gyeongsangbuk-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2023. A Study on Setting Criteria for Location of the East Coast Subtropical Crop Research Institute, Gyeongsangbuk-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services

Gyeongsangnam-do Council. 2023. Strategies and Support Measures for Fostering Subtropical Crops in Gyeongnam, Gyeongsangnam-do Council

Jeollanam-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2021. Analysis of Farm Management Performance in Introducing Subtropical Crops for Climate Change Adaptation, Rural Development Administration

Jeollanam-do Agricultural Research & Extention Services. 2021. Development of Production-Consumption Infrastructure for Subtropical Complex Establishment, Rural Development Administration

Jeong, H. K., Kim, C. G., and Lee, M. S. 2014. Identifying Factors Affecting Consumer’s Choice to Domestic Mango, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy 41(2), 271-292

Jeong, J. 2021. Mango and Banana Consumption Trend, and Estimation of Domestic Product’s WTP [Conference presentation], Korea Food Marketing Association 2021 Convention, 167-176

Jeong, U. S., Kim, S., and Chae, Y. W. 2020. Analysis on the Cultivation Trends and Main Producing Areas of Subtropical Crops in Korea, Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 21(12), 524-535

Ji, S., T., Youm, J. W., and Yoo, J. Y. 2018. A Feasibility Study on the Cultivation of Tropical Fruit in Korea: Focused on Mango, Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 19(6), 252-263

Kim, C. Y., Kim, Y. H., Han, S. H., and Ko, H. C. 2019. Current Situations and Prospects on the Cultivation Program of Tropical and Subtropical Crops in Korea, Korean Journal of Plant Resources 32(1), 45-52

Kim, J., You, H., Ma, E., and Jeong W. 2022. An Analysis on Technical Efficiency of Mango Farms, Korean Journal of Agricultural Management and Policy 49(1), 89-111

Nam, K., Chae, S., Choi, M., and Kim, K. 2023. A Study on Agricultural and Agri-livestock Trade Trends in the Philippines, Korea Rural Economic Institute

Rural Development Administration. 2016. 2016 Management Insights for Niche Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2017, Aug 31. Exploring New Food opportunities with Subtropical Crops, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2017. 2017 Management Insights for Niche Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022, Apr 13. Global Warming Will Alter Future Fruit Cultivation Contours, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022, Feb 14. Use Heating Cost Maps to Identify Subtropical Fruit Growing Areas, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2022. Strategies for Responding to Consumer Needs in the Agricultural Market, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2022 Agricultural Production Cost Survey, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2022 State-Level Agricultural Production Cost Survey, Rural Development Administration

Rural Development Administration. 2023. 2023 Survey on the Current Status of Subtropical Crop Cultivation, Rural Development Administration

[1] Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are climate scenarios presented in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. These scenarios are categorized into five pathways based on the radiative forcing intensity in 2100 and anticipated socioeconomic changes. Among them, the SSP5-8.5 scenario assumes high use of fossil fuels and indiscriminate development centered on cities, with a focus on rapid industrial technological advancements.

[2] In Korea, it’s common for farms to grow multiple crops simultaneously. This means that a single farm may cultivate two or more types of subtropical fruits, which suggests that the number of subtropical fruit farms might be and overestimation.

[3] The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a widely used measure of market concentration, calculated by summing the squares of each firm's market share and multiplying the total by 10,000. In this study, the HHI is applied to assess the concentration of cultivation areas, so it was determined by summing the squares of each region's share of the total cultivation area and multiplying the result by 10,000. The U.S. Department of Justice considers markets in which the HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800 points to be moderately concentrated, and considers markets in which the HHI is in excess of 1,800 points to be highly concentrated.