ABSTRACT

Social inequality, particularly in reference to gender, has already been recognized across the world as a pivotal issue in development. Gender gap is predominantly evident in sectors such as agriculture in which productivity depends on one’s access and control over agricultural inputs and resources. These inequalities and inequities are further exacerbated by the rapid changes in global climatic systems. Evidences show that there is disparity on the impacts of climate change among sectors, therefore, it is necessary to integrate gender considerations into the development of agricultural plans, projects, and programs. This paper gives insights on how to increase the adaptive capacity of farming communities in the Philippines to effectively address the impacts of climate change. Specific strategies on how to build more climate-resilient and gender-responsive agricultural communities are discussed such as provision of women-friendly equipment, machineries, and facilities, conduct of capacity building and gender-awareness campaigns, and development of localized Gender Action Plans.

Keywords: gender, agriculture, climate change, climate resilient agriculture

GENDER INCLUSION IN CLIMATE ACTION

In the recent years, efforts to achieve gender equality in the Philippines has been progressing, with the legislation of various laws, most notably, the Magna Carta of Women in 2009, and the Philippine Plan for Gender and Development 1995-2025. However, according to Bayudan-Dacuycuy (2018), challenges still persist particularly in the agriculture sector where women’s income remains to be just half of male agriculture workers. One of the reasons is that women are more likely to be involved in weeding and harvesting jobs, which are known to be less profitable than men’s traditional jobs in agriculture, such as plowing and land preparation (Ani and Casasola, 2020). Moreover, aside from women’s productive role in the society, their reproductive roles – caring for children and doing unpaid household work, make them perform multiple roles. According to the Philippine Commission on Women (PCW, 2021), these multiple roles make women under particular pressure, making their working days longer, rest hours shorter, and stress level higher.

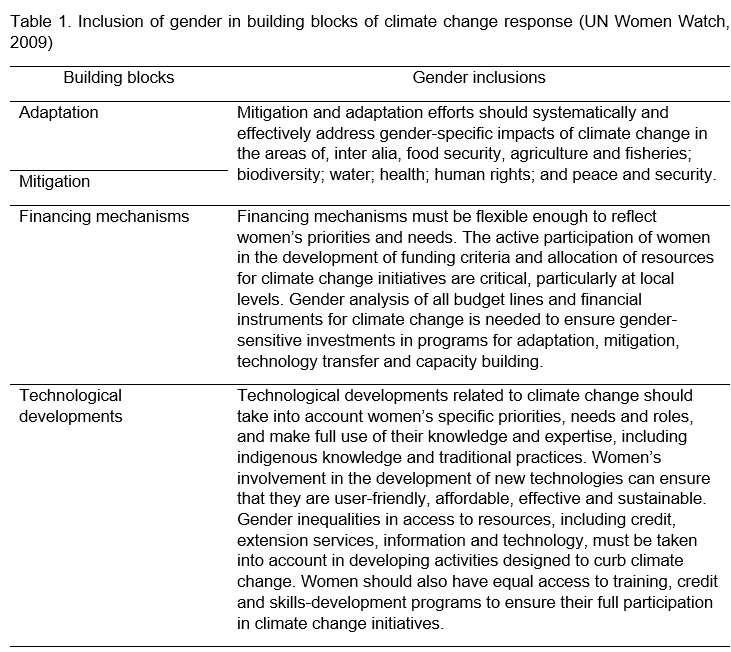

These issues that women experience until today pose more conflicts given the persistent threats of climate change. In many contexts, women are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as compared to men, because they constitute the majority of the world’s poor and are more dependent on natural resources which are threatened by the changing environmental conditions. According to the United Nations Women Watch (2009), incorporating gender perspectives and involving women as agents of change is crucial to help the sector adapt to climate risks and vulnerabilities. Table 1 shows the four critical building blocks in response to climate change identified by the UN Women Watch.

Further, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2016) said that the vulnerabilities of sectors such as women, the elderly, immigrants, and indigenous groups are largely affected by the gender differentiated power, roles, and responsibilities at the household and community levels. According to UNDP (2016), 80% of people displaced by climate change are women and that they do not have easy and adequate access to funds to cover weather-related losses or adaptation technologies. They also face discrimination in accessing land, financial services, social capital, and technology. Another study by Lambrou and Nelson (2010) in agricultural areas in India showed how men and women farmers perceived and experienced climate variabilities, and how these affect their decision-making processes related to food security. The evidence presented in the study showed that due to gender roles (the behaviors, tasks and responsibilities a society defines as “male” or “female”) and the differential gendered access to resources, men and women experience climate variability differently and they have developed diverse coping strategies. The results reveal that coping mechanisms against climate variability, food security, and the overall well-being are significantly dictated by gender differences.

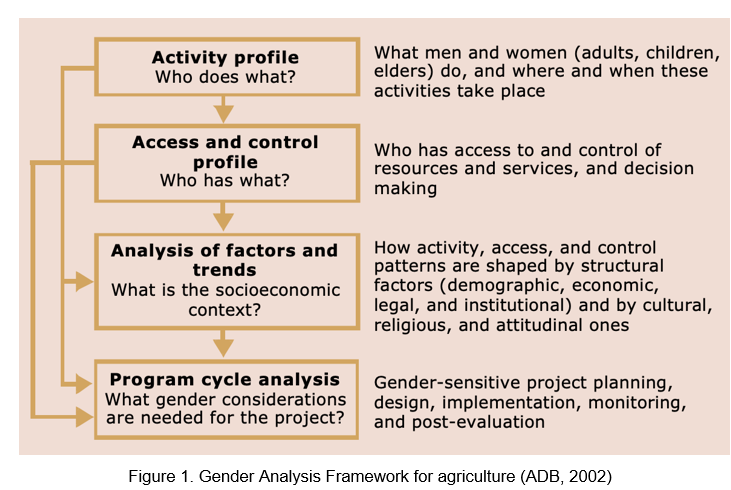

This shows that it is important to incorporate gender perspectives into policies, action plans, and other measures on sustainable development, and climate change adaptation and mitigation plans. To achieve this, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive gender analysis in order to identify specific gender-related gaps and constraints. The Harvard Analytical Framework is one the most commonly used frameworks for gender analysis because it can be easily adapted for use in agricultural production systems (Ludgate, 2016). It also helps to document the differences in the gendered access and control of resources, such as land, water, seeds, or extension information. The Gender Analysis Framework (GAF) for agriculture of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) follows the Harvard Analytical Framework as shown in Figure 1.

The Activity Profile identifies the gender divisions of labor in the community that are grouped into three types – productive activities, reproductive activities, and community involvement. On the other hand, the Access and Control Profile lists the resources needed to carry out tasks and benefits derived from them; access and control are disaggregated by gender. Lastly, the Influencing Factors Profile outlines the socio-economic contexts shaped by demographic, economic, legal, institution, cultural, religious, and behavioral structures affecting both the activity and the access and control profiles in the community.

CASE STUDY IN THE BICOL REGION

The Adaptation and Mitigation Initiative in Agriculture (AMIA) is the flagship program of the Department of Agriculture (DA) to address the impacts of climate change. Through the program, AMIA Villages are built across the country to promote Climate Resilient Agriculture and help farmers and fisherfolks in developing sustainable climate risk-based enterprises. To date, there are already 181 AMIA villages established across 59 provinces in the Philippines where climate-relevant support services are being introduced and implemented to address various climate change-related impacts. The AMIA program has already gained substantial milestones in building these communities to be climate-resilient, however, integration of gender considerations into agricultural planning remains to be one of the main challenges hindering sustainability and full adoption of projects and programs being deployed in AMIA Villages. While gender has already been recognized as an important aspect in agricultural planning, operationalization and implementation is not yet being fully practiced because of lack of resources and capacities for gender integration.

Hence, a gender-focused project was implemented by the DA Regional Field Office 5 (RFO 5) and the University of the Philippines Los Baños Foundation Inc. (UPLBFI) to demonstrate how gender can be integrated in the development of projects for AMIA Villages in the region. To gather necessary gender-related data, a total of 239 farmers were surveyed in six project sites across the Bicol region. Gender Analysis was conducted using the Harvard Analysis Framework. Assessment of the results showed that across the six sites, women are performing multiple roles as compared to men who are focused generally on managing and doing farm-related activities. While women are not hindered to participate in managing their farms (particularly rice farms) –land preparation, plowing, planting, harvesting, etc., women farmers are normally involved in managing the household - taking care of children and the elderly, preparing meals, and doing other household chores. Moreover, most of the women are also involved and in-charged in livestock and poultry raising, as well as vegetable farming, and management of the associations’ enterprises such as their Agri-Store. Women still take on very traditional gender roles but results of the study showed that both women and men farmers participate in livelihood activities and decide together on some key issues and tasks (e.g. household finances). However, looking at the access and control profiles, men still decide on land use that appears to be a main barrier for women’s access to income-generating activities as farming is the main source of income in the project sites.

Moreover, it was seen that in terms of adaptation strategies, men prefer infrastructure-related interventions which can improve conduct of farming activities. On the other hand, women respondents said that additional businesses and livelihoods can provide them additional sources of income that can be used for adaptation. Generally, all of the farmer beneficiaries believe that trainings and capacity building activities will help them better adapt to climate change impacts.

The study showed that in designing and developing projects, programs, and other support services, it is crucial to make use of the information gathered through the Gender Analysis. Services to be given to the beneficiaries must be tailor-fitted to their specific needs and requirements to ensure buy-in and sustainability. For instance, rabbit meat production is relatively an ‘unfamiliar’ practice in the country as rabbits are generally considered as pets. However, in Capalonga, Camarines Norte, the AMIA farmer beneficiaries have already started raising rabbits, with the support of its Local Government Unit (LGU) for meat production. Men farmers are mostly engaged in rabbit raising, thus, they have control over the income generated through this activity. As women are seen to be effective marketers, they were engaged to participate in the training for processing, packaging, and marketing of rabbit meat to further boost this as a livelihood and complement men farmers in promoting the rabbit meat industry in their community. In this case, and consistent with Paez (2020), it is shown that it is important to target value chains of products that are within the domain of women to ensure that they are more likely to receive and have control on payment for their work.

ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS THROUGH A GENDER PERSPECTIVE

Agriculture in the Philippines is still highly dominated by men. In the latest survey made by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) in 2016, women have only occupied 26% of the total agricultural employment since 2011 (Bayudan-Dacuycuy, 2018). According to Zwarteveen (2014), gender issues in agriculture result from ineffectiveness and inadequacy of technologies and institutional choices, and the differential impacts of development strategies on women and men. The disadvantages faced by women in agriculture in terms of access and control of land, water, and other related resources are reasons why policies, design, operation and management of agriculture systems should pay attention to gender concerns.

Social inequalities and inequities are further exacerbated by the rapid changes in global climatic systems. Evidences show that there is disparity on the impacts of climate change among sectors, therefore, it is important to develop plans and programs through a participatory, gender-responsive approach. To further promote gender integration at the local level, it is important to capacitate both planners and beneficiaries, and increase gender awareness and sensitivity among all stakeholders. Specifically, it is recommended to:

- Strengthen the collection, organization, and use of sex- and gender-disaggregated data to promote effective disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM)Sex- and gender-disaggregated databases are essential to measure differences in various social and economic dimensions and are one of the requirements to obtain gender statistics. These will help identify the most appropriate interventions given the existing conditions of the beneficiaries and be basis and indicator of quantitative or qualitative changes that may occur due to the intervention deployed. Aside from climate change adaptation, these data will also provide substantial inputs to determining appropriate strategies for DRRM. The use of DRRM frameworks with gender lens will help making vulnerable groups be more disaster-responsive and ready.

- Provide sustainable support services and technologies to unburden women of their multiple roles in their respective community.Reproductive works including household chores and home-care are the domains of women. Since these tasks are generally unpaid, providing them with support to save more time that can be utilized for more productive activities is highly recommended.

- Provide women-friendly agricultural equipment and machineries, as well as water-sourcing facilities that will help women farmers minimize hard labor while increasing productivity and income. One of the main constraints that hinder women to be more productive in agriculture is that existing machineries are not very much suitable for them. Thus, provision of lightweight, portable, and ergonomic farm tools and equipment are recommended to empower more women in their farming activities. Moreover, sources of water should also be made more accessible. According to the Country Gender Assessment (CGA) of FAO in 2022, only 36% of women farmers in the Philippines have access to irrigation. As water is vital in agricultural production, policies, design, operation and management of irrigation systems should pay attention to gender concerns.

- Support women farmers in improving communication and marketing channels and strategies. Women farmers are generally pro-active in the development of products out of the existing resources in their respective community. However, financial literacy and digital skills are still lacking among them to scale up sustainable agricultural production methods and market access. Introducing and capacitating women to use online portals and social media, linking them with potential markets, and providing more efficient modes of transporting products can help women boost their livelihood and income.

- Conduct gender awareness activities in communities. While it is evident that the involvement of women in agriculture activities is increasing over time, gender gaps still remain at the local level because of gender stereotypes which limit what women or men can and will do in their respective community. Studies have shown that men still tend to have more control over how to manage land and water resources, as well as farm machineries and equipment. Farming decisions such as the variety of seeds to plant, choice of fertilizers, management of water, and operation of farm equipment and machineries are predominantly determined by men. Such condition limits women to decide for themselves and participate in more income-generating activities through farming. Hence, gender awareness activities in the form of sensitivity workshops and capacity building activities are recommended to change farmers’ and fisherfolks’ perceptions and behavior about gender roles and allocation of resources between men and women.

- Develop localized Gender Action Plans. Mainstreaming gender into project development requires a clear set of goals which identify both immediate and long-term benefits to farmers and fisherfolk. It is recommended that the regional field offices of DA develop their respective Gender Action Plan built from the analysis of gender-differentiated vulnerabilities and risks of farmers and fisherfolks. This will guide regional planners in developing more gender-responsive projects and programs which can support in building not just climate-resilient, but also gender-transformative agriculture communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the DA RFO 5, UPLBFI (Ms. Dorcas Trinidad, Ms. Marteena Kyla Panopio, Ms. Patrisha Condes, and Ms. Kathreen Jules Plopinio), and the DA Climate Resilient Agriculture Office (CRAO) for providing the necessary funds, guidance, and support for the completion of this paper.

REFERENCES

Ani, P.A.B. and Casasola, H.C. (2020). Transcending barriers in agriculture through gender and development. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1872 on 26 April 2024

Asian Development Bank (2022). Gender Analysis Framework. Retrieved from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28723/agri2.pdf on 26 April 2024

Bayudan-Dacuycuy, C. 2018. Crafting policies and programs for women in the agriculture sector. Philippine Institute for Development Studies. Retrieved from https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidspn1808.pdf on 26 April 2024

FAO. 2022. National gender profile of agriculture and rural livelihoods – The Philippines. Country gender assessment series. Second revision. Manila, FAO.

Lambrou Y. and Nelson S. 2010. Farmers in a Changing Climate. Does Gender Matter? Food Security in Andhra Pradesh, India’, Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/i1721e/i1721e00.pdf on 26 April 2024

Lu, Jinky Leilanie (2011). Occupational Health and Safety of Women Workers: Viewed in the Light of Labor Regulations. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12(1), 68-78.

Paez Valencia, AM. 2020. Implementation of gender responsive research in development projects. World Agroforestry Guidance Note. Retrieved from https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/Publications/PDFS/TN21031.pdf on 26 April 2024

Philippine Commission on Women. 2021. Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry Sector. Retrieved from shorturl.at/iyAI3 on 26 April 2024

UN Women Watch. 2009. Fact Sheet: Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and... on 26 April 2024

UNDP. 2016. Gender and climate change: Overview of linkages between gender and climate change. Retrieved from shorturl.at/iwGNW on 26 April 2024

Wiebe, A. 2014. Applying the Harvard Gender Analytical Framework: A case study from a Maya-Mam community. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Carribean Studies. Vol. 22, No. 44 (1997), pp. 147-175

Building Climate-Resilient Agriculture Communities in the Philippines through a Gender Perspective

ABSTRACT

Social inequality, particularly in reference to gender, has already been recognized across the world as a pivotal issue in development. Gender gap is predominantly evident in sectors such as agriculture in which productivity depends on one’s access and control over agricultural inputs and resources. These inequalities and inequities are further exacerbated by the rapid changes in global climatic systems. Evidences show that there is disparity on the impacts of climate change among sectors, therefore, it is necessary to integrate gender considerations into the development of agricultural plans, projects, and programs. This paper gives insights on how to increase the adaptive capacity of farming communities in the Philippines to effectively address the impacts of climate change. Specific strategies on how to build more climate-resilient and gender-responsive agricultural communities are discussed such as provision of women-friendly equipment, machineries, and facilities, conduct of capacity building and gender-awareness campaigns, and development of localized Gender Action Plans.

Keywords: gender, agriculture, climate change, climate resilient agriculture

GENDER INCLUSION IN CLIMATE ACTION

In the recent years, efforts to achieve gender equality in the Philippines has been progressing, with the legislation of various laws, most notably, the Magna Carta of Women in 2009, and the Philippine Plan for Gender and Development 1995-2025. However, according to Bayudan-Dacuycuy (2018), challenges still persist particularly in the agriculture sector where women’s income remains to be just half of male agriculture workers. One of the reasons is that women are more likely to be involved in weeding and harvesting jobs, which are known to be less profitable than men’s traditional jobs in agriculture, such as plowing and land preparation (Ani and Casasola, 2020). Moreover, aside from women’s productive role in the society, their reproductive roles – caring for children and doing unpaid household work, make them perform multiple roles. According to the Philippine Commission on Women (PCW, 2021), these multiple roles make women under particular pressure, making their working days longer, rest hours shorter, and stress level higher.

These issues that women experience until today pose more conflicts given the persistent threats of climate change. In many contexts, women are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as compared to men, because they constitute the majority of the world’s poor and are more dependent on natural resources which are threatened by the changing environmental conditions. According to the United Nations Women Watch (2009), incorporating gender perspectives and involving women as agents of change is crucial to help the sector adapt to climate risks and vulnerabilities. Table 1 shows the four critical building blocks in response to climate change identified by the UN Women Watch.

Further, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2016) said that the vulnerabilities of sectors such as women, the elderly, immigrants, and indigenous groups are largely affected by the gender differentiated power, roles, and responsibilities at the household and community levels. According to UNDP (2016), 80% of people displaced by climate change are women and that they do not have easy and adequate access to funds to cover weather-related losses or adaptation technologies. They also face discrimination in accessing land, financial services, social capital, and technology. Another study by Lambrou and Nelson (2010) in agricultural areas in India showed how men and women farmers perceived and experienced climate variabilities, and how these affect their decision-making processes related to food security. The evidence presented in the study showed that due to gender roles (the behaviors, tasks and responsibilities a society defines as “male” or “female”) and the differential gendered access to resources, men and women experience climate variability differently and they have developed diverse coping strategies. The results reveal that coping mechanisms against climate variability, food security, and the overall well-being are significantly dictated by gender differences.

This shows that it is important to incorporate gender perspectives into policies, action plans, and other measures on sustainable development, and climate change adaptation and mitigation plans. To achieve this, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive gender analysis in order to identify specific gender-related gaps and constraints. The Harvard Analytical Framework is one the most commonly used frameworks for gender analysis because it can be easily adapted for use in agricultural production systems (Ludgate, 2016). It also helps to document the differences in the gendered access and control of resources, such as land, water, seeds, or extension information. The Gender Analysis Framework (GAF) for agriculture of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) follows the Harvard Analytical Framework as shown in Figure 1.

The Activity Profile identifies the gender divisions of labor in the community that are grouped into three types – productive activities, reproductive activities, and community involvement. On the other hand, the Access and Control Profile lists the resources needed to carry out tasks and benefits derived from them; access and control are disaggregated by gender. Lastly, the Influencing Factors Profile outlines the socio-economic contexts shaped by demographic, economic, legal, institution, cultural, religious, and behavioral structures affecting both the activity and the access and control profiles in the community.

CASE STUDY IN THE BICOL REGION

The Adaptation and Mitigation Initiative in Agriculture (AMIA) is the flagship program of the Department of Agriculture (DA) to address the impacts of climate change. Through the program, AMIA Villages are built across the country to promote Climate Resilient Agriculture and help farmers and fisherfolks in developing sustainable climate risk-based enterprises. To date, there are already 181 AMIA villages established across 59 provinces in the Philippines where climate-relevant support services are being introduced and implemented to address various climate change-related impacts. The AMIA program has already gained substantial milestones in building these communities to be climate-resilient, however, integration of gender considerations into agricultural planning remains to be one of the main challenges hindering sustainability and full adoption of projects and programs being deployed in AMIA Villages. While gender has already been recognized as an important aspect in agricultural planning, operationalization and implementation is not yet being fully practiced because of lack of resources and capacities for gender integration.

Hence, a gender-focused project was implemented by the DA Regional Field Office 5 (RFO 5) and the University of the Philippines Los Baños Foundation Inc. (UPLBFI) to demonstrate how gender can be integrated in the development of projects for AMIA Villages in the region. To gather necessary gender-related data, a total of 239 farmers were surveyed in six project sites across the Bicol region. Gender Analysis was conducted using the Harvard Analysis Framework. Assessment of the results showed that across the six sites, women are performing multiple roles as compared to men who are focused generally on managing and doing farm-related activities. While women are not hindered to participate in managing their farms (particularly rice farms) –land preparation, plowing, planting, harvesting, etc., women farmers are normally involved in managing the household - taking care of children and the elderly, preparing meals, and doing other household chores. Moreover, most of the women are also involved and in-charged in livestock and poultry raising, as well as vegetable farming, and management of the associations’ enterprises such as their Agri-Store. Women still take on very traditional gender roles but results of the study showed that both women and men farmers participate in livelihood activities and decide together on some key issues and tasks (e.g. household finances). However, looking at the access and control profiles, men still decide on land use that appears to be a main barrier for women’s access to income-generating activities as farming is the main source of income in the project sites.

Moreover, it was seen that in terms of adaptation strategies, men prefer infrastructure-related interventions which can improve conduct of farming activities. On the other hand, women respondents said that additional businesses and livelihoods can provide them additional sources of income that can be used for adaptation. Generally, all of the farmer beneficiaries believe that trainings and capacity building activities will help them better adapt to climate change impacts.

The study showed that in designing and developing projects, programs, and other support services, it is crucial to make use of the information gathered through the Gender Analysis. Services to be given to the beneficiaries must be tailor-fitted to their specific needs and requirements to ensure buy-in and sustainability. For instance, rabbit meat production is relatively an ‘unfamiliar’ practice in the country as rabbits are generally considered as pets. However, in Capalonga, Camarines Norte, the AMIA farmer beneficiaries have already started raising rabbits, with the support of its Local Government Unit (LGU) for meat production. Men farmers are mostly engaged in rabbit raising, thus, they have control over the income generated through this activity. As women are seen to be effective marketers, they were engaged to participate in the training for processing, packaging, and marketing of rabbit meat to further boost this as a livelihood and complement men farmers in promoting the rabbit meat industry in their community. In this case, and consistent with Paez (2020), it is shown that it is important to target value chains of products that are within the domain of women to ensure that they are more likely to receive and have control on payment for their work.

ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS THROUGH A GENDER PERSPECTIVE

Agriculture in the Philippines is still highly dominated by men. In the latest survey made by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) in 2016, women have only occupied 26% of the total agricultural employment since 2011 (Bayudan-Dacuycuy, 2018). According to Zwarteveen (2014), gender issues in agriculture result from ineffectiveness and inadequacy of technologies and institutional choices, and the differential impacts of development strategies on women and men. The disadvantages faced by women in agriculture in terms of access and control of land, water, and other related resources are reasons why policies, design, operation and management of agriculture systems should pay attention to gender concerns.

Social inequalities and inequities are further exacerbated by the rapid changes in global climatic systems. Evidences show that there is disparity on the impacts of climate change among sectors, therefore, it is important to develop plans and programs through a participatory, gender-responsive approach. To further promote gender integration at the local level, it is important to capacitate both planners and beneficiaries, and increase gender awareness and sensitivity among all stakeholders. Specifically, it is recommended to:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the DA RFO 5, UPLBFI (Ms. Dorcas Trinidad, Ms. Marteena Kyla Panopio, Ms. Patrisha Condes, and Ms. Kathreen Jules Plopinio), and the DA Climate Resilient Agriculture Office (CRAO) for providing the necessary funds, guidance, and support for the completion of this paper.

REFERENCES

Ani, P.A.B. and Casasola, H.C. (2020). Transcending barriers in agriculture through gender and development. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region. Retrieved from https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1872 on 26 April 2024

Asian Development Bank (2022). Gender Analysis Framework. Retrieved from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28723/agri2.pdf on 26 April 2024

Bayudan-Dacuycuy, C. 2018. Crafting policies and programs for women in the agriculture sector. Philippine Institute for Development Studies. Retrieved from https://pidswebs.pids.gov.ph/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidspn1808.pdf on 26 April 2024

FAO. 2022. National gender profile of agriculture and rural livelihoods – The Philippines. Country gender assessment series. Second revision. Manila, FAO.

Lambrou Y. and Nelson S. 2010. Farmers in a Changing Climate. Does Gender Matter? Food Security in Andhra Pradesh, India’, Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/3/i1721e/i1721e00.pdf on 26 April 2024

Lu, Jinky Leilanie (2011). Occupational Health and Safety of Women Workers: Viewed in the Light of Labor Regulations. Journal of International Women's Studies, 12(1), 68-78.

Paez Valencia, AM. 2020. Implementation of gender responsive research in development projects. World Agroforestry Guidance Note. Retrieved from https://apps.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/Publications/PDFS/TN21031.pdf on 26 April 2024

Philippine Commission on Women. 2021. Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry Sector. Retrieved from shorturl.at/iyAI3 on 26 April 2024

UN Women Watch. 2009. Fact Sheet: Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and... on 26 April 2024

UNDP. 2016. Gender and climate change: Overview of linkages between gender and climate change. Retrieved from shorturl.at/iwGNW on 26 April 2024

Wiebe, A. 2014. Applying the Harvard Gender Analytical Framework: A case study from a Maya-Mam community. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Carribean Studies. Vol. 22, No. 44 (1997), pp. 147-175