ABSTRACT

Food security is the concern of every nation including Malaysia. Despite of the country’s inability to produce its food domestically, food is available all-year round. In order to meet the demand from local consumers, Malaysia outsources its food supply, and thus, is a net importer of food. This country produces around 70% of its food products, while the balance is imported from all over the world. Report shows that the agrofood trade deficit is increasing every year, from around -RM16.76 (-US$3.99) billion in 2013 to more than -RM18.6 (-US$4.43) billion in 2018. The import of food is projected to further increase in the future, and this is the challenging time that the government of Malaysia must be prepared from now. Despite increased in real production of food crops, the supply is still unable to meet the increasing demand by domestic consumers. The Malaysian government has introduced many policies and initiatives as strategic plans to address the food security issues. The policies have changed from focusing on increasing the production of food to improving the purchasing power of the people. In other words, Malaysia will diversify the policies by enhancing the agrofood sector as to increase food production. At the same time, Malaysia will continue to be the net importer of food as a way to address food security in the future.

Keywords: Food security, agrofood, accessibility, affordability, healthy food

INTRODUCTION

Food security is a serious issue for every nation in the world, including Malaysia. Malaysia is facing a challenging time as the demand for food is increasing continuously year after year while the supply of food products from domestic farmlands is unable to meet the demand. In general, food production is only able to supply between 20% and 70% of the local consumers requirements. In 2019, Malaysia produced 70% of its rice, vegetables (74%), fruits (78%), fish (86%), beef (32%), mutton (23%) and milk (18%) (MOA, 2020). In order to meet the demand, Malaysia has to outsource its food supply from many countries in the world. Thus, the import of food products is increasing every year. Malaysia imported US$9.7 billion of food and beverage products in 2017, an increase of 3.5% from the previous year. Imports of food products will likely to grow moderately for the next ten years (GAIN, 2018).

Despite the low figures in local production of food products, Malaysia is generally a food secured nation. Malaysia was ranked 28th out of 113 countries by the Global Security index in 2019. All major foods are available sufficiently to meet the demand. However, one of the main issues related to food security in Malaysia is about the price increase of many food items. The higher demand from global markets creates opportunity to the entrepreneurs to export their products. This situation has reduced the supply of food products in the markets, and as a result, increased the price. The consumer price index of Malaysia has increased from 100 point index in 2010 to 120.7 point index in 2018 growing at an average annual rate of 3.48% (DOSM, 2020). This data reflected the change in the cost of purchasing food products to the average consumers.

Malaysian population will certainly grow exponentially over times. Currently, the population of Malaysia is around 33.33 million, and is projected to reach 45 million in 2050. The annual population growth rate has dropped from 2.0% in the early Independence in 1957, to only 0.4% in 2020. The increase in population will result in increase in demand for food. As a result, more land will be needed for farming and livestock husbandry. Unfortunately, the arable land suitable for farming is fast diminishing, from 0.75 ha per capita to a meager 0.17 ha per capita in 2030 (Yusof, 2010). Besides, unsustainable use has caused large area of land become degraded and unsuitable for food production. The extreme climate change also has shifted food production activities and reduced the yield. Natural disasters such as floods and long droughts also create uncertainty to food production. Floods are considered regular natural disasters in Malaysia, which happen nearly every year during the monsoon season. For example, the big floods in 2015 have damaged properties including farmlands valued around US$560 million. During that time, the food production was reported to drop down by 40%.

The higher demand for food and the higher purchasing power especially from developed countries has increased the price of food. In addition, a poor food supply chain has led to food scarcity in some place, while there was oversupply in the other places. Malaysia focused its food production for export markets to gain better revenue. At the same time, imports of food had increased continuously. For example, Malaysia’s spending on imports of food has increased from RM30 (US$7.14) billion in 2010 to RM50 (US$11.90) billion in 2018, with the average growth of 6.5% annually. The import of food products is projected to further increase in the future with the growth rate higher than the export value. Malaysia’s food trade deficit has increased from RM1.0 (US$0.24) billion in 1990, to RM8.5 (US$2.02) billion in 2006 and rose to 18.6 (US$4.43) billion in 2018. Malaysia imported high amounts of vegetables (RM4.6/US$1.10 billion), fish and crustaceans (RM4.1/US$0.98 billion), fruits (RM3.9/US$0.93 billion), meat (RM3.9/US$0.93 billion), sugar (RM3.8/US$0.90 billion) and dairy products (RM3.8/US$0.90 billion) in 2018 (MOA, 2019)

Food security issues are due to a growing population demanding more food, at the same time the country cannot afford to produce its own food supply. Despite increase in food production, the higher demand from domestic and global markets has led to the issue of food insecurity in the world and in Malaysia. This paper discusses the issues and challenges faced by Malaysia in addressing the food insecurity, and how it addresses it in the short and long terms.

FOOD SECURITY

The term food security has evolved more than 50 years and gradually shifted from the global level to household and individual levels (Jacques, Yves, Francis and Bernard, 2010). In the 1970s, the term food security was referred to food availability or the ability of a country to produce enough staple food for its people. In the 1980s, the concept has changed. It focuses on the physical and economic accessibility to food of each individual at any time. It also concerns about the food safety that could affect the health of the people. During this period, the eradication of poverty is the key to food security.

During 1990s, the concept of food security was expanded when the international community defined it to include three aspects: nutrition, food safety and cultural dimension, including the satisfaction of food preferences. In 1996, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) introduced the definition of food security during the World Food Summit, as “ Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”.

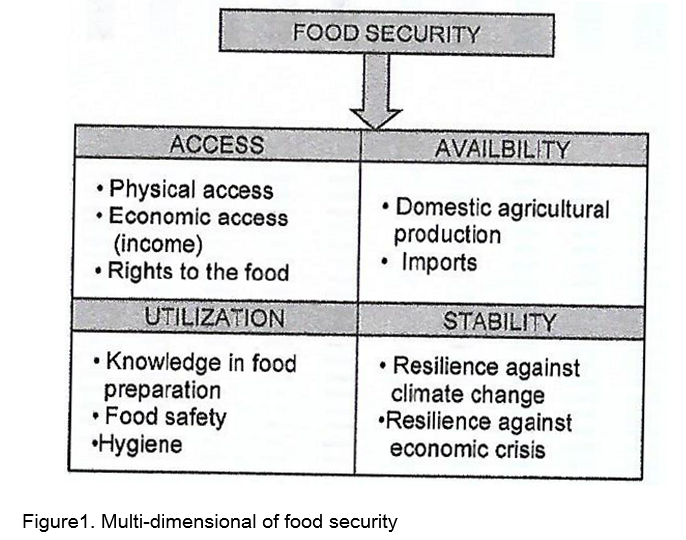

Under the definition, the FAO points out four dimensions of food security as follows:

- Food availability - sufficient supply through local production or from imports

- Food access - people has the access to food resources, such as in the markets or in the farms.

- Utilization - the importance of non-food inputs in food security

- Stability - the availability and accessibility of food at all time. Food supply is influenced by the social and physical environment, political and economic stability.

Very recently the concept has included the ethical and human rights dimensions, where all people must have the right to food. In other words, the issue of hunger and malnutrition has been taken care of, especially in poor countries. This concept also balances between the traditional notion of over nutrition in rich countries and under nutrition in poor developing countries. The multi-multidimensionality of food security can be figured out as follows:

A nation can be considered food secured when the food is available (physical access to food), people have the economic access to food, and equity of food distribution. The supply of food must be adequate in terms of quantity, quality and variety in able to secure the need by all people in the country. In general, the supply of food is determined by many factors, such as suitable ecosystem that include good arable land for crop production, abundance of water resources, and good climate. On the other hand, there are also many factors that could affect the availability of food supply in the short and long-term including extreme climate change, disasters, wars, civil unrests, population growth, agricultural practices, environment, social status and international trade. Socioeconomic factors that include disposable income, purchasing power, size of family, geographic location also affected the distribution of food and the ability of a person to access sufficient food.

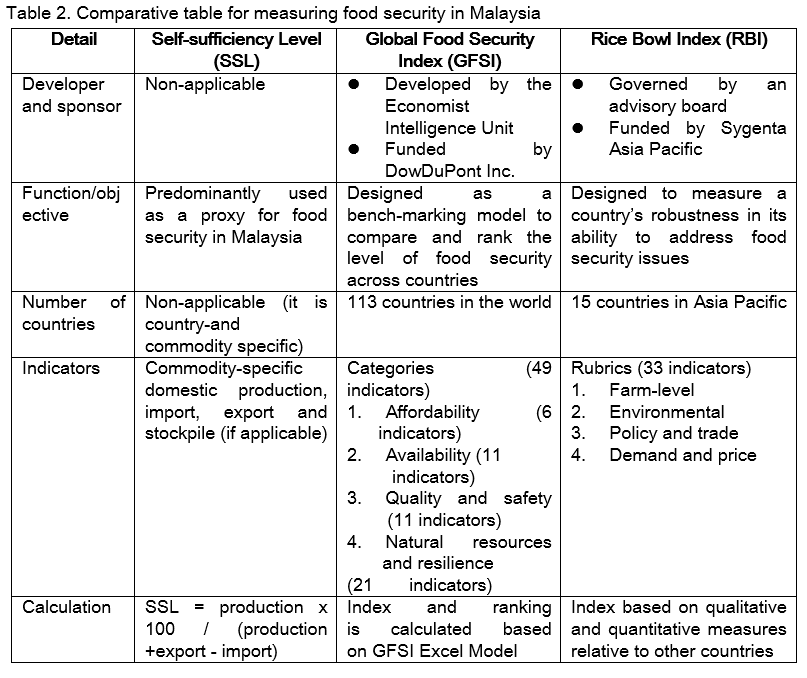

Malaysia used three indicators to measure its food security. The first one is by determining its self-sufficiency ratio or SSL. It is calculated by dividing the total domestic production with the total available supply in the country. The formula is stated as follows:

SSL =Production x 100/(Production +import -export)

The second indicator to determine its food security is by looking at the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) and the third, is by measuring the Rice Bowl Index (RBI). The GFSI measures the affordability of the people purchasing food products, the availability of food at any time and the quality and safety of the food supplied to the people. The RBI, on the other hand, examines the key enablers and disablers of food security that includes the farm-level factors, environmental factors, policy and trade, demand and price factors. It examines which factors will affect a country’s capacity to achieve or improve food security. The comparison between these indicators is as follows:

CURRENT SITUATIONS

In general, Malaysia currently is considered as a food secured nation. According to the GFSI report published in 2018, Malaysia was ranked number six within the Asia Pacific region in 2017, behind Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea (GFSI, 2018). Malaysia scores 67.7 out of 100 points, and is far better than its neighboring countries such as Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia. In the same year, Malaysia was ranked number 41 out of 113 countries in the world.

According to the Rice Bowl Index (RBI) report 2016, Malaysia performed well compared to 14 other countries. Malaysia scored 62 points as compared to the countries average score of 50 points (RBI, 2016). Malaysia also performed better than its neighboring countries including Thailand and Vietnam. The findings from both report indicates that the ability to produce staple food is not a good indicator for food security. This is true to some countries like Singapore, Japan and Malaysia. Singapore was ranked number one, while Japan was ranked 5th in the Global Food Security Index. Singapore has retained its position as the most food secured nation for many years even though it does not have a strong agricultural sector.

Food availability

Even though Malaysia cannot produce all food required by its people, the supply of food is sufficient all-year round. Malaysia produces some food commodities, and imports the balance. According to the GFSI report in 2018, the sufficiency supply of food has increased around 3% to reach 63.8 points, which is better than the world average (62.9 points) (GFSI, 2019).

Malaysia needs to outsource its food supply from other countries. The imports of food products have increased year after year. Malaysia's food trade balance has been in deficit since 2013. In 2018, Malaysia's food trade balance deficit stood at -RM18.60 billion (US$4.43 billion). This imbalance between food imports and exports came mainly from Malaysia's heavy reliance on food imports, especially for animal feeds, meat and meat products, and vegetables. In the same year, Malaysia imported around one million tons of rice, four million tons of maize, 6.5 million tons of cereals, 914,228 tons of oil seeds, 337.7 tons of meat, 249,528 tons of coffee and 72,172 tons of poultry meat (DOSM, 2020).

Rice is the staple food for Malaysian people. It is determined as the main indicator for food security, and used as the basis for policy design. Malaysian people consume rice everyday either as cooked rice or indirectly in the form of rice flour. On average, the people of Malaysia consumed around 80kg of rice per person, which is about 26% of the total calorie intake per day (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019). The consumption per capita of rice has reduced from 121 kg per person in 1961 to 86.5 kg per person in 2015, due to the change in food intake. Western food such as tortillas, pizza, pasta and bread are gaining popularity, especially in urban areas.

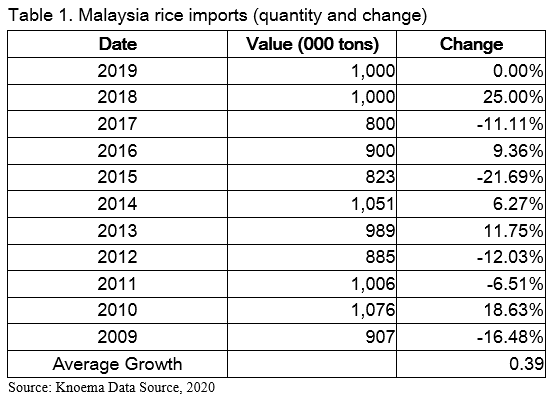

Every year Malaysia produces around 2.4 million tons of paddy. Over 30 years, the total production has increased, but still unable to meet the local demand. The consumption of rice is around 3.4 million tons. Malaysia is only able to produce between 60% and 70% of the local demand, hence, the self-sufficiency level is between 60 and 70%. Malaysia needs to import rice from many countries. In 2018, the main sources of rice are Thailand (48.8%), followed by Vietnam (25%), Cambodia (8.2%), India (7.8%), Pakistan (5.5%), Singapore (2.6%) and Myanmar (1.4%) (Tridge.com, 2020). The demand for rice is increasing greater than the production. This is reflected by the increase in import. During ten years’ time between 2009 and 2019, the average annual growth of rice import is 0.39% (Table 1)

Table 1 indicates that the import of rice has fluctuated every year, and it is determined by the projected local production of paddy. The import of rice increased significantly in 2010, 2011 and 2014 because the production was at the low level due to high flood events that hit the granary areas. Malaysia may continue to be a net importer of rice for the next ten years. The demand trends, geography condition (arable land and water resources) and consumer preferences for premium rice such as Basmati and Fragrance rice which is not being produced in Malaysia is likely to lead to the importation of rice. A study by Brian (2010) found that the demand for rice in 2050 is projected at 824.5% of what is produced in 2012, which is around 7.3 million tons.

The total production of poultry meat has increased from 1.4 million tons in 2015 to more than 1.8 million tons in 2018. Malaysia has long been fully self-sufficient in poultry, stands at 136.4% in 2014 and was stabilized at 116.3%% in 2018. The poultry industry has grown and has shifted from small-scale to commercial-scale breeders.

The production of beef has stayed constant for many years. Despite the increase in real production, import went up from 232,000 tons in 2015 to more than 350,000 tons in 2018, mainly from India and Australia (DVS, 2020). Malaysia has attempted to increase beef production by intensifying and integrating the husbandry of livestock with industrial crops such as oil palm. However, this effort has failed to increase the production of beef significantly. Almost all population of ruminants in Malaysia shows a big drop every year. For example, the population of cattle has dropped from 746,783 heads in 2014 to 737,827 heads in 2016 and further dropped to 710,481 heads in 2018. At the same time, the consumption of meat has increased significantly. For example, the consumption of beef has increased from 209,152 tons in 2014 to 216,604 tons in 2018 (DVS, 2020). As a result, the SSL for beef has also dropped from 25.29% in 2014 to 21.97% in 2018.

Fish and aquaculture products are also sources of protein for Malaysian population. The supply per capita has increased from 57.5 kg in 2015 to more than 59 kg in 2018. The supply of marine fish has also dropped from 1.482 million tons in 2013 to more than 1.452 million tons in 2018. As a result, the import of marine fish has increased from 567 tons in 2015 to more than 700 tons in 2018. Eggs are another major cheap source of protein. The amount of eggs available per capita has increased from 25 kg per person in 2015 to more 30 kg per person in 2018. Production of eggs has increased from 776,000 tons in 2015 to more than 850,000 tons in 2018. Malaysia produces eggs more than what is required in 2018, hence the SSL was 116.3%.

Fruits and vegetables are important sources of dietary fiber and nutrition. The supply per capita of vegetables has increased from 72 kg in 2013 to more than 82 kg in 2018. However, the increase in supply was due to increase in importation, rather than from local production. Production of vegetables has increased from 1.4 million tons in 2013 to more than 1.6 million tons, but is still unable to meet the demand by local consumers. The supply of fruits has not improved significantly. The supply per capita of fruit has increased from 71.6 kg in 2013 to more than 80.5 kg, also comes from importation. Production has decreased from 1.768 million tons in 2015 to 1.616 million tons in 2019. The trend is similar to vegetables, where the production has dropped from 1.373 million tons in 2015 to 1.069 million tons in 2019 (DOA, 2020).

The increase in the supply of food products indicates the total amount of food available has also increased. The increases in food supply have provided more than sufficient energy for all people in Malaysia. Malaysia has more food available, either from local production or imported from other countries.

Food accessibility

Access to food is another dimension of food security. Physical access refers to the ability of the people to get food from the sources that include the farm and marketplace. Malaysia is considered an urban nation because more than 70% of the population live in urban areas. Today, the retailing in Malaysia has enhanced new forms of retailing to cater to the needs of the consumers. People get access of their food from supermarkets, mini-markets, wet markets, dry markets, sundry/provision shops, discount stores, morning markets, agro-markets and even from on-line marketing. In 2018, the number of establishments for wholesale and retail trade sector in Malaysia recorded 469,024 as compared to 370,725 establishments in 2013. It is estimated more 262,650 outlets or 56% are selling food products in Malaysia (GAIN, 2018).

In general, food is correlated with the agricultural sector. The agricultural sector is the main source of food supply in Malaysia. Thus, in order to sustain the food security, the development of the agricultural sector must be enhanced in line with the demand and supply of food products. In Malaysia, the food production has increased every year. According to a report by NationMaster (2020), Malaysia’s food net production per capita has increased 0.2% every year since 2014. The 2019, net production per capita was US$110.62 Purchasing Power Parities (PPP)=2004-2006. Malaysia was ranked 78 out of 210 countries in the world. However, the growth of food production is slower than the growth of demand. As a comparison, Laos was the leading country with the net production per capita valued US$197.06 PPP=2004-2006 in 2019.

Currently, the government is encouraging urban community to produce their own food such as vegetables and fruits through a concept of urban farming community. The government promotes the urban farming in housing community by providing technologies such as fertigation system and agricultural inputs that include seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. By doing this, the urban community can get the access to food supply cheaply and continuously. This initiative will reduce the cost of living and ensure that the urban community will get healthy foods.

Food affordability

Malaysia is categorized as middle income nation. According to the GFSI index, the proportion of population under global poverty line was zero in 2019 that indicates in general, the income of people in Malaysia is above US$3.20 or RM13.45 per day. The average salary of Malaysian workers is RM2,441 (US$581.20) in 2019, while the poverty line income was set at RM2,208 (US$525.70) per month. In general, this income is sufficient for a household of five persons to purchase an optimum food requirements and healthy eating (DOSM, 2019)

Food expenditure constitutes a major spending of household in Malaysia. According to the GFSI report in 2019, the cost of purchasing food products has increased by 2.1% as compared to the previous year. Most households allocated large shares of their household expenditure to food, with the shares decreasing as incomes rise. According to a report by Department of Statistics, on average, household earning less than RM2,000 (US$476.20) a month spent 41.4% of their expenditures on food, whereas households earning at least RM15,000 (US$3571.40) a month spent an average of 23.4% in 2015. This figure is expected to be the same in the current situation, or may be larger.

Food affordability remains an issue for many people in Malaysia. The price of food has increased significantly after ten years. Certain food items, such as beef and milk have experienced price high over ten years. For example, over the past five years, Malaysia’s food prices have been on an upward trend. In fact, food prices have outpaced overall inflation. Between January 2010 and October 2015, Malaysia’s consumer price index (CPI) rose by 15%, while the food index increased by 23%, outpacing the CPI by 8%. In 2017, the consumer price index (CPI) has increased 69% since 2003, compared to a 42% rise in the overall CPI. This means food prices have increased more than overall price. Thus, the greater increase in food price will have a greater impact to especially the lower income consumers.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Malaysia’s agricultural policies can be divided into two phases: pre-independence and post-independence. The former (before 1957), the policy was aimed to serve the interest of the British colonial, which is focused on export commodities such as rubber, oil palm and cocoa. The agricultural policies and programs in the early stages of development in Malaysia were formulated to mainly address the issue of the high incidence of poverty in the agricultural sector, low foreign exchange reserves and rural development. Whereas, during the post-independence era, the focus is to steer the sector’s growth in two main areas: agriculture for domestic interests as well as crops for exports. For example, the National Agro-food Policy was formulated to address food security and safety to ensure the availability, affordability and accessibility of food. This objective could be achieved through the increase in productivity, increase in the using of machines and automation, intensify the production and strengthen the institutional management, especially at the farmers levels.

Since 2018, the government has decided to do a total reform of the agriculture sector that includes a change in the land management scheme. Under the new government, all government agencies are required to coordinate and work together in addressing the food security issues. The standalone policies were abolished and changed with a more comprehensive measure that integrated the food supply, processing, governance, environment and the food system life cycle. The policies also created the enabling conditions and a framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) number two which is to end hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition intake by the people. In other words, the new policy on food security set by Malaysia supported the sustainable development goals proposed by the United Nations.

Government initiatives for enhancing food production and ensuring food security including ensuring food-sufficiency, poverty eradication, productivity improvement were carried out continuously. Strategic options that include sustainable and efficient utilization of natural resources, such as land and water, proper application of agriculture inputs (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides) were implemented. This promoted the government to boost the agricultural programs to increase domestic production, hence, a revitalization era for agriculture in Malaysia that continues until today.

Price policy has become an important factor in addressing food security in Malaysia. The government imposed price control to stabilize the price, especially during the high demand seasons. Many food products have the ceiling price that the retailers must offer to the consumers, especially during the festival. For example, the ceiling price of chicken is set at maximum RM8/US$1.90 per kilogram during the festive season. The price is liberalized again or determined by supply and demand after the festive season ends, normally two weeks after the festive season. The government also determines the maximum prices of essential goods at the producer, wholesale and retail levels for specific duration, such as during Chinese New Year, Muslim Eid Festival, Deepavali and Christmas. The Malaysian government also introduced the Price Control and Anti-profiteering act in 2011 that aims to control prices of goods and charges for services, and to prohibit profiteering by retailers. Profiteering is defined as a person making unreasonably high profit in selling goods or services in Malaysia. Under this Act, any corporate body who commits an offense, is liable to a fine of up to RM500,000 (US$119,050) and, for a second or subsequent offense, to a fine not exceeding RM1 million (US$238,095). However, where such person is not a body corporate, he shall be liable to a fine of not exceeding RM100,000 (US$23,800) and/or imprisonment of up to three years.

What can be done?

In addressing the issue of food security in Malaysia, several actions could be done. For example, in addressing the food supply the following actions could be carried out:

The government should choose a crop with the highest land productivity (kg/hectare/year). For example, the average rice production in Malaysia is around 3,180 kg/hectare, as compared to China (6,932 kg/ha), Indonesia (5,414 kg/ha), United States of America (8,112 kg/ha), South Korea (7,222 kg/ha). The R&D in Malaysia must be intensified to produce new varieties that could increase the yield of paddy per hectare. Currently MARDI has produced 52 varieties of paddy and they are planted in all granary areas. As a comparison, India has produced more than 1,500 varieties, while the Philippines has produced more than 100 varieties of paddy. Thus, farmers have more choices of paddy seeds that are suitable for their farmland and weather in their areas.

- Grow crops using sustainable practice

In order to ensure that high yields can be sustained on a long term basis, good agricultural practices (GAPs) must be carried out in all farms. The GAPs must be enforced to be implemented by all farmers in Malaysia. Currently, the implementation is on the voluntary basis. These GAPs will govern the wise use of land such as soil erosion control, increase the farm productivity and reduce the risk of contamination of agricultural produce. Good agricultural practices will lead to food safety with the points like harvesting, transportation of products and guidelines to the grower to implement the general recommendation of adopted the best management practices. This practice will at the end, increase the yield and the quality of food products.

The use of land can be maximized by carrying out inter-cropping of food crops. More food crops can be obtained on the same parcel of land. Inter cropping between oil palm and short term crops such as bananas, water melons and vegetables will increase food production. Similarly, the integration between food crops and livestock husbandry such as cattle grazing, farmers can obtain two or more agricultural produce from the same farmlands. For example, the integration between oil palm and cattle husbandry will produce palm oil, meat and milk from cattle. This effort will also reduce the cost of production.

- Preparation for water crisis

The source of water in Malaysia has been depleting and degrading. The demand for water in Malaysia has increased from 8.9 billion m3 in 1980 to 15.5 billion m3 in 2000 for agricultural, industrial and domestic purposes. Agriculture sector uses approximately 76% of all available water (Siwar and Ahmed, 2014). The exploration of virgin jungle for water treatment has destroyed the source of water for agricultural activities. The water scarcity will critically affect food production. It is timely for Malaysia to study and produce food crops that use less water or use water efficiently. The application of technologies for water management in the agricultural sector should be intensified such as drip irrigation, irrigation scheduling, use of drought-tolerant crops, dry farming, rotational grazing, cover crops and others.

- Improve the supply chain from farm to table

Agricultural supply chains refer to the flow of products and information between the players that include farmers, middlemen and consumers. In general, these players are working separately to gain better profits. The success of the supply chain is determined by how well the players coordinate and integrate the activities along the supply chain from farms to consumers. The industry players need to improve the supply chain so that their products can reach the consumers efficiently and effectively. The players need to redesign the whole process of supply chain, so that they can reduce the cost and increase the profit margin. In this case, government agencies such as the Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority (FAMA) can play its roles by providing data and information, and provide the monitoring system that could control the activities effectively.

The application of data and on-line marketing for example, can help farmers to plan their production based on the quantity and time demanded by consumers. In other words, the customization of products can also be applied in the agricultural sector. In this case, the government agencies should play a greater role by collecting and sharing the data with the industry players. The improvement the relationship between warehouse and transportation can also improve the distribution of products in many areas. This will reduce the postharvest loss and at the same time sustain the quality of the products.

CONCLUSION

Agriculture and food are fundamental for all nations including Malaysia. Achieving food security means ensuring that all people have access to sufficient food, can afford to buy and receive quality and nutritious food. Food security has been the concern of the government and many initiatives have been introduced as strategies to ensure that people get sufficient and healthy food. The government integrates all efforts that include conducting R&D for the development of new technologies, managing the production of food crops and livestock, creating efficient supply-chain and managing the import of food products effectively.

Food security is not a simple matter that can be addressed by increasing food supply and reducing the price of food, so that people can access and afford to buy food. Its fundamental purpose is to increase the purchasing power of the people and help reduce poverty. Malaysia must be brave to face the current and future challenging times, especially when the demand for food is increasing, while the domestic production is increasing at a growth rate lower than the demand. The agriculture sector is the main source of food in Malaysia. The development of the agricultural sector is determined by good strategic plans and good government policies. The future agricultural policies should not be driven by increasing the production of food commodities. The policy should also consider other elements such as food safety, healthy food, traceability of food, especially food coming from other countries and environmental sustainability.

The Malaysian government aspires to improve the food security by integrating all efforts through programs and projects carried out by government agencies, private sectors and farmers associations that could bring the country to a higher income status by 2030.

REFERENCES

Bryan Paul (2013) Food Security in Malaysia: Challenges and Opportunities for Malaysia of Present and in 2050 for maintaining foods security. University of Alberta.

DOA (2019). Statistics of food crops in Malaysia 2019.

DOA (2020). Statistics of food crops in Malaysia 2020.

DOSM (2020). Household expenditure and consumer price index 2019.

Global Agricultural Information Network (2018). Malaysia Retail Foods. GAIN Report Number My8004. 2018.

MOA (2019) Statistics of agro-food production, consumption and trading, 2019.

Siwar, C and Ahmad, F. (2014). Concepts, Dimensions and Elements of Eater Security. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 13 (5):281-286, 2014.

Addressing Food Security in Challenging Times

ABSTRACT

Food security is the concern of every nation including Malaysia. Despite of the country’s inability to produce its food domestically, food is available all-year round. In order to meet the demand from local consumers, Malaysia outsources its food supply, and thus, is a net importer of food. This country produces around 70% of its food products, while the balance is imported from all over the world. Report shows that the agrofood trade deficit is increasing every year, from around -RM16.76 (-US$3.99) billion in 2013 to more than -RM18.6 (-US$4.43) billion in 2018. The import of food is projected to further increase in the future, and this is the challenging time that the government of Malaysia must be prepared from now. Despite increased in real production of food crops, the supply is still unable to meet the increasing demand by domestic consumers. The Malaysian government has introduced many policies and initiatives as strategic plans to address the food security issues. The policies have changed from focusing on increasing the production of food to improving the purchasing power of the people. In other words, Malaysia will diversify the policies by enhancing the agrofood sector as to increase food production. At the same time, Malaysia will continue to be the net importer of food as a way to address food security in the future.

Keywords: Food security, agrofood, accessibility, affordability, healthy food

INTRODUCTION

Food security is a serious issue for every nation in the world, including Malaysia. Malaysia is facing a challenging time as the demand for food is increasing continuously year after year while the supply of food products from domestic farmlands is unable to meet the demand. In general, food production is only able to supply between 20% and 70% of the local consumers requirements. In 2019, Malaysia produced 70% of its rice, vegetables (74%), fruits (78%), fish (86%), beef (32%), mutton (23%) and milk (18%) (MOA, 2020). In order to meet the demand, Malaysia has to outsource its food supply from many countries in the world. Thus, the import of food products is increasing every year. Malaysia imported US$9.7 billion of food and beverage products in 2017, an increase of 3.5% from the previous year. Imports of food products will likely to grow moderately for the next ten years (GAIN, 2018).

Despite the low figures in local production of food products, Malaysia is generally a food secured nation. Malaysia was ranked 28th out of 113 countries by the Global Security index in 2019. All major foods are available sufficiently to meet the demand. However, one of the main issues related to food security in Malaysia is about the price increase of many food items. The higher demand from global markets creates opportunity to the entrepreneurs to export their products. This situation has reduced the supply of food products in the markets, and as a result, increased the price. The consumer price index of Malaysia has increased from 100 point index in 2010 to 120.7 point index in 2018 growing at an average annual rate of 3.48% (DOSM, 2020). This data reflected the change in the cost of purchasing food products to the average consumers.

Malaysian population will certainly grow exponentially over times. Currently, the population of Malaysia is around 33.33 million, and is projected to reach 45 million in 2050. The annual population growth rate has dropped from 2.0% in the early Independence in 1957, to only 0.4% in 2020. The increase in population will result in increase in demand for food. As a result, more land will be needed for farming and livestock husbandry. Unfortunately, the arable land suitable for farming is fast diminishing, from 0.75 ha per capita to a meager 0.17 ha per capita in 2030 (Yusof, 2010). Besides, unsustainable use has caused large area of land become degraded and unsuitable for food production. The extreme climate change also has shifted food production activities and reduced the yield. Natural disasters such as floods and long droughts also create uncertainty to food production. Floods are considered regular natural disasters in Malaysia, which happen nearly every year during the monsoon season. For example, the big floods in 2015 have damaged properties including farmlands valued around US$560 million. During that time, the food production was reported to drop down by 40%.

The higher demand for food and the higher purchasing power especially from developed countries has increased the price of food. In addition, a poor food supply chain has led to food scarcity in some place, while there was oversupply in the other places. Malaysia focused its food production for export markets to gain better revenue. At the same time, imports of food had increased continuously. For example, Malaysia’s spending on imports of food has increased from RM30 (US$7.14) billion in 2010 to RM50 (US$11.90) billion in 2018, with the average growth of 6.5% annually. The import of food products is projected to further increase in the future with the growth rate higher than the export value. Malaysia’s food trade deficit has increased from RM1.0 (US$0.24) billion in 1990, to RM8.5 (US$2.02) billion in 2006 and rose to 18.6 (US$4.43) billion in 2018. Malaysia imported high amounts of vegetables (RM4.6/US$1.10 billion), fish and crustaceans (RM4.1/US$0.98 billion), fruits (RM3.9/US$0.93 billion), meat (RM3.9/US$0.93 billion), sugar (RM3.8/US$0.90 billion) and dairy products (RM3.8/US$0.90 billion) in 2018 (MOA, 2019)

Food security issues are due to a growing population demanding more food, at the same time the country cannot afford to produce its own food supply. Despite increase in food production, the higher demand from domestic and global markets has led to the issue of food insecurity in the world and in Malaysia. This paper discusses the issues and challenges faced by Malaysia in addressing the food insecurity, and how it addresses it in the short and long terms.

FOOD SECURITY

The term food security has evolved more than 50 years and gradually shifted from the global level to household and individual levels (Jacques, Yves, Francis and Bernard, 2010). In the 1970s, the term food security was referred to food availability or the ability of a country to produce enough staple food for its people. In the 1980s, the concept has changed. It focuses on the physical and economic accessibility to food of each individual at any time. It also concerns about the food safety that could affect the health of the people. During this period, the eradication of poverty is the key to food security.

During 1990s, the concept of food security was expanded when the international community defined it to include three aspects: nutrition, food safety and cultural dimension, including the satisfaction of food preferences. In 1996, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) introduced the definition of food security during the World Food Summit, as “ Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”.

Under the definition, the FAO points out four dimensions of food security as follows:

Very recently the concept has included the ethical and human rights dimensions, where all people must have the right to food. In other words, the issue of hunger and malnutrition has been taken care of, especially in poor countries. This concept also balances between the traditional notion of over nutrition in rich countries and under nutrition in poor developing countries. The multi-multidimensionality of food security can be figured out as follows:

A nation can be considered food secured when the food is available (physical access to food), people have the economic access to food, and equity of food distribution. The supply of food must be adequate in terms of quantity, quality and variety in able to secure the need by all people in the country. In general, the supply of food is determined by many factors, such as suitable ecosystem that include good arable land for crop production, abundance of water resources, and good climate. On the other hand, there are also many factors that could affect the availability of food supply in the short and long-term including extreme climate change, disasters, wars, civil unrests, population growth, agricultural practices, environment, social status and international trade. Socioeconomic factors that include disposable income, purchasing power, size of family, geographic location also affected the distribution of food and the ability of a person to access sufficient food.

Malaysia used three indicators to measure its food security. The first one is by determining its self-sufficiency ratio or SSL. It is calculated by dividing the total domestic production with the total available supply in the country. The formula is stated as follows:

SSL =Production x 100/(Production +import -export)

The second indicator to determine its food security is by looking at the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) and the third, is by measuring the Rice Bowl Index (RBI). The GFSI measures the affordability of the people purchasing food products, the availability of food at any time and the quality and safety of the food supplied to the people. The RBI, on the other hand, examines the key enablers and disablers of food security that includes the farm-level factors, environmental factors, policy and trade, demand and price factors. It examines which factors will affect a country’s capacity to achieve or improve food security. The comparison between these indicators is as follows:

CURRENT SITUATIONS

In general, Malaysia currently is considered as a food secured nation. According to the GFSI report published in 2018, Malaysia was ranked number six within the Asia Pacific region in 2017, behind Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea (GFSI, 2018). Malaysia scores 67.7 out of 100 points, and is far better than its neighboring countries such as Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia. In the same year, Malaysia was ranked number 41 out of 113 countries in the world.

According to the Rice Bowl Index (RBI) report 2016, Malaysia performed well compared to 14 other countries. Malaysia scored 62 points as compared to the countries average score of 50 points (RBI, 2016). Malaysia also performed better than its neighboring countries including Thailand and Vietnam. The findings from both report indicates that the ability to produce staple food is not a good indicator for food security. This is true to some countries like Singapore, Japan and Malaysia. Singapore was ranked number one, while Japan was ranked 5th in the Global Food Security Index. Singapore has retained its position as the most food secured nation for many years even though it does not have a strong agricultural sector.

Food availability

Even though Malaysia cannot produce all food required by its people, the supply of food is sufficient all-year round. Malaysia produces some food commodities, and imports the balance. According to the GFSI report in 2018, the sufficiency supply of food has increased around 3% to reach 63.8 points, which is better than the world average (62.9 points) (GFSI, 2019).

Malaysia needs to outsource its food supply from other countries. The imports of food products have increased year after year. Malaysia's food trade balance has been in deficit since 2013. In 2018, Malaysia's food trade balance deficit stood at -RM18.60 billion (US$4.43 billion). This imbalance between food imports and exports came mainly from Malaysia's heavy reliance on food imports, especially for animal feeds, meat and meat products, and vegetables. In the same year, Malaysia imported around one million tons of rice, four million tons of maize, 6.5 million tons of cereals, 914,228 tons of oil seeds, 337.7 tons of meat, 249,528 tons of coffee and 72,172 tons of poultry meat (DOSM, 2020).

Rice is the staple food for Malaysian people. It is determined as the main indicator for food security, and used as the basis for policy design. Malaysian people consume rice everyday either as cooked rice or indirectly in the form of rice flour. On average, the people of Malaysia consumed around 80kg of rice per person, which is about 26% of the total calorie intake per day (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019). The consumption per capita of rice has reduced from 121 kg per person in 1961 to 86.5 kg per person in 2015, due to the change in food intake. Western food such as tortillas, pizza, pasta and bread are gaining popularity, especially in urban areas.

Every year Malaysia produces around 2.4 million tons of paddy. Over 30 years, the total production has increased, but still unable to meet the local demand. The consumption of rice is around 3.4 million tons. Malaysia is only able to produce between 60% and 70% of the local demand, hence, the self-sufficiency level is between 60 and 70%. Malaysia needs to import rice from many countries. In 2018, the main sources of rice are Thailand (48.8%), followed by Vietnam (25%), Cambodia (8.2%), India (7.8%), Pakistan (5.5%), Singapore (2.6%) and Myanmar (1.4%) (Tridge.com, 2020). The demand for rice is increasing greater than the production. This is reflected by the increase in import. During ten years’ time between 2009 and 2019, the average annual growth of rice import is 0.39% (Table 1)

Table 1 indicates that the import of rice has fluctuated every year, and it is determined by the projected local production of paddy. The import of rice increased significantly in 2010, 2011 and 2014 because the production was at the low level due to high flood events that hit the granary areas. Malaysia may continue to be a net importer of rice for the next ten years. The demand trends, geography condition (arable land and water resources) and consumer preferences for premium rice such as Basmati and Fragrance rice which is not being produced in Malaysia is likely to lead to the importation of rice. A study by Brian (2010) found that the demand for rice in 2050 is projected at 824.5% of what is produced in 2012, which is around 7.3 million tons.

The total production of poultry meat has increased from 1.4 million tons in 2015 to more than 1.8 million tons in 2018. Malaysia has long been fully self-sufficient in poultry, stands at 136.4% in 2014 and was stabilized at 116.3%% in 2018. The poultry industry has grown and has shifted from small-scale to commercial-scale breeders.

The production of beef has stayed constant for many years. Despite the increase in real production, import went up from 232,000 tons in 2015 to more than 350,000 tons in 2018, mainly from India and Australia (DVS, 2020). Malaysia has attempted to increase beef production by intensifying and integrating the husbandry of livestock with industrial crops such as oil palm. However, this effort has failed to increase the production of beef significantly. Almost all population of ruminants in Malaysia shows a big drop every year. For example, the population of cattle has dropped from 746,783 heads in 2014 to 737,827 heads in 2016 and further dropped to 710,481 heads in 2018. At the same time, the consumption of meat has increased significantly. For example, the consumption of beef has increased from 209,152 tons in 2014 to 216,604 tons in 2018 (DVS, 2020). As a result, the SSL for beef has also dropped from 25.29% in 2014 to 21.97% in 2018.

Fish and aquaculture products are also sources of protein for Malaysian population. The supply per capita has increased from 57.5 kg in 2015 to more than 59 kg in 2018. The supply of marine fish has also dropped from 1.482 million tons in 2013 to more than 1.452 million tons in 2018. As a result, the import of marine fish has increased from 567 tons in 2015 to more than 700 tons in 2018. Eggs are another major cheap source of protein. The amount of eggs available per capita has increased from 25 kg per person in 2015 to more 30 kg per person in 2018. Production of eggs has increased from 776,000 tons in 2015 to more than 850,000 tons in 2018. Malaysia produces eggs more than what is required in 2018, hence the SSL was 116.3%.

Fruits and vegetables are important sources of dietary fiber and nutrition. The supply per capita of vegetables has increased from 72 kg in 2013 to more than 82 kg in 2018. However, the increase in supply was due to increase in importation, rather than from local production. Production of vegetables has increased from 1.4 million tons in 2013 to more than 1.6 million tons, but is still unable to meet the demand by local consumers. The supply of fruits has not improved significantly. The supply per capita of fruit has increased from 71.6 kg in 2013 to more than 80.5 kg, also comes from importation. Production has decreased from 1.768 million tons in 2015 to 1.616 million tons in 2019. The trend is similar to vegetables, where the production has dropped from 1.373 million tons in 2015 to 1.069 million tons in 2019 (DOA, 2020).

The increase in the supply of food products indicates the total amount of food available has also increased. The increases in food supply have provided more than sufficient energy for all people in Malaysia. Malaysia has more food available, either from local production or imported from other countries.

Food accessibility

Access to food is another dimension of food security. Physical access refers to the ability of the people to get food from the sources that include the farm and marketplace. Malaysia is considered an urban nation because more than 70% of the population live in urban areas. Today, the retailing in Malaysia has enhanced new forms of retailing to cater to the needs of the consumers. People get access of their food from supermarkets, mini-markets, wet markets, dry markets, sundry/provision shops, discount stores, morning markets, agro-markets and even from on-line marketing. In 2018, the number of establishments for wholesale and retail trade sector in Malaysia recorded 469,024 as compared to 370,725 establishments in 2013. It is estimated more 262,650 outlets or 56% are selling food products in Malaysia (GAIN, 2018).

In general, food is correlated with the agricultural sector. The agricultural sector is the main source of food supply in Malaysia. Thus, in order to sustain the food security, the development of the agricultural sector must be enhanced in line with the demand and supply of food products. In Malaysia, the food production has increased every year. According to a report by NationMaster (2020), Malaysia’s food net production per capita has increased 0.2% every year since 2014. The 2019, net production per capita was US$110.62 Purchasing Power Parities (PPP)=2004-2006. Malaysia was ranked 78 out of 210 countries in the world. However, the growth of food production is slower than the growth of demand. As a comparison, Laos was the leading country with the net production per capita valued US$197.06 PPP=2004-2006 in 2019.

Currently, the government is encouraging urban community to produce their own food such as vegetables and fruits through a concept of urban farming community. The government promotes the urban farming in housing community by providing technologies such as fertigation system and agricultural inputs that include seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. By doing this, the urban community can get the access to food supply cheaply and continuously. This initiative will reduce the cost of living and ensure that the urban community will get healthy foods.

Food affordability

Malaysia is categorized as middle income nation. According to the GFSI index, the proportion of population under global poverty line was zero in 2019 that indicates in general, the income of people in Malaysia is above US$3.20 or RM13.45 per day. The average salary of Malaysian workers is RM2,441 (US$581.20) in 2019, while the poverty line income was set at RM2,208 (US$525.70) per month. In general, this income is sufficient for a household of five persons to purchase an optimum food requirements and healthy eating (DOSM, 2019)

Food expenditure constitutes a major spending of household in Malaysia. According to the GFSI report in 2019, the cost of purchasing food products has increased by 2.1% as compared to the previous year. Most households allocated large shares of their household expenditure to food, with the shares decreasing as incomes rise. According to a report by Department of Statistics, on average, household earning less than RM2,000 (US$476.20) a month spent 41.4% of their expenditures on food, whereas households earning at least RM15,000 (US$3571.40) a month spent an average of 23.4% in 2015. This figure is expected to be the same in the current situation, or may be larger.

Food affordability remains an issue for many people in Malaysia. The price of food has increased significantly after ten years. Certain food items, such as beef and milk have experienced price high over ten years. For example, over the past five years, Malaysia’s food prices have been on an upward trend. In fact, food prices have outpaced overall inflation. Between January 2010 and October 2015, Malaysia’s consumer price index (CPI) rose by 15%, while the food index increased by 23%, outpacing the CPI by 8%. In 2017, the consumer price index (CPI) has increased 69% since 2003, compared to a 42% rise in the overall CPI. This means food prices have increased more than overall price. Thus, the greater increase in food price will have a greater impact to especially the lower income consumers.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Malaysia’s agricultural policies can be divided into two phases: pre-independence and post-independence. The former (before 1957), the policy was aimed to serve the interest of the British colonial, which is focused on export commodities such as rubber, oil palm and cocoa. The agricultural policies and programs in the early stages of development in Malaysia were formulated to mainly address the issue of the high incidence of poverty in the agricultural sector, low foreign exchange reserves and rural development. Whereas, during the post-independence era, the focus is to steer the sector’s growth in two main areas: agriculture for domestic interests as well as crops for exports. For example, the National Agro-food Policy was formulated to address food security and safety to ensure the availability, affordability and accessibility of food. This objective could be achieved through the increase in productivity, increase in the using of machines and automation, intensify the production and strengthen the institutional management, especially at the farmers levels.

Since 2018, the government has decided to do a total reform of the agriculture sector that includes a change in the land management scheme. Under the new government, all government agencies are required to coordinate and work together in addressing the food security issues. The standalone policies were abolished and changed with a more comprehensive measure that integrated the food supply, processing, governance, environment and the food system life cycle. The policies also created the enabling conditions and a framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) number two which is to end hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition intake by the people. In other words, the new policy on food security set by Malaysia supported the sustainable development goals proposed by the United Nations.

Government initiatives for enhancing food production and ensuring food security including ensuring food-sufficiency, poverty eradication, productivity improvement were carried out continuously. Strategic options that include sustainable and efficient utilization of natural resources, such as land and water, proper application of agriculture inputs (seeds, fertilizers, pesticides) were implemented. This promoted the government to boost the agricultural programs to increase domestic production, hence, a revitalization era for agriculture in Malaysia that continues until today.

Price policy has become an important factor in addressing food security in Malaysia. The government imposed price control to stabilize the price, especially during the high demand seasons. Many food products have the ceiling price that the retailers must offer to the consumers, especially during the festival. For example, the ceiling price of chicken is set at maximum RM8/US$1.90 per kilogram during the festive season. The price is liberalized again or determined by supply and demand after the festive season ends, normally two weeks after the festive season. The government also determines the maximum prices of essential goods at the producer, wholesale and retail levels for specific duration, such as during Chinese New Year, Muslim Eid Festival, Deepavali and Christmas. The Malaysian government also introduced the Price Control and Anti-profiteering act in 2011 that aims to control prices of goods and charges for services, and to prohibit profiteering by retailers. Profiteering is defined as a person making unreasonably high profit in selling goods or services in Malaysia. Under this Act, any corporate body who commits an offense, is liable to a fine of up to RM500,000 (US$119,050) and, for a second or subsequent offense, to a fine not exceeding RM1 million (US$238,095). However, where such person is not a body corporate, he shall be liable to a fine of not exceeding RM100,000 (US$23,800) and/or imprisonment of up to three years.

What can be done?

In addressing the issue of food security in Malaysia, several actions could be done. For example, in addressing the food supply the following actions could be carried out:

The government should choose a crop with the highest land productivity (kg/hectare/year). For example, the average rice production in Malaysia is around 3,180 kg/hectare, as compared to China (6,932 kg/ha), Indonesia (5,414 kg/ha), United States of America (8,112 kg/ha), South Korea (7,222 kg/ha). The R&D in Malaysia must be intensified to produce new varieties that could increase the yield of paddy per hectare. Currently MARDI has produced 52 varieties of paddy and they are planted in all granary areas. As a comparison, India has produced more than 1,500 varieties, while the Philippines has produced more than 100 varieties of paddy. Thus, farmers have more choices of paddy seeds that are suitable for their farmland and weather in their areas.

In order to ensure that high yields can be sustained on a long term basis, good agricultural practices (GAPs) must be carried out in all farms. The GAPs must be enforced to be implemented by all farmers in Malaysia. Currently, the implementation is on the voluntary basis. These GAPs will govern the wise use of land such as soil erosion control, increase the farm productivity and reduce the risk of contamination of agricultural produce. Good agricultural practices will lead to food safety with the points like harvesting, transportation of products and guidelines to the grower to implement the general recommendation of adopted the best management practices. This practice will at the end, increase the yield and the quality of food products.

The use of land can be maximized by carrying out inter-cropping of food crops. More food crops can be obtained on the same parcel of land. Inter cropping between oil palm and short term crops such as bananas, water melons and vegetables will increase food production. Similarly, the integration between food crops and livestock husbandry such as cattle grazing, farmers can obtain two or more agricultural produce from the same farmlands. For example, the integration between oil palm and cattle husbandry will produce palm oil, meat and milk from cattle. This effort will also reduce the cost of production.

The source of water in Malaysia has been depleting and degrading. The demand for water in Malaysia has increased from 8.9 billion m3 in 1980 to 15.5 billion m3 in 2000 for agricultural, industrial and domestic purposes. Agriculture sector uses approximately 76% of all available water (Siwar and Ahmed, 2014). The exploration of virgin jungle for water treatment has destroyed the source of water for agricultural activities. The water scarcity will critically affect food production. It is timely for Malaysia to study and produce food crops that use less water or use water efficiently. The application of technologies for water management in the agricultural sector should be intensified such as drip irrigation, irrigation scheduling, use of drought-tolerant crops, dry farming, rotational grazing, cover crops and others.

Agricultural supply chains refer to the flow of products and information between the players that include farmers, middlemen and consumers. In general, these players are working separately to gain better profits. The success of the supply chain is determined by how well the players coordinate and integrate the activities along the supply chain from farms to consumers. The industry players need to improve the supply chain so that their products can reach the consumers efficiently and effectively. The players need to redesign the whole process of supply chain, so that they can reduce the cost and increase the profit margin. In this case, government agencies such as the Federal Agricultural Marketing Authority (FAMA) can play its roles by providing data and information, and provide the monitoring system that could control the activities effectively.

The application of data and on-line marketing for example, can help farmers to plan their production based on the quantity and time demanded by consumers. In other words, the customization of products can also be applied in the agricultural sector. In this case, the government agencies should play a greater role by collecting and sharing the data with the industry players. The improvement the relationship between warehouse and transportation can also improve the distribution of products in many areas. This will reduce the postharvest loss and at the same time sustain the quality of the products.

CONCLUSION

Agriculture and food are fundamental for all nations including Malaysia. Achieving food security means ensuring that all people have access to sufficient food, can afford to buy and receive quality and nutritious food. Food security has been the concern of the government and many initiatives have been introduced as strategies to ensure that people get sufficient and healthy food. The government integrates all efforts that include conducting R&D for the development of new technologies, managing the production of food crops and livestock, creating efficient supply-chain and managing the import of food products effectively.

Food security is not a simple matter that can be addressed by increasing food supply and reducing the price of food, so that people can access and afford to buy food. Its fundamental purpose is to increase the purchasing power of the people and help reduce poverty. Malaysia must be brave to face the current and future challenging times, especially when the demand for food is increasing, while the domestic production is increasing at a growth rate lower than the demand. The agriculture sector is the main source of food in Malaysia. The development of the agricultural sector is determined by good strategic plans and good government policies. The future agricultural policies should not be driven by increasing the production of food commodities. The policy should also consider other elements such as food safety, healthy food, traceability of food, especially food coming from other countries and environmental sustainability.

The Malaysian government aspires to improve the food security by integrating all efforts through programs and projects carried out by government agencies, private sectors and farmers associations that could bring the country to a higher income status by 2030.

REFERENCES

Bryan Paul (2013) Food Security in Malaysia: Challenges and Opportunities for Malaysia of Present and in 2050 for maintaining foods security. University of Alberta.

DOA (2019). Statistics of food crops in Malaysia 2019.

DOA (2020). Statistics of food crops in Malaysia 2020.

DOSM (2020). Household expenditure and consumer price index 2019.

Global Agricultural Information Network (2018). Malaysia Retail Foods. GAIN Report Number My8004. 2018.

MOA (2019) Statistics of agro-food production, consumption and trading, 2019.

Siwar, C and Ahmad, F. (2014). Concepts, Dimensions and Elements of Eater Security. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 13 (5):281-286, 2014.