ABSTRACT

The Fisheries Act stipulates the basic framework of Japan’s fishery policy. According to the types of rules and regulations on fishing activities, the Fisheries Act has three categories for types of fishing: Kyoka Gyogyo (“licensed fishery”); Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo (“fishing-right-based fishery”); and Jiyu Gyogyo (“free fishery”). This paper aims to describe the rules and regulations on these three types of fisheries.

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s fishery policy is in the midst of the biggest reform of the post-Pacific War period. In November 2018, the Japanese government submitted a bill to the Diet for a large-scale amendment to the Fisheries Act, which has served as the framework for the current Japanese fishery policy since its establishment in 1949. The bill passed in December 2018, and the enactment of the amended Fisheries Act is scheduled for December 2020.

What is the purpose of this reform? How will Japan’s fishery policy change? In preparation for a discussion on these questions, this paper aims to provide an overview on the Fisheries Act prior to this amendment[i].

THE HISTORY OF JAPAN’S FISHERY SYSTEM

Many of the regulations and rules in Japan’s fishing industry today are rooted in the feudal period. Thus, it is useful to have a brief review of the history of Japan’s fishing system before the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

In the feudal period, each fishing village had its own (and usually unwritten) rules about how to use marine resources. These rules include how to protect marine resources (e.g. setting no-fishing periods and/or areas) and how to allocate efforts and benefits from common fisheries (e.g. beach seine fishery). These rules evolved naturally on the basis of historical experiences and legends. In principle, it was not possible for just anyone out of the fishing village to engage in fishing[ii]. This system was called Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido, and represented the villagers’ exclusive usage right over marine resources as vested by the feudal lords.

In the Meiji Restoration, the Meiji government considered that the evil practices of the feudal system should be eradicated. Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was listed as one for such eradication. In 1874, the Meiji government launched a plan for a new framework for its fishery policy, called Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido, a leasehold system with respect to the sea surface between the government and the fishermen. In Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido, the Meiji government was to acquire the ownership of the water surface, and the fishermen would receive permission to fish by paying rent to the Meiji government. Under this plan, the Meiji government denied Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido. However, the Meiji government failed to implement an adequate surveillance system for fishing activities under Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido. As a result, undesirable water usage, such as illegal fishing and overfishing, became rampant after the announcement of Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido. Thus, the Meiji government realized the effectiveness of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido and the unworkableness of Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido.

In 1875, the Meiji government announced that Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido would be canceled and that fishermen should observe Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido as they had previously. However, Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido did not fall under the format of modern law. Since the Meiji government raised the slogan of “Quit Asia and Join Europe,” it wanted to formalize Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido within the construct of modern law. This proved to be a difficult undertaking because the rules and regulations under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido differed by fishing village and a large portion of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was ambiguously defined. In addition, there were conflicts among interested parties regarding who should assume the leadership of the fishery industry[iii].

After a great deal of argument among politicians, bureaucrats, and fishermen’s groups, the Fisheries Act was finally established in 1903 (in order to distinguish the Fisheries Act in the post-Pacific War period, this paper hereafter refers to the Fisheries Act in the pre-Pacific War period as the “Old Fisheries Act”). This can be seen as the completion of the legal framework for the fishery industry in the pre-Pacific War period. The Old Fisheries Act stipulated that each fishing village should have its own fishermen’s union to organize common fishing among all the fishermen in the village. In fact, the fishermen’s unions adopted most of the rules of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido.

After the Meiji Restoration, due to the inflow of modern technologies from European and North American countries, new types of fishery technologies that did not exist under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido emerged. Fixed-net fishery and demarcated fishery were such examples. While the new fishery technologies offered a higher level of efficiency in catching fish, they increased the risk of overfishing. In addition, conflicts arose between those who wanted to continue conventional types of fishing under Isson Senyu Gyojo Seido and those who wanted to introduce new technologies. Aiming to solve these problems, the Meiji government introduced licensing systems for the newly-developed fishery technologies, namely, the fixed-net fishery license system, the demarcated fishery license system for aquaculture, and the special fishing right system for other types of new fishery technologies. Each applicant needed to specify a water location(s) and a type(s) of fishery. The term of the license was, in principle, twenty years. However, once the license was issued, the licensee was allowed to have his or her license renewed without limitation as long as he or she showed the will and ability to continue the licensed activity.

Various types of economic entities such as fishermen’s unions, private companies, and individual citizens applied for the licenses, but the government’s process of screening was not transparent. However, previous studies have identified a tendency for larger companies with greater financial resources to receive favorable treatment in the screening process[iv]. This reflected the fact that the initial costs for the new types of fishing were much greater than those of the older ways and that the propertied classes played a dominant role in Japanese politics in the pre-Pacific War period.

Following the 1930s, Japan gradually shifted to a military society, and this affected Japan’s fishery policy. In 1943, as a part of Japan’s militarization policy, fishermen’s unions were reformed into fishery associations, which controlled fishermen’s daily lives beyond fishing activities. Each fishing village had its own fishery association in which all of the fishermen in the village were legally required to participate. All fishery associations in Japan were subordinate to the National Fishery Association, which was controlled by the military government.

FISHERY POLICY REFORM IN THE EARLY-POST PACIFIC WAR PERIOD

From 1945 to 1952, Japan was democratized under the leadership of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ). In 1948, as a part of GHQ’s democratization policy, fishery associations were replaced by new organizations, called fishermen’s cooperatives[v]. Unlike in the case of fishery associations, fishermen were not legally required to participate in fishermen’s cooperatives. However, as will be discussed below, some types of fishery were available only for members of fishermen’s cooperatives.

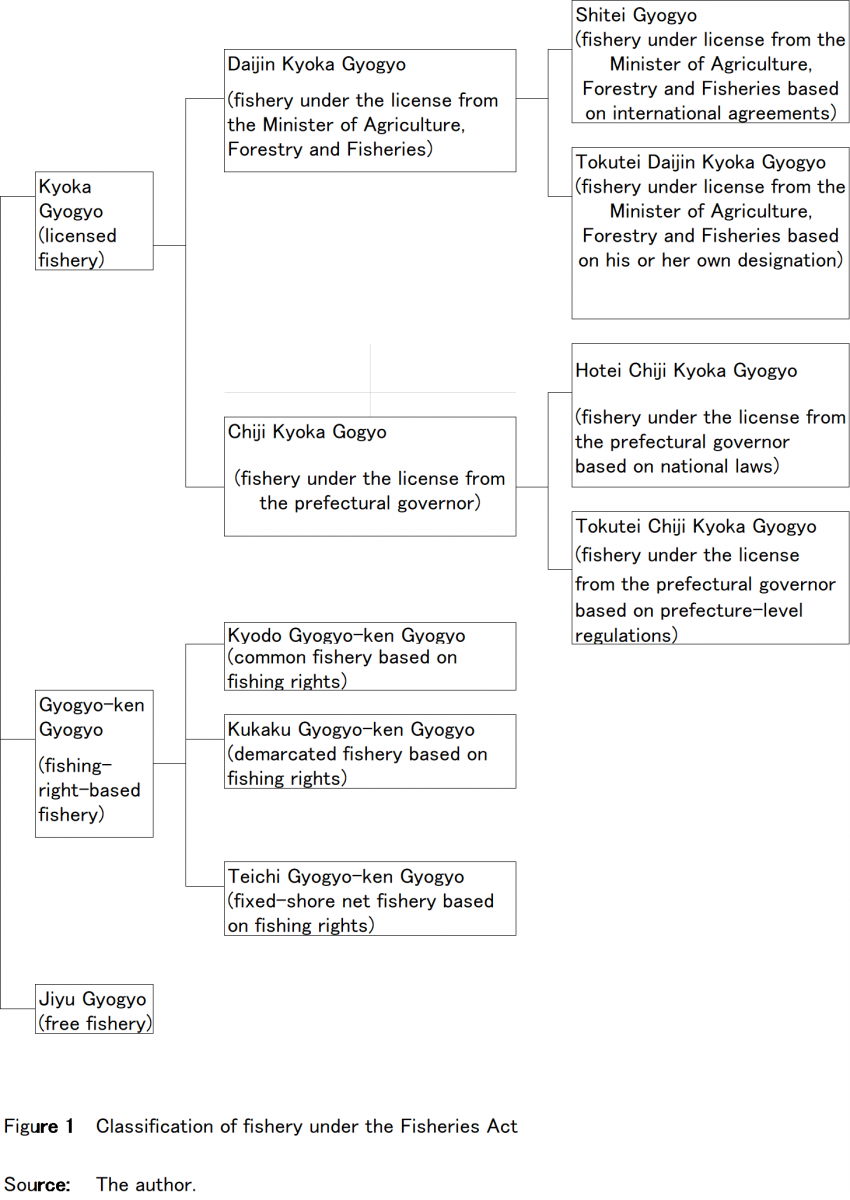

As the centerpiece of GHQ’s reform on Japan’s fishery policy, the Fisheries Act was established in 1949, and the Old Fisheries Act was abolished. As shown in Figure 1, the Fisheries Act established three administrative categories of fishery types: Kyoka Gyogyo (“licensed fishery”), Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo (“fishing-right-based fishery”) and Jiyu Gyogyo (“free fishery”).

Kyoka Gyogyo is applied to types of fishing that are so effective in catching fish that excessive competition can occur among fishermen if the technologies are used without regulations. In Kyoka Gyogyo, only those who receive the license from the authorities are allowed to engage in fishing activities. The licensing authority differs according to the type of fishery: Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo or Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo. Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo is under the auspices of the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo is under the prefectural governor.

Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo is applied to the types of fishing that the Japanese government is required to control as a result of international negotiations on marine resources in international waters. There are two types of Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo: Shitei Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries based on the international agreements”) and Tokutei Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries based on his or her own designation”). In the former, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries first sets the national quotas on the total number and tonnage of ships. Then, it allocates the quotas among applicants who have sufficient fishing abilities. In the latter, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries issues the license to those who have appropriate fishing plans and ships without setting quotas at the national level.

There are two types of Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo: Hotei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the prefectural governor based on the national laws”) and Tokutei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the prefectural governor on based on the prefecture-level rules of regulation”). In Hotei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo, in order to protect marine resources at the national level, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries determines each prefecture’s quotas based on the total number and tonnage of ships. Then, the governor allocates the quotas to owners and ships in his or her territorial waters. In Tokutei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo, the prefecture governor has the authority to introduce license systems for certain types of fishing methods to protect marine resources in his or her territorial waters based on his or her own judgement. Tokutei Kyoka Chiji Gyogyo covers many types of fishing methods, and the list and contents differ according to prefecture.

Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo is Japan’s unique system for coastal fisheries whereby members of fishermen’s cooperatives are favorably treated in obtaining fishing rights. There are three types of Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo: Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for small-scale fixed-shore net fishery and types of fishing that were done under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido in the pre-Pacific War period, Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for demarcated fishery, and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for large-scale shore net fishery.

For Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, only members of fishermen’s cooperatives were allowed to engage in fishing as organized under the cooperatives. This means that Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo can be seen as a reformed version of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido. For Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, any economic entities (whether natural or legal persons) who want to engage in demarcated fishery and large-size shore net fishery should apply to the prefectural governor for the right to fish. If multiple applicants want to engage in the same fishing type in the same location, the Fisheries Act stipulates the following priority order regarding to whom the right should be granted.

The first (the highest) priority: fishermen’s cooperative in the fishing village.

The second priority: legal entity formed by more than 70% of individual fishermen in the fishing village.

The third priority: legal or natural person who has been engaged in fishing in the fishing village or elsewhere.

The fourth (and the lowest) priority: others.

As discussed previously, in the pre-war Japanese licensing systems for demarcated fishery and fixed shore net fishery, wealthy classes who lived in urban areas tended to receive more favorable treatment in the government’s screening of applicants. GHQ considered such treatment to be undemocratic. This was the reason for listing the fishermen’s cooperatives at the top of the priority order.

The term of the fishing rights granted under Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo is ten or five years. However, as long as those who hold the rights demonstrate their ability and will to continue engaging in fishery, their rights will be renewed.

Jiyu Gyogyo refers to all types of fishing that are not included in the lists under Kyoka Gyogyo and Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo. Anyone is allowed to engage in Jiyu Gyogyo freely. Pole-and-line fishing for sea bream an example of a Jiyu Gyogyo activity.

SEA-AREA FISHERIES ADJUSTMENT COMMITTEES

The Fisheries Act also stipulates the establishment of new administrative committees for the Japanese government’s fishery policy, called Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees (SFACs) and the Wide Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees (WSFACs).

Before providing further information on SFACs and WSFACs, it would be useful to quickly review the relationship between Japan’s sea-area system and local governance. Japan has 66 marine zones as the basic unit of fishery. Each marine zone belongs to one of the 47 prefectures (Hokkaido has ten; Nagasaki has four; Fukushima and Kagoshima have three marine zones, respectively; Aomori, Ibaragi, Tokyo, Niigata, Hyogo, Shimane, Yamaguchi, Sag, and Kumamoto each have two marine zones; and the remaining 33 prefectures each have only one marine zone).

The Fisheries Act requires the prefectural governors to establish an SFAC for each marine zone[i]. Each SFAC consists of 15 members: nine are elected among fishermen and the remaining six are appointed by the governor (four are academics, and the remaining two are representatives of the public interest). The governor is required to obtain the approval of the corresponding SFAC when he or she wants to make an important decision, such as issuing the abovementioned fishing rights in a sea marine zone within his or her constituency.

The 66 marine zones are grouped into three wide-sea areas: Pacific Ocean Wide Sea-area, Sea-of-Japan/Kyushu West Wide Sea-area, and Seto Inland Sea Wide Sea-area. Each wide-sea area has its own WSFAC. A WSFAC consists of representatives of the corresponding marine zones, representatives of the fishermen, and academics. The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries is required to obtain the approval of the corresponding WFAC when he or she wants to make an important decision, such as establishing the abovementioned Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo.

The establishment of SFACs and WFACs reflected GHQ’s belief that the introduction of democratic administrative committees was necessary to democratize Japan’s fishing policy.

CRITIQUES ON THE FISHERIES ACT

Nearly 70 years have passed since the establishment of the Fisheries Act. While it appears to be true that the Fisheries Act contributed to the democratization of the Japanese society, which was at the top of GHQ’s political agenda, the Fisheries Act has become out of date in two ways. First, the Fisheries Act has not been effective in the protection of marine resources. In the feudal period, Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was successful in protecting marine resources, but after the Pacific War, new technologies were developed, whereby a large amount of fish was able to be captured in one swoop. While the authorities set a ceiling on the tonnage and number of ships for each type of Kyoka Gyogyo, it was unable to control the maximum efforts employed in catching fish[ii]. As a result, various marine resources, such as herring in the marine zones of Hokkaido sailfin fish in the marine zone of Akita, are in danger.

Second, fishermen’s cooperatives are treated so favorably under the Fisheries Act that new entry to the fishery industry for outsiders has been discouraged. Previously, the transmission of fishing skills from father to son was popular in fishing villages. Therefore, membership in the fishermen’s cooperative was also transferred from father to son. However, given the changing work ethic among Japanese laborers, younger generations have begun to move away from manual work, including fishing. In addition, due to the falling birthrate and changing lifestyles in Japanese families, the younger generations have become less interested in continuing their family businesses. As a result, many of the fishermen’s cooperatives have been suffering from population aging and a shortage of successors. Accordingly, they have become less productive than they had previously been. One possible solution to this problem is to encourage outsiders to participate in the fishing industry. However, because the Fisheries Act prioritizes fishermen’s cooperatives for fishing rights, the government has faced increasing pressure to update the regulations in order to make it easier for outsiders to enter the fishing industry. Thus, the government embarked on a large-scale revision of the Fisheries Act in 2018.

REFERENCES

Komatsu, Masayoshi, and Makoto Arizono, Gyogyoho to Gyogyoken no Kadai (Problems of the Fisheries Act and Fishing Rights), Seizando, 2017.

Kase, Kazutoshi, San Jikan de Wakaru Gyogyoken (A Three-hour Lecture on the Fishing Right System), Tsukuba Shobo, 2014.

Katano, Ayumu and Isao Sakaguchi (2019) Bippon no Suisan Shigen Kanri (Japan’s Marine Resource Management Policy), Keio University Press.

[i] There are two types in fishery according to water area: i.e.: marine fishery and inland water fishery. The legal framework differs between the two types. This paper discusses only marine fishery, which is dominant in Japan.

[ii] There were some exceptions. For example, for some types of fishing, neighboring villagers worked together in the same water area.

[iii] Komatsu and Arizono (2017) describe how the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Home Affairs had serious arguments on how to manage taxation and control over fishermen.

[iv] For example, see Kase (2014).

[v] There are two types in fishermen’s cooperatives: region-based fishermen’s cooperatives and fishing-type-based cooperatives. The function and treatment in the government’s fishery policy differ between the two. Fishing-type-based cooperatives represent only a limited share of the total number of cooperatives (according to the Cabinet Office, there were 960 region-based fishermen’s cooperatives and 95 fishing-type-based cooperatives as of March 2017). This paper discusses only region-based cooperatives.

[vi] If necessary, the governors in neighboring prefectures use additional administrative committees, called United Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees, to discuss marine-use problems within the neighboring marine zones.

[vii] For example, see Katano and Sakagichi (2019)

Japan’s Fisheries Act

ABSTRACT

The Fisheries Act stipulates the basic framework of Japan’s fishery policy. According to the types of rules and regulations on fishing activities, the Fisheries Act has three categories for types of fishing: Kyoka Gyogyo (“licensed fishery”); Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo (“fishing-right-based fishery”); and Jiyu Gyogyo (“free fishery”). This paper aims to describe the rules and regulations on these three types of fisheries.

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s fishery policy is in the midst of the biggest reform of the post-Pacific War period. In November 2018, the Japanese government submitted a bill to the Diet for a large-scale amendment to the Fisheries Act, which has served as the framework for the current Japanese fishery policy since its establishment in 1949. The bill passed in December 2018, and the enactment of the amended Fisheries Act is scheduled for December 2020.

What is the purpose of this reform? How will Japan’s fishery policy change? In preparation for a discussion on these questions, this paper aims to provide an overview on the Fisheries Act prior to this amendment[i].

THE HISTORY OF JAPAN’S FISHERY SYSTEM

Many of the regulations and rules in Japan’s fishing industry today are rooted in the feudal period. Thus, it is useful to have a brief review of the history of Japan’s fishing system before the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

In the feudal period, each fishing village had its own (and usually unwritten) rules about how to use marine resources. These rules include how to protect marine resources (e.g. setting no-fishing periods and/or areas) and how to allocate efforts and benefits from common fisheries (e.g. beach seine fishery). These rules evolved naturally on the basis of historical experiences and legends. In principle, it was not possible for just anyone out of the fishing village to engage in fishing[ii]. This system was called Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido, and represented the villagers’ exclusive usage right over marine resources as vested by the feudal lords.

In the Meiji Restoration, the Meiji government considered that the evil practices of the feudal system should be eradicated. Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was listed as one for such eradication. In 1874, the Meiji government launched a plan for a new framework for its fishery policy, called Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido, a leasehold system with respect to the sea surface between the government and the fishermen. In Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido, the Meiji government was to acquire the ownership of the water surface, and the fishermen would receive permission to fish by paying rent to the Meiji government. Under this plan, the Meiji government denied Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido. However, the Meiji government failed to implement an adequate surveillance system for fishing activities under Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido. As a result, undesirable water usage, such as illegal fishing and overfishing, became rampant after the announcement of Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido. Thus, the Meiji government realized the effectiveness of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido and the unworkableness of Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido.

In 1875, the Meiji government announced that Kaimen Kan-yu Shakku Seido would be canceled and that fishermen should observe Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido as they had previously. However, Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido did not fall under the format of modern law. Since the Meiji government raised the slogan of “Quit Asia and Join Europe,” it wanted to formalize Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido within the construct of modern law. This proved to be a difficult undertaking because the rules and regulations under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido differed by fishing village and a large portion of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was ambiguously defined. In addition, there were conflicts among interested parties regarding who should assume the leadership of the fishery industry[iii].

After a great deal of argument among politicians, bureaucrats, and fishermen’s groups, the Fisheries Act was finally established in 1903 (in order to distinguish the Fisheries Act in the post-Pacific War period, this paper hereafter refers to the Fisheries Act in the pre-Pacific War period as the “Old Fisheries Act”). This can be seen as the completion of the legal framework for the fishery industry in the pre-Pacific War period. The Old Fisheries Act stipulated that each fishing village should have its own fishermen’s union to organize common fishing among all the fishermen in the village. In fact, the fishermen’s unions adopted most of the rules of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido.

After the Meiji Restoration, due to the inflow of modern technologies from European and North American countries, new types of fishery technologies that did not exist under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido emerged. Fixed-net fishery and demarcated fishery were such examples. While the new fishery technologies offered a higher level of efficiency in catching fish, they increased the risk of overfishing. In addition, conflicts arose between those who wanted to continue conventional types of fishing under Isson Senyu Gyojo Seido and those who wanted to introduce new technologies. Aiming to solve these problems, the Meiji government introduced licensing systems for the newly-developed fishery technologies, namely, the fixed-net fishery license system, the demarcated fishery license system for aquaculture, and the special fishing right system for other types of new fishery technologies. Each applicant needed to specify a water location(s) and a type(s) of fishery. The term of the license was, in principle, twenty years. However, once the license was issued, the licensee was allowed to have his or her license renewed without limitation as long as he or she showed the will and ability to continue the licensed activity.

Various types of economic entities such as fishermen’s unions, private companies, and individual citizens applied for the licenses, but the government’s process of screening was not transparent. However, previous studies have identified a tendency for larger companies with greater financial resources to receive favorable treatment in the screening process[iv]. This reflected the fact that the initial costs for the new types of fishing were much greater than those of the older ways and that the propertied classes played a dominant role in Japanese politics in the pre-Pacific War period.

Following the 1930s, Japan gradually shifted to a military society, and this affected Japan’s fishery policy. In 1943, as a part of Japan’s militarization policy, fishermen’s unions were reformed into fishery associations, which controlled fishermen’s daily lives beyond fishing activities. Each fishing village had its own fishery association in which all of the fishermen in the village were legally required to participate. All fishery associations in Japan were subordinate to the National Fishery Association, which was controlled by the military government.

FISHERY POLICY REFORM IN THE EARLY-POST PACIFIC WAR PERIOD

From 1945 to 1952, Japan was democratized under the leadership of the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces (GHQ). In 1948, as a part of GHQ’s democratization policy, fishery associations were replaced by new organizations, called fishermen’s cooperatives[v]. Unlike in the case of fishery associations, fishermen were not legally required to participate in fishermen’s cooperatives. However, as will be discussed below, some types of fishery were available only for members of fishermen’s cooperatives.

As the centerpiece of GHQ’s reform on Japan’s fishery policy, the Fisheries Act was established in 1949, and the Old Fisheries Act was abolished. As shown in Figure 1, the Fisheries Act established three administrative categories of fishery types: Kyoka Gyogyo (“licensed fishery”), Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo (“fishing-right-based fishery”) and Jiyu Gyogyo (“free fishery”).

Kyoka Gyogyo is applied to types of fishing that are so effective in catching fish that excessive competition can occur among fishermen if the technologies are used without regulations. In Kyoka Gyogyo, only those who receive the license from the authorities are allowed to engage in fishing activities. The licensing authority differs according to the type of fishery: Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo or Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo. Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo is under the auspices of the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo is under the prefectural governor.

Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo is applied to the types of fishing that the Japanese government is required to control as a result of international negotiations on marine resources in international waters. There are two types of Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo: Shitei Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries based on the international agreements”) and Tokutei Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries based on his or her own designation”). In the former, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries first sets the national quotas on the total number and tonnage of ships. Then, it allocates the quotas among applicants who have sufficient fishing abilities. In the latter, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries issues the license to those who have appropriate fishing plans and ships without setting quotas at the national level.

There are two types of Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo: Hotei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the prefectural governor based on the national laws”) and Tokutei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo (“fishery under the license from the prefectural governor on based on the prefecture-level rules of regulation”). In Hotei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo, in order to protect marine resources at the national level, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries determines each prefecture’s quotas based on the total number and tonnage of ships. Then, the governor allocates the quotas to owners and ships in his or her territorial waters. In Tokutei Chiji Kyoka Gyogyo, the prefecture governor has the authority to introduce license systems for certain types of fishing methods to protect marine resources in his or her territorial waters based on his or her own judgement. Tokutei Kyoka Chiji Gyogyo covers many types of fishing methods, and the list and contents differ according to prefecture.

Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo is Japan’s unique system for coastal fisheries whereby members of fishermen’s cooperatives are favorably treated in obtaining fishing rights. There are three types of Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo: Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for small-scale fixed-shore net fishery and types of fishing that were done under Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido in the pre-Pacific War period, Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for demarcated fishery, and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo for large-scale shore net fishery.

For Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, only members of fishermen’s cooperatives were allowed to engage in fishing as organized under the cooperatives. This means that Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo can be seen as a reformed version of Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido. For Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, any economic entities (whether natural or legal persons) who want to engage in demarcated fishery and large-size shore net fishery should apply to the prefectural governor for the right to fish. If multiple applicants want to engage in the same fishing type in the same location, the Fisheries Act stipulates the following priority order regarding to whom the right should be granted.

The first (the highest) priority: fishermen’s cooperative in the fishing village.

The second priority: legal entity formed by more than 70% of individual fishermen in the fishing village.

The third priority: legal or natural person who has been engaged in fishing in the fishing village or elsewhere.

The fourth (and the lowest) priority: others.

As discussed previously, in the pre-war Japanese licensing systems for demarcated fishery and fixed shore net fishery, wealthy classes who lived in urban areas tended to receive more favorable treatment in the government’s screening of applicants. GHQ considered such treatment to be undemocratic. This was the reason for listing the fishermen’s cooperatives at the top of the priority order.

The term of the fishing rights granted under Kyodo Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, Kukaku Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo, and Teichi Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo is ten or five years. However, as long as those who hold the rights demonstrate their ability and will to continue engaging in fishery, their rights will be renewed.

Jiyu Gyogyo refers to all types of fishing that are not included in the lists under Kyoka Gyogyo and Gyogyo-ken Gyogyo. Anyone is allowed to engage in Jiyu Gyogyo freely. Pole-and-line fishing for sea bream an example of a Jiyu Gyogyo activity.

SEA-AREA FISHERIES ADJUSTMENT COMMITTEES

The Fisheries Act also stipulates the establishment of new administrative committees for the Japanese government’s fishery policy, called Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees (SFACs) and the Wide Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees (WSFACs).

Before providing further information on SFACs and WSFACs, it would be useful to quickly review the relationship between Japan’s sea-area system and local governance. Japan has 66 marine zones as the basic unit of fishery. Each marine zone belongs to one of the 47 prefectures (Hokkaido has ten; Nagasaki has four; Fukushima and Kagoshima have three marine zones, respectively; Aomori, Ibaragi, Tokyo, Niigata, Hyogo, Shimane, Yamaguchi, Sag, and Kumamoto each have two marine zones; and the remaining 33 prefectures each have only one marine zone).

The Fisheries Act requires the prefectural governors to establish an SFAC for each marine zone[i]. Each SFAC consists of 15 members: nine are elected among fishermen and the remaining six are appointed by the governor (four are academics, and the remaining two are representatives of the public interest). The governor is required to obtain the approval of the corresponding SFAC when he or she wants to make an important decision, such as issuing the abovementioned fishing rights in a sea marine zone within his or her constituency.

The 66 marine zones are grouped into three wide-sea areas: Pacific Ocean Wide Sea-area, Sea-of-Japan/Kyushu West Wide Sea-area, and Seto Inland Sea Wide Sea-area. Each wide-sea area has its own WSFAC. A WSFAC consists of representatives of the corresponding marine zones, representatives of the fishermen, and academics. The Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries is required to obtain the approval of the corresponding WFAC when he or she wants to make an important decision, such as establishing the abovementioned Daijin Kyoka Gyogyo.

The establishment of SFACs and WFACs reflected GHQ’s belief that the introduction of democratic administrative committees was necessary to democratize Japan’s fishing policy.

CRITIQUES ON THE FISHERIES ACT

Nearly 70 years have passed since the establishment of the Fisheries Act. While it appears to be true that the Fisheries Act contributed to the democratization of the Japanese society, which was at the top of GHQ’s political agenda, the Fisheries Act has become out of date in two ways. First, the Fisheries Act has not been effective in the protection of marine resources. In the feudal period, Isson Sen-yu Gyojo Seido was successful in protecting marine resources, but after the Pacific War, new technologies were developed, whereby a large amount of fish was able to be captured in one swoop. While the authorities set a ceiling on the tonnage and number of ships for each type of Kyoka Gyogyo, it was unable to control the maximum efforts employed in catching fish[ii]. As a result, various marine resources, such as herring in the marine zones of Hokkaido sailfin fish in the marine zone of Akita, are in danger.

Second, fishermen’s cooperatives are treated so favorably under the Fisheries Act that new entry to the fishery industry for outsiders has been discouraged. Previously, the transmission of fishing skills from father to son was popular in fishing villages. Therefore, membership in the fishermen’s cooperative was also transferred from father to son. However, given the changing work ethic among Japanese laborers, younger generations have begun to move away from manual work, including fishing. In addition, due to the falling birthrate and changing lifestyles in Japanese families, the younger generations have become less interested in continuing their family businesses. As a result, many of the fishermen’s cooperatives have been suffering from population aging and a shortage of successors. Accordingly, they have become less productive than they had previously been. One possible solution to this problem is to encourage outsiders to participate in the fishing industry. However, because the Fisheries Act prioritizes fishermen’s cooperatives for fishing rights, the government has faced increasing pressure to update the regulations in order to make it easier for outsiders to enter the fishing industry. Thus, the government embarked on a large-scale revision of the Fisheries Act in 2018.

REFERENCES

Komatsu, Masayoshi, and Makoto Arizono, Gyogyoho to Gyogyoken no Kadai (Problems of the Fisheries Act and Fishing Rights), Seizando, 2017.

Kase, Kazutoshi, San Jikan de Wakaru Gyogyoken (A Three-hour Lecture on the Fishing Right System), Tsukuba Shobo, 2014.

Katano, Ayumu and Isao Sakaguchi (2019) Bippon no Suisan Shigen Kanri (Japan’s Marine Resource Management Policy), Keio University Press.

[i] There are two types in fishery according to water area: i.e.: marine fishery and inland water fishery. The legal framework differs between the two types. This paper discusses only marine fishery, which is dominant in Japan.

[ii] There were some exceptions. For example, for some types of fishing, neighboring villagers worked together in the same water area.

[iii] Komatsu and Arizono (2017) describe how the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Home Affairs had serious arguments on how to manage taxation and control over fishermen.

[iv] For example, see Kase (2014).

[v] There are two types in fishermen’s cooperatives: region-based fishermen’s cooperatives and fishing-type-based cooperatives. The function and treatment in the government’s fishery policy differ between the two. Fishing-type-based cooperatives represent only a limited share of the total number of cooperatives (according to the Cabinet Office, there were 960 region-based fishermen’s cooperatives and 95 fishing-type-based cooperatives as of March 2017). This paper discusses only region-based cooperatives.

[vi] If necessary, the governors in neighboring prefectures use additional administrative committees, called United Sea-area Fisheries Adjustment Committees, to discuss marine-use problems within the neighboring marine zones.

[vii] For example, see Katano and Sakagichi (2019)