ABSTRACT

In Japan, heated debates take place on whether and how the country should accept unskilled foreign laborers. The Japanese government’s long-held principle that these laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan reflects citizens’ anxiety about the threat to job opportunities and disturbance of local communities' social order. However, so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces, such as construction sites and farms, suffer from serious labor shortages, which reflect the changing lifestyle, aging population, and work ethics of Japanese laborers. While unskilled foreign laborers are allowed to work in Japan under the name of “training,” if they satisfy certain conditions stipulated by the Japanese government, this “training” system is not effective in mitigating labor shortages in 3D workplaces. In addition, human rights organizations criticize the system for its ineffectiveness in protecting foreigners’ human rights. In 2018, the Japanese government made a drastic revision to its immigration policy by creating the new category of "Specified Skilled Worker" in the Status of Residence list. Contrary to what the name implies, this new status is given to unskilled foreign laborers; it has led to expectations as well as concerns among citizens. This study examines the government's motivation for the amendment and considers how it will affect the agricultural industry. It finds that, while it is still too early to evaluate the impacts of this new policy, there is a strong possibility that a large inflow of foreign laborers will bring structural change to the Japanese society. It is further expected that the agricultural labor market will change drastically under the new policy.

Keywords: human rights, immigration, implementing organization, Industrial Training Program, personnel placement agency, sending organization, Specified Skilled Worker, supervising organization, Technical Intern Training Program

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s immigration policy is at a turning point. For years, the government has held the principle that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan—a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that foreign laborers may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the community’s social order. However, the so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces suffer from labor shortages because Japanese citizens’ urbanized lifestyle leads them to avoid manual labor. Thus, the Japanese government faces the dilemma of relieving citizens’ anxiety about the negative aspects of foreign labor by imposing strict regulations on unskilled foreign laborers, while mitigating the labor shortage by accepting these laborers.

The Japanese government takes a calculated approach to this dilemma. In particular, it distinguishes between its official view and its actual policy. For example, the government allows foreigners to do physical labor in the name of "training" under a certain stipulated condition. However, this approach encounters serious criticism from human rights organizations, both inside and outside Japan. In addition, demands for foreign laborers at 3D workplaces are rapidly increasing, with increasing requests by business leaders for deregulation of the employment of foreign unskilled labor. Agriculture is one of the most typical industries that is suffering from a labor shortage and urging for deregulation of foreign labor.

On November 2, 2018, the Japanese government submitted a bill to amend the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRRA) to the national legislature (i.e., the Diet). The bill aimed to create a new category in the Status of Residence list for foreign laborers, namely, “Specified Skilled Worker (SSW)." Foreign residents are called specified skilled workers in this new category. In contrast to the category name, specified skilled workers should be seen as de facto unskilled laborers. Since this ICRRA amendment may invite a drastic increase in unskilled foreign laborers, the Diet was divided into those for and those against. After fierce arguments in the Diet, the bill was passed on November 27, 2018. The amended ICRRA became effective on April 1, 2019.

What is the government’s motivation for this amendment? What are specified skilled workers? How will the amendment of the SSW affect the agricultural industry? This paper aims to answer these questions.

Sections 2 and 3 review the history of Japan’s policy on foreign laborers until 2017. Section 4 explains the details of the SSW, while Section 5 discusses how the SSW affect Japan’s agricultural production. Section 6 concludes.

UNSKILLED FOREIGN LABORERS AS “TRAINEES”

For years, the Japanese government had been strict about observing the principle that Japan should not accept unskilled foreign laborers. However, when the Japanese economy extraordinarily boomed around 1990, the labor market became abnormally constrained. In particular, small and medium-sized factories, which are more labor-intensive and less able than large-sized factories to afford high wages, were seriously affected by the labor shortage. This pressured the government to compromise on its immigration policy principles.

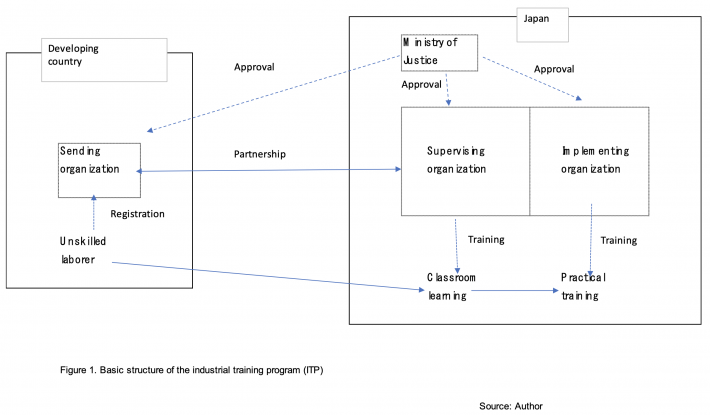

In 1989, in response to the pressure, the government created the Industrial Training Program (ITP) to accept unskilled foreign laborers (called "trainees") under the category of “training.” Figure 1 shows the basic structure of the ITP. Those who want to stay in Japan as a trainee needs to register as a regular member of a sending organization in his or her country. After entering Japan, the trainee attends classroom learning at a supervising organization, followed by practical training at an implementing organization. By registering itself as an implementing organization, a Japanese factory receives unskilled laborers as trainees. The duration for practical training should be less than two-thirds of the total ITP period.

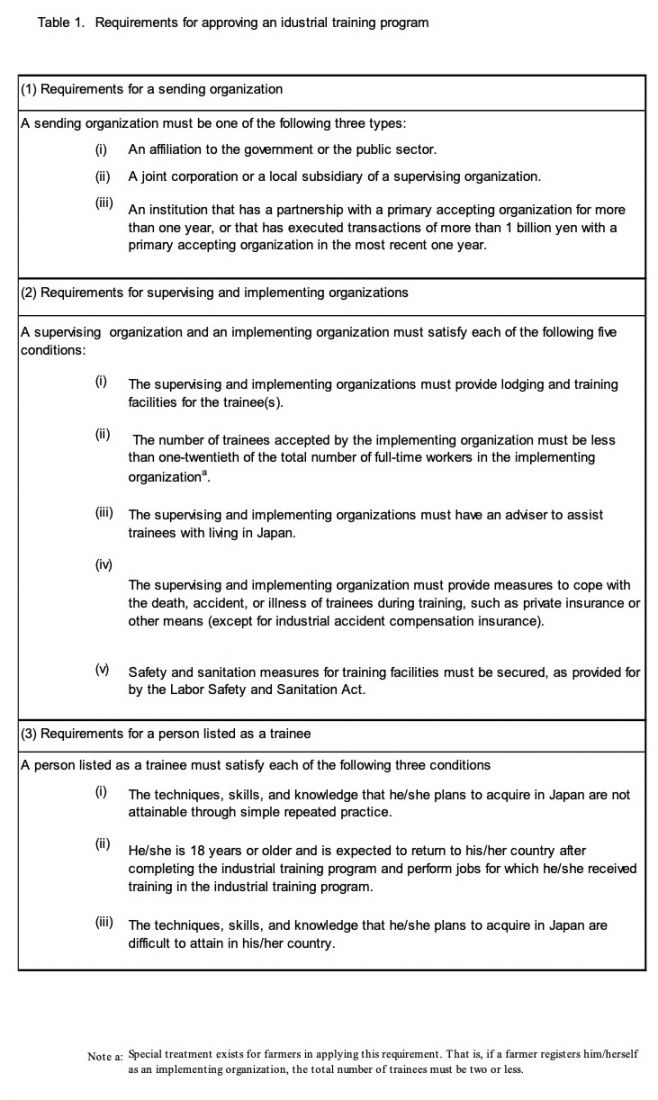

Table 1 lists the requirements for a sending organization, a supervising organization, an implementing organization, and a trainee. These requirements seem to present hurdles to the use of the ITP. Note that the requirements include some ambiguous content, and that there is room for arbitrary application. For example, the application of (3) in Table 1 depends on an observer’s viewpoint on whether a job is regarded as “simple repeated practice.” The ITP and the below-mentioned Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) have been used for their own benefit by implementing accepting organizations’ needs, which shows strong demand for cheap foreign laborers.

The Japanese government does not recognize a labor-management relationship (i.e., an employee-employer relationship) between a trainee and an implementing organization, because the nature of an ITP is “training.” Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work takes the form of “compensation” for the necessary expenses of his or her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Act is not applicable to ITP trainees. Oftentimes, trainees do not receive industrial insurance and their “compensation” money is less than the lowest payment stipulated by the Minimum Wages Act.

The length of stay for the ITP was limited to one year or less. However, trainees and implementing organizations often found that this was too short. Thus, in 1993, the Japanese government introduced a new framework called the TITP to allow trainees to stay longer than a year. Foreigners in the TITP are called “technical intern trainees.” A foreigner who wants to continue “training” for longer than one year should do so by upgrading his or her status from an ITP trainee to a TITP technical intern trainee.

Requirements for this upgrade can be summarized by the following three points[1]: (i) the trainee has already acquired technical skills that are equivalent to the Basic 2-Level of the National Technical Skill Test; (ii) the living conditions and working performance of the trainee are satisfactory; and (iii) the implementing organization that is responsible for the trainee’s ITP training has an appropriate plan for his or her TITP training.

It is not difficult to satisfy these requirements. Thus, whether a trainee will continue to receive training as a technical intern trainee for another two years, following completion of one year of training, normally follows an informal registration procedure with a sending organization (i.e., before he or she comes to Japan).

Unlike the case of an ITP trainee, the relationship between a technical intern trainee in the TITP and a Japanese company or farm is officially recognized as a labor-management relationship (i.e., an employee-employer relationship). The policy rationale of the Japanese government is that the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills through learning is the purpose of the ITP, while that of the TITP is the acquisition of practical skills through employment.

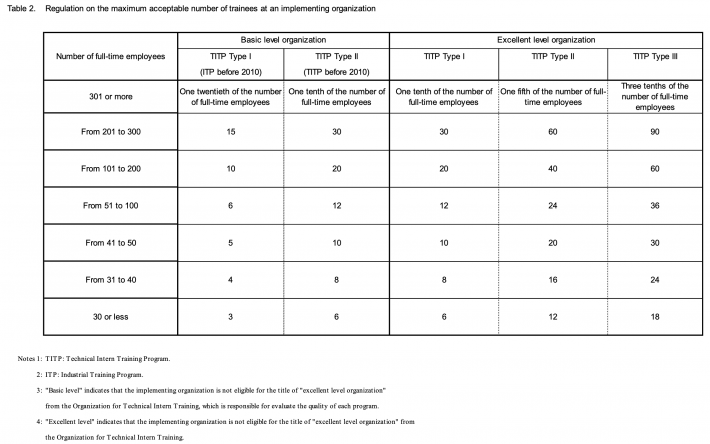

The maximum number of trainees or technical intern trainees in an implementing organization differs according to the size of the implementing organization (measured by the total number of full-time employees), as shown in Table 2.

Trainees and technical intern trainees have contributed to the Japanese society as indispensable laborers in 3D workplaces. However, because many of them are unfamiliar with the local lifestyle and are not fluent in the Japanese language, there are many cases of communication problems with local communities.

CRITICISM ON THE ITP AND TITP

The ITP and TITP receive ongoing harsh criticism for insufficiency in protecting foreigners’ human rights. In principle, foreigners in the ITP or TITP are not allowed to change their workplace after entering Japan[2]. Thus, if the Japanese authorities find any problem with a foreigner (even if only a manager of the implementing organization produces the problem), the ITP or TITP will be immediately canceled and he or she is forced to return to his or her country of origin. This means that he or she loses their earning opportunity in Japan. Thus, foreigners in the ITP and TITP tend not to complain, even if they are treated badly at implementing organizations[3].

To worsen the situation, a sending organization often collects a large amount of money as deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as a trainee or technical intern trainee. The deposit is withheld until the trainee successfully completes all the jobs in Japan. In that sense, a Japanese implementing organization is in a fiduciary position when managing a trainee or a technical intern trainee.

Human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan often criticized Japan for this policy. For them, the basic problem is the difference between the official explanation and the reality of foreigners’ situation: while the Japanese government insists that foreigners in the ITP and TITP are receiving training, they are de facto unskilled laborers.

For example, Jorge Bustamante, the U.N. special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, urged the Japanese government in April 2010 to terminate its industrial trainee and technical intern program for overseas workers, saying that it may amount to “slavery” in some cases, by fueling demand for exploitative cheap labor, in possible violation of human rights.

In response to these criticisms, the Japanese government revised the ITP and TITP frameworks in July 2010. The government expanded the TITP and divided it into Type 1 and Type 2. TITP Type 1 should be applied for the first year of "training" by foreign laborers (accordingly, they should be called technical intern trainees instead of trainees). TITP Type 2 should be applied for the second and third years of “training”.

By this revision, the Labor Standards Act is effective from the first year of foreign unskilled laborers’ stay in Japan. However, unskilled foreign laborers are still at a disadvantage because they are not allowed to change their workplaces if they wish to stay in Japan. The Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA) asserts that the replacement of the ITP by TITP Type 1 can be seen as a time-serving remedy to the critical feedback, which produces no significant changes for unskilled foreign workers’ position (JFBA, “Gaikokujin Gino Seido No Sokyu No Haishi Wo Motomeru Ikensho” (A Proposal to Abolish Technical Intern Training Program), June 2013).

In addition, implementing organizations identify problems in the ITP and TITP. They often present their complaints in the following four areas:

- Length of stay is too short. It would take a good few years before a trainee or a technical intern trainee could familiarize themselves with all the operations in a factory. In the ITP and TITP, the duration of stay for a foreign worker is limited to three years or less. A foreign worker may have to leave before adding value to the workplace.

- The ITP and TITP are inflexible in the types and places of operations. Before each ITP or TITP starts, a Japanese employer must submit the types and places of operations to an immigration officer. However, the types and places of operations sometimes change in practice according to changes in business conditions.

- The maximum number of trainees or technical intern trainees is too small.

- Classroom training would pose unnecessary costs for employers. While foreign unskilled workers are out of operation during the classroom training period, employers need to pay expenses for classroom training.

In 2017, the Japanese government revised the TITP. Aiming to improve the working conditions of technical intern trainees, the government established the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT). The OTIT is responsible for reviewing the performance of supervising and implementing organizations. If the OTIT recognizes that technical intern trainees’ working and living conditions are excellent, it allocates the title of "excellent level organizations" to the supervising and implementing organizations. These organizations are allowed to extend the maximum staying period of technical intern trainees from three to five years (the “training” in these additional two years are called TITP Type 3). In addition, as shown in Table 2, the maximum number of technical intern trainees in the supervising and implementing organizations has increased.

JAPAN’S NEW IMMIGRATION POLICY IN 2018

In 2018, the government made a historic decision on its immigration control policy. Specifically, by establishing a new category called SSW in the list of the Status of Residence, the government reduced its barriers to entry for unskilled foreign laborers.

Two SSW types exist, namely, SSW Type 1 and Type 2. The government nominated 14 industrial fields within which foreigners are allowed to apply for SSW Type 1: agriculture, caregiving, restaurant, construction, building cleaning, food processing, hotel, foundry, ship building, fishery, industrial machinery assembling, automobile maintenance, electronic device assembling, and aviation related services. Foreigners can obtain SSW Type 1 visa status in two ways. The first is automatic transition from TITP Type 2 or Type 3 on completion of the “training” period (this means that the skill level of SSW Type 1 is the same as that of TITP Type 2 or Type 3). The other is to take an examination whereby foreigners are tested on their Japanese language proficiency and working skills (the contents and levels differ according to the 14 fields).

Unlike technical intern trainees, specified skilled workers enter directly into employment contracts with employers and have the freedom of changing their places of work (as far as workplaces are in the designated industrial fields). Holders of SSW Type 1 visas are allowed to stay in Japan for up to 60 months (unlike the case of technical intern trainees, the status of SSW does not expire, even if the specified skilled workers return to their countries of origin).

SSW Type 1 visa holders are qualified to take a skills level examination for upgrading their status to SSW Type 2. SSW Type 1 and Type 2 differ in living conditions in the following two aspects. The first aspect is the staying period. Unlike that of SSW Type 1, the status of SSW Type 2 is renewable (there is no limitation on the number of renewal times)[4]. The second aspect is the treatment for family members of a specified skilled worker. While the SSW Type 2 visa holders are allowed to bring their family members to Japan, those of SSW Type 1 visas are not.

The Japanese government first announced its plan to establish SSW visas on July 5, 2018 in a draft of “Basic Policies for the Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform.” This announcement heralded government’s significant progress towards inviting foreigners as permanent laborers at 3D workplaces.

Mass media reported this announcement as a turning point in Japan’s immigration policy; it reflected the changing attitude of supporters for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which has been in power almost uninterruptedly since 1955[5]. Farmers and construction companies have been powerful supporters of the LDP. Previously, they tended to have a conservative (or negative) approach to foreigners. However, they are now showing strong demands for foreign laborers due to the serious labor shortage[6].

Citizens’ sentiment toward foreigners is also changing. As a result of aging population, elderly caregiving became one of the biggest concerns for the citizens, who are aware that care facilities are affected by labor shortage. This weakened the citizens’ resistance to accepting foreign workers.

Mass media pointed out that the LDP wanted to show their successes in increasing unskilled foreign laborers as part of a campaign for the unified local elections and the election of members of the House of Councilors, which would take place in April 2019 and July 2019, respectively[7].

While demands for unskilled foreign laborers in 3D workplaces continued to increase, conservative groups still fear that a mass inflow of foreign laborers may increase crimes and disturb the social order. In fact, when the government submitted a bill to amend the ICRRA so as to create SSW on November 2, 2018, the opposition parties strongly disagreed. In addition, when the bill was taken into deliberation in the Diet, the government was not ready to provide detailed information on the skill and language levels required by specified skilled workers. Moreover, serious mistakes were found in the document submitted by the government as a reference for discussion in the Diet. While opposition parties requested to postpone voting for the bill in the Diet, the LDP was pressed to implement the SSW category before the unified local election. As a result, the bill to amend the ICRRA was passed by the Diet in a majority vote on November 27, 2018. The amended ICRRA became effective on April 1, 2019.

On November 25, 2018, the government announced the following planned number of SSW Type 1 visas for the 2019 fiscal year (from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020): 7,300 for agriculture; 5,000 for caregiving; 5,000 for restaurants; 6,000 for construction; 7,000 for building cleaning; 6,800 for food processing; 1,050 for hotels; 4,300 for foundry; 1,700 for ship building; 800 for fisheries; 1,050 for industrial machinery assembling; 800 for automobile maintenance; 650 for electronic device assembling; and 100 for aviation related services. Simultaneously, the government announced that the total number of SSW Type 1 visa holders for the 2019 to 2023 fiscal years (from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2024) should be 345,150 or less.

Citizens hold two contrasting opinions on these numbers[8]. Some find them not sufficiently large to mitigate the labor shortage, while others present their concerns that these numbers are too large to retain social order in local Japanese communities.

While the SSW Type 2 visa was initiated on April 1, 2019, the Japanese government has not issued this visa to any foreigners, because it has not designated any fields for the visa type. Accordingly, the required examination level for converting the SSW Type 1 visa to Type 2 is still unclear.

It is too early to evaluate the impacts of the establishment of the SSW visas. However, it is certain that the new status will create significant change in the Japanese labor market.

THE NEW POLICIES ON JAPANESE AGRICULTURE

Two types of agriculture exist, based on the degree of seasonal fluctuation in workload: small fluctuations in areas such as dairy and greenhouse farming, and large fluctuations in areas such as outdoor crop farming. For the former type, most of the technical intern trainees remain at the same farm for at least three years by upgrading their status from TITP Type 1 to Type 2 (and Type 3 later, if the conditions are satisfied). In this case, they are allowed to stay for another five years by converting their status from TITP Type 2 (or Type 3) to SSW Type 1 when they complete TITP Type 2 (or Type 3). Thus, the establishment of the SSW Type 1 visa will enable unskilled foreign laborers to work longer in farming[9].

For the latter types of agriculture, such as outdoor crop farming, technical intern trainees are employed for less than one year. Thus, most technical intern trainees return to their countries of origin without upgrading their status from TITP Type 1 to TITP Type 2. Since those who returned to their countries of origin after completing TITP (i.e., Type 1, Type 2, or Type 3) are not allowed to be granted TITP again, farmers must recruit new intern trainees every year. This burden makes the TITP less profitable for outdoor crop farming.

It should be noted that TITP’s major purpose at its establishment in 1993 was to mitigate labor shortages in factories, where there are little seasonal workload fluctuations. Thus, it is natural that the TITP design does not closely fit other workplaces such as outdoor crop farming.

In contrast, the government paid due attention to outdoor crop farming in designing the SSW Type 1 visa. While the government requires direct labor contracts between Japanese employers and specified skilled workers, it excluded agriculture from this requirement: specified skilled farm workers are allowed to enter into a labor contract with a personnel placement agency. The busy season for outdoor crop farming differs by region. Thus, a personnel placement agency can arrange different farms according to season for each specified skilled worker[10].

Currently, personnel placement agencies are not popular in recruiting Japanese agricultural laborers for outdoor crop farming. This is probably because Japanese laborers tend to live in the same workplace throughout a year. However, foreign unskilled laborers may be more flexible in changing places of living during their stay in Japan. Moreover, since specified skilled workers are allowed to repetitively leave and re-enter Japan, they can only work at the same farms during busy times. As such, the SSW Type 1 visas may bring structural changes to Japan’s agricultural labor market.

The government is negative in including agriculture in the list of SSW Type 2 visas[11].

CONCLUSION

The mitigation of the labor shortage in 3D workplaces is high on the Japanese government’s agenda. For years, Japan has been known as one of the most conservative countries to accept unskilled laborers from developing countries. However, it now seems timely for Japan to fully revise its immigration policy. The establishment of the SSW category in 2018 can be seen as the first movement toward such a revision.

It is too early to evaluate the Japanese government's new immigration policy. However, it is possible that a large inflow of foreigners will drastically reform 3D workplaces, with particularly large impacts in the agricultural industry.

|

Date submitted: October 14, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: November 22, 2019

|

[1] For caregiving, the requirements of upgrading TITP Type 1 to Type 2 are different from those for other sectors. The details are given in: Godo, Y., and T. W. Lim, “Foreign Nationals as Care Workers in Japan,” EAI Background Brief (National University of Singapore) No. 1398, 2018.

[2] If a trainee proves that there is no fault on his or her side, and that he or she can find another implementing organization that provides sufficient “training” to him or her, he or she is allowed to change his or her workplace. However, these conditions are so prohibitive that the workplace is almost unchangeable for trainees.

[3] “Hensai Dakede wa Kaerenai Gino Jisshusei (Technical Intern Trainees are Required more than Repayment),” AERA 134, September 26, 2018.

[4] The term of validity for the status of SSW Type 2 is between one and three years (it depends on various conditions).

[5] The LDP was not in power for two periods: the first was from August 1993 to May 1994, and the second was from September 2009 to December 2012

[6] “Hoshusho no Kabe Kuzusu Hitode Busoku (Labor Shortage Breaks Down the Wall of the Conservatives),” The Nikkei, June 2, 2018.

[7] “Jinzai Kaikoku Seisaku Tenkan Towareru Kakugo (Japan’s Decision of Calling in Laborers)," The Nikkei, June 2, 2018

[8] “Tokutei Ginou Kitai to Kenen (Expectations and Concerns for Specified Skilled Workers),” The Nikkei, December 15, 2018

[9] The Japanese government announced the basic plan for implementing a new immigration policy on December 25, 2018. There, 90 percent of specified skilled workers should be those who have completed the TITP.

[10] Specified skilled workers in fisheries, whose labor demands also fluctuate largely according to season, are allowed to enter into a labor contract with a personnel placement agency.

[11] On November 5, 2018, at the Standing Committee on Budget at the House of Councilors, Takamori Yoshikawa, the then-Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries indicated that agriculture would not be on the list of SSW Type 2 visas.

Japan’s New Policy on Foreign Laborers and its Impact on the Agricultural Industry

ABSTRACT

In Japan, heated debates take place on whether and how the country should accept unskilled foreign laborers. The Japanese government’s long-held principle that these laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan reflects citizens’ anxiety about the threat to job opportunities and disturbance of local communities' social order. However, so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces, such as construction sites and farms, suffer from serious labor shortages, which reflect the changing lifestyle, aging population, and work ethics of Japanese laborers. While unskilled foreign laborers are allowed to work in Japan under the name of “training,” if they satisfy certain conditions stipulated by the Japanese government, this “training” system is not effective in mitigating labor shortages in 3D workplaces. In addition, human rights organizations criticize the system for its ineffectiveness in protecting foreigners’ human rights. In 2018, the Japanese government made a drastic revision to its immigration policy by creating the new category of "Specified Skilled Worker" in the Status of Residence list. Contrary to what the name implies, this new status is given to unskilled foreign laborers; it has led to expectations as well as concerns among citizens. This study examines the government's motivation for the amendment and considers how it will affect the agricultural industry. It finds that, while it is still too early to evaluate the impacts of this new policy, there is a strong possibility that a large inflow of foreign laborers will bring structural change to the Japanese society. It is further expected that the agricultural labor market will change drastically under the new policy.

Keywords: human rights, immigration, implementing organization, Industrial Training Program, personnel placement agency, sending organization, Specified Skilled Worker, supervising organization, Technical Intern Training Program

INTRODUCTION

Japan’s immigration policy is at a turning point. For years, the government has held the principle that unskilled foreign laborers should not be allowed to work in Japan—a principle that reflects Japanese citizens’ anxiety that foreign laborers may deprive local workers of job opportunities and disturb the community’s social order. However, the so-called 3D (dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) workplaces suffer from labor shortages because Japanese citizens’ urbanized lifestyle leads them to avoid manual labor. Thus, the Japanese government faces the dilemma of relieving citizens’ anxiety about the negative aspects of foreign labor by imposing strict regulations on unskilled foreign laborers, while mitigating the labor shortage by accepting these laborers.

The Japanese government takes a calculated approach to this dilemma. In particular, it distinguishes between its official view and its actual policy. For example, the government allows foreigners to do physical labor in the name of "training" under a certain stipulated condition. However, this approach encounters serious criticism from human rights organizations, both inside and outside Japan. In addition, demands for foreign laborers at 3D workplaces are rapidly increasing, with increasing requests by business leaders for deregulation of the employment of foreign unskilled labor. Agriculture is one of the most typical industries that is suffering from a labor shortage and urging for deregulation of foreign labor.

On November 2, 2018, the Japanese government submitted a bill to amend the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRRA) to the national legislature (i.e., the Diet). The bill aimed to create a new category in the Status of Residence list for foreign laborers, namely, “Specified Skilled Worker (SSW)." Foreign residents are called specified skilled workers in this new category. In contrast to the category name, specified skilled workers should be seen as de facto unskilled laborers. Since this ICRRA amendment may invite a drastic increase in unskilled foreign laborers, the Diet was divided into those for and those against. After fierce arguments in the Diet, the bill was passed on November 27, 2018. The amended ICRRA became effective on April 1, 2019.

What is the government’s motivation for this amendment? What are specified skilled workers? How will the amendment of the SSW affect the agricultural industry? This paper aims to answer these questions.

Sections 2 and 3 review the history of Japan’s policy on foreign laborers until 2017. Section 4 explains the details of the SSW, while Section 5 discusses how the SSW affect Japan’s agricultural production. Section 6 concludes.

UNSKILLED FOREIGN LABORERS AS “TRAINEES”

For years, the Japanese government had been strict about observing the principle that Japan should not accept unskilled foreign laborers. However, when the Japanese economy extraordinarily boomed around 1990, the labor market became abnormally constrained. In particular, small and medium-sized factories, which are more labor-intensive and less able than large-sized factories to afford high wages, were seriously affected by the labor shortage. This pressured the government to compromise on its immigration policy principles.

In 1989, in response to the pressure, the government created the Industrial Training Program (ITP) to accept unskilled foreign laborers (called "trainees") under the category of “training.” Figure 1 shows the basic structure of the ITP. Those who want to stay in Japan as a trainee needs to register as a regular member of a sending organization in his or her country. After entering Japan, the trainee attends classroom learning at a supervising organization, followed by practical training at an implementing organization. By registering itself as an implementing organization, a Japanese factory receives unskilled laborers as trainees. The duration for practical training should be less than two-thirds of the total ITP period.

Table 1 lists the requirements for a sending organization, a supervising organization, an implementing organization, and a trainee. These requirements seem to present hurdles to the use of the ITP. Note that the requirements include some ambiguous content, and that there is room for arbitrary application. For example, the application of (3) in Table 1 depends on an observer’s viewpoint on whether a job is regarded as “simple repeated practice.” The ITP and the below-mentioned Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) have been used for their own benefit by implementing accepting organizations’ needs, which shows strong demand for cheap foreign laborers.

The Japanese government does not recognize a labor-management relationship (i.e., an employee-employer relationship) between a trainee and an implementing organization, because the nature of an ITP is “training.” Accordingly, the payment for a trainee’s work takes the form of “compensation” for the necessary expenses of his or her stay in Japan instead of “salary.” Therefore, the Labor Standards Act is not applicable to ITP trainees. Oftentimes, trainees do not receive industrial insurance and their “compensation” money is less than the lowest payment stipulated by the Minimum Wages Act.

The length of stay for the ITP was limited to one year or less. However, trainees and implementing organizations often found that this was too short. Thus, in 1993, the Japanese government introduced a new framework called the TITP to allow trainees to stay longer than a year. Foreigners in the TITP are called “technical intern trainees.” A foreigner who wants to continue “training” for longer than one year should do so by upgrading his or her status from an ITP trainee to a TITP technical intern trainee.

Requirements for this upgrade can be summarized by the following three points[1]: (i) the trainee has already acquired technical skills that are equivalent to the Basic 2-Level of the National Technical Skill Test; (ii) the living conditions and working performance of the trainee are satisfactory; and (iii) the implementing organization that is responsible for the trainee’s ITP training has an appropriate plan for his or her TITP training.

It is not difficult to satisfy these requirements. Thus, whether a trainee will continue to receive training as a technical intern trainee for another two years, following completion of one year of training, normally follows an informal registration procedure with a sending organization (i.e., before he or she comes to Japan).

Unlike the case of an ITP trainee, the relationship between a technical intern trainee in the TITP and a Japanese company or farm is officially recognized as a labor-management relationship (i.e., an employee-employer relationship). The policy rationale of the Japanese government is that the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills through learning is the purpose of the ITP, while that of the TITP is the acquisition of practical skills through employment.

The maximum number of trainees or technical intern trainees in an implementing organization differs according to the size of the implementing organization (measured by the total number of full-time employees), as shown in Table 2.

Trainees and technical intern trainees have contributed to the Japanese society as indispensable laborers in 3D workplaces. However, because many of them are unfamiliar with the local lifestyle and are not fluent in the Japanese language, there are many cases of communication problems with local communities.

CRITICISM ON THE ITP AND TITP

The ITP and TITP receive ongoing harsh criticism for insufficiency in protecting foreigners’ human rights. In principle, foreigners in the ITP or TITP are not allowed to change their workplace after entering Japan[2]. Thus, if the Japanese authorities find any problem with a foreigner (even if only a manager of the implementing organization produces the problem), the ITP or TITP will be immediately canceled and he or she is forced to return to his or her country of origin. This means that he or she loses their earning opportunity in Japan. Thus, foreigners in the ITP and TITP tend not to complain, even if they are treated badly at implementing organizations[3].

To worsen the situation, a sending organization often collects a large amount of money as deposit from a person who wants to go to Japan as a trainee or technical intern trainee. The deposit is withheld until the trainee successfully completes all the jobs in Japan. In that sense, a Japanese implementing organization is in a fiduciary position when managing a trainee or a technical intern trainee.

Human rights organizations both inside and outside Japan often criticized Japan for this policy. For them, the basic problem is the difference between the official explanation and the reality of foreigners’ situation: while the Japanese government insists that foreigners in the ITP and TITP are receiving training, they are de facto unskilled laborers.

For example, Jorge Bustamante, the U.N. special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, urged the Japanese government in April 2010 to terminate its industrial trainee and technical intern program for overseas workers, saying that it may amount to “slavery” in some cases, by fueling demand for exploitative cheap labor, in possible violation of human rights.

In response to these criticisms, the Japanese government revised the ITP and TITP frameworks in July 2010. The government expanded the TITP and divided it into Type 1 and Type 2. TITP Type 1 should be applied for the first year of "training" by foreign laborers (accordingly, they should be called technical intern trainees instead of trainees). TITP Type 2 should be applied for the second and third years of “training”.

By this revision, the Labor Standards Act is effective from the first year of foreign unskilled laborers’ stay in Japan. However, unskilled foreign laborers are still at a disadvantage because they are not allowed to change their workplaces if they wish to stay in Japan. The Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA) asserts that the replacement of the ITP by TITP Type 1 can be seen as a time-serving remedy to the critical feedback, which produces no significant changes for unskilled foreign workers’ position (JFBA, “Gaikokujin Gino Seido No Sokyu No Haishi Wo Motomeru Ikensho” (A Proposal to Abolish Technical Intern Training Program), June 2013).

In addition, implementing organizations identify problems in the ITP and TITP. They often present their complaints in the following four areas:

In 2017, the Japanese government revised the TITP. Aiming to improve the working conditions of technical intern trainees, the government established the Organization for Technical Intern Training (OTIT). The OTIT is responsible for reviewing the performance of supervising and implementing organizations. If the OTIT recognizes that technical intern trainees’ working and living conditions are excellent, it allocates the title of "excellent level organizations" to the supervising and implementing organizations. These organizations are allowed to extend the maximum staying period of technical intern trainees from three to five years (the “training” in these additional two years are called TITP Type 3). In addition, as shown in Table 2, the maximum number of technical intern trainees in the supervising and implementing organizations has increased.

JAPAN’S NEW IMMIGRATION POLICY IN 2018

In 2018, the government made a historic decision on its immigration control policy. Specifically, by establishing a new category called SSW in the list of the Status of Residence, the government reduced its barriers to entry for unskilled foreign laborers.

Two SSW types exist, namely, SSW Type 1 and Type 2. The government nominated 14 industrial fields within which foreigners are allowed to apply for SSW Type 1: agriculture, caregiving, restaurant, construction, building cleaning, food processing, hotel, foundry, ship building, fishery, industrial machinery assembling, automobile maintenance, electronic device assembling, and aviation related services. Foreigners can obtain SSW Type 1 visa status in two ways. The first is automatic transition from TITP Type 2 or Type 3 on completion of the “training” period (this means that the skill level of SSW Type 1 is the same as that of TITP Type 2 or Type 3). The other is to take an examination whereby foreigners are tested on their Japanese language proficiency and working skills (the contents and levels differ according to the 14 fields).

Unlike technical intern trainees, specified skilled workers enter directly into employment contracts with employers and have the freedom of changing their places of work (as far as workplaces are in the designated industrial fields). Holders of SSW Type 1 visas are allowed to stay in Japan for up to 60 months (unlike the case of technical intern trainees, the status of SSW does not expire, even if the specified skilled workers return to their countries of origin).

SSW Type 1 visa holders are qualified to take a skills level examination for upgrading their status to SSW Type 2. SSW Type 1 and Type 2 differ in living conditions in the following two aspects. The first aspect is the staying period. Unlike that of SSW Type 1, the status of SSW Type 2 is renewable (there is no limitation on the number of renewal times)[4]. The second aspect is the treatment for family members of a specified skilled worker. While the SSW Type 2 visa holders are allowed to bring their family members to Japan, those of SSW Type 1 visas are not.

The Japanese government first announced its plan to establish SSW visas on July 5, 2018 in a draft of “Basic Policies for the Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform.” This announcement heralded government’s significant progress towards inviting foreigners as permanent laborers at 3D workplaces.

Mass media reported this announcement as a turning point in Japan’s immigration policy; it reflected the changing attitude of supporters for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which has been in power almost uninterruptedly since 1955[5]. Farmers and construction companies have been powerful supporters of the LDP. Previously, they tended to have a conservative (or negative) approach to foreigners. However, they are now showing strong demands for foreign laborers due to the serious labor shortage[6].

Citizens’ sentiment toward foreigners is also changing. As a result of aging population, elderly caregiving became one of the biggest concerns for the citizens, who are aware that care facilities are affected by labor shortage. This weakened the citizens’ resistance to accepting foreign workers.

Mass media pointed out that the LDP wanted to show their successes in increasing unskilled foreign laborers as part of a campaign for the unified local elections and the election of members of the House of Councilors, which would take place in April 2019 and July 2019, respectively[7].

While demands for unskilled foreign laborers in 3D workplaces continued to increase, conservative groups still fear that a mass inflow of foreign laborers may increase crimes and disturb the social order. In fact, when the government submitted a bill to amend the ICRRA so as to create SSW on November 2, 2018, the opposition parties strongly disagreed. In addition, when the bill was taken into deliberation in the Diet, the government was not ready to provide detailed information on the skill and language levels required by specified skilled workers. Moreover, serious mistakes were found in the document submitted by the government as a reference for discussion in the Diet. While opposition parties requested to postpone voting for the bill in the Diet, the LDP was pressed to implement the SSW category before the unified local election. As a result, the bill to amend the ICRRA was passed by the Diet in a majority vote on November 27, 2018. The amended ICRRA became effective on April 1, 2019.

On November 25, 2018, the government announced the following planned number of SSW Type 1 visas for the 2019 fiscal year (from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020): 7,300 for agriculture; 5,000 for caregiving; 5,000 for restaurants; 6,000 for construction; 7,000 for building cleaning; 6,800 for food processing; 1,050 for hotels; 4,300 for foundry; 1,700 for ship building; 800 for fisheries; 1,050 for industrial machinery assembling; 800 for automobile maintenance; 650 for electronic device assembling; and 100 for aviation related services. Simultaneously, the government announced that the total number of SSW Type 1 visa holders for the 2019 to 2023 fiscal years (from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2024) should be 345,150 or less.

Citizens hold two contrasting opinions on these numbers[8]. Some find them not sufficiently large to mitigate the labor shortage, while others present their concerns that these numbers are too large to retain social order in local Japanese communities.

While the SSW Type 2 visa was initiated on April 1, 2019, the Japanese government has not issued this visa to any foreigners, because it has not designated any fields for the visa type. Accordingly, the required examination level for converting the SSW Type 1 visa to Type 2 is still unclear.

It is too early to evaluate the impacts of the establishment of the SSW visas. However, it is certain that the new status will create significant change in the Japanese labor market.

THE NEW POLICIES ON JAPANESE AGRICULTURE

Two types of agriculture exist, based on the degree of seasonal fluctuation in workload: small fluctuations in areas such as dairy and greenhouse farming, and large fluctuations in areas such as outdoor crop farming. For the former type, most of the technical intern trainees remain at the same farm for at least three years by upgrading their status from TITP Type 1 to Type 2 (and Type 3 later, if the conditions are satisfied). In this case, they are allowed to stay for another five years by converting their status from TITP Type 2 (or Type 3) to SSW Type 1 when they complete TITP Type 2 (or Type 3). Thus, the establishment of the SSW Type 1 visa will enable unskilled foreign laborers to work longer in farming[9].

For the latter types of agriculture, such as outdoor crop farming, technical intern trainees are employed for less than one year. Thus, most technical intern trainees return to their countries of origin without upgrading their status from TITP Type 1 to TITP Type 2. Since those who returned to their countries of origin after completing TITP (i.e., Type 1, Type 2, or Type 3) are not allowed to be granted TITP again, farmers must recruit new intern trainees every year. This burden makes the TITP less profitable for outdoor crop farming.

It should be noted that TITP’s major purpose at its establishment in 1993 was to mitigate labor shortages in factories, where there are little seasonal workload fluctuations. Thus, it is natural that the TITP design does not closely fit other workplaces such as outdoor crop farming.

In contrast, the government paid due attention to outdoor crop farming in designing the SSW Type 1 visa. While the government requires direct labor contracts between Japanese employers and specified skilled workers, it excluded agriculture from this requirement: specified skilled farm workers are allowed to enter into a labor contract with a personnel placement agency. The busy season for outdoor crop farming differs by region. Thus, a personnel placement agency can arrange different farms according to season for each specified skilled worker[10].

Currently, personnel placement agencies are not popular in recruiting Japanese agricultural laborers for outdoor crop farming. This is probably because Japanese laborers tend to live in the same workplace throughout a year. However, foreign unskilled laborers may be more flexible in changing places of living during their stay in Japan. Moreover, since specified skilled workers are allowed to repetitively leave and re-enter Japan, they can only work at the same farms during busy times. As such, the SSW Type 1 visas may bring structural changes to Japan’s agricultural labor market.

The government is negative in including agriculture in the list of SSW Type 2 visas[11].

CONCLUSION

The mitigation of the labor shortage in 3D workplaces is high on the Japanese government’s agenda. For years, Japan has been known as one of the most conservative countries to accept unskilled laborers from developing countries. However, it now seems timely for Japan to fully revise its immigration policy. The establishment of the SSW category in 2018 can be seen as the first movement toward such a revision.

It is too early to evaluate the Japanese government's new immigration policy. However, it is possible that a large inflow of foreigners will drastically reform 3D workplaces, with particularly large impacts in the agricultural industry.

Date submitted: October 14, 2019

Reviewed, edited and uploaded: November 22, 2019

[1] For caregiving, the requirements of upgrading TITP Type 1 to Type 2 are different from those for other sectors. The details are given in: Godo, Y., and T. W. Lim, “Foreign Nationals as Care Workers in Japan,” EAI Background Brief (National University of Singapore) No. 1398, 2018.

[2] If a trainee proves that there is no fault on his or her side, and that he or she can find another implementing organization that provides sufficient “training” to him or her, he or she is allowed to change his or her workplace. However, these conditions are so prohibitive that the workplace is almost unchangeable for trainees.

[3] “Hensai Dakede wa Kaerenai Gino Jisshusei (Technical Intern Trainees are Required more than Repayment),” AERA 134, September 26, 2018.

[4] The term of validity for the status of SSW Type 2 is between one and three years (it depends on various conditions).

[5] The LDP was not in power for two periods: the first was from August 1993 to May 1994, and the second was from September 2009 to December 2012

[6] “Hoshusho no Kabe Kuzusu Hitode Busoku (Labor Shortage Breaks Down the Wall of the Conservatives),” The Nikkei, June 2, 2018.

[7] “Jinzai Kaikoku Seisaku Tenkan Towareru Kakugo (Japan’s Decision of Calling in Laborers)," The Nikkei, June 2, 2018

[8] “Tokutei Ginou Kitai to Kenen (Expectations and Concerns for Specified Skilled Workers),” The Nikkei, December 15, 2018

[9] The Japanese government announced the basic plan for implementing a new immigration policy on December 25, 2018. There, 90 percent of specified skilled workers should be those who have completed the TITP.

[10] Specified skilled workers in fisheries, whose labor demands also fluctuate largely according to season, are allowed to enter into a labor contract with a personnel placement agency.

[11] On November 5, 2018, at the Standing Committee on Budget at the House of Councilors, Takamori Yoshikawa, the then-Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries indicated that agriculture would not be on the list of SSW Type 2 visas.