ABSTRACT

The Malaysian Government introduced the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020 (NAP4) in 2010, as a guidance document for the implementation of programs and projects for the development of the agricultural sector in Malaysia. The ten years period of this NAP4 will be completed at the end of 2020. After nearly eight years of implementation, there are some industries that show a good performance, while the other groups are still lacking behind the target and move very slowly. The performance of the agricultural sector is effected by many issues and challenges. The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry recognized the slow performance of this sector and introduced new directions, strategies and initiatives that can transform the agricultural sector faster. The new direction is geared towards ensuring national food security and boosting revenues from the agricultural sector. It is centered on food security, rural development and spurring domestic investments and international trade, aimed to get farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen out of poverty. The document sets five new directions that could be achieved through 18 strategies and 51 initiatives. The new direction is hoped to speed up the progress and achieve the NAP’s target by 2020.

Keywords: National Agrofood Policy, performance, New direction, strategies, initiatives,

INTRODUCTION

The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry introduced the National Agrofood Policy (NAP4) in 2010 as a replacement to the National Agricultural Policy (NAP3). The blueprint sets a direction to transform the agricultural sector to become more dynamic, progressive and sustainable. It addresses issues and challenges faced by every industry under the agrofood sector, sets strategies and action plans. The NAP4 covers a period between 2011 and 2020. The policy focuses on agrofood commodities, in contrast with the previous national agricultural policies that combine the agrofood and agroindustry commodities such as oil palm, rubber and cocoa.

The duration of the NAP4 will reach the destination in two years’ time. Some industries show great changes and impacts the socioeconomic status of farmers, livestock breeders and entrepreneurs. It also contributes to the revenue of Malaysia through exports of those commodities to world markets. On the other hand, some industries still remain stagnant and move slowly. This paper reviews the policy and analyzed the performance of five main industries that include paddy, fruits, captured fish, livestock and vegetable industries. These are the most critical industries and are considered as the security foods. At the end of this paper, the author presents the new direction of the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry as a new initiatives to speed up the implementation of programs and projects that could lead the performance of the National Agrofood Policy (NAP4).

National Agrofood Policy (NAP4)

The National Agrofood Policy was developed in 2010/2011, with the main focus on improving the efficiency of agrofood industry in Malaysia. The objectives of the NAP4 are, 1) to ensure adequate food supply and food safety, 2) to develop the agrofood into a competitive and sustainable industry and 3) to increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs. The policy was developed based on eight main ideas that are critical for the development of the agricultural sector in Malaysia as follows:

- Food security – sufficiency, availability, affordability and safety

- Development of high-value agriculture

- Sustainable agricultural development

- Dynamic agricultural cluster with maximization of income generation

- Private sector driven investments in modern agriculture

- Knowledge and information-based human capital

- Modernization of agriculture by R&D, technology and innovation

- Prime agricultural support services

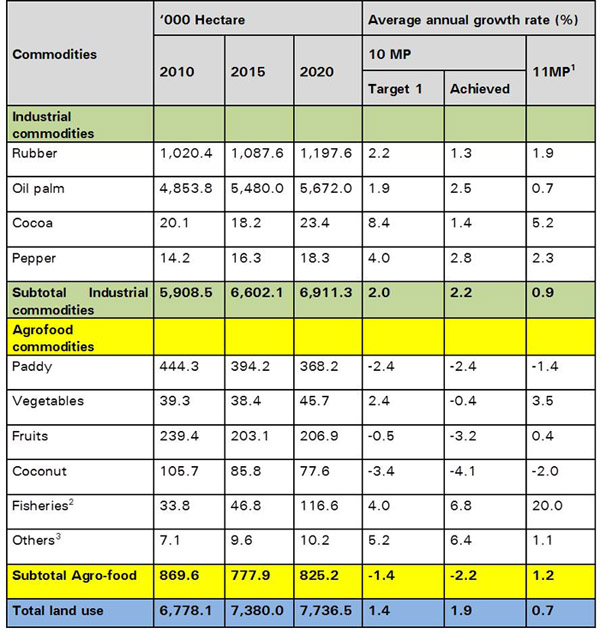

Food security is a global issue that concerns every nation. This is in line with the increase in world population, despite of the decrease of arable land for food production and climate change that affects biodiversity. Currently, the population of Malaysia is around 31.2 million people and is projected to increase to 35.8 million by 2020. On the other hand, despite the increase of agricultural land, the land capable of being plough and used to grow agrofood crops is projected to decrease 2.2% from 870,000 hectares in 2010 to 825,000 hectares in 2020 (Table 1).

Table 1. Land usage by Industrial and agrofood commodities (2010-2020)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry

The policy sets seven strategic directions to be achieved by 2020. The strategies are as follows:

- Ensure national food security;

- Increase the contribution of the agrofood industry to the national economy;

- Complete the value chain;

- Strengthen human capital;

- Strengthen R&D activities, innovation and technology adoption;

- Create private sector led business; and

- Strengthen service delivery system

The government has identified 15 industries to be developed that include i) paddy and rice, ii) captured fish, iii) livestock, iv) vegetable, v) fruit, vi) coconut, vii) edible bird’s nest, viii) aquaculture, ix) ornamental fish, x) seaweed, xi) herbs and spices, xii) floriculture, xiii) mushroom, xiv) agro-based products and xv) agro-tourism. The first six commodities are considered food securities, while the balance nine are to complement the agricultural sector.

Issues and challenges

In general, during the implementation of the NAP4, four main issues and challenges affected the performance of the agricultural sector in Malaysia. They are the depreciation of Malaysian Ringgit, changes in food consumption patterns, low productivity and less participation of youth, and the implementation of new tax regime (good and service tax). The depreciation of ringgit contributes to higher imported input price, leading to higher production cost and domestic food price. The value of Malaysian Ringgit has depreciated from RM3.4 when the policy was developed in 2010, to RM4.2 for one US dollar in 2018. As a result, the cost of buying inputs such as fertilizers, chemicals and machines from overseas has increased between 30% and 40%. Finally, the competitiveness of Malaysian products also declined as compared to neighboring countries such as Thailand and Indonesia. The depreciation of Malaysian Ringgit however, increased the export of Malaysian agrofood produce as the price is relatively cheaper than that when the value of Malaysian Ringgit was high.

The changes in food consumption patterns resulted in changes in domestic food demand. According to Tey Yeong Sheng (2008), since the economic crisis in 1997, there has been notable success in the Malaysian economy, where Malaysians are getting wealthier and food consumption is undergoing transitional changes. While the demand for rice is in-elastic income elasticity, the demand for meat and prawns has increased in line with the increase of income. A higher income will lead to a higher demand for expensive products. The consumption patterns of the young generation also showed a slight change. The demand for imported fruits and vegetables, especially products coming from temperate countries is increasing every year due to changes in people’s diets and preferences. Consequently, the demand for tropical fruits such as rambutan, mangosteen and durian by the youth has decreased significantly. A study by Rozhan (2006) revealed that the consumption patterns toward durian by young respondents indicated a negative trend. The preference toward eating fresh durian by the young generation has reduced from 99.6% in 1994 to 96.5% in 2004. Should the trend continue, it is projected that the preference toward fresh durian by the young generation will further decline. This pattern will affect the future demand of fresh durian and affect the industry in general.

Skilled labor in the agricultural sector continues to decline, coupled with the increase in the aging community. The number of people engaged in agricultural sector increased from 390,708 in 2010 to 444,531 people in 2015. Based on a statistics report, out of 31.8 million Malaysian population, around 43.85% are youths. However, from this figure, only 15% of youngsters are involved in the agricultural sector. The agricultural sector still fails to attract the interest of young generations, and the number of causes has been identified. According to Norsida (2008), many youths are not properly informed about the various opportunities in this sector. They also associated agricultural ventures with unstable return and the youths perceived agricultural entrepreneurship as being a high-risk venture.

The Malaysian government introduced the good and service tax (GST) in 2014. The new tax regime is a single and a broad based tax levied on goods and services consumed in an economy. More than 40% of inputs for agricultural produce, such as machineries and tools, fertilizers and chemicals are subject to a standard rate of GST, which is 6% across most industries under the NAP. As a result, the cost of production has increased between 6% and 15%. The increase of production has decreased the competitiveness of local agricultural produce, and has attracted imported produce from other neighboring countries.

Mid term performance of NAP4

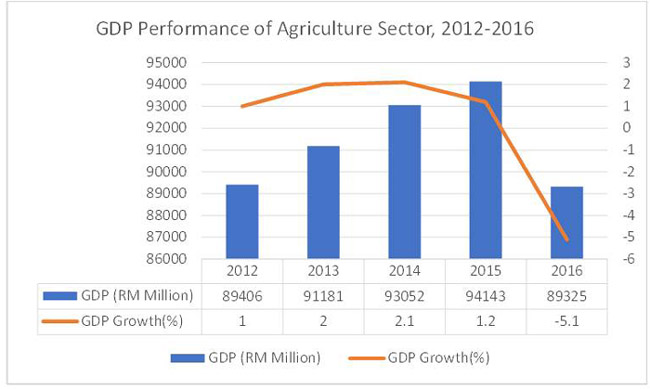

The agricultural sector contributed 8.1% of Malaysia’s GDP in 2016, worth of RM89.325 billion or USD21.77 billion. The agrofood sector accounted for 40.9%, while the industrial commodity contributed 59.1%. However, the agrofood recorded a decline growth of 5.1% (Fig. 1).

Fig 1. GDP performance of agricultural sector, 2010-2016

In 2016, palm oil was the largest contributor to the agricultural sector valued at 43.1%, followed by food crops (17.8%), livestock (11.7%) and fisheries (11.5%). In other words despite the fact that the agrofood sector still contributes significantly to Malaysia’s economy, the performance is declining.

The NAP (2011-2020) was formulated to further enhance the level of self-sufficiency level (SSL) and to reduce importation of agrofood products. Self-sufficiency level is one of the main indicators for agricultural performance, and it is defined as the ability of a country to produce its own commodity without external assistance. For example, the country grows enough rice to be self-sufficient. The general purpose of producing sufficient commodity is to ensure food security and not depending on imported agrofood produce. By producing sufficient agrofood, consumers are guaranteed of the availability, affordability and accessibility of foods; ensuring the competitiveness and sustainability of the agrofood industry and most importantly, to increase the income of farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen.

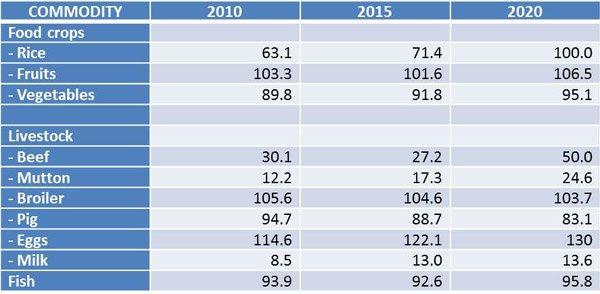

The government sets targets of SSL for selected agrofood commodities such as rice, fruits, vegetables, livestock and fisheries. At the same time the government formulated several strategies and action plans to ensure that the targets can be achieved during that period. The target of SSL for certain commodities is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. SSL targets for selected agrofood commodities (in percentage)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2016)

The government sets certain target for specific commodities based on the competitiveness of the industry and resource availability. For example, the SSL for livestock commodities was set at lower rates as compared to rice, fruits and vegetables. This is due to the resource availability. Malaysia is lacking in grazing area, lacking of parent cattle and higher cost of animal feed. Malaysia requires around one million parent cattle for breeding production. At the same time, Malaysian needs to open to around 400,000 hectares to place these cattle. On the hand, Malaysians need to import grain corn as the main source of animal feed. Every year, Malaysia imports more than four million MT grain corn valued at around US1 billion for animal feed. Furthermore, the hot weather in Malaysia is one of the factors that hinders the development of ruminant livestock. The gap between the supply and demand for livestock products is filled by importation. In 2016, Malaysia imported more than 45,000 live cattle and 150,402 MT of meat from Australia, New Zealand and India.

There are many factors that affected the SSL in Malaysia, such as the availability of arable land for cultivation, productivity of farm and labor and the suitability of climate for production of certain crops. In general, arable land is limited. Despite of this limitation, farmers in Malaysia prefer to use arable land for cultivating industrial crops, especially oil palm. As a result, land cultivated with industrial crops has increased from 5.9 million hectares in 2010 to 6.6 million hectares (2015) and is projected to further increase to 6.9 million hectares in 2020. On average, around 145,000 hectares of new land are open for cultivating industrial crops every year. On the other hand, land for agrofood has been reduced from 876,000 hectares in 2010 to 778,000 hectares (2015) and is projected to increase back to 825,000 hectares in 2020. The average growth indicated a - 2.2% every year.

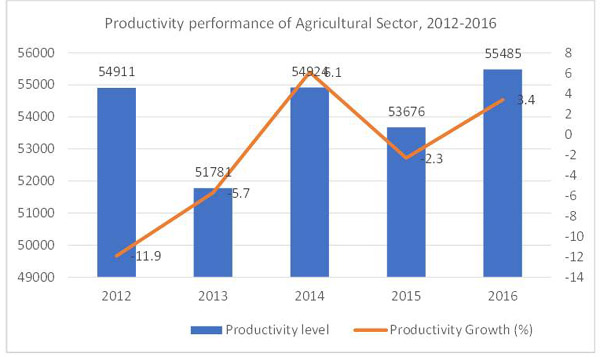

The agricultural sector is often characterized by substantial volatility in productivity over time. The fluctuation in climate conditions, such as droughts or heavy dawn fall severely affected the output of farms. In 2016, agricultural sector recorded a labor productivity growth of 3.4% to USD13,532.9 from USD13,091.7 in 2015 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Productivity performance of the agricultural sector, 2012-2016

The government introduced many initiatives to sustain the productivity of agricultural sector. For example, the intensive farming and integrated farming system between ruminant and oil palm had a greater impact on the productivity of this sector. The shift toward intensive production system and the adoption of intensive production techniques such as increased use of feeds, chemicals and irrigation also resulted with a higher productivity.

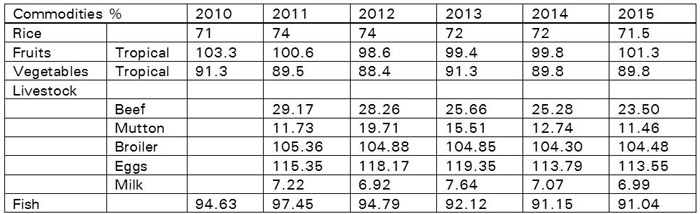

At the middle of the NAP, most industries within the agrofood sector are unable to achieve their SSL. This is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Performance of agrofood commodities indicated by SSL

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry

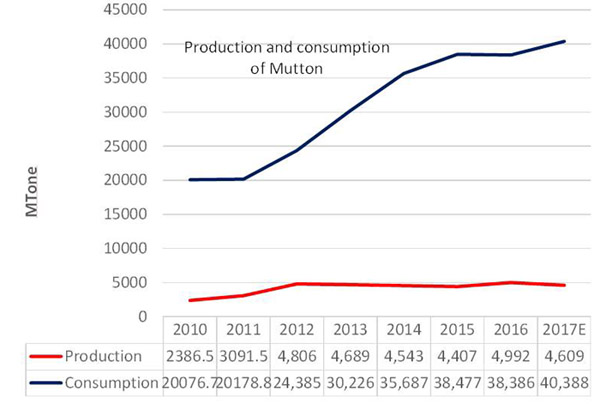

Table 3 shows the performance of agrofood commodities in Malaysia from 2010 to 2015. The table shows that only fruits and broilers have successfully achieved the target, whereas other commodities are lacking behind targets. The mutton and milk commodities require a special attention because of their slow performance. As a result, government imports more than 34,984 MT mutton and 1,541 million litters milk. This is more critical because the demand for mutton and milk is increasing every year ( Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Production and consumption of mutton

NEW DIRECTION FOR THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR

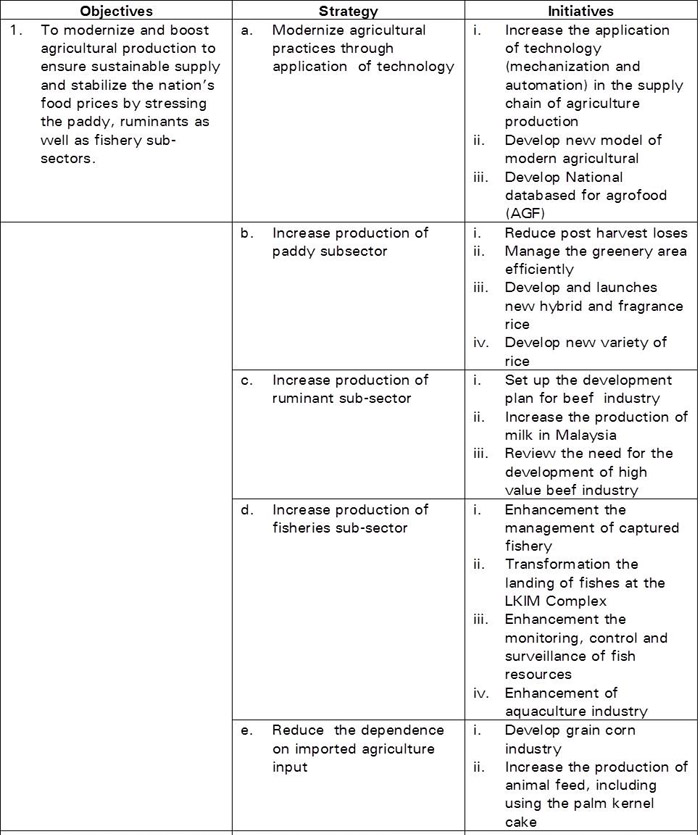

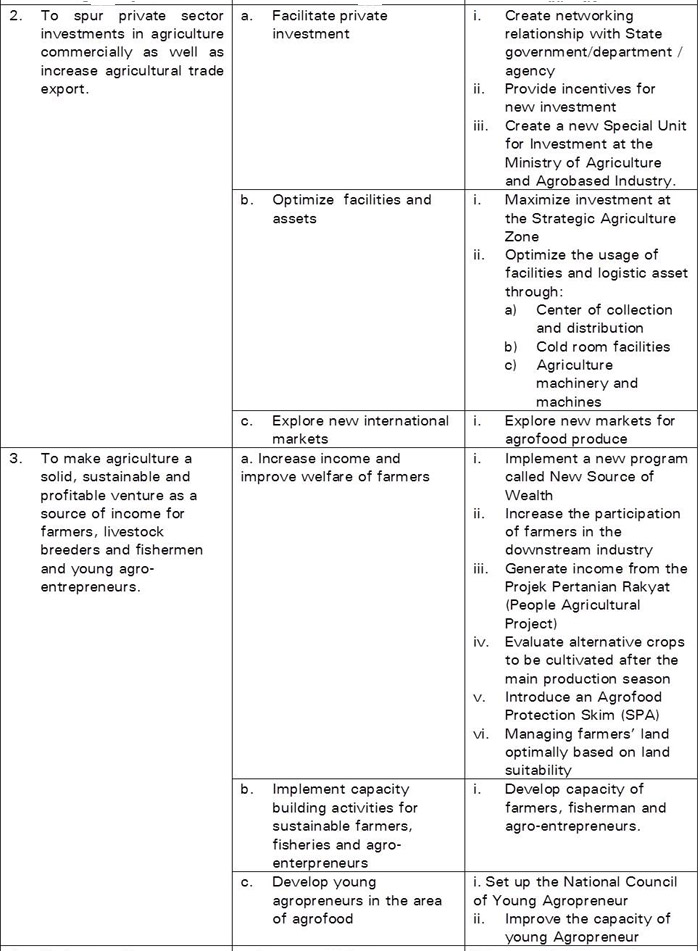

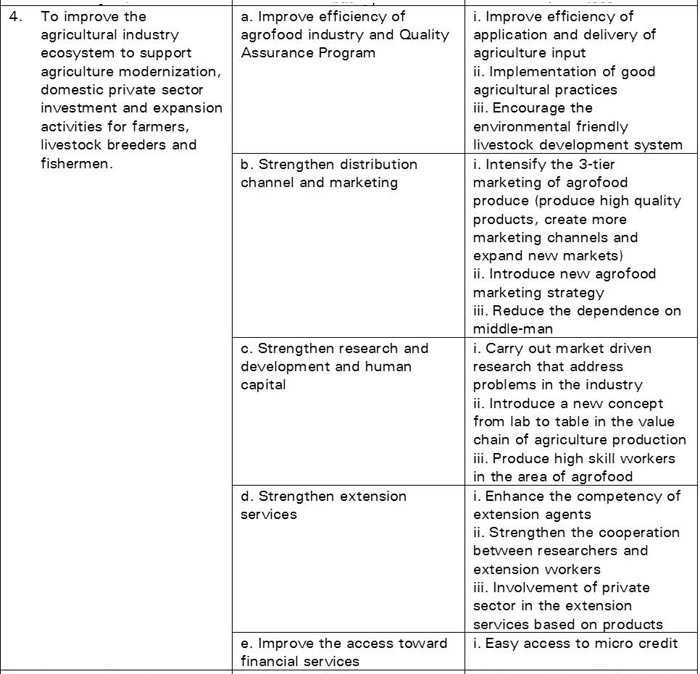

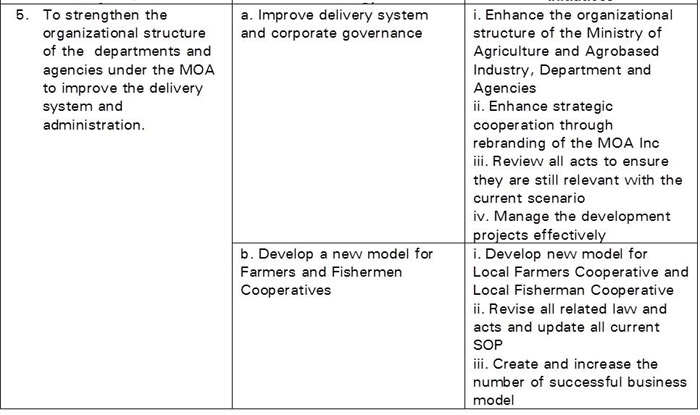

The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry released a new direction for the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry that cover a period between 2019 and 2020. The document highlights a five-point food security plan, 18 strategies and 51 initiatives that aims to strengthen the implementation of the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. The new direction was announced by its new Minister, Salahuddin Ayob on 14 February 2019. This action plan is geared towards ensuring national food security and boosting revenue in the agricultural sector. The document centered on food security, rural economic development as well as spurring domestic investments and international trade, aimed to get farmers, breeders and fishermen out of poverty. The five-point food security plan aims to achieve five objectives as follows:

- To modernize and boost agricultural production to ensure sustainable supplyand stabilize the nation’s food prices by stressing the paddy, ruminants as well as fishery sub-sectors;

- To spur private sector investments in agriculture commercially as well as increase agricultural trade exports;

- To make agriculture a solid, sustainable and profitable revenue source for farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen and young agro-entrepreneurs;.

- To improve the agricultural industry ecosystem to support agriculture modernization, domestic private sector investments and expansion activities for farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen; and

- To strengthen the organizational structure of the departments and agencies under the ministry of agriculture and agrobased industry to improve the delivery system and administration.

In order to achieve those objectives, the government creates new strategies and initiatives that covers all industries. The new strategies and initiatives are as follows:

The new direction of the agriculture sector does not contradict or overlap with the National Agrofood Policy. Instead, this document complemented the policy by addressing the weaknesses and the treats. This document was prepared based on the current scenario and performance of the agriculture sector. The current issues and challenges have slowed down the performance of the agriculture sector. This is evidenced by a lower production of many agrofood commodities, lower productivity and less competition among many agrofood products in the domestic and international markets. The new direction also takes into account the development of the agricultural industry in the other parts of the region, the issue of climate change and the new direction of new government in Malaysia.

CONCLUSION

The National Agrofood Policy is a document that sets the direction of the sector for a certain period of time. The document was prepared based on the scenario after analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the industry. However, not all plans will end up with success. During the implementation of a policy, new issues and challenges can crop up and slow down the sector’s performance. Thus, it is the role of the policy maker to monitor the performance and review the policies, so that a new plan of action can be undertaken.

The Malaysian government is optimistic that the objectives and targets set in the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020 could be achieved. The government has about three years to ensure that all initiatives, programs and projects will be carried out in accordance with the strategies. The new direction hopefully will speed up the activities and improve the performance. The document shows the commitment of the leaders in the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry toward the achievement of the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. The ultimate aim is to ensure that there is a sustainable and competitive agricultural sector in Malaysia, and up-lift the socioeconomic life of farmers, livestock breeders, fisherman and entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Anon (2016) National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry, Malaysia.

Anon (2019) Hala tuju Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani: Strategi dan Inisiatif. Kementterian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani, Malaysia.

Anon (2018). Productivity Report 2016/2017. National Productivity Centre, Malaysia.

Norsida, M. (2008). Youths Farmers Perception towards the needs of Agriculture Education. Journal Pembangunan Belia, 1, 99-114.

Rozhan Abu Dardak (2006). Consumers preference towards fresh durian in Malaysia. Economic and Technology Management Review Vol 1, 2006.

Tey, Yeong Sheng (2008) Food Consumption Patterns and Trends in Malaysia. Masters thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

Malaysia’s Agrofood Policy (NAP 2011-2020)- Performance and New Direction

ABSTRACT

The Malaysian Government introduced the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020 (NAP4) in 2010, as a guidance document for the implementation of programs and projects for the development of the agricultural sector in Malaysia. The ten years period of this NAP4 will be completed at the end of 2020. After nearly eight years of implementation, there are some industries that show a good performance, while the other groups are still lacking behind the target and move very slowly. The performance of the agricultural sector is effected by many issues and challenges. The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry recognized the slow performance of this sector and introduced new directions, strategies and initiatives that can transform the agricultural sector faster. The new direction is geared towards ensuring national food security and boosting revenues from the agricultural sector. It is centered on food security, rural development and spurring domestic investments and international trade, aimed to get farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen out of poverty. The document sets five new directions that could be achieved through 18 strategies and 51 initiatives. The new direction is hoped to speed up the progress and achieve the NAP’s target by 2020.

Keywords: National Agrofood Policy, performance, New direction, strategies, initiatives,

INTRODUCTION

The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry introduced the National Agrofood Policy (NAP4) in 2010 as a replacement to the National Agricultural Policy (NAP3). The blueprint sets a direction to transform the agricultural sector to become more dynamic, progressive and sustainable. It addresses issues and challenges faced by every industry under the agrofood sector, sets strategies and action plans. The NAP4 covers a period between 2011 and 2020. The policy focuses on agrofood commodities, in contrast with the previous national agricultural policies that combine the agrofood and agroindustry commodities such as oil palm, rubber and cocoa.

The duration of the NAP4 will reach the destination in two years’ time. Some industries show great changes and impacts the socioeconomic status of farmers, livestock breeders and entrepreneurs. It also contributes to the revenue of Malaysia through exports of those commodities to world markets. On the other hand, some industries still remain stagnant and move slowly. This paper reviews the policy and analyzed the performance of five main industries that include paddy, fruits, captured fish, livestock and vegetable industries. These are the most critical industries and are considered as the security foods. At the end of this paper, the author presents the new direction of the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry as a new initiatives to speed up the implementation of programs and projects that could lead the performance of the National Agrofood Policy (NAP4).

National Agrofood Policy (NAP4)

The National Agrofood Policy was developed in 2010/2011, with the main focus on improving the efficiency of agrofood industry in Malaysia. The objectives of the NAP4 are, 1) to ensure adequate food supply and food safety, 2) to develop the agrofood into a competitive and sustainable industry and 3) to increase the income level of agricultural entrepreneurs. The policy was developed based on eight main ideas that are critical for the development of the agricultural sector in Malaysia as follows:

Food security is a global issue that concerns every nation. This is in line with the increase in world population, despite of the decrease of arable land for food production and climate change that affects biodiversity. Currently, the population of Malaysia is around 31.2 million people and is projected to increase to 35.8 million by 2020. On the other hand, despite the increase of agricultural land, the land capable of being plough and used to grow agrofood crops is projected to decrease 2.2% from 870,000 hectares in 2010 to 825,000 hectares in 2020 (Table 1).

Table 1. Land usage by Industrial and agrofood commodities (2010-2020)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry

The policy sets seven strategic directions to be achieved by 2020. The strategies are as follows:

The government has identified 15 industries to be developed that include i) paddy and rice, ii) captured fish, iii) livestock, iv) vegetable, v) fruit, vi) coconut, vii) edible bird’s nest, viii) aquaculture, ix) ornamental fish, x) seaweed, xi) herbs and spices, xii) floriculture, xiii) mushroom, xiv) agro-based products and xv) agro-tourism. The first six commodities are considered food securities, while the balance nine are to complement the agricultural sector.

Issues and challenges

In general, during the implementation of the NAP4, four main issues and challenges affected the performance of the agricultural sector in Malaysia. They are the depreciation of Malaysian Ringgit, changes in food consumption patterns, low productivity and less participation of youth, and the implementation of new tax regime (good and service tax). The depreciation of ringgit contributes to higher imported input price, leading to higher production cost and domestic food price. The value of Malaysian Ringgit has depreciated from RM3.4 when the policy was developed in 2010, to RM4.2 for one US dollar in 2018. As a result, the cost of buying inputs such as fertilizers, chemicals and machines from overseas has increased between 30% and 40%. Finally, the competitiveness of Malaysian products also declined as compared to neighboring countries such as Thailand and Indonesia. The depreciation of Malaysian Ringgit however, increased the export of Malaysian agrofood produce as the price is relatively cheaper than that when the value of Malaysian Ringgit was high.

The changes in food consumption patterns resulted in changes in domestic food demand. According to Tey Yeong Sheng (2008), since the economic crisis in 1997, there has been notable success in the Malaysian economy, where Malaysians are getting wealthier and food consumption is undergoing transitional changes. While the demand for rice is in-elastic income elasticity, the demand for meat and prawns has increased in line with the increase of income. A higher income will lead to a higher demand for expensive products. The consumption patterns of the young generation also showed a slight change. The demand for imported fruits and vegetables, especially products coming from temperate countries is increasing every year due to changes in people’s diets and preferences. Consequently, the demand for tropical fruits such as rambutan, mangosteen and durian by the youth has decreased significantly. A study by Rozhan (2006) revealed that the consumption patterns toward durian by young respondents indicated a negative trend. The preference toward eating fresh durian by the young generation has reduced from 99.6% in 1994 to 96.5% in 2004. Should the trend continue, it is projected that the preference toward fresh durian by the young generation will further decline. This pattern will affect the future demand of fresh durian and affect the industry in general.

Skilled labor in the agricultural sector continues to decline, coupled with the increase in the aging community. The number of people engaged in agricultural sector increased from 390,708 in 2010 to 444,531 people in 2015. Based on a statistics report, out of 31.8 million Malaysian population, around 43.85% are youths. However, from this figure, only 15% of youngsters are involved in the agricultural sector. The agricultural sector still fails to attract the interest of young generations, and the number of causes has been identified. According to Norsida (2008), many youths are not properly informed about the various opportunities in this sector. They also associated agricultural ventures with unstable return and the youths perceived agricultural entrepreneurship as being a high-risk venture.

The Malaysian government introduced the good and service tax (GST) in 2014. The new tax regime is a single and a broad based tax levied on goods and services consumed in an economy. More than 40% of inputs for agricultural produce, such as machineries and tools, fertilizers and chemicals are subject to a standard rate of GST, which is 6% across most industries under the NAP. As a result, the cost of production has increased between 6% and 15%. The increase of production has decreased the competitiveness of local agricultural produce, and has attracted imported produce from other neighboring countries.

Mid term performance of NAP4

The agricultural sector contributed 8.1% of Malaysia’s GDP in 2016, worth of RM89.325 billion or USD21.77 billion. The agrofood sector accounted for 40.9%, while the industrial commodity contributed 59.1%. However, the agrofood recorded a decline growth of 5.1% (Fig. 1).

Fig 1. GDP performance of agricultural sector, 2010-2016

In 2016, palm oil was the largest contributor to the agricultural sector valued at 43.1%, followed by food crops (17.8%), livestock (11.7%) and fisheries (11.5%). In other words despite the fact that the agrofood sector still contributes significantly to Malaysia’s economy, the performance is declining.

The NAP (2011-2020) was formulated to further enhance the level of self-sufficiency level (SSL) and to reduce importation of agrofood products. Self-sufficiency level is one of the main indicators for agricultural performance, and it is defined as the ability of a country to produce its own commodity without external assistance. For example, the country grows enough rice to be self-sufficient. The general purpose of producing sufficient commodity is to ensure food security and not depending on imported agrofood produce. By producing sufficient agrofood, consumers are guaranteed of the availability, affordability and accessibility of foods; ensuring the competitiveness and sustainability of the agrofood industry and most importantly, to increase the income of farmers, livestock breeders and fishermen.

The government sets targets of SSL for selected agrofood commodities such as rice, fruits, vegetables, livestock and fisheries. At the same time the government formulated several strategies and action plans to ensure that the targets can be achieved during that period. The target of SSL for certain commodities is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. SSL targets for selected agrofood commodities (in percentage)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry (2016)

The government sets certain target for specific commodities based on the competitiveness of the industry and resource availability. For example, the SSL for livestock commodities was set at lower rates as compared to rice, fruits and vegetables. This is due to the resource availability. Malaysia is lacking in grazing area, lacking of parent cattle and higher cost of animal feed. Malaysia requires around one million parent cattle for breeding production. At the same time, Malaysian needs to open to around 400,000 hectares to place these cattle. On the hand, Malaysians need to import grain corn as the main source of animal feed. Every year, Malaysia imports more than four million MT grain corn valued at around US1 billion for animal feed. Furthermore, the hot weather in Malaysia is one of the factors that hinders the development of ruminant livestock. The gap between the supply and demand for livestock products is filled by importation. In 2016, Malaysia imported more than 45,000 live cattle and 150,402 MT of meat from Australia, New Zealand and India.

There are many factors that affected the SSL in Malaysia, such as the availability of arable land for cultivation, productivity of farm and labor and the suitability of climate for production of certain crops. In general, arable land is limited. Despite of this limitation, farmers in Malaysia prefer to use arable land for cultivating industrial crops, especially oil palm. As a result, land cultivated with industrial crops has increased from 5.9 million hectares in 2010 to 6.6 million hectares (2015) and is projected to further increase to 6.9 million hectares in 2020. On average, around 145,000 hectares of new land are open for cultivating industrial crops every year. On the other hand, land for agrofood has been reduced from 876,000 hectares in 2010 to 778,000 hectares (2015) and is projected to increase back to 825,000 hectares in 2020. The average growth indicated a - 2.2% every year.

The agricultural sector is often characterized by substantial volatility in productivity over time. The fluctuation in climate conditions, such as droughts or heavy dawn fall severely affected the output of farms. In 2016, agricultural sector recorded a labor productivity growth of 3.4% to USD13,532.9 from USD13,091.7 in 2015 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Productivity performance of the agricultural sector, 2012-2016

The government introduced many initiatives to sustain the productivity of agricultural sector. For example, the intensive farming and integrated farming system between ruminant and oil palm had a greater impact on the productivity of this sector. The shift toward intensive production system and the adoption of intensive production techniques such as increased use of feeds, chemicals and irrigation also resulted with a higher productivity.

At the middle of the NAP, most industries within the agrofood sector are unable to achieve their SSL. This is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Performance of agrofood commodities indicated by SSL

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry

Table 3 shows the performance of agrofood commodities in Malaysia from 2010 to 2015. The table shows that only fruits and broilers have successfully achieved the target, whereas other commodities are lacking behind targets. The mutton and milk commodities require a special attention because of their slow performance. As a result, government imports more than 34,984 MT mutton and 1,541 million litters milk. This is more critical because the demand for mutton and milk is increasing every year ( Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Production and consumption of mutton

NEW DIRECTION FOR THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR

The Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry released a new direction for the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry that cover a period between 2019 and 2020. The document highlights a five-point food security plan, 18 strategies and 51 initiatives that aims to strengthen the implementation of the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. The new direction was announced by its new Minister, Salahuddin Ayob on 14 February 2019. This action plan is geared towards ensuring national food security and boosting revenue in the agricultural sector. The document centered on food security, rural economic development as well as spurring domestic investments and international trade, aimed to get farmers, breeders and fishermen out of poverty. The five-point food security plan aims to achieve five objectives as follows:

In order to achieve those objectives, the government creates new strategies and initiatives that covers all industries. The new strategies and initiatives are as follows:

The new direction of the agriculture sector does not contradict or overlap with the National Agrofood Policy. Instead, this document complemented the policy by addressing the weaknesses and the treats. This document was prepared based on the current scenario and performance of the agriculture sector. The current issues and challenges have slowed down the performance of the agriculture sector. This is evidenced by a lower production of many agrofood commodities, lower productivity and less competition among many agrofood products in the domestic and international markets. The new direction also takes into account the development of the agricultural industry in the other parts of the region, the issue of climate change and the new direction of new government in Malaysia.

CONCLUSION

The National Agrofood Policy is a document that sets the direction of the sector for a certain period of time. The document was prepared based on the scenario after analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the industry. However, not all plans will end up with success. During the implementation of a policy, new issues and challenges can crop up and slow down the sector’s performance. Thus, it is the role of the policy maker to monitor the performance and review the policies, so that a new plan of action can be undertaken.

The Malaysian government is optimistic that the objectives and targets set in the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020 could be achieved. The government has about three years to ensure that all initiatives, programs and projects will be carried out in accordance with the strategies. The new direction hopefully will speed up the activities and improve the performance. The document shows the commitment of the leaders in the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry toward the achievement of the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. The ultimate aim is to ensure that there is a sustainable and competitive agricultural sector in Malaysia, and up-lift the socioeconomic life of farmers, livestock breeders, fisherman and entrepreneurs.

REFERENCES

Anon (2016) National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020. Ministry of Agriculture and Agrobased Industry, Malaysia.

Anon (2019) Hala tuju Kementerian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani: Strategi dan Inisiatif. Kementterian Pertanian dan Industri Asas Tani, Malaysia.

Anon (2018). Productivity Report 2016/2017. National Productivity Centre, Malaysia.

Norsida, M. (2008). Youths Farmers Perception towards the needs of Agriculture Education. Journal Pembangunan Belia, 1, 99-114.

Rozhan Abu Dardak (2006). Consumers preference towards fresh durian in Malaysia. Economic and Technology Management Review Vol 1, 2006.

Tey, Yeong Sheng (2008) Food Consumption Patterns and Trends in Malaysia. Masters thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia.